Abstract

Background

Cats in Iran are definitive hosts for several zoonotic intestinal helminths, such as Toxocara cati, Dipylidium caninum, Toxascaris leonina, Physaloptera praeputialis and Diplopylidium nolleri.

Objective

This study aimed to determine the prevalence of intestinal helminth infection in free‐roaming cats in southeast Iran, a region with a high free‐roaming cat population.

Methods

From January 2018 to December 2021, 153 cadavers of free‐roaming cats from Southeast Iran were necropsied for intestinal helminth infections. The carcasses were dissected, and the digestive systems were removed. The esophagus, stomach, small intestine, caecum and colon were tightly ligated. All adult helminths were collected, preserved and identified.

Results

The prevalence of gastrointestinal helminth infections was 80.39% (123/153). Of the cats from Kerman, 73% (73/100) were infected with at least one helminth, including D. caninum 70% (70/100), T. leonina 8% (8/100) and P. praeputialis 17% (17/100). Concurrent infection with two helminth species was found in 16% (16/100) and of three species infections was found in 3% (3/100) of the cats. Of the cats from Zabol, 94.33% (50/53) were infected with at least one of the helminths, including D. caninum 69.81% (37/53), T. leonina 11.32% (6/53), P. praeputialis 37.73% (20/53) and T. cati 5.66% (3/53). Concurrent infection with two helminth species was found in 28.3% (15/53), and three species were found in 1.88% (1/53) of the cats. Helminth infections were more prevalent in older cats. There was no association between sex and infection rate.

Conclusion

Based on the very high prevalence of zoonotic intestinal helminth infections in free‐roaming cats in southeast Iran, the potential public health risk emphasizes the need for intersectoral collaboration, particularly the provision of health and hygiene education to high‐risk populations, such as pre‐school and school‐age children.

Keywords: helminth prevalence; Physaloptera praeputialis, Toxocara cati ; zoonotic parasites

Cats were introduced as definitive hosts for several zoonotic intestinal helminths, such as Toxocara cati, Dipylidium caninum, Toxascaris leonina, Physaloptera praeputialis, Diplopylidium nolleri, Physaloptera praeputialis, Ancylostoma tubaeforme and Joyeuxiella pasquale in different parts of Iran. The high prevalence of zoonotic parasites and intestinal helminth infections in free‐roaming cats in southeast Iran highlights the potential public health risks as well as environmental contamination. The high prevalence of gastrointestinal helminths parasites suggests high health risks for humans living in these endemic parts. Control of parasitic zoonoses and soil‐transmitted helminths requires intersectoral collaboration about health and hygiene education for high‐risk populations, especially pre‐school and school‐age children.

1. INTRODUCTION

According to the Iranian Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (IRAN, SPCA) announcement, more than 90% of cats (Felis catus) in Iran are free‐roaming, and the majority of household cats in Iran are raised as semi‐outdoor pets (Akhtardanesh et al., 2010). Free‐roaming cats are not subject to geographical restrictions and live in both urban and rural areas where they are in close contact with owned cats and people (Brozou et al., 2023). They disperse organisms such as helminth eggs, parasitic larvae and protozoan cysts into the public environment, thus posing an infection risk (Arbabi & Hooshyar, 2009; Borji et al., 2011). Gastrointestinal parasites worldwide pose a significant risk for both cats and humans (Beigi et al., 2017; Kostopoulou et al., 2017; Sauda et al., 2019; Szwabe & Błaszkowska, 2017). Moreover, it is believed that the close association between cats and humans is the cause of the high endemicity of certain zoonotic diseases, such as toxocariasis (Dantas‐Torres & Otranto, 2014; Overgaauw et al., 2020; Torgerson & Macpherson, 2011).

Cestodes, nematodes and acanthocephalans have been identified in the intestines of free‐roaming cats and pet cats in multiple countries (Adhikari et al., 2023; Darabi et al., 2021). In addition to the health implications for the cats themselves, this highlights the potential zoonotic risk via direct cat/human interactions or indirectly via contact with contaminated soil, food, water or fomites (Saba & Balwan, 2021; Shaheen, 2022). Establishing the prevalence of such infections helps us to better understand the potential health implications and facilitates the development of appropriate control programmes (Darabi et al., 2021).

Iran has a huge free‐roaming cat population, and as most are forced to scavenge for food in trash cans, dumpsters and hunters of rodents, their gastrointestinal infection rate is likely to be high (Beigi et al., 2017; Mirzaei et al., 2016). Therefore, cat parasite prevalence is an important issue in Iran. The prevalence of feline gastrointestinal parasites in various Iranian localities has been reported, but data from the southeast region of Iran is very limited (Hajipour et al., 2016). This study aimed to improve our understanding of helminth prevalence in the free‐roaming cat population of southeast Iran, one of the regions with a high cat population.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Geographical study area

The study area comprised Kerman and Zabol, two highly populated cities in southern Iran, which were chosen due to their high free‐roaming cat populations. The city of Kerman is located in the southeast of Iran, at 30°17′13″ N and 57°04′09″ E, and has an average elevation of about 1755 m above sea level. There is a moderate climate in Kerman and 135 mm of rainfall annually. The climate of Kerman is hot during the summers and arid during the winters due to its proximity to the Kavir‐e Lut desert.

Zabol is located in the Sistan and Baluchestan province in southeastern Iran. Its geographical coordinates are 31.0294° N latitude and 61.4974° E longitude. Due to its barren surroundings and desert landscapes, the city experiences hot, dry weather throughout the year.

2.2. Sampling

From January 2018 to December 2021, cadavers from a total of 153 free‐roaming cats were enrolled in the study. The cats had all been presented for veterinary assessment and referred by a volunteer animal rescuer after having sustained severe acute trauma due to vehicle accidents or high‐rise syndrome. Lesions included spinal trauma, severe head trauma, complicated pelvic or jaw fractures and diaphragmatic rupture, and, in all cases, euthanasia (using intravascular Propofol 10 mg/kg injection, Bayer) had been performed due to a lack of viable treatment options. Following routine post‐mortem examination by the attending veterinarian, the carcasses were transferred to the parasitology laboratory for further analysis.

2.3. Necropsy examination and parasite detecting

All necropsies were stored at 2°C, and necropsies were completed within 2 h of euthanasia. The carcasses were dissected, and the digestive systems were removed. The oesophagus, stomach, small intestine, caecum and colon were tightly ligated with gauze during dissection. The intestinal content was subsequently scraped from the mucosa of each region using a spatula. In order to remove faecal debris, the intestinal contents were passed through a sieve (60 µm pore size) and gathered in a separate beaker. Universal bottles containing equal amounts of formalin solution were then used to separate and identify the sediments, which were placed in equal amounts of warm formalin solution for further investigation. All adult helminths were collected, preserved and identified as described earlier (Anderson et al., 2009; Gibbons, 2010; Yamaguti, 1961). For the identification and counting of nematodes and tapeworms, the nematodes were mounted and stained with lactophenol. The tapeworms were mounted and stained with acid alum carmine. The number of each individual species present in each cadaver was documented. In order to determine the number of Dipylidium caninum, it was necessary to count the scoleces. Identification was performed using the key described by Vicente et al. (1997) and Soulsby (1968).

2.4. Statistical analysis

In order to analyse the data, the animals were grouped according to age based on the dental formula (0–1 year, 1–3 years and over 3 years) and gender (males and females) using clinical examination. The comparative prevalence of intestinal parasites in each age group and gender category was analysed using the chi‐squared test. Statistical testing was carried out using SPSS version 14, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

The study population comprised 153 cadavers of free‐roaming cats; 100 (55 males and 45 females) from Kerman and 53 (31 male and 22 female) from Zabol. The overall prevalence of gastrointestinal parasite infection was 80.39% (123/153).

3.1. Kerman

Necropsy examination of 100 free‐roaming cats revealed that 73% (73/100) were parasitized by at least one species of intestinal helminth. Three parasite species were identified; two species of nematodes, T. leonine 8% (8/100) (small intestines) and Physaloptera praeputialis 17% (17/100) (pyloric region of the stomach), and one cestode species, D. caninum 70% (70/100) (small intestines). There was a significant difference between older and younger cats regarding the proportion of helminth infections (p < 0.05) (Table 1). Concurrent infection with two helminth species was found in 16% (16/100) and of three species infections was found in 3% (3/100) of the cats (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Prevalence of parasites in relation to age and sex of the cats in 100 free‐roaming cats of Kerman, Iran.

| Parasite | Gender | Age (year) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female (n = 45) | Male (n = 55) | <1 (n = 24) | 1–3 (n = 43) | 3> (n = 33) | |

| 33 (73.33%) | 40 (72.72%) | 13 (54.16%) | 32 (74.41%) | 28 (84.84%) | |

| Dipylidium caninum | 31 (68.88%) | 39 (70.90%) | 11 (45.83%) | 31 (72.09%) | 28 (84.84%) |

| Physaloptera praeputialis | 7 (15.55%) | 10 (18.18%) | 3 (12.5%) | 8 (18.60%) | 6 (18.18%) |

| Toxascaris leonine | 4 (8.88%) | 4 (7.27%) | 2 (8.33%) | 4 (9.30%) | 2 (6.06%) |

TABLE 2.

Different mixed infections with gastrointestinal helminthes parasites of free‐roaming cats in Kerman, Iran.

| Mixed infection | <1 (n = 24) | 1–3 (n = 43) | 3> (n = 33) | % Prevalence (n = 100) | Parasites |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single species infection | 11 | 22 | 21 | 54 | (D), (Ph) or (T) |

| Double species infection | 1 | 9 | 6 | 16 | (D + Ph), (D + T) or (Ph + T) |

| Triple species infection | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | (D + Ph + T) |

Note: (D) Dipylidium caninum, (Ph) Physaloptera praeputialis, (T) Toxascaris leonine.

3.2. Zabol

Infection with at least one helminth parasite was found in 94.33% of cats (50/53) from Zabol city. Parasites included D. caninum 69.81% (37/53), Toxascaris leonina 11.32% (6/53), P. praeputialis 37.73% (20/53) and Toxocara cati 5.66% (3/53). There was a significant difference between older and younger cats regarding the proportion of helminth infections (p < 0.05). No association was found between sex and the proportion of infections (p > 0.05). Concurrent infection with two helminth species was found in 28.3% (15/53), and three species were found in 1.88% (1/53) of the cats (Table 3; Figures 1 and 2).

TABLE 3.

Different mixed infections with gastrointestinal helminthes parasites of free‐roaming cats in Zabol, Iran.

| Mixed infection | <1 (n = 4) | 1–3 (n = 49) | % Prevalence (n = 53) | Parasites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single species infection | 0 | 33 | 62.26 | (D), (Ph), or (T) |

| Double species infection | 0 | 15 | 28.30 | (D + Ph), (D + T) or (Ph + T) |

| Triple species infection | 0 | 1 | 1.88 | (D + Ph + T) |

Note: (D) Dipylidium caninum, (Ph) Physaloptera praeputialis, (T) Toxascaris leonine.

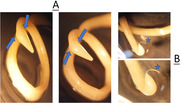

FIGURE 1.

Physaloptera praeputialis head (a) and tail (b) morphology of the male worm (10×). Physaloptera praeputialis head and tail morphology of the female worm under the loop (c and d).

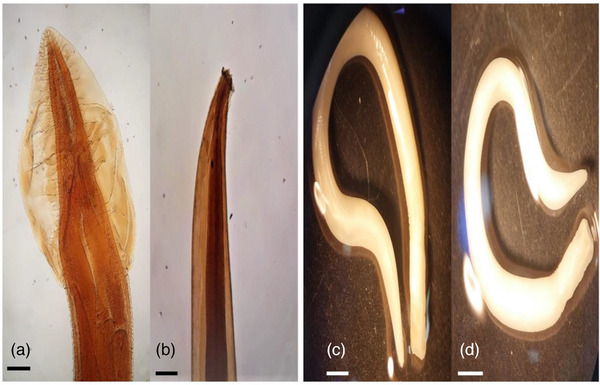

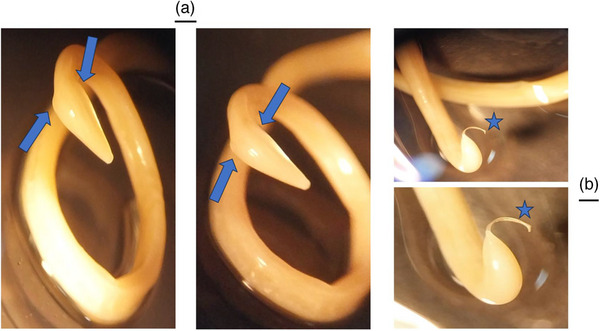

FIGURE 2.

Toxocara cati head (a) and tail (b) morphology of the male worm under the loop. The most salient feature is the presence of large, arrow‐head‐shaped cervical alae (wings) on the anterior end (blue arrows). Stars are the spicules of the male parasite.

4. DISCUSSION

Cats play a crucial role in the epidemiology of gastrointestinal helminths and play a major role in transmitting these parasites through faecal contamination of soil, food or water (Changizi et al., 2007). Soil contamination in parks, playgrounds, backyards, gardens, beaches, sandpits and other urban and rural areas constitutes public health, especially for children. The prevalence and variety of feline gastrointestinal helminths are influenced by environmental temperature, humidity and the number, living‐conditions (free‐roaming, feral, shelter, domestic) and behaviours of the local cat populations. As such, the associated zoonotic risks are dependent on geographic regions and on the social habits and behaviours of local human populations. In this study, the prevalence of helminth infection in free‐roaming cats in southeast Iran was high. Infection rates were somewhat higher in Zabol compared with Kerman, possibly as a result of the climate differences (Zabol being slightly warmer) or perhaps due to differences in the number or behaviour of the local cat populations.

The gender of the cats did not significantly influence gastrointestinal helminth prevalence. This is in agreement with previous studies in which male and female cats exhibit similar patterns of infection intensity (Arruda et al., 2021; Ola‐Fadunsin et al., 2023). On the other hand, age was a considerable risk factor for parasitic infection, specifically for D. caninum. This is in strong agreement with the results of a study of stray cats in Qatar, in which a higher prevalence of Dipylidium spp. was found in adults in comparison to juvenile cats (Abu‐Madi et al., 2008).

D. caninum, a cestode species requiring an intermediate insect host, was the most commonly observed helminth in this study and was seen at a higher prevalence (69.9%) than found in other studies (Rousseau et al., 2022). Cats can become infected by the ingestion of cysticercoids‐infected fleas or lice (Benelli et al., 2021); thus, the high prevalence in southeast Iran may be a reflection of a high flea population as well as potential climate and population differences.

Domestic cats are affected by P. praeputialis, worldwide (Mohamed et al., 2021). This gastrointestinal nematode's prevalence rate was significant in southeast Iran but was notably higher in Zabol, 37.73% (20/53), than in Kerman, 17.7% (17/100).

Toxocara species are common feline nematodes that pose significant potential health risks to both cats and humans (Barua et al., 2020; Maciag et al., 2022; Morelli et al., 2021; Zanzani et al., 2014). In the current study, their prevalence was comparatively low compared with that of P. praeputialis. The prevalence of T. leonina was roughly similar in Zabol and Kerman (8% and 11%, respectively), but T. cati was found in only three cats in Zabol. The reason for the lack of T. cati in cats from Kerman is unknown, but, clearly, it is one of the less common helminths in southeast Iran. Iran is a country in Western Asia comprising a land area of 1648,195 km2 (636,372 sq mi). It is the 2nd‐largest country in the Middle East and the 17th‐largest country globally. It is important to note that data from one particular part of such a big country with a varied ecosystem may not apply to other geographical parts (Vaghefi et al., 2019).

Understanding the comparative prevalence of helminth infections in specific regions such as Zabol and Kerman is crucial for implementing effective, targeted control measures to protect feline and human populations from potential infections.

The importance of these coproparasitology techniques in understanding helminth prevalence and anthelmintic treatment in animal health cannot be overstated (D'ambroso Fernandes et al., 2022). However, to fully understand the zoonotic risks, it is also imperative to apply similar studies in indoor pet animals, which was out of the scope of this study.

In the present study, after being separated from the intestinal contents, the worms were placed in 10% formalin. There are several reasons for this. First, Toxocara spp. are highly zoonotic and dangerous, and by doing this, we reduced the risk of contamination and spread of infection. Additionally, molecular studies were not conducted in our research, so we did not place the worms in alcohol. Furthermore, morphologically, T. cati and T. leonina have significant differences, especially in the anterior part and the rostral alae, which allow us to distinguish between these two parasites (Bowman, 2020).

5. CONCLUSION

The data from this study confirms that helminth infection of free‐roaming cats in southeast Iran is highly prevalent. As these organisms are potential zoonoses, this is likely to constitute a significant public health risk. It emphasizes that the implementation of appropriate control strategies is required, and a multimodal approach, including neutering programmes, antiparasiticidal prophylaxis, assessment restriction and human education, is likely to be most effective.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization; writing – original draft preparation; supervision: Soheil Sadr. Methodology; formal analysis and investigation; writing – review and editing: all authors. All authors checked and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication in the present journal.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING INFORMATION

No funding was received.

ETHICS STATEMENT

All applicable international, national and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. https://ethics.research.ac.ir/IR.UK.VETMED.REC.1402.010.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://www.webofscience.com/api/gateway/wos/peer‐review/10.1002/vms3.1422

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the support and interest of the technical members of the Parasitology Laboratory, especially Mr. M. Aminzadeh at Shahid Bahonar University.

Nourollahi Fard, S. R. , Akhtardanesh, B. , Sadr, S. , Khedri, J. , Radfar, M. H. , & Shadmehr, M. (2024). Gastrointestinal helminths infection of free‐roaming cats (Felis catus) in Southeast Iran. Veterinary Medicine and Science, 10, e1422. 10.1002/vms3.1422

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Abu‐Madi, M. , Pal, P. , Al‐Thani, A. , & Lewis, J. (2008). Descriptive epidemiology of intestinal helminth parasites from stray cat populations in Qatar. Journal of Helminthology, 82(1), 59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, R. B. , Dhakal, M. A. , Ale, P. B. , Regmi, G. R. , & Ghimire, T. R. (2023). Survey on the prevalence of intestinal parasites in domestic cats (Felis catus Linnaeus, 1758) in central Nepal. Veterinary Medicine and Science, 9(2), 559–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtardanesh, B. , Ziaali, N. , Sharifi, H. , & Rezaei, S. (2010). Feline immunodeficiency virus, feline leukemia virus and Toxoplasma gondii in stray and household cats in Kerman–Iran: Seroprevalence and correlation with clinical and laboratory findings. Research in veterinary science, 89(2), 306–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R. C. , Chabaud, A. G. , & Willmott, S. (2009). Keys to the nematode parasites of vertebrates: Archival volume. CABI. [Google Scholar]

- Arbabi, M. , & Hooshyar, H. (2009). Gastrointestinal parasites of stray cats in Kashan, Iran. Tropical Biomedicine, 26(1), 16–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arruda, I. F. , Ramos, R. C. F. , da Silva Barbosa, A. , de Souza Abboud, L. C. , Dos Reis, I. C. , Millar, P. R. , & Amendoeira, M. R. R. (2021). Intestinal parasites and risk factors in dogs and cats from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Veterinary Parasitology: Regional Studies and Reports, 24, 100552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barua, P. , Musa, S. , Ahmed, R. , & Khanum, H. (2020). Occurrence of zoonotic parasites in cats (Felis catus) at an urban pet market. Bangladesh Journal of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, 8(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Beigi, S. , Fard, S. R. N. , & Akhtardanesh, B. (2017). Prevalence of zoonotic and other intestinal protozoan parasites in stray cats (Felis domesticus) of Kerman, South‐East of Iran. İstanbul Üniversitesi Veteriner Fakültesi Dergisi, 43(1), 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Benelli, G. , Wassermann, M. , & Brattig, N. W. (2021). Insects dispersing taeniid eggs: who and how? Veterinary Parasitology, 295, 109450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borji, H. , Razmi, G. , Ahmadi, A. , Karami, H. , Yaghfoori, S. , & Abedi, V. (2011). A survey on endoparasites and ectoparasites of stray cats from Mashhad (Iran) and association with risk factors. Journal of Parasitic Diseases, 35, 202–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, D. D. (2020). The anatomy of the third‐stage larva of Toxocara canis and Toxocara cati . Advances in Parasitology, 109, 39–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brozou, A. , Fuller, B. T. , De Cupere, B. , Marrast, A. , Monchot, H. , Peters, J. , Van de Vijver, K. , Lambert, O. , Mannino, M. A. , & Ottoni, C. (2023). A dietary perspective of cat‐human interactions in two medieval harbors in Iran and Oman revealed through stable isotope analysis. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 12316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changizi, E. , Moubedi, I. , SALIMI, B. M. , & REZAEI, D. A. (2007). Gastrointestinal helminthic parasites in stray cats (Felis catus) from North of Iran. Iranian Journal of Parasitology, 2(4), 25–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'ambroso Fernandes, F. , Rojas Guerra, R. , Segabinazzi Ries, A. , Felipetto Cargnelutti, J. , Sangioni, L. A. , & Silveira Flores Vogel, F. (2022). Gastrointestinal helminths in dogs: Occurrence, risk factors, and multiple antiparasitic drug resistance. Parasitology Research, 121(9), 2579–2586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantas‐Torres, F. , & Otranto, D. (2014). Dogs, cats, parasites, and humans in Brazil: Opening the black box. Parasites & vectors, 7(1), 1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darabi, E. , Kia, E. B. , Mohebali, M. , Mobedi, I. , Zahabiun, F. , Zarei, Z. , Khodabakhsh, M. , & Khanaliha, K. (2021). Gastrointestinal helminthic parasites of stray cats (Felis catus) in Northwest Iran. Iranian Journal of Parasitology, 16(3), 418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, L. M. (2010). Keys to the nematode parasites of vertebrates: Supplementary volume (Vol. 10). CABI. [Google Scholar]

- Hajipour, N. , Imani Baran, A. , Yakhchali, M. , Banan Khojasteh, S. M. , Sheikhzade Hesari, F. , Esmaeilnejad, B. , & Arjmand, J. (2016). A survey study on gastrointestinal parasites of stray cats in Azarshahr,(East Azerbaijan province, Iran). Journal of Parasitic Diseases, 40, 1255–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostopoulou, D. , Claerebout, E. , Arvanitis, D. , Ligda, P. , Voutzourakis, N. , Casaert, S. , & Sotiraki, S. (2017). Abundance, zoonotic potential and risk factors of intestinal parasitism amongst dog and cat populations: The scenario of Crete, Greece. Parasites & vectors, 10, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciag, L. , Morgan, E. R. , & Holland, C. (2022). Toxocara: Time to let cati ‘out of the bag’. Trends in Parasitology, 38(4), 280–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaei, M. , Khovand, H. , & Akhtardanesh, B. (2016). Prevalence of ectoparasites in owned dogs in Kerman city, southeast of Iran. Journal of Parasitic Diseases, 40, 454–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, S. I. , Haroun, E. M. , Yousif, M. , Mursal, W. I. , & Abdelsalam, E. B. (2021). Prevalence and pathology of some internal parasites in stray cats (Felis catus) in Khartoum North Town, Sudan. American Journal of Research Communication, 9, 13–33. [Google Scholar]

- Morelli, S. , Diakou, A. , Di Cesare, A. , Colombo, M. , & Traversa, D. (2021). Canine and feline parasitology: Analogies, differences, and relevance for human health. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 34(4), e00266‐320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ola‐Fadunsin, S. D. , Abdulrauf, A. B. , Abdullah, D. A. , Ganiyu, I. A. , Hussain, K. , Sanda, I. M. , Rabiu, M. , & Akanbi, O. B. (2023). Epidemiological studies of gastrointestinal parasites infecting dogs in Kwara Central, North Central, Nigeria. Comparative Immunology, Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 93, 101943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overgaauw, P. A. , Vinke, C. M. , van Hagen, M. A. , & Lipman, L. J. (2020). A one health perspective on the human–companion animal relationship with emphasis on zoonotic aspects. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), 3789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, J. , Castro, A. , Novo, T. , & Maia, C. (2022). Dipylidium caninum in the twenty‐first century: Epidemiological studies and reported cases in companion animals and humans. Parasites & Vectors, 15(1), 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saba, N. , & Balwan, W. K. (2021). Potential threat of emerging and re‐emerging zoonotic diseases. Annals of the Romanian Society for Cell Biology, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sauda, F. , Malandrucco, L. , De Liberato, C. , & Perrucci, S. (2019). Gastrointestinal parasites in shelter cats of central Italy. Veterinary Parasitology: Regional Studies and Reports, 18, 100321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen, M. N. (2022). The concept of one health applied to the problem of zoonotic diseases. Reviews in Medical Virology, 32(4), e2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulsby, E. J. L. (1968). Helminths arthropods and protozoa of domesticated animals. EWP. [Google Scholar]

- Szwabe, K. , & Błaszkowska, J. (2017). Stray dogs and cats as potential sources of soil contamination with zoonotic parasites. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine, 24(1), 39–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torgerson, P. R. , & Macpherson, C. N. (2011). The socioeconomic burden of parasitic zoonoses: Global trends. Veterinary Parasitology, 182(1), 79–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaghefi, S. A. , Keykhai, M. , Jahanbakhshi, F. , Sheikholeslami, J. , Ahmadi, A. , Yang, H. , & Abbaspour, K. C. (2019). The future of extreme climate in Iran. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicente, J. J. , Rodrigues, H. O. , Gomes, D. C. , & Pinto, R. M. (1997). Nematóides do Brasil. Parte V: Nematóides de mamíferos. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia, 14, 1–452. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguti, S. (1961). Systema helminthum. Volume III. The nematodes of vertebrates. Interscience Publishers.. [Google Scholar]

- Zanzani, S. A. , Gazzonis, A. L. , Scarpa, P. , Berrilli, F. , & Manfredi, M. T. (2014). Intestinal parasites of owned dogs and cats from metropolitan and micropolitan areas: Prevalence, zoonotic risks, and pet owner awareness in northern Italy. BioMed Research International, 2014, 696508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.