Abstract

Potent antiretroviral therapy can reduce human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in plasma to levels below the limit of detection for up to 2 years, but the extent to which viral replication is suppressed is unknown. To search for ongoing viral replication in 10 patients on combination antiretroviral therapy for up to 1 year, the emergence of genotypic drug resistance across different compartments was studied and correlated with plasma viral RNA levels. In addition, lymph node (LN) mononuclear cells were assayed for the presence of multiply spliced RNA. Population sequencing of HIV-1 pol was done on plasma RNA, peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) RNA, PBMC DNA, LN RNA, LN DNA, and RNA from virus isolated from PBMCs or LNs. A special effort was made to obtain sequences from patients with undetectable plasma RNA, emphasizing the rapidly emerging lamivudine-associated M184V mutation. Furthermore, concordance of drug resistance mutations across compartments was investigated. No evidence for viral replication was found in patients with plasma HIV RNA levels of <20 copies/ml. In contrast, evolving genotypic drug resistance or the presence of multiply spliced RNA provided evidence for low-level replication in subjects with plasma HIV RNA levels between 20 and 400 copies/ml. All patients failing therapy showed multiple drug resistance mutations in different compartments, and multiply spliced RNA was present upon examination. Concordance of nucleotide sequences from different tissue compartments obtained concurrently from individual patients was high: 98% in the protease and 94% in the reverse transcriptase regions. These findings argue that HIV replication differs significantly between patients on potent antiretroviral therapy with low but detectable viral loads and those with undetectable viral loads.

Potent combination antiretroviral therapy can reduce plasma human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) to levels below the limit of detectability for up to 2 years or more (7) and can substantially diminish HIV RNA levels in lymphoid tissue, genital secretions, and cerebrospinal fluid (2, 15, 27). Despite undetectable plasma RNA levels for 2 years, proviral DNA persists in lymph nodes (LN) and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) (27) which still harbor infectious virus that can be detected by enhanced culture techniques (28). Because current therapeutic strategies aim to reduce plasma HIV RNA to low or undetectable levels, it is important to determine the level of in vivo replication reflected by these plasma levels and if selection for drug resistance is occurring.

The extent of ongoing replication in HIV-infected individuals with undetectable plasma HIV RNA levels is difficult to document because of the limited sensitivities and specificities of available methods such as PCR assays and virus isolation and because of the difficulty in sampling extracirculatory compartments where the majority of the virus resides (5, 18). Virus recovered by enhanced in vitro culture techniques may reflect nonexpressed proviral genotypes or archival DNA (24) rather than actively replicating virus (28). Drug resistance mutations in lymphoid tissues from patients with undetectable plasma HIV RNA levels have not been systematically described, and concurrent studies of genotypic drug resistance in lymphoid tissues, PBMC, and plasma treated with potent combination antiretroviral therapy have not yet been reported.

In the present study, we investigated the emergence of genotypic drug resistance in the protease and reverse transcriptase (RT) region of HIV-1 pol from RNA and DNA across different tissue compartments in patients treated with zidovudine, lamivudine, and indinavir for up to 1 year and correlated evolving drug resistance mutations to different plasma HIV RNA levels. To detect evidence of in vivo replication, we analyzed HIV RNA and DNA for the presence of the rapidly selectable 2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thiacytidine (3TC)-associated M184V mutation in the RT of HIV-1 pol (1, 23, 25) and on the presence of multiply spliced HIV RNA from LN mononuclear cells (LNMC), which reflects continued early viral gene expression (6, 12).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

Ten subjects participating in the Merck 035 study (7) (randomized to treatment with indinavir-zidovudine (AZT)-3TC [n = 6], AZT-3TC [n = 3], or indinavir alone [n = 1]) were selected for study. Plasma, PBMC, and inguinal LN biopsies were performed between 36 and 52 weeks after the initiation of treatment with the study drugs. All 10 subjects had been AZT experienced for more than 6 months prior to the 035 study, and some had previously received other nucleoside analogs; however, all were lamivudine and protease inhibitor naive.

RNA and DNA extractions.

Total RNA and DNA were extracted from plasma and LN by the RNA extraction procedure of the Amplicor Monitor assay (Roche Diagnostic Systems, Inc., Branchburg, N.J.) and with the Qiagen (Chatsworth, Calif.) tissue RNeasy and Qiamp tissue kits. RNA extracts were DNase treated and DNA extracts were RNase treated. RNA and DNA extractions from each LN were performed in duplicate as previously described (27).

Generation of target nucleic acid for sequence analysis.

Protocols were adapted from the specifications of the GeneChip manufacturer (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, Calif.). Exact procedures, including protocol modifications, were as follows.

(i) RT-PCR.

The following were used for RT-PCR: 3′ primer 929T7 (5′-ATTTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGATTTCCCCACTAACTTCTGTATGTCA TTGACA-3′) (12.5 pmol), RT (SuperScript II), 5× First Strand Buffer (1×), and 100 mM dithiothreitol (10 mM) (all from Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.); deoxynucleoside triphosphates (0.5 mM each); RNA Guard (36 U) (Pharmacia Biotech, Alameda, Calif.); and tRNA (50 ng/μl). RNA template, primer, and tRNA were heat treated at 72°C for 3 min. The total reaction volume of 31 μl was incubated at 45°C for 60 min before the RT was inactivated at 70°C for 15 min.

(ii) Two-step nested PCR.

First step conditions were as follows. The 5′ outside primer 881, 5′-AATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAGACAGAGCCAACAGCCCCACCA-3′, and 3′ outside primer 929 (see under RT-PCR above) (each at 0.2 pmol/μl) were used. A hot start was employed by incubating the reaction mixes at 94°C for 1 min, and then 30 amplification cycles were performed (95°C for 15 s, 65°C for 30 s, 72°C for 45 s) followed by an incubation at 72°C for 10 min. Second-step conditions were as follows. The 3′ inside primer PRO-RT3′, 5′-GTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCCACTaagcttCTGTATGTCATTGACAGTC CA-3′ (italic type, T7 RNA polymerase promoter sequence; lowercase type, HindIII restriction site), and 5′ inside primer PRO-RT5′, 5′-AATTAACCCTCACTAAAGggatccAGACCAGAGCCAACAGCCCCA-3′ (italic type, T3 RNA polymerase promoter sequence; lowercase type BamHI restriction site) (each at 0.25 pmol/μl) were used. An initial denaturation step at 94°C for 1 min was followed by 35 amplification cycles (95°C for 15 s, 65°C for 40 s, 72°C for 45 s), followed by an incubation at 72°C for 10 min. In both rounds, rTth DNA polymerase (0.04 U/μL), 3.3× XL Buffer (1× and 0.7×, respectively), Mg(OAc)2 (2.5 mM and 1.5 mM, respectively) (all from Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.), and deoxynucleoside triphosphates (0.2 mM each) were used. The total reaction volume was 50 μl for each step, and the cDNA template was 15 μl in the first and 20 μl in the second step. A Gene AMP PCR System 9600 thermocycler (Perkin-Elmer) was used. LN DNA was amplified by nested PCR only. The final amplicon generated was 1,200 bp long. Positive and negative controls were performed for the RT and nested PCRs.

Sequence analysis by high-density oligonucleotide arrays.

The cDNA amplicons were transcribed with T3 and T7 RNA polymerases (Promega Corp., Madison, Wis.) in the presence of fluorescein-labeled aridine-5′-phosphate (Boehringer Mannheim) to generate cRNA. After a fragmentation step, the RNA fragments were hybridized to the PRT 440 sense and antisense chip (Affymetrix), according to the manufacturer’s procedure. The chip was scanned with a confocal laser microscope (Affymetrix). A composite sequence of 1,023 bp of HIV-1 pol was generated by integrating the sense and the antisense chip data by using the Rule algorithm (GeneChip 2.0 software; Affymetrix). This includes the entire protease region (codons 1 to 99) and 726 bp of the RT region (codons 1 to 242).

Sequencing by dideoxynucleotide sequencing.

Dideoxynucleotide sequencing was performed with a DNA sequencer (model 373A Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) according to the recommended conditions for the Applied Biosystems PRISM Dye Terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit with AmpliTaq DNA polymerase FS. Primers used were as follows: Prot 2 (antisense), 5′-TTGGGCCATCCATTCCTGG-3′ (spans the entire protease region); Pol-1 (sense), 5′-GGAAGAAATCTGTTGACTCAGATTGGT-3′ (spans the first 360 to 420 bases of the RT region, including AZT resistance positions 41, 67, and 70); and 156 RT (sense), 5′-CCAGCAATATTCCAAAGTAGCATGACA-3′ (spans 226 bases, including 3TC resistance position 184 and AZT resistance positions 215 and 219).

Comparison of both sequencing methods.

The concordance of base calls for the two methods was 98.8% from clinical samples. Artificial mixing experiments showed a bias towards calling wild-type bases by the GeneChip method (8).

Virus isolation.

LNMC were extracted by grinding a piece of the node through a mesh screen and rinsing with phosphate-buffered saline. 106 LNMC or PBMC were cocultured with 106 uninfected donor PBMC according to standard protocol (11). Supernatants from LNMC cocultures were stored at −70°C until RNA extraction.

Viral quantitation.

HIV plasma RNA was quantitated with the Amplicor Monitor assay (Roche Molecular Systems), used according to manufacturer’s specifications. The Roche Ultradirect assay, with a limit of detection of 20 RNA copies/ml, was performed on separate aliquots of plasma with values below 400 copies/ml (17). LN RNA was extracted by the Qiagen RNaeasy system, subjected to DNase treatment at 37°C for 1 h, and then reextracted according to the Amplicor protocol. Copy numbers were normalized both to mass of tissue and to T-cell receptor Cα mRNA, as previously described (27).

Heminested cDNA PCR assay for multiply spliced HIV RNA.

For each patient from whom adequate numbers of LNMC were available (patients B, H, I, and J), RNA was isolated from two aliquots of 2 × 105 LNMC by using Qiagen RNAeasy columns after lysates had been homogenized on Qiashredder columns. cDNAs were synthesized by using random hexamers, and heminested PCR was performed with primers designed to amplify tat and rev (multiply spliced) cDNAs. First-round primers were as previously described (21) except that the 5′ primer, Msense 1, contained a leader sequence and an EcoRI restriction site and the 3′ primer, Mantisense, contained a leader sequence and a BamHI restriction site. For the second round of PCR amplification, the primer Msense 2 (taatatgaattcgaagaagcggagacagcgacgaag [the leader sequence and EcoRI restriction site are shown in italic type) was used with Mantisense. This assay can detect multiply spliced RNA from two HIV-infected CEM cells in a terminal dilution assay (20).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Complete sequences of viral genes from all patients have been sent to GenBank (accession no. AF027708, AF027710, AF027715, and AF040578 through AF040627).

RESULTS

Viral load.

Plasma RNA levels, which were between 4.4 and 5.5 log units at baseline, had become undetectable (<20 copies/ml) in patients A and B. Those for subjects C and J were below the limit of detection of the Roche Amplicor monitor assay (<400 copies/ml) but showed 119 and 200 copies/ml, respectively, by the Ultradirect assay. Patient D had 800 copies of HIV RNA/ml of plasma. Table 1 shows the longitudinal RNA levels from patients A, B, C, D, and J. At the time point the LN biopsy was performed, patient D might have been about to fail indinavir monotherapy. However, after unblinding he was switched to triple therapy and again his plasma RNA levels became undetectable. The remaining subjects (patients E, F, G, H, and I) had considerably higher levels of plasma HIV RNA, ranging from 2,000 to 63,000 copies/ml. In contrast to plasma, viral RNA was recovered from all 10 LN biopsies examined, although the correlation of the level of HIV RNA in plasma and LN was high (27). An extrapolated reduction of ∼4 log10 of RNA copies/g of tissue was found after up to 1 year of treatment in patients A and B (RNA undetectable) and in patients C and D (very low plasma RNA loads) by using published data on untreated patients (9). In the poorly suppressed patients (patients E, F, G, H, and I) viral RNA loads in LN were found to be ∼108 copies/g, comparable to those for untreated patients.

TABLE 1.

Longitudinal plasma HIV RNA concentrations from five patients with either undetectable or very low plasma RNA levels

| Time on therapy (wk) | HIV RNA concn (copies/ml) from patient:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | J | |

| 0a | 62,680 | 19,200 | 51,704 | 95,176 | 10,242 |

| 4 | 1,195 | 651 | 2,223 | 3,433 | 625 |

| 8 | <50 | 144 | 414 | 1,745 | <50 |

| 12 | <50 | <50 | 184 | 861 | <50 |

| 16 | <50 | <50 | 78 | 431 | <50 |

| 20 | <50 | <50 | <50 | <50 | <50 |

| 24 | <50 | <50 | 228 | <50 | <50 |

| 28 | <50 | <50 | <50 | <50 | 50,843c |

| 32 | <50 | <50 | <50 | <50 | 1,477 |

| 36 | <50 | <50 | <50 | 164 | 598 |

| 40 | <20 | <50 | 119b | 418 | <50 |

| 42 | 200 | ||||

| 44 | <50 | <50 | <50 | 273 | <50 |

| 46 | <20 | ||||

| 48 | <50 | <50 | <50 | 323 | <50 |

| 52 | <50 | <50 | <50 | 800 | <50 |

Week 0 shows RNA copies/ml before randomized treatment (7). RNA values in boldface type represent plasma RNA concentrations from the same day when the LN biopsy was performed. At this time point the Roche Ultradirect assay was applied, whereas for all other time points the Roche Ultrasensitive assay was used.

From a sample drawn in the same week that the Roche Ultrasensitive assay showed <50 copies/ml. Plasma RNA from patients A, B, and C were monitored for up to 2 years (27).

Plasma RNA rebounded because of interruption of antiretroviral therapy.

Correlation between viral load and emergence of drug resistance.

At baseline the plasma RNA of all 10 patients harbored the M184 wild-type codon in RT, which is associated with lamivudine susceptibility (Table 2). After 1 year of therapy the M184V mutation had not developed in either of the two subjects on triple therapy who had undetectable levels of plasma RNA (<20 copies/ml). Subject A showed the wild-type codon in LN DNA, PBMC RNA, and PBMC DNA, and subject B showed the wild-type codon in LN RNA, LN DNA, and PBMC DNA. Codon 184 also remained wild type in patients D (on indinavir monotherapy) and J, both with low but measurable plasma RNA levels. However, patient C, also on triple therapy, harbored the early lamivudine resistance mutation M184I (23) in PBMC RNA, although the codon in LN RNA, LN DNA, and PBMC DNA remained wild type. In this subject plasma RNA was not detected by the Roche Amplicor assay but was found by the Ultradirect assay (119 copies/ml). Patients E through I all harbored the M184V mutation in plasma RNA, LN RNA, LN DNA, and PBMC RNA and/or DNA after 1 year.

TABLE 2.

Emergence of the M184V mutation and persistence of multiply spliced HIV mRNA after 1 year of potent chemotherapy

| Patient | Therapy | Result at baseline

|

Result at 1 yearc

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma RNA (log) | M184 plasma RNA | Plasma RNA (log) | M184 LN:

|

Additional compartmentsa | Multiply spliced RNAb | |||

| RNA | DNA | |||||||

| A | AZT-3TC-IND | 5.2 | WTd | <1.3 | NDe | WT | PBMC RNA, PBMC DNA | ND |

| B | AZT-3TC-IND | 4.7 | WT | <1.3 | WT | WT | PBMC DNA | − |

| C | AZT-3TC-IND | 5.2 | WT | 2.1 | WT | WT | PBMC DNA WT, PBMC RNA (M184I) | ND |

| D | IND | 5.2 | WT | 2.9 | WT | ND | ND | ND |

| J | AZT-3TC-IND | 5 | WT | 2.3 | ND | ND | PBMC DNA (WT) | + |

| E | AZT-3TC-IND | 5.5 | WT | 3.7 | M184V | M184V | Plasma RNA, PBMC DNA | ND |

| F | AZT-3TC-IND | 4.4 | WT | 3.3 | M184V | M184V | Plasma RNA, PBMC DNA | ND |

| G | AZT-3TC | 5 | WT | 4.3 | M184V | M184V | Plasma RNA, PBMC RNA | ND |

| H | AZT-3TC | 5.2 | WT | 4.8 | M184V | M184V | Plasma RNA, PBMC RNA | + |

| I | AZT-3TC | 5.1 | WT | 4.3 | M184V | M184V | Plasma RNA | + |

If not otherwise specified parenthetically, the additional compartment showed the same genotype as that reported in the LN.

Presence (+) or absence (−) of multiply spliced RNA in the LNMC.

Range, 36 to 52 weeks after initiation of therapy. (One year was the time point of the LN biopsy.)

WT, wild type.

ND, not done.

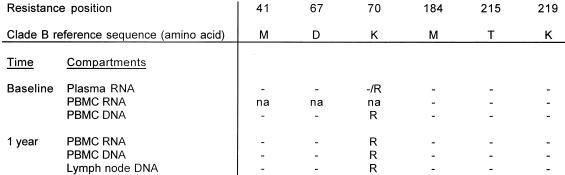

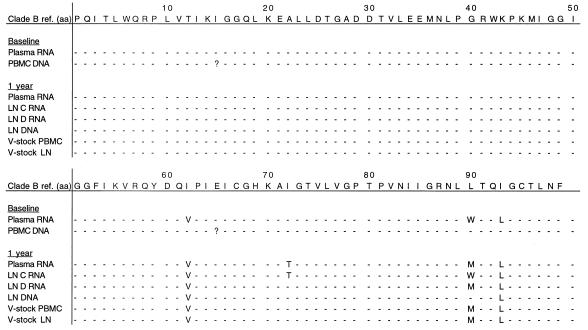

The protease and RT sequences from plasma RNA of patient A at baseline were the same as the LN DNA after 1 year of therapy (Fig. 1) with the exception of two known wild-type polymorphisms in protease (T10S and P63A) (13). The K70R mutation was present in the RT both at baseline and after 1 year (Fig. 2). Emergence of new drug resistance mutations in patients B, D, and J also did not occur (data not shown). Of particular interest was patient C, who developed the M184I mutation in PBMC RNA. In this patient, some degree of viral replication appeared to have taken place. However, the patient had not failed therapy and HIV plasma RNA remained undetectable after an additional year of follow-up.

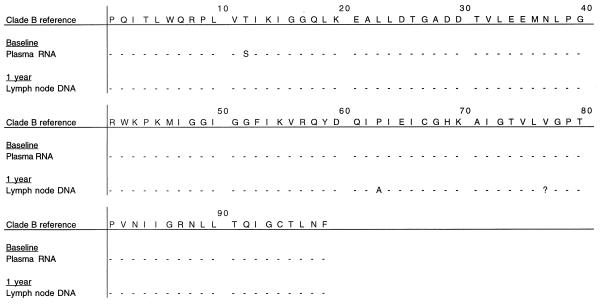

FIG. 1.

Amino acid residues associated with resistance to indinavir in different compartments from patient A at baseline and after 1 year. Amino acids in this figure and subsequent figures are given in the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry code. Dashes represent amino acids which are unchanged from the reference sequence. Numbers in the top row indicate protease codons. ?, codon not determined.

FIG. 2.

Amino acid residues associated with resistance to AZT or 3TC in different compartments from patient A at baseline and after 1 year. Dashes represent amino acids which are unchanged from the reference sequence. na, not done.

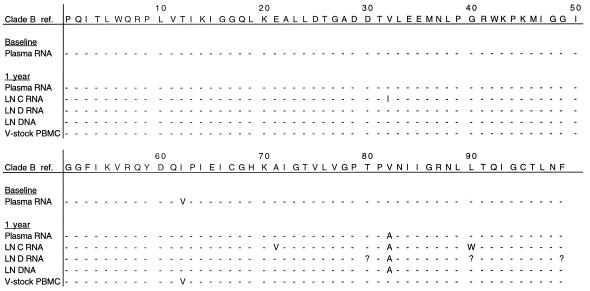

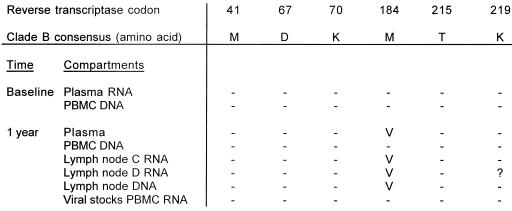

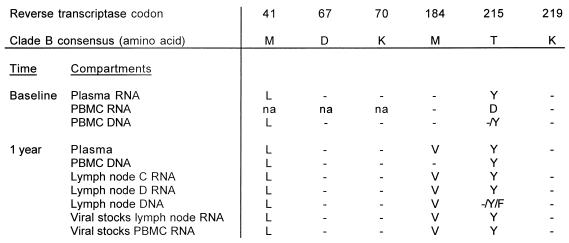

Subjects E and F both failed therapy because of noncompliance. Patient E interrupted therapy shortly before the LN biopsy was obtained: for 3 days 2 months prior to the biopsy and again for 6 days prior to the biopsy. The V82A mutation, associated with indinavir resistance, emerged in plasma RNA, LN RNA, and LN DNA (Fig. 3). One of the two LN RNA samples revealed the V32I mutation that is also associated with indinavir resistance (22). The M184V lamivudine resistance mutation was present in the RT region of plasma RNA, LN RNA, and LN DNA. In contrast, the protease and RT sequences generated from a viral stock of a PBMC culture were the same as the plasma RNA sequence at baseline (Fig. 4).

FIG. 3.

Amino acid residues associated with resistance to indinavir in different compartments from patient E at baseline and after 1 year. Dashes represent amino acids which are unchanged from the reference sequence. Numbers in the top row indicate protease codons. V, viral; ref., reference; ?, codon not determined; LN C RNA, RNA extracted from LN tissue sample C; LN D RNA, RNA extracted from a different piece, D, of the same LN.

FIG. 4.

Amino acid residues associated with resistance to AZT or 3TC in different compartments from patient E at baseline and after 1 year. Dashes represent amino acids which are unchanged from the reference sequence. ?, codon not determined. Lymph node C RNA, RNA extracted from LN tissue sample C; Lymph node D RNA, RNA extracted from a different piece D of the same LN.

Patient F interrupted therapy for 3 days 1 month before the LN biopsy was obtained. He developed the L90M drug resistance mutation in plasma RNA and LN RNA and viral stock sequences in the protease region. The known wild-type polymorphisms I62V and I92L were present at baseline and at the time of biopsy (Fig. 5). At position 72 of the protease, I72T had appeared in plasma RNA and in one LN RNA sample after 1 year; however, a second LN RNA sequence from a separate extraction did not show this mutation, nor did LN DNA and sequences derived from PBMC and LN culture stocks. This mutation has been described neither as a polymorphism nor as a drug resistance mutation in association with indinavir. In the RT, the M184V mutation emerged in all but the PBMC DNA sequences (Fig. 6). Patients G, H, and I, receiving AZT-3TC treatment only, all developed multiple resistance mutations in the RT in all compartments (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Amino acid residues associated with resistance to indinavir in different compartments from patient F at baseline and after 1 year. Dashes represent amino acids which are unchanged from the reference sequence. Numbers in the top row indicate protease codons. V, viral; ref., reference; aa, amino acid; ?, codon not determined. LN C RNA, RNA extracted from LN tissue sample C; LN D RNA, RNA extracted from a different piece, D, of the same LN.

FIG. 6.

Amino acid residues associated with resistance to AZT or 3TC in different compartments from patient F at baseline and after 1 year. Dashes represent amino acids which are unchanged from the reference sequence. Lymph node C RNA, RNA extracted from LN tissue sample C; Lymph node D RNA, RNA extracted from a different piece D of the same LN; na, not done.

Multiply spliced mRNA.

Detection of multiply spliced RNA reflects active HIV gene expression and may be an indicator of active viral replication. In patient B, with <20 RNA copies/ml in the plasma, multiply spliced RNA was not detected in LNMC. In contrast, it was clearly present in patients H, I, and J. Of particular interest was patient J, whose plasma HIV RNA level was only 200 copies/ml when the LN biopsy was performed. Four months before he had interrupted triple therapy for 3 weeks. Plasma RNA rebounded from undetectable to 50,843 copies/ml but became undetectable again 2 weeks before the LN biopsy was performed (Table 1). Although the LN RNA was significantly reduced, it was 10-fold greater than in subjects A and B and virus could be cultured from LNMC and PBMC by standard techniques (27).

Concordance of emergence of drug resistance mutations in different tissue compartments.

The concordance at known indinavir, AZT, and 3TC resistance residues (22) across different tissue compartments at a given time point was high (Table 3). In 11 positions associated with resistance in the protease region, only 7 (2%) of 330 amino acids showed discordance among the different tissues. The same comparison in the RT revealed 19 discordant amino acids (6%) of the 333 codons associated with AZT or 3TC resistance. Of these 19 discordances, wild-type codons were detected in six instances from LN DNA, two from PBMC DNA, and six from viral stock RNA, when resistance mutations were detected in the other compartments (Table 4). Of the seven discordances in the protease, three wild-type codons were detected in viral stocks, two in LN RNA and one in LN DNA, when mutations were found in the other compartments. One LN RNA sequence revealed a resistance codon, when wild-type codons were present in the other compartments.

TABLE 3.

Concordance of codons associated with resistance to indinavir, AZT, and 3TC in different tissues obtained concurrently from individual patients on potent antiretroviral therapy

| Gene and resistance position | No. of amino acids compared | No. of discordant amino acidsa |

|---|---|---|

| Protease | ||

| 10 | 30 | 0 |

| 20 | 30 | 0 |

| 24 | 30 | 0 |

| 32 | 30 | 1 |

| 46 | 30 | 0 |

| 54 | 30 | 0 |

| 63 | 30 | 0 |

| 71 | 30 | 2 |

| 82 | 30 | 2 |

| 84 | 30 | 0 |

| 90 | 30 | 2 |

| Total (%) | 330 (100) | 7 (2) |

| RT | ||

| 41 | 51 | 2 |

| 67 | 51 | 2 |

| 70 | 51 | 3 |

| 184 | 60 | 3 |

| 215 | 60 | 5 |

| 219 | 60 | 4 |

| Total (%) | 333 (100) | 19 (6) |

A resistance codon in a compartment was called discordant if in an individual patient the codon differed across other compartments at a given time point.

TABLE 4.

Compartments in which discordant codons of RT were detected

| Compartment | No. of observations of discordance | Discordances seen |

|---|---|---|

| LN DNA | 6 | Wild type, resistance in other compartments |

| PBMC DNA | 2 | Wild type, resistance in other compartments |

| Viral stock RNA | 6 | Wild type, resistance in other compartments |

| PBMC RNA | 1 | Wild type, resistance in other compartments |

| PBMC RNA | 1 | 184I, M elsewhere |

| PBMC RNA | 1 | 215D, Y elsewhere |

| Plasma RNA | 1 | 67A, D elsewhere |

| LN RNA | 1 | Wild type, resistance in other compartments |

DISCUSSION

In this study we systematically examined HIV RNA and DNA from blood and from LN for the detection of viral replication in patients treated with potent antiretroviral therapy for up to 1 year. Viral replication was defined by the emergence of drug resistance mutations in HIV-1 pol or by detection of multiply spliced RNA from LNMC.

These assays failed to provide evidence for in vivo virus replication in patients with plasma HIV RNA levels of <20 copies/ml. The otherwise rapidly emerging M184V mutation was not detected from LN (RNA or DNA) or from PBMC (RNA or DNA) in either patient A or B. Furthermore, no drug resistance mutations emerged in the protease or the RT region. In addition, multiply spliced RNA was not found in LNMC from patient B, which favors the absence of virus production, while it was present in the other three subjects tested (patients J, H, and I) in whom plasma HIV RNA was detectable. However, in patients C and J, for whom plasma HIV RNA was undetectable by the Roche Amplicor assay (limit of detection, 400 copies/ml) but was detected by the Ultradirect assay (limit of detection, 20 copies/ml), evidence of viral replication could be detected. The M184I mutation was present in the PBMC DNA of subject C, and in patient J multiply spliced RNA was detected and virus was isolated by standard techniques. When treatment with lamivudine fails, the M184I mutation initially appears before the emergence of virus, harboring the M184V mutation (23). In patient C the latter mutation did not emerge, and plasma RNA remained undetectable in the next year after the LN biopsy. Moreover, the M184I mutation was absent in virus isolated by enhanced methods 2 years after initiation of therapy, presumably from cells latently infected for a prolonged period (28). These observations point out that a potent drug regimen, despite low levels of viral replication present during the first year of therapy, may prevent further viral replication and result in long-term suppression. Subjects with RNA levels above 400 copies/ml all, with the exception of patient D, showed multiple drug resistance mutations in all compartments examined.

These findings suggest that three types of response patterns defined by assays for resistance and spliced RNA exist in patients treated with potent antiretroviral therapy: (i) undetectable in vivo replication, (ii) low-level in vivo replication, and (iii) poorly controlled viral replication (treatment failure). Of particular interest are patients with low-level replication, a potential group for treatment failure. Factors causing such low-level replication have yet to be determined and can only be speculated upon. Transient reductions in the bioavailability of drugs by noncompliance, interactions with other drugs, or temporary alterations in absorption might allow a relapse of replication. In vivo activation of long-lived latently infected cells (3) by immune stimuli could result in viral gene expression and subsequent replication, analogous to the recovery of virus with in vitro activation of PBMC from subjects with undetectable plasma RNA levels (5a, 28). A pool of cells with continuous low-level replication such as macrophages or dendritic cells, as postulated by others (19), might be in part refractory to potent antiretroviral therapy. The validity and in vivo relevance of these various hypotheses remain to be determined.

The comparison of mutations conferring resistance to AZT, 3TC, and indinavir across different tissue compartments at a given time point revealed a high concordance. The relatively few discordances detected were primarily wild-type codons present in LN DNA and to a lesser extent in PBMC DNA compared to the RNA sequenced concurrently from the same compartments. The delay in the emergence of detectable genotypic drug resistance in proviral DNA compared to RNA detected by population sequencing probably reflects the fact that only a minor proportion of proviral DNA clones are responsible for the majority of expressed PBMC genotypes, as has been shown in sequence analyses of the env region (16) and is consistent with the archival nature of most proviral DNA (24). In two studies of HIV dynamics in vivo using genotypic resistance to nevirapine as a genetic marker, the turnover of viral DNA from wild type to drug-resistant mutant was delayed and less complete than in plasma RNA (10, 26). Of interest in the present study is the fact that the M184V mutation was found in all LN DNA sequences when it was present in the other compartments. The relatively short period (as seen in patients E and F) needed by the M184V mutation to establish itself in sequences with a slow turnover, such as LN DNA, again underscores how easily and quickly this single point mutation can emerge.

Discordances were also identified when wild-type codons were found in viral RNA stocks grown from PBMC or LN while resistance mutations were present in sequences generated directly from the RNA of the corresponding clinical samples. This demonstrates that culture conditions in the absence of drugs can favor the outgrowth of wild type from genetic mixtures, and therefore resistance data derived from cultured virus alone may be misleading. These findings confirm earlier reports describing the ex vivo selection bias conferred by coculturing (4, 14, 16). Hypothetically, discordant base calls between different compartments might also be explained by a sampling factor. Patients A through E and J had only 4 to 5 log units of RNA/g of lymphoid tissue, and therefore the likelihood of amplifying minority quasispecies by RT-PCR may have been increased because of a low concentration of HIV genomes. However, in our study this appears not to have been an important factor, because discordances were not seen more often in the patients with low RNA copy numbers.

In conclusion, these findings argue that HIV replication differs significantly between patients on potent antiretroviral therapy with plasma RNA levels of <20 copies/ml, those with 20 to 400 copies/ml, and those with >400 copies/ml. These observations may have implications for the clinical management of patients and suggest that a therapeutic goal of plasma RNA levels of <20 copies/ml is important, because low-level replication can occur between 20 and 400 copies/ml and may potentially allow the selection of resistance mutations and subsequently lead to therapeutic failure. Factors responsible for such low levels of viral replication need to be determined in future studies, and its clinical significance will require observations of larger numbers of patients for longer periods.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the participating patients; T. R. Gingeras, K. B. Considine, and V. Liang, Affymetrix, for advice and technical support; C. K. Shih, Boehringer Ingelheim, for providing the NL4-3 M41L/T215Y mutant; S. Kwok, Roche Molecular Systems, Alameda, Calif., for performing the Ultrasensitive RNA PCR; and E. Emini, Merck Research Laboratories, West Point, Pa., for his cooperation. In addition we thank D. Easter, K. Nuffer, G. Dyak, and B. Coon for procurement of LN biopsy samples; N. Keating, S. Albanil, and J. Aufderheide for viral isolation; and S. Wilcox and D. Smith for administrative assistance.

H. Günthard was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant 84AD-046176). This work was supported by grants K 11 AI01361, AI 38201, AI 27670, AI 38858, and AI 36214 (Center for AIDS Research) and grant AI 29164 from the National Institutes of Health and by the Research Center for AIDS and HIV Infection of the San Diego Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boucher C A, Cammack N, Schipper P, Schuurman R, Rouse P, Wainberg M A, Cameron J M. High-level resistance to (−) enantiomeric 2′-deoxy-3′-thiacytidine in vitro is due to one amino acid substitution in the catalytic site of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase. Animicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2231–2234. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.10.2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cavert W, Notermans D W, Staskus K, Wietgrefe S W, Zupancic M, Gebhard K, Henry K, Zhi-Qiang Z, Mills R, McDade H, Goudsmit J, Danner S V, Haase A T. Kinetics of response in lymphoid tissues to antiretroviral therapy of HIV-1 infection. Science. 1997;276:960–963. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5314.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chun T W, Carruth L, Finzi D, Xuefei S, DiGiuseppe J A, Taylor H, Hermankova M, Chadwick K, Margolick J, Quinn T C, Kuo Y H, Brookmeyer R, Zeiger M A, Barditch-Crovo P, Siliciano R F. Quantification of latent tissue reservoirs and total body viral load in HIV-1 infection. Nature. 1997;387:183–188. doi: 10.1038/387183a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delassus S, Cheynier R, Wain-Hobson S. Evolution of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nef and long terminal repeat sequences over 4 years in vivo and in vitro. J Virol. 1991;65:225–231. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.1.225-231.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Embretson J, Zupancic M, Ribas J L, Burke A, Racz P, Tenner-Racz K, Haase A T. Massive covert infection of helper T lymphocytes and macrophages by HIV during the incubation period of AIDS. Nature. 1993;362:359–362. doi: 10.1038/362359a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5a.Finzi D, Hermankova M, Pierson T, et al. Identification of a reservoir for HIV-1 in patients on highly active antiviral therapy. Science. 1997;278:1295–1300. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furtado M R, Kingsley L A, Wolinsky S M. Changes in the viral mRNA expression pattern correlate with a rapid rate of CD4+ T-cell number decline in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected individuals. J Virol. 1995;69:2092–2100. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2092-2100.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gulick R M, Mellors J W, Havlir D, et al. Treatment with indinavir, zidovudine, and lamivudine in adults with human immunodeficiency virus infection and prior antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:734–739. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709113371102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Günthard H F, Wong J K, Ignacio C C, Havlir D V, Richman D D. Abstracts of the 4th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections January 1997, Washington, D.C. 1997. Comparative performance of high density oligonucleotide sequencing and dideoxynucleotide sequencing of HIV-1 Pol from clinical samples, abstr. 577. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haase A T, Henry K, Zupancic M, Sedgewick G, Faust R A, McIroe H, Cavert W, Gebhard K, Staskus K, Zhang Z Q, Dailey P J, Balfour H H, Jr, Erice A P, Perelson A S. Quantitative image analysis of HIV-1 infection in lymphoid tissue. Science. 1996;274:985–989. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5289.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Havlir D V, Eastman S, Gamst A, Richman D D. Nevirapine-resistant human immunodeficiency virus: kinetics of replication and estimated prevalence in untreated patients. J Virol. 1996;70:7894–7899. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7894-7899.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Japour A J, Mayers D L, Johnson V A, Kuritzkes D R, Beckett L A, Arduino J-M, Lane J, Black R J, Reichelderfer P S, D’Aquila R T, Crumpacker C S The RV-43 Study Group; The AIDS Clinical Trials Group Virology Committee Resistance Working Group. Standardized peripheral blood mononuclear cell culture assay for determination of drug susceptibilities of clinical human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1095–1101. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.5.1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim S Y, Byrn R, Groopman J, Baltimore D. Temporal aspects of DNA and RNA synthesis during human immunodeficiency virus infection: evidence for differential gene expression. J Virol. 1989;63:3708–3713. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.9.3708-3713.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kozal M J, Shah N, Shen N, Yang R, Fucini R, Merigan T C, Richman D D, Morris D, Hubbell E, Chee M, Gingeras T R. Extensive polymorphisms observed in HIV-1 clade B protease gene using high-density oligonucleotide arrays. Nat Med. 1996;2:753–759. doi: 10.1038/nm0796-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kusumi K, Conway B, Cunningham S, Berson A, Evans C, Iversen A K N, Colvin D, Gallo M V, Coutre S, Shpaer E G, Faulkner D V, deRonde A, Volkman S, Williams C, Hirsch M S, Mullins J I. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope gene structure and diversity in vivo and after cocultivation in vitro. J Virol. 1992;66:875–885. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.875-885.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Markowitz, M., Y. Cao, M. Vesanen, A. Talal, D. Nixon, A. Hurley, R. O’Donovan, P. Racz, K. Tenner-Racz, and D. D. Ho. Recent HIV infection treated with AZT, 32TC, and a potent protease inhibitor, abstr. LB 8. In Abstracts of the 4th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections January 1997, Washington, D.C.

- 16.Michael N L, Chang G, Ehrenberg P K, Vahey M T, Redfield R R. HIV-1 proviral genotypes from the peripheral blood mononuclear cells of an infected patient are differentially represented in expressed sequences. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1993;6:1073–1085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulder J, Resnick R, Saget B, Scheibel S, Herman H, Payne H, Harrigan R, Kwok S. A rapid and simple method for extracting human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA from plasma: enhanced sensitivity. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1278–1280. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1278-1280.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pantaleo G, Graziosi C, Butini L, Pizzo P A, Schnittmann S M, Kotler D P, Fauci A S. Lymphoid organs function as major reservoirs for human immunodeficiency virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:9838–9842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pantaleo G. How immune-based interventions can change HIV therapy. Nat Med. 1997;3:483–486. doi: 10.1038/nm0597-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riggs, N. L., S. Little, and J. C. Guatelli. 1997. Unpublished data.

- 21.Saksela K, Muchmore E, Girard M, Fultz P, Baltimore D. High viral load in lymph nodes and latent human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in peripheral blood cells of HIV-1 infected chimpanzees. J Virol. 1993;67:7423–7427. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7423-7427.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schinazi R F, Larder B A, Mellors J W. Mutations in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase and protease associated with drug resistance. Int Antiviral News. 1997;5:129–134. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schuurman R, Nijhuis M, van Leeuwen R, Schipper P, de Jong D, Collis P, Danner S A, Mulder J, Loveday C, Christoperson C, Kwok S, Sninsky J, Boucher C A B. Rapid changes in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA load and appearance of drug-resistant virus populations in persons treated with lamivudine (3TC) J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1411–1419. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.6.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simmonds P, Zhang L Q, McOmish F, Balfe P, Ludlam C A, Brown A J L. Discontinuous sequence change of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 env sequences in plasma viral and lymphocyte-associated proviral populations in vivo: implications for models of HIV pathogenesis. J Virol. 1991;65:6266–6276. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.6266-6276.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tisdale M, Kemp S D, Parry N R, Larder B A. Rapid in vitro selection of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistant to 3′-thiacytidine inhibitors due to a mutation in the YMDD region of reverse transcriptase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5653–5656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei X, Ghosh S K, Taylor M E, Johnson V A, Emini E A, Deutsch P, Lifson J D, Bonhoeffer S, Nowak M A, Hahn B H, Saag M S, Shaw G M. Viral dynamics in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Nature. 1995;373:117–122. doi: 10.1038/373117a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong J K, Günthard H F, Havlir D V, Zhang Z, Haase A T, Ignacio C C, Kwok S, Emini E, Richman D D. Reduction of HIV-1 in blood and lymph nodes following potent anti-retroviral therapy and the virologic correlates of treatment failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;95:12574–12579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong J K, Hezareh M, Günthard H F, Havlir D V, Ignacio C C, Spina C A, Richman D D. Recovery of replication-competent HIV despite prolonged suppression of plasma viremia. Science. 1997;278:1291–1295. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]