ABSTRACT

Control measures are being introduced globally to reduce the prevalence of antibiotic resistance (ABR) in bacteria on farms. However, little is known about the current prevalence and molecular ecology of ABR in bacterial species with the potential to be key opportunistic human pathogens, such as Escherichia coli, on South American farms. Working with 30 dairy cattle farms and 40 pig farms across two provinces in central-eastern Argentina, we report a comprehensive genomic analysis of third-generation cephalosporin-resistant (3GC-R) E. coli, which were recovered from 34.8% (cattle) and 47.8% (pigs) of samples from fecally contaminated sites. Phylogenetic analysis revealed substantial diversity suggestive of long-term horizontal and vertical transmission of 3GC-R mechanisms. CTX-M-15 and CTX-M-2 were more often produced by isolates from dairy farms, while CTX-M-8 and CMY-2 and co-carriage of amoxicillin/clavulanate resistance and florfenicol resistance were more common in isolates from pig farms. This suggests different selective pressures for antibiotic use in these two animal types. We identified the β-lactamase gene blaROB, which has previously only been reported in the family Pasteurellaceae, in 3GC-R E. coli. blaROB was found alongside a novel florfenicol resistance gene, ydhC, also mobilized from a pig pathogen as part of a new composite transposon. As the first comprehensive genomic survey of 3GC-R E. coli in Argentina, these data set a baseline from which to measure the effects of interventions aimed at reducing on-farm ABR and provide an opportunity to investigate the zoonotic transmission of resistant bacteria in this region.

IMPORTANCE

Little is known about the ecology of critically important antibiotic resistance among bacteria with the potential to be opportunistic human pathogens (e.g., Escherichia coli) on South American farms. By studying 70 pig and dairy cattle farms in central-eastern Argentina, we identified that third-generation cephalosporin resistance (3GC-R) in E. coli was mediated by mechanisms seen more often in certain species and that 3GC-R pig E. coli were more likely to be co-resistant to florfenicol and amoxicillin/clavulanate. This suggests that on-farm antibiotic usage is key to selecting the types of E. coli present on these farms. 3GC-R E. coli and 3GC-R plasmids were diverse, suggestive of long-term circulation in this region. We identified the de novo mobilization of the resistance gene blaROB from pig pathogens into E. coli on a novel mobile genetic element, which shows the importance of surveying poorly studied regions for antibiotic resistance that might impact human health.

KEYWORDS: zoonotic infections, cephalosporin, cattle, swine, genomics

INTRODUCTION

There are very few published reports of third-generation cephalosporin-resistant (3GC-R) Escherichia coli from farmed animals in South America. In Uruguay, a 2016 study reported that only 1% of bovine calves excreted 3GC-R E. coli, which was conferred by the production of CTX-M-15 (1). Positivity rates in Brazilian cattle were 18% of samples in a 2014 survey (2). In Uruguayan pigs, 72% of samples were positive for 3GC-R E. coli in 2016, with CTX-M-8, CTX-M-14, CTX-M-15, SHV-12, and CMY-2 identified as mechanisms (1). In Argentinian pigs, 3GC-R E. coli were also common in 2017 (82% of samples were positive), caused by multiple CTX-M variants (3). In contrast, a 2012 survey performed in Brazil reported that only 3% of samples from pigs were positive (4). In more recent years, CTX-M producers have been found in wild animal reservoirs, e.g., vampire bats in Peru, though at a lower prevalence than the 48% of sampled livestock that excreted 3GC-R E. coli (5). In Chile, however, only 3% of livestock samples were positive in a 2019 survey of small-scale farming operations with low use of cephalosporins (6). Generally, however, given a paucity of data and variations in sampling structure as well as methods for selecting resistant bacteria and identification of resistance genes in these previous studies, it is difficult to draw general conclusions about the prevalence and mechanisms of 3GC-R excreted by production animals in South America.

There is much interest in the possibility that resistant non-toxigenic E. coli emerging on farms might colonize human populations through the ingestion of food or interaction with environments contaminated with farm animal feces. It is possible that such zoonotic transmission could exacerbate the rise of resistant infections in humans, either because mobile resistance genes carried by the zoonotically acquired bacteria transfer into human commensals or because zoonotically acquired commensals cause, at some point in the future, a resistant opportunistic infection. Because of this possibility, countries commonly include reducing antibiotic use in farming as a central pillar of their published antimicrobial resistance (AMR) action plans. In 2015, the Argentinian government adopted the concept of “One Health,” as promoted by the World Organization for Animal Health and the World Health Organization, and the Argentine Strategy for the Control of Antimicrobial Resistance was formalized. In 2022, a new law concerning the Prevention and Control of Antimicrobial Resistance was enacted, which specifically aims to ensure the responsible use of antibiotics and regulate issues related to the sale and use of these drugs, both in human and animal health (https://www.boletinoficial.gob.ar/detalleAviso/primera/270118/20220824).

Our aim in this work was to perform large-scale sampling of pig and dairy cattle farms in two regions in central-eastern Argentina to assess the current prevalence and molecular epidemiology—based on whole-genome sequencing (WGS)—of 3GC-R E. coli on farms in this under-sampled region. These data, collected 1 year before the law aimed at reducing AMR prevalence on farms (described above) was enacted, might in the future be used to measure the impact of resulting interventions, and to test for zoonotic transmission through phylogenetic analysis in comparison with 3GC-R E. coli isolates from humans in the same region.

RESULTS

Animal-specific 3GC-R E. coli sample-level positivity and resistance mechanisms

Samples from fecally contaminated environments, effluent, and animal drinking water were collected at two separate visits from 40 pig farms (404 samples) and 30 dairy cattle farms (310 samples) between 22 March 2021 and 30 August 2021.

The numbers of farms, the numbers of samples collected, and the percentage of farms and samples positive for 3GC-R E. coli from each type of animal and each region are shown in Fig. S1 and Table 1. Overall, 33.9% (n = 242) of samples and 88.6% (n = 62) of farms were positive for 3GC-R E. coli. Only 1 of the 142 drinking water samples was positive, however, so considering only the fecal and effluent samples, 42.1% of samples were positive for 3GC-R E. coli. Fecal samples were more likely to be positive than effluent samples (OR 2.16; 95% CI 1.37–3.39) (Table 2). After accounting for clustering by farm and adjusting for sample type, there was no statistically significant difference in positivity among samples taken from pig farms compared to dairy farms (OR 0.41; 95% CI 0.12–1.47). However, on cattle farms, but not pig farms, there was a reduction in sample-level positivity on Visit 2, made in the winter season, compared with Visit 1, made in the autumn (OR 0.41; 95% CI 0.22–0.74) (Table 2). Samples collected in the Río Cuarto region were more likely to be positive than those from La Plata (OR 3.62; 95% CI 1.87–7.02) (Table 2). Only eight farms (two pig and five dairy farms in La Plata, and one dairy farm in Río Cuarto) were negative for 3GC-R E. coli across all samples collected (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Details of sample-level positivity for 3GC-R E. coli among samples from pigs and dairy cattle, including or excluding drinking water samples

| Number of farms | Number of samples | Number (%) of 3GC-R E. coli-positive farms | Number (%) of 3GC-R E. coli-positive samples | % of total positive samples | Number (%) of total 3GC-R E. coli sequenced | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| La Plata dairy | 22 | 230 | 17 (77.3) | 54 (23.5) | 22.3 | 34 (21.0) |

| Excluding drinking water | 22 | 186 | 17 (77.3) | 54 (29.0) | 22.4 | 34 (21.0) |

| La Plata pig | 30 | 300 | 28 (93.3) | 99 (33.0) | 40.9 | 66 (40.7) |

| Excluding drinking water | 30 | 240 | 28 (93.3) | 99 (41.3) | 41.1 | 66 (40.7) |

| Río Cuarto dairy | 8 | 80 | 7 (87.5) | 34 (42.5) | 14.0 | 24 (14.8) |

| Excluding drinking water | 8 | 64 | 7 (87.5) | 33 (51.6) | 13.7 | 24 (14.8) |

| Río Cuarto pig | 10 | 104 | 10 (100) | 55 (52.9) | 22.7 | 38 (23.5) |

| Excluding drinking water | 10 | 82 | 10 (100) | 55 (67.1) | 22.8 | 38 (23.5) |

| Total | 70 | 714 | 62 (88.6) | 242 (33.9) | 162 | |

| Excluding drinking water | 70 | 572 | 62 (88.6) | 241 (42.1) | 162 |

TABLE 2.

Mixed-effects model for 3GC-R E. coli positivity in samples from pig and cattle farms across the two study regionsa

| Random effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | Number of groups | Variance | S.D. | ||

| Farm | 70 | 0.836 | 0.915 | ||

S.D., standard deviation; S.E., standard error; CI, confidence interval; LP, La Plata; and RC, Río Cuarto.

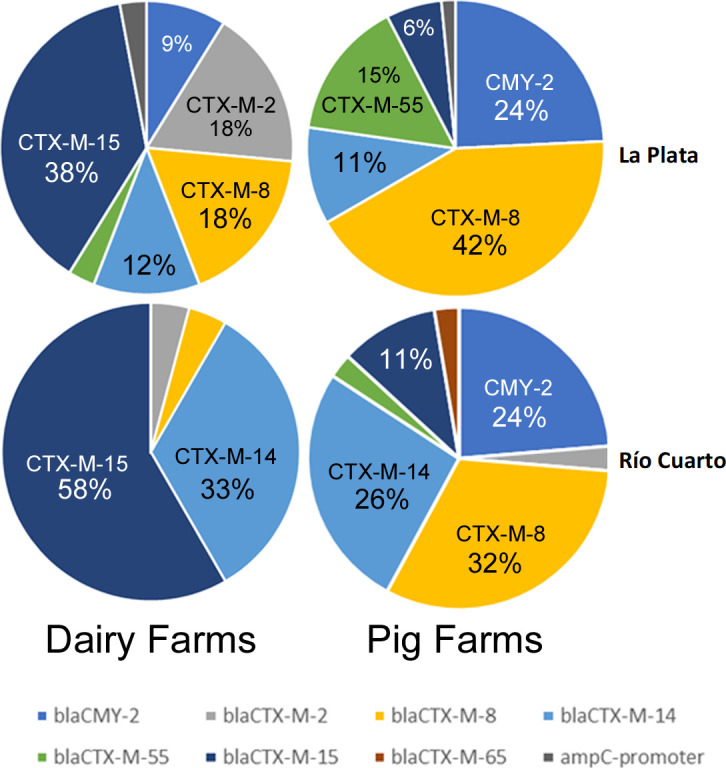

From the 242 positive samples, 442 3GC-R isolates were picked from selective plates and shipped from Argentina to the United Kingdom. On receipt, 320 3GC-R isolates could be recovered, excluding mixed cultures. A combination of resistance gene-specific PCR and random amplified polymorphic DNA PCR (RAPD-PCR) was used to deduplicate isolates having the same RAPD-PCR and resistance gene profile from those recovered from the same farm during the same visit; 163 representative 3GC-R E. coli were selected for WGS in this way. One set of WGS data failed to meet quality control standards, leaving data for 162 isolates (Table 1). A full analysis of these data showing isolate source (farm number and animal type), E. coli sequence type (ST), and resistance genes identified is provided in Table S1. This analysis revealed a wide range of 3GC-R mechanisms, dominated by CTX-M variants (Fig. 1). Among the farms with sequenced isolates, four 3GC-R mechanisms demonstrated statistically significant associations with either pig or dairy farms (Fig. 1). CMY-2 was responsible in 25 sequenced 3GC-R isolates from 14 different pig farms but only three dairy isolates all from the same farm (Fisher’s exact test, P = 0.02, when detection of each 3GC-R mechanism was classified at farm level). Similarly, CTX-M-8 was the mechanism in 40 pig isolates across 22 farms but on only five dairy farms (P = 0.01). In contrast, CTX-M-2 was the mechanism in only a single pig isolate but was the mechanism in seven dairy farm isolates, recovered from samples collected across five farms (P = 0.02). Most strikingly, CTX-M-15 was the mechanism in 3GC-R E. coli on six pig farms but was found in 27 dairy isolates across 14 farms (P 0.001).

Fig 1.

Percentage of 3GC-R E. coli isolates from cattle and pigs in two regions of Argentina expressing particular 3GC-R mechanisms.

Animal-specific co-resistance genotypes among 3GC-R E. coli

In terms of other important resistance genes carried among the 162 sequenced 3GC-R E. coli isolates (Table S1, summarized in Table S2), the florfenicol resistance gene floR was more likely to be detected in 3GC-R E. coli on pig (65 isolates across 30 farms) than dairy farms (three isolates from three different farms, Fisher’s exact test, P 0.001). 3GC-R pig isolates were also far more likely to carry genotypes associated with amoxicillin/clavulanate resistance. Overall, 54 isolates across 26 pig farms carried one or more amoxicillin/clavulanate resistance genes/variants, compared to nine cattle isolates from only six farms (P 0.001). One common mechanism of amoxicillin/clavulanate resistance is the production of an AmpC enzyme (7). As previously mentioned, the plasmid-mediated AmpC gene blaCMY-2 was more commonly detected in 3GC-R E. coli on pig farms than in dairy farms. A second mechanism of amoxicillin/clavulanate resistance is the production of an OXA enzyme (7). Carriage of blaOXA genes in 3GC-R E. coli was detected on two dairy and six pig farms, which did not suggest a species association (P = 0.7) (Tables S1 and S2). A third possible mechanism for amoxicillin/clavulanate resistance is TEM-1 hyper-production (7). No statistically significant difference in the detection of 3GC-R E. coli carrying blaTEM-1 was found from pig farms (70 isolates from 31 farms) compared to dairy farms (28 isolates from 13 farms, P = 0.06). However, genetic features associated with TEM-1 hyper-production (7) were observed more commonly (P = 0.003) among blaTEM-1-positive E. coli from pig farms (32 isolates, 20 farms) than from cattle farms (three isolates, three farms) (Fig. S2; Tables S1 and S2).

We next considered genetic linkage between specific 3GC-R mechanisms and genes responsible for resistance to other agents. Of the 23 qnr-positive 3GC-R cattle isolates, representing 16 STs and collected from 10 farms, 22 isolates carried qnrS1 alongside blaCTX-M-15 and blaTEM-1 (Table S3). Three out of seven blaCTX-M-15-positive pig isolates also carried blaTEM-1 and qnrS1 (Table S4).

Of the remaining five blaCTX-M-15-positive cattle isolates, three (all ST44) carried blaOXA-1, aac(6′)-Ib-cr and aac (3)-IIa (Table S3), with blaOXA-1 and aac(6′)-Ib-cr carried on the same composite transposon [IS26-aac(6′)-Ib-cr, blaOXA-1,catB(truncated)-IS26]. In pigs, all four remaining blaCTX-M-15-positive isolates were also ST44 and carried blaOXA-1; two also carried the IS26-aac(6′)-Ib-cr, blaOXA-1, catB(truncated)-IS26 transposon but lacked aac (3)-IIa, while two carried blaOXA-1 as part of a shorter transposon [IS26-blaOXA-1,catB(truncated)-IS26] plus aac (3)-IIa.

The only other notable genetic linkage was found among pig isolates, in that 9 out of 11 ST48 pig isolates carried blaCMY-2, representing 36% of all blaCMY-2-positive pig isolates, though these were distributed across eight farms and both regions.

Mobilization of blaROB into E. coli

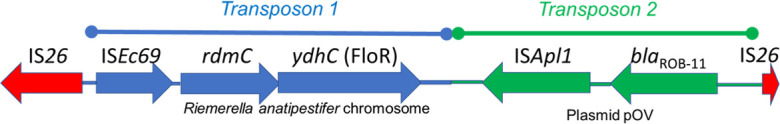

One unexpected finding from this study was the identification of blaROB in five 3GC-R E. coli isolates (Tables S1 to S4), the first time that this gene has been reported in the Enterobacterales. Three isolates were ST48 from three pig farms in the La Plata region, one was an ST3339 isolate from La Plata pigs, and the fifth isolate was ST86, from a Río Cuarto cattle farm. blaROB was found in isolates producing CTX-M-14, -15, -8, and CMY-2. Analysis of the four blaROB-positive 3GC-R E. coli isolates from pigs identified, in each case, an approximately 6.5 kb composite element not previously seen on the NCBI database (Fig. 2). The element is flanked by two copies of IS26 and includes two composite transposons.

Fig 2.

Architecture of a novel mobile genetic element fusing florfenicol and β-lactam resistance and mobilizing blaROB into E. coli in Argentina.

Transposon 1 includes two adjacent genes, mobilized from the chromosome of the Flavobacteriales species Riemerella anatipestifer by the IS1595-family element, ISEc69. The two genes carried on transposon 1 are rdmC, annotated as encoding an “Alpha/Beta Hydrolase” of unknown function and ydhC. Blastn searches revealed that only six E. coli NCBI database entries include a rdmC gene with 100% coverage and >95% identity. Four of the six were from pigs or pork in the USA, one was from human feces in the USA (8), and one was from the USA, but the sample type was not defined. YdhC is 98.5% identical, with 98% coverage, to the archetypal florfenicol resistance transporter FloR (Fig. S3) (9), which was identified in all other blaROB-negative, FloR-positive 3GC-R E. coli isolates found in this study (Tables S1 and S2). The ydhC variant of floR could not be found outside the chromosome of R. anatipestifer using Blastn. Disc susceptibility testing confirmed that all four ROB/YdhC-positive 3GC-R pig E. coli isolates identified here are florfenicol resistant.

Transposon 2 in this 6.5-kb element (Fig. 2) is >99% identical to the classical blaROB transposon from Pasteurella multocida plasmid pOV, obtained from a Mexican pig (10), including the ISApl1 element that mobilized blaROB.

In two out of four blaROB-positive pig isolates in this study, WGS data were sufficient to allow the prediction of genomic location. In both cases, the 6.5-kb element encoding ROB was located on a plasmid, but in each case, the plasmid was different. Based on Blastn, one was highly similar to a variety of IncR E. coli plasmids found in samples from pigs from China, Thailand, and the UK (e.g., pRHB28-C19_2; accession number: CP057369.1). The second was similar to the group of IncI1 plasmids, with the closest match being a plasmid from pigs in Portugal (accession number: KY964068.1).

The blaROB-positive 3GC-R E. coli cattle isolate, which was the only blaROB-positive isolate from the Río Cuarto region, did not appear to have the full 6.5-kb ROB-encoding element, lacking the ydhC (floR) variant and having an ISEc69-rdmC cluster separately from the ROB-encoding transposon. The limitations of short-read sequencing meant we could not confirm plasmid location, but this cattle isolate only carried an IncY plasmid, so the location of blaROB cannot be the same as in the La Plata pig isolates. The mobilized ROB variant was ROB-11, as in the pig isolates.

Limited evidence of farm-to-farm transmission of 3GC-R E. coli or epidemic 3GC-R plasmid transmission

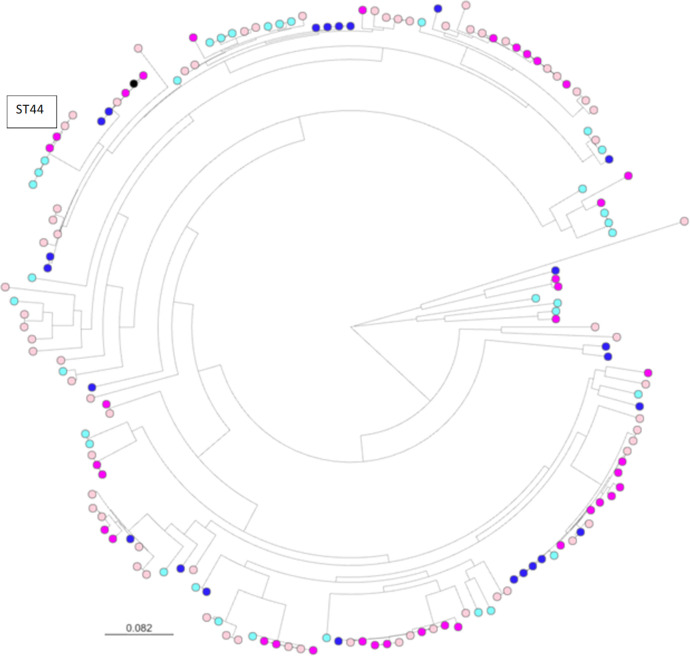

Across 162 sequenced isolates, 63 previously known STs were identified (Table S1). Eighteen isolates were from previously unknown STs. These isolates were distributed across 14 new ST designations. The most frequently observed STs were ST10 and ST48—which, as discussed above, were most frequently found in isolates from pigs—ST58 and ST44 (Table S5). However, phylogenetic analysis based on core genome alignment revealed that a diverse set of 3GC-R isolates has been recovered in this survey (Fig. 3). Of the 162 sequenced isolates, 47 isolates could be constituted into 21 “clones” where pairs of isolates were separated by <15 core genome single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (Table S6). Of these, only six clones were found in samples from two separate farms, and none spanned more than two farms. None of these clones were found in more than one animal species and only one was found in both regions, a pair of ST58 (blaCTX-M-8) isolates found on pig farms >500 km apart (Table S7).

Fig 3.

Core genome phylogeny of 3GC-R E. coli from Argentinian farms. Sequence alignments were with Snippy. Maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees were constructed using RAxML, utilizing the GTRCAT model of rate heterogeneity and the software’s autoMR and rapid bootstrap. Pink nodes are pig isolates, blue nodes are cattle isolates, and black is the reference. Dark colors represent isolates from farms near La Plata, light colors represent isolates from farms near Río Cuarto.

Perhaps most importantly, we observed evidence for farm-to-farm sharing of two ST44 [blaCTX-M-15, IS26-aac(6′)-Ib-cr, blaOXA-1,catB(truncated)-IS26] clones. One sharing event was identified between Río Cuarto pig farms separated by 20 km; another event, where the plasmid also carried a gentamicin resistance gene, was between La Plata dairy farms 4 km apart (Table S7). These clones are predicted to be resistant to all first- and second-line antibacterials used for the treatment of bloodstream infections in humans (3GCs, amoxicillin/clavulanate, piperacillin/tazobactam, ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, tobramycin, amikacin and—in the La Plata dairy farm clone only—gentamicin). A third ST44 [blaCTX-M-15, IS26-blaOXA-1, catB(truncated)-IS26] clone, which also carried a gentamicin resistance gene, was observed in two samples from the same La Plata pig farm. These three ST44 clones differed from each other by >250 SNPs (Fig. 3).

We next considered the possibility that epidemic plasmids might be involved in the dissemination of 3GC-R mechanisms in the study region (Table S1). Among 160 isolates (i.e., excluding the two chromosomal ampC hyper-producers), seven isolates had an obviously chromosomally encoded 3GC-R mechanism (two ST2144 CMY-2-producing isolates from the same farm plus four CTX-M-15 producing and one CTX-M-2-producing isolate, each from a different ST and farm). In 81 isolates, it was not possible to determine location due to the limitations of short-read sequence assembly (Table S1). The remaining 72 isolates carried 3GC-R on a plasmid. Of these, CTX-M-2 (four isolates, four farms, and four STs), CTX-M-55 (two isolates, two farms, and two STs), and CTX-M-65 (one isolate) were not numerous enough to consider plasmid ecology in detail. However, 16 isolates carried obviously plasmid-mediated CMY-2 (eight farms, 12 STs) with blaCMY-2 present on the same contig as replicon types IncX4 (five isolates, three farms, and four STs), IncC (one isolate), and IncI1-1(Alpha) (nine isolates, five farms, and eight STs). The remaining isolate did not carry any replicon on the same contig as blaCMY-2 (Table S1).

Also obviously plasmid encoded was CTX-M-15 (21 isolates, 11 farms, and 16 STs) with blaCTX-M-15 present on the same contig as replicon type IncY in one isolate (56794; Table S1). This 68-kb contig was almost 100% identical to a portion of sequenced plasmid p17-AB00432 (accession number: MT158480.1) from the cecum of a German calf. blaCTX-M-15 did not share a contig with a replicon in the other 20 blaCTX-M-15-positive isolates, but 19 of them did have an IncY replicon on another contig (Table S1). Read mapping confirmed that all 19 carried a close variant of p17-AB00432, which carries blaCTX-M-15, blaTEM-1, qnrS1, dfrA14, sul2, and tet(A). There was some isolate-to-isolate variation between these plasmids (Fig. S4), but all of them (which were all from cattle, found in both Argentinian study regions) carried blaTEM-1 and qnS1, with most also carrying sul2, tet(A), and dfrA14 (Table S1). The existence of this family of closely related plasmids explains the observed linkage between blaCTX-M-15, blaTEM-1, and qnS1 among cattle isolates reported above. The remaining obviously plasmid-associated blaCTX-M-15-positive IncY-replicon-negative isolate carried blaOXA-1 and drfA17, and blaCTX-M-15 shared a contig with an IncFIA/FIB(AP001918)/FII replicon type (Table S1).

CTX-M-14 was obviously plasmid-mediated in 15 isolates (10 farms and 12 STs). In one blaCTX-M-14-positive isolate, the replicon found on the same contig as blaCTX-M-14 was IncFIA(HI1)/IncFIB(K), but in 11 isolates, blaCTX-M-14 shared a contig with an IncI1-I(Alpha) replicon (Table S1). The closest matching blaCTX-M-14-positive IncI1-I(Alpha) plasmid on the database was pB16EC0481-4 (accession number: CP088801.1) from a human blood sample in Korea, with 99% identity across 80 kb of sequence. The remaining three isolates carried no replicon on the same contig as blaCTX-M-14 but carried an IncI1-I(Alpha) replicon type on another contig. Read mapping for all 14 blaCTX-M-14-positive IncI1-I(Alpha)-positive isolates against pB16EC0481-4 revealed multiple plasmid types with interspersed and diverse regions of sequence (Fig. S5).

CTX-M-8 was plasmid associated in 13 isolates (11 farms and 12 STs), of which in 12, an IncI1-I(Alpha) replicon was again located in the same contig as blaCTX-M-8 and in the remaining isolate, an IncI1-I(Alpha) replicon was present on another contig. The closest blaCTX-M-8-carrying IncI1-I(Alpha) plasmid on the database was a 101 kb plasmid pA117-CTX-M-8 (accession number: MN816371.1) from animal feces in Brazil, sharing greater than 99% identity with the blaCTX-M-8-containing contig from at least one of the Argentinian isolates. Again, read mapping of all blaCTX-M-8-positive IncI1-I(Alpha)-positive isolates against pA117-CTX-M-8 revealed a similar pattern to that seen previously, with all plasmids matching strongly with the reference, but with substantial diversity within the population (Fig. S6).

DISCUSSION

There has been little analysis of 3GC-R E. coli in samples from production animals in South America, which includes some of the world’s largest and fastest-growing animal farming industries. This is the largest study to date. In pigs and dairy cattle from two regions in central-eastern Argentina, we identified high percentages of sample-level 3GC-R E. coli positivity using a method that selects for extended spectrum β-lactamase- (ESBL-) and AmpC-producing E. coli. Most isolates recovered, however, produced ESBLs of various CTX-M types. When excluding drinking water samples (where only 1 of the 142 samples was positive), sample-level 3GC-R E. coli positivity for cattle and pigs was 34.8% and 47.8%, respectively. However, a mixed-effects model suggested that this apparent difference between species was largely driven by a drop in sample positivity in cattle in the second sampling visit, carried out during the winter season, and that the prevalence of 3-GCR in the two species during the first visit was very similar. Further investigation of this difference is warranted. The prevalence can be compared with similar studies in other countries, though, as has been discussed in a recent systematic review (11), differences in sampling strategy and selection make comparisons difficult. Key differences include the use of an initial selective enrichment step (not used here) designed to lower the limit of detection, increasing the observed prevalence of resistance by increasing test sensitivity, and the selective antibiotic used [here, we used cefotaxime, which was the most common selective agent in the systematic review of 3GC-R E. coli studies from pig samples globally (11)].

ESBL E. coli sample-level positivity was <5% in Canadian dairy cattle (12), though this survey used freeze/thawed fecal samples, and no in-plate selection, with isolates presumptively identified as ESBL producers following MIC testing of a selection of E. coli colonies. It has been previously reported that fecal sample freezing can, in some cases, reduce positivity rates for AMR at the sample level (13). ESBL E. coli positivity was also <5% in a study of Malaysian dairy cattle (14), though, again, samples were plated onto non-selective agar and E. coli were then phenotypically tested for ESBL production. However, in a study of English dairy farms using almost identical sample collection and processing methods to that used in this Argentinian study, sample-level positivity for 3GC-R E. coli was 9.3% (15), of which just under half were ESBL producers. It is known that animal age is important for finding 3GC-R E. coli in cattle (15, 16), but the distribution of cattle samples in this Argentinian study was not substantially biased toward young animals, so this does not explain the observed high prevalence of 3GC-R E. coli. On the other hand, sample-level 3GC-R E. coli positivity rates among cattle reported here were not particularly high compared with the most contemporaneous study from South America—Peru—where positivity was 48% using almost identical methods to those used here (5). Furthermore, in recent Spanish (17) and Chinese (18) cattle surveillance studies, 3GC-R E. coli positivity was 32.9% and 29%, respectively, though the former used a pre-enrichment step using cefotaxime, which is highly likely to elevate sample-level positivity; enrichment was not used in this Argentinian study.

In this study, 3GC-R E. coli positivity seen in pigs was typical of what is seen globally (11). Additionally, we noted that the 3GC-R isolates from pig farms were more likely to carry genes associated with florfenicol and amoxicillin/clavulanate resistance than those from cattle farms. We conclude that genotypically predicted amoxicillin/clavulanate resistance is more widespread among 3GC-R E. coli from pig farms through higher rates of blaCMY-2 carriage and higher rates of blaTEM-1 hyper-expression. Others have reported more extensive drug resistance in 3GC-R E. coli in pigs than cattle when collected in parallel, for example, in South Korea (19, 20) and in China (21). In the Argentinian farms studied here, this is likely to reflect the balance of florfenicol and amoxicillin/clavulanate used in pig versus dairy cattle farms, and we aim to provide future epidemiological analysis of 3GC-R E. coli presence on these farms following medicine usage and management practice surveys. In the absence of this specific analysis, there is very little known about antimicrobial usage on pig and dairy farms in Argentina. Only one paper could be identified covering this and considering 200 dairy farms in Buenos Aires province (22). Notably, amoxicillin/clavulanate was not reported as being used at all and florfenicol was only used parenterally in cows, unlike many other agents. This, therefore, supports a hypothesis of relatively low usage of these two agents on dairy farms—at least in 2015 when the study was published—but a more detailed analysis will be required to further test this hypothesis.

It was also interesting to note that the type of CTX-M found as the 3GC-R mechanism in our study was significantly different between pig and cattle farms, with CTX-M-15 (a Group 1 CTX-M) and CTX-M-2 being more common in cattle, and CTX-M-8 being more common in pigs. Indeed, in a parallel sampling study in Italy, CTX-M-15 was also found more commonly to cause 3GC-R in cattle than in pigs (23), though in Canada little difference was seen (24). It may be that any animal-specific imbalance in CTX-M group dominance results from an imbalance between third- and fourth-generation cephalosporin use since different CTX-M types are known to have different spectra of activity against different cephalosporins (25). A recent study of English dairy cattle also found that Group 1 CTX-M enzymes (in this case, CTX-M-32) were the predominant ESBLs seen (26) and showed that the use of fourth-generation cephalosporins was associated with the odds of finding CTX-M-producing E. coli in samples from these farms (15).

A related observation from this Argentinian study is that CMY-2 was more commonly found as the 3GC-R mechanism in isolates from pigs than from cattle, and again this could result from an imbalance in third- and fourth-generation cephalosporin use in cattle and pigs since CMY-2 does not hydrolyze fourth-generation cephalosporins, as is typical of most AmpC-type enzymes (27). Again, evidence of antimicrobial usage in Argentinian farms is limited, but, notably, in the published 2015 survey of Argentinian dairy farms (22), third-generation cephalosporins were used less than most other parenteral antibiotics, and fourth-generation cephalosporins were not used at all as a dry cow therapy. How this relates to the situation in 2021 (the time of our survey of 3GC-R) on our study farms remains to be determined.

The other striking finding here is the sheer diversity of 3GC-R E. coli, both mechanistically, phylogenetically, and in terms of the mobile genetic elements involved, suggesting the mobile 3GC-R mechanisms identified have been extensively circulating for many years. 3GC-R mechanisms were found encoded on a wide variety of plasmids, though there was evidence that blaCTX-M-15 was commonly (20/34 blaCTX-M-15-positive isolates) carried on closely related variants of an IncY plasmid co-carrying blaTEM-1 and qnrS1, which is clearly circulating in the region (Fig. S4). Furthermore, two groups of related IncI1-I(Alpha) plasmids were involved in the dissemination of blaCTX-M-14 and blaCTX-M-8, respectively, though these are more diverse than the IncY group (Fig. S4 to S6). As is common for short-read sequence data, a large proportion (50%) of the WGS data sets did not allow us to test for plasmid location, though it is likely that many of these isolates have plasmid-mediated 3GC-R genes. However, these encoded varied mechanisms, and the isolates carried varied additional resistance genes (Table S1), meaning that the presence of an unidentified epidemic plasmid in these isolates is unlikely. Long-read sequencing-assisted hybrid assembly would be necessary to further test for this.

Notably, 11% of the sequenced 3GC-R isolates were from eight previously unknown STs, as might be expected given that this represents a relatively poorly surveyed region of the world. Likely for related reasons, we have identified mobilization of blaROB into E. coli from pigs and, in parallel, mobilization of a novel florfenicol resistance gene ydhC. Despite being detected in both our sampled regions and animal species, ROB has never before been reported in E. coli and has exclusively been seen in Pasterallaceae, including pathogenic strains from farm animals (28–30) as well as P. multocida (31) and Haemophilus influenzae (32) from humans, where it is believed to have been mobilized from the chromosomes of bacteria commonly found in pigs (33).

This cements the idea that pig pathogens and commensals are sources of de novo resistance gene mobilization into enteric bacteria with a wider potential for global distribution, as was demonstrated most strikingly with the discovery of the mobile colistin resistance gene mcr-1 (34). Indeed, in parallel with the movement of blaROB into E. coli, we also identified de novo mobilization of a novel florfenicol resistance gene ydhC from another pig (and avian) pathogen, R. anatipestifer, via an ISEc69 element, which has previously been associated with composite transposons mobilizing the colistin resistance gene, mcr-2, which also emerged in pigs (35). This highlights the importance of global resistome surveillance.

The ROB variant encoded in these porcine 3GC-R E. coli isolates was ROB-11, which has not formally been characterized before. This variant is one amino acid different from the penicillinase ROB-1 (Thr172Ala) and, while this difference is also shared by the reported expanded-spectrum cephalosporinase ROB-2 variant (Fig. S7) from Mannheimia haemolytica, the role of residue 172 is unclear, and other amino acid changes in ROB-2 are likely more relevant to this phenotype (36). Indeed, ROB-11 was only found in E. coli isolates alongside other 3GC-R mechanisms, so there is no reason to believe that this is a novel 3GC-R gene mobilization. So far, blaROB has not been identified in E. coli outside of our study.

In conclusion, we report a high prevalence of 3GC-R E. coli positivity at sample and farm level when collecting fecal samples from dairy and pig farms in Argentina. We identified diverse 3GC-R mechanisms, found on diverse mobile genetic elements, carried within a diverse range of E. coli STs. Limited evidence of farm-to-farm transmission suggests long-term circulation of 3GC-R in this region. Since the survey was carried out 1 year before the latest Argentinian law was enacted aiming to reduce AMR on Argentinian farms, these data set a baseline for 3GC-R prevalence and ecology on 70 pig and dairy farms, allowing ongoing surveillance of these farms to be used to measure any changes in AMR prevalence and ecology following recently implemented and future interventions.

Finally, we further demonstrate how farmed animals can form a nexus where resistance genes (in this case, blaROB and ydhC) can transfer from animal pathogens (with a limited impact on human health) into fecal coliforms with the ability to colonize a diverse range of hosts and environments, and with the potential to cause a significant burden of human disease. While global dissemination of these genes among E. coli is unlikely to substantially increase the AMR burden in humans or animals, this finding reminds us that future events of this type, as seen most importantly through the emergence of mcr-mediated colistin resistance, could adversely affect human and animal health. Identifying these emerging AMR threats is, therefore, another key reason for ongoing AMR surveillance on farms, particularly in under-studied regions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Farm sampling

A longitudinal survey of a convenience sample of dairy and pig farms was conducted over the Argentinian autumn and winter seasons of 2021. Farms were located in two regions of central-eastern Argentina, one around La Plata, Buenos Aires province and the other around Río Cuarto, Córdoba province. Requests for farms to enroll in the study were driven by each farm’s proximity to one of the two university microbiology laboratories along with previous farmer/veterinarian relationships with the two university veterinary schools undertaking sample collection. During the first visit to each farm, the farmers were informed about the objectives of the project and the number and types of samples to be taken. Then, all farmers gave fully informed consent to participate.

Among the pig farms selected, 11 were considered small by Argentine standards (<300 sows in production), 13 medium (301–700 sows), and 16 large (>700 sows). For the dairy farms, at the point of recruitment, 8 were considered small (<200 milking cows), 15 medium (200–500 cows), and 7 large (>500 cows). Each farm was visited once per season, and, at each visit, five samples were collected, returning to the same locations on the farm for each sampling visit. Samples represented a cross-section of sites and animal management stages within farms (Fig. S1). Three samples per visit were from fecally contaminated areas with high densities of animal traffic. For dairy farms, the sites sampled were the calf pen, heifer pen, and the waiting area (collecting yard) near the milking parlor. On four large dairy farms with two or three collecting yards, additional samples were taken from these areas. On pig farms, samples were taken from gestation, weaning (40 days old), and finishing (120 days old) areas. To collect the fecal samples, researchers walked around the areas forming an “X” path, wearing two polythene absorbent overshoes per collection site, which were both stored in a single sterile bag. In addition, for every farm, one sample of effluent outflow and one sample of animal drinking water were collected, in each case using 50 mL sterile polypropylene tubes. One multi-site pig farm had additional effluent and water samples taken from the second site. All samples were kept refrigerated and delivered to the laboratory within 24 h to be processed.

Sample processing and microbiology

No enrichment steps were used in this study. For the overshoe samples, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was added directly to the pair of used overshoes after they had been weighed (10 mL was added per gram) in their sterile bag, and the facal material was manually resuspended. Of this suspension, 1 mL was transferred to a sterile tube, which was centrifuged at 600 rpm for 2 min. The supernatant was diluted 1:200 with PBS, and 100 µL was spread onto CHROMagar Orientation containing 2 mg/L of cefotaxime to select for 3GC-R E. coli. For effluent samples, tubes were left to stand vertically for 30 min, or in some cases, centrifuged as above to reduce particulates, and then the supernatant was diluted and plated as above. Drinking water samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 3,000 rpm and 40 mL of the supernatant was removed; the remaining 10 mL was then used to resuspend any pellet present. Of this suspension, 100 µL was plated as above without dilution.

All plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C and colonies consistent in appearance with 3GC-R E. coli (if present) were picked and streaked onto an identical selective agar plate to confirm resistance and to facilitate isolate purification. One colony was picked per plate, though, rarely, if colonies had clearly different morphologies, up to two colonies were picked, one representing each colony type. Purified isolates were transferred to stab cultures (Luria-Bertani [LB] agar) and sent from Argentina to the United Kingdom by air freight, kept at ambient temperature. Upon receipt, isolates were recovered, when possible, and re-checked for resistance and purity using Tryptone Bile X-Glucuronide (TBX) agar plates containing 2 mg/L cefotaxime before PCR and WGS analysis.

PCR, WGS, and bioinformatics

Two multiplex PCR assays were used to characterize 3GC-R isolates as described previously (37). One identified the five known blaCTX-M groups, and the second identified common β-lactamase genes blaTEM, blaOXA-1, blaSHV, blaCMY-2, and blaDHA-1 (37). Furthermore, RAPD-PCR was used to discriminate between isolates as previously described (38). Isolates were selected for WGS using these PCR data, with multiple isolates from the same farm visit only being selected for sequencing if they produced different multiplex and/or RAPD-PCR profiles. The aim was to reduce the chances that identical isolates present on a farm would be sequenced since genome sequences were to be deduplicated at the farm level by reference to ST and resistance gene complement in order to reduce the impact of farm-level clustering.

WGS was performed by MicrobesNG to achieve a minimum 30-fold coverage. Confluent growth for an isolate on TBX agar containing cefotaxime (2 mg/L) was streaked using a loop into a tube containing 10 mL of PBS to create a stock suspension. Density was adjusted by serial dilution, and the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was measured from the dilution point where OD600 was <1. The density of the stock solution was then adjusted based on this measured OD600 to be equivalent to an OD600 of 8, and 1 mL of the stock solution was transferred to an Eppendorf and the bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation. The pellet was washed once in PBS and then resuspended in 500 µL of DNA/RNA Shield (Zymo Research) and shipped to MicrobesNG at ambient temperature.

Upon receipt, 5–40 µL of cell suspension was lysed with 120 µL of TE buffer containing lysozyme (0.1 mg/mL) and RNase A (0.1 mg/mL), by incubating for 25 min at 37°C. Proteinase K (0.1 mg/mL) and SDS (0.5%, vol/vol) were then added, followed by a further incubation for 5 min at 65°C. Genomic DNA was purified using an equal volume of solid-phase reversible immobilization beads and resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. DNA concentration was quantified with a Quant-iT dsDNA HS kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) assay in an Eppendorf AF2200 plate reader (Eppendorf UK Ltd, UK) and diluted as appropriate.

Genomic DNA libraries were prepared using the Nextera XT Library Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol with the following modifications: input DNA was increased twofold and PCR elongation time was increased to 45 s. DNA quantification and library preparation were carried out on a Hamilton Microlab STAR automated liquid handling system (Hamilton Bonaduz AG, Switzerland). Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina, San Diego, USA) using a 250 bp paired-end protocol.

Reads were adapter trimmed using Trimmomatic version 0.30 (39) with a sliding window quality cutoff of Q15. De novo assembly was performed on samples using SPAdes version 3.7 (40). Assembly quality control data are presented in Table S8. Contigs were annotated using Prokka 1.11 (41). Fasta files were analyzed using ResFinder 4.1, including pointfinder (42), MLST 2.0 (43), and, where relevant, PlasmidFinder 2.1 (44). The likely plasmid/chromosomal locations of resistance genes were determined using blastn of contig sequences using E. coli MG1655 to identify chromosomal loci and with no restriction to identify the closest circularized plasmid match. To map reads against this circularized plasmid fasta file as a reference, we used Burrows-Wheeler Alignment (45) on the Galaxy platform version 23.1 (https://usegalaxy.org/). Hyperexpression of blaTEM-1 genes was predicted using blastn alignments of upstream sequences (250 nt) to identify known mutations associated with increased promoter activity (7). Gene copy number was inferred using a bespoke read density analysis, mapping raw sequence reads to a blaTEM-1 database entry as a reference, normalizing read density to average chromosomal read density using the MG1655 genome as reference. Details of this approach are presented elsewhere (46).

Phylogenetics

Phylogenetic analysis was carried out using the Bioconda environment (47) on the Cloud Infrastructure for Microbial Bioinformatics (48). The reference genome was EC590 (accession number: NZ_CP016182). Sequence alignments were with Snippy (https://github.com/tseemann/snippy). Maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees were constructed using RAxML, utilizing the GTRCAT model of rate heterogeneity and the software’s autoMR and rapid bootstrap (49). Trees were illustrated using Microreact (50), and SNP distances were determined using SNP-dists (https://github.com/tseemann/snp-dists). Clones were defined as groups of isolates separated by <15 SNPs across the core genome alignment.

Statistical analysis

To estimate any differences in regional or species 3GC-R positivity rates, a binomial mixed-effects model was constructed in R, using the lme4 package (51). Preliminary univariable and bivariable analyses identified sample type as an important predictor of the likelihood of a sample testing positive, as well as that the detection of 3GC-R E. coli tended to be lower in cattle but not in pigs in Visit 2 compared with Visit 1. Likelihood ratio tests and the Akaike Information Criterion were used to compare different model structures and whether additional variables significantly improved model fits. In the final model, the farm of origin was fitted as a random effect, and fixed effects were the sample type (fecal, effluent, or water), region, animal species, and visit number, plus an interaction term between species and visit number.

To test associations between animal species (pigs or cattle) and the detection of individual 3GC-R mechanisms, Fisher’s exact tests were applied, using the data from sequenced isolates. Data were aggregated to give a single presence/absence score for each farm, with subsequent identification of the same mechanism in a different isolate being disregarded, even where sequence types differed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to all farmers and farm workers who facilitated access for sample collection and Federico Luna, formerly of Servicio Nacional de Sanidad y Calidad Agroalimentaria, for assistance with project design. Genome sequencing was provided by MicrobesNG (http://www.microbesng.com). We acknowledge the technical assistance of David Griffo, Victorio Fabio Nievas, and Walter Darío Nievas.

This research was co-funded by CONICET (Grant ref EX-2019-45545263-APN-GDCT#CONICET) and the UK Department of Health and Social Care as part of the Global antimicrobial resistance (AMR) Innovation Fund (grant ref BB/T004592/1). This is a UK aid programme that supports early-stage innovative research in underfunded areas of AMR research and development for the benefit of those in low- and middle-income countries, who bear the greatest burden of AMR. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the UK Department of Health and Social Care.

R.L.S., N.M., J.G., M.P.E., D.D., M.B.A., and K.K.R. conceived the study and obtained funding. C.S.A., C.Ba., and M.R.M. were involved in project management. O.M., L.M., J.P., M.P, L.V.A., F.A., A.B., D.B., A.C., M.C.I., L.G.C., D.G., M.J., M.F.L., L.V.M., M.J.M., N.M., and H.D.N. collected the data under the supervision of S.W., J.G., M.B.A., K.K.R., R.L.S., F.A.M., and N.M. O.M., L.M., J.P., M.P., C.Be., J.B., C.R., L.V. cleaned and analyzed the data under the supervision of S.W., R.L.S., N.M., F.A.M., J.G., M.B.A., and K.K.R. O.M. and M.B.A. initially drafted the manuscript. All authors corrected and approved the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Matthew B. Avison, Email: bimba@bris.ac.uk, matthewb.avison@bristol.ac.uk.

Charles M. Dozois, INRS Armand-Frappier Sante Biotechnologie Research Centre, Canada

DATA AVAILABILITY

Whole genome sequence data for the isolates reported in this study are deposited with the European Nucleotide Archive (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/) under project accession number PRJEB70722.

ETHICS APPROVAL

Ethical approval was obtained from the Central Bioethics Advisory Committee of the Universidad Nacional de La Plata (13 November 2019). It was also obtained from the University of Bristol for working with animals (VIN/19/019) and Human Ethics case 2019-7011 (ID no. 418938).

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.01791-23.

Supplementary Tables S1-S8 and Figures S1-S7.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Coppola N, Freire B, Umpiérrez A, Cordeiro NF, Ávila P, Trenchi G, Castro G, Casaux ML, Fraga M, Zunino P, Bado I, Vignoli R. 2020. Transferable resistance to highest priority critically important antibiotics for human health in Escherichia coli strains obtained from livestock Feces in Uruguay. Front Vet Sci 7:588919. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.588919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Palmeira JD, Haenni M, Metayer V, Madec JY, Ferreira HMN. 2020. Epidemic spread of Inci1/pST113 plasmid carrying the extended-spectrum beta-Lactamase (ESBL) blaCTX-M-8 gene in Escherichia coli of Brazilian cattle. Vet Microbiol 243:108629. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2020.108629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Faccone D, Moredo FA, Giacoboni GI, Albornoz E, Alarcón L, Nievas VF, Corso A. 2019. Multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli harbouring mcr-1 and blaCTX-M genes isolated from swine in Argentina. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 18:160–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2019.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Silva KC, Moreno M, Cabrera C, Spira B, Cerdeira L, Lincopan N, Moreno AM. 2016. First characterization of CTX-M-15-producing Escherichia coli strains belonging to sequence type (ST) 410, ST224, and ST1284 from commercial swine in South America. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:2505–2508. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02788-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Benavides JA, Godreuil S, Opazo-Capurro A, Mahamat OO, Falcon N, Oravcova K, Streicker DG, Shiva C. 2022. Long-term maintenance of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli carried by vampire bats and shared with livestock in Peru. Sci Total Environ 810:152045. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Benavides JA, Salgado-Caxito M, Opazo-Capurro A, González Muñoz P, Piñeiro A, Otto Medina M, Rivas L, Munita J, Millán J. 2021. ESBL-producing Escherichia coli carrying CTX-M genes circulating among livestock, dogs, and wild mammals in small-scale farms of Central Chile. Antibiotics (Basel) 10:510. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10050510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Davies TJ, Stoesser N, Sheppard AE, Abuoun M, Fowler P, Swann J, Quan TP, Griffiths D, Vaughan A, Morgan M, Phan HTT, Jeffery KJ, Andersson M, Ellington MJ, Ekelund O, Woodford N, Mathers AJ, Bonomo RA, Crook DW, Peto TEA, Anjum MF, Walker AS. 2020. Reconciling the potentially irreconcilable? genotypic and phenotypic Amoxicillin-Clavulanate resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 64:e02026-19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02026-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Poyet M, Groussin M, Gibbons SM, Avila-Pacheco J, Jiang X, Kearney SM, Perrotta AR, Berdy B, Zhao S, Lieberman TD, Swanson PK, Smith M, Roesemann S, Alexander JE, Rich SA, Livny J, Vlamakis H, Clish C, Bullock K, Deik A, Scott J, Pierce KA, Xavier RJ, Alm EJ. 2019. A library of human gut bacterial isolates paired with longitudinal multiomics data enables mechanistic microbiome research. Nat Med 25:1442–1452. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0559-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Arcangioli MA, Leroy-Sétrin S, Martel JL, Chaslus-Dancla E. 1999. A new chloramphenicol and florfenicol resistance gene flanked by two Integron structures in Salmonella typhimurium DT104. FEMS Microbiol Lett 174:327–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13586.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. López-Ochoa AJ, Sánchez-Alonso P, Vázquez-Cruz C, Horta-Valerdi G, Negrete-Abascal E, Vaca-Pacheco S, Mejía R, Pérez-Márquez M. 2019. Molecular and genetic characterization of the pOV Plasmid from Pasteurella multocida and construction of an integration vector for Gallibacterium anatis. Plasmid 103:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2019.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hayer SS, Casanova-Higes A, Paladino E, Elnekave E, Nault A, Johnson T, Bender J, Perez A, Alvarez J. 2022. Global distribution of extended spectrum cephalosporin and carbapenem resistance and associated resistance markers in Escherichia coli of swine origin - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Microbiol 13:853810. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.853810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Massé J, Lardé H, Fairbrother JM, Roy JP, Francoz D, Dufour S, Archambault M. 2021. Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance and characteristics of Escherichia coli isolates from fecal and manure pit samples on dairy farms in the province of Québec, Canada. Front Vet Sci 8:654125. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.654125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Turner A, Schubert H, Puddy EF, Sealey JE, Gould VC, Cogan TA, Avison MB, Reyher KK. 2022. Factors influencing the detection of antibacterial-resistant Escherichia coli in faecal samples from individual cattle. J Appl Microbiol 132:2633–2641. doi: 10.1111/jam.15419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kamaruzzaman EA, Abdul Aziz S, Bitrus AA, Zakaria Z, Hassan L. 2020. Occurrence and characteristics of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli from dairy cattle, milk, and farm environments in Peninsular Malaysia. Pathogens 9:1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schubert H, Morley K, Puddy EF, Arbon R, Findlay J, Mounsey O, Gould VC, Vass L, Evans M, Rees GM, Barrett DC, Turner KM, Cogan TA, Avison MB, Reyher KK. 2021. Reduced antibacterial drug resistance and BLACTX-M β-lactamase gene carriage in cattle-associated Escherichia coli at low temperatures. Appl Environ Microbiol 87:e01468-20. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01468-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Homeier-Bachmann T, Kleist JF, Schütz AK, Bachmann L. 2022. Distribution of ESBL/AmpC-Escherichia coli on a dairy farm. Antibiotics (Basel) 11:940. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11070940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tello M, Ocejo M, Oporto B, Hurtado A. 2020. Prevalence of cefotaxime-resistant Escherichia coli isolates from healthy cattle and sheep in northern Spain: phenotypic and genome-based characterization of antimicrobial susceptibility. Appl Environ Microbiol 86:e00742-20. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00742-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wei X, Wang W, Lu N, Wu L, Dong Z, Li B, Zhou X, Cheng F, Zhou K, Cheng H, Shi H, Zhang J. 2022. Prevalence of multidrug-resistant CTX-M extended spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli from different bovine Faeces in China. Front Vet Sci 9. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.738904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Song J, Oh SS, Kim J, Park S, Shin J. 2020. Clinically relevant extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli isolates from food animals in South Korea. Front Microbiol 11:604. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Song HJ, Moon DC, Kim SJ, Mechesso AF, Choi JH, Boby N, Kang HY, Na SH, Yoon SS, Lim SK. 2023. Antimicrobial resistance profiles and molecular characteristics of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli isolated from healthy cattle and pigs in Korea. Foodborne Pathog Dis 20:7–16. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2022.0051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu Z, Wang K, Zhang Y, Xia L, Zhao L, Guo C, Liu X, Qin L, Hao Z. 2022. High prevalence and diversity characteristics of blaNDM, mcr, and blaESBLs harboring multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli from chicken, pig, and cattle in China. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol 11:755545. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.755545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. González Pereyra V, Pol M, Pastorino F, Herrero A. 2015. Quantification of antimicrobial usage in dairy cows and preweaned calves in Argentina. Prev Vet Med 122:273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2015.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Giufrè M, Mazzolini E, Cerquetti M, Brusaferro S, CCM2015 One-Health ESBL-producing Escherichia coli Study Group . 2021. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli from extraintestinal infections in humans and from food-producing animals in Italy: a 'one health' study. Int J Antimicrob Agents 58:106433. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2021.106433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cormier A, Zhang PLC, Chalmers G, Weese JS, Deckert A, Mulvey M, McAllister T, Boerlin P. 2019. Diversity of CTX-M-positive Escherichia coli recovered from animals in Canada. Vet Microbiol 231:71–75. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2019.02.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. D’Andrea MM, Arena F, Pallecchi L, Rossolini GM. 2013. CTX-M-type β-Lactamases: a successful story of antibiotic resistance. Int J Med Microbiol 303:305–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Findlay J, Mounsey O, Lee WWY, Newbold N, Morley K, Schubert H, Gould VC, Cogan TA, Reyher KK, Avison MB. 2020. Molecular epidemiology of Escherichia coli producing CTX-M and pAmpC β-lactamases from dairy farms identifies a dominant plasmid encoding CTX-M-32 but no evidence for transmission to humans in the same geographical region. Appl Environ Microbiol 87:e01842-20. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01842-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Alzayn M, Findlay J, Schubert H, Mounsey O, Gould VC, Heesom KJ, Turner KM, Barrett DC, Reyher KK, Avison MB. 2020. Characterization of AmpC-hyperproducing Escherichia coli from humans and dairy farms collected in parallel in the same geographical region. J Antimicrob Chemother 75:2471–2479. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Juteau JM, Sirois M, Medeiros AA, Levesque RC. 1991. Molecular distribution of ROB-1 beta-lactamase in Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 35:1397–1402. doi: 10.1128/AAC.35.7.1397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. San Millan A, Escudero JA, Catalan A, Nieto S, Farelo F, Gibert M, Moreno MA, Dominguez L, Gonzalez-Zorn B. 2007. Beta-lactam resistance in Haemophilus parasuis is mediated by plasmid pB1000 bearing blaROB-1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:2260–2264. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00242-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yang SS, Sun J, Liao XP, Liu BT, Li LL, Li L, Fang LX, Huang T, Liu YH. 2013. Co-location of the erm(T) gene and blaROB-1 gene on a small plasmid in Haemophilus parasuis of pig origin. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:1930–1932. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rosenau A, Labigne A, Escande F, Courcoux P, Philippon A. 1991. Plasmid-mediated ROB-1 beta-lactamase in Pasteurella multocida from a human specimen. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 35:2419–2422. doi: 10.1128/AAC.35.11.2419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Farrell DJ, Morrissey I, Bakker S, Buckridge S, Felmingham D. 2005. Global distribution of TEM-1 and ROB-1 beta-lactamases in Haemophilus influenzae. J Antimicrob Chemother 56:773–776. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Medeiros AA, Levesque R, Jacoby GA. 1986. An animal source for the ROB-1 beta-lactamase of Haemophilus influenzae type B. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 29:212–215. doi: 10.1128/AAC.29.2.212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR, Yi LX, Zhang R, Spencer J, Doi Y, Tian G, Dong B, Huang X, Yu LF, Gu D, Ren H, Chen X, Lv L, He D, Zhou H, Liang Z, Liu JH, Shen J. 2016. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis 16:161–168. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. He YZ, Long TF, He B, Li XP, Li G, Chen L, Liao XP, Liu YH, Sun J. 2021. ISEc69-mediated mobilization of the colistin resistance gene mcr-2 in Escherichia coli. Front. Microbiol 11:564973. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.564973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kadlec K, Watts JL, Schwarz S, Sweeney MT. 2019. Plasmid-located extended-spectrum β-lactamase gene blaROB-2 in Mannheimia haemolytica. J Antimicrob Chemother 74:851–853. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Findlay J, Gould VC, North P, Bowker KE, Williams MO, MacGowan AP, Avison MB. 2020. Characterization of cefotaxime-resistant urinary Escherichia coli from primary care in South-West England 2017-18. J Antimicrob Chemother 75:65–71. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Avison MB, Underwood S, Okazaki A, Walsh TR, Bennett PM. 2004. Analysis of AmpC beta-lactamase expression and sequence in biochemically atypical ceftazidime-resistant Enterobacteriaceae from paediatric patients. J Antimicrob Chemother 53:584–591. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, Lesin VM, Nikolenko SI, Pham S, Prjibelski AD, Pyshkin AV, Sirotkin AV, Vyahhi N, Tesler G, Alekseyev MA, Pevzner PA. 2012. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol 19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Seemann T. 2014. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bortolaia V, Kaas RS, Ruppe E, Roberts MC, Schwarz S, Cattoir V, Philippon A, Allesoe RL, Rebelo AR, Florensa AF, et al. 2020. ResFinder 4.0 for predictions of phenotypes from genotypes. J Antimicrob Chemother 75:3491–3500. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Larsen MV, Cosentino S, Rasmussen S, Friis C, Hasman H, Marvig RL, Jelsbak L, Sicheritz-Pontén T, Ussery DW, Aarestrup FM, Lund O. 2012. Multilocus sequence typing of total-genome-sequenced bacteria. J Clin Microbiol 50:1355–1361. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06094-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Carattoli A, Zankari E, García-Fernández A, Voldby Larsen M, Lund O, Villa L, Møller Aarestrup F, Hasman H. 2014. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:3895–3903. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02412-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Li H, Durbin R. 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with burrows-wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Reding C, Satapoomin N, Avison MB. 2023. Hound: a novel tool for automated mapping of genotype to phenotype in bacterial genomes assembled de novo. Genomics. doi: 10.1101/2023.09.15.557405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47. Grüning B, Dale R, Sjödin A, Chapman BA, Rowe J, Tomkins-Tinch CH, Valieris R, Köster J, Bioconda Team . 2018. Bioconda: sustainable and comprehensive software distribution for the life sciences. Nat Methods 15:475–476. doi: 10.1038/s41592-018-0046-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Connor TR, Loman NJ, Thompson S, Smith A, Southgate J, Poplawski R, Bull MJ, Richardson E, Ismail M, Thompson SE, Kitchen C, Guest M, Bakke M, Sheppard SK, Pallen MJ. 2016. CLIMB (the Cloud Infrastructure for Microbial Bioinformatics): an online resource for the medical microbiology community. Microb Genom 2:e000086. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Stamatakis A. 2006. RaxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22:2688–2690. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Argimón S, Abudahab K, Goater RJE, Fedosejev A, Bhai J, Glasner C, Feil EJ, Holden MTG, Yeats CA, Grundmann H, Spratt BG, Aanensen DM. 2016. Microreact: visualizing and sharing data for genomic epidemiology and phylogeography. Microb Genom 2:e000093. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using Lme4. J Stat Soft 67:1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Tables S1-S8 and Figures S1-S7.

Data Availability Statement

Whole genome sequence data for the isolates reported in this study are deposited with the European Nucleotide Archive (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/) under project accession number PRJEB70722.