Abstract

A significant cardiac complication of diabetes is cardiomyopathy, a form of ventricular dysfunction that develops independently of coronary artery disease, hypertension and valvular diseases, which may subsequently lead to heart failure. Several structural features underlie the development of diabetic cardiomyopathy and eventual diabetes‐induced heart failure. Pathological cardiac fibrosis (interstitial and perivascular), in addition to capillary rarefaction and myocardial apoptosis, are particularly noteworthy. Sex differences in the incidence, development and presentation of diabetes, heart failure and interstitial myocardial fibrosis have been identified. Nevertheless, therapeutics specifically targeting diabetes‐associated cardiac fibrosis remain lacking and treatment approaches remain the same regardless of patient sex or the co‐morbidities that patients may present. This review addresses the observed anti‐fibrotic effects of newer glucose‐lowering therapies and traditional cardiovascular disease treatments, in the diabetic myocardium (from both preclinical and clinical contexts). Furthermore, any known sex differences in these treatment effects are also explored.

LINKED ARTICLES

This article is part of a themed issue on Translational Advances in Fibrosis as a Therapeutic Target. To view the other articles in this section visit http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bph.v180.22/issuetoc

Keywords: cardiac fibrosis, cardiomyopathy, diabetes, heart failure, sex differences

Abbreviations

- ARNi

angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- E/A ratio

early‐to‐late diastolic filling

- HF

heart failure

- HFpEF

heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- HFrEF

heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

- LV

left ventricle

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- MACE

major adverse cardiovascular event

- MI

myocardial infarction

- SMAD

“small” mothers against decapentaplegic

- STZ

streptozotocin

- T1D

type 1 diabetes

- T2D

type 2 diabetes

- TIMP

tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase

1. INTRODUCTION TO THE FAILING HEART

Heart failure (HF) still remains an enormous health and economic burden worldwide. The latest global figures estimate that HF prevalence almost doubled from 33.5 million people in 1990 to 64.3 million people in 2017, and that worldwide HF‐related expenditure was approximately USD $108 billion in 2012 (Cook et al., 2014; James et al., 2018). Although global estimates of HF mortality are lacking, in the United States, for example, one in eight deaths recorded between 2008 and 2018 were worryingly associated with a HF diagnosis (Virani et al., 2021). Further, the number of deaths caused by underlying HF rose to 47.1%, despite the shift to more evidence‐based HF treatment approaches in recent decades (Virani et al., 2021). Most simply put, HF is a clinical syndrome characterised by current or prior pathological changes in myocardial structure and function, which contribute to impairments in left ventricular (LV) filling and/or ejection, termed diastolic and systolic dysfunction, respectively (Bozkurt et al., 2021). However, the manifestation and presentation of HF is anything but simple. Patient sex and co‐morbidities, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity and coronary artery disease (CAD) are associated with the development of different HF phenotypes (Kessler et al., 2019; Virani et al., 2021). These include HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF; where LV ejection fraction [LVEF] is ≤40%), HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF; LVEF ≥ 50%), HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF; LVEF between 41% and 49%) and HF with improved ejection fraction (baseline HFrEF with ≥10% increase from baseline and second measurement of LVEF ˃ 40%) (Bozkurt et al., 2021).

2. IMPACT OF DIABETES AND SEX ON SUSCEPTIBILITY TO HEART FAILURE

Diabetes is closely linked with the development of HF. Individuals affected by diabetes demonstrate an approximately 2.5‐fold increased risk of HF, a risk that is doubled further in women if they are diagnosed with diabetes (Kannel et al., 1974). A distinct complication of diabetes is diabetic cardiomyopathy, a form of ventricular dysfunction which can develop independently of macrovascular conditions such as coronary artery disease, hypertension and valvular diseases (Sharma, Mah, et al., 2021; Tate et al., 2017). Hallmark features of diabetes include hyperglycaemia, insulin resistance, hyperinsulinaemia and hyperactivation of the renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system (RAAS) (Ritchie & Abel, 2020; Tate et al., 2017). These characteristics of diabetes trigger cardiac molecular and cellular pathologies (oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammation and cardiomyocyte apoptosis), which contribute to more extensive structural remodelling of the LV through pathological cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and cardiac interstitial fibrosis (Ritchie & Abel, 2020; Tate et al., 2017). With this adverse remodelling, the LV becomes increasingly stiff and cannot relax efficiently, eventually leads to diastolic dysfunction. This is usually the first clinical sign of diabetic cardiomyopathy, often preceding the development of HFpEF (Jia et al., 2018). Patients may also eventually develop systolic dysfunction and later HFrEF (Jia et al., 2018).

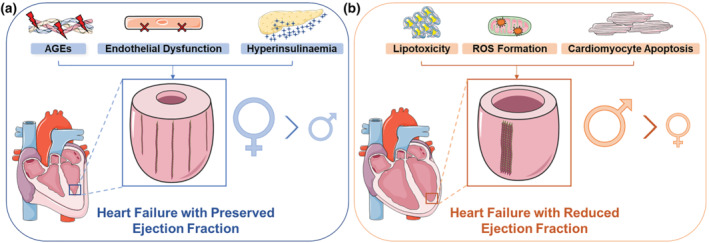

Interestingly, sexual dimorphisms in HF phenotype have been identified, with HFpEF and HFrEF more common in women and men, respectively (Kessler et al., 2019). Various diabetes‐induced pathologies contribute to the development of eccentric cardiac remodelling and eventual HFrEF, phenotypes often observed in men, or concentric remodelling and HFpEF, which is more common in women (Figure 1) (Kessler et al., 2019; Paulus & Dal Canto, 2018; Yap et al., 2019). Furthermore, women are commonly regarded as protected from the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD) until the onset of menopause, where there is a dramatic increase in the incidence of cardiovascular disease and HF events in post‐menopausal women (Muka et al., 2016). Whether oestrogen (17β‐estradiol) exerts this cardioprotection in women pre‐menopause remains controversial (Ueda et al., 2021). The inverse relationship between circulating oestradiol levels and risk of HF, and the higher HF mortality rate in women over the age of 80, certainly suggests some association between alterations in sex hormones post‐menopause and their HF risk (Virani et al., 2021; D. Zhao et al., 2018). Similarly, HF risk is exacerbated with a diabetes diagnosis, a risk which is even more pronounced in women (Kannel et al., 1974). Little has been reported on potential sex differences in diabetic cardiomyopathy, although one pilot study found a higher prevalence of preclinical diabetic cardiomyopathy in women (Kiencke et al., 2010). However, these results cannot be applied to larger populations due to the small sample size of that study. Sex differences have been demonstrated through cluster analysis of patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D), where similar incidence of cardiovascular‐related mortality and hospitalisations were reported in men and women with varying co‐morbidities and cardiac phenotypes (Ernande et al., 2017). These included men with LV hypertrophy and systolic dysfunction, and obese hypertensive women with diastolic dysfunction (Ernande et al., 2017). Additionally, a recent cohort study reported an enhanced risk of HF re‐hospitalisation and all‐cause mortality in women with a history of diabetes and HFrEF (the less common HF phenotype in women) compared with men with similar co‐morbidities (Tay et al., 2021). Meanwhile in preclinical studies, diabetic female mice exhibit greater diastolic dysfunction, even with modest hyperglycaemia, compared with their male counterparts (Chandramouli et al., 2018). Increased cardiac glucose handling and autophagy, alongside exaggerated and faster progression of subclinical pathologies of diabetic cardiomyopathy (pathological cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, cardiac oxidative stress and myocardial interstitial fibrosis), have also been reported in diabetic female mice (Bowden et al., 2015; Chandramouli et al., 2018; Tang et al., 2020).

FIGURE 1.

Diabetes‐induced cardiac pathologies that contribute to the development of left ventricular (LV) remodelling in patients with diabetes and heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction (HFpEF or HFrEF). (a) In the setting of diabetes, hyperglycaemia contributes to the formation and attachment of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) to myocardial collagen fibres. Alongside advanced glycation end products, endothelial cell dysfunction and hyperinsulinaemia promote pathological concentric remodelling whereby the LV thickens and there is increased interstitial and perivascular cardiac fibrosis. Consequently, patients develop HFpEF, a heart failure phenotype more common in women. (b) Diabetes‐induced increases in cardiac lipotoxicity, ROS formation and cardiomyocyte apoptosis contribute to the development of cardiac eccentric remodelling (LV expansion and myocardial wall thinning), ultimately resulting in HFrEF. There is also greater LV replacement fibrosis and scar formation. Men are more likely to develop eccentric cardiac remodelling and HFrEF. Red lightning bolts signify advanced glycation end products (AGEs). Red X's represents cellular dysfunction. Blue stars represent insulin. Orange explosions demonstrate ROS. Brown lines on the LV indicate collagen fibres. See text for references. Schema created using modifications to images provided by Servier Medical Art by Servier (https://smart.servier.com/), licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/)

This phenomenon of diabetic cardiomyopathy is clearly evident in animal models and has been frequently observed in the clinic (Marwick et al., 2018; Ritchie & Abel, 2020). As mentioned previously, diabetic cardiomyopathy is defined as ventricular dysfunction that can develop independently of conditions such as coronary artery disease, hypertension and valvular diseases (Sharma, Mah, et al., 2021; Tate et al., 2017). It is however likely in the clinical context that many patients will also present with other, concomitant co‐morbidities (e.g. atherosclerosis, coronary disease, hypertension and/or past myocardial infarction [MI]) in addition to diabetes and HF. As such, these co‐morbidities may further contribute to the development of different forms of cardiac fibrosis, including replacement fibrosis, and eventual HF. Further, if these co‐morbidities precede diabetes, then diabetes clearly exacerbates progression to HF (Marwick et al., 2018; Ritchie & Abel, 2020). There are a number of contributing factors to the development of diabetic cardiomyopathy and eventual HF, including pathological cardiac fibrosis (interstitial and perivascular), capillary rarefaction and myocardial apoptosis. In this cardiac fibrosis‐themed review, we provide an overview of the pathophysiology of cardiac fibrosis, before discussing the potential cardiac anti‐fibrotic effects of key current and upcoming anti‐diabetic and/or cardiovascular disease therapies in the male and female diabetic heart. The role of other contributing factors to the development of diabetic cardiomyopathy and eventual HF are reviewed elsewhere (Jia et al., 2018; Ritchie & Abel, 2020). Pathological cardiac fibrosis plays a key role in the progression to diabetic cardiomyopathy and eventual HF in both men and women. Normally a healing process post‐injury, in diabetes and HF there is dysregulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) components, particularly fibrillar collagen composed of collagen type I and III fibres, which contributes to stiffening of the myocardium and eventual loss of function (Frangogiannis, 2021), as will be discussed below.

3. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF CARDIAC FIBROSIS IN THE DIABETIC HEART

Under normal physiological conditions, the lattice‐like extracellular matrix provides a scaffold for the cardiac cellular population and aids in the contractile force of the heart (Frangogiannis, 2021). Tight regulation of extracellular matrix components such as collagen, fibronectin, glycosaminoglycans, glycoproteins and proteoglycans is mediated by cardiac fibroblasts through the production of matrix metallopeptidase (MMPs) and its endogenous, naturally occurring inhibitor, tissue inhibitors of metallopeptidase (TIMPs) (Fan et al., 2012; Polyakova et al., 2004). Cardiac fibroblasts further regulate collagen turnover via formation of type I and type III collagen fibres, which maintain myocardial contractile function and elasticity of the extracellular matrix in physiological settings (Frangogiannis, 2021). These collagen fibre types account for approximately 85% and 11% of the total myocardial collagen population, respectively (Kong et al., 2014).

Aberrant deposition and degradation of the extracellular matrix underpin the development of pathological cardiac fibrosis, particularly through elevated fibrillar collagen deposition, changes in the MMP/TIMP ratio and increases in cardiac fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation (Petrov et al., 2002; Polyakova et al., 2004). Specifically, in diabetes, hyperglycaemia directly contributes to fibrosis through the formation of advanced glycation end products which increase cross‐linkage of collagen fibres (Paulus & Dal Canto, 2018). Pro‐fibrotic signalling via the ERK/MAPK, TGF‐β and NF‐ĸB pathways is also enhanced through activation of advanced glycosylation end‐product specific receptor (RAGE) (J.H. Li et al., 2004; Peng et al., 2016). Hyperglycaemia, hyperinsulinaemia and insulin resistance indirectly contribute to further dysfunction of the extracellular matrix through elevating cardiac lipotoxicity and ROS formation, activating the RAAS and heightening the cardiac immune response (Tuleta & Frangogiannis, 2021). Consequently, patients with diabetes may present with different forms of cardiac fibrosis, including interstitial fibrosis, where collagen deposition between cardiomyocytes increases without a major loss in the number of myocytes, perivascular fibrosis, where the microvascular adventitia is expanded and replacement fibrosis, which is common after severe cardiac injury (e.g. MI) where a scar is formed through predominantly type I collagen deposition, compensating for the loss of cardiomyocytes (Kong et al., 2014).

Alterations in cardiac extracellular matrix composition are measured in patients by a number of non‐invasive techniques, most often by echocardiography, the cornerstone of cardiovascular disease diagnosis, but also by nuclear imaging and cardiovascular CT (Mavrogeni et al., 2021). However, cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging is the gold standard for LV soft tissue analysis, whereby late gadolinium enhancement cardiac magnetic resonance detects focal replacement fibrosis, whereas myocardial longitudinal relaxation time (T1) mapping identifies diffuse interstitial fibrosis and calculates the extracellular volume (ECV) fraction (Mavrogeni et al., 2021). Through cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, the associations between enhanced extracellular volume fraction in patients with diabetes, the increased risk of HF hospitalisations and cardiovascular mortality with a higher extracellular volume fraction have been established (Wong et al., 2014). Moreover, in patients with diabetes, advanced glycation end product deposition, hyperinsulinaemia and endothelial dysfunction have been postulated to up‐regulate pathological cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, cardiac interstitial and perivascular fibrosis, and reduce ventricular compliance, resulting in HFpEF. In addition, lipotoxicity and ROS‐induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis observed in diabetes is associated with the development of replacement fibrosis and eventual HFrEF (Figure 1) (Paulus & Dal Canto, 2018). Therefore, reversal of the different cardiac fibrotic phenotypes may provide an alternate approach of halting the progression to HF in patients with diabetes.

4. EVIDENCE FOR SEX DIFFERENCES IN CARDIAC FIBROSIS

Although men often present with eccentric cardiac remodelling, greater cardiomyocyte size and enhanced LV fibrosis, women are more likely to develop concentric cardiac remodelling (Figure 1) (Kessler et al., 2019). This is consistent with the higher prevalence of concentric remodelling in HFpEF and eccentric remodelling in HFrEF (HF phenotypes that are more common in women and men, respectively) (Yap et al., 2019). Interestingly, the degree of collagen deposition appears to differ in men and women in various cardiovascular diseases. Women present higher collagen deposition and myocardial stiffness in atrial fibrillation (Z. Li et al., 2017), while men present with greater cardiac fibrosis in aortic stenosis (Kararigas et al., 2014). Clinical studies have yet to establish if such a distinction exists for the patient biological sex and the nature of their diabetes‐induced cardiac fibrosis. Future studies to resolve this issue, using cutting‐edge technologies such as cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, are hence warranted.

Inconsistent findings have also been reported regarding the extent of pathological cardiac fibrosis in male and female rodent models of cardiovascular disease in the presence and absence of diabetes (Table 1). Indeed, for particular models of diabetes and/or cardiovascular disease, no head‐to‐head comparisons have been conducted in male and female animals for pathological cardiac fibrosis. Moreover, for each of the animal models that have compared cardiac fibrosis between the sexes, there are only one or two prominent studies per model; the findings from these studies are summarised in Table 1. In male and female models of type 1 diabetes (T1D), whereas there have been some reports of no differences in the level of collagen deposition in the male and female heart, others have reported a slightly exaggerated cardiac fibrotic response in diabetic female male (Chandramouli et al., 2018; Tang et al., 2020). Meanwhile, a slightly faster progression of pathological cardiac fibrosis was reported in female mice through a head‐to‐head comparison between male and female T2D mice (Bowden et al., 2015). Similar comparisons between non‐diabetic male and female animal models of HFpEF and pressure overload have uncovered reduced cardiac fibrosis in female animals (Fliegner et al., 2010; Nguyen et al., 2020). However, female mice with dilated cardiomyopathy demonstrate enhanced collagen deposition and reports of the cardiac fibrotic response in male and female animals with MI are inconsistent (Cavasin et al., 2004; Dedkov et al., 2014; Tripathi et al., 2017) These studies indicate that there is a real need to continue characterisation of the potential sexual dimorphisms in the diabetic heart and, particularly, any differences in pathological cardiac fibrosis in both preclinical and clinical studies.

TABLE 1.

Sex differences in diabetic and non‐diabetic animal models of cardiovascular disease

| Animal model | Cardiac or systemic sex differences | Sex differences in cardiac fibrosis | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetic models | |||

| Streptozotocin (STZ)‐induced type 1 diabetes (T1D) |

|

|

(Chandramouli et al., 2018) |

| OVE26 T1D mice |

|

|

(Tang et al., 2020) |

| db/db T2D mice |

|

|

(Bowden et al., 2015) |

| ob/ob T2D mice |

|

|

(Manolescu et al., 2014; Won et al., 2013; Ye et al., 2017) |

| STZ + high fat diet (HFD)‐induced T2D |

|

|

(P. Habibi et al., 2016; Shin et al., 2020; Tate et al., 2019) |

| Non‐diabetic models | |||

| HFpEF |

|

|

(Nguyen et al., 2020) |

| Pressure‐overload induced by transverse aortic constriction (TAC) surgery |

|

|

(Fliegner et al., 2010) |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy |

|

|

(Tripathi et al., 2017) |

| MI/ischaemia–reperfusion |

|

Inconsistent findings:

|

(Cavasin et al., 2004; Dedkov et al., 2014) |

No head‐to‐head comparisons have been conducted between male and female animals.

Abbreviations: HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infraction; T1D, type 1 diabetes; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Similar to cardiovascular disease and HF, exacerbated risk of cardiac fibrosis in women has been associated with the onset of menopause; perhaps due in part to the loss of cardioprotection through oestrogen signalling. Using LV biopsies from healthy donors, it was identified that young women had lower protein expression of collagen type I and III, and pro‐fibrotic markers, TIMP3 and TGF‐β, compared with men of the same age range (17–40 years of age). The relative expression of these pro‐fibrotic markers was reversed in older men and post‐menopausal women (50–68 years) (Dworatzek et al., 2016). The anti‐fibrotic effects of oestrogen and its mimetics have been demonstrated using a number of ovariectomised murine models of ageing, hypertension, RAAS hyperactivity and diabetes, and is further reviewed elsewhere (Medzikovic et al., 2019). Hence, heterogeneity in cardiac remodelling in men and women may contribute to the progression of various HF phenotypes.

5. THERAPIES TARGETING CARDIAC FIBROSIS IN DIABETES‐INDUCED HEART FAILURE

Currently, patients diagnosed with diabetic cardiomyopathy and diabetes‐induced HF are concomitantly treated with HF and anti‐diabetic therapies, to separately target their diabetic and cardiovascular complications. Treatments specifically targeting cardiac fibrosis are lacking (Ritchie & Abel, 2020). Standard HF treatments [ACE inhibitors, β‐adrenoceptor antagonists, mineralocorticoid receptor (NR3C2) antagonists, a combination of an AT1 receptor antagonist and neprilysin (neutral endopeptidase; NEP) inhibitor, also referred to as an angiotensin receptor‐neprilysin inhibitor (ARNi) and AT1 receptor antagonists alone], successfully prolong survival and decrease hospitalisations for HFrEF patients, yet fail to exert similar results in patients with HFpEF and diabetes (Ponikowski et al., 2016). Notably, conventional diabetes treatments such as thiazolidinediones and sulfonylureas have been shown to further increase the risk of HF (Seferović et al., 2020).

A number of societal factors influence the way in which men and women are treated for HF. Women are less aware of their risk and symptoms for cardiovascular disease; they are less likely to be prescribed conventional HF therapies by their clinical managers and it has been suggested that they may be less compliant in taking HF medications (M. Zhao et al., 2020). Furthermore, various preclinical and clinical studies have identified sex differences in the pharmacokinetics and/or pharmacodynamics (including effects on pathological cardiac fibrosis) of standard HF treatments (summarised in Table 2). Sex differences in the effects of traditional glucose‐lowering therapies (metformin, sulfonylureas and thiazolidinediones) on blood glucose levels and myocardial energy metabolism have also been identified (Table 2). Hence, heterogeneity in the pathophysiology of diabetes‐induced HF and underlying myocardial structural changes in men and women may account for the previous lack of efficacy of traditional HF and diabetes treatments in patients. Meta‐analyses investigating the efficacy of these traditional HF and diabetes treatments in the male and female diabetic heart are warranted to determine if sexual dimorphisms exist.

TABLE 2.

Sex differences of standard anti‐diabetic and cardiovascular disease (CVD) therapies

| Sex differences in pharmacokinetics and/or pharmacodynamics | Sex differences in cardiac fibrosis | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti‐diabetic therapies | |||

| β‐Adrenoceptor antagonists |

|

ND | (Luzier et al., 1999) |

| ACE inhibitors |

|

Similar reductions in cardiac fibrosis with preventative ACE inhibitors treatment in male and female mice with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy | (Domínguez et al., 2021; Lam et al., 2019) |

| AT1 antagonists |

|

Greater reduction of cardiac fibrosis in female rats with aortic regurgitation than diseased male rats | (Lam et al., 2019; Walsh‐Wilkinson et al., 2019) |

| MR antagonists |

|

Greater reduction of cardiac fibrosis in female rats with MI than diseased male rats | (Kanashiro‐Takeuchi et al., 2009; Merrill et al., 2019) |

| ARNi |

|

Similar reductions in plasma biomarkers of cardiac fibrosis in men and women with HFpEF | (Cunningham et al., 2020; Solomon et al., 2019) |

| CVD therapies | |||

| Metformin |

|

ND | (Lyons et al., 2013) |

| Sulfonylureas |

|

ND | (Dennis et al., 2018) |

| Thiazolidinediones |

|

ND | (Dennis et al., 2018) |

Abbreviations: ARNi, combination of an AT1 receptor antagonist and neprilysin (neutral endopeptidase; NEP) inhibitor; HF, heart failure; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; MR, mineralocorticoid receptor (NR3C2); ND, not determined.

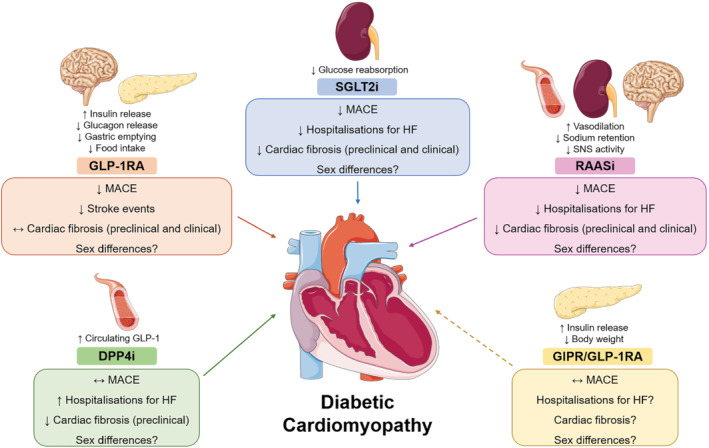

Recently, a new era of glucose‐lowering therapeutics has emerged with the introduction of sodium/glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and glucagon‐like peptide 1 (GLP‐1) receptor agonists, which not only reduce blood glucose levels but also the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in patients with diabetes (Kristensen et al., 2019; McGuire et al., 2021). The effects of these treatments on cardiac fibrosis in the male and female diabetic heart, alongside other incretin‐based mimetics [dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) inhibitors and dual gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) receptor/GLP‐1 receptor agonists, RAAS inhibitors and therapies in preclinical development, will be covered in the following sections (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Mechanism of action of newer glucose‐lowering therapies and renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system inhibitors (RAASi), and their effects on the failing, diabetic heart. Target organs and actions of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors (DPP4i), glucagon‐like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP‐1RAs), sodium‐glucose co‐transporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), dual gastric inhibitory polypeptide receptor (GIPR)/ GLP‐1RAs and RAASi, are summarised above the coloured boxes. Effects of these treatments on the diabetic heart are summarised within the coloured boxes. Solid arrows indicate that effects of treatments on cardiovascular events and/or cardiac fibrosis are known. Dashed arrows indicate that the effects of the treatments on cardiovascular events and cardiac fibrosis are unknown. HF, heart failure; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event. See text for references. Schema created using modifications to images provided by Servier Medical Art by Servier (https://smart.servier.com/), licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/)

5.1. RAAS inhibitors

Activation of the RAAS has been implicated in the development of HF through pressure overload induced by vasoconstriction, increased sodium retention and enhanced sympathetic nervous activity via activation of the AT1 receptor (Ames et al., 2019). RAAS inhibitors incorporate a number of classical renal and HF treatments that target the RAAS, including ACE inhibitors, AT1 and mineralocorticoid antagonists (Ames et al., 2019). The landmark HOPE study reported significant reductions in the incidence of MACE outcomes, all‐cause mortality and new diagnosis of diabetes with the ACE inhibitor, ramipril. Further, subgroup analyses demonstrated that ramipril reduced MACE outcomes regardless of diabetic status or sex (Yusuf et al., 2000). Through further head‐to‐head comparisons, ACE inhibitors have been shown to be more effective at reducing MACE outcomes, all‐cause and cardiovascular mortality rates and incidence of MI than AT1 antagonists, whereas both therapies significantly reduce HF incidence in patients with diabetes (Cheng et al., 2014). Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists similarly reduce incidence of MACE outcomes, hospitalisations for HF and cardiovascular mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease and diabetes, although the risk of hyperkalaemia and acute renal insufficiency appears to be elevated with treatment (Cooper et al., 2017).

Modest to large attenuations in cardiac fibrosis with have been reported with ACE inhibitors, AT1 antagonists or mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in male diabetic rodent models (Liu et al., 2018; V.P. Singh et al., 2008; Tsutsui et al., 2007). The protection against cardiac fibrosis has been attributed to reductions in TGF‐1β/“small” mothers against decapentaplegic (SMAD)3 signalling, cardiac inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress, and is further reviewed elsewhere (Tuleta & Frangogiannis, 2021). In regard to cardiac function, one study reported attenuations in diastolic dysfunction with AT1 antagonist treatment in male diabetic mice (Tsutsui et al., 2007), whereas another found that ACE inhibitors or AT1 antagonists preserved both systolic and diastolic function in male diabetic mice, although cardiac fibrosis was not inhibited (Thomas et al., 2013). Similarly, ACE inhibitors in female diabetic mice improved diastolic function, through reductions in enhanced deceleration times and LV end diastolic pressure (Huynh et al., 2012).

Meanwhile, RAAS inhibition by mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, AT1 antagonists and ACE inhibitors in clinical studies has been associated with reductions in markers of fibrosis (extracellular volume and LV mass index), suggesting alterations in the level of cardiac remodelling in T2D patients with a range of co‐morbidities including microalbuminuria, hypertension and high CVD risk (Brandt‐Jacobsen et al., 2021; Fogari et al., 2012; Swoboda et al., 2017). Excitingly, recent data from the HOMAGE clinical trial reported reductions in serum procollagen type‐I C‐terminal pro‐peptide but not serum procollagen type‐III N‐terminal pro‐peptide, in patients at high risk of HF randomised to the mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, spironolactone (Cleland et al., 2021). However, less than half of the patients in the mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist and placebo arms were diagnosed with diabetes, and no subgroup analyses were conducted to elucidate whether these effects were reflected specifically in the diabetic population.

Although RAAS inhibitors have been utilised for a number of years, potential sex differences of these therapies on MACE and HF outcomes have yet to be fully established, due to the underrepresentation of female patients in clinical trials. The contradictory results from clinical studies on the benefits of RAAS inhibitors for hospitalisations of HF and mortality outcomes in men and women with HF have been recently reviewed (Nicolaou, 2021). With respect to pharmacokinetics, ACE inhibitors and AT1 antagonists can achieve higher maximum plasma concentrations in women compared with men (~2.5‐fold difference), suggesting that sex differences in their effects are likely to exist (Table 2) (Lam et al., 2019). Postulated mechanisms for this apparent discrepancy in plasma concentrations have been attributed to the smaller body composition, slower drug clearance and differences in the expression and activity of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes observed in women (Lam et al., 2019). In regard to the anti‐fibrotic effects of RAAS inhibitors, previous literature using preclinical models has demonstrated that AT1 antagonist and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist‐induced reductions in cardiac fibrotic markers were greater in female rats with aortic regurgitation or MI, respectively, compared with diseased male rats (Table 2) (Kanashiro‐Takeuchi et al., 2009; Walsh‐Wilkinson et al., 2019). Furthermore, pretreatment with an ACE inhibitor appears to exert similar cardiac anti‐fibrotic effects in male and female mice with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (Table 2) (Domínguez et al., 2021). Whether these sex‐specific effects are translated to differences in diabetes‐related HF remains to be seen. Promisingly, although head‐to‐head comparisons have yet to be completed, ACE inhibitors have demonstrated robust attenuations in cardiac fibrosis in studies that separately used male and female diabetic rodents (Huynh et al., 2012; V. P. Singh et al., 2008).

Although RAAS inhibitors demonstrate robust anti‐fibrotic effects in patients and animals with diabetes, the contribution of these favourable changes in the extracellular matrix to overall protection against the development of HF remains unclear, especially in male and female patients with diabetes (Tuleta & Frangogiannis, 2021). Some sex differences in the pharmacokinetics and effects on pathological cardiac fibrosis in non‐diabetic animal models have been identified with RAAS inhibitor treatment. However, reports of the effects on diabetes‐induced cardiac fibrosis have been lacking. Additionally, as RAAS inhibitors do not specifically target hyperglycaemia in patients with diabetes, their ability to restore a physiological milieu is likely limited and perhaps therapeutic approaches that target both the HF and underlying cause (poor glycaemic control), are warranted in diabetic HF.

5.2. SGLT2 inhibitors

The low affinity but high capacity SGLT2 accounts for approximately 90% of glucose reabsorption at the S1‐S2 segments of the proximal renal convoluted tubules in the kidney (Alexander, Kelly, et al., 2021; Kanai et al., 1994). SGLT2 inhibitors block the reabsorption of glucose and sodium into the renal tubular cells and the subsequent passive transport of glucose into the blood via glucose transporter 2 (GLUT2), hence reducing blood glucose levels in an insulin‐independent manner (Wright et al., 2011). It was through the landmark EMPA‐REG OUTCOME clinical trial where reductions in three‐point MACE outcomes (composite of cardiovascular death, non‐fatal stroke and non‐fatal MI) and hospitalisations for HF were first reported in patients with T2D who were at high risk of cardiovascular events (McGuire et al., 2021). Since then, empagliflozin, dapagliflozin, canagliflozin and ertugliflozin, the newer‐generation of SGLT2 inhibitors have demonstrated overall reductions of approximately 10% and 22% for MACE outcomes and hospitalisations for HF/cardiovascular death, respectively, in patients with diabetes and at a high risk of, or with established, CVD (McGuire et al., 2021). A recent meta‐analysis has further elucidated that SGLT2 inhibitors appears to exert reductions in HF hospitalisations and all‐cause mortality in T2D patients regardless of a baseline HF diagnosis (Qiu et al., 2021). However, MACE outcomes were found to be only significantly reduced in T2D patients without HF (Qiu et al., 2021). Surprisingly, in patients with HFrEF, empagliflozin and dapagliflozin treatment has also been associated with reductions in hospitalisations for HF regardless of whether there is a concomitant diabetes diagnosis (McMurray et al., 2019; Packer et al., 2020). Further subgroup analyses from clinical trials investigating canagliflozin and a dual SGLT1/SGLT2 inhibitor, sotagliflozin, and a recent large‐scale clinical trial investigating empagliflozin (EMPEROR‐Preserved), have reported similar beneficial effects in patients with HFpEF (Anker et al., 2021; Packer, 2021).

A number of preclinical studies have investigated the impact of SGLT2 inhibition (particularly by dapagliflozin and empagliflozin) on pathological cardiac remodelling and function in animal models of diabetes. Indeed, in cardiomyopathy induced by diabetes combined with angiotensin II infusion in male db/db mice (a genetic model in which leptin receptors do not function properly and used as spontaneous T2D model), dapagliflozin attenuated each of increased LV collagen deposition, collagen synthesis and collagen I gene expression (Arow et al., 2020). Similarly, empagliflozin treatment in female db/db mice also significantly reduced cardiac interstitial fibrosis (J. Habibi et al., 2017). The postulated mechanisms by which SGLT2 inhibitors exert their anti‐fibrotic effects have been attributed to reductions in TGF‐β1/SMAD signalling and increases in the phosphorylation of SMAD7 (a negative regulator of this pathway), as well as attenuations in cardiac endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition via up‐regulation of AMP‐activated protein kinase (AMPK) phosphorylation (C. Li et al., 2019; Tian et al., 2021). Alongside the reductions in pathological cardiac fibrosis, empagliflozin and dapagliflozin have reportedly improved systolic and diastolic function in male and female rodent models of diabetic cardiomyopathy, as measured by increases in LVEF, fractional shortening (FS) and the early‐to‐late diastolic filling (E/A) ratio (J. Habibi et al., 2017; C. Li et al., 2019; Tian et al., 2021).

Interestingly, SGLT2 inhibitors also limit pathological cardiac remodelling and cardiac dysfunction in preclinical male models of other, non‐diabetic cardiac pathologies including MI and hypertension and an aged, female murine model of HFpEF (T.‐M. Lee et al., 2017; H.‐C. Lee et al., 2019; Shi et al., 2019; Withaar et al., 2021). Contrastingly, in a female pig model of HFpEF, Masson's trichrome staining (a histological marker of fibrosis) of different LV regions identified that dapagliflozin treatment only reduced HFpEF‐associated collagen deposition in the mid‐wall region and not the sub‐endocardium nor sub‐epicardium (N. Zhang et al., 2019). Furthermore, minimal reductions in cardiac dysfunction (enhanced LV filling pressure and prolonged deceleration time) were reported with dapagliflozin treatment in HFpEF pigs, with the exception of reductions in elevated isovolumic relaxation time (IVRT), a marker of diastolic function (N. Zhang et al., 2019).

Profound SGLT2 inhibition‐induced reductions in pathological LV remodelling have also been reported in humans. Empagliflozin treatment significantly decreased activity and altered morphology of activated myofibroblasts, and reduced expression of pro‐fibrotic markers (α‐smooth muscle actin (α‐SMA), fibronectin, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), collagen I and II) and regulators of the extracellular matrix (i.e. MMP1, MMP2 and TIMP2) in isolated human atrial cardiac fibroblasts (Kang et al., 2020). However, 6‐month empagliflozin treatment in patients with T2D failed to alter elevations in extracellular volume and reductions in LVEF (Hsu et al., 2019). Given the difficulties in measuring cardiac fibrosis in patients, a number of clinical studies have measured LV mass and LV end systolic and diastolic volumes as markers of general cardiac remodelling. Indeed, empagliflozin and dapagliflozin have promisingly both been shown to reduce these markers of cardiac remodelling in various patient populations: HFrEF patients with and without diabetes and T2D patients with LV hypertrophy or coronary artery disease (Brown et al., 2020; M.M.Y. Lee et al., 2021; Santos‐Gallego et al., 2021; Verma et al., 2019). Hence, further trials are required to ascertain whether anti‐fibrotic and remodelling effects associated with SGLT2 inhibitors are also observed in HFpEF patients.

Whether the cardioprotective nature of SGLT2 inhibitors differ in men and women remains unresolved. Contradictory results from meta‐analyses investigating potential sex‐differences of SGLT2 inhibitors on MACE and safety outcomes have been reported, with some analyses finding greater cardioprotection in men whereas others found no differences between the sexes (Raparelli et al., 2020; A.K. Singh & Singh, 2020). These discrepancies can be attributed to the under representation of women in these large‐scale clinical trials and hence any true divergence in effects between men and women cannot be uncovered. A recent post hoc analysis of the EMPA‐REG clinical trial has discerned that the risk of cardiovascular death differs with empagliflozin treatment based on three different patient phenotypes. The risk of cardiovascular death and hospitalisations for HF was moderately high in one cluster of patients who were more likely to be women without coronary artery disease, but with cerebrovascular and peripheral arterial disease (Sharma, Ofstad, et al., 2021). Potential sex differences in the anti‐fibrotic effects of SGLT2 inhibitors have yet to be investigated. Future studies should actively include equal numbers of male and female participants to conduct head‐to‐head comparisons which will further elucidate if there are any sexual dimorphisms associated with SGLT2 inhibitors in diabetes‐induced cardiac fibrosis and HF.

5.3. GLP‐1 receptor agonists

GLP‐1 agonists mimic the effects of endogenous GLP‐1, a gastrointestinal incretin released from L‐cells of the distal small intestinal mucosa, that slows down gastric emptying, increases secretion of postprandial insulin, induces satiety and reduces glucagon secretion (Smelcerovic et al., 2019). These effects are mediated through activation of the GLP‐1 receptor, a 7‐transmembrane spanning, class B GPCR, that predominantly couples to the Gαs subunit to activate cAMP (Alexander, Christopoulos, et al., 2021; Malik & Li, 2021). GLP‐1 receptor is most notably found in the pancreatic β‐islet cells where insulin is produced, but the receptor is also expressed in the pancreatic δ cells, lung, stomach, kidney, hypothalamus and heart, particularly in the atria, sinoatrial myocytes and human, but not rodent, ventricular myocytes (Baggio et al., 2018; Cantini et al., 2016). Currently, four GLP‐1 agonists based on the structure of endogenous GLP‐1 (subcutaneous formulations of liraglutide, dulaglutide, albiglutide and semaglutide) have demonstrated profound reductions in three‐point MACE and cardiovascular mortality (12% risk reduction for both outcomes), and a 16% reduction in risk of stroke outcomes in patients with T2D; findings that are particularly pertinent in patients with established atherosclerotic disease (Kristensen et al., 2019). Surprisingly, exendin‐4‐based GLP‐1 agonists, such as lixisenatide and exenatide, and the only‐available oral formulation of a GLP‐1 agonist (oral semaglutide) have failed to exert similar effects (Kristensen et al., 2019).

Several studies have examined the impact of GLP‐1 agonists, particularly liraglutide, on cardiac remodelling and LV dysfunction in animal studies, in the presence of diabetes or obesity. Up‐regulation of cardiac markers of fibrosis, such as serum and myocardial hydroxyproline content and collagen degradation enzymes (MMP1 and MMP9), associated with diabetes in male mice were all attenuated with liraglutide treatment (L. Zhao et al., 2019). These attenuations in pathological cardiac remodelling with GLP‐1 agonism have been associated with the activation of the ERK/NF‐ĸB, PI3K/Akt and AMPK signalling pathways in isolated mouse cardiac fibroblasts, and human and rat cardiomyocytes incubated with glucose and/or angiotensin II (R. Li et al., 2019; Wang, Zhang, et al., 2016). Contrastingly, lack of liraglutide‐associated attenuations in cardiac fibrosis were reported in male genetically obese pre‐diabetic rats, where increased perivascular collagen deposition, measured by Azan‐Mallory staining, was not down‐regulated with liraglutide treatment (Sukumaran et al., 2020). Similar contradictory results for cardiac function have been determined for male rodent models of diabetes whereby some reported that liraglutide administration did not improve LVEF and fractional shortening (Sukumaran et al., 2020), whereas others found that liraglutide restored cardiac function through elevations in LVEF and the E/A ratio, as well as attenuations in enhanced LV end diastolic pressure and the E/e’ (early mitral inflow velocity and mitral annular early diastolic velocity) (Almutairi et al., 2021; L. Zhao et al., 2019).

Many more studies have investigated the impact of GLP‐1 agonists on cardiac remodelling and dysfunction in animal models without diabetes, including models of MI, ageing and HF. Activation of the GLP‐1 receptor, via liraglutide and exendin‐4, has been shown to significantly reduce cardiac interstitial collagen deposition and expression of a number of pro‐fibrotic markers (CTGF, collagen I, III, and IV, and fibronectin) in male and female mouse models of MI, and an aged female murine model of HFpEF (Robinson et al., 2015; Wang, Ding, et al., 2016; Withaar et al., 2021). However, similar to what was observed in diabetic animals, discrepancies in the anti‐fibrotic effects of GLP‐1 agonists have been reported where there were no significant decreases in cardiac fibrosis with treatment in male animal models of MI or HF (Kyhl et al., 2017; Shiraki et al., 2019). Nevertheless, the mechanisms by which GLP‐1 agonists exert their anti‐fibrotic effects in these non‐diabetic settings have been attributed to reductions in myofibroblast populations and SMAD2/3 phosphorylation, and increases in MAPK kinase 3/Akt‐1 signalling (Du et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2019). Unfortunately, where GLP‐1 agonists have been reported to exert cardiac anti‐fibrotic effects in non‐diabetic phenotypes, there has been little to no subsequent reversals in cardiac dysfunction (Kyhl et al., 2017; Shiraki et al., 2019; Withaar et al., 2021).

Few studies have investigated the impact of GLP‐1 agonists on cardiac remodelling in humans, although one study conducted with T2D patients, who had been treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute MI, demonstrated a reduction in LV mass index with liraglutide treatment (Nozue et al., 2016). However, reported differences in LV mass index between the liraglutide and standard treatment groups were also observed at baseline, and other measures of LV remodelling (end‐diastolic volume index, end‐systolic volume index and LVEF), were not different between liraglutide and standard treatments (Nozue et al., 2016). Unusually, in another study, liraglutide treatment in T2D patients significantly reduced LV diastolic and systolic functional parameters including transmitral early peak velocity (E), the E/A ratio, stroke volume and LVEF compared with placebo (Bizino et al., 2019). However, due to liraglutide‐associated increases in heart rate, cardiac output and cardiac index were not different between the two treatment groups (Bizino et al., 2019). Meanwhile, in patients with non‐ST‐segment elevation MI (NSTEMI), liraglutide administration increased LVEF to a greater extent compared with the control group, independent of diabetic status and impaired systolic function (LVEF < 50%) (Chen et al., 2016). Hence, due to the disparities in the effects of GLP‐1 agonists in preclinical and clinical studies, more consistent approaches must be adopted to ensure that the true effect of these therapies on animal and human cardiac function and structure can be determined.

Similar to SGLT2 inhibitors, potential sex differences of GLP‐1 agonists on MACE outcomes and cardiac fibrosis have yet to be fully elucidated. Analysis of large‐scale clinical trials have reported no differences in respect to reductions in three‐point MACE with GLP‐1 agonists in men and women (A.K. Singh & Singh, 2020). Contrastingly, another study determined that GLP‐1 agonists were more effective at reducing the risk of adverse cardiovascular events compared with sulfonylureas in women more so than men (Raparelli et al., 2020). However, women were more likely to experience gastrointestinal side effects (a common adverse effect with GLP‐1 agonists) (Raparelli et al., 2020). These studies provide preliminary insights into how GLP‐1 agonists may provide varying benefits in men and women. Future studies should further scrutinise the potential for sexual dimorphisms with GLP‐1 agonism, with a focus particularly on cardiac remodelling in the male and female diabetic heart.

5.4. DPP4 inhibitors

DPP4 rapidly cleaves endogenous GLP‐1, hence inhibiting activity at the GLP‐1 receptor; inhibitors of DPP4 arrest proteolysis of endogenous GLP‐1 (Alexander, Fabbro, et al., 2021; Gallwitz, 2019). Although GLP‐1 agonists induce greater GLP‐1‐like effects due to their extended half‐life compared with native GLP‐1 and exhibit enhanced glucose‐lowering properties, DPP4 inhibitors are better tolerated by patients (Dungan, 2016). Unlike SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP‐1 agonists, DPP4 inhibitors (sitagliptin, saxagliptin, alogliptin and linagliptin) did not reduce MACE outcomes in patients with diabetes, with saxagliptin and alogliptin actually increasing risk of HF hospitalisations, prompting the Food and Drug Administration to include a warning for HF on the labels of both these treatments in 2016 (Food and Drug Administration, 2016; Gallwitz, 2019).

In contrast to the controversial results observed in the large‐scale clinical trials, DPP4 inhibitor treatment in animal models have demonstrated predominantly cardioprotective effects, especially through attenuations in pathological cardiac fibrosis. Although there are conflicting reports regarding the efficacy of DPP4 inhibitors, in both non‐diabetic (Esposito et al., 2017; Yamaguchi et al., 2019) and diabetic male rodent models of HF (Al‐Damry et al., 2018), DPP4 inhibitors have been shown to significantly reduce cardiac fibrosis with modest improvements in cardiac function. These attenuations in cardiac fibrosis have been associated with the reduction in p38 MAPK phosphorylation, TGF‐β1/SMAD3 signalling and MMP2 and MMP9 activity (Al‐Damry et al., 2018; Esposito et al., 2017; Yamaguchi et al., 2019). Meanwhile, in a non‐HF obesity model using female mice, significant but moderate reductions in cardiac interstitial fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction suggest similar cardioprotective effects across the sexes (Aroor et al., 2017).

Little research has been conducted in humans to elucidate the effects of DPP4 inhibitors on cardiac fibrosis. In vitro experiments using primary human valvular interstitial cells demonstrated attenuations in gene expression of pro‐fibrotic genes (fibronectin 1 and collagen I) with evogliptin treatment (Choi et al., 2021). However, further investigation is required to confirm whether DPP4 inhibitors exert anti‐fibrotic effects in the human heart and if there are any sex‐specific differences associated with treatment. Although sex‐based analyses in the major DPP4 inhibitor clinical trials have not been conducted, a population‐based analysis reported similar effects on MACE outcomes in men and women (Raparelli et al., 2020). Given the neutral effects on MACE outcomes and possible enhanced risk of HF, DPP4 inhibitors are not a promising candidate for widespread use as a treatment for diabetes‐induced cardiac fibrosis and HF. Furthermore, it has been noted that DPP4 inhibitors can activate stromal cell‐derived factor‐1 (SDF‐1), which in turn may increase the transformation of mesenchymal stem cells to fibroblasts and thus exacerbate cardiac fibrosis (Packer, 2018).

5.5. Dual GLP‐1/GIP receptor agonists

Another incretin hormone involved in the regulation of nutrient intake and postprandial metabolic homeostasis is the glucose‐dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP) (Holst & Rosenkilde, 2020). Much like GLP‐1, GIP receptor is involved in stimulating the release of insulin through activation of the GIP receptor, although infusion of GIP in patients with T2D failed to stimulate the postprandial insulin response and inhibit food intake (Alexander, Christopoulos, et al., 2021; Holst & Rosenkilde, 2020). Paradoxically, both agonism and antagonism of the GIP receptor stimulates weight loss effects, and dual GIP receptor/GLP‐1 agonism exerts even more profound glycaemic and body weight reductions compared with activation of the GLP‐1 receptor alone (Campbell, 2021). Hence, dual GIP/GLP‐1 receptor agonists may provide an exciting alternate approach for the reduction in co‐morbidities, such as diabetes and obesity, associated with the development of HF.

Currently, whether dual action at the GIP receptor and GLP‐1 receptor confers reductions in MACE and cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes is being investigated in two large‐scale clinical trials. The results from the first of these trials, SURPASS‐4 trial (NCT03730662), have recently been published, with tirzepatide demonstrating non‐inferiority but not superiority in the reduction of four‐point MACE outcomes (hospitalisation for unstable angina in addition to three‐point MACE) compared with insulin glargine (Del Prato et al., 2021). The recently commenced SURPASS CVOT (NCT04255433) trial is set to be completed in 2024, which will further elucidate any associations between tirzepatide and reductions in the risk of cardiovascular events (Min & Bain, 2021). Although the effects of GIP receptor/GLP‐1 receptor agonists on cardiac fibrosis have yet to be determined, GIP receptor activation through an infusion of GIP in a murine model of atherosclerosis attenuated the hyperactivated cardiac interstitial fibrosis response (Hiromura et al., 2016). In addition, sex‐differences in the effects of dual GIP receptor/GLP‐1 receptor activation also remains to be seen. Triple agonism of the GLP‐1/GIP/glucagon receptors however has a similar reduction in body weight, food intake and dyslipidaemia in male and female obese mice, whereas blood glucose and steatohepatitis were more greatly reduced in treated male and female obese mice, respectively (Jall et al., 2017).

5.6. Relaxin: A potential anti‐fibrotic treatment in preclinical development

Relaxin, a reproductive hormone which was initially investigated for its potent vasodilatory and protective effects in women during pregnancy, has since been lauded for its reductions in inflammation, fibrosis (including cardiac fibrosis) and increases in angiogenesis via activation of the relaxin family peptide receptor 1 (RXFP1) (Sarwar et al., 2017). Although large‐scale clinical trials investigating the impact of relaxin or its mimetics in patients with diabetes and on cardiac fibrosis have not been conducted, short‐term relaxin treatment has been shown to significantly reduce all‐cause and cardiovascular‐related deaths, as well as hospitalisations for HF or renal failure in patients with acute HF (Fang et al., 2017).

Relaxin‐induced attenuations in cardiac fibrosis have been reported in male and female animal models of diabetes, mainly through reductions in TGF‐β/SMAD2/3 signalling and fibroblast to myofibroblast transition, and changes in MMP expression (Samuel et al., 2008; X. Zhang et al., 2017). However, in another study using male diabetic mice, treatment with a recombinant human form of relaxin 2, serelaxin, failed to alter up‐regulated interstitial fibrosis and gene expression pro‐fibrotic markers such as CTGF and TGF‐β, although other cardiac remodelling pathologies ‐ cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and apoptosis ‐ were significantly attenuated with treatment (Ng et al., 2017). Interestingly, it has been suggested that relaxin provides greater protection against cardiac fibrosis in the male heart, whereas the anti‐fibrotic effects of relaxin may be masked due to other underlying protective factors, such as oestrogen, in the premenopausal female heart (Samuel et al., 2017). Given the short half‐life of relaxin, the slow progression to clinical trials and its costliness to produce, relaxin is not as an attractive anti‐fibrotic therapeutic compared with the newer class of glucose‐lowering treatments (Fang et al., 2017).

6. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE CONSIDERATIONS

Historically, treatments specifically targeting diabetic cardiomyopathy, and the associated cardiac fibrosis, have been sorely lacking. However, with the introduction and more widespread use of newer classes of glucose‐lowering treatments such as SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP‐1 agonists, alternate and more efficacious approaches of targeting diabetes‐induced HF have emerged. SGLT2 inhibitors in particular, robustly attenuate cardiac remodelling and dysfunction commonly associated with diabetes, and of the available anti‐diabetic therapies, have been the most successful at reducing this pathology and HF in a number of different patient populations. However, there is still much that still needs to be clarified. The mechanism by which SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP‐1 agonists exert reductions in MACE and/or hospitalisations for HF still remains a mystery, especially given that SGLT2 is not expressed in the heart (Wright et al., 2011). Whether these benefits are secondary to, or independent of, any improvements in cardiac fibrosis are yet to be fully resolved. Current knowledge of the anti‐fibrotic effects of newer classes of glucose‐lowering therapies in clinical settings has often been uncovered using indirect measures of cardiac fibrosis, such as LV mass index and plasma concentrations of fibrotic markers. Future clinical studies investigating these treatments should look towards adopting more accurate, high‐resolution and direct measures of cardiac fibrosis through CMR imaging. Similarly, many questions are yet to be answered in regard to the potential cardioprotective effects of dual GIP receptor/GLP‐1 receptor agonists and how DPP4 inhibitors only appear to exert protective effects in animals not humans with diabetes. Traditional CVD treatments such as RAAS inhibitors provide an alternate method of attenuating cardiac pathologies in patients with diabetes. Unfortunately, they do not target hyperglycaemia in patients with diabetes, which is the underlying cause for the progression to diabetic cardiomyopathy and eventual HF.

Another factor often overlooked in preclinical and clinical studies is the potential sex differences of treatments in the diabetic heart. Although sexual dimorphisms in diabetes and CVD presentation are widely accepted in the medical and research communities, treatment for these conditions remains the same regardless of sex, which can be partially attributed to how female animal models and women continue to be underutilised in studies (Ramirez et al., 2017). A concerted effort has been made to include more female animals in preclinical studies and enforcing subgroup analyses based on sex and gender in clinical research through changes in policy by the National Institute of Health (NIH) (Beery, 2018). Unfortunately, the NIH failed to stipulate that sex‐based analysis should be a requirement in preclinical studies (Beery, 2018).

Currently, it is difficult to conclude whether the next‐generation of anti‐diabetic treatments exert distinct cardioprotective effects, both against progression of cardiac fibrosis as well as heart failure, in men compared with women. If future large‐scale cardiovascular outcome trials include equal numbers of male and female diabetic participants to conduct sub‐group analyses based on sex, these questions may finally be answered. In addition, given the increased risk of cardiovascular disease and HF in post‐menopausal women compared with men of the same age bracket, subgroup analyses based on menopausal status, particularly women with premature menopause, should also be considered. Interestingly, recent meta‐analyses have compared the cardioprotective effects and risk of adverse event outcomes with SGLT2 inhibitors, GLP‐1 agonists and DPP4 inhibitors use from large‐scale clinical trials (Kanie et al., 2021; Pan et al., 2020). Although the findings from these analyses reinforce the nature of the cardioprotective effects of these contemporary anti‐diabetic therapies (GLP‐1 agonists reduce the risk of stroke and MI, particularly in patients without HF; SGLT2 inhibitors reduce the risk of HF hospitalisations and all‐cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients both with and without baseline HF; DPP4 inhibitors exert very few cardioprotective effects) (Kanie et al., 2021; Pan et al., 2020), direct comparisons of these treatments in men and women with diabetes and/or baseline HF may provide robust evidence for potential sex‐specific differences in their effects. Furthermore, the prospect of combination therapy in diabetic patients across the sexes, particularly the combination of SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP‐1 agonists, must also be considered in future clinical trials. A recent observational study identified that the addition of SGLT2 inhibitors to baseline GLP‐1 agonist therapy exerted additive benefits in the reduction of MACE outcomes and HF hospitalisations compared with add‐on treatment with sulfonylureas (Dave et al., 2021), highlighting another possible way by which HF and diabetic complications can be further reduced. However, it must be noted that subgroup analyses based on sex were not conducted in this study (Dave et al., 2021). Similarly, it is imperative that future preclinical studies also include both male and female animals to compare not only systemic, but cardiac structural and subcellular, changes associated with the aforementioned anti‐hyperglycaemic treatments. It is through these steps that there will be greater understanding of how therapies targeting diabetes, cardiac fibrosis and/or HF affect patients, not only in the context of the range of co‐morbidities and HF phenotypes, but across the sexes. This will enable the development of more personalised and efficacious treatment approaches that can be recommended to ameliorate diabetes and cardiovascular disease complications (including cardiac fibrosis) across the full spectrum and different patient subsets.

6.1. Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key protein targets and ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY http://www.guidetopharmacology.org and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2021/22 (Alexander, Christopoulos, et al., 2021; Alexander, Fabbro, et al., 2021; Alexander, Kelly, et al., 2021).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.S. drafted the manuscript. All authors edited and approved the final manuscript (A.S., M.J.D., and R.R.).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have nothing to disclose.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia (Project Grant ID1158013 to RHR and MJD). AS is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program scholarship. Open access publishing facilitated by Monash University, as part of the Wiley ‐ Monash University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Sharma, A. , De Blasio, M. , & Ritchie, R. (2023). Current challenges in the treatment of cardiac fibrosis: Recent insights into the sex‐specific differences of glucose‐lowering therapies on the diabetic heart: IUPHAR Review 33. British Journal of Pharmacology, 180(22), 2916–2933. 10.1111/bph.15820

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article because no new data were created or analysed in this study.

REFERENCES

- al‐Damry, N. T. , Attia, H. A. , al‐Rasheed, N. M. , al‐Rasheed, N. M. , Mohamad, R. A. , al‐Amin, M. A. , Dizmiri, N. , & Atteya, M. (2018). Sitagliptin attenuates myocardial apoptosis via activating LKB‐1/AMPK/Akt pathway and suppressing the activity of GSK‐3β and p38α/MAPK in a rat model of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 107, 347–358. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.07.126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S. P. , Christopoulos, A. , Davenport, A. P. , Kelly, E. , Mathie, A. , Peters, J. A. , Veale, E. L. , Armstrong, J. F. , Faccenda, E. , Harding, S. D. , Pawson, A. J. , Southan, C. , Davies, J. A. , Abbracchio, M. P. , Alexander, W. , Al‐hosaini, K. , Bäck, M. , Barnes, N. M. , Bathgate, R. , … Ye, R. D. (2021). THE CONCISE GUIDE TO PHARMACOLOGY 2021/22: G protein‐coupled receptors. British Journal of Pharmacology, 178(S1), S27–S156. 10.1111/bph.15538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S. P. , Fabbro, D. , Kelly, E. , Mathie, A. , Peters, J. A. , Veale, E. L. , Armstrong, J. F. , Faccenda, E. , Harding, S. D. , Pawson, A. J. , Southan, C. , Davies, J. A. , Boison, D. , Burns, K. E. , Dessauer, C. , Gertsch, J. , Helsby, N. A. , Izzo, A. A. , Koesling, D. , … Wong, S. S. (2021). THE CONCISE GUIDE TO PHARMACOLOGY 2021/22: Enzymes. British Journal of Pharmacology, 178(S1), S313–S411. 10.1111/bph.15542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S. P. , Kelly, E. , Mathie, A. , Peters, J. A. , Veale, E. L. , Armstrong, J. F. , Faccenda, E. , Harding, S. D. , Pawson, A. J. , Southan, C. , Davies, J. A. , Amarosi, L. , Anderson, C. M. H. , Beart, P. M. , Broer, S. , Dawson, P. A. , Hagenbuch, B. , Hammond, J. R. , Inui, K.‐I. , … Verri, T. (2021). THE CONCISE GUIDE TO PHARMACOLOGY 2021/22: Transporters. British Journal of Pharmacology, 178(S1), S412–S513. 10.1111/bph.15543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almutairi, M. , Gopal, K. , Greenwell, A. A. , Young, A. , Gill, R. , Aburasayn, H. , al Batran, R. , Chahade, J. J. , Gandhi, M. , Eaton, F. , Mailloux, R. J. , & Ussher, J. R. (2021). The GLP‐1 receptor agonist liraglutide increases myocardial glucose oxidation rates via indirect mechanisms and mitigates experimental diabetic cardiomyopathy. The Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 37, 140–150. 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.02.098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames, M. K. , Atkins, C. E. , & Pitt, B. (2019). The renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system and its suppression. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 33, 363–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anker, S. D. , Butler, J. , Filippatos, G. , Ferreira, J. P. , Bocchi, E. , Böhm, M. , Brunner–la Rocca, H. P. , Choi, D. J. , Chopra, V. , Chuquiure‐Valenzuela, E. , Giannetti, N. , Gomez‐Mesa, J. E. , Janssens, S. , Januzzi, J. L. , Gonzalez‐Juanatey, J. R. , Merkely, B. , Nicholls, S. J. , Perrone, S. V. , Piña, I. L. , … Packer, M. (2021). Empagliflozin in heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. The New England Journal of Medicine, 385, 1451–1461. 10.1056/NEJMoa2107038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroor, A. R. , Habibi, J. , Kandikattu, H. K. , Garro‐Kacher, M. , Barron, B. , Chen, D. , Hayden, M. R. , Whaley‐Connell, A. , Bender, S. B. , Klein, T. , Padilla, J. , Sowers, J. R. , Chandrasekar, B. , & DeMarco, V. G. (2017). Dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 (DPP‐4) inhibition with linagliptin reduces western diet‐induced myocardial TRAF3IP2 expression, inflammation and fibrosis in female mice. Cardiovascular Diabetology, 16, 61. 10.1186/s12933-017-0544-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arow, M. , Waldman, M. , Yadin, D. , Nudelman, V. , Shainberg, A. , Abraham, N. G. , Freimark, D. , Kornowski, R. , Aravot, D. , Hochhauser, E. , & Arad, M. (2020). Sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor dapagliflozin attenuates diabetic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovascular Diabetology, 19, 7. 10.1186/s12933-019-0980-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggio, L. L. , Yusta, B. , Mulvihill, E. E. , Cao, X. , Streutker, C. J. , Butany, J. , Cappola, T. P. , Margulies, K. B. , & Drucker, D. J. (2018). GLP‐1 receptor expression within the human heart. Endocrinology, 159, 1570–1584. 10.1210/en.2018-00004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beery, A. K. (2018). Inclusion of females does not increase variability in rodent research studies. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 23, 143–149. 10.1016/j.cobeha.2018.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizino, M. B. , Jazet, I. M. , Westenberg, J. J. M. , van Eyk, H. J. , Paiman, E. H. M. , Smit, J. W. A. , & Lamb, H. J. (2019). Effect of liraglutide on cardiac function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Randomized placebo‐controlled trial. Cardiovascular Diabetology, 18, 55. 10.1186/s12933-019-0857-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden, M. A. , Tesch, G. H. , Julius, T. L. , Rosli, S. , Love, J. E. , & Ritchie, R. H. (2015). Earlier onset of diabesity‐induced adverse cardiac remodeling in female compared to male mice. Obesity, 23, 1166–1177. 10.1002/oby.21072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt, B. , Coats, A. J. , Tsutsui, H. , Abdelhamid, M. , Adamopoulos, S. , Albert, N. , Anker, S. D. , Atherton, J. , Böhm, M. , Butler, J. , & Drazner, M. H. (2021). Universal definition and classification of heart failure: A report of the Heart Failure Society of America, heart failure Association of the European Society of cardiology, Japanese heart failure society and writing Committee of the Universal Definition of heart failure. Journal of Cardiac Failure, 27, 387–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt‐Jacobsen, N. H. , Lav Madsen, P. , Johansen, M. L. , Rasmussen, J. J. , Forman, J. L. , Holm, M. R. , Rye Jørgensen, N. , Faber, J. , Rossignol, P. , Schou, M. , & Kistorp, C. (2021). Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist improves cardiac structure in type 2 diabetes: Data from the MIRAD trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology: Heart Failure, 9, 550–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A. J. M. , Gandy, S. , McCrimmon, R. , Houston, J. G. , Struthers, A. D. , & Lang, C. C. (2020). A randomized controlled trial of dapagliflozin on left ventricular hypertrophy in people with type two diabetes: The DAPA‐LVH trial. European Heart Journal, 41, 3421–3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J. E. (2021). Targeting the GIPR for obesity: To agonize or antagonize? Potential mechanisms. Molecular Metabolism, 46, 101139. 10.1016/j.molmet.2020.101139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantini, G. , Mannucci, E. , & Luconi, M. (2016). Perspectives in GLP‐1 research: New targets, new receptors. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism, 27, 427–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavasin, M. A. , Tao, Z. , Menon, S. , & Yang, X.‐P. (2004). Gender differences in cardiac function during early remodeling after acute myocardial infarction in mice. Life Sciences, 75, 2181–2192. 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandramouli, C. , Reichelt, M. E. , Curl, C. L. , Varma, U. , Bienvenu, L. A. , Koutsifeli, P. , Raaijmakers, A. J. A. , de Blasio, M. J. , Qin, C. X. , Jenkins, A. J. , Ritchie, R. H. , Mellor, K. M. , & Delbridge, L. M. D. (2018). Diastolic dysfunction is more apparent in STZ‐induced diabetic female mice, despite less pronounced hyperglycemia. Scientific Reports, 8, 2346. 10.1038/s41598-018-20703-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.‐R. , Shen, X.‐Q. , Zhang, Y. , Chen, Y.‐D. , Hu, S.‐Y. , Qian, G. , Wang, J. , Yang, J. J. , Wang, Z. F. , & Tian, F. (2016). Effects of liraglutide on left ventricular function in patients with non‐ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction. Endocrine, 52, 516–526. 10.1007/s12020-015-0798-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J. , Zhang, W. , Zhang, X. , Han, F. , Li, X. , He, X. , Li, Q. , & Chen, J. (2014). Effect of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers on all‐cause mortality, cardiovascular deaths, and cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes mellitus: A meta‐analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association Internal Medicine, 174, 773–785. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, B. , Kim, E.‐Y. , Kim, J.‐E. , Oh, S. , Park, S.‐O. , Kim, S.‐M. , Choi, H. , Song, J. K. , & Chang, E. J. (2021). Evogliptin suppresses calcific aortic valve disease by attenuating inflammation, fibrosis, and calcification. Cell, 10, 57. 10.3390/cells10010057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland, J. G. F. , Ferreira, J. P. , Mariottoni, B. , Pellicori, P. , Cuthbert, J. , Verdonschot, J. A. J. , Petutschnigg, J. , Ahmed, F. Z. , Cosmi, F. , Brunner la Rocca, H. P. , Mamas, M. A. , Clark, A. L. , Edelmann, F. , Pieske, B. , Khan, J. , McDonald, K. , Rouet, P. , Staessen, J. A. , Mujaj, B. , … Lange, T. (2021). The effect of spironolactone on cardiovascular function and markers of fibrosis in people at increased risk of developing heart failure: The heart ‘OMics’ in AGEing (HOMAGE) randomized clinical trial. European Heart Journal, 42, 684–696. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook, C. , Cole, G. , Asaria, P. , Jabbour, R. , & Francis, D. P. (2014). The annual global economic burden of heart failure. International Journal of Cardiology, 171, 368–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, L. B. , Lippmann, S. J. , Greiner, M. A. , Sharma, A. , Kelly, J. P. , Fonarow, G. C. , Yancy, C. W. , Heidenreich, P. A. , & Hernandez, A. F. (2017). Use of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in patients with heart failure and comorbid diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease. Journal of the American Heart Association, 6, e006540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, J. W. , Claggett, B. L. , O'Meara, E. , Prescott, M. F. , Pfeffer, M. A. , Shah, S. J. , Redfield, M. M. , Zannad, F. , Chiang, L. M. , Rizkala, A. R. , Shi, V. C. , Lefkowitz, M. P. , Rouleau, J. , McMurray, J. J. V. , Solomon, S. D. , & Zile, M. R. (2020). Effect of sacubitril/valsartan on biomarkers of extracellular matrix regulation in patients with HFpEF. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 76, 503–514. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dave, C. V. , Kim, S. C. , Goldfine, A. B. , Glynn, R. J. , Tong, A. , & Patorno, E. (2021). Risk of cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes after addition of SGLT2 inhibitors versus sulfonylureas to baseline GLP‐1RA therapy. Circulation, 143, 770–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedkov, E. I. , Oak, K. , Christensen, L. P. , & Tomanek, R. J. (2014). Coronary vessels and cardiac myocytes of middle‐aged rats demonstrate regional sex‐specific adaptation in response to postmyocardial infarction remodeling. Biology of Sex Differences, 5, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Prato, S. , Kahn, S. E. , Pavo, I. , Weerakkody, G. J. , Yang, Z. , Doupis, J. , Aizenberg, D. , Wynne, A. G. , Riesmeyer, J. S. , Heine, R. J. , Wiese, R. J. , Ahmann, A. J. , Arora, S. , Ball, E. M. , Calderon, R. B. , Butuk, D. J. , Chaychi, L. , Chen, M. C. , Curtis, B. M. , … Kotsa, K. (2021). Tirzepatide versus insulin glargine in type 2 diabetes and increased cardiovascular risk (SURPASS‐4): A randomised, open‐label, parallel‐group, multicentre, phase 3 trial. The Lancet, 398, 1811–1824. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02188-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, J. M. , Henley, W. E. , Weedon, M. N. , Lonergan, M. , Rodgers, L. R. , Jones, A. G. , Hamilton, W. T. , Sattar, N. , Janmohamed, S. , Holman, R. R. , Pearson, E. R. , Shields, B. M. , Hattersley, A. T. , MASTERMIND Consortium , Angwin, C. , Cruickshank, K. J. , Farmer, A. J. , Gough, S. C. L. , Gray, A. M. , … Walker, M. (2018). Sex and BMI alter the benefits and risks of sulfonylureas and thiazolidinediones in type 2 diabetes: A framework for evaluating stratification using routine clinical and individual trial data. Diabetes Care, 41, 1844–1853. 10.2337/dc18-0344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez, F. , Lalaguna, L. , López‐Olañeta, M. , Villalba‐Orero, M. , Padrón‐Barthe, L. , Román, M. , Bello‐Arroyo, E. , Briceño, A. , Gonzalez‐Lopez, E. , Segovia‐Cubero, J. , & García‐Pavía, P. (2021). Early preventive treatment with enalapril improves cardiac function and delays mortality in mice with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy type 5. Circulation . Heart Failure, 14, e007616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du, J. , Zhang, L. , Wang, Z. , Yano, N. , Zhao, Y. T. , Wei, L. , Dubielecka‐Szczerba, P. , Liu, P. Y. , Zhuang, S. , Qin, G. , & Zhao, T. C. (2016). Exendin‐4 induces myocardial protection through MKK3 and Akt‐1 in infarcted hearts. American Journal of Physiology ‐ Cellular Physiology, 310, C270–C283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dungan, K. M. (2016). Chapter 48 ‐ Management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. In Jameson J. L., De Groot L. J., de Kretser D. M., Giudice L. C., Grossman A. B., Melmed S., et al. (Eds.), Endocrinology: Adult and pediatric (seventh edition) (pp. 839–853.e2). W.B. Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- Dworatzek, E. , Baczko, I. , & Kararigas, G. (2016). Effects of aging on cardiac extracellular matrix in men and women. Proteomics ‐ Clinical Applications, 10, 84–91. 10.1002/prca.201500031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernande, L. , Audureau, E. , Jellis, C. L. , Bergerot, C. , Henegar, C. , Sawaki, D. , Czibik, G. , Volpi, C. , Canoui‐Poitrine, F. , Thibault, H. , Ternacle, J. , Moulin, P. , Marwick, T. H. , & Derumeaux, G. (2017). Clinical implications of echocardiographic phenotypes of patients with diabetes mellitus. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 70, 1704–1716. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.07.792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, G. , Cappetta, D. , Russo, R. , Rivellino, A. , Ciuffreda, L. P. , Roviezzo, F. , Piegari, E. , Berrino, L. , Rossi, F. , de Angelis, A. , & Urbanek, K. (2017). Sitagliptin reduces inflammation, fibrosis and preserves diastolic function in a rat model of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. British Journal of Pharmacology, 174, 4070–4086. 10.1111/bph.13686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan, D. , Takawale, A. , Lee, J. , & Kassiri, Z. (2012). Cardiac fibroblasts, fibrosis and extracellular matrix remodeling in heart disease. Fibrogenesis & Tissue Repair, 5, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang, L. , Murphy, A. J. , & Dart, A. M. (2017). A clinical perspective of anti‐fibrotic therapies for cardiovascular disease. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 8, 186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliegner, D. , Schubert, C. , Penkalla, A. , Witt, H. , Kararigas, G. , Dworatzek, E. , Staub, E. , Martus, P. , Noppinger, P. R. , Kintscher, U. , & Gustafsson, J. Å. (2010). Female sex and estrogen receptor‐β attenuate cardiac remodeling and apoptosis in pressure overload. American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 298, R1597–R1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogari, R. , Mugellini, A. , Destro, M. , Corradi, L. , Lazzari, P. , Zoppi, A. , Preti, P. , & Derosa, G. (2012). Losartan and amlodipine on myocardial structure and function: A prospective, randomized, clinical trial. Diabetic Medicine, 29, 24–31. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03383.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration . (2016). FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA adds warnings about heart failure risk to labels of type 2 diabetes medicines containing saxagliptin and alogliptin. Available: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-fda-adds-warnings-about-heart-failure-risk-labels-type-2-diabetes [Accessed 7th August 2021].