ABSTRACT

Reverse genetics systems have played a central role in developing recombinant viruses for a wide spectrum of virus research. The circular polymerase extension reaction (CPER) method has been applied to studying positive-strand RNA viruses, allowing researchers to bypass molecular cloning of viral cDNA clones and thus leading to the rapid generation of recombinant viruses. However, thus far, the CPER protocol has only been established using cap-dependent RNA viruses. Here, we demonstrate that a modified version of the CPER method can be successfully applied to positive-strand RNA viruses that use cap-independent, internal ribosomal entry site (IRES)-mediated translation. As a proof-of-concept, we employed mammalian viruses with different types (classes I, II, and III) of IRES to optimize the CPER method. Using the hepatitis C virus (HCV, class III), we found that inclusion in the CPER assembly of an RNA polymerase I promoter and terminator, instead of those from polymerase II, allowed greater viral production. This approach was also successful in generating recombinant bovine viral diarrhea virus (class III) following transfection of MDBK/293T co-cultures to overcome low transfection efficiency. In addition, we successfully generated the recombinant viruses from clinical specimens. Our modified CPER could be used for producing hepatitis A virus (HAV, type I) as well as de novo generation of encephalomyocarditis virus (type II). Finally, we generated recombinant HCV and HAV reporter viruses that exhibited replication comparable to that of the wild-type parental viruses. The recombinant HAV reporter virus helped evaluate antivirals. Taking the findings together, this study offers methodological advances in virology.

IMPORTANCE

The lack of versatility of reverse genetics systems remains a bottleneck in viral research. Especially when (re-)emerging viruses reach pandemic levels, rapid characterization and establishment of effective countermeasures using recombinant viruses are beneficial in disease control. Indeed, numerous studies have attempted to establish and improve the methods. The circular polymerase extension reaction (CPER) method has overcome major obstacles in generating recombinant viruses. However, this method has not yet been examined for positive-strand RNA viruses that use cap-independent, internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation. Here, we engineered a suitable gene cassette to expand the CPER method for all positive-strand RNA viruses. Furthermore, we overcame the difficulty of generating recombinant viruses because of low transfection efficiency. Using this modified method, we also successfully generated reporter viruses and recombinant viruses from a field sample without virus isolation. Taking these findings together, our adapted methodology is an innovative technology that could help advance virologic research.

KEYWORDS: reverse genetics, RNA virus, cap-independence, IRES, reporter virus

INTRODUCTION

In virology, reverse genetics, whereby recombinant viruses are generated from the nucleotide sequence of viral genomes, is widely used because viral cDNA clones offer a powerful tool for the characterization and manipulation of viral genomes. Indeed, recombinant viruses generated by reverse genetics have been clinically used as vaccines. For example, Dengvaxia (CYD-TDV) is a licensed dengue virus vaccine composed of four chimeric viruses that use the yellow fever virus vaccine strain 17D as the backbone and contain the structural protein gene of each dengue virus serotype (1). The generation of a new live-attenuated polio vaccine was accomplished by manipulating the viral genome of the preexisting vaccine strain (2). In addition, reporter viruses carrying a stable transgene capable of expressing specific signals (e.g., bioluminescence) helped investigating viral dynamics and assessed antivirals. Several studies, including ours, have successfully generated reporter viruses and used them in applied research (3–8).

Positive-strand RNA viruses encompass an enormous number of viruses across 41 viral families (9). Many of the major pathogens responsible for emerging and re-emerging viral diseases that are potentially threatening to humans are positive-strand RNA viruses (see recent review (10)), including Zika virus, Powassan virus, poliovirus, and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The reverse genetics system for positive-strand RNA viruses is based on the expression of viral RNAs from full-length cDNA clones that have been incorporated into plasmids, bacterial artificial chromosomes, or yeast artificial chromosomes. Incorporating bacteriophage-derived RNA promoters such as T7 or SP6 upstream of the viral 5′ untranslated region (UTR) sequence can drive in vitro transcription of viral RNA after providing the respective RNA polymerase (11). Alternatively, the incorporation of eukaryotic expression promoters instead of bacteriophage promoters allows the generation of viral RNA from transfected DNA by host RNA polymerase II (12). Although these reverse genetics approaches have been widely used, the construction and propagation of full-length infectious cDNA clones can be challenging. For example, cDNA clones are unstable when amplified in bacteria and/or yeast, making downstream experiments difficult (13). To overcome these issues, several approaches have been attempted. A circular polymerase extension reaction (CPER) method was initially developed for molecular cloning (14). Edmonds et al. first introduced this method for generating recombinant flaviviruses (15). Because the CPER method avoids molecular cloning of a full-length cDNA clone and its amplification in the recipient bacterial and/or yeast hosts, several groups, including ours, have successfully applied this method for other positive-strand RNA viruses (6, 7, 16–22).

Positive-strand RNA viruses are divided into two groups based on whether translation is cap-dependent or cap-independent. One of the latter mechanisms is driven by specific RNA elements known as internal ribosome entry sites (IRESs) that are found in the 5′ UTR of the viral RNA (23). IRES-dependent translation requires neither a cap nor some or all host factors needed for cap-dependent translation. Basis on their need for host factors and their proposed secondary structure, viral IRESs are divided into four groups (classes I–IV) (24). Because previous CPER methods used an RNA polymerase II (Pol-II) promoter, progeny RNA products would be capped. Thus, we hypothesized that the current version of the CPER method hinders the translation and production of positive-strand RNA viruses that use IRES-mediated translation, suggesting that the current CPER protocol could be optimized.

To this end, in the present study, we employed mammalian viruses possessing three types (classes I, II, and III) of IRESs and attempted to generate recombinant viruses by the CPER method. We constructed the gene cassette incorporating an RNA polymerase I (Pol-I) promoter/terminator instead of an RNA Pol-II promoter/ribozyme and assessed the efficacy of generating recombinant hepatitis C virus (HCV; class III), Pestivirus bovis [formerly known as bovine viral diarrhea virus-1 (BVDV-1); class III], hepatitis A virus (HAV; class I), and sequence-based de novo assembly of cardiovirus A [also known as encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV); class II]. In addition, we assessed the utility of our modified CPER method in generating recombinant HCV and HAV-carrying reporter genes.

RESULTS

Optimization of the current CPER method and generation of recombinant virus containing a class III IRES (HCV)

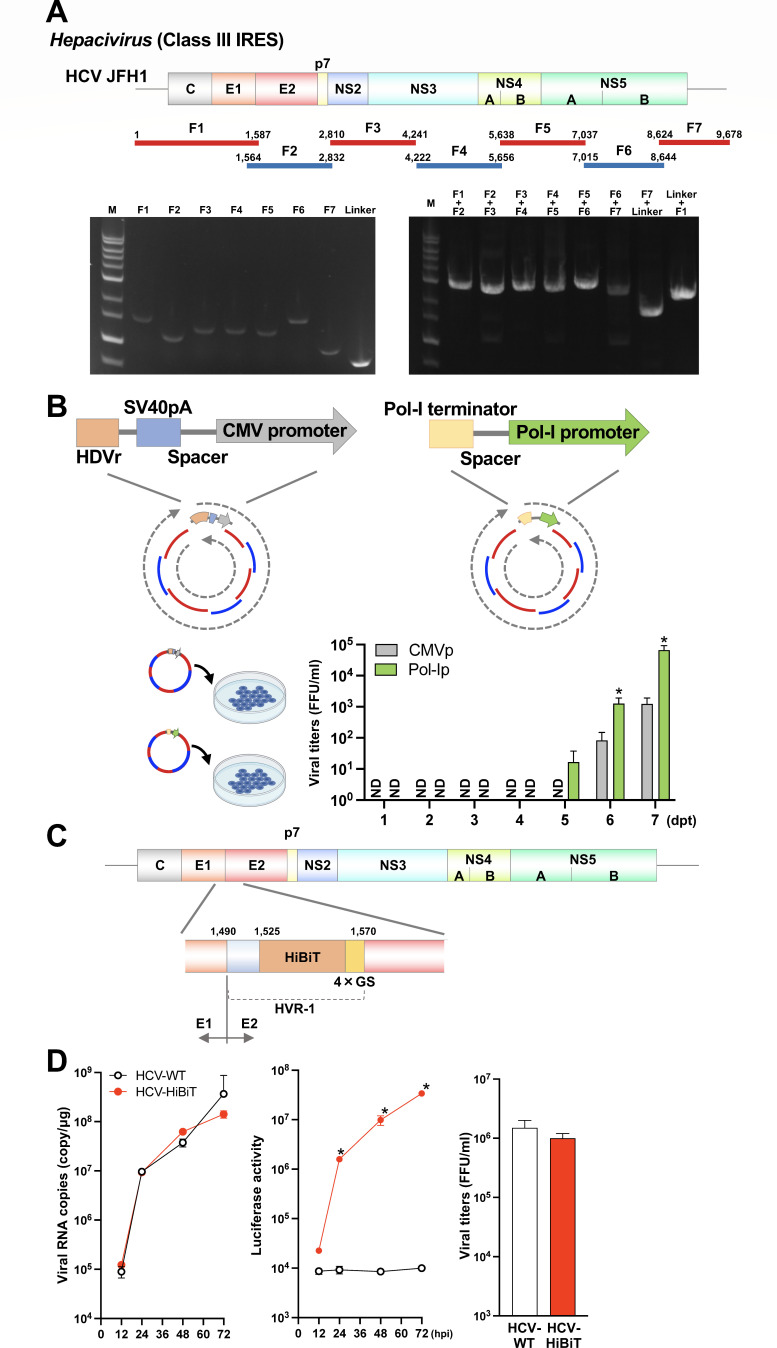

To establish the CPER protocol for viruses with IRES-mediated translation, we first employed HCV (genus, Hepacivirus; family, Flaviviridae), which contains a class III IRES (25). Viral RNA of the HCV JFH-1 strain (26) was purified from infected cells and a total of seven viral gene fragments covering the entire viral genome were amplified by high-fidelity DNA polymerase with a gene-specific primer set (Fig. 1A; Table S1). The generation of PCR amplicons at the expected size was confirmed by gel electrophoresis (Fig. 1A, left panel). Because CPER is based on assembly PCR, the correct joining of fragments via the overlapping regions is critical for making the complete circular cDNA assembly. As shown in the gel image (Fig. 1A, right panel), we detected PCR amplicons of the size expected for joined adjacent fragments.

Fig 1.

Optimization of the current CPER method and generation of the recombinant hepatitis C virus (HCV, class III IRES). (A) A schematic representation of the HCV genome and the gene fragments prepared. A total of seven fragments were amplified and then assembled with a UTR linker fragment by CPER. Gel electrophoresis analysis was conducted to confirm the size of the seven PCR amplicons (left panel). PCR assembly was used to connect neighboring fragments and the size of joined fragments was assessed by gel electrophoresis (right panel). F: fragment; M: 1 kb DNA ladder. (B) A schematic representation of the two UTR linkers was evaluated. The left panel shows the conventional gene cassette of the UTR linker used in CPER that encodes hepatitis D virus ribozyme, SV40 polyA, a 165 nt spacer, and a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter. The right panel shows the modified cassette generated in the present study that encodes murine RNA polymerase I terminator, a 165 nt spacer, and a human RNA polymerase I promoter. Each linker was subjected to CPER assembly to evaluate the efficiency of recovery of recombinant HCV as measured by a focus-forming assay (bar graph). Asterisks indicate significant differences (*P < 0.05) versus the results of the CMV promoter. ND: not detected. (C) A schematic representation of the recombinant HCV carrying the HiBiT luciferase gene. The HiBiT luciferase and GS linker sequence were inserted in hypervariable region I (HVR-I) within the HCV E2 envelope protein gene. (D) Huh7.5.1 cells were infected with the parental and recombinant HCV possessing HiBiT at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1. Intracellular viral RNA and the luciferase activities in the cells at 12, 24, 48, and 72 hpi (left and middle panels), and the infectious titers in the culture supernatants at 3 dpi (right panel) were determined by qRT-PCR, luciferase assay, and focus-forming assay, respectively. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*P < 0.05) versus the results of the parental virus (HCV-WT). Assays were performed independently in triplicate (B, D). Images were created with BioRender.com.

In the current version of the CPER method, the linker encodes a hepatitis D virus-derived ribozyme, polyA signals, spacer, and an RNA Pol-II promoter [e.g., a cytomegalovirus (CMV)-derived promoter]. Because the 5′ cap is not needed for IRES-mediated translation, the capping activity and structure generated by the RNA Pol-II complex might hinder correct IRES-mediated translation of viral RNA and thus potentially impair the production of progeny virus. Therefore, in this study, we instead created a plasmid vector encoding a Pol-I terminator, spacer, and a Pol-I promoter to amplify the linker fragment. To clarify whether a Pol-I or Pol-II promoter is more efficient in producing recombinant viruses, we conducted CPER assembly using a linker fragment encoding either Pol-I or Pol-II. The CPER products were transfected into Huh7.5.1 cells (Fig. 1B). Although the use of either Pol-I or Pol-II resulted in infectious HCV, infectious viruses were recovered at 5 dpi from the cells transfected with the Pol-I promoter-driven CPER product but not from those with the Pol-II promoter. Almost 100-fold higher yields of viruses were recovered after transfection with the Pol-I promoter-driven CPER product, indicating that the Pol-I promoter is better suited for the production of viruses that use IRES-mediated translation. The recombinant virus obtained from the CPER product had the same sequence as the reference virus strain. One advantage of the CPER method is that recombinant reporter viruses can be easily generated. Therefore, we attempted to generate recombinant HCV carrying a HiBiT luciferase gene (27). The luciferase gene was inserted by conventional PCR (primers in Table S1) into the N-terminus of hypervariable region 1 (HVR-1) in the HCV E2 protein (Fig. 1C). Huh7.5.1 cells were transfected with CPER-generated assemblies of either recombinant wild-type (HCV-WT) or reporter (HCV-HiBiT) virus. The virus produced by the transfected cells was collected. The two recombinant viruses were used to infect naïve Huh7.5.1 cells at an MOI of 0.1. Viral RNA levels and luciferase activity, as well as the infectious titers of the culture supernatants, were then determined. HCV-HiBiT exhibited growth kinetics similar to that of HCV-WT and led to intracellular luciferase activity that increased over time (Fig. 1D). These findings indicate that our modified CPER method is useful for the generation not only of intact recombinant viruses but also of recombinants carrying a foreign gene.

Generation of recombinant virus containing a class III IRES (BVDV) using a helper cell line for improved transfection efficiency of the CPER product

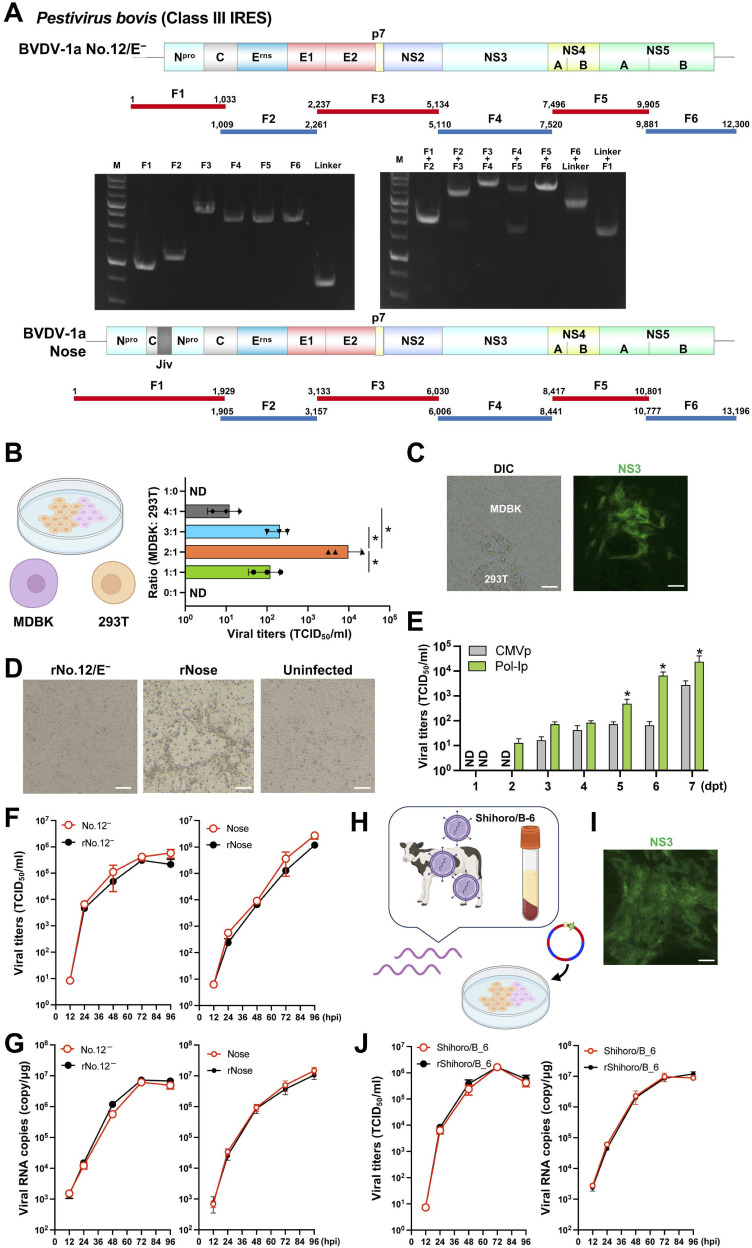

BVDV-1 (genus, Pestivirus; family, Flaviviridae) also contains a class III IRES (28). Some of the cytopathic BVDV genomes (29) contain gene duplications (30). In addition, sequences within the BVDV genome are toxic to bacteria, presenting a major obstacle in obtaining correct cDNA clones (13). Therefore, we applied the CPER method for generating recombinant BVDV. We employed two BVDV-1a strains with different gene constructs: one is a typical feature (No.12/E− strain (31)) and the other possesses a gene duplication in the C and Npro genes [Nose strain (30); Fig. 2A]. Six fragments covering the entire No.12/E− genome were prepared by PCR (primers in Table S2) for use in CPER assembly. After confirming that these fragments can connect correctly to their respective neighbors (Fig. 2A), the resultant CPER product was transfected into bovine MDBK cells, which are highly susceptible to BVDV infection. However, no positive cells were detected after staining for viral antigens, suggesting that RNA transcription and/or transfection were not successful. Because transfection of nucleic acids into MDBK cells is difficult (32), we then employed 293T cells, which have high transfection efficiency and express the SV40 large T antigen (33). We co-cultured MDBK and 293T cells at different ratios and then evaluated transfection of the CPER product (Fig. 2B). The 293T monocultures were unable to produce No.12/E− but recombinant BVDV was produced in transfected co-cultures with a ratio of 2:1 (MDBK:293T), demonstrating the greatest efficacy of the ratios examined. Interestingly, in the co-cultures, MDBK cells were positive for viral antigen, whereas 293T cells were negative (Fig. 2C). These findings indicate that the two co-cultured cell lines compensated for each other’s limitations to achieve the production of infectious virus.

Fig 2.

Generation of recombinant bovine viral diarrhea viruses (BVDV, class III IRES). (A) A schematic representation of the two types of BVDV genomes used (genotype 1a) and the gene fragments prepared. A total of six fragments were amplified and then assembled with the new UTR linker fragment by CPER. Gel electrophoresis analysis was conducted to confirm the size of the six PCR amplicons (left panel). PCR assembly was used to connect neighboring fragments and the size of joined fragments was assessed by gel electrophoresis (right panel). F: fragment; M: 1 kb DNA ladder. BVDV-1a Nose strain possesses a gene duplication in the Npro gene (Npro, C, and cINS). (B) Optimization of co-culturing of two cell lines for the production of recombinant BVDV-1a strain No.12−/E. The two cell lines employed in this study were bovine MDBK, which exhibits high utility for BVDV infection, and 293T, which shows high transfection efficiency and protein expression. Ratios of cell numbers and infectious titers are shown as a bar graph. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*P < 0.05) between a pair. (C) Images of transfected cells captured by differential interference contrast (DIC) or immunofluorescence using antiviral NS3 are shown at day 5 post-transfection. Scale bars, 100 µm. (D) Cytopathic effect was observed upon infection with the recombinant BVDVs. Scale bars, 100 µm. (E) Both linkers were individually subjected to CPER assembly to evaluate the efficiency of recovery of recombinant BVDV as measured by a TCID50 assay (bar graph). Asterisks indicate significant differences (*P < 0.05) versus the results of the CMV promoter. ND: not detected. (F, G) MDBK cells were inoculated at an MOI of 0.01 using the parental or recombinant BVDV. Virus titers in supernatants (F) and intracellular viral RNA (G) were determined at the indicated timepoints by TCID50 and qRT-PCR, respectively. (H) Illustration of the CPER method using a crude clinical isolate. Serum was obtained from animals persistently infected with BVDV strain Shihoro/B_6 (genotype 1b). The viral RNA was purified and the resultant viral cDNA was subjected to CPER assembly. The CPER product was transfected into co-cultures at the optimized MDBK:293T ratio of 2:1. (I) Antiviral NS3 immunofluorescence image of transfected cells at day 5 post-transfection. Scale bar, 100 µm. (J) MDBK cells were inoculated with the clinical isolate or recombinant BVDV at an MOI of 0.01. The virus titers in supernatants and intracellular viral RNA were determined at the indicated timepoints. The recombinant viruses are named according to the parental strains from which they were rescued, with “r” added at the start of the name (D, F, G, J). Assays were performed independently in triplicate (B, E, F, G, J). Images were created with BioRender.com.

Next, we assembled the cDNA of the Nose strain by CPER. Transfection of the CPER product into MDBK cells had a cytopathic effect (CPE) (Fig. 2D). Importantly, Sanger sequencing confirmed that the recombinant BVDV produced was identical to the parental virus. We also evaluated the difference in virus recovery between the two types of promoters (Fig. 2E). As we expected, the Pol-I promoter-driven CPER product produced 10-fold higher yields of infectious viruses than the Pol-II promoter at 2 and 3 dpi.

Then, to investigate the growth kinetics of the two recombinant BVDVs, parental and recombinant viruses were inoculated into MDBK cells at an MOI of 0.01. Intracellular viral RNA was quantified (Fig. 2F) and the infectious titers of the supernatants were determined (Fig. 2G). Both recombinant BVDVs exhibited comparable replication kinetics to the parental viruses. Taken together, these findings indicate that recombinant BVDV can be generated by our optimized CPER protocol.

Finally, to examine whether this CPER method applys to clinical isolates, we used serum from cattle persistently infected with BVDV (BVDV-1b strain Shihoro/B_6 (34)) for the generation of recombinant BVDV (Fig. 2H, primer set in Table S3). We purified viral RNA from the serum and subjected it to PCR amplification and CPER assembly. As shown in Fig. 2I, cells transfected with the CPER product were positive for viral antigens and capable of producing infectious recombinant viruses. The in vitro replication properties of the recombinant viruses were comparable to those of the original clinical isolate (Fig. 2J), indicating that the CPER method can be used with viral samples obtained in the field.

Generation of recombinant virus containing class I IRES (HAV)

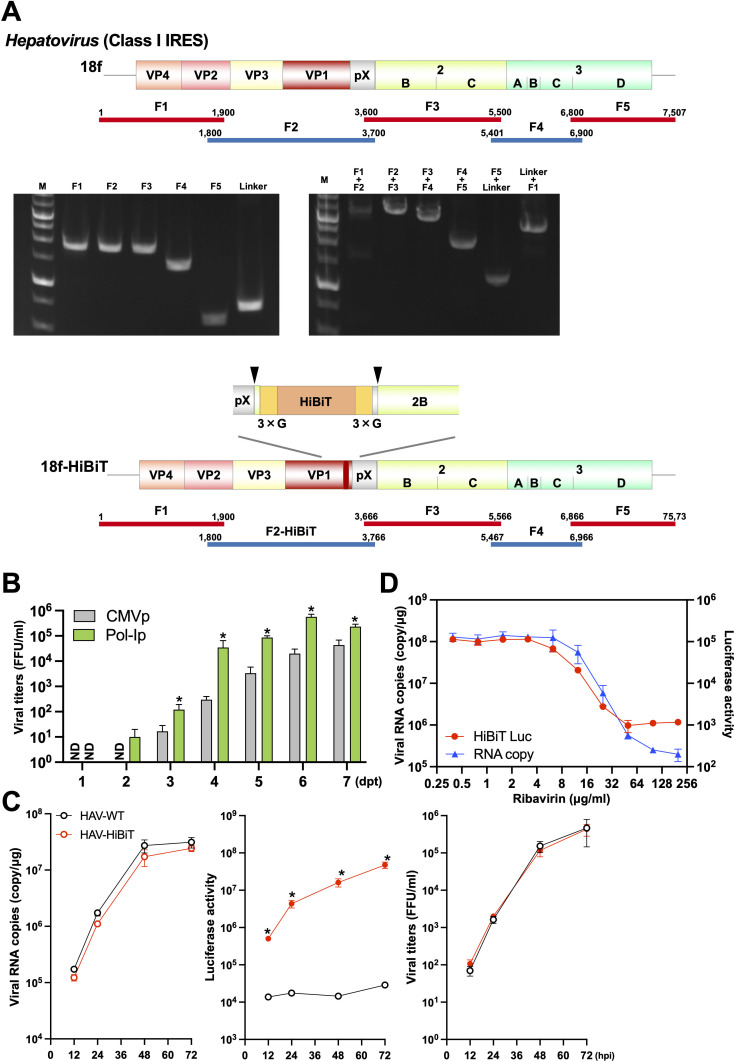

The Picornaviridae family includes viruses that have class I or class II IRES (35). The 5′ terminus of the HAV (genus, Hepatovirus) genome contains a class I IRES (36). Therefore, we decided to investigate whether our newly developed CPER method could be used for generating recombinant HAV (strain 18f; HAV-WT) (37) (Fig. 3A). In parallel, we attempted to generate a reporter 18f strain, inserting the gene encoding HiBiT (HAV-HiBiT) at the junction of the genes pX and VP2B, as previously reported (38). For each HAV genome, a total of five viral gene fragments and the linker fragment encoding a Pol-I promoter and terminator were amplified by PCR using the gene-specific primer set (Table S4). After confirming that these fragments can connect correctly (Fig. 3A), the resultant CPER products were transfected into Huh7 cells. Five days later, culture supernatants were collected. The generation of infectious HAV-WT and HAV-HiBiT was confirmed by immunostaining against viral Vp3. The nucleotide sequences of the recombinant viruses were the same as in the designed gene map. As shown in Fig. 3B, the Pol-I promoter-driven CPER product produced infectious recombinant viruses from 2 days post-transfection (dpt) and large amounts of infectious viruses compared with the Pol-II promoter-driven CPER product.

Fig 3.

Generation of the recombinant hepatitis A virus (HAV, class I IRES) and the reporter thereof. (A) A schematic representation of the HAV genome and the gene fragments prepared. A total of five fragments were amplified and then assembled with a UTR linker fragment by CPER. Gel electrophoresis analysis was conducted to confirm the size of the five PCR amplicons (left panel). PCR assembly was used to connect neighboring fragments and the size of joined fragments was assessed by gel electrophoresis (right panel). F: fragment; M: 1 kb DNA ladder. The HiBiT luciferase gene with GS linker was inserted at the pX-VP2B junction. Arrowheads indicate the recognition site of viral 3Cpro protease. (B) Both linkers were individually subjected to CPER assembly to evaluate the efficiency of recovery of recombinant HAV as measured by a focus-forming assay (bar graph). Asterisks indicate significant differences (*P < 0.05) versus the results of the CMV promoter. ND: not detected. (C) Huh7 cells were inoculated with parental (HAV-WT) or recombinant (HAV-HiBiT) virus at an MOI of 0.01. Intracellular viral RNA and luciferase activity as well as the infectious titers of supernatants were determined at the indicated timepoints by qRT-PCR, luciferase assay, or focus-forming assay, respectively. Asterisks indicate significant differences between HAV-HiBiT and HAV-WT (*P < 0.05). (D) Huh7 cells infected with recombinant HAV at an MOI of 0.1 were treated with various concentrations of ribavirin. At 4 dpi, the intracellular viral RNA and luciferase activity were determined by qRT-PCR and luciferase assay, respectively. Assays were performed independently in triplicate (B–D).

The HAV-WT and HAV-HiBiT collected from the supernatants of transfected cells were used to inoculate Huh7 cells, and intracellular HAV RNA levels and luciferase activity were determined (Fig. 3C). The increases in intracellular HAV RNA and infectious titers over time were similar for HAV-WT and HAV-HiBiT and, as expected, luciferase activity was detected only in cells infected with HAV-HiBiT. These findings indicate that our modified CPER method using a Pol-I promoter applys to the production of recombinant HAV.

Reporter viruses are often used to evaluate antiviral efficacy, and therefore we investigated whether the HAV-HiBiT generated by CPER could also be used to this end. We evaluated the anti-HAV activity of the well-known antiviral drug ribavirin (39). Huh7 cells were treated with different doses of ribavirin with HAV-HiBiT, and intracellular viral RNA and luciferase activity were determined at 4 days post-infection (dpi) (Fig. 3D). The intracellular viral RNA and luciferase activity were reduced in a ribavirin dose-dependent manner. Taking these findings together, we successfully generated recombinant HAV carrying the HiBiT and showed that this recombinant virus can be used for antiviral evaluation and screening.

Generation of recombinant virus containing class II IRES (EMCV)

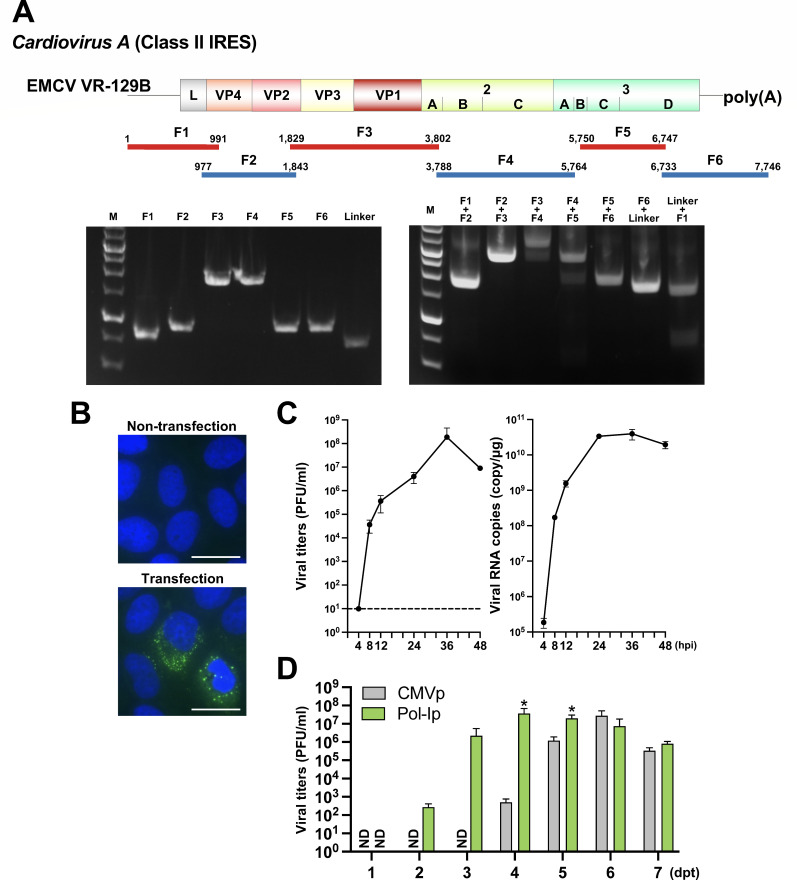

EMCV (genus, Cardiovirus; family, Picornaviridae) contains a class II IRES (40). To generate a recombinant EMCV de novo, we used the publicly available sequence of the reference strain VR-129B (GenBank accession number: KM269482). The whole genome was divided into six fragments, with the 3′ end of fragment 6 (F6) containing a 26 nt polyA sequence (Fig. 4A; Table S5). After amplification of the fragments, a check that the fragments had connected (Fig. 4A), and subsequent CPER assembly, the resultant product was transfected into Huh7 cells. By 3 dpt, Huh7 cells’ CPE was observed. The culture supernatants were used to inoculate naïve Huh7 cells. Staining with an anti-dsRNA antibody showed active replication at 8 hpi (Fig. 4B). In vitro growth kinetics were evaluated in Huh7 cells after infection with recombinant EMCV at an MOI of 0.01. As measured by both infectious titers and intracellular viral RNA levels, recombinant EMCV showed robust replication that peaked at 24 hpi (Fig. 4C), indicating that infectious EMCV was generated by our modified CPER method. The sequence of the recombinant EMCV was found to be identical to that of the reference information. Moreover, the yield of infectious EMCV was higher with the Pol-I promoter-driven CPER product than with the Pol-II promoter-driven one (Fig. 4D).

Fig 4.

Generation of the recombinant EMCV (class II IRES). (A) A schematic representation of the EMCV genome and the gene fragments prepared. A total of six fragments were amplified and then assembled with the new UTR linker fragment by CPER. Gel electrophoresis analysis was conducted to confirm the size of the six PCR amplicons (left panel). PCR assembly was used to connect neighboring fragments and the size of joined fragments was assessed by gel electrophoresis (right panel). F: fragment; M: 1 kb DNA ladder. (B) Huh7 cells were inoculated with 100 µL of culture supernatants collected from CPER-transfected cells. At 8 hpi, the cells were subjected to immunofluorescent staining of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA; green). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 25 µm. (C) Huh7 cells were inoculated with recombinant EMCV at an MOI of 0.01. The virus titers in supernatants and intracellular viral RNA were determined at the indicated timepoints by plaque-forming assay and qRT-PCR, respectively. (D) Both linkers were individually subjected to CPER assembly to evaluate the efficiency of recovery of recombinant EMCV as measured by a plaque-forming assay (bar graph). Asterisks indicate significant differences (*P < 0.05) versus the results of the CMV promoter. ND: not detected. Assays were performed independently in triplicate (C, D).

DISCUSSION

Humans are suffering from emerging and re-emerging diseases caused by viruses such as dengue virus, influenza virus, Ebola virus, and more recently SARS-CoV-2 (10). Characterization of virus strains and establishment of effective countermeasures are key for disease control. Although attention needs to be paid to recombinant viruses generated de novo in terms of concerns about biosafety and biosecurity, recombinant viruses generated by reverse genetics techniques have aided research to elucidate the viral life cycle and pathogenesis as well as to develop antivirals. To date, reverse genetics methods have been developed for many viruses but these often take months to complete. In the present study, we established a modified CPER protocol that allows rapid and versatile reverse genetics for generating positive-strand RNA viruses that use a cap-independent translation mechanism. A typical host mRNA consists of a 7-methylguanosine cap (m7G) at the 5′ terminus, a 5′ UTR, an open reading frame that begins with a start codon and ends with an in-frame stop codon, a 3′ UTR, and a poly(A) tail. Canonical cap-dependent translation begins with recruitment of the eIF4F complex, which includes the cap-binding protein eIF4E, the scaffold protein eIF4G, and the RNA helicase eIF4A, to the 5′ m7G (41). The eIF4F complex then recruits to the 5′ UTR the 43S preinitiation ribonucleoprotein complex that consists of eIF2–GTP–Met-tRNAiMet and the 40S ribosomal subunit.

Many positive-strand RNA viruses, including flaviviruses and SARS-CoV-2, also employ this conventional translation machinery (42). Interestingly, some viruses use a different translation strategy without stealing caps from host mRNAs. The IRES, a structural element found in the 5′ UTR of some viral RNA genomes, can instead recruit the ribosome to the mRNA for the initiation of translation (23). An IRES was first identified in poliovirus (43) and subsequently observed in many, but not all, positive-strand RNA viruses belonging to the families Dicistroviridae, Flaviviridae, and Picornaviridae (35). To date, the rapid reverse genetics method CPER has only been applied to viruses that use cap-dependent translation, including select flaviviruses, coronaviruses, togaviruses, insect alphamesoniviruses, and noroviruses using Vpg5-mediated translation (6, 7, 15–22). In the reverse genetics systems for RNA viruses with cap-dependent translation, RNA Pol-II catalyzes RNA transcription by capping the 5′ end of the template RNA (44). However, the 5′ cap is dispensable for IRES-mediated translation, and thus capping by the RNA Pol-II complex and/or the IRES structure itself might hinder IRES-mediated translation of the viral RNA. To investigate which promoter is suitable for viruses with IRES-mediated translation, we generated a plasmid vector encoding an RNA Pol-I terminator, spacer, and Pol-I promoter (Fig. 1B). Thus, in the final CPER product, the cDNA encoding the viral genome is flanked by the RNA Pol-I promoter and terminator, allowing transcripts to be generated in replication-competent cells. Notably, we optimized the setting of fragments covering the entire viral genome for correct CPER assembly by overlapping PCR of neighboring fragments (Fig. 1A, 2A, 3A, and 4A). As shown in Fig. 1B, both versions of the cassette could produce infectious HCV. This finding corresponds to both versions of the infectious cDNA clone of HCV that were reported previously (45, 46). We demonstrated that higher yields of recombinant virus could be generated in cells transfected with the CPER product containing a Pol-I versus. Pol-II promoter and terminator from all IRES types of viruses examined in this study (Fig. 1B, 2E, 3B, 4D). These results indicate that RNA transcripts with the correct 5′ and 3′ ends not containing modifications such as a cap structure are important for generating viruses that use noncanonical translation, as previously reported (47). Indeed, RNA Pol-I is employed in reverse genetics systems for producing negative-strand RNA viruses, including influenza viruses (48), Ebola viruses (49), nairoviruses (50), and phleboviruses (51). Although the CPER method enabled the production of infectious viruses, the efficiency of virus recovery can be optimized such as by performing DNA nick ligation after the CPER reaction (46). Further investigations will be beneficial for improving our method in the future.

The need for molecular cloning in bacteria can be omitted in the CPER method, and therefore a variety of recombinant viruses possessing mutations and/or inserted foreign genes can be designed and generated in a short period. HVR-1 is located at the N-terminus of the sequence encoding the E2 envelope protein of HCV (52–54). Numerous studies have reported that HVR-1 possesses high genetic diversity during the establishment of chronic HCV infection in patients (55–59), suggesting that HVR-1 can tolerate sequence changes associated with the insertion of foreign genes such as a reporter. In our previous study, recombinant HCV carrying a HiBiT luciferase gene replicated substantially in cell culture and was thus useful for antiviral screening and studying in vivo dynamics (6). In this study, using a modified version of the CPER method, the recombinant HCV containing HiBiT luciferase in the HVR-1 exhibited replication comparable to that of the wild-type recombinant HCV (Fig. 1C and D). In addition, we successfully generated a recombinant reporter HAV that robustly replicated in cell culture (Fig. 3C) and demonstrated its utility for the evaluation of antiviral efficacy (Fig. 3D). The viral replicon assays have been developed elsewhere and shown to be applicable for antiviral screening but the cell lines persistently harboring viral replicons (replicon cells) take a few weeks to establish because of antibiotic selection. In addition, we eventually need to evaluate the candidate antiviral(s) using an actual virus. Here, the recombinant viruses carrying the reporter tag generated by our approach overcome this burden and are an efficient tool for high-throughput antiviral screening.

We were unable to obtain an EMCV strain, and therefore we used a database-derived sequence to conduct de novo assembly by CPER. As shown in Fig. 4A, we arranged for the synthesis of viral cDNA in fragments of around 1–2 kbp, which allowed us to obtain the cDNA relatively quickly and at a reasonable cost. Active RNA replication was only observed in cultures transfected with the CPER product (Fig. 4B), and the recombinant virus exhibited rapid and robust replication in cell culture (Fig. 4C), consistent with previous reports (60, 61).

BVDV is the causative agent of bovine viral diarrhea, leading to economic loss in agriculture (62). Difficulties in the reverse genetics of BVDV are that (i) the viral sequence demonstrates toxicity in bacteria (13); (ii) duplication of viral genes observed in a cytopathic BVDV makes it difficult to obtain the correct cDNA clone (30); and (iii) it is difficult to deliver cDNA into the susceptible cell line MDBK (32). In this study, we overcame all of these challenges and successfully generated recombinant BVDV, including a cytopathic strain carrying a gene duplication in the viral gene Npro (Fig. 2). Because MDBK cells, which are difficult to transfect, are the primary choice for BVDV research, we employed a co-culture strategy with 293T cells to deliver viral cDNA in MDBK cells. As shown in Fig. 2B, large amounts of infectious viruses were produced from the MDBK/293T (2:1) co-culture. Interestingly, the viral protein was detected only in MDBK cells and not in 293T cells. This suggests that, after cDNA was delivered to 293T cells by transfection reagents and RNA transcription began, low levels of virus were produced and/or viral RNA that was delivered into 293T cells passed to MDBK cells via cell-to-cell transmission (63) or exosomes (64). Further studies are needed to define how these co-cultured cell lines compensated for each other’s limitations to produce recombinant BVDV.

Although virus characterization is urgently needed in the event of an outbreak, viruses isolated from clinical specimens can fail to be amplified in cell culture due to contamination with other microorganisms and/or loss of infectivity during collection and storage. The CPER method only requires the generation of short PCR amplicons, and thus we examined whether it could be used to generate recombinant viruses from field samples. As shown in Fig. 2I and J, infectious virus was recovered from CPER assemblies made using fragments amplified directly from clinical specimens and exhibited properties similar to those of the clinical isolate. These findings indicate that the CPER method can omit not only molecular cloning but also virus isolation and could thus be especially useful when the rapid characterization of viral strains, such as during pandemics, is needed.

In summary, we adapted the CPER method using a gene cassette containing RNA Pol-I promoter and terminator sequence that is needed for efficient transcription of positive-strand RNA viruses that use IRES-mediated translation. The reverse genetics system described herein overcomes technical obstacles that have hindered the generation of recombinant viruses with IRES-mediated translation. We demonstrated that this modified CPER method could generate positive-strand RNA viruses with a type I, II, or III IRES. Although our methodology is useful for viruses with IRES-mediated translation, we have not yet used it for RNA viruses classified as having type IV IRES, which infect insects. We hope that other researchers will use these insect-infecting RNA viruses to investigate our methodology in the future. In addition, we showed proof-of-concept in using our modified CPER method for generating recombinant viruses derived not only from cell culture but also from clinical specimens. Taken together, our findings should contribute to promoting research on other RNA and DNA virus families through the engineering of recombinant viruses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids

A UTR linker containing a gene cassette encoding a murine RNA polymerase I terminator (GenBank accession number: AF441733.2), 165 bp spacer, and human RNA polymerase promoter (GenBank accession number: KY962518.1) was cloned into pCR-Blunt II-TOPO vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The cDNA EMCV VR-129B strain (GenBank accession number: KM269482) was synthesized by Thermo Fisher Scientific. The gene fragments were cloned into pCR vectors (sequence provided upon request). Sequences of all of the plasmids used in this study were confirmed by Sanger sequencing with SeqStudio Genetic Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and an outsourced service (Fasmac).

Cell lines

All mammalian cell lines were cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere and 5% CO2. Human hepatocellular carcinoma-derived Huh7 cells and human embryonic kidney-derived Lenti-X 293T cells (Takara Bio) were maintained in DMEM (Nacalai Tesque) supplemented with 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The Huh7-derived cell line Huh7.5.1 was kindly provided by Dr. Frank Chisari. The bovine kidney-derived MDBK cells were propagated in DMEM supplemented with 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, and 10% BVDV antibody-free FBS (Japan Bio Serum).

Antibodies and reagents

Anti-dsRNA (clone J2) and anti-HAV Vp3 (clone C22H) mouse monoclonal antibodies were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and Thermo Fisher Scientific, respectively. Alexa Fluor (AF) 488-conjugated anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG antibodies were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Rabbit anti-HCV NS5A antibody and anti-pestiviral NS3 antibody were generated as previously described (65, 66). Ribavirin was obtained from FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical for evaluation of antiviral efficacy.

Immunofluorescent assay

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Nacalai Tesque). After fixation, cells were permeabilized with PBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100 (Nacalai Tesque) for 10 min, blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin fraction V (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS, and then incubated with the indicated primary antibodies in PBS for 1 h at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere. After washing with PBS three times, cells were incubated with goat anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated (1:1,000 dilution) secondary antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were mounted with a VECTASHIELD mounting medium with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Vector Laboratories) and analyzed with a BZ-X700 fluorescence microscope (KEYENCE).

Luciferase assay

Luciferase activity was measured using a Nano-Glo HiBiT Lytic assay system (Promega) and AB-2270 Octa luminometer (ATTO), in accordance with the protocols provided by the manufacturers.

Preparation of viruses

HCV JFH-1 (26) (GenBank accession number: AB047639) carrying the adaptive mutations in cell culture (67), BVDV-1a No.12−/E (31) (GenBank accession number: LC068605), and BVDV-1a Nose (30) (GenBank accession number: AB078951) strains were kept in our laboratory. BVDV-1b Shihoro/B_6 strains (34) were prepared by inoculating MDBK cells with serum from persistently infected animals. HAV strain 18f (GenBank accession number: KP879216) was rescued from the infectious clone pT7-HM17518f, a gift from Dr. Stanley M. Lemon, as described previously (37). To generate recombinant viruses by CPER, viral RNA was purified using a PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The resultant RNA was used to synthesize cDNA with Superscript IV Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The fragments covering the entire genome of each virus were amplified using the respective primers (Tables S1 to S5) and KOD One DNA polymerase (Toyobo). The resulting DNA fragments were then mixed in equimolar amounts (0.1 pmol each) and their correct joining together was confirmed using two neighboring fragments by the responsible primer sets with PrimeSTAR GXL (Takara Bio) DNA polymerase. After verification, equal amounts of the DNA fragments were subjected to CPER with PrimeSTAR GXL DNA polymerase (initial 2 min of denaturation at 98°C; 20 cycles of 10 s at 98°C, 15 s at 55°C, and 12 min at 68°C; and final extension for 12 min at 68°C) to generate circular DNA. The CPER products were then transfected into the respective cell lines with Trans IT X2 transfection reagent (Mirus Bio). Then, we collected the supernatants from the transfected cells and the supernatants served as an inoculum for the naïve cells to propagate infectious viruses. The infectious titers of the prepared working virus were measured by a focus-forming unit (FFU) assay for HCV and HAV; 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) for BVDV; and a plaque-forming unit (PFU) assay for EMCV. The value of TCID50/mL was calculated using the Reed–Muench method (68). All of the viruses were stored at −80°C until use. The viral sequence of all recombinant viruses was determined by the Sanger method with SeqStudio Genetic Analyzer and/or an outsourced service. Sequencing primers can be provided upon request.

Virus replication kinetics

In vitro growth kinetics of the parental and recombinant viruses were evaluated in susceptible cell lines. In the case of HCV, Huh7.5.1 cells were inoculated at an MOI of 0.1. Cells were collected at 12, 24, 48, and 72 hpi and used to quantify intracellular viral RNA and measure luciferase activity. Supernatants were collected at 72 hpi for viral titration. The replication kinetics of BVDV were determined in MDBK cells after inoculation at an MOI of 0.01; cells and supernatants were collected at 12, 24, 48, and 72 hpi. Huh7 cells were inoculated with HAV or EMCV at an MOI of 0.01. Supernatants and cells were collected at 12, 24, 48, and 72 hpi for HAV, and 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, and 48 hpi for EMCV. Virus titers were determined in duplicate using the respective cell lines.

Quantitative RT-PCR

For the quantification of viral RNA copies, total RNA was extracted from cells using a PureLink RNA Mini Kit. First-strand cDNA synthesis and quantitative RT-PCR were performed using a TaqMan RNA-to-CT 1-Step kit for HCV, BVDV, and EMCV, and a One Step PrimeScript III RT-qPCR Mix kit for HAV, in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocols. For quantification of viral RNA, primer sets for the detection of a noncoding region were used as reported in previous studies (69–72). Fluorescent signals were acquired using the QuantStudio 5 Real-Time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or the StepOne Plus Real-Time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as the means ± standard deviations or standard errors. The significance of differences in the means was determined by Student’s t-test.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank H. Kubo, M. Tetsuka, and S. Shimamura for their secretarial work and H. Maruyama, M. Hanazaki, T. Matsuoka, R. Kudo, M. Hommura, A. Imajoh, and K. Oyama for their technical assistance. We thank Dr. Frank Chisari for providing Huh7.5.1 cells and Dr. Stanley M. Lemon for the HAV infectious cDNA clone.

This work was supported in part by AMED Research Program on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases (JP21fk0108617h0001 to Takasuke Fukuhara); AMED CREST (JP22gm1610008h0001 to Takasuke Fukuhara); JSPS KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research B (21H02736 to Takasuke Fukuhara); JSPS KAKENHI Fund for the Promotion of Joint International Research (International Leading Research) (JP23K20041 to Takasuke Fukuhara); JST SPRING, (JPMJSP2119 to Hirotaka Yamamoto); Takeda Science of Foundation (to Takasuke Fukuhara); Hokkaido University Support Program for Frontier Research (to Takasuke Fukuhara); Hokuto Foundation for Bioscience (to Tomokazu Tamura); and Kuribayashi Scholarship Academic Foundation (to Tomokazu Tamura).

Contributor Information

Takasuke Fukuhara, Email: fukut@pop.med.hokudai.ac.jp.

J.-H. James Ou, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The sequences of the virus strains used in this study have been deposited in GenBank with accession numbers AB047639, LC068605, AB078951, KP879216, and KM269482.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.01638-23.

Primer sets utilized for CPER.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Thomas SJ, Yoon IK. 2019. A review of Dengvaxia: development to deployment. Hum Vaccin Immunother 15:2295–2314. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1658503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yeh MT, Bujaki E, Dolan PT, Smith M, Wahid R, Konz J, Weiner AJ, Bandyopadhyay AS, Van Damme P, De Coster I, Revets H, Macadam A, Andino R. 2020. Engineering the live-attenuated polio vaccine to prevent reversion to virulence. Cell Host Microbe 27:736–751. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mueller S, Wimmer E. 1998. Expression of foreign proteins by poliovirus polyprotein fusion: analysis of genetic stability reveals rapid deletions and formation of cardioviruslike open reading frames. J Virol 72:20–31. doi: 10.1128/JVI.72.1.20-31.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Elliott G, O’Hare P. 1999. Live-cell analysis of a green fluorescent protein-tagged herpes simplex virus infection. J Virol 73:4110–4119. doi: 10.1128/JVI.73.5.4110-4119.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Manicassamy B, Manicassamy S, Belicha-Villanueva A, Pisanelli G, Pulendran B, García-Sastre A. 2010. Analysis of in vivo dynamics of influenza virus infection in mice using a GFP reporter virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:11531–11536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914994107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tamura T, Fukuhara T, Uchida T, Ono C, Mori H, Sato A, Fauzyah Y, Okamoto T, Kurosu T, Setoh YX, Imamura M, Tautz N, Sakoda Y, Khromykh AA, Chayama K, Matsuura Y. 2018. Characterization of recombinant Flaviviridae viruses possessing a small reporter tag. J Virol 92:01582–17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01582-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tamura T, Igarashi M, Enkhbold B, Suzuki T, Izumi T, Mori H, Ono C, Okamatsu M, Sato A, Fauzyah Y, Okamoto T, Sakoda Y, Fukuhara T, Matsuura Y. 2019. In vivo dynamics of reporter Flaviviridae viruses. J Virol 93:e01191-19. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01191-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hutchens M, Luker GD. 2007. Applications of bioluminescence imaging to the study of infectious diseases. Cell Microbiol 9:2315–2322. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00995.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lefkowitz EJ, Dempsey DM, Hendrickson RC, Orton RJ, Siddell SG, Smith DB. 2018. Virus taxonomy: the database of the international committee on taxonomy of viruses (ICTV). Nucleic Acids Res 46:D708–D717. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Morens DM, Fauci AS. 2020. Emerging pandemic diseases: how we got to COVID-19. Cell 182:1077–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bridgen A. 2012. Reverse genetics of RNA viruses: applications and perspectives. Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pierson TC, Diamond MS, Ahmed AA, Valentine LE, Davis CW, Samuel MA, Hanna SL, Puffer BA, Doms RW. 2005. An infectious West Nile virus that expresses a GFP reporter gene. Virology 334:28–40. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ruggli N, Rice CM. 1999. Functional cDNA clones of the Flaviviridae: strategies and applications. Adv Virus Res 53:183–207. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60348-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Quan J, Tian J. 2011. Circular polymerase extension cloning for high-throughput cloning of complex and combinatorial DNA libraries. Nat Protoc 6:242–251. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Edmonds J, van Grinsven E, Prow N, Bosco-Lauth A, Brault AC, Bowen RA, Hall RA, Khromykh AA. 2013. A novel bacterium-free method for generation of flavivirus infectious DNA by circular polymerase extension reaction allows accurate recapitulation of viral heterogeneity. J Virol 87:2367–2372. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03162-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Setoh YX, Prow NA, Rawle DJ, Tan CSE, Edmonds JH, Hall RA, Khromykh AA. 2015. Systematic analysis of viral genes responsible for differential virulence between American and Australian West Nile virus strains. J Gen Virol 96:1297–1308. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.000069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Setoh YX, Prow NA, Peng N, Hugo LE, Devine G, Hazlewood JE, Suhrbier A, Khromykh AA. 2017. De novo generation and characterization of new Zika virus isolate using sequence data from a microcephaly case. mSphere 2:e00190-17. doi: 10.1128/mSphereDirect.00190-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tamura T, Zhang J, Madan V, Biswas A, Schwoerer MP, Cafiero TR, Heller BL, Wang W, Ploss A. 2022. Generation and characterization of genetically and antigenically diverse infectious clones of dengue virus serotypes 1-4. Emerg Microbes Infect 11:227–239. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2021.2021808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Torii S, Ono C, Suzuki R, Morioka Y, Anzai I, Fauzyah Y, Maeda Y, Kamitani W, Fukuhara T, Matsuura Y. 2021. Establishment of a reverse genetics system for SARS-CoV-2 using circular polymerase extension reaction. Cell Rep 35:109014. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Amarilla AA, Sng JDJ, Parry R, Deerain JM, Potter JR, Setoh YX, Rawle DJ, Le TT, Modhiran N, Wang X, et al. 2021. A versatile reverse genetics platform for SARS-CoV-2 and other positive-strand RNA viruses. Nat Commun 12:3431. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23779-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hobson-Peters J, Harrison JJ, Watterson D, Hazlewood JE, Vet LJ, Newton ND, Warrilow D, Colmant AMG, Taylor C, Huang B, et al. 2019. A recombinant platform for flavivirus vaccines and diagnostics using chimeras of a new insect-specific virus. Sci Transl Med 11:522. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aax7888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Conde JN, Himmler GE, Mladinich MC, Setoh YX, Amarilla AA, Schutt WR, Saladino N, Gorbunova EE, Salamango DJ, Benach J, Kim HK, Mackow ER. 2023. Establishment of a CPER reverse genetics system for Powassan virus defines attenuating NS1 glycosylation sites and an infectious NS1-GFP11 reporter virus. mBio 14:e0138823. doi: 10.1128/mbio.01388-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kieft JS. 2008. Viral IRES RNA structures and ribosome interactions. Trends Biochem Sci 33:274–283. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jaafar ZA, Kieft JS. 2019. Viral RNA structure-based strategies to manipulate translation. Nat Rev Microbiol 17:110–123. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0117-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tsukiyama-Kohara K, Iizuka N, Kohara M, Nomoto A. 1992. Internal ribosome entry site within hepatitis C virus RNA. J Virol 66:1476–1483. doi: 10.1128/JVI.66.3.1476-1483.1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wakita T, Pietschmann T, Kato T, Date T, Miyamoto M, Zhao Z, Murthy K, Habermann A, Kräusslich H-G, Mizokami M, Bartenschlager R, Liang TJ. 2005. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nat Med 11:791–796. doi: 10.1038/nm1268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dixon AS, Schwinn MK, Hall MP, Zimmerman K, Otto P, Lubben TH, Butler BL, Binkowski BF, Machleidt T, Kirkland TA, Wood MG, Eggers CT, Encell LP, Wood KV. 2016. NanoLuc complementation reporter optimized for accurate measurement of protein interactions in cells. ACS Chem Biol 11:400–408. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Poole TL, Wang C, Popp RA, Potgieter LN, Siddiqui A, Collett MS. 1995. Pestivirus translation initiation occurs by internal ribosome entry. Virology 206:750–754. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(95)80003-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Peterhans E, Bachofen C, Stalder H, Schweizer M. 2010. Cytopathic bovine viral diarrhea viruses (BVDV): emerging pestiviruses doomed to extinction. Vet Res 41:44. doi: 10.1051/vetres/2010016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nagai M, Sakoda Y, Mori M, Hayashi M, Kida H, Akashi H. 2003. Insertion of cellular sequence and RNA recombination in the structural protein coding region of cytopathogenic bovine viral diarrhoea virus. J Gen Virol 84:447–452. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18773-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shimazaki T, Sekiguchi H, Nakamura S, Taguchi K, Inoue Y, Satoh M. 1998. Segregation of bovine viral diarrhea virus isolated in Japan into genotypes. J Vet Med Sci 60:579–583. doi: 10.1292/jvms.60.579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Osorio JS, Bionaz M. 2017. Plasmid transfection in bovine cells: optimization using a realtime monitoring of green fluorescent protein and effect on gene reporter assay. Gene 626:200–208. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. DuBridge RB, Tang P, Hsia HC, Leong PM, Miller JH, Calos MP. 1987. Analysis of mutation in human cells by using an Epstein-Barr virus shuttle system. Mol Cell Biol 7:379–387. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.1.379-387.1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hirose S, Notsu K, Ito S, Sakoda Y, Isoda N. 2021. Transmission dynamics of bovine viral diarrhea virus in Hokkaido Japan by phylogenetic and epidemiological network approaches. Pathogens 10:922. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10080922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mailliot J, Martin F. 2018. Viral internal ribosomal entry sites: four classes for one goal. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 9. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Glass MJ, Jia XY, Summers DF. 1993. Identification of the hepatitis A virus internal ribosome entry site: in vivo and in vitro analysis of bicistronic RNAs containing the HAV 5' noncoding region. Virology 193:842–852. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang H, Chao SF, Ping LH, Grace K, Clarke B, Lemon SM. 1995. An infectious cDNA clone of a cytopathic hepatitis A virus: genomic regions associated with rapid replication and cytopathic effect. Virology 212:686–697. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Beard MR, Cohen L, Lemon SM, Martin A. 2001. Characterization of recombinant hepatitis A virus genomes containing exogenous sequences at the 2A/2B junction. J Virol 75:1414–1426. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.3.1414-1426.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Patterson JL, Fernandez-Larsson R. 1990. Molecular mechanisms of action of ribavirin. Rev Infect Dis 12:1139–1146. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.6.1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jang SK, Kräusslich HG, Nicklin MJ, Duke GM, Palmenberg AC, Wimmer E. 1988. A segment of the 5' nontranslated region of encephalomyocarditis virus RNA directs internal entry of ribosomes during in vitro translation. J Virol 62:2636–2643. doi: 10.1128/JVI.62.8.2636-2643.1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lapointe J, Brakier-Gingras L. 2003. Translation mechanisms, p 446. In Molecular biology intelligence unit. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cross ST, Michalski D, Miller MR, Wilusz J. 2019. RNA regulatory processes in RNA virus biology. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 10:e1536. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pelletier J, Sonenberg N. 1988. Internal initiation of translation of eukaryotic mRNA directed by a sequence derived from poliovirus RNA. Nature 334:320–325. doi: 10.1038/334320a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cho EJ, Takagi T, Moore CR, Buratowski S. 1997. mRNA capping enzyme is recruited to the transcription complex by phosphorylation of the RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain. Genes Dev 11:3319–3326. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Masaki T, Suzuki R, Saeed M, Mori K, Matsuda M, Aizaki H, Ishii K, Maki N, Miyamura T, Matsuura Y, Wakita T, Suzuki T. 2010. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus by using RNA polymerase I-mediated transcription. J Virol 84:5824–5835. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02397-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cai Z, Zhang C, Chang K-S, Jiang J, Ahn B-C, Wakita T, Liang TJ, Luo G. 2005. Robust production of infectious hepatitis C virus (HCV) from stably HCV cDNA-transfected human hepatoma cells. J Virol 79:13963–13973. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.13963-13973.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Khan MA, Miyoshi H, Gallie DR, Goss DJ. 2008. Potyvirus genome-linked protein, VPg, directly affects wheat germ in vitro translation: interactions with translation initiation factors eIF4F and eIFiso4F. J Biol Chem 283:1340–1349. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703356200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Neumann G, Watanabe T, Ito H, Watanabe S, Goto H, Gao P, Hughes M, Perez DR, Donis R, Hoffmann E, Hobom G, Kawaoka Y. 1999. Generation of influenza A viruses entirely from cloned cDNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:9345–9350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Groseth A, Feldmann H, Theriault S, Mehmetoglu G, Flick R. 2005. RNA polymerase I-driven minigenome system for Ebola viruses. J Virol 79:4425–4433. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.4425-4433.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Flick R, Flick K, Feldmann H, Elgh F. 2003. Reverse genetics for crimean-congo hemorrhagic fever virus. J Virol 77:5997–6006. doi: 10.1128/jvi.77.10.5997-6006.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Flick R, Pettersson RF. 2001. Reverse genetics system for Uukuniemi virus (Bunyaviridae): RNA polymerase I-catalyzed expression of chimeric viral RNAs. J Virol 75:1643–1655. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.4.1643-1655.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Weiner AJ, Brauer MJ, Rosenblatt J, Richman KH, Tung J, Crawford K, Bonino F, Saracco G, Choo QL, Houghton M. 1991. Variable and hypervariable domains are found in the regions of HCV corresponding to the flavivirus envelope and NS1 proteins and the pestivirus envelope glycoproteins. Virology 180:842–848. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90104-j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hijikata M, Kato N, Ootsuyama Y, Nakagawa M, Ohkoshi S, Shimotohno K. 1991. Hypervariable regions in the putative glycoprotein of hepatitis C virus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 175:220–228. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81223-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ogata N, Alter HJ, Miller RH, Purcell RH. 1991. Nucleotide sequence and mutation rate of the H strain of hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88:3392–3396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Higashi Y, Kakumu S, Yoshioka K, Wakita T, Mizokami M, Ohba K, Ito Y, Ishikawa T, Takayanagi M, Nagai Y. 1993. Dynamics of genome change in the E2/NS1 region of hepatitis C virus in vivo. Virology 197:659–668. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kao JH, Chen PJ, Lai MY, Wang TH, Chen DS. 1995. Quasispecies of hepatitis C virus and genetic drift of the hypervariable region in chronic type C hepatitis. J Infect Dis 172:261–264. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.1.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kato N, Ootsuyama Y, Sekiya H, Ohkoshi S, Nakazawa T, Hijikata M, Shimotohno K. 1994. Genetic drift in hypervariable region 1 of the viral genome in persistent hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol 68:4776–4784. doi: 10.1128/JVI.68.8.4776-4784.1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Weiner AJ, Geysen HM, Christopherson C, Hall JE, Mason TJ, Saracco G, Bonino F, Crawford K, Marion CD, Crawford KA. 1992. Evidence for immune selection of hepatitis C virus (HCV) putative envelope glycoprotein variants: potential role in chronic HCV infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89:3468–3472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yamaguchi K, Tanaka E, Higashi K, Kiyosawa K, Matsumoto A, Furuta S, Hasegawa A, Tanaka S, Kohara M. 1994. Adaptation of hepatitis C virus for persistent infection in patients with acute hepatitis. Gastroenterology 106:1344–1348. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90029-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Han R, Liang L, Qin T, Xiao S, Liang R. 2022. Encephalomyocarditis virus 2A protein inhibited apoptosis by interaction with annexin A2 through JNK/C-Jun pathway. Viruses 14:359. doi: 10.3390/v14020359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sadic M, Schneider WM, Katsara O, Medina GN, Fisher A, Mogulothu A, Yu Y, Gu M, de Los Santos T, Schneider RJ, Dittmann M. 2022. DDX60 selectively reduces translation off viral type II internal ribosome entry sites. EMBO Rep 23:e55218. doi: 10.15252/embr.202255218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Thiel HJ, Plagemann PGW, Moenning V. 1996. Pestiviruses, p 1059–1073. In Fields BN, Knipe DM, Howley PM (ed), Fields virology, 3rd ed. Vol. 11. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Mothes W, Sherer NM, Jin J, Zhong P. 2010. Virus cell-to-cell transmission. J Virol 84:8360–8368. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00443-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Meckes DG. 2015. Exosomal communication goes viral. J Virol 89:5200–5203. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02470-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Moriishi K, Shoji I, Mori Y, Suzuki R, Suzuki T, Kataoka C, Matsuura Y. 2010. Involvement of PA28gamma in the propagation of hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 52:411–420. doi: 10.1002/hep.23680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kameyama K, Sakoda Y, Tamai K, Igarashi H, Tajima M, Mochizuki T, Namba Y, Kida H. 2006. Development of an immunochromatographic test kit for rapid detection of bovine viral diarrhea virus antigen. J Virol Methods 138:140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Russell RS, Meunier J-C, Takikawa S, Faulk K, Engle RE, Bukh J, Purcell RH, Emerson SU. 2008. Advantages of a single-cycle production assay to study cell culture-adaptive mutations of hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:4370–4375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800422105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Reed LJ, Muench H. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am J Hyg 27:493–497. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a118408 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Takeuchi T, Katsume A, Tanaka T, Abe A, Inoue K, Tsukiyama-Kohara K, Kawaguchi R, Tanaka S, Kohara M. 1999. Real-time detection system for quantification of hepatitis C virus genome. Gastroenterology 116:636–642. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70185-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. La Rocca SA, Sandvik T. 2009. A short target real-time RT-PCR assay for detection of pestiviruses infecting cattle. J Virol Methods 161:122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Jothikumar N, Cromeans TL, Sobsey MD, Robertson BH. 2005. Development and evaluation of a broadly reactive TaqMan assay for rapid detection of hepatitis A virus. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:3359–3363. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.6.3359-3363.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Qin S, Underwood D, Driver L, Kistler C, Diallo I, Kirkland PD. 2018. Evaluation of a duplex reverse-transcription real-time PCR assay for the detection of encephalomyocarditis virus. J Vet Diagn Invest 30:554–559. doi: 10.1177/1040638718779112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Primer sets utilized for CPER.

Data Availability Statement

The sequences of the virus strains used in this study have been deposited in GenBank with accession numbers AB047639, LC068605, AB078951, KP879216, and KM269482.