Abstract

This article reports on speech-language pathologists’ (SLPs’) knowledge related to myths about spoken language learning of children who are deaf and hard of hearing (DHH). The broader study was designed as a step toward narrowing the research-practice gap and providing effective, evidence-based language services to children. In the broader study, SLPs (n = 106) reported their agreement/disagreement with myth statements and true statements (n = 52) about 7 clinical topics related to speech and language development. For the current report, participant responses to 7 statements within the DHH topic were analyzed. Participants exhibited a relative strength in bilingualism knowledge for spoken languages and a relative weakness in audiovisual integration knowledge. Much individual variation was observed. Participants’ responses were more likely to align with current evidence about bilingualism if the participants had less experience as an SLP. The findings provide guidance on prioritizing topics for speech-language pathology preservice and professional development.

Introduction

Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) are called to provide high-quality, evidence-based services to a wide variety of individuals with communication needs. SLPs need to access, interpret, and apply the extant and evolving evidence related to speech and language development as it becomes available. Doing so is necessary to provide effective, evidence-based interventions. Keeping current on the evidence, especially for low-incidence diagnoses, can be challenging for SLPs. Approximately 2–3 of every 1,000 children born in the United States are deaf and hard of hearing (DHH; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010; Vohr, 2003). Given this incidence level, an SLP may experience a period of time in which their caseload does not include any children who are DHH. However, that could change at any time, especially for school SLPs who typically serve all children receiving speech and language services within their assigned school(s).

Revealing SLPs’ current understanding related to language development in children who are DHH is essential to determining whether and what types of support SLPs need so that they can provide effective, evidence-based language services to children who are DHH. Many SLPs, including those who serve children who are DHH, express lower-than-desirable comfort levels with serving the DHH population (Blaiser & Mahshie, 2022; Harrison et al., 2016). Reported comfort levels were especially low for children who are DHH under age 3 and for certain practice areas (e.g., sign language development and troubleshooting hearing technology). Such perceived and true areas of need could place SLPs at risk for providing services that are not evidence-based.

The current report was a step toward narrowing the research–practice gap and providing effective, evidence-based services to children who are DHH. We aimed to determine the degree to which SLPs endorse or reject statements related to myths about spoken language learning of children who are DHH. We focus on myths because myths provide an opportunity to identify areas of SLPs’ thinking or practice that do not align with current evidence. Further, myths can be addressed or countered via supports or interventions for SLPs. In this report, we specifically focused on myths from three subtopics related to whether and how speech-language intervention services are provided to children who are DHH and learning to use spoken language. We focus on spoken language because of (a) the likelihood of SLPs interacting with DHH children who use spoken language outside of schools specific for children who are DHH and (b) the ability to compare results for children who are DHH with results for other populations for certain myths.

The first subtopic addresses whether children who are DHH can be bilingual for spoken languages. The myth that bilingualism has a negative impact on language development is pervasive, not only related to children who are DHH but also other populations. Addressing bilingualism specifically for spoken languages enables us to compare perspectives about this myth for children who are DHH relative to other populations who primarily use spoken languages. SLPs’ perspectives on bilingualism are expected to influence recommendations they provide to families for which language(s) to use and which language(s) are used in intervention.

The second subtopic addresses the use of hearing technology and how the use of hearing technology influences speech and language abilities and need of intervention services. SLPs need an accurate understanding of the potential benefits and limitations of hearing technology to provide needed educational supports and refer students to an audiologist to explore hearing technology adjustments.

The third subtopic addresses audiovisual integration for speech perception. Consistent with the focus on spoken language, we address how auditory input and visual input from the speech articulators interact for understanding speech. SLPs’ perspectives on audiovisual input are expected to influence the use of certain spoken language intervention techniques and thereby the effectiveness of intervention.

Bilingualism for spoken languages

One widespread myth about bilingualism asserts that learning two languages can confuse a child. According to this myth, if a child who is learning two languages is slower than peers in learning to talk, the child should only be exposed to one language to alleviate the confusion, thereby improving the child’s language skills. This recommendation seemingly is made without regard to the languages used by the child’s family and community (Blanc et al., 2022; Guiberson, 2013a; Yu, 2013). Within the United States, the suggested language to use in such cases is almost always English even if the child’s family uses another language more, or solely, at home (Blanc et al., 2022; Yu, 2013). This myth has influenced services not only for children who are DHH but also for children with autism spectrum disorder, Down syndrome, and specific language impairment (Kay-Raining Bird et al., 2005; Paradis et al., 2003; Wharton et al., 2000; Yu, 2013). In this study, we were focused particularly on bilingualism in children who use two spoken (oral) languages. Questions regarding use of signed and spoken languages are also important (Steinberg et al., 2003) but were beyond the scope of this study.

This myth about bilingualism being confusing or slowing the pace of a child’s language development is not supported by current evidence. In fact, there is substantial evidence against this myth. Counter to this pervasive myth, bilingualism yields positive effects for language learning (Kay-Raining Bird et al., 2005, 2012; Perozzi & Sanchez, 1992; Seung et al., 2006; Thordardottir et al., 1997) as well as cultural awareness and identity (Yu, 2013; Zentella, 1997). Additionally, monolingual children with disabilities (e.g., autism spectrum disorder, DHH, Down syndrome, and specific language impairment) do not outperform their bilingual peers with the same diagnosis (Bird et al., 2005; Bunta & Douglas, 2013; Feltmate & Kay-Raining Bird, 2008; Guiberson, 2013a; Ohashi et al., 2012; Paradis et al., 2003; Petersen et al., 2012). If bilingualism is an added burden for learning language, one would expect weaker language skills across bilingual children as compared with monolingual children. The available empirical evidence does not yield such results. Further, children who use cochlear implants (CIs) have shown strong performance in a second spoken language (McConkey Robbins et al., 2004; Waltzman et al., 2003).

A few studies document the pervasiveness of this bilingualism myth specifically for children who are DHH. Guiberson (2013b) surveyed parents of children who are DHH in Spain to investigate the pervasiveness of the myth that children who are DHH will be confused by learning two languages and therefore cannot be bilingual. The 71 surveyed parents reported their beliefs and practices regarding bilingualism for themselves and their children. Among other questions, the survey included three questions about their beliefs of raising children who are DHH to use two spoken languages. An apparent discrepancy between the parents’ beliefs and practices was revealed. Although most parents (more than 80%) expressed that bilingualism is natural and beneficial and that children who are DHH can learn two spoken languages, only 38% were raising their children who are DHH to use two spoken languages.

In a related study, Benítez-Barrera et al. (2023) surveyed caregivers of children who are DHH who speak Spanish and live in the United States. Caregivers were asked about the recommendations professionals and nonprofessionals had provided to them about using two spoken languages with their children who are DHH. Caregivers reported whether they were only encouraged to use two spoken languages, were only discouraged from using two spoken languages, were given mixed advice, or received no recommendation. Only 23% of caregivers reported only being encouraged to use two spoken languages with their children by professionals (e.g., audiologists, deaf educators, otolaryngologists, physicians, SLPs, and teachers). In contrast, 45% of caregivers reported that nonprofessionals (e.g., family, friends, and community support) only encouraged them to do so. Remarkably, 6% of caregivers reported only being discouraged from using two spoken languages with their children from professionals. No caregivers reported being only discouraged by nonprofessionals. Some caregivers received mixed advice from professionals (12%) and nonprofessionals (10%). These findings highlight that professionals are not serving as experts in the provision of current evidence.

We aim to extend these findings on the pervasiveness of the myth that children who are DHH cannot learn two spoken languages to SLPs specifically. SLPs are often involved in counseling parents on the possible language options for children who are DHH (Blanc et al., 2022). Therefore, SLPs are in a position to potentially combat this myth, if they have the necessary knowledge and skills to do so.

Hearing technology

To best serve children who are DHH, SLPs must be knowledgeable about the benefits and limitations of hearing technology as well as the educational impact of reduced auditory access. If an SLP assumes that hearing technology is all that is needed to achieve educational success, that SLP misses opportunities to provide needed educational supports. Alternatively, failing to recognize the myriad benefits of hearing technology for children who are DHH and use spoken language may lead SLPs to disregard signs that a child needs to be referred to an audiologist for new hearing technology or modifications to their existing hearing technology.

Appropriately-fit hearing technology can provide substantial benefits for children who are DHH with varied hearing levels (Geers et al., 2003; McCreery et al., 2015; Svirsky et al., 2000; Tomblin et al., 2015; Walker et al., 2015). Unfortunately, simply wearing hearing aids or CIs does not ensure that a child has full auditory access to language and the general education curriculum. Many children who are DHH, including children who use hearing technology, continue to exhibit difficulty achieving age-expected language skills (Antia et al., 2020; Boons et al., 2013; Dettman et al., 2013; Geers et al., 2017; Geers & Sedey, 2011; Harris & Terlektsi, 2011; Kyle & Harris, 2011; Lund, 2016; Nittrouer et al., 2020; Ruben, 2018). Audibility, “the proportion of the speech signal that is audible,” is one influential factor on spoken language outcomes (McCreery et al., 2014, p. 440). Well-fit hearing technology supports audibility and, in turn, supports spoken language outcomes, but it is far from the only factor that matters (McCreery et al., 2019; Tomblin et al., 2015).

An influential factor on language outcomes for children who receive CIs is age of implantation. Children who are eligible for cochlear implantation benefit from being implanted at younger ages relative to older ages (Colletti et al., 2011; Dettman et al., 2007; Nicholas & Geers, 2013). Observed benefits include higher language skills before entering school for children implanted relatively young (i.e., 6–11 months vs. 12–18 months of age; Nicholas & Geers, 2013) and earlier attainment of age-expected expressive language growth rates (Tomblin et al., 2005). Thus, replicated findings support higher language skills for children who receive CIs at younger ages compared with older ages.

Audiovisual integration for speech perception

Knowledge of audiovisual integration, especially for children who are DHH, has implications for how SLPs structure intervention. Spoken word recognition often is treated as a unisensory auditory process, even though it is a multisensory process under natural conditions (Holt et al., 2011). A listener receives not only auditory input from conversational partners but also visual input from the movement of the partners’ articulators1. Auditory input is especially influential for perceiving the manner of articulation and voicing, whereas visual input is especially influential for perceiving the place of articulation (Eisenberg, 1985; Grant & Seitz, 1998; Rouger et al., 2008; Rudner et al., 2016). Speech processing, including word recognition, is enhanced with multisensory input compared with unisensory input for individuals with typical hearing (Erber, 1969, 1972; Kim & Davis, 2003; Reisberg et al., 1987; Sumby & Pollack, 1954) and individuals who are DHH (Bergeson et al., 2005; Grant & Seitz, 1998; Kaiser et al., 2003; Kirk et al., 2002, 2007; Lachs et al., 2001). Individuals with typical hearing repeatedly have shown benefit from access to speechreading cues under relatively more difficult listening conditions such as low signal-to-noise ratios (Erber, 1969, 1972; Sumby & Pollack, 1954) or an unfamiliar language or accent (Kim & Davis, 2003; Reisberg et al., 1987). Even infants show a preference for congruent rather than incongruent auditory and visual input (Dodd, 1979; Patterson & Werker, 2003). Individuals who are DHH also demonstrate greater word recognition when provided with multisensory input as compared to auditory or visual input alone (Bergeson et al., 2005; Grant & Seitz, 1998; Kaiser et al., 2003; Kirk et al., 2002, 2007; Lachs et al., 2001). Variation in audiovisual integration for speech perception has been observed among children with CIs; age of implantation, language skills, and speech intelligibility have been identified as factors that relate to this variation (Bergeson et al., 2003; Gilley et al., 2010; Kirk et al., 2002; Schorr et al., 2005).

The multisensory processing of speech appears to contraindicate unisensory approaches for training auditory skills in children who are DHH. Unisensory approaches focus on isolating auditory input and limiting visual cues to prevent vision, which is unimpaired, from being “victorious” over audition, which is limited in acuity (Pollack, 1970, p. 18). Unisensory approaches emerged in the United States in the 1930s to 1970s prior to the availability of modern hearing aids and CIs. In subsequent decades, strategies for isolating auditory input for speech processing have evolved. Use of the hand cue (i.e., speaker covering mouth with flat hand; Estabrooks, 2001) has been reduced. However, use of speech hoops, strategic sitting (e.g., sitting behind or beside the child), and visual distractors (e.g., speaking when a child is looking at an object rather than the speaker’s face) to minimize access to visual speechreading cues remain as recommendations within auditory-only approaches (Estabrooks, 2001; Rhoades et al., 2016; Robbins, 2016). A lack of awareness of the more recent multisensory processing findings may result in SLPs restricting access to visual input during intervention in a manner that hampers progress.

Purpose of current study report

This report explored the extent to which SLPs agree or disagree with myths about spoken language learning of children who are DHH. We specifically focused on myths about bilingualism for spoken languages, the use of hearing technology, and audiovisual integration of children who are DHH. This early-stage study is intended to inform future work that addresses identified gaps in SLPs’ knowledge so that SLPs provide effective, evidence-based intervention services to children who are DHH and learning to use spoken language.

Research questions

We addressed two research questions. We first asked the following: (a) To what extent do SLPs endorse or reject true statements and false (i.e., myth) statements related to children who are DHH? To explore differences in knowledge across SLPs, we then asked: (b) Do years of speech-language pathology experience correlate with the degree to which SLPs’ responses align with current evidence? Due to limited evidence, we did not generate specific hypotheses.

Methods

The Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

Participants

Participants were recruited electronically in July and August 2020 from 338 registered attendees (primarily SLPs and SLP graduate students) of an online 2-day statewide professional development conference focused on the educational needs of school SLPs and a large lab database of SLPs. The conference attracts a relatively large number of SLPs from varied urban and rural counties. The database included SLPs who attended speech, language, and literacy professional development sponsored by Vanderbilt University Medical Center. In response to invitations sent via conference emails and verbal announcements, 155 individuals expressed interest in participating. They received access to the consent form and study survey. Of those 155 individuals, 106 SLPs (103 females, 3 males) completed the consent and study survey; 3 SLPs completed the consent but abandoned the survey; and 31 SLPs did not access the consent or study survey. Fifteen graduate students also completed the survey. However, their responses are not included in this report due to space limitations for thorough analysis of their responses relative to the SLPs’ responses.

At the beginning of the survey, participants reported demographic information. Only 1 of the 106 SLPs was not currently employed as an SLP. The participants had a mean age of 38 years (SD = 11 years; range: 23–68 years) with a mean years of speech-language pathology experience of 12 (SD = 10 years; range: 0–43 years; n = 103). Three participants did not report their years of experience. One participant reported a value exceeding their chronological age; this value was excluded. Seventy-four participants (70%) reported working currently in a school setting, which is expected given that the conference from which participants were recruited focuses on the needs of school SLPs. Three participants did not report whether they worked in a school. The other 29 participants reported not working in school currently. The participants had a mean of 9.00 years (SD = 8.43 years; range: 0–38 years) of experience as a school SLP. Most participants (n = 85) worked in Tennessee; 20 were from 14 other states, and 1 participant lived outside of the United States. For highest degree earned, 101 participants reported a master’s degree and 5 reported a doctorate. Twelve participants reported being bilingual or multilingual. French (n = 4) and Spanish (n = 4) were the most common non-English languages used, followed by American Sign Language (n = 3). Other reported languages were German (n = 1), Portuguese (n = 1), and Vietnamese (n = 1).

The current sample’s racial profile is similar to that of national demographic data from American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) members, nonmember certificate holders, international affiliates, and associates certified in speech-language pathology. It should be noted that, for this report, we calculated categorical percentages based on the total number of participants who provided race information (three did not provide information). We did not use the full sample because 14% of the national sample did not provide race information and were not included in ASHA’s categorical percentages. Ninety-eight participants (94%) identified as white, three (2.9%) as Black or African American, two (1.9%) as Asian, and one (1.0%) as more than one race. For the national sample, 91.3% identified as White, 3.6% as Black or African American, 3.1% as Asian, and 1.5% as more than one race (ASHA, 2022). The participant sample included a similar percentage of females as the national sample (i.e., 98% vs. 96%; ASHA, 2022). Regarding ethnicity of the participant sample, 101 participants reported to be non-Hispanic, 3 participants preferred not to answer, and 2 did not provide a response. For the national sample, 6% reported being Hispanic (ASHA, 2022). We cannot compare the study participants’ ethnicity and race proportions to those of the total conference attendees because we do not collect ethnicity and race information from conference registrants.

Survey development and format

The authors and several research assistants developed an initial survey draft based on the relevant literature, including results from published studies (e.g., Guiberson, 2013b) to utilize prior validation processes, improve validity, and provide an opportunity for replication (Rickards et al., 2012). We followed survey development practices of minimizing negative statements and avoiding double-barreled items (Dillman et al., 2009; Tourangeau et al., 2000). We included both true and false statements related to myths to minimize the likelihood that respondents would simply disagree (or agree) with every statement. We sought to avoid participants guessing that disagreeing was the “right” answer based on a few statements and then marking disagree for all statements regardless of their true perspectives. Through an iterative piloting process, practicing SLPs and SLP graduate students (master’s and PhD) provided feedback. We identified and edited confusing phrasings and estimated the time required to complete the survey (15 min; Sullivan & Artino Jr., 2017). Phrases were deemed as confusing for a variety of reasons including use of unfamiliar or unknown terms, possible alternative interpretation provided, or multiple interpretations reported.

The final study survey included 3–15 statements for each of seven topics presented in alphabetical order: bilingualism, autism spectrum disorder, DHH, dyslexia, language development, speech–language impairment, and vocal development/babbling. These seven topics were selected because (a) they relate to speech, language, and literacy; (b) they are expected to be familiar to and important for SLPs serving children, including but not limited to school SLPs; and (c) we have encountered these myths in clinical and educational settings (e.g., caregivers sharing experiences about information they received, students asking questions from conversations or clinical practicum experiences). The survey concluded by asking participants to report professional development resources that they use in a typical school year. See McDaniel et al. (2023) and Krimm et al. (2023) for additional findings.

We chose to use a visual analogue scale to increase the variance across participants and to increase sensitivity to change compared with discrete Likert-style and verbal rating scales (Briggs & Closs, 1999; Hasson & Arnetz, 2005; Pfennings et al., 1995). Participants were presented with written statements and asked to move the slider to mark the extent to which they agree or disagree with each statement. See Figure 1 for two example statements. Consistent with best practices for electronic administration of visual analogue scales, all scales were displayed horizontally and appeared with the statement on the same screen (Byrom et al., 2022). Participants could select a location on the scale by tapping the line in a specific location or by sliding the slider. The first statement in Figure 1 illustrates a participant’s answer, having moved the slider to the right to indicate general but not total agreement with the statement; the second statement illustrates how a statement appears before the participant marks their response. As displayed in Figure 1, the anchor of “strongly disagree” appears at the far left side of the scale and the “strongly agree” appears at the far right. No additional anchors were provided.

Figure 1.

Example visual analogue scale questions from the survey.

DHH survey items

In this report, we focus on the seven statements (two true and five myth statements) related to spoken language learning of children who are DHH. These statements address the subtopics of bilingualism, hearing technology, and audiovisual integration for children who are DHH. Two or three statements related to each subtopic.

Survey administration

Participants completed the survey electronically via Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap; Harris et al., 2009, 2019), which is a web application developed by Vanderbilt University. REDCap is used to build and manage online surveys and databases. Prior to answering study questions, participants reviewed the consent form within REDCap. If they electronically agreed to participate, they sequentially completed the nine survey sections: demographic information (one section), ratings for true and myth statements arranged by seven topics (seven sections), and description of professional development resources that they access in a typical year (one section). Participants were permitted to return to prior sections before submitting the survey.

Data processing and analysis plan

Some participants did not respond for all statements, resulting in 103–105 responses per statement. For each statement, each participant earned an endorsement score from 0 (“strongly disagree”) to 100 (“strongly agree”) based on where the participant placed the slider on the line. Scores between 51 and 100 indicate movement of the slider to the right (i.e., toward “strongly agree”). Scores in this range align with the current evidence for a true statement but do not align with the current evidence for a myth statement. Scores between 0 and 49 indicate movement to the left (i.e., toward “strongly disagree”). Scores in this range align with the current evidence for a myth statement but do not align with the current evidence for a true statement. The participants never saw these numbers. The numbers only exist in an underlying metric.

We display the distribution of responses on a histogram for each statement. Using a one-sample t-test, we tested whether the mean endorsement score differed from the neutral midpoint (i.e., score of 50). We calculated an effect size, d, for each statement (Francis & Jakicic, 2022). Visual analogue scale results permit these parametric analyses (Maxwell, 1978; Myles et al., 1999). We identify relative strengths and weaknesses across the statements based on the distributions, t-test results, and effect sizes.

We also tested for significant correlations between endorsement scores and years of speech-language pathology experience. The current evidence aligns with high endorsement scores for true statements and low scores for myth statements. Therefore, interpretation for the direction of correlation differs for true versus myth statements. For true statements, positive correlations align with SLPs’ knowledge about evidence-based practices increasing as they work as SLPs. Negative correlations for true statements align with SLPs not staying current on evidence-based practices and with implementing outdated ideas or practices. In contrast, for myth statements, positive correlations align with SLPs not staying current on evidence-based practices and with implementing outdated ideas or practices. Negative correlations for myth statements align with SLPs’ knowledge about evidence-based practices increasing as they work as SLPs.

Results

Endorsement scores across statements

The survey included two true statements and five myth statements related to spoken language learning of children who are DHH. Table 1 displays descriptive statistics, a one-sample t-test result, and an effect size (Francis & Jakicic, 2022) for the endorsement scores for each statement across participants. Given the seven dependent variables, p-values < .007 are statistically significant with the Bonferroni correction to address family-wise error (Nicholson et al., 2022). For the effect size (d), .2 is considered small, .5 is considered medium, and .8 is considered large (Cohen, 1988).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics, one-sample t-test (vs. 50) results, and correlations with SLP experience for SLPs’ endorsement scores.

| One sample t-test | Correlation with SLP experience | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statement | True or myth | Mean (SD) | Range | n | t | p | d | r | p |

| Bilingualism | |||||||||

| Children who are deaf and hard of hearing have the capacity to develop skills in two oral languages. | True | 75 (20) | 19–100 | 105 | 13.09* | <.001 | 1.28 | −.23 | .02 |

| Children who are deaf and hard of hearing will be confused by being exposed to two oral languages. | Myth | 25 (20) | 0–81 | 105 | −12.84* | <.001 | 1.25 | .29 | .003 |

| Learning two oral languages is too great of a challenge for children who are deaf and hard of hearing. | Myth | 24 (19) | 0–83 | 104 | −14.03* | <.001 | 1.38 | .45* | <.001 |

| Hearing technology | |||||||||

| Pediatric cochlear implant candidates who undergo cochlear implantation at relatively young ages are expected to achieve higher speech and language outcomes than candidates who undergo implantation at relatively older ages. | True | 73 (19) | 0–100 | 105 | 12.50* | <.001 | 1.22 | −.13 | .20 |

| School-age children who are deaf and hard of hearing who use spoken language and are fit appropriately with hearing technology likely do not need additional education services. | Myth | 24 (18) | 0–100 | 104 | −14.22* | <.001 | 1.39 | −.05 | .59 |

| Audiovisual integration | |||||||||

| Children who are deaf and hard of hearing develop their auditory skills more during language intervention sessions if they cannot see the person talking than if they can. | Myth | 45 (26) | 0–100 | 103 | −1.85 | .07 | 0.18 | −.12 | .25 |

| Children who are deaf and hard of hearing will become overly reliant on visual cues if they are not taught to listen. | Myth | 46 (22) | 0–100 | 105 | −1.97 | .05 | 0.19 | −.004 | .97 |

Note. A score of 0 corresponds to the anchor of “strongly disagree” and 100 corresponds to the anchor of “strongly agree” on the visual analogue scale. d = effect size (Francis & Jakicic, 2022). SLP = speech-language pathologist.

*Statistically significant with the Bonferroni correction to address family-wise error (i.e., p < .007; Nicholson et al., 2022).

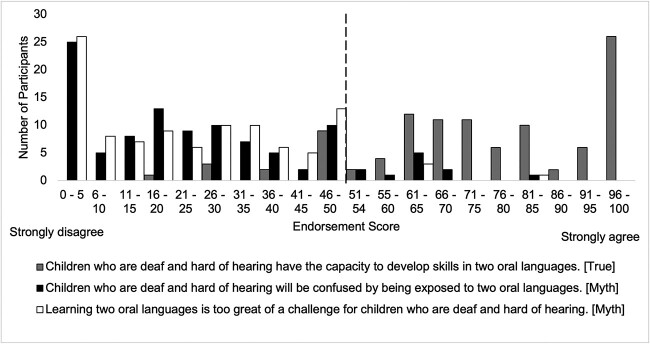

Bilingualism

The survey included one true statement and two myth statements about children who are DHH using two spoken languages. The participants’ responses to questions on this subtopic were areas of relative strength; see Figure 2 and Table 1. The scaling across all histograms (Figures 2–4) is the same to aid comparison across statements.

Figure 2.

Histogram of endorsement scores for statements about bilingualism. An endorsement score of 0 aligns with the “strongly disagree” anchor on the left, and a score of 100 aligns with the “strongly agree” anchor on the right. The vertical dashed line identifies the midpoint (i.e., 50).

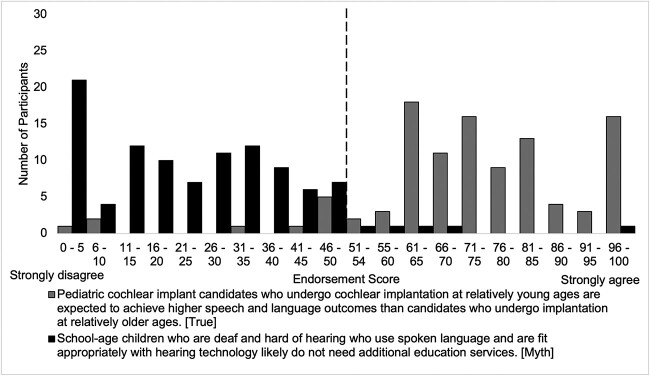

Figure 4.

Histogram of endorsement scores for statements about audiovisual integration. An endorsement score of 0 aligns with the “strongly disagree” anchor on the left, and a score of 100 aligns with the “strongly agree” anchor on the right. The vertical dashed line identifies the midpoint (i.e., 50).

Children who are DHH have the capacity to develop skills in two oral languages [true]. With a mean endorsement score of 75 (SD = 20; range: 19–100), the participants endorsed this true statement with a large effect size (d = 1.28). Most (87%) of the participants agreed with the statement albeit to varying degrees, as can be seen by the relatively flat distribution between 61 and 95. Twenty-six participants marked at or very close to “strongly disagree.” Nine participants marked the midpoint (i.e., 50), and six participants selected a response between the midpoint and “strongly disagree” (i.e., score of 19–49). In contrast to the other true DHH statements, no participants marked between 0 and 15. Thus, the minimum value of 19 is relatively high for the study.

Children who are DHH will be confused by being exposed to two oral languages [myth]. The participants exhibited a nearly mirror image distribution for this myth statement relative to the prior statement. This inverse relation between these two statements is expected because the statements were designed to counter one another. With a mean endorsement score of 25 (SD = 20; range: 0–81), the participants rejected this myth with a large effect size (d = 1.25). Analogous to the prior statement, most participants (81%) rejected this myth, again to varying degrees. The distribution is relatively flat for the left half of the histogram (i.e., disagree section). Nine participants marked the midpoint (i.e., 50). Eleven participants (10%) agreed with the statement. Nonetheless, none of the participants marked the maximum value (i.e., 100) for “strongly agree.” Instead, the maximum value marked by any participant was 81, which is consistent with the minimum value of 19 for the prior true statement (i.e., children who are DHH have the capacity to develop skills in two oral languages).

Learning two oral languages is too great of a challenge for children who are DHH [myth]. Participants responded very similarly to this myth as to the prior bilingual myth. With a mean endorsement score of 24 (SD = 19; range: 0–83), they rejected this myth with a large effect size (d = 1.38). Only four participants agreed to some degree with the statement. Similar to the other myth about bilingualism, but unlike myths on other subtopics, the maximum value marked for any participant was less than 100 (i.e., 83). Twelve participants marked the midpoint (i.e., 50).

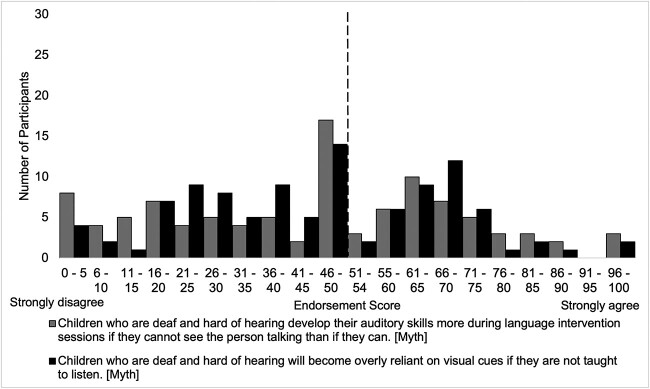

Hearing technology

The survey included one true statement and one myth statement about the effects of hearing technology and the educational needs of children who are DHH. See Figure 3 and Table 1.

Figure 3.

Histogram of endorsement scores for statements about hearing technology. An endorsement score of 0 aligns with the “strongly disagree” anchor on the left, and a score of 100 aligns with the “strongly agree” anchor on the right. The vertical dashed line identifies the midpoint (i.e., 50).

Pediatric CI candidates who undergo cochlear implantation at relatively young ages are expected to achieve higher speech and language outcomes than candidates who undergo implantation at relatively older ages [true]. With a mean endorsement score of 73 (SD = 19; range: 0–100), the participants strongly endorsed this true statement with a large effect size (d = 1.22). Responses spanned the full range of possible scores. Sixteen participants marked at or very close to “strongly agree,” and most (65%) other scores fell between 60 and 85. This pattern shows moderate agreement with the statement. Although participants selected the full range of scores, only six participants (6%) disagreed with the statement to some degree (i.e., score < 50). Four participants marked the midpoint (i.e., 50).

School-age children who are DHH who use spoken language and are fit appropriately with hearing technology likely do not need additional education services [myth]. With a mean endorsement score of 24 (SD = 18; range: 0–100), the participants overall rejected this myth statement with a large effect size (d = 1.39). Nonetheless, the range of scores still spanned from 0 to 100, and the distribution is relatively flat across the “disagree” portion of the histogram (i.e., left half). There is a small elevation at the far left of the histogram. Twenty-one participants marked at or very close to the “strongly disagree” endpoint. Five participants agreed with the statement (i.e., score > 50), and six participants marked the midpoint (i.e., 50).

Audiovisual integration

Participants exhibited an area of relative weakness in their knowledge of audiovisual integration and its implications for language intervention for children who are DHH. The participants failed to reject either myth on this subtopic. See Figure 4 and Table 1.

Children who are DHH develop their auditory skills more during language intervention sessions if they cannot see the person talking than if they can [myth]. With a mean endorsement score of 45 (SD = 26; range: 0–100), the participants failed to reject this myth statement. The effect size was small (d = 0.18). A peak at the midpoint is apparent on the histogram with 15 participants marking the midpoint (i.e., 50). The distribution is relatively flat on the disagree (i.e., left) side with 46 participants and slightly sloping downward on the agree (i.e., right) side with 42 participants. This pattern indicates an equivocal perspective for the participant group.

Children who are DHH will become overly reliant on visual cues if they are not taught to listen [myth]. With a mean endorsement score of 46 (SD = 22; range: 0–100), the participants also failed to reject this myth statement. The effect size was small (d = 0.19). The pattern of response was quite similar to the prior myth statement about audiovisual integration. There is a peak at the midpoint with 13 participants marking the midpoint (i.e., 50). The distribution slopes on either side with 51 participants on the disagree side and 41 on the agree side. As noted previously, this pattern indicates an overall equivocal perspective for the participant group.

Correlations between endorsement scores and SLP experience

To explore differences in knowledge across SLPs, we tested whether years of experience being an SLP correlates with the degree to which SLPs’ responses align with current evidence. See Table 1. The correlations between years of experience as an SLP and endorsement scores were significant for the three statements about bilingualism. The correlation was small to moderate and negative (r = −.23) for the true statement that “Children who are deaf and hard of hearing have the capacity to develop skills in two oral languages.” Correlations were positive for the myth statements, “Children who are deaf and hard of hearing will be confused by being exposed to two oral languages,” (r = .29; small to moderate) and “Learning two oral languages is too great of a challenge for children who are deaf and hard of hearing” (r = .45; moderate to large). These three correlations show that SLPs with more experience tended to be less aligned with the current evidence. In contrast, SLPs with less experience tended to be more aligned with the current evidence. Correlations for the statements related to hearing technology and audiovisual integration were not significant.

Discussion

This study was designed to evaluate (a) the extent to which SLPs endorse or reject statements related to children who are DHH and learning to use spoken language and (b) the correlations between knowledge about such statements and SLP experience. Overall, participants exhibited mean moderate agreement with true statements and mean moderate disagreement with myth statements. There were more participants who provided extreme responses in the correct direction for the statements about bilingualism than other subtopics. The pattern of responses indicates a relative strength in bilingual knowledge for the participants as a group. Nonetheless, the ample individual variation should be recognized. Responses ranged the full span (i.e., 0–100) for the hearing technology and audiovisual integration statements and approximately 80% of the range for the bilingualism statements. Variation in responses across statements for the various subtopics supports the need to view professional development related to children who are DHH as multifaceted rather than unitary. Professional development providers need to consider the myriad issues that potentially hinder application of evidence-based practices as well as the multiple means through which SLPs may uptake and apply knowledge about current best practices.

Bilingualism

Participants presented with a similar pattern of responses for the three statements about bilingualism. The histograms for the two true statements mirror that of the one myth statement, which is expected because we would expect participants to move the slider in opposite directions for the true versus myth statements, regardless of whether their responses align with the current evidence. This pattern of findings increases our confidence in the validity of participants’ responses. About a quarter of participants tended to indicate strong agreement with the true statements, and most of the remaining participants agreed to varying degrees. Likewise, about a quarter of the participants indicated strong disagreement with the myth statement, and most of the remaining participants disagreed to varying degrees. We also found that the participants were more likely to agree more strongly with the true statements and disagree more strongly with the myth statements if they had fewer years of SLP experience. This finding is encouraging for the future of the discipline in aligning with current evidence on bilingualism. At the same time, it supports the need for professional development for practicing SLPs rather than increasing efforts to support enhanced knowledge of bilingualism in graduate training.

SLPs, especially those who have been practicing for longer, may benefit from education on the benefits of supporting two spoken languages for children who are DHH. However, SLPs’ recognition that children who are DHH are capable of learning more than one spoken language will not alone suffice. SLPs additionally need to know how to best support bilingual or even multilingual language development. Several studies support the provision of services in both or all spoken languages that a child is learning. For example, Bunta et al. (2016) compared the language skills of Spanish-English speaking children who are DHH who received dual language instruction versus those who received English-only instruction. The participants (n = 20) in this retrospective study spoke Spanish and English and used hearing aids and CIs. The mean performance for the group who received dual language instruction was higher in English than the mean performance for the group who received English-only instruction on the composite and expressive communication scores, as measured by the Preschool Language Scale—Fourth Edition (Zimmerman et al., 2002). McDaniel et al. (2019) also found no evidence of bilingual instruction inhibiting English word learning performance for Spanish-English speaking preschool children who are DHH. Further, two of the three children in this single-case research design study showed evidence of greater efficiency for conceptual vocabulary (i.e., number of words learned regardless of language) when taught in both Spanish and English than in only English.

Hearing technology

In comparison to the bilingual statements, fewer participants indicated strong agreement for the true statement and strong disagreement with the myth about hearing technology. Instead, participants tended to indicate more moderate agreement or disagreement for the statements. This pattern suggests less confidence or conviction in response to questions about hearing technology as compared to bilingualism.

Most participants correctly agreed that earlier implantation is helpful for children who use CIs, but to varying degrees. A notable portion marked closer to the midpoint than “strongly agree.” Similarly, most participants correctly disagreed with the statement that children who are DHH and fit appropriately with hearing technology likely do not need additional education services. However, the distribution is relatively flat rather than responses clearly clustered toward the “strongly disagree” endpoint. About one-fifth of the participants marked at or very close to the “strongly disagree” endpoint. Recognizing the role of hearing technology, including limitations, is important for SLPs interpreting a child’s language growth and collaborating with audiologists for potential changes in devices or fitting. SLPs may interact with a child who is DHH much more frequently than the child’s audiologist does. Consequentially, the SLP has an important responsibility in referring the child as needed for audiological services. The SLP also must alter speech-language intervention services as appropriate for the child to access the curriculum and achieve age-expected language skills. Even with appropriately-fit hearing technology, a child may not be making adequate progress in spoken language skills and therefore needs a change in the intensity and/or type of language intervention. Additionally, approximately 40% of children who are DHH have additional diagnoses (Fortnum et al., 2002; Gallaudet Research Institute, 2008; Roberts & Hindley, 1999; Van Naarden et al., 1999). These needs must be recognized and addressed. Nonetheless, children who are DHH with and without additional diagnoses are likely to display language skills below those of their peers with typical hearing and need additional education supports (Antia et al., 2020; Nittrouer et al., 2020; Tomblin et al., 2015).

Audiovisual integration

For both myth statements related to audiovisual integration, participants showed greater clustering of responses toward the midpoint rather than the endpoints for “strongly agree” or “strongly disagree.” This pattern, along with mean endorsement scores of 45 and 46, suggests SLPs are uncertain about how audiovisual integration relates to or influences the language, and more broadly communication, development of children who are DHH. As a group, participants exhibited limited knowledge of the benefits of multisensory input for word recognition for individuals who are DHH (Bergeson et al., 2005; Grant & Seitz, 1998; Kaiser et al., 2003; Kirk et al., 2002, 2007; Lachs et al., 2001) and factors that influence audiovisual integration (e.g., age of implantation, language skills, and speech intelligibility; Bergeson et al., 2003; Gilley et al., 2010; Kirk et al., 2002; Schorr et al., 2005). SLPs need to recognize the benefits of multisensory input to maximize those benefits and provide complementary intervention.

In recent years, there has been movement away from using the hand cue, but other related strategies continue to be recommended in an apparent attempt to limit children’s potential or perceived reliance on visual cues (e.g., speech hoops, strategic sitting, and visual distractors; Estabrooks, 2001; Rhoades et al., 2016; Robbins, 2016). In one of the few direct tests of this suggested over-reliance on visual cues, preschoolers who are DHH were taught novel words under two conditions: (a) audiovisual condition with access to visual speechreading cues (i.e., could see the interventionist’s face) and (b) auditory-only condition in which the interventionist covered her mouth with a speech hoop to block access to visual speechreading cues (McDaniel et al., 2018). None of the participants in this single-case research design study exhibited slower word learning in the audiovisual condition compared with the auditory-only condition. Considering the current evidence, SLPs should be cautious in limiting access to visual cues and instead consider how to maximize the benefits of multisensory input (McDaniel & Camarata, 2017).

Limitations and future directions

A few limitations should be acknowledged. First, we did not collect data on the participants’ experience with children who are DHH or any other specific population of children. We cannot differentiate responses from participants who often or primarily serve children who are DHH versus those with little-to-no experience serving children who are DHH. Future studies of this nature should systematically collect data on the participants’ experience with children who are DHH. Relatedly, future investigations should compare speech-language pathology students’ perspectives with those of practicing SLPs to examine the influence of graduate education on perspectives and knowledge about myths. In our labs, such analyses are underway and can inform future studies that assess students’ perspectives on various myths when they begin versus when they complete their graduate training.

Second, the current study focuses on myths related to children who are DHH and learning to use spoken language. Additional myths relate to children who are DHH and learning to use sign language. Such myths warrant investigation in future studies.

Third, participants responded only via the visual analogue scale. Open-ended response opportunities were not provided. Future survey studies that include open-ended response options may further illuminate SLPs’ reasoning for their responses. Additional studies, including mixed-methods studies, should be considered to guide evidence-based attempts to increase alignment between SLPs’ knowledge and current evidence.

Fourth, replication with a national sample would inform whether the sample in this study, primarily from Tennessee, is representative of SLPs more broadly. Although no known practices would result in Tennessee SLPs’ knowledge varying from those in other states, empirical evidence is justified.

Other future directions include addressing identified weaknesses of SLPs’ knowledge related to the evaluated myths and equipping SLPs to combat myth-related misconceptions. Addressing weaknesses of SLPs’ knowledge is important, especially for identified areas of weakness (e.g., audiovisual integration). Such efforts should address susceptibility to misinformation broadly as well as information specific to certain myths. Equipping SLPs to combat myth-related misconceptions is important, especially for identified areas of strength (e.g., bilingualism) in which SLPs can be leaders for improving access to effective, evidence-based services for children who are DHH. SLPs often have opportunities to interact with caregivers and other professionals from multiple disciplines. Taking advantage of these opportunities and SLPs’ expertise has the potential to improve outcomes for children who are DHH.

Conclusion

The findings support continuing to identify specific gaps in SLPs’ knowledge to then provide targeted professional development to fill those gaps and provide high-quality services to children who are DHH and learning to use spoken language. Of particular note, SLPs with less experience were more likely to reject myths and to endorse true statements about children who are DHH learning two spoken languages than SLPs with more experience. This finding provides evidence for addressing myths about bilingualism through professional development rather than changes to preservice training. Nonetheless, there may be other topics that would be addressed best at the preservice training level. For audiovisual integration of children who are DHH, the participants as a group showed weak knowledge. Therefore, training through multiple avenues and levels may be required to show SLPs how to integrate evidence of multisensory processing for speech perception into clinical practice. Continued investigation is warranted to clarify gaps in SLPs’ knowledge and test interventions aimed to improve their knowledge of spoken language learning of children who are DHH and application of that knowledge to service provision for improved child outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants for participating to make this study possible. We also thank Hannah Malamud Hoffman and Annabelle Clarke for assisting with data collection for this study.

Footnotes

In this study, we are referring specifically to visual input from the speaker’s articulators rather than also including visual input from sign language and gestures. Nonetheless, visual input from sign language and gestures is valuable and warrants continued study.

Contributor Information

Jena McDaniel, Department of Hearing and Speech Sciences, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, United States.

Hannah Krimm, Department of Communication Sciences and Special Education, University of Georgia, Athens, United States.

C Melanie Schuele, Department of Hearing and Speech Sciences, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, United States.

Funding

This work was supported by a Vanderbilt University Medical Center CTSA Program Award (5UL1TR002243-03), the NCATS/NIH (UL1TR000445), and a US Department of Education training grant (H325D140087). The manuscript contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Conflicts of Interest statement. None declared.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) . (2022). 2021 Member and affiliate profile. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. https://www.asha.org/siteassets/surveys/2021-member-affiliate-profile.pdf.

- Antia, S., Lederberg, A., Easterbrooks, S., Schick, B., Branum-Martin, L., Connor, C., & Webb, M. (2020). Language and reading progress of young deaf and hard-of-hearing children. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 25(3), 334–350. 10.1093/deafed/enz050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benítez-Barrera, C., Reiss, L., Majid, M., Chau, T., Wilson, J., Figueroa Rico, E., Bunta, F., Raphael, R. M., & de Diego-Lázaro, B. (2023). Caregiver experiences with oral bilingualism in children who are deaf and hard of hearing in the United States: Impact on child language proficiency. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 54(1), 224–240. 10.1044/2022_LSHSS-22-00095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeson, T., Pisoni, D. B., & Davis, R. A. (2003). A longitudinal study of audiovisual speech perception by children with hearing loss who have cochlear implants. The Volta Review, 103, 347–370. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeson, T. R., Pisoni, D. B., & Davis, R. A. O. (2005). Development of audiovisual comprehension skills in prelingually deaf children with cochlear implants. Ear and Hearing, 26(2), 149–164. 10.1097/00003446-200504000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird, E. K. R., Cleave, P., Trudeau, N., Thordardottir, E., Sutton, A., & Thorpe, A. (2005). The language abilities of bilingual children with Down syndrome. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 14(3), 187–199. 10.1044/1058-0360(2005/019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaiser, K. M., & Mahshie, J. (2022). Comfort levels of providers serving children who are deaf/hard of hearing: Discrepancies and opportunities. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 7(5), 1432–1448. 10.1044/2022_PERSP-22-00030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc, C., Castilla-Earls, A., Bunta, F., & Fulcher-Rood, K. (2022). Bilingual parents’ experiences receiving advice regarding language use: A qualitative perspective. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 7(6), 2039–2050. 10.1044/2022_PERSP-22-00086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boons, T., De Raeve, L., Langereis, M., Peeraer, L., Wouters, J., & Van Wieringen, A. (2013). Expressive vocabulary, morphology, syntax and narrative skills in profoundly deaf children after early cochlear implantation. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34(6), 2008–2022. 10.1016/j.ridd.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs, M., & Closs, J. S. (1999). A descriptive study of the use of visual analogue scales and verbal rating scales for the assessment of postoperative pain in orthopedic patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 18(6), 438–446. 10.1016/S0885-3924(99)00092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunta, F., & Douglas, M. (2013). The effects of dual-language support on the language skills of bilingual children with hearing loss who use listening devices relative to their monolingual peers. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 44(3), 281–290. 10.1044/0161-1461(2013/12-0073). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunta, F., Douglas, M., Dickson, H., Cantu, A., Wickesberg, J., & Gifford, R. H. (2016). Dual language versus English-only support for bilingual children with hearing loss who use cochlear implants and hearing aids. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 51(4), 460–472. 10.1111/1460-6984.12223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrom, B., Elash, C. A., Eremenco, S., Bodart, S., Muehlhausen, W., Platko, J. V., & Howry, C. (2022). Measurement comparability of electronic and paper administration of visual analogue scales: A review of published studies. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science, 56, 394–404. 10.1007/s43441-022-00376-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2010). Identifying infants with hearing loss – United States, 1999-2007. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 59(8), 220–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd Ed.). New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Colletti, L., Mandalà, M., Zoccante, L., Shannon, R. V., & Colletti, V. (2011). Infants versus older children fitted with cochlear implants: Performance over 10 years. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 75(4), 504–509. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettman, S. J., Pinder, D., Briggs, R. J., Dowell, R. C., & Leigh, J. R. (2007). Communication development in children who receive the cochlear implant younger than 12 months: Risks versus benefits. Ear and Hearing, 28(2), 11S–18S. 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31803153f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettman, S., Wall, E., Constantinescu, G., & Dowell, R. (2013). Communication outcomes for groups of children using cochlear implants enrolled in auditory–verbal, aural–oral, and bilingual–bicultural early intervention programs. Otology & Neurotology, 34(3), 451–459. 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3182839650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillman, D. A., Smyth, J. D., & Christian, L. M. (2009). Internet, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method (3rd Ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Dodd, B. (1979). Lip reading in infants: Attention to speech presented in-and out-of-synchrony. Cognitive Psychology, 11(4), 478–484. 10.1016/0010-0285(79)90021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, L. S. (1985). Perceptual capabilities with the cochlear implant: Implications for aural rehabilitation. Ear and Hearing, 6(3), 60S–69S. 10.1097/00003446-198505001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erber, N. P. (1969). Interaction of audition and vision in the recognition of oral speech stimuli. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 12(2), 423–425. 10.1044/jshr.1202.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erber, N. P. (1972). Auditory, visual, and auditory-visual recognition of consonants by children with normal and impaired hearing. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 15(2), 413–422. 10.1044/jshr.1502.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estabrooks, W. (Ed.) (2001). 50 frequently asked questions about auditory-verbal therapy. Toronto, Ontario: Learning to Listen Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Feltmate, K., & Kay-Raining Bird, E. (2008). Language learning in four bilingual children with down syndrome: A detailed analysis of vocabulary and morphosyntax. Canadian Journal of Speech–Language Pathology and Audiology, 32(1), 6–20. [Google Scholar]

- Fortnum, H. M., Marshall, D. H., & Summerfield, A. Q. (2002). Epidemiology of the UK population of hearing-impaired children, including characteristics of those with and without cochlear implants–audiology, aetiology, comorbidity and affluence. International Journal of Audiology, 41(3), 170–179. 10.3109/14992020209077181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis, G., & Jakicic, V. (2022). Equivalent statistics for a one-sample t-test. Behavior Research, 55, 77–84. 10.3758/s13428-021-01775-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallaudet Research Institute (2008). Regional and national summary report of data from the 2008 annual survey of deaf and hard of hearing children and youth. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University. [Google Scholar]

- Geers, A., Mitchell, C., Warner-Czyz, A., Wang, N., Eisenberg, L., & CdaCI Investigative Team (2017). Early sign language exposure and cochlear implantation benefits. Pediatrics, 140(1), e20163489. 10.1542/peds.2016-3489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geers, A. E., Nicholas, J. G., & Sedey, A. L. (2003). Language skills of children with early cochlear implantation. Ear and Hearing, 24(1), 46S–58S. 10.1097/01.AUD.0000051689.57380.1B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geers, A., & Sedey, A. (2011). Language and verbal reasoning skills in adolescents with 10 or more years of cochlear implant experience. Ear and Hearing, 32(Suppl. 1), 39S–48S. 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181fa41dc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilley, P. M., Sharma, A., Mitchell, T. V., & Dorman, M. F. (2010). The influence of a sensitive period for auditory-visual integration in children with cochlear implants. Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience, 28(2), 207–218. 10.3233/RNN-2010-0525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant, K. W., & Seitz, P. F. (1998). Measures of auditory-visual integration in nonsense syllables and sentences. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 104(4), 2438–2450. 10.1121/1.423751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiberson, M. (2013a). Bilingual myth-busters series language confusion in bilingual children. Perspectives on Communication Disorders and Sciences in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Populations, 20(1), 5–14. 10.1044/cds20.1.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guiberson, M. (2013b). Survey of Spanish parents of children who are deaf or hard of hearing: Decision-making factors associated with communication modality and bilingualism. American Journal of Audiology, 22(1), 105–119. 10.1044/1059-0889(2012/12-0042). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Minor, B. L., Elliott, V., Fernandez, M., O’Neal, L., McLeod, L., Delacqua, G., Delacqua, F., Kirby, J., Duda, S. N., & REDCap Consortium (2019). The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 95, 103208. 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Thielke, R., Payne, J., Gonzalez, N., & Conde, J. G. (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, M., & Terlektsi, E. (2011). Reading and spelling abilities of deaf adolescents with cochlear implants and hearing aids. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 16(1), 24–34. 10.1093/deafed/enq031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, M., Page, T. A., Oleson, J., Spratford, M., Unflat Berry, L., Peterson, B., Welhaven, A., Arenas, R. M., & Moeller, M. P. (2016). Factors affecting early services for children who are hard of hearing. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 47(1), 16–30. 10.1044/2015_LSHSS-14-0078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson, D., & Arnetz, B. B. (2005). Validation and findings comparing VAS vs. Likert scales for psychosocial measurements. International Electronic Journal of Health Education, 8, 178–192. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, R. F., Kirk, K. I., & Hay-McCutcheon, M. (2011). Assessing multimodal spoken word-in-sentence recognition in children with normal hearing and children with cochlear implants. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 54(2), 632–657. 10.1044/1092-4388(2010/09-0148). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, A. R., Kirk, K. I., Lachs, L., & Pisoni, D. B. (2003). Talker and lexical effects on audiovisual word recognition by adults with cochlear implants. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 46(3), 390–404. 10.1044/1092-4388(2003/032). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay-Raining Bird, E., Cleave, P., Trudeau, N., Thordardottir, E., Sutton, A., & Thorpe, A. (2005). The language abilities of bilingual children with Down syndrome. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 14(3), 187–199. 10.1044/1058-0360(2005/019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay-Raining Bird, E., Lamond, E., & Holden, J. (2012). Survey of bilingualism in autism spectrum disorders. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 47(1), 52–64. 10.1111/j.1460-6984.2011.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J., & Davis, C. (2003). Hearing foreign voices: Does knowing what is said affect visual-masked-speech detection? Perception, 32(1), 111–120. 10.1068/p3466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, K. I., Hay-McCutcheon, M. J., Holt, R. F., Gao, S., Qi, R., & Gehrlein, B. L. (2007). Audiovisual spoken word recognition by children with cochlear implants. Audiological Medicine, 5(4), 250–261. 10.1080/16513860701673892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, K. I., Pisoni, D. B., & Lachs, L. (2002). Audiovisual integration of speech by children and adults with cochlear implants. In J. L. H. Hansen & B. Pellom (Eds.), International Conference on Spoken Language Processing 2002 (pp. 1689–1692). Sydney, Australia: Causal Productions PTY, Ltd. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krimm, H., McDaniel, J., & Schuele, C. M. (2023). Conceptions and misconceptions: What do school SLPs think about dyslexia? Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. Advanced online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyle, F., & Harris, M. (2011). Longitudinal patterns of emerging literacy in beginning deaf and hearing readers. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 16(3), 289–304. 10.1093/deafed/enq069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachs, L., Pisoni, D. B., & Kirk, K. I. (2001). Use of audiovisual information in speech perception by prelingually deaf children with cochlear implants: A first report. Ear and Hearing, 22(3), 236–251. 10.1097/00003446-200106000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund, E. (2016). Vocabulary knowledge of children with cochlear implants: A meta-analysis. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 21(2), 107–121. 10.1093/deafed/env060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, C. (1978). Sensitivity and accuracy of the visual analogue scale: A psycho-physical classroom experiment. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 6(1), 15–24. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1978.tb01676.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConkey Robbins, A., Green, J. E., & Waltzman, S. B. (2004). Bilingual oral language proficiency in children with cochlear implants. Archives of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, 130(5), 644–647. 10.1001/archotol.130.5.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreery, R. W., Alexander, J., Brennan, M. A., Hoover, B., Kopun, J., & Stelmachowicz, P. G. (2014). The influence of audibility on speech recognition with nonlinear frequency compression for children and adults with hearing loss. Ear and Hearing, 35(4), 440–447. 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreery, R. W., Walker, E. A., Spratford, M., Lewis, D., & Brennan, M. (2019). Auditory, cognitive, and linguistic factors predict speech recognition in adverse listening conditions for children with hearing loss. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 13, 1093. 10.3389/fnins.2019.01093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreery, R. W., Walker, E. A., Spratford, M., Oleson, J., Bentler, R., Holte, L., & Roush, P. (2015). Speech recognition and parent-ratings from auditory development questionnaires in children who are hard of hearing. Ear and Hearing, 36, 60S–75S. 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel, J., Benitez-Barrera, C., Soares, A., Vargas, A., & Camarata, S. (2019). Bilingual versus monolingual vocabulary instruction for bilingual children with hearing loss. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 24(2), 142–160. 10.1093/deafed/eny042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel, J., & Camarata, S. (2017). Does access to visual input inhibit auditory development for children with cochlear implants? A review of the evidence. Perspectives of ASHA Special Interest Groups, 2(9), 10–24. 10.1044/persp2.SIG9.10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel, J., Camarata, S., & Yoder, P. (2018). Comparing auditory-only and audiovisual conditions for a word learning intervention for children with hearing loss. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 23(4), 382–398. 10.1093/deafed/eny016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel, J., Krimm, H., & Schuele, C. M. (2023). Speech-language pathologists’ endorsement of speech, language, and literacy myths reveals persistent research-practice gap. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 54(2), 550–568. 10.1044/2022_LSHSS-22-00087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myles, P. S., Troedel, S., Boquest, M., & Reeves, M. (1999). The pain visual analog scale: Is it linear or nonlinear? Anesthesia and Analgesia, 89(6), 1517–1520. 10.1097/00000539-199912000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas, J. G., & Geers, A. E. (2013). Spoken language benefits of extending cochlear implant candidacy below 12 months of age. Otology & Neurotology, 34(3), 532–538. 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318281e215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, K. J., Sherman, M., Divi, S. N., Bowles, D. R., & Vaccaro, A. R. (2022). The role of family-wise error rate in determining statistical significance. Clinical Spine Surgery, 35(5), 222–223. 10.1097/BSD.0000000000001287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nittrouer, S., Lowenstein, J., & Antonelli, J. (2020). Parental language input to children with hearing loss: Does it matter in the end? Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 63(1), 234–258. 10.1044/2019_JSLHR-19-00123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi, J. K., Mirenda, P., Marinova-Todd, S., Hambly, C., Fombonne, E., Szatmari, P., Bryson, S., Roberts, W., Smith, I., & Vaillancourt, T. (2012). Comparing early language development in monolingual-and bilingual-exposed young children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(2), 890–897. 10.1016/j.rasd.2011.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis, J., Crago, M., Genesee, F., & Rice, M. (2003). French-English bilingual children with SLI: How do they compare with their monolingual peers? Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 46(1), 113–127. 10.1044/1092-4388(2003/009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, M. L., & Werker, J. F. (2003). Two-month-old infants match phonetic information in lips and voice. Developmental Science, 6(2), 191–196. 10.1111/1467-7687.00271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perozzi, J. A., & Sanchez, M. L. C. (1992). The effect of instruction in L1 on receptive acquisition of L2 for bilingual children with language delay. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 23(4), 348–352. 10.1044/0161-1461.2304.348. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, J. M., Marinova-Todd, S. H., & Mirenda, P. (2012). Brief report: An exploratory study of lexical skills in bilingual children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(7), 1499–1503. 10.1007/s10803-011-1366-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfennings, L., Cohen, L., & van der Ploeg, H. (1995). Preconditions for sensitivity in measuring change: Visual analogue scales compared to rating scales in a Likert format. Psychological Reports, 77(2), 475–480. 10.2466/pr0.1995.77.2.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack, D. (1970). Educational audiology for the limited hearing child. Charles C: Thomas. [Google Scholar]

- Reisberg, D., McLean, J., & Goldfield, A. (1987). Easy to hear but hard to understand: A lip-reading advantage with intact auditory stimuli. In B. Dodd & R. Campbell (Eds.), Hearing by eye the psychology of lip-reading (pp. 97–113). Hills Dale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades, E. A., Estabrooks, W., Lim, S. R., & MacIver-Lux, K. (2016). Strategies for listening, talking, and thinking in auditory-verbal therapy. In W. Estabrooks, K. MacIver & E. A. Rhoades (Eds.), Auditory-verbal therapy for young children with hearing loss and their families, and the practitioners who guide them (pp. 285–326). San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Rickards, G., Magee, C., & Artino, A. R. Jr. (2012). You can’t fix by analysis what you’ve spoiled by design: Developing survey instruments and collecting validity evidence. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 4(4), 407–410. 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00239.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, A. M. (2016). Auditory-verbal therapy: A conversational competence approach. In M. P. Moeller, D. J. Ertmer & C. Stoel-Gammon (Eds.), Promoting language and literacy in children who are deaf or hard of hearing (pp. 181–212). Baltimore, MD: Brooks Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, C., & Hindley, P. (1999). Practitioner review: The assessment and treatment of deaf children with psychiatric disorders. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 40(2), 151–167. 10.1111/1469-7610.00430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouger, J., Fraysse, B., Deguine, O., & Barone, P. (2008). McGurk effects in cochlear-implanted deaf subjects. Brain Research, 1188, 87–99. 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruben, R. (2018). Language development in the pediatric cochlear implant patient. Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology, 3(3), 209–213. 10.1002/lio2.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudner, M., Mishra, S., Stenfelt, S., Lunner, T., & Rönnberg, J. (2016). Seeing the talker’s face improves free recall of speech for young adults with normal hearing but not older adults with hearing loss. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 59(3), 590–599. 10.1044/2015_JSLHR-H-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schorr, E. A., Fox, N. A., van Wassenhove, V., & Knudsen, E. I. (2005). Auditory-visual fusion in speech perception in children with cochlear implants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102, 18748–18750. 10.1073/pnas.0508862102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seung, H., Siddiqi, S., & Elder, J. H. (2006). Intervention outcomes of a bilingual child with autism. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology, 14(1), 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, A., Bain, L., Li, Y., Delgado, G., & Ruperto, V. (2003). Decisions Hispanic families make after the identification of deafness. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 8(3), 291–314. 10.1093/deafed/eng016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, G. M., & Artino, A. R. Jr. (2017). How to create a bad survey instrument. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 9(4), 411–415. 10.4300/JGME-D-17-00375.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumby, W. H., & Pollack, I. (1954). Visual contribution to speech intelligibility in noise. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 26, 212–215. 10.1121/1.1907309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Svirsky, M. A., Robbins, A. M., Kirk, K. I., Pisoni, D. B., & Miyamoto, R. T. (2000). Language development in profoundly deaf children with cochlear implants. Psychological Science, 11(2), 153–158. 10.1111/1467-9280.00231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thordardottir, E. T., Ellis Weismer, S., & Smith, M. E. (1997). Vocabulary learning in bilingual and monolingual clinical intervention. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 13(3), 215–227. 10.1177/026565909701300301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomblin, J. B., Barker, B. A., Spencer, L. J., Zhang, X., & Gantz, B. J. (2005). The effect of age at cochlear implant initial stimulation on expressive language growth in infants and toddlers. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing, 48(4), 853–867. 10.1044/1092-4388(2005/059). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomblin, J. B., Harrison, M., Ambrose, S. E., Walker, E. A., Oleson, J. J., & Moeller, M. P. (2015). Language outcomes in young children with mild to severe hearing loss. Ear and Hearing, 36(0 1), 76S–91S. 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourangeau, R., Rips, L. J., & Rasinski, K. A. (2000). The psychology of survey response. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van Naarden, K., Decouflé, P., & Caldwell, K. (1999). Prevalence and characteristics of children with serious hearing impairment in metropolitan Atlanta, 1991-1993. Pediatrics, 103, 570–575. 10.1542/peds.103.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vohr, B. (2003). Overview: Infants and children with hearing loss—Part I. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 9(2), 62–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, E. A., Holte, L., McCreery, R. W., Spratford, M., Page, T., & Moeller, M. P. (2015). The influence of hearing aid use on outcomes of children with mild hearing loss. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 58(5), 1611–1625. 10.1044/2015_JSLHR-H-15-0043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltzman, S. B., McConkey Robbins, A., Green, J. E., & Cohen, N. L. (2003). Second oral language capabilities in children with cochlear implants. Otology & Neurotology, 24(5), 757–763. 10.1097/00129492-200309000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]