Abstract

Purpose

The prevalence of atopic diseases has increased in recent decades. A possible link between antibiotic use during pregnancy and childhood atopic disease has been proposed. The aim of this study is to explore the association of antibiotic exposure during pregnancy with childhood atopic diseases from a nationwide, population-based perspective.

Methods

This was a nationwide population-based cohort study. Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database was the main source of data. The pairing of mothers and children was achieved by linking the NHIRD with the Taiwan Maternal and Child Health Database. This study enrolled the first-time pregnancies from 2004 to 2010. Infants of multiple delivery, preterm delivery, and death before 5 years old were excluded. All participants were followed up at least for 5 years. Antenatal antibiotics prescribed to mothers during the pregnancy period were reviewed. Children with more than two outpatient visits, or one admission, with a main diagnosis of asthma, allergic rhinitis, or atopic dermatitis were regarded as having an atopic disease.

Results

A total of 900,584 children were enrolled in this study. The adjusted hazard ratios of antibiotic exposure during pregnancy to childhood atopic diseases were 1.12 for atopic dermatitis, 1.06 for asthma, and 1.08 for allergic rhinitis, all of which reached statistical significance. The trimester effect was not significant. There was a trend showing the higher the number of times a child was prenatally exposed to antibiotics, the higher the hazard ratio was for childhood atopic diseases.

Conclusions

Prenatal antibiotic exposure might increase the risk of childhood atopic diseases in a dose-dependent manner.

Keywords: Allergic rhinitis, Antibiotics, Asthma, Atopic dermatitis, Prenatal exposure

Introduction

With advances in medicine, antibiotics are commonly prescribed around the world [1]. The special physiology of pregnant women makes them more susceptible to infection, such as urinary tract infection. Thus, antibiotics are often used during the pregnancy period. It is estimated that up to 40% of pregnant women receive antibiotics prior to delivery [2, 3]. The prevalence of atopic diseases, such as food allergy, atopic dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis, has also increased globally in recent decades as a result of industrialization [4–6]. These allergic diseases not only seriously affect the quality of patients’ lives, but also cause a huge personal and socioeconomic burden [7].

A possible link has been suggested between the increasing use of antibiotics during pregnancy and the occurrence of atopic illnesses. The composition of an infant’s gut microbiome contributes to her subsequent immunological development. Alteration of the microbiome could lead to subsequent allergy diseases and obesity later in life [8–10]. The maternal microbiome determines the initial composition of the infant’s microbiome. Some studies reported that maternal antibiotic exposure during pregnancy could change infants’ microbiome [11, 12]. A matched case–control study found prenatal antibiotic exposure was associated with an increased risk of asthma [13]. However, large-scale studies on prenatal antibiotic exposure and atopic diseases later in life are still lacking.

The aim of this study was to explore the association of antibiotic exposure during pregnancy with childhood atopic diseases from a nationwide, population-based perspective.

Materials and methods

Study design and data source

This was a nationwide, population-based cohort study. Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) was the main source of data. Taiwan’s National Health Insurance (NHI) system was launched in 1995. It is a single-payer program with mandatory enrollment. The current coverage rate is 99.99% of Taiwan’s population (approximately 23.5 million). In 2002 , the NHIRD was established for research purposes. It contains all claims data from the NHI [14–16]. Since 2015, the Health and Welfare Data Center (HWDC) of Taiwan’s Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW) further integrated NHIRD with other health-related databases [17]. In this study, the pairing of mothers and children was achieved by linking the NHIRD with the Taiwan Maternal and Child Health Database (MCHD) of Taiwan’s Health Promotion Administration (HPA). The main data analyzed in this study were obtained from ambulatory care expenditures by visit (CD) files and inpatient expenditure by admission (DD) files from the NHIRD. Antibiotic exposure records were acquired from inpatient order (DO) files. For privacy protection and database reliability, Taiwan’s Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW) requires investigators to conduct on-site analysis. During the study period, diagnoses in the NHIRD were coded by the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) format.

Study population

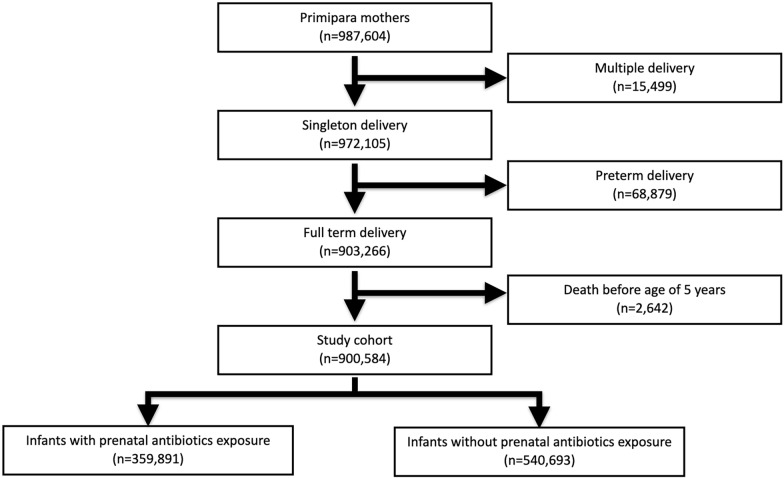

This nationwide cohort study only enrolled first-time pregnancies during the study period, from 2004 to 2010. We excluded infants of multiple delivery, preterm delivery, and death before 5 years old. Finally, a total of 906,942 infants were enrolled in the study cohort (Fig. 1). The cohort was followed up until the end of 2016. All children in this cohort were followed up for at least 5 years.

Fig. 1.

Composition of the study cohort. Only the first child in each family was enrolled. Premature infants and children of early death were excluded from analysis

Exposure to antenatal antibiotics

Antenatal antibiotic exposure was defined as a mother who received a medication with an ATC code (J01A, J01B, J01C, J01D, J01E, J01F, J01G, J01M, J01R, and J01X) during pregnancy. The timing of prescription (first, second, and third trimesters) and cumulative numbers of prescriptions were also recorded. We restricted the subgroup analysis to the timing of the initial exposure.

Outcome measurement

During the study period, the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD9-CM) was used for coding of each diagnosis. Children who visited the outpatient department more than twice or were admitted once with a primary diagnosis of asthma (ICD-9 code 493.9), allergic rhinitis (ICD-9 code 477.9), or atopic dermatitis (ICD-9 code 691.8), were regarded as having an atopic disease.

Covariates

Maternal age, mode of delivery, maternal comorbidities, maternal allergic diseases, pregnancy-related complications, and infants’ gender were collected as potential confounders.

Statistical analysis

The data were retrieved and analyzed using the SAS statistical package (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). Demographic data were described by the mean with standard deviation, or frequency and percentage. Continuous variables were compared using the independent t-test. The Pearson’s Chi-square test was applied for analyzing categorical data. Cumulative incidences of atopic diseases between groups were compared by the Kaplan–Meier method. Cox regression model was applied for calculating the hazard ratios of antibiotic prescription after adjusting for potential confounders. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

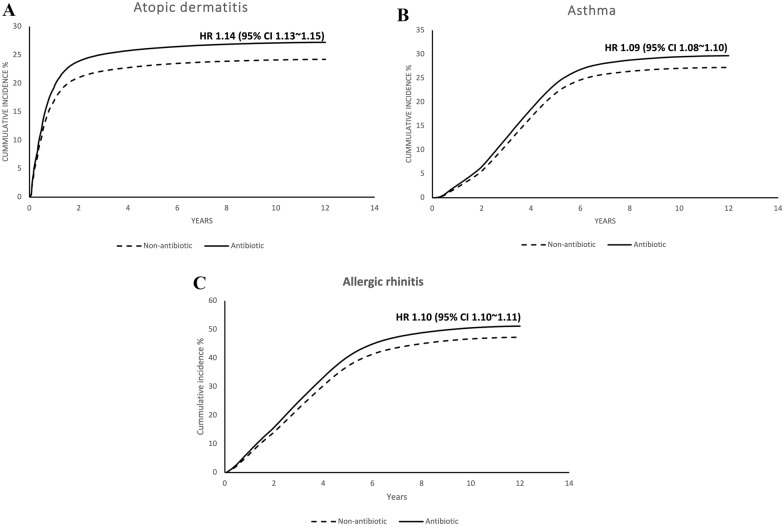

The cumulative incidences of atopic diseases

Of the 900,584 enrolled children, 359,891 (40.0%) were exposed to prenatal antibiotics. A comparison of the demographic data of these two groups revealed that the antibiotic exposure group had a slightly younger age of pregnancy, more Cesarean sections, more maternal comorbidities, more maternal allergic diseases, more pregnancy complications, and more male babies (Table 1). At the end of the study, the cumulative incidences of atopic diseases of the antibiotic exposure group were: 29.5% for atopic dermatitis, 30.5% for asthma, and 56.4% for allergic rhinitis. In the non-antibiotics group, the cumulative incidences were: 26.4% for atopic dermatitis, 28.4% for asthma, and 52.8% for allergic rhinitis (Fig. 2). The adjusted hazard ratio of antibiotics exposure during pregnancy to childhood atopic diseases were 1.12 for atopic dermatitis, 1.06 for asthma, and 1.08 for allergic rhinitis. All of them reached statistical significance (Table 2). Univariate analysis and actual numbers in each category are listed in Table 3.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study subjects

| Characteristic | Non-antibiotics group (422,740) | Antibiotics group (484,202) | Total | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Maternal age (years) | < 0.001 | |||

| < 25 | 72,366 (17.1) | 90,395 (18.7) | 162,761 | |

| 25–29 | 159,287 (37.7) | 180,320 (37.2) | 339,607 | |

| 30–34 | 140,761 (33.3) | 151,804 (31.4) | 292,565 | |

| ≥ 35 | 50,326 (11.9) | 61,683 (12.7) | 112,009 | |

| Mode of delivery | < 0.001 | |||

| Vaginal delivery | 313,169 (74.1) | 291,785 (60.3) | 604,954 | |

| Cesarean section | 109,571 (25.9) | 192,417 (39.7) | 301,988 | |

| Maternal comorbidity | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1822 (0.4) | 3284 (0.7) | 5,106 | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1752 (0.4) | 3452 (0.7) | 5,204 | < 0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 3365 (0.8) | 6074 (1.3) | 9,439 | < 0.001 |

| Maternal allergic disease | ||||

| Asthma | 8954 (2.1) | 15,594 (3.2) | 24,548 | < 0.001 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 65,455 (15.5) | 95,671 (19.8) | 161,126 | < 0.001 |

| Atopic dermatitis | 7223 (1.7) | 11,070 (2.3) | 18,293 | < 0.001 |

| Pregnancy-related complication | ||||

| Anemia | 15,979 (3.8) | 24,690 (5.1) | 40,669 | < 0.001 |

| Gestational diabetes mellitus | 6217 (1.5) | 7401 (1.5) | 13,618 | 0.024 |

| Gestational hypertension | 1485 (0.4) | 2389 (0.5) | 3,874 | < 0.001 |

| Pre-eclampsia or eclampsia | 2986 (0.7) | 5390 (1.1) | 8,376 | < 0.001 |

| Placenta previa or abruptio placentae | 9664 (2.3) | 15,581 (3.2) | 25,245 | < 0.001 |

| Neonatal gender | < 0.001 | |||

| Female | 205,227 (48.5) | 231,737 (47.9) | 436,964 | |

| Male | 217,513 (51.5) | 252,465 (52.1) | 469,978 | |

| Timing of antibiotics exposure | ||||

| 1st trimester | 288,434 (59.6) | 288,434 | ||

| 2nd trimester | 30,173 (6.2) | 30,173 | ||

| 3rd trimester | 165,595 (34.2) | 165,595 | ||

| Cumulative number of antibiotics | ||||

| 1 time | 279,783 (57.8) | 279,783 | ||

| 2 times | 108,969 (22.5) | 108,969 | ||

| ≥ 3 times | 95,450 (19.7) | 95,450 |

Fig. 2.

Cumulative incidences of atopic diseases with or without prenatal antibiotics: A atopic dermatitis; B asthma; C allergic rhinitis. Prenatal antibiotics exposure increases the cumulative risk in all three atopic diseases. CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio

Table 2.

Adjusted hazard ratios of prenatal antibiotics for childhood atopic diseases by Cox regression models*

| Variables | Asthma | Allergic rhinitis | Atopic dermatitis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aHR | 95%CI | aHR | 95%CI | aHR | 95%CI | ||||

| Antibiotics | 1.06 | 1.05 | 1.07 | 1.08 | 1.07 | 1.09 | 1.12 | 1.11 | 1.13 |

| Maternal age | |||||||||

| < 25 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 25–29 | 1.13 | 1.12 | 1.14 | 1.27 | 1.26 | 1.28 | 1.17 | 1.15 | 1.18 |

| 30–34 | 1.10 | 1.09 | 1.11 | 1.32 | 1.31 | 1.33 | 1.22 | 1.20 | 1.23 |

| ≥ 35 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 1.21 | 1.20 | 1.23 | 1.10 | 1.09 | 1.12 |

| Mode of delivery | |||||||||

| Cesarean section | 1.05 | 1.04 | 1.05 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.03 | 1.05 | 1.04 | 1.06 |

| Maternal comorbidity | |||||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.03 | 0.98 | 1.08 | 1.03 | 0.99 | 1.06 | 1.02 | 0.98 | 1.07 |

| Hypertension | 1.02 | 0.98 | 1.07 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 1.04 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.10 | 1.06 | 1.13 | 1.15 | 1.12 | 1.18 | 1.17 | 1.13 | 1.21 |

| Maternal allergic disease | |||||||||

| Asthma | 1.58 | 1.55 | 1.61 | 1.18 | 1.16 | 1.20 | 1.18 | 1.15 | 1.20 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 1.31 | 1.30 | 1.32 | 1.53 | 1.52 | 1.54 | 1.29 | 1.28 | 1.31 |

| Atopic dermatitis | 1.06 | 1.03 | 1.08 | 1.12 | 1.10 | 1.14 | 1.55 | 1.52 | 1.59 |

| Pregnancy-related complication | |||||||||

| Anemia | 1.02 | 0.97 | 1.07 | 0.98 | 0.94 | 1.01 | 0.96 | 0.91 | 1.01 |

| Gestational diabetes mellitus | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.02 | 1.10 | 1.08 | 1.12 | 1.15 | 1.12 | 1.18 |

| Gestational hypertension | 1.06 | 0.95 | 1.18 | 0.97 | 0.90 | 1.06 | 1.02 | 0.91 | 1.14 |

| Pre-eclampsia or eclampsia | 0.91 | 0.84 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.94 | 1.06 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 1.09 |

| Placenta previa and abruptio placentae | 1.10 | 1.07 | 1.13 | 1.08 | 1.06 | 1.10 | 1.08 | 1.05 | 1.11 |

| Male gender | 1.33 | 1.32 | 1.34 | 1.29 | 1.29 | 1.30 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.05 |

aHR adjusted hazard ratio, CI confidence intervals

*Models adjusted for maternal age, mode of delivery, maternal comorbidity, maternal allergic disease, and pregnancy-related complications

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of factors associated with childhood atopic diseases

| Variables | Asthma | Allergic rhinitis | Atopic dermatitis | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | HR | 95%CI | No | Yes | HR | 95%CI | No | Yes | HR | 95%CI | ||||

| Antibiotics | |||||||||||||||

| No | 387,072 | 153,621 | 1.00 | 255,452 | 285,241 | 1.00 | 397,702 | 142,991 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 250,257 | 109,634 | 1.09 | 1.08 | 1.10 | 156,819 | 203,072 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.11 | 253,788 | 106,103 | 1.14 | 1.13 | 1.15 |

| Maternal age | |||||||||||||||

| < 25 | 118,746 | 44,538 | 1.00 | 85,882 | 77,402 | 1.00 | 123,648 | 39,636 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 25–29 | 235,722 | 102,876 | 1.14 | 1.13 | 1.16 | 150,012 | 188,586 | 1.29 | 1.28 | 1.30 | 243,561 | 95,037 | 1.18 | 1.17 | 1.20 |

| 30–34 | 202,919 | 86,010 | 1.12 | 1.11 | 1.14 | 125,613 | 163,316 | 1.35 | 1.33 | 1.36 | 204,380 | 84,549 | 1.24 | 1.23 | 1.26 |

| ≥ 35 | 79,942 | 29,831 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 50,764 | 59,009 | 1.25 | 1.23 | 1.26 | 79,901 | 29,872 | 1.14 | 1.12 | 1.15 |

| Mode of delivery | |||||||||||||||

| Vaginal delivery | 427,765 | 172,911 | 1.00 | 278,617 | 322,059 | 1.00 | 437,872 | 162,804 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Cesarean section | 209,564 | 90,344 | 1.06 | 1.05 | 1.07 | 133,654 | 166,254 | 1.06 | 1.05 | 1.07 | 213,618 | 86,290 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 1.08 |

| Maternal comorbidity | |||||||||||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 3934 | 1820 | 1.11 | 1.06 | 1.16 | 2401 | 3353 | 1.14 | 1.10 | 1.18 | 3978 | 1776 | 1.14 | 1.09 | 1.20 |

| Hypertension | 3976 | 1785 | 1.09 | 1.04 | 1.14 | 2606 | 3155 | 1.03 | 0.99 | 1.07 | 4055 | 1706 | 1.09 | 1.04 | 1.15 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 7842 | 3891 | 1.18 | 1.15 | 1.22 | 4408 | 7325 | 1.28 | 1.26 | 1.31 | 7770 | 3963 | 1.28 | 1.25 | 1.33 |

| Maternal allergic disease | |||||||||||||||

| Asthma | 14,592 | 11,887 | 1.80 | 1.77 | 1.83 | 9016 | 17,463 | 1.45 | 1.43 | 1.47 | 17,064 | 9415 | 1.37 | 1.35 | 1.40 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 112,758 | 62,428 | 1.38 | 1.37 | 1.39 | 58,829 | 116,357 | 1.58 | 1.57 | 1.59 | 116,308 | 58,878 | 1.35 | 1.34 | 1.37 |

| Atopic dermatitis | 13,737 | 6451 | 1.14 | 1.11 | 1.16 | 8099 | 12,089 | 1.22 | 1.19 | 1.24 | 11,928 | 8260 | 1.65 | 1.62 | 1.69 |

| Pregnancy-related complication | |||||||||||||||

| Anemia | 3556 | 1507 | 1.04 | 0.99 | 1.09 | 2375 | 2688 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 1.02 | 3691 | 1372 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 1.03 |

| Gestational diabetes mellitus | 13,180 | 5417 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.03 | 7752 | 10,845 | 1.15 | 1.13 | 1.17 | 12,744 | 5853 | 1.18 | 1.15 | 1.21 |

| Gestational hypertension | 731 | 327 | 1.09 | 0.98 | 1.22 | 487 | 571 | 1.02 | 0.94 | 1.11 | 750 | 308 | 1.08 | 0.96 | 1.20 |

| Pre-eclampsia or eclampsia | 1283 | 502 | 0.96 | 0.88 | 1.05 | 799 | 986 | 1.04 | 0.97 | 1.10 | 1269 | 516 | 1.06 | 0.98 | 1.16 |

| Placenta previa and abruptio placentae | 13,930 | 6615 | 1.13 | 1.10 | 1.16 | 8647 | 11,898 | 1.13 | 1.10 | 1.15 | 14,293 | 6252 | 1.12 | 1.09 | 1.15 |

| Neonatal gender | |||||||||||||||

| Female | 321,925 | 111,950 | 1.00 | 218,970 | 214,905 | 1.00 | 315,634 | 118,241 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Male | 315,404 | 151,305 | 1.33 | 1.32 | 1.34 | 193,301 | 273,408 | 1.29 | 1.28 | 1.30 | 335,856 | 130,853 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.05 |

CI confidence intervals, HR hazard ratio

Timing of prenatal antibiotic exposure and childhood atopic diseases

To investigate how the timing of antibiotic prescription affected the incidences of childhood atopic diseases, we further stratified the infants into three groups according to their first-time exposure to antibiotics during the pregnancy course. After adjusting for confounders, including maternal age, mode of delivery, preterm delivery, maternal comorbidity, maternal allergic disease, pregnancy-related complications, and neonatal gender, the hazard ratios for asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis were 1.07, 1.09, and 1.13 for the first trimester, 1.06, 1.06, and 1.07 for the second trimester, and 1.02, 1.04, and 1.06 for the third trimester. Although all these hazard ratios reached statistical significance, the timing of exposure did not affect the magnitude of risk for childhood atopic diseases (Table 4).

Table 4.

Adjusted hazard ratios of prenatal antibiotics for childhood atopic diseases by Cox regression models*

| Asthma | Allergic rhinitis | Atopic dermatitis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95%CI | HR | 95%CI | HR | 95%CI | |

| Stratified by timing of prescribing antibiotics | ||||||

| 1st trimester | 1.07 | 1.06 ~ 1.08 | 1.09 | 1.08 ~ 1.09 | 1.13 | 1.12 ~ 1.14 |

| 2nd trimester | 1.06 | 1.03 ~ 1.08 | 1.06 | 1.05 ~ 1.08 | 1.07 | 1.04 ~ 1.09 |

| 3rd trimester | 1.02 | 0.99 ~ 1.04 | 1.04 | 1.02 ~ 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.04 ~ 1.09 |

| Stratified by cumulative times of antibiotics prescription | ||||||

| 1 time | 1.04 | 1.04 ~ 1.05 | 1.06 | 1.06 ~ 1.07 | 1.08 | 1.07 ~ 1.09 |

| 2 times | 1.06 | 1.05 ~ 1.08 | 1.09 | 1.08 ~ 1.10 | 1.13 | 1.11 ~ 1.14 |

| ≥ 3 times | 1.11 | 1.09 ~ 1.12 | 1.12 | 1.11 ~ 1.13 | 1.20 | 1.19 ~ 1.22 |

*Model adjusted for maternal age, mode of delivery, preterm delivery, maternal comorbidity, maternal allergic disease, pregnancy-related complication, neonatal gender; CI confidence interval

Cumulative number of times of prenatal antibiotic exposure and childhood atopic diseases

We further stratified the children according to their cumulative number of times of prenatal antibiotics exposure to test if a dose-dependent effect existed. After adjusting for confounders, including maternal age, mode of delivery, preterm delivery, maternal comorbidity, maternal allergic disease, pregnancy-related complication, and neonatal gender, the hazard ratios for asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis were 1.04, 1.06, 1.08 for one exposure, 1.06, 1.09, 1.13 for two exposures, and 1.11, 1.12, 1.20 for exposure more than 3 times. A trend was revealed showing the higher the number of times an infant was prenatally exposed to antibiotics, the higher the hazard ratio was for childhood atopic diseases (Table 4).

Types of delivery and risk for childhood atopic diseases

We stratified the children according to their types of delivery. After adjusting for potential confounders, including maternal age, mode of delivery, preterm delivery, maternal comorbidity, maternal allergic disease, pregnancy-related complication, and neonatal gender, the hazard ratios for asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis were 1.07, 1.08, 1.12 for vaginal delivery and 1.06, 1.08, 1.12 for Cesarean section (Table 5). The risk raised by antibiotics exposure was not modified by types of delivery.

Table 5.

Adjusted hazard ratios of prenatal antibiotics for childhood atopic diseases, stratified by types of delivery*

| Variables | Asthma | Allergic rhinitis | Atopic dermatitis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95%CI | HR | 95%CI | HR | 95%CI | ||||

| Types of delivery | |||||||||

| Vaginal delivery | 1.07 | 1.06 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.09 | 1.12 | 1.11 | 1.13 |

| Cesarean section | 1.06 | 1.04 | 1.07 | 1.08 | 1.07 | 1.09 | 1.12 | 1.11 | 1.14 |

*Model adjusted for maternal age, mode of delivery, preterm delivery, maternal comorbidity, maternal allergic disease, pregnancy-related complication, neonatal gender

Discussion

This nationwide, population-based cohort study reveals that prenatal antibiotic exposure increases the risk of childhood atopic disease. A dose-dependent effect was revealed by the positive correlation between the cumulative number of times antibiotics were prescribed and the risk of atopic diseases. The increased risk of atopy associated with antibiotic exposure was not affected by different trimesters. This study provides comprehensive evidence that the pathogenesis of childhood allergic diseases may begin in early pregnancy, according to population-based data.

Antibiotic exposure in mid-to-late pregnancy was consistently associated with childhood asthma in a Danish birth cohort study [18]. Trimester effects have also been reported in several smaller-scale studies [19–21]. However, a meta-analysis revealed a positive association between prenatal antibiotic use in every trimester and the occurrence of childhood asthma [22]. In our study, trimester effects were assessed, but no significant differences in hazard ratios were found among the trimesters. This apparent inconsistency in findings might be explained by the different follow-up periods and different disease definitions used in the studies. Prenatal antibiotic exposure has also been reported to increase the risk of atopic dermatitis and hay fever [23, 24]. However, the trimester effects were not analyzed. Our study also reported that risk of allergic rhinitis was positively associated with prenatal antibiotic exposure. Respiratory tract infections were the most common indication for prenatal antibiotics use in our study (Appendix Table 6). Subgroup analysis by different kinds of antibiotics is added in Appendix Table 7. There are no significant differences between groups. Only quinolone shown borderline statistical significance in asthma. Vaginal delivery exposes the newborn to the maternal gut microbiota directly during birth, which may have a protect effect than in cases of cesarean section.

Table 6.

The top 20 indication for prenatal antibiotics

| ICD9 | Diagnosis | n | Percent | Cumulative numbers | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 465 | Acute pharyngitis | 46,281 | 12.86 | 46,281 | 12.86 |

| 463 | Tonsilitis | 24,645 | 6.85 | 70,926 | 19.71 |

| 461 | Sinusitis | 22,190 | 6.17 | 93,116 | 25.88 |

| 616 | Inflammatory disease of cervix, vagina, and vulva | 20,439 | 5.68 | 113,555 | 31.56 |

| 599 | UTI | 18,369 | 5.11 | 131,924 | 36.67 |

| V22 | Normal pregnancy | 16,239 | 4.51 | 148,163 | 41.18 |

| 595 | Cystitis | 15,738 | 4.37 | 163,901 | 45.55 |

| 789 | Abdominal pain | 13,140 | 3.65 | 177,041 | 49.21 |

| 614 | Inflammatory disease of ovary, fallopian tube, pelvic cellular tissue, and peritoneum | 10,756 | 2.99 | 187,797 | 52.19 |

| 523 | Gingival and periodontal diseases | 8659 | 2.41 | 196,456 | 54.6 |

| 626 | Disorders of menstruation and other abnormal bleeding from female | 8168 | 2.27 | 204,624 | 56.87 |

| 466 | Acute bronchitis and bronchiolitis | 7897 | 2.19 | 212,521 | 59.07 |

| 640 | Hemorrhage in early pregnancy | 7663 | 2.13 | 220,184 | 61.2 |

| 706 | Diseases of sebaceous glands | 6862 | 1.91 | 227,046 | 63.1 |

| 462 | Pharyngitis, acute | 6282 | 1.75 | 233,328 | 64.85 |

| 644 | Early or threatened labor | 6033 | 1.68 | 239,361 | 66.53 |

| 487 | Influenza | 5406 | 1.5 | 244,767 | 68.03 |

| 646 | Other complications of pregnancy, not elsewhere classified | 4905 | 1.36 | 249,672 | 69.39 |

| 460 | Acute nasopharyngitis (common cold) | 4894 | 1.36 | 254,566 | 70.75 |

| 558 | Other noninfectious gastroenteritis and colitis | 4764 | 1.32 | 259,330 | 72.08 |

Table 7.

Subgroup analysis by different kinds of antibiotics

| Variables | Asthma | Allergic rhinitis | Atopic dermatitis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95%CI | HR | 95%CI | HR | 95%CI | ||||

| Type of antibiotics | |||||||||

| J01A (tetracyclines) | 1.09 | 1.06 | 1.12 | 1.13 | 1.11 | 1.15 | 1.19 | 1.16 | 1.22 |

| J01B (amphenicols) | 1.09 | 1.04 | 1.15 | 1.08 | 1.04 | 1.12 | 1.08 | 1.03 | 1.14 |

| J01C (beta-lactam antibacterials, penicillins) | 1.08 | 1.07 | 1.10 | 1.08 | 1.07 | 1.09 | 1.11 | 1.10 | 1.12 |

| J01D (other beta-lactam antibiotics) | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.05 | 1.08 | 1.07 | 1.09 | 1.12 | 1.11 | 1.13 |

| J01E (sulfonamides and trimethoprim) | 1.08 | 1.04 | 1.12 | 1.13 | 1.10 | 1.16 | 1.10 | 1.05 | 1.14 |

| J01F (macrolides, lincosamides and streptogramins) | 1.06 | 1.05 | 1.08 | 1.09 | 1.08 | 1.11 | 1.13 | 1.11 | 1.15 |

| J01G (aminoglucosides) | 1.12 | 1.05 | 1.20 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 1.04 | 1.02 | 0.95 | 1.10 |

| J01M (quinolone) | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.06 | 1.07 | 1.04 | 1.10 | 1.13 | 1.09 | 1.17 |

| J01R (combination) | |||||||||

| J01X (other antibacterials) | 1.05 | 1.00 | 1.10 | 1.08 | 1.04 | 1.12 | 1.11 | 1.06 | 1.17 |

Model adjusted for maternal age, mode of delivery, preterm delivery, maternal comorbidity, maternal allergic disease, pregnancy-related complication, neonatal gender

More studies are needed to elucidate the mechanism underlying the positive association between use of prenatal antibiotics and childhood atopic diseases. The hygiene hypothesis may partially explain it [25]. According to the hygiene hypothesis the microbiota, i.e., the composition of the intestinal flora, which is established early in life, plays a crucial role in the development of the immune system in children [26]. The association between gut microbiota and allergic diseases has been reported in a number of studies [27, 28]. The microbial colonization of the fetus has been reported to occur as early as 11 weeks of gestation [29]. Thus, by inducing reductions and alterations in the fetal intestinal microbiota, exposure to antibiotics during pregnancy may affect immune system development, thereby increasing the likelihood of chronic disease [30, 31]. Animal studies have also shown that antibiotics could induce the transition from TH1/TH2 balance to TH2-dominant immunity. Nevertheless, oral administration of intestinal flora could prevent this process from developing [32, 33]. The risk of childhood asthma increases as the cumulative number of courses of prenatal antibiotics increases, according to a Canadian cohort study [34]. A dose-dependent effect has also been reported in a claims data analysis [31]. In our study, a similar trend was noted in all childhood allergic diseases. This further supports the notion that prenatal antibiotics may be causally linked with childhood atopic diseases, and that this relationship is not the result of the phenomenon of confounding by indication [35, 36].

The correlation between antibiotic exposure during pregnancy and childhood allergic diseases may be confounded by many factors. Maternal characteristics such as maternal age, maternal history of allergy, maternal smoking, delivery mode, and maternal education level have all been reported [23, 34, 35, 37, 38]. The strongest confounder may be maternal allergic disease, because atopy has a strong hereditary tendency. The strongest predictor of childhood atopic diseases is genetic inheritance from parents. If we include all siblings in this study. The analysis might be confounded by family clusters [39, 40] So, we included only the first child in each family. Preterm infants usually have more medical care need. So, we excluded them to prevent the confounding effect. If children did not survive more than 5 years, short follow-up time would confound the outcome analysis. As a result, we did not involve those infants of early death.

Our study had certain limitations. The data source was national health insurance claims data, which do not include laboratory data. The disease diagnosis was mainly decided by physicians’ coding. The validity of the diagnoses could not be confirmed because personal identification data are not permitted to be released from the data center. Thus, certain misclassifications may have existed. Because we used Cox regression model to analyze the cumulative hazard ratio between groups. However, Cox regression model (proportional hazard model) can only calculate the hazard ratio. Risk difference calculation can count the attributable risk proportion. It may be more valuable in public health policy making.

Abbreviations

- HPA

Health Promotion Administration

- HWDC

Health and Welfare Data Center

- ICD-9-CM

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

- MCHD

Maternal and Child Health Database

- MOHW

Ministry of Health and Welfare

- NHI

National Health Insurance

- NHIRD

National Health Insurance Research Database

Appendix

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Yi-Hsuan Lin, Ching-Heng Lin and Ming-Chih Lin. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Sheng-Kang Tai. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Taichung Veterans General Hospital Research Fund (Registration numbers TCVGH-1116503C, 1107309D, FCU1118025).

Availability of data and materials

In this study, the data analyzed are subject to the following licenses/restrictions: To protect patients’ identity and validate the reliability of the databases, investigators are required to perform onsite analysis at HWDC via remote connection to MOHW servers. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to Dr. Ching-Heng Lin, epid@vghtc.gov.tw.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Taichung Veterans General Hospital, which waived the need for informed consent (CE17178A-4). Patients or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of our research.

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.DeBolt CA, Johnson S, Harishankar K, Monro J, Kaplowitz E, Bianco A, Stone J. Antenatal corticosteroids decrease the risk of composite neonatal respiratory morbidity in planned early term Cesarean deliveries. Am J Perinatol. 2022;39:915–920. doi: 10.1055/a-1674-6198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ledger WJ, Blaser MJ. Are we using too many antibiotics during pregnancy? BJOG Int J Obstetr Gynaecol. 2013;120:1450–1452. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petersen I, Gilbert R, Evans S, Ridolfi A, Nazareth I. Oral antibiotic prescribing during pregnancy in primary care: UK population-based study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:2238–2246. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asher MI, Montefort S, Bjorksten B, Lai CK, Strachan DP, Weiland SK, Williams H, Group IPTS. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC Phases One and Three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet. 2006;368:733–743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69283-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dhami S, Sheikh A. Estimating the prevalence of aero-allergy and/or food allergy in infants, children and young people with moderate-to-severe atopic eczema/dermatitis in primary care: multi-centre, cross-sectional study. J R Soc Med. 2015;108:229–236. doi: 10.1177/0141076814562982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peters RL, Koplin JJ, Gurrin LC, Dharmage SC, Wake M, Ponsonby AL, Tang MLK, Lowe AJ, Matheson M, Dwyer T, Allen KJ, HealthNuts S. The prevalence of food allergy and other allergic diseases in early childhood in a population-based study: HealthNuts age 4-year follow-up. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(145–153):e148. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bahadori K, Doyle-Waters MM, Marra C, Lynd L, Alasaly K, Swiston J, FitzGerald JM. Economic burden of asthma: a systematic review. BMC Pulm Med. 2009;9:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-9-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milliken S, Allen RM, Lamont RF. The role of antimicrobial treatment during pregnancy on the neonatal gut microbiome and the development of atopy, asthma, allergy and obesity in childhood. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2019;18:173–185. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2019.1579795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tapiainen T, Koivusaari P, Brinkac L, Lorenzi HA, Salo J, Renko M, Pruikkonen H, Pokka T, Li W, Nelson K, Pirttila AM, Tejesvi MV. Impact of intrapartum and postnatal antibiotics on the gut microbiome and emergence of antimicrobial resistance in infants. Sci Rep. 2019;9:10635. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46964-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang M, Differding MK, Benjamin-Neelon SE, Ostbye T, Hoyo C, Mueller NT. Association of prenatal antibiotics with measures of infant adiposity and the gut microbiome. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2019;18:18. doi: 10.1186/s12941-019-0318-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller JE, Wu C, Pedersen LH, de Klerk N, Olsen J, Burgner DP. Maternal antibiotic exposure during pregnancy and hospitalization with infection in offspring: a population-based cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47:561–571. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyx272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pelzer E, Gomez-Arango LF, Barrett HL, Nitert MD. Review: maternal health and the placental microbiome. Placenta. 2017;54:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Metsala J, Lundqvist A, Virta LJ, Kaila M, Gissler M, Virtanen SM. Prenatal and post-natal exposure to antibiotics and risk of asthma in childhood. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45:137–145. doi: 10.1111/cea.12356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho Chan WS. Taiwan's healthcare report 2010. EPMA J. 2010;1:563–585. doi: 10.1007/s13167-010-0056-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin MC, Lai MS. Pediatricians' role in caring for preschool children in Taiwan under the national health insurance program. J Formos Med Assoc. 2009;108:849–855. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60416-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsieh CY, Su CC, Shao SC, Sung SF, Lin SJ, Kao Yang YH, Lai EC. Taiwan's National Health Insurance Research Database: past and future. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:349–358. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S196293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu TP, Liang FW, Huang YL, Chen LH, Lu TH. Maternal mortality in Taiwan: a nationwide data linkage study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0132547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uldbjerg CS, Miller JE, Burgner D, Pedersen LH, Bech BH. Antibiotic exposure during pregnancy and childhood asthma: a national birth cohort study investigating timing of exposure and mode of delivery. Arch Dis Child. 2021;106:888–894. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lapin B, Piorkowski J, Ownby D, Freels S, Chavez N, Hernandez E, Wagner-Cassanova C, Pelzel D, Vergara C, Persky V. Relationship between prenatal antibiotic use and asthma in at-risk children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;114:203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mulder B, Pouwels K, Schuiling-Veninga C, Bos H, De Vries T, Jick S, Hak E. Antibiotic use during pregnancy and asthma in preschool children: the influence of confounding. Clin Exp Allergy. 2016;46:1214–1226. doi: 10.1111/cea.12756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao D, Su H, Cheng J, Wang X, Xie M, Li K, Wen L, Yang H. Prenatal antibiotic use and risk of childhood wheeze/asthma: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2015;26:756–764. doi: 10.1111/pai.12436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bai L, Zhao D, Cheng Q, Zhang Y, Wang S, Zhang H, Xie M, He R, Su H. Trimester-specific association between antibiotics exposure during pregnancy and childhood asthma or wheeze: the role of confounding. Ann Epidemiol. 2019;30:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dom S, Droste JH, Sariachvili MA, Hagendorens MM, Oostveen E, Bridts CH, Stevens WJ, Wieringa MH, Weyler JJ. Pre- and post-natal exposure to antibiotics and the development of eczema, recurrent wheezing and atopic sensitization in children up to the age of 4 years. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40:1378–1387. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKeever TM, Lewis SA, Smith C, Hubbard R. The importance of prenatal exposures on the development of allergic disease: a birth cohort study using the West Midlands General Practice Database. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:827–832. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200202-158OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuo CH, Kuo HF, Huang CH, Yang SN, Lee MS, Hung CH. Early life exposure to antibiotics and the risk of childhood allergic diseases: an update from the perspective of the hygiene hypothesis. J Microbiol Immunol Infect Wei mian yu gan ran za zhi. 2013;46:320–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Russell SL, Gold MJ, Willing BP, Thorson L, McNagny KM, Finlay BB. Perinatal antibiotic treatment affects murine microbiota, immune responses and allergic asthma. Gut Microbes. 2013;4:158–164. doi: 10.4161/gmic.23567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abrahamsson TR, Jakobsson HE, Andersson AF, Bjorksten B, Engstrand L, Jenmalm MC. Low diversity of the gut microbiota in infants with atopic eczema. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:434–440 e431-432. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Penders J, Stobberingh EE, van den Brandt PA, Thijs C. The role of the intestinal microbiota in the development of atopic disorders. Allergy. 2007;62:1223–1236. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al Alam D, Danopoulos S, Grubbs B, Ali N, MacAogain M, Chotirmall SH, Warburton D, Gaggar A, Ambalavanan N, Lal CV. Human fetal lungs harbor a microbiome signature. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:1002–1006. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201911-2127LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Francino MP. Antibiotics and the human gut microbiome: dysbioses and accumulation of resistances. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1543. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turi KN, Gebretsadik T, Ding T, Abreo A, Stone C, Hartert TV, Wu P. Dose, timing, and spectrum of prenatal antibiotic exposure and risk of childhood asthma. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72:455–462. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oyama N, Sudo N, Sogawa H, Kubo C. Antibiotic use during infancy promotes a shift in the TH1/TH2 balance toward TH2-dominant immunity in mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:153–159. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.111142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sudo N, Yu XN, Aiba Y, Oyama N, Sonoda J, Koga Y, Kubo C. An oral introduction of intestinal bacteria prevents the development of a long-term Th2-skewed immunological memory induced by neonatal antibiotic treatment in mice. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002;32:1112–1116. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2002.01430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loewen K, Monchka B, Mahmud SM, t JongAzad GMB. Prenatal antibiotic exposure and childhood asthma: a population-based study. Eur Respir J. 2018;52:1702070. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02070-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Higgins D, Karmaus W, Jiang Y, Banerjee P, Sulaiman IM, Arshad HS. Infant wheezing and prenatal antibiotic exposure and mode of delivery: a prospective birth cohort study. J Asthma. 2021;58:770–781. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2020.1734023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu L, Pan Y, Zhu Y, Song Y, Su X, Yang L, Li M. Association between rhinovirus wheezing illness and the development of childhood asthma: a meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e013034. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Calvani M, Alessandri C, Sopo SM, Panetta V, Tripodi S, Torre A, Pingitore G, Frediani T, Volterrani A, Lazio Association of Pediatric Allergology Study G Infectious and uterus related complications during pregnancy and development of atopic and nonatopic asthma in children. Allergy. 2004;59:99–106. doi: 10.1046/j.1398-9995.2003.00338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stokholm J, Sevelsted A, Bonnelykke K, Bisgaard H. Maternal propensity for infections and risk of childhood asthma: a registry-based cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:631–637. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang C-T, Lin C-H, Lin M-C. Gestational hypertension and risk of atopic diseases in offspring, a national-wide cohort study. Front Pediatr. 2023 doi: 10.3389/fped.2023.1283782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hsu MC, Lin CH, Lin MC. Maternal gestational diabetes mellitus and risk of allergic diseases in offspring. Pediatr Neonatol. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2023.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

In this study, the data analyzed are subject to the following licenses/restrictions: To protect patients’ identity and validate the reliability of the databases, investigators are required to perform onsite analysis at HWDC via remote connection to MOHW servers. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to Dr. Ching-Heng Lin, epid@vghtc.gov.tw.