Abstract

In vertebrates, DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) contributes to preserving DNA methylation patterns, ensuring the stability and heritability of epigenetic marks important for gene expression regulation and the maintenance of cellular identity. Previous structural studies have elucidated the catalytic mechanism of DNMT1 and its specific recognition of hemimethylated DNA. Here, using solution nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and small-angle X-ray scattering, we demonstrate that the N-terminal region of human DNMT1, while flexible, encompasses a conserved globular domain with a novel α-helical bundle-like fold. This work expands our understanding of the structure and dynamics of DNMT1 and provides a structural framework for future functional studies in relation with this new domain.

Keywords: DNMT1, DNA methylation, epigenetics, NMR spectroscopy, small-angle X-ray scattering, new protein domain fold

DNA methylation is a major epigenetic modification that regulates chromatin structure and various biological processes in mammals (1, 2, 3, 4). DNA methylation is carried out by four members of the DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) protein family, the best characterized of which is DNMT1. DNMT1 is a 1616-amino acid protein known to encompass a replication foci-targeting sequence (RFTS) domain, two bromo-adjacent-homology domains, and a C-terminal methyltransferase domain (Fig. 1A). While absent in lower species, DNMT1 is highly conserved in vertebrates, from Xenopus laevis to human.

Figure 1.

Identification of a folded segment at the N terminus of DNMT1.A, domain structure of human DNMT1 (hDNMT1). B, overlay of the 1H-15N HSQC spectra of DNMT1NL (aa 16–134, red) and DNMT1N (aa 16–93, cyan). C, R1, R2 and 15N-{1H} NOE for DNMT1N (cyan) and DNMT1NL (red) are plotted against their residues, with the corresponding secondary structure elements in DNMT1N shown. The R1 and R2 values were calculated using SPARKY 3.115 with errors determined via relaxation curve fitting. For 15N-{1H} NOEs, shown are the average values ± standard deviation calculated as explained in the Experimental procedures. D, 1H-15N resonance assignment for DNMT1N where side chain signals for asparagine and glutamine residues are indicated by horizontal lines. BAH, bromo-adjacent-homology; DNMT1, DNA methyltransferase 1; HSQC, heteronuclear single-quantum coherence; NOE, nuclear overhauser effect; RFTS, replication foci-targeting sequence.

DNA methylation by DNMTs predominantly targets palindromic CpG sites, showing a strong tendency to preferentially methylate CpG sites in a hemimethylated state, although asymmetric methylation at non-CpG sites has also been observed (5). Recent studies have revealed that the establishment and maintenance of DNA methylation involves all DNMTs to varying degrees, in conjunction with DNA demethylases, maintaining a dynamic equilibrium between methylation gain and loss (6). Consequently, knowledge of the DNMT structures is essential for elucidating the specific role played by each member in DNA methylation maintenance.

In the case of DNMT1, many structures containing the RFTS, bromo-adjacent-homology, and catalytic domains have been determined, shedding light on the mechanisms of methylation (7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17). These studies have deepened our understanding of the modes of action of DNMT1, particularly in relation to pathologic DNMT1 variants implicated in degenerative disorders of the nervous system (18, 19, 20, 21). All structural studies so far have exclusively focused on the segment from residue 350 to the C terminus of DNMT1. The N-terminal region of DNMT1 has received scant attention and has been described as disordered (12), even though limited resistance to proteolysis suggested that it might encompass folded segments (22). Here, using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), we identify a hitherto unreported folded domain within the N-terminal region of DNMT1.

Results

Identification of a folded domain at the N terminus of DNMT1

We initiated our studies using a recombinant DNMT1 fragment encompassing residues 16 to 134, selected based on predicted secondary structure elements (data not shown), and identified as DNMT1NL. The 1H-15N heteronuclear single-quantum coherence (HSQC) spectrum of DNMT1NL showed well dispersed signals overall, with some variations in signal intensities, indicating that there were structured as well as disordered regions within the protein (Fig. 1B). Further inspection of the 1H-15N relaxation data collected on DNMT1NL revealed that terminal segments comprising residues 16 to 21 and 94 to 134 were intrinsically disordered, with elevated R1 and decreased R2 15N relaxation rates and decreased steady-state 15N-{1H} heteronuclear overhauser effects (NOEs), compared to the rest of the protein (Fig. 1C). The rotational correlation time (τc) estimated from the average R1 and R2 values for DNMT1NL was 8.1 ± 2.2 ns, indicating that DNMT1NL is monomeric in solution. By truncating the residues in the C-terminal unstructured region, we produced a shorter version of DNMT1 (residues 16–93), denoted as DNMT1N (Fig. 1C). DNMT1N is also a monomer in solution based on its τc value of 5.4 ± 0.6 ns. Compared to the 1H-15N HSQC of DNMT1NL, the spectrum of DNMT1N showed better separation of signals and more homogeneous signal intensities (Fig. 1, B and D). We therefore used DNMT1N for subsequent structural studies.

The differences in Cα, Cβ, N, and HN chemical shift values between DNMT1N and DNMT1NL were mostly negligible, except for the C-terminus of DNMT1N near Glu93, as expected, and regions near Ser35 and Leu46-Gln54, where small chemical shift differences were observed in the overlaid 1H-15N HSQC spectra of DNMT1N and DNMT1NL (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, these regions harbor negatively charged residues. The detectable chemical shift perturbations might result from weak transient electrostatic interactions with the extended disordered region of DNMT1NL (aa 94–134).

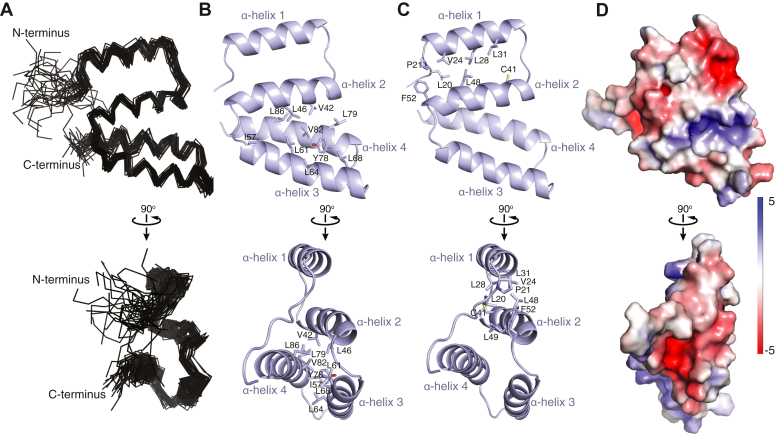

Solution NMR structure of DNMT1 N-terminal domain

The solution structure of DNMT1N was determined using multidimensional heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy with 937 NOE-based distance restraints, 132 dihedral angle restraints, and 47 1H-15N residual dipolar coupling (RDC) restraints for structure calculations (Fig. 2 and Table 1). The NMR structural ensemble of DNMT1N shows four α-helices (Fig. 2A). Three of these α-helices—α-helix 2 (aa 38–52), α-helix 3 (aa 55–71), and α-helix 4 (aa 76–91)—constitute a three-helix bundle, with each helix contacting the other two helices (Fig. 2B). Additionally, α-helix 2 contacts helix 1 (aa 22–34) (Fig. 2C). The plane containing α-helices 1 and 2 is almost perpendicular to the plane formed by α-helices 3 and 4 (Fig. 2, B and C). The structure of DNMT1N is stabilized by a hydrophobic core formed by the helical bundle and involves Val42 and Leu46 from α-helix 2; Ile57, Leu61, Leu64, and Leu68 from α-helix 3; and Tyr78, Leu79, Val82, and Leu86 from α-helix 4 (Fig. 2B). The contact surface between α-helices 1 and 2 is hydrophobic and involves Val24, Leu28, and Leu31 from α-helix 1 and Cys41, Leu48, Leu49, and Phe52 from α-helix 2 (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, Leu20, Pro21, Val24, Leu49, and Phe52 form another, smaller, hydrophobic cluster (Fig. 2C). Despite numerous hydrophobic contacts, all amide proton signals disappeared within 2 h in an NMR spectroscopy-monitored hydrogen-deuterium exchange experiment (data not shown). This observation suggests a low thermodynamic stability for the domain, related to a small unfolding free energy from the native state to the transient fully unfolded state (23). The electrostatic surface potential of DNMT1N (Fig. 2D) does not reveal any remarkable features that could offer clues to the function of this domain.

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional structure of DNMT1N.A, ensemble of the final 30 lowest-energy NMR structures of DNMT1N. B, DNMT1N structure in cartoon representation with residues at the interfaces of α-helices 2, 3, and 4 labeled and shown in stick representation. C, DNMT1N structure in cartoon representation with residues at the interface of α-helices 1 and 2 labeled and shown in stick representation. D, electrostatic surface potential of DNMT1N calculated using APBS in PyMOL. DNMT1, DNA methyltransferase 1; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance.

Table 1.

NMR and refinement statistics for DNMT1 (residues 16–93)

| NMR distance and dihedral constraints | |

| Distance constraints | |

| Total NOE | 937 |

| Intraresidue | 250 |

| Interresidue | 688 |

| Sequential (|i – j| = 1) | 288 |

| Medium range (|i – j| < 5) | 305 |

| Long range (|i – j| > 4) | 94 |

| Intermolecular | |

| Total dihedral angle restraints | 132 |

| φ | 66 |

| ψ | 66 |

| Total RDC restraints | 47 |

| Q factor | 0.16 |

| Structure statistics | |

| Violations (mean and s.d.) | |

| Distance constraints (Å) | 0.032 ± 0.002 |

| Dihedral angle constraints (°) | 0.132 ± 0.017 |

| Max. dihedral angle violation (°) | 4.613 |

| Max. distance constraint violation (Å) | 0.470 |

| Deviations from idealized geometry | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.005 ± 0.000 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.665 ± 0.008 |

| Impropers (°) | 0.516 ± 0.015 |

| Average pairwise r.m.s. deviationa (Å) | |

| Heavy | 1.51 ± 0.21 |

| Backbone | 0.70 ± 0.24 |

| Average r.m.s. deviation to mean structurea (Å) | |

| Heavy | 1.06 ± 0.13 |

| Backbone | 0.49 ± 0.18 |

| Ramachandran plot summary from Procheck (%) | |

| Most favored regions | 96.4 |

| Additionally allowed regions | 2.4 |

| Generously allowed regions | 1.1 |

| Disallowed regions | 0.1 |

DNMT1 (residues 22–90).

The RDC restrains were instrumental in refining and validating the relative orientations of the different regions of DNMT1N. Residues 55 to 90, which cover α-helices 3 and 4 in the structure, have uniformly negative RDC values except for the residues connecting these α-helices (Fig. 3, A and B). The RDC values for residues 16 to 54, corresponding to α-helices 1 and 2, are less uniform, indicating that α-helices 1 and 2 have different orientations from those of α-helices 3 and 4. There is excellent agreement between the experimentally measured and back-calculated RDCs (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Validation of the DNMT1Nstructure.A, representative 2D IPAP 1H-15N-HSQC spectra for DNMT1N from which RDCs were measured. Left, spectrum of isotropic DNMT1N sample. Right, spectrum of DNMT1N aligned in 5% C12E5/95% n-hexanol. B, experimentally measured backbone 1H-15N RDCs for DNMT1N. Secondary structure elements are shown on the top. C, comparison between experimental and back-calculated 1H-15N RDCs. For each back-calculated RDC, shown is the mean value ± standard deviation calculated from the 30 NMR structures. D, SAXS scattering data of DNMT1N. E, Guinier plot at low angles (q∗Rg <1.3) where Rg is the radius of gyration. F, Kratky plot (left) and Porod-Debye plot (right) showing a linear plateau (red line) agreeing with a globular protein with limited flexibility. G, pair distance distribution function showing a Dmax of ∼46.7 Å. H, left, DNMT1N NMR structure rigid-body-docked to the ab initio molecular envelope of DNMT1N generated using DAMMIF. Right, DNMT1N NMR structure docked to GASBOR bead model of DNMT1N. I, SAXS scattering curve back-calculated from the lowest energy NMR structure (red) overlaid to experimental scattering data (black). Goodness of fit χ2 is indicated. DNMT1, DNA methyltransferase 1; HSQC, heteronuclear single-quantum coherence; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance; RDC, residual dipolar coupling; SAXS, small-angle X-ray scattering.

SAXS analysis of DNMT1 N-terminal domain

We used SAXS (24, 25) to examine the global fold and oligomerization state of DNMT1N and thereby further evaluate the NMR-derived structure (Fig. 3D and Table S1). The SAXS Guinier plot (26) of DNMT1N was characteristic of a homogeneous sample (Fig. 3E). Furthermore, the Kratky and Porod-Debye plots (27) showed that the protein was globular with limited flexibility in the N and C termini (Fig. 3F). We derived a radius of gyration of ∼15.4 Å and a maximum dimension Dmax of ∼46.7 Å for DNMT1N, consistent with a monomeric state (Fig. 3G). The overall shape of DNMT1N was calculated by ab initio model reconstruction using GASBOR and DAMMIF from the ATSAS SAXS data analysis software package (28). GASBOR reconstructs the protein structure by a chain-like ensemble of dummy residues while DAMMIF does the reconstruction through assembly of densely packed spheres. Superposition of the NMR structure with the envelopes generated from DAMMIF and GASBOR showed good fit to both envelopes (Fig. 3H). Further evaluation using FoXS (29) demonstrated high consistency of the SAXS data with the DNMT1N NMR ensemble (Fig. 3I). The SAXS and NMR approaches indicate that DNMT1N is a monomer in solution.

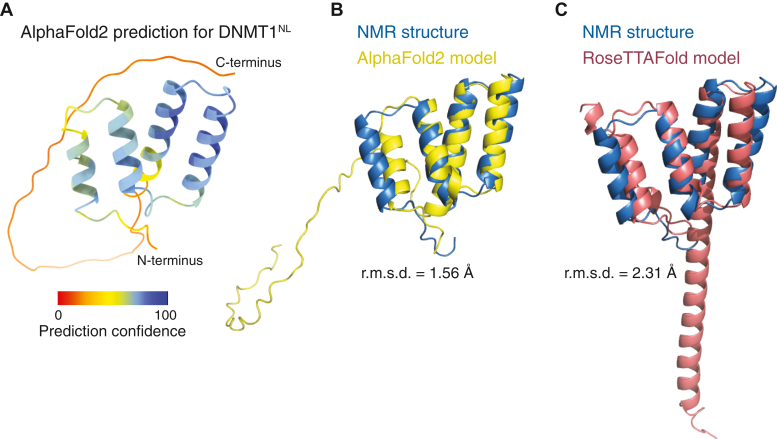

DNMT1N adopts a novel fold

A search using the DALI server against the Protein Data Bank and AlphaFold-predicted human proteome (30, 31, 32) identified an N-terminal motif in human DNMT1 that closely matches our DNMT1N NMR structure (Fig. 4A). The root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d.) between the lowest energy NMR structure and the predicted model was 1.56 Å for the backbone Cα, C, and N atoms of residues Glu22 to Leu90 (Fig. 4B). No other predicted protein structures exhibited a similar arrangement of four α-helices. Therefore, we conclude that DNMT1N adopts a novel fold. No other secondary structure elements were predicted beyond DNMT1N and before the RFTS domain. RoseTTAFold (33) also produced a structure comparable to that of DNMT1N (r.m.s.d. = 2.31 Å for the backbone Cα, C, and N atoms of residues Glu22 to Leu90), but with a 33-residue C-terminal helical extension to the fourth α-helix, not present in the experimental structure (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

DNMT1 structure prediction using AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold.A, cartoon representation of AlphaFold2-predicted human DNMT1NL structure color coded according to the per-residue confidence metric pLDDT. B and C, NMR structure of DNMT1N overlaid to models generated using AlphaFold2 (B) and RoseTTAFold (C). The r.m.s.d. values calculated for the backbone Cα, C, and N atoms of residues Glu22 to Leu90 are indicated. DNMT1, DNA methyltransferase 1; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance.

Discussion

We discovered a new folded domain of unknown function at the N terminus of DNMT1 (DNMT1N). Due to the chromatin association properties of DNMT1 (34), we investigated the binding of DNMT1NL to the nucleosome core particle, but no interaction was detected (data not shown). However, there are clues that DNMT1N has regulatory roles. Notably, it has been shown that through alternative RNA splicing of a sex-specific exon, DNMT1 from mammalian oocytes lacks a segment that matches DNMT1N and is sequestered in the cytoplasm (35). Moreover, there is evidence that DNMT1N interacts with the E-cadherin transcriptional repressor SNAIL1, with speculation that DNMT1 promotes gene expression by impeding the interaction of SNAIL1 with the E-cadherin promoter (36, 37). It has also been reported that DNMT1N interacts with DMAP1, a protein that preferentially activates DNMT1-mediated DNA methylation at sites of homologous recombination repair in response to DNA double-strand breaks (38, 39). In addition, deletion of DNMT1N in breast cancer cell lines was shown to diminish the histone deacetylase inhibitor LBH589-induced ubiquitylation-dependent degradation of DNMT1 and resulted in genomic hypermethylation (40). Consistently, an isoform of DNMT1 that lacks the N-terminal domain exhibited higher stability than full-length DNMT1 in vivo (41, 42). The underlying mechanism is unclear but likely involves cross-talks among several different post-translational modifications on DNMT1, such as methylation and acetylation. Intriguingly, Lys70 in DNMT1N was found to be methylated by protein methyltransferase G9a (43, 44). Whether or not this modification contributes to the regulation of DNMT1 level in cells has not been investigated.

In conclusion, because the structure of DNMT1N represents a novel fold, it cannot be used to suggest a possible function. However, based on what has been published so far, we can speculate that this helical domain is a protein-interaction module. The structure of DNMT1N will be helpful for the rational design of single-point mutations aimed at deciphering the function of this domain using cell biology approaches.

Experimental procedures

Protein expression and purification

The N-terminal domain of human DNMT1 (residues 16–134), denoted as DNMT1NL, was cloned with a tobacco etch virus protease cleavable N-terminal His6-tag in a pET15b-derived expression system. A shorter version (residues 16–93), denoted as DNMT1N, was made by inserting a stop codon (TAA) after Glu93. All proteins were produced in BL21(DE3) E. coli cells grown in M9 media prepared with 15N-labeled NH4Cl and unlabeled or 13C-enriched glucose. The cells were initially grown at 37 °C to an A600 of ∼0.5, then at 15 °C to an A600 of ∼0.6 before being induced with 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside for 16 h. The harvested cells were lysed using an EmulsiFlex C5 homogenizer (Avestin). The proteins were initially purified by Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose chelation chromatography (QIAGEN) using buffers of 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl with 5-, 20- and 200-mM imidazole for the binding, washing, and elution steps, respectively. The His6-tags were cleaved by overnight incubation with tobacco etch virus protease at 4 °C. The proteins were further purified by size-exclusion chromatography using a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75 column (Cytiva) and a running buffer of 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl.

NMR spectroscopy

All NMR experiments were performed at 25 °C using a Bruker Avance III 700 MHz spectrometer equipped with a triple-resonance cryoprobe. The NMR buffer for the 15N- and 15N-/13C-labeled DNMT1N and DNMT1NL protein samples was 20 mM MES/Bis-Tris, 50 mM NaCl, pH 6.0. The NMR spectra were processed with NMRPipe (45) and analyzed using SPARKY 3.115 (T. D. Goddard and D. G. Kneller, SPARKY 3, University of California, San Francisco). For resonance assignments, 13C,15N-labeled DNMT1N and DNMT1NL were used to collect a series of standard triple-resonance spectra including HNCO, HN(CA)CO, HNCA, HN(CO)CA, HNCACB, CBCA(CO)NH, HCCH-COSY, HCCH-TOCSY, and HBHA(CO)NH (46, 47, 48). We were able to assign 96.6% of the backbone and 78.3% of the sidechain carbon, proton, and nitrogen resonances.

The 15N NMR relaxation studies were carried out on both 15N-labeled DNMT1N and DNMT1NL. Longitudinal (R1) and transverse (R2) relaxation rates for backbone 1H-15N and 15N-{1H} steady-state NOEs were measured on these samples and analyzed using established methods (49, 50, 51). Ten relaxation delays (100, 300, 500, 600, 800, 1000, 1200, 1500, 1600, and 2000 ms) were used for R1, while 11 (4, 8, 16, 20, 28, 32, 40, 60, 80, 100, and 200 ms) were used for R2. The 15N-{1H} NOE ratios were obtained from a reference experiment without proton irradiation and a steady-state experiment with proton irradiation for 3 s. The standard deviations of 15N-{1H} NOEs were calculated based on the measured background noise levels, as previously reported (49), using Equation 1:

| (1) |

where Isat and Iunsat are the measured intensities of the resonances in the presence and absence of proton saturation, respectively. σIsat and σIunsat are the standard deviations of the noise in the spectra.

For structure determination of DNMT1N, distance restraints were obtained from the analysis of 3D 15N-edited NOESY HSQC spectra collected in 90%/10% H2O/D2O and 13C-edited NOESY HSQC spectra collected in 90%/10% H2O/D2O and in 100% D2O. The mixing time for these experiments was 160 ms. In total, 937 NOE-based distance restraints were used and categorized into seven bins with upper limits of 3.0, 3.5, 4.0, 4.5, 5.0, 5.5, and 6.0 Å. Also included in the structure calculations were 132 backbone dihedral angle φ and ψ restraints derived from the analysis of Hα, HN, 13Cα, 13Cβ, 13C, and 15N chemical shifts using TALOS+ (52) and 47 1H-15N RDC restraints out of 60 that were measured. The RDCs were measured in a 5% pentaethylene glycol monododecyl ether (C12E5)/95% n-hexanol mixture using 2D 1H-15N IPAP HSQC experiments (53, 54, 55). The RDC alignment tensor magnitude Da and rhombicity used in the structure calculations were −11.00 and 0.61, respectively. The structures were calculated and refined using XPLOR-NIH by employing a simulated annealing protocol for torsion angle dynamics (56, 57). A total of 200 structures were initially calculated, from which 30 structures with the lowest energies were used for further refinement.

A total of 60 measured RDCs, 47 of which were used for structure calculations, were compared to RDCs back-calculated from the 30 NMR structures using PALES (58), giving a Pearson’s linear correlation coefficient of 0.97. The quality factor Q factor (59), which evaluates the agreement between the RDCs back-calculated from the structures and the observed RDCs, was used as a figure of merit for the goodness of fit of the calculated structures to the experimental data. In Equation 2, Q is the quality factor; RMS stands for root mean square; Dcalc and Dobs are the back-calculated and measured residual dipolar couplings, respectively.

| (2) |

All molecular representations were generated using PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Schrödinger, LLC — https://pymol.org/2/). The electrostatic potential was calculated using APBS (60).

Small-angle X-ray scattering

The SAXS data were collected at the SIBYLS beamline 12.3.1, Advanced Light Source, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, on several DNMT1N samples (Table S1). For each sample, the scattering intensities were measured at three different protein concentrations (1, 2, and 3 mg/ml), demonstrating the absence of concentration dependence. Three different exposure times of 0.5, 1.0, and 5.0 s were used for each sample, and data were monitored for radiation damage-dependent aggregation. Scattering data were plotted as a function of q = 4π[sin(θ/2)]/λ, where θ is the scattering angle and λ is the X-ray wavelength, subtracting for each curve the scattering data collected for just the buffer alone. The curves were rescaled for the solute concentrations and extrapolated to infinite dilution. All data analyses were performed using PRIMUS, version 3.0, from ATSAS 2.4.2 (28). GNOM was used to generate the pair distance distribution function (P(r)) from which the maximum particle dimension (Dmax) was estimated. The radius of gyration (Rg) was estimated using the Guinier plot (61). Divergent low-q data points exhibiting artifacts from beam-stopper scattering and data points of q >0.25 Å−1 were not included in Guinier and P(r) analysis. The output of GNOM was used as input for DAMMIF to calculate the overall shape of DNMT1N. Twenty independent runs were conducted, and the generated models were averaged using DAMAVER to build a consensus molecular envelope. An ab initio envelope was also created using GASBOR as a comparison. SUPCOMB was used to superimpose the ab initio envelopes and NMR structures. The various software, including PRIMUS, GNOM, DAMMIF, DAMAVER, GASBOR, and SUPCOMB, were all from the ATSAS 2.4.2 program package (28).

AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold predictions

The DNMT1NL 3D structure predictions were performed using the AlphaFold2 Colab server (https://colab.research.google.com/github/sokrypton/ColabFold/blob/main/AlphaFold2.ipynb) and RoseTTAFold server (robetta.bakerlab.org).

Data availability

Coordinates for the NMR ensemble have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession number 8V9U. NMR chemical shift assignments have been deposited in the Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank with accession number 31134.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Chao Xu for insightful discussions and to Greg Hura at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Advanced Light Source (ALS) for assistance with SAXS data collection.

Author contributions

Q. H., M. V. B., and G. M. conceptualization; Q. H. and M. V. B. investigation; Q. H. writing–original draft; Q. H., M. V. B., and G. M. writing–review & editing; G. M. funding acquisition; G. M. supervision.

Funding and additional information

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R35 GM136262 to G. M. The SAXS data were collected at the ALS SIBYLS beamline, supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Biological Environmental Research, and by the NIH project ALS-ENABLE (P30 GM124169) and high-end instrumentation grant S10 OD018483. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Brian D. Strahl

Supporting information

References

- 1.Edwards J.R., Yarychkivska O., Boulard M., Bestor T.H. DNA methylation and DNA methyltransferases. Epigenet. Chromatin. 2017;10:23. doi: 10.1186/s13072-017-0130-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gowher H., Jeltsch A. Mammalian DNA methyltransferases: new discoveries and open questions. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2018;46:1191–1202. doi: 10.1042/BST20170574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim M., Costello J. DNA methylation: an epigenetic mark of cellular memory. Exp. Mol. Med. 2017;49 doi: 10.1038/emm.2017.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schubeler D. Function and information content of DNA methylation. Nature. 2015;517:321–326. doi: 10.1038/nature14192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He Y., Ecker J.R. Non-CG methylation in the human genome. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2015;16:55–77. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-090413-025437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeltsch A., Jurkowska R.Z. New concepts in DNA methylation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2014;39:310–318. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takeshita K., Suetake I., Yamashita E., Suga M., Narita H., Nakagawa A., et al. Structural insight into maintenance methylation by mouse DNA methyltransferase 1 (Dnmt1) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:9055–9059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019629108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song J., Rechkoblit O., Bestor T.H., Patel D.J. Structure of DNMT1-DNA complex reveals a role for autoinhibition in maintenance DNA methylation. Science. 2011;331:1036–1040. doi: 10.1126/science.1195380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Syeda F., Fagan R.L., Wean M., Avvakumov G.V., Walker J.R., Xue S., et al. The replication focus targeting sequence (RFTS) domain is a DNA-competitive inhibitor of Dnmt1. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:15344–15351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.209882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Z.M., Liu S., Lin K., Luo Y., Perry J.J., Wang Y., et al. Crystal structure of human DNA methyltransferase 1. J. Mol. Biol. 2015;427:2520–2531. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanada K., Takeshita K., Suetake I., Tajima S., Nakagawa A. Conserved threonine 1505 in the catalytic domain stabilizes mouse DNA methyltransferase 1. J. Biochem. 2017;162:271–278. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvx024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishiyama S., Nishiyama A., Saeki Y., Moritsugu K., Morimoto D., Yamaguchi L., et al. Structure of the Dnmt1 reader module complexed with a unique two-mono-ubiquitin mark on histone H3 reveals the basis for DNA methylation maintenance. Mol. Cell. 2017;68:350–360.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ye F., Kong X., Zhang H., Liu Y., Shao Z., Jin J., et al. Biochemical studies and molecular dynamic simulations reveal the molecular basis of conformational changes in DNA methyltransferase-1. ACS Chem. Biol. 2018;13:772–781. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.7b00890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li T., Wang L., Du Y., Xie S., Yang X., Lian F., et al. Structural and mechanistic insights into UHRF1-mediated DNMT1 activation in the maintenance DNA methylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:3218–3231. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ren W., Fan H., Grimm S.A., Guo Y., Kim J.J., Yin J., et al. Direct readout of heterochromatic H3K9me3 regulates DNMT1-mediated maintenance DNA methylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020;117:18439–18447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2009316117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ren W., Fan H., Grimm S.A., Kim J.J., Li L., Guo Y., et al. DNMT1 reads heterochromatic H4K20me3 to reinforce LINE-1 DNA methylation. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:2490. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22665-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kikuchi A., Onoda H., Yamaguchi K., Kori S., Matsuzawa S., Chiba Y., et al. Structural basis for activation of DNMT1. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:7130. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34779-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein C.J., Botuyan M.V., Wu Y., Ward C.J., Nicholson G.A., Hammans S., et al. Mutations in DNMT1 cause hereditary sensory neuropathy with dementia and hearing loss. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:595–600. doi: 10.1038/ng.830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winkelmann J., Lin L., Schormair B., Kornum B.R., Faraco J., Plazzi G., et al. Mutations in DNMT1 cause autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia, deafness and narcolepsy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21:2205–2210. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein C.J., Bird T., Ertekin-Taner N., Lincoln S., Hjorth R., Wu Y., et al. DNMT1 mutation hot spot causes varied phenotypes of HSAN1 with dementia and hearing loss. Neurology. 2013;80:824–828. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318284076d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baets J., Duan X., Wu Y., Smith G., Seeley W.W., Mademan I., et al. Defects of mutant DNMT1 are linked to a spectrum of neurological disorders. Brain. 2015;138:845–861. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suetake I., Hayata D., Tajima S. The amino-terminus of mouse DNA methyltransferase 1 forms an independent domain and binds to DNA with the sequence involving PCNA binding motif. J. Biochem. 2006;140:763–776. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvj210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bai Y., Sosnick T.R., Mayne L., Englander S.W. Protein folding intermediates: native-state hydrogen exchange. Science. 1995;269:192–197. doi: 10.1126/science.7618079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korasick D.A., Tanner J.J. Determination of protein oligomeric structure from small-angle X-ray scattering. Protein Sci. 2018;27:814–824. doi: 10.1002/pro.3376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grawert T.W., Svergun D.I. Structural modeling using solution small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) J. Mol. Biol. 2020;432:3078–3092. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2020.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Putnam C.D. Guinier peak analysis for visual and automated inspection of small-angle X-ray scattering data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2016;49:1412–1419. doi: 10.1107/S1600576716010906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rambo R.P., Tainer J.A. Characterizing flexible and intrinsically unstructured biological macromolecules by SAS using the Porod-Debye law. Biopolymers. 2011;95:559–571. doi: 10.1002/bip.21638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petoukhov M.V., Franke D., Shkumatov A.V., Tria G., Kikhney A.G., Gajda M., et al. New developments in the ATSAS program package for small-angle scattering data analysis. J. Appl. Cryst. 2012;45:342–350. doi: 10.1107/S0021889812007662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schneidman-Duhovny D., Hammel M., Sali A. FoXS: a web server for rapid computation and fitting of SAXS profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W540–W544. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holm L., Sander C. Dali: a network tool for protein structure comparison. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1995;20:478–480. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holm L., Laiho A., Toronen P., Salgado M. DALI shines a light on remote homologs: one hundred discoveries. Protein Sci. 2023;32 doi: 10.1002/pro.4519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jumper J., Evans R., Pritzel A., Green T., Figurnov M., Ronneberger O., et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021;596:583–589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baek M., DiMaio F., Anishchenko I., Dauparas J., Ovchinnikov S., Lee G.R., et al. Accurate prediction of protein structures and interactions using a three-track neural network. Science. 2021;373:871–876. doi: 10.1126/science.abj8754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schrader A., Gross T., Thalhammer V., Langst G. Characterization of Dnmt1 binding and DNA methylation on nucleosomes and nucleosomal arrays. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mertineit C., Yoder J.A., Taketo T., Laird D.W., Trasler J.M., Bestor T.H. Sex-specific exons control DNA methyltransferase in mammalian germ cells. Development. 1998;125:889–897. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.5.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Espada J., Peinado H., Lopez-Serra L., Setien F., Lopez-Serra P., Portela A., et al. Regulation of SNAIL1 and E-cadherin function by DNMT1 in a DNA methylation-independent context. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:9194–9205. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Espada J. Non-catalytic functions of DNMT1. Epigenetics. 2012;7:115–118. doi: 10.4161/epi.7.2.18756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rountree M.R., Bachman K.E., Baylin S.B. DNMT1 binds HDAC2 and a new co-repressor, DMAP1, to form a complex at replication foci. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:269–277. doi: 10.1038/77023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee G.E., Kim J.H., Taylor M., Muller M.T. DNA methyltransferase 1-associated protein (DMAP1) is a co-repressor that stimulates DNA methylation globally and locally at sites of double strand break repair. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:37630–37640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.148536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou Q., Agoston A.T., Atadja P., Nelson W.G., Davidson N.E. Inhibition of histone deacetylases promotes ubiquitin-dependent proteasomal degradation of DNA methyltransferase 1 in human breast cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 2008;6:873–883. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ding F., Chaillet J.R. In vivo stabilization of the Dnmt1 (cytosine-5)- methyltransferase protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:14861–14866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232565599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Agoston A.T., Argani P., Yegnasubramanian S., De Marzo A.M., Ansari-Lari M.A., Hicks J.L., et al. Increased protein stability causes DNA methyltransferase 1 dysregulation in breast cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:18302–18310. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501675200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang Y., Sun L., Kokura K., Horton J.R., Fukuda M., Espejo A., et al. MPP8 mediates the interactions between DNA methyltransferase Dnmt3a and H3K9 methyltransferase GLP/G9a. Nat. Commun. 2011;2:533. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rathert P., Dhayalan A., Murakami M., Zhang X., Tamas R., Jurkowska R., et al. Protein lysine methyltransferase G9a acts on non-histone targets. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:344–346. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G.W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ferentz A.E., Wagner G. NMR spectroscopy: a multifaceted approach to macromolecular structure. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2000;33:29–65. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500003589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mer G., Bochkarev A., Gupta R., Bochkareva E., Frappier L., Ingles C.J., et al. Structural basis for the recognition of DNA repair proteins UNG2, XPA, and RAD52 by replication factor RPA. Cell. 2000;103:449–456. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Botuyan M.V., Mer G., Yi G.S., Koth C.M., Case D.A., Edwards A.M., et al. Solution structure and dynamics of yeast elongin C in complex with a von Hippel-Lindau peptide. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;312:177–186. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Farrow N.A., Muhandiram R., Singer A.U., Pascal S.M., Kay C.M., Gish G., et al. Backbone dynamics of a free and phosphopeptide-complexed Src homology 2 domain studied by 15N NMR relaxation. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5984–6003. doi: 10.1021/bi00185a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dayie K.T., Wagner G., Lefèvre J.F. Theory and practice of nuclear spin relaxation in proteins. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1996;47:243–282. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.47.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mer G., Dejaegere A., Stote R., Kieffer B., Lefèvre J.-F. Structural dynamics of PMP-D2: an experimental and theoretical study. J. Phys. Chem. 1996;100:2667–2674. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shen Y., Delaglio F., Cornilescu G., Bax A. TALOS+: a hybrid method for predicting protein backbone torsion angles from NMR chemical shifts. J. Biomol. NMR. 2009;44:213–223. doi: 10.1007/s10858-009-9333-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tjandra N., Bax A. Direct measurement of distances and angles in biomolecules by NMR in a dilute liquid crystalline medium. Science. 1997;278:1111–1114. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5340.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rückert M., Otting G. Alignment of biological macromolecules in novel nonionic liquid crystalline media for NMR experiments. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:7793–7797. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yao L., Ying J., Bax A. Improved accuracy of 15N-1H scalar and residual dipolar couplings from gradient-enhanced IPAP-HSQC experiments on protonated proteins. J. Biomol. NMR. 2009;43:161–170. doi: 10.1007/s10858-009-9299-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schwieters C.D., Kuszewski J.J., Tjandra N., Clore G.M. The Xplor-NIH NMR molecular structure determination package. J. Magn. Reson. 2003;160:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(02)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schwieters C.D., Kuszewski J.J., Clore G.M. Using Xplor-NIH for NMR molecular structure determination. Progr. NMR Spec. 2006;48:47–62. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zweckstetter M. NMR: prediction of molecular alignment from structure using the PALES software. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:679–690. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cornilescu G., Marquardt J.L., Ottiger M., Bax A. Validation of protein structure from anisotropic carbonyl chemical shifts in a dilute liquid crystalline phase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:6836–6837. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jurrus E., Engel D., Star K., Monson K., Brandi J., Felberg L.E., et al. Improvements to the APBS biomolecular solvation software suite. Protein Sci. 2018;27:112–128. doi: 10.1002/pro.3280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guinier A., Fournet G. Small-Angle Scattering of X-Rays. John Wiley and Sons; New York, NY: 1955. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Coordinates for the NMR ensemble have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession number 8V9U. NMR chemical shift assignments have been deposited in the Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank with accession number 31134.