Abstract

Background:

Paid caregivers are needed to support older adults, but caregiver burden contributes to high turnover rates. Assistive technologies help perform activities of daily living (ADLs) and can reduce caregiver burden, but little is known about how they impact paid caregivers.

Objective:

This scoping review provides an overview of evidence on using assistive technology to reduce burdens on paid caregivers working with older adults.

Design:

The review was conducted from May to August 2022. The eligibility criteria included: (1) publication within 5 years in peer-reviewed journals, (2) investigation of assistive technology, (3) main participants include paid caregivers supporting older adults, and (4) describing impacts on caregiver burden. Searches were conducted in 6 databases, generating 702 articles. The charted data included (1) country of study, (2) participant care roles, (3) study design, (4) main outcomes, and (5) types of assistive technology. Numerical description and qualitative content analysis of themes were used.

Results:

Fifteen articles reporting on studies in 9 countries were retained for analysis. Studies used a variety of quantitative (8/15), qualitative (5/15), and mixed (2/15) methods. Technologies studied included grab bars and handrails, bidet seats, bed transfer devices, sensor and monitoring systems, social communication systems, and companion robots. Articles identified benefits for reducing stress and workload, while paid caregivers described both positive and negative impacts.

Conclusions:

Literature describing the impact of assistive technology on paid caregivers who work with older adults is limited and uses varied methodologies. Additional research is needed to enable rigorous evaluation of specific technologies and impacts on worker turnover.

Keywords: assistive technology, paid caregivers, personal support workers, healthcare

People around the world are living longer, drastically changing population demographics 1 and increasing the need for caregivers for older adults.2,3 Dementia, osteoarthritis, cardiovascular disease, mobility disabilities, and stroke are more likely as people age. 4 Studies have demonstrated that chronic conditions such as dementia contribute significantly to caregiver burden, 5 and caregivers increasingly face challenges associated with providing care for individuals living with complex chronic conditions. 6

Canada exemplifies these shifts, where older adults, defined as those over the age of 65 years, are projected to reach nearly 1 in 4 (23%) of the total population by 2030. 7 It is estimated that more than one-third of Canadian older adults (37%) have at least 2 common chronic diseases. 8 This changing population distribution and growing prevalence of chronic conditions will increase the demand for, and demands on, people providing care for Canadian older adults. 9 The changes due to demographic pressure may also be compounded by the preference of Canadian older adults to age as long as possible at home, requiring home care services. 10

Paid caregivers play essential roles in meeting the needs of older adults who live in long-term care facilities or receive care in their homes. Paid caregivers include workers who hold professional accreditation, such as nurses or allied health professionals, as well as a variety of support workers, nursing assistants, and aides who are not regulated by professional colleges. 11 In Canada, unregulated paid caregivers constitute the largest category of service workers in home care 12 and long-term care. 13 Due to health workforce shortages and changing expectations around the scope of care, in addition to providing routine support for activities of daily living (ADLs), unregulated paid caregivers are now performing activities that previously were provided by regulated health professionals. 10 Unregulated paid caregivers employed in equivalent roles have different job titles across Canada and internationally. These include health support workers, home care workers, home healthcare aides, and home care attendants, among others. 14 For simplicity, this article will refer to all unregulated paid caregivers as personal support workers (PSWs).

Caregiving, whether by paid workers or unpaid family or friends, is a demanding role and can lead to burnout. One potential strategy to make caring for older adults sustainable for caregivers is to make greater use of assistive technology. 15 Assistive technology is a term for systems or services that promote independence and improve function. 16 It encompasses a wide range of products from “low-technology” items, such as grab bars, walkers, and reminder calendars, to “high-technology” items, such as sensors, remote monitoring systems, and GPS tracking technology. 17

While many studies focus on the use of assistive technology for persons with disabilities, researchers globally and organizations like the World Health Organization have expanded the scope to include older people and people experiencing gradual functional decline. 17 Assistive technology has been attracting interest in the context of the aging population for its potential to support older adults to age more safely and longer at home. 18 The use of assistive technology to reduce caregiver burden has also been a quickly growing area of study.15,19 A systematic review conducted by Marasinghe 15 demonstrates that wide-ranging assistive technologies can support caregivers in various domains, reducing time spent, anxiety and fear, task difficulty, and safety risks. Mortenson et al 20 also reported that assistive technologies significantly reduced caregivers’ overall burden. However, a gap exists because much of the literature, including the aforementioned reviews, focuses on unpaid caregivers, and few published studies have investigated the effects of assistive technology on paid caregivers’ burden in the context of caring for older adults.

This gap in the literature is important because paid caregivers are in shortage in Canada 21 and other higher-income countries. 2 Many PSWs leave the sector every year due to undesirable working conditions and low pay.2,21-23 As personnel without professional status and relatively little formal training, PSWs often experience job insecurity, low pay, and lack of appreciation or recognition for their contributions.9,14,24-26 PSWs also often face aggression and gender-based violence from clients.24,25,27 Gender inequality is a component in these difficult working conditions, as caregiving occupations, such as PSWs and nurses, are predominantly filled by women.2,24 Increased demands for paid caregiving, due to population aging, are superimposed on the already existing challenges these workers face, including lack of support, work overload, staff shortage, limited resources, and safety concerns.2,14,26

With the essential roles that PSWs and other paid caregivers perform in caring for the older adult population, it is important to develop strategies that will reduce their work-related burdens and improve retention to support a stable workforce. This scoping review provides decision-makers and researchers in Canada and internationally an overview of evidence available on using assistive technology to reduce burdens of paid caregivers working with older adult clients.

Methods

The research at the AGE-WELL National Innovation Hub APPTA focuses on knowledge translation and mobilization to support Canadian federal, provincial, and territorial government departments, and nongovernmental organizations, in applying evidence-based practices to support older adults. In consultations with the AGE-WELL National Innovation Hub APPTA in 2022, representatives from several provincial governments indicated that the paid caregiver workforce was an area of concern. Workplace conditions are important factors in caregiver turnover.2,21-23 The research team identified the impacts of assistive technology on the work burdens of paid caregivers working with older adults as a suitable topic for a rapid scoping review to summarize and disseminate relevant research to the stakeholder network. 28

The scoping review was carried out from May to August 2022, using the framework outlined by Arksey and O’Malley 28 and expanded by Levac et al 29 and the Joanna Briggs Institute Collaboration. 30 The review process was reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocols extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guideline. 31

Eligibility Criteria

The eligibility criteria were designed to capture literature that would provide an overview of evidence exploring the impacts of assistive technology on burdens experienced by paid caregivers working with older adults and would be applicable to the Canadian contexts. The articles would be included in the review if they (1) were published in peer-reviewed journals within the previous 5 years, in recognition of the rapid changes in some technologies; (2) described assistive technology that directly supports caregiving tasks or promotes older adults’ functionality, safety, or independence in performing ADLs; (3) included as primary study participants paid workers described as “caregivers” who provide care in clinical, community, and domiciliary healthcare settings 21 for older adults aged 65+, which could include personnel identified as long-term care staff, formal caregivers, home care aides, health and social care workers, paid home care providers, PSWs, and other similar roles; and (4) explored the effects of assistive technologies on caregiver burden, such as changes in workload, perceived changes in workload, stress levels, emotional or physical burden, and job satisfaction. The articles were excluded if they were (1) unavailable in English, due to the language competencies of the reviewing team; (2) review articles, such as systematic reviews, scoping reviews, or meta-analyses, since articles included in relevant review papers would be individually assessed; and (3) studies that focused exclusively on regulated healthcare professionals, such as occupational therapists, physiotherapists, nurses, and physicians, because the review was meant to capture impacts on burdens felt by workers who assist with ADLs, rather than those who provide medical care.

Search Procedures

Search procedures were developed using the iterative process suggested for scoping reviews, initially using broad exploratory searches, then refining terms to achieve more focused and relevant results.28,30 During the exploratory phase, one team member used general terms, such as “assistive technology” and “caregiver burnout” in searches on PubMed. The team discussed the initial search results and used terms from relevant articles’ titles, abstracts, and keywords to develop a more focused strategy.

The main search was carried out from May to June 2022 in the following databases: PubMed, ASSIA, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Ovid MEDLINE, and Ovid Embase. Search terms focused on 3 categories. The first category was centered around “assistive technology” and other similar terms used in literature, such as “self-help devices,” “welfare technology,” and “ambient assisted living,” among others. The second category aimed to capture the impacts on caregiver burden, through search terms such as “caregiver burden,” “professional burnout,” and “attitude of health personnel.” The third category used terms relating to older adults, such as “older adult,” “frailty,” “aged care,” “elderly people,” and related terms. An example search used for PsycINFO can be found in Table 1. A total of 702 articles published from 2017 to 2022 were identified from the databases: PubMed (n = 372), PsycINFO (n = 141), Ovid MEDLINE and Ovid Embase (n = 7), CINAHL (n = 64), and ASSIA (n = 48). The examination of review article bibliographies identified 70 articles.

Table 1.

PsycINFO Search Strategy (Year 2017-2022).

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|

| noft(assistive technology) OR noft(assistive robotics) OR noft(self-help devices) OR noft(welfare technology) OR noft(ambient assisted living) 2017-2022 Results: 2789 |

noft(attitude of health personnel) OR noft(caregiver burden) OR noft(occupational stress) OR noft(professional burnout) OR noft(caregiver well being) OR noft(caregiver health) OR noft(caregiver role strain) 2017-2022 Results: 34,524 |

noft(frail elder) OR noft(elderly) OR noft(aged) OR noft(older adults) OR noft(senior) OR noft(aging population) OR noft(65 years) 2017-2022 Results: 228,140 |

Combined results of 1 AND 2 AND 3 = 141 results.

Data Items and Analysis

The data charting categories were developed to align with the review’s goal, 28 to provide an overview of evidence on the impacts assistive technology has on burdens experienced by paid caregivers working with older adults. Information pertaining to the following categories was included in the evidence synthesis summary results: (1) the country where the research study was conducted, as settings are important for generalizability of research findings; (2) participant care roles, to ensure appropriate comparisons; (3) study methods or design, to gauge strengths and weaknesses of the body of evidence; (4) main outcomes; and (5) types of assistive technology. Charted data were analyzed using techniques suggested for scoping reviews, with numerical description of the body of literature, and qualitative content analysis of themes found within the articles.28-30

Although scoping reviews are ideally conducted with 2 or more reviewers independently carrying out article selection and data charting,29,30 due to time constraints, screening and data charting were conducted by 1 team member, with the others providing input at meetings held every 2 weeks. All team members took part in the interpretation and analysis of the body of literature.

Results

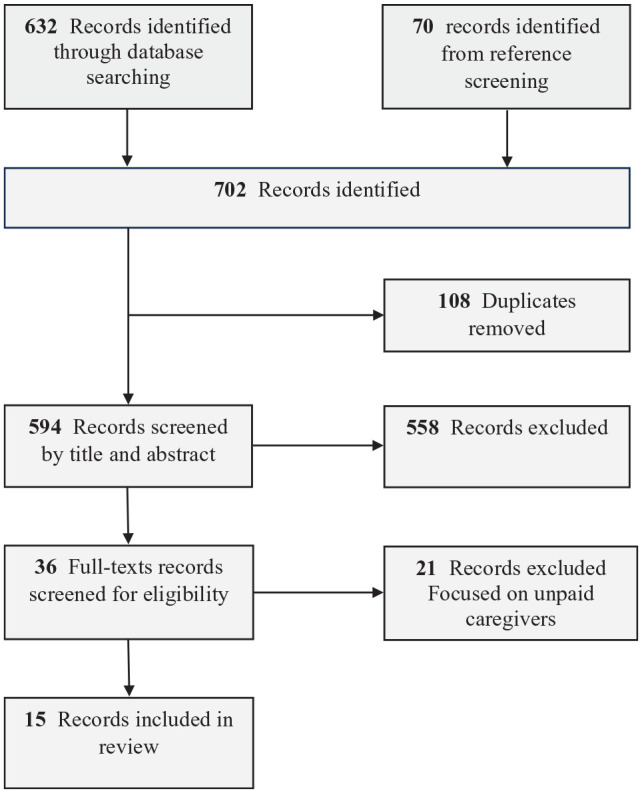

A total of 702 articles were screened. Of these, 108 duplicates were removed, and 558 were removed during title and abstract screening. Full texts of 36 articles were reviewed, and 21 studies that focused on unpaid caregivers were excluded (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA-ScR source selection diagram.

Fifteen articles were retained for analysis (Table 2).32-46 Studies reported in the articles were conducted in several countries and employed a variety of quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methodologies. Technologies examined in the articles were of 3 general types: physical or mobility aids, sensor and monitoring systems, and socialization enhancement technologies. Qualitative content analysis of the articles revealed paid caregivers’ perspectives on the assistive technologies they worked with.

Table 2.

Articles’ Summary.

| Author and country | Technology used | Study type | Type of caregiver | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobility or physical aids | ||||

| Sun et al

32

United States of America |

Transfer devices (slide boards) | Quantitative (survey and hand force analysis) | 16 home care aides from home care agency |

|

| Hwang et al

33

United States of America |

Air-assisted transfer device and turning/drawing sheet devices | Quantitative (electromyography) | 20 professional caregivers via email | Air-assisted transfer and turning devices showed potential benefits for reducing awkward postures (trunk and shoulder flexion), lower back (L5/S1) moment, and muscle activity in the upper extremities and lower back during patient turning tasks The L5/S1 flexion moment was significantly reduced by the air-assisted turning device during the turning toward task, and by the air-assisted transfer device during the turning away task |

| Phetsitong and Vapattanawong

34

Thailand |

Household handrail | Quantitative (questionnaire) | 254 formal/informal caregivers from care facility | Based on measurements by CBI, caregivers were less likely to experience a high physical care burden in households where there was one handrail in older person’s households compared with the caregivers of the households without a handrail The caregivers in the households with one handrail had 0.56 times less chance of physical burden than the non-handrail household caregivers. Caregivers in the households that have one handrail were less likely to suffer from a high physical burden than the caregivers of non-handrail households by 58% |

| King et al

36

Canada |

Grab bars, walkers | Qualitative (focus group) | Professional home care providers—eg, PSW, OT, PT (3 focus groups, 4-7 participants in each) from agency | Participants did not feel that available assistive devices provided enough assistance to reduce the danger and difficulty of these activities They expressed that often the assistive technologies were incompatible with clients’ home (constrained spaces) The participants said that lack of appropriate equipment represents a major risk factor for injury for both care recipients and care providers |

| King et al

35

Canada |

Bidet seats, raised toilet seats, walkers | Mixed methods (observation and measurement of risk factors) | 8 PSWs from home care agencies | Bidet seat on toilet eliminated a need for perineal care and improved independence Reduced exposure to nonneutral postures by 15% and to severe flexion by 32% |

| Sensor and monitoring technologies | ||||

| Hall et al

37

United Kingdom |

Various sensor and monitoring technologies (eg, bed-monitoring systems, wearable location-tracking devices) | Qualitative (multiple case study, semi-structured interviews, non-participant observation) | 24 care staff from care homes | Increased sense of overburden from the frequency of alarms Bed-monitoring systems largely contributed to an increase in staff confidence and coordination of practice Assistive technology was useful for preventing physical altercations between residents Expressed fear of being blamed for accidents |

| Dupuy et al

39

France |

Wireless sensors and tablets for socialization and safety notification | Quantitative (questionnaires) | 32 professional caregivers from community-dwelling houses | No change in subjective burden (emotional exhaustion) based on MBI, but positive impact of technology on objective burden (easier helping) based on IADL scale |

| Dupuy and Sauzéon

38

France |

Sensors, actuators, and tablets for socialization and safety notification | Quantitative (questionnaires) | 32 professional caregivers from home care service | No change in subjective burden (emotional exhaustion) based on measurement by MBI, but positive impact of HomeAssist on objective burden (easier helping) based on measurement by the IADL scale Caregivers’ difficulties remain constant during the first 6 months of use and decrease over the last 3 months |

| Rondon-Sulbaran et al

40

United Kingdom |

Various alarms (eg, fall alarms, flood alarms), sensors (eg, motion sensor) | Qualitative (semi-structured interviews) | 21 formal caregivers from supported accommodation facilities | Most participants suggested that assistive technology was beneficial in supporting tenants to live independently and helping them with day-to-day tasks Expressed feeling more ease at job, improved job satisfaction, and increased free time |

| Lauriks et al

41

The Netherlands |

Sensor and monitoring technologies (eg, pathway lighting; automated alerts, sun blinds, and lighting) | Quantitative (pilot RCT) (questionnaire) |

25 professional caregivers from residential care facility | Maastricht Job Satisfaction Scale for Healthcare (for job satisfaction) and Utrecht Burnout Scale, (for workload) indicated no effects on job satisfaction, workload Displayed moderate negative effect on work circumstance appreciation during the implementation phase |

| Robots | ||||

| Moyle et al

42

Australia |

Robots (Paro) | Qualitative (interviews) | 20 care staff from long-term care facilities | Most viewed the use of robots for dementia care positively Helpful in lowering agitation in older adults and reducing stress of caregivers Reported reduction in behavioral and psychological symptoms and disruptive behaviors Concerns about cost and lack of funding in LTC to afford them |

| Chen et al

43

Hong Kong |

Social robots, tablets, video gaming | Quantitative (cross-sectional survey) | 370 care workers from long-term care facilities | Technology acceptance among care workers was negatively correlated with disengagement and intention to leave The acceptance of video gaming changed the strength of the relationship between burnout and intention to leave among participants Tablets and robots did not have the same effect as tablets |

| Kolstad et al

44

Japan |

Robots (Paro, Pepper, Qoobo) | Qualitative (interviews) | Nursing staff (n = unstated) from 3 care facilities | Robots made jobs easier by calming patients down and instantly improving mood of older adults. Allowed staff to work on other tasks by distracting patients Demanded time and additional effort from staff; in some cases, there was no time to spare |

| Khaksar et al

45

Australia |

Robots (Matilda) | Mixed methods (interview, focus group, observations, equation modeling) | 13 caregivers from 3 residential aged care facilities | Many voiced that technology reduced workload, saved time, and increased productivity Expressed fear of being monitored by their managers via robots Expressed fear of being replaced by robots |

| Chen et al

46

Hong Kong |

Robot (Kabochan) | Quantitative (RCT) (questionnaire) | Caregiver staff from 7 long-term care facilities | There was a moderate positive effect in reducing neuropsychiatric-related caregiver distress by 16 weeks When robot was removed, there was a more pronounced increase in neuropsychiatric-related caregiver distress compared to control group |

Abbreviations: CBI: Caregiver Burden Inventory; MBI: Maslach Burnout Inventory; IADL: instrumental activities of daily living; LTC: Long Term Care; RCT: Randomized Controlled Trial.

Study Characteristics

The articles reported the results of studies in 9 countries. The United States of America,32,33 Australia,42,45 Canada,35,36 France,38,39 Hong Kong,43,46 and the United Kingdom37,40 were sites reported in 2 articles each. Japan, 44 the Netherlands, 41 and Thailand 34 were sites reported in 1 article each.

The literature was methodologically diverse. Eight articles (54%) described quantitative approaches,32-34,38,39,41,43,46 5 (33%) described qualitative study designs,36,37,40,42,44 and 2 (13%) described mixed-method strategies.35,45 Most quantitative studies employed surveys or questionnaires to assess emotional or physical caregiver burdens. For example, Chen et al 46 utilized the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire caregiver distress subscale, and Dupuy et al 39 utilized the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) and the Instrumental Activity of Daily Living (IADL) support scales. Sun et al 32 assessed the physical burdens of caregiving through a survey and hand force analysis. Phetsitong and Vapattanawong 34 used a quantitative questionnaire based on the Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI). Two quantitative studies used pilot or prospective RCT designs.41,46 Qualitative studies relied on interviews or focus groups.36,37,40,42,44 Two studies employed mixed-method designs. Khaksar et al 45 used interviews, observation, and focus groups for the qualitative aspect of their study and equation modeling for the quantitative component of their study. King et al 35 used qualitative observational methodology, complemented by quantitative risk factor analysis.

Physical or Mobility Aids

Five articles reported the effects on the caregiver burden of technologies that provide mobility and physical support for older adults. Two examined impacts of handrails and grab bars. King et al 36 explored whether PSWs found grab bars helpful when helping older adults in at-home bathrooms, while Phetsitong and Vapattanawong 34 assessed the impacts of handrails on the physical burden of caregivers. Both studies reported that handrails and grab bars made caregiving processes physically easier and safer in their respective settings.34,36 Phetsitong and Vapattanawong’s 34 survey using the CBI found that caregivers working in households with one handrail were 58% less likely to suffer from a high physical burden than caregivers of non-handrail households. However, King et al 36 reported that incompatibility of such devices with the physical surroundings, such as grab bars in a small washroom, could limit their utility and safety.

Three articles explored impacts of technologies designed to reduce physical strain on caregivers when helping older adults with ADLs, such as toileting 35 or transferring between beds and wheelchairs.32,33 Bidet seats were shown to prevent nonneutral posture by 15% and severe flexion by 32% by eliminating the need for perineal care. 35 The benefit demonstrated in the study by King et al 35 is likely underestimated, as PSW participants each carried out only 2 simulated sessions, while the same PSWs reported providing toileting assistance to approximately 4 clients per day when at work. Transfer devices were also tested in a simulated environment, where a client was transferred from one side of the bed to the other, from a wheelchair to a bed, or from a bed to a wheelchair.32,33 Both Sun et al 32 and Hwang et al 33 reported that transfer devices reduced physical loads on caregivers. Hwang et al 33 demonstrated with electromyography that transfer and turning devices could prevent awkward postures, with flexion in the lower back and shoulders, that are normally encountered while caring for older adults.

Sensor and Monitoring Systems

Five articles reported the effects of sensor and monitoring technologies on the burdens of paid caregiver. Some sensors were worn by older adults to continuously monitor their vital signs. 37 One study used satellite-based GPS tracking devices that could identify the location and activities of older adults. 37 Other studies used emplaced sensors. The sensor devices assessed in the study by Lauriks et al 41 included automated lighting and automated sun blinds. In the case of automated lighting, sensors could detect movement and automatically turn on and off lights when a person got out of bed, entered the bathroom, or when an area was detected with insufficient lighting. Rondon-Sulbaran et al 40 evaluated a variety of sensor alarms that could detect and notify caregivers when older adults fell, alarms that could detect flooding or leaking water, and sensors that alerted the caregivers when doors were left open. They reported that bed sensors alerted caregivers when care recipients rose to answer telephone calls, reducing the need to stop other tasks to attend to the calls. 40 Dupuy and Sauzéon 38 employed motion, mattress, and gait sensors linked to digital tablets to detect falls, measure older adults’ day-to-day motion activities, and provide updates to paid caregivers. Dupuy et al 39 used similar sensor technologies and tablets to monitor activities. For example, a sensor would be set up by the front door to trigger an alarm when an older adult wanders or leaves the door open. Dupuy et al 39 reported mixed impacts of sensors and tablets on paid caregiver burden. The MBI indicated no significant subjective benefit (eg, in emotional exhaustion), while the IADL support scale indicated that sensor notifications attenuated burdens associated with supporting instrumental ADLs. 39

Socialization Enhancement Technologies

Seven articles examined the use of technologies that enhance socialization. In addition to describing sensor and monitoring systems, the 2 articles by Dupuy et al 39 and Dupuy and Sauzéon 38 also described the use of tablets to promote older adults’ social participation. Tablets were used to make social networks more accessible by enabling video calling and collaborative gaming, simplifying the electronic mailing system, and notifying older adults of upcoming social events in the community.38,39

Five articles assessed the use of social or companion robots to enhance social interactions or provide behavioral interventions.42-46 Paro is a seal-like robotic pet and was the most mentioned robot model, assessed in 3 articles.42,44,46 Other types of robots included a humanoid social communication robot called Kabochan that was designed to promote cognitive function 46 and a social robot called Matilda, which had communicative and singing capabilities. 45 Articles reported that social robots could reduce caregiver stress,42,46 make tasks easier, 44 reduce workload, save time, and increase productivity for paid caregivers. 45 However, Kolstad et al 44 reported that the use of robots also required additional time and effort from paid caregivers, and Chen et al 43 suggested that increased workload associated with the adoption of new robots may be a reason for the lack of positive effects reported by caregivers.

Paid Caregivers’ Views on Assistive Technologies

Paid caregivers expressed a range of perspectives on the impacts of assistive technology on their work. One recurring theme was ways that technologies could make caregivers’ duties easier. Participants interviewed in a study of sensor and monitoring technology described the system reducing the need for direct supervision and promoting older adults’ independence, thereby freeing some time and improving job satisfaction. 40 Participants working with social robots often described positive impacts due to the devices calming agitated older adults, which reduced caregivers’ stress and could lower workload and improve productivity.42,44,45 One caregiver explained that when older adults were interacting with robots, it allowed caregivers to work on other tasks or rest. 45

Caregivers’ perspectives on assistive technologies were not always positive, and some articles reported mixed or negative views. Caregivers identified perceived inadequacies that hindered the effectiveness of grab bars, walkers, and mats and increased risk of injury due to their incompatibility with constrained spaces in care recipients’ homes. 36 One caregiver explained,

[I wish there was] some way that we could get equipment that was portable enough, small enough, to manage these clients in an average, normal bathroom . . . Hoyer lifts are a wonderful thing if you’ve got 4 feet of space to get it through, [but in a bathroom] it’s not very practical.36(p7)

While paid caregivers often described monitoring technologies positively, they were conscious of imperfections in technologies and feared being blamed for accidents. 37 Some participants interviewed in the study by Hall et al 37 described how bed-monitoring systems not only improved confidence and coordination of activities but also led to a higher frequency of alarms alerting them for assistance and contributed to a sense of overburden. Similarly, the study by Lauriks et al 41 investigating the effects of various automated sensor technologies reported a negative evaluation of “work circumstance appreciation” during the implementation phase, without benefiting job satisfaction or workload. Social robots were also the subject of mixed perceptions. While paid caregivers appreciated beneficial impacts, some feared being replaced by robots that are capable of being active 24 hours per day, as well as of having their performance tracked by such technology. 45 Caregivers also expressed concerns about the cost and lack of funding for social robots at long-term care facilities. 42

Discussion

Demand for paid caregivers to support the aging population is increasing, but the workforce faces shortages, and building a stable and effective workforce is crucial.2,3,6,10,21,22 Expanded use of assistive technologies is an emerging strategy to reduce caregiver burden, but much of the literature focuses on family and friend caregivers.15,18,19 To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first scoping review to provide an overview of literature that examines the use of assistive technology to reduce burdens on paid caregivers working with older adults.

The review found that the body of recent literature examining impacts of assistive technologies on paid caregivers is small and fragmented in ways that preclude rigorous evaluation of the effectiveness of assistive technology for reducing paid caregiver burdens. Only 15 articles published on this topic from 2017 to 2022 were identified. The articles focus on several types of assistive technology, which impact different aspects of paid caregiving and are not necessarily comparable with each other. For example, physical and mobility aids primarily impact giving older adults support with ADLs, while sensor and monitoring technologies impact time spent on supervising clients, and social robots reduce disruptive behaviors among clients with dementia. The articles also report on studies that use a variety of methodological approaches, and there are only 2 small randomized controlled trials, which does not permit rigorous comparison of results across studies or conducting syntheses.

While the body of literature is not extensive enough to evaluate efficacy, it does provide a starting point for understanding how several types of assistive technology impact paid caregivers working with older adults. Articles consistently reported tangible benefits that physical aids, including grab bars and handrails,34,36 bidet seats, 35 and transfer devices,32,33 provided in reducing physical strain associated with caregiving tasks. These devices also helped paid caregivers complete their tasks more efficiently and decreased anxiety about safety. The main negative aspect reported in relation to physical and mobility aids was that they were sometimes incompatible with the space available in older adults’ homes. 36 These findings are encouraging, as physically demanding repetitive motion is linked with the risk of work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs) and injuries are a commonly reported health issue for PSWs and other healthcare personnel.21,47 Similarly, clients and caregivers identify bathrooms as unsafe spaces in homes, 48 and perineal care is a physically demanding task 35 that could contribute to WMSD. Supporting mobility of older adults, transfers between bed and wheelchairs, and toileting are essential parts of ADLs, and over time, the widespread use of suitable devices could offset significant physical burdens and injury risks faced by paid caregivers.

The articles about sensor and monitoring systems and socialization enhancement technologies also consistently reported beneficial impacts on paid caregivers. Studies found that automated lighting 41 and sensor alarms 40 improved safety of older adults, reducing the need for intervention by paid caregivers. Monitoring technologies, such as bed-monitoring systems and vital tracking devices, were found to improve staff confidence and job satisfaction and enable them to allocate their attention more efficiently.37,40 However, some articles reported negative effects on paid caregivers’ work environment appreciation, 41 increased feelings of being overburdened by frequent or false alarms, or worries about being blamed for failures. 37 These findings are consistent with those reported in Marasinghe’s systematic review, 15 that assistive technologies could heighten work-related burdens when caregivers monitor older adults more closely.

Like monitoring technology, socialization enhancement technologies (and social robots in particular) were noted for their ability to reduce stress,42,46 enhance productivity, 45 and contribute to a more positive caregiving experience. 44 Li-mitations and flaws of social robots were also highlighted in several articles. Social robots required effort to integrate into caregiving, 45 and some paid caregivers expressed mistrust or fears about the technology.42,45 These findings align with those in related literature on family and friend caregivers.15,16 It is also important to note that social robots have been widely studied in mental health and aged care, particularly in the context of dementia, 46 and all 5 articles reviewed here about impacts of social robots pertain to paid caregivers of older adults with dementia.42-46 The applicability of insights about benefits of social robots may be suited to long-term care facilities, where clients with dementia are common, rather than home care services.

Implications for Policy and Research

While the findings of this scoping review are not sufficient in themselves to guide policy, the literature overview suggests some preliminary insights about actions that may help optimize beneficial impacts on paid caregivers. The mixed perception of assistive technologies reported in some articles may be due in part to additional effort required while implementing new technologies. Difficult transitions during implementation could be eased by providing appropriate training and supports, particularly with the more complex technologies, such as sensor and monitoring systems and social robots.38,41,43,44 Policies could also assist with integration of physical and mobility aids. Some Canadian provinces offer grants or tax incentives for home modifications to support aging in place, which could be applied to installation of handrails, grab bars, and bidet seats. Adoption of similar supports in jurisdictions that do not already offer them would help offset costs involved in personalizing the use of assistive devices for the unique situations and needs of older adults whom paid caregivers serve. 36

Importantly, this scoping review reveals several gaps in the literature on the potential of assistive technologies to reduce paid caregiver burdens. As described earlier, none of the 3 types of assistive technology has a robust-enough body of literature to permit rigorous evaluation of efficacy in the context of paid caregiving. Furthermore, studies are required to provide essential data on the impacts of physical and mobility aids, sensor and monitoring systems, and social enhancement technology on paid caregivers’ physical burdens, stress, and job satisfaction. Some potentially important assistive technologies are also absent from the literature describing impacts on paid caregivers. One example that was not captured in the review and warrants attention is electronic medication management technology. 49 Medication management is an essential aspect of providing care to older adults who have chronic conditions, and future studies could explore the impact of medication dispensers on caregiver burden, medication adherence, and overall healthcare outcomes for older adults.

Finally, only 1 of the reviewed articles specifically examined the impacts of assistive technologies on turnover among paid caregivers. 43 Workload and injury are important reasons for paid caregivers to leave their employment,13,22,50 and additional research is needed that examines relationships between the use of assistive technology in the care of older adults and turnover rates among paid caregivers. Such research will be challenging, as multiple factors potentially contribute to paid caregiver turnover, but well-designed studies would make valuable contributions in this area.

Limitations

This scoping review has several limitations. Although the team met frequently to provide input into the review process, the decision to have only 1 member screen articles and chart data, along with the time constraints on carrying out the review, may have resulted in the omission of relevant articles. Also, articles reporting results of studies conducted in English-speaking countries, such as Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America, constitute over half (53.3%) of the reviewed literature. It is possible that the requirement for included articles to be available in English resulted in omission of relevant articles published in other languages. Finally, all but one 34 of the included studies were conducted in high-income countries, and the findings may not be applicable to the work of paid caregivers in low- and middle-income countries.

Conclusion

The overview this scoping review offers is encouraging and suggests that several types of assistive technology have the potential to reduce some of the burdens that paid caregivers working with older adults experience. Further research is needed to fully examine the efficacy of these technologies for supporting paid caregivers and understanding how they impact turnover among workers providing care for older adults.

Footnotes

Data Availability Statement: The data used in this scoping review were obtained from a comprehensive search of PubMed, ASSIA, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Ovid MEDLINE, and Ovid Embase databases, as well as searches of reference lists from relevant studies. The criteria for inclusion in the review were studies published in English between January 2017 and December 2022 that reported on assistive technologies for paid caregivers. A complete list of the studies included in the review is provided in the reference list.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Patrick Patterson  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5538-1723

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5538-1723

Norma Chinho  https://orcid.org/0009-0001-7991-4002

https://orcid.org/0009-0001-7991-4002

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Ageing and health. Accessed August 5, 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health

- 2. Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Who Cares? Attracting and Retaining Care Workers for the Elderly. OECD Publications; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Global Coalition on Aging, Home Instead. Building the caregiving workforce our aging world needs. Accessed November 29, 2023. https://globalcoalitiononaging.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/GCOA_HI_Building-the-Caregiving-Workforce-Our-Aging-World-Needs_REPORT-FINAL_July-2021.pdf

- 4. Atella V, Piano Mortari A, Kopinska J, et al. Trends in age-related disease burden and healthcare utilization. Aging Cell. 2019;18(1):e12861. doi: 10.1111/acel.12861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shim SH, Kang HS, Kim JH, Kim DK. Factors associated with caregiver burden in dementia: 1-year follow-up study. Psychiatry Investig. 2016;13(1):43-49. doi: 10.4306/pi.2016.13.1.43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Faronbi JO, Faronbi GO, Ayamolowo SJ, Olaogun AA. Caring for the seniors with chronic illness: the lived experience of caregivers of older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;82:8-14. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2019.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Visconti C, Neiterman E. Shifting to primary prevention for an aging population: a scoping review of health promotion initiatives for community-dwelling older adults in Canada. Cureus. 2021;13(8):e17109. doi: 10.7759/cureus.17109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Government of Canada. Aging and chronic diseases: a profile of Canadian seniors. Accessed July 11, 2022. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/aging-chronic-diseases-profile-canadian-seniors-report.html

- 9. Kelly C, Bourgeault IL. The personal support worker program standard in Ontario: an alternative to self-regulation? Healthc Policy. 2015;11(2):20-26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Saari M, Patterson E, Kelly S, Tourangeau AE. The evolving role of the personal support worker in home care in Ontario, Canada. Health Soc Care Community. 2018;26(2):240-249. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stall NM, Campbell A, Reddy M, Rochon PA. Words matter: the language of family caregiving. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(10):2008-2010. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brophy J, Keith M, Hurley M. Breaking point: violence against long-term care staff. New Solut. 2019;29(1):10-35. doi: 10.1177/1048291118824872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Estabrooks CA, Straus S, Flood CM, et al. Restoring trust: COVID-19 and the future of long-term care. Accessed November 28, 2023. https://rsc-src.ca/sites/default/files/LTC%20PB%20%2B%20ES_EN_0.pdf

- 14. Zeytinoglu IU, Denton M, Brookman C, Davies S, Sayin FK. Health and safety matters! Associations between organizational practices and personal support workers’ life and work stress in Ontario, Canada. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):427. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2355-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marasinghe KM. Assistive technologies in reducing caregiver burden among informal caregivers of older adults: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2016;11(5):353-360. doi: 10.3109/17483107.2015.1087061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wilkowska W, Offermann-van Heek J, Laurentius T, Bollheimer LC, Ziefle M. Insights into the older adults’ world: concepts of aging, care, and using assistive technology in late adulthood. Front Public Health. 2021;9:653931. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.653931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. World Health Organization. Assistive technology. Accessed August 15, 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/assistive-technology

- 18. Wang S, Bolling K, Mao W, et al. Technology to support aging in place: older adults’ perspectives. Healthcare. 2019;7(2):60. doi: 10.3390/healthcare7020060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lindeman DA, Kim KK, Gladstone C, Apesoa-Varano EC. Technology and caregiving: emerging interventions and directions for research. Gerontol. 2020;60(suppl 1):S41-S49. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mortenson BW, Demers L, Fuhrer MJ, et al. Effects of a caregiver-inclusive assistive technology intervention: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatrics. 2018;18(1):97. doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0783-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zagrodney K, Saks M. Personal support workers in Canada: the new precariat? Healthc Policy. 2017;13(2):31-39. doi: 10.12927/hcpol.2017.25324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marrocco F, Coke A, Kitts J. Ontario’s long-term care COVID-19 commission: final report. Accessed July 3, 2022. https://files.ontario.ca/mltc-ltcc-final-report-en-2021-04-30.pdf

- 23. Cohen M, Kiran T. Closing the gender pay gap in Canadian medicine. CMAJ. 2020;192(35):E1011. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.200375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hapsari AP, Ho JW, Meaney C, et al. The working conditions for personal support workers in the Greater Toronto Area during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed-methods study. Can J Public Health. 2022;113(6):817-833. doi: 10.17269/s41997-022-00643-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Denton M, Zeytinoglu IU, Brookman C, Davies S, Boucher P. Personal support workers’ perception of safety in a changing world of work. Saf Health. 2018;4(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s40886-018-0069-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Czuba KJ, Kayes NM, McPherson KM. Support workers’ experiences of work stress in long-term care settings: a qualitative study. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2019;14(1):1622356. doi: 10.1080/17482631.2019.1622356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. George AS, McConville FE, de Vries S, Nigenda G, Sarfraz S, McIsaac M. Violence against female health workers is tip of iceberg of gender power imbalances. BMJ. 2020;371:m3546. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3546 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19-32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco A, Khalil H. Scoping reviews. In: Aromataris E., Munn Z. eds. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2020. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-12 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467-473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sun C, Buchholz B, Quinn M, Punnett L, Galligan C, Gore R. Ergonomic evaluation of slide boards used by home care aides to assist client transfers. Ergonomics. 2018;61(7):913-922. doi: 10.1080/00140139.2017.1420826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hwang J, Ari H, Matoo M, Chen J, Kim JH. Air-assisted devices reduce biomechanical loading in the low back and upper extremities during patient turning tasks. Appl Ergon. 2020;87:103121. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2020.103121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Phetsitong R, Vapattanawong P. Reducing the physical burden of older persons’ household caregivers: the effect of household handrail provision. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(4):2272. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19042272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. King EC, Boscart VM, Weiss BM, Dutta T, Callaghan JP, Fernie GR. Assisting frail seniors with toileting in a home bathroom: approaches used by home care providers. J Appl Gerontol. 2019;38(5):717-749. doi: 10.1177/0733464817702477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. King EC, Holliday PJ, Andrews GJ. Care challenges in the bathroom: the views of professional care providers working in clients’ homes. J Appl Gerontol. 2018;37(4):493-515. doi: 10.1177/0733464816649278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hall A, Wilson CB, Stanmore E, Todd C. Implementing monitoring technologies in care homes for people with dementia: a qualitative exploration using Normalization Process Theory. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017;72:60-70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dupuy L, Sauzéon H. Effects of an assisted living platform amongst frail older adults and their caregivers: 6 months vs. 9 months follow-up across a pilot field study. Gerontechnology. 2020;19(1):16-27. doi: 10.4017/gt.2020.19.1.003.00 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dupuy L, Froger C, Consel C, Sauzéon H. Everyday functioning benefits from an assisted living platform amongst frail older adults and their caregivers. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:302-302. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rondon-Sulbaran J, Daly Lynn J, McCormack B, Ryan A, Martin S. The transition to technology-enriched supported accommodation (TESA) for people living with dementia: the experience of formal carers. Ageing Soc. 2020;40(10):2287-2308. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X19000588 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lauriks S, Meiland F, Osté JP, Hertogh C, Dröes R-M. Effects of assistive home technology on quality of life and falls of people with dementia and job satisfaction of caregivers: results from a pilot randomized controlled trial. Assist Technol. 2020;32(5):243-250. doi: 10.1080/10400435.2018.1531952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Moyle W, Bramble M, Jones C, Murfield J. Care staff perceptions of a social robot called Paro and a look-alike Plush Toy: a descriptive qualitative approach. Aging Ment Health. 2018;22(3):330-335. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2016.1262820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chen K, Lou VW, Tan KC, Wai MY, Chan LL. Burnout and intention to leave among care workers in residential care homes in Hong Kong: technology acceptance as a moderator. Health Soc Care Community. 2021;29(6):1833-1843. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kolstad M, Yamaguchi N, Babic A, Nishihara Y. Integrating socially assistive robots into Japanese nursing care. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2020;272:183-186. doi: 10.3233/shti200524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Khaksar SMS, Khosla R, Singaraju S, Slade B. Carer’s perception on social assistive technology acceptance and adoption: moderating effects of perceived risks. Behav Inf Technol. 2021;40(4):337-360. doi: 10.1080/0144929X.2019.1690046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chen K, Lou VW, Tan KC, Wai MY, Chan LL. Effects of a humanoid companion robot on dementia symptoms and caregiver distress for residents in long-term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(11):1724-1728. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.05.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Oranye NO, Wallis B, Roer K, Archer-Heese G, Aguilar Z. Do personal factors or types of physical tasks predict workplace injury? Workplace Health Saf. 2016;64(4):141-151. doi: 10.1177/2165079916630552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tong CE, Sims-Gould J, Martin-Matthews A. Types and patterns of safety concerns in home care: client and family caregiver perspectives. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28(2):214-220. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzw006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Faisal S, Ivo J, Patel T. A review of features and characteristics of smart medication adherence products. Can Pharm J. 2021;154(5):312-323. doi: 10.1177/17151635211034198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chamberlain SA, Hoben M, Squires JE, Cummings GG, Norton P, Estabrooks CA. Who is (still) looking after mom and dad? few improvements in care aides’ quality-of-work life. Can J Aging. 2019;38(1):35-50. doi: 10.1017/S0714980818000338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]