Abstract

BACKGROUND

Sensory integration intervention is highly related to the child's effective interaction with the environment and the child's development. Currently, various sensory integration interventions are being applied, but research methodological problems are arising due to unsystematic protocols. This study aims to present the optimal intervention protocol by presenting scientific standards for sensory integration intervention through meta-analysis.

AIM

To prove the effectiveness of sensory integration therapy, examine the latest trend of sensory integration studies in Korea, and provide clinical evidence for sensory integration therapies.

METHODS

The database of Korean search engines, including RISS, KISS, and DBpia, was used to search for related literature published from 2001 to October 2020. The keywords, “Children”, “Sensory integration”, “Integrated sensory”, “Sensory-motor”, and “Sensory stimulation” were used in this search. Then, a meta-analysis was conducted on 24 selected studiesRISS, KISS, and DBpia, was used to search for related literature published from 2001 to October 2020. The keywords, “Children”, “Sensory integration”, “Integrated sensory”, “Sensory-motor”, and “Sensory stimulation” were used in this search. Then, a meta-analysis was conducted on 24 selected studies.

RESULTS

Sensory integration intervention has been proven effective in children with cerebral palsy, autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, developmental disorder, and intellectual disability in relation to the diagnosis of children. Regarding sensory integration therapies, 1:1 individual treatment with a therapist or a therapy session lasting for 40 min was most effective. In terms of dependent variables, sensory integration therapy effectively promoted social skills, adaptive behavior, sensory processing, and gross motor and fine motor skills.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study may be used as therapeutic evidence for sensory integration intervention in the clinical field of occupational therapy for children, and can help to present standards for sensory integration intervention protocols.

Keywords: Children, Meta-analysis, Occupational therapy, Sensory integration, Sensory processing, Social skills

Core Tip: This study conducted a meta-analysis to prove the effectiveness of sensory integration therapy, to examine the latest trends in domestic sensory integration studies, and to provide clinical evidence for sensory integration therapy. A meta-analysis was conducted on 24 selected studies. Sensory integration therapy has been proven effective in children with cerebral palsy, autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, developmental disorder, and intellectual disabilities in relation to the diagnosis of children. Sensory integration therapy was most effective in 1:1 individual treatment with the therapist, or a treatment session that lasted 40 min. In terms of dependent variables, sensory integration therapy effectively promoted sociality, adaptive behavior, sensory processing, total amount of exercise, and fine motor ability.

INTRODUCTION

Sensory integration is a neurological process that organizes sensory input so that it can interact efficiently within a given environment[1]. Also, sensory integration therapy enables the reception of various sensory stimulation, including visual, auditory, tactile, proprioceptive sense, and vestibular sense to achieve effective interaction between the child and the environment, and eventually result in a proper cognitive, motor behavioral, and emotional development[2,3]. If this sensory integration is impaired, environmental stimulation cannot be properly accepted, or the development of the learning potential of changing the environment in response to stimulation is disabled. As a result, performing such activities may require excessive focus and effort, and may result in difficulty in functional performance in daily life[4,5].

A variety of sensory integration therapy is applied to address the difficulties due to sensory integration disabilities. Sensory integration therapies provide child customized play and controlled sensory experience within the behavioral therapy setting[6]. Intervention is performed under the principle in which the vestibular, tactile, and proprioceptive senses play a main role, and effective processes and integrate senses[7]. As a result, appropriate posture control, maintaining of muscle tone, and emotional stability are developed and can bring about promotion praxis and sensory processing that are the basis of improving skills for activities of daily living and social participation, such as peer play, daily life activities, and learning[8].

So far, although studies that apply sensory integration therapy to children with various diseases have been conducted[2,9-11], the effectiveness of sensory integration therapy and its evidence have been controversial[12,13]. The main reason for the continuing controversy is the disparity in the way sensory integration therapy is applied in each study[14]. The methodology is being challenged due to disorganized protocol and inconsistent use of terminology[15,16]. Therefore, a process was needed to establish a treatment protocol by presenting consistent and scientific criteria for sensory integration therapy based on evidence-based studies that prove its effectiveness[17].

Meta-analysis and systematic review are two of the most objective and scientific research methods to prove the effectiveness of a study[18]. A meta-analysis statistically integrates various quantitative results from studies on an identical subject of study and transfers those to affect size in comprehensively analyzing various study results[19]. A summary using meta-analysis increases the number of samples by integrating the study results, thereby minimizing the distortion and error of each study and increasing statistical power. Likewise, it enables identifying factors that affect the study result when there is heterogeneity between the results of each study and suggests a total numerical value as robust evidence to enable an objective deduction[20,21].

Previous meta-analysis studies on sensory integration therapy have mostly focused on the change in dependent variables, such as behavior, learning, motor skills, and sensory processing[22-24]. Since they lacked analysis on the method of intervention, including the duration of treatment and the effectiveness by type and diagnosis, a study of such magnitude was necessary. Therefore, this study aims to prove the effectiveness of sensory integration therapies through a meta-analysis of sensory integration therapy in children from 2001 through 2020 and to provide fundamental data required for the establishment of theoretical evidence and systematic protocols for future sensory integration therapies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study used meta-analysis to analyze the effectiveness of sensory integration therapy through studies on sensory integration therapy in children. All processes of this study were conducted according to the procedures after receiving approval from the Kangwon National University Institutional Review Board (KWNUIRB-2021-12-002).

Literature search

The literature search was conducted from October 24 to October 26, 2020, and targeted literature that was published from 2001 to October 2020 in Korea. Korean databases, including RISS (Research Information Sharing Service) provided by Korea Education and Research Information Service, DBpia engineered by Nurimedia, and KISS (Korean Studies Information Service System) provided by Korean Studies Information, were used for the online literature search. The keywords, “Children” AND “Sensory integration”, “Integrated sensory”, “Sensory-motor”, and “Sensory stimulation” were used. The review was conducted by two individual investigators, and any disagreements on the review articles were put under author discussion and selection.

Study selection and data extraction

The inclusion criteria of subject literature were done first, including studies published as domestic theses; secondly, studies that applied sensory integration therapy either by group or 1:1 session; third, two-group comparison studies consisting of both test group and control group; and fourth, studies of which the test data and full text are made available. Studies conducted on adults, not children, single case studies, studies of which the resulting data and full test are not available, single group experimental studies without control groups, studies using medication and review literature, and qualitative studies were excluded.

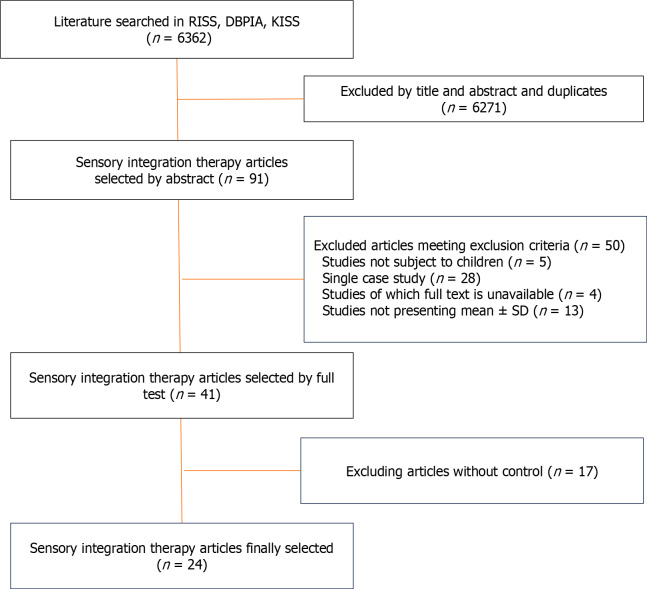

Figure 1 shows the study selection process. A total of 6362 studies were found in the Korean database after using the preselected keywords. Based on the second search, the titles and abstracts of the studies were reviewed, and a total of 91 studies were selected, excluding studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria and duplicates. Then, the full text of the 91 studies was reviewed to exclude a total of 67 non-conforming studies (5 studies where children were not targeted for sensory integration therapy, 28 single case studies, 4 studies of which the full text was not available, 13 studies that did not present necessary data, including mean and standard deviation, and 17 studies without a control group), resulting in a total of 24 studies selected for meta-analysis. The contents of the selected studies are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Literature selection flow diagram.

Table 1.

Characteristics of selected studies

|

Ref.

|

Age (yr)

|

Diagnosis

|

Test/control

|

Frequency

|

Result

|

Measurement

|

Quality Assessment

|

| Kwon et al[37], 2001 | 4-7 | CP | 10/10 | Twice per week/30-40 min/20 times | Sensory, gross motor, fine motor, adaptive behavior | GMFM, PMDT, adaptive behavior checklist | 2 |

| Hong and Oh[39], 2003 | 15 | Mental retardation | 6/5 | Twice per week/50 min/20 times | Coordination (static, hand movement, general movement) | Korean Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency | 2 |

| Kwon et al[38], 2004 | 4-10 | Developmental disability | 12/14 | Twice per week/40 min/24 times | Sensory, motor | Sensory profile, PDMS | 2 |

| Kim et al[48], 2005 | 8-13 | Intellectual disability | 11/9 | Three times per week/40 min/30 times | Gross motor (motor, balance) | GMFM-88, BOTMP | 2 |

| Kim and Park[30], 2005 | 8-10 | Intellectual disability | 12/12 | Three times per week/40 min/60 times | Emotional behavior | EBC | 2 |

| Kim et al[40], 2006 | 8-10 | Intellectual disability | 12/12 | Three times per week/40 min/60 times | Object manipulation | TGMD-2 | 2 |

| Jeon and Ahn[49], 2006 | 10-13 | Intellectual disability | 10/10 | Three times per week/40 min/24 times | Attention | Superlab Pro 1.05 | 2 |

| Kang and Kang[34], 2007 | 6-13 | Developmental disability | 19/19 | Twice per week/60 min/40 times | Adaptive behavior | KISE-SAB | 2 |

| Kim[41], 2007 | 8-9 | Moderate intellectual disability | 12/12 | Six times per week/40 min/60 times | Motor | TGMD-2 | 2 |

| Kim[50], 2007 | 6-10 | Intellectual disability | 8/8 | Twice per week/90 min/24 times | Locomotion skills (gross motor) | TGMD-2 | 2 |

| Kim[31], 2008 | 3-4 | No disability | 3/4 | Twice per week/40 min/8 times | Adaptive behavior | ABC | 2 |

| Kwon[29], 2008 | 4-12 | Developmental disability | 19/20 | Twice per week/40 min/36 times | Motor, visual perception | TVPS-R, BOT2, SMS, SP | 2 |

| Yu and Koo[51], 2008 | 9-11 | ASD | 10/10 | Twice per week/40 min/24 times | Stereotyped behavior time, brain wave change | Time sampling record, WEMG-8 | 2 |

| Cho[33], 2008 | 7-36 mo | Developmental disability | 32/30 | Once a week/30 min/8 times | Development, sensory, routine movement | DDST, CCDT Wee FIM, SP | 2 |

| Kim[32], 2009 | 2-5 | Intellectual disability, mild ASD | 4/3 | Twice per week/30 min/20 times | Sensory, social, emotional | SSP, ITSEA, MT-MAP | 2 |

| Choi[36], 2010 | 5-7 | Developmental disability (except CP, ASD) |

10/10 | Twice per week/40 min/16 times | Gross motor (motor, balance) | GMFM, BOTMP | 1 |

| Kim[42], 2011 | 7-14 | Developmental coordination disability | 8/8 | Twice per week/40 min/8 sessions | Hand function (precision, dexterity) | Groove pegboard, BOTMPII | 2 |

| Lee[43], 2013 | 5-7 | ASD | 5/5 | Twice per week/60 min /14 sessions | Motor, play behavior | Oseretsky motor skill test, PPBS | 2 |

| Lee[52], 2015 | NLT 7 | Spastic diplegic cerebral palsy | 10/10 | Twice per week/40 min/10 sessions | Body schema, motor, self-efficacy | Draw-A-Person Test, GMFM-66, PSEQ | 1 |

| Lee[45], 2017 | 6-10 | ADHD | 8/8 | Twice per week/40 min/16 sessions | Sensory, motor skill at movement | SSP, BOT-2, VMI | 2 |

| Ryu[46], 2017 | 3-7 | Disabled and non-disabled brothers/ Disabled children |

20 (10 Group)/10 | Group (once a week/40min/10sessions); Individual (once a week/40 min/10 sessions) | Interaction, sensory processing; Play (time, level) | Peer Interaction scale; SSP, Revised knox; preschool play scale video |

2 |

| Lee et al[10], 2018 | 9-10 | ADHD | 10/10 | Twice per week/50 min/12 sessions | Sensory, social skills, self-esteem | SSP, SSRS, rosenberg self-esteem scale | 2 |

| Park and Kim[11], 2019 | 3-5 | Developmental retardation | 9/8 | Twice per week/40 min/ 16 sessions | sensory, motor | SSP, PDMS-2 | 2 |

| Kim[35], 2019 | 6 | No disability | 15/15 | Twice per week/40 min/16 sessions | Sensory, visual perception, problematic behavior | SSP, K-DTVP-II, K-CBCL | 1 |

Methodological quality

To improve the quality of the study in accordance with AMSTAR (Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews), a search was conducted for academic literature, including theses. The level of evidence model, which consist of 5 Levels developed by Arbesman, Scheer, and Lieberman (2008)[25], was used to assess the quality level of 24 studies that were selected after reviewing the full text. The level of evidence starts from the highest level of evidence, Level 1 up to Level 5, and the studies were classified under these levels. For the qualitative level of evidence of the studies selected, 3 studies (12%) were Level 1 (Randomized controlled trial), and 21 studies (88%) were Level 2 (Non-randomized two-group studies) (Table 2).

Table 2.

The level of qualitative evidence of subject studies

|

Level of evidence

|

Definition

|

n (%)

|

| Level 1 | Systematic review; Meta analysis; Randomized controlled trials | 3 (12) |

| Level 2 | Non-randomized two group studies | 21 (88) |

Statistical analysis

A meta-analysis was performed on the selected studies that were encoded with their characteristics. A significance test on Q statistics was conducted by performing a Chi-square test to evaluate statistical heterogeneity, where a P value lower than 0.10 indicated statistical heterogeneity[26]. Based on the statistical heterogeneity of each study, the random-effect model was applied in the presence of heterogeneity, and the fixed-effect model was applied in case of homogeneity, while the calculated effect sizes were summarized in a forest plot[27]. An effect size in a meta-analysis is a standardized indicator of the extent of difference between efficacies and relation. An effect size not less than 0.8 indicates a large effect; an effect size of about 0.5 indicates a medium effect; and an effect size of 0.2 or smaller indicates small effect[28].

The software program (CMA version 3) was used to conduct the meta-analysis. The effect size was calculated to determine the effect of sensory integration therapy in total, the effect of group and 1:1 individual sensory integration therapy, the effect of sensory integration therapy by diagnosis, and the effect of sensory integration therapy based on the duration of treatment.

RESULTS

Effect size by diagnosis and study design

For the effect size of sensory integration therapy by diagnosis, the effective size was largest in cerebral palsy (CP) [1.50 (confidence interval, CI: 1.25-1.74)], followed by autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [1.35 (CI: 0.96-1.71)] and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [1.06 (CI: 0.75-1.38)]. The effect size was determined as medium as 0.48 (CI: 0.38-0.58) for developmental disability, and as small as 0.14(CI: -0.05-0.34) for intellectual disability (Table 2).

For the effect size by study design, both 1:1 Individual treatment [0.50 (CI: 0.43-0.57)] and Group treatment [0.26 (CI: 0.05-0.47)] had medium effect size. For the duration of intervention, the effect size was small and negative for the duration of 30 min [-0.01 (CI: -0.13-0.11], and larger for the duration of 40 min [0.88 (CI: 0.77-0.99)] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Average effect sizes of design variable levels and diagnosis

|

Study design

|

95% Confidence interval

|

Heterogeneity

|

||||||

|

|

Category

|

Studies (n)

|

Effect size

|

Lower limit

|

Upper limit

|

Q

|

P value

|

df

|

| Diagnosis | CP | 3 | 1.50 | 1.25 | 1.74 | 90.36 | 0.000 | 2 |

| ASD | 2 | 1.35 | 0.96 | 1.71 | 0.63 | 0.43 | 1 | |

| ADHD | 2 | 1.06 | 0.75 | 1.38 | 36.52 | 0.31 | 1 | |

| Developmental disability | 6 | 0.48 | 0.38 | 0.58 | 273.62 | 0.000 | 5 | |

| Intellectual disability | 6 | 0.14 | -0.05 | 0.34 | 232.97 | 0.000 | 5 | |

| Time | 30 min | 3 | -0.01 | -0.13 | 0.11 | 1.22 | 0.54 | 2 |

| 40 min | 15 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.99 | 527.86 | 0.000 | 14 | |

| Method | Individual | 20 | 0.50 | 0.43 | 0.57 | 700.33 | 0.000 | 19 |

| Group | 4 | 0.26 | 0.05 | 0.47 | 46.88 | 0.000 | 3 | |

CP: Cerebral palsy; ASD: Autism spectrum disorder; ADHD: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

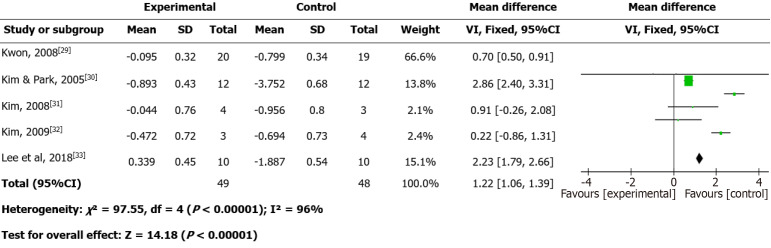

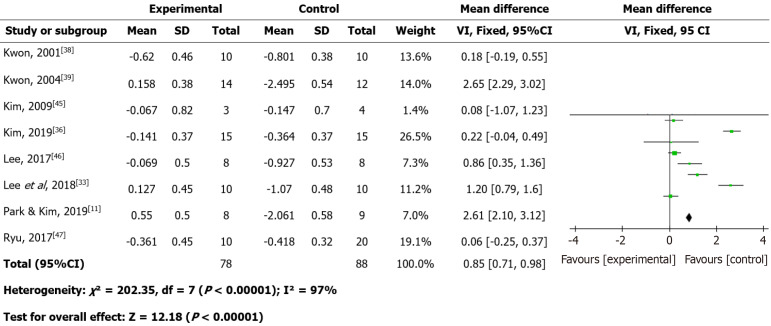

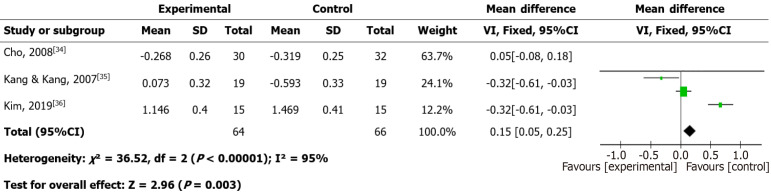

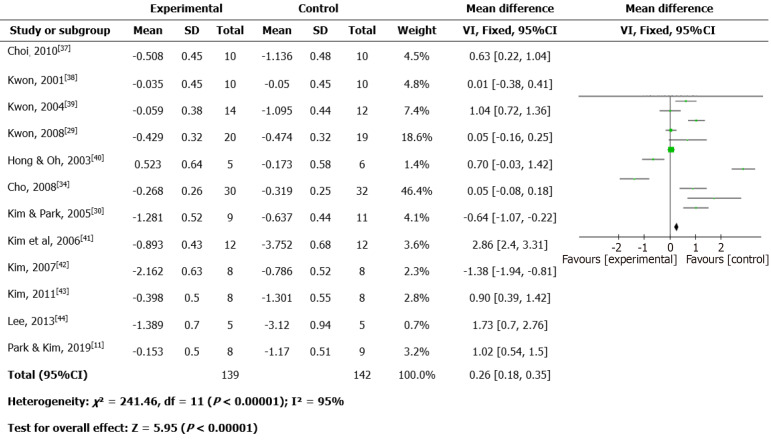

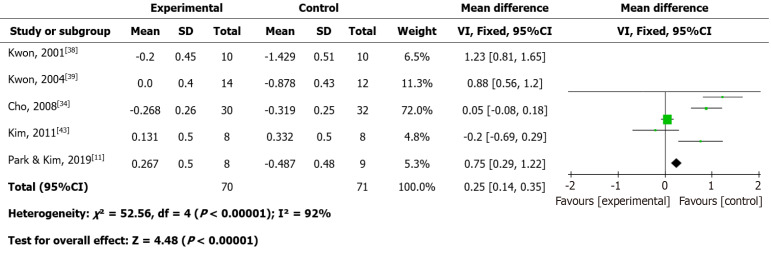

Effect size by dependent variable

Studies subject to analysis were narrowed down to 24 studies and categorized into 5 areas, including social skill, adaptive behavior, gross motor, fine motor, and sensory processing to identify the effect of sensory integration therapy on child function. By area, the largest number of studies was on gross motor, with 12 studies on gross motor, 8 on sensor processing, 5 on social skill and fine motor, and 3 on adaptive behavior. The effect size was largest in social skill, followed by adaptive behavior, sensory processing, gross motor, and fine motor, where the effect size was large for social skill, adaptive behavior, and sensory processing, and medium for gross motor and fine motor (Table 4, Figures 2-6)[29-46].

Table 4.

Effect size of sensory integrating intervention by dependent variable

|

Function

|

Effect size

|

SE

|

Studies (n)

|

Subjects (n)

|

| Social skill | 1.22 | 0.084 | 5 | 49 |

| Adaptive behavior | 1.15 | 0.051 | 3 | 64 |

| Sensory processing | 0.85 | 0.068 | 8 | 78 |

| Gross motor | 0.26 | 0.043 | 12 | 139 |

| Fine motor | 0.25 | 0.053 | 5 | 49 |

Figure 2.

Effect size of sensory integrating intervention by social skill. CI: Confidence interval.

Figure 6.

Effect size of sensory integrating intervention by sensory processing. CI: Confidence interval.

Figure 3.

Effect size of sensory integrating intervention by adaptive behavior. CI: Confidence interval.

Figure 4.

Effect size of sensory integrating intervention by gross motor. CI: Confidence interval.

Figure 5.

Effect size of sensory integrating intervention by fine motor. CI: Confidence interval.

For the effect size of specific sensory integration therapy by dependent variables, a statistically significant effect size was proven in all five areas (P < 0.05) (Figure 2). The effect size was as large as 1.22 (CI: 1.06-1.39) for social skill function, and heterogeneity was as high as 96%. The effect size for adaptive behavior was as small as 0.15 (CI: 0.05-0.25), and heterogeneity was as high as 95%. The effect size for sensory processing was as large as 0.85 (CI: 0.71-0.98), and heterogeneity was as high as 97%. The effect size for gross motor was medium at 0.26 (CI: 0.18-0.35), and heterogeneity was as high as 95%. The effect size of sensory integration therapy on fine motor was as large as 0.25 (CI: 0.14-0.35), and heterogeneity was as high as 92%.

DISCUSSION

Sensory integration is a theory in which adaptive behavior is induced by the relationship between the behavior and the neurological process based on the neurological activity in the central nervous system. It is applied and studied in various ways in clinical settings. Its efficacy is reported to be different based on the approach practiced by the therapist and its purpose. Therefore, this study was conducted to establish clinical evidence for sensory integration therapy by verifying the effectiveness of previous studies by using meta-analysis and providing fundamental data that will be useful for systematic protocol determination, and, eventually, improving the quality of occupational therapy.

This study analyzed 24 studies on sensory integration therapy published in Korea from 2001 to 2020.

First, the studies were randomized controlled studies (Level 1) or non-randomized two-group studies (Level 2), which were of high level of evidence in the qualitative analysis. Previous systematic review and meta-analysis studies were performed with articles of different qualitative levels of evidence, which resulted in the inconsistency of results. Whereas, this study only included studies with a high level of evidence to improve the level of clinical evidence.

For the meta-analysis by diagnosis and study design, CP (1.50) had the highest effectiveness, followed by ASD (1.35), ADHD (1.06), developmental disability (0.48), and intellectual disability (0.14). A variety of disease groups in children was not considered in previous studies, as the target diagnosis was set to mental disabilities, whereas this study included various disease groups, and analyzed the effect size by diagnosis to define the effectiveness of sensory integration therapy. Thus, sensory integration therapy was shown as being more effective for children with CP, ASD, and ADHD, based on the differences in individual ability and function, and purpose and method of intervention for each diagnosis. Also, further study is necessary as in previous studies on children with ASD, in which the effectiveness of sensory integration is defined in studies where only sensory integration was applied for treatment. Whereas, the effectiveness of sensory integration therapy is reported to be relatively low in studies comparing sensory integration with other intervention methods. In terms of the effect size by study design, effectiveness was larger for the intervention duration of 40 min (0.88) compared to 30 min (-0.01), and larger in 1:1 individual treatment (0.50) compared to group treatment (0.26). This leads to similar results to previous studies that reported effectiveness is higher when individual treatment is given at a duration of 60 min or longer.

Third, regarding the meta-analysis result by dependent variables, the largest effect was observed in social skills (1.22), followed by adaptive behavior (1.15), sensory processing (0.85), gross motor (0.26), and fine motor (0.25), indicating that sensory integration therapy is more effective in improving social skill, adaptive behavior, and sensory processing compared to motor function. This result contrasted with the former study, which reported that high effectiveness towards motor function was observed when sensory integration therapy was given under conditions of retardation, including CP. Also, although most of the studies presented conventional social skill improvement programs, including verbal or cognitive behavioral approaches[22,47], this study showed that sensory integration therapy is also an effective intervention to improve social skills and adaptive behavior. Taking into consideration that individual therapy was more effective compared to group therapy, the improvement of communication with the therapist and understanding of demands through intervention customized for children in 1:1 sessions were considered to have posed greater effect on social skills and adaptive behavior. Therefore, it is recommended for future studies to utilize the control group and to apply various methods and dependent variables to prove the efficacy of sensory integration therapies.

This study has several limitations. First, it included non-randomized, two-group studies, instead of all randomized controlled trials. While the quality of the research results may be low at the time of data collection, the final selected studies included 3 randomized controlled trials. A two-group non-randomized study was included due to difficulty of analysis. However, according to the 5 Levels of evidence developed by Arbesman, Scheer, and Lieberman (2008), the two-group non-randomized study offers a high level of evidence at Level 2, providing support that the results of this study can be trusted.

The second limitation is that the studies are published only in Korea. First, the studies had the same cultural background as there was a lack of controlled studies on sensory integration therapies, and differences in cultural backgrounds were not covered since there were no established standard protocols. Thus, studies should be analyzed based on various cultural backgrounds based on this study result to ensure a broader effectiveness analysis of sensory integration therapies. Moreover, if an effectiveness analysis is performed on sensory integration therapies, including studies comparing sensory integration therapies and other interventions, it will help occupational therapists in applying evidence-based sensory integration therapy in the clinical setting.

CONCLUSION

This study on the effectiveness of sensory integration therapy sought to examine the latest trend in studies on sensory integration therapies in Korea, and to propose therapeutic evidence.

Results confirmed that sensory integration therapies were effective in diagnosing children with CP, ASD, ADHD, developmental disability, and intellectual disability. Regarding sensory integration therapy approaches, 1:1 individual treatment with a therapist or a therapy session lasting for 40 min was most effective. A greater effect was observed in terms of social skills, adaptive behavior, and sensory processing function.

The results of this study may be used as therapeutic evidence for sensory integration therapy in children in occupational therapy practices and in standardization of effectiveness analysis through the diagnosis of children. The type of intervention will be useful in providing a practical standard for sensory integration therapy protocols. Based on the limitations of this study, the detail and progress of sensory integration therapies are analyzed more specifically, and adequate multi-national randomized controlled trials can be accumulated in future studies to further demonstrate the effectiveness of sensory integration therapies. Also, further meta-analysis study is required not only for studies on the method of sensory integration therapies, but for various intervention methods that combine sensory integration therapy and other interventions.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Sensory integration is a neurological process that allows the child to interact effectively with the environment through stimulation of various senses. Difficulties in sensory integration lead to difficulties in functional performance in daily life.

Research motivation

Recent studies have methodological problems due to different sensory integration intervention methods for each study and unsystematic protocols. Therefore, evidence-based research is needed to prove treatment effectiveness.

Research objectives

The purpose is to confirm the effectiveness of sensory integration intervention, present basic data for a systematic protocol, and prepare a theoretical basis.

Research methods

To analyze the effects of sensory integration interventions, a meta-analysis method was used to investigate the effects of sensory integration interventions through papers published from 2001 to 2020 targeting children.

Research results

Through this study, the effectiveness of sensory integration intervention was confirmed, and based on this, it is believed that it will be helpful in applying evidence-based sensory integration intervention in clinical settings. As a limitation, there are differences depending on cultural background in literature published in Korea, so it is recommended to conduct research based on various cultural backgrounds in the future.

Research conclusions

The sensory integration intervention method proposed in this study is more effective for subjects with cerebral palsy, autism spectrum disorder, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and is more effective when performed as a 1:1 individual treatment for 40 min.

Research perspectives

It would be even more helpful to analyze the effectiveness of sensory integration interventions, including studies that applied not only sensory integration interventions but also other interventions based on diverse cultural backgrounds.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement: The authors have read the PRISMA 2009 Checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: December 6, 2023

First decision: December 22, 2023

Article in press: January 27, 2024

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Govindarajan KK, India S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S

Contributor Information

Seri Oh, Department of Occupational Therapy, Kangwon National University Graduate School, Samcheok 25949, South Korea.

Jong-Sik Jang, Department of Occupational Therapy, Kangwon National University, Samcheok 25949, South Korea.

A-Ra Jeon, Department of Occupational Therapy, Ju-Ju Children Development Center, Nonsan-si 32985, Chungcheongnam-do, South Korea.

Geonwoo Kim, Department of Occupational Therapy, Kangwon National University Graduate School, Samcheok 25949, South Korea.

Mihwa Kwon, Department of Occupation Therapy, Suwon Women’s University, Gyeonggi-do 16632, South Korea.

Bahoe Cho, Hijam Center for Development of Children, Ochang 28117, South Korea.

Narae Lee, Department of Occupational Therapy, U1 University, Chung-cheong bukdo 25949, South Korea. nereis1004@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Smith MC. Sensory integration: Theory and practice. 3th ed. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 2019: 21-39. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park AR. Research Trends and Meta-analysis on Effect of Art Therapy on Children from Families in a Lower-Income Bracket, electronic, scholarly journal. M.Sc. Thesis, The Wonkwang University. 2018. Available from: http://www.riss.kr/Link?id=T14761030 . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee SY. Effect of sensory integration program on the cognitive and language development for children with mental retardation, electronic, scholarly journal. M.Sc. Thesis, The Inje University. 2004. Available from: http://www.riss.kr/Link?id=T9862586 . [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim KM, Shin HH, Kim MH. A preliminary study to development of an assessment to measure sensory processing of children, 'sensory processing scale for children (SPS-C)'. J Kore Soci Sens Integr Therap. 2015;13:31–41. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi JS, Kang DH, Kim JK. The Effects of Sensory Integration Treatment on Occupational Performance Abilities in Children with Developmental Disabilities. Kore J Occup Ther. 2008;16:33–43. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bundy AC, Lane SJ, Murray EA. Sensory integration: Theory and practice. 2th ed. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 2002: 3-33. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ayres AJ. Sensory Integration and Praxis Tests: SIPT. Los Angeles: Western. 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parham LD, Mailloux Z. Sensory integration. In: Case-Smith J, O’Brien JC. Occupational therapy for children and adolescents. 7th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby, 2015: 258-303. [Google Scholar]

- 9.May-Benson TA, Koomar JA. Systematic review of the research evidence examining the effectiveness of interventions using a sensory integrative approach for children. Am J Occup Ther. 2010;64:403–414. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2010.09071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee NH, Jang MY, Lee JS, Kang JW, Yeo SS, Kim KM. The Effects of Group Play Activities Based on Ayres Sensory Integration® on Sensory Processing Ability, Social Skill Ability and Self-Esteem of Low-Income Children With ADHD. J Kore Soci Sens Integr Therap. 2018;16:2 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park HN, Kim KM. The Effect of ayres sensory integration intervention on sensory processing ability and motor development in children with developmental delay. J Kore Soci Sens Integr Therap. 2019;17:2 18–30. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leong HM, Carter M, Stephenson J. Systematic review of sensory integration therapy for individuals with disabilities: Single case design studies. Res Dev Disabil. 2015;47:334–351. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2015.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barton EE, Reichow B, Schnitz A, Smith IC, Sherlock D. A systematic review of sensory-based treatments for children with disabilities. Res Dev Disabil. 2015;37:64–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller LJ. Empirical evidence related to therapies for sensory processing impairments. STAR Institute. 2003;31:2–5. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong EK, Kim KM, Chang MY. Fidelity in Core Principles of Ayres Sensory Integration. Kore Aca Sens Integr. 2011;9:11–20. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shin YN, Hong EK, Yoo EY. The Effectiveness of Ayres Sensory integration® and Sensory-Based Intervention for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. J Spec Edu Rehabil Sci. 2017;56:437–456. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoo DH, Lee JS, Kim HM, Hong DG. A systemic review and meta-analysis on the effects of FES intervention for stroke patients. J Kore Soci Occup Ther. 2012;20:111–126. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong EK, Kim KM. A Meta-Analysis on the Effects of Sensory Integration Intervention for Children: Focus on Studies of South Korea. J Spec Edu Rehabil Sci. 2014;53:299–313. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jo CH. A meta-analysis of the effects of peer tutoring on the mathematics learning achievements and affective domain, electronic, scholarly journal. M.Sc. Thesis, The Korea University. 2019. Available from: http://www.riss.kr/Link?id=T15063018 . [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin IS, Park EY. Review of the meta-analysis research in special education and related field. J Phys Mul Disabi. 2011;54:157–176. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song YS, Gang MH, Kim SA, Shin IS. Review of meta-analysis research on exercise in South Korea. J Kore Aca Nurs. 2014;44:459–470. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2014.44.5.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hong SY. Effectiveness of Sociality Improvement Programs for School-aged ADHD Children - A Meta-analysis. Ment Health Soc Work. 2014;42:33–62. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim EJ, Choi YL. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Sensory Integration Intervention Studies in Children with Cerebral Palsy. J Dig Policy Manage. 2013;11:383–389. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vargas S, Camilli G. A meta-analysis of research on sensory integration treatment. Am J Occup Ther. 1999;53:189–198. doi: 10.5014/ajot.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arbesman M, Scheer J, Lieberman D. Using AOTA’s critically appraised topic (CAT) and critically appraised paper (CAP) series to link evidence to practice. OT Pract. 2008;13:18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenthal R, Rubin DB. Comparing effect sizes of independent studies. Psychol Bull. 1982;92:500–504. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hedges LV, Olkin I. Statistical methods for meta-analysis. 1985, Cambridge: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwon HR. Effects of Sensory Integration Therapy on Motor Proficiency and Visual Perception Development in Children with Developmental Disability, electronic, scholarly journal. Ph.D. Thesis, The CHA University. 2008. Available from: http://www.riss.kr/Link?id=T15540896 . [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim DH, Park JS. The Effects of Sensory Integration Program on the Emotional Behaviors of children with Moderate Mental Retardation. J Spec Child Educ. 2005;7:61–80. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim JM. The Effects of Sensory Integration Program on Facilitating Sensory Motor Development with Preschooler, electronic, scholarly journal. M.Sc. Thesis, The Inje University. 2008. Available from: http://www.riss.kr/Link?id=T11391231 . [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim EK. Effects of Sensory Integration Music activities on the sensory processing ability and the socioemotional fields of Children with Pervasive Developmental Disorder, electronic, scholarly journal. M.Sc. Thesis, The Sungshin Women's University. 2009. Available from: http://www.riss.kr/Link?id=T11577193 . [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cho EH. The Effect Home-based Program of Sensory Integration on Development and Sensory Profile among Delayed Developmental Children, electronic, scholarly journal. M.Sc. Thesis, The Inje University. 2008. Available from: http://www.riss.kr/Link?id=T11391157 . [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang SA, Kang SY. The Effects of Sensory Integration Activity on Adaptive Behavior of Children with Disabilities. J Coa Develop. 2007;9:447–455. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim HS. The Effects of Sensory Integration on Sensory processing, Visual perception and behavior of Attention Deficit-Hyperactivity, electronic, scholarly journal. M.Sc. Thesis, The Konyang University. 2019. Available from: http://www.riss.kr/Link?id=T15089181 . [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi DK. The Effect of Proprioception-oriented Sensory Integration Training on Gross Motor Function and Balance in children with Developmental Delay, electronic, scholarly journal. M.Sc. Thesis, The Dankook University. 2010. Available from: http://www.riss.kr/Link?id=T11957694 . [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwon HJ. Effects of Sensory Integration Therapy on Sensory·Motor Development and Adaptive Behavior of Cerebral Palsy Children. J Kore Acad Phys Ther. 2001;8:977–987. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kwon HR. Effects of Child-centered Sensory Integration Therapy on Motor Development and Sensory Processing Ability of Children with Pervasive Developmental Disorder, electronic, scholarly journal. M.Sc. Thesis, The Pochon CHA University. 2004. Available from: http://www.riss.kr/Link?id=T11251539 . [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hong YJ, Oh DJ. The Effects of Sensory Integration Program on Motor Coordination in the Children with Educable Mental Retardation. Kore J Ada Phys Act. 2003;11:149–155. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim DH, Park JK, Kim YM, Park JS. The Effects of Sensory Integration Program on Object Control Skills of Children with Moderate Mental Retardation. J Spec Child Educ. 2006;7:83–99. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim KJ. The Effects The Effects Effects of Sensory Sensory Sensory Integration Integration Training Program Training Program Program on the Motor Ability Ability Ability of Mentally Retarded Mentally Retarded Retarded, electronic, scholarly journal. M.Sc. Thesis, The Chonnam National University. 2007. Available from: http://www.riss.kr/Link?id=T10817246 . [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim HN. Effects of Sensory Integration program on Hand Dexterity and Hand Precision of the Children with Developmental Coordination, electronic, scholarly journal. M.Sc. Thesis, The Dankook University. 2011. Available from: http://www.riss.kr/Link?id=T12498602 . [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee SY. The Impact of Group Sensory Integrative Intervention for Motor Skills and Play Behaviors of the Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder, electronic, scholarly journal. M.Sc. Thesis, The Daegu University. 2013. Available from: http://www.riss.kr/Link?id=T13259281 . [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim EK. Effects of Sensory Integration Music activities on the sensory processing ability and the socioemotional fields of Children with Pervasive Developmental Disorder, electronic, scholarly journal. M.Sc. Thesis, The Sungshin Women's University. 2009. Available from: http://www.riss.kr/Link?id=T11577193 . [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee GY. The Effects of Ayres Sensory Integration® Intervention on Sensory Processing, Motor Praxis and Visual-Motor Skill for School-Aged Children With ADHD, electronic, scholarly journal. M.Sc. Thesis, The Inje University. 2017. Available from: http://www.riss.kr/Link?id=T14547898 . [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ryu JS. Effects of the Paired Sibling Group Sensory Integration Therapy on Peer Interaction an Playing of Children with Disabilities, electronic, scholarly journal. M.Sc. Thesis, The Woosong University. Dajeon. 2017. Available from: http://www.riss.kr/Link?id=T14688006 . [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park WJ, Park SJ, Hwang SD. Effects of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder among School-aged Children in Korea: A Meta-Analysis. J Kore Aca Nurs. 2015;45:169–182. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2015.45.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim YR, Park JW, Lee SH, Kim DH, Lee HY. Effect of Sensory Integration Training Program and Detraining on Gross Motor Function and Balance of Mental Retarded Children. Kore J Ada Phys Act. 2005;13:75–89. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jeon OB, Ahn SW. Effects of Sensory Integration Training Program on Improving Attention Span of Children with Mental Retardation. J Spec Edu Theo Prac. 2006;7:171–189. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim YM. The Effect of Sensory Integration Program on Locomotor Skills of Children with Mental Retardation, electronic, scholarly journal. M.Sc. Thesis, The Nazarene University. Cheonan. 2007. Available from: https://www.riss.kr/link?id=T11285952 . [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu SJ, Koo KM. The Effect of A Sensory Motor Program on the Duration of Stereotype Behavior and Electroencephalogram in Children with Autism. Kore J Ada Phys Act. 2008;16:151–173. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee EK. The Effect of Proprioceptive Activities in Sensory Integration on Body Scheme, Motor Function and Physical Self-Efficacy in Children with Cerebral Palsy, electronic, scholarly journal. M.Sc. Thesis, The Gacho University. Seongnam. 2015. Available from: https://www.riss.kr/link?id=T13704267 . [Google Scholar]