Abstract

A subset of patients with post-COVID-19 condition (PCC) fulfill the clinical criteria of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). To establish the diagnosis of ME/CFS for clinical and research purposes, comprehensive scores have to be evaluated. We developed the Munich Berlin Symptom Questionnaires (MBSQs) and supplementary scoring sheets (SSSs) to allow for a rapid evaluation of common ME/CFS case definitions. The MBSQs were applied to young patients with chronic fatigue and post-exertional malaise (PEM) who presented to the MRI Chronic Fatigue Center for Young People (MCFC). Trials were retrospectively registered (NCT05778006, NCT05638724). Using the MBSQs and SSSs, we report on ten patients aged 11 to 25 years diagnosed with ME/CFS after asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection or mild to moderate COVID-19. Results from their MBSQs and from well-established patient-reported outcome measures indicated severe impairments of daily activities and health-related quality of life.

Conclusions: ME/CFS can follow SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients younger than 18 years, rendering structured diagnostic approaches most relevant for pediatric PCC clinics. The MBSQs and SSSs represent novel diagnostic tools that can facilitate the diagnosis of ME/CFS in children, adolescents, and adults with PCC and other post-infection or post-vaccination syndromes.

|

What is Known: • ME/CFS is a debilitating disease with increasing prevalence due to COVID-19. For diagnosis, a differential diagnostic workup is required, including the evaluation of clinical ME/CFS criteria. • ME/CFS after COVID-19 has been reported in adults but not in pediatric patients younger than 19 years. | |

|

What is New: • We present the novel Munich Berlin Symptom Questionnaires (MBSQs) as diagnostic tools to assess common ME/CFS case definitions in pediatric and adult patients with post-COVID-19 condition and beyond. • Using the MBSQs, we diagnosed ten patients aged 11 to 25 years with ME/CFS after asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection or mild to moderate COVID-19. |

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00431-023-05351-z.

Keywords: Children, Adolescents, ME/CFS, Post-COVID, SARS-CoV-2, Post-exertional malaise

Introduction

The corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has caused a global healthcare crisis. Besides immediate risks from severe acute respiratory coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infections [1, 2], post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) are adding to the post-pandemic burden, straining healthcare and societies [3–7].

While many patients recover from PASC within few months, some endure a long lasting disorder, affecting social participation and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [4, 8–10]. The World Health Organization (WHO) defined a post-COVID-19 condition (PCC) (ICD-10 U09.9!) as persistent or new symptoms 3 months after the initial SARS-CoV-2 infection (children: within 3 months), lasting over 2 months, and not explained otherwise [11, 12].

PASC affects at least 65 million individuals worldwide, with a population-based prevalence of about 10% of infected people and a lower prevalence in children [4, 13]. Estimating pediatric PCC prevalence is challenging [8, 14], with 0.8 to 13% reported in controlled cohorts [15, 16] and 2.0 to 3.5% calculated in a meta-analysis covering initially non-hospitalized, infected children and adolescents [17].

PASC/PCC may manifest with a wide variety of symptoms, including fatigue, shortness of breath, cognitive dysfunction, pain, sleep disorder, and/or mood symptoms. These symptoms can persist, fluctuate, or relapse and may have a significant impact on everyday functioning [11, 12, 18–20]. Some patients suffer from exertion intolerance with a worsening of symptoms after mild physical and/or mental activities, known as post-exertional malaise (PEM) [21, 22]. PEM can last for days or weeks and is recognized as a cardinal symptom of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) [23, 24]. ME/CFS following COVID-19 has been reported in adults [21, 25, 26] and in a 19-year-old male from the USA [27, 28] but, to our knowledge, not yet in younger patients. However, overlapping symptoms of PASC and ME/CFS have been described in pediatric patients [29].

ME/CFS is classified as a complex, chronic neurological disorder (ICD-10-GM G93.3 (Germany) or ICD-10-CM G93.32 (USA)), triggered mostly by infections [30–32]. Core symptoms include reduced daily functioning with fatigue not alleviated by rest, PEM usually lasting more than a day, unrefreshing sleep, neurocognitive deficits (“brain fog”) and/or orthostatic intolerance (OI), with additional symptoms in most cases [33]. Hypothesized pathogenic mechanisms of PCC and ME/CFS overlap, including viral persistence, latent virus reactivation, inflammation, autoimmunity, endothelial dysfunction, and microbiome dysbiosis [23, 34]. Common risk factors of PCC and ME/CFS are female gender, late adolescence or early adulthood, as well as pre-existing chronic health issues [14, 21, 31, 35, 36].

Population-based, pre-pandemic estimates of ME/CFS prevalence ranged from 0.1 to 0.89% in adults [37–40] and from 0.75 to 0.98% in adolescents and children [41, 42], with a high number of undetected cases [42]. Current estimates predicted at least a doubling of ME/CFS cases due to severe PCC [21, 27, 34, 43, 44].

Given the absence of a diagnostic ME/CFS biomarker, comprehensive evaluation is essential for complex disorders with chronic fatigue. Clinical criteria like the Canadian consensus criteria (CCC) [45] and the broader criteria by the former Institute of Medicine (IOM) [46] are widely used. For children and adolescents, the CCC were adapted by a “pediatric case definition” of L.A. Jason and colleagues (PCD-J) [47] and by the “clinical diagnostic worksheet” designed by P.C. Rowe and colleagues (CDW-R) [48]. A symptom duration of at least 6 months is usually required for adult patients [31], but was suggested to be reduced cross-age to facilitate early treatment [49]. For children and adolescents, the disease duration required by the CCC, the IOM criteria, and the PCD-J is 3 months [45–47].

ME/CFS care requires a holistic, longitudinal approach, including extensive patient education, the palliation of symptoms, and adequate psychosocial support. Patients must be carefully guided in “pacing” strategies to avoid PEM (“crashes”) [49].

Early identification of ME/CFS patients is important to prevent mismanagement and mitigate secondary harm, including disease deterioration and suicidality. Adequate care can lead to substantial improvement, particularly in young patients, often recovering within a decade [32]. However, recovery doesn’t imply absence of functional impairment [50]. Limited ME/CFS-specific awareness among healthcare providers [51–53], coupled with rising prevalence, increases the risk of inadequate care and secondary issues.

A challenge in clinical care and research for ME/CFS is the use of various diagnostic criteria and the lack of specific symptoms. To increase diagnostic sensitivity, the frequency and severity of symptoms should be assessed [54, 55].

The Munich Berlin Symptom Questionnaires (MBSQs) aim to facilitate the diagnostic approach across age goups with chronic fatigue following COVID-19 and beyond. They represent novel tools for an age-adapted, standardized evaluation of the most common clinical ME/CFS case definitions in clinical and research settings.

We introduce bilingual MBSQ versions and present results from the first ten PCC patients diagnosed with ME/CFS using the MBSQs in structured interviews at our MRI Chronic Fatigue Center For Young People (MCFC). Our Post-COVID clinic is part of the “Post-COVID Kids Bavaria” project, providing pediatric care and research for severe COVID-19 sequelae [56].

Patients and methods

Inclusion criteria and clinical assessment

Ten patients were diagnosed at the MCFC with PCC and ME/CFS using the German versions (can be requested from the authors) of the novel MBSQs and the supplementary scoring sheets (SSSs) (Supplementary information) (see description below). The collection and publication of medical data was approved by the TUM Ethics Committee (116/21, 511/21). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants (or parents) prior to inclusion. All patients had a history of confirmed (positive reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)) or probable (anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG with a history of typical COVID-19 symptoms and without prior COVID-19 vaccination) SARS-CoV-2 infection and with post-viral symptoms lasting for more than 3 months.

Before visiting the MCFC, the patients completed various questionnaires in a stepped routine process, including well-established patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) to assess fatigue (Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) [57] or Chalder Fatigue Scale (CFQ) [58]), PEM (DePaul Symptom Questionnaire-PEM (DSQ-PEM)) [24], limitations in daily functioning (Bell Score) [59], HRQoL during the last 4 weeks (Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36)) [60], and the MBSQ.

Significant fatigue was indicated by a mean score of ≥ 5 (maximum: 7) in the FSS [61] or of ≥ 4 (maximum: 11) in the CFQ bimodal score [62]. The DSQ-PEM provides a Likert scale for the frequency (0–4) and severity (0–4) of five different PEM-related symptoms and evaluates the duration of PEM [24]. The Bell Score measures daily functioning on a scale from 0 to 100%, with 100% representing normal daily functioning [59]. The SF-36 consists of eight dimensions, including physical functioning, social functioning, vitality, general health, mental health, role physical, role emotional, and bodily pain. The score of each dimension is scaled to 0–100, with 0 representing the worst and 100 the best health status.

At the MCFC laboratory, technical tests were conducted to rule out other potential causes explaining the patients’ symptoms. Analyses varied based on symptoms, with core routine tests following prior recommendations [48]. Routine blood analyses included a differential cell count as well as C-reactive protein, liver, kidney, and thyroid function parameters, HbA1c, total serum immunoglobulins, antinuclear antibodies, antibodies against thyroid peroxidase, morning cortisol, antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and EBV DNA load in blood and/or throat washes, supplemented by analyses of urine and stool (calprotectin, blood). Routine technical investigations included pulmonary function testing (PFT), electrocardiography, and ultrasound cardiography. If indicated, electroencephalography (EEG), cardiac or brain magnetic resonance tomography (MRT), ophthalmological, rheumatological, and/or other assessments were added.

In general, patients were jointly assessed by a pediatrician and psychologist or child and adolescent psychiatrist, specialized in ME/CFS. Alternatively, psychological evaluation was performed externally and reports discussed internally. All patients underwent a 10-min passive standing test to evaluate OI, including PoTS or orthostatic hypotension (OH) [63, 64]. The average HR while supine (5 min) was defined as baseline, and PoTS was defined by a sustained HR ≥ 120 beats per minute (bpm) and/or a sustained increase by HR ≥ 40 bpm for individuals ≤ 19 years and ≥ 30 bpm for individuals > 19 years in an upright posture (10 min), together with a history of orthostatic symptoms for at least 3 months [65, 66].

Clinical ME/CFS criteria were assessed through semi-structured interviews. MCFC physicians reviewed pre-filled MBSQs with patients (and parents) to prevent misunderstanding about symptoms and PEM duration. Home pre-filling saved time and let physicians focus on clarifications. ME/CFS diagnosis required at least one matched case definition and no other explanation of symptoms. An interdisciplinary ME/CFS board discussed each case involving experienced physicians.

Development of the Munich Berlin Symptom Questionnaire

The MBSQ evaluates IOM and CCC criteria, which were recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [67] and the European Network for ME/CFS (EUROMENE) and require at least 6 months disease duration for adults (≥ 18 years) [31]. A separate version for children and adolescents (≤ 18 years) contains additional questions to assess the PCD-J and CDW-R criteria. For practicality, the pediatric MBSQ requires 3 months, though CDW-R advised preliminary diagnosis at 3 months and confirmed at six [48] (Table 1).

Table 1.

MBSQ versions for different age groups

| Version |

Adressed period of symptoms |

Age group | CCC | IOM | PCD-J | CDW-R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children and Adolescents | Past 3 months | 0–17 years | + | + | + | + |

| Adults | Past 6 months | ≥ 18 years | + | + | − | − |

For developing the MBSQs, all terms used to describe the symptoms in the original publications [45–48] were mapped to the eight CCC symptom categories (fatigue, PEM, sleep disorder, pain, neurocognitive, autonomic, neuroendocrine, and immunologic manifestations). Overlaps and differences were identified, and umbrella terms introduced if neccessary. We aimed at the best match of all terms with terms in the original publications and adapted the wording, if necessary, during several rounds of clinical testing and discussion to optimize the understanding by patients and/or parents. The wording was not further adapted for children. The MBSQ was neither designed nor evaluated as a PROM and therefore is not recommended for use as such. The MBSQs are meant to aid a structured medical interview. This should exclude misunderstandings and may result in an adaptation of answers, if necessary. English versions are provided in the Supplementary information and German versions upon request from the authors.

We used a 5-point Likert scale for quantifying the frequency and severity of symptoms [54, 55]. In line with the DSQs, the MBSQs require an at least moderate frequency and severity (≥ 2) to support the ME/CFS diagnosis. Four additional dichotomous questions for the presence or absence of distinct features of fatigue or neurocognitive manifestations were included and three further questions for the prominent triggers of PEM, the main symptoms of PEM, and the most bothering symptoms of ME/CFS. In contrast to the DSQ-2 [55], the MBSQ focuses on ME/CFS symptoms only, omitting any further evaluation of medical history.

Results

We developed the MBSQs and SSSs in German and English as novel tools for the clinical assessment of ME/CFS in the context of PCC and beyond. They address the most commonly recommended ME/CFS case definitions (CCC, IOM) and, in the versions for children and adolescents, two additional pediatric case definitions (CDW-R, PCD-J) (Table 1) to facilitate semi-structured, age-adapted approaches to diagnosis.

Here, we applied the MBSQs to patients with PCC and report on the first ten patients diagnosed with ME/CFS after a thorough diagnostic workup (Tables 1 and 2, Figs. 1 and 2). Patients included an 11-year-old child, three adolescents (13 to 15 years), and six young adults (18 to 25 years). Three were males and seven females. At diagnosis, symptoms lasted 4 to 16 months (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical data of patients with MECFS following SARS-CoV-2 infection

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | M | M | F | M | F | F | F | F | F | F | |

| Age range (years) | 11–15 | 18–25 | |||||||||

| COVID-19 | Loss of smell/taste | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | + |

| RT-PCR | + | + | n. d. | + | + | + | + | n. d. | + | + | |

| Antibodiesa | + | + | + | n. d. | + | + | n. d. | + | n. d. | + | |

| Medical care | Non-hospitalized | Non-hospitalized | Non-hospitalized | Non-hospitalized | Non-hospitalized | Hospitalized | Non-hospitalized | Non-hospitalized | Non-hospitalized | Non-hospitalized | |

| Latency period from infection to medical evaluation (months) | 10 | 14 | 16 | 4 | 10 | 10 | 13 | 14 | 11 | 9 | |

| Post-COVID |

Main symptoms as prioritized by the patient |

1. Dizziness | 1. Concentration problems | 1. Fatigue | 1. Headaches | 1. Concentration problems | 1. Brain fog | 1. Pain | 1. Fatigue | 1. Fatigue | 1. Breathing problems |

| 2. Tiredness | 2. Dizziness | 2. PEM | 2. Concentration problems | 2. Fatigue | 2. Headaches | 2. Fatigue | 2. Pain | 2. Flu-like feeling | 2. Malaise with mild fever | ||

| 3. Pain | 3. Thermostatic instability | 3. Neurocognitive manifestations | 3. Dizziness | 3. Headaches/ dizziness | 3. PEM | 3. Neurocognitive manifestations | 3. Dizziness | 3. PEM | 3. Fatigue/ tiredness | ||

| OI/PoTS/OH | OI | PoTS | OI | PoTS | OI | PoTS | PoTS | OI | - | PoTS | |

| PROMs | Bell Scoreb | 50–60 | 20 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 20–30 | 30 | 60 | 50 | 40–50 |

| FSSc | 5.6 | 6.3 | 6.6 | 6.6 | 7.0 | 6.9 | 6.6 | n. d | 6.0 | 6.8 | |

| CFQd | n. d. | n. d. | n. d. | n. d. | n. d. | n. d. | n. d. | 11 | n. d. | n. d. | |

| DSQ-PEM | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| MBSQs | CCC | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| IOM | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | |

| PCD-J | − | − | + | + | n. d. | n. d. | n. d. | n. d. | n. d. | n. d. | |

| CDW-R | + | + | + | + | n. d. | n. d. | n. d. | n. d. | n. d. | n. d. | |

| PEM duration (hours) | > 24 | > 24 | > 24 | > 24 | > 24 | > 24 | > 24 | > 24 | > 24 | > 24 | |

M male, F female, RT-PCR reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, n. d. not done, PEM post-exertional malaise, PoTS postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, OI orthostatic intolerance, OH orthostatic hypotension, PROMs patient-reported outcome measures, FSS Fatigue Severity Scale, mean score, CFQ Chalder Fatigue Scale, bimodal score, DSQ-PEM DePaul Symptom Questionnaire-Post-Exertional Malaise, MBSQs Munich Berlin Symptom Questionnaires, CCC Canadian Consensus Criteria [45], IOM Criteria of the former Institute of Medicine [46], PCD-J Pediatric Case Definition by Jason et al. [47], CDW-R Clinical Diagnostic Worksheet by Rowe et al. [48], h hours

aanti-SARS-CoV-2 spike antibodies before vaccination and/or anti-SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid antibodies

bBell Score (%) (0% = entirely bedridden; 100% = normal daily functioning)

cFSS (maximum value: 7)

dCFQ (maximum value: 11)

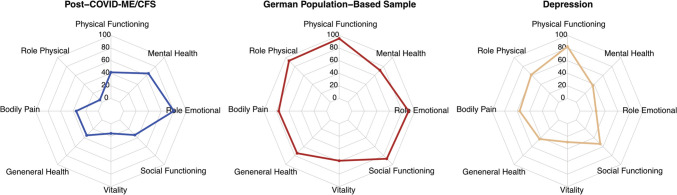

Fig. 1.

Results from the Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36). Spider diagrams display the different dimensions of the Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36) for the ten MCFC patients with ME/CFS following COVID-19 (Post-COVID-ME/CFS), the German norm population (age 14–20 years) from 1998 [68], and patients with moderate to severe depression (n = 60, mean age 17.5 ± 1.6 years) [70]

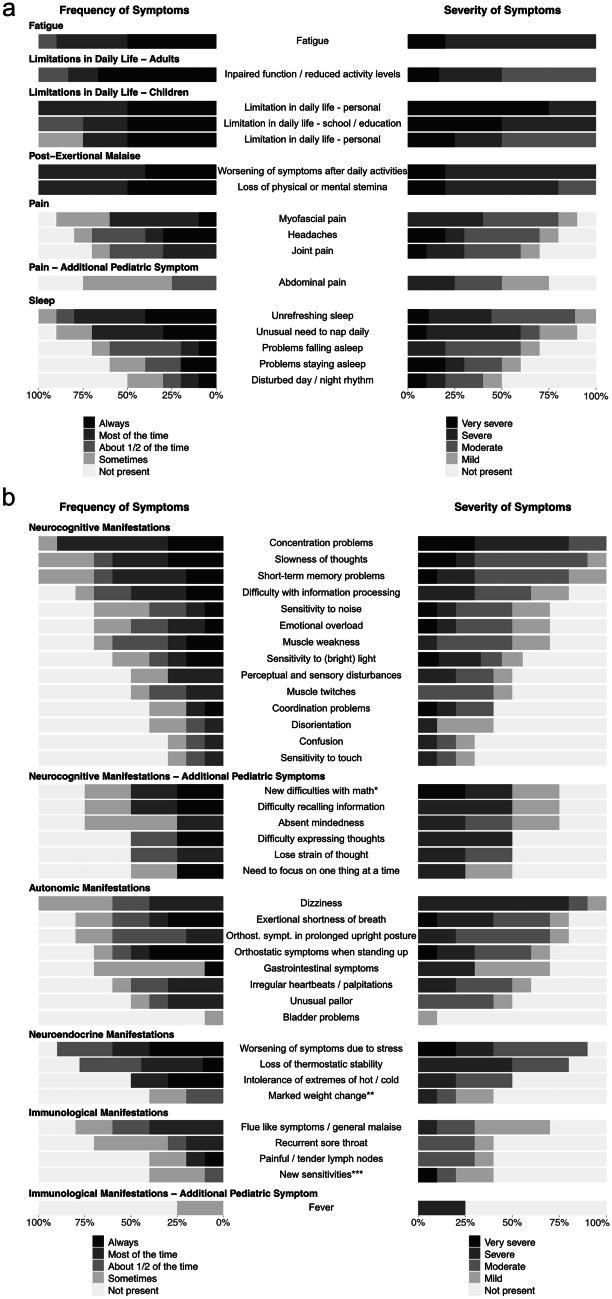

Fig. 2.

Frequency and severity of symptoms. a Stacked bar charts represent the frequency and severity of symptoms as indicated on the first page of the Munich Berlin Symptom Questionnaires (MBSQs). Symptoms that are assessed differently in pediatric (n = 4) and adult patients (n = 6) are presented separately, as indicated. b Stacked bar charts display the frequency and severity of symptoms from the second page of the Munich Berlin Symptom Questionnaires (MBSQs). Symptoms that are assessed differently in pediatric (n = 4) and adult patients (n = 6) are presented separately, as indicated. *New difficulties with math or other educational subject; **Marked weight change and/or loss of appetite and/or abnormal appetite; ***New sensitivities to food, medication or chemicals

Nine of ten patients were diagnosed with confirmed or probable COVID-19, and one with asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection from March 2020 to January 2022. Eight patients provided positive SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR results, and two showed SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies with a history of COVID-19-like symptoms and no prior vaccination. One adult was hospitalized for a pre-syncopal episode in the context of COVID-19. One adolescent and three adults reported an initial loss of smell/taste (Table 2).

Pre-existing medical conditions were present in 9/10 patients, including bronchial asthma (4/10), hypothyroidism (2/10), Grave’s disease with hyperthyroidism (1/10), allergies (2/10), attention deficit disorder (1/10), migraine (1/10), history of meningitis (1/10), or Alport’s syndrome (1/10).

Differential diagnostics did not reveal any alternative causes for the debilitating symptoms. An adult patient’s cardiac MRT indicated prior perimyocarditis. Two patients showed bronchial hyper-responsiveness via PFT, with one reporting on pre-existing asthma. Neurologists recommended cranial MRT for nine and EEG for eight patients. Outcomes were mostly normal, except a stable, benign CNS lesion and a transient theta wave slowing in one patient. 9/10 patients complained of OI, with 5/10 patients meeting the diagnostic criteria for PoTS.

All patients showed significant fatigue based on FSS (9/9) or CFQ (1/1) and positive PEM based on the DSQ-PEM, with PEM duration ≥ 24 h (Table 2). Daily function (Bell Score) varied from 20 to 60% (median: 30, IQR: 30–48.75).

In SF-36 results (Fig. 1), all dimensions were impaired compared to German norms for ages 14 to 20 [68]. The physical component summary (PCS) was notably lower in our ME/CFS group (24.9 vs 53.4, P < 0.001). Mean mental health component summary (MCS) score was 44.9 vs 45.0 (P = 0.982) [68].

All patients experienced substantial reductions in occupational, educational, and/or personal activities, indicated by scoring at or below at least two of the three following subscale cut-offs on the SF-36: role physical ≤ 50, social functioning ≤ 62.5, and vitality ≤ 35, as required by the original CCC and the PCD-J [69]. In contrast to moderate to severe depression patients (n = 60, mean age 17.5 ± 1.6 years) [70], our ME/CFS patients scored notably lower in physical functioning (P < 0.001), role physical (P < 0.001), bodily pain (P < 0.001), vitality (P = 0.002), and social functioning (P = 0.016). They scored higher in role emotional (P < 0.001) and mental health (P < 0.001) compared to adolescents and young adults with moderate to severe depression. General health scores showed no significant difference (P = 0.082) (Fig. 1).

All patients fulfilled at least one ME/CFS case definition addressed in the MBSQ. One child fulfilled the CCC and the PDW-R but not the IOM and the PCD-J. Two adolescents met all four sets of criteria, while one met only the broader PDW-R and IOM criteria. All adults fulfilled the CCC, but one did not match the IOM criteria since sleep was not recognized as “unrefreshing” (Table 2).

Most common ME/CFS symptoms were fatigue (10/10), limitations in daily life (10/10), PEM (10/10), unrefreshing sleep (9/10), neurocognitive manifestations (10/10) (e.g., concentration and memory problems), and dizziness (6/10). The most bothering symptoms, the number, frequency, and severity of symptoms varied individually (Table 2, Fig. 2).

Discussion

The MBSQs and SSSs are novel, age-adapted, concise diagnostic tools developed to facilitate the evaluation of ME/CFS criteria in patients with fatigue following COVID-19 and beyond. We reported ten young PCC patients who were diagnosed with ME/CFS using the MBSQs. To our knowledge, this is the first report on ME/CFS in people with PCC ≤ 18 years.

Limited data exists on severe PCC prevalence in children and adolescents. A survey ending on March 30, 2023, in the UK on self-reported PASC showed fewer children aged 2–11 (0.1%) with “limiting day-to-day activities” compared to older groups (12–24 years: 0.26–0.33%, ≥ 25 years: 0.46–0.92%) [71]. Early in the pandemic, a report from Sweden indicated long-term deficits in social participation due to pediatric PCC [72], and a single 19-year-old with post-COVID-ME/CFS was documented in the USA [27, 28]. Meanwhile, additional pediatric patients were diagnosed with ME/CFS at our MCFC and at pediatric partner sites of our multicenter registries (NCT05638724, NCT05778006), as will be reported in more detail (unpublished results).

ME/CFS after viral or other triggers is well documented in children and adolescents [48]. In a pre-pandemic pediatric cohort from Australia, ME/CFS was reported to have followed infections in up to 80% of cases, with EBV infection accounting for 40% of cases [32]. 12.9%, 7.3%, and 4.3% of adolescents in a pre-pandemic US cohort presented with ME/CFS as defined by the PCD-J criteria at six, 12, and 24 months after EBV-induced infectious mononucleosis [73]. ME/CFS defined by meeting at least one of three case definitions (Fukuda, IOM, CCC) manifested in 23% of US college students following symptomatic primary EBV infection, with 8% of the cohort fulfilling the CCC [74]. Pediatric ME/CFS showed recovery rates of 38% at 5 years and 68% at 10 years in Australia [32]. We recently published a first German cohort of adolescence with ME/CFS following EBV with partial recovery over time [75]. Pediatric ME/CFS post-SARS-CoV-2 was thus not unexpected and might be transient with proper diagnosis and treatment.

However, ME/CFS after SARS-CoV-2 infection was already documented in adults [21, 25, 27], but not yet in children. To our knowledge, this is the first report on ME/CFS in PCC patients aged ≤ 18 years, including a child as young as 11 years. All patients experienced persistent symptoms after asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection or mild/moderate COVID-19, with no other explanation, aligning with WHO’s PCC definition [11]. A substantial reduction in occupational, educational, and/or personal activities of these patients was confirmed by a Bell score of ≤ 60% and by scoring at or below at least two of three subscale cut-offs on the SF-36 (role physical ≤ 50, social functioning ≤ 62.5, and vitality ≤ 35) [69].

Consistent with lower rates of severe PCC in children compared to older groups [71], 9/10 of our patients were older than 12 years. At the MCFC, we are regularly seeing young adults up to the age of 20 years, as their healthcare needs align with those of older adolescents. Exclusion of 18-year-olds from pediatric PCC studies might lead to data gaps [76].

Limited data on ME/CFS, in general, may partially result from insufficient disease-specific knowledge and experience [48, 51], and different ME/CFS case definitions render the comparison of published data challenging [77, 78]. Moreover, high time and cost expenses for the diagnostic workup may prevent clinicians from diagnosing ME/CFS and as a result these patients often get no adequate care. Thus, harmonization of diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS and concise diagnostic tools are urgently needed.

Our MBSQ approach was based on the DSQs developed as PROMs by L.A. Jason and colleagues to evaluate ME/CFS diagnosis and associated features in studies with adults, adolescents, and children [54]. Like the DSQs, the MBSQs offer Likert scales for the quantification of symptoms, with a threshold of ≥ 2 for both frequency and severity to indicate diagnostic relevance. Moreover, as introduced by the DSQs, the SSSs provide an algorithm to evaluate different case definitions using a single questionnaire.

Unlike the DSQ-2, the MBSQs do not address the international consensus criteria since they were not recommended by the EUROMENE [31].

Importantly, the MBSQs set a ≥ 14 h PEM duration cutoff for the CCC, PCD-J and CDW-R, but not the IOM criteria. Prior studies showed that most ME/CFS patients experience PEM lasting ≥ 24 h [24]. Some ME/CFS case definitions required a > 24 h duration, including the CDW-R (“Recovery takes more than 24h”) [48]. The original publications of the CCC and the PCD-J stated that “there is a pathologically slow recovery period–usually 24 h or longer” (CCC) [45] and that “the recovery is slow, often taking 24 h or longer” (PCD-J) [47]), respectively. We set the MBSQs’ PEM duration cut-off at ≥ 14 h, encompassing more ME/CFS patients than ≥ 24 h, while still differentiating from most other chronic diseases [24].

The MBSQs also incorporated the broader IOM criteria, endorsed by EUROMENE and CDC. The IOM criteria lack any requirements for PEM duration. Yet, assessing PEM duration in PCS is important as it defines subgroups of patients with different biomarker profiles and clinical courses [21, 79–82]. Consistent case definition use would enhance global ME/CFS healthcare data comparability, including PCC-related ME/CFS.

The MBSQs have limitations. Firstly, they haven’t been compared to other questionnaires, since MCFC patients already face multiple questionnaire challenges. However, the MBSQs are only suggested to aid structured medical interviews, a gold standard for diagnosing ME/CFS and not to be used as PROMs. Future goals include comparing the results of pre-filled MBSQs with results from medical visits and from other questionnaires. Secondly, due to limited cases’ diversity, correlations and consistency couldn’t be analyzed. This will be explored with a larger patient group. Thirdly, a structured interview based on the MBSQ can’t replace a future biomarker. Without the latter, diagnosing PEM, especially in successful pacers, remains tough. Lastly, we only discuss ME/CFS cases here, while ongoing research is evaluating the MBSQs in healthy individuals and other chronic diseases.

Taken together, the MBSQs and SSSs were developed to standardize and accelerate ME/CFS diagnosis at any age in clinical practice and research. They were successfully applied here to children, adolescents, and young adults with PCC. Standardization in PCC and ME/CFS research is urgently needed to compare clinical studies, identify biomarkers, and eventually select and develop specific treatment approaches [83].

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank all patients who participated in the project as well as their families for supporting the participation.

Abbreviations

- bpm

Beats per minute

- CCC

Canadian consensus criteria

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CDW-R

Clinical diagnostic worksheet of P.C. Rowe et al. [48]

- CFC

Charité Fatigue Center

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- DSQ

DePaul symptom questionnaire

- EBV

Epstein-Barr virus

- EEG

Electroencephalography

- EUROMENE

European Network on ME/CFS

- GET

Graded exercise therapy

- HR

Heart rate

- HRQoL

Health-related quality of life

- IOM

Institute of Medicine

- MBSQ

Munich Berlin Symptom Questionnaire

- MCFC

MRI Chronic Fatigue Center for Young People

- MCS

Mental health component summary score

- ME/CFS

Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome

- MRI

TUM university hospital (Klinikum rechts der Isar)

- MRT

Magnetic resonance tomography

- NICE

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- OH

Orthosthatic hypotension

- OI

Orthosthatic intolerance

- PASC

Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19

- PCC

Post-COVID-19 condition

- PCD-J

Pediatric case definition by L.A. Jason et al. [47]

- PCS

Physical component summary score

- PEM

Post-exertional malaise

- PFT

Pulmonary function testing

- PoTS

Postural tachycardia syndrome

- PROM

Patient-reported outcome measure

- RT-PCR

Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

- SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory coronavirus type 2

- SEID

Systemic exertion intolerance disease criteria

- SF-36

Short Form-36 Health Survey

- SSS

Supplementary Scoring Sheet

- UCG

Ultrasound cardiography

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

LC.P., K.W., R.P., K.G., J.P., A.L., A.V., M.A., C.S., and U.B. contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection and analysis were performed by LC.P., M.A., K.W., R.P., J.P., A.L., A.V., and L.M.. The first draft of the manuscript was written by LC.P., K.W., M.A., R.P., and L.M., and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was supported by the Bavarian State Ministry of Health and Care (StMGP), the Federal Ministry of Health (BMG), as well as the Weidenhammer-Zoebele and the Lost Voices foundations (WZS, LVS).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, U.B., upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics of the University Hospital of the Technical University of Munich (116/21, 511/21).

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects (or their legal guardian) involved in the study.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects (or their legal guardian) involved in the study.

Competing interests

U.B. received research grants from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), the BMG, the Bavarian State Ministry of Health and Care (StMGP), the Bavarian State Ministry of Science and the Arts (StMWK), the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF), the People for Children (Menschen für Kinder) foundation, the WZS, the LVS, and the ME/CFS research foundation (ME/CFS RF). C.S. was consulting Roche, Celltrend, and Bayer; she received support for clinical trials by Bayer, Fresenius, and Miltenyi, honoraria for lectures by Fresenius, AstraZeneca, BMS, Roche, Bayer, and Novartis, and research grants from the German Research Association (DFG), the BMBF, the BMG, the WZS, the LVS, and the ME/CFS RF. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Laura-Carlotta Peo, Katharina Wiehler, Rafael Pricoco, and Uta Behrends contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Pei S, Yamana TK, Kandula S, Galanti M, Shaman J. Burden and characteristics of COVID-19 in the United States during 2020. Nature. 2021;598:338–341. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03914-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Msemburi W, Karlinsky A, Knutson V, Aleshin-Guendel S, Chatterji S, Wakefield J. The WHO estimates of excess mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature. 2023;613:130–137. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05522-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mueller MR, Ganesh R, Hurt RT, Beckman TJ. Post-COVID conditions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2023;98:1071–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2023.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis HE, McCorkell L, Vogel JM, Topol EJ. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21:133–146. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00846-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, Madhavan MV, McGroder C, Stevens JS, Cook JR, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021;27:601–615. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324:603–605. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han Q, Zheng B, Daines L, Sheikh A (2022) Long-term sequelae of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of one-year follow-up studies on post-COVID symptoms. Pathogens 11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Zimmermann P, Pittet LF, Curtis N. The challenge of studying long COVID: an updated review. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2022;41:424–426. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000003502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zimmermann P, Pittet LF, Curtis N. How common is long COVID in children and adolescents? Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2021;40:e482–e487. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000003328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Office for National Statistics (2023) Prevalence of ongoing symptoms following coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in the UK: 2 February 2023

- 11.World Health Organization (2023) A clinical case definition for post COVID-19 condition in children and adolescents by expert consensus. World Health Organization

- 12.World Health Organization . A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scharf RE, Anaya JM (2023) Post-COVID syndrome in adults-an overview. Viruses 15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Pellegrino R, Chiappini E, Licari A, Galli L, Marseglia GL. Prevalence and clinical presentation of long COVID in children: a systematic review. Eur J Pediatr. 2022;181:3995–4009. doi: 10.1007/s00431-022-04600-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Molteni E, Sudre CH, Canas LS, Bhopal SS, Hughes RC, Antonelli M, Murray B, Kläser K, Kerfoot E, Chen L, Deng J, Hu C, Selvachandran S, Read K, Capdevila Pujol J, Hammers A, Spector TD, Ourselin S, Steves CJ, Modat M, Absoud M, Duncan EL. Illness duration and symptom profile in symptomatic UK school-aged children tested for SARS-CoV-2. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5:708–718. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00198-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stephenson T, Pinto Pereira SM, Shafran R, de Stavola BL, Rojas N, McOwat K, Simmons R, Zavala M, O'Mahoney L, Chalder T, Crawley E, Ford TJ, Harnden A, Heyman I, Swann O, Whittaker E, Consortium C, Ladhani SN Physical and mental health 3 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection (long COVID) among adolescents in England (CLoCk): a national matched cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022;6:230–239. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00022-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nittas V, Gao M, West EA, Ballouz T, Menges D, Wulf Hanson S, Puhan MA. Long COVID through a public health lens: an umbrella review. Public Health Rev. 2022;43:1604501. doi: 10.3389/phrs.2022.1604501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halpin SJ, McIvor C, Whyatt G, Adams A, Harvey O, McLean L, Walshaw C, Kemp S, Corrado J, Singh R, Collins T, O’Connor RJ, Sivan M (2021) Post discharge symptoms and rehabilitation needs in survivors of COVID-19 infection: a cross-sectional evaluation. J Med Virol 93:1013–1022 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Townsend L, Dyer AH, Jones K, Dunne J, Mooney A, Gaffney F, O’Connor L, Leavy D, O’Brien K, Dowds J, Sugrue JA, Hopkins D, Martin-Loeches I, Ni Cheallaigh C, Nadarajan P, McLaughlin AM, Bourke NM, Bergin C, O’Farrelly C, Bannan C, Conlon N (2020) Persistent fatigue following SARS-CoV-2 infection is common and independent of severity of initial infection. PLoS ONE 15:e0240784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Ceban F, Ling S, Lui LMW, Lee Y, Gill H, Teopiz KM, Rodrigues NB, Subramaniapillai M, Di Vincenzo JD, Cao B, Lin K, Mansur RB, Ho RC, Rosenblat JD, Miskowiak KW, Vinberg M, Maletic V, McIntyre RS. Fatigue and cognitive impairment in post-COVID-19 syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2022;101:93–135. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kedor C, Freitag H, Meyer-Arndt L, Wittke K, Hanitsch LG, Zoller T, Steinbeis F, Haffke M, Rudolf G, Heidecker B, Bobbert T, Spranger J, Volk H-D, Skurk C, Konietschke F, Paul F, Behrends U, Bellmann-Strobl J, Scheibenbogen C. A prospective observational study of post-COVID-19 chronic fatigue syndrome following the first pandemic wave in Germany and biomarkers associated with symptom severity. Nat Commun. 2022;13:5104. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32507-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jason LA, Dorri JA. ME/CFS and post-exertional malaise among patients with long COVID. Neurol Int. 2022;15:1–11. doi: 10.3390/neurolint15010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choutka J, Jansari V, Hornig M, Iwasaki A. Unexplained post-acute infection syndromes. Nat Med. 2022;28:911–923. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01810-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cotler J, Holtzman C, Dudun C, Jason LA (2018) A Brief Questionnaire to Assess Post-Exertional Malaise. Diagnostics (Basel) 8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Bonilla H, Quach TC, Tiwari A, Bonilla AE, Miglis M, Yang PC, Eggert LE, Sharifi H, Horomanski A, Subramanian A, Smirnoff L, Simpson N, Halawi H, Sum-ping O, Kalinowski A, Patel ZM, Shafer RW, Geng LN. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome is common in post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC): results from a post-COVID-19 multidisciplinary clinic. Front Neurol. 2023;14:1090747. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1090747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.González-Hermosillo JA, Martínez-López JP, Carrillo-Lampón SA, Ruiz-Ojeda D, Herrera-Ramírez S, Amezcua-Guerra LM, Martínez-Alvarado MDR (2021) Post-acute COVID-19 symptoms, a potential link with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: a 6-month survey in a Mexican cohort. Brain Sci 11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Petracek LS, Suskauer SJ, Vickers RF, Patel NR, Violand RL, Swope RL, Rowe PC. Adolescent and young adult ME/CFS after confirmed or probable COVID-19. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021;8:668944. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.668944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petracek LS, Broussard CA, Swope RL, Rowe PC (2023) A case study of successful application of the principles of ME/CFS care to an individual with long COVID. Healthcare (Basel) 11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Jason LA, Johnson M, Torres C (2023) Pediatric post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Fatigue: Biomed Health Behav 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Rasa S, Nora-Krukle Z, Henning N, Eliassen E, Shikova E, Harrer T, Scheibenbogen C, Murovska M, Prusty BK. Chronic viral infections in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) J Transl Med. 2018;16:268. doi: 10.1186/s12967-018-1644-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nacul L, Authier FJ, Scheibenbogen C, Lorusso L, Helland IB, Martin JA, Sirbu CA et al. (2021) European Network on Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (EUROMENE): expert consensus on the diagnosis, service provision, and care of people with ME/CFS in Europe. Medicina (Kaunas) 57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Rowe KS. Long term follow up of young people with chronic fatigue syndrome attending a pediatric outpatient service. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:21. doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Estévez-López F, Mudie K, Wang-Steverding X, Bakken IJ, Ivanovs A, Castro-Marrero J, Nacul L, Alegre J, Zalewski P, Słomko J, Strand EB, Pheby D, Shikova E, Lorusso L, Capelli E, Sekulic S, Scheibenbogen C, Sepúlveda N, Murovska M, Lacerda E (2020) Systematic review of the epidemiological burden of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome across europe: current evidence and EUROMENE research recommendations for epidemiology. J Clin Med 9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Komaroff AL, Lipkin WI. Insights from myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome may help unravel the pathogenesis of postacute COVID-19 syndrome. Trends Mol Med. 2021;27:895–906. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2021.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Behnood SA, Shafran R, Bennett SD, Zhang AXD, O’Mahoney LL, Stephenson TJ, Ladhani SN, De Stavola BL, Viner RM, Swann OV (2022) Persistent symptoms following SARS-CoV-2 infection amongst children and young people: a meta-analysis of controlled and uncontrolled studies. J Infect 84:158–170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Tsampasian V, Elghazaly H, Chattopadhyay R, Debski M, Naing TKP, Garg P, Clark A, Ntatsaki E, Vassiliou VS. Risk factors associated with post-COVID-19 condition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183:566–580. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.0750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nacul LC, Lacerda EM, Pheby D, Campion P, Molokhia M, Fayyaz S, Leite JC, Poland F, Howe A, Drachler ML. Prevalence of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) in three regions of England: a repeated cross-sectional study in primary care. BMC Med. 2011;9:91. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jason LA, Richman JA, Rademaker AW, Jordan KM, Plioplys AV, Taylor RR, McCready W, Huang CF, Plioplys S. A community-based study of chronic fatigue syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2129–2137. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.18.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jason L, Mirin A. Updating the National Academy of Medicine ME/CFS prevalence and economic impact figures to account for population growth and inflation. Fatigue: Biomed Health Behav. 2021;9:9–13. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lim E-J, Ahn Y-C, Jang E-S, Lee S-W, Lee S-H, Son C-G. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) J Transl Med. 2020;18:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02269-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crawley EM, Emond AM, Sterne JAC. Unidentified Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) is a major cause of school absence: surveillance outcomes from school-based clinics. BMJ Open. 2011;1:e000252. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jason LA, Katz BZ, Sunnquist M, Torres C, Cotler J, Bhatia S. The prevalence of pediatric myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome in a community-based sample. Child Youth Care Forum. 2020;49:563–579. doi: 10.1007/s10566-019-09543-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mirin AA, Dimmock ME, Jason LA. Updated ME/CFS prevalence estimates reflecting post-COVID increases and associated economic costs and funding implications. Fatigue: Biomed Health Behav. 2022;10:83–93. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roessler M, Tesch F, Batram M, Jacob J, Loser F, Weidinger O, Wende D, et al. Post-COVID-19-associated morbidity in children, adolescents, and adults: a matched cohort study including more than 157,000 individuals with COVID-19 in Germany. PLoS Med. 2022;19:e1004122. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1004122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carruthers BM, Jain AK, De Meirleir KL, Peterson DL, Klimas NG, Lerner AM, Bested AC, Flor-Henry P, Joshi P, Powles ACP, Sherkey JA, van de Sande MI. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. J Chronic Fatigue Syndr. 2003;11:7–115. doi: 10.1300/J092v11n01_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clayton EW. Beyond myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: an IOM report on redefining an illness. JAMA. 2015;313:1101–1102. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jason LA, Jordan K, Miike T, Bell DS, Lapp C, Torres-Harding S, Rowe K, Gurwitt A, De Meirleir K, Van Hoof ELS. A pediatric case definition for myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome. J Chronic Fatigue Syndr. 2006;13:1–44. doi: 10.1300/J092v13n02_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rowe PC, Underhill RA, Friedman KJ, Gurwitt A, Medow MS, Schwartz MS, Speight N, Stewart JM, Vallings R, Rowe KS. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome diagnosis and management in young people: a primer. Front Pediatr. 2017;5:121. doi: 10.3389/fped.2017.00121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2021) Myalgic encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy)/chronic fatigue syndrome: diagnosis and management.

- 50.Brown MM, Bell DS, Jason LA, Christos C, Bell DE. Understanding long-term outcomes of chronic fatigue syndrome. J Clin Psychol. 2012;68:1028–1035. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hng KN, Geraghty K, Pheby DFH (2021) An audit of UK hospital doctors' knowledge and experience of myalgic encephalomyelitis. Medicina (Kaunas) 57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Froehlich L, Hattesohl DBR, Jason LA, Scheibenbogen C, Behrends U, Thoma M (2021) Medical care situation of people with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome in Germany. Medicina (Kaunas) 57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Froehlich L, Niedrich J, Hattesohl DBR, Behrends U, Kedor C, Haas JP, Stingl M, Scheibenbogen C (2023) Evaluation of a webinar to increase health professionals' knowledge about Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). Manuscript submitted for publication [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Jason LA, Sunnquist M. The development of the DePaul Symptom Questionnaire: original, expanded, brief, and pediatric versions. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:330. doi: 10.3389/fped.2018.00330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bedree H, Sunnquist M, Jason LA. The DePaul Symptom Questionnaire-2: a validation study. Fatigue. 2019;7:166–179. doi: 10.1080/21641846.2019.1653471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bavarian State Ministry of Health and Care (2021) Modellprojekt “Post-COVID Kids Bavaria”. Teilprojekt 2 “Post-COVID Kids Bavaria - PCFC” (Post-COVID Fatigue Center). Bavarian State Ministry of Health and Care

- 57.Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J, Steinberg AD. The Fatigue Severity Scale: application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol. 1989;46:1121–1123. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520460115022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chalder T, Berelowitz G, Pawlikowska T, Watts L, Wessely S, Wright D, Wallace EP. Development of a fatigue scale. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37:147–153. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90081-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bell DS (1994) The doctor's guide to chronic fatigue syndrome: understanding, treating, and living with CFIDS. Da Capo Press

- 60.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lerdal A, Wahl A, Rustoen T, Hanestad BR, Moum T. Fatigue in the general population: a translation and test of the psychometric properties of the Norwegian version of the fatigue severity scale. Scand J Public Health. 2005;33:123–130. doi: 10.1080/14034940410028406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jackson C. The Chalder Fatigue Scale (CFQ 11) Occup Med (Lond) 2015;65:86. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqu168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee J, Vernon SD, Jeys P, Ali W, Campos A, Unutmaz D, Yellman B, Bateman L. Hemodynamics during the 10-minute NASA Lean Test: evidence of circulatory decompensation in a subset of ME/CFS patients. J Transl Med. 2020;18:314. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02481-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roma M, Marden CL, Rowe PC. Passive standing tests for the office diagnosis of postural tachycardia syndrome: new methodological considerations. Fatigue: Biomed Health Behav. 2018;6:179–192. [Google Scholar]

- 65.World Health Organization (2018) ICD-11 MMS. International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics. 8D89.2 Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome

- 66.Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, Grubb BP, Fedorowski A, Stewart JM, Arnold AC, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health Expert Consensus Meeting - Part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021;235:102828. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Centers for Disease Control and Prevetion (2021) Symptoms and diagnosis of ME/CFS. CDC

- 68.Bellach BM, Ellert U, Radoschewski M (2000) Der SF-36 im Bundes-Gesundheitssurvey Erste Ergebnisse und neue Fragen: Erste Ergebnisse und neue Fragen. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 43:210–216

- 69.Jason L, Brown M, Evans M, Anderson V, Lerch A, Brown A, Hunnell J, Porter N. Measuring substantial reductions in functioning in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33:589–598. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2010.503256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kristjánsdóttir J, Olsson GI, Sundelin C, Naessen T. Could SF-36 be used as a screening instrument for depression in a Swedish youth population? Scand J Caring Sci. 2011;25:262–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Office for National Statistics (2023) Prevalence of ongoing symptoms following coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in the UK: 30 March 2023

- 72.Ludvigsson JF. Case report and systematic review suggest that children may experience similar long-term effects to adults after clinical COVID-19. Acta Paediatr. 2021;110:914–921. doi: 10.1111/apa.15673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Katz BZ, Shiraishi Y, Mears CJ, Binns HJ, Taylor R. Chronic fatigue syndrome after infectious mononucleosis in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2009;124:189–193. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jason LA, Cotler J, Islam MF, Sunnquist M, Katz BZ. Risks for developing myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome in college students following infectious mononucleosis: a prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:e3740–e3746. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pricoco R, Meidel P, Hofberger T, Zietemann H, Mueller Y, Wiehler K, Michel K, Paulick J, Leone A, Haegele M, Mayer-Huber S, Gerrer K, Mittelstrass K, Scheibenbogen C, Renz-Polster H, Mihatsch L, Behrends U (2023) One-year follow-up of young people with ME/CFS following infectious mononucleosis by Epstein-Barr virus. medRxiv:2023.2007.2024.23293082

- 76.Borch L, Holm M, Knudsen M, Ellermann-Eriksen S, Hagstroem S. Long COVID symptoms and duration in SARS-CoV-2 positive children - a nationwide cohort study. Eur J Pediatr. 2022;181:1597–1607. doi: 10.1007/s00431-021-04345-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.VanElzakker MB, Brumfield SA, Lara Mejia PS. Neuroinflammation and cytokines in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): a critical review of research methods. Front Neurol. 2018;9:1033. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.01033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Conroy KE, Islam MF, Jason LA (2022) Evaluating case diagnostic criteria for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS): toward an empirical case definition. Disabil Rehabil 1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.Legler AF, Meyer-Arndt L, Mödl L, Kedor C, Freitag H, Stein E, Hoppmann U, Rust R, Konietschke F, Thiel A, Paul F, Scheibenbogen C, Bellmann-Strobl J (2023) Symptom persistence and biomarkers in post-COVID-19/chronic fatigue syndrome – results from a prospective observational cohort. medRxiv:2023.2004.2015.23288582

- 80.Sotzny F, Filgueiras IS, Kedor C, Freitag H, Wittke K, Bauer S, Sepulveda N, et al. Dysregulated autoantibodies targeting vaso- and immunoregulatory receptors in Post COVID Syndrome correlate with symptom severity. Front Immunol. 2022;13:981532. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.981532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Haffke M, Freitag H, Rudolf G, Seifert M, Doehner W, Scherbakov N, Hanitsch L, Wittke K, Bauer S, Konietschke F, Paul F, Bellmann-Strobl J, Kedor C, Scheibenbogen C, Sotzny F. Endothelial dysfunction and altered endothelial biomarkers in patients with post-COVID-19 syndrome and chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) J Transl Med. 2022;20:138. doi: 10.1186/s12967-022-03346-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Flaskamp L, Roubal C, Uddin S, Sotzny F, Kedor C, Bauer S, Scheibenbogen C, Seifert M (2022) Serum of post-COVID-19 syndrome patients with or without ME/CFS differentially affects endothelial cell function in vitro. Cells 11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 83.Wong TL, Weitzer DJ (2021) Long COVID and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)-a systemic review and comparison of clinical presentation and symptomatology. Medicina (Kaunas) 57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, U.B., upon reasonable request.