Asthma is now well understood to be a heterogeneous disease with varying phenotypes, subphenotypes, and endotypes. Allergic asthma is the best-characterized phenotype and the most common asthma phenotype among children and adults. The allergic asthma phenotype is defined as asthma that is triggered by environmental allergens and driven by TH2 cell cellular mechanisms with involvement of IL-4, IL-5, IgE, and broader allergic pathways. Therapeutic innovation has led to a continuous expansion of molecules targeting specific allergic cytokines, cytokine receptors, and antibodies that are effective in the treatment of allergic asthma (eg, omalizumab).1 In contrast, non–TH2 cell asthma is not well characterized, with the categorization of “non–TH2 cell” itself suggesting a relative lack of knowledge in this area that limits identification of cellular targets for therapeutic intervention for patients with this type of asthma pathophysiology. One group of patients who have been noted as often falling into the non–TH2 cell–type asthma phenotype are those with obesity.2

In this issue of the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Akar-Ghibril et al describe their study “High plasma IL-6 levels may enhance the adverse effects of mouse allergen exposure in urban schools on asthma morbidity in children” that was conducted among children enrolled in the School Inner-City Asthma Studies, which were aimed to determine the relationship between plasma IL-6 levels, indoor allergen exposure, and asthma outcomes.3 Over a 5-year period, the School Inner-City Asthma Studies enrolled children who attended schools in the inner city of the northeastern United States. The enrolled children were observed for 1 year for health outcomes via follow-up surveys, lung function and exhaled nitric oxide testing, and dust sampling conducted within the schools. As a premise of their analysis, Akar-Ghibril et al3 describe how IL-6 has been associated with elevated body mass index, metabolic dysfunction, and asthma severity. For example, a prior study conducted among adults enrolled in the Severe Asthma Research Program observed that of the patients with asthma characterized by high IL-6 plasma levels, 75% were obese and more likely to have indicators of metabolic dysfunction, including hypertension, diabetes, and systemic leukocytosis. Akar-Ghibril et al3 therefore describe IL-6 as a biomarker of metabolic dysfunction, and they characterize a subgroup of patients who have asthma along with high IL-6 levels (indicating metabolic dysfunction) and obesity and who also have more severe asthma. They aimed to determine whether plasma IL-6 levels were associated with increased asthma morbidity in this cohort of children exposed to mouse allergen in inner-city schools.

IL-6 is a cytokine synthesized and secreted by many cell types, including monocytes, T cells, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells, and it binds to a specific receptor (IL-6R) that is found on hepatocytes, neutrophils, monocytes, and CD4+ T cells. When IL-6 binds to IL-6R, it is associated with a second transmembrane protein, gp130, which is a signal transducer of IL-6, leading to activation of intracellular signaling pathways such as the Janus kinase–signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT) pathway, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade, and phosphatidylinositide-3-kinase (PI3K). It has been reported that IL-6 results in either an anti-inflammatory or proinflammatory mechanism that is dependent on the levels of IL-6 in the blood and on whether the membrane-bound IL-6R or soluble IL-6R is activated. Membrane-bound IL-6R activation is involved in bacterial defense, epithelial cell proliferation, and prevention of epithelial cell apoptosis. In contrast, soluble IL-6R activation is involved in mononuclear cell recruitment, epithelial cell activation, and inhibition of differentiation of regulatory T cells.4 It has also been reported that levels of soluble IL-6R–bound IL-6 are increased after allergen challenge in patients with asthma.5

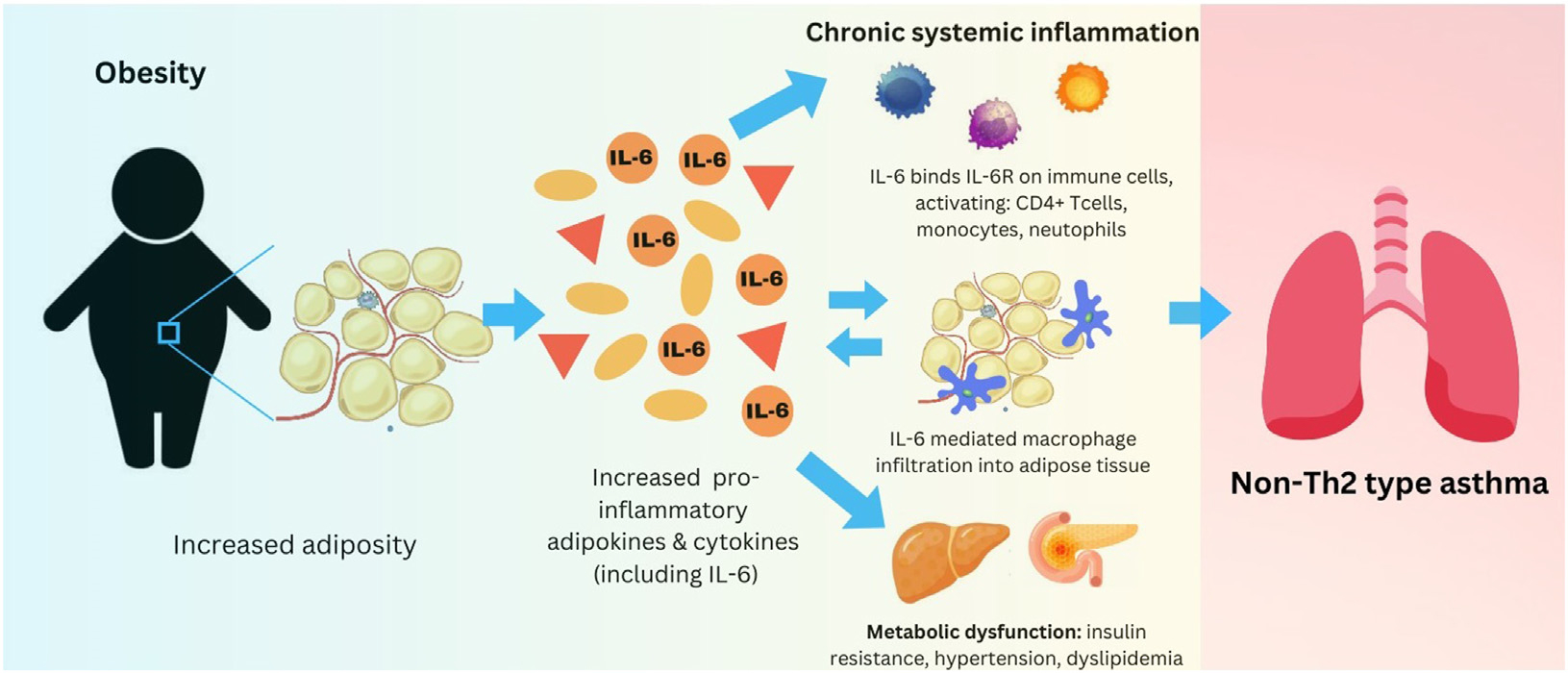

The findings reported by Akar-Ghibril et al3 illustrate how the links between obesity, metabolic dysfunction, and chronic systemic inflammation with elevated IL-6 levels may be relevant in pediatric asthma (Fig 1). Obesity is associated with chronic inflammation, and IL-6 plays a role in creating this characteristic inflammatory milieu. Adipose tissue possesses important endocrine functions, secreting biologically active substances called adipokines. Adipokines, including IL-6, can be proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory, and they can influence a variety of physiologic functions, including reproductive function, blood pressure, and (notably for asthma) immune response and inflammation. In obesity, proinflammatory adipokines dominate, leading to chronic systemic inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in the form of insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. IL-6 signaling is involved in macrophages’ infiltration into adipose tissue, resulting in the establishment of a chronic inflammatory state in individuals with obesity. This systemic inflammation and metabolic dysfunction has been tied to more severe asthma phenotypes in adults and children.6 Additionally, infiltrating macrophages in adipose tissue are a strong predictor of insulin resistance in individuals with obesity, further linking IL-6–related inflammation, obesity, and metabolic dysfunction.7 The relationships between obesity-associated chronic systemic inflammation and non–TH2 cell–type asthma are complex, and the pathophysiologic or inflammatory pathways driving this relationship are less understood, although metabolomic and genomic studies have begun to elucidate more direct pathophysiologic ties in recent years.

FIG 1.

Obesity, IL-6, and non–TH2 cell–type asthma. How obesity, by way of increased levels of proinflammatory adipokines and cytokines such as IL-6, is related to both metabolic dysfunction and chronic, systemic inflammation that contributes to the non–TH2 cell–type inflammation seen in obese asthma. Various proinflammatory adipokines induce metabolic dysfunction. IL-6 is a prominent inflammatory cytokine that is produced when excess adipose tissue is present, leading to (1) further immune system activation (non–TH2 cell–type inflammation) and (2) macrophage infiltration of adipose tissue, thus perpetuating the cycle of chronic, systemic non–TH2 cell–type inflammation that may play a role in obese asthma.

IL-6 is a well-known cytokine associated with obesity-related asthma and non–TH2 cell–type inflammation, and it has been considered as a therapeutic target for patients exhibiting a high IL-6/obese severe asthma phenotype.8 Therapeutics targeting the IL-6 inflammatory pathway generally fall within 3 primary categories: mAbs binding IL-6, mAbs binding the IL-6 receptor or other membrane proteins in the receptor complex (ie, gp130), and mAbs blocking downstream signal proteins within the IL-6 funnel (eg, JAK STAT), leading to inhibition of the proinflammatory transcription caused by IL-6 signal transduction. IL-6 mAb therapies (eg, tocilizumab, sarilumab) are US Food and Drug Administration–approved for the treatment of other inflammatory diseases such as rheumatologic conditions, inflammatory bowel disease, and (more recently) coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia. To date, only a few small pilot studies of IL-6 blockade have been conducted among patients with asthma.9,10 Esty et al described the treatment of 2 children with severe persistent nonatopic TH2 and TH17 cell mix–type asthma with tocilizumab, a humanized anti–IL-6R mAb. After treatment, the patients exhibited improvement in both clinical and immunologic outcomes, including fewer hospital admissions, fewer oral corticosteroids, and decreased TH17 cell (a cell type upregulated by IL-6 stimulation) response.10 A small randomized controlled trial of 11 adults with well-controlled asthma, in which participants completed 2 allergen inhalation challenges before treatment with a dose of tocilizumab or placebo, found no difference in severity of allergen-induced bronchoconstriction (based on pulmonary function testing) between tocilizumab and placebo. These findings may suggest that IL-6R blockade could be less beneficial in individuals with allergic asthma. A larger-scale phase 2 trial of clazakizumab, a humanized rabbit mAb against IL-6, is under way as part of the PrecISE trial, which seeks to identify effective precision medicine–based therapies for severe asthma phenotypes. Finally, a phase 2 trial of FB704A, an anti– IL-6 mAb, is also being conducted among adults with severe asthma to assess safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and overall clinical activity. Results are pending for both of these ongoing clinical trials.

A cross-sectional analysis performed by Akar-Ghibril et al3 found that increased plasma IL-6 level was associated with higher body mass index, C-reactive protein level, and blood neutrophils and that longitudinally, children with high plasma IL-6 levels had more asthma symptoms. Furthermore, the combination of high IL-6 level and higher mouse allergen exposure was associated with decreased measures of lung function in these children. These findings suggest that IL-6 may play a critical role in asthma pathophysiology among children with specific conditions such as obesity and allergen exposure. However, this study does not allow us to determine which is the “chicken” and which is the “egg.” Akar-Ghibril et al3 conclude that a high plasma IL-6 level increases susceptibility to mouse allergen exposure. Does a high IL-6 level drive susceptibility to specific allergen exposure and poorer asthma outcomes, or is a high IL-6 level a consequence of environmental exposures, including obesity? Whether the children in this cohort had previous mouse allergen exposure or other conditions that may have influenced the observed high IL-6 levels is not clear. Also unclear is whether obesity was an influence on elevated IL-6 levels and the effects of exposure to mouse allergen. These questions could be answered in longer longitudinal birth cohort studies and could further elucidate the specific role of IL-6 in pediatric asthma among varying environmental exposures. Future studies are needed to determine how obesity and environmental allergens interact in the pathogenesis of asthma. Nevertheless, these current findings add to the existing literature and evidence that molecules targeting the IL-6 pathway may lead to novel and effective therapies for patients with non–TH2 cell asthma, who currently lack of effective targeted treatment options.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grants R01 HD100545 [to B.L.J.]) and T32 HD069038 (to K.E.K.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pandya A, Adah E, Jones B, Chevalier R. The evolving landscape of immunotherapy for the treatment of allergic conditions. Clin Transl Sci 2023;16:1294–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sutherland ER, Goleva E, King TS, Lehman E, Stevens AD, Jackson LP, et al. Cluster analysis of obesity and asthma phenotypes. PLoS One 2012;7:e36631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akar-Ghibril N, Greco KF, Jackson-Browne M, Phipatanakul W, Permaul P. High plasma IL-6 levels may enhance the adverse effects of mouse allergen exposure in urban schools on asthma morbidity in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2023;152:1677–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schaper F, Rose-John S. Interleukin-6: biology, signaling and strategies of blockade. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2015;26:475–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morjaria JB, Babu KS, Vijayanand P, Chauhan AJ, Davies DE, Holgate ST. Sputum IL-6 concentrations in severe asthma and its relationship with FEV1. Thorax 2011;66:537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pite H, Aguiar L, Morello J, Monteiro EC, Alves AC, Bourbon M, et al. Metabolic dysfunction and asthma: current perspectives. J Asthma Allergy 2020;13:237–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klöoting N, Fasshauer M, Dietrich A, Kovacs P, Sch€on MR, Kern M, et al. Insulinsensitive obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2010;299:E506–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Permaul P, Peters MC, Petty CR, Cardet JC, Ly NP, Ramratnam SK, et al. The association of plasma IL-6 with measures of asthma morbidity in a moderate-severe pediatric cohort aged 6–18 years. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021;9:2916–9.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Revez JA, Bain LM, Watson RM, Towers M, Collins T, Killian KJ, et al. Effects of interleukin-6 receptor blockade on allergen-induced airway responses in mild asthmatics. Clin Transl Immunol 2019;8:e1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esty B, Harb H, Bartnikas LM, Charbonnier LM, Massoud AH, Leon-Astudillo C, et al. Treatment of severe persistent asthma with IL-6 receptor blockade. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019;7:1639–42.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]