ABSTRACT

Galacto-N-biose (GNB) is an important core structure of glycan of mucin glycoproteins in the gastrointestinal (GI) mucosa. Because certain beneficial bacteria inhabiting the GI tract, such as bifidobacteria and lactic acid bacteria, harbor highly specialized GNB metabolic capabilities, GNB is considered a promising prebiotic for nourishing and manipulating beneficial bacteria in the GI tract. However, the precise interactions between GNB and beneficial bacteria and their accompanying health-promoting effects remain elusive. First, we evaluated the proliferative tendency of beneficial bacteria and their production of beneficial metabolites using gut bacterial strains. By comparing the use of GNB, glucose, and inulin as carbon sources, we found that GNB enhanced acetate production in Lacticaseibacillus casei, Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus, Lactobacillus gasseri, and Lactobacillus johnsonii. The ability of GNB to promote acetate production was also confirmed by RNA-seq analysis, which indicated the upregulation of gene clusters that catalyze the deacetylation of N-acetylgalactosamine-6P and biosynthesize acetyl-CoA from pyruvate, both of which result in acetate production. To explore the in vivo effect of GNB in promoting acetate production, antibiotic-treated BALB/cA mice were administered with GNB with L. rhamnosus, resulting in a fecal acetate content that was 2.7-fold higher than that in mice administered with only L. rhamnosus. Moreover, 2 days after the last administration, a 3.7-fold higher amount of L. rhamnosus was detected in feces administered with GNB with L. rhamnosus than in feces administered with only L. rhamnosus. These findings strongly suggest the prebiotic potential of GNB in enhancing L. rhamnosus colonization and converting L. rhamnosus into higher acetate producers in the GI tract.

IMPORTANCE

Specific members of lactic acid bacteria, which are commonly used as probiotics, possess therapeutic properties that are vital for human health enhancement by producing immunomodulatory metabolites such as exopolysaccharides, short-chain fatty acids, and bacteriocins. The long residence time of probiotic lactic acid bacteria in the GI tract prolongs their beneficial health effects. Moreover, the colonization property is also desirable for the application of probiotics in mucosal vaccination to provoke a local immune response. In this study, we found that GNB could enhance the beneficial properties of intestinal lactic acid bacteria that inhabit the human GI tract, stimulating acetate production and promoting intestinal colonization. Our findings provide a rationale for the addition of GNB to lactic acid bacteria-based functional foods. This has also led to the development of therapeutics supported by more rational prebiotic and probiotic selection, leading to an improved healthy lifestyle for humans.

KEYWORDS: galacto-N-biose, prebiotic, lactic acid bacteria, acetate, probiotics, Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus, intestinal colonization, GNB

INTRODUCTION

Species of bifidobacteria (members of the genus Bifidobacterium) and lactic acid bacteria (LAB, members of the phylum Firmicutes and order Lactobacillales) are often used as probiotics, which are defined as “live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host” (1, 2). Probiotics and their metabolites have been demonstrated to improve host health by maintaining the metabolic balance in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and regulating immune responses to prevent or treat diseases (3–6). In particular, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), mainly composed of acetate, propionate, and butyrate, are metabolites produced by probiotics and have yielded promising results in terms of decreasing the incidence of obesity, diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, and allergic inflammation (7–10). However, given the results of human and animal studies showing that exogenously administered probiotics pass through the GI tract without adhering, administration of probiotics at regular intervals is required to obtain a sustained effect (11–13).

Prebiotics are non-digestible food ingredients that benefit the host by selectively stimulating the proliferation, survival, and activity of a limited number of probiotics in the GI tract (14–16). Thus, combining prebiotics and probiotics can enhance their beneficial properties (15).

Galacto-N-biose (GNB, Galβ1–3GalNAc) is a common O-glycan core structure in glycoproteins, such as mucin, present in the human GI tract (17, 18). Bifidobacteria and LAB that inhabit the human GI tract harbor a mucin O-glycan-exploiting system that adapts to the limited carbohydrate resources present in the GI niche. Bifidobacterial species transport extracellular GNB into the cell using an ATP-binding cassette transporter specialized for GNB and lacto-N-biose (Galβ1–3GlcNAc, the main core structure of human milk oligosaccharides) and phosphorolytically cleave GNB by GNB/lacto-N-biose phosphorylase (19, 20), whereas LAB species use phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase system (PTS) to transport GNB, and the resulting phosphorylated GNB is cleaved by phospho-β-galactosidase (21). Because β1,3-linked galactose is highly resistant to human digestive enzymes and typical enterobacterial β-galactosidases (22), GNB is non-digestible in the GI tract and is assumed to be an ideal prebiotic for the selective proliferation of probiotics.

In this study, we evaluated the prebiotic capacity of GNB in vitro by analyzing the proliferation and productivity of SCFAs using gut bacterial strains, revealing that GNB enhanced the acetate-producing metabolic pathway of some gut LAB strains. Using Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus JCM1136T, which showed the highest acetate productivity among the strains, the acetate-increasing effect of GNB was also confirmed in vivo by analyzing SCFA concentrations in the feces of mice administered with L. rhamnosus JCM1136T with GNB. The in vivo results also showed that GNB enhanced L. rhamnosus JCM1136T colonization in the intestine. These prebiotic properties of GNB for intestinally beneficial LAB, which are potentially probiotic bacteria, to colonize and enhance acetate production, were also supported by RNA-seq analysis of JCM1136T cells cultured in a medium containing GNB.

RESULTS

GNB changed the metabolite profile of lactic acid bacteria to promote acetic acid production

To investigate the beneficial effects of GNB on the human gut microbiota, we cultured strains of human gut bacteria including 11 species of bifidobacteria, 14 species of LAB, and 21 species of other bacteria (Table 1) in Gifu anaerobic medium (GAM) without sugar (woC medium) supplemented with GNB (GNB medium). Growth and metabolite production were examined using woC medium as a negative control and that supplemented with glucose (Glc medium) as a positive control.

TABLE 1.

List of human enterobacterial species used in this study

| Species | JCM | Referencea |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron | JCM5827 | 23 |

| Bacteroides xylanisolvens | JCM15633 | 23 |

| Bacteroides ovatus | JCM5824 | 23 |

| Bacteroides caccae | JCM9498 | 23 |

| Bacteroides intestinalis | JCM13265 | 23 |

| Bacteroides stercoris | JCM9496 | 23 |

| Bacteroides uniformis | JCM5828 | 23 |

| Bacteroides vulgatus | JCM5826 | 23 |

| Bacteroides dorei | JCM13471 | 23 |

| Parabacteroides distasonis | JCM5825 | 23 |

| Parabacteroides merdae | JCM9497 | 23 |

| Parabacteroides johnsonii | JCM13406 | 23 |

| Akkermansia muciniphila | JCM30893 | 24 |

| Bifidobacterium adolescentis | JCM1275 | 25, 26 |

| Bifidobacterium dentium | JCM1195 | 25, 26 |

| Bifidobacterium angulatum | JCM7096 | 26 |

| Bifidobacterium catenulatum | JCM1194 | 27 |

| Bifidobacterium bifidum | JCM1255 | 25, 26 |

| Bifidobacterium breve | JCM1192 | 25, 26 |

| Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis | JCM1222 | 26 |

| Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum | JCM1217 | 26 |

| Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis | JCM10602 | 25 |

| Bifidobacterium pseudolongum subsp. pseudolongum | JCM1205 | 28 |

| Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum | JCM1205 | 26 |

| Collinsella aerofaciens | JCM10188 | 29 |

| Clostridium nexile | JCM31500 | 23 |

| Blautia hansenii | JCM14655 | 23 |

| Blautia coccoides | JCM1395 | 30 |

| Anaerotruncus colihominis | JCM15631 | 23 |

| Eubacterium limosum | JCM6421 | 31 |

| Clostridium ramosum | JCM1298 | 32 |

| Clostridium cocleatum | JCM1397 | 33 |

| Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. mesenteroides | JCM6124 | 34 |

| Streptococcus thermophilus | JCM17834 | 23 |

| Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis | JCM5805 | 35 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | JCM5803 | 23 |

| Lactobacillus crispatus | JCM1185 | 36, 37 |

| Lactobacillus johnsonii | JCM2012 | 38 |

| Lactobacillus gasseri | JCM1131 | 36, 37 |

| Limosilactobacillus reuteri | JCM1112 | 36 |

| Limosilactobacillus fermentum | JCM1173 | 36 |

| Lactiplantibacillus plantarum subsp. plantarum | JCM1149 | 36, 37 |

| Ligilactobacillus salivarius | JCM1231 | 36 |

| Lacticaseibacillus casei | JCM1134 | 36, 37 |

| Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus | JCM1136 | 36 |

| Lacticaseibacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei | JCM8130 | 36, 37 |

References in which each bacterial species was detected in human feces or intestines.

As shown in Fig. 1A, among the 46 species of gut bacteria that could grow in the positive control medium (Glc medium), seven species of bifidobacteria (Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum, Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis, Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Bifidobacterium angulatum, Bifidobacterium dentium, and Bifidobacterium pseudolongum subsp. pseudolongum) and seven species of LAB (Ligilactobacillus salivarius, Lacticaseibacillus casei, Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus, Lactobacillus gasseri, Lactobacillus johnsonii, Limosilactobacillus fermentum, and Enterococcus faecalis) were found to grow on GNB medium better than on woC medium. In most species, the increase in SCFA (acetate, propionate, and butyrate) production in the culture supernatants was accompanied by bacterial growth; however, there were some exceptions among the LAB species, L. rhamnosus, L. casei, L. johnsonii, and L. gasseri. The growth of these LAB species was promoted in both the GNB and Glc media, but the acetate production increased only in the GNB medium (Fig. 1B). The acetate concentrations in the GNB medium cultured with L. rhamnosus, L. casei, L. gasseri, or L. johnsonii were 13.9, 10.4, 8.6, and 10.2 mM, which were 3.9-, 2.7-, 2.9-, and 2.2-fold higher, respectively, than those in the Glc medium (Fig. 2). Phylogenetic tree analysis indicated an increase in acetate production, particularly among the species of the genera Lacticaseibacillus and Lactobacillus.

Fig 1.

Gut bacterial growth (A) and SCFA production (B) in the GNB medium. Gut bacterial species were cultured in woC medium (negative control), Glc medium (positive control), or GNB medium for 2 days. To evaluate the growth ability of each bacterium for GNB, the value of the OD600 ratio was obtained by dividing the average of growth (OD600) in the GNB medium or the Glc medium by that of the woC medium (n = 3). Data represent means ± standard deviation.

Fig 2.

Acetate production by gut bacteria in GNB and inulin media. The value of the acetate production ratio was obtained by dividing the average of acetate contents in the GNB or inulin medium by that of the Glc medium (n = 3). Values greater than 2 were indicated in the heat map cells. The phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences was constructed by MEGA X using the neighbor-joining method. Percentages of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1,000 replicates) are shown next to the branches.

Next, we compared the acetate-increasing effect of GNB with inulin, a commercially available prebiotic. We cultured strains of human gut bacteria in inulin medium (woC medium supplemented with inulin) and analyzed their growth and SCFA production (Fig. S1). WoC- and Glc-media were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. Inulin promoted the growth of four species of bifidobacteria (Fig. S1A) but did not promote acetate production compared with glucose (Fig. 2; Fig. S1B).

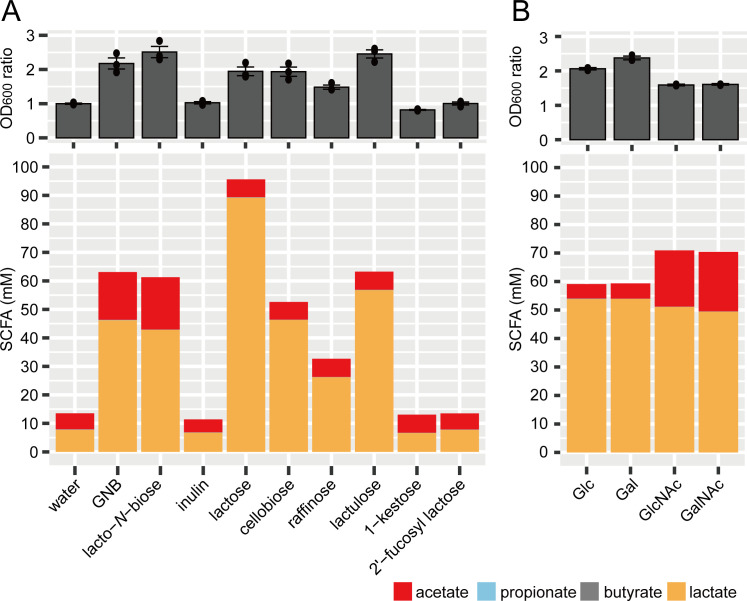

Only N-acetylated amino sugar-containing prebiotics promote acetate production by lactic acid bacteria

To determine whether the acetate-increasing effects of these LAB species (L. rhamnosus, L. casei, L. gasseri, and L. johnsonii) are GNB specific, cell growth and metabolites (SCFAs, lactate, and ethanol) were compared across different prebiotics. L. rhamnosus, which possessed the highest acetate productivity (Fig. 2), was cultured in medium supplemented with nine different prebiotics, including GNB. These were inulin, lactose (Galβ1–4Glc), cellobiose (Glcβ1–4Glc), raffinose (Galα1–6Glcα1–2βFru), lactulose (Galβ1–4Fru), 1-kestose (Glcα1–2βFru1-2βFru) (39, 40), 2′-fucosyllactose (Fucα1–2Galβ1–4Glc) (41), and lacto-N-biose (Galβ1–3GlcNAc) (42, 43), and water used as a negative control. These prebiotics are resistant to human intestinal digestive enzymes due to their glycosidic linkages. Since ethanol was not detected in any of the supernatants, the results for SCFAs and lactate are shown in Fig. 3A. Only GNB and lacto-N-biose promoted acetate production by L. rhamnosus. To identify the sugar components that affect the increase of acetate production by L. rhamnosus, the metabolites from sugars, which generate GNB and lacto-N-biose, were also analyzed. As shown in Fig. 3B, N-acetylated amino sugars, such as N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc), promoted acetate production by L. rhamnosus. Because N-acetylate amino sugars are absorbed in the intestinal tract (44), they do not contribute to the proliferation of beneficial bacteria in the intestine. Hence, both the N-acetylated sugar configuration and the non-digestible glycosidic linkage of GNB could be crucial for prebiotic use, enhancing acetate production by L. rhamnosus.

Fig 3.

Cell growth and SCFA production by L. rhamnosus JCM1136T in the culture supernatant supplemented with prebiotics (A) and monosaccharides (B). Gal, galactose; GalNAc, N-acetylgalactosamine; Glc, glucose; GlcNAc, N-acetyl-glucosamine; GNB, galacto-N-biose. The OD600 value of the culture and the SCFA concentrations of the culture supernatant were measured. Data represent means ± standard deviation (n = 3).

RNA-seq analysis

To identify the genes that contribute to acetate production by L. rhamnosus, we performed RNA-seq analysis. To examine the transcriptional changes associated with the acetate-increasing effect, bacterial cells cultured in medium supplemented with GNB or GalNAc, which were both positive carbon sources for the acetate-increasing effect, were compared with those cultured in medium supplemented with glucose or galactose (negative carbon sources for the acetate-increasing effect).

Before undertaking the RNA-seq, we cultured L. rhamnosus in woC medium, Glc medium, GNB medium, GalNAc medium (woC medium supplemented with GalNAc), or Gal medium (woC medium supplemented with galactose) and analyzed the bacterial growth (OD600) and SCFA productions between 0 and 48 h (Fig. S2). This revealed that acetate was extensively produced in the GNB and GalNAc media at approximately OD600 = 0.3. Hence, growing cells (50 mL) were harvested at an OD600 = 0.3 for use in the RNA-seq analysis.

Paired-end reads were initially mapped to the L. rhamnosus JCM1136T reference genome (accession number AZCQ01000000). Between 21.2 × 106 (GNB), 25.85 × 106 (GalNAc), 27.75 × 106 (galactose), and 19.2 × 106 (glucose) reads were mapped to the reference genome, providing genome coverage of 92.8% (GNB), 95.7% (GalNAc), 96.12% (galactose), and 94.5% (glucose). The average sequence coverage for each open reading frame (ORF) was 11,506 (GNB), 4,500 (GalNAc), 6,110 (galactose), and 12,381 (glucose). Gene expression was normalized by calculating the reads per kilobase per million mapped reads (RPKM) values for each ORF, and the ORFs were ranked by RPKM values to ascertain which genes were highly or weakly expressed under each growth condition. To identify genes associated with the acetate-increasing effect, we performed a volcano plot analysis (Fig. 4) and screened genes for which the mRNA levels were upregulated in GNB and GalNAc media (Z-score >1.5, P value < 0.01) and not upregulated in Gal medium (Z-score <0.5) compared with the mRNA levels in Glc medium. As shown in Table 2 and Fig. 4, 13 upregulated genes appeared to be associated with the acetate-increasing effect. When analyzing the L. rhamnosus JCM1136T genomic regions around these genes, we found that six gene clusters were upregulated: clusters A–F (Table 2; Fig. 5). We annotated the enzymes in these clusters and predicted their metabolic pathways using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes database resource (45). Cluster A contained genes involved in starch metabolism from UDP-glucose, a metabolite of amino sugars. An increased GalNAc supply is supposed to induce the upregulation of cluster A gene expressions. When GNB was metabolized, the genes involved in cluster B to convert pyruvate to acetyl-CoA were upregulated (the Z-scores of dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase, dihydrolipoyllysine-residue acetyltransferase, pyruvate dehydrogenase subunit beta, and pyruvate dehydrogenase subunit alpha were 1.949, 1.417, 0.976, and 0.405, respectively), whereas the expression of a gene that converts pyruvate to lactic acid (L-lactate dehydrogenase) was downregulated (locus tag: RS04355, Z-score = −1.259). Cluster D contained genes encoding GNB transporter (PTS components IIB, IIC, IID, and IIA) and genes involved in the metabolism of GNB to acetate and sugar molecules (GntR family transcriptional regulator, phosphosugar isomerase, N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate deacetylase, and phospho-β-galactosidase) (21). The released acetyl residues may have contributed to an increase in acetate production. Cluster C contained genes encoding PTS components and N-acetylmuramic acid 6-phosphate etherase, which has been reported to be an N-acetylmuramic acid transport system (46, 47). Cluster E contained PTS component genes to transport sorbitol (RS13100, RS13105, RS13110, RS13115, RS13120, and RS13125) and genes related to cell wall protein with serine-rich repeating domain (RS13130, RS13135, and RS13140). Cluster F also contained genes related to cell wall protein with the serine-rich repeating domain (RS13565 and RS13570).

Fig 4.

Volcano plot comparing the RNA expression profiles in GNB-, GalNAc-, and Gal media with that of the Glc medium. Z-scores are converted from log2 fold changes of gene expression. Gal, galactose; GalNAc, N-acetylgalactosamine; Glc, glucose; GNB, galacto-N-biose.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of gene expression levels measured by RNA-seq analysis of cells grown in GNB medium, GalNAc medium, and Gal mediuma

| Cluster | Locus tagb | Genbank_ID | Gene | Predicted function | Gal | GalNAc | GNB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z-score | Z-score | Z-score | |||||

| A | RS03070 | WP_015764582.1 | glgB | 1,4-Alpha-glucan branching protein GlgB | 0.256 | 1.314 | 0.646 |

| A | RS03075* | WP_005687169.1 | Glucose-1-phosphate adenylyltransferase | 0.111 | 1.723 | 1.541 | |

| A | RS03080* | NA | glgD | Glucose-1-phosphate adenylyltransferase subunit GlgD | −0.035 | 1.482 | 1.737 |

| A | RS03085* | WP_005692826.1 | glgA | Glycogen synthase GlgA | −0.125 | 1.01 | 1.545 |

| A | RS03090 | WP_019728285.1 | Glycogen/starch/alpha-glucan phosphorylase | 0.034 | 0.457 | 1.106 | |

| A | RS03095 | WP_005692830.1 | Glycoside hydrolase family 13 protein | 0.128 | 0.426 | 0.982 | |

| B | RS04750* | WP_005689192.1 | lpdA | Dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase | 0.47 | 1.549 | 1.949 |

| B | RS04755 | WP_015764445.1 | Dihydrolipoyllysine-residue acetyltransferase | 0.944 | 1.797 | 1.417 | |

| B | RS04760 | WP_005689188.1 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase subunit beta | 1.289 | 1.872 | 0.976 | |

| B | RS04765 | WP_005685622.1 | pdhA | Pyruvate dehydrogenase (acetyl-transferring) E1 component subunit alpha | 1.096 | 1.499 | 0.405 |

| B | RS04770 | WP_005689186.1 | ATPase | −0.383 | 0.176 | 0.675 | |

| C | RS07800 | WP_005690692.1 | PTS sugar transporter subunit IIC | −0.465 | 2.318 | 1.407 | |

| C | RS07805* | WP_005690694.1 | PTS system mannose/fructose/sorbose family transporter subunit IID | −0.535 | 2.293 | 1.705 | |

| C | RS07810* | WP_005690696.1 | PTS sugar transporter subunit IIB | −0.574 | 1.991 | 2.228 | |

| C | RS07815* | WP_005690698.1 | MurR/RpiR family transcriptional regulator | −0.363 | 1.572 | 2.191 | |

| C | RS07820 | WP_015764772.1 | murQ | N-acetylmuramic acid 6-phosphate etherase | −0.539 | 1.356 | 1.988 |

| C | RS07825* | WP_005690702.1 | Serine hydrolase | −0.482 | 1.187 | 1.79 | |

| C | RS07830 | WP_005690704.1 | Serine hydrolase | −0.469 | 0.467 | 1.315 | |

| D | RS11890* | WP_019728333.1 | GntR family transcriptional regulator | 0.33 | 3.566 | 2.386 | |

| D | RS11895* | WP_005687616.1 | Phosphosugar isomerase | 0.368 | 3.728 | 2.446 | |

| D | RS11900* | WP_005687614.1 | nagA | N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate deacetylase | 0.407 | 3.775 | 2.598 |

| D | RS11905 | WP_014571082.1 | Phospho-beta-galactosidase | −0.311 | 2.096 | 1.038 | |

| D | RS11910 | WP_005687609.1 | PTS sugar transporter subunit IIB | 0.023 | 2.226 | 0.766 | |

| D | RS11915 | WP_005687608.1 | PTS sugar transporter subunit IIC | 0.062 | 2.385 | 0.698 | |

| D | RS11920 | WP_005691352.1 | PTS system mannose/fructose/sorbose family transporter subunit IID | 0.074 | 2.314 | 0.93 | |

| D | RS11925 | WP_005691354.1 | PTS sugar transporter subunit IIA | 0.067 | 2.085 | 1.225 | |

| E | RS13095 | WP_005690785.1 | Transaldolase | 2.508 | 3.353 | 2.343 | |

| E | RS13100 | WP_005714186.1 | PTS glucitol/sorbitol transporter subunit IIA | 2.479 | 3.487 | 2.089 | |

| E | RS13105 | WP_005690782.1 | PTS glucitol/sorbitol transporter subunit IIB | 2.511 | 3.662 | 2.258 | |

| E | RS13110 | WP_005687747.1 | PTS glucitol/sorbitol transporter subunit IIC | 2.85 | 3.98 | 2.375 | |

| E | RS13115 | WP_005690780.1 | Transcriptional regulator GutM | 2.802 | 3.996 | 2.315 | |

| E | RS13120 | WP_014571687.1 | HTH domain-containing protein | 3.472 | 4.523 | 2.281 | |

| E | RS13125 | WP_005690776.1 | Sorbitol-6-phosphate 2-dehydrogenase | 3.688 | 4.985 | 2.105 | |

| E | RS13130 | WP_220094871.1 | Cell wall protein with serine-rich repeat domain | 0.346 | 1.629 | 2.432 | |

| E | RS13135 | WP_015764686.1 | Glycosyltransferase | 1.272 | 1.802 | 2.665 | |

| E | RS13140 | WP_014571544.1 | Glycosyltransferase | 1.117 | 1.517 | 2.276 | |

| E | RS13145 | WP_005692417.1 | NAD-dependent succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase | 1.425 | 1.923 | 1.701 | |

| F | RS13565 | WP_155519883.1 | LPXTG cell wall anchor domain-containing protein | 0.074 | 1.193 | 2.266 | |

| F | RS13570* | WP_019728467.1 | Glycosyl transferase | 0.187 | 1.545 | 1.903 |

Fold changes against cells grown in the Glc medium were translated to Z-scores.

Locus tag identifier from the L. rhamnosus JCM 1136T genome sequence (AZCQ01000000). *Astarisks beside the locus tag numbers indicate 13 genes found by volcano plot analysis (FIG 4).

Fig 5.

Map of the genomic regions around the 13 genes found by volcano plot analysis. Locus tags (in the arrows) and Z-scores of he GNB-supplemented medium (heat map of the arrows) of the genes are indicated. Asterisks (*) beside the locus tag numbers indicate 13 genes found by volcano plot analysis. Gene names and predicted functions of the genes are listed in Table 2.

GNB promoted acetate production of intestinal lactic acid bacteria and prolonged residence time in intestine

To investigate the acetate-increasing effect of GNB in vivo, antibiotic-treated mice were orally administered 1 × 109L. rhamnosus cells (L. rhamnosus group), 1 × 109L. rhamnosus cells, and 50 mg of GNB (L. rhamnosus + GNB group), or saline (control group) once every other day for three times, and metabolite (lactate, acetate, propionate, and butyrate) concentrations along with bacterial counts in feces were measured (Fig. 6A). No significant differences were found in body weight gain or food and water intakes between the groups (Table S1). Similarly, no significant differences were found in plasma aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, which reflect liver dysfunction, or creatinine (CRE) levels, which reflect renal dysfunction (Table S1). Comparison of the metabolite concentrations in the feces on day 5 (Fig. 6B) revealed that the acetate concentration in the L. rhamnosus + GNB group mice was significantly increased (2.5-fold, P = 0.015, vs the control group, and 2.7-fold, P = 0.016, vs the L. rhamnosus group). Note that the acetate concentration in the feces of the L. rhamnosus group was comparable to that of the control group, whereas the lactate concentration increased (P = 0.016), indicating that L. rhamnosus cells in the intestines of the L. rhamnosus group of mice were viable but could not produce acetate.

Fig 6.

Effect of GNB in mice administered L. rhamnosus. (A) Experimental outline. BALB/cA mice were orally administered 1 × 109 L. rhamnosus cells (L. rhamnosus group), 1 × 109 L. rhamnosus cells, and 50 mg of GNB (L. rhamnosus + GNB group), or saline (control group). Gray arrows indicate the timing of GNB or L. rhamnosus administration. (B) Metabolite concentrations in feces on day 5. (C) Number of total bacteria and L. rhamnosus in feces quantified by quantitative PCR. One-way analysis of variance with Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test was used. The data represent means ± standard deviation. Individual data points are represented by symbols. n = 8.

When the total gut bacterial counts in the feces were compared, there were no differences between the three groups. When the bacterial count of L. rhamnosus was compared, the value for day 5 feces (1-day feces after L. rhamnosus administration) was dramatically increased compared to day 0 feces (1-day feces before L. rhamnosus administration) in the L. rhamnosus group and the L. rhamnosus + GNB group mice, indicating that L. rhamnosus was successfully detected in the feces. When we compared the bacterial count of L. rhamnosus in day 6 feces (1-day feces at 2 days after L. rhamnosus administration), we found that the L. rhamnosus number did not decrease in the L. rhamnosus + GNB group compared to that of the day 5 feces, whereas the bacterial number was decreased in the L. rhamnosus group, resulting in a significantly higher amount of L. rhamnosus being detected in the L. rhamnosus + GNB group compared with that in the L. rhamnosus group (P = 0.0134, Fig. 6C).

We evaluated the physiological effects on mice administered with L. rhamnosus and GNB. There was no significant difference between the L. rhamnosus group and the L. rhamnosus + GNB group in terms of immunoglobulin and plasma glucagon-like peptide (GLP)-1 levels in the plasma (Table S1), IgA levels in the feces (Fig. S3), or retinal dehydrogenase (RALDH) 2 gene expression in mesenteric lymph node (MLN) and Peyer’s patch (PP) cells (Fig. S4), which have been reported to increase in conjunction with intestinal acetate (10, 48). However, the administration of L. rhamnosus significantly increased the expressions of immune-related genes in the MLN [interleukin (IL)-10 for the L. rhamnosus + GNB group and IL-12 for both the L. rhamnosus group and the L. rhamnosus + GNB group] and PP (IL-12 for both the L. rhamnosus group and the L. rhamnosus + GNB group) (Fig. S4).

DISCUSSION

Acetate, a microbiota-derived bacterial fermentation product, is critically involved in the alleviation of various disorders, including diabetes by suppressing insulin-mediated fat accumulation (7), constipation by changing the intestinal microbiota (49), bacterial infection by increasing immunoglobulin A production and affinity maturation (50, 51), and food allergies by increasing Treg-cell differentiation (10). One strategy to increase intestinal acetate is to promote the proliferation of intestinal bifidobacteria, by which acetate is the main metabolite produced. For this purpose, inulin, which increases intestinal bifidobacteria and, consequently, acetate in the intestine (52), is commercially available. On the other hand, because of their limited acetate-producing ability, the intestinal LAB have not yet been studied as acetate producers, although the habitat of lactic acid bacteria, the small intestine, is an attractive region in light of its immunological significance.

Due to its anaerobic condition, anaerobes dominate in the large intestine (1012 CFU/mL), whereas the small intestine, especially the jejunum, supports the colonization of Gram-positive and facultative bacteria, such as LAB species, and the bacterial density reaches 103–7 CFU/mL in the jejunum and subsequently 109 CFU/mL in the ileum (53). LAB found in the GI tracts have received abundant attention owing to their health-promoting properties (54). They interact with human immune cells in the GI tracts, especially in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue, and regulate specific pathways involved in innate and adaptive immune responses, further supporting the immune system (55). In this study, we demonstrated that GNB could induce intestinal LAB to exhibit an additional health-promoting property, acetate production. We found that LAB that colonize the human gut, such as L. rhamnosus, L. casei, L. johnsonii, and L. gasseri, produced considerable amounts of acetate when metabolizing GNB, which contains N-acetylated amino sugar, N-acetylgalactosamine, as a building component.

RNA-seq analysis of GNB-metabolizing L. rhamnosus cells compared with that of GalNAc, Gal, and Glc revealed two associated factors: acetate-producing metabolism and bacterial cell adhesion. Bidart et al. (21) reported a gene cluster of L. casei for utilization of GNB, lacto-N-biose, and GalNAc. The upregulated genes of L. rhamnosus cluster D (RS11890, RS11895, RS11900, RS11905, RS11910, RS11915, RS11920, and RS11925) corresponded to the genes of the L. casei GNB utilizing cluster, GntR family transcriptional regulator (89.9% identity), galactosamine-6P isomerizing deaminase (92.7% identity), GalNAc-6P deacetylase (93.8% identity), phospho-β-galactosidase (88.3% identity), and RTS components IIB (91.3% identity), IIC (86.6% identity), IID (91.2% identity), and IIA (93.65% identity), respectively. GalNAc-6P deacetylase removes the acetyl group from GalNAc-6P to produce galactosamine-6P and acetate, suggesting that this contributes to increased acetate production by L. rhamnosus. The upregulation of cluster C implies that L. rhamnosus transports N-acetylated sugars (GNB and GalNAc, but not galactose and glucose) into the cytoplasm using both GNB transporter (in cluster D) and N-acetylmuramic acid transporter (in cluster C).

The gene cluster that increases acetyl-CoA production (cluster B) was also upregulated during GNB metabolism. The resultant acetyl-CoA has two alternative fates: conversion to acetate (phosphotransacetylase-acetate kinase pathway) or reduction to ethanol (catalyzed by alcohol dehydrogenase) (56). Ethanol concentration was not increased when GNB was metabolized. Increased acetyl-CoA might be converted to acetate, resulting to an increase in the acetate production.

One postulated feature considered indispensable for probiotics is their adherence to human intestinal tissues, which can promote a variety of specific interactions with the host, thereby strengthening their probiotic properties (57). Mucosal adhesive properties also play a crucial role in the use of mucosal vaccines to reach immune-inductive sites and induce efficient systemic and mucosal immune responses (58, 59). Serine-rich repeat proteins, which are cell-anchoring proteins with heavily glycosylated serine-rich region, are a family of adhesins in Gram-positive bacteria that are vital for attachment to host mucosal epithelial cells (60). GNB utilization upregulated the expressions of genes annotated as serine-rich repeat proteins (RS13130 in cluster E and RS13565 in cluster F). Although cluster E contained both genes involved in sorbitol transport and serine-rich repeat proteins, genes related to sorbitol transport were upregulated not only in GNB and GalNAc metabolism but also in galactose metabolism (Table 2), suggesting that only genes related to serine-rich repeat proteins were involved in GNB and GalNAc metabolism.

When the functional domains in proteins of RS13130 and RS13565 were analyzed using InterPro (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/) (61), they were predicted to be membrane-bound proteins with signal peptides. When the O-glycosites in proteins of RS13130 and RS13565 were predicted using GlycoPP (http://crdd.osdd.net/raghava/glycopp/) (62), RS13130 contained 264 O-glycosites in 1,071 amino acids and RS13565 contained 41 O-glycosites in 143 amino acids, suggesting that they could be adhesins crucial for adherence and colonization in the GI tract.

Although end products of LAB affect the functionality of LAB for human health, knowledge about the relationship between their substrate utilization and end-product formation is limited.de Fátima Alvarez et al. (63) reported that the anaerobic fermentation of the non-carbohydrate substrate glycerol by L. rhamnosus JCM1136T also yielded a considerable amount of acetate (3.6-fold higher than glucose). In the future, we wish to reveal the underlying molecular mechanism that increases acetate production by this strain, including the transcriptional regulators of the involved genes.

The acetate-increasing effect of GNB on intestinal LAB was confirmed in vivo following L. rhamnosus administration. The acetate concentration only increased in the L. rhamnosus + GNB group, whereas the lactate concentration increased in both the L. rhamnosus group and the L. rhamnosus + GNB group. In the intestine, L. rhamnosus could produce acetate only in the presence of GNB. In this study, we did not observe the physiological differences caused by increased intestinal acetate between the L. rhamnosus group and the L. rhamnosus + GNB group. Experiments to administrate GNB for a longer period (e.g. 4 weeks) (64, 65) may be needed to evaluate the immunomodulating effect caused by intestinal acetate.

Another notable difference between the L. rhamnosus group and the L. rhamnosus + GNB group was the colonization rate. The L. rhamnosus number quantified at 2 days after administration in the L. rhamnosus + GNB group was significantly higher than that in the L. rhamnosus group, whereas the L. rhamnosus number at 1 day after administration was not different between the L. rhamnosus group and the L. rhamnosus + GNB group, suggesting that the difference was not due to the proliferative effect of GNB but rather to the colonization-enhancing effect. The RNA-seq analysis also implied the colonization-enhancing effect of GNB corresponded with increased expression of adhesins. Intense ongoing research could reveal the functional implications of the increase in these adhesins on the colonization in the GI tract.

In conclusion, GNB, one of the major building blocks of intestinal mucin, can nourish intestinal LAB and modulate them to stimulate acetate production and increase colonization property. These new insights into the properties of GNB will extend the possible therapeutic applications of beneficial LAB.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

Gut bacterial species, which were previously reported as human gut bacterial species (Table 1), were obtained from the Japan Collection of Microorganisms (JCM, RIKEN Bioresource Center, Tsukuba, Japan). The bacteria were inoculated in 8 mL of GAM broth (Nissui Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), pre-cultured for 24 h at 37°C under anaerobic conditions using Anaeropack (Mitsubishi Gas Chemical, Tokyo, Japan), and the pre-cultures were used to inoculate each prebiotic-containing medium.

Preparation of prebiotic-containing media

GNB and lacto-N-biose were synthesized as previously described (66). Raffinose and 1-kestose were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). Lactose and cellobiose were purchased from Nacalai Tesque Inc. (Kyoto, Japan). Chicory inulin, lactulose, and 2′-fucosyllactose were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Twofold concentrated GAM without sugar (2× woC medium) was prepared as follows: 105 g of semisolid GAM without dextrose broth (Nissui Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.) was dissolved in 1,000 mL of water, filtered to remove agar, and autoclaved. Each prebiotic (GNB, inulin, lactose, cellobiose, raffinose, lactulose, 1-kestose, 2′-fucosyllactose, or lacto-N-biose) or monosaccharide (glucose, galactose, GlcNAc, or GalNAc) solution, at 0.6% (wt/wt), was autoclaved and mixed with the same volume of 2× woC medium, resulting in a 0.3% prebiotic- or monosaccharide-containing media. These media were used to compare the bacterial growth. As a negative control medium, woC medium was prepared by mixing 2 × woC medium with the same volume of water.

Bacterial growth in prebiotic-containing media

Bacterial growth in the prebiotic-containing media was evaluated as previously described (67). Briefly, the pre-culture (5 µL) of each bacterial strain was inoculated in 200 µL of prebiotic- or monosaccharide-containing media and was cultured in triplicate in 96-well plates. After 48 h of anaerobic incubation at 37°C, growth was measured as the optical density at 600 nm (OD600). The bacterial cultures were then centrifuged (16,000 × g, 10 min), and the supernatants were collected and used for metabolite analysis. To compare the ability of bacterial species to utilize prebiotics (GNB and inulin), the OD600 ratio was obtained by dividing the bacterial growth (OD600) in GNB or inulin medium by that in woC medium:

Metabolite analysis

To determine acetate, propionate, and n-butyrate contents, aliquots (50 µL) of the bacterial culture supernatant were added to 10 µL of internal standard (10-mmol/L acetic acid-d4) and 250 µL of methanol and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for deproteinization. The supernatant (180 µL) was collected and added to 20 µL of methanol solution that contained a 100-mmol/L concentration of both 4-(4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)-4-methylmorpholinium chloride (Sigma-Aldrich) and n-octylamine (Tokyo Kasei Kogyo, Tokyo, Japan), and then left at room temperature for 9 h for derivatization. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis was performed using an Agilent 8890GC/5977MSD (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) with a DB-5ms capillary column (0.25 mm inner diameter, 0.25 µm film thickness, 30 m length; Agilent Technologies Inc.) programmed to 60°C (held for 2 min), increasing by 15 °C/min increments up to 320°C (held for 5 min). The MS data were collected in a selective ion monitoring mode with an electron voltage of 1.2 kV and an interface temperature of 280°C. The m/z values were monitored for acetate 114 (10.35 min), propionate 114 (11.0 min), n-butyrate 199 (11.6 min), and acetic acid-d4 117 (10.35 min).

To determine lactate contents, aliquots (50 µL) of the supernatant were derivatized with 2-nitrophenylhydrazine hydrochloride in the presence of 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride and measured with a high-performance liquid chromatograph (e2695 model; Waters, Milford, MA, USA) equipped with a Waters 2998 photodiode array detector (operating at 230 nm). A YMC-Pack FA column (6-mm inner diameter, 250-mm length; YMC Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) was maintained at 50°C and eluted with acetonitrile-methanol-water (30:16:54) at a flow rate of 1.2 mL/min.

To compare the bacterial acetate production by metabolizing prebiotics (GNB and inulin) to that by metabolizing Glc, the acetate ratio was obtained by dividing the acetate concentration in GNB or inulin medium by that in Glc medium. The resulting values were visualized with a heat map using the graphing method of the ggplot2 package in R software.

Phylogenetic tree construction

To evaluate the bias of genus groups on bacterial acetate production, the 16S rRNA sequences of the bacterial strains were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information database. These sequences were aligned using ClustalW and were used to construct a phylogenetic tree. Evolutionary analyses were conducted using MEGA X (68). The evolutionary history was inferred using the neighbor-joining method (69). Bootstrap analysis based on 1,000 replications was performed to evaluate the tree topologies. The percentages of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1,000 replicates) are shown (70). Evolutionary distances were computed using the maximum composites likelihood method (71) and are expressed as the number of base substitutions per site.

RNA-seq analysis

A transcriptional screen was performed to examine the differentially regulated genes when L. rhamnosus was grown in media containing positive or negative carbon sources for acetate-increasing effect. GNB and GalNAc were used as positive carbon sources for the acetate-increasing effect, whereas glucose and galactose were used as negative carbon sources. RNA was extracted from the cells grown to an OD600 of 0.3. Total bacterial RNA was isolated using a RiboPure-Bacteria Kit (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. A MICROBExpress Bacterial mRNA Purification Kit (Invitrogen Corp.) was used to deplete the pool of 16S and 23S rRNA molecules present in the sample following the manufacturer’s recommendations. The purified RNA was sent to Seibutsu Giken Inc. (Kanagawa, Japan) for next-generation sequencing. RNA sample concentrations were measured using a Quantus Fluorometer and QuantiFluor RNA System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The RNA quality was checked using a 5200 Fragment Analyzer System and Agilent HS RNA Kit (Agilent Technologies Inc.). A next-generation sequencing library was prepared using the MGIEasy RNA Directional Library Prep Set (MGI Tech Co., Ltd., PR China), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The library concentrations were measured using the Synergy LX and Quanti Fluor dsDNA systems, while the library quality was checked using a Fragment Analysis and DNF-915 dsDNA Reagent Kit (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Circular DNA was prepared from the library using an MGIEasy Circularization Kit (MGI Tech Co., Ltd.). DNA nanoballs (DNBs) were prepared using a DNBSEQG G400 RS high-throughput sequencing kit (MGI Tech Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Sequencing was performed using DNBSEQ-G400 for at least 2 × 100 bp reads. Adapters and primers from the FASTQ files were removed using Cutadapt (version 1.9.1). Short-read sequences (<20) and low-quality score reads (<40) were removed using a Sickle (version 1.33). Bowtie2 (version 2.4.1) was used to read the alignment and map the L. rhamnosus JCM1136T reference genome (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/assembly/GCF_001435405.1/). After reading and writing the alignment data in SAM and BAM formats using SAM tools (version 1.11), the data were sorted and indexed. The read counts per gene were obtained using featureCounts (version 2.0.0). The relative expression of each gene was RPKM and transcripts per million. Differential expression analyses were performed using the DESeq2 algorithm. Gene expressions in cells grown in GNB, GalNAc, or Gal medium were compared to that in Glc-grown cells. To analyze gene clusters in the L. rhamnosus genome sequences, In Silico MolecularCloning software (In Silico Biology, Inc., Yokohama, Japan) was used. The R package ggplot2 was used to draw a volcano plot comparing RNA expression profiles. All raw FASTQ files produced by RNA-seq were deposited in the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ) Sequence Read Archive under the BioProject accession number PRJDB16434 (run: DRR498818–DRR49898829, bio-sample: SAMD00637344-SAMD00637355).

In vivo administration of GNB and L. rhamnosus

Six-week-old male BALB/cA mice used for this study were obtained from CLEA Japan Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). The mice were kept at 18°C–24°C and 40%–70% relative humidity with a 12-h light/dark cycle. They were fed a standard AIN-76 diet (Research Diets, Inc., New Brunswick, NJ, USA) and water ad libitum for an acclimatization period of 1 week.

After acclimatization, the mice were administered with vancomycin (0.5 g/L) and doripenem (0.25 g/L) in the drinking water for 10 days. The mice were then divided into three groups, and oral administration of 1 × 109L. rhamnosus cells (L. rhamnosus group), 1 × 109L. rhamnosus cells and 50 mg of GNB (L. rhamnosus + GNB group), or saline (control group) was performed 1 day after the end of the antibiotic administration. The administration schedule is shown in Fig. 6A. Body weight and water and food intake were measured. Fecal samples produced in 1 day were collected on day 0 (before the first administration), day 5 (1 day after the third administration), and day 6 (2 days after the third administration), as shown in Fig. 6A. These feces were freeze-dried and maintained at −80°C until processing. On day 6, the mice were sacrificed under anesthesia. To obtain preliminary insights into the safety of GNB and bacterial intake for mice, plasma AST, ALT, and CRE were analyzed. Plasma AST and ALT levels, which are elevated with abnormal liver function, were analyzed using a Transaminase CII kit (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd.). Plasma CRE contents, which are increased with poor kidney function, were analyzed using a LabAssay Creatinine kit (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd.). Plasma GLP-1 levels were analyzed using a GLP-1 ELISA kit (Millipore Corp., Milford, MA, USA).

For gene expression analysis using reverse-transcription quantitative PCR in MLN and PP, total RNA was extracted using a QuickPrep Total RNA Extraction kit (GE Healthcare BioSciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized with SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen Corp.) and oligo (dT) primers (Invitrogen Corp.) and then purified using a PCR Purification kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and Power SYBR Green Master Mix (Life Technologies Japan Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The expression levels of IL-6 (Il6), IL-10 (Il10), IL-12 (Il12b), B cell-activating factor (Tnfsf13b), a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL, Tnfsf13), and retinal dehydrogenase 2 ( Aldh1a2) were normalized to those of the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, which was used as an internal control. The primer sequences are listed in Table S2. Expression was quantified in triplicates. The PCR products were evaluated by analyzing melting curves.

Fecal sample preparation

To determine the IgA concentrations, freeze-dried fecal samples were homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) and allowed to stand for 30 min on ice to extract the IgA. After centrifugation, the supernatant was collected, and the IgA levels were measured using a mouse IgA ELISA kit (Bethyl Laboratory Inc., TX, USA).

To determine fecal metabolites, the freeze-dried fecal samples were homogenized using 3-mm zirconia/silica beads (BioSpec Products, Bartlesville, OK, USA) in water. After centrifugation, the supernatant was used for metabolite analysis as described above.

Total DNA was extracted from fecal samples using a QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini kit (Qiagen) with slight modifications. Briefly, frozen stool samples were transferred into EZ-Beads tubes (Promega), which are 2-mL microcentrifuge tubes containing two types of zirconia beads, and 1,000 µL of InhibitEX buffer was added. The samples were homogenized in a multi-bead shocker (Yasuikikai, Osaka, Japan) at 2,500 rpm for 1 min. The beads were pelleted, and the supernatant was transferred into a sterile 2-mL microcentrifuge tube. Fresh InhibitEX buffer (300 µL) was added to each EZ-Beads tube, followed by repeated homogenization at 2,500 rpm for 1 min. The beads were pelleted, and the supernatant was combined with the supernatant from the first extraction step. DNA was isolated as outlined in the QIAamp DNA Stool Mini kit manual. DNA was eluted in 200-µL MilliQ, and the DNA concentration was determined with a NanoDrop 2000c (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). DNA integrity was examined by 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis. The DNA samples were stored at −30°C until further use.

Quantitative PCR to assess bacterial abundance

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed using a real-time PCR system (StepOne, Applied Biosystems) with Power SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The total number of bacteria and L. rhamnosus JCM1136T in the feces was determined by qPCR targeting a 185-bp fragment of the 16S rRNA gene or a 186-bp fragment of the JCM1136T mutL gene, respectively. The primer sequences are listed in Table S3. The PCR reaction mixture had a final volume of 10 µL, consisting of 5 µL of the Power SYBR Green Master Mix and both the forward and the reverse primers (20-µM final) and 10 ng of fecal gDNA. The PCR thermocycling conditions used for the real-time PCR are listed in Table S3. Melting curves were generated after each cycle to verify the specific amplification. Electrophoresis on a 0.8% agarose gel was also performed to verify the specific amplification. Known concentrations of the genomic DNA from L. rhamnosus JCM1136T were used to create calibration curves for the total 16S rRNA and mutL genes.

Statistics

The data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison tests. The statistical analyses were conducted using the Ekuseru Toukei software (SSRI, Tokyo, Japan). The results are expressed as the means ± standard deviation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Adaptable and Seamless Technology Transfer Program through Target-driven R&D (Seeds Development Type, grant number JPMJTR20UG) of Japan Science and Technology Agency. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

C.M., Y.K., and Mis.Y. performed the experiments. C.M., H.T., Y.H., and Mas.Y. conceived and designed the experiments. H.T. and S.S. contributed to the data analyses.

We declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Chiaki Matsuzaki, Email: chiaki@ishikawa-pu.ac.jp.

Sophie Roussel, Anses, France.

ETHICS APPROVAL

The animals were handled in accordance with the Guidelines for the Proper Conduct of Animal Experiments issued by the Science Council of Japan (2006). The experimental protocol was approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of the Ishikawa Prefectural University (approval ID: R4-14-10).

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.01445-23.

Supplemental tables and figures.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Joint FAO/WHO working group report on drafting guidelines for the evaluation of probiotics in food . 2002. London, Ontario, Canada [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fijan S. 2014. Microorganisms with claimed probiotic properties: an overview of recent literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health 11:4745–4767. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110504745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brown K, DeCoffe D, Molcan E, Gibson DL. 2012. Diet-induced dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiota and the effects on immunity and disease. Nutrients 4:1095–1119. doi: 10.3390/nu4081095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Silva DR, Sardi JDCO, de Souza Pitangui N, Roque SM, Silva ACB, Rosalen PL. 2020. Probiotics as an alternative antimicrobial therapy: current reality and future directions. Journal of Functional Foods 73:104080. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2020.104080 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Suvorov A. 2013. Gut microbiota, probiotics, and human health. Biosci Microbiota Food Health 32:81–91. doi: 10.12938/bmfh.32.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yan F, Polk DB. 2011. Probiotics and immune health. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 27:496–501. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32834baa4d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kimura I, Ozawa K, Inoue D, Imamura T, Kimura K, Maeda T, Terasawa K, Kashihara D, Hirano K, Tani T, Takahashi T, Miyauchi S, Shioi G, Inoue H, Tsujimoto G. 2013. The gut microbiota suppresses insulin-mediated fat accumulation via the short-chain fatty acid receptor GPR43. Nat Commun 4:1829. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Salamone D, Rivellese AA, Vetrani C. 2021. The relationship between gut microbiota, short-chain fatty acids and type 2 diabetes mellitus: the possible role of dietary fibre. Acta Diabetol 58:1131–1138. doi: 10.1007/s00592-021-01727-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Parada Venegas D, De la Fuente MK, Landskron G, González MJ, Quera R, Dijkstra G, Harmsen HJM, Faber KN, Hermoso MA. 2019. Short chain fatty acids (SCFAs)-mediated gut epithelial and immune regulation and its relevance for inflammatory bowel diseases. Front Immunol 10:277. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tan J, McKenzie C, Vuillermin PJ, Goverse G, Vinuesa CG, Mebius RE, Macia L, Mackay CR. 2016. Dietary fiber and bacterial SCFA enhance oral tolerance and protect against food allergy through diverse cellular pathways. Cell Rep 15:2809–2824. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bouhnik Y, Pochart P, Marteau P, Arlet G, Goderel I, Rambaud JC. 1992. Fecal recovery in humans of viable Bifidobacterium sp ingested in fermented milk. Gastroenterology 102:875–878. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90172-u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kullen MJ, Amann MM, O’Shaughnessy MJ, O’Sullivan DJ, Busta FF, Brady LJ. 1997. Differentiation of ingested and endogenous bifidobacteria by DNA fingerprinting demonstrates the survival of an unmodified strain in the gastrointestinal tract of humans. J Nutr 127:89–94. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.1.89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Marco ML, Bongers RS, de Vos WM, Kleerebezem M. 2007. Spatial and temporal expression of Lactobacillus plantarum genes in the gastrointestinal tracts of mice. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:124–132. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01475-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gibson GR, Roberfroid MB. 1995. Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota: introducing the concept of prebiotics. J Nutr 125:1401–1412. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.6.1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Takemura N, Ozawa K, Kimura N, Watanabe J, Sonoyama K. 2010. Inulin-type fructans stimulated the growth of exogenously administered Lactobacillus plantarum No.14 in the mouse gastrointestinal tract. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 74:375–381. doi: 10.1271/bbb.90794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Su P, Henriksson A, Mitchell H. 2007. Prebiotics enhance survival and prolong the retention period of specific probiotic inocula in an in vivo murine model. J Appl Microbiol 103:2392–2400. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03469.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. González-Morelo KJ, Vega-Sagardía M, Garrido D. 2020. Molecular insights into O-linked glycan utilization by gut microbes. Front Microbiol 11:591568. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.591568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yamaguchi M, Yamamoto K. 2023. Mucin glycans and their degradation by gut microbiota. Glycoconj J 40:493–512. doi: 10.1007/s10719-023-10124-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nishimoto M, Kitaoka M. 2007. Identification of N-acetylhexosamine 1-kinase in the complete lacto-N-biose I/galacto-N-biose metabolic pathway in Bifidobacterium longum. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:6444–6449. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01425-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Katoh T, Yamada C, Wallace MD, Yoshida A, Gotoh A, Arai M, Maeshibu T, Kashima T, Hagenbeek A, Ojima MN, Takada H, Sakanaka M, Shimizu H, Nishiyama K, Ashida H, Hirose J, Suarez-Diez M, Nishiyama M, Kimura I, Stubbs KA, Fushinobu S, Katayama T. 2023. A bacterial sulfoglycosidase highlights mucin O-glycan breakdown in the gut ecosystem. Nat Chem Biol 19:778–789. doi: 10.1038/s41589-023-01272-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bidart GN, Rodríguez-Díaz J, Monedero V, Yebra MJ. 2014. A unique gene cluster for the utilization of the mucosal and human milk‐associated glycans Gglacto‐N‐biose and lacto‐N‐biose in Lactobacillus casei. Mol Microbiol 93:521–538. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kiyohara M, Tachizawa A, Nishimoto M, Kitaoka M, Ashida H, Yamamoto K. 2009. Prebiotic effect of lacto-N-biose I on bifidobacterial growth. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 73:1175–1179. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf KS, Manichanh C, Nielsen T, Pons N, Levenez F, Yamada T, et al. 2010. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature 464:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature08821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hou F, Tang J, Liu Y, Tan Y, Wang Y, Zheng L, Liang D, Lin Y, Wang L, Pan Z, Yang R, Bi Y, Zhi F. 2023. Safety evaluation and probiotic potency screening of Akkermansia muciniphila strains isolated from human feces and breast milk. Microbiol Spectr 11:e0336122. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.03361-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ma T, Yao C, Shen X, Jin H, Guo Z, Zhai Q, Yu-Kwok L, Zhang H, Sun Z. 2021. The diversity and composition of the human gut lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacterial microbiota vary depending on age. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 105:8427–8440. doi: 10.1007/s00253-021-11625-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shimizu K. 2017. Characteristics of human-residential Bifidobacteria and technique for application in yogurt. Milk Science 66:45–51. doi: 10.11465/milk.66.45 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Morita H, Toh H, Oshima K, Nakano A, Yamashita N, Iioka E, Arakawa K, Suda W, Honda K, Hattori M. 2015. Complete genome sequence of Bifidobacterium catenulatum JCM 1194T isolated from human feces. J Biotechnol 210:25–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2015.06.415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Junick J, Blaut M. 2012. Quantification of human fecal Bifidobacterium species by use of quantitative real-time PCR analysis targeting the groEL gene. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:2613–2622. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07749-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kageyama A, Sakamoto M, Benno Y. 2000. Rapid identification and quantification of Collinsella aerofaciens using PCR. FEMS Microbiol Lett 183:43–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb08931.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hayashi H, Sakamoto M, Kitahara M, Benno Y. 2006. Diversity of the Clostridium coccoides group in human fecal microbiota as determined by 16S rRNA gene library. FEMS Microbiol Lett 257:202–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00171.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang RF, Cao WW, Cerniglia CE. 1996. PCR detection and quantitation of predominant anaerobic bacteria in human and animal fecal samples. Appl Environ Microbiol 62:1242–1247. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.4.1242-1247.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Senda S, Fujiyama Y, Ushijima T, Hodohara K, Bamba T, Hosoda S, Kobayashi K. 1985. Clostridium ramosum, an IgA protease-producing species and its ecology in the human intestinal tract. Microbiol Immunol 29:1019–1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1985.tb00892.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Boureau H, Decré D, Carlier JP, Guichet C, Bourlioux P. 1993. Identification of a Clostridium cocleatum strain involved in an anti-Clostridium difficile barrier effect and determination of its mucin-degrading enzymes. Res Microbiol 144:405–410. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(93)90198-b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sanz Y, Sánchez E, Marzotto M, Calabuig M, Torriani S, Dellaglio F. 2007. Differences in faecal bacterial communities in coeliac and healthy children as detected by PCR and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 51:562–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2007.00337.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Klijn N, Weerkamp AH, de Vos WM. 1995. Genetic marking of Lactococcus lactis shows its survival in the human gastrointestinal tract. Appl Environ Microbiol 61:2771–2774. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.7.2771-2774.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Song YL, Kato N, Matsumiya Y, Liu CX, Kato H, Watanabe K. 1999. Identification of and hydrogen peroxide production by fecal and vaginal lactobacilli isolated from Japanese women and newborn infants. J Clin Microbiol 37:3062–3064. doi: 10.1128/JCM.37.9.3062-3064.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dal Bello F, Walter J, Hammes WP, Hertel C. 2003. Increased complexity of the species composition of lactic acid bacteria in human feces revealed by alternative incubation condition. Microb Ecol 45:455–463. doi: 10.1007/s00248-003-2001-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pridmore RD, Berger B, Desiere F, Vilanova D, Barretto C, Pittet AC, Zwahlen MC, Rouvet M, Altermann E, Barrangou R, Mollet B, Mercenier A, Klaenhammer T, Arigoni F, Schell MA. 2004. The genome sequence of the probiotic intestinal bacterium Lactobacillus johnsonii NCC 533. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:2512–2517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307327101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sakai Y. 2019. Prebiotics. J Intestinal Microbiol 33:165–174. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fujii T, Nakano M, Shinohara H, Ishikawa H, Yasutake T, Watanabe A, Funasaka K, Hirooka Y, Tochio T. 2022. 1-kestose supplementation increases levels of a 5Α-reductase gene, a key isoallolithocholic acid biosynthetic gene, in the intestinal microbiota. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 68:446–451. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.68.446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Matsuki T, Yahagi K, Mori H, Matsumoto H, Hara T, Tajima S, Ogawa E, Kodama H, Yamamoto K, Yamada T, Matsumoto S, Kurokawa K. 2016. A key genetic factor for fucosyllactose utilization affects infant gut microbiota development. Nat Commun 7:11939. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Xiao J, Takahashi S, Nishimoto M, Odamaki T, Yaeshima T, Iwatsuki K, Kitaoka M. 2010. Distribution of in vitro fermentation ability of lacto-N-biose I, a major building block of human milk oligosaccharides, in bifidobacterial strains. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:54–59. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01683-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. El Kiyat W, Astuti SD, Budijanto S, Syamsir E. 2021. Potential of lacto-N-biose I as a prebiotic for infant health: a review. CST 6:18–24. doi: 10.21924/cst.6.1.2021.277 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shoji A, Iga T, Inagaki S, Kobayashi K, Matahira Y, Sakai K. 1999. Metabolic disposition of [14 C] N-acetylglucosamine in rats. Chitin Chitosan Res 5:34–42. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Kawashima M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. 2016. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res 44:D457–62. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Uehara T, Suefuji K, Jaeger T, Mayer C, Park JT. 2006. MurQ etherase is required by Escherichia coli in order to metabolize anhydro-N-acetylmuramic acid obtained either from the environment or from its own cell wall. J Bacteriol 188:1660–1662. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.4.1660-1662.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dahl U, Jaeger T, Nguyen BT, Sattler JM, Mayer C. 2004. Identification of a phosphotransferase system of Escherichia coli required for growth on N-acetylmuramic acid. J Bacteriol 186:2385–2392. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.8.2385-2392.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kim M, Qie Y, Park J, Kim CH. 2016. Gut microbial metabolites fuel host antibody responses. Cell Host Microbe 20:202–214. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang L, Cen S, Wang G, Lee Y, Zhao J, Zhang H, Chen W. 2020. Acetic acid and butyric acid released in large intestine play different roles in the alleviation of constipation. Journal of Functional Foods 69:103953. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2020.103953 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wu W, Sun M, Chen F, Cao AT, Liu H, Zhao Y, Huang X, Xiao Y, Yao S, Zhao Q, Liu Z, Cong Y. 2017. Microbiota metabolite short-chain fatty acid acetate promotes intestinal IgA response to microbiota which is mediated by GPR43. Mucosal Immunol 10:946–956. doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Takeuchi T, Miyauchi E, Kanaya T, Kato T, Nakanishi Y, Watanabe T, Kitami T, Taida T, Sasaki T, Negishi H, Shimamoto S, Matsuyama A, Kimura I, Williams IR, Ohara O, Ohno H. 2021. Acetate differentially regulates IgA reactivity to commensal bacteria. Nature 595:560–564. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03727-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Birkeland E, Gharagozlian S, Birkeland KI, Valeur J, Måge I, Rud I, Aas AM. 2020. Prebiotic effect of inulin-type fructans on faecal microbiota and short-chain fatty acids in type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Nutr 59:3325–3338. doi: 10.1007/s00394-020-02282-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Adak A, Khan MR. 2019. An insight into gut microbiota and its functionalities. Cell Mol Life Sci 76:473–493. doi: 10.1007/s00018-018-2943-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Walter J. 2008. Ecological role of lactobacilli in the gastrointestinal tract: implications for fundamental and biomedical research. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:4985–4996. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00753-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tsai YT, Cheng PC, Pan TM. 2012. The immunomodulatory effects of lactic acid bacteria for improving immune functions and benefits. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 96:853–862. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4407-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wolfe AJ. 2005. The acetate switch. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 69:12–50. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.1.12-50.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kankainen M, Paulin L, Tynkkynen S, von Ossowski I, Reunanen J, Partanen P, Satokari R, Vesterlund S, Hendrickx APA, Lebeer S, et al. 2009. Comparative genomic analysis of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG reveals pili containing a human-mucus binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:17193–17198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908876106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Pouwels PH, Leer RJ, Shaw M, Heijne den Bak-Glashouwer MJ, Tielen FD, Smit E, Martinez B, Jore J, Conway PL. 1998. Lactic acid bacteria as antigen delivery vehicles for oral immunization purposes. Int J Food Microbiol 41:155–167. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(98)00048-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Vilander AC, Shelton K, LaVoy A, Dean GA. 2023. Expression of E. coli FimH enhances trafficking of an orally delivered Lactobacillus acidophilus vaccine to immune Inductive sites via antigen-presenting cells. Vaccines (Basel) 11:1162. doi: 10.3390/vaccines11071162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sequeira S, Kavanaugh D, MacKenzie DA, Šuligoj T, Walpole S, Leclaire C, Gunning AP, Latousakis D, Willats WGT, Angulo J, Dong C, Juge N. 2018. Structural basis for the role of serine-rich repeat proteins from Lactobacillus reuteri in gut microbe–host interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:E2706–E2715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1715016115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Paysan-Lafosse T, Blum M, Chuguransky S, Grego T, Pinto BL, Salazar GA, Bileschi ML, Bork P, Bridge A, Colwell L, et al. 2023. InterPro in 2022. Nucleic Acids Res 51:D418–D427. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Chauhan JS, Bhat AH, Raghava GPS, Rao A. 2012. GlycoPP: a webserver for prediction of N-and O-glycosites in prokaryotic protein sequences. PLoS One 7:e40155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. de Fátima Alvarez M, Medina R, Pasteris SE, Strasser de Saad AM, Sesma F. 2004. Glycerol metabolism of Lactobacillus rhamnosus ATCC 7469: cloning and expression of two glycerol kinase genes. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 7:170–181. doi: 10.1159/000079826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Guo J, Zhang M, Wang H, Li N, Lu Z, Li L, Hui S, Xu H. 2022. Gut microbiota and short chain fatty acids partially mediate the beneficial effects of inulin on metabolic disorders in obese ob/ob mice. J Food Biochem 46:e14063. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.14063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Dewulf EM, Cani PD, Neyrinck AM, Possemiers S, Van Holle A, Muccioli GG, Deldicque L, Bindels LB, Pachikian BD, Sohet FM, Mignolet E, Francaux M, Larondelle Y, Delzenne NM. 2011. Inulin-type fructans with prebiotic properties counteract GPR43 overexpression and PPARγ-related adipogenesis in the white adipose tissue of high-fat diet-fed mice. J Nutr Biochem 22:712–722. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2010.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Yamaguchi M. 2020. β-galactosidase. Japanese Patent 6771756

- 67. Gotoh A, Nara M, Sugiyama Y, Sakanaka M, Yachi H, Kitakata A, Nakagawa A, Minami H, Okuda S, Katoh T, Katayama T, Kurihara S. 2017. Use of Gifu anaerobic medium for culturing 32 dominant species of human gut microbes and its evaluation based on short-chain fatty acids fermentation profiles. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 81:2009–2017. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2017.1359486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. 2018. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol 35:1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Saitou N, Nei M. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Felsenstein J. 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39:783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Tamura K, Nei M, Kumar S. 2004. Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:11030–11035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404206101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental tables and figures.