Abstract

Background

Adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD) is a multifaceted, X-linked, neurodegenerative disorder that comprises several clinical phenotypes. ALD affects patients through a variety of physical, emotional, social, and other disease-specific factors that collectively contribute to disease burden. To facilitate clinical care and research, it is important to identify which symptoms are most common and relevant to individuals with any subtype of ALD.

Methods

We conducted semi-structured qualitative interviews and an international cross-sectional study to determine the most prevalent and important symptoms of ALD. Our study included adult participants with a diagnosis of ALD who were recruited from national and international patient registries. Responses were categorized by age, sex, disease phenotype, functional status, and other demographic and clinical features.

Results

Seventeen individuals with ALD participated in qualitative interviews, providing 1709 direct quotes regarding their symptomatic burden. One hundred and nine individuals participated in the cross-sectional survey study, which inquired about 182 unique symptoms representing 24 distinct symptomatic themes. The symptomatic themes with the highest prevalence in the overall ALD sample cohort were problems with balance (90.9%), limitations with mobility or walking (87.3%), fatigue (86.4%), and leg weakness (86.4%). The symptomatic themes with the highest impact scores (on a 0–4 scale with 4 being the most severe) were trouble getting around (2.35), leg weakness (2.25), and problems with balance (2.21). A higher prevalence of symptomatic themes was associated with functional disability, employment disruption, and speech impairment.

Conclusions

There are many patient-relevant symptoms and themes that contribute to disease burden in individuals with ALD. These symptoms, identified by those having ALD, present key targets for further research and therapeutic development.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13023-024-03129-6.

Keywords: Adrenoleukodystrophy, Adrenomyeloneuropathy, Symptom, Disease burden, Qualitative research, Patient interview, Cross-sectional study, Patient-reported

Background

Adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD) is an X-linked genetic condition caused by mutations in an ATP-binding cassette gene (ABCD1) that encodes an ABC transporter, which is involved in transporting very long chain fatty acids (VLCFs) to the peroxisome for degradation [1–6]. As a result of the mutations (more than 600 known pathogenic variants), VLCFs are not able to be properly processed, and they accumulate in the tissues, causing a host of issues that present with varying phenotypes according to age, sex, and clinical characteristics [7, 8]. The three core clinical phenotypes of ALD are (1) a slowly progressive myeloneuropathy (adrenomyeloneuropathy or AMN); (2) a rapidly progressive leukodystrophy (cerebral ALD); and (3) primary adrenal insufficiency (Addison’s disease) [9, 10]. Both women and men can be affected by AMN (also called symptomatic ALD in women) [10]. Cerebral ALD and Addison’s disease predominantly occur in men (women affected at < 1%) [10]. Additionally, women with ALD may remain completely asymptomatic throughout their lives despite being gene carriers (termed asymptomatic women with ALD) [10]. Although ALD can be detected through newborn screening (genetic testing and/or biochemical testing), age of symptom onset is variable, ranging from childhood-adulthood for males presenting with cerebral ALD and/or adrenal insufficiency to adulthood for males and females presenting with AMN [10, 11].

As a whole, ALD is recognized as the most common peroxisomal disorder, affecting approximately 1 in 16,800 in the U.S. (includes children and adults; symptomatic and asymptomatic men and women) [6].

Clinical manifestations of ALD depend on the specific phenotype associated with the condition. The most common symptoms of AMN include weakness and spasticity in the legs, abnormal sphincter control, neurogenic bladder, sexual dysfunction, numbness, and pain [12]. Cerebral ALD may show up as learning disabilities, behavioral abnormalities, cognitive decline, impaired vision and/or auditory discrimination, and seizures [13, 14]. Addison’s disease may cause symptoms such as fatigue, muscle weakness, low mood/mild depression, nonspecific gastrointestinal issues, vomiting, weakness, and headaches [15–17].

While a few treatment options exist for individuals with ALD, again depending on the particular phenotype (spasticity-reducing medications and neuropathic pain medications for AMN, hematopoietic stem cell transplant for cerebral ALD, and glucocorticoid replacement for Addison’s disease), there are no cures [9, 18]. In order to facilitate clinical care and identify potential targets for therapeutic intervention, it is important to better understand the most salient symptoms to patients from the perspective of those with ALD (including all phenotypes).

In this study, we collected data from semi-structured interviews with individuals with ALD and subsequently conducted a large cross-sectional study to identify the most prevalent and impactful symptoms to individuals with this disease, including all subtypes. This information will help guide researchers, clinicians, and therapy developers to better care for and treat all patients with ALD.

Methods

Study participants

Participants for this study were recruited from the following organizations: ALD Connect (active in the U.S. and Canada); the United Leukodystrophy Foundation (active in the U.S.); Alex—The Leukodystrophy Charity (active in the U.K.); Fundación Lautaro te Necesita—Leukodystrophy Foundation (active in South America); The Leukodystrophy Resource Research Organization (LRRO) (active in Australia); Royal Children’s Hospital and Massimo’s Mission (active in Australia); and Leukodystrophy Australia (active in Australia). Eligible participants were those who: (1) were age 18 or older; (2) had a general diagnosis of ALD or a specific diagnosis to include AMN, cerebral ALD, Addison’s disease, and/or asymptomatic women with ALD; and, (3) were able to speak, read, and understand English.

All study activities were approved by the University of Rochester Institutional Review Board, and participants were required to provide informed consent prior to taking part in interviews and/or the cross-sectional study. Interviews were conducted between May 17, 2021 and July 23, 2021, and the subsequent cross-sectional study was conducted between November 2, 2021 and January 17, 2022.

Study design

ALD qualitative interviews

We conducted 30–60 min semi-structured qualitative interviews with individuals with all types of ALD to identify the symptoms that have the greatest impact on their lives. Potential participants were informed of the purpose of the study, the risks and benefits, and their rights prior to providing consent via phone.

Three clinical research coordinators (SR, JW, JS) conducted the participant interviews. The interviewers asked open-ended questions regarding the physical, mental, emotional, social, and everyday health of the participants. For example, participants were asked “which symptoms have the greatest impact on a person’s quality-of-life or disease burden?,” “how is a person with ALD/AMN affected physically and emotionally by the disease,” and “what are the little things that are affected by and important to people with ALD/AMN?,” among other questions. The interviews were recorded via Zoom (a HIPAA-compliant conferencing software), transcribed, and coded by the research team (SR, JW, JS, AV, and CH) to analyze direct participant quotes, pinpoint unique symptoms, and classify symptoms into symptomatic themes (groups of related symptoms). This coding process followed a qualitative framework technique and multi-investigator consensus approach that has been used in previous studies of other diseases [19–27]. We conducted interviews until data saturation was reached [28].

International cross-sectional study of individuals with ALD

We constructed a survey that included the symptoms and symptomatic themes that were brought up by participants repeatedly during qualitative interviews as well as those that have been identified by experts in this field as being important to patients with any phenotype of ALD. We implemented this survey in an international cross-sectional study with individuals with all types of ALD to determine the prevalence and relative importance of these symptoms and themes. The survey was administered via REDCap (a HIPAA-compliant electronic data capture system) and was accessible to participants through a public survey link distributed by partnering recruitment organizations. Participants were first directed to read a patient information letter and General Data Protection Legislation (GDPR) notice (for participants from the European Union or United Kingdom). Participants then completed an online consent form and answered demographic and clinical questions prior to taking the symptom survey. The symptom survey inquired about 182 symptoms representing 24 symptomatic themes. For each symptom question, individuals were asked, “how much does the following impact your life now?” They were presented with a 6-point Likert-type scale to record their responses; the scale consisted of the following options: (1) I don’t experience this; (2) I experience this but it does not affect my life; (3) It affects my life a little; (4) It affects my life moderately; (5) It affects my life very much; (6) It affects my life severely. Individuals had the option to decline to answer any question. At the end of the survey, participants were asked to list and rank the impact of any other symptoms that were not included on the survey.

Statistical analysis

Participants who met the inclusion criteria and who completed at least 1 demographic question and 1 symptom question on the cross-sectional survey were included in the data analysis. We used the data from the cross-sectional study to calculate the prevalence and impact of each symptom and symptomatic theme. Prevalence was calculated as the number of participants who experienced a symptom (options 2–6 on the Likert scale) normalized by the total number of participants who responded to the symptom question. Impact scores, on a scale of 0–4, were computed by assigning numerical values to each of the rating options on the Likert scale for all participants who reported experiencing the symptom: 0 = I experience this but it does not affect my life; 1 = It affects my life a little; 2 = It affects my life moderately; 3 = It affects my life very much; 4 = It affects my life severely.

Population impact (PIP) scores, on a scale of 0–4, were calculated by multiplying the prevalence, of the symptom by the average life impact score of the symptom. A score of 0 corresponded to no impact on the population, whereas a score of 4 corresponded to the highest possible impact to the population. The methods performed here have been described and validated previously for other diseases [19–27].

In addition to ascertaining the prevalence and importance of symptoms and themes in our sample, we compared the prevalence of the symptomatic themes in predetermined subcategories based on age (above mean vs. equal to/below mean); sex (male vs. female); education level (grade school, high school, technical degree, or none vs. college, master’s, or doctorate); employment status (working full-time, working part-time, or stay-at-home parent vs. on disability or not working/not on disability; excluding students, retired individuals, others); disability status (on disability vs. all other employment categories not on disability); and has ALD impacted employment status (yes vs. no). Data was also categorized based on other, disease-specific criteria, specifically number of years since first noticed symptoms (above mean vs. equal to/below mean); diagnosis of AMN (yes vs. no); diagnosis of cerebral ALD (yes vs. no); diagnosis of Addison’s disease/adrenal insufficiency (yes vs. no); ambulatory status (walk independently vs. use a cane, crutches, walker, or motorized scooter); speech status (talk clearly vs. speech change); functional ability (no symptoms, no significant disability vs. slight disability, moderate disability, moderately severe disability, severe disability); and hours of home health aide per week (none vs. some aide). Fisher exact tests were used to compare the prevalence of each symptomatic theme between groups. These tests were exploratory and are reported for descriptive purposes only. To correct for multiple comparisons, the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure was used with a false discovery rate of 0.05 and 336 test statistics. As outlined by this method, the 336 p values were sorted from smallest to largest and the largest value of i such that p(i) ≤ 0.05 i/336 was determined. The null hypotheses associated with the p values p(1), …, p(i) were rejected, resulting in 56 “discoveries.”

Results

ALD qualitative interviews

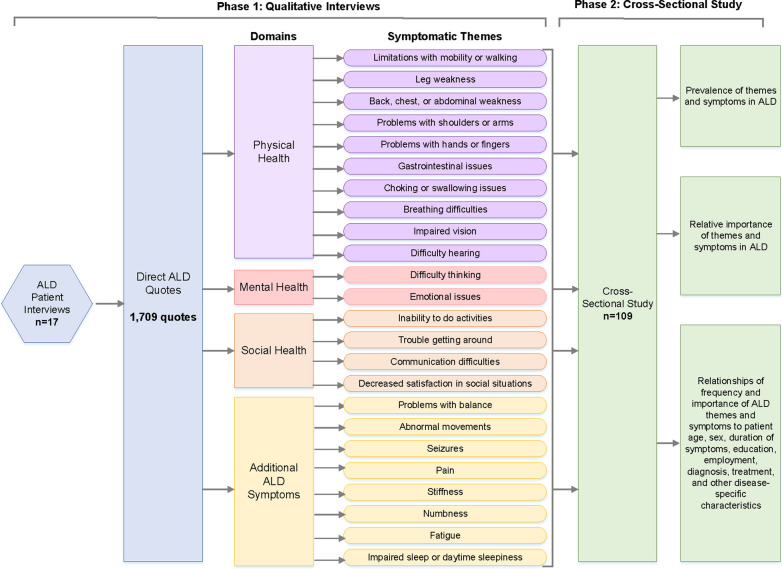

We performed 17 interviews with individuals with ALD, including all phenotypes (AMN, cerebral ALD, Addison’s disease, and asymptomatic women with ALD). The interviewees consisted of 15 men (88.2%) and 2 women (11.8%) with ALD, and the ages ranged from 23 to 73 years with the mean age being 48 ± 13 years. The demographics of these participants are provided in Table 1. Through these interviews, we obtained 1709 direct quotes regarding patient-perceived symptoms of importance. From these quotes, 182 unique symptoms were extracted and grouped into 24 symptomatic themes. These themes were limitations with mobility or walking; problems with balance; inability to do activities; trouble getting around; leg weakness; pain; stiffness; fatigue; gastrointestinal issues; decreased satisfaction in social situations; emotional issues; communication difficulties; difficulty thinking; impaired sleep or daytime sleepiness; back, chest, or abdominal weakness; problems with shoulders or arms; numbness; choking or swallowing issues; abnormal movements; problems with hands or fingers; breathing difficulties; seizures; impaired vision; and difficulty hearing.

Table 1.

Participant demographics for ALD interviews

| Interviews completed, n | 17 |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 15 (88.2) |

| Female | 2 (11.8) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 16 (94.1) |

| Omitted | 1 (5.9) |

| Hispanic or Latino, n (%) | |

| Yes | 1 (5.9) |

| No | 16 (94.1) |

| Age in years | |

| Mean ± 1 SD | 48 ± 13 |

| Range | 23–72 |

| Age at diagnosis in years | |

| Mean ± 1 SD | 30 ± 17 |

| Range | 2 to 62 |

| Ambulatory status, n (%) | |

| Fully ambulatory, no assistance | 3 (17.6) |

| Ambulatory with canes/assistance | 9 (53.0) |

| Non-ambulatory/wheelchair | 5 (29.4) |

| U.S. states represented, n | 8 |

Multiple-choice options that were not selected by any participant have been omitted for conciseness

Percents have been normalized for missing responses

International cross-sectional study of individuals with ALD

A total of 158 participants responded to our cross-sectional survey with 109 respondents meeting our inclusion criteria for data analysis. This sample comprised 47 men (43.1%) and 62 women (56.9%), who represented a range of ages from 18 to 83 years with a mean age of 51 ± 17 years. The majority of participants identified as white (98 people; 89.9%) and non-Hispanic/Latino (94 people; 86.2%). Participants represented 16 countries, spanning the continents of North America, South America, Europe, Asia, and Australia. One Canadian province (Ontario) and 21 U.S. states were represented.

In our sample cohort, 59 people (54.1%) reported being diagnosed with general ALD; 71 people (65.1%) with AMN; 18 people (16.5%) with the cerebral form of ALD; and 35 people (32.1%) with Addison’s disease. These categories were not mutually exclusive. The average number of years since symptom onset was 15 ± 11 years, and the average number of years since diagnosis was 16 ± 11 years.

Table 2 provides additional details regarding the demographics of participants in the cross-sectional study. Figure 1 provides a complete outline of our study activities.

Table 2.

Participant demographics for ALD cross-sectional study

| Cross-sectional study participants, n | 109 |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 47 (43.1) |

| Female | 62 (56.9) |

| Age in years | |

| Mean ± 1 SD | 51 ± 17 |

| Range | 18–83 |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Asian | 3 (2.8) |

| Black/African American | 1 (0.9) |

| White | 98 (89.9) |

| Other | 7 (6.4) |

| Hispanic or Latino, n (%) | |

| Yes | 15 (13.8) |

| No | 94 (86.2) |

| Country, n (%) (16 total countries represented) | |

| United States | 54 (49.5) |

| Canada | 5 (4.6) |

| Australia | 10 (9.7) |

| United Kingdom | 16 (14.7) |

| France | 2 (1.8) |

| Argentina | 7 (6.4) |

| Bolivia | 2 (1.8) |

| Chile | 1 (0.9) |

| India | 1 (0.9) |

| Iran | 1 (0.9) |

| Ireland | 3 (2.8) |

| Mexico | 1 (0.9) |

| New Zealand | 3 (2.8) |

| Poland | 1 (0.9) |

| South Korea | 1 (0.9) |

| Sweden | 1 (0.9) |

| U.S. states represented, n | 21 |

| Canadian provinces represented (Ontario), n | 1 |

| Employment status, n (%) | |

| Employed full-time | 29 (26.6) |

| Employed part-time | 9 (8.3) |

| On disability | 16 (14.7) |

| Not working/not on disability | 8 (7.3) |

| Retired | 30 (27.5) |

| Student | 6 (5.5) |

| Stay-at-home parent | 1 (0.9) |

| Self-employed | 7 (6.4) |

| Other | 3 (2.8) |

| Has ALD impacted your employment status or choice?, n (%) | |

| Yes | 60 (55.1) |

| No | 40 (36.7) |

| I don't know | 8 (7.3) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (0.9) |

| Highest level of education, n (%) | |

| Grade school | 2 (1.8) |

| High school | 29 (26.6) |

| Technical degree | 19 (17.5) |

| College | 33 (30.3) |

| Master's or Doctorate | 24 (22.0) |

| None | 2 (1.8) |

| Has ALD prevented you from pursuing additional education?, n (%) | |

| Yes | 18 (16.5) |

| No | 87 (79.8) |

| I don't know | 4 (3.7) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Married | 61 (56.0) |

| Single | 26 (23.9) |

| Widowed | 3 (2.7) |

| Divorced | 13 (12.0) |

| Separated | 3 (2.7) |

| Registered partnership | 3 (2.7) |

| Has ALD impacted your marital status or decision to pursue relationships?, n (%) | |

| Yes | 35 (32.1) |

| No | 70 (64.2) |

| I don't know | 4 (3.7) |

| Diagnosed with ALD?, n (%) | |

| Yes | 59 (54.1) |

| No | 43 (39.5) |

| I don't know | 7 (6.4) |

| Diagnosed with AMN?, n (%) | |

| Yes | 71 (65.1) |

| No | 27 (24.8) |

| I don't know | 11 (10.1) |

| Diagnosed with cerebral form of ALD?, n (%) | |

| Yes | 18 (16.5) |

| No | 81 (74.3) |

| I don't know | 10 (9.2) |

| Diagnosed with Addison's disease?, n (%) | |

| Yes | 35 (32.1) |

| No | 71 (65.1) |

| I don't know | 3 (2.8) |

| Ever been in adrenal crisis?, n (%) | |

| Yes | 22 (20.2) |

| No | 82 (75.2) |

| I don't know | 5 (4.6) |

| Years since diagnosis | |

| Mean ± 1 SD | 16 ± 11 |

| Range | 1–40 |

| Years since first noticed symptoms | |

| Mean ± 1 SD | 15 ± 11 |

| Range | 0–50 |

| Ever misdiagnosed?, n (%) | |

| Yes | 38 (34.9) |

| No | 68 (62.4) |

| I don't know | 3 (2.7) |

| Ambulation, n (%) | |

| Walk independently without assistance | 50 (45.9) |

| Primarily use a cane or crutches | 34 (31.2) |

| Primarily use a walker | 10 (9.2) |

| Use a wheelchair or motorized scooter sometimes and walk sometimes | 7 (6.4) |

| Primarily use a wheelchair or motorized scooter | 8 (7.3) |

| Hours of home health aide per week, n (%) | |

| None | 75 (68.8) |

| 1–5 h | 15 (13.8) |

| 6–10 h | 6 (5.5) |

| 16–20 h | 3 (2.7) |

| Greater than 20 h | 10 (9.2) |

| Speech, n (%) | |

| Talk clearly and have no changes in speech | 89 (81.7) |

| Some speech changes | 17 (15.6) |

| Impaired speech, and people occasionally ask to repeat words or phrases | 2 (1.8) |

| Impaired speech that is often not understood by others | 1 (0.9) |

| Positive genetic test for ABCD1 gene mutation?, n (%) | |

| Yes | 89 (81.6) |

| No | 5 (4.6) |

| No genetic testing | 11 (10.1) |

| I don't know | 4 (3.7) |

| Functional ability, n (%) | |

| No symptoms | 4 (3.7) |

| No significant disability | 26 (23.8) |

| Slight disability | 32 (29.4) |

| Moderate disability | 29 (26.6) |

| Moderately severe disability | 18 (16.5) |

| Ever received bone marrow or stem cell transplant?, n (%) | |

| Yes | 5 (4.6) |

| No | 104 (95.4) |

| Current treatments, n (%)a | |

| Hormone replacement, steroid medications, or corticosteroids | 34 (31.2) |

| High dose antioxidants (OTC) | 4 (3.7) |

| Lorenzo's oil | 2 (1.8) |

| Spasticity-reducing medications (Baclofen, Tazanidine, Botox, etc.) | 33 (30.3) |

| Neuropathic pain medications or anti-epileptic medications (Neurontin e.g. Gabapentin) | 32 (29.4) |

| Medications for overactive bladder or bowel | 21 (19.3) |

| Cannabidiol (CBD) | 15 (13.8) |

| Anti-depressants or anti-anxiety medications | 24 (22.0) |

| Physical therapy | 32 (29.4) |

| None | 20 (18.4) |

Multiple-choice options that were not selected by any participant have been omitted for conciseness

Percents have been normalized for missing responses

aPercents may not add up to 100% because some individuals receive multiple treatments

Fig. 1.

Overview of study activities to identify symptoms of importance to individuals with ALD

Prevalence of symptomatic themes and symptoms

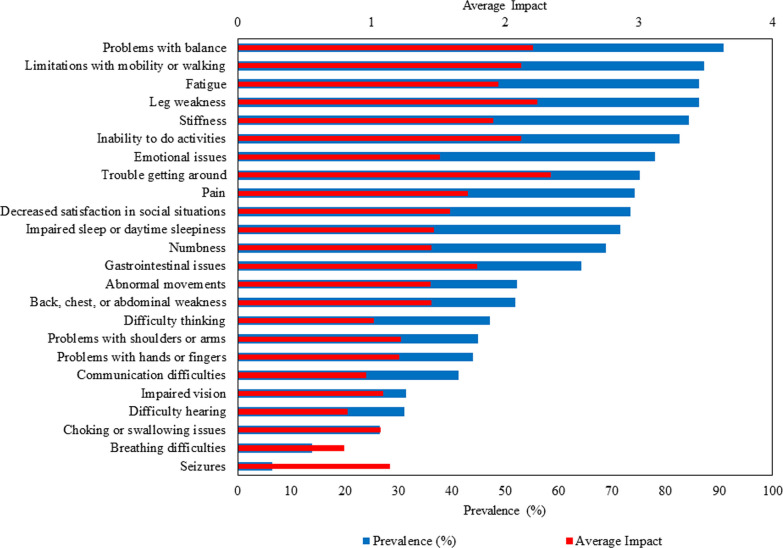

Of the 24 symptomatic themes assessed in the cross-sectional survey, the most prevalent ones in our sample cohort were problems with balance (90.8%), limitations with mobility or walking (87.2%), fatigue (86.2%), and leg weakness (86.2%). The most frequently occurring individual symptoms were fear of disease progression (91.8%), difficulty getting up from the floor or ground (90.1%), difficulty running (89.6%), and fatigue after physical activity (89.1%). Additional file 1: Table S1 provides the prevalence of all symptomatic themes and symptoms.

Life impact of symptomatic themes and symptoms

The symptomatic themes with the highest average impact scores (on a scale of 0–4) from the cross-sectional survey were trouble getting around (2.34), leg weakness (2.24), problems with balance (2.21), inability to do activities (2.12), and limitations with mobility or walking (2.12). The most impactful individual symptoms were difficulty playing sports (3.06), difficulty running (2.94), difficulty riding a bike (2.89), and difficulty dancing (2.82). Additional file 1: Table S1 provides the average impact of all symptomatic themes and symptoms.

The prevalence and average impact of the 24 symptomatic themes that were asked about in the cross-sectional survey are shown in Fig. 2. Blue bars indicate prevalence (%), and red bars indicate average impact.

Fig. 2.

Prevalence and mean impact of symptomatic themes from ALD cross-sectional study

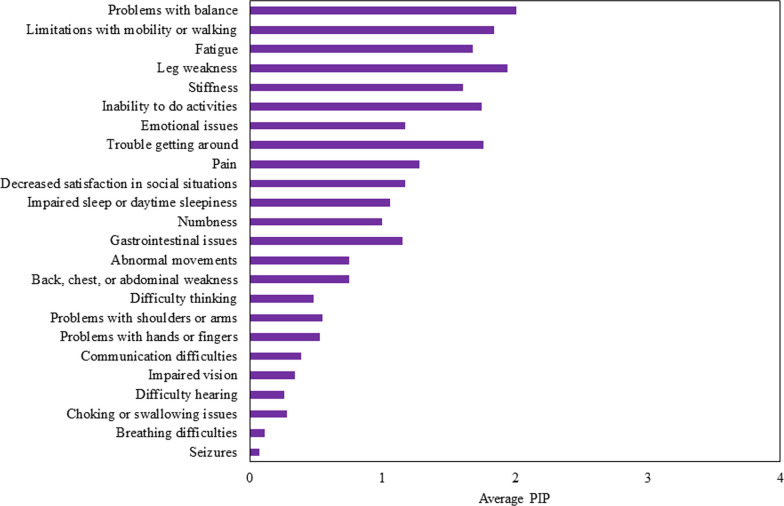

Population impact (PIP) of symptomatic themes and symptoms

The symptomatic themes with the largest PIP scores were problems with balance (2.01), leg weakness (1.94), limitations with mobility or walking (1.84), and trouble getting around (1.76). Difficulty running (2.63), difficulty playing sports (2.59), difficulty riding a bike (2.29), and fear of disease progression (2.21) were the individual symptoms with the highest PIP. The PIP values for the 24 symptomatic themes are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Population impact (PIP) of symptomatic themes from ALD cross-sectional study

Analysis of symptomatic themes by demographic category

The prevalence of several symptomatic themes differed by demographic and clinical subgroups, as displayed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Prevalence of symptomatic themes in ALD for the overall sample (n = 109) and subgroups of individuals with ALD

| Overall prevalence (%) of full sample (n = 109) | |

|---|---|

| A: Theme | |

| Limitations with mobility or walking | 87.2 |

| Problems with balance | 90.8 |

| Inability to do activities | 82.6 |

| Trouble getting around | 75.2 |

| Leg weakness | 86.2 |

| Pain | 74.3 |

| Stiffness | 84.4 |

| Fatigue | 86.2 |

| Gastrointestinal issues | 64.2 |

| Decreased satisfaction in social situations | 73.4 |

| Emotional issues | 78.0 |

| Communication difficulties | 41.3 |

| Difficulty thinking | 47.2 |

| Impaired sleep or daytime sleepiness | 71.6 |

| Back, chest, or abdominal weakness | 51.9 |

| Problems with shoulders or arms | 45.0 |

| Numbness | 68.8 |

| Choking or swallowing issues | 26.6 |

| Abnormal movements | 52.3 |

| Problems with hands or fingers | 44.0 |

| Breathing difficulties | 13.9 |

| Seizures | 6.5 |

| Impaired vision | 31.5 |

| Difficulty hearing | 31.2 |

| Age (years) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (%) | |||

| Above mean (> 51 years) (n = 61) | Equal to or below mean (≤ 51 years) (n = 48) | p value | |

| B: Theme | |||

| Limitations with mobility or walking | 95.08 | 77.08 | 0.0080* |

| Problems with balance | 96.72 | 83.33 | 0.0209* |

| Inability to do activities | 86.89 | 77.08 | 0.2098 |

| Trouble getting around | 80.33 | 68.75 | 0.1855 |

| Leg weakness | 90.16 | 81.25 | 0.2627 |

| Pain | 81.97 | 64.58 | 0.0482* |

| Stiffness | 90.16 | 77.08 | 0.0695 |

| Fatigue | 88.52 | 83.33 | 0.5769 |

| Gastrointestinal issues | 67.21 | 60.42 | 0.5471 |

| Decreased satisfaction in social situations | 70.49 | 77.08 | 0.5155 |

| Emotional issues | 73.77 | 83.33 | 0.2544 |

| Communication difficulties | 39.34 | 43.75 | 0.6975 |

| Difficulty thinking | 50.00 | 43.75 | 0.5642 |

| Impaired sleep or daytime sleepiness | 75.41 | 66.67 | 0.3933 |

| Back, chest, or abdominal weakness | 48.33 | 56.25 | 0.4436 |

| Problems with shoulders or arms | 50.82 | 37.50 | 0.1802 |

| Numbness | 70.49 | 66.67 | 0.6827 |

| Choking or swallowing issues | 29.51 | 22.92 | 0.5155 |

| Abnormal movements | 55.74 | 47.92 | 0.4453 |

| Problems with hands or fingers | 50.82 | 35.42 | 0.1233 |

| Breathing difficulties | 16.67 | 10.42 | 0.4113 |

| Seizures | 5.00 | 8.33 | 0.6975 |

| Impaired vision | 31.67 | 31.25 | 1.0000 |

| Difficulty hearing | 40.98 | 18.75 | 0.0212* |

| Sex | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (%) | |||

| Male (n = 47) | Female (n = 62) | p value | |

| C: Theme | |||

| Limitations with mobility or walking | 91.49 | 83.87 | 0.2660 |

| Problems with balance | 93.62 | 88.71 | 0.5100 |

| Inability to do activities | 93.62 | 74.19 | 0.0100* |

| Trouble getting around | 91.49 | 62.9 | 0.0006* |

| Leg weakness | 93.62 | 80.65 | 0.0896 |

| Pain | 72.34 | 75.81 | 0.8252 |

| Stiffness | 89.36 | 80.65 | 0.2889 |

| Fatigue | 87.23 | 85.48 | 1.0000 |

| Gastrointestinal issues | 63.83 | 64.52 | 1.0000 |

| Decreased satisfaction in social situations | 80.85 | 67.74 | 0.1887 |

| Emotional issues | 80.85 | 75.81 | 0.6425 |

| Communication difficulties | 46.81 | 37.10 | 0.3319 |

| Difficulty thinking | 48.94 | 45.90 | 0.8464 |

| Impaired sleep or daytime sleepiness | 65.96 | 75.81 | 0.2891 |

| Back, chest, or abdominal weakness | 59.57 | 45.90 | 0.1782 |

| Problems with shoulders or arms | 40.43 | 48.39 | 0.4419 |

| Numbness | 74.47 | 64.52 | 0.3019 |

| Choking or swallowing issues | 14.89 | 35.48 | 0.0174* |

| Abnormal movements | 61.70 | 45.16 | 0.1212 |

| Problems with hands or fingers | 36.17 | 50.00 | 0.1755 |

| Breathing difficulties | 10.64 | 16.39 | 0.5759 |

| Seizures | 12.77 | 1.64 | 0.0414* |

| Impaired vision | 25.53 | 36.07 | 0.2981 |

| Difficulty hearing | 25.53 | 35.48 | 0.3019 |

| Education level | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (%) | |||

| High school, Technical school, none (n = 52) | College, Masters, Doctorate (n = 57) | p value | |

| D: Theme | |||

| Limitations with mobility or walking | 88.46 | 85.96 | 0.7794 |

| Problems with balance | 94.23 | 87.72 | 0.3257 |

| Inability to do activities | 88.46 | 77.19 | 0.1375 |

| Trouble getting around | 80.77 | 70.18 | 0.2674 |

| Leg weakness | 88.46 | 84.21 | 0.5864 |

| Pain | 82.69 | 66.67 | 0.0787 |

| Stiffness | 86.54 | 82.46 | 0.6063 |

| Fatigue | 94.23 | 78.95 | 0.0261* |

| Gastrointestinal issues | 61.54 | 66.67 | 0.6896 |

| Decreased satisfaction in social situations | 78.85 | 68.42 | 0.2792 |

| Emotional issues | 76.92 | 78.95 | 0.821 |

| Communication difficulties | 40.38 | 42.11 | 1 |

| Difficulty thinking | 47.06 | 47.37 | 1 |

| Impaired sleep or daytime sleepiness | 78.85 | 64.91 | 0.1378 |

| Back, chest, or abdominal weakness | 56.86 | 47.37 | 0.342 |

| Problems with shoulders or arms | 55.77 | 35.09 | 0.0354* |

| Numbness | 63.46 | 73.68 | 0.3026 |

| Choking or swallowing issues | 30.77 | 22.81 | 0.3904 |

| Abnormal movements | 59.62 | 45.61 | 0.18 |

| Problems with hands or fingers | 51.92 | 36.84 | 0.1263 |

| Breathing difficulties | 15.69 | 12.28 | 0.7815 |

| Seizures | 5.88 | 7.02 | 1 |

| Impaired vision | 37.25 | 26.32 | 0.2996 |

| Difficulty hearing | 36.54 | 26.32 | 0.3026 |

| Employment status | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (%) | |||

| Not working (n = 24) | Working (n = 85) | p value | |

| E: Theme | |||

| Limitations with mobility or walking | 95.83 | 84.71 | 0.2968 |

| Problems with balance | 100.00 | 88.24 | 0.1134 |

| Inability to do activities | 87.50 | 81.18 | 0.5586 |

| Trouble getting around | 87.50 | 71.76 | 0.1794 |

| Leg weakness | 87.50 | 85.88 | 1.0000 |

| Pain | 95.83 | 68.24 | 0.0068* |

| Stiffness | 95.83 | 81.18 | 0.1124 |

| Fatigue | 100.00 | 82.35 | 0.0383* |

| Gastrointestinal issues | 66.67 | 63.53 | 0.8149 |

| Decreased satisfaction in social situations | 79.17 | 71.76 | 0.6040 |

| Emotional issues | 100.00 | 71.76 | 0.0016* |

| Communication difficulties | 58.33 | 36.47 | 0.0638 |

| Difficulty thinking | 60.87 | 43.53 | 0.1628 |

| Impaired sleep or daytime sleepiness | 83.33 | 68.24 | 0.2020 |

| Back, chest, or abdominal weakness | 70.83 | 46.43 | 0.0397* |

| Problems with shoulders or arms | 58.33 | 41.18 | 0.1660 |

| Numbness | 87.50 | 63.53 | 0.0265* |

| Choking or swallowing issues | 29.17 | 25.88 | 0.7957 |

| Abnormal movements | 75.00 | 45.88 | 0.0195* |

| Problems with hands or fingers | 50.00 | 42.35 | 0.6421 |

| Breathing difficulties | 25.00 | 10.71 | 0.0952 |

| Seizures | 8.33 | 5.95 | 0.6501 |

| Impaired vision | 33.33 | 30.95 | 0.8084 |

| Difficulty hearing | 16.67 | 35.29 | 0.1328 |

| Disability status | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (%) | |||

| On disability (n = 16) | Not on disability (n = 93) | p value | |

| F: Theme | |||

| Limitations with mobility or walking | 100.00 | 84.95 | 0.2163 |

| Problems with balance | 100.00 | 89.25 | 0.3524 |

| Inability to do activities | 87.50 | 81.72 | 0.7331 |

| Trouble getting around | 87.50 | 73.12 | 0.3481 |

| Leg weakness | 87.50 | 86.02 | 1.0000 |

| Pain | 93.75 | 70.97 | 0.0655 |

| Stiffness | 100.00 | 81.72 | 0.0711 |

| Fatigue | 100.00 | 83.87 | 0.1205 |

| Gastrointestinal issues | 62.50 | 64.52 | 1.0000 |

| Decreased satisfaction in social situations | 75.00 | 73.12 | 1.0000 |

| Emotional issues | 100.00 | 74.19 | 0.0204* |

| Communication difficulties | 68.75 | 36.56 | 0.0258* |

| Difficulty thinking | 53.33 | 46.24 | 0.7815 |

| Impaired sleep or daytime sleepiness | 81.25 | 69.89 | 0.5494 |

| Back, chest, or abdominal weakness | 62.50 | 50.00 | 0.4232 |

| Problems with shoulders or arms | 56.25 | 43.01 | 0.4170 |

| Numbness | 81.25 | 66.67 | 0.3816 |

| Choking or swallowing issues | 43.75 | 23.66 | 0.1248 |

| Abnormal movements | 68.75 | 49.46 | 0.1832 |

| Problems with hands or fingers | 50.00 | 43.01 | 0.7860 |

| Breathing difficulties | 25.00 | 11.96 | 0.2318 |

| Seizures | 12.50 | 5.43 | 0.2766 |

| Impaired vision | 31.25 | 31.52 | 1.0000 |

| Difficulty hearing | 18.75 | 33.33 | 0.3816 |

| Has ALD impacted your employment status or choice? | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (%) | |||

| Yes (n = 60) | No (n = 40) | p value | |

| G: Theme | |||

| Limitations with mobility or walking | 93.33 | 77.50 | 0.0321* |

| Problems with balance | 95.00 | 85.00 | 0.1505 |

| Inability to do activities | 93.33 | 67.50 | 0.0011* |

| Trouble getting around | 88.33 | 60.00 | 0.0015* |

| Leg weakness | 91.67 | 80.00 | 0.1287 |

| Pain | 88.33 | 55.00 | 0.0003* |

| Stiffness | 91.67 | 72.50 | 0.0134* |

| Fatigue | 90.00 | 80.00 | 0.2387 |

| Gastrointestinal issues | 66.67 | 60.00 | 0.5291 |

| Decreased satisfaction in social situations | 85.00 | 55.00 | 0.0013* |

| Emotional issues | 90.00 | 55.00 | < 0.0001* |

| Communication difficulties | 55.00 | 20.00 | 0.0008* |

| Difficulty thinking | 61.02 | 32.50 | 0.0076* |

| Impaired sleep or daytime sleepiness | 80.00 | 55.00 | 0.0135* |

| Back, chest, or abdominal weakness | 64.41 | 32.50 | 0.0022* |

| Problems with shoulders or arms | 55.00 | 25.00 | 0.0039* |

| Numbness | 80.00 | 52.50 | 0.0045* |

| Choking or swallowing issues | 31.67 | 17.50 | 0.1625 |

| Abnormal movements | 68.33 | 27.50 | < 0.0001* |

| Problems with hands or fingers | 51.67 | 32.50 | 0.0672 |

| Breathing difficulties | 16.95 | 2.50 | 0.0461* |

| Seizures | 10.17 | 2.50 | 0.2361 |

| Impaired vision | 35.59 | 22.50 | 0.1874 |

| Difficulty hearing | 30.00 | 35.00 | 0.6642 |

| Years since first noticed symptoms | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (%) | |||

| Above mean (> 15 years) (n = 51) | Equal to or below mean (≤ 15 years) (n = 57) | p value | |

| H: Theme | |||

| Limitations with mobility or walking | 92.16 | 84.21 | 0.2468 |

| Problems with balance | 94.12 | 89.47 | 0.4953 |

| Inability to do activities | 86.27 | 78.95 | 0.4485 |

| Trouble getting around | 86.27 | 66.67 | 0.0237* |

| Leg weakness | 88.24 | 84.21 | 0.5893 |

| Pain | 82.35 | 66.67 | 0.0797 |

| Stiffness | 90.20 | 78.95 | 0.1220 |

| Fatigue | 90.20 | 82.46 | 0.2782 |

| Gastrointestinal issues | 70.59 | 57.89 | 0.2287 |

| Decreased satisfaction in social situations | 76.47 | 70.18 | 0.5185 |

| Emotional issues | 78.43 | 77.19 | 1.0000 |

| Communication difficulties | 50.98 | 33.33 | 0.0794 |

| Difficulty thinking | 54.00 | 42.11 | 0.2483 |

| Impaired sleep or daytime sleepiness | 76.47 | 68.42 | 0.3948 |

| Back, chest, or abdominal weakness | 62.00 | 42.11 | 0.0528 |

| Problems with shoulders or arms | 58.82 | 31.58 | 0.0065* |

| Numbness | 74.51 | 64.91 | 0.3030 |

| Choking or swallowing issues | 37.25 | 17.54 | 0.0293* |

| Abnormal movements | 64.71 | 42.11 | 0.0217* |

| Problems with hands or fingers | 56.86 | 31.58 | 0.0114* |

| Breathing difficulties | 26.00 | 3.51 | 0.0014* |

| Seizures | 8.00 | 5.26 | 0.7031 |

| Impaired vision | 30.00 | 31.58 | 1.0000 |

| Difficulty hearing | 39.22 | 24.56 | 0.1459 |

| Diagnosed with AMN? | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (%) | |||

| Yes (n = 71) | No (n = 27) | p value | |

| I: Theme | |||

| Limitations with mobility or walking | 94.37 | 70.37 | 0.0030* |

| Problems with balance | 95.77 | 85.19 | 0.0886 |

| Inability to do activities | 88.73 | 66.67 | 0.0161* |

| Trouble getting around | 81.69 | 62.96 | 0.1974 |

| Leg weakness | 91.55 | 77.78 | 0.0852 |

| Pain | 81.69 | 59.26 | 0.0339* |

| Stiffness | 92.96 | 70.37 | 0.0063* |

| Fatigue | 87.32 | 85.19 | 0.7487 |

| Gastrointestinal issues | 70.42 | 51.85 | 0.1000 |

| Decreased satisfaction in social situations | 76.06 | 62.96 | 0.2135 |

| Emotional issues | 78.87 | 77.78 | 1.0000 |

| Communication difficulties | 45.07 | 29.63 | 0.1779 |

| Difficulty thinking | 50.00 | 37.04 | 0.2673 |

| Impaired sleep or daytime sleepiness | 71.83 | 70.37 | 1.0000 |

| Back, chest, or abdominal weakness | 52.11 | 51.85 | 1.0000 |

| Problems with shoulders or arms | 46.68 | 37.04 | 0.4962 |

| Numbness | 76.06 | 44.44 | 0.0041* |

| Choking or swallowing issues | 25.35 | 25.93 | 1.0000 |

| Abnormal movements | 57.75 | 44.44 | 0.2638 |

| Problems with hands or fingers | 45.07 | 33.33 | 0.3621 |

| Breathing difficulties | 14.08 | 11.11 | 1.0000 |

| Seizures | 5.63 | 3.70 | 1.0000 |

| Impaired vision | 21.13 | 44.44 | 0.0409 |

| Difficulty hearing | 25.35 | 40.74 | 0.1462 |

| Diagnosed with cerebral ALD? | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (%) | |||

| Yes (n = 18) | No (n = 81) | p value | |

| J: Theme | |||

| Limitations with your mobility or walking | 83.33 | 86.42 | 0.7152 |

| Problems with balance | 77.78 | 92.59 | 0.0800 |

| Inability to do activities | 88.89 | 80.25 | 0.5138 |

| Trouble getting around | 77.78 | 74.07 | 1.0000 |

| Leg weakness | 77.78 | 86.42 | 0.4653 |

| Pain | 66.67 | 76.54 | 0.3826 |

| Stiffness | 77.78 | 86.42 | 0.4653 |

| Fatigue | 83.33 | 86.42 | 0.7152 |

| Gastrointestinal issues | 66.67 | 62.96 | 1.0000 |

| Decreased satisfaction in social situations | 83.33 | 72.94 | 0.5495 |

| Emotional issues | 88.89 | 77.78 | 0.5158 |

| Communication difficulties | 50 | 37.04 | 0.4243 |

| Difficulty thinking | 50 | 46.25 | 0.7994 |

| Impaired sleep or daytime sleepiness | 66.67 | 71.6 | 0.7758 |

| Back, chest, or abdominal weakness | 55.56 | 48.75 | 0.7948 |

| Problems with shoulders or arms | 50 | 41.98 | 0.6038 |

| Numbness | 72.22 | 67.9 | 0.7868 |

| Choking or swallowing issues | 22.22 | 27.16 | 0.7743 |

| Abnormal movements | 66.67 | 50.62 | 0.2975 |

| Problems with hands or fingers | 44.44 | 44.44 | 1 |

| Breathing difficulties | 16.67 | 11.25 | 0.6899 |

| Seizures | 11.11 | 6.25 | 0.609 |

| Impaired vision | 38.89 | 26.25 | 0.3861 |

| Difficulty hearing | 22.22 | 30.86 | 0.5748 |

| Diagnosed with Addison's disease (adrenal insufficiency)? | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (%) | |||

| Yes (n = 35) | No (n = 71) | p value | |

| K: Theme | |||

| Limitations with mobility or walking | 88.57 | 85.92 | 1.0000 |

| Problems with balance | 94.29 | 88.73 | 0.4913 |

| Inability to do activities | 91.43 | 77.46 | 0.1068 |

| Trouble getting around | 91.43 | 66.20 | 0.0046* |

| Leg weakness | 91.43 | 83.10 | 0.3756 |

| Pain | 68.57 | 76.06 | 0.4841 |

| Stiffness | 85.71 | 83.10 | 1.0000 |

| Fatigue | 88.57 | 84.51 | 0.7688 |

| Gastrointestinal issues | 62.86 | 64.79 | 1.0000 |

| Decreased satisfaction in social situations | 77.14 | 70.42 | 0.4984 |

| Emotional issues | 80.00 | 76.06 | 0.8061 |

| Communication difficulties | 42.86 | 38.03 | 0.6762 |

| Difficulty thinking | 48.57 | 44.29 | 0.6842 |

| Impaired sleep or daytime sleepiness | 65.71 | 73.24 | 0.4975 |

| Back, chest, or abdominal weakness | 57.14 | 49.30 | 0.5365 |

| Problems with shoulders or arms | 28.57 | 50.70 | 0.0379* |

| Numbness | 77.14 | 64.79 | 0.2655 |

| Choking or swallowing issues | 17.14 | 30.99 | 0.1626 |

| Abnormal movements | 65.71 | 45.07 | 0.0627 |

| Problems with hands or fingers | 40.00 | 46.48 | 0.5419 |

| Breathing difficulties | 14.29 | 14.08 | 1.0000 |

| Seizures | 14.29 | 2.82 | 0.0381* |

| Impaired vision | 31.43 | 32.39 | 1.0000 |

| Difficulty hearing | 28.57 | 32.39 | 0.8243 |

| Ambulatory status | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (%) | |||

| Mobility assistance needed (n = 59) | Walk independently (n = 50) | p value | |

| L: Theme | |||

| Limitations with mobility or walking | 98.31 | 74.00 | 0.0002* |

| Problems with balance | 100.00 | 80.00 | 0.0002* |

| Inability to do activities | 100.00 | 62.00 | < 0.0001* |

| Trouble getting around | 98.31 | 48.00 | < 0.0001* |

| Leg weakness | 96.61 | 74.00 | 0.0007* |

| Pain | 81.36 | 66.00 | 0.0808 |

| Stiffness | 93.22 | 74.00 | 0.0077* |

| Fatigue | 91.53 | 80.00 | 0.0991 |

| Gastrointestinal issues | 64.41 | 64.00 | 1.0000 |

| Decreased satisfaction in social situations | 83.05 | 62.00 | 0.0169* |

| Emotional issues | 81.36 | 74.00 | 0.3661 |

| Communication difficulties | 50.85 | 30.00 | 0.0329* |

| Difficulty thinking | 51.72 | 42.00 | 0.3394 |

| Impaired sleep or daytime sleepiness | 74.58 | 68.00 | 0.5247 |

| Back, chest, or abdominal weakness | 63.79 | 38.00 | 0.0117* |

| Problems with shoulders or arms | 49.15 | 40.00 | 0.4398 |

| Numbness | 74.58 | 62.00 | 0.2132 |

| Choking or swallowing issues | 32.20 | 20.00 | 0.1932 |

| Abnormal movements | 62.71 | 40.00 | 0.0217* |

| Problems with hands or fingers | 42.37 | 46.00 | 0.8466 |

| Breathing difficulties | 13.79 | 14.00 | 1.0000 |

| Seizures | 10.34 | 2.00 | 0.1200 |

| Impaired vision | 34.48 | 28.00 | 0.5360 |

| Difficulty hearing | 33.90 | 28.00 | 0.5401 |

| Speech status | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (%) | |||

| Speech change (n = 20) | Talks clearly (n = 89) | p value | |

| M: Theme | |||

| Limitations with mobility or walking | 100.00 | 84.27 | 0.0685 |

| Problems with balance | 100.00 | 88.76 | 0.2028 |

| Inability to do activities | 95.00 | 79.78 | 0.1883 |

| Trouble getting around | 100.00 | 69.66 | 0.0030* |

| Leg weakness | 100.00 | 83.15 | 0.0682 |

| Pain | 85.00 | 71.91 | 0.2713 |

| Stiffness | 95.00 | 82.02 | 0.1897 |

| Fatigue | 90.00 | 85.39 | 0.7335 |

| Gastrointestinal issues | 75.00 | 61.80 | 0.3119 |

| Decreased satisfaction in social situations | 95.00 | 68.54 | 0.0222* |

| Emotional issues | 100.00 | 73.03 | 0.0059* |

| Communication difficulties | 100.00 | 28.09 | < 0.0001* |

| Difficulty thinking | 73.68 | 41.57 | 0.0126* |

| Impaired sleep or daytime sleepiness | 95.00 | 66.29 | 0.0117* |

| Back, chest, or abdominal weakness | 78.95 | 46.07 | 0.0113* |

| Problems with shoulders or arms | 75.00 | 38.2 | 0.0052* |

| Numbness | 95.00 | 62.92 | 0.0061* |

| Choking or swallowing issues | 75.00 | 15.73 | < 0.0001* |

| Abnormal movements | 80.00 | 46.07 | 0.0067* |

| Problems with hands or fingers | 75.00 | 37.08 | 0.0026* |

| Breathing difficulties | 42.11 | 7.87 | 0.0007* |

| Seizures | 5.26 | 6.74 | 1.0000 |

| Impaired vision | 47.37 | 28.09 | 0.1110 |

| Difficulty hearing | 35.00 | 30.34 | 0.7903 |

| Functional ability | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (%) | |||

| Slight through severe disability (n = 79) | No symptoms or no significant disability (n = 30) | p value | |

| N: Theme | |||

| Limitations with mobility or walking | 98.73 | 56.67 | < 0.0001* |

| Problems with balance | 97.47 | 73.33 | 0.0005* |

| Inability to do activities | 98.73 | 40.00 | < 0.0001* |

| Trouble getting around | 94.94 | 23.33 | < 0.0001* |

| Leg weakness | 96.2 | 60.00 | < 0.0001* |

| Pain | 84.81 | 46.67 | 0.0001* |

| Stiffness | 92.41 | 63.33 | 0.0005* |

| Fatigue | 93.67 | 66.67 | 0.0008* |

| Gastrointestinal issues | 68.35 | 53.33 | 0.1807 |

| Decreased satisfaction in social situations | 84.81 | 43.33 | < 0.0001* |

| Emotional issues | 83.54 | 63.33 | 0.0367* |

| Communication difficulties | 51.90 | 13.33 | 0.0002* |

| Difficulty thinking | 55.13 | 26.67 | 0.0099* |

| Impaired sleep or daytime sleepiness | 77.22 | 56.67 | 0.0555 |

| Back, chest, or abdominal weakness | 61.54 | 26.67 | 0.0013* |

| Problems with shoulders or arms | 54.43 | 20.00 | 0.0013* |

| Numbness | 77.22 | 46.67 | 0.0048* |

| Choking or swallowing issues | 29.11 | 20.00 | 0.4674 |

| Abnormal movements | 64.56 | 20.00 | < 0.0001* |

| Problems with hands or fingers | 48.10 | 33.33 | 0.1983 |

| Breathing difficulties | 15.38 | 10.00 | 0.5518 |

| Seizures | 8.97 | 0.00 | 0.1866 |

| Impaired vision | 34.62 | 23.33 | 0.3556 |

| Difficulty hearing | 30.38 | 33.33 | 0.8187 |

| Home health aide per week | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (%) | |||

| Receive aide (n = 34) | None (n = 75) | p value | |

| O: Theme | |||

| Limitations with mobility or walking | 100.00 | 81.33 | 0.0046* |

| Problems with balance | 100.00 | 86.67 | 0.0292* |

| Inability to do activities | 100.00 | 74.67 | 0.0006* |

| Trouble getting around | 100.00 | 64.00 | < 0.0001* |

| Leg weakness | 94.12 | 82.67 | 0.1395 |

| Pain | 82.35 | 70.67 | 0.2414 |

| Stiffness | 97.06 | 78.67 | 0.0199* |

| Fatigue | 97.06 | 81.33 | 0.0340* |

| Gastrointestinal issues | 70.59 | 61.33 | 0.3947 |

| Decreased satisfaction in social situations | 88.24 | 66.67 | 0.0199* |

| Emotional issues | 91.18 | 72.00 | 0.0265* |

| Communication difficulties | 52.94 | 36.00 | 0.1410 |

| Difficulty thinking | 52.94 | 44.59 | 0.5340 |

| Impaired sleep or daytime sleepiness | 79.41 | 68.00 | 0.2585 |

| Back, chest, or abdominal weakness | 72.73 | 42.67 | 0.0062* |

| Problems with shoulders or arms | 61.76 | 37.33 | 0.0226* |

| Numbness | 76.47 | 65.33 | 0.2733 |

| Choking or swallowing issues | 38.24 | 21.33 | 0.1001 |

| Abnormal movements | 76.47 | 41.33 | 0.0008* |

| Problems with hands or fingers | 55.88 | 38.67 | 0.1014 |

| Breathing difficulties | 18.18 | 12.00 | 0.3837 |

| Seizures | 18.18 | 1.33 | 0.0031* |

| Impaired vision | 33.33 | 30.67 | 0.8241 |

| Difficulty hearing | 38.24 | 28.00 | 0.3723 |

*Values of p < 0.05 are marked by an asterisk, and values of statistical significance, by the Benjamini–Hochberg method, are bolded

Individuals who reported having anywhere from a slight to severe disability, compared to no symptoms or no significant disability, showed higher prevalence of 14 symptomatic themes; the most significant differences (p < 0.0001) were in limitations with mobility or walking (99% vs. 57%), inability to do activities (99% vs. 40%), trouble getting around (95% vs. 23%), leg weakness (96% vs. 60%), decreased satisfaction in social situations (85% vs. 43%), and abnormal movements (65% vs. 20%). Functional ability was the single most closely associated clinical feature with symptomatic theme prevalence.

Similarly, considering speech status, those who indicated experiencing a change in their speech had greater frequency in 9 symptomatic themes; the largest differences (p < 0.0001) were related to communication difficulties (100% vs. 28% reported) and choking or swallowing issues (75% vs. 16% reported). In terms of ambulatory status, individuals requiring mobility assistance reported higher prevalence in 6 of the 24 symptomatic themes; the leading differences (p < 0.0001) were related to inability to do activities (100% vs. 62% reported) and trouble getting around (98% vs. 48% reported). Receiving home health aide was also highly associated with greater symptomatic theme prevalence in 6 areas, with the most significant difference (p < 0.0001) in trouble getting around (100% vs. 64% reported).

Unemployed participants displayed a higher frequency of pain and emotional issues compared to employed participants. When participants were asked if ALD/AMN impacted their employment status or choice, the subgroup of individuals who responded “yes” showed higher prevalence in 11 of the 24 symptomatic themes; the most significant differences (p < 0.0001) were in emotional issues (90% vs. 55% reported) and abnormal movements (68% vs. 28% reported).

Participants who had been experiencing symptoms related to ALD for above the mean duration of 15 years reported a higher frequency in problems with shoulders or arms and breathing difficulties. Individuals who were diagnosed with AMN reported a higher prevalence of limitations with mobility or walking, stiffness, and numbness. Individuals who were diagnosed with Addison’s disease experienced a higher frequency of trouble getting around.

Participants older than the mean age of 51 years experienced a higher prevalence of limitations with mobility or walking, compared to participants at or below the mean age. Men experienced trouble getting around at a higher rate than women. There were no significant associations between symptomatic theme prevalence and education level, disability status, or diagnosis with cerebral ALD.

Discussion

This research provides a novel data set and analysis regarding symptomatic disease in ALD, thereby adding to existing knowledge of ALD and its core clinical manifestations. This information can be used by researchers, therapeutic developers, clinicians, and patients who seek to better understand ALD (and all of the phenotypes) from the patient’s point of view. In this study, qualitative interviews were conducted, in which individuals with ALD identified numerous problematic symptoms that affect their lives. The subsequent cross-sectional study, with a large, international cohort of adults with ALD determined the prevalence and impact of these symptoms and themes.

In ALD, the symptomatic themes with the highest prevalence were also those with the highest relative impact: problems with balance, limitations with mobility or walking, and leg weakness. The overlap of most prevalent issues with issues that are most impactful is seen in some, but not all, diseases [20, 25–27]. Moreover, the importance of these themes in ALD corroborates existing literature [29, 30]. Raymond et al. [29] report the symptom set that affects 40–45% of individuals with ALD (specifically, AMN) to include progressive stiffness and weakness in the legs, and Percy and Rutledge [30] report that boys with ALD (specifically, cerebral ALD) typically present with neurological deterioration that includes development of quadriparesis. In our cross-sectional study, we observed that 54.1% of respondents used some kind of ambulation assistance (cane, crutches, walker, wheelchair, or motorized scooter), and that 84.4% and 86.2% of respondents had stiffness and leg weakness, respectively.

Furthermore, Winkelman et al. [31] show, through diagnositic phone interviews with 32 patients and chart reviews, that progressive gait and balance problems, leg discomfort, pain, and sleep disturbances (related to restless leg syndrome) are highly prevalent and interconnected in adults with ALD. Indeed, we found 90.8% of participants had problems with balance, 74.3% had pain, 71.6% had impaired sleep or daytime sleepiness, and 74.1% had restless legs. Corre et al. [32] present that, in addition to gait and balance issues, bladder and bowel issues are very common in adults with ALD; in their cross-sectional study of 109 adults with ALD, 76.9% of participants had experienced at least one bladder symptom, and 67.3% had experienced at least one bowel symptom. In our study, 86.1% of participants reported trouble with bladder control, and 66.3% reported trouble with bowel control.

Subgroup analysis provides insight into how specific symptomatic themes differ in prevalence based on the characteristics of individuals with ALD; these are general associations and do not indicate a causal relationship. Female participants with ALD (specifically, AMN) communicated trouble getting around at a lower frequency than male participants. The fact that only up to 80% of females develop any kind of symptoms related to ALD during their lifetimes and most of those who do get symptoms experience them after the age of 40–60 years, with the clinical course being less severe, likely explains the lower prevalence of symptoms when compared to men [33, 34]. Participants above the mean age of 51 years showed greater frequency in problems related to mobility and walking. This worsening of physical symptoms related to the spinal cord and peripheral nerves, particularly motor disability of the lower limbs, spasticity, and pain, as individuals get older is consistent with the clinical classification and prognosis of ALD (specifically, AMN) as a progressive disorder [9, 29, 30, 35].

In the analysis of those who identified as having AMN (as opposed to those without AMN), three symptomatic themes were found to be more common: limitations with mobility or walking, stiffness, and numbness. Indeed, these are hallmark symptom areas of AMN, as confirmed by the literature, and these areas need to be appropriately addressed when caring for patients with this condition. [7, 12] In the examination of those who said they have Addison’s disease (as opposed to those without Addison’s disease), one symptomatic theme was found to be more recurrent: trouble getting around. This may relate to the fatigue and muscle weakness that are recognized as cardinal signs of this condition [17]. In the investigation of those with the cerebral form of ALD, we did not find any significant differences in symptomatic theme prevalence, despite the literature denoting cognitive and behavioral impairements, vision problems, and seizures as more common in this cohort [13]. The difference in findings may be attributed to the small sample of patients with cerebral ALD in our study, such that statistical changes could not be detected.

Interestingly and as shown in several other studies with similar methodology to ours, employment status, especially change in employment, had a significant association with symptomatic theme prevalence [19, 20, 22–27]. In our cross-sectional study cohort, not working was associated with higher frequency of 2 symptomatic themes, and a change in employment status or choice due to ALD was associated with higher symptomatic burden in 11 areas. As effective therapies are developed for ALD, it is possible that these therapies will not only reduce individual patient burden but also allow for more open, productive, and meaningful employment opportunities.

We found that the prevalence of two symptomatic themes was associated with a longer time since the onset of symptoms: problems with shoulders or arms and breathing difficulties. In the clinical setting, these two symptomatic themes should be monitored for progression and may be worthy targets for therapeutic interventions [29, 30, 35].

Some of the most widespread differences in symptomatic theme prevalence were seen in those who reported functional disability, those who had speech changes, those who required mobility assistance, and those who received home health aide. The etiology behind the interconnectedness between these concepts and patient-reported symptomatic burden is worth further exploration during future studies.

We acknowledge that there are limitations to this research. The large cohort of individuals with ALD who participated in the cross-sectional study is not a perfect representation of the larger ALD patient population. Although more than 100 adults with all phenotypes of ALD provided data, these participants were limited to those enrolled in one of the national or international registries used for recruitment. In addition, participants self-reported their diagnoses in this study, and these diagnoses were not verified by the registries or by the researchers. Although AMN, cerebral ALD, Addison’s disease, and asymptomatic women with ALS are all considered subsets of ALD, some participants may have misinterpreted their condition. For example, some participants may have had AMN but considered themselves to have ALD only (without AMN) if that was the term commonly used by their physician; or vice versa, some participants may have had AMN and thought of themselves to have AMN only (and not ALD) if they were unfamiliar with the classification of AMN as a subtype of ALD.

Study participants could have differed from the broader ALD patient population in that they represented those with moderate disease burden; asymptomatic individuals or those with very severe symptoms may not have had the willingness or capability to engage in this study. Relatedly, the inclusion of some asymptomatic women with ALD may have diluted the average symptomatic burden found in women overall [34], and the inclusion of younger individuals (more of whom would be asymptomatic or presymptomatic) may have lessened the overall disease burden reported for the entire sample [9].

Our study cohort also included a high percent of participants who identified as white (89.9%) and non-Hispanic (86.2%), and far fewer from minority races and ethnicities. The lack of minority participation in research is a longstanding challenge but one that our clinical research team and organization are working to address through continued and more diversified outreach in the community.

Our recruitment and cross-sectional survey study were conducted primarily online, so individuals without email or access to the internet were also probably underrepresented. Nevertheless, the results from our study do likely reflect the responses for the section of the ALD population that is likely to seek care and participate in research and clinical trials in the future.

Conclusions

This research significantly adds to existing literature that explores the unique symptoms and co-morbidities of adult patients of both sexes living with any phenotypic variant of ALD, encompassing AMN, cerebral ALD, Addison’s disease, and asymptomatic women with ALD. This study uses extensive and direct patient input to identify what is most meaningful to patients with ALD overall and differences in the symptoms that are most important to distinct subgroups of patients with ALD. The information presented further highlights the multifactorial nature of ALD, and it has implications for identifying clinically-relevant symptoms to address during clinical care and future therapeutic studies.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Prevalence, average life impact, and population impact (PIP) of symptoms inquired about in ALD cross-sectional study (n = 109).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Eileen Sawyer, Ph.D. (SwanBio Therapeutics) for her thoughtful comments and editing of this manuscript. We would like to acknowledge our recruitment partners at ALD Connect (Kathleen O’Sullivan Fortin, and Kelly Miettunen); the United Leukodystrophy Foundation (Keely Hata and Chris Rice); Alex—The Leukodystrophy Charity (Suzanne Gosney and Sara Hunt); Fundación Lautaro te Necesita—Leukodystrophy Foundation (Verónica de Pablo); The Leukodystrophy Resource Research Organisation (LRRO) (Bob Wyborn); Royal Children’s Hospital and Massimo’s Mission (Eloise Uebergang); and Leukodystrophy Australia (Kylie Agllias). We would also like to express sincere gratitude to all of the patients who contributed to and participated in this research.

Author contributions

AV: investigation; data curation; formal analysis; project administration; visualization; writing—original draft. JW, JS, SR: investigation; data curation; formal analysis; project administration; writing—review and editing. CE, SK, KC: writing—review and editing. ND: software; data curation; formal analysis; writing—review and editing. JH, AP, AW, GB, CB, RG: formal analysis; writing—review and editing. CH: conceptualization; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; formal analysis; project administration; supervision; writing—review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by SwanBio Therapeutics and Autobahn Therapeutics. The sponsors were involved in discussions of patient interviews, in expert selection of symptoms for the cross-sectional study, and in discussion and interpretation of the results from the cross-sectional study. The sponsors, listed as co-authors, assisted in preparation of this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Anonymized data used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All study activities were approved by the University of Rochester Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided informed consent prior to taking part in study activities (interviews and/or cross-sectional study).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

AV does not have any competing interest to declare. JW does not have any competing interest to declare. JS does not have any competing interest to declare. SR does not have any competing interest to declare. CE does not have any competing interest to declare. ND does not have any competing interest to declare. JH does not have any competing interest to declare. SK does not have any competing interest to declare. KC does not have any competing interest to declare. AP, at the time this research was conducted, was an employee of SwanBio Therapeutics. AW, at the time this research was conducted, was an employee of Autobahn Therapeutics. GB is a current employee of Autobahn Therapeutics. CB, at the time this research was conducted, was an employee and stockholder of Autobahn Therapeutics. RG is a current employee of Autobahn Therapeutics. CH receives royalties for the use of multiple disease specific instruments. He has provided consultation to Biogen Idec, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, aTyr Pharma, AMO Pharma, Acceleron Pharma, Cytokinetics, Expansion Therapeutics, Harmony Biosciences, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Astellas Pharmaceuticals, AveXis, Recursion Pharmaceuticals, IRIS Medicine, Inc., Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Scholar Rock, Avidity Biosciences, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, SwanBio Therapeutics, Neurocrine, and the Marigold Foundation. He receives grant support from the Department of Defense, Duchenne UK, Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy, Recursion Pharmaceuticals, SwanBio Therapeutics, Neurocrine Biosciences, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the Muscular Dystrophy Association, the Friedreich’s Ataxia Research Alliance, Cure Spinal Muscular Atrophy, and the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Association. He is the director of the University of Rochester’s Center for Health + Technology.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mosser J, Lutz Y, Stoeckel ME, Sarde CO, Kretz C, Douar AM, et al. The gene responsible for adrenoleukodystrophy encodes a peroxisomal membrane protein. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3(2):265–271. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mosser J, Douar AM, Sarde CO, Kioschis P, Feil R, Moser H, et al. Putative X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy gene shares unexpected homology with ABC transporters. Nature. 1993;361(6414):726–730. doi: 10.1038/361726a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Migeon BR, Moser HW, Moser AB, Axelman J, Sillence D, Norum RA. Adrenoleukodystrophy: evidence for X linkage, inactivation, and selection favoring the mutant allele in heterozygous cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78(8):5066–5070. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.8.5066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holzinger A, Kammerer S, Berger J, Roscher AA. cDNA cloning and mRNA expression of the human adrenoleukodystrophy related protein (ALDRP), a peroxisomal ABC transporter. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;239(1):261–264. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGuinness MC, Lu J, Zhang H, Dong G, Heinzer AK, Watkins PA, et al. Role of ALDP (ABCD1) and mitochondria in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(2):744–753. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.2.744-753.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bezman L, Moser AB, Raymond GV, Rinaldo P, Watkins PA, Smith KD, et al. Adrenoleukodystrophy: incidence, new mutation rate, and results of extended family screening. Ann Neurol. 2001;49(4):512–517. doi: 10.1002/ana.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moser HW, Raymond GV, Dubey P. Adrenoleukodystrophy: new approaches to a neurodegenerative disease. JAMA. 2005;294(24):3131–3134. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.24.3131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berger J, Gärtner J. X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy: clinical, biochemical and pathogenetic aspects. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763(12):1721–1732. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engelen M, Kemp S, de Visser M, van Geel BM, Wanders RJA, Aubourg P, et al. X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy (X-ALD): clinical presentation and guidelines for diagnosis, follow-up and management. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:51. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-7-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engelen M, van Ballegoij WJC, Mallack EJ, Van Haren KP, Köhler W, Salsano E, et al. International recommendations for the diagnosis and management of patients with adrenoleukodystrophy: a consensus-based approach. Neurology. 2022;99(21):940–951. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000201374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moser AB, Jones RO, Hubbard WC, Tortorelli S, Orsini JJ, Caggana M, et al. Newborn screening for X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Int J Neonatal Screen. 2016;2(4):15. doi: 10.3390/ijns2040015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD). Adrenomyeloneuropathy. https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/10614/adrenomyeloneuropathy. Accessed 9 Mar 2023.

- 13.van Geel BM, Bezman L, Loes DJ, Moser HW, Raymond GV. Evolution of phenotypes in adult male patients with X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Ann Neurol. 2001;49(2):186–194. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(20010201)49:2<186::AID-ANA38>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Beer M, Engelen M, van Geel BM. Frequent occurrence of cerebral demyelination in adrenomyeloneuropathy. Neurology. 2014;83(24):2227–2231. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu J, Eichler F, Biffi A, Duncan CN, Williams DA, Majzoub JA. The changing face of adrenoleukodystrophy. Endocr Rev. 2020;41(4):577–593. doi: 10.1210/endrev/bnaa013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huffnagel IC, Laheji FK, Aziz-Bose R, Tritos NA, Marino R, Linthorst GE, et al. The natural history of adrenal insufficiency in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy: an international collaboration. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(1):118–126. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-01307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charmandari E, Nicolaides NC, Chrousos GP. Adrenal insufficiency. Lancet. 2014;383(9935):2152–2167. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61684-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahmood A, Dubey P, Moser HW, Moser A. X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy: therapeutic approaches to distinct phenotypes. Pediatr Transplant. 2005;9(Suppl 7):55–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2005.00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glidden AM, Luebbe EA, Elson MJ, Goldenthal SB, Snyder CW, Zizzi CE, et al. Patient-reported impact of symptoms in Huntington disease: PRISM-HD. Neurology. 2020;94(19):e2045–e2053. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamel J, Johnson N, Tawil R, Martens WB, Dilek N, McDermott MP, et al. Patient-reported symptoms in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (PRISM-FSHD) Neurology. 2019;93(12):e1180–e1192. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heatwole C, Bode R, Johnson N, Quinn C, Martens W, McDermott MP, et al. Patient-reported impact of symptoms in myotonic dystrophy type 1 (PRISM-1) Neurology. 2012;79(4):348–357. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318260cbe6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Varma A, Weinstein J, Seabury J, Rosero S, Wagner E, Zizzi C, et al. Patient-reported impact of symptoms in Crohn’s disease (PRISM-CD) Off J Am Coll Gastroenterol ACG. 2022 doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heatwole C, Johnson N, Bode R, Dekdebrun J, Dilek N, Hilbert JE, et al. Patient-reported impact of symptoms in myotonic dystrophy type 2 (PRISM-2) Neurology. 2015;85(24):2136–2146. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mongiovi P, Dilek N, Garland C, Hunter M, Kissel JT, Luebbe E, et al. Patient reported impact of symptoms in spinal muscular atrophy (PRISM-SMA) Neurology. 2018;91(13):e1206–e1214. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson NE, Heatwole CR, Dilek N, Sowden J, Kirk CA, Shereff D, et al. Quality-of-life in Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease: the patient’s perspective. Neuromuscul Disord NMD. 2014;24(11):1018–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2014.06.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seabury J, Alexandrou D, Dilek N, Cohen B, Heatwole J, Larkindale J, et al. Patient-reported impact of symptoms in Friedreich ataxia. Neurology. 2023;100(8):e808–e821. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000201598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zizzi C, Seabury J, Rosero S, Alexandrou D, Wagner E, Weinstein JS, et al. Patient reported impact of symptoms in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (PRISM-ALS): a national, cross-sectional study. eClinicalMedicine. 2023;55:101768. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. 4. London: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raymond GV, Moser AB, Fatemi A. X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJ, et al (eds) GeneReviews® Seattle (WA). University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. [PubMed]

- 30.Percy AK, Rutledge SL. Adrenoleukodystrophy and related disorders. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2001;7(3):179–189. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winkelman JW, Grant NR, Molay F, Stephen CD, Sadjadi R, Eichler FS. Restless legs syndrome in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Sleep Med. 2022;91:31–34. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2022.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corre CS, Grant N, Sadjadi R, Hayden D, Becker C, Gomery P, et al. Beyond gait and balance: urinary and bowel dysfunction in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s13023-020-01596-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Engelen M, Barbier M, Dijkstra IME, Schür R, de Bie RMA, Verhamme C, et al. X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy in women: a cross-sectional cohort study. Brain. 2014;137(Pt 3):693–706. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schäfer L, Roicke H, Bergner C, Köhler W. Self-reported quality of life in symptomatic and asymptomatic women with X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Brain Behav. 2023;13(3):e2878. doi: 10.1002/brb3.2878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kemp S, Huffnagel IC, Linthorst GE, Wanders RJ, Engelen M. Adrenoleukodystrophy—neuroendocrine pathogenesis and redefinition of natural history. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12(10):606–615. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Prevalence, average life impact, and population impact (PIP) of symptoms inquired about in ALD cross-sectional study (n = 109).

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.