Abstract

Introduction:

Dissociative identity disorder (DID) is a treatable mental health condition that is associated with a range of psychobiological manifestations. However, historical controversy, modern day misunderstanding, and lack of professional education have prevented accurate treatment information from reaching most clinicians and patients. These obstacles also have slowed empirical efforts to improve treatment outcomes for people with DID. Emerging neurobiological findings in DID provide essential information that can be used to improve treatment outcomes.

Areas covered:

In this narrative review, the authors discuss symptom characteristics of DID, including dissociative self-states. Current treatment approaches are described, focusing on empirically supported psychotherapeutic interventions for DID and pharmacological agents targeting dissociative symptoms in other conditions. Neurobiological correlates of DID are reviewed, including recent research aimed at identifying a neural signature of DID.

Expert opinion:

Now is the time to move beyond historical controversy and focus on improving DID treatment availability and efficacy. Neurobiological findings could optimize treatment by reducing shame, aiding assessment, providing novel interventional brain targets and guiding novel pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic interventions. The inclusion of those with lived experience in the design, planning and interpretation of research investigations is another powerful way to improve health outcomes for those with DID.

Keywords: Dissociative identity disorder (DID), dissociation, lived experience, neurobiology, neuroimaging, psychotherapy, pharmacology, treatment outcomes

1. Introduction

Dissociative identity disorder (DID) is a treatable mental health condition affecting approximately 1% of adults in the general population [1–4]. A foundational body of theoretical and clinical work, and a small but growing body of empirical research supports the effectiveness of a phase-oriented psychotherapeutic approach for the treatment of DID [5–9]. Psychotropic medications are typically used adjunctively to manage commonly co-occurring symptoms [10–12], though there is limited support for a psychopharmacologic approach targeting dissociative symptoms specifically [13].

Regrettably, historical controversy, modern day misunderstanding, and lack of professional education have prevented accurate treatment information from reaching most clinicians and patients [9,14]. These obstacles also have slowed empirical efforts to improve treatment approaches and outcomes for people with DID. Fortunately, with recent advances expanding our knowledge about the neurobiology of DID [15–17], the field is poised to leverage a more sophisticated biological understanding of this condition to optimize treatment.

Our objective in this narrative review is to provide a cutting-edge overview of DID treatment and to identify novel paths forward for optimizing treatment leveraging neurobiology. To accomplish this, we first define DID and its central dissociative symptoms, explicate how this condition, like other mental health conditions, can be explained by a diathesis-stress model, and briefly address historical controversy about DID. Next, we overview the current state of DID treatment, including a phase-oriented psychotherapeutic approach and adjunctive psychotropic medications for dissociative symptoms that target the opioid, serotonergic, and glutamatergic systems. Next, we overview the systems-level neurobiology of DID. We end with an expert opinion section in which we propose the novel integration of our neurobiological understanding of DID, and the inclusion of the lived-experience voice will propel the next wave of DID treatment research forward.

2. Dissociative Identity Disorder Defined

DID is a psychobiological syndrome. With an onset during early childhood, DID occurs in the context of maltreatment perpetrated most often by caregivers [2,9,18], and it is delineated by the subjective experience of identity alteration [1]. Typically, children gradually develop a felt sense of self that is coherent and stable across time, different emotional experiences, and contexts [14,19]. However, it is theorized that for children with an innate capacity to dissociate at a level significant enough to generate DID, the timing and nature of maltreatment influences identity formation in characteristic ways [14]. As a result, individuals with DID experience behavioral and emotional states that feel jarring [20], discrete, and partially or wholly unconnected to other states [14]. These subjectively separate, compartmentalized mental states are termed “dissociative self-states” (see also personality states, identity states, alters, parts) [17]. In this section, we provide an overview of self-states in all people and then discuss unique qualities of dissociative self-states. Next, we describe additional dissociative symptoms occurring in DID, as well as a proposed diathesis stress model for DID. Finally, we cover reasons for the historical controversy and modern-day misunderstanding surrounding DID.

2.1. Self-states

In all people, self-states are particular “ways of being you” [21,p.66]. Your subjective experience in a particular self-state might include your bodily experience, your perception of what you look like, characteristics or abilities you have, and how you feel about yourself in a certain context [14,17]. For example, in a specific self-state you might feel yourself breathing rapidly with a sense of tension in your body. You have the perception that you look sturdy in your body as it is poised to hit a tennis ball. You are aware of your ability to be a strong, competitive tennis player. You feel a sense of proficiency and pride. In this way, a self-state includes perceptions, actions, and internal states (e.g., affect) [17,22].

Moreover, self-states are a dynamic network of brain activity involved in perception, action, and internal state experience [22]. The brain activity associated with a particular self-state develops over time and is stored in memory. Consequently, it can change over time with new experiences [17]. Everyone experiences self-states, and everyone lies on a continuum of having collections of more integrated versus dissociative self-states [17].

In DID, a dissociative self-state is also a dynamic collection of perceptions, actions and internal states based on past experiences stored in memory (just like a non-dissociative self-state). However, what makes a dissociative self-state in DID unique is this: A shift in sense of agency and ownership occurs such that you feel as if one self-state becomes an observer, while another self-state takes control of the “wheel” and drives on (R. Oxnam, personal communication, February 2016). Furthermore, dissociative self-states subjectively feel separate – as if they do not belong to you (“not me”), and often as if they belong to someone else who lives inside the mind [23,24]. Importantly, individuals with DID logically understand these experiences must be their own despite feeling separate and “not me.” While they often suffer from self-puzzlement, their ability to reality test is intact and they exhibit a high capacity for reflective thinking about self and others [25]. Dissociative identity alteration is not akin to psychosis [26–30].

Dissociative self-states often are dominated by a specific collection of memories, affect, and behaviors ([31]; see also the related concept of “modes” in [32,33]). An individual with DID may also associate a mental image or bodily experience with a particular dissociative self-state [23,34–36]. Imagine, for example, you are a woman with a history of chronic childhood sexual abuse at the hands of a family member. In a dissociative self-state, you might feel like a frightened young girl – with a feeling that your body is small like a child’s body (despite being an adult woman), and that you are in danger. In another dissociative self-state, you might feel numb, perceive yourself to look like an adult woman (as you are biologically), but your body feels unreal: “That little girl is not me! Those feelings can’t be mine” [17]. These dissociative self-states are often experienced as “intruding” into awareness in an automatic and startling way [20]. This can contribute to the subjective experience in DID of lacking a cohesive feeling of self and identity [20].

A mind made up of highly compartmentalized, discrete dissociative self-states helps to preserve a child’s cognitive and emotional capacities (e.g., humor, empathy, hope, joy), and to preserve relational bonds with caretakers despite experiences of maltreatment and profound attachment dilemmas [37–41]. It is a powerful, internal coping mechanism when the “outside world” offers no other support or help. At the same time, in adulthood, this identity alteration can interfere with occupational, relationship, and day-to-day functioning. In this way, DID represents a paradoxical condition: it is both a successful survival strategy in the context of childhood maltreatment as well as a cause of significant distress and impairment in other contexts [14,19,36,42].

2.2. Additional Dissociative Symptoms

People with DID also experience amnesia, or gaps in their memory, for important personal information, aspects of traumatic experiences, and day-to-day events [1,43]. This experience of amnesia typically is state dependent [44–46]. For example, while experiencing one dissociative self-state, a person may hold awareness of thoughts, emotions, and memories of severe abuse, whereas when experiencing another dissociative self-state, they feel subjectively that they have diminished or even no awareness of those same experiences. The degree of amnesia and discrete separation between dissociative self-states can be highly variable and may be related to the emotional tolerability of information connected to those states [5].

In addition to disruptions in identity and experiences of amnesia, individuals with DID also experience other forms of pathological dissociation and identity confusion [47]. They frequently experience depersonalization, a subjective sense of detachment from their sense of self, mind and body [1]. For example, they may feel as if they are floating above their own body or as if they only exist from the neck up. They also frequently experience derealization, a sense of disconnection from their surroundings [1]. For example, they may feel as if they are in a dream or a movie. These experiences can occur both within and outside of stressful moments.

This constellation of symptoms and the resulting discontinuity of experience in DID often results in a deep sense of “puzzlement” or confusion about oneself and one’s situation (“why am I like this? What is wrong with me?”) [20,48,49]. Tragically, not only is there puzzlement about oneself, but people with DID also experience profound levels of shame related to their maltreatment and often intense feelings of being unworthy of love and belonging [21,50].

2.3. Diathesis Stress Model of DID

A diathesis-stress model of DID predicts this condition occurs only in individuals who possess an underlying predisposition or vulnerability toward DID (diathesis) and simultaneously experience specific stressful circumstances (stress). Here we briefly overview the hypothesized diatheses and the necessary environmental stressors to produce DID.

2.3.1. Diathesis

The diathesis in DID is theorized to involve an innate capacity for dissociation and/or hypnosis [51–54]. Hypnotic states (also known as trance states) involve a particular type of attention in which the person can maintain highly focused, receptive concentration coupled with reduced peripheral awareness [55]. Hypnotic states also include trance logic [56]. Trance logic is the juxtaposition of mutually incompatible elements of experience without anxiety [55]. Prior work suggests that adults with DID have an extremely high capacity to enter hypnotic states – and do so on their own without guidance (i.e., enter “autohypnotic” trance states) [40,51,57,58].

As with any psychiatric condition [59], the underlying predisposition toward DID, that is the capacity for dissociation and/or hypnosis, is likely genetically mediated. There are currently no DID-specific molecular genetic studies; however, recent research points to some possible links between dissociative symptoms in PTSD and genes related to learning and memory function [60,61].

2.3.2. Stress

As discussed earlier, the “stress” that serves as the catalyst for the development of DID involves intolerable, physically inescapable early childhood maltreatment often at the hands of caregivers [51–54]. A large body of systematic empirical research has found individuals with DID consistently report severe histories of childhood neglect and abuse [2].

2.3.3. Diathesis-Stress

Taken together, it is theorized that, as young children subjected to maltreatment, individuals with DID automatically used their genetic and brain-based ability for autohypnosis to compartmentalize overwhelming and conflicting thoughts, feelings, sensations, memories, and body images. By way of trance logical interpretations of depersonalization experience (out of body experiences), they then personified these conflicting thoughts, feelings etc. onto perceived other aspects of self, resulting in psychological distancing among self-states and the pseudo-delusion of separateness (i.e., “not me” aspects of self) [23]. Individuals who experienced the same maltreatment, but who lack the capacity for dissociation and/or autohypnosis, would not develop dissociative self-states to cope with their maltreatment.

2.4. Historical Controversy and Modern-Day Misunderstanding

A wealth of evidence supports the validity of DID as a diagnosis and the significance of childhood trauma and maltreatment in the development of DID [2,18,62]. However, DID remains a highly stigmatized and underdiagnosed condition due to historical controversy and modern-day misunderstanding [9,14,63]. Historically, misunderstanding about DID is rooted in an unwillingness to acknowledge the prevalence and impact of child abuse, and in particular an unwillingness to acknowledge its impact on women and girls [64–66]. In this vein, “fantasy models” (see also, “sociocognitive models”) of DID propose that symptoms of dissociation, fantasy proneness, and suggestibility lead to false or exaggerated reports of child abuse and DID (e.g., [67]). Moreover, these models of DID propose that the condition is iatrogenic – created and reinforced by psychotherapists, media influences, and general sociocultural expectations regarding the symptoms and causes of DID (e.g., [68]).

There is no empirically derived evidence to support these claims of the fantasy model [18]. In contrast, empirical evidence from neurobiological studies, experimental investigations, and epidemiological surveys strongly supports the validity of DID diagnosis and the importance of maltreatment to its development [2,18,62]. Studies that have sought independent corroboration of childhood maltreatment have found compelling evidence in most cases [3]. Unfortunately, fantasy models pervade modern cultural understanding of DID, media portrayals, psychology textbooks, and clinical training [5]. Historical controversies echo into the present and have resulted in concrete harms and prolonged suffering for people with DID: underdiagnosis, years-long delays in accessing care, stigmatizing responses from some clinicians, treatment barriers, and a stunted body of research into empirically based treatments [64,65,69]. Moving forward, it is critical for the field to continue combating this misinformation with empirical studies of DID and its treatment.

3. Current Treatment Approaches to DID

Despite barriers to timely diagnosis and treatment access, expert consensus guidelines and a small but growing body of empirical work delineate effective psychotherapeutic treatment practices. With respect to medication treatments, there are no randomized, placebo controlled clinical trials specifically targeting dissociative symptoms in DID. However, there are studies evaluating efficacy of psychotropics for depersonalization and derealization symptoms in individuals with other psychiatric conditions. First, we cover expert consensus guidelines regarding the psychotherapeutic approaches to DID and empirical studies on DID treatment, and then we overview studies evaluating medications to target dissociation-specific symptoms in non-DID samples.

3.1. Psychotherapy.

A long and robust history of clinical work (e.g., [7,40]), as well as a growing body of empirical examinations of dissociation-specific interventions, provide evidence for the treatability of DID. Expert consensus guidelines recommend long-term relational psychotherapy as the main approach to DID treatment [8]. As DID emerges from childhood maltreatment in the context of early attachment relationships, the individual loses trust in the world and “an Other” [70]. This loss is experienced as part of a profound devaluation of self. It results in a seismic hollowing-out of agency, loneliness, and often abjection [71].

From this perspective, said plainly, relationships with other people are the problem, and simultaneously people are also part of the solution. Symptoms of DID can be ameliorated in the context of a safe enough, but not too safe, long-term therapeutic relationship [72]. The central tenet in a relational approach to trauma treatment is that only in the context of a trusting relationship is there enough safety to chance re-engagement in human relationships.

With the trusted therapeutic relationship as the setting, the overarching goal of DID treatment is to improve functioning by very gradually – and safely – working to support a person’s ability to experience trauma-related thoughts, emotions, memories, and body image as their own [8]. The strength of the therapeutic relationship and the maintenance of firm boundaries are essential ingredients in successful psychotherapy with individuals diagnosed with DID [5,6,21,23,39]. Working through traumatic transference/countertransference patterns is an integral part of treatment [73,74].

As with other complex trauma-related conditions, treatment of DID occurs in phases [8]. Although the phases are described separately, there often is fluid movement between phases and safety and stabilization are addressed throughout treatment [8]. In Phase 1, often referred to as “safety and stabilization,” the goals are fostering a sense of safety and trust in the therapeutic relationship, developing a shared understanding and language around the individual’s experiences of dissociation, and enhancing emotion regulation skills [5]. This is accomplished by providing psychoeducation about complex PTSD and dissociation and by teaching specific skills to maintain safety, increase tolerance of emotions, manage dissociation with grounding techniques and posttraumatic intrusions with containment techniques.

Brand and colleagues recently have developed a manualized intervention for Phase 1 of DID treatment referred to as Finding Solid Ground [5]. This program consists of workbook-based educational modules and homework assignments that can be implemented in individual or group-based settings [75]. Overall, Phase 1 builds the capacity to tolerate and cope with trauma-related emotions and intrusions, as well as support in differentiating the traumatic past from the present.

Phase 2 involves more direct confrontation, working through, and processing of trauma-related memories. However, dissociative symptoms can interfere with effective trauma processing (e.g., [76]). Specifically, dissociation can impede the emotional learning that is necessary to extinguish fear and shame around these experiences by disrupting immersion and attention to the traumatic memories. As such, patients must first decrease reliance on dissociation in Phase 1 to prepare for Phase 2 [8].

Trauma processing in Phase 2 of DID treatment emphasizes gradually discussing past and current trauma-related events and feelings while consistently keeping within a patient’s window of tolerance for affect. Phase 2 can also involve short-term manualized interventions for PTSD such as cognitive processing therapy or eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy, though these can be challenging to implement with fidelity in the treatment of DID [5]. For example, the efficacy of some manualized treatments is diminished when dissociation is the primary, reflexive manner of coping [76–82], as is the case in DID. Additionally, suicidality and self-harm behaviors occur at high rates in DID [83] and adhering to the strict pacing of manualized interventions is not always feasible in these cases [5]. However, specific techniques associated with manualized treatments can be useful when integrated into a collaborative, long-term relational framework (e.g., gradual building of proficiency through thoughtful in vivo exercises).

Phase 2 can also leverage an individual’s innate capacity for hypnotic experience by teaching patients to use self-hypnosis. This can provide not only a boost to a sense of self-efficacy and increased capacity for affect regulation, but also can be used therapeutically to significant effect [8,84–87]. For example, hypnosis can be used for increasing a sense of safety, developing inner resources, as well as helping to regulate abrupt or jarring switches between dissociative self-states that are often provoked by overwhelming affect. Overall, Phase 2 builds feelings of agency and ownership over trauma-related thoughts, feelings, memories, and actions.

Finally, Phase 3 is focused on reconnection. Specifically, this phase centers around supporting the individual in reconnecting with themselves and developing new connections with others, if they wish [5]. Some may consider that trauma work is complete once trauma memories are processed and no longer intrusive. However, such work results in a new way of being in the world. This new way of being – in which individuals with DID may no longer experience “not me” senses of self but rather believe and understand that “it was me, after all, all along” – requires time for acclimation and proficiency in new methods for healthy, effective coping [5,6,40,88]. Overall, Phase 3 builds capacity to navigate the world and relationships with less reliance on dissociation [8].

3.1.1. Empirical Research on Psychotherapeutic Interventions for Dissociation and DID.

A small, but growing, body of empirical evidence indicates that the phased psychotherapeutic treatment model is effective for people with DID [25,89–93]. Next, we highlight key results from this body of empirical treatment research. First, we highlight results from a series of studies conducted over the past decade collectively referred to as the “Treatment of Patients with Dissociative Disorders (TOP DD)” studies. These studies included individuals with DID and other specified dissociative disorders type 1 (OSDD; like DID but not meeting full criteria) [1] and have covered a range of designs, including naturalistic treatment-as-usual observations, systematic implementation of a Phase 1 intervention. We end this section with a discussion of two randomized control trials of Phase 1 interventions for DID/OSDD.

TOP DD naturalistic studies observed treatment-as-usual standard of care for DID/OSDD with no additional interventions from the research team [25,91]. This international endeavor collected data from 280 patients and 292 therapists over the course of 2.5 years. Brand and colleagues found that when comparing patients first cross-sectionally, individuals in earlier phases of treatment had more PTSD and dissociative symptoms, self-harm behaviors and psychiatric hospitalizations compared to individuals in later phases of treatment [25]. Moreover, compared to baseline assessments, follow-up assessments at 2.5 years indicated patients had significant decreases in PTSD, dissociative symptoms, other psychiatric symptoms, and suicidal behaviors, as well as improved global functioning [91]. These follow-up assessments also indicated decreased treatment costs over time [94]. A subset of participants completed a long-term, 6-year follow-up assessment revealing further improvements in daily functioning, fewer psychiatric hospitalizations and sexual revictimizations for individuals who remained in treatment [92]. This series of studies suggests that the standard of care phased treatment for DID with trained clinicians is effective, though a randomized control trial will be needed to establish causality.

To improve access to treatment and address gaps in professional education, Brand and colleagues recently developed a standardized Phase 1 adjunctive intervention specifically for individuals with DID, OSDD or significant trauma-related dissociation (e.g., dissociative subtype of PTSD; TOP DD Network Study) [93]. This intervention consists of self-paced psychoeducational videos and written exercises available to both patients and therapists. Topics covered include psychoeducation about PTSD and complex PTSD, maintaining safety, and how dissociation can interfere with healthy emotion regulation. The content of this intervention was iteratively refined based on feedback from people with lived experience of DID [93]. Longitudinal assessments demonstrated robust reductions in symptoms of depression, PTSD and dissociation, non-suicidal self-injury, and improvements in emotion regulation and adaptive capacities [93]. Individuals farther along in treatment trended towards fewer hospitalizations and suicide attempts. Participants who reported the highest levels of dissociation at baseline were those who benefitted most significantly from this online psychoeducational intervention. This finding suggests this Phase 1 intervention may best serve those in greatest need.

Of note, participants were not excluded from this Phase 1 online intervention based on co-occurring conditions, presence of self-harm or suicidality, recent hospitalization, or ongoing traumatization [93]. Historically, individuals with DID have been almost universally excluded from treatment studies based on their high rates of co-occurring psychiatric conditions, medication usage, and/or difficulties with safety. Given this, this series of studies represents a radical step forward in its inclusivity [5,95].

Currently, there are two randomized control trials (RCTs) of treatment for DID and OSDD, one completed [96] and one ongoing [97]. Both RCTs focus on Phase 1 “safety and stabilization” manualized interventions. The first RCT studied psychoeducational group therapy based on an abbreviated version of the Coping with Trauma-Related Dissociation manual [98]. In a randomized delayed-treatment design, the group treatment participants completed 20 of the 43 modules in this manual over 20 weeks (while continuing individual treatment as usual), and the control group continued individual treatment as usual alone [96]. Both groups demonstrated significant improvements in psychosocial functioning though did not differ from each other in outcomes during this time period. The group treatment participants also did not demonstrate improvements in PTSD or dissociative symptoms during this period. However, the group treatment participants demonstrated significantly greater improvements in psychosocial functioning at a six-month follow-up assessment, which may indicate better outcomes following this treatment in the longer-term [96].

A second RCT on Phase 1 stabilization treatment is currently underway focusing on the Finding Solid Ground program [5,97]. Participants are being randomized to complete the Finding Solid Ground intervention or a waitlist control. As described above, the Finding Solid Ground program consists of workbook-based educational modules and homework assignments, and in this RCT the program is implemented in individual therapy over the course of a maximum of one year. Preliminary results indicate that the patients who participated in the Finding Solid Ground program showed greater reductions in dissociation compared to the waitlist controls [97]. This suggests Phase 1 treatment does successfully impact core features of DID/OSDD, though may require a longer time period (e.g., 1 year) to impact these symptoms.

The growing body of empirical work on DID treatment indicates a phased approach is effective, and individuals with DID can benefit from online adjunctive Phase 1 treatment. However, this research also demonstrates that despite years of treatment, impairments can remain for some individuals with DID. For example, at the 6-year follow-up assessments in the TOP DD naturalistic studies, a significant minority of patients still reported substantial relationship, employment, and health difficulties [92]. Relatedly, although the expert consensus phase-based model of DID treatment has been the standard treatment for decades, some argue that a more immediate trauma memory exposure-based processing would be beneficial, without an initial phase 1 stabilization treatment [99,100]. Empirically based treatments developed originally for other conditions have been put forth as possible treatments for DID with more immediate trauma memory exposure (e.g., [99,101]), although concerns have been expressed about further destabilizing these patients, who often struggle with suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury [102,103]. An RCT comparing a phased approach vs. more immediate trauma memory processing is needed to empirically determine the superiority of one approach over the other. These points taken together suggest there are many gaps in the empirical literature on DID treatment and clearly opportunities to further optimize treatment moving forward.

3.2. Psychopharmacology

To date, there are no randomized, placebo controlled clinical trials of medications to treat DID; however, individuals with DID often are prescribed medications to treat the complex pattern of co-occurring, non-dissociative psychiatric symptoms that often accompany DID [10,104]. For example, in addition to experiencing symptoms of co-occurring PTSD, people with DID frequently experience depression, anxiety, disordered eating, problematic substance use, suicidal ideation, and self-injury [2]. Pharmacologic treatments for these symptoms are beyond the scope of this review. For reference, we refer the reader to several resources [10–12].

Our focus here is on a small body of work examining pharmacological treatments specifically targeting pathological dissociative symptoms. It is important to note there are no medications to treat the symptoms of identity alteration in DID. There are, however, medications targeting other dissociative experiences like depersonalization. These medications have been empirically studied in people with depersonalization-derealization disorder, borderline personality disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder and PTSD. While individuals with DID might also benefit from these medications, this remains to be systematically evaluated.

In this section, we briefly overview three neuromodulatory and neurotransmitter systems that may play a role in generating dissociative experiences (see [105–107] for reviews, and [108] for recent discussion). We then end each section with medication studies that demonstrate successful reductions in dissociative symptoms likely by targeting these neuromodulatory/neurotransmitter systems. Of note, studies here used various measures of pathological dissociation – often with a total score that did not differentiate between specific types of dissociation (e.g., depersonalization, derealization, amnesia, numbing etc.). Given this, we use the terminology of “dissociative symptoms” in this section in a general sense.

3.2.1. Opioid System.

Growing evidence obtained across diagnoses suggests the opioid system may be important for experiences of dissociation. This neuromodulatory system modifies the impact of neurotransmitters [109]. Opioid peptides bind to opioid receptors that are expressed widely throughout the brain (e.g., mu, kappa, delta, nociception, zeta receptors) – with higher concentrations in the cortex, limbic regions and brain stem [110]. The opioid system participates in nociception, analgesia, stress responding, respiration, and gastrointestinal, endocrine and immune function [111]. A kappa-opioid receptor agonist, enadoline, increased feelings of depersonalization in a small sample of individuals with histories of substance abuse [112]. Salvia divinorum also is a kappa-opioid receptor agonist [113] linked to depersonalization experiences [114]. These two studies suggest the kappa-opioid receptor in particular may be a promising target for regulating dissociative experiences [105].

Medication studies focused on drugs that block the effect of opioids have shown some promise in reducing dissociative symptoms. One single blind placebo-controlled trial found the opiate antagonist, naloxone, reduced depersonalization symptoms in depersonalization disorder [115]. Longitudinal and case series studies of naltrexone and nalmefene in depersonalization disorder, borderline personality disorder, and PTSD also support opioid antagonist administration for reduced dissociative symptoms [116–119]. It may be that individuals with DID also experience reduced dissociative symptoms with administration of naloxone, naltrexone, or nalmefene though this approach has yet to be systematically studied.

While the results in particular of the Nuller and colleagues [115] randomized controlled trial are promising, other recent studies are conflicting. For example, neither naloxone nor naltrexone performed better than placebo for dissociative symptoms in randomized controlled trials in borderline personality disorder samples [120,121]. Moreover, recent double-blind crossover work demonstrated naloxone did not block the dissociative experiences linked to administration of the dissociogenic drug ketamine [122].

It is difficult to know what implications these findings have for the effectiveness of opioid antagonists in DID. It could be that the neurotransmitter cascades associated with dissociative experiences in borderline personality disorder or those associated with ketamine may be different than those involved with pathological dissociation in DID. Moreover, dosage, time course and design characteristics were significantly different across all studies, making it difficult to draw strong conclusions about the conditions in which opioid antagonists perform better than placebo for reducing dissociative experiences transdiagnostically.

3.2.2. Serotonergic system

Some evidence suggests the serotonergic system may be important in the generation of dissociative symptoms. Serotonin binds to metabotropic G-protein-coupled 5-HT receptors and ionotropic 5-HT3 receptors expressed widely across the entire brain [123]. The serotonergic system is involved with affect, cognition, autonomic, appetitive, and motoric functioning, and perhaps more broadly in regulating arousal and behavioral activity [124]. Experimental partial agonism at serotonin 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors induced a broad array of dissociative symptoms in individuals with social phobia, borderline personality disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder [125]. More recently, a pre-post, positron emission tomography study in an individual with dissociative amnesia showed that, as compared to pre-recovery levels, inhibitory HT1A receptor density was increased at frontal and temporal regions after recovery [126]. Given these findings, the serotonergic system may be a possible target for regulating dissociative experiences.

Medication studies focused on agents promoting serotonergic signaling have had mixed results regarding their impact on dissociative symptoms. One RCT demonstrated effective reduction of dissociative symptoms in PTSD using a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), paroxetine [127]. However, another randomized controlled trial showed that the SSRI fluoxetine did not perform better than placebo in reducing dissociative symptoms in depersonalization disorder [128]. Paroxetine may also be effective for reducing certain types of dissociative symptoms in DID, though this has yet to be evaluated empirically.

3.2.3. Glutamatergic system

Modest evidence suggests the glutamatergic system may be involved in dissociative experiences. This neurotransmitter acts through ionotropic AMPA, NMDA, kainite receptors and metabotropic glutamate receptors [129]. Glutamate functions as an “on” switch throughout the central nervous system, acting as the primary excitatory signaling system involved in learning, memory, and synaptic plasticity [129]. As discussed briefly above, ketamine is a dissociogenic drug [130,131] that acts on NMDA and opioid receptors [132], thus pointing toward a role for glutamate in dissociative experiences. Moreover, glutamate levels in the anterior cingulate cortex positively correlated with dissociative symptoms in a borderline personality disorder sample [133]. These findings suggest the glutamatergic system may be a promising target for pharmacological regulation of dissociative experiences.

Medications acting to block glutamatergic signaling may be effective at reducing dissociative symptoms. However, research is presently limited, and findings are conflicting. For example, lamotrigine is an anticonvulsant that reduces the release of glutamate, and some evidence suggests administration of lamotrigine can reduce experimentally induced dissociative symptoms [134,135]. However, lamotrigine did not perform better than placebo to reduce dissociative symptoms in a RCT for depersonalization derealization disorder [136]. Of note, a trial of lamotrigine for dissociative symptoms which reported positive results was recently retracted [137]. Given the limited studies testing medications that inhibit glutamatergic signaling and its relationship to dissociative symptoms, it is difficult to say how lamotrigine or other glutamate antagonists would impact dissociation in DID. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy is a noninvasive method of measuring certain metabolites and neurotransmitters in the brain, including a proxy of glutamate [138,139]. Prior work suggests that neurometabolites measured using magnetic resonance spectroscopy were associated with variability in neurocognitive disorders, such as PTSD [140,141]. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies in DID could provide further understanding of glutamate’s role in dissociative experiences [108].

Only two medications have performed better than placebo for treatment of dissociative symptoms in RCTs: the opioid antagonist naloxone and the SSRI paroxetine. Pharmacological intervention studies for pathological dissociation symptoms in DID have not yet been conducted. Basic neuroscience studies of the neurotransmitter and neuromodulatory systems involved in distinct types of dissociative experiences would help elucidate future pharmacological targets for these experiences, and nascent attempts at this are underway [131,142].

3.3. Summary

In summary, expert consensus guidelines and a small but growing body of empirical research supports a long-term phase oriented psychotherapeutic approach to treat DID. A novel, online, dissociation-specific Phase 1 intervention (and ongoing RCT) represents an exciting step forward in the broad dissemination and accessibility of DID treatment – especially given a mental healthcare landscape in which few treaters are familiar or experienced with treating DID. Moreover, while there are currently no pharmacological interventions specifically for DID, there are two types of medications showing promise for reducing dissociation in other conditions (e.g., opioid antagonists; paroxetine). It may be that these medications could impact dissociative experience in DID, though this remains to be empirically tested. There is an urgent need in the field for medication trials specific to DID given improper psychopharmacological treatment can have a disastrous impact in any psychiatric condition. A thorough understanding of the neurobiology of dissociation and DID is the key to propelling the next wave of both novel psychotherapeutic and psychopharmacological interventions for DID.

4. Neurobiology of pathological dissociation and DID

To improve treatment leveraging neurobiology, we must first understand neurobiological mechanisms in DID. Here, we overview the systems-level neurobiology of pathological dissociation and DID to inform our discussion of treatment optimization.

While our knowledge of the neurobiological mechanisms in DID is limited, seminal work over the past two decades has begun to map out robust brain correlates of pathological dissociative symptoms. Much of our understanding draws from studies on the dissociative subtype of PTSD [105,143]. This landmark work led to inclusion of this subtype in the DSM-5 and built a foundation for understanding the more severe forms of trauma-related, pathological dissociative symptoms in DID [65]. First, we briefly describe the neurobiology of pathological depersonalization and derealization in the dissociative subtype of PTSD (for reviews see: [105,144]). Second, we cover recent neurobiological findings specific to DID (for recent reviews see [17,106]).

4.1. Neurobiology of Trauma-related Depersonalization and Derealization.

Under typical circumstances, cortical structures like the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) and limbic regions like the amygdala and periaqueductal grey have a balanced relationship and can influence the activity of the other flexibly based on need and context [145,146]. The amygdala helps to alert our attention to relevant or salient information in the environment so we can act adaptively (e.g., reacting quickly to a threat like a car swerving into your lane). The vmPFC facilitates emotion and arousal regulation by exerting “top down” control over limbic structures (e.g., managing feelings of frustration when on the phone with a customer service agent).

Evidence shows, however, that the balance of activity between the prefrontal cortex and limbic structures is disrupted for those who experience pathological dissociation. Specifically, depersonalization and derealization are related to an excess of cortical (e.g., vmPFC) inhibition exerted on limbic structures (e.g., amygdala) [105]. For example, prior work indicates that individuals with the dissociative subtype of PTSD have greater activity in regions associated with “top-down” regulation (e.g., prefrontal cortex) and diminished activity in limbic regions (e.g., amygdala) when presented with emotionally provocative autobiographical trauma-related scripts [147,148]. Similarly, greater activity in prefrontal cortex was associated with subjective feelings of dissociation (e.g., depersonalization/derealization) across various emotionally provocative tasks [147–149]. Thus, depersonalization/derealization can be thought of in some contexts as the overmodulation of emotion/arousal or an excess of corticolimbic inhibition. Said plainly, the “brakes” on emotion/arousal are on “too tightly” in the brain.

In addition to excessive corticolimbic inhibition, pathological dissociation has also been linked to brain patterns associated with passive (as opposed to active) responses to threat. A small region in the brainstem, the periaqueductal grey, contributes to non-conscious emotion perception and reflexive behaviors aimed at helping to escape threatening situations [145,150]. Escape or defensive behaviors can be active and linked with hyperarousal (e.g., fight-or-flight) or they can be passive and associated with hypoarousal (e.g., unresponsive immobility, collapse, stillness). Dorsal and lateral regions of the periaqueductal grey are associated with sympathetic nervous system activation and active defense behaviors, while ventrolateral regions have been linked with parasympathetic activation and passive defense behaviors [151].

At rest, individuals who experienced prominent depersonalization and derealization (i.e., PTSD dissociative subtype) demonstrated increased functional connectivity between ventrolateral periaqueductal grey and cortical areas involved in threat detection compared to classic PTSD (minimal or no depersonalization/derealization) [152]. The PTSD dissociative subtype group also had increased functional connectivity between ventrolateral periaqueductal grey and areas linked to depersonalization experiences (e.g., temporal parietal junction, operculum). Thus, evidence suggests depersonalization/derealization is also facilitated by a rapid, unconscious, “bottom-up” threat detection that is wired toward passive defensive behaviors.

4.2. Neurobiology of DID

Similar to studies on the dissociative subtype of PTSD, research focused specifically on DID demonstrates a pattern of excess corticolimbic inhibition. Using the same paradigm as described above, individuals with DID were presented with autobiographical trauma-related scripts [153]. They listened to these scripts while experiencing two different dissociative self-states: one that felt numb, detached and as if trauma-related memories happened to “someone else” and one that felt hyperaroused as if trauma-related memories happened to them personally. When experiencing the dissociative self-state that felt numb, individuals with DID demonstrated greater activity in medial prefrontal cortex regions and less activity in limbic regions (e.g., amygdala, insula) [153]. Importantly, this evidence of corticolimbic inhibition firmly places DID along a continuum of posttraumatic adaptations with other trauma-related disorders like PTSD [65,154].

Recent machine learning research has begun to point toward patterns in brain structure and function that are specific to DID and distinguishable at the individual as opposed to group-level. Reinders and colleagues utilized a machine learning approach to predict whether someone had a diagnosis of DID (vs. no psychiatric diagnosis) based on measures of brain structure [155]. The supervised machine learning model was able to discriminate between diagnosis groups with relatively high accuracy (72% sensitivity, 74% specificity) [155]. Regions that predicted an individual’s membership in the DID group were widely distributed across the brain. Specifically, participants with DID had decreased grey and white matter volume across broad swaths of the prefrontal cortex (e.g., cingulate cortex and precentral gyrus), inferior parietal lobule, temporal lobe regions (e.g., fusiform gyrus), and occipital cortex. Further, participants with DID had greater grey matter volume in regions that have emerged as highly relevant for dissociation-related processes (e.g., periaqueductal grey, precuneus).

Additionally, our group used machine learning to link pathological dissociation symptoms in DID with hyperconnectivity (heighted communication) between brain networks involved in self-generated thought and executive functioning (i.e., default and central executive/frontoparietal control network [156]. There is evidence to suggest that these networks synchronize to facilitate internally oriented, goal-directed cognition, that is, problem solving to accomplish one’s goals [156]. Our results suggest that various brain regions in the central executive and default mode networks are more likely to be active at the same time the more severe the pathological dissociative symptoms. Though speculative, this may imply a dominance of internally oriented, goal-directed cognition in individuals with elevated levels of dissociation. Given histories of interpersonal childhood abuse, individuals may have learned early on to rely on internal problem solving because caregivers were unreliable. In adulthood, however, this childhood adaptation represents a maladaptive integration and regulation of self-relevant internal mental processes.

In summary, pathological dissociative symptoms have been linked with excessive inhibition of limbic structures (e.g., amygdala) by cortical regions (e.g., vmPFC) and greater bottom-up activity from regions such as the periaqueductal grey [152]. Studies of DID neurobiology, specifically, have identified several brain structures that may distinguish DID from control participants [155]. Furthermore, these brain structures overlap with neural networks whose functional connectivity has been implicated in pathological dissociation, a marker of DID [156]. The machine learning studies in DID require replication; however, they provide a first step proof-of-concept toward brain-based diagnostic and symptom identification specific to DID.

Further elucidation of the neurobiological underpinnings of pathological dissociative symptoms and DID are essential to the optimization of treatment approaches. We believe the neurobiology of these experiences can be leveraged clinically to help reduce shame patients feel about these experiences, aid diagnosis, evaluate the efficacy of currently available treatments, monitor recovery, and develop novel interventions. Accordingly, we unpack all these possibilities in our expert opinion section.

5. Conclusion

A strong body of evidence supports the validity of the DID diagnosis, its powerful relationship to chronic, early childhood maltreatment, and the effectiveness of phased, psychotherapeutic treatment. Currently, psychopharmacologic treatment in DID focuses on management of symptoms associated with commonly co-occurring conditions. However, a small body of research in other conditions suggests opiate antagonists and serotonergic medications may warrant study in DID samples. The goal for both psychotherapeutic and pharmacological treatment interventions is to gradually help individuals with DID gain a felt sense of agency and ownership over their internal experience and physical body. Neurobiological studies are beginning to map out robust brain correlates of DID symptoms. Given society’s growing acceptance of the reality of childhood trauma and its psychiatric sequalae, the time to leverage this new neurobiological understanding to optimize clinical treatment for DID is now.

6. Expert Opinion

DID has long been one of the most stigmatized psychiatric disorders in the world. This controversy stems from both an individual and societal reluctance to accept the prevalence and impact of childhood abuse and neglect [65]. Unfortunately, this has stunted empirical research on DID and its treatment. It is a human right to have access to the benefits of research participation, especially research that develops and optimizes treatment [157]. As we emerge from a period concentrated on validating the existence of DID, we can now focus our efforts on optimizing treatment availability and efficacy. This is an exciting time, as the field is primed to make substantial strides in delivering high-quality, evidence-based interventions to help ease the suffering of those living with DID. Here we focus on two essential areas to address in service of optimizing treatment outcomes in DID: 1) neuroscientifically informed treatment; and 2) the inclusion of lived experience voices.

6.1. Leveraging Neurobiology to Optimize DID Treatment

Neurobiological knowledge has already contributed meaningfully to our understanding of trauma-related dissociation and DID and is poised to inform promising new interventions. As with any other mental health condition, there are many ways in which neurobiology could enhance DID treatment, with the aspirational goal of a precision medicine approach. Here, we highlight four areas in which neuroscience could be used to optimize DID treatment: 1) reducing shame; 2) aiding assessment; 3) providing novel interventional brain targets; and 4) guiding novel pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic interventions.

First, psychoeducation around brain patterns in DID may help to de-shame the experience of trauma and DID [5]. For example, clinicians can educate patients about how subcortical areas of the brain can respond rapidly to a potential present-day threat in such a way that one is not able to prevent automatic passive defensive reactions [5]. This can help someone understand why they reacted a certain way despite knowing intellectually they wanted to react differently – for example, experiencing tonic immobility instead of running away or fighting back [5]. Critically, it may also be important to pair such brain-based psychoeducation with complementary discussion that these brain patterns can be changed over time. We emphasize this pairing for the following reason: a growing body of research on neuroscientific explanations for mental conditions demonstrates these explanations are sometimes associated with a perception that people have a reduced capacity to overcome, control, or recover from these symptoms (i.e., a worse prognosis; e.g., [158]). Pairing psychoeducation around brain patterns in DID with discussion that these brain patterns can be changed may help de-shame these experiences while avoiding the unintended negative prognostic perceptions – though this remains to be empirically tested in DID.

Second, neural signatures of pathological dissociation or DID can serve as objective biomarkers, leveraged to help assess for the presence and severity of these experiences. Relying solely on self-report and interview assessments of dissociation and DID means we are dependent on the participant’s awareness, willingness to disclose, and ability to articulate these difficult to express and stigmatized experiences. Objective biomarkers can provide novel ways to assess for the presence of pathological dissociative symptoms, and quantitative, objective ways to track clinically meaningful signals of recovery or relapse across time. For example, to progress to Phase 2 of DID treatment, levels of pathological dissociation must be decreased so that dissociative symptoms do not interfere with learning during trauma-processing [8]. One could measure brain markers of dissociation and their change over time to help identify patients with DID who are ready to progress from Phase 1 (stabilization/emotion regulation treatment) to Phase 2 (trauma-focused exposure interventions). These biomarkers also could be used to stratify patient samples based on pathological dissociation severity for future, gold-standard clinical trials. The machine learning based structural and functional neural “fingerprint” signatures of DID [155,156] are a first step toward precision medicine in this way. However, we have yet to track these signatures longitudinally in treatment. This is the critical next step in research that would inform what changes in the brain as people recover from DID. We then can target activity in these regions to enhance recovery with adjunctive novel neurofeedback, neuromodulatory, psychotherapeutic or psychopharmacological interventions. Ultimately, a neural signature of either DID, its dimensional symptoms or markers of recovery, could be used to predict treatment success. These neural signatures could also aid in optimal treatment selection based on the neural patterns present at baseline.

Third, we can develop novel neurofeedback or neuromodulatory interventions that directly target brain regions involved in dissociation or DID to help alleviate symptoms. For example, interventions targeting the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, amygdala or the bottom-up connectivity of the periaqueductal grey may be beneficial in addressing dissociative experiences. Fortunately, some interventions are beginning to target these very systems. Recent evidence points toward an effective neurofeedback intervention for PTSD that tracks amygdala activity [159]. Participants received real-time feedback about their amygdala activity and learned to down-regulate this activity in 15 training sessions over the course of two months. Compared to participants who did not receive amygdala neurofeedback, participants in the neurofeedback group demonstrated a significantly greater reduction in PTSD symptoms [159]. While this neurofeedback intervention has yet to be evaluated in people with prominent pathological dissociation, it could be fruitful for learning how to down-regulate amygdala activity without using dissociative processes.

Finally, we can develop novel pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic interventions for dissociation and DID that are neuroscientifically guided. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy, a non-invasive method of assessing certain brain chemicals and neurotransmitters, may offer one path toward development of novel pharmacologic interventions for DID [138–140]. For example, using magnetic resonance spectroscopy to characterize levels of glutamate or other metabolites may point toward pharmacologic targets to address core symptoms of DID.

In terms of neuroscientifically guided psychotherapeutic interventions, Deep Brain Reorienting and clinical hypnosis offer two promising examples [160,161]. Deep Brain Reorienting targets tension in the neck and face that occurs when humans orient to potential threats [160]. The orienting response is mediated by activity in the brainstem, including the periaqueductal grey [105,162]. Leveraging this neuroscientific understanding, the Deep Brain Reorienting intervention brings conscious awareness and attention toward this bodily response (i.e., tension in the neck and face) to help someone stay grounded in the face of present-day stressors. A recent RCT suggests this treatment is effective for reducing symptoms of PTSD [162], and theoretically could also be effective for dissociative symptoms – though this has yet to be examined.

Similarly, as discussed, DID is associated with hyperconnectivity in the central executive and default mode networks [156,163]. Clinical hypnosis is a psychotherapeutic intervention associated with reduced connectivity between the central executive and default mode networks in nonpsychiatric control participants [164]. Thus, the judicious application of clinical hypnosis may be valuable in addressing the observed hyperconnectivity of these two networks in DID [161]. Indeed, the scholarly literature on DID treatment points toward clinical hypnosis as an important and effective tool for treating DID, particularly in light of the role that high hypnotizability plays in its etiology (for review, see [53,165]).

Incorporating the neuroscience of DID into treatment through psychoeducation, as objective assessment markers, and with the development of novel neurofeedback, neuromodulatory, or psychotherapeutic interventions will be key for the next wave of DID treatment research. In addition, neurobiological understanding of symptoms and recovery could powerfully improve health outcomes for people with DID. With high rates of suicidal behaviors in DID, we cannot afford to ignore the power of leveraging neurobiological understanding in treatment – millions of human lives are at stake.

6.2. Prioritizing lived experience voices to enhance treatment outcomes

One other powerful way to improve health outcomes is to include those with lived experience in the design, planning, and interpretation of research investigations. The concept of Participatory Action Research is an established framework that accomplishes this goal by including those with lived experience as co-researchers, rather than simply subjects of study [166]. The mental health field is strengthened from the inclusion of participatory action research approaches and the associated centering of the lived experience voice through ensuring research is targeting outcomes aligned with the needs of the community [167–169]. Participatory action research also can help improve the experience of research participation, study retention, and facilitate effective dissemination of results. Moreover, inclusion of people with lived experience in the research process upends traditional hierarchies in scientific study that are embedded within systems, polices, practices and engrained beliefs that perpetuate stigmatization and exclusion [167].

DID research could benefit enormously from routine inclusion of the lived experience voice through a participatory action framework. As part of the TOP DD studies and research conducted at McLean Hospital, we have engaged individuals with DID to serve as advisors to our research programs. For example, individuals with DID provided invaluable feedback on the development and adaptation of the Phase 1 psychoeducational intervention Finding Solid Ground [93]. Their feedback led us to refine the psychoeducational material that was tested in the TOP DD Network study to the current version being tested in the RCT [93]. In addition to patient feedback providing valuable information about the pacing, order, and wording of the materials used in the study, patients who participated in the Network study reported that one of the valuable aspects of participating in the study was contributing to the development of an intervention that would benefit other dissociative individuals [170].

At McLean Hospital, as part of an organization-wide effort to destigmatize psychiatric illness, we engaged a group of individuals with DID to serve as an advisory group starting in 2016. The group recently was formalized as the Lived Experience Advisory Panel (LEAP), providing guidance and feedback on research study development, interpretation of results, and clinical programming development. Members have shared in prior work how participation in LEAP has provided a meaningful sense of community and an important shift in the power dynamic between the traditional roles of patients, researchers, and clinicians [169].

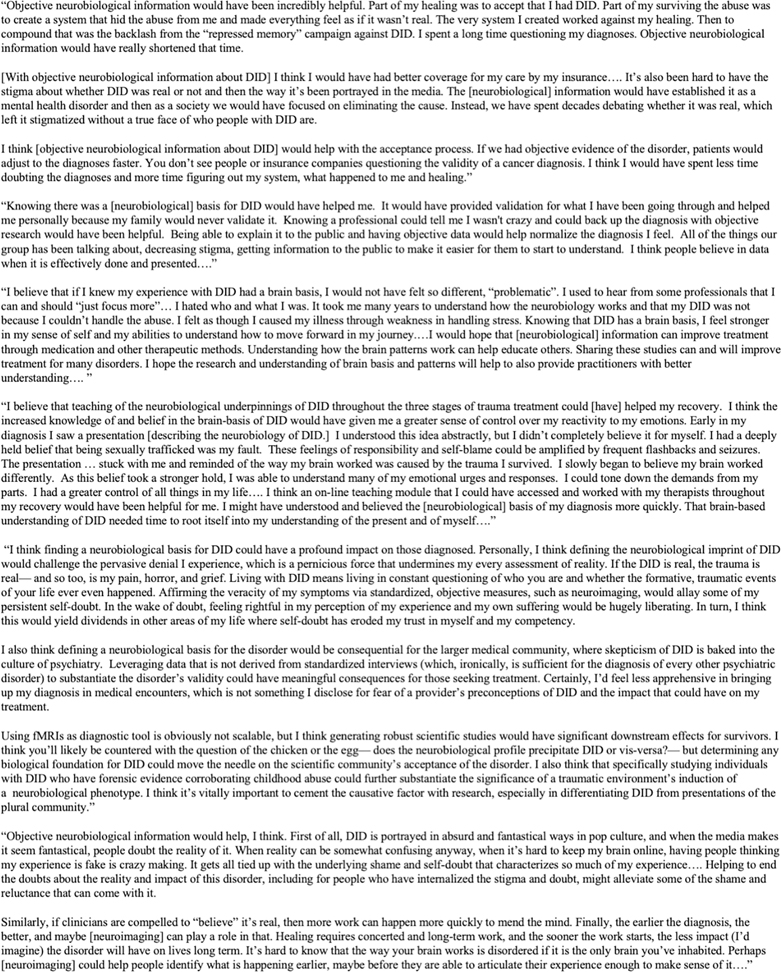

When contemplating the importance of grounding DID treatment in neurobiology, LEAP members stressed the power of a neurobiological understanding of DID to improve the emotional, physical, and mental health of people with DID (Figure 1). Knowing DID has robust neurobiological correlates validated and normalized their experience in a landscape of doubt from family, friends, and health care professionals. This objective knowledge served as a lifebuoy for some to hold onto over the course of treatment – serving to decrease self-blame, stigma and provide a greater sense of control. Continued neurobiological understanding of DID and treatments guided by this understanding would send a powerful, long overdue message counteracting stigma about DID.

Figure 1.

Lived Experience Advisory Panel Quotes on the Importance of Objective, Neurobiological Information about Dissociative Identity Disorder.

6.3. Concluding thoughts and future perspectives

The current state of DID is similar to the state of PTSD in the 1970’s – highly stigmatized, misunderstood, underfunded, and understudied [14,65]. We hope that in five years’ time, research on DID will have identified neurobiological markers of recovery, begin to leverage that knowledge for treatment development and evaluation, and that the inclusion of the lived experience voice will become a standard expectation, not a novelty. With these powerful forces combined, we believe that the ground is fertile for the optimization of treatment and better health outcomes for people with DID. We believe the tide is already turning and encourage clinician scientists to approach funding agencies to support investigation of DID neurobiology and treatment.

Article Highlights.

Dissociative identity disorder (DID) is a trauma-related psychiatric condition with well-characterized symptom profile

A rich literature of case histories, clinical examples, and empirical work affirm that DID is treatable

Medications frequently are used to manage co-occurring symptoms (e.g., posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety), but few agents are supported by research to target dissociative symptoms specifically

Recent advances in the neurobiological understanding of dissociation and DID can inform the development of novel psychotherapeutic and pharmacological interventions

Prioritizing the voices of those with lived experience in the development, implementation, and interpretation of research is essential in optimizing treatment outcomes

Acknowledgments:

The authors acknowledge the insightful contributions from the Lived Experience Advisory Panel (LEAP) members.

Funding:

The authors are funded by the Julia Kasparian Fund for Neuroscience Research and by the National Institute of Mental Health, the United States via grants K01 MH118467 and R01 MH119227.

Abbreviations

- CEN

central executive network

- DID

dissociative identity disorder

- DMN

default mode network

- OSDD

other specified dissociative disorders

- PTSD

post-traumatic stress disorder

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- SSRI

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

- TOP DD

treatment of patients with dissociative disorders

- vmPFC

ventromedial prefrontal cortex

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest:

LAM Lebois has an unpaid membership on the Scientific Committee for the International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation (ISSTD). They also report spousal IP payments from Vanderbilt University for technology licensed to Acadia Pharmaceuticals unrelated to the present work. ML Kaufman reports unpaid membership on the Scientific Committee for the ISSTD. CA Palermo and M Robinson report unpaid membership on the Scientific Committee for the ISSTD. Neither ISSTD nor any funding sources were involved in the analysis or preparation of the paper. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer Disclosures:

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

References

- [1].American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. DSM-5-TR. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Dorahy MJ, Brand BL, Sar V, et al. Dissociative identity disorder: An empirical overview. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2014;48:402–417. **Comprehensive review of DID research highlighting the validity of the diagnosis and its treatability with appropriate psychotherapy

- [3].Foote B Dissociative identity disorder: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, course, assessment, and diagnosis. UpToDate [Internet]. 2022. Mar 1 [cited 2023 Oct 31]; Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/dissociative-identity-disorder-epidemiology-pathogenesis-clinical-manifestations-course-assessment-and-diagnosis.

- [4].Simeon D, Putnam F. Pathological Dissociation in The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): Prevalence, Morbidity, Comorbidity, and Childhood Maltreatment. J Trauma Dissociation. 2022;23:490–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Brand BL, Schielke HJ, Schiavone FL, et al. Finding solid ground: overcoming obstacles in trauma treatment. New York: Oxford University Press; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Chu JA. Rebuilding Shattered Lives: Treating Complex PTSD and Dissociative Disorders, Second Edition. 1st ed. Wiley; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Kluft RP. An overview of the psychotherapy of dissociative identity disorder. Am J Psychother. 1999;53:289–319. **Overview of DID treatment highlighting the similarities and differences with the treatment of other trauma-related conditions

- [8]. International Society For The Study of Trauma and Dissociation. Guidelines for Treating Dissociative Identity Disorder in Adults, Third Revision. J Trauma Dissociation. 2011;12:115–187. **Comprehensive expert consensus guidelines for the treatment of dissociative disorders, encompassing psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic recommendations.

- [9]. Loewenstein RJ. Dissociation debates: everything you know is wrong. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20:229–242. *Comprehensive analysis of common myths related to DID and dissociative disorders highlighting its trauma-relatedness, validity, and treatability

- [10].Loewenstein RJ. Psychopharmacologic Treatments for Dissociative Identity Disorder. Psychiatr Ann. 2005;35:666–673. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Laddis A The disorder-specific psychological impairment in complex PTSD: A flawed working model for restoration of trust. J Trauma Dissociation. 2019;20:79–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gentile S Drug treatment for mood disorders in pregnancy. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24:34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Sutar R, Sahu S. Pharmacotherapy for dissociative disorders: A systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2019;281:112529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Putnam FW. The way we are: how states of mind influence our identities, personality and potential for change. New York: IPBooks; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lebois LAM, Wolff JD, Ressler KJ. Neuroimaging genetic approaches to Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Exp Neurol. 2016;284:141–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Reinders A a. TS, Chalavi S, Schlumpf YR, et al. Neurodevelopmental origins of abnormal cortical morphology in dissociative identity disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;137:157–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lebois LAM, Kaplan CS, Palermo CA, et al. A Grounded Theory of Dissociative Identity Disorder: Placing DID in Mind, Brain, and Body. In: Dorahy MJ, Gold SN, O’Neil JA, editors. Dissociation Dissociative Disord. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge; 2022. p. 380–391. [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Dalenberg CJ, Brand BL, Gleaves DH, et al. Evaluation of the evidence for the trauma and fantasy models of dissociation. Psychol Bull. 2012;138:550–588. *Empirical investigation which refuted the fantasy model of dissociation and found support for the trauma model of dissociation

- [19]. Putnam FW. Dissociation in children and adolescents: a developmental perspective. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1997. **Seminal text for clinicians which describes treatment approaches for patients with DID

- [20]. Dell PF. A new model of dissociative identity disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2006;29:1–26, vii. *Investigation of three models of DID which found support for a traumatogenic model highlighting the complexity of symptomology and dissociative intrusions

- [21].Chefetz RA. Intensive psychotherapy for persistent dissociative processes: the fear of feeling real First edition. New York: W.W. Norton & Company; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Barsalou LW. Grounded cognition. Annu Rev Psychol. 2008;59:617–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Brenner I Dissociation of trauma: theory, phenomenology, and technique. Madison (Conn.): International universities press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Chefetz RA, Bromberg PM. Talking with “Me” and “Not-Me”: A Dialogue. Contemp Psychoanal. 2004;40:409–464. *Case-based discussion highlighting the importance of developing a shared language around affect and self-states with patients

- [25].Brand B, Classen C, Lanins R, et al. A naturalistic study of dissociative identity disorder and dissociative disorder not otherwise specified patients treated by community clinicians. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2009;1:153–171. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Brand B, Loewenstein RJ. Dissociative disorders: An overview of assessment, phenomenology, and treatment. Psychiatr Times. 2010;27:62–69. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Shinn AK, Wolff JD, Hwang M, et al. Assessing Voice Hearing in Trauma Spectrum Disorders: A Comparison of Two Measures and a Review of the Literature. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Renard SB, Huntjens RJC, Lysaker PH, et al. Unique and Overlapping Symptoms in Schizophrenia Spectrum and Dissociative Disorders in Relation to Models of Psychopathology: A Systematic Review. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43:108–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Steinberg M, Siegel HD. Advances in Assessment: The Differential Diagnosis of Dissociative Identity Disorder and Schizophrenia. In: Moskowitz A, Schäfer I, Dorahy MJ, editors. Psychos Trauma Dissociation. 1st ed. Wiley; 2008. p. 177–189. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Brand B, Loewenstein R. Dissociative Disorders: An Overview of Assessment, Phenomonology and Treatment. Psychiatr Times. 2010; [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kluft RP. The phenomenology and treatment of extremely complex multiple personality disorder. Dissociation Prog Dissociative Disord. 1988; [Google Scholar]

- [32].Arntz A, Rijkeboer M, Chan E, et al. Towards a Reformulated Theory Underlying Schema Therapy: Position Paper of an International Workgroup. Cogn Ther Res. 2021;45:1007–1020. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Van Der Linde RPA, Huntjens RJC, Bachrach N, et al. Personality disorder traits, maladaptive schemas, modes and coping styles in participants with complex dissociative disorders, borderline personality disorder and avoidant personality disorder. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2023;30:1234–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Brenner I Injured men: trauma, healing, and the masculine self. Lanham: Aronson; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [35]. Kluft RP. Dealing with alters: a pragmatic clinical perspective. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2006;29:281–304, xii. *In depth exploration of “alters”, that is, self-states, which are a core feature of DID

- [36].Loewenstein RJ. Firebug! Dissociative Identity Disorder? Malingering? Or …? An Intensive Case Study of an Arsonist. Psychol Inj Law. 2020;13:187–224. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Armstrong J The psychological organization of multiple personality disordered patients as revealed in psychological testing. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1991;14:533–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38]. Brand BL, Armstrong JG, Loewenstein RJ. Psychological Assessment of Patients with Dissociative Identity Disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2006;29:145–168. *Thorough review of available tools to assess dissociation along with psychometrics of each measure

- [39].Howell EF. Understanding and treating dissociative identity disorder: a relational approach. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kluft RP. A clinician’s understanding of dissociation: Fragments of an acquaintance. Dissociation Dissociative Disord DSM-V Beyond. 2009;599–623. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Stout M The myth of sanity: divided consciousness and the promise of awareness. New York: Penguin Books; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Schwartz HL. Dialogues with forgotten voices: relational perspectives on child abuse trauma and treatment of dissociative disorders. New York: Basic Books; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Spiegel D, Loewenstein RJ, Lewis-Fernández R, et al. Dissociative disorders in DSM-5. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28:824–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Putnam FW. The switch process in multiple personality disorder and other state-change disorders. Dissociation Prog Dissociative Disord. 1988;1:24–32. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Putnam FW. Diagnosis and treatment of multiple personality disorder. 2. [print.]. New York: Guilford Pr; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Radulovic J, Lee R, Ortony A. State-Dependent Memory: Neurobiological Advances and Prospects for Translation to Dissociative Amnesia. Front Behav Neurosci. 2018;12:259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Steinberg M Handbook for the assessment of dissociation: A clinical guide. Handb Assess Dissociation Clin Guide. 1995;xvii, 433–xvii, 433. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Dell PF. Involuntariness in hypnotic responding and dissociative symptoms. J Trauma Dissociation Off J Int Soc Study Dissociation ISSD. 2010;11:1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Kate M-A, Jamieson G, Dorahy MJ, et al. Measuring Dissociative Symptoms and Experiences in an Australian College Sample Using a Short Version of the Multidimensional Inventory of Dissociation. J Trauma Dissociation Off J Int Soc Study Dissociation ISSD. 2021;22:265–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50]. Dorahy MJ, Middleton W, Seager L, et al. Dissociation, shame, complex PTSD, child maltreatment and intimate relationship self-concept in dissociative disorder, chronic PTSD and mixed psychiatric groups. J Affect Disord. 2015;172:195–203. *Review article proposing a diathesis-stress model of dissociative disorders in which high hypnotizability may be a diathesis for pathological dissociation in the context of acute traumatic stress

- [51].Dell PF. Reconsidering the autohypnotic model of the dissociative disorders. J Trauma Dissociation Off J Int Soc Study Dissociation ISSD. 2019;20:48–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Butler LD, Duran RE, Jasiukaitis P, et al. Hypnotizability and traumatic experience: a diathesis-stress model of dissociative symptomatology. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:42–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Kluft RP. Hypnosis in the Treatment of Dissociative Identity Disorder and Allied States: An Overview and Case Study. South Afr J Psychol. 2012;42:146–155. [Google Scholar]

- [54].Piccione C, Hilgard ER, Zimbardo PG. On the degree of stability of measured hypnotizability over a 25-year period. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;56:289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Spiegel H, Spiegel D. Trance & Treatment: Clinical Uses of Hypnosis. 2nd Edition. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Orne MT. The nature of hypnosis: Artifact and essence. J Abnorm Soc Psychol. 1959;58:277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Dell PF, Lawson D. An empirical delineation of the domain of pathological dissociation In Dell PF & O’Neil JA. Dissociation Dissociative Disord DSM-IV Beyond. 2009;667–692. [Google Scholar]

- [58].Bliss EL. Multiple personality, allied disorders, and hypnosis. Mult Personal Allied Disord Hypn. 1986;ix, 271–ix, 271. [Google Scholar]

- [59].Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Gene-environment interactions in psychiatry: joining forces with neuroscience. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:583–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Wolf EJ, Rasmusson AM, Mitchell KS, et al. A genome‐wide association study of clinical symptoms of dissociation in a trauma‐exposed sample. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31:352–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Wolf EJ, Hawn SE, Sullivan DR, et al. Neurobiological and genetic correlates of the dissociative subtype of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychopathol Clin Sci. 2023; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]