Abstract

Apple is the most important fruit tree in West Azarbaijan province of Iran. In a survey of apple orchards, a disease with crown and collar canker and necrosis symptoms was observed in three young apple orchards in Urmia, affecting 15% and 1% of ‘Red Delicious’ and ‘Golden Delicious’ cultivars, respectively. A fungus with typical characteristics of the asexual morph of Cytospora was regularly isolated from the diseased tissues. Morphological characteristics and phylogenetic analyses inferred from the combined dataset of the ITS-rDNA, parts of LSU, tef1-α, rpb2, and act1 genes revealed that the isolates represent a new species of Cytospora, described herein as Cytospora balanejica sp. nov.. The pathogenicity of all isolates was confirmed on apple cv. ‘Red Delicious’ based on Koch’s postulates. Also, the reaction of 12 other apple cultivars was assessed against five selected isolates with the highest virulence. The results showed that except for cv. ‘Braeburn’, which did not produce any symptoms of the disease, the other 11 cultivars showed characteristic disease symptoms including sunken and discolored bark and wood. The mean length of the discolored area was different among the 11 so-called susceptible cultivars, hence cvs. ‘M4’ and ‘Golden Delicious’ showed the highest and the lowest lesion length, respectively. Moreover, the aggressiveness of the five tested isolates was different, and the isolates BA 2-4 and BA 3-1 had the highest and lowest aggressiveness, respectively. Based on our observations on the potential ability of the fungus to cause disease on young and actively growing apple trees, it will be a serious threat to apple cultivation and industry.

Subject terms: Plant sciences, Plant stress responses, Biotic

Introduction

The domesticated apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.) is one of the oldest, most popular, and widely grown temperate fruit crops in the world1,2. It is one of the most economically important fruit crops and ranks as the 3rd most produced fruit crop worldwide3. The fruits are predominantly used for the fresh market, even though other uses are cider production and processing4–6. Apple is an ancient fruit crop in Iran, growing in different locations from the northern to the western and central parts of the country7,8. A high level of genetic diversity is seen in cultivated apples in Iran, and the results of a phylogenetic study showed that Iran could be a paramount center of diversity for domesticated apples and an important center for domestication and passing on from Central Asia to the West via the Silk Routes8,9.

In Iran, West Azarbaijan province is the main apple-growing region with 63,661 ha and a total production of 1,118,285 metric tons in 2020, ranked first with 26.5% of the total production10. Apple trees have a long juvenile phase and often start bearing fruits after five years. For this reason, growers typically plant and grow a small number of well-assessed and historically successful apple varieties2. Two apple cultivars, ‘Red Delicious’ and ‘Golden Delicious’, are the main commercially grown apples in this region making up about 90% of apple cultivation.

Apple trees are affected by different fungal diseases; among them, stem and trunk canker as well as dieback diseases are of great importance, causing progressive losses over the years11–18. Depending on the incidence and severity of the infection, the disease impacts range from decreased yield with poor fruit quality and plant longevity to complete loss of fruits and trees, resulting in significant economic losses to growers. It has been estimated that abiotic and biotic stresses reduce the annual apple harvest by 12–25%19.

Cytospora species are important plant pathogens associated with branch dieback and canker disease on a wide range of plants with worldwide distribution20–23. They are usually considered as wound pathogens, invading host tissues through cracks, wounds, or other openings in the bark, leading to growth weakness and death of plants21,24–26. The fungal hyphae invade host tissues, decompose the cambium, and penetrate extensively into the phloem and xylem of trunks, twigs, and scaffold limbs, leading to perennial and latent infections providing a potential source of inoculum27–30.

Thus far, about 29 species of Cytospora have been reported from Malus spp. worldwide30–34, of which 19 species have been identified in Iran32,34–36. However, the taxonomic status of most of these species has not been confirmed through molecular approaches. Incorrect diagnosis and treatment of plant diseases generally result in the rapid spread of the diseases, and minor instances of these diseases can quickly become significant and costly problems under the pathogens’ rapid multiplication and conducive environmental conditions37. Due to the overlapping morphological characteristics, poor condition of single-gene phylogeny, and insufficiency of freshly collected specimens, multiphase approaches and multi-gene phylogeny have been suggested to elucidate accurate species boundaries among Cytospora isolates21,26,38.

During the past two decades and mainly due to climate change, apple orchards in West Azarbaijan province have been under severe threat from both biotic and abiotic agents18,34,39. Diplodia canker, die-back, decline, and root rots caused by different fungal pathogens, apple scab, and powdery mildew are the most prevalent fungal diseases of apple trees in the province15,18,39,40. In the course of our investigations on apple diseases in West Azarbaijan province, Iran, we observed disease symptoms including crown and collar canker and necrosis in three young apple orchards in Urmia, leading to relatively rapid tree decline and death. A fungus with Cytospora characteristics was frequently isolated from the diseased samples. The objective of this study was to (1) identify Cytospora species involved in the disease based on morphological characteristics and molecular multi-gene phylogeny, (2) assess the pathogenicity of the isolates on apple cv. ‘Red Delicious’ and (3) a preliminary evaluation of the reaction of 12 different apple cultivars to five selected isolates of the pathogen with higher aggressiveness.

Results

Disease symptoms, incidence, and fungal isolations

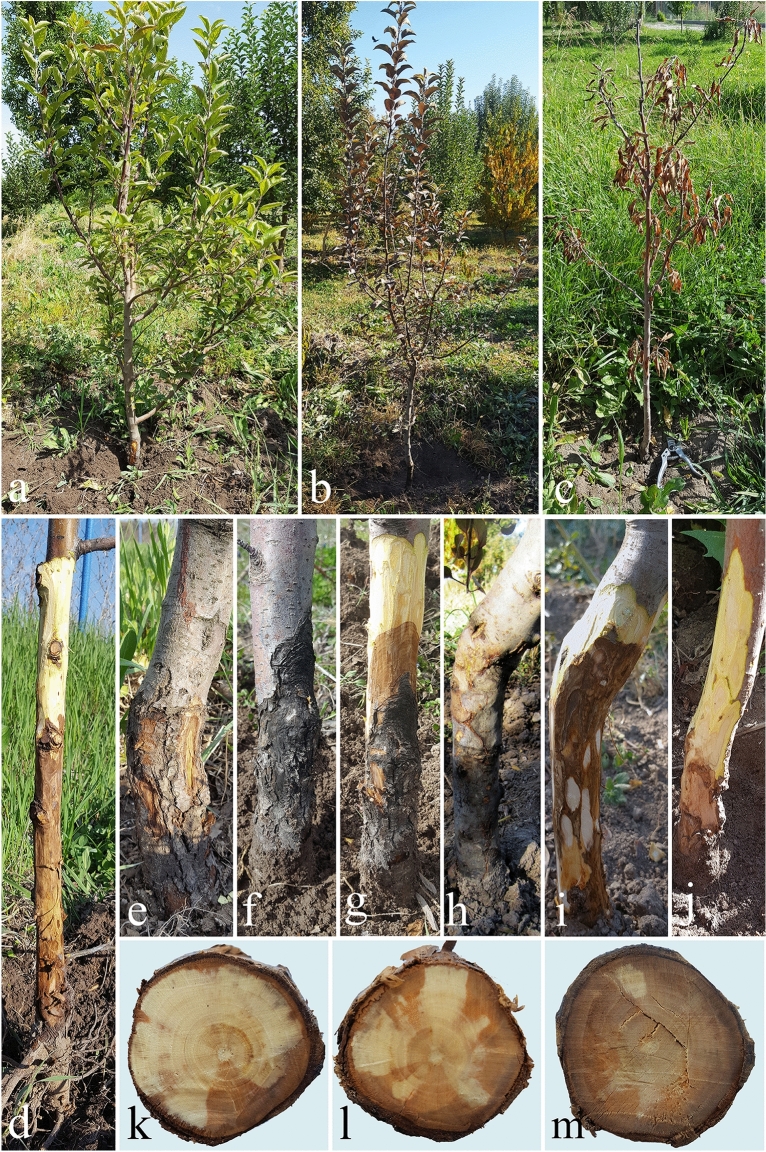

Characteristic external disease symptoms including general decline, cankers, and plant death were observed during the summer and early autumn in three young apple orchards, both on the cvs. ‘Golden Delicious’ and ‘Red Delicious’. The leaves in some individual branches were pale yellow in the beginning, then their margins became necrotic, and in late summer and early autumn, the color of the leaves turned purple and finally died (Fig. 1). Shoot elongation was arrested in affected plants. The bark of the diseased plants was discolored and sunken at the soil line, longitudinal cracks and cankers were formed on the bark surface and discoloration was extended progressively both upward (up to 50 cm from the graft union) and downward to the main roots and into the wood. A distinct margin separated the healthy bark tissue from the infected one and trees were killed when the infected area girdled the entire trunk base. In cross-sections, there was a light brown to brown discoloration and necrosis as V or U shape in the hardwood (Fig. 1). Based on these external symptoms in the surveyed orchards, the incidence of the disease on the cv. ʻRed Delicious’ (15%) was higher than the cv. ‘Golden Delicious’ (1%).

Figure 1.

Typical symptoms of crown and collar canker and necrosis on naturally infected young apple trees cvs. ‘Red Delicious’ and ‘Golden Delicious’. (a, b) cv. ‘Red Delicious’. (c) cv. ‘Golden Delicious’. (d–i) Disease symptoms on the crown, collar and trunk of the cvs. ‘Red Delicious’ and (j) ‘Golden Delicious’. (k–m) Cross sections showing disease progress in the infected trunks of the cv. ‘Red Delicious’.

In this study, 24 fungal isolates (19 from the cv. ʻRed Delicious’ and five from the cv. ʻGolden Delicious’) were obtained and purified (Table 1). Based on the comparison of morphological characteristics and banding patterns generated from the ISSR-PCR of the purified isolates, three isolates were selected for multi-gene phylogenetic analyses and accurate species identification.

Table 1.

Source, location and mean lesion lengths (mm) of 24 isolates of Cytospora balanejica on detached shoots of apple cv.

| Isolate | Source/location | Mean lesion length (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| BA 2-4 | Red Delicious, Balanej village (Orchard 1) | 172a |

| KU 1-1 | Golden Delicious, Kurane Village | 148b |

| BA 2-1 | Red Delicious, Balanej village (Orchard 1) | 102c |

| BA 3-1 | Red Delicious, Balanej village (Orchard 2) | 92d |

| BA 1-1 | Red Delicious, Balanej village (Orchard 2) | 82e |

| KU 1-2 | Red Delicious, Kurane village | 75f |

| BA 3-2 | Golden Delicious, Balanej village (Orchard 1) | 75f |

| KU 2-3 | Golden Delicious, Kurane Village | 75f |

| BA 2-3 | Red Delicious, Balanej village (Orchard 2) | 74g |

| BA 2-2 | Red Delicious, Balanej village (Orchard 1) | 73h |

| BA 3-3 | Red Delicious, Balanej village (Orchard 2) | 71i |

| KU 2-1 | Red Delicious, Kurane Village | 70j |

| KU 1-3 | Red Delicious, Kurane Village | 68k |

| BA 5-1 | Red Delicious, Balanej village (Orchard 1) | 66l |

| KU 2-2 | Red Delicious, Balanej village (Orchard 2) | 65m |

| BA 1-2 | Red Delicious, Balanej village (Orchard 1) | 65m |

| BA 5-2 | Golden Delicious, Balanej village (Orchard 1) | 62n |

| BA 5-3 | Red Delicious, Balanej Village (Orchard 1) | 58o |

| KU 3-2 | Red Delicious, Kurane Village | 57p |

| KU 3-1 | Red Delicious, Kurane Village | 55q |

| BA 1-3 | Red Delicious, Balanej village (Orchard 1) | 52r |

| BA 4-1 | Red Delicious, Balanej village (Orchard 2) | 50s |

| BA 4-3 | Red Delicious, Balanej village (Orchard 1) | 46t |

| BA 4-2 | Golden Delicious, Balanej village (Orchard 2) | 45u |

‘Red Delicious’ 21 days post-inoculation based on Duncan’s multiple range test. Different letters show significant differences at P ≤ 0.05.

Phylogenetic analyses

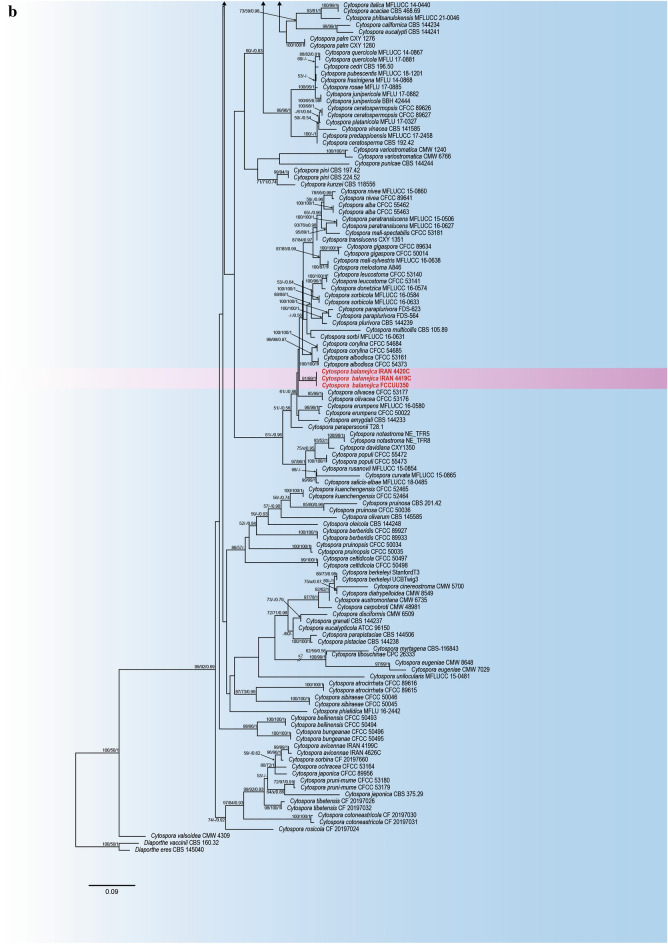

The phylogenetic analyses of the combined dataset (ITS, LSU, act1, rpb2, and tef 1-a) include 257 Cytospora ingroup strains representing 175 Cytospora species and Diaporthe eres CBS 145040 and Diaporthe vaccinii CBS 160.32 as outgroup strains with a total of 3049 characters (1641 constant sites, 1408 variable sites, 240 parsimony-uninformative sites and 1168 parsimony-informative sites) including gaps (642 for ITS, 574 for LSU, 354 for act1, 743 for rpb2, and 763 for tef1-α) (Table 2). The results of best-fit substitution model evaluation in MrModeltest v2.3 recommended GTR+I+G, GTR+I+G, GTR+I+G, GTR+I+G and HKY+I+G models for ITS, LSU, act1, rpb2 and tef 1-a, respectively (Table 2). The best-scoring RaxML tree with the final ML optimization likelihood value of − 47725.166937 (ln) is selected to denote and consider the phylogenetic relationships among the strains (Table 2, Fig. 2). The estimated base frequencies were as follows: A = 0.242358, C = 0.268654, G = 0.259113, T = 0.229874; substitution rates AC = 1.549133, AG = 3.919749, AT = 1.913775, CG = 1.087338, CT = 8.678832, GT = 1.000000; gamma distribution shape parameter α = 0.793946. A summary of phylogenetic information and substitution models for each dataset is provided in Table 2. Topologies of the individual gene trees were determined to be congruent and no conflicts were observed in species delimitation (data not shown). The phylogenetic trees generated from MP (TL = 9556; CI = 0.262; RI = 0.766; HI = 0.738) and BI analyses were topologically similar to the one generated via the ML analysis, and the latter is shown in Fig. 2. Cytospora balanejica represented a monophyletic clade with a high support value (ML/MP/BI = 91/99/1) (marked in pink in Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Phylogenetic information of individual and combined sequence datasets used in phylogenetic analyses.

| Parameter | ITS-rDNA | LSU | act1 | rpb2 | tef 1-a | Combined |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Taxa | 256 | 175 | 183 | 159 | 157 | 257 |

| Total characters | 642 | 547 | 354 | 743 | 763 | 3049 |

| Constant sites | 360 | 420 | 150 | 435 | 276 | 1641 |

| Variable sites | 282 | 127 | 204 | 308 | 487 | 1408 |

| Parsimony informative sites | 217 | 59 | 183 | 272 | 437 | 1168 |

| Parsimony uninformative sites | 65 | 68 | 21 | 36 | 50 | 240 |

| AIC Substitution Modela | GTR+I+G | GTR+I+G | GTR+I+G | GTR+I+G | HKY+I+G | GTR+I+G |

| Lset nst, Rates | 6, invgamma | 6, invgamma | 6, invgamma | 6, invgamma | 2, invgamma | 6, invgamma |

| -lnL | 7224.308797 | 2313.705431 | 6383.267168 | 10,954.098764 | 17,674.526253 | 47,725.166937 |

aAkaike Information Criterion Substitution models implemented in Bayesian Inference.

Figure 2.

Maximum Likelihood (ML) tree based on combined ITS, LSU, rpb2, act1 and tef 1-a sequences matrix in different Cytospora species. The Maximum Likelihood, Maximum Parsimony (MP) bootstrap support values and posterior probabilities of Bayesian inference (BIPP) > 50% are given at the nodes (ML/MP/BI). The tree was rooted to Diaporthe eres CBS 145040 and Diaporthe vaccinii CBS 160.32. The scale bar indicates the number of nucleotide substitutions.

Taxonomy

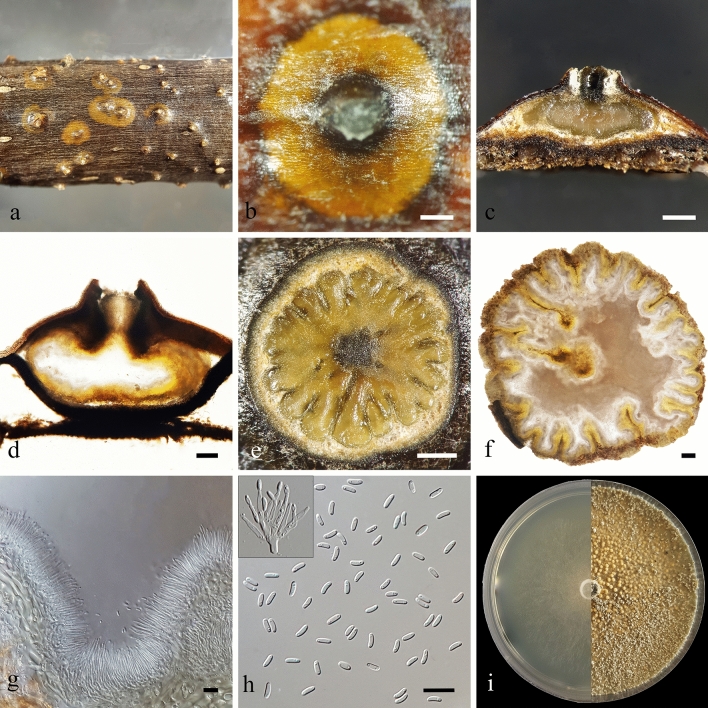

Cytospora balanejica R. Azizi, Y. Ghosta & A. Ahmadpour sp. nov. (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Morphology of Cytospora balanejica (IRAN 4419C). (a, b) Habit of conidiomata on twig. (c, d) Longitudinal section through conidiomata. (e, f) Transverse section of conidiomata. (g) Conidiophores and conidiogenous cells. (h) Conidia. (i) Colonies on PDA at 3 days (left) and 30 days (right). Scale bars: (b, c) and € = 250 µm; (f, d) = 100 µm and (g, h) = 10 µm.

MycoBank No.: MB843116.

Etymology: Named after the locality, Balanej village, where the holotype was collected.

Typification: Iran, West Azarbaijan Province, Urmia City, Balanej Village, 37°23′50.4″ N, 45°09′15.9″ E., from crown of Malus × domestica cv. ʻRed Delicious’, 15 Oct. 2017, R. Azizi (Holotype: IRAN 18133F; ex-type living culture: IRAN 4419C).

Description: Asexual morph: Conidiomata labyrinthine cytosporoid, immersed in the bark, erumpent when mature through the surface of the bark, discoid to conical, pale luteous to luteous, with multiple locules, (800–)850–1490(–1700) µm in diam. Conceptacle conspicuous, black, circular, surrounded the stromata. Ectostromatic disk greenish black to black, circular to ovoid, (473–)563–802(–845) µm in diam., with a single ostiole per disk in the center. Ostiole conspicuous, circular to ovoid, olivaceous grey, at the same level as the disk surface, (94–)101–215(–230) µm in diam. Locules numerous, arranged circularly with shared invaginated walls. Conidiophores borne along the locules, hyaline, smooth, thin-walled, unbranched, or occasionally branched at the base. Conidiogenous cells entroblastic, phialidic, subcylindrical to cylindrical, tapering towards apices, (6.2–)9–17(–19) × (1–)1.2–2 µm. Conidia hyaline, smooth, elongate allantoid, mostly biguttulate, aseptate, 3–5 × 1–1.8 µm. Sexual morph: not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies after 3 days at 25 °C on PDA average 57 mm and entirely covering the 90-mm diam. Petri dish after 7 days, margin entire, white to buff, with scattered aerial hyphae at the center, the hyphae becoming very dense, pale luteous at center and honey at margins, forming abundant solitary or rarely aggregated pycnidia surrounded by off-white hyphae with age. Hyphae hyaline to light brown, septate, smooth-walled, and branched.

Habitat and distribution: Known only on Malus × domestica in Urmia, Iran.

Additional specimens examined: Iran, West Azarbaijan Province, Urmia City, Balanej Village, 37°24′26.1″ N, 45°10′24.8″ E., from the trunk of Malus × domestica cv. ‘Red Delicious’, 15 Oct. 2017, R. Azizi, (IRAN 4420C); West Azarbaijan Province, Urmia City, Kurane Village, 37°24′44.4″ N 45°8′45.3′′ E., from the trunk of Malus × domestica cv. ‘Golden Delicious’, 12 Sept. 2018, R. Azizi, (FCCUU 350).

Notes: Cytospora balanejica was isolated from young, declining apple trees showing symptoms of crown and collar canker and necrosis. The phylogenetic inferences based on the combined multi-gene phylogeny resolved this species as a monophyletic lineage distinct from all other strains included in this study, but closely related to a clade containing C. albodisca M. Pan & X.L. Fan and C. corylina H. Gao & X.L. Fan (Fig. 2). However, C. balanejica differs from C. albodisca based on the absence of ascomata and smaller conidia (3–5 × 1–1.8 µm vs. 5–7 × 1–2 µm in C. albodisca)26. Also, it differs from C. corylina based on the formation of distinct conceptacle, larger conidiomata (800–1700 µm vs. 850–1280 µm) and shorter conidia (3–5 µm vs. 3.5–7.5 µm in C. corylina)41. Pairwise sequence comparisons of the genomic regions in C. balanejica strain IRAN 4419C showed considerable nucleotide differences from C. albodisca strain CFCC 53161 (including 2 out of 466 in ITS, 30 out of 726 in rpb2, 20 out of 160 in act1 and 73 out of 516 in tef1-α) and C. corylina strain CFCC 54684 (including 2 out of 466 in ITS, 30 out of 726 in rpb2, 17 out of 161 in act1 and 75 out of 513 in tef1-α). Therefore, we describe C. balanejica here as a new species.

Pathogenicity trials

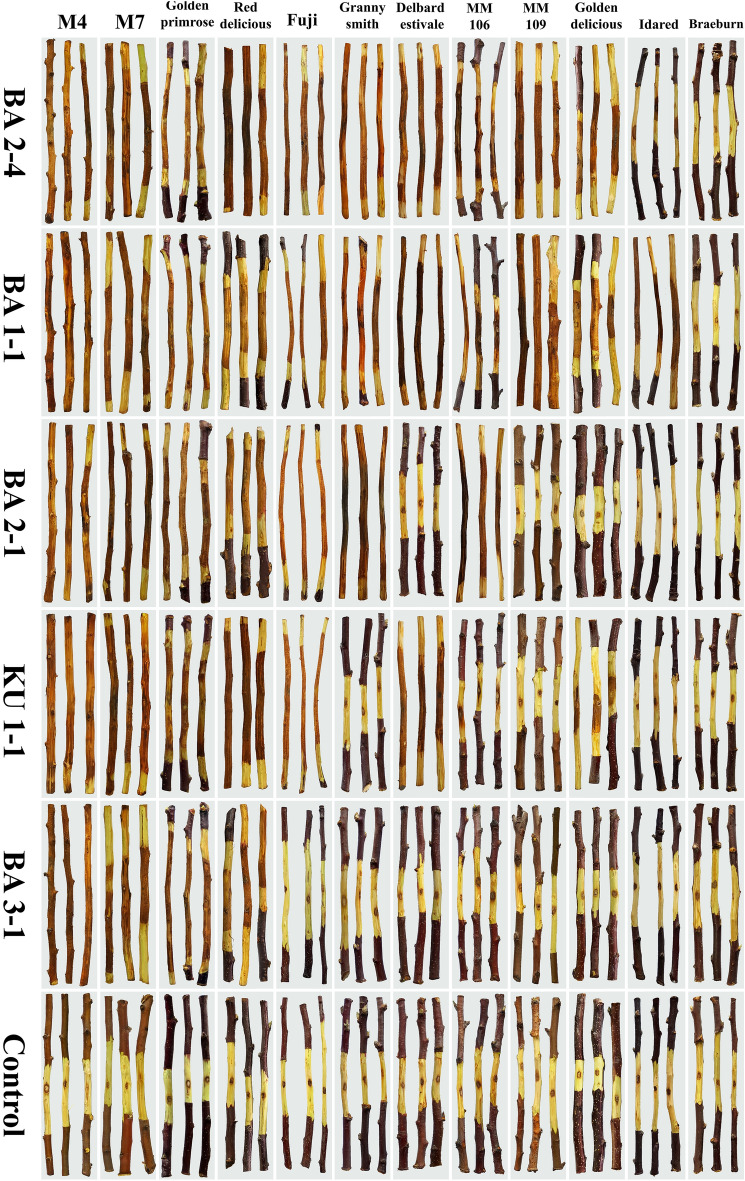

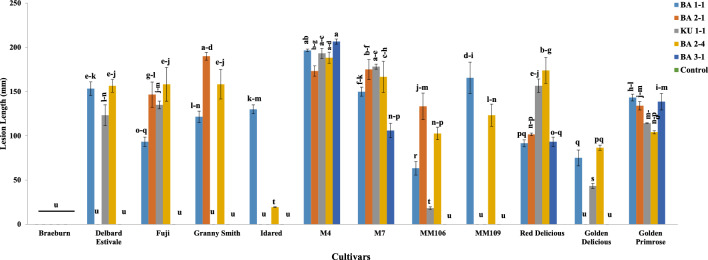

Results of pathogenicity tests of the isolates (24 isolates) on shoots of the cv. ‘Red Delicious’ showed sunken discolored lesions around the inoculated sites 14 days post-inoculation. Bark and wood discoloration was extended progressively upward and downward the inoculation site and after 20 days, fungal pycnidia were formed on the discolored bark. Despite this, the mean length of necrotic lesions varied among the isolates and ranged from 45 to 172 mm (Table 1). Also, the results of pathogenicity tests of the most virulent isolate (BA 2-4) under field conditions clearly showed bark and wood discoloration and necrosis 45 days post-inoculation (Fig. 4). Re-isolation of the inoculated fungus and re-identification based on morphological characteristics fulfilled Koch’s postulates. All negative controls were asymptomatic and no colonies were obtained from samples taken from the controls. The reaction of 12 tested cultivars against five selected isolates with the highest virulence showed that the interaction between the factors isolates × cultivars was varied and significantly different at P ≤ 0.05 (Figs. 5 and 6). Except for the cv. ‘Braeburn’ which did not produce any symptoms of infection similar to control treatment against all tested fungal isolates, the other cultivars showed symptoms of infection at least against two fungal isolates (Fig. 5). The mean length of necrotic lesion ranged from 19.3 mm (the cv. ‘Idared’) to 188.3 mm (the cv. ‘M4’) for isolate BA 2-4 and from 63.3 mm (the cv. ‘MM106’) to 196.6 mm (the cv. ‘M4’) for isolate BA 1-1, both isolates were obtained from the cv. ‘Red Delicious’ (Fig. 6). The mean length of necrotic lesions ranged from 18.3 mm (the cv. ‘MM106’) to 193.3 mm (the cv. ‘M4’) for isolate KU 1-1 which was isolated from the cv. ‘Golden Delicious’, although the cvs. ‘Granny Smith’, ‘MM109’, and ‘Idared’ did not show any symptoms of infection against this isolate (Fig. 6). Also, the cvs. ‘Delbard Estivale’, ‘MM109’, ‘Idared’, and ‘Golden Delicious’ did not develop any symptoms of infection against BA 2-1 isolate and the mean length of necrotic lesion ranged from 101.6 mm (the cv. ‘Red Delicious’) to 190 mm (the cv. ‘Granny Smith’). At last, only four cultivars including ‘M4’, ‘M7’, ‘Golden Primrose’, and ‘Red Delicious’ developed symptoms of infection against BA 3-1 isolate and the mean length of necrotic lesion ranged from 93.3 mm (the cv. ‘Red Delicious’) to 206.6 mm (the cv. ‘M4’) (Fig. 6). Moreover, the aggressiveness of five tested isolates was varied and the isolates BA 2-4 and BA 3-1 had the highest and lowest aggressiveness against 12 tested cultivars, respectively.

Figure 4.

Pathogenicity tests of the most virulent isolate (BA 2-4) on apple cv. ‘Red Delicious’ under field conditions. (A–D) Inoculation process. (E, F) Bark and wood discoloration and necrosis 45 days post inoculation.

Figure 5.

Pathogenicity tests of five selected isolates (BA 1-1, BA 1-2, BA 2-4, BA 3-1, and KU 1-1) of Cytospra balanejica against 12 apple cultivars.

Figure 6.

Mean lesion lengths (mm) of 12 apple cultivars inoculated with five selected isolates of Cytospora balanejica based on Duncan’s multiple range test. Different letters show statistically significant differences at P ≤ 0.05.

Discussion

In this study, we found a new species of Cytospora, C. balanejica, associated with crown and collar canker and decline symptoms in young apple trees. The incidence of the disease was greater on the cv. ‘Red Delicious’ than the cv. ‘Golden Delicious’, indicating higher susceptibility of the first cultivar to this new Cytospora species. Our pathogenicity tests confirmed this, as all studied isolates were pathogenic on the shoots of the cv. ‘Red Delicious’ and had greater virulence (longer necrotic lesions) than the cv. ‘Golden Delicious’ (Fig. 6). Although the disease incidence was significantly lower in the cv. ‘Golden Delicious’ than the cv. ‘Red Delicious’, it is important to note that the infected plants can provide an inoculum reservoir for the pathogen.

The results of our study showed that the cv. ‘Braeburn’ did not develop any symptoms of infection against all the tested fungal isolates, suggesting that it might have some levels of resistance to the disease. The other 11 examined cultivars showed lesions with various degrees of severity and could be considered susceptible. The resistance of 53 accessions of diverse Malus species and their interspecific hybrids was tested against Valsa ceratosperma (syn.: Cytospora ceratosperma) using excised shoot assay and by measuring the length of necrotic lesion42. Fourteen accessions were evaluated as resistant and the highest level of resistance was identified in Malus sieboldii Rehder, which was effective against different isolates of the tested fungus. Similar results were also found in pathogenicity studies using different fungal species and host plants43–48. The virulence of the tested fungal isolates as measured by lesion length was varied and this could be attributed to the genetic diversity among the isolates. Variability in the lesion length has been reported in pathogenicity evaluations of the isolates of Cytospora spp. and other fungal pathogens31,46,49–53.

Cytospora species generally cause canker, dieback and decline diseases with different symptoms on a wide range of woody perennials including fruit and nut trees, forest and urban trees, and rarely on herbaceous plants with strong ecological adaptability21,26,41,54,55. In our study, disease symptoms differed from the previously reported symptoms of apple canker diseases caused by Cytospora species, as the disease starts from the crown and collar region of apple trees (Fig. 1). Other apple diseases such as Neonectria canker, Phytophthora crown, collar and root rots, Rosellinia root rot and fire blight have been reported in the literature to cause similar symptoms on affected young apple trees13,56. The similarity in symptoms caused by C. balanejica and other diseases, especially in the early stages of disease development, makes it difficult to accurately identify the causal agents without further laboratory examination.

Apple is one of the main hosts that suffer severe damage from the Cytospora canker disease31,57,58. In a most recent study, eight species of Cytospora were identified from apple trees in Iran34, emphasizing the necessity of extensive pathogen surveys in apple production regions. Understanding the exact diversity of pathogenic fungi such as Cytospora spp. is crucial for devising regional management strategies for each species, developing rapid diagnostic tools, screening for resistance, and accomplishing regulatory control measurements59. Earlier species identification in Cytospora has relied on morphological characteristics and host associations; however, these characteristics are not stable and informative, confusing species identification and delimitation41,55,60.

The results of our phylogenetic analyses using ITS-rDNA sequences placed C. balanejica together with C. albodisca, C. corylina, and C. olivacea in an unresolved clade, confirmed the poor utility of this genomic region in the differentiation of Cytospora species21,38,61,62 (Supplementary Fig. S1). Recent studies using a polyphasic approach, morphology, and multi-gene phylogeny, have revealed hidden fungal diversity, and led to the description of several new cryptic Cytospora species21,23,26,38,41. Based on our multi-gene phylogenetic analyses, C. balanejica formed a well-defined monophyletic lineage distinct from all other strains with close affinity to C. albodisca and C. corylina, two recently described Cytospora species (Fig. 2). Cytospora albodisca and C. corylina were isolated from the branches of Platycladus orientalis (L.) Franco and Corylus heterophylla Fisch. ex. Trautv. in China showing canker and dieback symptoms, respectively26,41.

This study found that apple trees are hosts of a new pathogenic species of Cytospora, which should be considered a potentially important causal agent of apple crown and collar canker disease in the studied area. Because Cytospora species are generally considered wound pathogens, infecting plants through cracks and wounds caused by freezing injuries, leaf scars, sunburn, oil injuries, shade-weakened twigs, and pruning wounds21,53,63, more precautions should be taken during grafting. Even though this study extends our knowledge about the role of a new Cytospora species in crown and collar canker disease on young apple trees, more studies are needed to reveal its biology and ecology, assess the susceptibility/resistance of apple cultivars under field conditions, and its host range and epidemiology to the development of effective management strategies.

Material and methods

Collection of samples and fungi isolation

Young apple trees (2–6 years old) showing symptoms of decreased growth, decline, and death from three orchards in Urmia, West Azarbaijan province, Iran, were evaluated. Samples were collected from the crown, collar, and trunk base showing bark and wood discoloration and canker (Fig. 1), placed separately in clean paper bags, and transferred to the laboratory for further investigation. Samples were washed gently under running tap water, then cut into smaller pieces (1 × 1 cm2) from the interfaces of the healthy and diseased tissues, and surface disinfested in 3% sodium hypochlorite solution for 2 min, rinsed again three times with sterile distilled water and blotted dry on autoclave sterilized filter paper. The pieces were plated onto potato-dextrose-agar medium supplemented with streptomycin sulfate and penicillin G (150 ppm each) to inhibit bacterial growth (PDA; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) in 90 mm diam. glass Petri dishes. Petri dishes were incubated at 25 ± 1 °C in darkness, examined at 24 h intervals and hyphae growing out from the plant tissues were transferred to fresh PDA. Pure cultures were obtained using the hyphal tip method. The purified isolates were maintained on PDA slants containing a piece of filter paper and stored at 4 °C. The isolates were deposited in the Fungal Culture Collection of the Iranian Research Institute of Plant Protection (“IRAN”) and the Fungal Culture Collection of Urmia University (FCCUU).

Plant materials

It is noted that plant materials used in this study were legitimate samples from apple orchards and all methods comprising plant studies were performed following the relevant guidelines, regulations, and legislation. Required permission to collect samples of apple trees from various orchards in Urmia, West Azarbaijan province, was obtained.

DNA extraction, PCR amplification, sequencing, and phylogenetic analysis

Total genomic DNA was extracted from the mycelial mass of fungal isolates cultured in potato dextrose broth (PDB, Mirmedia Microbiology, Iran) for 7–10 days using the Exgene™ Cell SV mini kit (GeneAll Biotechnology Co, South Korea) following the manufacturer’s instruction. For the preliminary screening of all recovered isolates, polymorphic banding patterns of the isolates were generated by an ISSR-PCR method with ISSR5 ((GA)5YC) primer and were compared. Each polymerase chain reaction (PCR) mixture contained 0.4 μM of the primer, 4 μL of a ready master mix (Taq DNA polymerase 2× Master Mix Red, 2 mM MgCl2, Ampliqon Company, Denmark), and about 10 ng of template DNA in a final volume of 10 μL. The thermal cycling condition consisted of an initial denaturation step of 5 min at 95 °C followed by 35 cycles of 45 s at 95 °C, 60 s at 41 °C and 90 s at 72 °C and a final extension step of 10 min at 72 °C. Amplicons were visualized on a 1% agarose gel. Isolates with the same banding pattern were considered as the same taxon. To reveal the phylogenetic relationship among the isolates, three isolates were selected based on ISSR banding pattern and morphological characteristics for multi-gene sequencing (Table 3). The internal transcribed spacer region of nuclear ribosomal DNA (ITS1-5.8S-ITS2), parts of the nuclear ribosomal large subunit (LSU), translation elongation factor 1-α (tef1-α), RNA polymerase II (rpb2) and actin (act1) genes were amplified using the primer pairs ITS5/ITS464, LR0R/LR765, EF1-728F/EF-266,67, RPB2-5F2/fRPB2-7cR68,69 and ACT512F/ACT783R67, respectively. All primers were purchased from Pishgam Company, Tehran, Iran. The PCR mixtures for all reactions consisted of about 10 ng/µL of genomic DNA, 0.4 µM of each primer, and 12.5 µL of 2× ready-to-use reaction mix (Taq DNA polymerase 2× Master Mix Red, 2 mM MgCl2, Ampliqon, Denmark) in a total volume of 25 µL. Thermal conditions for PCR amplification of ITS, LSU, act1, and tef1-α consisted of an initial denaturation step of 5 min at 95 °C, followed by 35 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 57 °C and 60 s at 72 °C, and a final extension step of 5 min at 72 °C. The part of the rpb2 gene was amplified using touch-down PCR consisting of an initial denaturation step of 5 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 45 s at 95 °C, 45 s at 60–55 °C (annealing temperature decreased 0.5 °C in the first 10 cycles), 45 s at 72 °C and a final extension step of 10 min at 72 °C. PCR products were visualized on a 1.5% Agarose gel (100 V for 30 min) stained with CyberSafe (Safe DNA Stain, 6X Pishgam, Iran), following the manufacturer’s instruction to confirm the amplicon presence and size. Amplification products were purified and sequenced by Macrogen Inc. (Seoul, South Korea).

Table 3.

Fungal isolates used in the molecular analyses in this study and GenBank accession numbers.

| Species | Straina | Host | Origin | GenBank accession numbers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | LSU | act1 | rpb2 | tef1-α | ||||

| Cytospora abyssinica | CMW 10181T | Eucalyptus globulus | Ethiopia | AY347353 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. abyssinica | CMW 10178 | Eucalyptus globulus | Ethiopia | AY347354 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. acaciae | CBS 468.69 | Ceratonia siliqua | Spain | DQ243804 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. ailanthicola | CFCC 89970T | Ailanthus altissima | Ningxia, China | MH933618 | MH933653 | MH933526 | MH933592 | MH933494 |

| C. alba | CFCC 55462T | Salix matsudana | Gansu, China | MZ702593 | NA | OK303457 | OK303516 | OK303577 |

| C. alba | CFCC 55463T | Salix matsudana | Gansu, China | MZ702594 | NA | OK303458 | OK303517 | OK303578 |

| C. albodisca | CFCC 53161T | Platycladus orientalis | Beijing, China | MW418406 | MW418418 | MW422899 | MW422909 | MW422921 |

| C. albodisca | CFCC 54373 | Platycladus orientalis | Beijing, China | MW418407 | MW418419 | MW422900 | MW422910 | MW422922 |

| C. ampulliformis | MFLUCC 16-0583T | Sorbus intermedia | Russia | KY417726 | KY417760 | KY417692 | KY417794 | NA |

| C. ampulliformis | MFLUCC 16-0629 | Acer platanoides | Russia | KY417727 | KY417761 | KY417693 | KY417795 | NA |

| C. amygdali | CBS 144233T | Prunus dulcis | California, USA | MG971853 | NA | MG972002 | NA | MG971659 |

| C. atrocirrhata | CFCC 89615 | Juglans regia | Qinghai, China | KR045618 | KR045700 | KF498673 | KU710946 | KP310858 |

| C. atrocirrhata | CFCC 89616 | Juglans regia | Qinghai, China | KR045619 | KR045701 | KF498674 | KU710947 | KP310859 |

| C. austromontana | CMW 6735T | Eucalyptus pauciflora | Australia | AY347361 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. avicennae | IRAN 4199CT | Malus domestica | Nahavand, Iran | MW295650 | NA | MZ014511 | MW824358 | MW394145 |

| C. avicennae | IRAN 4626C | Malus domestica | Arak, Iran | OM368649 | NA | NA | NA | OM372511 |

| C. azerbaijanica | IRAN 4201CT | Malus domestica | Urmia, Iran | MW295526 | NA | MZ014513 | MW824360 | MW394147 |

| C. azerbaijanica | IRAN 4627C | Malus domestica | Miandoab, Iran | OM368650 | NA | NA | NA | OM372512 |

| C. balanejica | IRAN 4419CT | Malus domestica | Urmia, Iran | MZ948960 | MZ948957 | MZ997842 | MZ997845 | MZ997848 |

| C. balanejica | IRAN 4420C | Malus domestica | Urmia, Iran | MZ948961 | MZ948958 | MZ997843 | MZ997846 | MZ997849 |

| C. balanejica | FCCUU 350 | Malus domestica | Urmia, Iran | MZ948962 | MZ948959 | MZ997844 | MZ997847 | MZ997850 |

| C. beilinensis | CFCC 50493T | Pinus armandii | Beijing, China | MH933619 | MH933654 | MH933527 | NA | MH933495 |

| C. beilinensis | CFCC 50494 | Pinus armandii | Beijing, China | MH933620 | MH933655 | MH933528 | NA | MH933496 |

| C. berberidis | CFCC 89927T | Berberis dasystachya | Qinghai, China | KR045620 | KR045702 | KU710990 | KU710948 | KU710913 |

| C. berberidis | CFCC 89933 | Berberis dasystachya | Qinghai, China | KR045621 | KR045703 | KU710991 | KU710949 | KU710914 |

| C. berkeleyi | StanfordT3T | Eucalyptus globulus | USA | AY347350 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. berkeleyi | UCBTwig3 | Eucalyptus globulus | USA | AY347349 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. brevispora | CBS 116811T | Eucalyptus grandis tereticornis | Congo | AF192315 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. bungeana | CFCC 50495T | Pinus bungeana | Shanxi, China | MH933621 | MH933656 | MH933529 | MH933593 | MH933497 |

| C. bungeana | CFCC 50496 | Pinus bungeana | Shanxi, China | MH933622 | MH933657 | MH933530 | MH933594 | MH933498 |

| C. calamicola | MFLUCC 15-0397T | Calamus sp. | Phang-Nga, Thailand | ON650702 | ON650679 | NA | NA | NA |

| C. californica | CBS 144234T | Juglans regia | California, USA | MG971935 | NA | MG972083 | NA | MG971645 |

| C. carbonacea | CFCC 89947 | Ulmus pumila | Qinghai, China | KR045622 | KP310812 | KP310842 | KU710950 | KP310855 |

| C. carpobroti | CMW 48981T | Carpobrotus edulis | South Africa | MH382812 | MH411216 | NA | NA | MH411212 |

| C. cedri | CBS 196.50 | NA | Italy | AF192311 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. celtidicola | CFCC 50497T | Celtis sinensis | Anhui, China | MH933623 | MH933658 | MH933531 | MH933595 | MH933499 |

| C. celtidicola | CFCC 50498 | Celtis sinensis | Anhui, China | MH933624 | MH933659 | MH933532 | MH933596 | MH933500 |

| C. centrivillosa | MFLUCC 16-1206T | Sorbus domestica | Italy | MF190122 | MF190068 | NA | MF377600 | NA |

| C. centrivillosa | MFLUCC 17-1660 | Sorbus domestica | Italy | MF190123 | MF190069 | NA | MF377601 | NA |

| C. ceratosperma | CBS 192.42 | Taxus baccata | Switzerland | AY347333 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. ceratospermopsis | CFCC 89626T | Juglans regia | Shaanxi, China | KR045647 | KR045726 | KU711011 | KU710978 | KU710934 |

| C. ceratospermopsis | CFCC 89627 | Juglans regia | Shaanxi, China | KR045648 | KR045727 | KU711012 | KU710979 | KU710935 |

| C. chiangmaiensis | MFLUCC 21-0049T | Shorea sp. | Chiang Mai,Thailand | MZ356514 | MZ356518 | MZ451157 | MZ451165 | MZ451161 |

| C. chrysosperma | CFCC 89981 |

Populus alba subsp. pyramidalis |

Gansu, China | MH933625 | MH933660 | MH933533 | MH933597 | MH933501 |

| C. chrysosperma | CFCC 89982 | Ulmus pumila | Tibet, China | KP281261 | KP310805 | KP310835 | NA | KP310848 |

| C. cinereostroma | CMW 5700T | Eucalyptus globulus | Chile | AY347377 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. cinnamomea | CFCC 53178T | Prunus armeniaca | Xinjiang, China | MK673054 | MK673084 | MK673024 | NA | NA |

| C. coryli | CFCC 53162T | Corylus mandshurica | Beijing, China | MN854450 | MN854661 | NA | MN850751 | MN850758 |

| C. corylina | CFCC 54684T | Corylus heterophylla | Beijing, China | MW839861 | NA | MW815937 | MW815951 | MW815886 |

| C. corylina | CFCC 54685 | Corylus heterophylla | Beijing, China | MW839862 | NA | MW815938 | MW815952 | MW815887 |

| C. cotini | MFLUCC 14-1050T | Cotinus coggygria | Russia | KX430142 | KX430143 | NA | KX430144 | NA |

| C. cotoneastricola | CF 20197030 | Cotoneaster sp. | Tibet, China | MK673074 | MK673104 | MK673044 | MK673014 | MK672960 |

| C. cotoneastricola | CF 20197031T | Cotoneaster sp. | Tibet, China | MK673075 | MK673105 | MK673045 | MK673015 | MK672961 |

| C. curvata | MFLUCC 15-0865T | Salix alba | Russia | KY417728 | KY417762 | KY417694 | NA | NA |

| C. curvispora | CFCC 54000T | Corylus heterophylla | Beijing, China | MW839851 | NA | MW815931 | MW815945 | MW815880 |

| C. davidiana | CXY 1350T | Populus davidiana | Inner Mongolia, China | KM034870 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. diatrypelloidea | CMW 8549T | Eucalyptus globulus | Australia | AY347368 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. diopuiensis | MFLUCC 18-1419T | Undefined wood | Chiang Mai, Thailand | MK912137 | MK571765 | MN685819 | NA | NA |

| C. disciformis | CMW 6509T | Eucalyptus grandis | Uruguay | AY347374 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. discostoma | CFCC 53137T | Platycladus orientalis | Beijing, China | MW418404 | MW418416 | MW422897 | MW422907 | MW422919 |

| C. discostoma | CFCC 54368 | Platycladus orientalis | Beijing, China | MW418405 | MW418417 | MW422898 | MW422908 | MW422920 |

| C. donetzica | MFLUCC 16-0574T | Crataegus monogyna | Russia | KY417731 | KY417765 | KY417697 | KY417799 | NA |

| C. donglingensis | CFCC 53159T | Platycladus orientalis | Beijing, China | MW418412 | MW418424 | MW422903 | MW422915 | MW422927 |

| C. donglingensis | CFCC 54371 | Platycladus orientalis | Beijing, China | MW418413 | MW418425 | MW422904 | MW422916 | MW422928 |

| C. elaeagni | CFCC 89632 | Elaeagnus angustifolia | Ningxia, China | KR045626 | KR045706 | KU710995 | KU710955 | KU710918 |

| C. elaeagni | CFCC 89633 | Elaeagnus angustifolia | Ningxia, China | KF765677 | KF765693 | KU710996 | KU710956 | KU710919 |

| C. elaeagnicola | CFCC 52882T | Elaeagnus angustifolia | China | MK732341 | MK732338 | MK732344 | MK732347 | NA |

| C. elaeagnicola | CFCC 52883 | Elaeagnus angustifolia | China | MK732342 | MK732339 | MK732345 | MK732348 | NA |

| C. eriobotryae | IMI 136523T | Eriobotrya japonica | India | AY347327 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. ershadii | IRAN 4198CT | Malus domestica | Arak, Iran | MW295523 | NA | MZ014510 | MW824357 | MW394144 |

| C. ershadii | IRAN 4197C | Malus domestica | Nahavand, Iran | MW295510 | NA | NA | NA | MW394143 |

| C. erumpens | MFLUCC 16-0580T | Salix × fragilis | Russia | KY417733 | KY417767 | KY417699 | KY417801 | NA |

| C. erumpens | CFCC 50022 | Prunus padus | Shanxi, China | MH933627 | MH933661 | MH933534 | NA | MH933502 |

| C. eucalypti | CBS 144241 | Eucalyptus globulus | California, USA | MG971907 | NA | MG972056 | NA | MG971617 |

| C. eucalypticola | ATCC 96150T | Eucalyptus nitens | Australia | AY347358 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. eucalyptina | CMW 5882 | Eucalyptus grandis | Columbia | AY347375 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. eugeniae | CMW 7029 | Tibouchina sp. | Australia | AY347364 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. eugeniae | CMW 8648 | Eugenia sp. | Indonesia | AY347344 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. euonymicola | CFCC 50499T | Euonymus kiautschovicus | Shaanxi, China | MH933628 | MH933662 | MH933535 | MH933598 | MH933503 |

| C. euonymicola | CFCC 50500 | Euonymus kiautschovicus | Shaanxi, China | MH933629 | MH933663 | MH933536 | MH933599 | MH933504 |

| C. euonymina | CFCC 89993T | Euonymus kiautschovicus | Shanxi, China | MH933630 | MH933664 | MH933537 | MH933600 | MH933505 |

| C. fraxiicola | MFLU 17-2392 | dead branches | Russia | NA | MN764356 | MN995562 | NA | NA |

| C. fraxinigena | MFLUCC 14-0868T | Fraxinus ornus | Italy | MF190133 | MF190078 | NA | NA | NA |

| C. friesii | CBS 194.42 | Abies alba | Switzerland | AY347328 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. fugax | CBS 203.42 | Salix sp. | Switzerland | AY347323 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. galegicola | MFLUCC 18-1199T | Galega officinalis | Forlì-Cesena, Italy | MK912128 | MK571756 | MN685810 | MN685820 | NA |

| C. gelida | MFLUCC 16-0634T | Cotinus coggygria | Russia | KY563245 | KY563247 | KY563241 | KY563243 | NA |

| C. germanica | CXY 1322 | Elaeagnus oxycarpa | China | JQ086563 | JX524617 | NA | NA | NA |

| C. gigalocus | CFCC 89620T | Juglans regia | Qinghai, China | KR045628 | KR045708 | KU710997 | KU710957 | KU710920 |

| C. gigalocus | CFCC 89621 | Juglans regia | Qinghai, China | KR045629 | KR045709 | KU710998 | KU710958 | KU710921 |

| C. gigaspora | CFCC 50014 | Juniperus procumbens | Shanxi, China | KR045630 | KR045710 | KU710999 | KU710959 | KU710922 |

| C. gigaspora | CFCC 89634T | Salix psammophila | Shaanxi, China | KF765671 | KF765687 | KU711000 | KU710960 | KU710923 |

| C. globosa | MFLU 16-2054T | Abies alba | Italy | MT177935 | MT177962 | NA | MT432212 | MT454016 |

| C. granati | CBS 144237T | Punica granatum | California, USA | MG971799 | NA | MG971949 | NA | MG971514 |

| C. haidianensis | CFCC 54057T | Euonymus alatus | China | MT360042 | NA | MT363979 | MT363988 | MT363998 |

| C. haidianensis | CFCC 54184 | Euonymus alatus | Beijing, China | MT360043 | NA | MT363980 | MT363989 | MT363999 |

| C. heveae | MFLUCC 17-0358T | Hevea brasiliensis | Thailand | OL780505 | OL782085 | OL944407 | NA | OL944428 |

| C. hippophaës | CFCC 89639 | Hippophaë rhamnoides | Gansu, China | KR045632 | KR045712 | KU711001 | KU710961 | KU710924 |

| C. hippophaës | CFCC 89640 | Hippophaë rhamnoides | Gansu, China | KF765682 | KF765698 | KF765730 | KU710962 | KP310865 |

| C. hippophaicola | CBS 147584T | Hippophae rhamnoides | Czech Republic | MZ702814 | MZ702873 | MZ712150 | MZ712160 | MZ712155 |

| C. hippophaicola | MEND-F-0554 | Vaccinium corymbosum | Czech Republic | MZ702815 | MZ702872 | MZ712151 | MZ712161 | MZ712156 |

| C. iranica | IRAN 4200CT | Malus domestica | Arak, Iran | MW295652 | NA | MZ014512 | MW824359 | MW394146 |

| C. iranica | IRAN 4628C | Malus domestica | Nahavand, Iran | OM368651 | NA | NA | NA | OM372513 |

| C. italica | MFLUCC 14-0440 | Tamarix gallica | Italy | KU900329 | KU900301 | NA | NA | NA |

| C. japonica | CBS 375.29 | Prunus persica | Japan | AF191185 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. japonica | CFCC 89956 | Prunus cerasifera | Ningxia, China | KR045624 | KR045704 | KU710993 | KU710953 | KU710916 |

| C. joaquinensis | CBS 144235T | Populus deltoides | California, USA | MG971895 | NA | MG972044 | NA | MG971605 |

| C. junipericola | BBH 42444 | Juniperus communis | Italy | MF190126 | MF190071 | NA | NA | MF377579 |

| C. junipericola | MFLU 17-0882T | Juniperus communis | Italy | MF190125 | MF190072 | NA | NA | MF377580 |

| C. juniperina | CFCC 50501T | Juniperus przewalskii | Sichuan, China | MH933632 | MH933666 | MH933539 | MH933602 | MH933507 |

| C. juniperina | CFCC 50502 | Juniperus przewalskii | Sichuan, China | MH933633 | MH933667 | MH933540 | MH933603 | MH933508 |

| C. kantschavelii | CXY 1386 | Populus maximowiczii | Chongqing, China | KM034867 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. koelreutericola | CFCC 56961T | Koelreuteria paniculata | Beijing, China | ON376918 | NA | ON390905 | ON390908 | ON390914 |

| C. koelreutericola | CFCC 56970 | Koelreuteria paniculata | Beijing, China | ON376917 | NA | ON390904 | ON390907 | ON390913 |

| C. kuanchengensis | CFCC 52464T | Castanea mollissima | China | MK432616 | MK429886 | MK442940 | MK578076 | NA |

| C. kuanchengensis | CFCC 52465 | Castanea mollissima | China | MK432617 | MK429887 | MK442941 | MK578077 | NA |

| C. kunzei | CBS 118556 | Pinus radiata | South Africa | DQ243791 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. leucosperma | CFCC 89622 | Pyrus bretschneideri | Gansu, China | KR045616 | KR045698 | KU710988 | KU710944 | KU710911 |

| C. leucosperma | CFCC 89894 | Pyrus bretschneideri | Qinghai, China | KR045617 | KR045699 | KU710989 | KU710945 | KU710912 |

| C. leucostoma | CFCC 53140 | Prunus sibirica | Beijing, China | MN854445 | MN854656 | MN850760 | MN850746 | MN850753 |

| C. leucostoma | CFCC 53141 | Prunus sibirica | Beijing, China | MN854446 | MN854657 | MN850761 | MN850747 | MN850754 |

| C. longiostiolata | MFLUCC 16-0628T | Salix × fragilis | Russia | KY417734 | KY417768 | KY417700 | KY417802 | NA |

| C. longispora | CBS 144236T | Prunus domestica | California, USA | MG971905 | NA | MG972054 | NA | MG971615 |

| C. lumnitzericola | MFLUCC 17-0508T | Lumnitzera racernosa | Tailand | MG975778 | MH253461 | MH253457 | MH253453 | NA |

| C. macropycnidia | Kern907 | Vitis vinifera | USA | OP038094 | OP076935 | OP003977 | OP095265 | OP106954 |

| C. mali | CFCC 50030 | Malus pumila | Shanxi, China | MH933643 | MH933677 | MH933550 | MH933608 | MH933524 |

| C. mali | CFCC 50031 | Crataegus sp. | Shanxi, China | KR045636 | KR045716 | KU711004 | KU710965 | KU710927 |

| C. mali-spectabilis | CFCC 53181T | Malus spectabilis ‘Royalty’ | Xinjiang, China | MK673066 | MK673096 | MK673036 | MK673006 | MK672953 |

| C. mali-sylvestris | MFLUCC 16-0638 | Malus sylvestris | Russia | KY885017 | KY885018 | KY885019 | KY885020 | NA |

| C. melastoma | A 846 | Malus domestica | USA | AF191184 | ||||

| C. melnikii | MFLUCC 16-0635 | Populus nigra var. italica | Russia | KY417736 | KY417770 | KY417702 | KY417804 | NA |

| C. melnikii | MFLUCC 15-0851T | Malus domestica | Russia | KY417735 | KY417769 | KY417701 | KY417803 | NA |

| C. mougeotii | ATCC 44994 | Picea abies | Norway | AY347329 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. multicollis | CBS 105.89T | Quercus ilex subsp. rotundifolia | Spain | DQ243803 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. myrtagena | CBS 116843T | Tibouchiina urvilleana | USA | AY347363 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. nitschkii | CMW 10180T | Eucalyptus globulus | Ethiopia | AY347356 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. nivea | MFLUCC 15-0860 | Salix acutifolia | Russia | KY417737 | KY417771 | KY417703 | KY417805 | NA |

| C. nivea | CFCC 89641 | Elaeagnus angustifolia | Ningxia, China | KF765683 | KF765699 | KU711006 | KU710967 | KU710929 |

| C. notastroma | NE_TFR5 | Populus tremuloides | USA | JX438632 | NA | NA | NA | JX438543 |

| C. notastroma | NE_TFR8 | Populus tremuloides | USA | JX438633 | NA | NA | NA | JX438542 |

| C. ochracea | CFCC 53164T | Cotoneaster sp. | Xinjiang, China | MK673060 | MK673090 | MK673030 | MK673001 | MK672949 |

| C. oleicola | CBS 144248T | Olea europaea | California, USA | MG971944 | NA | MG972098 | NA | MG971660 |

| C. olivacea | CFCC 53176T | Sorbus tianschanica | Xinjiang, China | MK673068 | MK673098 | MK673038 | MK673008 | MK672955 |

| C. olivacea | CFCC 53177 | Prunus virginiana | Xinjiang, China | MK673071 | MK673101 | MK673041 | MK673011 | NA |

| C. olivarum | CBS 145585T | Olea europaea | California, USA | MK514094 | NA | MK509030 | NA | MK509025 |

| C. palm | CXY 1276 | Cotinus coggygria | Beijing, China | JN402990 | NA | NA | NA | KJ781296 |

| C. palm | CXY 1280T | Cotinus coggygria | Beijing, China | JN411939 | NA | NA | NA | KJ781297 |

| C. paracinnamomea | CFCC 55453T | Salix matsudana | Gansu, China | MZ702594 | NA | OK303456 | OK303515 | OK303576 |

| C. paracinnamomea | CFCC 55454 | Salix matsudana | Gansu, China | MZ702597 | NA | OK303459 | OK303518 | OK303579 |

| C. parakantschavelii | MFLUCC 15-0857T | Populus × sibirica | Russia | KY417738 | KY417772 | KY417704 | KY417806 | NA |

| C. parapersoonii | T28.1T | Prunus persica | USA | AF191181 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. parapistaciae | CBS 144506T | Pistacia vera | California, USA | MG971804 | NA | MG971954 | NA | MG971519 |

| C. paraplurivora | FDS-564T | Prunus persica var. nucipersica | Canada | OL640183 | OL640185 | OL631587 | NA | OL631590 |

| C. paraplurivora | FDS-623 | Prunus persica var. persica | Canada | OL640181 | OL640123 | OL631588 | NA | OL631591 |

| C. parasitica | MFLUCC 15-0507T | Malus domestica | Russia | KY417740 | KY417774 | KY417706 | KY417808 | NA |

| C. parasitica | XJAU 2542-1 | Malus sp. | Xinjiang, China | MH798884 | MH798897 | NA | NA | MH813452 |

| C. paratranslucens | MFLUCC 15-0506T | Populus alba var. bolleana | Russia | KY417741 | KY417775 | KY417707 | KY417809 | NA |

| C. paratranslucens | MFLUCC 16-0627 | Populus alba | Russia | KY417742 | KY417776 | KY417708 | KY417810 | NA |

| C. pavettae | CBS 145562T | Pavetta revoluta | South Africa | MK876386 | MK876427 | MK876457 | MK876483 | MK876497 |

| C. phialidica | MFLU 16-2442T | Alnus glutinosa | Italy | MT177932 | MT177959 | NA | MT432209 | MT454014 |

| C. phitsanulokensis | MFLUCC 21-0046T | unidentified decaying leaves | Phitsanulok, Thailand | MZ356517 | MZ356521 | MZ451160 | MZ451168 | MZ451164 |

| C. piceae | CFCC 52841T | Picea crassifolia | Xinjiang, China | MH820398 | MH820391 | MH820406 | MH820395 | MH820402 |

| C. piceae | CFCC 52842 | Picea crassifolia | Xinjiang, China | MH820399 | MH820392 | MH820407 | MH820396 | MH820403 |

| C. pingbianensis | MFLUCC 18-1204T | Undefined wood | Yunnan, China | MK912135 | MK571763 | MN685817 | NA | NA |

| C. pini | CBS 197.42 | Pinus sylvestris | Switzerland | AY347332 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. pini | CBS 224.52T | Pinus strobus | USA | AY347316 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. pistaciae | CBS 144238T | Pistacia vera | California, USA | MG971802 | NA | MG971952 | NA | MG971517 |

| C. platanicola | MFLU 17-0327 | Platanus hybrida | Italy | MH253451 | MH253452 | MH253449 | MH253450 | NA |

| C. platycladi | CFCC 50504T | Platycladus orientalis | Yunnan, China | MH933645 | MH933679 | MH933552 | MH933610 | MH933516 |

| C. platycladi | CFCC 50505 | Platycladus orientalis | Yunnan, China | MH933646 | MH933680 | MH933553 | MH933611 | MH933517 |

| C. platycladicola | CFCC 50038T | Platycladus orientalis | Gansu, China | KT222840 | MH933682 | MH933555 | MH933613 | MH933519 |

| C. platycladicola | CFCC 50039 | Platycladus orientalis | Gansu, China | KR045642 | KR045721 | KU711008 | KU710973 | KU710931 |

| C. plurivora | CBS 144239T | Olea europaea | California, USA | MG971861 | NA | MG972010 | NA | MG971572 |

| C. populi | CFCC 55472T | Populus sp. | Gansu, China | MZ702609 | NA | OK303471 | OK303530 | OK303591 |

| C. populi | CFCC 55473 | Populus sp | Gansu, China | MZ702610 | OK303472 | OK303531 | OK303592 | |

| C. populicola | CBS 144240T | Populus deltoides | California, USA | MG971891 | NA | MG972040 | NA | MG971601 |

| C. populina | CFCC 89644T | Salix psammophila | Shaanxi, China | KF765686 | KF765702 | KU711007 | KU710969 | KU710930 |

| C. populinopsis | CFCC 50032T | Sorbus aucuparia | Ningxia, China | MH933648 | MH933683 | MH933556 | MH933614 | MH933520 |

| C. predappioensis | MFLUCC 17-2458T | Platanus hybrida | Italy | MG873484 | MG873480 | NA | NA | NA |

| C. pruinopsis | CFCC 50034T | Ulmus pumila | Shaanxi, China | KP281259 | KP310806 | KP310836 | KU710970 | KP310849 |

| C. pruinopsis | CFCC 50035 | Ulmus pumila | Jilin, China | KP281260 | KP310807 | KP310837 | KU710971 | KP310850 |

| C. pruinosa | CBS 201.42T | Syringa sp. | Switzerland | DQ243801 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. pruinosa | CFCC 50036 | Syringa oblata | Qinghai, China | KP310800 | KP310802 | KP310832 | NA | KP310845 |

| C. prunicola | MFLU 17-0995T | Prunus sp. | Italy | MG742350 | MG742351 | MG742353 | MG742352 | NA |

| C. pruni-mume | CFCC 53179 | Prunus armeniaca | Xinjiang, China | MK673057 | MK673087 | MK673027 | NA | MK672947 |

| C. pruni-mume | CFCC 53180T | Prunus mume | Xinjiang, China | MK673067 | MK673097 | MK673037 | MK673007 | MK672954 |

| C. pubescentis | MFLUCC 18-1201T | Quercus pubescens | Forlì-Cesena, Italy | MK912130 | MK571758 | MN685812 | NA | NA |

| C. punicae | CBS 144244 | Punica granatum | California, USA | MG971943 | NA | MG972091 | NA | MG971654 |

| C. quercicola | MFLU 17-0881 | Quercus sp. | Italy | MF190128 | MF190074 | NA | NA | NA |

| C. quercicola | MFLUCC 14-0867T | Quercus sp. | Italy | MF190129 | MF190073 | NA | NA | NA |

| C. quercinum | CFCC 53133T | Quercus mongolica | China | MT360045 | MT360033 | MT363982 | MT363991 | MT364001 |

| C. quercinum | CFCC 53132 | Quercus mongolica | China | MT360044 | MT360032 | MT363981 | MT363990 | MT364000 |

| C. rhizophorae | MUCC302 | Eucalyptus grandis | Australia | EU301057 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. ribis | CFCC 50026 | Ulmus pumila | Qinghai, China | KP281267 | KP310813 | KP310843 | KU710972 | KP310856 |

| C. ribis | CFCC 50027 | Ulmus pumila | Qinghai, China | KP281268 | KP310814 | KP310844 | NA | KP310857 |

| C. rosae | MFLU 17-0885 | Rosa canina | Italy | MF190131 | MF190076 | NA | NA | NA |

| C. rosicola | CF 20197024T | Rosa sp. | Tibet, China | MK673079 | MK673109 | MK673049 | MK673019 | MK672965 |

| C. rosigena | MFLUCC 18-0921T | Rosa sp. | Russia | MN879872 | MN879873 | NA | NA | NA |

| C. rostrata | CFCC 89909T | Salix cupularis | Gansu, China | KR045643 | KR045722 | KU711009 | KU710974 | KU710932 |

| C. rostrata | CFCC 89910 | Salix cupularis | Gansu, China | KR045644 | KR045723 | KU711010 | KU710975 | KU710933 |

| C. rusanovii | MFLUCC 15-0854T | Salix babylonica | Russia | KY417744 | KY417778 | KY417710 | KY417812 | NA |

| C. salicacearum | MFLUCC 15-0861 | Salix × fragilis | Russia | KY417745 | KY417779 | KY417711 | KY417813 | NA |

| C. salicacearum | MFLUCC 15-0509T | Salix alba | Russia | KY417746 | KY417780 | KY417712 | KY417814 | NA |

| C. salicicola | MFLUCC 14-1052T | Salix alba | Russia | KU982636 | KU982635 | KU982637 | NA | NA |

| C. salicina | MFLUCC 15-0862T | Salix alba | Russia | KY417750 | KY417784 | KY417716 | KY417818 | NA |

| C. salicina | MFLUCC 16-0637 | Salix × fragilis | Russia | KY417751 | KY417785 | KY417717 | KY417819 | NA |

| C. salicis-albae | MFLUCC 18-0485 | Salix alba | Russia | MT734820 | MT734819 | OL754585 | OL754584 | NA |

| C. schulzeri | CFCC 50040 | Malus domestica | Ningxia, China | KR045649 | KR045728 | KU711013 | KU710980 | KU710936 |

| C. schulzeri | CFCC 50042 | Malus pumila | Gansu, China | KR045650 | KR045729 | KU711014 | KU710981 | KU710937 |

| C. shoreae | MFLUCC 21-0047T | Shorea sp. | Chiang Mai,Thailand | MZ356515 | MZ356519 | MZ451158 | MZ451166 | MZ451162 |

| C. shoreae | MFLUCC 21-0048 | Shorea sp. | Chiang Mai,Thailand | MZ356516 | MZ356516 | MZ356516 | MZ356516 | MZ356516 |

| C. sibiraeae | CFCC 50045T | Sibiraea angustata | Gansu, China | KR045651 | KR045730 | KU711015 | KU710982 | KU710938 |

| C. sibiraeae | CFCC 50046 | Sibiraea angustata | Gansu, China | KR045652 | KR045731 | KU711015 | KU710983 | KU710939 |

| C. sophorae | CFCC 50048 | Magnolia grandiflora | Shanxi, China | MH820401 | MH820394 | MH820409 | MH820397 | MH820405 |

| C. sophorae | CFCC 89598 | Styphnolobium japonicum | Gansu, China | KR045654 | KR045733 | KU711018 | KU710985 | KU710941 |

| C. sophoricola | CFCC 89596 | Styphnolobium japonicum var. pendula | Gansu, China | KR045656 | KR045735 | KU711020 | KU710987 | KU710943 |

| C. sophoricola | CFCC 89595T | Styphnolobium japonicum var. pendula | Gansu, China | KR045655 | KR045734 | KU711019 | KU710986 | KU710942 |

| C. sophoriopsis | CFCC 89600T | Styphnolobium japonicum | Gansu, China | KR045623 | KP310804 | KU710992 | KU710951 | KU710915 |

| C. sorbi | MFLUCC 16-0631T | Sorbus aucuparia | Russia | KY417752 | KY417786 | KY417718 | KY417820 | NA |

| C. sorbicola | MFLUCC 16-0584T | Acer pseudoplatanus | Russia | KY417755 | KY417789 | KY417721 | KY417823 | NA |

| C. sorbicola | MFLUCC 16-0633 | Cotoneaster melanocarpus | Russia | KY417758 | KY417792 | KY417724 | KY417826 | NA |

| C. sorbina | CF 20197660T | Sorbus tianschanica | Xinjiang, China | MK673052 | MK673082 | MK673022 | NA | MK672943 |

| C. spiraeae | CFCC 50049T | Spiraea salicifolia | Gansu, China | MG707859 | MG707643 | MG708196 | MG708199 | NA |

| C. spiraeae | CFCC 50050 | Spiraea salicifolia | Gansu, China | MG707860 | MG707644 | MG708197 | MG708200 | NA |

| C. spiraeicola | CFCC 53138T | Spiraea salicifolia | Beijing, China | MN854448 | MN854659 | NA | MN850749 | MN850756 |

| C. spiraeicola | CFCC 53139 | Tilia nobilis | Beijing, China | MN854449 | MN854660 | NA | MN850750 | MN850757 |

| C. tamaricicola | CFCC 50508T | Tamarix chinensis | Yunnan, China | MH933652 | MH933687 | MH933560 | MH933617 | MH933523 |

| C. tanaitica | MFLUCC 14-1057T | Betula pubescens | Russia | KT459411 | KT459412 | KT459413 | NA | NA |

| C. thailandica | MFLUCC 17-0262T | Xylocarpus moluccensis | Thailand | MG975776 | MH253463 | MH253459 | MH253455 | NA |

| C. thailandica | MFLUCC 17-0263T | Xylocarpus moluccensis | Thailand | MG975777 | MH253464 | MH253460 | MH253456 | NA |

| C. tibetensis | CF 20197026 | Cotoneaster sp. | Tibet, China | MK673076 | MK673106 | MK673046 | MK673016 | MK672962 |

| C. tibetensis | CF 20197032T | Cotoneaster sp. | Tibet, China | MK673078 | MK673108 | MK673048 | MK673018 | MK672964 |

| C. tibouchinae | CPC 26333T | Tibouchina semidecandra | France | KX228284 | KX228335 | NA | NA | NA |

| C. translucens | CXY 1351 | Populus davidiana | Inner Mongolia, China | KM034874 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. ulmi | MFLUCC 15-0863T | Ulmus minor | Russia | KY417759 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. ulmicola | MFLUCC 18-1227T | Ulmus pumila | Russia | MH940220 | MH940218 | MH940216 | NA | NA |

| C. unilocularis | MFLUCC 15-0481T | Tamarix sp. | Italy | KU900332 | KU900304 | NA | KX011166 | NA |

| C. valsoidea | CMW 4309T | Eucalyptus grandis | Indonesia | AF192312 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. variostromatica | CMW 6766T | Eucalyptus globulus | Australia | AY347366 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. variostromatica | CMW 1240 | Eucalyptus grandis | South Africa | AF260263 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C. verrucosa | CFCC 53157T | Platycladus orientalis | Beijing, China | MW418408 | MW418420 | NA | MW422911 | MW422923 |

| C. verrucosa | CFCC 53158 | Platycladus orientalis | Beijing, China | MW418410 | MW418422 | MW422901 | MW422913 | MW422925 |

| C. vinacea | CBS 141585T | Vitis interspecific hybrid ‘Vidal’ | USA | KX256256 | NA | NA | NA | KX256277 |

| C. viridistroma | CBS 202.36T | Cercis canadensis Castigl | USA | MN172408 | MN172388 | NA | NA | MN271853 |

| C. viticola | Cyt2 | Vitis interspecific hybrid ‘Frontenac’ | USA | KX256238 | NA | NA | NA | KX256259 |

| C. viticola | CBS 141586T | Vitis vinifera ‘Cabernet Franc’ | USA | KX256239 | NA | NA | NA | KX256260 |

| C. xinglongensis | CFCC 52458 | Castanea mollissima | China | MK432622 | MK429892 | MK442946 | MK578082 | NA |

| C. xinglongensis | CFCC 52459 | Castanea mollissima | China | MK432623 | MK429893 | MK442947 | MK578083 | NA |

| C. xinjiangensis | CFCC 53182 | Rosa sp. | Xinjiang, China | MK673064 | MK673094 | MK673034 | MK673004 | MK672951 |

| C. xinjiangensis | CFCC 53183T | Rosa sp. | Xinjiang, China | MK673065 | MK673095 | MK673035 | MK673005 | MK672952 |

| C. xylocarpi | MFLUCC 17-0251T | Xylocarpus granatum | Thailand | MG975775 | MH253462 | MH253458 | NA | NA |

| C. yakimana | Bent902/CBS 149297 | Vitis vinifera | USA | OM976602 | ON059350 | ON012555 | ON045093 | ON012569 |

| C. yakimana | Bent903/CBS 149298 | Vitis vinifera | USA | OM976603 | ON059351 | ON012556 | ON045094 | ON012570 |

| C. zhaitangensis | CFCC 56227T | Euonymus japonicus | China | OQ344750 | NA | OQ410623 | OQ398733 | OQ398760 |

| C. zhaitangensis | CFCC 57537 | Euonymus japonicus | China | OQ344751 | NA | OQ410624 | OQ398734 | OQ398761 |

| Diaporthe eres | CBS 145040 | Lactuca satia | Netherlands | MK442579 | MK442521 | MK442634 | MK442663 | MK442693 |

| Diaporthe vaccinii | CBS 160.32 | Vaccinium macrocarpon | USA | KC343228 | NA | JQ807297 | NA | KC343954 |

aATCC: American Type Culture Collection, Virginia, USA; CBS: Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute (CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre), Utrecht, The Netherlands; CFCC: China Forestry Culture Collection Centre, Beijing, China; CMW: Culture collection of Michael Wingfield, University of Pretoria, South Africa; CPC: Culture collection of Pedro Crous, The Netherlands; IMI: Culture collection of the International Mycological Institute, CABI Bioscience, Egham, Surrey, UK; MFLU: Mae Fah Luang University herbarium, Thailand; MFLUCC: Mae Fah Luang University Culture Collection, Thailand; MUCC: Murdoch University Culture Collection, Perth, Australia; NE: Gerard Adams collections, University of Nebraska, Lincoln NE, USA; XJAU: Xinjiang Agricultural University, Xinjiang, China; IRAN: the Fungal Culture Collection of the Iranian Research Institute of Plant Protection; FCCUU: Fungal Culture Collection of Urmia University. NA: not applicable. All the new isolates used in this study are in bold and the type materials are marked with T.

The newly generated sequences were checked and trimmed manually in BioEdit v. 7.2.670 and deposited in GenBank (Table 3). Sequences based on the combined dataset (ITS-rDNA, LSU, act1, rpb2, and tef1-α) were aligned using the MAFFT v. 7 online service (https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/)71 for each locus separately by including the sequences of ex-type and representative Cytospora strains available in the literature and adjusted where necessary. The concatenated sequence dataset (ITS-rDNA, LSU, act1, rpb2, and tef1-α) was produced in Mesquite v. 2.7472 and used for phylogenetic analysis. Multi-gene phylogenetic analyses were done by using Maximum Likelihood (ML), Maximum Parsimony (MP), and Bayesian Inference (BI) methods. ML analysis was conducted in RAxML-HPC BlackBox v. 8.2.1273 provided by the CIPRES Science Gateway v 3.374. The substitution model was set as GTRGAMMA+I and branch stability was estimated by 1000 bootstrap replications to produce a cladogram with nodal support values. BI was performed in MrBayes v. 3.2.775 by using the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method with four chains, 1M generations, and a temperature value of the heated chain of 0.1. Trees were saved every 1000 generations, Burn-in was set to 25%, and posterior probabilities (PP) were determined from the remaining trees. For determining the best-fit evolutionary models required for BI, all individual alignments were evaluated in MrModeltest v2.376 using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). MP analysis was performed in PAUP (Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony) v. 4.0b1077. Trees were inferred using the heuristic search option with 1000 random sequence additions and branch swapping with the tree-bisection-reconnection (TBR) algorithm and gaps were treated as missing data. The bootstrap values with 1000 replicates were performed to determine branch support. Descriptive tree statistics [Tree Length (TL), Consistency Index (CI), Retention Index (RI), and Homoplasy Index (HI)] were calculated for trees generated in the parsimony analysis. Sequences of Diaporthe eres CBS 145040 and Diaporthe vaccinii CBS 160.32 were used as outgroups. The resultant phylogenetic tree was visualized in FigTree v. 1.4.478 and edited in graphic design software, Adobe Illustrator CC 2018 (Adobe Inc., San Jose, California). The ultimate concatenated alignment and ML-generated tree file were submitted to TreeBASE (https://www.treebase.org) under the accession number 29113. Sequence data were deposited in the GenBank dataset and their accession numbers are provided in Table 3.

Morphological characterization

Purified cultures were grown on PDA medium, incubated in the dark at 25 ± 1 °C, and examined after three, seven, and 30 days. Radial growth was measured by taking two measurements perpendicular to each other in triplicates21,57,60,79. Colony color was determined based on Rayner’s color charts80. Pycnidia formation was induced on pine needles embedded in 2% water agar [20 g Agar (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) in 1000 mL distilled water] medium or on one-year-old apple shoots embedded in PDA medium and incubated under near ultraviolet (NUV) light (12 h photoperiod) at room temperature. Both pine needles and apple shoots were autoclave sterilized at 121 °C for 20 min. thrice, with a 24-h interval between each sterilization. Pycnidia formation was checked weekly for 30 days. Hand sections of the conidiomata (both transverse and longitudinal) were prepared and mounted in water or lactic acid and examined for morphological details. Macro-morphological characters including size and arrangement of stromata, presence or absence of conceptacle, number, and diameter of ostioles per ectostromatic disk, arrangement of locules and color, shape, and size of discs were examined using an Olympus SZX-ILLB200 dissecting microscope. Micro-morphological characters including the shape and size of conidia (n = 50) and conidiophores/conidiogenous cells (n = 25) were determined at 1000× magnification under an Olympus AX70 compound microscope with differential interference contrast (DIC) illumination. Adobe Photoshop 2020 v. 2.10.8 software (Adobe Inc., San Jose, California) was used for manual editing.

Pathogenicity trials

Pathogenicity trials were done based on the standard and routine method described in the literature31,42,44,57,81–84. Detached, dormant, one- or two-year-old, 25 × 1.5–2 cm apple shoots of the cv. ʻRed Delicious’ were collected from healthy trees in the apple cultivar collection farm of Urmia University. The shoots were washed under running tap water, surface disinfested with 75% ethanol for 4 min., washed again in sterile distilled water, and blotted dry on a sterile paper towel. The bark of the shoots was removed in the center with a 5-mm-diameter flame sterilized cork borer and inoculated with a 5 mm diameter mycelial plug of actively growing fungal isolates (7–day-old on PDA). All the obtained isolates were used in pathogenicity trials. Each inoculated site was covered with a sterile moistened cotton ball and wrapped with Parafilm™ (Bemis™, pm996, USA) to maintain the moisture. Sterile PDA plugs were used as the controls. Six shoots were used for each fungal isolate and control treatment. Inoculated shoots were placed in clean plastic containers containing three layered moistened sterile paper towels and incubated under laboratory conditions (diurnal light, 25 ± 2 °C, 80% relative humidity) for 21 days. All the experiments were repeated once under similar conditions. Length of bark and wood discoloration around the inoculated sites were measured 21 days post-inoculation. Also, the pathogenicity of the most virulent isolate (BA 2-4) was determined on the ‘Red Delicious’ cultivar under field conditions. Four 2–3-year-old branches in four geographical directions were selected. The bark of the branches was surface disinfected by spraying with 75% ethanol, and the fungal inoculation was the same as described for detached shoots. Inoculation was done on April 7, 2023, and the results were evaluated on May 24, 2023.

In addition, five fungal isolates (BA 1-1, BA 2-1, BA 2-4, KU 1-1, and BA 3-1 isolates) which had the highest virulence in the trials as mentioned above (Table 1) were chosen for the evaluation of reaction of 12 apple cultivars including ʻBraeburn’, ʻDelbard Estivale’, ʻFuji’, ʻGranny Smith’, ʻGolden Delicious’, ʻGolden Primrose’, ʻIdared’, ʻRed Delicious’, ʻM4’, ʻM7’, ʻMM106’ and ʻMM109’ against these isolates. Healthy shoots were collected from the apple cultivar collection farm of Urmia University and used for pathogenicity tests as described above and the length of bark and wood discoloration around the inoculated sites was measured 21 days post-inoculation. Experiments were laid down following a completely randomized design (CRD). The pathogenicity data were transformed by square root due to the existence of zero values and were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SAS v.9.1 software (SAS Institute, Inc., USA). The lesion length means were compared with Duncan’s multiple range test (P ≤ 0.05). To confirm Koch’s postulates, fungal re-isolation was carried out from the margins of the developed lesions in all symptomatic samples, and isolates were re-identified morphologically as described previously.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr. Alireza Poursafar for his help during the study and the Research Deputy of Urmia University for financial support. Also, we thank anonymous reviewers for their careful review of this manuscript and for giving explanatory suggestions.

Author contributions

Y.G. and A.A. designed and supervised the project . R.A. and Y.G. performed sampling, fungal isolation, experiments and photography. R.A. and A.A. carried out statistical and phylogenetic analyses. Y.G. wrote the main manuscript text and R.A. and A.A. prepared the figures 1-5. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

All sequence data generated in this study are available in NCBI GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) following the accession numbers MZ948960-MZ948962 (ITS); MZ948957-MZ948959 (LSU); MZ997842-MZ997844 (act1); MZ997845-MZ997847 (rpb2) and MZ997848-MZ997850 (tef1α). Also, the ultimate concatenated alignment and ML-generated tree file were submitted to TreeBASE (https://www.treebase.org) under the accession number 29113. All data analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-57235-3.

References

- 1.Malladi A. Molecular physiology of fruit growth in apple. Hortic. Rev. 2020;47:1–42. doi: 10.1002/9781119625407.ch1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies T, Watts S, McClure K, Migicovsky Z, Myles S. Phenotypic divergence between the cultivated apple (Malus domestica) and its primary wild progenitor (Malus sieversii) PloS ONE. 2021;17:e0250751. doi: 10.1101/2021.04.14.439783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2020, accessed 28 Jan 2021). http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL/visualize.

- 4.Jackson JE. Biology of Apples and Pears. Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luby, J. J. Taxonomic classification and brief history. In Apples: Botany, Production and Uses (eds. Ferree, D.C. & Warrington, I. J.) 1–14 (CAB International, 2003).

- 6.Volk, G. M., Cornille, A., Durel, C.-E. & Gutierrez, B. Botany, taxonomy and origins of the apple. In The Apple Genome, Compendium of Plant Genomes (ed. Korban, S. S.) 19–32 (Springer, 2021).

- 7.Janick, J., Cummins, J. N., Brown, S. K. & Hemmat, M. Apples. In Fruit Breeding: Tree and Tropical Fruits (eds. Janick, J. & Moore, J. N.) 1–77 (Wiley, 1996).

- 8.Yousefzadeh H, et al. Biogeography and phylogenetic relationships of Hyrcanian wild apple using cpDNA and ITS noncoding sequences. Syst. Biodivers. 2019;17:295–307. doi: 10.1080/14772000.2019.1583689. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gharghani A, et al. Genetic identity and relationships of Iranian apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.) cultivars and landraces, wild Malus species, and representative old apple cultivars based on simple sequence repeat (SSR) marker analysis. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2009;56:829–842. doi: 10.1007/s10722-008-9404-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmadi, K., Ebadzadeh, H. R., Hatami, F., Hoseinpour, R. & Abdshah, H. Agricultural Statistics, vol. 3. Horticultural Crops (Ministry of Agriculture-Jahad, Planning and Economic Affairs, Communication and Information Technology Center, 2021).

- 11.Smit WA, Viljoen CD, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ, Calitz FJ. A new canker disease of apple, pear and plum rootstocks caused by Diaporthe ambigua in South Africa. Plant Dis. 1996;80:1331–1335. doi: 10.1094/PD-80-1331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cloete M, Fourie PH, Damm U, Crous PW, Mostert L. Fungi associated with die-back symptoms of apple and pear trees, a possible inoculum source of grapevine trunk disease pathogens. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2011;50:176–190. doi: 10.14601/Phytopathol_Mediterr-9004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutton TB, Aldwinckle HS, Agnello AM, Walgenbach JF. Compendium of Apple and Pear Diseases and Pests. 2. APS Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Havenga M, et al. Canker and wood rot pathogens in young apple trees and propagation material in the Western Cape of South Africa. Plant Dis. 2019;103:3129–3141. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-04-19-0867-RE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azizi R, Ghosta Y, Ahmadpour A. New fungal canker pathogens of apple trees in Iran. J. Crop Prot. 2020;9:669–681. [Google Scholar]

- 16.López-Moral A, et al. Aetiology of branch dieback, panicle and shoot blight of pistachio associated with fungal trunk pathogens in southern Spain. Plant Pathol. 2020;69:1237–1269. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan M, Zhu H, Bonthond G, Tian C, Fan X. High diversity of Cytospora associated with canker and dieback of Rosaceae in China, with 10 new species described. Front. Plant Sci. 2020;11:690. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nourian A, Salehi M, Safaie N, Khelghatibana F, Abdollahzadeh J. Fungal canker agents in apple production hubs of Iran. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:22646. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-02245-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forte AV, Ignatov AN, Ponomarenko VV, Dorokhov DB, Savelyev NI. Phylogeny of Malus (apple tree) species, inferred from the morphological traits and molecular DNA analysis. Russ. J. Genet. 2002;38:1150–1161. doi: 10.1023/A:1020648720175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adams GC, Roux J, Wingfield MJ, Common R. Phylogenetic relationships and morphology of Cytospora species and related teleomorphs (Ascomycota, Diaporthales, Valsaceae) from Eucalyptus. Stud. Mycol. 2005;52:1–149. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawrence DP, et al. Molecular phylogeny of Cytospora species associated with canker diseases of fruit and nut crops in California, with the descriptions of ten new species and one new combination. IMA Fungus. 2018;9:333–370. doi: 10.5598/imafungus.2018.09.02.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang N, Yang Q, Fan XL, Tian CM. Identification of six Cytospora species on Chinese chestnut in China. MycoKeys. 2020;62:1–25. doi: 10.3897/mycokeys.62.47425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shang QJ, et al. Additions to the genus Cytospora with sexual morph in Cytosporaceae. Mycosphere. 2020;11:189–224. doi: 10.5943/mycosphere/11/1/2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schoeneweiss DF. Drought predisposition to Cytospora canker in blue spruce. Plant Dis. 1983;67:383–385. doi: 10.1094/PD-67-383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dudley MM, Tisserat NA, Jacobi WR, Negron J, Stewart JE. Pathogenicity and distribution of two species of Cytospora on Populus tremuloides in portions of the Rocky Mountains and Midwest in the United States. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020;468:118168. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan M, Zhu H, Tian C, Huang M, Fan X. Assessment of Cytospora isolates from conifer cankers in China, with the descriptions of four new Cytospora species. Front. Plant Sci. 2021;12:636460. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.636460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ke X, Huang L, Han Q, Gao X, Kang Z. Histological and cytological investigations of the infection and colonization of apple bark by Valsa mali var. mali. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2013;42:85–93. doi: 10.1007/s13313-012-0158-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang ST, et al. New understanding of infection process of Valsa canker of apple in China. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2016;146:531–540. doi: 10.1007/s10658-016-0937-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meng XL, et al. Latent infection of Valsa mali in the seeds, seedlings and twigs of crabapple and apple trees is a potential inoculum source of Valsa canker. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:7738. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-44228-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang X, Shi C-M, Gleason ML, Huang L. Fungal species associated with apple Valsa canker in East Asia. Phytopathol. Res. 2020;2:35. doi: 10.1186/s42483-020-00076-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang XL, Wei JL, Huang LL, Kang ZS. Re-evaluation of pathogens causing Valsa canker on apple in China. Mycologia. 2011;103:317–324. doi: 10.3852/09-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Azizi R, Ghosta Y, Ahmadpour A. Morphological and molecular characterization of Cytospora species involved in apple decline in Iran. Mycol. Iran. 2020;7:205–218. doi: 10.22043/mi.2021.123907. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farr, D. F. & Rossman, A. Y. Fungal Databases, U.S. National Fungus Collections, ARS, USDA (2022, accessed 28 Jan 2022). https://nt.ars-grin.gov/fungaldatabases/.

- 34.Hanifeh S, Zafari D, Soleimani M-J, Arzanlou M. Multiple phylogeny, morphology, and pathogenicity trials reveal novel Cytospora species involved in perennial canker disease of apple trees in Iran. Fungal Biol. 2022;126:707–726. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2022.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ashkan M, Hedjaroude GA. Studies on Cytospora rubescens, a new fungus isolated from apple trees in Iran. Iran. J. Plant Pathol. 1993;29:29–30. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mehrabi ME, Mohammadi GE, Fotouhifar KB. Studies on Cytospora canker disease of apple trees in Semirom region of Iran. J. Agric. Technol. 2011;7:967–982. [Google Scholar]