Abstract

Periodontal diseases are well-known background for infective endocarditis. Here, we show that pericardial effusion or pericarditis might have origin also in periodontal diseases. An 86-year-old man with well-controlled hypertension and diabetes mellitus developed asymptomatic increase in pericardial effusion. Two weeks previously, he took oral new quinolone antibiotics for a week because he had painful periodontitis along a dental bridge in the mandibular teeth on the right side and presented cheek swelling. The sputum was positive for Streptococcus species. He was healthy and had a small volume of pericardial effusion for the previous 5 years after drug-eluting coronary stents were inserted at the left anterior descending branch 10 years previously. The differential diagnoses listed for pericardial effusion were infection including tuberculosis, autoimmune diseases, and metastatic malignancy. Thoracic to pelvic computed tomographic scan demonstrated no mass lesions, except for pericardial effusion and a small volume of pleural effusion on the left side. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography disclosed many spotty uptakes in the pericardial effusion. The patient denied pericardiocentesis, based on his evaluation of the risk of the procedure. He was thus discharged in several days and followed at outpatient clinic. He underwent dental treatment and pericardial effusion resolved completely in a month. He was healthy in 6 years until the last follow-up at the age of 92 years. We also reviewed 8 patients with pericarditis in association with periodontal diseases in the literature to reveal that periodontal diseases would be the background for developing infective pericarditis and also mediastinitis on some occasions.

Keywords: pericardial effusion, pericarditis, periodontitis (periodontal disease), positron emission tomography, Streptococcus

Background

Periodontal diseases are infectious and inflammatory conditions in periodontal tissues which include gingival mucosa, periodontal ligaments, teeth, and alveolar bone. Gingivitis is used as a diagnostic term when inflammation is limited to gingival mucosa while periodontitis indicates the destruction of alveolar bone which is evident on x-ray imaging. Periodontal diseases have been recognized as associating factors and underlying factors for the development and exacerbation of systemic diseases such as cardiovascular diseases and diabetes mellitus.1-9 Oral hygiene to control periodontal diseases is also important to reduce postoperative complications of pulmonary, cardiovascular, and gastrointestinal surgeries.10,11 Oral health would also play a role for treatment outcome in patients with cancers and leukemia. 12

In particular, infective endocarditis is well known as sequelae to bloodstream infection from periodontitis.13-15 Dental treatment and periodontal procedures, indeed, lead to bacteremia. 16 In this study, we present a patient with pericardial effusion, which might be related with periodontitis. We also review 8 patients in the literature who developed pericarditis in association with periodontal diseases.17-24

Case Report

An 86-year-old man was referred to a University Hospital from a cardiologist because he showed asymptomatic increase in pericardial effusion. He was healthy and pointed out to have a small volume of pericardial effusion for the previous 5 years. He was working as an ophthalmologist 3 days a week in a local hospital. He had been taking oral medications toward essential hypertension and diabetes mellitus from his fifties. He did not smoke or drink alcohol. In the past history, he had cataract surgeries with intraocular lens implantation in both eyes at the age of 72 years. At the age of 76 years, he underwent the insertion of drug (sirolimus)-eluting coronary stents (Cypher 3.5 x 13 mm, Cordis, Cardinal Health, Dublin, Ohio) at 2 locations of the left anterior descending branch. The left ventricular ejection fraction was 69% within the normal limit at that time. At 78 years, he had 2 successive episodes of tonic clonic generalized seizure, suspected of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, 5 days after influenza vaccination, and had no aftereffects ever since. At 82 years, he had antibiotics to eradicate gastric Helicobacter pylori. Two weeks before the referral visit at 86 years, he took oral new quinolone antibiotics for a week because he had painful periodontitis along a dental bridge in the mandibular premolar teeth on the right side (Figure 1A) and presented cheek swelling. He had been experiencing mild periodontitis for several years. Serum C-reactive protein (CRP) was elevated to 2.9 mg/dL 10 days before the referral. Just before the referral visit, he had fecal occult blood and underwent gastroscopic and colonoscopic examinations to detect no abnormalities except for colonic polyp at another hospital. Sputum tests detected Streptococcus species at 3+ level and Candida albicans at 1+ level, but showed no acid-fast bacilli. Serological tests for syphilis, including rapid plasma reagin test and treponemal pallidum latex agglutination, were both negative. Interferon-γ-releasing assay with T-SPOT (Oxford Immunotec, Ltd., Oxfordshire, UK) was negative as well.

Figure 1.

Dental x-rays 2 weeks before the admission (A, maxillary teeth in upper panels, mandibular teeth in lower panels, right-side teeth in left panels, and left-side teeth in right panels), and dental x-rays before (B) and after (C) root canal treatment for chronic apical periodontitis in the first and second premolar teeth 2 months later. Pyocele-like alveolar bone resorption around the apex of mandibular first premolar tooth on the right side (arrows in A, B, and C) is noted in the background of diffuse gingival recession and alveolar bone resorption due to the old age.

On the referral visit, physical and neurological examinations detected no particular findings. The height was 158 cm and the body weight 54 kg. The blood pressure was 108/65 mm Hg and the pulse rate 65 beats per minute. He said that his best pulse rate was around 48 beats per minute. He was healthy and did not have fever, but still had mild periodontal pain on the right side. The current medications were sitagliptin 50 mg and glimepiride 0.5 mg daily for diabetes mellitus, clopidogrel 75 mg daily for the coronary stents, eplerenone 25 mg and a combined tablet of olmesartan medoxomil 10 mg and azelnidipine 8 mg daily for hypertension, and lansoprazole 15 mg as a proton pump inhibitor. A week later on admission for detailed examinations of pericardial effusion, red blood cell count was 4.54 × 106/µL, hemoglobin 11.6 g/dL, platelet count 331 × 103/µL, white blood cell count 4.56 × 103/µL with differentials of 9.4% lymphocytes, 84.1% neutrophils, 5.9% monocytes, and 0.7% eosinophils. C-reactive protein which was elevated to 6.7 mg/dL a week before the admission was decreased to 1.17 mg/dL. Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) was mildly elevated to 47.7 pg/mL. Fasting blood glucose was 111 mg/dL, and hemoglobin A1c was 7.3%. Liver and kidney functions were within normal limits. Serum sodium was low at 127 mmol/L and chloride low at 95 mmol/L. Serum total cholesterol was low at 134 mg/dL and triglyceride also low at 52 mg/dL. Urinalysis was normal. The chest plain x-ray film showed the dilation of cardiac shadow with obscured costophrenic angle on the left side (Figure 2B). Electrocardiogram showed regular sinus rhythm with wide QRS, indicative of the left bundle branch block (Figure 2A). Left ventricular ejection fraction determined by cardiac ultrasonography was 50%. The cardiac contractility was good, all valvular functions were normal, and pericardial effusion was approximately 13 mm at the cardiac apex.

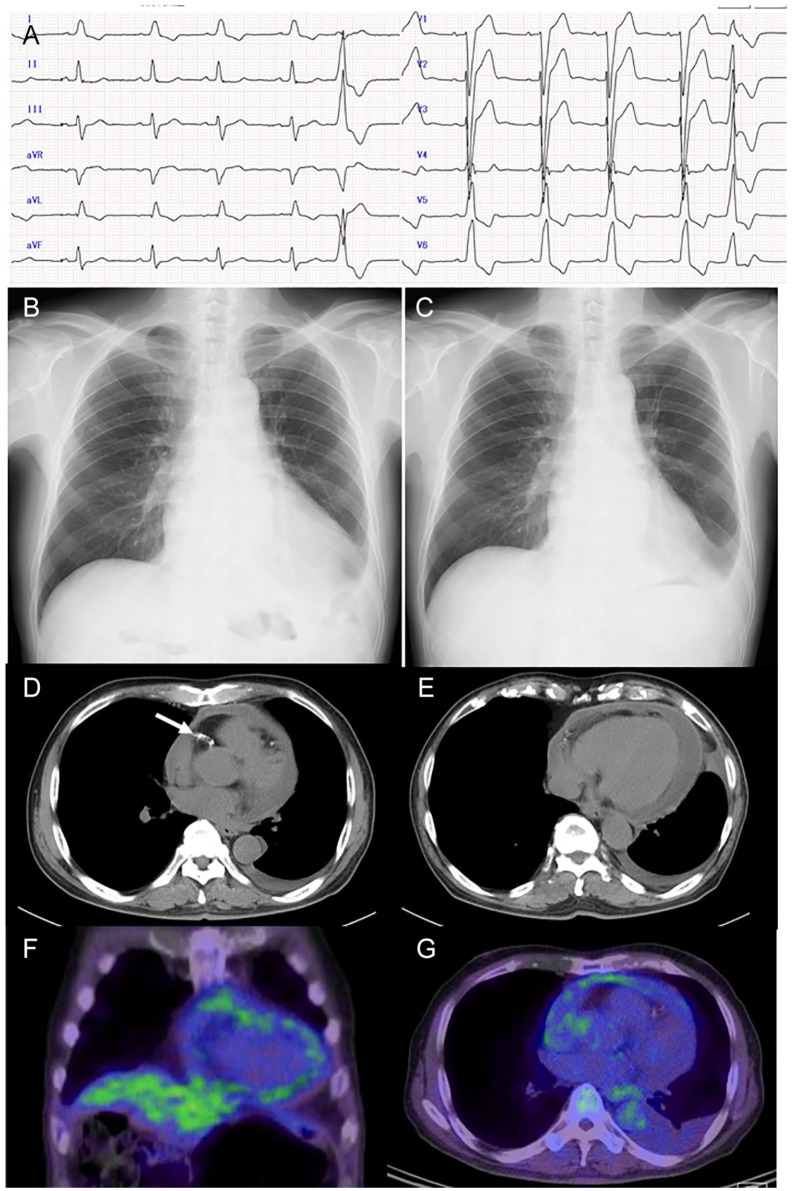

Figure 2.

Electrocardiogram (A), chest plain x-ray (B), and computed tomography (D, E) on the day of admission, fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) 4 days later (F, G), and chest plain x-ray 11 days later at outpatient visit (C). Not regular sinus rhythm at pulse rate of 65 beats per minute with left bundle branch block and an isolated ventricular extrasystole (A), cardiac shadow enlargement which decreased spontaneously in 11 days (B, C), pericardial effusion (D, E) and coronary stent (arrow in D), and multiple uptake sites in the pericardium in the coronal image (F) and axial image (G) of FDG-PET.

The differential diagnoses for pericardial effusion that were listed on the admission were infection including tuberculosis, autoimmune diseases, and metastatic malignancy. Computed tomographic (CT) scan from the thorax, abdomen, to pelvis demonstrated no mass lesions. The pericardial effusion and a small volume of pleural effusion on the left side were shown (Figure 2D, E). Whole-body 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) disclosed many spotty uptakes with the maximum of standardized uptake value (SUVmax) around 2.0 in the pericardial effusion (Figure 2F, G). No other abnormal uptake was noted systemically. As blood tests for low blood sodium, the measurements of aldosterone, cortisol, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and plasma renin activity were all within normal limits. As checkups for autoimmune diseases, antinuclear antibody was positive at 2.84 ratio, Sjogren Syndrome-A (SS-A) positive at 225 U/mL, and cardiolipin antibody positive at 19.3 U/mL. Serum IgG was elevated to 2380 mg/dL and IgG4 was also elevated mildly to 141 mg/dL. Pericardiocentesis was planned as a diagnostic procedure but was not done based on the following reasons: (1) the patient was healthy at the old age and had no symptoms; (2) the volume of pericardial effusion tended to decrease from the initial visit (Figure 2B, 2C); (3) the heart showed good function of expansion in the present volume of pericardial effusion; and (4) the patient denied pericardiocentesis, based on his evaluation of the risk of the procedure. He was thus discharged in several days and followed at the outpatient clinic. He underwent dental treatment (Figure 1B, C), and the pericardial effusion resolved completely in a month. He was healthy in 6 years until the last follow-up at the age of 92 years.

Discussion

This healthy aged patient who was followed by a cardiologist showed a small volume of pericardial effusion for 5 years and experienced gradual increase in the pericardial fluid in a month. In the same period, he had persistent mild periodontitis in the background of diabetes mellitus which was controlled around the 7% level of hemoglobin A1c. In parallel with the increase in pericardial effusion, he experienced exacerbation of periodontitis, leading to cheek swelling and mastication problems. Oral administration of antibiotics for a week resulted in relative subsidence of periodontal signs and symptoms and also led to the decrease in pericardial effusion. The sputum tests around this time detected a large number of Streptococcus species. The temporal association of the increase in pericardial effusion with the exacerbation of periodontitis suggests causal relationship of periodontitis and pericardial effusion after the other causes have been excluded in the differential diagnoses. Oral Streptococcus species which are famous for causing infective endocarditis might be responsible for pericardial effusion in this patient, although the evidence is weak. In this context, the causal relationship of oral bacteria with pericarditis would be further supported by the previous study that the same bacterial strains by DNA typing with oral bacteria were identified in the pericardial fluid of 22 subjects at forensic autopsy. 25

In the differential diagnoses, he did not have any sign of autoimmune diseases while he had the background of positive antinuclear antibody, SS-A, and cardiolipin antibody. Carcinomatous pericarditis is difficult to be excluded completely. The patient had no findings in upper and lower digestive tract endoscopic examinations and showed no mass in the thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic CT. FDG-PET showed pericardial uptakes, suggestive of inflammation or metastatic cancer,26-31 but detected no other abnormal uptake in the whole body. Under the circumstances, the possibility of carcinomatous pericarditis would be low because pericardial effusion resolved spontaneously in this patient. This study also supports that FDG-PET would be useful to determine the unknown cause of pericardial effusion although the examination is expensive at cost.26-31

As a tendency in aged people, the present patient did not have any symptoms such as fever and general fatigue. However, it should be noted that his pulse rate increased to 65 beats per minute, compared with his usual status around 50. Cheek swelling on the right side in this patient would not be noticed in the background of skin loosening in the cheek which is often seen in aged people. An increase in the pulse rate was a sign of his illness, together with CRP elevation and relative increase in neutrophils in the not-so-elevated white blood cell count.

To analyze similar cases, PubMed and Google Scholar were searched for the key words: pericarditis (pericardial effusion) and periodontitis (periodontal disease). The Japanese literature was searched for the same key words in the bibliographic database of medical literature in Japanese (Igaku Chuo Zasshi, Japana Centra Revuo Medicina, Ichushi-Web), published by the Japan Medical Abstracts Society (JAMAS, Tokyo, Japan). Old literature was collected from references cited in the articles identified during the literature search. Table 1 summarizes 8 patients with sufficient description,17-24 together with the present case. The 9 patients, including the present patient, were 5 men and 3 women with the age at the initial visit ranging from 19 to 86 years (median, 45 years) while the sex and the age of the remaining one person were not described. All showed pericardial effusion and pericardiocentesis was done in 4 patients. Mediastinitis was noted in 5 patients, and constrictive pericarditis in 3. All 9 patients, except for the present patient (case 9), underwent surgical interventions such as thoracotomy and pericardial drainage. As for the dental diagnoses, 5 patients had teeth caries frequently in the mandibular molar teeth while 4 patients were described to have periodontitis or suspected of periodontitis.

Table 1.

Review of 8 Patients With Pericarditis in Association With Periodontitis, Including the Present Patient.

| Case no. /sex/age at onset | Presenting symptoms | Diagnosis of pericardial effusion | Pericardiocentesis | Findings in pericardial effusion | Other sites involvement | Oral cavity findings and treatment | Treatment | Outcome and complications | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/Male/49 | Cough, chest pain, orthopnea, diarrhea | Ultrasonography Chest plain x-ray |

No | Leukocytes Fusobacterium nucleatum |

None | Dental caries and pyorrhea | Antimicrobials Pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis |

Healthy in 3 weeks | Truant et al 17 |

| 2/Male/30 | Fever, chest pain, cough, dyspnea | Ultrasonography Chest plain x-ray |

Yes | Gram-positive cocci Neutrophils Peptococcus magnus |

Mediastinitis (necrotic purulent debris) |

Carious molars with apical abscess Tooth extraction |

Antimicrobials Thoracostomy tube insertion Thoracotomy, pericardial stripping for constrictive pericarditis, mediastinal lavage |

Healthy in 2 months | Plelps and Jacobs 18 |

| 3/Unknown/- | Left cheek and neck swelling Dyspnea |

Chest plain x-ray Emergency surgery |

No | Pseudomonas from mediastinal drain | Mediastinitis | Carious teeth, mouth floor pus Total teeth extraction |

Antimicrobials Thoracotomy Mediastinal and pericardial drains |

Healthy | Zachariades et al 19 |

| 4/Female/41 | Chest pain Dyspnea Weight gain |

Chest plain x-ray Ultrasonography CT |

Yes | Neutrophils No acid-fast bacilli |

Mediastinitis | Suspicious of periodontal disease | Antimicrobials Pericardial drain Actinomyces in pericardial soft tissue mass extirpation Thoracostomy tube insertion |

Healthy in 3 years | Fife et al 20 |

| 5/Male/40 | Left mandibular and neck swelling Hoarseness, fever, dysphagia |

Chest plain x-ray CT |

No | Not available | Mediastinitis | Left submandibular abscess from molars Aerobic and anaerobic flora of pus Mandibular molar extraction |

Antimicrobials Tracheostomy Mediastinotomy Thoracotomy |

Healthy Ankylosing spondylitis Both hip replacement 3 months earlier |

Pappa and Jones 21 |

| 6/Female/19 | Left cheek and submandibular swelling Chest pain and dyspnea next day |

Chest plain x-ray CT |

No | Pus | Mediastinitis Reactive (aseptic) ascites |

Left mandibular carious second molar and semi-impacted third molar Incisional drainage of buccal abscess |

Antimicrobials Thoracotomy Thoracic drain |

Not described | Rallis et al 22 |

| 7/Male/61 | Dyspnea, cough Fever, chest pain |

Chest plain x-ray Ultrasonography |

Yes | Pus Gram-positive cocci Actinomyces odontolyticus |

None | Suspicious of periodontal disease Dentures |

Antimicrobials Pericardial drain |

Chemotherapy and radiation for right upper lobe squamous carcinoma Dead from lung cancer |

Mack et al 23 |

| 8/Female/56 | Chest pain | Ultrasonography CT |

Yes | Pus Neutrophils MSSA |

Infective thoracic aortic aneurysm | Periodontitis | Antimicrobials Thoracotomy Aortic arch replacement Pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis |

Healthy in 8 months | Sato et al 24 |

| 9/Male/86 | Right cheek swelling | Chest plain x-ray Ultrasonography CT, FDG-PET |

No | Not available | Right pleural effusion | Mandibular periodontitis on the right side Streptococcus in sputum |

Antimicrobials | Healthy in 6 years | This case |

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; FDG-PET, fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography; MSSA, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus.

Causative agents were described in all 9 patients except for one (case 6). Fusobacterium nucleatum, Peptococcus magnus, Pseudomonas species, Actinomyces odontolyticus, and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus were identified in pericardial fluid which was obtained by pericardiocentesis or pericardiectomy. Actinomyces was identified in the pericardial soft tissue mass which was resected in 1 patient (case 4). Streptococcus species which was isolated from the sputum was suspected of a causative agent in the present patient (case 9) who did not undergo surgical procedures such as pericardiocentesis. In another patient, causative agents were stated as aerobic and anaerobic flora of pus (case 5). Pathogens in oral bacterial flora can travel from the oral cavity to the pharynx and directly reach the mediastinum in severe purulent oral conditions. On the other hand, oral pathogens can enter the bloodstream and reach the pericardial space in periodontitis with alveolar bone destruction, as seen in the present patient.16,32,33

The present patient, as well as the other patients in the literature, indicates that periodontal diseases would serve as a precipitating factor for the development of not only the well-known infective endocarditis but also pericardial effusion or pericarditis. In the other fields of medicine, for instance, in ophthalmology, periodontal diseases may also cause endogenous endophthalmitis by probable bloodstream infection with Aspergillus and Acanthamoeba.32,33 Oral hygiene should be checked in medical interview and systemic evaluations of patients with pericardial effusion. The earlier detection of oral problems would lead to the earlier diagnosis of pericardial effusion and hence to the earlier treatment to avoid devastating results such as mediastinitis and constrictive pericarditis which were described in the literature.17-24

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: Data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Author Contributions: T.M., as an ophthalmologist, suggested periodontal origin of illness and wrote the manuscript. C.N.M., as an orthodontist, suggested periodontal origin of illness. N.M., as a professor emeritus of ophthalmology, presented history of illness. A.M., as a dentist, treated the patient. M.M. and H.I., as cardiologists, examined and followed the patient. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval: Ethics committee review was not applicable due to the case report design, based on the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects, issued by the Government of Japan.

Informed Consent: Oral informed consent was obtained from the patient for his anonymized information to be published in this article.

ORCID iD: Toshihiko Matsuo  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6570-0030

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6570-0030

References

- 1. Kinane DF, Lowe GD. How periodontal disease may contribute to cardiovascular disease. Periodontol 2000. 2000;23: 121-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fowler EB, Breault LG, Cuenin MF. Periodontal disease and its association with systemic disease. Military Med. 2001;166:85-89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Seymour GJ, Ford PJ, Cullinan MP, Leishman S, Yamazaki K. Relationship between periodontal infections and systemic disease. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007;13(suppl 4):3-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arigbede AO, Babatope BO, Bamidele MK. Periodontitis and systemic diseases: a literature review. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2012;16(4):487-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Winning L, Linden GJ. Periodontitis and systemic disease. BDJ Team. 2015;2:15163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Im SI, Heo J, Kim BJ, et al. Impact of periodontitis as representative of chronic inflammation on long-term clinical outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation. Open Heart. 2018; 5(1):e000708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carrizales-Sepúlveda EF, Ordaz-Farías A, Vera-Pineda R, Flores-Ramírez R. Periodontal disease, systemic inflammation and the risk of cardiovascular disease. Heart Lung Circ. 2018;27(11):1327-1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bui FQ, Almeida-da-Silva CLC, Huynh B, et al. Association between periodontal pathogens and systemic disease. Biomed J. 2019;42(1):27-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rahimi A, Afshari Z. Periodontitis and cardiovascular disease: a literature review. ARYA Atheroscler. 2021;17:1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pedersen PU, Larsen P, Håkonsen SJ. The effectiveness of systematic perioperative oral hygiene in reduction of postoperative respiratory tract infections after elective thoracic surgery in adults: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016;14(1):140-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kaga A, Ikeda T, Tachibana K, et al. An innovative oral management procedure to reduce postoperative complications. JTCVS Open. 2022;10:442-453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Skallsjö K, von Bültzingslöwen I, Hasséus B, et al. Oral health in patients scheduled for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in the Orastem study. PLoS One. 2023;18(5):e0285615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dhotre SV, Davane MS, Nagoba BS. Periodontitis, bacteremia and infective endocarditis: a review study. Arch Pediatr Infect Dis. 2017;5:e41067. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Carinci F, Martinelli M, Contaldo M, et al. Focus on periodontal disease and development of endocarditis. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2018;32(2)(suppl 1):143-147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thoresen T, Jordal S, Lie SA, et al. Infective endocarditis: association between origin of causing bacteria and findings during oral infection screening. BMC Oral Health. 2022;22:491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Horliana AC, Chambrone L, Foz AM, et al. Dissemination of periodontal pathogens in the bloodstream after periodontal procedures: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9(5): e98271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Truant AL, Menge S, Milliorn K, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum pericarditis. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;17:349-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Phelps R, Jacobs RA. Purulent pericarditis and mediastinitis due to Peptococcus magnus. JAMA. 1985;254:947-948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zachariades N, Mezitis M, Stavrinidis P, Konsolaki-Agouridaki E. Mediastinitis, thoracic empyema, and pericarditis as complications of a dental abscess: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;46(6):493-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fife TD, Finegold SM, Grennan T. Pericardial actinomycosis: case report and review. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13(1):120-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pappa H, Jones DC. Mediastinitis from odontogenic infection: a case report. Br Dent J. 2005;198:547-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rallis G, Papadakis D, Koumoura F, Gakidis I, Mihos P. Rare complications of a dental abscess. Gen Dent. 2006;54(1): 44-45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mack R, Slicker K, Ghamande S, et al. Actinomyces odontlyticus: rare etiology for purulent pericarditis. Case Rep Med. 2014;2014:734925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sato T, Okamoto Y, Yamamoto K, et al. Infectious thoracic aortic aneurysm and purulent pericarditis due to Staphylococcus aureus: report of a case. Kyobu Geka. 2022;75(2):146-149. (In Japanese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Louhelainen AM, Aho J, Tuomisto S, et al. Oral bacterial DNA findings in pericardial fluid. J Oral Microbiol. 2014;6:25835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Makis W, Ciarallo A, Hickeson M, et al. Spectrum of malignant pleural and pericardial disease on FDG PET/CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(3):678-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lawal I, Sathekge M. F-18 FDG PET/CT imaging of cardiac and vascular inflammation and infection. Br Med Bull. 2016; 120(1):55-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gerardin C, Mageau A, Benali K, et al. Increased FDG-PET/CT pericardial uptake identifies acute pericarditis patients at high risk for relapse. Int J Cardiol. 2018;271:192-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schonau V, Vogel K, Engbrecht M, et al. The value of 18F-FDG-PET/CT in identifying the cause of fever of unknown origin (FUO) and inflammation of unknown origin (IUO): data from a prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:70-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim MS, Kim EK, Choi JY, et al. Clinical utility of [18F]FDG-PET /CT in pericardial disease. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2019;21:107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hyeon CW, Yi HK, Kim EK, et al. The role of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography in the differential diagnosis of pericardial disease. Sci Rep. 2020;10:21524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Matsuo T, Nakagawa H, Matsuo N. Endogenous Aspergillus endophthalmitis associated with periodontitis. Ophthalmologica. 1995;209(2):109-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Matsuo T, Notohara K, Shiraga F, Yumiyama S. Endogenous amoebic endophthalmitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(1): 125-128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]