Abstract

Objective

A shared consensus on the safety about physical agent modalities (PAMs) practice in physiotherapy and rehabilitation is lacking. We aimed to develop evidence-informed and consensus-based statements about the safety of PAMs.

Study design and setting

A RAND-modified Delphi Rounds’ survey was used to reach a consensus. We established a steering committee of the Italian Association of Physiotherapy (Associazione Italiana di Fisioterapia) to identify areas and questions for developing statements about the safety of the most commonly used PAMs in physiotherapy and rehabilitation. We invited 28 National Scientific and Technical Societies, including forensics and lay members, as a multidisciplinary and multiprofessional panel of experts to evaluate the nine proposed statements and formulate additional inputs. The level of agreement was measured using a 9-point Likert scale, with consensus in the Delphi Rounds assessed using the rating proportion with a threshold of 75%.

Results

Overall, 17 (61%) out of 28 scientific and technical societies participated, involving their most representative members. The panel of experts mainly consisted of clinicians (88%) with expertise in musculoskeletal (47%), pelvic floor (24%), neurological (18%) and lymphatic (6%) disorders with a median experience of 30 years (IQR=17–36). Two Delphi rounds were necessary to reach a consensus. The final approved criteria list comprised nine statements about the safety of nine PAMs (ie, electrical stimulation neuromodulation, extracorporeal shock wave therapy, laser therapy, electromagnetic therapy, diathermy, hot thermal agents, cryotherapy and therapeutic ultrasound) in adult patients with a general note about populations subgroups.

Conclusions

The resulting consensus-based statements inform patients, healthcare professionals and policy-makers regarding the safe application of PAMs in physiotherapy and rehabilitation practice. Future research is needed to extend this consensus on paediatric and frail populations, such as immunocompromised patients.

Keywords: Physical Therapy Modalities, REHABILITATION MEDICINE, Health & safety, Musculoskeletal disorders, ORTHOPAEDIC & TRAUMA SURGERY, NEUROLOGY

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

Starting from a recent scoping review of the literature, we aimed to acknowledge evidence-informed indications of rehabilitation for safe physical agent modalities (PAMs).

Indications on the safety of physical agents (PAMs) were developed by a steering committee for different target conditions in physiotherapy and rehabilitation practice and supported by evidence and clinical expertise.

We strictly followed published guidelines for reporting and conduction, with a priori publicly registered protocol to determine agreement within the Delphi process.

The multiprofessional and multidisciplinary panel of experts rated and revised the agreement of indications for safe PAMs rehabilitation in multiple rounds until reaching a consensus.

Indications did not cover the clinical effectiveness of PAMs as well as specific subgroups for which evidence and expertise were not available.

Introduction

Physical agent modalities (PAMs) are extensively applied in physiotherapy and rehabilitation practice by targeting tissues to reduce swelling, alleviate pain, enhance healing and improve muscle tone.1–4 These treatments, recommended and administered by healthcare professionals across various medical fields, are often integrated with other physiotherapy and rehabilitation interventions.5 However, ensuring the safety of these treatments is fundamental for both clinicians and patients. Previous consensus on contraindications and precautions associated with using PAMs from various organisations was released in the early 2000s.6–8 Still, they have become outdated in light of technological advancements of the last years.9 10 A recent scoping review of the literature5 examined several systematic reviews on the safety of commonly used PAMs. This scoping review, encompassing treatments such as cryotherapy, electrical stimulation, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, functional electrical stimulation, extracorporeal shockwave therapy, laser therapy, magnetotherapy, pulsed electromagnetic field and diathermy, revealed no important harm associated with their use. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that adverse events may be under-reported in primary studies11 12 highlighting the need to integrate expert experience to bridge the current gaps between existing literature and clinical practice. Therefore, the purpose of the SAFEty of Physical Agent Modalities Practice (SAFE PAMP) consensus in physiotherapy and rehabilitation is to develop evidence-informed and expert consensus-based statements about the safety of PAMs through a RAND Delphi procedure. Our goal is to make patients, healthcare professionals and policy-makers aware about the safe application of PAMs in physiotherapy and rehabilitation.

Methods

Design

A RAND-modified Delphi Rounds survey process was employed as the facilitation technique for reaching expert consensus.13 14 The Delphi technique is primarily used when the available knowledge is incomplete or subject to uncertainty.15 We followed the guidance on ‘Conducting and REporting of DElphi Studies’.16 17 18 More details are reported in online supplemental file 1. The protocol was a priori registered on the Open Science Framework online repository.19

bmjopen-2023-075348supp002.pdf (176KB, pdf)

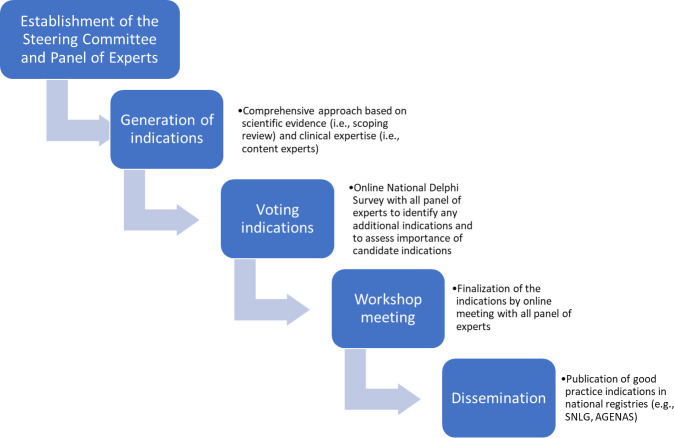

The process consisted of four phases: (1) establishment of the steering committee and invitation of national scientific and technical societies to constitute the panel of experts; (2) generation of statements using a comprehensive approach based on a published scoping review of existing systematic reviews on PAMs safety in physiotherapy and rehabilitation medicine5 as well as on expertise from content experts of the steering committee; (3) rating of statements from the panel of experts through a national Delphi survey aiming to identify, assess and modify statement importance for each field (eg, musculoskeletal) and (4) an online workshop meeting to finalise the list of statements reaching the final consensus. Finally, we planned to disseminate the final statements list as good clinical practice (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Phases of the RAND Delphi process. Legend: SNLG, Sistema Nazionale Linee Guida; AGENAS, Agenzia nazionale per i servizi sanitari regionali

Phase I: establishment of the steering committee and panel of experts

Steering committee

In June 2022, the project team nominated a steering committee responsible for defining the list of statements of safe PAMs, selecting national scientific and technical societies for expert participants, developing the Delphi questionnaires, and analysing responses from participants after each round.

The steering committee involved 11 content experts from the Italian Association of Physiotherapy (Associazione Italiana di Fisioterapia (AIFI)), a member of the World Physiotherapy.20 AIFI is the scientific and technical society in Italy for the physiotherapy profession recognised by the Italian Minister of Health to produce clinical practice guidelines in the field.21 22

To assure the external validity of the consensus process, the steering committee included two content experts on PAMs (MB and EP), three on rehabilitation of musculoskeletal disorders (GR, VG and SB), one on neurological physiotherapy and neuroscience (AT), one on pelvic floor rehabilitation (AF) and four methodologists (SGambazza, SGianola, GC and LP).

Panel of experts

It is known that the diversity of a Delphi panel has an impact on the quality of the final recommendations. In contrast, no agreement on the panel size for Delphi studies exists. Panels of 20–30 participants are common.23 24 Thus, the steering committee invited all the national multidisciplinary and multiprofessional scientific and technical societies involved in physiotherapy and rehabilitation care (n=26) and the societies dealing with forensics (n=1). These societies were identified from the published endorsed by the Italian Ministry of Health and are recognised as the ones entitled to generate national clinical practice guidelines.21 22 Each society delegated their most representative member involved in physiotherapy and rehabilitation care to join the panel of experts. The panel of expert members was multidisciplinary and multiprofessional, including clinicians, researchers and healthcare managers from different fields24 (eg, orthopaedics, neurology). To represent patients’ perspectives, the panel also included a lay member from Cittadinanzattiva,25 the largest Italian patient advocate organisation that promotes citizen activism for the protection of rights, the care of common goods and support for people in conditions of weakness.

Phase II: generation of statements

First, the steering committee formulated statements aimed at safety based on evidence and clinical expertise. Particularly, evidence was summarised from a published scoping review and its online supplemental materials,5 which gathered information about the safety of the nine PAMs from 117 systematic reviews in physiotherapy and rehabilitation medicine (eg, safety of PAMs for low back pain, osteoarthritis, stroke, urinary incomitance). Clinical expertise was assured by content experts of AIFI (eg, musculoskeletal disorders, orthopaedic and neurological physiotherapy and pelvic floor rehabilitation) adding examples of clinical conditions for which they commonly safely apply PAMs in their specific field. Disagreements between experts were resolved through discussion.

bmjopen-2023-075348supp001.pdf (61.8KB, pdf)

The steering committee formulated statements for each PAM (with distinction of evidence and expertise) ensuring that all the potentially relevant topics in the field would be included in the initial list of questions for the first Delphi round (online supplemental file 2 reported details about each included PAM). Each statement included a statement regarding safety about the following PAMs:

Electrical stimulation.

Neuromodulation, antalgic and interferential electrical currents.

Extracorporeal shock wave therapy.

Laser therapy.

Electromagnetic therapy.

Diathermy.

Hot thermal agents.

Cryotherapy.

Therapeutic ultrasound.

Statements were developed for different target conditions. PAMs are delivered by expert healthcare professionals (who had undergone formal education and training) to ensure patient safety in inpatient and outpatient settings. Statements were presented within the relevant rehabilitation field, along with a list of patient conditions in which the PAMs were indicated as safe and supported by evidence and clinical expertise.

Phase III: rating of statements through Delphi rounds

We employed an electronic Delphi process, allowing participants to submit responses anonymously and independently without being biased by other participants’ identities and responses. The steering committee reached out to the panel of experts using the SurveyMonkey online platform (Palo Alto, California, USA; www.surveymonkey.com) and used a blinded electronic rating.

The web-based survey comprised two sections: the first concerned the participants’ demographics (eg, type of profession, field of expertise and years of experience), and the second involved rating the statements. The panel of experts evaluated the proposed statements and provided additional comments using a free text box to ensure complete coverage of the topics. According to the RAND method, the panel of experts used a 9-point Likert scale (ie, 1–3=highly inappropriate, 4–6=undecided and 7–9=highly appropriate) to rate the level of concordance for each statement.

In addition, experts could abstain from rating by selecting the answer ‘not my expertise’ for statements they were not familiar with.

A summary of results for each Delphi round was shared as feedback to update panel members on the progress of consensus development, including descriptive statistics, to guide subsequent rounds. The panel of experts was asked to re-rate their evaluation in subsequent rounds only for those statements needing clarification or for statements for which consensus (ie, ≥75% on a 7–9 points scale or 1–3 points scale) was not reached.

An anonymous report of each round was provided to each expert, showing the distribution of responses for each statement, along with all additional comments provided in the free text box. Based on previous ratings, statements were modified and presented for the next round. Up to three reminder emails for completion were sent to each participant individually. Data collection occurred over 5 months (June–November 2022).

Phase IV: workshop meeting as last round

After reaching a consensus, the steering committee joined an online meeting to refine statements according to each expert’s contribution and confirm which statements would be included in the final criteria list. Finally, the panel of experts was asked to rate the final statements list for the closing audit procedure.

Definition and calculation of consensus

In agreement with the RAND appropriateness method, we adopted predefined criteria26 to assess the consensus in the Delphi method, using the proportion of ratings with a threshold of 75%.27 Specifically:

Consensus in: ≥75% of participants scored the item as ‘highly appropriate’ (scores 7–9) and <15% scored the item as of ‘highly inappropriate’ (scores 1–3).

Consensus out: ≥75% of participants scored the item as of ‘highly inappropriate’ (scores 1–3) and <15% scored the item as ‘highly appropriate’ (scores 7–9).

No consensus: all other results.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe general characteristics of participants, summarised as median and IQR and counts and percentage (%), as appropriate. Each statement was analysed quantitatively by the percentage of agreement ratings.

Role of the funding source

AIFI supported this research. The funder played no role in this study’s design, conduct or reporting.

Patient and public involvement

In this study, a patient representative participated in the panel of experts to rate the statements.

Results

Participants

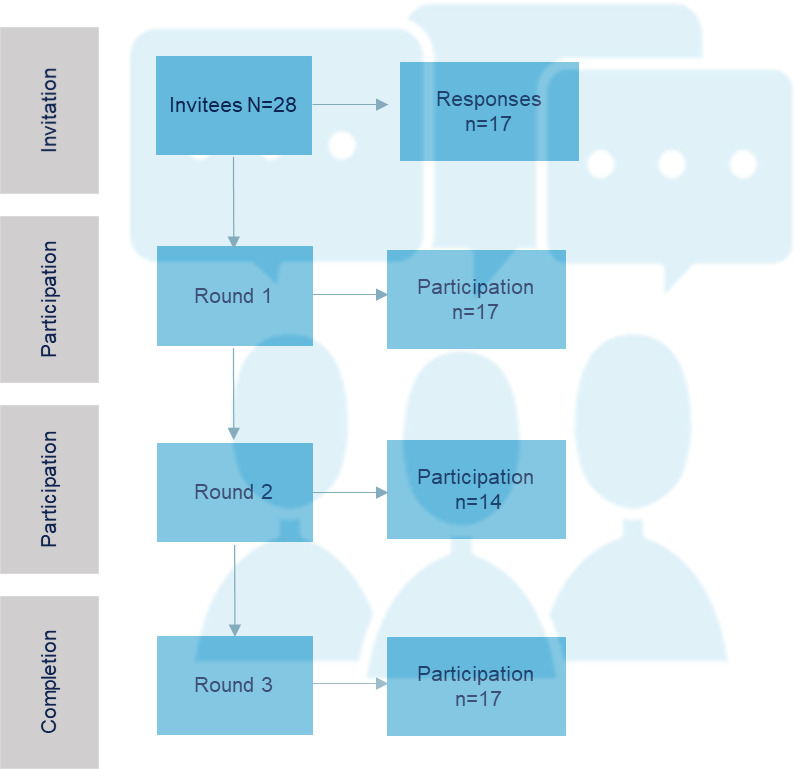

Out of the 28 scientific and technical societies/organisations that were invited as panel of experts, 2 declined their interest in participation, while 9 did not provide a response. Finally, 17 societies/organisations (invitation rate: 61%), each represented by their most representative expert member, were included (figure 2). The majority of experts were clinicians (88.2%), with half having expertise in musculoskeletal disorders (47.1%). Others were specialised in areas such as pelvic floor (23.5%), neurological (17.6%), lymphatic disorders (5.9%), paediatrics (5.9%). The panel also included a forensic and a lay member as patient representative. On average, experts had a median of 30 years of experience (IQR 17–36) in their respective fields. All general characteristics are reported in table 1. No conflict of interest was present (online supplemental file 3).

Figure 2.

Flow chart of Delphi process.

Table 1.

General characteristics of experts panel (n=17)

| Professional profile* | Responses N (%) |

| Clinicians | 15 (88.2) |

| Researchers | 7 (41.2) |

| Management | 4 (23.5) |

| Field of expertise* | |

| Musculoskeletal | 8 (47.1) |

| Pelvic floor disorders | 4 (23.5) |

| Neurological | 3 (17.6) |

| Lymphatic disorders | 1 (5.9) |

| Paediatrics | 1 (5.9) |

| Lay member (patient) | 1 (5.9) |

| Forensic member | 1 (5.9) |

*More than one answer was possible.

Delphi rounds

Two Delphi rounds were necessary to reach a consensus.

Round 1

Overall, 17 experts panel participants completed the survey (participation rate: 100%). All statements passed the first round with a consensus of 75% (table 2). Five experts offered justifications for their choices (eg, examples of clinical practice) and provided important inputs for the statements. In particular, most of them raised concerns about the safe use of PAMs in children. Additionally, they suggested refining the purpose of the statements, emphasising that the focus was on patient safety rather than provider safety. Some experts reported uncertainties about safe use of PAMs based on their experiences. For example, one expert mentioned the possibility of mild skin irritation in hot thermal therapies, and another suggested caution in the use of cryotherapy due to risk of cold burns, especially if patients are not well informed or supervised. Then, one expert expressed uncertainty about the safety of long-term use of electromagnetic therapies. Some experts suggested the safe use of PAMs in other fields of applications such as the use of diathermia in the dermatology for lichen sclerosus, which was out of our purposes. All comments were considered in the release of the statements (online supplemental file 4).

Table 2.

Agreement results for each round

| Statements about the safety of… | Round 1 | Round 2 | Final list | |||

| Percentage of agreement (7–9 points on the Likert scale) | Percentage of disagreement (1–3 points on the Likert scale) | Percentage of agreement (7–9 points on the Likert scale) | Percentage of disagreement (1–3 points on the Likert scale) | Approved | NME | |

| Electrical stimulation | 85.7 | 7.1 | 85.7 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| Neuromodulation, antalgic and interferential electrical currents | 100.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| Extracorporeal shock wave therapy | 83.3 | 0.0 | 76.9 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| Laser therapy | 84.6 | 7.7 | 90.9 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| Electromagnetic therapy | 81.8 | 9.1 | 76.9 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| Diathermy | 90.0 | 10.0 | 84.6 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| Hot thermal agents | 81.8 | 9.1 | 91.7 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| Cryotherapy | 75.0 | 0.0 | 90.9 | 0.0 | 94.2 | 5.8 |

| Therapeutic ultrasound | 90.9 | 0.0 | 91.7 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| General note* | – | – | – | – | 100.0 | 0.0 |

*Added for the final criteria list.

NME, not my expertise.

Round 2

The statements from round 1 were reviewed based on panel comments for the subsequent assessment in round 2, with a specific restriction on the adult population and a clearer emphasis on patient safety.

In round 2, a total of 14 expert panel participants completed the survey (participation rate: 82%), and all the statements achieved consensus out of the 75% threshold (table 2). One expert provided additional comments including examples of expertise, which were subsequently integrated into the final list of statements. In particular, low-level laser therapy could exacerbate genital dryness, necessitating additional interventions to improve hydration during the treatment period and mitigate discomfort for patients. Additionally, there was uncertainty regarding the application of other therapies, such as electrical stimulation and extracorporeal shock wave therapy, in certain fields due to limited expertise (online supplemental file 4).

Workshop meeting

On 27 September 2022, nine experts panel participants (completion rate: 53%) joined the online meeting to discuss comments, justifications and highlights. A comprehensive digital presentation of the findings from round 1 and round 2 were reported during the workshop. During the meeting, the panel of experts suggested introducing a general note explicitly stating that statements on safety were not extended to different subgroups of the population (eg, children, adolescents, immunocompromised individuals) due to lack of literature.

The final list of statements, along with this general note, was shared via SurveyMonkey for final approval. All 17 experts panel participants (approval rate: 100%) approved and released the final list of statements. One expert selected the option ‘not my expertise’ for the statement on cryotherapy (table 2). In online supplemental appendix 1, we reported the final criteria list released for good clinical practice with details of sources (evidence and expertise) and applications in different fields and clinical conditions.

Discussion

Main findings

The SAFE PAMP consensus developed safety statements for PAMs in physical therapy and rehabilitation practice. The multidisciplinary and multiprofessional panel of experts participated with a moderate response rate (61%).28 All nine statements were approved in two rounds (consensus of over 75% agreement.) and released in a final workshop meeting with some adjustments made (eg, specific population subgroups). In summary, experts agreed on the safety of PAMs in the adult population (>18 years) when prescribed and applied by a healthcare professional (eg, physiotherapist, physician) who is adequately trained and informed, as required by education and licensure.

Literature context

Earlier consensus documents from different organisations were published in 2001,6 20067 and 2010.8 In 2018, the American Occupational Therapy Association issued a position paper29 clarifying the appropriate use of PAMs in contemporary occupation-based occupational therapy practice, providing clinical case vignettes in their field. Others reported indications and contraindications about specific types of PAMs (eg, extracorporeal shock wave therapy30). Many other societies, such as National Institute for Clinical Excellence, also offer specific clinical questions guidelines, and we cannot exclude that they can involve recommendations on PAMs (eg, NG59 for low back pain31).

Overall, the Canadian document8 represents the most comprehensive guidance on this topic. However, our Delphi is the most recent consensus on PAMs focusing on statements about safe PAMs application as clinical practice indications (eg, field) sustained by literature and clinical expertise. This does not mean that the contraindications and precautions mentioned in the Canadian guideline8 are in contrast to our findings. Simply, we use a complementary perspective. Our Delphi agrees to define the common safe applications stratifying by fields/conditions whereas the Canadian one describes the contraindications and precautions about these common applications in particular situations or under certain circumstances. For instance, both documents recognise cryotherapy and electrical stimulation as commonly safe PAMs in musculoskeletal applications, such as treating ankle sprains and osteoarthritis. However, the Canadian guideline recommends precaution when combining compression with cryotherapy to ensure the preservation of circulation and nerves. Furthermore, the guideline contraindicated the use of electrical stimulation in presence of implanted electronic devices. Although the evidence presented in the Canadian guideline was not systematically collected (Canada and the US experts in conjunction with multiple sources such as textbooks), it is reasonable to assume that many precautions and contraindications still remain applicable. Nevertheless, it is important to note that guidelines should be updated every 3–5 years or when new information becomes available.32 33

Implications for clinicians

Healthcare professionals are encouraged to use a comprehensive approach when using this Delphi consensus. Prior to proposing PAMs to patients, they must collect their medical history (eg, comorbidities) to better determine the diagnosis, prognosis, anticipated goals and expected outcomes.34 Then, they should incorporate the best research evidence, clinical expertise, patient values, needs and preferences to propose effective treatments, balancing effectiveness and safety. It is imperative that patients are informed about the possibility of trivial adverse events (eg, pain and erythema at the application site5 using extracorporeal shock wave therapy). However, in situations when evidence is lacking and there is a likelihood of moderate to severe harm, caution is advised, and the use of PAM may be reconsidered. In fact, for precautionary reasons,35–37 the developed statements were not generally extended to other subgroups, such as children and adolescents (due to biological tissue in growth phases38 39), and frail individuals (eg, immunocompromised patients), given the limited and insufficient literature on potential harm. It is important to adhere to these statements in conjunction with precautions and contraindications under specific circumstances, referring to equipment manufacturers’ manuals and regulatory bodies40 as well as previous guidelines8 and standards established by professional associations.

Implications for stakeholders

Good practices for patients safety should be managed by national agencies with a living monitoring system and shared through international initiatives such as the WHO Global Patient Safety Challenge Medication Safety41 to enhance systems and practices adopting corrective action within countries. For instance, national and international scientific and technical societies should facilitate the dissemination of CPGs through various strategies, such as storing good clinical practices in shared repository42 as well as disseminating plain, patient-oriented versions of good clinical practice statements. This supports patient empowerment and contributes to making the healthcare system more efficient, tailored and safer.43 44 We plan to organise meetings with stakeholders and patients, conduct webinars and provide education and counselling through pamphlets, videos and social media messages.

Implications for research

We believe that the statements developed by the multidisciplinary and multiprofessionally panel of experts can be generalised worldwide. These results could provide essential information to produce national guidelines (eg, Good Clinical Practices of the Italian Ministry of Health45) and international guidelines to improve patient safety and decrease avoidable harm related to interventions. Studies should convey their efforts to plan and adequately report adverse events before objectively estimating these harms. We call for multicentric randomised controlled trials based on a core outcome set, including harms in addition to benefits.46 In addition, specific subgroups of populations should be studied. It is a serious matter to exclude a group from research eligibility, and this should only be done when no less restrictive option is sufficient to ensure protection from undue risk.47

Lastly, future studies can better expand our statements to ensure the safest and most optimal modality application of the proposed PAMs (eg, optimal voltage, amperage, frequency, current density, dose), as well as contraindications and precautions, especially for the mentioned subgroups (eg, children, immunocompromised individuals).48

Strength and limitations

This represents the first effort to provide guidance on the safety of PAMs in physiotherapy and rehabilitation. We strictly followed published guidelines for reporting and conduction. In addition, we a priori publicly registered the consensus criterion used to determine agreement within the Delphi process.26 49 We adopted one of the most conservative thresholds for obtaining the consensus (75%),27 and in all rounds, this threshold was reached with a high percentage of agreements. However, some downsides should be acknowledged. We did not cover statements about the clinical effectiveness of PAMs, as our aim was to make patients, healthcare providers and policy-makers aware about the safety application of PAMs in clinical practice. As well, we did not aim to report specific contraindications as we started collecting evidence from systematic reviews that reported safety outcomes from primary studies, which may not always encompass real-world conditions, such as the presence of comorbidities (eg, active deep vein thrombosis). Furthermore, evidence informed by systematic reviews did not find enough information about the risk for specific population (eg, haemato-oncological patients with severe immunocompromised or coagulopathy). However, based on the principle of precaution, the panel agreed to add as a general note about precautions in specific subgroups of the population, in the absence of literature. As with all Delphi process, our study relies on national expert response and may not capture the full range of perspectives or experiences.16 50 Nevertheless, we tried to involve multidisciplinary and multiprofessional experts (as occurs in clinical practice guidelines) enabling confrontations in anonymity (avoiding negatively influencing outcomes and encouraging balanced consideration of ideas). Then, statements were developed starting from the scoping review,5 which mapped and summarised safety in population and intervention areas without assessing the certainty of evidence (eg, grading of the certainty of evidence).5 Lastly, even though we generated statements based on the latest available evidence, we should recognise that adverse events may be underestimated since safety outcome is commonly poorly reported in the literature.11 12 51

Conclusion

These evidence-based statements inform patients, healthcare professionals and policy-makers about the safety of a wide range of PAMs in various fields and conditions of physiotherapy and rehabilitation practice, following comprehensive clinical evaluation of patients’ needs. All of these statements should be associated to precautions and contraindications for specific cases, referring to previous guidelines, equipment manufacturers’ manual and regulatory bodies. This consensus can provide a basis for decision-making and future research.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @Gianola

Collaborators: SAFE PAMP Collaborators: Chiara Torresetti, on behalf of AIUG (Associazione Italiana di Urologia Ginecologia e del Pavimento Pelvico); Bianca Masturzo, on behalf of AOGOI (Associazione Ostetrici Ginecologi Ospedalieri Italiani); Carla Berliri, on behalf of Cittadinanzattiva Associazione di Promozione Sociale; Mauro Roselli, on behalf of OTODI (Ortopedici e Traumatologi Ospedalieri D’Italia); Stefano Vercelli, on behalf of FIASF (Federazione Italiana delle Associazioni Scientifiche di Fisioterapia); Marco Scorcu, on behalf of FMSI (Federazione Medico Sportiva Italiana); Giuseppe Botta, on behalf of SIFL (Società Italiana di Flebolinfologia); Luigi Nappi, on behalf of SIGO (Società Italiana Di Ginecologia E Ostetricia); Gianmarco Rea, on behalf of SIMG (Società Italiana di Medicina Generale e delle cure primarie); Enrico Marinelli, on behalf of SIMLA (Società Italiana di Medicina Legale e delle Assicurazioni); Fabio Bandini, on behalf of SIN (Società Italiana di Neurologia); Roberto Bortolotti, on behalf of SIR (Società Italiana di Reumatologia); Viviana Rosati, on behalf of SIRN (Società Italiana di Riabilitazione Neurologica); Armando Perrotta, on behalf of SISC (Società Italiana per lo Studio delle Cefalee); Gianfranco Lamberti, on behalf of SIUD (Società Italiana di Urodinamica); Monica Pierattelli, on behalf of SICuPP (Societa’ Italiana Delle Cure Primarie Pediatriche); Giancarlo Tancredi, on behalf of SIP (Società Italiana di Pediatria).

Contributors: Concept/idea/research design: SGianola, SB and GC. Writing: SGianola, SB and GC. Data collection: SGianola and SB. Data analysis: SGianola and SB. Project management: SGianola and SB. Consultation (including review of manuscript before submitting): SGianola, SB, LP, SGambazza, GR, AF, VG, MB, EP, SC, GC, AT and SAFE PAMP Collaborators. GC and AT are joint last authors. GC and AT are responsible for the overall content as the guarantors.

Funding: This work was supported and funded by Associazione Italiana di Fisioterapia (AIFI). The APC was funded by AIFI.

Disclaimer: This research did not receive specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: SAFE PAMP Collaborators, Chiara Torresetti, Bianca Masturzo, Carla Berliri, Mauro Roselli, Stefano Vercelli, Marco Scorcu, Giuseppe Botta, Luigi Nappi, Gianmarco Rea, Enrico Marinelli, Fabio Bandini, Roberto Bortolotti, Viviana Rosati, Armando Perrotta, Gianfranco Lamberti, Monica Pierattelli, and Giancarlo Tancredi

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. Research data are stored in OSF repository https://osf.io/w8kgs/

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This project is exempted from ethical approval according to the 'ethics and data protection' regulations of the European Commission.

References

- 1.McCann J, Roy C, Ward C. Rehabilitation medicine. Available: https://www.bsrm.org.uk/downloads/rehabilitationmedicine-final.pdf [Accessed May 2023].

- 2.Kreutzer JS, Gervasio AH, Camplair PS. Primary Caregivers' psychological status and family functioning after traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 1994;8:197–210. 10.3109/02699059409150973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caserta MS, Lund DA, Wright SD. Exploring the Caregiver burden inventory (CBI): further evidence for a multidimensional view of burden. Int J Aging Hum Dev 1996;43:21–34. 10.2190/2DKF-292P-A53W-W0A8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cameron M. Physical Agents in Rehabilitation An Evidence-Based Approach to Practice 5th Edition ed. Elsevier, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bargeri S, Pellicciari L, Gallo C, et al. What is the landscape of evidence about the safety of physical agents used in physical medicine and rehabilitation? A Scoping review. BMJ Open 2023;13:e068134. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-068134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robertson V, Chipchase L, Laakso L, et al. Guidelines for the clinical use of Electrophysical agents. 2001.

- 7.Chartered Society of Physiotherapy . Guidance for the clinical use of electrophysical agents. London, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.ELECTROPHYSICAL AGENTS - Contraindications and precautions: an evidence-based approach to clinical decision making in physical therapy. Physiotherapy Canada 2010;62:1–80. 10.3138/ptc.62.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iijima H, Takahashi M. Microcurrent therapy as a therapeutic modality for musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review accelerating the translation from clinical trials to patient care. Arch Rehabil Res Clin Transl 2021;3:100145. 10.1016/j.arrct.2021.100145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mendes LA, Lima IN, Souza T, et al. Motor Neuroprosthesis for promoting recovery of function after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;1:CD012991. 10.1002/14651858.CD012991.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlesso LC, Macdermid JC, Santaguida LP. Standardization of adverse event terminology and reporting in Orthopaedic physical therapy: application to the Cervical spine. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2010;40:455–63. 10.2519/jospt.2010.3229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sachse T, Mathes T, Dorando E, et al. A review found heterogeneous approaches and insufficient reporting in Overviews on adverse events. J Clin Epidemiol 2022;151:104–12. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Schulz KF, Simera I, et al. Guidance for developers of health research reporting guidelines. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000217. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs 2000;32:1008–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niederberger M, Spranger J. Delphi technique in health sciences: A map. Front Public Health 2020;8:457. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jünger S, Payne SA, Brine J, et al. Guidance on conducting and reporting Delphi studies (CREDES) in palliative care: recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat Med 2017;31:684–706. 10.1177/0269216317690685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Equator network . Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research, Available: https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/credes/ [Accessed Sep 2023].

- 18.European Commission . Ethics and data protection, Available: https://ec.europa.eu/info/funding-tenders/opportunities/docs/2021-2027/horizon/guidance/ethics-and-data-protection_he_en.pdf [Accessed May 2023].

- 19.Gianola S, Bargeri S, Castellini G, et al. Data from: Italian suggestions about the safety of physical agents in physical therapy and rehabilitation medicine. Open science Framework repository (OSF), Available: https://osf.io/w8kgs/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.Associazione Italiana Di Fisioterapia (AIFI). Available: https://aifi.net/ [Accessed Sep 2023].

- 21.Legge 8 Marzo 2017, N. 24 Disposizioni in Materia Di Sicurezza delle cure E Della persona Assistita, Nonche' in Materia Di Responsabilita' Professionale Degli Esercenti le Professioni Sanitarie. Available: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2017/03/17/17G00041/sg [Accessed Apr 2022].

- 22.Basagni B, Navarrete E, Bertoni D, et al. The Italian version of the brain injury rehabilitation trust (BIRT) personality questionnaires: five new measures of personality change after acquired brain injury. Neurol Sci 2015;36:1793–8. 10.1007/s10072-015-2251-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akins RB, Tolson H, Cole BR. Stability of response characteristics of a Delphi panel: application of Bootstrap data expansion. BMC Med Res Methodol 2005;5:37. 10.1186/1471-2288-5-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Birko S, Dove ES, Özdemir V. Evaluation of nine consensus indices in Delphi foresight research and their dependency on Delphi survey characteristics: A simulation study and debate on Delphi design and interpretation. PLoS One 2015;10:e0135162. 10.1371/journal.pone.0135162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cittadinanzattiva. Available: https://www.cittadinanzattiva.it/ [Accessed Oct 2023].

- 26.Grant S, Booth M, Khodyakov D. Lack of Preregistered analysis plans allows unacceptable data mining for and selective reporting of consensus in Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2018;99:96–105. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, et al. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends Methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:401–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fincham JE. Response rates and responsiveness for surveys, standards. Am J Pharm Educ 2008;72:43. 10.5688/aj720243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Physical agents and mechanical modalities. Am J Occup Ther 2018;72(Supplement_2):7212410055p1–6. 10.5014/ajot.2018.72S220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.International Society for Medical Shockwave Treatment (ISMST) . Consensus statement on ESWT indications and Contraindications. Available: https://www.shockwavetherapy.org/fileadmin/user_upload/ISMST_Guidelines.pdf [Accessed Oct 2023].

- 31.de Campos TF. Low back pain and sciatica in over 16S: assessment and management NICE guideline. J Physiother 2017;63:120. 10.1016/j.jphys.2017.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shekelle PG, Ortiz E, Rhodes S, et al. Validity of the agency for Healthcare research and quality clinical practice guidelines: how quickly do guidelines become outdated JAMA 2001;286:1461–7. 10.1001/jama.286.12.1461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shekelle P, Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM, et al. When should clinical guidelines be updated BMJ 2001;323:155–7. 10.1136/bmj.323.7305.155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.WCPT . Standards of physical therapy practice. n.d. Available: https://world.physio/sites/default/files/2020-07/G-2011-Standards-practice.pdf

- 35.European Parliament . The precautionary principle: Definitions, applications and governance, Available: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_IDA(2015)573876 [Accessed May 2023].

- 36.Commission E. The precautionary principle: decision making under uncertainty, Available: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/integration/research/newsalert/pdf/precautionary_principle_decision_making_under_uncertainty_FB18_en.pdf [Accessed 2023].

- 37.European Parliament . The precautionary principle. Available: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2015/573876/EPRS_IDA(2015)573876_EN.pdf [Accessed Jan 2024].

- 38.Yeom M, Kim S-H, Lee B, et al. Effects of laser Acupuncture on longitudinal bone growth in adolescent rats. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013;2013:424587. 10.1155/2013/424587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nguyen JC, Markhardt BK, Merrow AC, et al. Imaging of pediatric growth plate disturbances. Radiographics 2017;37:1791–812. 10.1148/rg.2017170029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.EUDAMED . European database on medical devices. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/tools/eudamed/#/screen/home [Accessed Sep 2023].

- 41.WHO global patient safety challenge on medication without harm. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HIS-SDS-2017.6 [Accessed Jun 2023].

- 42.AGENAS . Agenzia Nazionale per i Servizi Sanitari Regionali, Available: https://www.agenas.gov.it/comunicazione/primo-piano/2111-avvio-call-for-good-practice-2022 [Accessed May 2023].

- 43.Odone A, Buttigieg S, Ricciardi W, et al. Public health digitalization in Europe. Eur J Public Health 2019;29(Supplement_3):28–35. 10.1093/eurpub/ckz161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santesso N, Morgano GP, Jack SM, et al. Dissemination of clinical practice guidelines: A content analysis of patient versions. Med Decis Making 2016;36:692–702. 10.1177/0272989X16644427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sistema Nazionale Linee Guida - ISS. Buone Pratice Clinico Assistenziali, Available: https://www.iss.it/snlg-buone-pratiche [Accessed Jan 2024].

- 46.COMET Initiative, Available: https://www.comet-initiative.org/Resources/AdverseEventOutcomes [Accessed Apr 2022].

- 47.Langford A, Bateman-House A. Clinical trials for COVID-19: populations most vulnerable to COVID-19 must be included. Health Affairs Blog Retrieved December 2020;1. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thabet AA, Ebid AA, El-Boshy ME, et al. Pulsed high-intensity laser therapy versus low level laser therapy in the management of primary Dysmenorrhea. J Phys Ther Sci 2021;33:695–9. 10.1589/jpts.33.695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.De Meyer D, Kottner J, Beele H, et al. Delphi procedure in core outcome set development: rating scale and consensus criteria determined outcome selection. J Clin Epidemiol 2019;111:23–31. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fink-Hafner D, Dagen T, Doušak M, et al. Delphi method: strengths and weaknesses. Advances in Methodology and Statistics 2019;2:1–19. 10.51936/fcfm6982 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dal-Ré R, Ioannidis JP, Bracken MB, et al. Making prospective registration of observational research a reality. Sci Transl Med 2014;6:224. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-075348supp002.pdf (176KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-075348supp001.pdf (61.8KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. Research data are stored in OSF repository https://osf.io/w8kgs/