Abstract

Background

The TRANSFORM-HF trial found no significant difference in all-cause mortality or hospitalization among patients randomized to a strategy of torsemide versus furosemide following a heart failure (HF) hospitalization. However, outcomes and responses to some therapies differ by left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Thus, we sought to explore the effect of torsemide versus furosemide by baseline LVEF and to assess outcomes across LVEF groups.

Methods

We compared baseline patient characteristics and randomized treatment effects for various endpoints in TRANSFORM-HF stratified by LVEF: HF with reduced (LVEF≤40%; HFrEF) vs mildly reduced (LVEF 41–49%; HFmrEF) vs preserved (LVEF≥50%; HFpEF) LVEFs. We also evaluated associations between LVEF and clinical outcomes. Study endpoints were all-cause mortality and hospitalization at 30 days and 12 months, total hospitalizations at 12 months, and change from baseline in Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire clinical summary score (KCCQ-CSS).

Results

Overall, 2,635 patients (median 64 years, 36% female, 34% Black) had LVEF data. Compared with HFrEF, patients with HFmrEF and HFpEF had a higher prevalence of comorbidities. After adjusting for covariates, there was no significant difference in risk of clinical outcomes across the LVEF groups (adjusted HR for 12-month all-cause mortality: 0.91;95%CI: 0.59–1.39 for HFmrEF vs HFrEF and 0.91;0.70–1.17 for HFpEF vs HFrEF, p=0.73). In addition, there was no significant difference between torsemide and furosemide (i) for mortality and hospitalization outcomes, irrespective of LVEF group and (ii) in changes in KCCQ-CSS in any LVEF subgroup.

Conclusions

Despite baseline demographic and clinical differences between LVEF cohorts in TRANSFORM-HF, there were no significant differences in the clinical endpoints with torsemide vs furosemide across the LVEF spectrum. There was a substantial risk for all-cause mortality and subsequent hospitalization independent of baseline LVEF.

Subject terms: heart failure

Keywords: loop diuretics, outcomes, mortality, hospitalization, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Congestion is a hallmark feature of acutely decompensated heart failure (HF) and predominates the clinical presentation of >80% of patients hospitalized for this diagnosis.1 Although loop diuretic remains the mainstay of treatment for congested patients with HF, reliable data on their optimal use remain sparse, permitting wide variation in decongestion strategies among physicians.2 Previous preclinical and clinical studies had suggested favorable effects of torsemide over furosemide relative to aldosterone secretion and binding, myocardial fibrosis and remodeling, and reduction of natriuretic peptide levels.3,4 The seminal TRANSFORM-HF (Torsemide Comparison With Furosemide for Management of Heart Failure) trial investigated the effect of torsemide vs furosemide in patients hospitalized with HF and demonstrated that there was no significant difference in the primary outcome of all-cause mortality nor in the secondary outcomes of all-cause mortality and/or all-cause hospitalization, and total hospitalizations.5

Although the different categories of HF defined by EF (HF with reduced [HFrEF] vs HF with mildly reduced [HFmrEF] vs HF with preserved ejection fraction [HFpEF]) share some common features, several distinct biological pathways are implicated in their pathogenesis,6 likely underlying the variability in associated comorbidities, responses to therapies, and clinical outcomes.7 Thus, it is important to determine whether the effects of torsemide vs furosemide differ according to patients’ baseline left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). The current work is a prespecified analysis of the TRANSFORM-HF trial, assessing (1) the effect of torsemide vs furosemide on the trial’s outcomes across the enrolled LVEF spectrum, and (2) the difference in outcomes across LVEF groups.

METHODS

Trial Design and Participants

Details on the design of the TRANSFORM-HF trial have been previously published.8 In summary, TRANSFORM-HF was an open-label, prospective, randomized, event-driven trial that enrolled patients hospitalized for HF across 60 hospitals in the United States. Patients were enrolled regardless of LVEF and HF history. Eligible patients were required to have a plan for daily outpatient treatment with an oral loop diuretic with anticipated long-term use. The full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria are reported elsewhere.8 Data on race and ethnicity were collected in accordance with the National Institutes of Health recommendations.

All patients provided written informed consent, and the study protocol was approved by each site’s institutional review board or the central institutional review board. The data supporting the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Trial Intervention

Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio without stratification to either a strategy of furosemide or torsemide. The frequency and the dose of the randomized treatment both in-hospital and at discharge were determined by the treating clinician, whereas changes in loop diuretics after discharge was at the discretion of each patient’s treating physician in the outpatient setting.

After discharge, there was no additional study-specific patient contact required by sites. Follow-up was centralized through the Duke Clinical Research Institute call center, with participants having telephone interviews at 1, 6 and 12 months after enrollment.

Study Endpoints

The outcomes for this secondary analysis of TRANSFORM-HF were (i) all-cause mortality over 12 months, (ii) all-cause mortality or hospitalization over 12 months, (iii) all-cause mortality or hospitalization over 30 days (iv) all-cause hospitalizations over 12 months, and (v) total hospitalizations over 12 months. Change from baseline to 12 months in the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) clinical summary score (CSS) was also assessed.9

Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction

At the time of randomization, site investigators entered the most recent available (within 24 months) LVEF into an automated, web-based system. In line with the universal definition of HF and HF guidelines, LVEF in this analysis was categorized as HFrEF (LVEF ≤40%), HFmrEF (LVEF 41%−49%) and HFpEF (LVEF ≥50%).10 Analyses were also performed using LVEF as a continuous variable.

Statistical analysis

The primary analytic population for this report was comprised of all randomly assigned participants with available LVEF data at baseline. All analyses of randomized treatment effect were based on the intention-to-treat principle. Baseline characteristics are summarized as mean (SD), median (25th– 75th percentile), or n (%), and evaluated using χ2, ANOVA, and Kruskal-Wallis, as appropriate.

To evaluate the association between LVEF group and clinical outcomes, we calculated unadjusted rates of the trial clinical outcomes for each LVEF group. To assess relative risk across the three EF groups, multivariate Cox regression models for all-cause mortality over 12 months, all-cause mortality/hospitalization over 12 months, and the Fine and Gray competing risk model for all-cause hospitalization over 12 months were used.11 The negative binomial regression model was used to assess relative risk across the 3 EF groups for the total hospitalizations over 12 months endpoint. For all models, LVEF ≤40% was specified as the reference group. The assumptions of the Cox proportional hazard model were confirmed using the method based on Schoenfeld residuals. The relationship between continuous LVEF and endpoints by sex was described using restricted cubic splines using 4 knots (5th, 35th, 65th, and 95th). The change in KCCQ-CSS from baseline to 12 months was analyzed using a linear mixed model with an unstructured covariance matrix adjusted for age, sex, race, loop diuretic treatment prior to index hospital, systolic blood pressure, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), body mass index, diabetes, atrial fibrillation/flutter and HF medication at discharge.

To assess treatment effect for torsemide versus furosemide, LVEF subgroup analyses were performed. The hazard ratio (HR) for torsemide vs. furosemide, 95% confidence interval (CI), and interaction p-value for the randomized treatment effect within the LVEF category was derived using a Cox regression model adjusted for age, sex, baseline EF (<40%, 41–49%, >50%), and loop diuretic treatment prior to index hospital admission. HR, 95% CI and p-value for the all-cause hospitalization over 12 months outcome was based on a Fine and Gray competing risk model including the assigned treatment.11 The assumptions of the Cox proportional hazard model were checked confirmed using the method based on Schoenfeld residuals.

For analyses of change in KCCQ-CSS from baseline to 12 months, a linear mixed model was used with an unstructured covariance matrix adjusted for age, sex and loop diuretic treatment prior to index hospital. Repeated measures were the KCCQ-CSS score change from baseline by visit. The frequency of the total hospitalization over 12 months was analyzed by negative binomial regression with relative risks and 95% CIs provided. Hazard for all-cause mortality over 12 months, all-cause mortality/hospitalization over 12 months, and all-cause hospitalization over 12 months for torsemide vs furosemide across the LVEF spectrum was also calculated and shown as restricted cubic spline of LVEF based on 4 knots (5th, 35th, 65th, and 95th) on the x axis and the result of Cox regression model outcome expressed as HR (95% CI) on the y axis.

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Two-tailed P-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient Population

A total of 2,859 patients were enrolled in the TRANSFORM-HF trial. Of those 2,635 (92.1%), 1,334/1,431 (93.2%) in the torsemide and 1,301/1,428 (91.1%) in the furosemide arm, had available data on LVEF and were included in this analysis. The mean age of the patient population was 64 years, 36% were female and 34% Black (Table 1). Forty five percent of patients had a history of atrial fibrillation, and 48% of patients had a history of diabetes. Approximately one third of the patients had de novo HF (Table 1). The proportion of patients with HFrEF, HFmrEF and HFpEF in the analysis population was 69.7%, 5.7% and 24.6%, respectively (Table S1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants stratified on LVEF

| ≤40% (N=1,836) |

41–49% (N=151) |

≥50% (N=648) |

All Patients (N=2,635) |

P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 61.7 (13.8) | 67.1 (13.2) | 70.1 (12.7) | 64.1 (14.0) | <0.0001 |

| Female sex | 567 (30.9%) | 59 (39.1%) | 326 (50.3%) | 952 (36.1%) | <0.001 |

| Black or African American Race | 667 (36.4%) | 52 (34.7%) | 169 (26.1%) | 888 (33.8%) | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 31.31 (9.02) | 33.42 (9.58) | 34.38 (10.31) | 32.19 (9.48) | <0.0001 |

| Laboratory values | |||||

| Sodium, mEq/L | 137.5 (3.6) | 138.2 (3.6) | 138.3 (3.7) | 137.7 (3.6) | <0.0001 |

| Potassium, mEq/L | 4.05 (0.45) | 4.02 (0.49) | 4.02 (0.47) | 4.04 (0.45) | 0.1570 |

| Blood urea nitrogen, mg/dL | 31.3 (37.0) | 33.5 (36.8) | 36.3 (41.3) | 32.7 (38.1) | 0.0001 |

| Estimated Glomerular filtration rate *, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 62.6 (24.4) | 60.3 (25.9) | 55.2 (24.6) | 60.6 (24.7) | <0.0001 |

| N-Terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide†, pg/mL | 4554.0 (2368.0, 9620.0) | 3333.5 (1510.5, 7705.0) | 2763.5 (1307.0, 5400.0) | 3907.0 (1932.0, 8385.0) | <0.0001 |

| B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP)†, pg/mL | 1265.0 (643.7, 2258.5) | 764.0 (420.0, 1466.2) | 528.5 (311.5, 958.5) | 1016.0 (500.0, 1870.0) | <0.0001 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 12.50 (3.71) | 11.21 (2.45) | 11.43 (7.41) | 12.16 (4.87) | <0.0001 |

| Vital signs | |||||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 114.4 (17.9) | 122.8 (17.9) | 129.1 (20.3) | 118.5 (19.6) | <0.0001 |

| Heart rate, BPM | 82.8 (15.8) | 78.3 (15.2) | 76.2 (15.1) | 80.9 (15.8) | <0.0001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 70.6 (13.2) | 67.4 (12.5) | 68.3 (12.5) | 69.9 (13.0) | 0.0004 |

| Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) | |||||

| KCCQ Baseline Clinical Summary Score | 43 (27, 61) | 39 (24, 61) | 38 (23, 56) | 42 (26, 60) | 0.0007 |

| Heart failure (HF) characteristics | |||||

| Newly diagnosed HF (de novo) | 558 (30.4%) | 39 (25.8%) | 188 (29.0%) | 785 (29.8%) | 0.441 |

| Ischemic etiology | 586 (31.9%) | 50 (33.1%) | 120 (18.5%) | 756 (28.7%) | <0.001 |

| General medical history | |||||

| Atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter | 739 (40.6%) | 74 (49.0%) | 353 (54.6%) | 1166 (44.5%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 843 (45.9%) | 81 (53.6%) | 339 (52.3%) | 1263 (47.9%) | 0.007 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 589 (32.1%) | 59 (39.1%) | 271 (41.8%) | 919 (34.9%) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1425 (77.8%) | 131 (87.3%) | 580 (89.5%) | 2136 (81.2%) | <0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 850 (46.4%) | 93 (62.8%) | 379 (58.6%) | 1322 (50.4%) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 141 (7.7%) | 19 (12.8%) | 47 (7.3%) | 207 (7.9%) | 0.074 |

| Coronary artery disease | 835 (45.5%) | 77 (51.3%) | 303 (46.8%) | 1215 (46.2%) | 0.367 |

| Myocardial infarction | 458 (25.1%) | 36 (23.8%) | 109 (16.9%) | 603 (23.0%) | <0.001 |

| Prior PCI | 403 (22.1%) | 37 (24.7%) | 109 (16.9%) | 549 (21.0%) | 0.010 |

| Prior CABG | 272 (14.9%) | 26 (17.2%) | 111 (17.2%) | 409 (15.6%) | 0.325 |

| Chronic lung disease (including COPD) | 386 (21.1%) | 44 (29.5%) | 194 (30.4%) | 624 (23.8%) | <0.001 |

| Stroke / TIA | 211 (11.6%) | 21 (14.0%) | 103 (16.1%) | 335 (12.8%) | 0.012 |

| Current smoker | 330 (18.0%) | 22 (14.7%) | 67 (10.4%) | 419 (16.0%) | <0.001 |

| Implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) | 495 (27.0%) | 15 (9.9%) | 49 (7.6%) | 559 (21.2%) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) | 173 (9.4%) | 7 (4.6%) | 27 (4.2%) | 207 (7.9%) | <0.001 |

| Loop diuretics | |||||

| Oral loop diuretic prior to index hospital admission (most recent) | 1178 (64.2%) | 104 (68.9%) | 477 (73.6%) | 1759 (66.8%) | <0.001 |

| Total daily dose prescribed (furosemide equivalents)*, mg | 67.4 (62.5) | 60.3 (47.5) | 64.3 (64.3) | 66.1 (62.2) | 0.3468 |

| Prescribed assigned loop diuretic at discharge‡ | 1599 (87.1%) | 134 (88.7%) | 573 (88.4%) | 2306 (87.5%) | 0.620 |

| Total daily dose prescribed (furosemide equivalents)‡, mg | 81.2 (66.5) | 75.3 (56.4) | 77.8 (59.3) | 80.0 (64.2) | 0.7987 |

| Baseline medications taken at the time of randomization | |||||

| ACEi or ARB or ARNi | 1240 (67.5%) | 83 (55.0%) | 277 (42.7%) | 1600 (60.7%) | <0.001 |

| Aldosterone antagonist / mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA) | 814 (44.3%) | 38 (25.2%) | 120 (18.5%) | 972 (36.9%) | <0.001 |

| Beta blocker | 1497 (81.5%) | 123 (81.5%) | 469 (72.4%) | 2089 (79.3%) | <0.001 |

| SGLT-2 inhibitor | 139 (7.8%) | 5 (3.5%) | 17 (2.7%) | 161 (6.3%) | <0.001 |

| Thiazide diuretic | 65 (3.6%) | 7 (4.7%) | 43 (6.7%) | 115 (4.4%) | 0.004 |

2021 CKD EPI formula for GFR was used to calculate the estimated glomerular filtration rate based on creatinine and patient characteristics.

Highest value recording during the index hospitalization.

Loop diuretic doses were converted to Furosemide equivalents with 1mg Bumetanide = 20mg Torsemide = 50mg Ethacrynic acid = 40mg Furosemide for oral diuretics.

ACEi: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB: angiotensin receptor blockers; ARNi: angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitor; BMI: body mass index; CABG: coronary artery bypass graft surgery; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; SGLT-2: Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2; TIA: transient ischemic attack

The baseline characteristics of the trial participants across the 3 LVEF subgroups are shown in Table 1. Participants with HFpEF were more often female, older, with higher blood urea nitrogen and lower eGFR compared to the other LVEF cohorts. Patients with HFrEF had higher heart rate and natriuretic peptide levels and lower systolic blood pressure, while patients with HFmrEF had higher prevalence of diabetes, hypercholesterolemia and coronary artery disease.

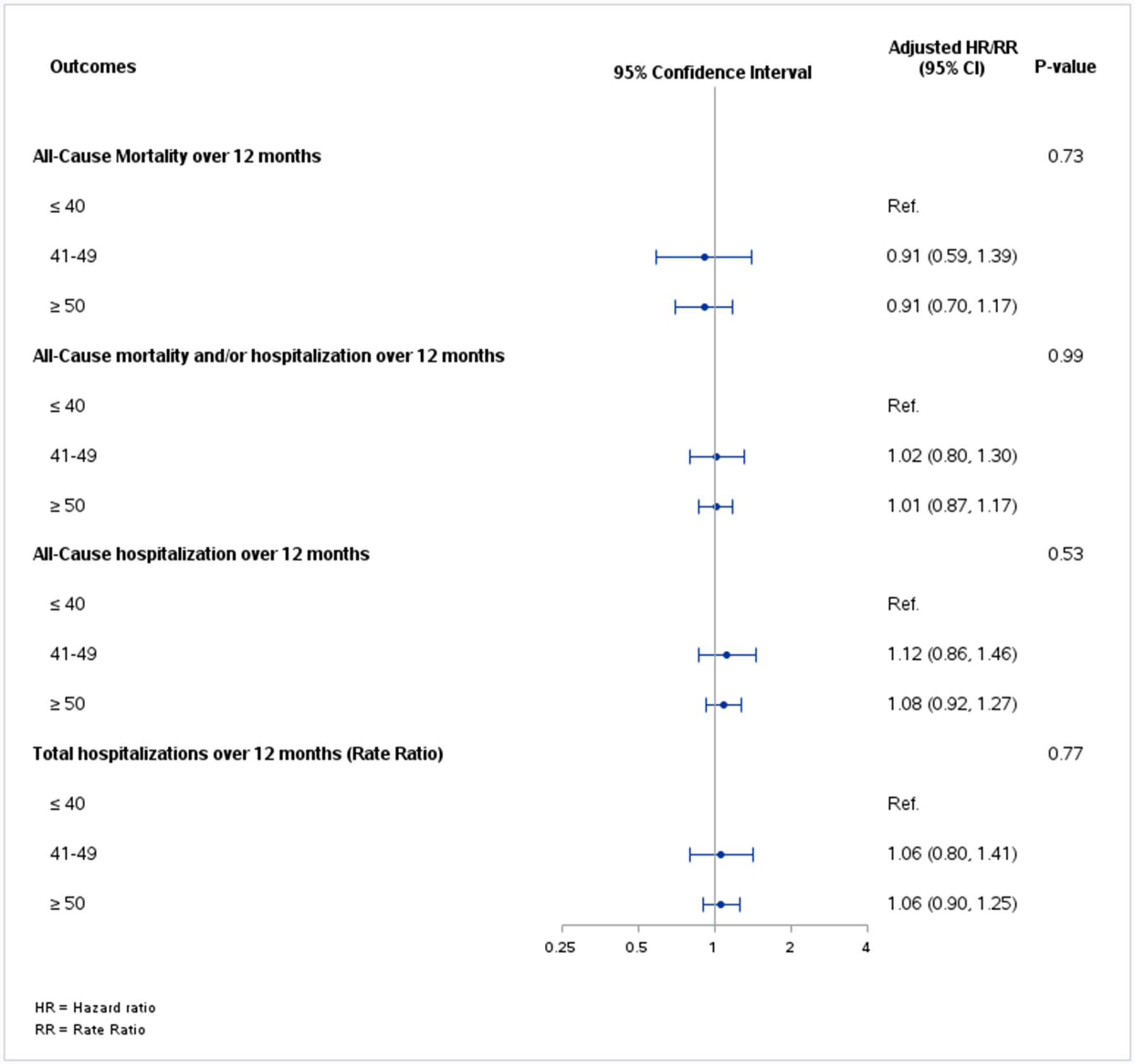

Association of LVEF with clinical endpoints in the patient population

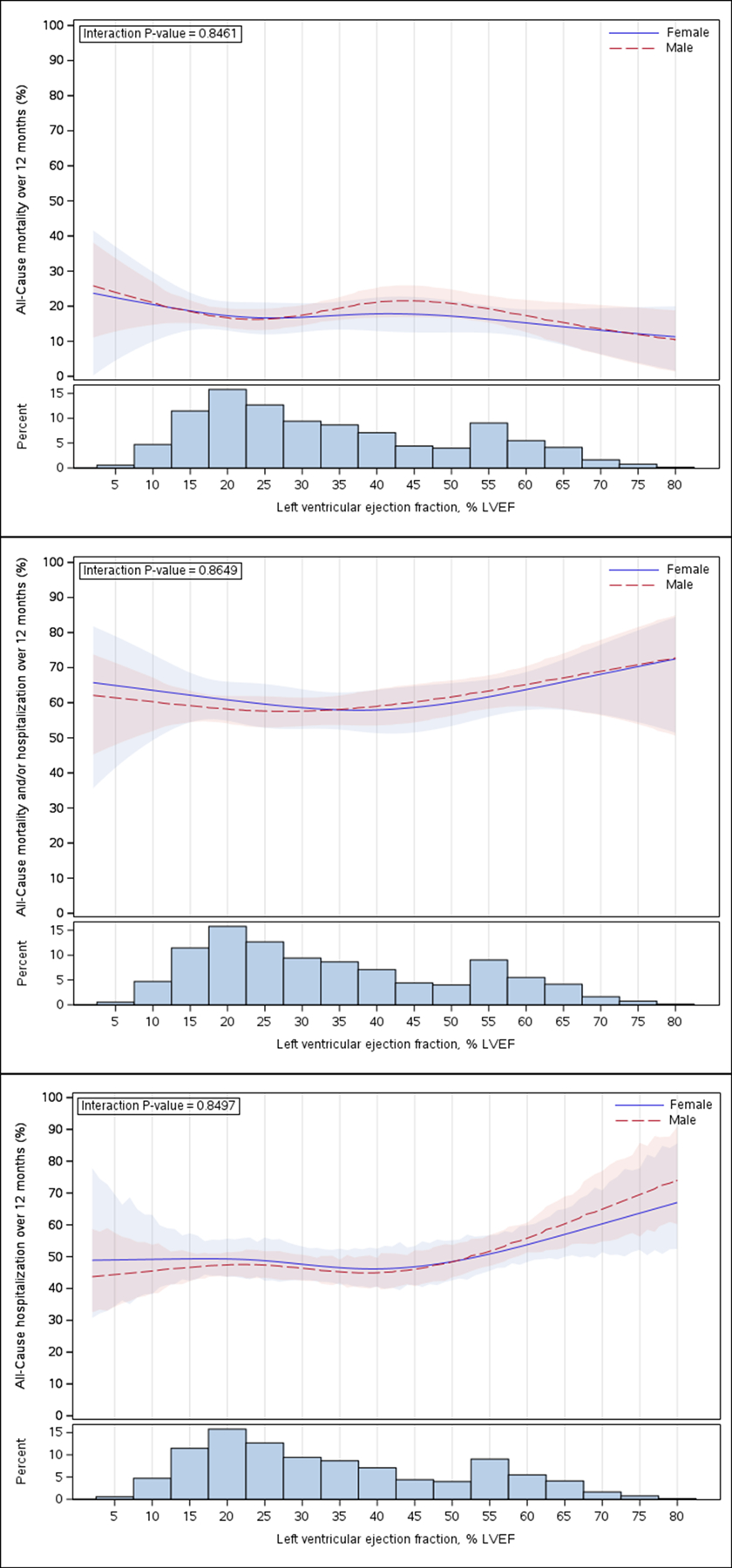

In both the unadjusted and adjusted analysis, the hazard ratios or rate ratios for the primary and secondary endpoints did not differ significantly across LVEF groups (interaction P-value>0.05, Table 2 and Figure 1). The cumulative incidence rates of 12-month all-cause mortality were 17.9, 17.2 and 17.4 deaths per 100 patient-years for HFrEF, HFmrEF and HFpEF, respectively (adjusted HR: 0.91; 95%CI: 0.59–1.39 for HFmrEF vs HFrEF and adjusted HR: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.70–1.17 for HFpEF vs HFrEF, p-value for interaction=0.73). The respective rates of 12-month all-cause hospitalization were 47.4, 51.9 and 52.1 events per 100 patient-years (adjusted HR: 1.12; 95% CI: 0.86–1.46 for HFmrEF vs HFrEF and adjusted HR: 1.08; 95% CI: 0.92–1.27 for HFpEF vs HFrEF, p-value for interaction=0.53). Restricted cubic splines plot for the unadjusted results of all-cause mortality and over 12 months, all-cause mortality and/or hospitalization over 12 months, all-cause hospitalizations over 12 months across the spectrum of LVEF, stratified by sex showed no significant difference (interaction P-value>0.05, Figure 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate model results assessing relative risk of the clinical endpoints across the 3 EF groups

| Outcomes (ref. ≤40%) | Events | KM or CIF at 12 months (%) or Total event rate per 100 pt-years | Unadjusted HR or RR (95% CI) | Unadjusted p-value | Adjusted HR or RR (95% CI)# | Adjusted p-value# |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-Cause mortality over 12 months *, †, ‡ | ||||||

| ≤ 40% | 300 | 17.9 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| 41–49% | 24 | 17.2 | 0.93 (0.62 – 1.42) | 0.75 | 0.91 (0.59 – 1.39) | 0.66 |

| ≥ 50% | 104 | 17.4 | 0.94 (0.75 – 1.18) | 0.61 | 0.91 (0.70 – 1.17) | 0.46 |

| All-Cause mortality and/or hospitalization over 12 months ‡ | ||||||

| ≤ 40% | 852 | 59.2 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| 41–49% | 72 | 61.0 | 1.09 (0.86 – 1.38) | 0.49 | 1.02 (0.80 – 1.30) | 0.90 |

| ≥ 50% | 334 | 63.0 | 1.11 (0.98 – 1.26) | 0.10 | 1.01 (0.87 – 1.17) | 0.91 |

| All-Cause hospitalization over 12 months § | ||||||

| ≤ 40% | 681 | 47.4 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| 41–49% | 62 | 51.9 | 1.17 (0.90 – 1.51) | 0.24 | 1.12 (0.86 – 1.46) | 0.40 |

| ≥ 50% | 278 | 52.1 | 1.17 (1.02 – 1.35) | 0.03 | 1.08 (0.92 – 1.27) | 0.36 |

| Total hospitalizations over 12 months ∥ | ||||||

| ≤ 40% | 118 | 105.5 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| 41–49% | 102 | 112.8 | RR = 1.10 (0.83, 1.46) | 0.52 | RR = 1.06 (0.80, 1.41) | 0.66 |

| ≥ 50% | 502 | 119.0 | RR = 1.14 (0.98, 1.32) | 0.08 | RR = 1.06 (0.90, 1.25) | 0.51 |

All-cause mortality includes verified deaths with confirmation from an acceptable obituary or grave marker, a second proxy confirming that the patient died, or an official medical record and deaths from the National Death Index (NDI) search or verified by the Mortality Review Committee.

Primary time to censoring: Patients randomized 2018–2021 and included in the NDI search are censored through the max of the Call Center last known alive date and 12/31/2021; patients not included in the NDI search or randomized in 2022 are censored through the Call Center last known alive date.

Hazard ratio (HR), 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value are based on a Cox proportional hazards regression model.

Hazard ratio (HR), 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value are based on a Fine and Gray competing risk (CR) model. In the competing risk model, subjects who did not have an event and died were considering competing risks (i.e., precludes the occurrence of the event of interest) and have a different censoring code from those who were alive at censoring.

Rate Ratio (RR), 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value are from a negative binomial regression (NBR) of the frequency of re-hospitalizations with an offset term of the log of each subject’s months to last rehospitalization assessment through month 12.

Age, Sex, Race, Loop diuretic treatment prior to index hospital, Systolic blood pressure, eGFR, Body Mass Index, Diabetes, Atrial fibrillation/flutter, Meds at discharge (beta-blocker, ACEI/ARB, ARNI, MRA, SGLT2i).

KM = Kaplan Meier. CIF = Cumulative Incidence Function

Figure 1.

Forest plot depicting hazard ratios (HR)/rate ratio (RR) assessing relative risk of all clinical endpoints across the 3 left ventricular ejection fraction groups

Figure 2. Unadjusted hazard for the all-cause mortality at 12 months (upper), all-cause mortality and/or all-cause hospitalization at 12 months (middle) and all-cause hospitalization at 12 months (lower) across the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) stratified by sex.

Restricted cubic spline of (4-spline knot) spline of LVEF on the x axis and the result of Cox regression model expressed as hazard ratios (95% CI) on the y axis. Line represents the point estimate for the HR and the shaded region the 95% confidence intervals. The bars on the lower panel represent distribution of patients across LVEF.

In regards to the KCCQ-CSS, in both the unadjusted and adjusted analyses, the improvement in the CSS between baseline and 12-month follow-up as expressed by the estimated difference in means was significantly less pronounced in the HFmrEF and HFpEF subgroups when compared with the HFrEF subgroup (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of KCCQ Clinical Summary Score by LVEF levels – Least Square Mean by Visit *

| Unadjusted | Adjusted† | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Least Square Mean | Estimated Difference in Means (95% CI) (41–49, ≥ 50 vs ≤ 40) |

P-value | Least Square Means | Estimated Difference in Means (95% CI) (41–49, ≥ 50 vs ≤ 40) |

P-value | |

| Month 12 Change from Baseline (95% CI) | |||||||

| ≤ 40% | 31.92 (30.46, 33.38) | Ref. | 25.29 (22.22, 28.36) | Ref. | |||

| 41–49% | 24.92 (19.69, 30.14) | −7.01 (−12.43, −1.59) | 0.011 | 19.24 (13.37, 25.10) | −6.05 (−11.44, −0.67) | 0.011 | |

| ≥ 50% | 25.78 (23.39, 28.18) | −6.14 (−8.95, −3.33) | <0.001 | 20.55 (16.79, 24.31) | −4.74 (−7.74, −1.73) | 0.002 | |

The Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) clinical summary score (CSS) is the mean of the physical limitation and total symptom scores. The score ranges from 0 to 100 where higher scores reflect better health status. Baseline defined as the last KCCQ prior to randomization for each subject. Change from baseline = observed value - baseline value.

Age, Sex, Race, Loop diuretic treatment prior to index hospital, Systolic blood pressure, eGFR, Body Mass Index, Diabetes, Atrial fibrillation/flutter, Meds at discharge (beta-blocker, ACEI/ARB, ARNI, MRA, SGLT2i).

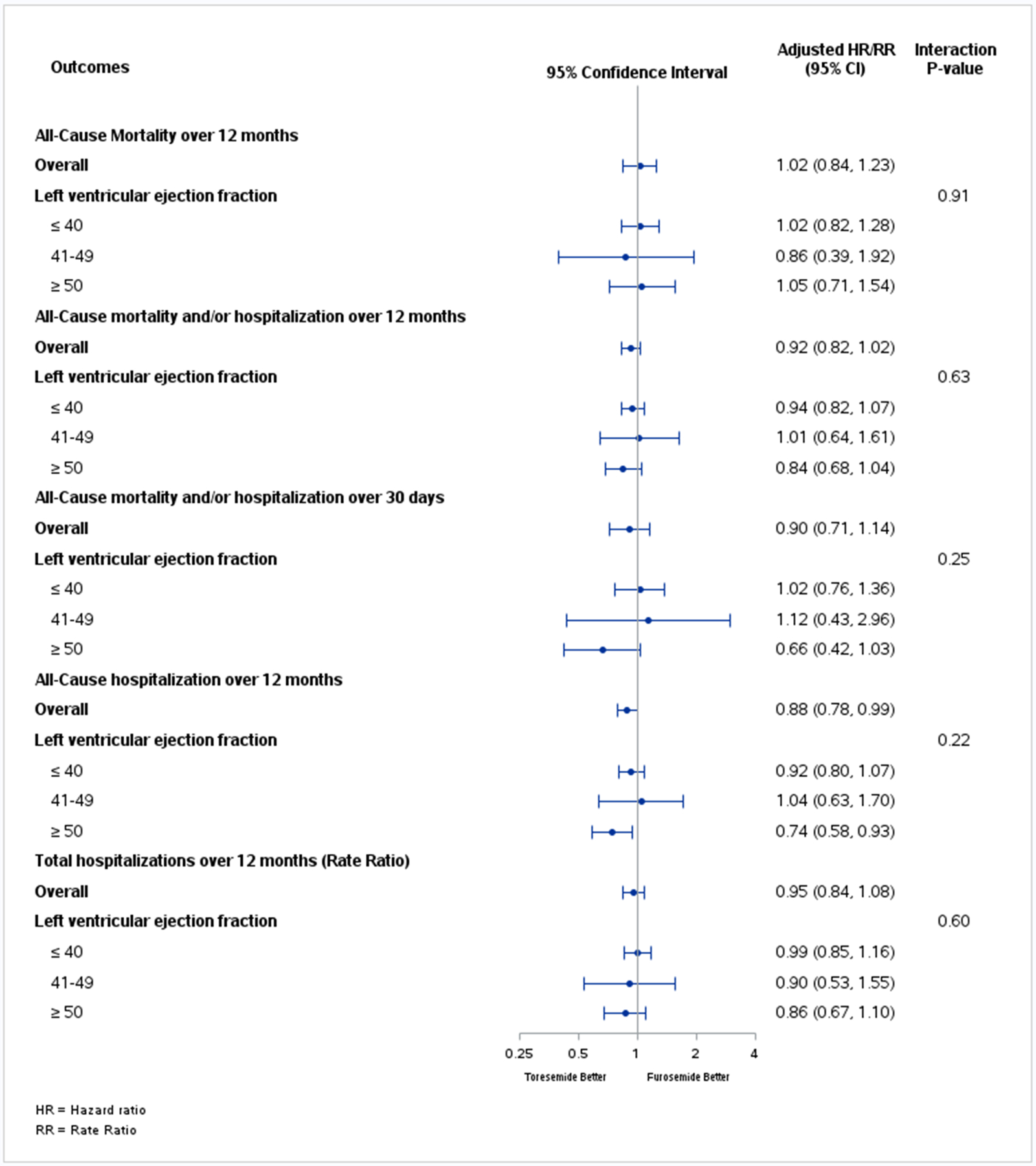

Treatment effect of torsemide versus furosemide by ejection fraction

Table 4 reports the treatment effect and 95% CI for clinical outcomes in the overall population and within each LVEF subgroup. There was no significant difference between torsemide and furosemide for any clinical endpoint, with consistently neutral findings irrespective of LVEF subgroup (all p for interaction >0.20). The forest plot of the HRs/RRs of the treatment effect for HFrEF vs HFmrEF vs HFpEF for all clinical endpoints is shown in Figure 3. The treatment effects for HFrEF vs HFmrEF vs HFpEF for total hospitalizations through month 12 when analyzed with a first and repeated event rather than a time-to-event method are depicted in Table S2.

Table 4.

Treatment effect for heart failure with reduced (HFrEF) vs mildly reduced (HFmrEF) vs preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) for the primary and secondary clinical endpoints

| Outcomes | Torsemide Event (%) |

Furosemide Event (%) |

Adjusted Hazard Ratios or Rate Ratios (RR) (95% CI) |

P Value for interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-Cause Mortality over 12 months *, †, ‡ | ||||

| Overall | 218 (16.3%) | 212 (16.3%) | 1.02 (0.84, 1.23) | |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | 0.91 | |||

| ≤ 40% | 154 (16.5%) | 148 (16.4%) | 1.02 (0.82, 1.28) | |

| 41–49% | 12 (14.8%) | 12 (17.1%) | 0.86 (0.39, 1.92) | |

| ≥ 50% | 52 (16.4%) | 52 (15.8%) | 1.05 (0.71, 1.54) | |

| All-Cause mortality and/or hospitalization over 12 months ‡ | ||||

| Overall | 629 (47.2%) | 635 (48.8%) | 0.92 (0.82, 1.02) | |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | 0.63 | |||

| ≤ 40% | 432 (46.2%) | 423 (46.9%) | 0.94 (0.82, 1.07) | |

| 41–49% | 41 (50.6%) | 32 (45.7%) | 1.01 (0.64, 1.61) | |

| ≥ 50% | 156 (49.1%) | 180 (54.5%) | 0.84 (0.68, 1.04) | |

| All-Cause mortality and/or hospitalization over 30 days ‡ | ||||

| Overall | 135 (10.1%) | 145 (11.1%) | 0.90 (0.71, 1.14) | |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | 0.25 | |||

| ≤ 40% | 93 (9.9%) | 88 (9.8%) | 1.02 (0.76, 1.36) | |

| 41–49% | 10 (12.3%) | 7 (10.0%) | 1.12 (0.43, 2.96) | |

| ≥ 50% | 32 (10.1%) | 50 (15.2%) | 0.66 (0.42, 1.03) | |

| All-Cause hospitalization over 12 months § | ||||

| Overall | 499 (37.4%) | 522 (40.1%) | 0.88 (0.78, 0.99) | |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | 0.22 | |||

| ≤ 40% | 341 (36.5%) | 340 (37.7%) | 0.92 (0.80, 1.07) | |

| 41–49% | 35 (43.2%) | 27 (38.6%) | 1.04 (0.63, 1.70) | |

| ≥ 50% | 123 (38.7%) | 155 (47.0%) | 0.74 (0.58, 0.93) | |

| Total hospitalizations over 12 months ∥ | ||||

| Overall | 892 | 896 | RR=0.95 (0.84, 1.08) | |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | 0.60 | |||

| ≤ 40% | 606 | 578 | RR=0.99 (0.85, 1.16) | |

| 41–49% | 53 | 49 | RR=0.90 (0.53, 1.55) | |

| ≥ 50% | 233 | 269 | RR=0.86 (0.67, 1.10) |

All-cause mortality includes verified deaths with confirmation from an acceptable obituary or grave marker, a second proxy confirming that the patient died, or an official medical record and deaths from the National Death Index (NDI) search or verified by the Mortality Review Committee.

Primary time to censoring: Patients randomized 2018–2021 and included in the NDI search are censored through the max of the Call Center last known alive date and 12/31/2021; patients not included in the NDI search or randomized in 2022 are censored through the Call Center last known alive date.

Hazard ratio (HR), 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value are based on a Cox proportional hazards regression model including the assigned treatment (torsemide vs. furosemide as the reference group) as well as age, sex, baseline ejection fraction (≤ 40%, 41–49%, ≥50%), and loop diuretic treatment prior to index hospital admission as covariates.

Hazard ratio (HR), 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value are based on a Fine and Gray competing risk (CR) model including the assigned treatment (torsemide vs. furosemide as the reference group) as well as age, sex, baseline ejection fraction (≤ 40%, 41–49%, ≥50%), and loop diuretic treatment prior to index hospital admission as covariates. In the competing risk model, subjects who did not have an event and died were considering competing risks (i.e., precludes the occurrence of the event of interest) and have a different censoring code from those who were alive at censoring.

Rate Ratio (RR), 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value are from a negative binomial regression (NBR) of the frequency of re-hospitalizations with an offset term of the log of each subject’s months to last rehospitalization assessment through month 12.

Figure 3.

Forest plot depicting hazard ratios (HR)/rate ratio (RR) of the treatment effect for all endpoints across the 3 left ventricular ejection fraction groups

Similarly, Figure 4 illustrates the treatment effect of torsemide vs furosemide visualized as a restricted cubic spline across the continuous LVEF spectrum. Approaching LVEF as a continuous variable in the interaction analysis confirmed the absence of statistical treatment effect modification by baseline LVEF, with potential exception of the composite of all-cause mortality or hospitalization endpoint (interaction P-value=0.048).

Figure 4. Hazard for the study clinical outcomes with torsemide vs furosemide across the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) spectrum.

Restricted cubic spline of (4-spline knot) spline of LVEF on the x axis and the result of Cox regression model expressed as hazard ratios (95% CI) on the y axis. All-cause mortality at 12 months (top left), all-cause mortality and/or all-cause hospitalization at 12 months (top right), all-cause mortality at 30 days (bottom left) and all-cause hospitalization at 12 months (bottom right). Line represents the point estimate for the HR and the shaded region the 95% confidence intervals.

KCCQ-CSS improved to a similar degree between baseline and 12 months of follow-up among patients receiving torsemide and furosemide (Table S3). There was no significant difference between torsemide and furosemide on change from baseline in KCCQ-CSS within any LVEF subgroup, although there was a nominally significant p for interaction (P=0.032).

Discussion

The main findings of this prespecified secondary analysis of TRANSFORM-HF are that (i) during the first year following a HF hospitalization there was a substantial risk for all-cause mortality and/or subsequent hospitalization, which was similar across LVEF subgroups, (ii) the treatment effect of torsemide vs furosemide on clinical outcomes did not differ across the LVEF spectrum, with potential exception of the composite endpoint of all-cause mortality or hospitalization, (iii) there was no significant difference between torsemide and furosemide on change in KCCQ-CSS from baseline to 12-months in any LVEF subgroup.

The finding reported herein that the risk of adverse outcomes, including all-cause mortality and all-cause hospitalization, was similar in patients with HFrEF, HFmrEF and HFpEF, even after adjusting for confounders, is in contrast to existing literature which primarily supports that patients with HFrEF have worse clinical outcomes.7,12,13 TRANSFORM-HF, owing to its pragmatic design and method for endpoint ascertainment, pre-specified the use of all-cause death and all-cause hospitalization, alone and in combination, as its endpoints.8 Previous HF studies have mainly focused on cardiovascular (CV) mortality and/or HF hospitalization and have shown that HFrEF is associated with an increased risk of these compared with HFpEF, which is, in part at least, counterbalanced by the proportionally lower risk of non-CV mortality and/or hospitalization.12 Thus, a different study design, focused on CV or HF-specific outcomes, may have produced higher incidence of events for patients with HFrEF. Moreover, HF is a heterogeneous clinical syndrome and the LVEF cut-offs and criteria used to define these groups have considerably changed over the last years.10,14,15 Thus, extrapolation of results from older epidemiological and outcomes study to the contemporary era may not be prudent. Additionally, study design (cohort study vs randomized controlled trial) and sponsor type (industry vs non-industry) are major determinants of the number and type of inclusion/exclusion criteria applied, patient population included and endpoints used, which may lead to selective reporting and/or non-generalizable findings.7,12,16 The enrollment of patients hospitalized with HF across 60 U.S. hospitals (i.e. large female and Black populations), the use of wide inclusion and few exclusion criteria (i.e. large comorbidity burden across LVEF spectrum), and the pragmatic design of TRANSFORM-HF provide confidence that these results are representative of the current HF landscape, at least inside the United States. In fact, analysis of almost 40,000 US patients hospitalized with HF in the Get With The Guidelines Heart Failure registry reported a 5-year mortality rate that was independent of LVEF.17

Although loop diuretics are recommended for relief of congestion and symptomatic improvement of congested patients with HF by contemporary practice guidelines,18,19 data on the effect of their use on hard clinical outcomes are sparse, dated, and/or of variable quality.20,21 Persistent congestion has been associated with adverse outcomes following a hospitalization for acute HF and has been presumed as a therapeutic target.22 Despite the theoretical superior features of torsemide (e.g. greater bioavailability, longer half-life, and anti-remodeling properties),3,4 the main findings of TRANSFORM-HF did not demonstrate any clinical benefit with use of torsemide over furosemide in terms of the trial’s clinical outcomes.5 The present analysis shows that the therapeutic equivalence of the two loop diuretics was consistent across the LVEF spectrum, irrespective of whether LVEF was analyzed as a categorical (HFrEF, HFmrEF, HFpEF) or continuous variable. The only potential exception regards the composite of all-cause mortality or hospitalization. However, we believe that this finding is likely a play of chance, and the borderline statistical significance should be interpreted in the context of clearly absent statistically interactions for all other clinical endpoints (including the components of this composite). Unfortunately, TRANSFORM-HF did not collect data on markers of (de)congestion; thus, hypotheses on the interaction of level of decongestion with clinical outcomes cannot be gleaned from this study. Nonetheless, several recent decongestion trials have failed to demonstrate a downstream improvement in outcomes with augmented, in-hospital diuresis and/or decongestion.23–26 The underappreciated significance of appropriate, outpatient loop diuretics dose selection and dose adjustments tailored to the patients’ volume status may be the missing piece explaining this paradox.27,28 In light of the above neutral effects on patient outcomes for torsemide versus furosemide, factors such as availability, tolerability and cost, are particularly important in shared decision-making with patients over the choice of a loop diuretic.

The improvement in KCCQ-CSS between baseline and 12-month follow-up did not differ significantly between the two treatment groups in the overall population,29 albeit an interaction with LVEF was noted. Improvement in CSS score was more pronounced with torsemide in HFmrEF, less pronounced in HFpEF and similar in HFrEF, though these differences did not reach statistical significance. Despite the distinct biological processes in HF across the LVEF spectrum, HFmrEF shares common features to both HFpEF and HFrEF, including response to HF treatment with HFrEF,7 thus rendering a mechanistic explanation of this finding challenging. We consider the most plausible explanation for this heterogeneity to be a play of chance, owing to the small proportion of patients with HFmrEF enrolled in the trial (~5%) and the lack of a clear biologic basis.

In TRANSFORM-HF KCCQ-CSS improved more in the HFrEF group (least square mean 31.9) compared with the HFmrEF (24.9) and HFpEF (25.8) groups between index hospitalization and 1-year follow-up (P<0.0001). Several explanations can be proposed for this finding. First, the baseline CSS of TRANSFORM-HF participants was impressively lower (mean 44 ± 23, median 42 [26,60]) than the respective score of participants in previous HF trials,30,31 reflecting their exclusive enrollment during the acute phase of a HF decompensation and the non-restrictive inclusion criteria of the trial. Lower baseline scores provide a greater opportunity for significant improvements of CSS during follow-up. Second, CSS has been shown to correlate with number of comorbidities in HF patients, irrespective of LVEF;31 in our population the comorbidity burden was considerably higher in patients with HFmrEF and HFpEF compared with patients with HFrEF. This was also the case with the prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease which has been associated with the lowest CSS scores.31 Additionally, HF hospitalizations are followed by more frequent initiation and dose increases of guideline-directed medical HF therapy among patients with HFrEF and HFmrEF,32,33 which have been shown to improve PROs in patients with HFrEF.34

Limitations

Our study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, this was a secondary (albeit prespecified) analysis of a neutral trial although the TRANSFORM-HF trial was powered to test the treatment effect of torsemide vs furosemide in the overall study cohort. Second, while the target event count was achieved in the main study, the sample size was approximately half that originally planned. Thus, this analysis, as all secondary analyses, may be limited by the more modest patient numbers. Third, echocardiographic assessment of LVEF is subject to variability, particularly when performed in local laboratories and over time (e.g. 24 months). However, lack of interaction even when LVEF was treated as a continuous variable increases our confidence in the validity of our results. Fourth, TRANSFORM-HF was an open-label study and knowledge of the assigned treatment may have affected PROs. This knowledge could have driven a “positive” effect of torsemide, yet this was not the case as no significant differences between the treatment groups were noted. Fifth, rates of missing data for PROs during follow-up were higher than in other recent HF trials and may bias toward neutral results. Sixth, loop diuretic dosing, discontinuation and cross-over during follow-up were at the treating physician’s discretion and may have influenced the results. Especially with regards to diuretic dosing at randomization, the preference of clinicians to use a 2:1 (rather than a 4:1) furosemide to torsemide conversion rate may have led to relative overdosing of torsemide,35 and may have influenced the results.

Conclusions

Despite baseline demographic and clinical differences between LVEF cohorts in TRANSFORM-HF and in contrast to previous observations, there seems to be a substantial risk for all-cause mortality and subsequent hospitalization in this population independent of baseline LVEF. PROs following an index HF hospitalization do not differ across LVEF groups, but improve more during follow-up in patients with HFrEF compared with those with HFmrEF and HFpEF. There were no significant differences in the clinical endpoints with torsemide vs furosemide following HF hospitalization across the LVEF spectrum.

Supplementary Material

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE.

- What is new?

- Despite demographic and clinical differences between heart failure patients with reduced vs mildly reduced vs preserved ejection fraction, all have a similar, substantial risk for all-cause mortality and/or re-hospitalization in the first year following a HF hospitalization.

- There is no significant difference in the incidence of mortality and/or hospitalization endpoints or changes in KCCQ-CSS with torsemide vs furosemide across the LVEF spectrum.

- What are the clinical implications?

- Our study provides insight in the contemporary clinical outcomes of a broad population of US patients following a HF hospitalization, stratified by LVEF.

- These data demonstrate that the outcomes of patients following a HF hospitalization are equally unfavorable, irrespective of their LVEF.

- There was no significant difference between torsemide and furosemide regarding clinical outcomes or change in KCCQ-CSS, with findings generally consistent across the LVEF spectrum.

- In light of their similar treatment effect across the LVEF spectrum, factors such as patient out-of-pocket cost, availability, and tolerability may be particular important in routine decisions of torsemide versus furosemide use.

Acknowledgments:

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI); the National Institutes of Health; or the US Department of Health and Human Services. The NHLBI had no role in the design of the study, but NHLBI staff did participate in the study conduct, collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data. The sponsor did not have the right to veto publication or control the decision regarding to which journal the article was submitted.

Sources of Funding:

TRANSFORM-HF was supported through cooperative agreements from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI; U01-HL125478 and U01-HL125511) and ancillary study grants from the NHLBI (R01HL148354-04 and R01HL154768-02).

Disclosures:

Dr Greene has received research support from the Duke University Department of Medicine Chair’s Research Award, American Heart Association (No. 929502), National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cytokinetics, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sanofi; has served on advisory boards for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim/Lilly, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cytokinetics, Roche Diagnostics, and Sanofi; serves as a consultant for Amgen, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim/Lilly, CSL Vifor, Merck, PharmaIN, Roche Diagnostics, Sanofi, Tricog Health, Urovant Pharmaceuticals; and has received speaker fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Cytokinetics, and Roche Diagnostics. Dr Anstrom has received research support from Merck, Bayer, Pfizer, National Institutes of Health, and PCORI. Dr Mentz receives research support and honoraria from Abbott, American Regent, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim/Eli Lilly, Boston Scientific, Cytokinetics, Fast BioMedical, Gilead, Innolife, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis, Pharmacosmos, Relypsa, Respicardia, Roche, Sanofi, Vifor, Windtree Therapeutics and Zoll. All other authors report no disclosures.

ABBREVIATION LIST

- CI

confidence interval

- CSS

clinical summary score

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- HF

heart failure

- HFmrEF

heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction

- HR

hazard ratio

- HFrEF

heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

- HFpEF

heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- KCCQ

Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- PROs

patient-reported outcomes

Footnotes

Registration: URL: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov; Unique identifier: NCT03296813.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental Tables S1, S2, S3

References

- 1.Kapelios CJ, Malliaras K, Kaldara E, Vakrou S, Nanas JN. Loop diuretics for chronic heart failure: A foe in disguise of a friend? Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2018;4:54–63. doi: 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvx020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vazir A, Kapelios CJ, Agaoglu E, Metra M, Lopatin Y, Seferovic P, Mullens W, Filippatos G, Rosano G, Coats AJS, et al. Decongestion Strategies in patients presenting with acutely decompensated heart failure: a worldwide survey among physicians. Eur J Heart Fail. 2023;25:1555–70. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buggey J, Mentz RJ, Pitt B, Eisenstein EL, Anstrom KJ, Velazquez EJ, O’Connor CM. A reappraisal of loop diuretic choice in heart failure patients. Am Heart J. 2015;169:323–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peters AE, Mentz RJ, DeWald TA, Greene SJ. An evaluation of torsemide in patients with heart failure and renal disease. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2022;20:5–11. doi: 10.1080/14779072.2022.2022474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mentz RJ, Anstrom KJ, Eisenstein EL, Sapp S, Greene SJ, Morgan S, Testani JM, Harrington AH, Sachdev V, Ketema F, et al. Effect of Torsemide vs Furosemide After Discharge on All-Cause Mortality in Patients Hospitalized With Heart Failure. JAMA. 2023;329:214–23. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.23924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tromp J, Westenbrink BD, Ouwerkerk W, van Veldhuisen DJ, Samani NJ, Ponikowski P, Metra M, Anker SD, Cleland JG, Dickstein K, et al. Identifying Pathophysiological Mechanisms in Heart Failure With Reduced Versus Preserved Ejection Fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:1081–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.06.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savarese G, Stolfo D, Sinagra G, Lund LH. Heart failure with mid-range or mildly reduced ejection fraction. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2022;19:100–16. doi: 10.1038/s41569-021-00605-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greene SJ, Velazquez EJ, Anstrom KJ, Eisenstein EL, Sapp S, Morgan S, Harding T, Sachdev V, Ketema F, Kim DY, et al. Pragmatic Design of Randomized Clinical Trials for Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2021;9:325–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2021.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spertus JA, Jones PG, Sandhu AT, Arnold SV. Interpreting the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire in Clinical Trials and Clinical Care. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:2379–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.09.542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bozkurt B, Coats AJ, Tsutsui H, Abdelhamid M, Adamopoulos S, Albert N, Anker SD, Atherton J, Böhm M, Butler J, et al. Universal Definition and Classification of Heart Failure. J Card Fail. 2021;27:387–413. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2021.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A Proportional Hazards Model for the Subdistribution of a Competing Risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446). doi: 10.2307/2670170 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shahim B, Kapelios CJ, Savarese G, Lund LH. Global Public Health Burden of Heart Failure: An Updated Review. Card Fail Rev. 2023;9:e11. doi: 10.15420/cfr.2023.05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kondo T, Dewan P, Anand IS, Desai AS, Packer M, Zile MR, Pfeffer MA, Solomon SD, Abraham WT, Shah SJ, et al. Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes in Patients With Heart Failure: Are There Thresholds and Inflection Points in Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction and Thresholds Justifying a Clinical Classification? Circulation. 2023;148:732–49. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.063642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rickenbacher P, Kaufmann BA, Maeder MT, Bernheim A, Goetschalckx K, Pfister O, Pfisterer M, Brunner-La Rocca HP; TIME-CHF Investigators. Heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction: a distinct clinical entity? Insights from the Trial of Intensified versus standard Medical therapy in Elderly patients with Congestive Heart Failure (TIME-CHF). Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:1586–96. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toth PP, Gauthier D. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: strategies for disease management and emerging therapeutic approaches. Postgrad Med. 2021;133:125–39. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2020.1842620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kapelios CJ, Naci H, Vardas PE, Mossialos E. Study design, result posting, and publication of late-stage cardiovascular trials. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2022;8:277–88. doi: 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcaa080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah KS, Xu H, Matsouaka RA, Bhatt DL, Heidenreich PA, Hernandez AF, Devore AD, Yancy CW, Fonarow GC. Heart Failure With Preserved, Borderline, and Reduced Ejection Fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70: 2476–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.08.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, Burri H, Butler J, Čelutkienė J, Chioncel O, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022;24:4–131. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Allen LA, Byun JJ, Colvin MM, Deswal A, Drazner MH, Dunlay SM, Evers LR. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: Executive Summary. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:1757–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faris RF, Flather M, Purcell H, Poole-Wilson PA, Coats AJS. Diuretics for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(2):CD003838. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003838.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kapelios CJ, Malliaras K, Nanas JN. Dosing of loop diuretics in chronic heart failure: it’s time for evidence. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18:1298. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chioncel O, Mebazaa A, Maggioni AP, Harjola VP, Rosano G, Laroche C, Piepoli MF, Crespo-Leiro MG, Lainscak M, Ponikowski P, et al. Acute heart failure congestion and perfusion status – impact of the clinical classification on in-hospital and long-term outcomes; insights from the ESC-EORP-HFA Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21:1338–52. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Felker GM, Mentz RJ, Cole RT, Adams KF, Egnaczyk GF, Fiuzat M, Patel CB, Echols M, Khouri MG, Tauras JM, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Tolvaptan in Patients Hospitalized With Acute Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:1399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mullens W, Dauw J, Martens P, Verbrugge FH, Nijst P, Meekers E, Tartaglia K, Chenot F, Moubayed S, Dierckx R, et al. Acetazolamide in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure with Volume Overload. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:1185–1195. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2203094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trullàs JC, Morales-Rull JL, Casado J, Carrera-Izquierdo M, Sánchez-Marteles M, Conde-Martel A, Dávila-Ramos MF, Llácer P, Salamanca-Bautista P, Pérez-Silvestre J, et al. Combining loop with thiazide diuretics for decompensated heart failure: the CLOROTIC trial. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:411–21. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.ter Maaten JM, Beldhuis IE, van der Meer P, Krikken JA, Postmus D, Coster JE, Nieuwland W, van Veldhuisen DJ, Voors AA, Damman K. Natriuresis-guided diuretic therapy in acute heart failure: a pragmatic randomized trial. Nat Med. 2023;29:2625–32. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02532-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kapelios CJ, Laroche C, Crespo‐Leiro MG, Anker SD, Coats AJS, Díaz-Molina B, Filippatos G, Lainscak M, Maggioni AP, McDonagh T, et al. Association between loop diuretic dose changes and outcomes in chronic heart failure: observations from the ESC‐EORP Heart Failure Long‐Term Registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22:1424–37. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kapelios CJ, Canepa M, Savarese G, Lund LH. Use of loop diuretics in chronic heart failure: do we adhere to the Hippocratian principle ‘do no harm’? Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23:1068–75. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greene SJ, Velazquez EJ, Anstrom KJ, Clare RM, DeWald TA, Psotka MA, Ambrosy AP, Stevens GR, Rommel JJ, Alexy T, et al. Effect of Torsemide Versus Furosemide on Symptoms and Quality of Life Among Patients Hospitalized for Heart Failure: The TRANSFORM-HF Randomized Clinical Trial. Circulation. 2023;148:124–34. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.064842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chandra A, Vaduganathan M, Lewis EF, Claggett BL, Rizkala AR, Wang W, Lefkowitz MP, Shi VC, Anand IS, Ge J,et al. Health-Related Quality of Life in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2019;7:862–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2019.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang M, Kondo T, Adamson C, Butt JH, Abraham WT, Desai AS, Jering KS, Køber L, Kosiborod MN, Packer M, et al. Impact of comorbidities on health status measured using the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire in patients with heart failure with reduced and preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2023;25:1606–18. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Srivastava PK, DeVore AD, Hellkamp AS, Thomas L, Albert NM, Butler J, Patterson JH, Spertus JA, Williams FB, Duffy CI, et al. Heart Failure Hospitalization and Guideline-Directed Prescribing Patterns Among Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction Patients. JACC Heart Fail. 2021;9:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2020.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schrage B, Lund LH, Benson L, Braunschweig F, Ferreira JP, Dahlström U, Metra M, Rosano GMC, Savarese G. Association between a hospitalization for heart failure and the initiation/discontinuation of guideline‐recommended treatments: An analysis from the Swedish Heart Failure Registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2023;25:1132–44. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greene SJ, Butler J, Hellkamp AS, Spertus JA, Vaduganathan M, Devore AD, Albert NM, Patterson JH, Thomas L, Williams FB, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Dosing of Medical Therapy for Heart Failure: From the CHAMP-HF Registry. J Card Fail. 2022;28:370–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2021.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vargo DL, Kramer WG, Black PK, Smith WB, Serpas T, Brater DC. Bioavailability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of torsemide and furosemide in patients with congestive heart failure. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1995;57:601–9. doi: 10.1016/0009-9236(95)90222-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.