Abstract

Importance

Aspirin may reduce severity of metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) and lower the incidence of end-stage liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma, in patients with MASLD. However, the effect of aspirin on MASLD is unknown.

Objective

To test whether low-dose aspirin reduces liver fat content, compared with placebo, in adults with MASLD.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This 6-month, phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial was conducted at a single hospital in Boston, Massachusetts. Participants were aged 18 to 70 years with established MASLD without cirrhosis. Enrollment occurred between August 20, 2019, and July 19, 2022, with final follow-up on February 23, 2023.

Interventions

Participants were randomized (1:1) to receive either once-daily aspirin, 81 mg (n = 40) or identical placebo pills (n = 40) for 6 months.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary end point was mean absolute change in hepatic fat content, measured by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) at 6-month follow-up. The 4 key secondary outcomes included mean percentage change in hepatic fat content by MRS, the proportion achieving at least 30% reduction in hepatic fat, and the mean absolute and relative reductions in hepatic fat content, measured by magnetic resonance imaging proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF). Analyses adjusted for the baseline value of the corresponding outcome. Minimal clinically important differences for study outcomes were not prespecified.

Results

Among 80 randomized participants (mean age, 48 years; 44 [55%] women; mean hepatic fat content, 35% [indicating moderate steatosis]), 71 (89%) completed 6-month follow-up. The mean absolute change in hepatic fat content by MRS was −6.6% with aspirin vs 3.6% with placebo (difference, −10.2% [95% CI, −27.7% to −2.6%]; P = .009). Compared with placebo, aspirin treatment significantly reduced relative hepatic fat content (−8.8 vs 30.0 percentage points; mean difference, −38.8 percentage points [95% CI, −66.7 to −10.8]; P = .007), increased the proportion of patients with 30% or greater relative reduction in hepatic fat (42.5% vs 12.5%; mean difference, 30.0% [95% CI, 11.6% to 48.4%]; P = .006), reduced absolute hepatic fat content by MRI-PDFF (−2.7% vs 0.9%; mean difference, −3.7% [95% CI, −6.1% to −1.2%]; P = .004]), and reduced relative hepatic fat content by MRI-PDFF (−11.7 vs 15.7 percentage points; mean difference, −27.3 percentage points [95% CI, −45.2 to −9.4]; P = .003). Thirteen participants (32.5%) in each group experienced an adverse event, most commonly upper respiratory tract infections (10.0% in each group) or arthralgias (5.0% for aspirin vs 7.5% for placebo). One participant randomized to aspirin (2.5%) experienced drug-related heartburn.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this preliminary randomized clinical trial of patients with MASLD, 6 months of daily low-dose aspirin significantly reduced hepatic fat quantity compared with placebo. Further study in a larger sample size is necessary to confirm these findings.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04031729

Key Points

Question

In patients with metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), does 81 mg of aspirin daily reduce the quantity of hepatic fat at 6-month follow-up compared with placebo?

Findings

In this phase 2 randomized clinical trial of 80 individuals with MASLD, daily aspirin reduced the quantity of hepatic fat at 6-month follow-up compared with placebo (mean difference, −10.2%).

Meaning

In a preliminary randomized clinical trial of adults with MASLD, 6 months of daily low-dose aspirin significantly reduced liver fat content compared with placebo, but findings are preliminary and require confirmation in a larger population.

This randomized clinical trial compares use of low-dose aspirin vs placebo in reducing hepatic fat among adult patients with metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) without cirrhosis.

Introduction

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is the most common cause of chronic liver disease in Western countries, affecting more than 30% of US adults.1 Up to one-third of patients with MASLD develop progressive steatohepatitis and fibrosis, which can lead to cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and death.2,3 Yet, approved medications that effectively and safely reverse steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis are lacking.

Aspirin may represent a promising and low-cost strategy for treating MASLD and preventing progression to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. In preclinical studies of steatohepatitis, platelets were the first cells to infiltrate the liver, promoting inflammation by activating Kupffer cells and releasing proinflammatory α-granules.4 In those models, aspirin reversed steatosis and necroinflammation, and prevented fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma through glycoprotein 1b α-mediated inhibition of platelet activation and immune cell signaling.4 Aspirin also exhibited anti-inflammatory and antitumor effects by inhibiting proinflammatory cyclooxygenase-2 and platelet-derived growth factor signaling,5,6,7,8,9 and it modulated bioactive lipids.10 Consistent with those findings, observational studies in patients with MASLD demonstrated that aspirin use was associated with lower rates of disease progression to advanced fibrosis,11 hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver-related mortality.12,13,14 Additionally, a preliminary nonrandomized study of 22 adults with steatotic liver disease reported reduced liver fat content after 6 months of antiplatelet therapy with either aspirin or combined aspirin and clopidogrel, compared with no treatment.4 However, this prior study was small, had an observational design, and could not distinguish aspirin-specific benefits from those related to P2Y12 inhibition (clopidogrel) or statins, which were initiated in all but 4 aspirin-treated patients. Consequently, the therapeutic effects of aspirin for treating MASLD remain unclear.

This phase 2 randomized clinical trial tested the effects of low-dose aspirin (81 mg/day) for reducing hepatic fat at 6-month follow-up, compared with placebo, in adults with MASLD.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, single-center clinical trial recruited adults with MASLD without cirrhosis between August 20, 2019, and July 19, 2022. The protocol was approved by the Mass General Brigham institutional review board; all participants provided written informed consent. The protocol and statistical analysis plan are included in Supplement 1. Final follow-up occurred on February 23, 2023.

Eligibility and Exclusion Criteria

Eligible participants were aged 18 to 70 years with steatotic liver disease documented either by liver histology or an appropriate imaging modality confirming steatosis (ie, >5% hepatic fat content).15 We excluded individuals with significant alcohol use (≥3 drinks/day in men; ≥2 drinks/day in women), with alternative causes of liver disease (diagnosis of viral hepatitis B or hepatitis C infection [by serologies], hemochromatosis, α-1 antitrypsin deficiency, Wilson disease, autoimmune hepatitis, or HIV [by medical record review or self-report]), or with any evidence of cirrhosis or liver decompensation (by medical record review and confirmation from the treating clinician). We excluded individuals who used aspirin-containing medications within the prior 3 months; currently used another antiplatelet, antithrombotic, or anticoagulant medication; had thrombocytopenia, bariatric surgery within the prior 2 years, or active malignancy (except nonmelanoma skin cancer); were currently pregnant or breastfeeding; or with any contraindication to aspirin or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Randomization and Masking

Eligible participants were randomized (1:1 using a computer-generated randomization schedule in permuted blocks of 2 and 8) to receive aspirin 81 mg or identical placebo pill once daily for 6 months. Participants, investigators, and study personnel were unaware of treatment assignment and remained masked to postbaseline assessments until all patients had completed follow-up testing.

Procedures

Study drug was administered orally once daily for 6 months after the baseline/randomization visit. Visits were conducted fasting, and participants received standard nutritional counseling for MASLD at screening. To meet requirements of the US National Institutes of Health, race and ethnicity data were collected from participants by self-report, using fixed categories. The baseline visit included MRI assessments of hepatic fat fraction and markers of intrahepatic inflammation and fibrosis,16,17,18 anthropometrics, laboratory testing (hematology, chemistries), standardized bionutrition and physical activity assessments, and liver stiffness measurements of fibrosis by vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE), using established cut points.19 Assessments were repeated at 6 months. Hematocrit level was assessed after 3 months. Participants with a decrease in hematocrit of greater than 20% compared baseline were asked to discontinue use of the study drug. Safety, tolerability, and adherence were evaluated by self-report at all visits, and adherence was assessed with returned pill count at month 6. Laboratory analyses were conducted using standard methods and performed at Quest Laboratories.

Primary Outcome

The primary end point was mean absolute change from baseline to month 6 in hepatic fat fraction, measured by single voxel breath-hold 1H-MR spectroscopy (MRS).16,17,18 Hepatic fat fraction was calculated as the area under the spectroscopic lipid peak divided by the total area under the water and lipid peaks, with higher values indicating more severe steatosis (range, 0%-100%: grade 0 [healthy, <5%]; grade 1 [mild, 5%-33%], grade 2 [moderate, 34%-66%], and grade 3 [severe, >66%]). MRS is well-validated for quantifying liver fat, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.94 (95% CI, 0.88 to 1.0).17 Although a minimal clinically important difference for change in hepatic fat fraction by MRS was not prespecified, prior studies support an absolute reduction of greater than 1% as meaningful, given corresponding biological responses (ie, changes in liver enzymes and body weight),20,21,22 changes in histological steatosis severity, and markers of hepatic apoptosis and necroinflammation.23

Secondary Outcomes

Four prespecified, key secondary end points consisted of the 6-month relative (percentage) change in hepatic fat fraction by MRS, attainment of at least a 30–percentage point relative reduction in hepatic fat, and both absolute and relative changes in liver fat content by MRI proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF).20,21,24 MRI-PDFF is well-validated for quantifying hepatic fat (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, 0.95 [95% CI, 0.91 to 1.0)25 and for detecting small but meaningful changes in hepatic fat content.20,21,22,23 While no MCID was prespecified, prior studies support a relative reduction in hepatic fat of 30% or greater as clinically meaningful because that degree of change was associated with histological improvements in steatohepatitis20,21,22,23 and fibrosis.26

Prespecified nonkey secondary end points consisted of 6-month absolute changes in alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), iron-corrected T1 score, a validated composite MRI estimate of hepatic inflammation and fibrosis,18,27,28,29 VCTE-estimated liver fibrosis, body weight, and body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared). No MCID was prespecified for nonkey secondary outcomes.

Post Hoc Exploratory Outcomes

Post hoc exploratory outcomes included attainment of (a) ALT reduction of 17 IU/L or greater, (b) both ALT reduction of 17 IU/L or greater and 30 percentage point or greater reduction in hepatic fat fraction, and (c) a 50–percentage point or greater reduction in hepatic fat fraction.

Adverse Events

Safety end points included laboratory tests at month 3 and month 6 (hematocrit) and adverse events, assessed as open-ended questions at all visits.

Sample Size

We calculated that a sample size of 80 participants would provide effective power of greater than 90% to demonstrate superiority of aspirin 81 mg per day vs placebo for the primary end point (6-month absolute change in hepatic fat fraction), with a 2-sided P value of less than .05, assuming more than a 3% difference in mean absolute hepatic fat fraction change between the 2 groups, a standard deviation of 2.5%, and a drop-out rate of 15% (ie, yielding an effective sample of 68 participants).30,31

Statistical Analysis

Continuous end points were assessed by analysis of covariance, with treatment group at randomization included as a fixed effect and baseline value included as a covariate. Logistic regression was used for binary end points. The primary analysis set included all of the 80 randomized participants, analyzed according to assigned treatment group, and assumed missing outcomes data were missing at random32; data for missing outcomes were imputed via multiple imputation with 20 imputations, based on same treatment group, with the outcome variable and its corresponding baseline value, age, sex, race and ethnicity, type 2 diabetes, previous liver biopsy, and body weight (except for analyses of weight) as covariates. Each imputed data set was analyzed separately, with estimates combined using the Rubin formula.

Per-Protocol Analyses

Prespecified per-protocol analyses evaluated study end points among all 71 randomized participants with complete outcomes assessments, using similar analysis of covariance and logistic-regression procedures.

For analyses of the primary end point, nonkey secondary end points, and post hoc exploratory end points, 2-sided P value of less than .05 denoted statistical significance. For the 4 key secondary end points, the sequentially rejective Holm procedure accounted for multiple testing,33 with a threshold P value of .0125 for relative change in hepatic fat by MRS, a P value of .0167 for proportion achieving at least 30% hepatic fat reduction, and P values of .025 for absolute change and .05 for relative change in hepatic fat by MRI-PDFF. For the nonkey secondary and exploratory end points, no multiplicity adjustments were applied. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, findings for nonkey secondary and post hoc end points should be interpreted as exploratory.

Prespecified sensitivity analyses for the primary and key secondary end points included the following: (a) treating missing end point data as nonresponses by carrying forward baseline values; (b) constructing multivariable-adjusted regression models accounting for potential confounders (ie, age, sex, race and ethnicity, type 2 diabetes, body weight and visceral adipose tissue volume)34; and (c) repeating analyses after excluding participants who lost 3% or more of body weight during the trial to address potential confounding from weight loss.

In planned subgroup analyses, the outcomes of absolute and relative change in hepatic fat content by MRS were assessed among participants with significant, stage 2 or greater fibrosis (by VCTE).19

Post Hoc Analyses

Post hoc subgroup analyses were conducted among participants with more than 20% hepatic fat at baseline and separately after excluding any participant with a weight gain of more than 15 kg during the trial.

Analyses were conducted using SAS version 16 (SAS Institute) and JMP version 17.1 (SAS Institute); Stata Version 17 SE (StataCorp) was used for figures.

Results

Participants

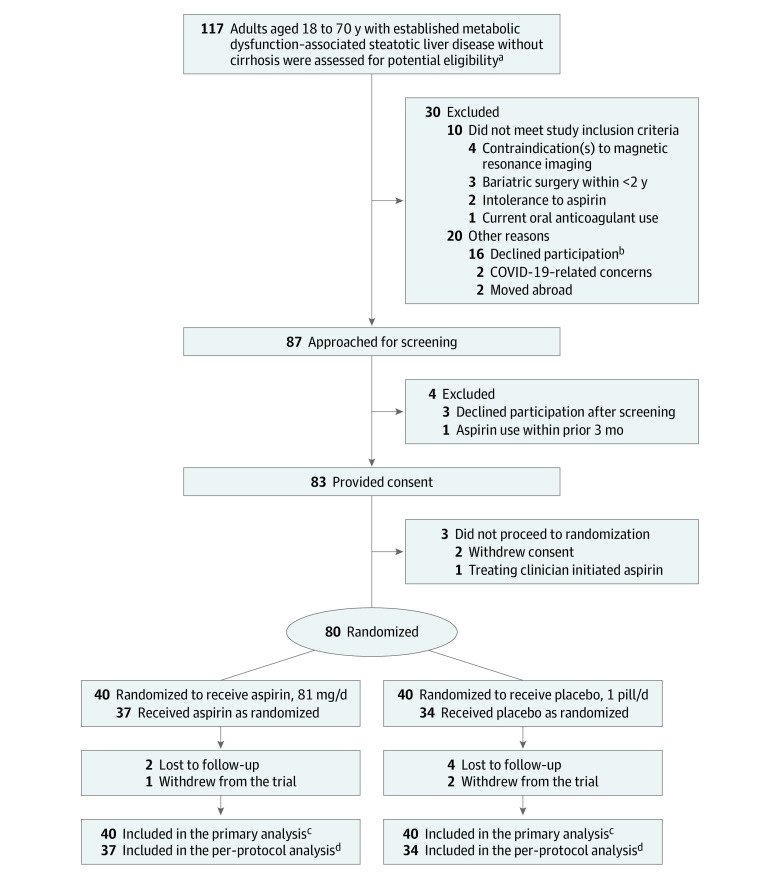

Between August 2019 and July 2022, there were 87 individuals who underwent screening, and 80 participants were randomized to receive aspirin (n = 40) or placebo (n = 40) (Figure 1). Among randomized participants (Table 1), the mean age at baseline was 48.0 years, and 44 (55.0%) were female; overall mean body mass index was 33.7, and mean (SD) hepatic fat fraction by MRS was 35.2% (25.6%), with similar proportions in each group. Of the 80 randomized participants, 9 ([11.25%]; 3 in the aspirin group and 6 in the placebo group) did not complete 6-month follow-up; the remaining 71 participants (89%) who completed 6-month follow-up for study outcomes comprised the per-protocol population (37 in the aspirin group and 34 in the placebo group; Figure 1, eTable 1 in Supplement 2). Adherence rates, measured by returned pill counts at month 6, were greater than 90% for 94.5% [35] in the aspirin group and 88.2% [30] in the placebo group (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). Characteristics of the 71 participants who completed 6-month follow-up and the 9 who did not complete 6-month follow-up are in eTable 3 in Supplement 2.

Figure 1. Participant Screening, Randomization, and Treatment.

aPrescreening for potential eligibility was conducted by the investigator team (see study protocol in Supplement 1).

bCommon reasons for which patients declined to participate included lack of time or childcare concerns. For additional details regarding reasons for early trial discontinuation, see Results section and eTable 1 in Supplement 2.

cThe full analysis set included all 80 randomized participants.

dThe per-protocol analysis set included all 71 randomized participants who provided consent, were randomized, and who completed the 6-month visit assessments for study outcomes. There were no missing data in this set.

MASLD indicates metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of All Randomized Participants (N = 80).

| Characteristica | Aspirin (n = 40) | Placebo (n = 40) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 46.6 (12.1) | 49.3 (12.1) |

| Female sex | 21 (52.5) | 23 (57.5) |

| Male sex | 19 (47.5) | 17 (42.5) |

| Race | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (2.5) | 0 |

| Asian | 2 (5) | 1 (2.5) |

| Black or African American, non-Hispanic | 1 (2.5) | 0 |

| White, non-Hispanic | 30 (75.0) | 33 (82.5) |

| Hispanic or Latino ethnicity | 6 (15.0) | 6 (15.0) |

| Anthropometrics, mean (SD) | ||

| Weight, kg | 98.9 (21.1) | 93.8 (21.0) |

| Body mass indexb | 34.0 (5.8) | 33.4 (6.2) |

| Visceral adipose tissue volume, cm3 | 204.5 (87.4) | 180.0 (74.3) |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Type 2 diabetes | 16 (40.0) | 15 (37.5) |

| Hypertension | 15 (37.5) | 14 (35.0) |

| Prescription medication usec | 14 (35.0) | 15 (37.5) |

| Metformin | 6 (15.0) | 7 (17.5) |

| Statin | 5 (12.5) | 6 (15.0) |

| Vitamin E | 3 (7.5) | 4 (10.0) |

| Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist | 3 (7.5) | 3 (7.5) |

| Laboratory values, mean (SD) | ||

| Alanine aminotransferase, IU/L | 53.1 (30.4) | 51.1 (32.1) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, IU/L | 40.5 (16.5) | 39.8 (20.2) |

| Hemoglobin A1c, % | 5.7 (1.0) | 5.7 (1.4) |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, mg/dL | 114.8 (26.2) | 110.9 (32.3) |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, mg/dL | 44.0 (10.8) | 45.2 (9.3) |

| Hepatic assessments, mean (SD) | ||

| Hepatic fat fraction by MRI spectroscopy, % | 39.1 (26.1) | 31.4 (24.8) |

| Hepatic fat by MRI proton density fat fraction, % | 16.7 (9.2) | 14.7 (8.6) |

| Liver stiffness by VCTE, kPA | 6.9 (5.9) | 6.6 (3.6) |

| Significant (stage ≥2) fibrosis, by VCTEd | 15 (37.5) | 17 (42.5) |

| Eligible prior clinical liver biopsye | 23 (57.5) | 21 (52.5) |

| Steatohepatitis, % of total with biopsy | 19 (82.6) | 18 (85.7) |

| Fibrosis (stage 1-3), % of total with biopsy | 16 (69.6) | 15 (71.4) |

| Stage 0 | 7 (30.4) | 6 (28.6) |

| Stage 1 | 8 (34.8) | 7 (33.3) |

| Stage 2 | 7 (30.4) | 7 (33.3) |

| Stage 3 | 1 (4.3) | 1 (4.8) |

Abbreviations: MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; VCTE, vibration-controlled transient elastography.

SI conversion factors: To convert alanine aminotransferase or aspartate aminotransferase to μkat/L, multiply by 0.0167; high-density lipoprotein cholesterol or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0259.

There were no statistically significant differences between groups at baseline for any of the variables shown. Data presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated. No data were missing.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Although not mandated by the study protocol, all randomized participants with baseline prescription medication use had been taking stable (unchanged) dosages of the listed prescriptions (ie, metformin, statin, vitamin E, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists) for at least 6 months prior to enrollment. No participant had a dosage change of these medications during the treatment period.

Significant, fibrosis of stage 2 or greater was estimated by VCTE, using the established cut point of 8.6 kPA (see Methods).

Eligible prior clinical biopsies occurred within less than 12 months of the screening date (see Methods and study protocol).

Primary Outcome

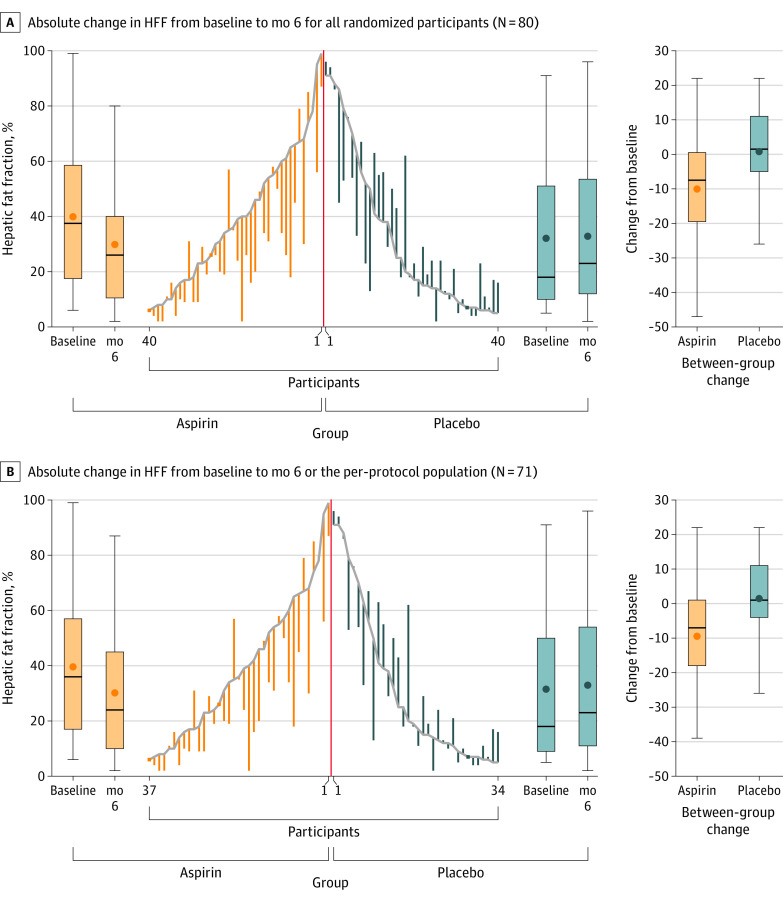

Among all 80 randomized participants, aspirin significantly reduced absolute hepatic fat fraction (−6.6% [95% CI, −11.9% to −1.3%]) compared with placebo (3.6% [95% CI, −1.7% to 8.9%]), with a mean difference of −10.2% (95% CI, −27.7% to −2.6%; P = .009) (Table 2, Figure 2A).

Table 2. Effect of Daily Aspirin 81 mg Compared With Placebo on Hepatic Fat and Markers of Inflammation and Fibrosis Among All Randomized Participants (N = 80)a.

| End points | Aspirin 81 mg (n = 40) | Placebo (n = 40) | Mean difference, aspirin vs placebo (95% CI)b | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Month 6 | Mean change (95% CI)b | Baseline | Month 6 | Mean change (95% CI)b | |||

| Primary end pointc | ||||||||

| Absolute change in hepatic fat % by MRS, mean (SD) | 39.1 (26.1) | 32.0 (26.9) | −6.6 (−11.9 to −1.3) | 31.2 (24.7) | 35.4 (26.9) | 3.6 (−1.7 to 8.9) | −10.2 (−27.7 to −2.6) | .009 |

| Key secondary end pointsd | ||||||||

| Relative change in hepatic fat % by MRS, percentage points | −8.8 (−28.3 to 10.8) | 30.0 (10.4 to 49.6) | −38.8 (−66.7 to −10.8) | .007 | ||||

| Relative reduction in hepatic fat ≥30% by MRS, No. (%) | 17 (42.5) | 17 (42.5) | 5 (12.5) | 5 (12.5) | 30.0 (11.6 to 48.4) | .006 | ||

| Absolute change in hepatic fat % by MRI-PDFF, mean (SD) | 16.7 (9.2) | 13.8 (9.0) | −2.7 (−4.5 to −1.0) | 14.7 (8.6) | 15.8 (8.9) | 0.9 (−0.8 to 2.6) | −3.7 (−6.1 to −1.2) | .004 |

| Relative change in hepatic fat % by MRI-PDFF, percentage points | −11.7 (−24.3 to 1.0) | 15.7 (3.0 to 28.3) | −27.3 (−45.2 to −9.4) | .003 | ||||

| Other secondary end points, change between baseline and mo 6e | ||||||||

| Iron-corrected T1 score, mean (SD), msf | 898.8 (118.3) | 876.0 (131.3) | −19.2 (−42.1 to 3.8) | 833.5 (130.0) | 845.6 (127.3) | 15.7 (−7.3 to 38.7) | −34.9 (−67.3 to −2.4) | <.001 |

| ALT, mean (SD), IU/L | 53.1 (30.4) | 37.2 (24.5) | −16.1 (−21.1 to −11.0) | 51.2 (32.1) | 50.4 (34.5) | −0.5 (−5.6 to 4.5) | −15.6 (−22.7 to −8.4) | <.001 |

| AST, mean (SD), IU/L | 40.5 (16.5) | 26.0 (10.9) | −14.6 (−17.8 to −11.3) | 39.8 (20.2) | 39.6 (17.5) | −0.2 (−3.5 to 3.0) | −14.3 (−19.0 to −9.7) | <.001 |

| Liver stiffness by VCTE, mean (SD), kPAg | 7.1 (5.8) | 6.0 (3.0) | −1.1 (−2.0 to −0.2) | 6.9 (3.6) | 8.7 (4.4) | 1.7 (0.8 to 2.6) | −2.8 (−4.0 to −1.5) | <.001 |

| Body weight, mean (SD), kg | 98.9 (21.1) | 98.9 (21.6) | 0.5 (−0.6 to 1.6) | 93.8 (21.0) | 94.5 (21.9) | 0.7 (−0.4 to 1.7) | −0.2 (−1.7 to 1.4) | .82 |

| Weight loss ≥3%, No. (%) | 5 (12.5) | 5 (12.5) | 4 (10.0) | 4 (10.0) | 2.5 (−11.3 to 16.3) | .74 | ||

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MRS, magnetic resonance spectroscopy; PDFF, proton-density fat fraction; VCTE, vibration-controlled transient elastography.

SI conversion factors: To convert ALT or AST to μkat/L, multiply by 0.0167.

Analyses were conducted using analysis of covariance for continuous outcomes, and using logistic regression for binary outcomes, between baseline and month 6; models included treatment group at randomization as a fixed effect and the baseline value of the relevant outcome as a covariate. Continuous variables were analyzed using log-transformation, as appropriate. For the prespecified primary analysis in all 80 randomized participants, multiple imputation was used for missing end point data (see Methods).

Mean changes are from baseline to month 6; analyses report least-squares means with corresponding 95% CIs, unless specified otherwise.

The primary end point was tested under type I error control, and comparison with placebo was significant at a 2-tailed P value of less than .05.

For the 4 key secondary end points, the Results were statistically significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons using the Holm procedure, with threshold P = .0125 for relative change in hepatic fat by MRS, P = .0167 for achievement of at least 30% relative reduction in hepatic fat, P = .025 for absolute change in hepatic fat by MRI-PDFF, and P = .05 for relative change in hepatic fat by MRI-PDFF.

For the other nonkey secondary end points, adjustments were not made for multiplicity testing. Presented data for the nonkey secondary end points represent absolute changes between baseline and month 6 unless specified otherwise. For details, see Methods and study protocol.

The iron-corrected T1 score is a validated multiparametric MRI measure of the composite of hepatic inflammation and fibrosis. It was calculated from noncontrast T1 mapping of extracellular fluid while accounting for hepatic iron content by T2 mapping using an established correction algorithm (higher scores indicate more hepatic inflammation and/or fibrosis). While population ranges are not yet well-established, in prior studies, median iron-corrected T1 scores were 687 milliseconds (IQR, 619-755) in healthy control participants vs 814 milliseconds (IQR, 680-948) in participants with MASLD. Scores greater than 800 milliseconds could help ascertain steatohepatitis (for additional details, see Methods).

VCTE score range, 1 to 75 kPA, with higher values indicating increased stiffness, which correlates with fibrosis. Validated cut points were used to translate liver stiffness measurements into estimated fibrosis severity (ie, liver stiffness >8.6 kPA indicates fibrosis stage ≥2) (for additional details, see Methods).

Figure 2. Effect of Daily Aspirin 81 mg Compared With Placebo on Hepatic Fat Fraction.

Data in the center of each panel present individual participant changes in the absolute hepatic fat fraction (HFF) by magnetic resonance spectroscopy and by treatment group. Box plots indicate the median (thick horizontal line), mean (circle), IQR (box top and bottom), and maximum and minimum changes in HFF (whiskers). The orange box plots on the left side in each panel show within-group changes in the aspirin group; the blue box plots on the right side in each panel show within-group changes in the placebo group; the orange and blue box plots at the far right show between-group absolute changes between baseline and month 6.

Key Secondary Outcomes

Aspirin significantly reduced relative hepatic fat fraction (−8.8 percentage points [95% CI, −28.3 to 10.8]) compared with placebo (30.0 percentage points [95% CI, 10.4 to 49.6]; a mean difference, −38.8 percentage points [95% CI, −66.7 to −10.8]; P = .007) (Table 2). Rates of achieving 30–percentage point reductions or greater in hepatic fat were 42.5% with aspirin vs 12.5% with placebo (mean difference, 30.0% [95% CI, 11.6% to 48.4%]; P = .006). When liver fat was quantified by MRI-PDFF, the mean absolute change in liver fat content was −2.7% (95% CI, −4.5% to −1.0%) with aspirin vs 0.9% (95% CI, −0.8% to 2.6%) with placebo (mean difference, −3.7% [95% CI, −6.1% to −1.2%]; P = .004), and the mean relative change in liver fat content was −11.7 percentage points (95% CI, −24.3 to 1.0) with aspirin vs 15.7 percentage points (95% CI, 3.0 to 28.3) with placebo (mean difference, −27.3 percentage points [95% CI, −45.2 to −9.4]; P = .003) (Table 2).

Other Secondary Outcomes

Aspirin significantly reduced levels of ALT (−16.1 IU/L [95% CI, −21.1 to −11.0] with aspirin vs −0.5 IU/L [95% CI, −5.6 to 4.5] with placebo; mean absolute difference, −15.6 IU/L [95% CI, −22.7 to −8.4]; P < .001), AST (−14.6 IU/L [95% CI, −17.8 to −11.3] with aspirin vs −0.2 IU/L [95% CI, −3.5 to 3.0] with placebo; difference, −14.3 IU/L [95% CI, −19.0 to −9.7]; P < .001), corrected T1-estimated inflammation and fibrosis (−19.2 milliseconds [95% CI, −42.1 to 3.8] with aspirin vs 15.7 milliseconds [95% CI, −7.3 to 38.7] with placebo; difference, −34.9 milliseconds [95% CI, −67.3 to −2.4]; P < .001), and fibrosis estimated by VCTE (−1.1 kPA [95% CI, −2.0 to −0.2] with aspirin vs 1.7 kPA [95% CI, 0.8 to 2.6] with placebo; difference, −2.8 kPA [95% CI, −4.0 to −1.5]; P < .001) (Table 2). There were no significant differences between groups in mean absolute weight change (0.5 kg [95% CI, −0.6 to 1.6] with aspirin vs 0.7 kg [95% CI, −0.4 to ] with placebo; difference, −0.2 kg [95% CI, −1.7 to 1.4]; P = .82) or in the proportions who lost 3% or more of body weight during the trial (12.5% [5 participants] with aspirin vs 10.0% [4 participants] with placebo; difference, 2.5% [95% CI, −11.3% to 16.3%]; P = .74) (Table 2).

Per-Protocol Analyses

Within the per-protocol population (n = 71), aspirin significantly reduced absolute hepatic fat fraction (−5.9% [95% CI, −11.6% to −0.2%] compared with placebo (4.7% [95% CI, −1.2% to 10.7%]; mean difference, −10.6% [95% CI, −19.0% to −2.2%]; P = .01) (eTable 4 in Supplement 2). Results for all key and nonkey secondary outcomes in the per-protocol population were similar in both magnitude and significance to those from the full randomized population (eTable 4 in Supplement 2).

Sensitivity Analyses

Prespecified sensitivity analyses of the primary and key secondary outcomes yielded similar results. First, when baseline values were carried forward for missing outcomes data, the absolute treatment effect with aspirin remained statistically significant (−5.4% [95% CI, −10.6% to −0.2%] with aspirin vs 4.0% [95% CI, −1.2% to 9.2%] with placebo; mean difference, −9.4% [95% CI, −16.8% to −1.9%]; P = .01) (eTable 5 in Supplement 2). Second, prespecified models adjusting for age, sex, race and ethnicity, type 2 diabetes, body weight, and visceral adipose tissue volume yielded similar, statistically significant absolute treatment effects with aspirin in the full population (−8.7% [95% CI, −15.8% to −1.6%] with aspirin vs 2.4% [95% CI, −4.4% to 9.2%] with placebo; mean difference, −11.1% [95% CI, −19.4% to −2.8%]; P = .009) (eTable 6 in Supplement 2) and in the per-protocol set (−7.2% [95% CI, −15.1% to 0.7%] with aspirin vs 3.9% [95% CI, −3.9% to 11.8%] with placebo; mean difference, −11.1% [95% CI, −20.4% to −1.9%]; P = .02) (eTable 7 in Supplement 2). Third, aspirin significantly reduced absolute hepatic fat fraction, compared with placebo, among participants in the full randomized population without 3% body weight loss or greater during the trial (n = 71; −7.1% [95% CI, −13.0% to −1.2%] with aspirin vs 5.0% [95% CI, −0.9% to 10.8%] with placebo; mean difference, −12.1% [95% CI, −20.7% to −3.5%]; P = .006) (eTable 8 in Supplement 2) and among participants in the per-protocol set without 3% body weight loss or greater (n = 64; −6.2% [95% CI, −12.6% to 0.1%] with aspirin vs 5.9% [95% CI, −0.6% to 12.4%] with placebo; mean difference, −12.1% [95% CI, −21.5% to −2.8%]; P = .01) (eTable 9 in Supplement 2).

Subgroup Analyses

Thirty-two participants (15 in the aspirin group and 17 in the placebo group) had significant stage 2 or greater fibrosis at baseline. Within this prespecified subgroup, aspirin significantly reduced absolute hepatic fat fraction compared with placebo (−11.7% with aspirin vs 1.9% with placebo; mean difference, −13.7% [95% CI, −26.4% to −1.0%]; P = .03). Aspirin significantly reduced relative hepatic fat compared with placebo (−23.3 vs 33.0 percentage points; mean difference, −56.3 percentage points [95% CI, −104.0 to −8.6]; P = .02).

Post Hoc Exploratory Outcomes and Analyses

Within the per-protocol population (n = 71), significantly more participants in the aspirin group achieved ALT reduction of 17 IU/L or greater than in the placebo group (32.4% vs 8.8%; difference, 23.6% [95% CI, 5.8% to 41.4%]; P = .02), ALT reduction of 17 IU/L or greater and hepatic fat reduction of 30 percentage points or greater (20.6% in the aspirin group vs 2.9% in the placebo group; difference, 17.7% [95% CI, 3.5% to 31.9%]; P = .04), and hepatic fat reduction of 50 percentage points or greater (24.3% in the aspirin group vs 5.9% in the placebo group; difference, 18.4% [95% CI, 2.5% to 34.3%]; P = .05).

eTable 10 in Supplement 2 compares baseline characteristics by group among participants with baseline hepatic fat levels greater than 20%. Within this subgroup, aspirin significantly reduced absolute hepatic fat fraction (−9.8% [95% CI, −17.2% to −2.4%]) compared with placebo (3.4% [95% CI, −5.0% to 11.7%]; mean difference, −13.1% [95% CI, −24.4% to −1.9%]; P = .02), and results for the key secondary end points were similar in both direction and magnitude (eTable 11 in Supplement 2). After excluding 1 participant from the placebo group who experienced more than a 15-kg weight gain during the trial period, absolute liver fat content was significantly reduced with aspirin (−6.7% [95% CI, −12.0% to −1.4%]) compared with placebo (3.4% [95% CI, −2.0% to 8.8%]; mean difference, −10.1% [95% CI, −17.7% to −2.4%]; P = .01), and results for the key secondary outcomes also remained similar (eTable 12 in Supplement 2).

Adverse Events

Mean (SE) 6-month percentage changes in hematocrit level in the aspirin group were 0.3% (3.2%) vs −0.9% (0.8%) in the placebo group (eTable 13 in Supplement 2). No participant developed anemia, thrombocytopenia, or experienced bleeding. eTable 14 in Supplement 2 outlines adverse events. Thirteen participants (32.5%) in each group experienced an adverse event, most commonly upper respiratory tract infections (4 [10.0%] in each group) or arthralgias (2 [5.0%] in the aspirin group vs 3 [7.5%] in the placebo group). One participant randomized to aspirin experienced drug-related heartburn (2.5%). No adverse event met protocol-defined criteria for investigator discontinuation.

Discussion

In this preliminary randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of adults with MASLD, 6 months of daily low-dose aspirin (81 mg) significantly reduced mean absolute liver fat by 10.3% compared with placebo. Aspirin also produced greater reductions in the prespecified, key secondary outcomes of percentage point change in liver fat, the absolute and percentage point changes in liver fat by MRI-PDFF, and the proportion attaining a 30–percentage point or greater reduction in liver fat content.

MRI is well-established as an accepted measure for quantifying hepatic fat.16,17,18,20,21,22,24 Reducing hepatic fat by 30 percentage points or more has been defined as a meaningful treatment effect in early-phase MASLD trials, based on substantial corresponding histological improvements in steatohepatitis20,21,22 and fibrosis.26 However, beyond improving steatosis, the US Food and Drug Administration has identified that reducing steatohepatitis and preventing fibrosis progression are important histological end points for defining therapeutic efficacy in late-phase MASLD trials.35 Previous epidemiologic studies reported that both the severity and progression of MASLD histological features (ie, steatosis, steatohepatitis, and fibrosis) were associated with major adverse clinical outcomes, including cirrhosis, liver decompensation, and death.3,36,37 Thus, future clinical trials that confirm these findings should include histological and clinical outcomes. Future studies will also need to define the optimal aspirin dose, timing of initiation, and the durability of benefit.

Low-dose aspirin was safe and well-tolerated. There were no drug-related serious adverse events or bleeding events. However, treatment duration was short, and studies from the general population reported a bleeding risk of approximately 1.7 events/1000 person-years (95% CI, 0.65 to 3.10) associated with low-dose aspirin.38 Aspirin has known benefit for secondary risk reduction in established cardiovascular disease; however, for patients without cardiovascular disease, benefits of aspirin for primary prevention are unclear. Thus, for patients with MASLD who would not otherwise meet criteria for routine aspirin use, future studies are needed to define its risk-benefit profile.

For the placebo group, the present study found a modest increase in absolute hepatic fat fraction, consistent with some recent early-phase MASLD clinical trials that included participants with early-stage disease.39,40,41 Other previous trials that reported small, placebo group reductions in absolute liver fat by MRS (ie, pooled mean change of −1.5% with placebo) often included participants with more advanced steatohepatitis and/or fibrosis, and placebo responses correlated with clinical factors, including changes in body weight or body mass index.42 Consistent with those observations, in the present study, the response in the placebo group was more attenuated in the subgroup with stage 2 fibrosis or greater after multivariable adjustment and after excluding 1 person from the placebo group with a weight gain of more than 15 kg and increased liver fat during the trial. In each of those analyses, the treatment effects with aspirin remained similar. Nevertheless, future large and multicenter studies are needed to validate these findings.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size was small and follow-up was relatively short. Second, this clinical trial was conducted in a single center, which could limit generalizability. Third, this study had statistical power to detect changes in steatosis, and did not comprehensively collect liver histology at baseline and follow-up. Fourth, this trial focused on surrogate hepatic outcomes (ie, liver fat) and did not ascertain clinical end points including progression to cirrhosis or death. Fifth, modest differences in baseline characteristics between the 2 study groups, including hepatic fat, may have introduced confounding and favored the aspirin intervention. Sixth, the primary analysis applied multiple imputation to 9 participants with missing outcomes data, assuming missing data were missing at random, which may have introduced bias, and the missing at random assumption could not be tested within the data set.

Conclusions

In a preliminary randomized clinical trial of patients with MASLD, 6 months of daily low-dose aspirin significantly reduced hepatic fat quantity compared with placebo. Further study in a larger sample size is necessary to confirm these findings.

Original Study Protocol, Statistical Analysis Plan, and Summary of Changes to Protocol

eTable 1. Reasons for Premature End of Treatment

eTable 2. Adherence by Assigned Treatment Group

eTable 3. Baseline Characteristics of Randomized Participants with Complete Month 6 Outcome Data (N=71) and Missing Outcome Data (N=9)

eTable 4. Effect of Daily Aspirin 81 mg as Compared With Placebo on Hepatic Fat and Markers of Inflammation and Fibrosis in the Per-Protocol Population (N=71)

eTable 5. Effect of Daily Aspirin 81 mg as Compared With Placebo on the Primary and Key Secondary End Points Among All Randomized Participants, With Missing Data Imputed as Nonresponses

eTable 6. Effect of Daily Aspirin 81 mg as Compared With Placebo on the Primary and Key Secondary End Points Among All Randomized Participants After Multivariable Adjustment for Prespecified Confounders

eTable 7. Effect of Daily Aspirin 81 mg as Compared With Placebo on the Primary and Key Secondary End Points in the Per-Protocol Population After Multivariable Adjustment for Prespecified Confounders

eTable 8. Effect of Daily Aspirin 81 mg as Compared With Placebo on the Primary and Key Secondary End Points in the Full Randomized Population After Excluding Participants with ≥3% Weight Loss

eTable 9. Effect of Daily Aspirin 81 mg as Compared With Placebo on the Primary and Key Secondary End Points in the Per-Protocol Population After Excluding Participants With ≥3% Weight Loss

eTable 10. Baseline Characteristics of the Post Hoc Subgroup of Randomized Participants With Baseline Hepatic Fat Fraction >20% (N=52)

eTable 11. Post Hoc Subgroup Analysis of the Effect of Daily Aspirin 81 mg as Compared With Placebo on the Primary and Key Secondary End Points Among Participants With Baseline Hepatic Fat Fraction >20%

eTable 12. Post Hoc Analysis of the Effect of Daily Aspirin 81 mg as Compared With Placebo on the Primary and Key Secondary End Points After Excluding 1 Participant From the Placebo Group With >15 kg of Weight Gain During the Treatment Period

eTable 13. Safety Laboratory Measures

eTable 14. Adverse Events

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Riazi K, Azhari H, Charette JH, et al. The prevalence and incidence of NAFLD worldwide. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7(9):851-861. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00165-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vernon G, Baranova A, Younossi ZM. Systematic review: the epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(3):274-285. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04724.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simon TG, Roelstraete B, Khalili H, Hagström H, Ludvigsson JF. Mortality in biopsy-confirmed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut. 2020;70(7):1375-1382. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malehmir M, Pfister D, Gallage S, et al. Platelet GPIbα is a mediator and potential interventional target for NASH and subsequent liver cancer. Nat Med. 2019;25(4):641-655. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0379-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paik YH, Kim JK, Lee JI, et al. Celecoxib induces hepatic stellate cell apoptosis through inhibition of Akt activation and suppresses hepatic fibrosis in rats. Gut. 2009;58(11):1517-1527. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.157420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamamoto H, Kondo M, Nakamori S, et al. JTE-522, a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, is an effective chemopreventive agent against rat experimental liver fibrosis1. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(2):556-571. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(03)00904-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen H, Cai W, Chu ESH, et al. Hepatic cyclooxygenase-2 overexpression induced spontaneous hepatocellular carcinoma formation in mice. Oncogene. 2017;36(31):4415-4426. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kern MA, Schubert D, Sahi D, et al. Proapoptotic and antiproliferative potential of selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in human liver tumor cells. Hepatology. 2002;36(4 Pt 1):885-894. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshida S, Ikenaga N, Liu SB, et al. Extrahepatic platelet-derived growth factor-β, delivered by platelets, promotes activation of hepatic stellate cells and biliary fibrosis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(6):1378-1392. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.08.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilligan MM, Gartung A, Sulciner ML, et al. Aspirin-triggered proresolving mediators stimulate resolution in cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(13):6292-6297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1804000116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simon TG, Henson J, Osganian S, et al. Daily aspirin use associated with reduced risk for fibrosis progression in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(13):2776-2784.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.04.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simon TG, Duberg AS, Aleman S, Chung RT, Chan AT, Ludvigsson JF. Association of aspirin with hepatocellular carcinoma and liver-related mortality. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(11):1018-1028. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1912035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Memel ZN, Arvind A, Moninuola O, et al. Aspirin use is associated with a reduced incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Commun. 2020;5(1):133-143. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simon TG, Ludvigsson JF. Association between aspirin and hepatocellular carcinoma—reply. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(25):2481-2482. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):328-357. doi: 10.1002/hep.29367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bredella MA, Ghomi RH, Thomas BJ, et al. Breath-hold 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy for intrahepatic lipid quantification at 3 Tesla. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2010;34(3):372-376. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e3181cefb89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Georgoff P, Thomasson D, Louie A, et al. Hydrogen-1 MR spectroscopy for measurement and diagnosis of hepatic steatosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(1):2-7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bachtiar V, Kelly MD, Wilman HR, et al. Repeatability and reproducibility of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging of the liver. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0214921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siddiqui MS, Vuppalanchi R, Van Natta ML, et al. Vibration-controlled transient elastography to assess fibrosis and steatosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(1):156-163.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.04.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stine JG, Munaganuru N, Barnard A, et al. Change in MRI-PDFF and histologic response in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(11):2274-2283.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.08.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loomba R, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Sanyal A, et al. Multicenter validation of association between decline in MRI-PDFF and histologic response in NASH. Hepatology. 2020;72(4):1219-1229. doi: 10.1002/hep.31121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel J, Bettencourt R, Cui J, et al. Association of noninvasive quantitative decline in liver fat content on MRI with histologic response in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2016;9(5):692-701. doi: 10.1177/1756283X16656735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jayakumar S, Middleton MS, Lawitz EJ, et al. Longitudinal correlations between MRE, MRI-PDFF, and liver histology in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 2019;70(1):133-141. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.09.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hutton C, Gyngell ML, Milanesi M, Bagur A, Brady M. Validation of a standardized MRI method for liver fat and T2* quantification. PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0204175. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Idilman IS, Aniktar H, Idilman R, et al. Hepatic steatosis. Radiology. 2013;267(3):767-775. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13121360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tamaki N, Munaganuru N, Jung J, et al. Clinical utility of 30% relative decline in MRI-PDFF in predicting fibrosis regression in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut. 2022;71(5):983-990. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-324264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banerjee R, Pavlides M, Tunnicliffe EM, et al. Multiparametric magnetic resonance for the non-invasive diagnosis of liver disease. J Hepatol. 2014;60(1):69-77. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tonev D, Shumbayawonda E, Tetlow LA, et al. The effect of multi-parametric magnetic resonance imaging in standard of care for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. JMIR Res Protoc. 2020;9(10):e19189. doi: 10.2196/19189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andersson A, Kelly M, Imajo K, et al. Clinical utility of magnetic resonance imaging biomarkers for identifying nonalcoholic steatohepatitis patients at high risk of progression. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(11):2451-2461.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.09.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryan MC, Itsiopoulos C, Thodis T, et al. The Mediterranean diet improves hepatic steatosis and insulin sensitivity in individuals with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2013;59(1):138-143. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parker HM, Johnson NA, Burdon CA, Cohn JS, O’Connor HT, George J. Omega-3 supplementation and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2012;56(4):944-951. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Academies Press . The prevention and treatment of missing data in clinical trials, panel on handling missing data in clinical trials. Published 2010. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/12955/the-prevention-and-treatment-of-missing-data-in-clinical-trials

- 33.Holm S. A simple sequential rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat Theory Appl. 1979;6(2):65-70. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanyal AJ, Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, et al. Endpoints and clinical trial design for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2011;54(1):344-353. doi: 10.1002/hep.24376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.US Food and Drug Administration . Guidance document: noncirrhotic nonalcoholic steatohepatitis with liver fibrosis. December 2018. Accessed January 9. 2024. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/noncirrhotic-nonalcoholic-steatohepatitis-liver-fibrosis-developing-drugs-treatment

- 36.Simon TG, Roelstraete B, Hagström H, Loomba R, Ludvigsson JF. Progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and long-term outcomes. J Hepatol. 2023;79(6):1366-1373. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rinella ME, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Siddiqui MS, et al. AASLD practice guidance on the clinical assessment and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2023;77(5):1797-1835. doi: 10.1097/HEP.0000000000000323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whitlock EP, Burda BU, Williams SB, Guirguis-Blake JM, Evans CV. Bleeding risks with aspirin use for primary prevention in adults. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(12):826-835. doi: 10.7326/M15-2112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loomba R, Mohseni R, Lucas KJ, et al. TVB-2640 (FASN Inhibitor) for the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2021;161(5):1475-1486. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gawrieh S, Noureddin M, Loo N, et al. Saroglitazar, a PPAR-α/γ agonist, for treatment of NAFLD. Hepatology. 2021;74(4):1809-1824. doi: 10.1002/hep.31843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dichtel LE, Corey KE, Haines MS, et al. Growth hormone administration improves nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in overweight/obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;108(12):e1542-e1550. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgad375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Han MAT, Altayar O, Hamdeh S, et al. Rates of and factors associated with placebo response in trials of pharmacotherapies for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(4):616-629.e26. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Original Study Protocol, Statistical Analysis Plan, and Summary of Changes to Protocol

eTable 1. Reasons for Premature End of Treatment

eTable 2. Adherence by Assigned Treatment Group

eTable 3. Baseline Characteristics of Randomized Participants with Complete Month 6 Outcome Data (N=71) and Missing Outcome Data (N=9)

eTable 4. Effect of Daily Aspirin 81 mg as Compared With Placebo on Hepatic Fat and Markers of Inflammation and Fibrosis in the Per-Protocol Population (N=71)

eTable 5. Effect of Daily Aspirin 81 mg as Compared With Placebo on the Primary and Key Secondary End Points Among All Randomized Participants, With Missing Data Imputed as Nonresponses

eTable 6. Effect of Daily Aspirin 81 mg as Compared With Placebo on the Primary and Key Secondary End Points Among All Randomized Participants After Multivariable Adjustment for Prespecified Confounders

eTable 7. Effect of Daily Aspirin 81 mg as Compared With Placebo on the Primary and Key Secondary End Points in the Per-Protocol Population After Multivariable Adjustment for Prespecified Confounders

eTable 8. Effect of Daily Aspirin 81 mg as Compared With Placebo on the Primary and Key Secondary End Points in the Full Randomized Population After Excluding Participants with ≥3% Weight Loss

eTable 9. Effect of Daily Aspirin 81 mg as Compared With Placebo on the Primary and Key Secondary End Points in the Per-Protocol Population After Excluding Participants With ≥3% Weight Loss

eTable 10. Baseline Characteristics of the Post Hoc Subgroup of Randomized Participants With Baseline Hepatic Fat Fraction >20% (N=52)

eTable 11. Post Hoc Subgroup Analysis of the Effect of Daily Aspirin 81 mg as Compared With Placebo on the Primary and Key Secondary End Points Among Participants With Baseline Hepatic Fat Fraction >20%

eTable 12. Post Hoc Analysis of the Effect of Daily Aspirin 81 mg as Compared With Placebo on the Primary and Key Secondary End Points After Excluding 1 Participant From the Placebo Group With >15 kg of Weight Gain During the Treatment Period

eTable 13. Safety Laboratory Measures

eTable 14. Adverse Events

Data Sharing Statement