Abstract

The increasing knowledge of molecular alterations in malignancies, including mutations and regulatory failures in the mTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin) signaling pathway, highlights the importance of mTOR hyperactivity as a validated target in common and rare malignancies. This review summarises recent findings on the characterization and prognostic role of mTOR kinase complexes (mTORC1 and mTORC2) activity regarding differences in their function, structure, regulatory mechanisms, and inhibitor sensitivity. We have recently identified new tumor types with RICTOR (rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR) amplification and associated mTORC2 hyperactivity as useful potential targets for developing targeted therapies in lung cancer and other newly described malignancies. The activity of mTOR complexes is recommended to be assessed and considered in cancers before mTOR inhibitor therapy, as current first-generation mTOR inhibitors (rapamycin and analogs) can be ineffective in the presence of mTORC2 hyperactivity. We have introduced and proposed a marker panel to determine tissue characteristics of mTOR activity in biopsy specimens, patient materials, and cell lines. Ongoing phase trials of new inhibitors and combination therapies are promising in advanced-stage patients selected by genetic alterations, molecular markers, and/or protein expression changes in the mTOR signaling pathway. Hopefully, the summarized results, our findings, and the suggested characterization of mTOR activity will support therapeutic decisions.

Keywords: mTOR, mTORC2 hyperactivity, RICTOR amplification, Rictor overexpression, malignancies

Regulatory role of mTOR and its hyperactivity in cancer

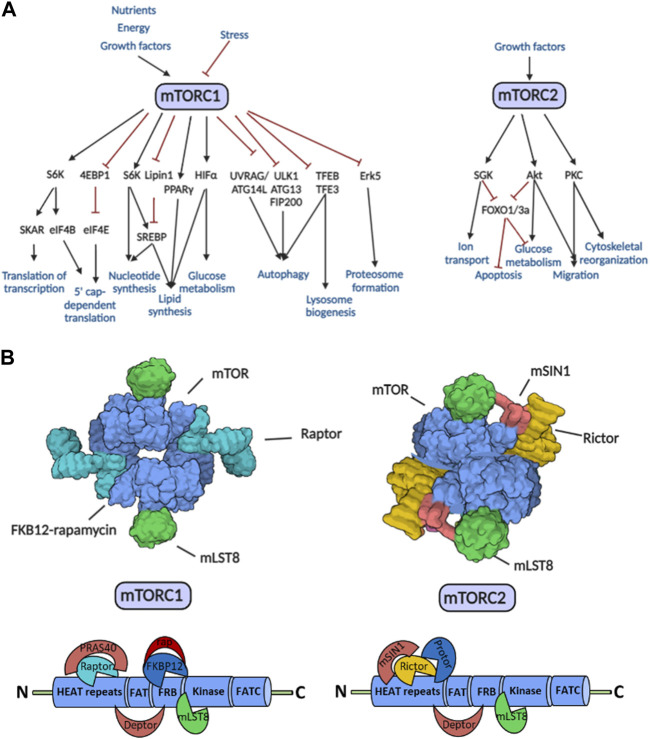

The mechanistic (formerly mammalian) target of rapamycin (mTOR) influences various cellular processes (proliferation, motility, migration, metabolism, protein synthesis, transcription, etc.,) by integrating signals from the tissue environment. mTOR promotes cell growth and survival, depending on the actual state of the cell. In addition, a decrease in mTOR activity in the absence of growth factors, nutrients, or other energy sources (e.g., oxygen) inhibits cell growth and triggers survival-promoting cellular processes such as autophagy. As a central signaling pathway hub, mTOR kinase plays an essential role in metabolic regulation to maintain the balance between anabolic and catabolic processes, including metabolic adaptation in stress responses and tumor cell survival (Figure 1A). Dysfunction (hyper- or underactivation) of the mTOR kinase may contribute to regulatory failures and subsequently to the development and progression of diseases (e.g., metabolic, neurodegenerative, and cardiovascular diseases, accelerated aging, tumors) [1, 2].

FIGURE 1.

The regulatory roles, target proteins, and structure of the mTORC1 and mTORC2. (A) Effector mechanisms and functions of the mTORC1 and mTORC2. The schematic diagram shows the activating (black lines with arrows) and inhibitory (red lines with inhibition signs) effects. (B) Structural elements mTORC1 and mTORC2. The X-ray crystallographic field structure of mTOR complexes and the binding sites of specific partner molecules on the mTOR kinase domain are shown in the figure. Abbreviations: Deptor, DEP domain containing mTOR-interacting protein; HEAT repeats, Huntingtin, elongation factor 3 (EF3), protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), TOR1; FAT domain, FRAP, ATM, TRRAP; FRB domain, FKBP12-rapamycin binding; FATC domain, C-terminal FAT domain; mLST8, mammalian lethal with sec-13 protein 8; mSin1, mammalian stress-activated map kinase-interacting protein 1; PRAS40, proline-rich Akt substrate of 40 kDa; Protor, protein observed with Rictor; rap, rapamycin; Raptor, regulatory-associated protein of mTOR; Rictor, rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR; other explanations in text.

mTOR is a serine-threonine kinase that forms two complexes (mTOR complex 1—mTORC1; mTOR complex 2—mTORC2) organized from different, functionally distinct proteins (Figure 1B). The identical subunits in the two complexes are mTOR kinase, mLST8 (mammalian lethal with sec-13 protein 8), and Deptor (DEP domain containing mTOR-interacting protein). PRAS40 (proline-rich Akt substrate of 40 kDa) and the scaffolding protein Raptor (regulatory-associated protein of mTOR) are involved in the assembly of mTORC1. mSin1 (mammalian stress-activated map kinase-interacting protein 1), Protor 1/2 (protein observed with Rictor 1 and 2), and the scaffolding protein Rictor (rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR) instead of Raptor are in mTORC2 [3].

mTORC1 plays a role in several cellular processes (e.g., protein, lipid and nucleotide synthesis, ribosome biogenesis), whereas mTORC2 has a significant role in the modulation of cell survival, differentiation, growth, and migration and the maintenance of the actin cytoskeleton, mainly through the phosphorylation of Akt (Ser473), PKCα, and SGK1 [4].

mTOR complexes and their dysfunction—mainly hyperactivity—have been associated with the development and progression of malignancies. Hyperactivity of mTOR complexes can occur in several ways; including gene mutations affecting mTOR kinase, mutations in proteins that directly regulate the mTOR complex activity, or other changes in the signaling network (e.g., mutations in oncogenic or tumor suppressor genes).

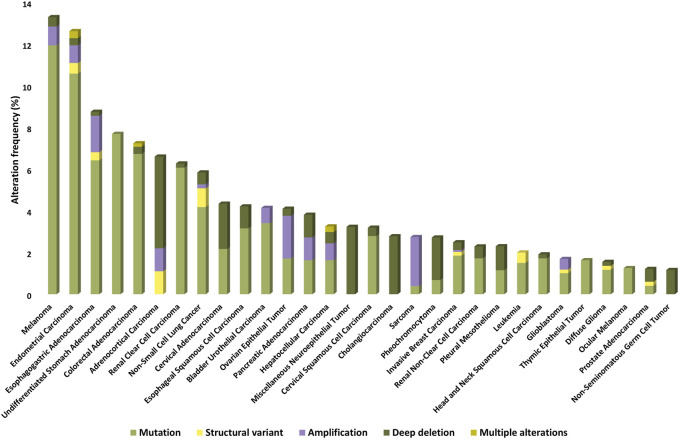

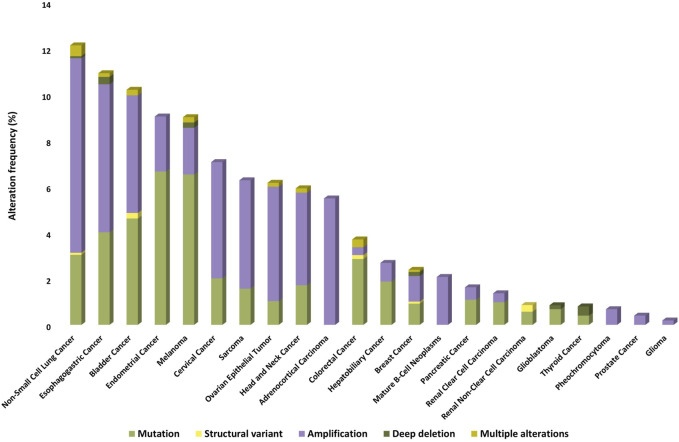

Nearly 5% of solid tumors may carry an activating mutation of mTOR kinase, which may be more common (>5%) in melanoma, endometrial, gastrointestinal, kidney, breast, and lung cancers [5]. On the basis of publicly available databases, the frequencies of genetic alterations associated with/related to mTOR kinase in different malignancies are summarized in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Prevalence of MTOR gene mutations, amplifications, deletions, and other structural gene defects in human tumors (based on TCGA PanCancer Atlas Studies databases).

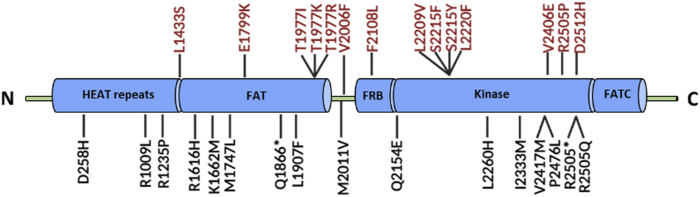

The enzymatic activity and oncogenic role of mTOR kinase are generally increased by somatic mutations affecting six different kinase regions. The most common activating mutations are E1799K, T1977R, V2006F, S2215Y, and R2505P, which are responsible for amino acid substitutions (Figure 3). Activating mutations do not affect the assembly of the mTOR complex but can reduce the binding of Deptor—an inhibitor of mTOR kinase—and increase the phosphorylation of target molecules (e.g., P70S6K, 4EBP1) [6, 7]. Some mutations alter the structure of the complex, leading to resistance to allosteric mTOR inhibitors (e.g., rapamycin) by preventing drug binding. For instance, F2108L point mutation occurs in the FKBP-binding (FRB) domain of mTOR, where the FKB12-rapamycin binding site is located [8].

FIGURE 3.

The structure of the mTOR kinase domain and some common mutations. The most common mutations responsible for changes in the structure of mTOR kinase are highlighted in red. Abbreviations: HEAT repeats, Huntingtin, elongation factor 3 (EF3), protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), TOR1; FAT domain, FRAP, ATM, TRRAP; FRB domain, FKBP12-rapamycin binding; FATC domain, C-terminal FAT domain; other explanations in text.

Most commonly, other mutations can cause pathway hyperactivity or loss of negative regulators in the signaling network (e.g., PI3KCA, PTEN, TSC1/2, STK11, and AKT1). PI3KCA mutations occur in more than 20% of breast and gynecological cancers and are also common in colorectal tumors. PTEN mutations are found in 10% of central nervous system and endometrial tumors, TSC1 mutations in 5%–6% of urinary tract and endometrial tumors, and TSC2 mutations in 4%–7% of gynecological, liver, and lung tumors. STK11 mutations occur in 10%–15% of the cervical, small bowel, and lung tumors, while AKT1 mutations are the least frequent of the signaling mutations (3%–5%). In many cases, mutations in receptor tyrosine kinases and growth factor receptors (EGFR and HER2) underline mTOR hyperactivity [9].

In addition to direct mutations in the mTOR kinase and the above-mentioned mutations affecting mTOR signaling, other gene mutations can occur in different subunits of the mTOR complex. One of the most common alterations is RICTOR amplification, which—in addition to increased expression of the Rictor protein—can increase the activity of the mTORC2 complex. In this context, it can affect/activate the target protein Akt kinase, which plays an essential role in the growth and survival of tumor cells (see below).

In situ studies of mTOR activity

The discovery of mTOR complexes and the potential therapeutic relevance of the mTOR kinase inhibitor rapamycin focused attention on the need to characterize mTOR activity. First-generation allosteric mTOR inhibitors are effective in the case of mTORC1 hyperactivity, although these may be ineffective in specific known FRB domain mutations or the presence of high mTORC2 activity. Therefore, the development of a new generation of mTOR kinase inhibitors that inhibit both mTORC1 and mTORC2 and additional inhibitors such as dual inhibitors has been initiated. Based on many published data, it is necessary to characterize mTOR activity in situ before starting mTOR-targeted therapies, as the efficacy of drug treatment may also depend on the ratio of the complexes.

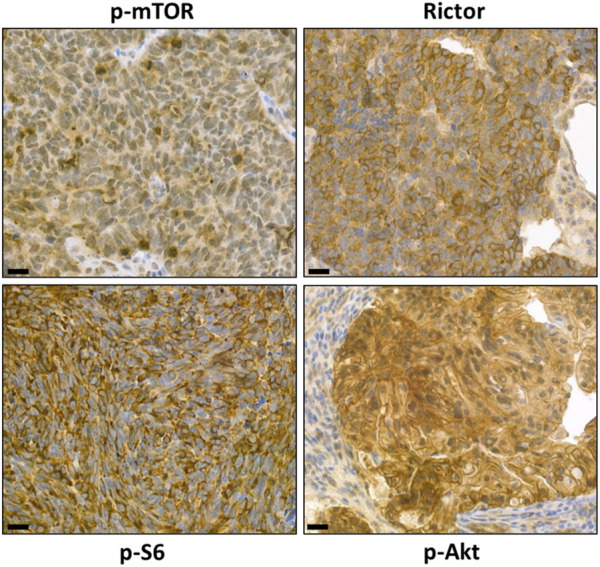

In our studies, we have developed marker panels that can be used in a wide range of tumor types to quantify and morphologically characterize not only mTORC1 but also mTORC2 complex activity in tumor cells or tissues. Characterization of mTOR activity in different cell lines and patient material can be performed by staining/measuring the active, phosphorylated form of mTOR kinase (p-mTOR) and its phosphorylated targets (e.g., p-4EBP1, p-p70S6K, p-S6) using immunohistochemistry (IHC)/immunocytochemistry and/or Western blot/WesTM Simple. One of the target proteins of the mTORC2 complex is the Akt kinase, where the amino acid serine 473 can only be phosphorylated by active mTORC2. On the basis of publicly available results, quantitative and in situ analysis of p-Akt (Ser473) is the most appropriate way to monitor the mTORC2 activity.

A quantitative comparison of the two mTOR complexes can also be determined from the ratio of specific scaffold proteins (Raptor for mTORC1 and Rictor for mTORC2). The optimal in situ marker panel is either a combination of p-mTOR, Raptor, and Rictor or a combination of mTORC1 target proteins (e.g., p-S6, p-70S6K, p-4EBP1) and a specific mTORC2 target protein [p-Akt (Ser473)] (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Representative images of characterizing mTORC1 and mTORC2 activity with our marker panel using immunohistochemistry. Detection of high levels of p-mTOR, p-S6, and Rictor in situ in brain metastases of small cell lung carcinoma and detection of p-Akt on paraffin sections of colorectal adenocarcinoma specimens. The magnifications are indicated, with 50 μm for IHC.

mTOR and mTORC1 hyperactivity in malignant tumors

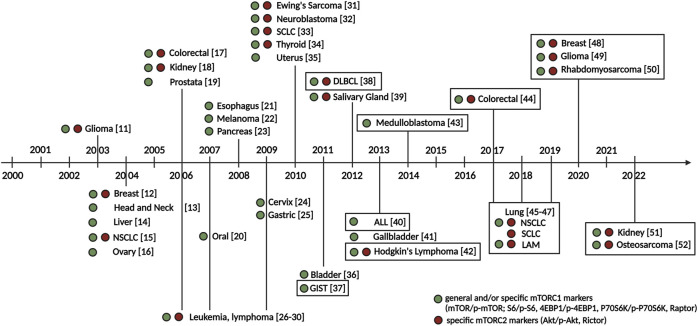

The first clinical anti-tumor observation of the mTOR inhibitor, the immunosuppressive drug rapamycin, was detected in the treatment of post-transplant kidney cancer [10]. Following the discovery of mTOR complexes, the mTOR hyperactivity and/or sensitivity of tumor cells against mTOR inhibitors, quantitative changes in the mTOR signaling pathway elements, target proteins, and their active forms have been described and partially characterized in various tumor types by the end of the last century and early 2000 s (detailed in Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Milestones in the early characterization of mTOR hyperactivity in tumors. The first immunohistochemical characterizations of mTOR activity in the most common and later less common tumor types in the early 2000 s and our domestic characterizations (our work highlighted in a frame) are shown in the figure. Green and red circles indicate histopathological studies that detected general and/or specific mTORC1 complex markers (mTOR/p-mTOR; S6/p-S6, 4EBP1/p-4EBP1, P70S6K/p-P70S6K, Raptor) and specific mTORC2 complex markers (Akt/p-Akt, Rictor). Numbers indicate references. Abbreviations: ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumor; LAM, lymphangioleiomyomatosis; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; SCLC, small cell lung cancer [11–52].

Our studies have contributed to the characterization of mTORC1 activity in hematological malignancies and even to the investigation of both mTOR complexes in leukemias and lymphomas. Summarizing these studies, acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cells and several lymphoma model cell lines (Hodgkin’s lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), anaplastic large cell lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, Burkitt’s lymphoma) show high mTORC1 activity. In addition to the generally high mTOR activity, the poorest survival outcomes were observed with the co-occurrence of high mTOR activity and increased Rictor expression. These findings highlight the unfavorable prognostic role of increased mTORC2 activity in the majority of lymphoid malignancies studied [38, 40, 42].

In addition to in vitro lymphoma models, mTOR hyperactivity has been characterized in the most common solid tumors and several human malignant tissues. In gastrointestinal tumors (colon tumors, gastrointestinal stromal tumors—GIST), we first characterized the activity of mTOR complexes, based on the amount of mTORC1 and mTORC2 scaffold proteins, and classified Hungarian colon tumor cases into three main groups (low Raptor and high Rictor expression—high mTORC2 activity; high Raptor and low Rictor expression—high mTORC1 activity; similar levels of Raptor and Rictor expression—balanced mTORC1 and mTORC2 activity). We compared our results with the clinical characteristics of the patients and found the best treatment and survival outcomes in cases with low mTORC1 activity, whereas the worst survival outcomes were observed in cases with high mTOR activity and high Rictor expression. Our results also showed that Rictor expression was associated with poor prognosis independently of mTOR activity [37, 44]. In our human breast cancer studies over the past few years, we have detected mTORC1 hyperactivity in 50% of our cases, supporting the use of previously introduced mTOR inhibitor therapy. In addition, we observed high Rictor expression—the increased presence of the mTORC2 complex—in more than 40% of the cases studied, which may explain the ineffectiveness of conventional rapalogue (rapamycin and its derivatives) treatments [48]. We also characterized mTOR activity in renal tumors. In our comparative studies, we could detect higher expression of p-mTOR and p-S6 markers in clear cell renal cell carcinoma compared to papillary renal cell carcinoma and normal tubular epithelial cells. Moreover, papillary renal cell carcinoma was characterized by high Rictor expression and potential mTORC2 activity, also highlighting the role of mTORC2 activity in this tumor type [51]. There has been an emerging need to characterize mTOR activity in rare solid tumors. Our studies also aimed to investigate the mTOR activity in rare tumor types, such as central nervous system tumors, childhood rhabdomyosarcoma, osteosarcoma, medulloblastoma, and fibrosarcoma [43, 49, 50, 52, 53].

Overexpression of the Rictor protein and the associated increase in the amount and activity of mTORC2

Rictor is a characteristic actin coordinating scaffold protein of the mTORC2 complex, and its primary function is to ensure the formation and structure of the mTORC2 complex. Rictor contributes to the formation of a spatially structured mTORC2 complex in which the FKBP-rapamycin binding region of the mTOR kinase is located inside the molecule, blocking access to the best-known and most widely used inhibitor of rapamycin and its first-generation derivatives (rapalogs) [1]. Consequently, these inhibitors do not directly affect the mTORC2 target proteins (e.g., Akt). Increased Rictor expression is generally associated with transcriptional and translational changes. One of the best-known oncogenic mutations affecting the mTOR kinase pathway is the amplification of the RICTOR gene. RICTOR amplification can lead to increased expression of the Rictor protein and, in most cases, an increase in mTORC2 complex activity and a shift in the ratio of mTORC1 to mTORC2 complexes. RICTOR amplification has been described to play an essential role in the progression of certain tumors and metastasis via the regulation of signaling pathways (e.g., MAPK/ERK, Wnt/β-catenin pathways) [54].

Among the genetic defects of RICTOR, the most frequently observed change is its amplification, but other alterations have also been described [55]. The genetic alteration frequency of RICTOR in different malignancies is summarized in Figure 6 (based on public databases).

FIGURE 6.

Prevalence of RICTOR gene mutations, amplifications, deletions, and other structural gene defects in human tumors (based on TCGA PanCancer Atlas Studies databases).

Additionally, higher Rictor expression has been described in several tumor types, including lung [56], esophageal [57], breast [58], pancreatic [59], liver [60], and melanoma [61], where high Rictor expression was associated with poorer prognosis and shorter survival [55]. Table 1 summarizes mTORC2 hyperactivity and/or RICTOR amplification in different tumor types.

TABLE 1.

Prevalence, prognostic, and therapeutic implications of Rictor expression and/or RICTOR amplification in various tumor types.

| Tumor types | Data on Rictor expression and/or RICTOR amplification | Prognostic and therapeutic implications | Relevant publications | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Tumors | HER2+, Luminal A/B, and Triple-Negative Breast Cancer | 37%–50% expression (IHC) | Increased mTORC2 activity is associated with an increased risk of metastasis and poorer prognosis | [48, 62–64] |

| Metastatic Breast Cancer (lymph node) | — | [65] | ||

| Central Nervous System Tumors | Glioma, Glioblastoma | — | mTORC2 can be a potential therapeutic target. | [49, 66–69] |

| Digestive System Tumors | Colorectal Cancer | 58% expression (IHC) | Increased Rictor expression is associated with therapy resistance, poorer prognosis, and shorter overall survival. Treatment with mTOR inhibitors may be beneficial in combination with other therapies (e.g., EGFR inhibitors, platinum-based chemotherapy) | [44, 70–73] |

| Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma | 70% expression (IHC) | [57] | ||

| Gastric Cancer | 46%–78% expression (IHC), 38% amplification (FISH) | [73–75] | ||

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Cholangiocarcinoma | 40%–43% expression (IHC) | [73, 76, 77] | ||

| Pancreatic Cancer | — | [59, 78] | ||

| Female Genital Tumors | Endometrial Cancer | 44% expression (IHC) | Increased Rictor expression correlates with stage, metastasis, and poorer prognosis | [79] |

| Head and Neck Tumors | — | 70% expression (IHC) | — | [80–82] |

| HPV-associated Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma | — | Increased Rictor expression is associated with a poorer prognosis | [83] | |

| Other tumors | Pheochromocytoma | 80% expression (IHC) | — | [84] |

| Skin Tumors | Melanoma | — | The presence of liver metastasis correlates with increased Rictor expression, and inhibition of mTORC2 may reduce metastasis formation | [61, 85] |

| Soft Tissue and Bone Tumors | — | 28% expression (IHC), 20% expression (Western blot) | High mTORC2 activity is associated with a poorer prognosis | [73, 86] |

| Myxofibrosarcoma | — | [87] | ||

| Osteosarcoma | 25% expression (IHC) | [52] | ||

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 82% expression (IHC) | [50] | ||

| Thoracic Tumors | Lymphangioleiomyomatosis | 55% expression (IHC) | — | [47] |

| Metastatic Lung Cancer | 66% expression (IHC) | — | [45] | |

| Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | 37% expression (IHC) | — | [45, 73] | |

| Small Cell Lung Cancer | 14% expression (IHC), 6%–15% amplification (sequencing) | — | [46, 88–90] | |

| Tumors of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues | Leukemia and Lymphoma (Acute Myeloid Leukemia, Acute Lymphoid Leukemia, Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia, Chronic Myeloid Leukemia, Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma) | 43%–63% expression (IHC) | High mTORC2 activity is associated with a poorer prognosis; inhibition of mTORC2 may be effective | [38, 42, 91–94] |

| Urinary and Male Genital Tumors | Bladder Cancer | — | Increased mTORC2 activity may affect the invasiveness of bladder cancer cells | [95] |

| Kidney Cancer | 47% expression (IHC) | Resistance to rapalogs is associated with increased mTORC2 activity | [51, 73, 96] | |

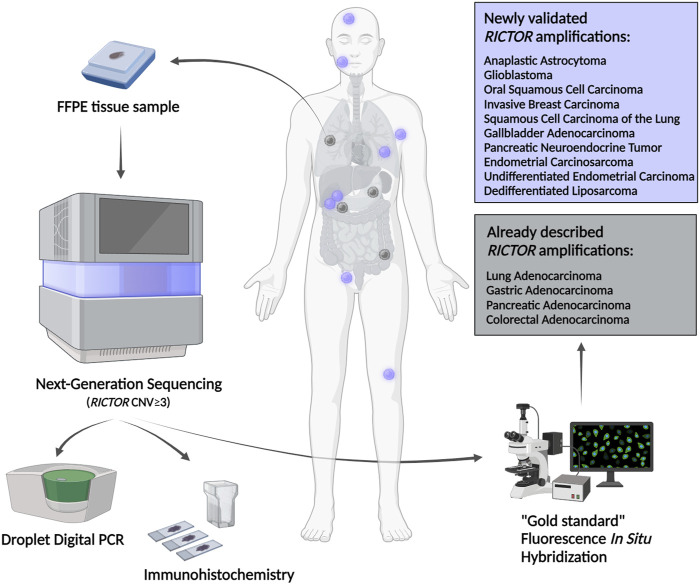

Methods to study RICTOR amplification, Rictor expression, and mTORC2 activity

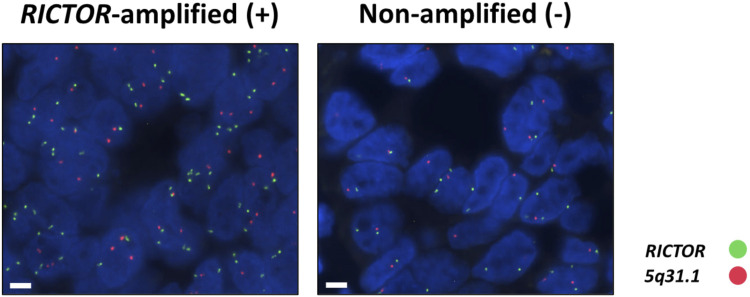

RICTOR amplification may indicate high mTORC2 activity and may be a predictive marker of effective inhibition of the PI3K/mTOR/Akt axis. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is considered the gold standard validation diagnostic method for identifying RICTOR amplification (Figure 7). In addition, potential changes in copy number can be detected by sequencing (e.g., next-generation sequencing) or Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR). The Rictor protein expression can be detected by immunohistochemistry or immunocytochemistry. As mentioned above, the mTORC2 complex is exclusively responsible for the phosphorylation of serine 373 in the Akt protein. Increased p-Akt (Ser473) protein expression is a clear sign and an excellent marker of increased mTORC2 complex activity [46, 50]. It is important to note that tissue sample preparation and fixation require special attention when testing for p-Akt (Ser473) expression. Failures in the process and the timing of tissue sample fixation may reduce the detectability of phosphorylated proteins.

FIGURE 7.

Representative images of the RICTOR FISH assay in RICTOR-amplified (+) and non-amplified (−) human tumor cases (RICTOR FISH was performed on the patient population of reference #97). The RICTOR (green) was used alongside the assay designed for the long arm (5q31.1) of chromosome 5 (orange) as a control (ZytoLight SPEC RICTOR/5q31.1 Dual Color Probe—ZytoVision GmbH; Bremerhaven, Germany). The magnifications are indicated, with 5 μm for FISH.

In our latest study, the diagnostic next-generation sequencing presumed RICTOR amplification was further analyzed in different human tumor tissues. RICTOR amplification was tested by ddPCR and validated using the “gold standard” FISH. In addition, Rictor and p-Akt (Ser473) protein expression was also examined by immunohistochemistry. The 10 novel and 4 previously described various tumor types with FISH-validated RICTOR amplification demonstrate the significance of RICTOR amplification in a wide range of malignancies (detailed in Figure 8). The newly described entities with RICTOR amplification may initiate further studies with larger cohorts to analyze the prevalence of RICTOR amplification also in rare diseases [97].

FIGURE 8.

Newly described tumor types with FISH-validated RICTOR amplification. Abbreviations: FFPE, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded; CNV, copy number variation.

mTOR hyperactivity and RICTOR amplification in lung tumors

Dysregulation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway plays an important role in the development and progression of the majority of lung cancers [98]. mTOR activity can be affected by failures in other signaling pathways related to the mTOR pathway and the known alterations in mTOR pathway activity (see above). In this context, the combined inhibition of mTOR and other kinases may provide additional therapeutic options for treating lung tumors [56].

Among non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC), 90% of adenocarcinomas, 40% of squamous cell carcinomas, and 60% of large cell carcinomas are characterized by increased activity of PI3K/Akt/mTOR axis [99]. Elevated levels of phosphorylated mTORC1 targets (e.g., p-4EBP1, p-S6) have been observed in adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. In these studies, tumor invasiveness, metastasis, and poorer prognosis are associated with increased activity of mTOR [100]. Activating mutations in PIK3CA have been detected in 4%–7% of NSCLCs, amplification in more than 30% of squamous cell carcinomas, and about 1% of adenocarcinomas. RICTOR amplification has been described in 10% of NSCLCs, and mutations in the tumor suppressor genes PTEN and STK11, which are negative regulators of mTOR signaling, have also been observed in squamous cell and adenocarcinomas [101–103]. Moreover, mTOR activation correlates with mutations in both KRAS and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and may serve as a resistance mechanism to treatment with EGFR inhibitors [104].

In our studies, we examined the p-mTOR, p-S6, and Rictor proteins in situ in primary lung adenocarcinomas and brain metastases. Increased p-mTOR, p-S6, and Rictor protein expressions were observed in more than 30% of primary adenocarcinomas and around 70% of brain metastases. Additionally, all studied markers (p-mTOR, p-S6, and Rictor) showed a stronger positivity in the majority of the brain metastases studied. In some cases, high p-mTOR levels were associated with low p-S6 and high Rictor expression, which characterized about 20% of primary lung adenocarcinomas and more than 50% of brain metastases. Further associations were found between higher stage and Rictor expression in primary adenocarcinomas and high Rictor and low p-S6 expression in solitary brain metastases. Comparing primary tumor and brain metastases samples from the same patient, we observed increased mTORC1 activity in metastases; in 60% of the cases, p-mTOR and p-S6 expression was increased in brain metastases, whereas in 40% of cases, Rictor expression was increased in brain metastases. These data highlight the presence and prognostic role of mTORC2 activity in this tumor type [45].

Among lung tumors of neuroendocrine origin, small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) is the most common, accounting for 15%–20% of all lung tumors [105]. In addition to mutations in the TP53 and RB1 genes and MYC amplification, genetic alterations affecting elements of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway (e.g., PIK3CA, PTEN, AKT2, AKT3, MTOR, and RICTOR) are common in SCLC. RICTOR amplification is the most common targetable genetic alteration in SCLC (6%–14%) [106]. Activation of the mTOR pathway in SCLC has been detected by immunohistochemistry for p-mTOR and p-S6 proteins [33], although less data are available on the activity, background, and significance of mTORC2.

Our RICTOR amplification studies were initiated in collaboration with the Mayo Clinic, and within the framework of this collaboration, we analyzed 100 samples from 92 SCLC patients. The presence of RICTOR amplification was confirmed by FISH. We detected RICTOR amplification in 15% of cases, 3% of our cases were equivocal, and 82% were negative. In these samples, we characterized Rictor and p-Akt levels by immunohistochemistry. Of the cases, 14% showed high, 23% moderate, 25% low Rictor expression, and 38% were negative. The expression of p-Akt was high in 16%, moderate in 26%, and low in 35% of the cases, whereas in 23% of the tested samples, we could not detect the presence of the protein. Statistical analyses showed that Rictor immunohistochemistry had a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 73%; p-Akt immunohistochemistry had a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 65% compared to RICTOR FISH results. The presence or absence of RICTOR amplification was not associated with the overall survival data of the patients. However, higher in situ expression of Rictor and p-Akt proteins was significantly associated with shorter overall survival [46].

A rare lung disease, lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), is caused by a loss-of-function mutation in the TSC1/2 gene, resulting in lung tissue damage through proliferation, growth, and invasion of LAM cells [107, 108]. The therapeutic relevance of mTORC1 activity and the expression of downstream markers of the mTOR signaling pathway (e.g., p-p70S6K, p-S6, p-4EBP1) have been demonstrated by immunohistochemical studies [109, 110].

With the help of the Mayo Clinic, 11 cases of LAM were involved in our studies. Most of these (91%) showed high p-S6 protein expression, demonstrating increased mTORC1 activity and supporting mTOR inhibitor treatments. In parallel, high levels of Rictor expression were detected in addition to p-S6 in more than half of the cases (55%). This observation also highlights the role of the potential activity of the mTORC2 complex in this disease, which may explain the ineffectiveness of mTORC1 inhibitors in certain cases. This study was the first to examine both mTORC1 and mTORC2 activity in human LAM samples, and in addition to previously reported mTORC1 hyperactivity, we have also demonstrated increased mTORC2 complex presence and activity. Further studies demonstrating mTORC2 hyperactivity may suggest using other dual mTORC1 and mTORC2 inhibitors or dual mTOR inhibitors to slow the progression of this rare disease [47].

Our studies support the importance of characterizing mTOR activity in a wide range of tumors, which may indicate the clinical need for the appropriate use of mTOR inhibitors. In these cases, we recommend the immunohistochemical analysis of at least 3-4 in situ tissue markers [e.g., p-mTOR, p-S6, Rictor, and p-Akt (Ser473)] to provide a good representation of mTORC1 and mTORC2 activity in tumor tissue. It is important to note that first-generation mTORC1 inhibitors may be ineffective in the presence of high Rictor and p-Akt (Ser473) expression, as tumor cells with high mTORC2 activity may survive despite the administration of specific mTORC1 inhibitors [111].

Targeted therapeutic options in the presence of mTOR hyperactivity and/or RICTOR amplification

Over the past decades, the efficacy of several PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling inhibitors has been investigated. Despite numerous clinical trials with inhibitors of this signaling pathway, therapeutic responses are often lower than expected; moreover, only a few new drugs have been introduced to treat various tumors. One possible reason for this could be an inadequate patient selection method and, in this context, the lack of reliable predictive markers. Sensitivity to mTOR inhibitors may be predicted by specific genetic abnormalities (e.g., PIK3CA mutation/amplification, PTEN loss-of-function mutation, AKT mutation, RICTOR amplification) or overexpression of the signaling pathway elements and their active targets (e.g., Rictor, p-S6, p-Akt). These markers can be well assessed at the tissue level, and their presence or absence should be evaluated/considered when designing targeted therapies before specific inhibitors are used [112, 113].

The best-known mTOR inhibitor, rapamycin (or sirolimus), also the eponymous inhibitor of mTOR kinase, was discovered by George Nogrady, a Hungarian-born bacteriologist, in the Chilean territory of Easter Island (Rapa Nui) in 1964 [114]. The compound was isolated as a microbial antibiotic and introduced as an immunosuppressant in 1975 [115]. Following the discovery of the specific target protein of rapamycin, mTOR kinase, allosteric mTOR inhibitors, rapamycin and its derivatives (rapalogs—everolimus, temsirolimus, etc.,) have been used with varying results in several types of tumors (e.g., breast, kidney, endocrine, central nervous system). Rapalogs inhibit the activity of mTORC1 by binding to the FRB domain of mTOR kinase through the FKBP12 protein. Due to the structural differences between the two complexes (see above), no direct effect of rapamycin is observed for the mTORC2 complex [111]. Further studies are needed to determine the possible impact of rapamycin on the mTORC2 complex.

In addition to rapalogs, double mTORC1 and mTORC2 inhibitors (e.g., CC-115, sapanisertib, vistusertib), as well as dual mTOR kinase and another signaling kinase (e.g., PI3K) inhibitors (e.g., gedatolisib, paxalisib, samatolisib) are currently under development. Other specific Akt inhibitors are also being tested (e.g., afuresertib, capivasertib, ipatasertib, MK-2206, TAS-117, triciribine, uprosertib) and are currently in phase II and III trials. Third-generation mTOR inhibitors (e.g., RapaLink-1) are also being developed for the treatment of various advanced cancers (e.g., renal, breast, mantle cell, and other high-grade lymphomas) [116]. Table 2 summarizes PI3K/Akt/mTOR inhibitors currently in use and development.

TABLE 2.

Classification, highest clinical phase, status, and application of PI3K/Akt/mTOR inhibitors in various tumor types based on the GlobalData database.

| Target | Drug Name | Tumor types | Highest phase and ID number of the clinical trial | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI3K inhibitors | ||||

| Non-subunit-specific PI3K inhibitor | AZD8186 | Solid Tumor | Phase II—NCT04001569 | Active |

| buparlisib (NVP-BKM120) | Head and Neck Cancer | Phase III—NCT04338399 | Active | |

| copanlisib | Lymphoma | — | Marketed | |

| duvelisib | Leukemia, Lymphoma | — | Marketed | |

| MEN1611 (CH5132799) | Colorectal Cancer | Phase II—NCT04495621 | Active | |

| tenalisib (RP6530) | Breast Cancer | Phase II—NCT05021900 | Active | |

| TQB-3525 | Breast Cancer, Endometrial Cancer, Leukemia, Lymphoma, Ovarian Cancer | Phase II—NCT04324879, NCT04355520, NCT04398953, NCT04610970, NCT04615468, NCT04808570, NCT04836663 | Active | |

| PI3Kα inhibitor | alpelisib | Breast Cancer | — | Marketed |

| CYH-33 (HHCYH-33) | Solid Tumor | Phase I—NCT04586335, NCT04856371 | Active | |

| inavolisib (GDC-0077) | Breast Cancer | Phase III—NCT04191499 | Active | |

| serabelisib (INK-1117) | Solid Tumor | Phase II—NCT04073680 | Active | |

| taselisib | Lymphoma, Myeloma, Solid Tumor | Phase II—NCT02465060 | Active | |

| PI3Kβ inhibitor | GSK2636771 | Lymphoma, Myeloma, Solid Tumor | Phase II—NCT02465060 | Active |

| PI3Kγ inhibitor | eganelisib (IPI-549) | Breast Cancer, Kidney Cancer | Phase II—NCT03961698 | Active |

| PI3Kδ inhibitor | amdizalisib (HMPL-689) | Lymphoma | Phase II—NCT04849351 | Active |

| idelalisib | Leukemia, Lymphoma | — | Marketed | |

| IOA-244 | Lymphoma, Melanoma, Solid Tumor | Phase I—NCT04328844 | Active | |

| linperlisib (YY-20394) | Lymphoma | Phase II—NCT04370405, NCT04379167, NCT04500561, NCT04705090, NCT04948788 | Active | |

| parsaclisib (INCB50465) | Lymphoma, Myelofibrosis | Phase III—NCT04551053, NCT04551066, NCT04796922, NCT04849715 | Active | |

| SHC014748 (SH-748) | Lymphoma | Phase II—NCT04431089, NCT04470141 | Active | |

| umbralisib | Lymphoma | - | Marketed | |

| zandelisib (PWT-143) | Lymphoma | Phase III—NCT04745832 | Active | |

| Various targets | AMG319 (ACP-319), apitolisib, AZD-8835, bimiralisib (PQR309), dactolisib, dezapelisib (NCB-040093), nemiralisib (GSK2269557), pictilisib (GDC-0941), pilaralisib, SAR260301, seletalisib (UCB-5857), SF1126, sonolisib, voxtalisib, ZSTK-474etc. | Inactive/Discontinued | ||

| mTOR inhibitors | ||||

| Allosteric mTOR inhibitor | everolimus | Breast Cancer, Central Nervous System Tumor, Endocrine Tumor, Kidney Cancer | — | Marketed |

| sirolimus | Lymphangioleiomyomatosis | — | Marketed | |

| temsirolimus | Kidney Cancer | — | Marketed | |

| mTOR-kinase inhibitor (inhibits both mTORC1 and mTORC2) | CC-115 | Central Nervous System Tumor | Phase II—NCT02977780 | Active |

| onatasertib (ATG-008) | Solid Tumor | Phase II—NCT03591965, NCT04337463, NCT04518137, NCT04998760 | Active | |

| sapanisertib (MLN0128) | Lymphoma, Myeloma, Solid Tumor | Phase II—NCT02465060 | Active | |

| vistusertib | Lung Cancer | Phase II—NCT02664935, NCT03334617 | Active | |

| Various targets | apitolisib, AZD8055, bimiralisib (PQR309), dactolisib, ridaforolimus (Deforolimus, MK-8669), SF1126, voxtalisibetc. | Inactive/Discontinued | ||

| Akt inhibitors | ||||

| Pan-Akt | afuresertib | Ovarian Cancer, Prostate Cancer | Phase II—NCT04060394, NCT04374630 | Active |

| capivasertib | Breast Cancer, Prostate Cancer | Phase III—NCT03997123, NCT04305496, NCT04493853, NCT04862663 | Active | |

| ipatasertib | Breast Cancer, Prostate Cancer | Phase III—NCT03072238, NCT03337724, NCT04060862, NCT04177108, NCT04650581 | Active | |

| MK-2206 | Breast Cancer, Lung Cancer, Thymoma | Phase II—NCT01042379, NCT01306045 | Active | |

| TAS-117 | Solid Tumor | Phase II—NCT04770246 | Active | |

| triciribine (PTX-200) | Leukemia | Phase II—NCT02930109 | Active | |

| uprosertib | Myeloma, Solid Tumor | Phase II—NCT01902173, NCT01989598 | Active | |

| Various targets | COTI-2, LY-2503029, perifosineetc. | Inactive/Discontinued | ||

| Dual inhibitors | ||||

| PI3K, mTOR dual inhibitor | gedatolisib | Breast Cancer | Phase II—NCT03698383, NCT03911973 | Active |

| paxalisib | Central Nervous System Tumor | Phase III—NCT03970447 | Active | |

| samotolisib | Lymphoma, Solid Tumor | Phase II—NCT03155620, NCT03213678 | Active | |

Developing potent and highly selective small molecules specific to the mTORC2 complex while preserving mTORC1 activity remains challenging. Among the specific inhibitors of mTORC2, only a few inhibitors based primarily on siRNA technology (e.g., Rictor si-NP, JR-AB2-011) are under preclinical testing [64, 117].

Despite the association between PI3K/Akt/mTOR hyperactivation and adverse prognosis, the efficacy of mTOR inhibitors used as monotherapy is very low, as is the case for most targeted therapeutic agents. However, combining mTOR inhibitors with other targeted therapies or conventional chemotherapy/radiotherapy may help sensitize different agents and overcome resistance mechanisms to treatment. This type of combination therapy is also being developed for a wide range of malignancies (Table 3) [118]. However, the administration of these mTOR inhibitor combination therapies can also be limited by adverse effects and/or severe individual side effects that require very careful management by oncologists [119].

TABLE 3.

Ongoing therapies in combination with mTOR inhibitors and their highest clinical trial phase in various tumor types based on the GlobalData database.

| Tumor types | Therapy | Highest phase and ID number of the clinical trial |

|---|---|---|

| Breast Tumors | ||

| Marketed: Metastatic, hormone receptor+/HER2− Breast Cancer (everolimus) | ||

| HER2+ (hormone receptor−/HER2+) Breast Cancer | chemotherapy + inetetamab + sirolimus | Phase III—NCT04736589 |

| Luminal A (hormone receptor+/HER2−) Breast Cancer | AZD2014/everolimus + fulvestrant | Phase II—NCT02216786 |

| everolimus + paclitaxel | Phase II—NCT04355858 | |

| Triple-Negative Breast Cancer | AZD2014 + AZD6244 (MEKI) | Phase I/II — NCT02583542 |

| bevacizumab + doxorubicin + everolimus | Phase II—NCT02456857 | |

| AZD6244 + temsirolimus | Phase I—NCT00600496 | |

| Central Nervous System Tumors | ||

| Marketed: Astrocytoma (everolimus) | ||

| perifosine + temsirolimus | Phase I—NCT02238496 | |

| cyclophosphamide + dasatinib + temsirolimus | Phase I—NCT02389309 | |

| temsirolimus + vorinostat | Phase I—NCT02420613 | |

| irinotecan + nab-rapamycin + temozolomide | Phase I—NCT02975882 | |

| everolimus + trametinib | Phase I—NCT04485559 | |

| celecoxib + cyclophosphamide + etoposide + sirolimus | Phase II—NCT02574728 | |

| nab-rapamycin + standard therapy | Phase II—NCT03463265 | |

| Digestive System Tumors | ||

| Colorectal Cancer | AZD6244 + temsirolimus | Phase I—NCT00600496 |

| bevacizumab + FOLFOX6 + nab-rapamycin | Phase I/II—NCT03439462 | |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | everolimus + lenvatinib + trametinib | Phase II—NCT04803318 |

| Pancreatic Cancer | gedatolisib + palbociclib | Phase I — NCT03065062 |

| Head and Neck Tumors | ||

| gedatolisib + palbociclib | Phase I—NCT03065062 | |

| Neuroendocrine Tumors | ||

| Marketed: Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Lungs, Pancreas, or Intestines (everolimus) | ||

| Neurofibromatosis | PLX3397 (MTKI) + sirolimus | Phase I/II—NCT02584647 |

| selumetinib (MEKI) + sirolimus | Phase II—NCT03433183 | |

| bevacizumab + everolimus + octreotide acetate | Phase II—NCT01229943 | |

| everolimus + lenvatinib | Phase II—NCT03950609 | |

| Other Tumors | ||

| Advanced Tumor | sirolimus/everolimus/temsirolimus + vorinostat | Phase I—NCT01087554 |

| bevacizumab + carboplatin/sorafenib/paclitaxel + temsirolimus | Phase I—NCT01187199 | |

| everolimus + vandetanib | Phase I—NCT01582191 | |

| ceritinib + everolimus | Phase I—NCT02321501 | |

| cemiplimab + sirolimus/everolimus + prednisone | Phase I—NCT04339062 | |

| Hepatoblastoma | chemotherapy + temsirolimus | Phase III—NCT00980460 |

| Neuroblastoma | irinotecan + temozolomide + temsirolimus | Phase II—NCT01767194 |

| Solid Tumor | ixabepilone + temsirolimus | Phase I—NCT01375829 |

| cyclophosphamide + dasatinib + temsirolimus | Phase I—NCT02389309 | |

| bevacizumab + cyclophosphamide + temsirolimus + valproát | Phase I—NCT02446431 | |

| irinotecan + nab-rapamycin + temozolomide | Phase I—NCT02975882 | |

| gedatolisib + palbociclib | Phase I—NCT03065062 | |

| epacadostat + sirolimus | Phase I—NCT03217669 | |

| celecoxib + cyclophosphamide + etoposide + sirolimus | Phase II—NCT02574728 | |

| everolimus + lenvatinib + trametinib | Phase II—NCT04803318 | |

| Vascular Tumor | prednisolone + sirolimus | Phase II—NCT03188068 |

| Skin Tumors | ||

| Melanoma | AZD6244 + temsirolimus | Phase I—NCT00600496 |

| Soft Tissue and Bone Tumors | ||

| chemotherapy + everolimus + temsirolimus | Phase I—NCT04199026 | |

| nab-rapamycin + pazopanib hydrochloride | Phase I/II—NCT03660930 | |

| everolimus + ribociclib | Phase II—NCT03114527 | |

| chemotherapy + temsirolimus | Phase III—NCT02567435 | |

| Thoracic Tumors | ||

| Marketed: Sporadic Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (sirolimus) | ||

| Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | gedatolisib + palbociclib | Phase I—NCT03065062 |

| epacadostat + sirolimus | Phase I—NCT03217669 | |

| durvalumab + sirolimus | Phase I—NCT04348292 | |

| AZD2014 + AZD6244 (MEKI) | Phase I/II—NCT02583542 | |

| Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer + Small Cell Lung Cancer | AZD6244 + temsirolimus | Phase I—NCT00600496 |

| auranofin + sirolimus | Phase I/II—NCT01737502 | |

| Tumors of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues | ||

| Marketed: Mantle Cell Lymphoma (temsirolimus) | ||

| Hodgkin’s Lymphoma | everolimus + itacitinib | Phase I/II—NCT03697408 |

| Leukemia | decitabine + sirolimus | Phase I/II—NCT02109744 |

| azacitidine + sirolimus | Phase II—NCT01869114 | |

| clofarabine + melphalan + sirolimus + tacrolimus | Phase II—NCT01885689 | |

| Urinary and Male Genital Tumors | ||

| Marketed: Metastatic Kidney Cancer (everolimus, temsirolimus) | ||

| Kidney Cancer | AZD6244 + temsirolimus | Phase I—NCT00600496 |

| DFF332 (HIF2αI) + everolimus | Phase I—NCT04895748 | |

| sunitinib + temsirolimus | Phase II—NCT01517243 | |

| everolimus + lenvatinib | Phase I—NCT03324373 | |

| Phase II—NCT05012371 | ||

| anastrozol + AZD2014 | Phase I/II—NCT02730923 | |

| carboplatin + paclitaxel + temsirolimus | Phase II—NCT00977574 | |

| everolimus + levonorgestrel | Phase II—NCT02397083 | |

| everolimus + letrozole + ribociclib | Phase II—NCT03008408 | |

| auranofin + sirolimus | Phase II—NCT03456700 | |

| ATG008/ATG010 | Phase II—NCT04998760 | |

Future perspectives

Advances in personalized therapies and the increasing availability of molecular genetic data on malignancies, including our findings of mTORC1 and mTORC2 activity and RICTOR amplification in various tumors, highlight the importance of validated targets in common and rare malignancies. The efficacy of targeted therapies often fails to deliver the expected results due to inadequate patient selection. In a biomarker-driven umbrella study, patients were selected based on RICTOR amplification, demonstrating a promising strategy for personalized therapies by selecting patients most likely to respond to targeted treatments. In this clinical trial, two of the four SCLC patients treated with a vistusertib (dual mTORC1 and mTORC2 inhibitor) showed an increase in survival of almost 1 year [120].

In our work, we have developed a marker panel to determine tissue characteristics of mTOR activity in biopsy specimens, patient materials, and cell lines. Our results and other molecular findings will hopefully support and optimize future therapeutic decisions.

mTOR hyperactivity can be a targeted genetic alteration in different tumor types. In our studies, we present our findings on the activity of both complexes and the characterization and prognostic role of mTORC2 complex hyperactivity. In the future, we intend to investigate further the significance of mTOR hyperactivity and RICTOR amplification in several malignancies. Expanding next-generation sequencing into routine diagnostics will facilitate more accurate oncogenic and tumor suppressor gene alterations mapping. Molecular pathology results and molecular genetics data will become widely available, which may help to identify mutations affecting mTOR activity. This will also help to determine the importance of specific mutations in rare tumor types.

In summary, several third-generation PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway inhibitors are already developing, and some of these are in clinical trials. Only a few inhibitors have been approved for treating various cancers compared to the enormous amount of research and money spent on their development. To increase this number and to achieve clinical translation of more mTOR inhibitors or other targeted inhibitors into personalized therapies, it is essential to identify predictive markers that can help therapeutic decision-making. In conclusion, for biomarker-driven patient selection, it is crucial to develop agents that are as effective as possible while maintaining a good safety profile and use rational drug combinations that improve quality of life and may be effective in overcoming primary or acquired resistance.

Footnotes

The figures in this review (Figures 1, 4, and 6) were edited using BioRender (https://biorender.com) under license from the Department of Pathology and Experimental Cancer Research, Semmelweis University.

Funding Statement

A recent review has been funded by the National Research, Development and Innovation Office of Hungary (NKFIH); TKP2021-EGA-24, NKFI-K-142799.

Author contributions

All authors (DS, DM, GP, TD, FS, RM, VV, NN, GP, JP, IK, and AS) participated in the design and review of the manuscript. AS supervised the literature review and manuscript preparation. DS and IK wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Saxton RA, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth, metabolism, and disease. Cell (2017) 168:960–76. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell (2006) 124:471–84. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liu GY, Sabatini DM. mTOR at the nexus of nutrition, growth, ageing and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cel Biol (2020) 4:183–203. 10.1038/s41580-019-0199-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fu W, Hall MN. Regulation of mTORC2 signaling. Genes (Basel) (2020) 11:1045. 10.3390/genes11091045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sebestyén A, Dankó T, Sztankovics D, Moldvai D, Raffay R, Cervi C, et al. The role of metabolic ecosystem in cancer progression - metabolic plasticity and mTOR hyperactivity in tumor tissues. Cancer Metastasis Rev (2021) 40:989–1033. 10.1007/s10555-021-10006-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yamaguchi H, Kawazu M, Yasuda T, Soda M, Ueno T, Kojima S, et al. Transforming somatic mutations of mammalian target of rapamycin kinase in human cancer. Cancer Sci (2015) 106:1687–92. 10.1111/cas.12828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grabiner BC, Nardi V, Birsoy K, Possemato R, Shen K, Sinha S, et al. A diverse array of cancer-associated MTOR mutations are hyperactivating and can predict rapamycin sensitivity. Cancer Discov (2014) 4:554–63. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wagle N, Grabiner BC, Van Allen EM, Amin-Mansour A, Taylor-Weiner A, Rosenberg M, et al. Response and acquired resistance to everolimus in anaplastic thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med (2014) 371:1426–33. 10.1056/NEJMoa1403352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Menon S, Manning BD. Common corruption of the mTOR signaling network in human tumors. Oncogene (2008) 27(Suppl. 2(0 2)):S43–51. 10.1038/onc.2009.352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eng CP, Sehgal SN, Vézina C. Activity of rapamycin (AY-22,989) against transplanted tumors. J Antibiot (1984) 37:1231–7. 10.7164/antibiotics.37.1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Choe G, Horvath S, Cloughesy TF, Crosby K, Seligson D, Palotie A, et al. Analysis of the phosphatidylinositol 3'-kinase signaling pathway in glioblastoma patients in vivo . Cancer Res (2003) 63:2742–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhou X, Tan M, Stone Hawthorne V, Klos KS, Lan KH, Yang Y, et al. Activation of the Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin/4E-BP1 pathway by ErbB2 overexpression predicts tumor progression in breast cancers. Clin Cancer Res (2004) 10:6779–88. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nathan CO, Amirghahari N, Abreo F, Rong X, Caldito G, Jones ML, et al. Overexpressed eIF4E is functionally active in surgical margins of head and neck cancer patients via activation of the Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway. Clin Cancer Res (2004) 10:5820–7. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sahin F, Kannangai R, Adegbola O, Wang J, Su G, Torbenson M. mTOR and P70 S6 kinase expression in primary liver neoplasms. Clin Cancer Res (2004) 10:8421–5. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Balsara BR, Pei J, Mitsuuchi Y, Page R, Klein-Szanto A, Wang H, et al. Frequent activation of AKT in non-small cell lung carcinomas and preneoplastic bronchial lesions. Carcinogenesis (2004) 25:2053–9. 10.1093/carcin/bgh226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xu G, Zhang W, Bertram P, Zheng XF, McLeod H. Pharmacogenomic profiling of the PI3K/PTEN-AKT-mTOR pathway in common human tumors. Int J Oncol (2004) 24:893–900. 10.3892/ijo.24.4.893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nozawa H, Watanabe T, Nagawa H. Phosphorylation of ribosomal p70 S6 kinase and rapamycin sensitivity in human colorectal cancer. Cancer Lett (2007) 251:105–13. 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lin F, Zhang PL, Yang XJ, Prichard JW, Lun M, Brown RE. Morphoproteomic and molecular concomitants of an overexpressed and activated mTOR pathway in renal cell carcinomas. Ann Clin Lab Sci (2006) 36:283–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kremer CL, Klein RR, Mendelson J, Browne W, Samadzedeh LK, Vanpatten K, et al. Expression of mTOR signaling pathway markers in prostate cancer progression. Prostate (2006) 66:1203–12. 10.1002/pros.20410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu Y, Hidayat S, Su WH, Deng X, Yu DH, Yu BZ. Expression and activity of mTOR and its substrates in different cell cycle phases and in oral squamous cell carcinomas of different malignant grade. Cell Biochem Funct (2007) 25:45–53. 10.1002/cbf.1332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boone J, Ten Kate FJ, Offerhaus GJ, van Diest PJ, Rinkes IH, van Hillegersberg R. mTOR in squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus: a potential target for molecular therapy? J Clin Pathol (2008) 61:909–13. 10.1136/jcp.2008.055772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Karbowniczek M, Spittle CS, Morrison T, Wu H, Henske EP. mTOR is activated in the majority of malignant melanomas. J Invest Dermatol (2008) 128:980–7. 10.1038/sj.jid.5701074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pham NA, Schwock J, Iakovlev V, Pond G, Hedley DW, Tsao MS. Immunohistochemical analysis of changes in signaling pathway activation downstream of growth factor receptors in pancreatic duct cell carcinogenesis. BMC Cancer (2008) 8:43. 10.1186/1471-2407-8-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Feng W, Duan X, Liu J, Xiao J, Brown RE. Morphoproteomic evidence of constitutively activated and overexpressed mTOR pathway in cervical squamous carcinoma and high grade squamous intraepithelial lesions. Int J Clin Exp Pathol (2009) 2:249–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yu G, Wang J, Chen Y, Wang X, Pan J, Li G, et al. Overexpression of phosphorylated mammalian target of rapamycin predicts lymph node metastasis and prognosis of Chinese patients with gastric cancer. Clin Cancer Res (2009) 15:1821–9. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leseux L, Hamdi SM, Al Saati T, Capilla F, Recher C, Laurent G, et al. Syk-dependent mTOR activation in follicular lymphoma cells. Blood (2006) 108:4156–62. 10.1182/blood-2006-05-026203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Peponi E, Drakos E, Reyes G, Leventaki V, Rassidakis GZ, Medeiros LJ. Activation of mammalian target of rapamycin signaling promotes cell cycle progression and protects cells from apoptosis in mantle cell lymphoma. Am J Pathol (2006) 169:2171–80. 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Follo MY, Mongiorgi S, Bosi C, Cappellini A, Finelli C, Chiarini F, et al. The Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin signal transduction pathway is activated in high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes and influences cell survival and proliferation. Cancer Res (2007) 67:4287–94. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Marzec M, Liu X, Kasprzycka M, Witkiewicz A, Raghunath PN, El-Salem M, et al. IL-2- and IL-15-induced activation of the rapamycin-sensitive mTORC1 pathway in malignant CD4+ T lymphocytes. Blood (2008) 111:2181–9. 10.1182/blood-2007-06-095182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhao MY, Auerbach A, D'Costa AM, Rapoport AP, Burger AM, Sausville EA, et al. Phospho-p70S6K/p85S6K and cdc2/cdk1 are novel targets for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma combination therapy. Clin Cancer Res (2009) 15:1708–20. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mora J, Rodríguez E, de Torres C, Cardesa T, Ríos J, Hernández T, et al. Activated growth signaling pathway expression in Ewing sarcoma and clinical outcome. Pediatr Blood Cancer (2012) 58:532–8. 10.1002/pbc.23348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Iżycka-Świeszewska E, Drożyńska E, Rzepko R, Kobierska-Gulida G, Grajkowska W, Perek D, et al. Analysis of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling pathway in high risk neuroblastic tumours. Pol J Pathol (2010) 61:192–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schmid K, Bago-Horvath Z, Berger W, Haitel A, Cejka D, Werzowa J, et al. Dual inhibition of EGFR and mTOR pathways in small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer (2010) 103:622–8. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu J, Brown RE. Morphoproteomics demonstrates activation of mTOR pathway in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: a preliminary observation. Ann Clin Lab Sci (2010) 40:211–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McCampbell AS, Harris HA, Crabtree JS, Winneker RC, Walker CL, Broaddus RR. Loss of inhibitory insulin receptor substrate-1 phosphorylation is an early event in mammalian target of rapamycin-dependent endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) (2010) 3:290–300. 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tickoo SK, Milowsky MI, Dhar N, Dudas ME, Gallagher DJ, Al-Ahmadie H, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor and mammalian target of rapamycin pathway markers in urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: possible therapeutic implications. BJU Int (2011) 107:844–9. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09517.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sápi Z, Füle T, Hajdu M, Matolcsy A, Moskovszky L, Márk A, et al. The activated targets of mTOR signaling pathway are characteristic for PDGFRA mutant and wild-type rather than KIT mutant GISTs. Diagn Mol Pathol (2011) 20:22–33. 10.1097/PDM.0b013e3181eb931b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sebestyén A, Sticz TB, Márk A, Hajdu M, Timár B, Nemes K, et al. Activity and complexes of mTOR in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas--a tissue microarray study. Mod Pathol (2012) 25:1623–8. 10.1038/modpathol.2012.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Suzuki S, Dobashi Y, Minato H, Tajiri R, Yoshizaki T, Ooi A. EGFR and HER2-Akt-mTOR signaling pathways are activated in subgroups of salivary gland carcinomas. Virchows Arch (2012) 461:271–82. 10.1007/s00428-012-1282-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nemes K, Sebestyén A, Márk A, Hajdu M, Kenessey I, Sticz T, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activity dependent phospho-protein expression in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). PLoS One (2013) 8:e59335. 10.1371/journal.pone.0059335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Leal P, García P, Sandoval A, Letelier P, Brebi P, Ili C, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of phospho-mTOR is associated with poor prognosis in patients with gallbladder adenocarcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med (2013) 137:552–7. 10.5858/arpa.2012-0032-OA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Márk Á, Hajdu M, Váradi Z, Sticz TB, Nagy N, Csomor J, et al. Characteristic mTOR activity in Hodgkin-lymphomas offers a potential therapeutic target in high risk disease--a combined tissue microarray, in vitro and in vivo study. BMC Cancer (2013) 13:250. 10.1186/1471-2407-13-250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pócza T, Sebestyén A, Turányi E, Krenács T, Márk A, Sticz TB, et al. mTOR pathway as a potential target in a subset of human medulloblastoma. Pathol Oncol Res (2014) 20:893–900. 10.1007/s12253-014-9771-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sticz T, Molnár A, Márk Á, Hajdu M, Nagy N, Végső G, et al. mTOR activity and its prognostic significance in human colorectal carcinoma depending on C1 and C2 complex-related protein expression. J Clin Pathol (2017) 70:410–6. 10.1136/jclinpath-2016-203913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Krencz I, Sebestyén A, Fábián K, Márk Á, Moldvay J, Khoor A, et al. Expression of mTORC1/2-related proteins in primary and brain metastatic lung adenocarcinoma. Hum Pathol (2017) 62:66–73. 10.1016/j.humpath.2016.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Krencz I, Sebestyen A, Papay J, Lou Y, Lutz GF, Majewicz TL, et al. Correlation between immunohistochemistry and RICTOR fluorescence in situ hybridization amplification in small cell lung carcinoma. Hum Pathol (2019) 93:74–80. 10.1016/j.humpath.2019.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Krencz I, Sebestyen A, Papay J, Jeney A, Hujber Z, Burger CD, et al. In situ analysis of mTORC1/2 and cellular metabolism-related proteins in human Lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Hum Pathol (2018) 79:199–207. 10.1016/j.humpath.2018.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Petővári G, Dankó T, Tőkés AM, Vetlényi E, Krencz I, Raffay R, et al. In situ metabolic characterisation of breast cancer and its potential impact on therapy. Cancers (Basel) (2020) 12:2492. 10.3390/cancers12092492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Petővári G, Dankó T, Krencz I, Hujber Z, Rajnai H, Vetlényi E, et al. Inhibition of metabolic shift can decrease therapy resistance in human high-grade glioma cells. Pathol Oncol Res (2020) 26:23–33. 10.1007/s12253-019-00677-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Felkai L, Krencz I, Kiss DJ, Nagy N, Petővári G, Dankó T, et al. Characterization of mTOR activity and metabolic profile in pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancers (Basel) (2020) 12:1947. 10.3390/cancers12071947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Krencz I, Vetlényi E, Dankó T, Petővári G, Moldvai D, Sztankovics D, et al. Metabolic adaptation as potential target in papillary renal cell carcinomas based on their in situ metabolic characteristics. Int J Mol Sci (2022) 23:10587. 10.3390/ijms231810587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mohás A, Krencz I, Váradi Z, Arató G, Felkai L, Kiss DJ, et al. In situ analysis of mTORC1/C2 and metabolism-related proteins in pediatric osteosarcoma. Pathol Oncol Res (2022) 28:1610231. 10.3389/pore.2022.1610231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hujber Z, Petővári G, Szoboszlai N, Dankó T, Nagy N, Kriston C, et al. Rapamycin (mTORC1 inhibitor) reduces the production of lactate and 2-hydroxyglutarate oncometabolites in IDH1 mutant fibrosarcoma cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res (2017) 36:74. 10.1186/s13046-017-0544-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Shaw RJ, Cantley LC. Ras, PI(3)K and mTOR signalling controls tumour cell growth. Nature (2006) 441:424–30. 10.1038/nature04869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gkountakos A, Pilotto S, Mafficini A, Vicentini C, Simbolo M, Milella M, et al. Unmasking the impact of Rictor in cancer: novel insights of mTORC2 complex. Carcinogenesis (2018) 39:971–80. 10.1093/carcin/bgy086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Krencz I, Sebestyen A, Khoor A. mTOR in lung neoplasms. Pathol Oncol Res (2020) 26:35–48. 10.1007/s12253-020-00796-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Jiang WJ, Feng RX, Liu JT, Fan LL, Wang H, Sun GP. RICTOR expression in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and its clinical significance. Med Oncol (2017) 34:32. 10.1007/s12032-017-0894-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wazir U, Newbold RF, Jiang WG, Sharma AK, Mokbel K. Prognostic and therapeutic implications of mTORC1 and Rictor expression in human breast cancer. Oncol Rep (2013) 29:1969–74. 10.3892/or.2013.2346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Driscoll DR, Karim SA, Sano M, Gay DM, Jacob W, Yu J, et al. mTORC2 signaling drives the development and progression of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res (2016) 76:6911–23. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Joechle K, Guenzle J, Hellerbrand C, Strnad P, Cramer T, Neumann UP, et al. Role of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2 in primary and secondary liver cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol (2021) 13:1632–47. 10.4251/wjgo.v13.i11.1632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Jebali A, Battistella M, Lebbé C, Dumaz N. RICTOR affects melanoma tumorigenesis and its resistance to targeted therapy. Biomedicines (2021) 9:1498. 10.3390/biomedicines9101498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Morrison Joly M, Hicks DJ, Jones B, Sanchez V, Estrada MV, Young C, et al. Rictor/mTORC2 drives progression and therapeutic resistance of HER2-amplified breast cancers. Cancer Res (2016) 76:4752–64. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-3393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Morrison Joly M, Williams MM, Hicks DJ, Jones B, Sanchez V, Young CD, et al. Two distinct mTORC2-dependent pathways converge on Rac1 to drive breast cancer metastasis. Breast Cancer Res (2017) 19:74. 10.1186/s13058-017-0868-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Werfel TA, Wang S, Jackson MA, Kavanaugh TE, Joly MM, Lee LH, et al. Selective mTORC2 inhibitor therapeutically blocks breast cancer cell growth and survival. Cancer Res (2018) 78:1845–58. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-2388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zhang F, Zhang X, Li M, Chen P, Zhang B, Guo H, et al. mTOR complex component Rictor interacts with PKCzeta and regulates cancer cell metastasis. Cancer Res (2010) 70:9360–70. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Liu Y, Lu Y, Li A, Celiku O, Han S, Qian M, et al. mTORC2/Rac1 pathway predisposes cancer aggressiveness in IDH1-mutated glioma. Cancers (Basel) (2020) 12:787. 10.3390/cancers12040787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Alvarenga AW, Machado LE, Rodrigues BR, Lupinacci FC, Sanemastu P, Matta E, et al. Evaluation of Akt and RICTOR expression levels in astrocytomas of all grades. J Histochem Cytochem (2017) 65:93–103. 10.1369/0022155416675850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Petővári G, Hujber Z, Krencz I, Dankó T, Nagy N, Tóth F, et al. Targeting cellular metabolism using rapamycin and/or doxycycline enhances anti-tumour effects in human glioma cells. Cancer Cel Int (2018) 18:211. 10.1186/s12935-018-0710-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Akgül S, Li Y, Zheng S, Kool M, Treisman DM, Li C, et al. Opposing tumor-promoting and -suppressive functions of rictor/mTORC2 signaling in adult glioma and pediatric SHH medulloblastoma. Cell Rep (2018) 24:463–78. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.06.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Gulhati P, Bowen KA, Liu J, Stevens PD, Rychahou PG, Chen M, et al. mTORC1 and mTORC2 regulate EMT, motility, and metastasis of colorectal cancer via RhoA and Rac1 signaling pathways. Cancer Res (2011) 71:3246–56. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Wen FF, Li XY, Li YY, He S, Xu XY, Liu YH, et al. Expression of Raptor and Rictor and their relationships with angiogenesis in colorectal cancer. Neoplasma (2020) 67:501–8. 10.4149/neo_2020_190705N597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wang L, Qi J, Yu J, Chen H, Zou Z, Lin X, et al. Overexpression of Rictor protein in colorectal cancer is correlated with tumor progression and prognosis. Oncol Lett (2017) 14:6198–202. 10.3892/ol.2017.6936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Bang H, Ahn S, Ji Kim E, Kim ST, Park HY, Lee J, et al. Correlation between RICTOR overexpression and amplification in advanced solid tumors. Pathol Res Pract (2020) 216:152734. 10.1016/j.prp.2019.152734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kim ST, Kim SY, Klempner SJ, Yoon J, Kim N, Ahn S, et al. Rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR (RICTOR) amplification defines a subset of advanced gastric cancer and is sensitive to AZD2014-mediated mTORC1/2 inhibition. Ann Oncol (2017) 28:547–54. 10.1093/annonc/mdw669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Cao RZ, Min L, Liu S, Tian RY, Jiang HY, Liu J, et al. Rictor activates cav 1 through the Akt signaling pathway to inhibit the apoptosis of gastric cancer cells. Front Oncol (2021) 11:641453. 10.3389/fonc.2021.641453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kaibori M, Shikata N, Sakaguchi T, Ishizaki M, Matsui K, Iida H, et al. Influence of rictor and raptor expression of mTOR signaling on long-term outcomes of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci (2015) 60:919–28. 10.1007/s10620-014-3417-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Villanueva A, Chiang DY, Newell P, Peix J, Thung S, Alsinet C, et al. Pivotal role of mTOR signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology (2008) 135:1972–83. 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Schmidt KM, Hellerbrand C, Ruemmele P, Michalski CW, Kong B, Kroemer A, et al. Inhibition of mTORC2 component RICTOR impairs tumor growth in pancreatic cancer models. Oncotarget (2017) 8:24491–505. 10.18632/oncotarget.15524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Wen SY, Li CH, Zhang YL, Bian YH, Ma L, Ge QL, et al. Rictor is an independent prognostic factor for endometrial carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol (2014) 7:2068–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Naruse T, Yanamoto S, Okuyama K, Yamashita K, Omori K, Nakao Y, et al. Therapeutic implication of mTORC2 in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol (2017) 65:23–32. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ruicci KM, Plantinga P, Pinto N, Khan MI, Stecho W, Dhaliwal SS, et al. Disruption of the RICTOR/mTORC2 complex enhances the response of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells to PI3K inhibition. Mol Oncol (2019) 13:2160–77. 10.1002/1878-0261.12558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Kawasaki G, Naruse T, Furukawa K, Umeda M. mTORC1 and mTORC2 expression levels in oral squamous cell carcinoma: an immunohistochemical and clinicopathological study. Anticancer Res (2018) 38:1623–8. 10.21873/anticanres.12393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kondo S, Hirakawa H, Ikegami T, Uehara T, Agena S, Uezato J, et al. Raptor and rictor expression in patients with human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer (2021) 21:87. 10.1186/s12885-021-07794-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Zhang X, Wang X, Xu T, Zhong S, Shen Z. Targeting of mTORC2 may have advantages over selective targeting of mTORC1 in the treatment of malignant pheochromocytoma. Tumour Biol (2015) 36:5273–81. 10.1007/s13277-015-3187-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Schmidt KM, Dietrich P, Hackl C, Guenzle J, Bronsert P, Wagner C, et al. Inhibition of mTORC2/RICTOR impairs melanoma hepatic metastasis. Neoplasia (2018) 20:1198–208. 10.1016/j.neo.2018.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Gibault L, Ferreira C, Pérot G, Audebourg A, Chibon F, Bonnin S, et al. From PTEN loss of expression to RICTOR role in smooth muscle differentiation: complex involvement of the mTOR pathway in leiomyosarcomas and pleomorphic sarcomas. Mod Pathol (2012) 25:197–211. 10.1038/modpathol.2011.163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Okada T, Lee AY, Qin LX, Agaram N, Mimae T, Shen Y, et al. Integrin-α10 dependency identifies RAC and RICTOR as therapeutic targets in high-grade myxofibrosarcoma. Cancer Discov (2016) 6:1148–65. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-1481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Ross JS, Wang K, Elkadi OR, Tarasen A, Foulke L, Sheehan CE, et al. Next-generation sequencing reveals frequent consistent genomic alterations in small cell undifferentiated lung cancer. J Clin Pathol (2014) 67:772–6. 10.1136/jclinpath-2014-202447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Umemura S, Mimaki S, Makinoshima H, Tada S, Ishii G, Ohmatsu H, et al. Therapeutic priority of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in small cell lung cancers as revealed by a comprehensive genomic analysis. J Thorac Oncol (2014) 9:1324–31. 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Sakre N, Wildey G, Behtaj M, Kresak A, Yang M, Fu P, et al. RICTOR amplification identifies a subgroup in small cell lung cancer and predicts response to drugs targeting mTOR. Oncotarget (2017) 8:5992–6002. 10.18632/oncotarget.13362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Zeng Z, Sarbassov dos D, Samudio IJ, Yee KW, Munsell MF, Ellen Jackson C, et al. Rapamycin derivatives reduce mTORC2 signaling and inhibit AKT activation in AML. Blood (2007) 109:3509–12. 10.1182/blood-2006-06-030833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Zhuang J, Hawkins SF, Glenn MA, Lin K, Johnson GG, Carter A, et al. Akt is activated in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells and delivers a pro-survival signal: the therapeutic potential of Akt inhibition. Haematologica (2010) 95:110–8. 10.3324/haematol.2009.010272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Simioni C, Martelli AM, Zauli G, Melloni E, Neri LM. Targeting mTOR in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cells (2019) 8:190. 10.3390/cells8020190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Müller A, Zang C, Chumduri C, Dörken B, Daniel PT, Scholz CW. Concurrent inhibition of PI3K and mTORC1/mTORC2 overcomes resistance to rapamycin induced apoptosis by down-regulation of Mcl-1 in mantle cell lymphoma. Int J Cancer (2013) 133:1813–24. 10.1002/ijc.28206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Sahu D, Huan J, Wang H, Sahoo D, Casteel DE, Klemke RL, et al. Bladder cancer invasion is mediated by mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2-driven regulation of nitric oxide and invadopodia formation. Am J Pathol (2021) 191:2203–18. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2021.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Juengel E, Kim D, Makarević J, Reiter M, Tsaur I, Bartsch G, et al. Molecular analysis of sunitinib resistant renal cell carcinoma cells after sequential treatment with RAD001 (everolimus) or sorafenib. J Cel Mol Med (2015) 19:430–41. 10.1111/jcmm.12471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Sztankovics D, Krencz I, Moldvai D, Dankó T, Nagy Á, Nagy N, et al. Novel RICTOR amplification harbouring entities: FISH validation of RICTOR amplification in tumour tissue after next-generation sequencing. Sci Rep (2023) 13:19610. 10.1038/s41598-023-46927-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Tian T, Li X, Zhang J. mTOR signaling in cancer and mTOR inhibitors in solid tumor targeting therapy. Int J Mol Sci (2019) 20:755. 10.3390/ijms20030755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Dobashi Y, Watanabe Y, Miwa C, Suzuki S, Koyama S. Mammalian target of rapamycin: a central node of complex signaling cascades. Int J Clin Exp Pathol (2011) 4:476–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Chen B, Tan Z, Gao J, Wu W, Liu L, Jin W, et al. Hyperphosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 predicts unfavorable clinical survival in non-small cell lung cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res (2015) 34:126. 10.1186/s13046-015-0239-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Ekman S, Wynes MW, Hirsch FR. The mTOR pathway in lung cancer and implications for therapy and biomarker analysis. J Thorac Oncol (2012) 7:947–53. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31825581bd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Spoerke JM, O'Brien C, Huw L, Koeppen H, Fridlyand J, Brachmann RK, et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway alterations are associated with histologic subtypes and are predictive of sensitivity to PI3K inhibitors in lung cancer preclinical models. Clin Cancer Res (2012) 18:6771–83. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Szalai F, Sztankovics D, Krencz I, Moldvai D, Pápay J, Sebestyén A, et al. Rictor—a mediator of progression and metastasis in lung cancer. Cancers (2024) 16:543. 10.3390/cancers16030543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Conde E, Angulo B, Tang M, Morente M, Torres-Lanzas J, Lopez-Encuentra A, et al. Molecular context of the EGFR mutations: evidence for the activation of mTOR/S6K signaling. Clin Cancer Res (2006) 12:710–7. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Hendifar AE, Marchevsky AM, Tuli R. Neuroendocrine tumors of the lung: current challenges and advances in the diagnosis and management of well-differentiated disease. J Thorac Oncol (2017) 12:425–36. 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.11.2222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Krencz I, Sztankovics D, Danko T, Sebestyen A, Khoor A. Progression and metastasis of small cell lung carcinoma: the role of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway and metabolic alterations. Cancer Metastasis Rev (2021) 40:1141–57. 10.1007/s10555-021-10012-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Glasgow CG, Steagall WK, Taveira-Dasilva A, Pacheco-Rodriguez G, Cai X, El-Chemaly S, et al. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM): molecular insights lead to targeted therapies. Respir Med (2010) 104:S45–S58. 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Henske EP, McCormack FX. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis - a wolf in sheep's clothing. J Clin Invest (2012) 122:3807–16. 10.1172/JCI58709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Adachi K, Miki Y, Saito R, Hata S, Yamauchi M, Mikami Y, et al. Intracrine steroid production and mammalian target of rapamycin pathways in pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Hum Pathol (2015) 46:1685–93. 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Hayashi T, Kumasaka T, Mitani K, Okada Y, Kondo T, Date H, et al. Bronchial involvement in advanced stage lymphangioleiomyomatosis: histopathologic and molecular analyses. Hum Pathol (2016) 50:34–42. 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science (2005) 307:1098–101. 10.1126/science.1106148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Janku F, Yap TA, Meric-Bernstam F. Targeting the PI3K pathway in cancer: are we making headway? Nat Rev Clin Oncol (2018) 15:273–91. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Owonikoko TK, Khuri FR. Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway: biomarkers of success and tribulation. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book (2013) 10:e395–401. 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2013.33.e395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Hobby G, Clark R, Woywodt A. A treasure from a barren island: the discovery of rapamycin. Clin Kidney J (2022) 15:1971–2. 10.1093/ckj/sfac116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Sehgal SN, Baker H, Vézina C. Rapamycin (AY-22,989), a new antifungal antibiotic. II. Fermentation, isolation and characterization. J Antibiot (1975) 28:727–32. 10.7164/antibiotics.28.727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Mao B, Zhang Q, Ma L, Zhao DS, Zhao P, Yan P. Overview of research into mTOR inhibitors. Molecules (2022) 27:5295. 10.3390/molecules27165295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Guenzle J, Akasaka H, Joechle K, Reichardt W, Venkatasamy A, Hoeppner J, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of mTORC2 reduces migration and metastasis in melanoma. Int J Mol Sci (2020) 22:30. 10.3390/ijms22010030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Conciatori F, Ciuffreda L, Bazzichetto C, Falcone I, Pilotto S, Bria E, et al. mTOR cross-talk in cancer and potential for combination therapy. Cancers (Basel) (2018) 10:23. 10.3390/cancers10010023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]