Abstract

Background

Cancer is a heterogeneous disease driven by complex molecular alterations. Cancer subtypes determined from multi-omics data can provide novel insight into personalised precision treatment. It is recognised that incorporating prior weight knowledge into multi-omics data integration can improve disease subtyping.

Methods

We develop a weighted method, termed weight-boosted Multi-Kernel Learning (wMKL) which incorporates heterogeneous data types as well as flexible weight functions, to boost subtype identification. Given a series of weight functions, we propose an omnibus combination strategy to integrate different weight-related P-values to improve subtyping precision.

Results

wMKL models each data type with multiple kernel choices, thus alleviating the sensitivity and robustness issue due to selecting kernel parameters. Furthermore, wMKL integrates different data types by learning weights of different kernels derived from each data type, recognising the heterogeneous contribution of different data types to the final subtyping performance. The proposed wMKL outperforms existing weighted and non-weighted methods. The utility and advantage of wMKL are illustrated through extensive simulations and applications to two TCGA datasets. Novel subtypes are identified followed by extensive downstream bioinformatics analysis to understand the molecular mechanisms differentiating different subtypes.

Conclusions

The proposed wMKL method provides a novel strategy for disease subtyping. The wMKL is freely available at https://github.com/biostatcao/wMKL.

Subject terms: Statistical methods, Data integration

Background

Cancer is a complex and heterogeneous disease. Even if it originates from the same tissue and has the same histological grading and pathological staging, the underlying molecular mechanisms can vary dramatically between patients. Identifying molecular subtypes based on common molecular features and detecting the subtype-specific molecular alterations correlated with clinical outcomes is critically important for targeted therapy, as well as for better prognosis and personalised precision treatment.

The molecular mechanisms of tumours are complex and influenced by a system of interacting molecules and macromolecules that take part in physical and biochemical processes in structured environments. Subtype identification focusing on a single-omics data type such as gene expression can hardly capture the subtleties of a tumour. With the accumulation of vast amounts of omics data from large-scale cancer genomic projects, e.g., The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), we are able to integrate multi-omics data types for comprehensive molecular subtyping. However, a few critical challenges hinder the subtyping methodology development: (i) the relatively low number of biological samples compared to a large number of biological variables; (ii) the unknown contribution of different omics data types to subtyping, i.e., data heterogeneity; and (iii) the complexity of biological systems and biological interaction network in multi-omics data.

Several strategies have been proposed to address these challenges and can be largely divided into three categories [1]: (i) Early integration (e.g., LRAcluster [2]), which first focuses on concatenating all omics matrices, then applies single-omics clustering algorithms on the combined matrix, with possible variable selection to handle the high data dimension. Early integration is the most simple approach but has several drawbacks as described in the literature [1]; (ii) Late integration (e.g., PINS [3]), which first clusters samples based on each omics data type, then integrates different clusters to form aggregated clusters. It is a flexible approach by using any clustering algorithm without having to create a model that unifies all these algorithms. However, it loses power due to failing to capture weak signals in each omics data type; and (iii) Intermediate integration, such as similarity-based methods (e.g., SNF [4], rMKL-LPP [5, 6]), dimension reduction methods (e.g., JIVE [7]), and statistical modelling-based methods (e.g., iCluster [8]). Specially, rMKL-LPP regularises unsupervised multiple kernel learning and performs the best among the integration algorithms in most cases, though no algorithm consistently outperformed the others [1]. Recently, a method called Cancer Integration via Multi-kernel Learning (CIMLR) [9] was proposed which takes advantage of multiple kernel-learning methods such as rMKL-LPP, but with a different optimisation approach. It learns the optimal similarity matrix directly from multi-omics data by combining multiple Gaussian kernels, hence outperforming most current state-of-the-art tools in speed, accuracy, and prediction of patient survival.

Although the above-mentioned methods have successfully addressed some issues, most works rarely use prior information to facilitate subtype identification. It is widely accepted that disease-associated biomolecular signals play crucial roles in defining similarity toward a more efficient clustering performance. Based on SNF, a weighted SNF [10] utilising miRNA-TF-mRNA regulatory network to extract feature weight was developed; but it is limited to specific omics data types with available network information. A more general framework of weighted SNF method called abSNF [11] was proposed using association signals to boost the performance of SNF. However, the kernel parameter settings in abSNF are quite ambiguous. It does not perform well when there is high heterogeneity among different omics data types.

In abSNF and other weight-boosted methods, the prior weight information was incorporated without considering the prognostic performance, a critical goal for the successful treatment of cancer patients [12]. A recently developed method, survClust [13], incorporates survival outcome information by taking the log-hazard ratio (estimated from univariate Cox regression) as a prior weight to identify prognostically significant subtypes. However, survClust is limited since it treats all data types equally by simply taking the average of weighted distance matrices from each data type as the final distance matrix. By doing so, it ignores the heterogeneity between different omics data types. In addition, it suffers from high computational costs due to expensive cross-validation and complex cluster relabelling.

To overcome the aforementioned limitations of multi-omics subtyping algorithms, we develop a novel method, coined as prior weight-boosted Multi-Kernel Learning (wMKL), by borrowing the CIMLR idea. wMKL incorporates the prior weight in each kernel construction and learns a measure of sample similarity by combing multiple weighted kernels constructed from each data type. wMKL employs a rank constraint in the aggregated similarity matrix to enforce block structures and further carries out graph diffusion to improve weak similarity measures. Thus, it addresses the suffered sensitivity issue with respect to kernel parameters in weighted modelling and allows for great flexibility on the prior weight and enables robust subtype identification. Moreover, wMKL does not assume equal importance of different data types and, thus, can efficiently capture data heterogeneity. As such, it is well suited to model heterogeneous multi-omics data. When different prior weight information is available, we adopt an omnibus P-value combination idea to aggregate the weight information to further improve the signal strength and subtyping performance, and enhance the biological significance of identified subtypes by incorporating prognostic information. Specifically, our method considers data heterogeneity and incorporates signal strength and prognostic information as prior weight to enhance subtyping. Therefore, the results are both biologically and clinically meaningful. We illustrate the benefits of wMKL with simulations and applications to two cancer studies, i.e., papillary renal cell carcinoma (PRCC) and Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) obtained from TCGA. Our method provides a general framework for cancer subtyping with efficient data integration.

Methods

wMKL and the flowchart

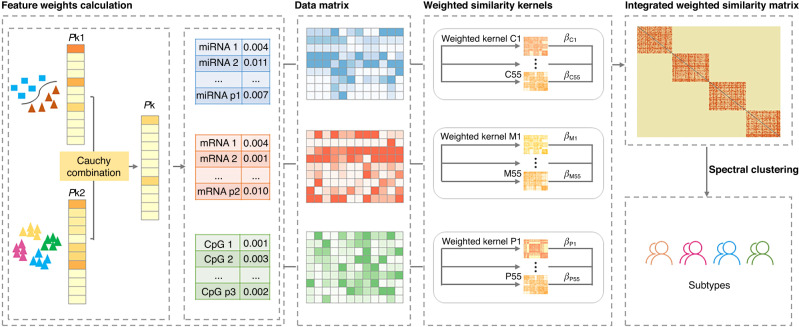

wMKL incorporates feature weight in the construction of the kernel-based sample similarity to boost the subtyping performance under the CIMLR framework. The proposed wMKL consists of three steps (see Fig. 1): (1) Calculating the weight for each feature. We focus on the disease-associated signal which down-weights features that do not provide differentiation information about an outcome. The signal-related outcomes can be normal vs. tumour tissues, treatment responses, survival outcomes and other clinical and histopathological characteristics. Here, we specifically focus on features that can better differentiate between normal vs. tumour tissues (using paired or two-sample t-tests depending on the samples collected), and on pathological stage-driven features with relevance to survival (using Kruskal–Wallis H-test). The two types of P-values obtained for each feature are then integrated with a Cauchy combination method to get an aggregated P-value for each feature; (2) Constructing the prior weight-boosted similarity kernel. We first calculate the weighted kernel for each data type, then learn the optimised integrated sample similarity kernel by integrating the weighted kernels obtained from each data type with a multi-kernel-learning strategy. The contribution of each data type is reflected by their corresponding weight coefficient; and (3) Disease subtyping. We use spectral clustering to subtype disease subjects based on the integrated boosted similarity matrix.

Fig. 1. Flowchart of wMKL illustrated with three omics data types, namely miRNA, mRNA and DNA methylation.

Considering different information (e.g., tumour vs. normal tissues), different P-values for each feature can be obtained in each data type which are further combined through a Cauchy combination method to get an aggregated P-value for each feature. Then, a weight-boosted similarity kernel can be constructed and optimised for each data type using wMKL, which is further integrated to get a final weighted similarity matrix based on which patients are classified into different subtype groups with spectral clustering.

In wMKL, we borrow the optimisation idea from CIMLR while incorporating feature weights when subtyping cancer samples [9]. CIMLR was originally built upon the SIMLR algorithm [14]. Suppose there are J number of omics data types each with number of features. Let denote the gth omics data type matrix with a sample size n. It can be converted to a similarity kernel matrix using the Gaussian kernel function defined as , where and represent the ith and jth sample vector containing number of features in the gth omics data type, and is the variance. Without loss of generality, we assume corresponding to the three omics data types analysed in the real data analysis, for further illustration. The method, however, is not restricted to .

For each omics data type, there are hundreds or thousands of features which do not have the same differentiation power when subtyping cancer samples. Features that show strong association signals with tumour types, treatment responses, survival outcomes and other clinical and histopathological characters should have high discrimination power when differentiating cancer subtypes [11]. For example, compared to a feature that has the same expression level in tumour and normal tissue, a feature that is significantly up- or downregulated in the tumour sample should contribute more to cancer subtyping, thus, should be up-weighted when calculating the kernel function [11]. The weights can be obtained by using the feature-level association P-value (denoted as ) calculated from a paired t-test (or a two-sample t-test) between the tumour tissue and adjacent normal tissue (or independent normal tissue) for the feature. In addition to this weight function, we incorporate another outcome-related weight function derived from the pathological stage-driven features, which is obtained by using the feature-level association P-value (denoted as ) calculated from a Kruskal–Wallis H-test among different pathological stage levels (e.g., stage I–IV in PRCC and LUAD cancer) for feature .

The two P-values are then integrated by a Cauchy combination method [15] to get an aggregated omnibus P-value denoted as . Specifically, let . Then, the Cauchy combined P-value is calculated as . The feature-level weight is defined as, . Then, the weighted similarity kernel can be calculated by,

| 1 |

where . Instead of directly optimising the kernel parameter , we construct d number of kernels (say 55) for each omics data type using the K-nearest neighbours algorithm with different hyperparameters (the number of neighbours r and ) independently (see Wang et al. [14] for details). Thus, we have a total of 55×J weighted kernels for the J data types. Next, we take a weighted sum of the 55×J kernels and optimise the following objective function to solve for the weights and further construct the final patient similarity matrix S [14], based on the newly proposed weighted similarity kernel defined in (1), as follows:

| 2 |

where and are and identity matrices with C representing the number of subtype groups, ; represents the matrix trace; and are non-negative tuning parameters; denotes the Frobenius norm; and L is a low-dimensional matrix imposing the low-rank structure on S. In the end, if there are C subgroups among the n cancer patients, then S should have an approximate block-diagonal structure with C blocks [14]. More discussions on each of the four terms in (2) can be found in Wang et al. [14].

Based on the integrated sample similarity matrix , we apply the spectral clustering algorithm [16] to accomplish sample clustering, which is stable and effective in capturing the global structure of similarities.

Estimation of the number of clusters

Estimating the intrinsic number of clusters is a key issue in disease subtyping. Here we follow the separation cost idea originally proposed in SIMLR and later adopted in CIMLR to estimate the best number of clusters. For a given number of clusters C, the goal is to find an indication matrix , where is a matrix of the top eigenvectors of the similarity Laplacian, and is a rotation matrix. Let . We try to find that minimises the following objective function (also called separation cost [4]):

A gradient descent algorithm is applied to minimise this cost function over all possible rotations [4]. We choose the best number of clusters as the one that results in the largest drop in the value of over a set of possible C values.

Disease subtyping

After getting the optimised integrated sample similarity matrix , we proceed to identify disease subtypes out of individuals. Let be the cluster indicator of individual i where if sample i belongs to the cth cluster, and 0 otherwise. The clustering structure is represented as a partition matrix .

The spectral clustering algorithm can naturally capture the global structure of sample similarities effectively and has been shown to outperform traditional K-means algorithm [17]. The spectral clustering algorithm [16], aiming to minimise the ratio cut objective function, is defined as,

where ; ; and is a diagonal degree matrix with degrees on the diagonal and .

Simulation design

We performed simulation studies to investigate the performance of the wMKL method and compared it with other methods, namely abSNF [11], CIMLR [9] and SNF [4]. We simulated three omics data types and four patient subtype groups in such a way that any single-omics data type can only distinguish three subtype groups, but together four subtype groups can be distinguished (see Fig. S1 for the heatmap illustration in the Supplementary Materials). We allowed different subtype groups to have different means and variances. We compared the ability and robustness of wMKL in subtyping the four groups with other methods under different noise intensity levels, including low vs. high within-data type noise level and low vs. high cross-data type noise level. Two simulation scenarios were considered. In Scenario I, we generated three pseudo-omics data types, each one consisting of multiple cluster structures (see Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Materials), which was similar to the one reported elsewhere [11]. In Scenario II, we borrowed real data information and combined with a pre-defined cluster structure to recapitulate the characteristics of real genomic data using singular value decomposition (SVD) (see Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Materials). Simulation datasets were generated as in Xu et al. [18] and Shi et al. [19]. We used the real genomic data obtained from the GEO database, namely GSE51557 [20], GSE73002 [21] and GSE10645 [22] corresponding to DNA methylation, mRNA expression and miRNA expression, respectively. Moreover, different dimensions of signal features were considered in both scenarios. In each scenario, we constructed two datasets (SimData1 and SimData2). SimData1 has a clear boundary between subtypes, while SimData2 possesses fuzzy boundaries.

We considered one type of weight function in simulation to illustrate the idea, with prior weight focusing on features that can better differentiate normal and tumour tissues. The three data types from independent normal tissues were simulated from a normal distribution with no cluster structure. The prior weights were based on association-signal-annotation P-values (denoted as ) by comparing tumour samples to normal samples using a two-sample t-test for feature , i.e., . We evaluated clustering performance using normalised mutual information (NMI) and the accuracy rate of estimating true subtype groups. A detailed description of the simulation design together with different parameters is given in the Supplementary Materials.

TCGA datasets

We focused on two independent cancer data, the PRCC and LUAD data downloaded from the TCGA website using the TCGAbiolinks software [23]. Three types of omics data sources were considered, miRNA expression, mRNA expression and promoter CpG methylation. Promoter CpGs are those methylations that are located only at the promoter region within 2 kb of a transcription start site [24]. Promoter CpGs on sex chromosomes were excluded. Features with more than 30% missing rate in miRNA, mRNA and methylation were omitted, and the remaining missing data were imputed using the K-nearest neighbour method [25].

After quality control, there are 207 tumour samples with 437 miRNA, 16,534 mRNA and 49,022 promoter CpG methylation features for the PRCC data. The adjacent normal samples with the same features were obtained to generate the prior weight for each feature. We have 34 adjacent normal samples for miRNA, 31 adjacent normal samples for mRNA, and 45 adjacent normal samples for promoter CpG methylation. There are 138 patients with pathological stage I, 14 with stage II, 43 with stage III, and 12 with stage IV.

For LUAD, there are 360 tumour samples with 480 miRNA, 16,873 mRNA and 49,021 promoter CpG methylation features. There are 46 adjacent normal samples for miRNA, 59 adjacent normal samples for mRNA, and 32 adjacent normal samples for promoter CpG methylation. There are 201 patients with pathological stage I, 86 with stage II, 56 with stage III, and 17 with stage IV. We incorporate two types of weight function in real data analysis for PRCC and LUAD, that is, calculated from the paired t-test between the tumour tissue and adjacent normal tissue, and calculated from a Kruskal–Wallis H-test among different pathological stage levels (stage I–IV) for feature . and are integrated by a Cauchy combination method [15] to get the aggregated omnibus P-value . The feature-level weight is defined as, which is used to calculate the weighted similarity kernel.

Downstream statistical analysis after subtyping

Differential and enrichment analysis

We conducted differential expression analysis across subtypes for each omics data type using the Kruskal–Wallis H-test, followed by an FDR adjustment. For the differential expression features in each cluster, we performed enrichment analysis to further check if each differential feature was enriched in this cluster, using the hypergeometric test with an FDR-adjusted P-value < 0.05. The significantly enriched features in each cluster were selected similarly in the one reported elsewhere [9], which were detailed as follows. To select genes significantly enriched for mRNAs, we considered a gene to be over- or under-expressed if the standardised mRNA value was larger than 0.7 or lower than −0.7. In each cluster, we performed the hypergeometric test to assess whether this cluster is significantly enriched for either overexpression or under-expression of a gene. For miRNA, we selected the significantly deregulated genes using the same criteria as mRNA. For methylations, a CpG site was considered to be highly methylated when the beta value was greater than 0.8, and unmethylated when the beta value was less than 0.2. In each cluster, we performed the hypergeometric test to assess whether this cluster was significantly enriched for either high or low methylation of a CpG site.

To choose features that were most representative of an individual cluster, we used additional stringent conditions. Specifically, of the significantly enriched features, we chose features that were only altered in at least 60% of the samples in a cluster and <40% of the samples in at least one other cluster. Using 3 clusters as an example, for the significantly enriched over-expressed mRNA in cluster 1, we chose the features that were over-expressed in at least 60% of the samples in cluster 1, and <40% of the samples in either cluster 2 or cluster 3, or both. The final selected features after differential and enrichment analysis, were called differentially enriched features.

Construction of supervised classifiers to predict the subtype in new type II PRCC samples

Within the high heterogeneous and poor prognosis of type II PRCC, there is a high demand to construct supervised classifier by first defining subtypes based on wMKL and the differential features enriched in dominantly type II PRCC subtypes, so that we can classify any new type II PRCC samples. We used six machine-learning models, namely, the kernel partial least squares with genetic algorithm (GA-KPLS) [26], least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO), random forest, ridge regression, support vector machine (SVM) and neural network, to build the model and predict the subtypes of type II PRCC (namely, subtype 2 and subtype 3). The training data and external testing data were randomly selected at a ratio of 70:30, and the whole process of random selection was repeated 1000 times. We used R glmnet package to perform LASSO and Ridge regression, R e1071 package to perform SVM and R package nnet to perform the neural network analysis. The evaluation criteria for prediction performance include area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity (Se), specificity (Sp), accuracy (ACC), Youden index, G-means and Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC).

Regulation analysis between multi-omics data

Changes in miRNAs and methylations can lead to changes in mRNAs. For the significantly differential enriched features, we applied a penalised canonical correlation analysis (CCA) method [27] to examine correlations between miRNAs, methylations and mRNAs. We used the Venn diagram [28] to identify overlapped genes. Genes targeted by miRNAs were predicted through miRTarBase (an experimentally validated microRNA-target interactions database) [29]. We further examined correlations for overlapped genes across subtypes.

Pathway and immune cell infiltration analysis

We characterised differential pathway activities in subtypes focusing on pathway activity scores of 14 signalling pathways based on gene expression data using PROGENy [30]. Immune cell infiltration levels for each patient were obtained from TIMER2.0 web server [31]. TIMER2.0 provides an estimation of immune infiltration levels using seven algorithms. We focused on the state-of-the-art TIMER algorithms. We further conducted the differential analysis for pathway activity and immune cell infiltration across subtypes using the Kruskal–Wallis H-test. An FDR-adjusted P-value (<0.05) was used to declare significantly differential pathways and immune cells. The Kyoto Encyclopaedia of the Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis was conducted in KOBAS 3.0 [32].

Results

Simulation results

The simulation study confirmed that wMKL is robust and outperforms abSNF, CIMLR and SNF across all settings under the two simulation scenarios, especially having a great advantage in correctly estimating the subtype groups. Table 1 shows the difference in NMI of different methods across 1000 replicates in each of the simulation settings in Scenario I. The corresponding results under Scenario II were rendered to the Supplementary Materials (see Table S1). In general, wMKL achieves higher NMI than other methods, indicating the good performance of wMKL over its counterparts. As the percentage of the signal features increases, the performance of the four methods all improves. The within-data noise has a larger impact on NMI than the cross-data noise does. That is, the increase of NMI is more striking when decreasing the within-data noise level, compared to the results by decreasing the cross-data noise level. The same trend was observed for Scenario II (see Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials). Though the performance of wMKL and abSNF is similar under different within-data noise levels, wMKL significantly outperforms abSNF under different cross-data noise levels, in particular when the signal strength is weak. For example, under a 2.5% signal strength and low-cross noise setting, the value of NMI for wMKL is 0.923 while it is 0.756 for abSNF, showing the great advantage of wMKL when there is heterogeneity across different data types.

Table 1.

Performance measured by NMI in simulation Scenario I.

| Sign% | Method | Low-within noise | High-within noise | Low-cross noise | High-cross noise | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SimData1 | 2.5% | wMKL | 0.996 (0.008) | 0.777 (0.051) | 0.923 (0.033) | 0.920 (0.033) |

| abSNF | 0.996 (0.008) | 0.720 (0.060) | 0.756 (0.064) | 0.718 (0.054) | ||

| CIMLR | 0.475 (0.042) | 0.239 (0.050) | 0.381 (0.035) | 0.377 (0.037) | ||

| SNF | 0.453 (0.050) | 0.264 (0.038) | 0.369 (0.035) | 0.368 (0.035) | ||

| 5% | wMKL | 1.000 (0.001) | 0.933 (0.029) | 0.993 (0.011) | 0.992 (0.011) | |

| abSNF | 1.000 (0.001) | 0.894 (0.042) | 0.924 (0.041) | 0.877 (0.056) | ||

| CIMLR | 0.796 (0.054) | 0.444 (0.038) | 0.484 (0.038) | 0.481 (0.037) | ||

| SNF | 0.798 (0.054) | 0.416 (0.049) | 0.499 (0.040) | 0.497 (0.040) | ||

| 10% | wMKL | 1.000 (0.000) | 0.989 (0.014) | 1.000 (0.001) | 1.000 (0.001) | |

| abSNF | 1.000 (0.000) | 0.979 (0.021) | 0.981 (0.019) | 0.962 (0.026) | ||

| CIMLR | 0.992 (0.012) | 0.708 (0.051) | 0.761 (0.060) | 0.729 (0.055) | ||

| SNF | 0.935 (0.076) | 0.691 (0.042) | 0.670 (0.039) | 0.657 (0.034) | ||

| SimData2 | 2.5% | wMKL | 0.974 (0.019) | 0.684 (0.057) | 0.837 (0.041) | 0.838 (0.040) |

| abSNF | 0.964 (0.024) | 0.639 (0.059) | 0.679 (0.061) | 0.659 (0.056) | ||

| CIMLR | 0.438 (0.035) | 0.214 (0.049) | 0.364 (0.037) | 0.362 (0.037) | ||

| SNF | 0.414 (0.044) | 0.249 (0.038) | 0.353 (0.034) | 0.352 (0.035) | ||

| 5% | wMKL | 0.997 (0.008) | 0.870 (0.036) | 0.945 (0.027) | 0.939 (0.028) | |

| abSNF | 0.989 (0.013) | 0.825 (0.047) | 0.864 (0.051) | 0.827 (0.062) | ||

| CIMLR | 0.706 (0.056) | 0.409 (0.034) | 0.453 (0.029) | 0.451 (0.028) | ||

| SNF | 0.719 (0.056) | 0.382 (0.043) | 0.461 (0.035) | 0.459 (0.034) | ||

| 10% | wMKL | 1.000 (0.001) | 0.959 (0.023) | 0.984 (0.017) | 0.980 (0.019) | |

| abSNF | 0.997 (0.008) | 0.935 (0.032) | 0.961 (0.026) | 0.944 (0.031) | ||

| CIMLR | 0.964 (0.023) | 0.629 (0.049) | 0.663 (0.057) | 0.643 (0.052) | ||

| SNF | 0.908 (0.057) | 0.615 (0.043) | 0.615 (0.039) | 0.607 (0.036) |

The table lists the NMI of different methods under different levels of noise intensity in Scenario I. Values in parentheses are standard deviations. A larger NMI indicates better performance. For a given noise level, the one(s) with the best performance is(are) highlighted in bold fonts. Sign% stands for the percentage of signal features; Low- and high-within noise represents low and high noise levels within each data type; Low- and high-cross noise represents low and high noise across different data types.

Table 2 shows the accuracy rate in estimating the subtype groups in Scenario I. The result for Scenario II is rendered in Table S2 in the Supplementary Materials. The estimation of subtype numbers is a key issue in disease classification. wMKL can correctly estimate the true number in most settings of the two simulation scenarios. Except for the high-within-data noise level with weak signal strength (2.5% signal features), wMKL has an accuracy rate of at least 62.4%, and up to 100% for 10% signal strength in Scenario I, while other methods almost fail to estimate the true subtype groups in all settings under the two scenarios.

Table 2.

Estimation of the number of subtypes in simulation Scenario I.

| Method | 2.5% signal feature | 5% signal feature | 10% signal feature | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | ≥5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ≥5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ≥5 | ||

| SimData1 | |||||||||||||

| Low-within noise | wMKL | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| abSNF | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CIMLR | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33.2 | 66.8 | 0 | |

| SNF | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| High-within noise | wMKL | 85.2 | 14.1 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 33.5 | 62.4 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.2 | 99.8 | 0 |

| abSNF | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CIMLR | 99.8 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| SNF | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Low-cross noise | wMKL | 0.2 | 12.9 | 83.8 | 3.11 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| abSNF | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CIMLR | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 99.3 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | |

| SNF | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| High-cross noise | wMKL | 0.1 | 18.1 | 79.2 | 2.61 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| abSNF | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CIMLR | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 98.9 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | |

| SNF | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| SimData2 | |||||||||||||

| Low-within noise | wMKL | 0 | 0 | 99.6 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 96.3 | 3.7 | 0 | 0 | 73.6 | 26.4 |

| abSNF | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CIMLR | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 63.1 | 10.3 | 26.5 | 0.1 | |

| SNF | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| High-within noise | wMKL | 98.1 | 1.9 | 0 | 0 | 60.9 | 20.8 | 17.4 | 0.9 | 0 | 1.1 | 98.9 | 0 |

| abSNF | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CIMLR | 98.1 | 0.9 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| SNF | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Low-cross noise | wMKL | 32.7 | 14.7 | 46.8 | 5.72 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 85.1 | 13.4 | 0 | 0 | 63 | 37 |

| abSNF | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CIMLR | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| SNF | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| High-cross noise | wMKL | 28.9 | 18 | 46.8 | 6.3 | 0.3 | 2.1 | 84.8 | 12.8 | 0 | 0 | 64.2 | 35.8 |

| abSNF | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CIMLR | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| SNF | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

The table lists the proportion of the estimated subtype groups (2, 3, 4, ≥5) out of 1000 simulation runs under different noise levels and signal strengths in Scenario I. The true simulated number of subtypes is 4. The best number of clusters for wMKL and CIMLR is based on the separation cost criterion, while it is based on the eigengap criterion for abSNF and SNF. In all the cases, abSNF, CIMLR and SNF all underestimate the true number of subtypes.

Overall, wMKL is robust and outperforms the current state-of-the-art competitors in terms of clustering accuracy and robustness. With fuzzy boundaries in SimData2 data, the performance of all methods slightly decreases; but wMKL still performs better than others, with a consistent trend as shown for SimData1.

Overall subtyping performance of PRCC and LUAD

We compared the performance of wMKL with other methods in cancer subtyping using two cancer datasets, PRCC and LUAD, downloaded from the TCGA website. Three data types were considered: miRNA expression, mRNA expression and promoter CpG methylation. We evaluated the subtypes identified by wMKL based on commonly used measures: (1) P-value in log-rank test to evaluate the difference of survival curves between subtypes; and (2) significant difference in pathway activity between subtypes (see Table 3 and Table S3 in the Supplementary Materials). For the survival analysis, patients who died within 30 days or were over 80 years old at the beginning of the observation period were censored. Overall survival was considered, with a time interval of 10 years for PRCC, whereas LUAD with a time interval of 5 years for a low survival rate. A log-rank test was used to evaluate the significance of the difference in survival profiles between subtypes. We compared the performance of wMKL using all three data types in comparison with using a single data type, and also compared wMKL with the boosted ab-SNF method [11], as well as the non-boosted subtyping strategies (e.g., SNF [4] and CIMLR [9]).

Table 3.

Comparison of wMKL with other subtyping methods.

| Cancer | wMKL (single miRNA) | wMKL (single mRNA) | wMKL (single methya) | wMKL | ab-SNF | CIMLR | SNF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRCC | 3 (0.22)b | 4 (0.01) | 5 (0.01) | 3 (4.41E-4) | 2 (0.06) | 3 (0.02) | 3 (1.04E-3) |

| LUAD | 6 (0.25) | 4 (0.65) | 3 (0.33) | 3 (6.04E-3) | 2 (0.02) | 3 (0.03) | 2 (0.14) |

amethy stands for promoter CpG methylation.

bListed are the number of subtypes and the log-rank test P-value in the parentheses. For wMKL and CIMLR, the number of subtypes was determined based on the separation cost, while the number of subtypes for ab-SNF and SNF was determined by Eigengap. Among the results, wMKL achieves the smallest prognostic P-value.

Based on the separation cost criterion, wMKL identified 3 PRCC subtypes which show significant differences in survival (P-value = 4.41 × 10−4) and 3 LUAD subtypes (P-value = 6.04 × 10−3) (see Table 3; Figs. 2a and 3a). Compared to the analysis using single data and three other integration methods, wMKL has the smallest log-rank P-value. Additionally, the subtypes obtained with wMKL show significant differences in pathway activity in 10 and 14 of the 14 signalling pathways for PRCC and LUAD, respectively (see Table S3 in the Supplementary Materials). Overall, wMKL outperformed all the compared methods in the two datasets (Table 3 and Table S3 in the Supplementary Materials), consistent with the simulation results.

Fig. 2. Clustering results of PRCC.

a Plot of separation cost (y-axis) showing 3 as the optimal number of clusters. b 2-D visualisation of the 3 subtypes. c Kaplan–Meier curves of the 3 subtypes identified by wMKL; OS=overall survival. d Boxplot of average promoter methylation -values (y-axis) across 3 subtypes. e Heatmap of selected clinical and differential enriched molecular features across the 3 subtypes. The differential methylation features are clustered into two subclusters, namely Methylation-cluster 1 and Methylation-cluster 2. Each column represents a patient.

Fig. 3. Clustering results of LUAD.

a Plot of separation cost (y-axis) showing 3 as the optimal number of clusters. b 2-D visualisation of the 3 subtypes. c Kaplan–Meier curves of the 3 subtypes identified by wMKL; OS=overall survival. d Heatmap of selected clinical and differential enriched molecular features across the 3 subtypes. The differential mRNA features are clustered into two subclusters, namely mRNAs-cluster 1 and mRNAs-cluster 2. Each column represents a patient.

With several kernels in each data type, wMKL can effectively alleviate the suffered sensitivity issue when choosing kernel parameters in weighted modelling. The learned kernel weights based on each data type can further account for the different contributions of each data type. The contributions of miRNA, mRNA expression and DNA methylation were similar for both PRCC and LUAD. Compared with CIMLR, wMKL captures more contribution from miRNA expression (Fig. S4 in the Supplementary Materials). Thus, we can tell which data type contributes more to molecular subtyping. In the following, we provided the detailed results for analysing the two cancer datasets.

Analysis of PRCC subtypes identified by wMKL

Papillary renal cell carcinoma (PRCC) is a heterogeneous disease with histologic subtypes and variations in disease progression and survival outcomes, accounting for 15% to 20% of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) [33]. PRCC is usually subdivided into two types (type I and type II) based on histological criteria, where type II is more heterogeneous and aggressive, and is also associated with poor prognosis [34]. Up to now, there is still no effective therapeutic remedy available for patients in an advanced stage of PRCC [35]. It becomes increasingly important for further molecular subtyping to provide a better understanding of the molecular characterisations for accurate tumour classification and developing novel targeted therapies.

wMKL identified 3 PRCC subtypes with strong separation (Fig. 2a) and significant differences in overall survival and related biological changes (Fig. 2b–e and Table S3 in the Supplementary Materials). Patients in subtype 2 and subtype 3 are predominantly type II PRCC, while subtype 1 is predominantly type I PRCC (Fig. 2e and Table S4 in the Supplementary Materials). Subtype 2 and subtype 3 have no difference in terms of tumour type (Table S4 in the Supplementary Materials), but show significant differences in survival, and subtype 3 (21 patients) has the worst survival outcome. A total of 62 differentially expressed miRNAs, 2184 expressed mRNAs and 2508 promoter methylations were identified (Fig. 2e). Subtypes identified by wMKL showed significantly different activities in 10 out of 14 pathways, while 6 pathways showed significant differences among subtypes identified by abSNF (Table S3 in the Supplementary Materials). To get further insight into the molecular characteristics, we examined each subtype separately.

Subtype 1 is dominated by type I tumour, enriched in 3 up-regulated mRNAs, 1464 hypomethylation promoters and 792 hypermethylation promoters. Subtype 2, as the dominant type II tumour, has 3 downregulated mRNAs, 3 hypomethylation promoters and 47 hypermethylation promoters. Subtype 3 has the worst survival outcome, characterised by the dominated type II tumour. Subtype 2 and subtype 3 share two common hypermethylation promoters (cg16198130 and cg10112265). All 62 differentially expressed miRNAs are enriched in subtype 3, including 57 downregulated miRNAs and 5 up-regulated miRNAs, of which hsa-mir-192 and hsa-mir-194 are downregulated in metastatic RCC [36]. Most of the deregulated mRNAs are enriched in subtype 3, among which 1301 are downregulated and 880 are up-regulated, including USH1C, which is associated with poor survival in patients with RCC [37]. Subtype 3 is also characterised by overall high DNA methylation (Fig. 2d), enriched in 43 hypomethylated and 170 hypermethylated promoters. Subtype 3 has the highest activity in 6 pathways (PI3K, MAPK, EGFR, Androgen, TGFb and Hypoxia), and has the lowest activity in Trail pathways (see Fig. S5 in the Supplementary Materials). MAPK signalling pathway plays an essential role in cell proliferation and differentiation, and the activation of MAPK signalling pathway in tumorigenesis, metastasis, and angiogenesis was reported in RCC [38]. EGFR is a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor encoded by a gene on chromosome 7 and involved in cell proliferation and migration, and overexpression of EGFR has been frequently found in PRCC; thus the EGFR pathway has been explored as a potential therapeutic target in PRCC [39, 40]. Trail, as a member of the tumour necrosis factor ligand family that selectively induces apoptosis of cancer cells, is important in host tumour surveillance and metastasis suppression [41, 42]. We argued that low activity in the Trail signalling pathway might result in a worse prognosis for subtype 3 than subtype 2, and may offer the potential to develop Trail receptor agonists as anticancer therapeutics. Subtype 3 is highly CD8 + T cell infiltrated (see Fig. S6a in the Supplementary Materials). Reports showed that high tumour infiltration by CD8 + T cells is associated with a worse prognosis in RCC [43], further demonstrating its prognostic value.

The two methylation clusters, namely Methylation-cluster 1 and Methylation-cluster 2 (Fig. 2e), contain 2508 promoters, among which 1668 are in cluster 1 and 840 are in cluster 2. Cluster 1 displays hypermethylation for dominated type II tumours, in particular for subtype 3, while cluster 2 displays are hypomethylated for dominated type II tumours. We performed KEGG pathway analysis for genes in these two clusters. Those in Methylation-cluster 1 are enriched in 57 significant pathways (BH FDR-adjusted P-value < 0.05), while genes in Methylation-cluster 2 are enriched in 75 pathways. Fig. S7 in the Supplementary Materials shows the top 20 pathways with P-values for the two clusters. Cluster 1 is significantly enriched in the cell proliferation and differentiation-related pathways, including the Wnt signalling pathway, PI3K-Akt signalling pathway and MAPK signalling pathway, indicating crucial functional roles in tumour development and growth. Cluster 2 is significantly enriched in immune recognition-related pathways, including Allograft rejection, B cell receptor signalling pathway and Platelet activation, highlighting the immune evasion mechanisms adopted by modification of surface antigens [44].

For a given Type II PRCC patient, we built supervised classification models to distinguish subtype 2 and subtype 3 with the differential features enriched in these two subtypes using six machine-learning methods, namely GA-KPLS, random forest, LASSO, ridge regression, SVM and neural network. A total of 106 dominated type II PRCC patients were analysed, among which 85 are subtype 2 patients and 21 are subtype 3 patients, along with 62 deregulated miRNAs, 2184 deregulated mRNAs, and 261 methylation promoters. The response is a dichotomous variable, with +1 representing subtype 2 patients and −1 representing subtype 3 patients. All six methods can accurately predict the two subtypes, with more than 95% of the AUC for Random forest, LASSO and GA-fKPLS (Table 4). The results demonstrate that differential features discovered followed by wMKL can accurately classify the heterogeneous type II PRCC, providing novel biomarkers to stratify the type II PRCC and better guide clinical treatment.

Table 4.

Classification performance for Type II PRCC using six machine-learning methods.

| Model | AUC | Se | Sp | ACC | Youden | F-measure | MCC | G-means |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVM | 0.923 | 0.987 | 0.859 | 0.963 | 0.846 | 0.976 | 0.886 | 0.910 |

| Random forest | 0.962 | 0.989 | 0.935 | 0.979 | 0.924 | 0.987 | 0.937 | 0.957 |

| LASSO | 0.962 | 0.999 | 0.926 | 0.985 | 0.924 | 0.991 | 0.948 | 0.956 |

| Ridge regression | 0.949 | 1.000 | 0.899 | 0.981 | 0.899 | 0.989 | 0.934 | 0.942 |

| Neural network | 0.917 | 0.923 | 0.911 | 0.920 | 0.833 | 0.949 | 0.783 | 0.912 |

| GA-fKPLS | 0.958 | 0.995 | 0.920 | 0.981 | 0.915 | 0.988 | 0.939 | 0.952 |

We further explored the interactions and regulations of different data types based on the differential features. We evaluated how deregulated miRNAs and aberrant methylations affect gene expression. The scatter plots of the first canonical variate pair between mRNA and miRNA/methylation are shown in Fig. 4a, b. Similar correlations are observed within each subtype (Fig. 4c), indicating the impact of miRNA and aberrant methylation on gene deregulation. Figure 4d shows the number of differential features in each omics data type and the overlapping ones. A total of 223 genes are targeted by hsa-mir-3170 and hsa-mir-378c. The correlations of the top 7 miRNA and mRNA pairs and the top 20 methylation and mRNA pairs are shown in Fig. 4e within each subtype. Strong negative correlations are observed between methylation and mRNA, in particular in subtype 3.

Fig. 4. Correlation analysis of differential features between miRNA and mRNA and between methylation and mRNA for PRCC.

a Scatter plot of the first canonical variate pair between mRNAs and miRNAs. b Scatter plot of the first canonical variate pair between mRNAs and methylations. c Plot of the first canonical correlation in all subjects and in each subtype separately. d Number of differential deregulated mRNAs, mRNAs targeted by miRNAs, and genes with aberrant methylation across the three subtypes. e Correlation of the top 7 overlapped genes between mRNA and miRNA (indicating positive miRNA regulation of gene expression), and the top 20 overlapped genes between mRNA and methylation, across the 3 subtypes (indicating gene downregulation due to promoter methylation).

The upregulation of C8orf58 expression by hsa-mir-3170 is found in subtype 3 with a correlation of 0.48 (Fig. 4e and Fig. S8a in the Supplementary Materials). Most of the overlapped genes undergoing DNA methylation changes are inversely correlated with gene expression, in particular in subtype 3, leading to tumour development and progression, which may explain the poor prognosis of dominated type II PRCC. Among the genes, SULT1C4, NPR2 and USH1C have a high negative correlation in subtype 3 (−0.84, −0.84 and −0.81) (Fig. 4e and Fig. S8b–d in the Supplementary Materials). Changes in SULT1C4 expression might be caused by aberrant methylation in RCC cell lines [45], whereas NRP2 has a clinically significant role in cancer cell extravasation and promotion of metastasis [46]. The downregulation of USH1C expression has been reported to be associated with malignant grade and metastases of RCC [37, 47]. The expression of SPON2 and MUC13 shows a significant negative correlation with DNA methylation in all the 3 subtypes, indicating a broad-spectrum correlated effect in PRCC.

We further evaluated the functional relevance of the 217 overlapped genes in aberrant DNA methylations and deregulated mRNAs by KEGG pathway analysis. A total of 13 pathways were identified (BH FDR corrected P-value < 0.05) (see Fig. S9 in the Supplementary Materials), with 42 genes involved in metabolic pathways, including NAPRT, NPR2, PDE1A, B3GNT3, FUT6, PDE1C and CKB. These genes show a high negative correlation between DNA methylation and gene expression in subtype 3 (Fig. 4e), indicating the role of aberrant promoter methylation on gene expression. Among the genes, the downregulation of FUT6 is observed in subtype 3 with DNA methylation (correlation −0.76) (Fig. 4e and Fig. S8e in the Supplementary Materials). Study shows that the transcript level of gene FUT6 is significantly lowered in RCC tissues, offering new mechanistic insight into the glycobiology underpinning kidney malignancies [48].

Analysis of LUAD subtypes identified by wMKL

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide [49], with smoking as the leading risk factor. Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) is the most common histological subtype of primary lung cancer. LUAD cancers are heterogeneous in biological and clinical phenotypes. LUAD can be classified into three subtypes based on clinical data including terminal respiratory unit, proximal-proliferative, and proximal-inflammatory [50]. They were formerly referred to as bronchioid, magnoid, and squamoid subtypes [51]. Despite the increasing understanding of LUAD pathogenesis and the development of new treatments, LUAD still remains as one of the most aggressive and rapidly fatal tumour types, with an average 5-year survival rate of 15.9% [52, 53].

The 360 LUAD patients were divided into 3 subtypes with strong separation (Fig. 3a, b). The 3 subtypes are significantly different in overall survival and the related biological changes (Fig. 3c, d; and Table S3 and S5 in the Supplementary Materials). Subtype 1 with 127 subjects is the worst survival subtype. A total of 6 differentially expressed miRNAs, 121 differentially expressed mRNAs, and 800 aberrant promoter methylations are identified (Fig. 3d). All the 14 pathway activities show significant differences among the three wMKL-derived subtypes, while 12 pathways show differences among the abSNF-derived subtypes (Table S3 in the Supplementary Materials). Next, we focus on the wMKL-derived subtypes for further analysis.

Subtype 1 is the worst survival subtype, enriched in 23 up-regulated and 22 downregulated mRNAs. PFN2, one of the up-regulated mRNAs, has been reported as an invasion biomarker in lung cancer, promoting invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal-transition in non-small cell lung cancer [54]. Subtype 1 is also enriched by 372 hypomethylation promoters and 34 hypermethylation promoters, and is characterised by the highest activity in PI3K, Oestrogen and Hypoxia pathway, and the lowest activity in Trail, p53, Androgen, JAK-STAT and TGFb (Fig. S10 in the Supplementary Materials), providing new insights into the deregulated cell proliferation and survival. Among these, PI3K signalling is stimulated by diverse oncogenes and growth factor receptors. Increased PI3K signalling is considered as a hallmark of cancer [55]. Meanwhile, subtype 1 has low infiltration for all six types of immune cells with the TIMER algorithm (Fig. S6b in the Supplementary Materials), especially for CD4 T-cell and Myeloid dendritic cells. Dendritic cells are reported as the key factors that provide protective immunity against lung tumours. The reduced function of these pathways in subtype 1 further explains why patients with low infiltration have distinctly worse cancer-specific overall survival [56].

Subtype 2 is enriched in 207 abnormal promoter methylations, among which one promoter (cg07826859) is hypomethylated and 206 promoters are hypermethylated. Mediated by smoking, cg07826859 has been reported to play a key role in the formation of chronic inflammation via regulating the activity of T cells [57]. Subtype 2 shares 69 abnormal promoter methylations with subtype 3.

Subtype 3 is enriched in 6 up-regulated miRNAs in which hsa-mir-145 and hsa-mir-140 play inhibition roles in lung cancer cells [58, 59], providing therapeutic targets for the treatment of LUAD patients. Thirty-five downregulated mRNAs and 64 up-regulated mRNAs are enriched in subtype 3. Among these, ABI3BP is a potential biomarker of lung cancer [60], and upregulation of ABI3BP in gallbladder cancer has been reported to suppress the development of gallbladder cancer [61]. Subtype 3 has 38 hypomethylated and 221 hypermethylated promoters, and is characterised by the highest activity in Androgen, p53, Trail and WNT pathway and lowest activity in PI3K and EGFR (Fig. S10 in the Supplementary Materials). EGFR signalling activation contributes to malignancy and correlates with poor prognosis. Inhibiting EGFR signalling has played a central role in lung cancer treatment [62]. Subtype 3 is also characterised by fewer smokers than the other two subtypes.

We further explored the functional relevance of deregulated mRNAs, all of which are clustered into two clusters, namely mRNAs-cluster 1 (85 mRNAs) and mRNAs-cluster 2 (36 mRNAs) (Fig. 3d). The gene set in mRNAs-cluster 1 is enriched in 10 significant pathways (BH FDR corrected P-value < 0.05) (Fig. S11a in the Supplementary Materials), while gene set in mRNAs-cluster 2 is enriched in 6 significant pathways (Fig. S11b in the Supplementary Materials). Genes involved in Tight junction are CD1A, CD1C, CD1E, CLDN18, and SYNPO, among which genes CD1A, CD1C, CD1E from the CD1 family members are downregulated in subtype 1, and were shown as diagnostic and prognostic markers for LUAD [63–65]. Based on the enriched promoter methylations which are mapped into 709 genes, 5 pathways are identified, including the PI3K-Akt signalling pathway (Fig. S12 in the Supplementary Materials). The PI3K-AKT signalling pathway, an oncogenic pathway, functions in cancer initiation and progression. The activation of this pathway by several inhibitors was reported in LUAD [66].

Compared to the previously identified subtypes for LUAD [9, 50], wMKL separates LUAD cancers into 3 different novel subtypes with strong separation and significant differences in survival time. The identified worst survival subtype has distinguishing characteristics, providing additional clinical and biological insights for LUAD.

Discussion

The importance of incorporating prior disease-associated molecular data into the subtyping procedure has been broadly recognised. We proposed a novel method, wMKL, to integrate multi-omics data by incorporating flexible weight functions to improve disease subtyping. wMKL overcomes many of the limitations of current integrative subtyping algorithms, outperforming the weighted methods and non-weighted methods in terms of clustering accuracy and robustness. The utility and advantage of wMKL are illustrated through extensive simulations and applications to two TCGA datasets.

Our approach is novel in several aspects. First, it directly incorporates prior feature-level weights in the construction of kernel similarities. As a result, signal features are up-weighted whereas the null features are down-weighted, leading to an improved subtyping accuracy. In addition, wMKL allows for the incorporation of multiple flexible weight functions by combing different weight-related P-values using the Cauchy combination method. In our study, we considered features that not only boost subtype identification but also ensure the prognostically significant difference in subtypes as potential signal features. Users can define other types of weight functions. For example, with the interest of survival outcomes, one could use the survival outcome guided weights, such as the log-hazard ratio estimated from univariate Cox regression. By borrowing relevant biological and clinical information to construct the weight function, the subtyping results by wMKL are more biologically and clinically meaningful. Second, wMKL uses several kernels to model each data type and thereby alleviates the burden of user choice for best kernel parameters, and addresses the issue of suffered sensitivity in kernel parameter selection in weighted modelling. It models sample similarity by combing all weighted kernels from each data type in an unsupervised framework, and can efficiently capture complementary information embedded in each data type, solving a challenging issue in kernel-based unsupervised subtyping without label information.

In an application to two independent TCGA cancer types (PRCC and LUAD), wMKL identified subtypes with meaningful biological interpretation following intensive downstream statistical and bioinformatics analysis, compared to the ones obtained with single data type and other integration methods. The discovered subtypes exhibit significant differences in gene enrichment, cancer-related biological pathways and immune cell infiltration, further confirming the advantage of wMKL in integrative subtyping by providing valuable biological insights into clinical decision-making.

Clinically, PRCC is classified into two different types, type I and type II. In a previous study, type II PRCC was classified into three subtypes using a consensus clustering method [33], while wMKL classified most type II PRCC into two subtypes, namely subtypes 2 and 3. Subtype 3 is consisted of the smallest proportion of patients (10.14%), but has the worst survival among the 3 subtypes. Based on the differential omics features, various prediction models can accurately predict subtype 2 and subtype 3 in type II PRCC patients (Table 4). This implies that the PRCC subtypes identified by wMKL are clinically meaningful, providing further insights into PRCC progression. For LUAD, compared with subtypes identified with other methods, wMKL obtained better performance in terms of survival separability. The worst survival subtype has distinct molecular characteristics compared to other subtypes, providing meaningful characteristics for the development of novel targeted therapies.

Undoubtedly, there are several limitations that should be acknowledged in this study. The wMKL method proposed herein is a multi-kernel-learning approach that accounts for intra-interaction effects within the same omics data; however, it does not possess the capability to identify relationships between different types of omics data. Extending this method incorporating omics-omics interaction information within the subtyping context represents a promising avenue for future exploration. Furthermore, our validation process, relying primarily on extensive simulation studies, precluded evaluations across all TCGA datasets. Instead, the application was focused on two cancer datasets, specifically PRCC and LUAD, to illustrate the method’s performance (also due to space limitations). A more comprehensive analysis encompassing a wider array of cancer datasets from the TCGA database, including breast cancer (BRCA), could offer deeper insights into the method’s performance within the context of tumour subtyping.

In conclusion, our proposed wMKL is capable of adapting to a broad spectrum of prior weights for multi-omics data integration, and achieves robust and high accuracy of subtype identification, providing a novel computational tool for cancer subtype discovery. With the availability of more omics data as well as other data modalities (e.g., image data), wMKL will be a useful tool to facilitate patient stratification for accurate treatment and early intervention, which is of great importance for preventing the occurrence and development of cancer metastases. wMKL can also be applied to single-cell RNA-seq data to identify novel cell types.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to an associate editor and three anonymous reviewers for their valuable insights and constructive feedback, which significantly contributed to the enhancement of this paper.

Author contributions

HC and YC designed the study; HC performed simulations and real data analysis with assistance from CJ, ZL, HY, YZ and YC; HC developed the software tool with assistance from RF; HC and YC wrote the manuscript with input from all other authors. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

HC was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71403156), the Fundamental Research Programme of Shanxi Province (202303021211130), China Scholarship Council (No.201908140151), Startup Foundation for Doctors of Shanxi Medical University (BS201722). HY was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81872717). YC was supported by the Michigan State University.

Data availability

The TCGA data analysed in this study can be accessed through the Genomic Data Commons Data Portal (http://cancergenome.nih.gov/). The wMKL is implemented in the R package wMKL, freely available on GitHub (https://github.com/biostatcao/wMKL).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41416-024-02587-w.

References

- 1.Rappoport N, Shamir R. Multi-omic and multi-view clustering algorithms: review and cancer benchmark. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:10546–62. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu D, Wang D, Zhang MQ, Gu J. Fast dimension reduction and integrative clustering of multi-omics data using low-rank approximation: application to cancer molecular classification. BMC Genom. 2015;16:1022. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2223-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen T, Tagett R, Diaz D, Draghici S. A novel approach for data integration and disease subtyping. Genome Res. 2017;27:2025–39. doi: 10.1101/gr.215129.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang B, Mezlini AM, Demir F, Fiume M, Tu Z, Brudno M, et al. Similarity network fusion for aggregating data types on a genomic scale. Nat Method. 2014;11:333. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Speicher NK, Pfeifer N. Integrating different data types by regularized unsupervised multiple kernel learning with application to cancer subtype discovery. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:i268–75. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Röder B, Kersten N, Herr M, Speicher NK, Pfeifer N. web-rMKL: a web server for dimensionality reduction and sample clustering of multi-view data based on unsupervised multiple kernel learning. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W605–09. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lock EF, Hoadley KA, Marron JS, Nobel AB. Joint and individual variation explained (JIVE) for integrated analysis of multiple data types. Ann Appl Stat. 2013;7:523. doi: 10.1214/12-AOAS597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen R, Olshen AB, Ladanyi M. Integrative clustering of multiple genomic data types using a joint latent variable model with application to breast and lung cancer subtype analysis. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2906–12. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramazzotti D, Lal A, Wang B, Batzoglou S, Sidow A. Multi-omic tumor data reveal diversity of molecular mechanisms that correlate with survival. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06921-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu T, Le TD, Liu L, Wang R, Sun B, Li J. Identifying cancer subtypes from miRNA-tf-mRNA regulatory networks and expression data. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0152792. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruan P, Wang Y, Shen R, Wang S. Using association signal annotations to boost similarity network fusion. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:3718–26. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coretto P, Serra A, Tagliaferri R. Robust clustering of noisy high-dimensional gene expression data for patients subtyping. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:4064–72. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arora A, Olshen AB, Seshan VE, Shen R. Pan-cancer identification of clinically relevant genomic subtypes using outcome-weighted integrative clustering. Genome Med. 2020;12:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13073-020-00804-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang B, Zhu J, Pierson E, Ramazzotti D, Batzoglou S. Visualization and analysis of single-cell RNA-seq data by kernel-based similarity learning. Nat Method. 2017;14:414–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y, Xie J. Cauchy combination test: a powerful test with analytic p-value calculation under arbitrary dependency structures. J Am Stat Assoc. 2020;115:393–402. doi: 10.1080/01621459.2018.1554485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ng A, Jordan M, Weiss Y. On spectral clustering: analysis and an algorithm. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2002;14:849–56. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Von Luxburg U. A tutorial on spectral clustering. Stat Comput. 2007;17:395–416. doi: 10.1007/s11222-007-9033-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu A, Chen J, Peng H, Han G, Cai H. Simultaneous interrogation of cancer omics to identify subtypes with significant clinical differences. Front Genet. 2019;10:236. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi Q, Zhang C, Peng M, Yu X, Zeng T, Liu J, et al. Pattern fusion analysis by adaptive alignment of multiple heterogeneous omics data. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:2706–14. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conway K, Edmiston SN, Tse CK, Bryant C, Kuan PF, Hair BY, et al. Racial variation in breast tumor promoter methylation in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomark. 2015;24:921–30. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimomura A, Shiino S, Kawauchi J, Takizawa S, Sakamoto H, Matsuzaki J, et al. Novel combination of serum microRNA for detecting breast cancer in the early stage. Cancer Sci. 2016;107:326–34. doi: 10.1111/cas.12880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakagawa T, Kollmeyer TM, Morlan BW, Anderson SK, Bergstralh EJ, Davis BJ, et al. A tissue biomarker panel predicting systemic progression after PSA recurrence post-definitive prostate cancer therapy. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2318. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colaprico A, Silva TC, Olsen C, Garofano L, Cava C, Garolini D, et al. TCGAbiolinks: an R/Bioconductor package for integrative analysis of TCGA data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:e71. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gusev A, Lee SH, Trynka G, Finucane H, Vilhjálmsson BJ, Xu H, et al. Partitioning heritability of regulatory and cell-type-specific variants across 11 common diseases. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;95:535–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Troyanskaya O, Cantor M, Sherlock G, Brown P, Hastie T, Tibshirani R, et al. Missing value estimation methods for DNA microarrays. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:520–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.6.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang H, Cao H, He T, Wang T, Cui Y. Multilevel heterogeneous omics data integration with kernel fusion. Brief Bioinformatics. 2020;21:156–70. doi: 10.1093/bib/bby115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Witten DM, Tibshirani R, Hastie T. A penalized matrix decomposition, with applications to sparse principal components and canonical correlation analysis. Biostatistics. 2009;10:515–34. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxp008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliveros JC (2007–2015). Venny. An interactive tool for comparing lists with Venn’s diagrams, https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html. 2007–2015

- 29.Huang HY, Lin YC, Li J, Huang KY, Shrestha S, Hong HC, et al. miRTarBase 2020: updates to the experimentally validated microRNA–target interaction database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:D148–54. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schubert M, Klinger B, Klünemann M, Sieber A, Uhlitz F, Sauer S, et al. Perturbation-response genes reveal signaling footprints in cancer gene expression. Nat Commun. 2018;9:20. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02391-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li T, Fu J, Zeng Z, Cohen D, Li J, Chen Q, et al. TIMER2.0 for analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:W509–14. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xie C, Mao X, Huang J, Ding Y, Wu J, Dong S, et al. KOBAS 2.0: a web server for annotation and identification of enriched pathways and diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W316–22. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of papillary renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:135–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krawczyk KM, Nilsson H, Allaoui R, Lindgren D, Arvidsson M, Leandersson K, et al. Papillary renal cell carcinoma-derived chemerin, IL-8, and CXCL16 promote monocyte recruitment and differentiation into foam-cell macrophages. Lab Investig. 2017;97:1296–305. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2017.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh NP, Vinod P. Integrative analysis of DNA methylation and gene expression in papillary renal cell carcinoma. Mol Genet Genom. 2020;295:807–24. doi: 10.1007/s00438-020-01664-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khella H, Bakhet M, Allo G, Jewett M, Girgis A, Latif A, et al. miR-192, miR-194 and miR-215: a convergent microRNA network suppressing tumor progression in renal cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:2231–9. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen SC, Chen FW, Hsu YL, Kuo PL. Systematic analysis of transcriptomic profile of renal cell carcinoma under long-term hypoxia using next-generation sequencing and bioinformatics. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:2657. doi: 10.3390/ijms18122657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang D, Ding Y, Luo WM, Bender S, Qian CN, Kort E, et al. Inhibition of MAPK kinase signaling pathways suppressed renal cell carcinoma growth and angiogenesis in vivo. Cancer Res. 2008;68:81–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Courthod G, Tucci M, Di Maio M, Scagliotti GV. Papillary renal cell carcinoma: a review of the current therapeutic landscape. Crit Rev Oncol/Hematol. 2015;96:100–12. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Twardowski PW, Mack PC, Lara PN., Jr Papillary renal cell carcinoma: current progress and future directions. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2014;12:74–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mizutani Y, Nakanishi H, Yoshida O, Fukushima M, Bonavida B, Miki T. Potentiation of the sensitivity of renal cell carcinoma cells to TRAIL-mediated apoptosis by subtoxic concentrations of 5-fluorouracil. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:167–76. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(01)00339-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thorburn A. Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) pathway signaling. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:461–5. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31805fea64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Braun DA, Hou Y, Bakouny Z, Ficial M, Sant’Angelo M, Forman J, et al. Interplay of somatic alterations and immune infiltration modulates response to PD-1 blockade in advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nat Med. 2020;26:909–18. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0839-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang M, Zhang C, Song Y, Wang Z, Wang Y, Luo F, et al. Mechanism of immune evasion in breast cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:1561. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S126424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feng H, Zhang Y, Liu K, Zhu Y, Yang Z, Zhang X, et al. Intrinsic gene changes determine the successful establishment of stable renal cancer cell lines from tumor tissue. Int J Cancer. 2017;140:2526–34. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cao Y, Hoeppner LH, Bach S, Guangqi E, Guo Y, Wang E, et al. Neuropilin-2 promotes extravasation and metastasis by interacting with endothelial α5 integrin. Cancer Res. 2013;73:4579–90. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Braga EA, Fridman MV, Loginov VI, Dmitriev AA, Morozov SG. Molecular mechanisms in clear cell renal cell carcinoma: role of miRNAs and hypermethylated miRNA genes in crucial oncogenic pathways and processes. Front Genet. 2019;10:320. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Drake RR, McDowell C, West C, David F, Powers TW, Nowling T, et al. Defining the human kidney N‐glycome in normal and cancer tissues using MALDI imaging mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom. 2020;55:e4490. doi: 10.1002/jms.4490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;511:543–50. doi: 10.1038/nature13385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilkerson MD, Yin X, Walter V, Zhao N, Cabanski CR, Hayward MC, et al. Differential pathogenesis of lung adenocarcinoma subtypes involving sequence mutations, copy number, chromosomal instability, and methylation. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e36530. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Denisenko TV, Budkevich IN, Zhivotovsky B. Cell death-based treatment of lung adenocarcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:117. doi: 10.1038/s41419-017-0063-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu F, Chen J, Yang X, Hong X, Li Z, Lin L, et al. Analysis of lung adenocarcinoma subtypes based on immune signatures identifies clinical implications for cancer therapy. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2020;17:241–9. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yan J, Ma C, Gao Y. MicroRNA-30a-5p suppresses epithelial-mesenchymal transition by targeting profilin-2 in high invasive non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. Oncol Rep. 2017;37:3146–54. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fruman DA, Chiu H, Hopkins BD, Bagrodia S, Cantley LC, Abraham RT. The PI3K pathway in human disease. Cell. 2017;170:605–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang JB, Huang X, Li FR. Impaired dendritic cell functions in lung cancer: a review of recent advances and future perspectives. Cancer Commun. 2019;39:43. doi: 10.1186/s40880-019-0387-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gao X, Zhang Y, Saum KU, Schöttker B, Breitling LP, Brenner H. Tobacco smoking and smoking-related DNA methylation are associated with the development of frailty among older adults. Epigenetics. 2017;12:149–56. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2016.1271855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cho WC, Chow AS, Au JS. MiR-145 inhibits cell proliferation of human lung adenocarcinoma by targeting EGFR and NUDT1. RNA Biol. 2011;8:125–31. doi: 10.4161/rna.8.1.14259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Flamini V, Dudley E, Jiang WG, Cui Y. Distinct mechanisms by which two forms of miR-140 suppress the malignant properties of lung cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2018;9:36474–91. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Han LK, Huai QL, Guo W, Song P, Kong DM, Gao SG, et al. Identification of prognostic genes in lung adenocarcinoma immune microenvironment. Chin Med J. 2021;134:2125–7. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000001367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lin N, Yao Z, Xu M, Chen J, Lu Y, Yuan L, et al. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 potentiates growth and inhibits senescence by antagonizing ABI3BP in gallbladder cancer cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38:244. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1237-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morello V, Cabodi S, Sigismund S, Camacho-Leal M, Repetto D, Volante M, et al. β1 integrin controls EGFR signaling and tumorigenic properties of lung cancer cells. Oncogene. 2011;30:4087–96. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pasternack H, Kuempers C, Deng M, Watermann I, Olchers T, Kuehnel M, et al. Identification of molecular signatures associated with early relapse after complete resection of lung adenocarcinomas. Sci Rep. 2021;11:9532. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-89030-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wu J, Zhou J, Xu Q, Foley R, Guo J, Zhang X, et al. Identification of key genes driving tumor associated macrophage migration and polarization based on immune fingerprints of lung adenocarcinoma. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:751800. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.751800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao Z, He B, Cai Q, Zhang P, Peng X, Zhang Y, et al. Combination of tumor mutation burden and immune infiltrates for the prognosis of lung adenocarcinoma. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;98:107807. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Luo J, Liu Z. Long non-coding RNA TTN-AS1 promotes the progression of lung adenocarcinoma by regulating PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;514:140–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The TCGA data analysed in this study can be accessed through the Genomic Data Commons Data Portal (http://cancergenome.nih.gov/). The wMKL is implemented in the R package wMKL, freely available on GitHub (https://github.com/biostatcao/wMKL).