Abstract

To develop an experimental model for E7-mediated anchorage-independent growth, we studied the ability of E7-expressing NIH 3T3 subclones to enter S phase when they were cultured in suspension. We found that expression of E7 prevents the inhibition of cyclin E-associated kinase and also triggers activation of cyclin A gene expression in suspension cells. A point mutation in the amino terminus of E7 prevented E7-driven rescue of cyclin E-associated kinase activity in suspension cells; however, cells with this mutation retained some ability to activate cyclin A gene expression and promote S-phase entry. Activation of cyclin A gene expression by E7 was correlated with an increased binding of free E2F to a regulatory element in the cyclin A promoter which mediates both repression of cyclin A upon loss of adhesion and its reactivation by E7. Surprisingly, expression of E7 led to a nuclear accumulation of one species of free E2F, namely, an E2F-4–DP-1 heterodimer, that is exclusively cytoplasmic in the absence of E7. Taken together, the data reported here indicate that several different E7-dependent changes of cellular-growth-regulating pathways can cooperate to allow adhesion-independent entry into S phase.

Human papillomaviruses (HPV) of the high-risk group are etiologic agents in the pathogenesis of cervical cancer (69, 70). The capacity of HPV type 16 (HPV-16) to override growth control in mammalian cells was mapped to the E6 and E7 genes by genetic studies (23, 46). The E7 oncogene of HPV-16 can cooperate with an activated ras gene to transform rodent fibroblasts (54) and with E6 to immortalize human keratinocytes (46). Both conserved domains 1 and 2 (cd1 and cd2) in the amino-terminal part of HPV-16 E7 are required for efficient transformation of rodent cells by E7 (17, 53, 54). Similarly, mutations in the carboxy-terminal part of HPV-16 E7 (amino acids 39 to 98, referred to as domain 3 [53]) reduce the ability of E7 to transform rat embryo fibroblasts (43) and to immortalize human keratinocytes (31). It was shown that HPV-16 E7 allows resting rodent cells to initiate DNA replication (4); furthermore, it was reported that E7 can overcome several forms of G1 arrest induced by distinct antiproliferative signals: cells expressing HPV-16 E7 continue DNA replication in soft agar (4), when serum growth factors are withdrawn (65), and in the presence of DNA-damaging agents (14, 27), suggesting that E7 has the potential to facilitate progression from the G0 and G1 phases of the cell cycle into S phase.

The biochemical roles of the individual transforming domains are not well-understood. It is known that cd2 is required for the binding of E7 to members of the retinoblastoma protein family (16). This leads to activation of cellular genes driven by the E2F transcription factor (52), including the genes encoding cyclin E and cyclin A (48, 57, 65), essential proteins that are required for S-phase entry in all mammalian cells studied so far. The role of cd1 is less clear. It was reported that the integrity of cd1 is required for cell transformation but dispensable for the induction of S phase in baby rat kidney cells as measured by thymidine uptake (4); however, it was shown that a mutant protein with an amino-terminal mutation (PRO2) fails to promote S-phase entry of human keratinocytes that were G1 arrested either by treatment with transforming growth factor β or by DNA damage or contact inhibition (13), and this mutation also affects the ability of E7 to activate transcription of the cyclin A gene in serum-starved NIH 3T3 cells (65). However, the precise biochemical defect of the PRO2 mutant has not been revealed. To further analyze the ability of E7 to deregulate the control of cell cycle progression in mammalian cells, we undertook a biochemical analysis of pathways involved in the ability of E7 to promote anchorage-independent growth of NIH 3T3 cells, an experimental system that is frequently used to study the transforming potential of cellular and viral oncogenes, including HPV-16 E7 (35, 54). It was shown before that untransformed mammalian cells are arrested in G1 upon loss of cell adhesion and that G1 arrest is correlated with the failure of such cells in suspension to activate expression of the cyclin A gene (20). It was further suggested that the inhibition of G1 cyclin-dependent kinases (cdk’s) plays a key role in preventing S-phase entry of nonadherent cells (18, 58). In the experimental system used here, we found that expression of E7 prevents the inhibition of cdk2 and triggers activation of cyclin A gene expression in suspension cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and culture conditions.

Derivatives of NIH 3T3 cells expressing either wild-type HPV-16 E7 (clones E7/2 and E7/4) or the PRO2 mutant protein (clone 566/3) were obtained from K. Vousden (Frederick, Md.). NIH 3T3 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md. Cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified essential medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% calf serum, either in monolayer or in suspension on plates coated with DMEM containing 0.9% agarose, as described previously (58). The human osteosarcoma cell line U2-OS was cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Cell cycle progression was monitored by fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis with a Becton Dickinson FACScan system and cell-fit program, as described previously (65).

Preparation of protein extracts.

High-salt whole-cell extracts were prepared as previously described (30). For nuclear and cytoplasmic fractionation, cells were pelleted by centrifugation and incubated in hypotonic lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 10 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 5 μg of aprotinin per ml, 5 μg of leupeptin per ml, 5 mM NaF, 0.1 mM Na-vanadate) for 5 min on ice. After addition of Nonidet P-40 (NP-40) to a final concentration of 0.05% and incubation for 5 min on ice, nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation at 1,250 × g, washed twice with hypotonic lysis buffer containing 0.05% NP-40, and extracted in high-salt extraction buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 500 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 35% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 5 mM NaF, 0.1 mM Na-vanadate, 5 μg of aprotinin per ml, 5 μg of leupeptin per ml) by flash freezing. After the mixture was rocked for 30 min at 4°C, cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 100,000 × g. Cytoplasmic extracts were cleared by centrifugation at 10,000 × g and supplemented with glycerol to 35%.

Western blotting.

Whole-cell extracts were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and probed with polyclonal antisera to cyclin A (a gift from M. Pagano, New York, N.Y.), cyclin E (M-20; Santa Cruz Inc., Santa Cruz, Calif.), cyclin D1 (DCS-6; Neomarkers, Fremont, Calif.), pRb (14001 A; Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.), p107 (C-20; Santa Cruz Inc.), p130 (C18; Santa Cruz Inc.), and HPV-16 E7 (a gift from Joris Braspenning, Heidelberg, Germany). Samples were detected with a peroxidase-linked chemiluminescence detection system (NEN, Boston, Mass.).

Northern blotting.

Total cellular RNA was extracted by using an RNeasy preparation kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and 10 μg of total RNA was separated on 1% agarose formaldehyde gels, transferred onto nylon membranes, and probed with radioactive labelled human cDNA probes for cyclin D1 and cyclin A. For quantification, blots were analyzed by densitometric scanning and normalized to the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) signal, as described previously (65).

Reporter plasmids and expression vectors.

The cyclin A promoter-reporter gene constructs cycA-89/+11wt and cycA-89/+11mut were described previously (57). Expression vectors for human E2F-4, DP-1, and p107 were described before (66), as were expression vectors for wild-type HPV-16 E7 and the E7 mutants PRO2 and GLY24 (65).

Transfection experiments.

Cells were transfected by the calcium phosphate method as previously described (30). Twenty-four hours posttransfection, cells were trypsinized and plated in aliquots on uncoated and on agarose-coated dishes. After 20 h extracts were prepared and assayed for luciferase activity. Variations in transfection efficiency were eliminated by normalizing luciferase activity to β-galactosidase activity expressed from a cotransfected cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter-driven β-galactosidase reporter gene.

Bandshift experiments.

A double-stranded oligonucleotide encompassing the E2F binding site of the cyclin A promoter (cycA wt, 5′-GATCTTCAATAGTCGCGGGATACTT-3′) was 3′-end labelled and incubated with extracts from different cell lines, as described previously (66). E2F-associated proteins were analyzed by addition of specific antibodies to the bandshift reaction followed by incubation on ice for 50 min, prior to electrophoresis. p107 was detected by the monoclonal antibody SD15 (a gift from N. Dyson, Charlestown, S.C.), cdk2 was detected by a polyclonal antiserum (M-2; Santa Cruz Inc.), DP-1 was detected by the monoclonal antibody TFD10 (Neomarkers), E2F-4 was detected by a monoclonal antibody (WUF-11; a gift from N. Dyson), and p130 was detected by a polyclonal antiserum (C-20; Santa Cruz Inc.). To define uncomplexed E2F-DP heterodimers, 100 ng of a glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein containing the pocket domain of pRb [GST–Rb(379–928) (59)] was added to the bandshift reaction mixture, which was then incubated on ice for 50 min prior to electrophoresis. For the in vitro disruption experiments, extracts were incubated with GST fusion proteins comprising either wild-type E7 (GST-E7wt) or E7 proteins bearing single point mutations at amino acid 2 (GST-E7Pro2) or amino acid 24 (GST-E7Gly24) before electrophoresis.

Immunoprecipitation and in vitro kinase assays.

Cells were lysed by sonification in buffer containing 50 mM HEPES (pH 7), 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.1% NP-40, 1 mM NaF, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μM Na-vanadate, and 100 μg of aprotinin per ml. Lysates were precleared by incubation with 40 μl of protein A-agarose beads (Santa Cruz Inc.) for 1 h at 4°C. One microgram of purified antibody (polyclonal antisera against cyclin E [M-20], p27 [C-19], or cdk2 [M-2], all from Santa Cruz Inc.) or polyclonal serum to cyclin A (a gift from M. Pagano) was added, incubated for 1 h at 4°C, and precipitated with 30 μl of protein A-agarose beads for 1 h at 4°C. Immunopellets were washed three times with lysis buffer and either used for determination of in vitro kinase activity as described previously (65) or boiled in SDS sample buffer for SDS-PAGE. For quantification, autoradiograms were analyzed by densitometric scanning, as described previously (65).

Cyclin D1-associated kinase activity was measured as described previously (59). Briefly, GST–Rb(379–792) was expressed in bacteria and purified with glutathione-Sepharose. Cells were lysed in a buffer containing 0.1% Tween 20 (41), and cyclin D1-associated kinase was precipitated by using a monoclonal antibody to cyclin D1 (a gift from J. Bartek, Copenhagen, Denmark). The pellet was washed four times in lysis buffer and two times in 50 mM HEPES–1 mM DTT and resuspended in kinase buffer containing 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 10 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM MnCl2, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.1 mg of leupeptine per ml, 0.5 mM DTT, 10 μM ATP, 0.1 mM sodium vanadate, and 1 mM NaF. The immunoprecipitate was incubated in kinase buffer in the presence of 0.02 mg of GST–Rb(379–792) per ml and 1 mCi of [γ-32P]ATP per ml for 30 min at 30°C. The reaction mixture was separated by SDS-PAGE, and phosphorylated GST-Rb was detected by autoradiography.

Immunofluorescence analysis.

Transfected U2-OS cells were grown on coverslips for 12 h, fixed in ice-cold methanol-acetone (1:1) for 10 min, and treated with 0.1% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline for 5 min. Undiluted supernatant of hybridoma cells (monoclonal antibody WUF-11; a gift from N. Dyson) was supplemented with bovine serum albumin to 1% and Triton X-100 to 0.1%, and coverslips were incubated with antibody solution in a wet chamber for 2 h at 37°C. After being washed, coverslips were incubated with a Cy3-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, Pa.) for 1 h at 37°C and mounted in 90% glycerol. Counterstaining of nuclei was obtained by addition of 1 μg of DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) per ml to the secondary antibody solution.

Yeast two-hybrid experiments.

Two-hybrid interaction assays were performed as described in reference 67. Briefly, Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells (EGY48/pSH1834) containing a LexA-driven lacZ reporter gene (lexA8o-Gal1-lacZ) were transformed with the plasmids pLexA-E7wt::HIS3 and pLexA-E7Pro2::HIS3, along with pB42-p27::TRP1, as indicated in Fig. 2D. After a 15-h induction of the pB42-p27 hybrid gene, yeast cell extracts were prepared and β-galactosidase activity was determined as described in reference 67. Values are means of results from four independent experiments.

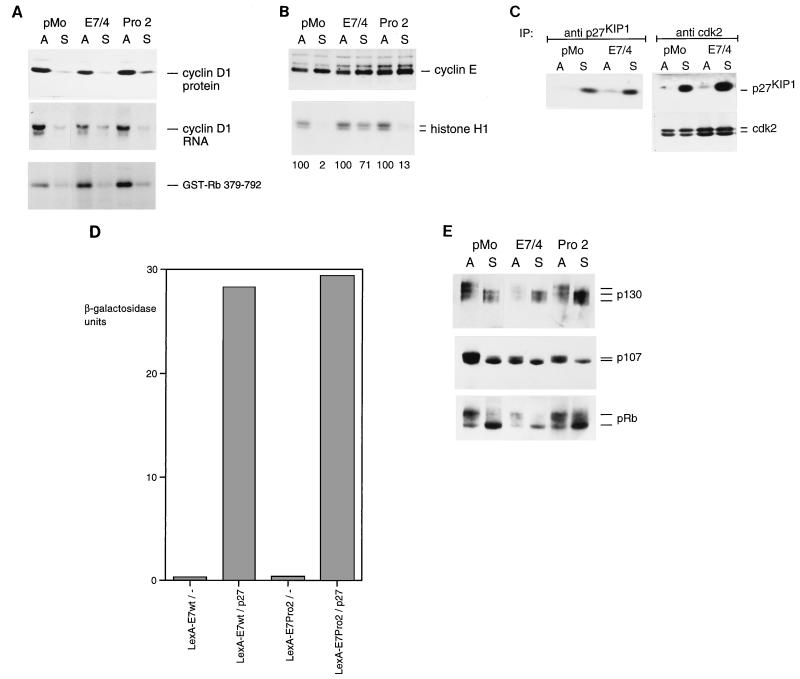

FIG. 2.

Effects of E7 on expression of cyclin genes and cdk. HPV-16 E7-expressing and control cells were treated as described in the legend to Fig. 1A. (A) Analysis of cyclin D1 expression by immunoblotting with a cyclin D1-specific monoclonal antibody (upper blot) and by Northern blotting of cellular RNA (middle blot) and cyclin D1-associated kinase activity (lower blot). (B) Expression levels of cyclin E were determined by immunoblotting (upper blot). Activity of cyclin E-associated kinase was assayed by immunoprecipitation with a cyclin E-specific polyclonal antiserum and a subsequent kinase assay by using histone H1 as a substrate. Relative activities (in percentages) of histone H1 kinase are indicated. (C) Levels of p27KIP1 in adherent and suspension cells were monitored by immunoprecipitation with a p27KIP1-specific antiserum followed by immunoblotting of the precipitates with antibodies to p27 (left part). P27KIP1 associated with complexes containing cdk2 was analyzed by immunoprecipitation of cdk2 followed by immunoblotting of the precipitates with antibodies to p27KIP1 and cdk2, as indicated. IP, immunoprecipitate. (D) Interaction of E7 mutants with p27KIP1 in yeast. A yeast two-hybrid assay was performed as described previously (67). Bars indicate β-galactosidase activity. The values are means of results from four independent experiments. wt, wild type. (E) Expression and phosphorylation of different pocket proteins in E7-expressing and control cells. Cellular proteins were separated by high-resolution SDS-electrophoresis, immunoblotted, and probed with antibodies to p130, p107, and pRb, as indicated. Bands representing the hypo- and hyperphosphorylated forms of these proteins are marked.

RESULTS

Anchorage-independent S-phase entry of E7-expressing cells.

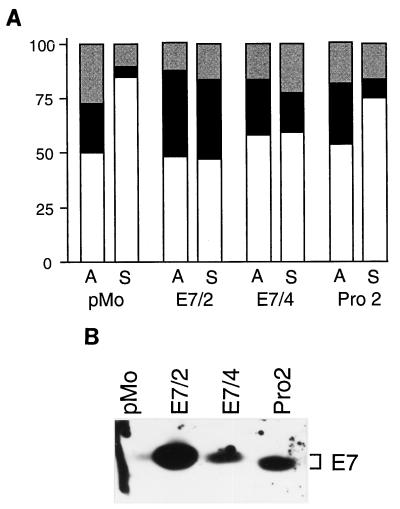

To develop an experimental model for E7-mediated anchorage-independent growth, we studied the ability of E7-expressing NIH 3T3 subclones to enter S phase when they were cultured in suspension on agarose-coated dishes, an experimental condition known to arrest untransformed cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle (20, 58) (Fig. 1A). Two independent lines in which the HPV-16 E7 oncogene was expressed from a stably transfected expression plasmid (10) were chosen for this experiment: E7/4 cells expressing moderate levels of HPV-16 E7 and E7/2 cells expressing very high levels of HPV-16 E7 (see below and Fig. 1B). The E7 protein levels were not affected by loss of adhesion (data not shown). In control NIH 3T3 cells transfected with the empty expression vector pMo, the proportion of S-phase cells decreased from 23% ± 2% to 4% ± 2% upon loss of adhesion, as was reported before the parental NIH 3T3 cell line (58). When grown under regular culture conditions, E7/4 cells displayed a cell cycle profile similar to that of pMo cells, with roughly 26% ± 5% of the cells being in S phase. Unlike the control cells, E7/4 cultures retained a significant amount of cells in S phase when they were grown in suspension, reflecting the ability of E7 to promote anchorage-independent growth. In cultures of E7/2 cells, a significantly higher proportion of cells, i.e., 35% ± 5%, were in S phase; as in E7/4 cells, the amount of S-phase cells was only slightly decreased in suspension culture. These observations demonstrate the capacity of E7-expressing cells to proliferate in the absence of adhesion to a substratum, as reported previously (17, 34, 54).

FIG. 1.

E7-expressing cells enter S phase in suspension culture. (A) Fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis. Exponentially growing cultures of NIH 3T3 cells that were either transfected with the empty vector (pMo) or expressed wild-type HPV-16 E7 (clones E7/2 and E7/4) or the PRO2 mutant protein were trypsinized and seeded in aliquots on uncoated dishes (bars A) or dishes that were coated with agarose to prevent attachment (bars S) and incubated for 20 h under these conditions. Percentages of cells in G1 (open bars), S (filled bars), and G2/M (shaded bars) are shown. (B) Detection of HPV-16 E7 protein. Extracts were prepared from asynchronously growing cells, as indicated, and analyzed by immunoblotting with a polyclonal serum to HPV-16 E7.

It was shown before that the ability of E7 to promote growth in the absence of serum growth factors is not only dependent on the integrity of the pRb binding domain but also requires cd1 (65). Similarly, it was shown that both cd1 and cd2 are required for E7-dependent S-phase entry of human keratinocytes treated with transforming growth factor β or DNA-damaging agents (13). To investigate if the N-terminal part of E7 is also required for anchorage-independent growth, we studied the ability of NIH 3T3 cells expressing E7 with an amino-terminal mutation (PRO2) to grow in suspension culture. The expression level of the mutant E7 protein observed in the PRO2 cell line was slightly higher than the expression level of the E7 protein observed in the E7/4 cell line (Fig. 1B). When PRO2 cells were grown on regular dishes, their cell cycle profile was very similar to the profiles obtained with either pMo or E7/4 cells. In suspension culture, these cells reproducibly retained about 8% ± 2% of their cells in S phase (compared to 4% S-phase cells in suspension cultures of control cells), indicating that the mutated E7 protein retains some ability to stimulate anchorage-independent growth. However, by comparison with the cell cycle profile of nonadherent E7/4 cells (18% ± 2% S-phase cells in suspension), it appears that mutation of cd1 leads to a reduction in the ability of E7 to stimulate S-phase entry, given the fact that E7 expression levels are similar in both cell lines (Fig. 1A). These observations are consistent with a role for cd1 in induction of anchorage-independent growth by E7.

Constitutive cyclin E-cdk2 kinase activity in E7-expressing cells.

In untransformed rodent fibroblasts, expression of the cyclin D1 gene is downregulated at both the mRNA and the protein level upon loss of adhesion (6, 68). Since cyclin D1 and its associated kinase activity are required for S-phase entry in normal rodent fibroblasts (3, 39) and ectopic expression of cyclin D1 can facilitate S-phase entry of suspended cells (58), it appears possible that the observed ability of E7-expressing cells to enter S phase in suspension may be due to an upregulation of cyclin D1 gene expression in E7-expressing cells. However, when we measured expression of the cyclin D1 gene in the NIH 3T3-derived cell lines, we found that cyclin D1 protein and mRNA levels were consistently downregulated in all nonadherent cell cultures, irrespective of expression of the E7 gene. Furthermore, we found that cyclin D1-associated kinase is not increased by E7 (Fig. 2A). This finding indicates that cyclin D1 and its associated kinase are not involved in the ability of E7 to promote anchorage-independent cell cycle progression. These observations are consistent with the observation that cyclin D1 is not required for S-phase entry of cells expressing pRb-inactivating viral oncogenes, e.g., HPV-16 E7 (38).

In untransformed cells, the kinase activity associated with cyclin E is drastically downregulated upon loss of adhesion (18, 58). Since cyclin E and its associated kinase cdk2 are essential for S-phase entry in all mammalian cells studied so far, including HPV-positive carcinoma cells (49, 51), our finding that E7-expressing cells can enter S phase in the absence of cell adhesion prompted us to investigate the level of cyclin E-associated kinase in these cells. The levels of cyclin E protein were not significantly affected by loss of adhesion in the experimental cell lines used here (Fig. 2B, upper blot). Also, no significant changes in cyclin E mRNA levels were observed (data not shown). When cyclin E was precipitated from cellular extracts and precipitates were assayed for histone H1 kinase activity, we found that although cyclin E-associated kinase was strongly downregulated in control cells upon loss of adhesion, the level of cyclin E-associated kinase was only marginally affected by the culture conditions in both E7/4 (reduction to 71%) (Fig. 2B) and E7/2 (data not shown) cells. It was shown before that the repression of cyclin E-associated kinase in nonadherent NIH 3T3 cells is caused by a stabilization of the p27 protein (58), and we asked if p27 levels would also increase in E7-expressing cells grown in suspension. p27 was precipitated from E7-expressing and control cells, either grown on uncoated dishes or kept in suspension culture for 20 h, and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed for p27 by Western blotting. As expected from our previous study (58), loss of adhesion led to a strong increase of p27 protein in control pMo cells (Fig. 2C, left blot), probably accounting for the inhibition of kinase activity. However, a similar increase of p27 was observed in E7/4 cells, and by immunoblotting with antibodies to cdk2, we observed that equal amounts of p27 are associated with cdk2 in both pMo and E7/4 cells (Fig. 2C, right blot). These results suggest that the increased kinase activity associated with cyclin E-cdk2 complexes in E7-expressing cells is not due to a quantitative sequestration of p27 from these complexes, at least within the detection limits of the assays used here (see Discussion). The PRO2 mutant protein binds to p27 in a yeast two-hybrid system with an affinity equal to that of the wild-type E7 (Fig. 2D). However, it failed to promote significant cyclin E-associated kinase activity in suspension cells (Fig. 2B), indicating that the N terminus of E7 is required for the induction of kinase activity associated with cyclin E-cdk2 complexes.

So far, the members of the pRb family are the best-studied targets for G1-specific cdk’s. To analyze the influence of E7 on the phosphorylation of these potential cdk substrates, we studied the phosphorylation statuses of proteins of the pRb family in these cells by Western blotting (Fig. 2E). We observed a significant reduction of the overall abundance of pRb in E7/4 cells, as compared to levels in control cells. This may reflect proteolytic degradation of pRb, which was shown to be increased by E7 (7). However, the majority of the pRb molecules found in E7-expressing cells were predominantly in the hypophosphorylated form. Similarly, we found that the hypophosphorylated form of p107 was the major p107 species found in all cells from suspension culture, irrespective of the level of E7 expression. Similar results were obtained with p130: upon loss of adhesion in control cells, we observed the accumulation of a faster-migrating p130 species, which probably represents hypophosphorylated p130 (42). This alteration was also observed in E7-expressing cells upon loss of adhesion, indicating that the phosphorylation of p130 is not detectably altered by E7. In summary, these data indicate that the failure of E7 to increase the abundance of cyclin D1, and hence its associated kinase, correlates with a lack of detectable phosphorylation of pocket proteins, in agreement with previous findings that cyclin E-associated kinase is not sufficient for quantitative phosphorylation of pRb family members (for a review, see reference 5).

E7 prevents E2F-dependent downregulation of cyclin A gene expression in nonadherent NIH 3T3 cells.

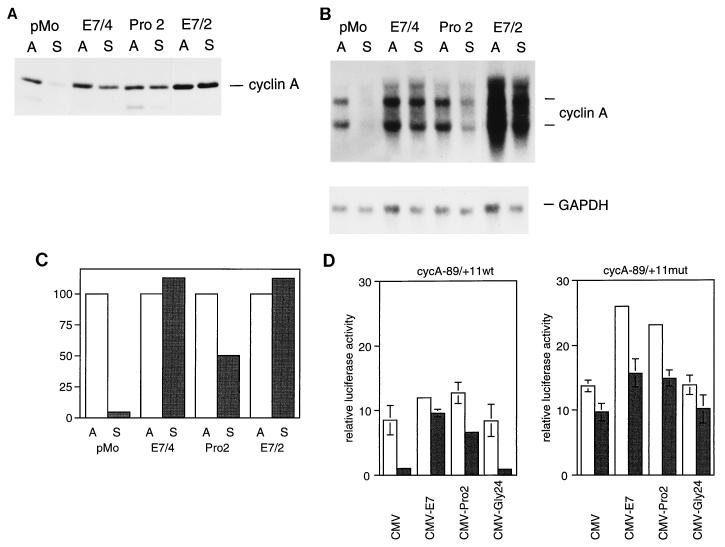

Since it was shown before that ectopic expression of cyclin A is sufficient to allow S-phase entry of nonadherent rodent fibroblasts (20), we analyzed the influence of E7 on the expression of the cyclin A gene in suspension cells. In Western blot experiments, we found that expression of the cyclin A gene, while being strongly downregulated upon loss of cell adhesion in control cells, was only marginally reduced in cells expressing wild-type E7 (Fig. 3A). When RNA was prepared from parallel samples and analyzed by Northern blotting, we found that the cyclin A mRNA levels, while being reduced to 5% ± 2% upon loss of cell adhesion in control cells, were not reduced in cells expressing wild-type E7 (Fig. 3B and C). In cells expressing the PRO2 mutant protein, we reproducibly observed a significant reduction, to 50% ± 5% of the control level, of cyclin A mRNA levels upon loss of adhesion, indicating that cd1 contributes to maximal expression of the cyclin A gene. In contrast to the results obtained for the cyclin A mRNA levels, the cyclin A protein levels were virtually indistinguishable between E7/4 cells and PRO2 cells (Fig. 3A). This discrepancy, which may reflect differences in the levels of stability of cyclin A in both cell lines, was not further investigated.

FIG. 3.

Constitutive expression of the cyclin A gene in HPV-16 E7-expressing cells. (A) Western blot showing cyclin A protein levels in E7-expressing and control cells under normal growth conditions (lanes A) and after 20 h of culture in suspension (lanes S). (B) Northern blot analysis of RNA prepared in parallel and probed with a labelled fragment of the murine cDNAs for cyclin A (upper blot) and GAPDH (lower blot). (C) Cyclin A mRNA levels were quantitated and normalized relative to the GAPDH signal. Relative levels of expression (in percentages) are given by the bars. (D) Analysis of cyclin A promoter activity. NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with luciferase reporter gene constructs containing the promoter region of the human cyclin A gene. Twenty-four hours posttransfection cultures were trypsinized and plated in aliquots on uncoated (open bars) and agarose-coated (shaded bars) dishes for 20 h. The left part shows the relative luciferase activity of the construct containing the wild-type promoter (cycA-89/+11), whereas the right part shows the activity of a construct in which the E2F binding site was altered by clustered point mutations (cycA-89/+11mut). The values are the means of results of four independent experiments and are normalized to the activity of a cotransfected CMV-based β-galactosidase expression vector.

To analyze if the observed effects of E7 on cyclin A mRNA levels are due to increased transcription of the cyclin A gene in E7-expressing cells, we investigated the ability of E7 to activate transcription of a cyclin A reporter gene in nonadherent cells by cotransfection experiments. Wild-type HPV-16 E7 was expressed in NIH 3T3 cells by a transient-transfection protocol; transfected cultures were divided, and aliquots were seeded on uncoated dishes and agarose-coated dishes and kept under these conditions for 20 h. In this experiment, we observed a strong reduction in the activity of a reporter gene driven by the human cyclin A gene promoter. Upon coexpression of wild-type E7, loss of adhesion failed to inhibit cyclin A promoter activity, indicating that the inhibitory signal is neutralized by E7 (Fig. 3D). These data confirm our conclusion that the constitutive expression of the cyclin A gene in the E7-expressing experimental cell lines (Fig. 3B) is due to expression of the viral oncoprotein. To determine the regulatory elements in the cyclin A gene that are required for the ability of E7 to promote anchorage-independent transcription of the cyclin A gene, we made use of cyclin A reporter gene constructs with defined mutations in known cis regulatory elements. A variant E2F binding site which mediates both cell cycle regulation of the cyclin A gene and its downregulation in response to various antiproliferative signals, such as growth factor withdrawal (65) and DNA damage (59), had been identified in the cyclin A promoter (57). When a reporter gene construct carrying a gene with a point mutation in the E2F binding site was used in the cotransfection assay, we found that promoter activity was strongly enhanced in suspension cells, consistent with our previous observation that the E2F binding site of the cyclin A promoter serves as a silencer element when it is assayed in suspension cells (58). Thus, the 10-fold activation observed with wild-type E7 in nonadherent cells results mainly from relief of transcriptional repression (Fig. 3D, left part). Similar to the results obtained in stably transfected cell lines, the protein with the amino-terminal mutation, PRO2, retained the ability to relieve repression of the cyclin A promoter in nonadherent cells, although the efficiency of transactivation was reduced by roughly 30%, with respect to that of wild-type E7. Coexpression of a mutant E7 protein, GLY24, which carries a mutation in cd2, did not relieve transcriptional repression. Since GLY24 differs from the wild-type protein by its inability to target proteins of the pRb family (4, 17), these data suggest that activation of cyclin A gene expression by E7 involves interaction with proteins of the pRb family, which are well-established as repressors of E2F-dependent transcription (36).

Free E2F binds to the cyclin A promoter in E7-expressing cells.

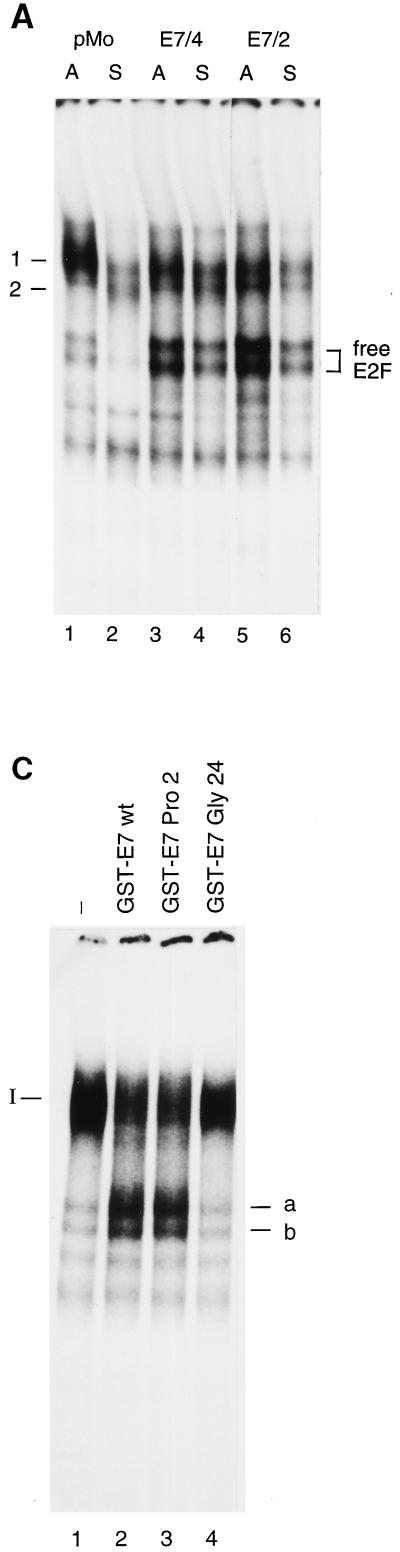

Previous reports suggest that E7 can sequester members of the pRb protein family from E2F-DP heterodimers (1, 9, 50, 63, 64). It was shown before that transcription of the cyclin A gene is under negative control by specific members of the retinoblastoma gene family, in particular by p107 and to some extent by p130 (57, 66). To investigate if the ability of E7 to allow transcription of the cyclin A gene in nonadherent cells might be related to its action on E2F complexes binding to the cyclin A promoter, extracts from E7-expressing and control cells were analyzed for proteins interacting with the E2F binding site of the human cyclin A promoter in bandshift experiments.

In high-salt whole-cell extracts of adherent control cells, we detected one major complex (referred to as complex 1) (Fig. 4A), which contains p107 and cdk2, as shown by its reaction with antibodies specific for these proteins (Fig. 4B). Upon loss of adhesion, complex 1 is replaced by two faster-migrating complexes (referred to as complex 2) (Fig. 4A) that contain E2F in association with p107 but that are devoid of cdk2 (Fig. 4B). In addition to the p107-containing complexes, in adherent control cells we observed two faster-migrating bands which represent free E2F, as suggested by their mobilities in the gel and the ability to associate with a recombinant GST fusion protein containing the pocket domain of pRb (data not shown; see below). The abundance of free E2F was significantly reduced when control cells were plated in suspension culture (Fig. 4A). In extracts prepared from E7-expressing cell lines, high levels of free E2F were consistently detectable and the level of free E2F was only slightly reduced in E7-expressing cells upon loss of adhesion (Fig. 4). When we analyzed the association of E2F with p107 in extracts from E7-expressing cells, we found that some p107 remains bound to E2F complexes in extracts from E7/4 cells but that only a very small proportion of E2F is associated with p107 in extracts from E7/2 cells, probably reflecting the higher level of expression of the E7 oncoprotein in this subclone (Fig. 1B). The PRO2 mutant of E7 disrupts higher-order E2F complexes as efficiently as the wild-type protein, as shown by in vitro studies using recombinant GST-E7 (Fig. 4C). In contrast, the GLY24 mutant which does not bind to pocket proteins lacks the ability to disrupt the higher-order complexes.

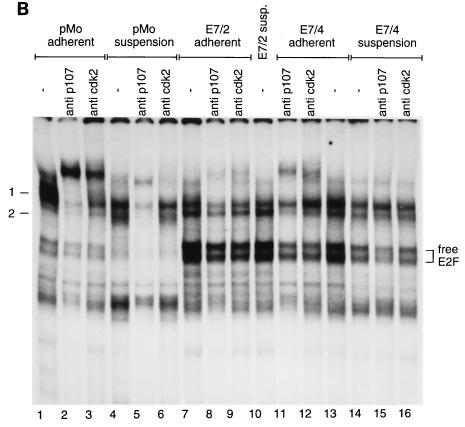

FIG. 4.

E7-expressing cells retain free E2F in suspension. (A) Bandshift analysis of whole-cell extracts from E7-expressing (E7/4 and E7/2) and control (pMo) cells after 20 h of culture under normal (lanes A) or suspension (lanes S) conditions with an oligonucleotide encompassing the E2F binding site of the human cyclin A promoter as the radioactive probe. The positions of specific complexes are marked. (B) Complexes obtained with whole-cell extracts as described for panel A were analyzed by addition of specific antibodies to p107 (lanes 2, 5, 9, 11, and 15) and cdk2 (lanes 3, 6, 9, 12, and 16). The positions of complexes 1 and 2 and of bands representing free E2F are marked. susp., suspension. (C) Bandshift analysis of nuclear extracts from asynchronously growing NIH 3T3 cells with an oligonucleotide encompassing the E2F binding site of the human cyclin A promoter as the radioactive probe. Prior to electrophoresis, extracts either remained untreated (lane 1) or were incubated with the recombinant GST-E7 wild type (wt) (lane 2), GST-E7 PRO2 (lane 3), and GST-E7 GLY24 (lane 4).

Free E2F is retained in the nuclei of E7-expressing but not control cells.

It was shown previously that certain E2F-DP heterodimers fail to accumulate in the nucleus, unless they are complexed with a pRb family member which serves as a nucleus-targeting subunit (12, 37, 40). This observation prompted us to determine the subcellular localizations of the various E2F species shown in Fig. 4. To address this question, E7-expressing and control cells were subjected to mild lysis and then nuclei were separated from the cytoplasmic fractions. We decided to use E7/2 cells rather than E7/4 cells for these experiments, since a residual association of E2F complexes with p107, as observed in E7/4 cells (Fig. 4B), might obscure the result. Proper fractionation of the extracts was monitored by two marker proteins that are known to be predominantly nuclear or cytoplasmic. As shown in Fig. 5A, the vast majority of Sp1, a nuclear transcription factor (21), was retained in the nuclear fractions whereas Sp1 was undetectable in the cytoplasmic fractions. When we monitored the distribution of M2 pyruvate kinase, a prototypical cytosolic enzyme (60), we found that during the fractionation procedure this protein was restricted to the cytoplasmic fraction in both cell types. Together, these results suggest that the fractionation procedure yielded a quantitative separation of nuclear from cytoplasmic proteins, with little cross-contamination between the fractions.

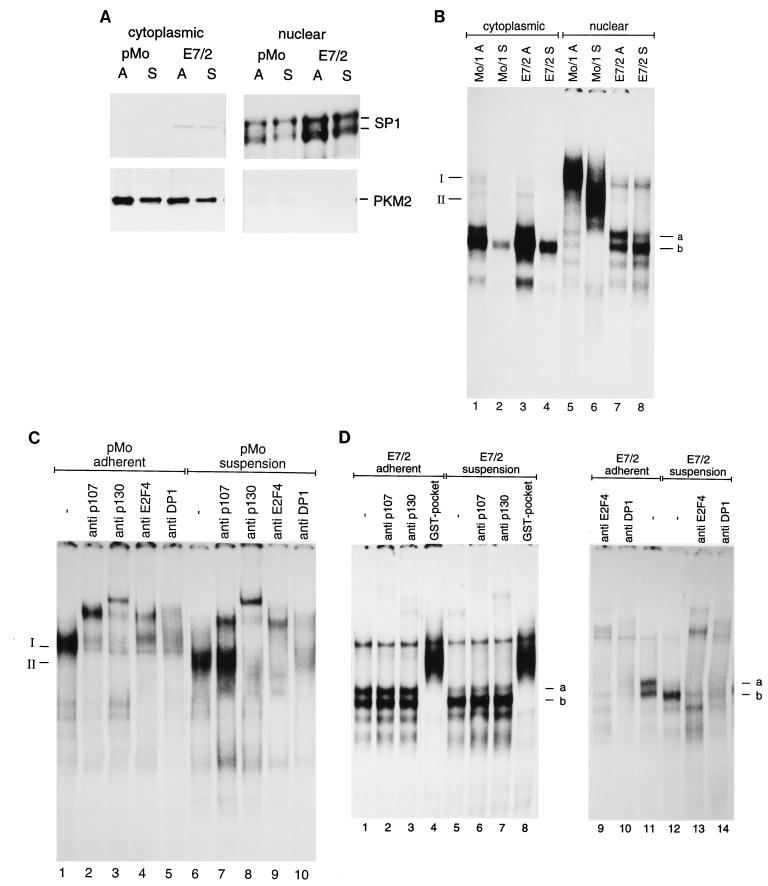

FIG. 5.

Free E2F is nuclear in E7-expressing but not in control cells. Nuclear extracts prepared from E7-expressing (E7/2) and control (pMo) cells after 20 h of culture under normal (lanes A) or suspension (lanes S) conditions were analyzed for complexes binding to the E2F site of the cyclin A promoter by bandshift experiments. (A) Western blot controlling the separation of cytoplasmic (left part) and nuclear (right part) compartments in the fractionation procedure. As markers for the nuclear fractions, antibodies to SP1 were used. Purity of the cytoplasmic fraction was controlled by a antibodies to M2 pyruvate kinase (PKM2). (B) Bandshift experiment with the cytoplasmic fractions and nuclear extracts shown in panel A with an oligonucleotide encompassing the E2F site of the human cyclin A promoter as the labelled probe. Positions of specific complexes are marked. (C) Analysis of complexes obtained with nuclear extracts of control cells (pMo) by addition of antibodies specific for p107 (lanes 2 and 7), p130 (lanes 3 and 8), E2F-4 (lanes 4 and 9), and DP-1 (lanes 5 and 10). The positions of complexes I and II are marked. (D) Analysis of complexes obtained with E7/2 cells by addition of antibodies specific for p107 (lanes 2 and 6), p130 (lanes 3 and 7), E2F-4 (lanes 9 and 13), and DP-1 (lanes 10 and 14). Free E2F was detected by its ability to bind to a recombinant GST fusion protein containing the pocket domain of pRb [GST–Rb(379–928)], which resulted in a retarded band (lanes 4 and 8).

We then analyzed the status of E2F complexes by bandshift experiments, using the cyclin A promoter-derived E2F site as the probe. The predominant E2F species found in cytoplasmic fractions comigrated with free E2F, in keeping with the observation that free E2F-4–DP-1 heterodimers fail to localize to the nucleus in the absence of pRb family members. Interestingly, we found that cytoplasmic free E2F was more abundant in cells growing asynchronously than in cells growing in suspension culture. In nuclear extracts, a different pattern was observed: mainly higher-order E2F complexes were observed in nuclear extracts of control cells (Fig. 5B). Analysis of these complexes by antibody supershift experiments revealed that E2F-4 and DP-1, two specific members of the E2F and DP families of proteins, are major components of the majority of the complexes binding to the cyclin A promoter in NIH 3T3 cells. The main complex present in nuclear extracts from adherent control cells, referred to as complex I, was quantitatively supershifted with the p107-specific monoclonal antibody SD15 (Fig. 5C). Whereas this complex was also supershifted by a polyclonal antiserum to p130, the p130 antiserum used here cross-reacts with p107 (66). These observations indicate that complex I contains p107 but not p130. In nonadherent control cells, complex I was replaced by a faster-migrating complex, referred to as complex II (Fig. 5B). Complex II was also supershifted by the polyclonal anti-p130 antiserum, whereas only part of this complex was supershifted by the SD15 antibody (Fig. 5C). Thus, we conclude that p107 is the preferential binding partner of E2F complexes in adherent pMo cells and that both p107 and p130 are present in nuclear E2F complexes prepared from nonadherent control cells.

The predominant E2F species in nuclear extracts of E7-expressing cells comigrated with free E2F. Complexes designated a and b (Fig. 5D) did not react with antibodies to p107 or p130 and could be shifted into higher-order complexes by addition of a GST-pocket protein fusion (Fig. 5D). As was initially shown by Dynlacht et al. (15), this observation indicates that the recombinant GST-pocket protein has bound to free E2F to produce a higher-order complex (59). While the abundance of complex a was significantly reduced in nuclear extracts from nonadherent E7/2 cells, complex b was not affected by loss of adhesion. We also analyzed the presence of different known E2F and DP family members in these complexes and found that both complexes a and b are recognized by antibodies to E2F-4 and DP-1 (Fig. 5D), while antibodies to E2F-5, the other known p107-associated member of the E2F protein family (8, 28), or antibodies to E2F-1 (24) did not affect the bandshift pattern (data not shown). These results indicate that free E2F-4–DP-1 heterodimers are present in whole-cell extracts from both control cells and E7-expressing cells (Fig. 4A) but that free E2F is retained in the nuclei of E7-expressing cells only. Three different antibodies to HPV-16 E7 failed to recognize bands a and b, indicating that E7 is not part of these complexes (data not shown).

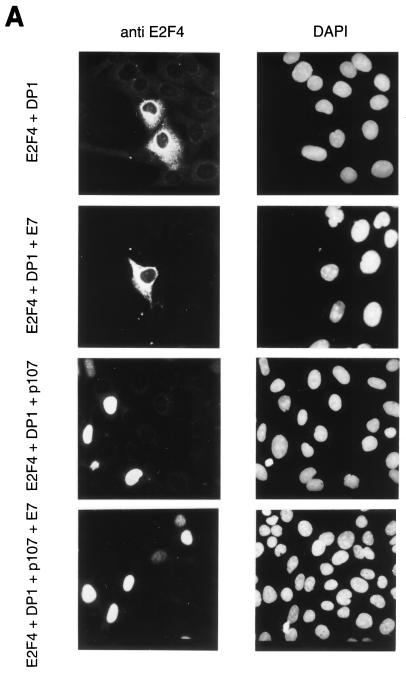

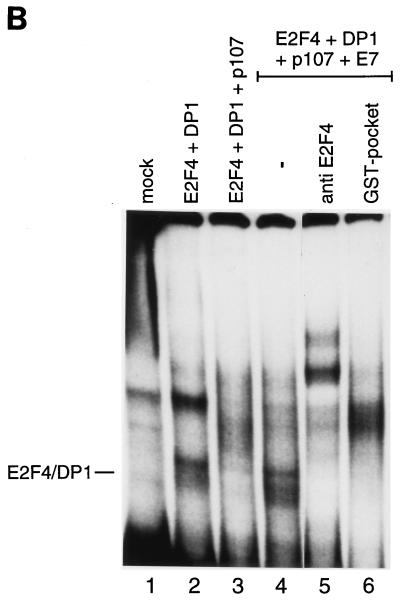

To address the influence of E7 on the compositions and subcellular localizations of E2F complexes in a transient-transfection assay, U2-OS cells were transfected by expression vectors for E2F-4 and DP-1 and then E2F-4 localization was analyzed by immunofluorescence staining. As described previously by others (12, 40), ectopic expression of E2F-4 and DP-1 resulted in the accumulation of E2F in the cytoplasm, as is shown by E2F-4 immunostaining in Fig. 6A. Upon coexpression of p107, E2F-4 was quantitatively relocalized to the nucleus. When E7 was coexpressed, E2F-4 remained entirely nuclear, as is shown by the nuclear signal in Fig. 6A. Analysis of transfected cell extracts by bandshift experiments clearly demonstrated that expression of E7 induces a quantitative disruption of E2F-4–DP-1–p107 complexes in these cells (Fig. 6B). When we coexpressed E2F-4 and DP-1 with E7 in the absence of p107, we found that E2F-4–DP-1 heterodimers remained cytoplasmic (Fig. 6A), indicating that nuclear localization is dependent on p107, but that E7 induces both disruption of p107-E2F complexes and the persistence of free E2F in the nucleus.

FIG. 6.

Nuclear localization of E2F-4 after transient expression of HPV-16 E7. U2-OS cells were transfected with expression vectors for E2F-4, DP-1, p107, and HPV-16 E7, as indicated. (A) Immunofluorescence staining of transfected cells with a monoclonal antibody against E2F-4 (left side). Seven to 10% of cells show a bright staining, indicating expression of the transfected protein. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (right side). (B) Whole-cell extracts prepared from transfected U2-OS cells were analyzed by bandshift experiments with the E2F binding site of the human cyclin A promoter as the labelled probe. The complex formed after transfection of expression vectors for E2F-4 and DP-1 (free E2F; lane 2) is marked. This complex is absent in extracts from cells transfected with expression vectors carrying genes encoding E2F-4, DP-1, and p107 but reappears when an expression vector for HPV-16 E7 is included. The complex obtained after coexpression of E7 (lane 4) was analyzed by addition of antibodies to E2F-4 (lane 5) and addition of recombinant GST fusion protein containing the pocket domain of pRb [GST–Rb(379–928); lane 6], which resulted in a retarded band.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to identify cellular pathways by which the E7 gene of HPV-16 enables rodent fibroblasts to enter S phase in suspension. It was shown previously that loss of adhesion results in repression of G1-type cdk’s indicating that the ability of E7 to promote anchorage-independent growth may rely on the modulation of cell cycle regulatory pathways by the viral oncoprotein. Expression of the cyclin D1 gene, which is downregulated by loss of adhesion in untransformed cells (reviewed in reference 2) was not affected by E7 in our experimental system; similarly, the expression level of cyclin E was not significantly affected by E7. Two major differences were found between E7-expressing and control cells grown in suspension. First, we observed that in E7-expressing cells the activity of cyclin E-associated kinase was not downregulated by loss of adhesion; second, expression of the cyclin A gene occurred independently of cell adhesion in E7-expressing cells. The latter effect may well be involved in the ability of E7-expressing cells to enter S phase in suspension, as it was shown that ectopic expression of cyclin A allows S-phase entry of untransformed rodent fibroblasts (20).

Constitutive activation of cyclin E-associated kinase in E7-expressing cells.

To investigate the way by which E7 prevents downregulation of cyclin E-associated kinase in nonadherent cells, we analyzed the expression of genes encoding cdk inhibitors. While expression of p16INK4A was undetectable in these cells, we found a low level of expression of p21WAF-1/CIP1 in both E7-expressing and control cells. p21 gene expression was not affected by loss of adhesion (data not shown), a result similar to our previous results (58). In contrast, we observed a strong accumulation of p27 upon loss of adhesion, in both control cells and E7-expressing cells. There were also similar increases in the association of p27 with cdk2 in both cell types, suggesting that in E7-expressing cells cyclin E-dependent kinase may be resistant to inhibition by p27. We found that a mutation in the N-terminal part of E7, which strongly reduces its transforming potential (17), renders the protein unable to prevent downregulation of cyclin E-associated kinase in suspension cells, indicating that the ability of E7 to activate cyclin E-dependent kinase may play a role in cell transformation. Since the E7 wild type and the PRO2 mutant bind p27 with similar affinities in a yeast two-hybrid experiment (Fig. 2D), the available data suggest that E7 binds p27 via its C terminus and that sequences in the N terminus (or the overall structure of the E7 molecule) are required for inactivation. However, more work is required to test that model.

Recently, several other groups analyzed the influence of E7 on cyclin E-associated kinase in cells expressing p21WAF-1/CIP1, another cdk inhibitor with homology to p27. Hickman et al. (26) and Ruesch and Laimins (56) reported that expression of E7 does prevent to some extent the downregulation of cdk2 activity in the presence of p21. Interestingly, Hickman et al. found that the subpopulation of cdk2 that remains active in p21-expressing cells can be coprecipitated by antibodies to E7 (26), raising the possibility that a subset of the cellular cdk2 activity is resistant to the inhibitory action of p21, probably as a result of cdk2 binding to E7 (44, 61). More recently, two groups have shown that E7 can bind and inactivate p21 (19, 32); according to these authors, the ability of E7 to interact with p21 requires sequences in the Rb binding domain (32) and the C-terminal part of the molecule (19). By analogy, our finding that cdk2 remains active in E7-expressing suspension cells may be related to our previous observation that E7 can bind to p27 and abrogate its ability to inactivate cyclin E-cdk2 complexes in vitro (67). However, we cannot formally exclude the possibilities that the kinase activity we observed in the experiment shown in Fig. 3 is associated with a minor subfraction of cyclin E-cdk2 complexes and that E7 may indeed induce subtle changes in the compositions of these complexes which we failed to detect by the assays shown in Fig. 3. In contrast to the results reported in references 26 and 56, two other groups, using slightly different experimental systems, reported that treatment of E7-expressing human fibroblasts with actinomycin D leads to a strong induction of p21 gene expression and a subsequent quantitative inhibition of cdk2 (33, 45). While the reasons for this discrepancy are not clear at present, it appears possible that the expression levels of p21 and/or E7 may determine the outcome of the actual experiment. While p21 and p27 show structural and functional similarity, the functions of both proteins are not identical; for example, p21 but not p27 was shown to interact with PCNA, a cellular protein that is involved in the control of DNA replication; furthermore, the abundance of both proteins is regulated through entirely different pathways. Thus, it appears possible that E7 may affect in different ways the functions of p27 and p21.

Transcription of the cyclin A gene is rendered anchorage independent by E7.

Expression of the cyclin A gene, which encodes a key regulator of S-phase entry, is regulated at various levels. Thus, it had been shown that the rate of transcription (25), stability of the mRNA (29), stability of the protein (59), and activity of the associated kinase (55) are all subject to regulation in various instances. It is conceivable that E7 may influence several of these steps. For example, we found that cyclin A-associated kinase was strongly reduced in control NIH 3T3 cells but not significantly affected in E7-expressing cells (56a). In the present study, we focused on transcriptional regulation of the cyclin A gene, since this step is of critical importance for the proper function of the gene. The ability of E7 to activate cyclin A gene expression in suspension cells correlates with an increased activity of the cyclin A promoter under these conditions, and we found that the E7-dependent increase in promoter activity is mediated through an E2F binding site. As was reported previously for serum-starved cells (65), sequences distinct from that of the E2F site may also contribute to promoter activation in suspension cells. However, the data shown in Fig. 3D clearly demonstrate that the E2F site is a bona fide target for E7. Results of DNA binding studies and transient-transfection experiments allow some detailed conclusions concerning the mechanism by which the transcription of the cyclin A gene is modulated by E7. In the untransformed control NIH 3T3 cells, only higher-order E2F complexes were found in nuclear extracts. In adherent cells, E2F complexes contain p107 and cdk2, and in previous studies, such complexes were described for cells in which the cyclin A promoter is active (66). Upon loss of adhesion, this complex is replaced by two new complexes, one containing p130 and the other one containing p107 (Fig. 5) but neither of them containing cdk2 (56a). While the exact role of these complexes is not entirely clear, the available evidence suggests that both complexes are unable to activate transcription (reviewed in reference 36). In agreement with previous findings, these results suggest that in untransformed cells expression of the cyclin A gene is controlled through specific alterations in p107-containing E2F complexes (66); the results reported here further indicate that free E2F does not contribute to promoter activation in this cell type, as free E2F is excluded from the nuclear compartment (Fig. 5B). In contrast, free E2F was the major form of E2F in nuclei of E7-expressing cells, irrespective of the culture conditions. Since free E2F acts as a positive transcription factor, in vitro (15) and probably also in vivo (reviewed in reference 36), this finding suggests that the accumulation of free E2F in the nuclei of E7-expressing cells prevents downregulation of cyclin A gene expression in suspension.

According to the current model (47), the accumulation of free E2F in E7-expressing NIH 3T3 cells may result from disruption of E2F-pocket protein complexes by E7. This is supported by the ability of recombinant E7 protein to disrupt a subset of E2F-p107 complexes in vitro (9, 63, 64), including complexes formed on the E2F site of the cyclin A promoter (56a). Since disruption of E2F complexes by E7 relies on direct physical interaction, the degree of disruption should depend on the actual concentration of E7. In agreement with this assumption, a very low level of E2F-p107 complexes was found in extracts of E7/2 cells, whereas E2F-p107 complexes were of intermediate abundance in extracts from E7/4 cells containing lower levels of E7 protein. Besides physical disruption of higher-order E2F complexes, several additional ways by which E7 may contribute to the increased levels of free E2F observed in E7-expressing cells can be anticipated. First, phosphorylation of pRb family members by cdk’s can lead to a release of free E2F from pocket proteins (reviewed in reference 5). However, we found that pRb, p107, and p130 all remain hypophosphorylated in extracts from suspension cells, irrespective of E7 gene expression. This observation correlates with the inability of E7 to rescue cyclin D1 gene expression in suspension cells (Fig. 2A), given the key role of cyclin D-associated kinase for the phosphorylation of pRb family members (reviewed in reference 5). It was also shown that under certain conditions, E7 triggers the proteolytic degradation of pRb (7), which may contribute to the generation of free E2F. Indeed we found a slight reduction of the steady-state levels of all three pRb family members in E7/4 cells when they were grown on uncoated dishes (Fig. 2E). However, the respective expression levels were very similar for all three proteins when E7-expressing and control cells were compared after culture in suspension. Thus, the changes observed in the levels of free E2F in suspension cells are not related to alterations in the steady-state levels of the pocket proteins in the experimental cell lines used here.

Nuclear localization of free E2F in E7-expressing cells.

From the ability of E7-expressing cells to enter S phase after actinomycin D-induced upregulation of p21 gene expression, Morozov et al. concluded that cdk2 activity is not absolutely required for S-phase entry (45); according to these authors, the ability of these cells to enter S phase depends on the ability of E7 to trigger some regulatory steps that are encoded downstream of cdk2 in an independent pathway, e.g., E7-dependent activation of E2F-driven genes. This interpretation is supported by the observation that ectopic overexpression in mammalian cells of at least one E2F family member, namely, E2F-1, leads to S-phase entry without the requirement for active cdk2 (11). Consistent with a role for E2F in E7-induced S-phase entry, we found that free E2F persists in E7-expressing cells in suspension. Surprisingly, expression of E7 led to nuclear accumulation of one species of free E2F, namely, an E2F-4–DP-1 heterodimer, that was reported to depend on association with a pRb family member for nuclear transport. When we coexpressed E2F-4 and DP-1 with E7 in the absence of p107, we found that E2F-4–DP-1 heterodimers remained cytoplasmic (Fig. 6A), indicating that E7 is not sufficient for nuclear localization of isolated E2F-4–DP-1 heterodimers. It appears that while p107 may be responsible for the actual transport of E2F-4–DP-1 complexes into the nucleus, E7 disrupts nuclear E2F-p107 complexes and prevents the redistribution of free E2F to the cytoplasm. Alternatively, it is conceivable that the stability of nuclear free E2F is increased by E7. In a precedent-setting study, it was shown that proteins encoded by adenovirus early region 1 increase the half-life of free E2F (22). Our finding that free E2F is constitutive in E7-expressing cells suggests that deregulation of E2F-controlled genes, including the cyclin A gene, contributes to the ability of such cells to override G1 arrest in response to loss of adhesion, in agreement with previous findings (20).

Pathways contributing to E7-mediated anchorage-independent growth.

The phenotype of the PRO2 mutant suggests that at least two separate pathways are targeted by E7 to override the G1 block in nonadherent cells. This conclusion is further supported by our findings that the PRO2 mutant E7 protein disrupts E2F-p107 complexes as efficiently as wild-type E7 (Fig. 4C) and that free E2F is nuclear in PRO2 cells (56a). This finding may explain why PRO2, although it is unable to rescue cyclin E-associated kinase activity, still activates cyclin A gene expression in nonadherent cells. In an additional control experiment, we found that E7-dependent transactivation of the cyclin A promoter is reduced by about 50% in response to coexpression of a dominant negative mutant of cdk2 (56a, 62). These results suggest that there are at least two separate E7-dependent processes driving transcription of the cyclin A gene. First, an E7-dependent increase of cyclin E-associated kinase activity will induce phosphorylation and inactivation of the repressor molecule p107. Second, another pathway, the p107-E2F complex can be directly disrupted through binding of E7 and hence cyclin-associated kinase activities are not required. The results reported here indicate that the ability of E7 to activate cyclin A transcription in growth-arrested cells depends to some extent on the experimental conditions. Thus, PRO2 induces moderate levels of cyclin A mRNA (25% of that of the wild type) in serum-starved cells, compared to quite high levels (50% of that of the wild type) in nonadherent cells. This difference is mirrored by the results obtained in transient transfections: while in nonadherent cells the level of transactivation of the cyclin A promoter by PRO2 reached 80% of the wild-type level, in serum-starved cells the PRO2 mutant protein was significantly weaker (50% of wild-type activity [65]). While we had shown before that, in the absence of E7, activation of cyclin A transcription requires cyclin E-associated kinase (66), the present data suggest that in E7-expressing cells cyclin A transcription is to a certain extent independent of kinase activity, in particular in nonadherent cells. Taken together, the data reported here indicate that several different E7-dependent changes of cellular growth-regulating pathways can cooperate to allow adhesion-independent cyclin A gene expression and S-phase entry, most notably by the disruption of p107-E2F complexes and the activation of cyclin E-associated kinase. Our data further suggest as a novel activity of E7 its ability to promote the retention of free E2F in the nucleus.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Rene Bernards, Jiri Bartek, Nick LaThangue, Joris Braspenning, and Nick Dyson for various antibodies and communication of results prior to publication.

This work was supported by grants from the European Union (Biomed 2 program) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arroyo M, Bagchi S, Raychaudhuri P. Association of the human papillomavirus type-16 E7 protein with the S-phase-specific E2F–cyclin-A complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6537–6546. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.6537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Assoian R K, Zhu X Y. Cell anchorage and the cytoskeleton as partners in growth factor dependent cell cycle progression. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:93–98. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldin V, Lukas J, Marcote M J, Pagano M, Draetta G. Cyclin D1 is a nuclear protein required for cell cycle progression in G1. Genes Dev. 1993;7:812–821. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.5.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banks L, Edmonds C, Vousden K H. Ability of the HPV16 E7 protein to bind RB and induce DNA synthesis is not sufficient for efficient transforming activity in NIH3T3 cells. Oncogene. 1990;5:1383–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beijersbergen R L, Bernards R. Cell cycle regulation by the retinoblastoma family of growth inhibitory proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1287:103–120. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(96)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bohmer R M, Scharf E, Assoian R K. Cytoskeletal integrity is required throughout the mitogen stimulation phase of the cell cycle and mediates the anchorage-dependent expression of cyclin D1. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:101–111. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyer S N, Wazer D E, Band V. E7 protein of human papilloma virus-16 induces degradation of retinoblastoma protein through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4620–4624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buck V, Allen K E, Sorensen T, Bybee A, Hijmans E M, Voorhoeve P M, Bernards R, Lathangue N B. Molecular and functional characterisation of E2F-5, a new member of the E2F family. Oncogene. 1995;11:31–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chellappan S, Kraus V, Kroger B, Münger K, Howley P M, Phelps W, Nevins J R. Adenovirus E1A, simian virus 40 tumor antigen, and human papillomavirus E7 protein share the capacity to disrupt the interaction between transcription factor E2F and the retinoblastoma gene product. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4549–4553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies R, Hicks R, Crook T, Morris J, Vousden K. Human papillomavirus type-16 E7 associates with a histone H1 kinase and with p107 through sequences necessary for transformation. J Virol. 1993;67:2521–2528. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.5.2521-2528.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Degregori J, Leone G, Ohtani K, Miron A, Nevins J R. E2F-1 accumulation bypasses a G1 arrest resulting from the inhibition of G1 cyclin-dependent kinase activity. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2873–2887. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.23.2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delaluna S, Burden M J, Lee C W, Lathangue N B. Nuclear accumulation of the E2F heterodimer regulated by subunit composition and alternative splicing of a nuclear localization signal. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:2443–2452. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.10.2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demers G W, Espling E, Harry J B, Etscheid B G, Galloway D A. Abrogation of growth arrest signals by human papillomavirus type 16 E7 is mediated by sequences required for transformation. J Virol. 1996;70:6862–6869. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6862-6869.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demers G W, Foster S A, Halbert C L, Galloway D A. Growth arrest by induction of p53 in DNA damaged keratinocytes is bypassed by human papillomavirus 16 E7. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4382–4386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dynlacht B, Flores O, Lees J A, Harlow E. Differential regulation of E2F trans-activation by cyclin/cdk2 complexes. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1772–1786. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.15.1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dyson N, Guida P, Münger K, Harlow E. Homologous sequences in adenovirus E1A and human papillomavirus E7 proteins mediate interactions with the same set of cellular proteins. J Virol. 1992;66:6893–6902. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.6893-6902.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edmonds C, Vousden K. A point mutational analysis of human papillomavirus type 16 E7 protein. J Virol. 1989;63:2650–2656. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.6.2650-2656.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fang F, Orend G, Watanabe N, Hunter T, Ruoslahti E. Dependence of cyclin E-CDK2 kinase activity on cell anchorage. Science. 1996;271:499–502. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5248.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Funk J, Waga S, Harry J, Espling E, Stillman B, Galloway D. Inhibition of cdk activity and PCNA-dependent DNA replication by p21 is blocked by interaction with the HPV-16 E7 oncoprotein. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2090–2100. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.16.2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guadagno T, Ohtsubo M, Roberts J M, Assoian R. A link between cyclin A expression and adhesion-dependent cell cycle progression. Science. 1993;262:1572–1575. doi: 10.1126/science.8248807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hagen G, Dennig J, Preiss A, Beato M, Suske G. Functional analyses of the transcription factor Sp4 reveal properties distinct from Sp1 and Sp3. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:24989–24994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.24989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hateboer G, Kerkhoven R M, Shvarts A, Bernards R, Beijersbergen R L. Degradation of E2F by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway: regulation by retinoblastoma family proteins and adenovirus transforming proteins. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2960–2970. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.23.2960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawley-Nelson P, Vousden K H, Hubbert N L, Lowy D R, Schiller J T. HPV16 E6 and E7 proteins cooperate to immortalize human foreskin keratinocytes. EMBO J. 1989;8:3905–3910. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08570.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Helin K, Wu C L, Fattaey A R, Lees J A, Dynlacht B D, Ngwu C, Harlow E. Heterodimerization of the transcription factors E2F-1 and DP-1 leads to cooperative trans-activation. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1850–1861. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.10.1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henglein B, Chenivesse X, Wang J, Eick D, Brechot C. Structure and cell cycle regulated transcription of the human cyclin A gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5490–5494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hickman E S, Bates S, Vousden K H. Perturbation of the p53 response by human papillomavirus type 16 E7. J Virol. 1997;71:3710–3718. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3710-3718.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hickman E S, Picksley S M, Vousden K H. Cells expressing HPV16 E7 continue cell cycle progression following DNA damage induced p53 activation. Oncogene. 1994;9:2177–2181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hijmans E M, Voorhoeve P M, Beijersbergen R L, Vantveer L J, Bernards R. E2F-5, a new E2F family member that interacts with p130 in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3082–3089. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howe J A, Howell M, Hunt T, Newport J W. Identification of a developmental timer regulating the stability of embryonic cyclin A and a new somatic A-type cyclin at gastrulation. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1164–1176. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.10.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jansen-Dürr P, Meichle A, Steiner P, Pagano M, Finke K, Botz J, Weßbecher J, Draetta G, Eilers M. Differential modulation of cyclin gene expression by MYC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2547–2552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jewers R, Hildebrandt P, Ludlow J, Kell B, McCance D. Regions of HPV 16 E7 oncoprotein required for immortalization of human keratinocytes. J Virol. 1992;66:1329–1335. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1329-1335.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones D L, Alani R M, Münger K. The human papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein can uncouple cellular differentiation and proliferation in human keratinocytes by abrogating p21CIP1-mediated inhibition of cdk2. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2101–2111. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.16.2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones D L, Munger K. Analysis of the p53-mediated G1 growth arrest pathway in cells expressing the human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncoprotein. J Virol. 1997;71:2905–2912. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2905-2912.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanda T, Furuno A, Yoshiike K. Human papillomavirus type 16 open reading frame E7 encodes a transforming gene for rat 3Y1 cells. J Virol. 1988;62:610–613. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.2.610-613.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Land H, Parada L F, Weinberg R A. Cellular oncogenes and multistep carcinogenesis. Science. 1983;222:771–778. doi: 10.1126/science.6356358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lathangue N B. E2F and the molecular mechanisms of early cell-cycle control. Biochem Soc Trans. 1996;24:54–59. doi: 10.1042/bst0240054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindeman G J, Gaubatz S, Livingston D M, Ginsberg D. The subcellular localization of E2F-4 is cell-cycle dependent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5095–5100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lukas J, Müller H, Bartkova J, Spitkovsky D, Kjerulff A, Jansen-Dürr P, Strauss M, Bartek J. DNA tumour viruses, oncoproteins and retinoblastoma gene mutations share the ability to relieve the cell’s requirement for cyclin D1 function in G1. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:625–638. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.3.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lukas J, Pagano M, Staskova Z, Draetta G, Bartek J. Cyclin D1 protein oscillates and is essential for cell cycle progression in human tumour cell lines. Oncogene. 1994;9:707–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Magae J, Wu C L, Illenye S, Harlow E, Heintz N H. Nuclear localization of DP and E2F transcription factors by heterodimeric partners and retinoblastoma protein family members. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:1717–1726. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.7.1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsushime H, Quelle D E, Shurtleff S A, Shibuya M, Sherr C J, Kato J Y. D-type cyclin-dependent kinase activity in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2066–2076. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mayol X, Garriga J, Grana X. Cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma-related protein p130. Oncogene. 1995;11:801–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McIntyre M C, Frattini M G, Grossman S R, Laimins L A. Human papillomavirus type-18 E7 protein requires intact Cys-X-X-Cys motifs for zinc binding, dimerization, and transformation but not for Rb binding. J Virol. 1993;67:3142–3150. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3142-3150.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McIntyre M C, Ruesch M N, Laimins L A. Human papillomavirus E7 oncoproteins bind a single form of cyclin E in a complex with cdk2 and p107. Virology. 1996;215:73–82. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morozov A, Shiyanov P, Barr E, Leiden J M, Raychaudhuri P. Accumulation of human papillomavirus type 16 E7 protein bypasses G1 arrest induced by serum deprivation and by the cell cycle inhibitor p21. J Virol. 1997;71:3451–3457. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3451-3457.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Münger K, Phelps W C, Bubb V, Howley P M, Schlegel R. The E6 and E7 genes of human papillomavirus type 16 together are necessary and sufficient for transformation of primary human keratinocytes. J Virol. 1989;63:4417–4421. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.10.4417-4421.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nevins J R. E2F: a link between the Rb tumor suppressor protein and viral oncoproteins. Science. 1992;258:424–429. doi: 10.1126/science.1411535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohtani K, Degregori J, Nevins J R. Regulation of the cyclin E gene by transcription factor E2F1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:12146–12150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ohtsubo M, Theodoras A M, Schumacher J, Roberts J M, Pagano M. Human cyclin E, a nuclear protein essential for the G1-to-S phase transition. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2612–2624. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pagano M, Dürst M, Joswig S, Draetta G, Jansen-Dürr P. Binding of the human E2F transcription factor to the retinoblastoma protein but not to cyclin A is abolished in HPV-16-immortalized cells. Oncogene. 1992;7:1681–1686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pagano M, Pepperkok R, Lukas J, Baldin V, Ansorge W, Bartek J, Draetta G. Regulation of the human cell cycle by the Cdk2 protein kinase. J Cell Biol. 1993;121:101–111. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Phelps W C, Bagchi S, Barnes J A, Raychaudhuri P, Kraus V, Münger K, Howley P M, Nevins J R. Analysis of trans activation by human papillomavirus type 16 E7 and adenovirus 12S E1A suggests a common mechanism. J Virol. 1991;65:6922–6930. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.6922-6930.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Phelps W C, Münger K, Yee C L, Barnes J A, Howley P M. Structure-function analysis of the human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncoprotein. J Virol. 1992;66:2418–2427. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2418-2427.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Phelps W C, Yee C L, Münger K, Howley P M. The human papillomavirus type 16 E7 gene encodes transactivation and transformation functions similar to those of adenovirus E1A. Cell. 1988;53:539–547. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90570-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Resnitzky D, Hengst L, Reed S I. Cyclin A-associated kinase activity is rate limiting for entrance into S phase and is negatively regulated in G1 by p27Kip1. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4347–4352. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ruesch M, Laimins L. Initiation of DNA synthesis by human papillomavirus E7 oncoproteins is resistant to p21-mediated inhibition of cyclin E-cdk2 activity. J Virol. 1997;71:5570–5578. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5570-5578.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56a.Schulze, A. Unpublished results.

- 57.Schulze A, Zerfaß K, Spitkovsky D, Berges J, Middendorp S, Jansen-Dürr P, Henglein B. Cell cycle regulation of cyclin A gene transcription is mediated by a variant E2F binding site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11264–11268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schulze A, Zerfass-Thome K, Berges J, Middendorp S, Jansen-Dürr P, Henglein B. Anchorage-dependent transcription of the cyclin A gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4632–4638. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spitkovsky D, Schulze A, Boye B, Jansen-Dürr P. Downregulation of cyclin A gene expression upon genotoxic stress correlates with reduced binding of free E2F to the promoter. Cell Growth Differ. 1997;8:699–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tani K, Yoshida M C, Satoh H, Mitamura K, Noguchi T, Tanaka T, Fujii H, Miwa S. Human M2-type pyruvate kinase: cDNA cloning, chromosomal assignment and expression in hepatoma. Gene. 1988;73:509–516. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90515-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tommasino M, Adamczewski J P, Carlotti F, Barth C F, Manetti R, Contorni M, Cavalieri F, Hunt T, Crawford L. HPV16 E7 protein associates with the protein kinase p33CDK2 and cyclin A. Oncogene. 1993;8:195–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van den Heuvel S, Harlow E. Distinct roles for cyclin-dependent kinases in cell cycle control. Science. 1993;262:2050–2054. doi: 10.1126/science.8266103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu E W, Clemens K E, Heck D V, Munger K. The human papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein and the cellular transcription factor E2F bind to separate sites on the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein. J Virol. 1993;67:2402–2407. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2402-2407.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zerfaß K, Levy L, Cremonesi C, Ciccolini F, Jansen-Dürr P, Crawford L, Ralston R, Tommasino M. Cell cycle dependent disruption of E2F/p107 complexes by human papillomavirus type 16 E7. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:1815–1820. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-7-1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zerfass K, Schulze A, Spitkovsky D, Friedman V, Henglein B, Jansen-Dürr P. Sequential activation of cyclin E and cyclin A gene expression by human papillomavirus type 16 E7 through sequences necessary for transformation. J Virol. 1995;69:6389–6399. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6389-6399.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zerfaß-Thome K, Schulze A, Zwerschke W, Vogt B, Helin K, Bartek J, Henglein B, Jansen-Dürr P. p27KIP1 blocks cyclin E-dependent trans-activation of cyclin A gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:407–415. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zerfass-Thome K, Zwerschke W, Mannhardt B, Tindle R, Botz J, Jansen-Dürr P. Inactivation of the cdk inhibitor p27KIP1 by the human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncoprotein. Oncogene. 1996;13:2323–2330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhu X Y, Ohtsubo M, Bohmer R M, Roberts J M, Assoian R K. Adhesion-dependent cell cycle progression linked to the expression of cyclin D1, activation of cyclin E-cdk2, and phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:391–403. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.2.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.zur Hausen H. Human papillomaviruses in the pathogenesis of anogenital cancer. Virology. 1991;184:9–13. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90816-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.zur Hausen H, Schneider A. The role of papillomaviruses in human anogenital cancer. In: Howley P M, Salzman N, editors. The Papovaviridae: the papillomaviruses. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1987. pp. 245–263. [Google Scholar]