Abstract

Introduction and importance

Hepatic angiomyolipoma (HAML) is a rare liver tumor composed of blood vessels, smooth muscle, and fat cells. HAML occurs across a wide age range, with symptoms including abdominal discomfort, bloating, and weight loss. Diagnosis is challenging due to varied imaging appearances, but histopathological examination supplemented by immunohistochemical analysis, particularly using HMB-45, is definitive.

Case presentation

A 33-year-old man presented with a two-year history of right upper quadrant abdominal pain, occasionally relieved with analgesics but worsening over the past month and a half. Examinations revealed a soft, non-distended abdomen with a palpable liver. Laboratory tests, including viral markers and tumor markers were normal. Contrast-enhanced CT revealed a well-defined oval mass in liver segment III with heterogeneous enhancement leading to provisional diagnosis of HAML. The patient underwent a successful en bloc excision with no intraoperative or postoperative complications.

Clinical discussion

Surgical resection is recommended for symptomatic cases or inconclusive biopsies, with stringent follow-up necessary due to the potential for recurrence and association with other malignancies.

Conclusion

HAML may present with prolonged nonspecific abdominal symptoms. CT imaging aids in diagnosing cases with abundant fatty tissue. En bloc tumor excision proves safe and effective in treating symptomatic presentations.

Keywords: Hepatic angiomyolipoma, Mesenchymal liver tumor, Liver tumor

Highlights

-

•

Hepatic angiomyolipoma is a rare mesenchymal liver tumor which belongs to the family of perivascular epithelioid cell tumors.

-

•

The accuracy of preoperative diagnosis is notably low attributed to the varying proportions of its three components.

-

•

In patients with symptoms, uncertain diagnosis, or tumor growth, surgical resection should be performed.

1. Introduction

Hepatic angiomyolipoma (HAML) is an uncommon liver tumor, typically benign in nature, consisting mainly of blood vessels, smooth muscle, and fat cells [1]. Classified under the PECOMA category, this tumor is linked to a group arising from perivascular epithelioid cells (PEC). This category includes a range of tumors such as lymphangiomatosis in pulmonary and soft tissues, clear cell “sugar” tumors in pulmonary and pancreatic tissues, and rhabdomyoma in cardiac tissues [2].

The precise prevalence of HAML remains uncertain, but it's estimated that 300 to 600 cases have been reported till date worldwide [3]. These tumors have been noted across a wide age range, from early childhood to late adulthood, with a higher occurrence among females. Symptoms of HAML typically involve abdominal pain, discomfort, bloating, or weight loss [4]. In asymptomatic cases, the tumor may be incidentally detected through abdominal ultrasound or computed tomography conducted for unrelated reasons. Advances in imaging technologies have led to a growing number of diagnosed cases of HAML [5].

The reliability of preoperative diagnosis for HAML is notably limited due to the diverse imaging appearances resulting from the varying proportions of its constituent elements and the rarity of this condition. The definitive diagnostic method entails histopathological scrutiny of the tumor surgically removed, supported by immunohistochemical analysis, notably employing homatropine methylbromide-45 (HMB-45) [6]. This paper, following SCARE guidelines, details a unique case a 33-year-old male diagnosed with symptomatic HAML who underwent a successful en bloc excision with no intraoperative or postoperative complications [7].

2. Case presentation

A 33-year-old man presented with a two-year history of on-and-off dull abdominal pain in the right upper quadrant with radiation to the back occasionally, worsening over the past one and a half months and relieved with analgesics. The patient denied fever, vomiting, jaundice, itching, abdominal distension, or weight loss. Drug and family history were unremarkable. Vital signs were stable and examination revealed a soft, non-distended abdomen with a palpable liver. Laboratory tests were normal including negative for hepatitis B virus surface antigen and anti-hepatitis C virus antibody. Serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and carbohydrate antigen 19–1 (CA 19–9) levels were all within normal limits.

Contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) revealed a well-defined oval mass (13.6 × 3.9 × 10.6 cm) in segment III of liver exhibiting exophytic growth. The mass had heterogeneous attenuation with predominant macroscopic fat density (Fig. 1). Arterial phase enhancement was noted, supplied by the left hepatic artery. The mass compressed the gallbladder superiorly, abutted the ascending colon posteriorly, and impacted the duodenal loop and inferior vena cava posterolaterally, causing narrowing of the infrahepatic inferior vena cava. A preoperative diagnosis of hepatic angiomyolipoma was made. Intraoperatively a mass with dimensions of approximately 15 cm in diameter, originating from segment III of the liver, was identified. The mass exhibited well-defined borders and there was no peritoneal, pelvic, or liver metastases, nor any adhesions to adjacent structures. Subsequently, the patient underwent a successful en bloc excision of the tumor located in segment III without encountering any complications during the surgical procedure (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Contrast-enhanced CT scan arterial phase (left: axial section, right: coronal section) showing a mass in the inferior surface of the liver with heterogeneous density approximately 14 cm in diameter tumor.

Fig. 2.

Gross surgical specimen showing well-demarcated spherical mass measuring 15 cm in diameter.

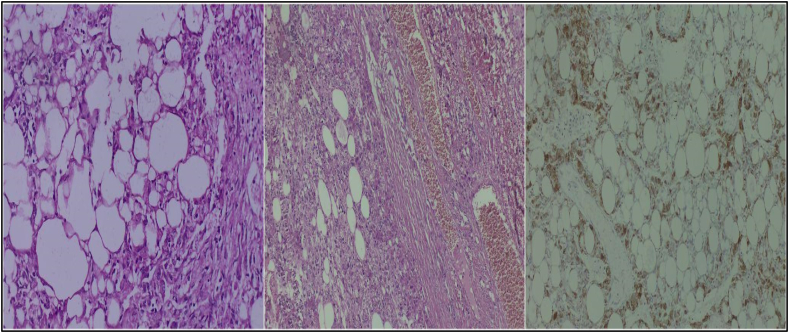

The histological analysis revealed dual composition, featuring mature adipose tissue arranged in sheets, accompanied by numerous thick-walled vessels and bundles of epithelioid cells. The immunohistochemical analysis confirmed positivity for HMB 45 (Fig. 3). No mitotic figures or atypia were identified. Final diagnosis of epithelioid angiomyolipoma was made. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged on the fifth postoperative day. The patient had no abdominal complaints and symptoms suggestive of recurrence at follow-up of 24 months.

Fig. 3.

Histopathology of hepatic angiomyolipoma; left (H&E): showing adipose tissue, middle (H&E): showing blood vessels and right (immunohistochemistry): showing positive staining for HMB 45.

3. Discussion

Angiomyolipomas (AML) commonly develop in the kidneys [2] [8]. Hepatic AMLs rank as the second most common location for their occurrence. Rare cases have been reported in a variety of other locations, including the retroperitoneum, mediastinum, nasopharyngeal cavity, buccal mucosa, hard palate, penis, vagina, fallopian tube, uterus, stomach, and spinal cord [9] [10] [11]. HAML most commonly occurs in the right hepatic lobe, while localization in the left lobe or caudate lobe is less common [12]. However, our case exhibited an uncommon occurrence, originating from the left lobe. HAML is frequently detected incidentally in individuals who do not display any symptoms, as its symptoms are generally vague, like mild abdominal discomfort or a feeling of fullness [13]. Nonomura et al. reported that 60 % of cases were asymptomatic, and among those with symptoms, common complaints included mild abdominal discomfort, enlargement of the liver, and a general sense of unwellness [14]. Likewise, our patient mentioned experiencing vague abdominal pain for a period of two years prior to diagnosis.

In a study conducted by Hu et al., involving 74 patients, only 23 % of those with hepatic angiomyolipoma could be accurately diagnosed before undergoing surgery [6]. Hepatic angiomyolipoma often presents a challenge in radiographic differentiation, especially when lacking a significant fatty component and not displaying characteristic features of angiomyolipoma, which can lead to confusion with solid tumors such as leiomyoma [12]. However, in our case, the mass showed strong enhancement and contained mostly fatty tissue, aiding in the preoperative diagnosis of hepatic angiomyolipoma, which was later confirmed by histopathology. Laboratory tests, including hepatitis viral markers, AFP, CEA and liver function tests, consistently yield negative results or provide non-specific and unhelpful information in establishing a diagnosis of HAML [15]. Immunohistochemical positivity for HMB-45, an antibody that responds to an antigen present in melanocytic tumors such as malignant melanoma, increases likelihood of AML [16].

Regarding the management of HAML, opting for a conservative approach might be considered reasonable following a histologically confirmed diagnosis, given its benign nature [17]. Surgical resection should be contemplated for patients experiencing symptoms, inconclusive biopsy results, or evidence of growth during follow-up, adhering to oncological criteria once the diagnosis of hepatic angiomyolipoma has been confidently established [3] [18]. Stringent follow-up is imperative, considering the likelihood of recurrences and the potential association with other malignant lesions [19] [20]. Surgical intervention was selected in our case due to persistent abdominal discomfort and the considerable size of the lesion, along with the potential risk of rupture, which could lead to a life-threatening complication.

4. Conclusion

HAML can present with nonspecific abdominal symptoms of long duration, and CECT imaging can help establish a preoperative diagnosis in cases where the fatty tissue is abundant. En bloc excision of the tumor is a safe and effective treatment strategy in symptomatic cases.

Ethical approval

Since this is a case report, our Institutional Review Board has waived the requirement for ethical approval.

Source of funding

No funding received.

Author's contribution

Conceptualization: Dr. Laxman Khadka, Dr. Prajjwol Luitel.

Patient Management: Dr. Laxman Khadka, Dr. Laligen Awale, Dr. Abhishek Bhattarai.

Writing – original draft: Dr. Laxman Khadka, Dr. Laligen Awale, Dr. Abhishek Bhattarai, Dr. Sujan Paudel, Dr. Prajjwol Luitel, Dr. Nischal Neupane.

Writing – review & editing: Dr. Laxman Khadka, Dr. Laligen Awale, Dr. Abhishek Bhattarai, Dr. Sujan Paudel, Dr. Prajjwol Luitel, Dr. Nischal Neupane.

Visualization and Supervision: Dr. Laxman Khadka, Dr. Laligen Awale, Dr. Abhishek Bhattarai.

Guarantor

Prajjwol Luitel.

Registration of research studies

-

1.

Name of the registry: None

-

2.

Unique identifying number or registration ID: None

-

3.

Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked): None

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Declaration

All the authors declare that the information provided here is accurate to the best of our knowledge.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

References

- 1.Ishak K.G. Mesenchymal tumors of the liver. Hepatocell. Carcinoma. 1976:247–307. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsui W.M., Colombari R., Portmann B.C., Bonetti F., Thung S.N., Ferrell L.D., et al. Hepatic angiomyolipoma: a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases and delineation of unusual morphologic variants. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1999 Jan;23(1):34–48. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199901000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klompenhouwer A.J., Verver D., Janki S., Bramer W.M., Doukas M., Dwarkasing R.S., et al. Management of hepatic angiomyolipoma: a systematic review. Liver Int. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Liver. 2017 Sep;37(9):1272–1280. doi: 10.1111/liv.13381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang X., Lei C., Qiu Y., Shen S., Lu C., Yan L., et al. Selecting a suitable surgical treatment for hepatic angiomyolipoma: a retrospective analysis of 92 cases. ANZ J. Surg. 2018 Sep;88(9):E664–E669. doi: 10.1111/ans.14323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakao T., Morimoto T., Mori K., Shimabara Y., Tanaka A., Yamaoka Y., et al. Two case reports of preoperatively diagnosed hepatic angiomyolipoma and review of 40 cases reported. J. Jpn. Pract. Surg. Soc. 1994;55(1):150–158. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu W.-G., Lai E.C.H., Liu H., Li A.-J., Zhou W.-P., Fu S.-Y., et al. Diagnostic difficulties and treatment strategy of hepatic angiomyolipoma. Asian J. Surg. 2011 Oct;34(4):158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sohrabi C., Mathew G., Maria N., Kerwan A., Franchi T., Agha R.A. The SCARE 2023 guideline: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2023 May;109(5):1136–1140. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamimura K., Nomoto M., Aoyagi Y. Hepatic angiomyolipoma: diagnostic findings and management. Int. J. Hepatol. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/410781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nonomura A., Enomoto Y., Takeda M., Tamura T., Kasai T., Yosikawa T., et al. Invasive growth of hepatic angiomyolipoma; a hitherto unreported ominous histological feature. Histopathology. 2006 Jun;48(7):831–835. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nonomura A., Minato H., Kurumaya H. Angiomyolipoma predominantly composed of smooth muscle cells: problems in histological diagnosis. Histopathology. 1998 Jul;33(1):20–27. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1998.00426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sturtz C.L., Dabbs D.J. Angiomyolipomas: the nature and expression of the HMB45 antigen. Mod. Pathol. Off. J. US Can. Acad. Pathol. Inc. 1994 Oct;7(8):842–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romano F., Franciosi C., Bovo G., Cesana G.C., Isella G., Colombo G., et al. Case report of a hepatic angiomyolipoma. Tumori J. [Internet] 2004 Jan 1;90(1):139–143. doi: 10.1177/030089160409000128. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang X., Li A., Wu M. Hepatic angiomyolipoma: clinical, imaging and pathological features in 178 cases. Med. Oncol. 2013 Mar;30(1):416. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0416-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nonomura A., Mizukami Y., Kadoya M. Angiomyolipoma of the liver: a collective review. J. Gastroenterol. 1994 Feb;29(1):95–105. doi: 10.1007/BF01229084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu A.-M., Zhang S.-H., Zheng J.-M., Zheng W.-Q., Wu M.-C. Pathological and molecular analysis of sporadic hepatic angiomyolipoma. Hum. Pathol. 2006 Jun;37(6):735–741. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Makhlouf H.R., Ishak K.G., Shekar R., Sesterhenn I.A., Young D.Y., Fanburg-Smith J.C. Melanoma markers in angiomyolipoma of the liver and kidney: a comparative study. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2002 Jan;126(1):49–55. doi: 10.5858/2002-126-0049-MMIAOT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nonomura A., Mizukami Y., Kadoya M., Matsui O., Shimizu K., Izumi R. Angiomyolipoma of the liver: its clinical and pathological diversity. J. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Surg. [Internet] 1996;3(2):122–132. doi: 10.1007/BF02350921. Available from: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petrolla A.A., Xin W. Hepatic angiomyolipoma. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. [Internet] 2008 Oct 1;132(10):1679–1682. doi: 10.5858/2008-132-1679-HA. Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Croquet V., Pilette C., Aubé C., Bouju B., Oberti F., Cervi C., et al. Late recurrence of a hepatic angiomyolipoma. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2000 May;12(5):579–582. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200012050-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang Y.C., Tsai H.M., Chow N.H. Hepatic angiomyolipoma with concomitant hepatocellular carcinomas. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48(37):253–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]