Abstract

When nursing homes experience a shortage in directly employed nurses and nursing aides, they may rely on temporary workers from staffing agencies to fill this gap. This article examines trends in the use of staffing agencies among nursing homes during the prepandemic and COVID-19 pandemic era (2018–22). In 2018, 23 percent of nursing homes used agency nursing staff, accounting for about 3 percent of all direct care nursing hours worked. When used, agency staff were commonly present for ninety or fewer days in a year. By 2022, almost half of all nursing homes used agency staff, accounting for 11 percent of all direct care nursing staff hours. Agency staff was increasingly used to address chronic staffing shortages, with 13.8 percent of nursing homes having agency staff present every day. Agency staffing was 50–60 percent more expensive per hour than directly employed nursing staff, and nursing homes that used agency staff often had lower five-star ratings. Policy makers need to consider postpandemic changes to the nursing home workforce as part of nursing home reform, as increased reliance on agency staff may reduce available financial resources to increase nursing staff levels and improve quality of care.

During the last few years, the Biden administration and other stakeholders have called for more stringent oversight of the nursing home industry.1,2 Those efforts center on increasing nursing staff levels, which has been an area of focus of nursing homes in the context of COVID-19.3 Even before the pandemic, recruiting and retaining nursing staff was a major challenge.4 Lower retention and higher turnover among nursing staff is associated with lower quality and more consumer complaints.5–7 Wages for registered nurses and licensed practical nurses in nursing homes are generally lower than in other health care fields. In addition, for nurse aides, employment in retail, fast food, tourism, distribution centers, or similar industries are attractive alternatives to working in a nursing home.4,8

The COVID-19 pandemic and strong labor market demand after the initial lockdowns ended only made these workforce challenges more difficult.9,10 From 2019 to 2020, an estimated 8.4 percent of the nursing home workforce left the industry.11 Many nursing home workers left their jobs because of the limited availability of personal protective equipment, lack of rapid COVID-19 testing, fear of COVID-19, and being overworked.12,13 And many did not need to look far for alternative employment, as across the broader economy there were about 1.5–1.8 job openings for every person hired from the summer of 2021 to 2023.14 This led to more than one in three nursing homes reporting a nursing staff shortage at the start of 2022, which only improved to slightly better than one in four nursing homes reporting shortages by the start of 2023, even with the COVID-19 public health emergency declaration officially ending on May 11, 2023.15

In response, many nursing homes have turned to staffing agencies, which provide temporary workers as a potential means of addressing the gaps in staffing. Agency staff may allow a nursing home to operate when there are not enough directly employed nursing staff to adequately care for residents, such as when someone is on vacation or calls out sick. However, agency staff are temporary workers. Compared with directly employed workers, agency nursing staff are less familiar with the facility’s policies, layout, and residents. As a result, residents may be less likely to receive person-centered care, and as a consequence, quality of care may decline. In addition, the use of agency staff has significantly higher costs than employing staff directly, resulting in there being fewer financial resources available for the facility to invest in staffing and other quality improvements. The potential lack of familiarity of agency staff with the facility, coupled with their higher wages, could have a negative impact on the morale of directly employed staff.16,17

As the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and states consider implementing new nursing staff regulations, they need information and awareness of the current nursing home workforce challenges. Nursing staff regulations that increase staffing levels will require nursing homes to have access to workers to fill new positions, as well as to replace existing staff that make career changes or retire. To provide this context, it is vital to understand the role of agency staff in nursing home staffing, finances, and quality, an issue that has not been examined using recent data. This article examines the role of agency staff among direct care nursing staff, using data from 2018 through 2022, the most recent period for which data are available.

Study Data And Method

Data And Study Population

This study used three publicly available CMS data sets: the Payroll-Based Journal (PBJ) data, Nursing Home Compare Archive data, and Medicare Cost Reports.

When submitting PBJ data, CMS requires nursing homes to report an identification number, a job category (for example, registered nurse), the number of hours worked, and whether the worker is agency staff or directly employed by the nursing home on a daily basis for each worker. This information is aggregated to facility-day level and made publicly available. The public PBJ data contain daily information on the number of hours worked by directly employed and agency nursing staff for all Medicare and Medicaid certified nursing homes in the United States. The PBJ data were used to calculate on a daily basis whether a nursing home had used any agency nursing staff, the number of hours worked by agency nursing staff, and the total number of hours worked by all nursing staff. To obtain each nursing home’s five-star rating and restrict the sample to the freestanding (as opposed to hospital-based) nursing homes, we merged Nursing Home Compare Archive data with the PBJ data.

The first year for which PBJ data are available is 2017. Many nursing homes needed to transition to new information systems to comply and properly report staffing data to CMS, causing the 2017 data to have more outliers and more nursing homes not reporting staffing data than other years. Therefore, the analytic sample reflects the period 2018–22. After we excluded nursing home days with extreme values,18 the 2018–22 period averaged 14,435 daily nursing home observations (excluding the first quarter of 2020). In the first quarter of 2020, reporting PBJ data to CMS was optional; the average daily number of nursing homes reporting in the first quarter of 2020 was 11,770.

Nursing labor costs were obtained from Medicare Cost Reports. The Medicare Cost Reports are the only national source of financial information on nursing homes and include the labor costs associated with directly employed and agency nursing staff. About 98 percent of all freestanding nursing homes are required to complete a Medicare Cost Report on an annual basis.

Similar to other studies,19 when analyzing labor costs, observations were restricted to full-year cost reports with at least one resident. There were 64,992 Medicare Cost Reports in the study population that had fiscal year end dates in 2018–22. The number of nursing home observations were 13,458 in 2018, 13,359 in 2019, 13,567 in 2020, 13,345 in 2021, and 11,263 in 2022. The total number of observations in 2022 was lower than in other years because not all Medicare Cost Reports are currently filed and processed by CMS.

Finally, to examine the relationship with the use of agency staff and CMS’s Five-Star Quality Rating System, the PBJ data for the fourth quarter of 2019 were merged with contemporaneous star ratings reported in January 2020. This period was used to reflect normal nursing home operations. The COVID-19 pandemic caused many interruptions to normal nursing home operations, which included many nursing homes reporting being short staffed and staff calling out, some states temporarily suspending staffing regulations, and updates to the star ratings being suspended.9,20 The resulting study sample included 14,240 nursing homes.

Directly Employed And Agency Staff

The daily PBJ data provide the total number of hours worked by directly employed and agency nursing staff. For each day, the share of nursing homes using agency staff and the share of hours worked by agency staff were calculated. These outcomes were examined only for nursing staff assigned to direct care, excluding nursing staff assigned to administrative duties (for example, director of nursing). Furthermore, we reviewed each of these outcomes for direct care nursing staff in aggregate and for the three types of nursing staff (specifically, registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and nurse aides).

Labor Costs

Labor costs were sourced from Worksheet S-3, Part V of the Medicare Care Cost Reports. The Medicare Cost Reports contain the wage compensation and fringe benefit cost associated with directly employed nurses and nurse aides. When combined with the number of hours paid, labor costs of directly employed nursing staff reflect their total average hourly cost to the nursing home. For agency staff, the total expenditure amount and hours paid for agency staff are reported. By dividing these expenditures by hours paid, the labor cost reflects the average hourly rate paid to the staffing agency. Labor costs were not adjusted for inflation to reflect the costs incurred by nursing homes, making labor costs comparable to other contemporaneous financial and wage data.

CMS’ Five-Star Quality System Ratings

On the Care Compare website (formerly Nursing Home Compare), CMS publicly reports quality information about nursing homes. This information is summarized into star ratings.18

This study uses the overall, health inspection, and quality measure star ratings. The overall star rating is a composite measure taking into account all the other star ratings. The health inspection rating is based on deficiencies issued by state surveyors during recertification and complaint inspections when a nursing home is found to be out of substantial compliance with federal regulations. The quality measure rating is calculated from resident-level quality information sourced from the Minimum Data Set and Medicare claims data (for example, pressure ulcers, rehospitalization).

Analysis

To understand the trends in the use of agency staff, this study examined the share of nursing homes using any agency staff and the share of hours worked by agency staff from the period 2018–22 for the entire nation. This information was graphically reported, using a fourteen-day moving average. A moving average was used because there can be significant daily variation.21 The daily average share of nursing homes using agency staff and the share of hours worked by agency staff in 2022 is also reported by state.

Agency staff may be used to fill in gaps in nursing staff, such as during short-term occupancy spikes or when directly employed nursing staff are sick or on vacation. However, agency staff may also become a substitute for directly employed workers when there are chronic worker shortages, and hence the use of agency staff becomes persistent. To assess these trends, the number of days any agency staff was used in 2018 and 2022 was calculated and compared.

Next, to analyze the trend in labor costs, median labor costs for each nursing staff type were calculated for each year from 2018 to 2022. Medians were used to account for potential outliers in the Medicare Cost Reports.19 We reported median labor costs for directly employed nursing staff for all nursing homes. Because some nursing homes do not use agency staff, we also reported median labor costs for directly employed nursing staff for the subset of nursing homes that used agency staff.

Finally, to assess whether the use of agency staff is associated with quality, the average star ratings in early 2020 were compared with the use of any agency staff in the fourth quarter of 2019. This analysis of star ratings provides insight into whether nursing homes that use agency staff have lower or higher star ratings, but it does not identify whether the use of agency staff was the cause of the star rating, as opposed to other factors that might be associated with the use of agency staff.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the Medicare Cost Reports have been criticized because data are reported by the facility. In the period studied, these labor costs were subject to audit, and deliberate misrepresentation or falsification of information is punishable by law.19 Labor costs in Medicare Cost Reports were not used by CMS for public reporting or determining payment rates, making them less likely to be deliberately manipulated. Furthermore, the Medicare Cost Reports are the only national source of labor costs at the facility level, and have been used by others to examine nursing home costs.22 Second, the Medicare Cost Reports did not report labor costs for agency staff unless the nursing home used agency staff. Therefore, labor costs reflect what is being paid by nursing homes that used agency staff, not what it may cost a nursing home to use agency staff if they needed it. Third, multiple factors can affect star ratings, and the analysis of the use of agency staff and star ratings only examines associations. Any difference in the use of agency staff and star ratings is suggestive of a relationship, but whether agency staff led to the star rating cannot be assessed using our method, as we do not account for other potential factors associated with the use of agency staff and quality. Fourth, some graphical representations were based on fourteen-day moving averages. This was done to reduce the noise associated with daily variation in the use of agency staff. The overall trends are not sensitive to using alternative number of days for the moving average (for example, seven-day moving average). Finally, the reporting of the PBJ data was optional for the first quarter of 2020, with approximately 18 percent of nursing homes failing to report staffing data. We have no reason to suspect that nursing homes that did and did not report data are different, but we acknowledge this slight inconsistency in the first quarter of 2020.

Study Results

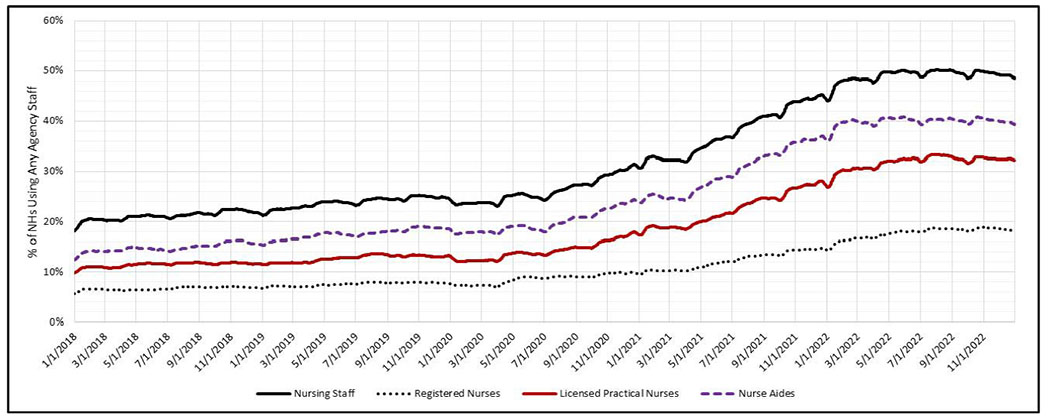

In 2018 and 2019, the share of nursing homes using agency staff was consistent over time (exhibit 1). On average, during this period, 22.5 percent of nursing homes used any direct care agency nursing staff, with 7.1 percent of nursing homes using agency registered nurses, 12.1 percent using agency licensed practical nurses, and 16.2 percent using agency nurse aides. The COVID-19 pandemic was a clear inflection point, with the share of nursing homes using agency staff steadily increasing until plateauing in 2022. On average during 2022, 49.1 percent of nursing homes used any direct care agency nursing staff, with 17.8 percent using agency registered nurses, 31.9 percent using agency licensed practical nurses, and 40.0 percent using agency nurse aides.

Exhibit 1. Share of U.S. Nursing Homes Using Direct Care Agency Nursing Staff, 2018-2022.

Source: Authors’ Calculations Using Payroll-Based Journal Data.

Notes: The share of freestanding nursing homes using agency staff was calculated on a daily basis. To account for the significant daily variation, the 14-day moving average is reported. The daily sample size average 14,435 nursing homes for all periods excluding the first quarter of 2020 which averaged 11,770 nursing homes.

There was also significant variation in the use of agency staff across states (see online appendix exhibit 1).23 On average in 2022, Vermont (86.6 percent), New York (73.0 percent), Maryland (70.9 percent), and Pennsylvania (70.5 percent) had more than 70 percent of nursing homes using any direct care agency nursing staff. In contrast, Oklahoma (29.9 percent); Alabama (28.0 percent); Washington, D.C. (26.2 percent); and Arkansas (16.3 percent) had fewer than 30 percent of nursing homes using any direct care agency nursing staff.

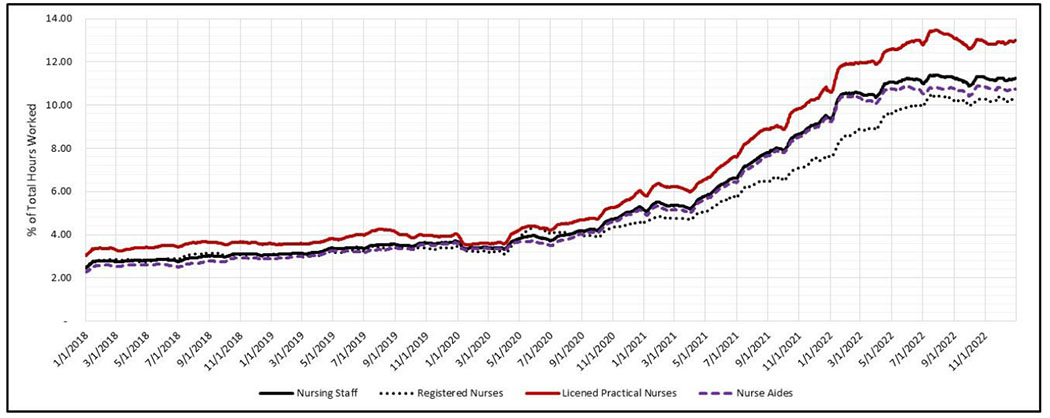

The share of hours worked by agency staff remained stable in 2018 and 2019, averaging 3.2 percent for direct care nursing staff (exhibit 2). The share of hours worked by agency staff increased throughout the pandemic, plateauing around January 2022 for nurse aides and the summer of 2022 for registered nurses and licensed practical nurses. By 2022, 11 percent of nursing staff hours worked were from agency staff. The share of hours worked was slightly higher for licensed practical nurses (12.7 percent) and lower for registered nurses (9.8 percent). In 2022, agency staff accounted for more than 20 percent of direct care nursing staff hours in Vermont (28.1 percent), Montana (22.3 percent), and Maine (21.5 percent), whereas Arkansas (2.9 percent) and Washington, D.C. (3.1 percent), had the lowest use of agency staff (see appendix exhibit 1).23

Exhibit 2. Share of Hours Worked By Agency Nursing Staff in U.S. Nursing Homes, 2018-2022.

Source: Authors’ Calculations Using Payroll-Based Journal Data.

Notes: The share of hours worked by agency staff is the total number of agency hours divided by total number of nursing staff hours. To account for the significant daily variation, the 14-day moving average is reported. The daily sample size average 14,435 nursing homes for all periods excluding the first quarter of 2020 which averaged 11,770 nursing homes.

There was a clear trend among nursing homes using any agency staff to increase the number of days in which they rely on agency staff (exhibit 3). In 2018, 44.7 percent of nursing homes used agency staff for ninety days or less (exhibit 3), with 5.7 percent of nursing homes using agency staff every day. By 2022, only 19.4 percent of nursing homes that used agency staff used them for ninety days or less. The percentage of nursing home using agency staff on all days in 2022 increased to 13.8 percent, with 20.2 percent of nursing homes using agency staff for all but thirty days in 2022.

Exhibit 3. Distribution of U.S. Nursing Homes by Number of Days Agency Staff are Utilized, 2018 and 2022.

Source: Authors’ Calculations Using Payroll-Based Journal Data in 2018 and 2022.

Notes: Among nursing homes that used agency staff, the exhibit reports the percent of nursing homes by the number of days they used agency staff. The sample is restricted to nursing homes that reported PBJ data for all days in the calendar year. The sample size is 6,636 nursing home in 2018 and 10,258 nursing homes in 2022.

Nursing home labor costs increased from 2018 to 2022 for both directly employed and agency nursing staff (exhibit 4). For directly employed staff in all nursing homes, median labor costs per hour increased 23.5 percent for registered nurses, 29.3 percent for licensed practical nurses, and 37.6 percent for nurse aides. Among nursing homes using agency staff, median labor costs grew at a slightly slower rate as a result of these nursing homes having higher labor costs in 2018. Labor costs for agency staff grew at a slightly faster rate than for directly employed workers during the same period: 28.5 percent for registered nurses, 34.0 percent for licensed practical nurses, and 40.1 percent for nurse aides.

Exhibit 4.

U.S. Nursing Homes’ Median Hourly Labor Cost Associated with Nursing Staff, 2018–2022

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | % Change (2018–2022) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Directly Employed Nursing Staff: All Nursing Homes | ||||||

| Registered Nurses | $36.79 | $37.74 | $39.68 | $41.85 | $45.45 | 23.5% |

| Licensed Practical Nurses | $27.80 | $28.69 | $30.36 | $32.39 | $35.96 | 29.3% |

| Nurse Aides | $16.10 | $16.87 | $18.19 | $19.66 | $22.15 | 37.6% |

| Directly Employed Nursing Staff: Nursing Homes Using Agency Staff | ||||||

| Registered Nurses | $38.23 | $39.41 | $41.42 | $42.67 | $46.51 | 21.6% |

| Licensed Practical Nurses | $29.20 | $29.20 | $31.63 | $33.31 | $36.96 | 26.6% |

| Nurse Aides | $17.46 | $18.18 | $19.27 | $20.40 | $22.82 | 30.7% |

| Agency Nursing Staff | ||||||

| Registered Nurses | $54.00 | $55.02 | $60.12 | $64.72 | $69.38 | 28.5% |

| Licensed Practical Nurses | $42.06 | $44.20 | $48.35 | $52.77 | $56.35 | 34.0% |

| Nurse Aides | $25.93 | $27.22 | $31.00 | $34.20 | $36.34 | 40.1% |

Source: Authors’ calculations from full-year Medicare Cost Reports with fiscal year end dates of 2018 through 2022.

Notes: The median labor cost reflects the wage and fringe cost per hour paid to directly employed nursing staff and the cost per hour to the nursing home for agency nursing staff. Only observations reporting data were used in the calculation. The labor costs have not been inflation adjusted. The total number of eligible observations varied with fiscal year. The number of eligible observations was 13,345 to 13,567 for 2018 to 2022, and 11,263 nursing home observations in 2022. The number of observations in 2022 is lower than other years because not all Medicare Cost Reports are currently filed and processed by CMS.

Agency staff is significantly costlier than directly employed nursing staff. In 2018, compared with the median labor cost of all nursing homes, agency registered nurses cost $17.20 more per hour than directly employed registered nurses. By 2022, this difference increased to $23.93 per hour. There is a similar pattern for licensed practical nurses ($14.26 difference in 2018 versus $20.40 in 2022) and nurse aides ($9.83 in 2018 versus $14.19 in 2022). On average, from 2018 to 2022, the hourly labor cost of using agency staff relative to directly employed staff was 50 percent higher for registered nurses, 57 percent for licensed practical nurses, and 66 percent for nurse aides (data not shown).

To understand whether agency staff may be associated with quality, we examined a simple comparison of the average overall, health inspection, and quality measure star ratings in early 2020 by use of agency nursing staff in the fourth quarter of 2019 (see appendix table 2).23 These results, which do not account for other confounding factors, suggest that nursing homes that use agency staff have lower or no difference in star ratings compared with nursing homes that do not use agency staff. Agency use was associated with lower average overall and health inspection star ratings, but was generally not associated with the quality measure star rating.

Discussion

From 2018 to 2022, this study found that the share of nursing homes using any agency nursing staff to provide direct care to residents increased from 22 percent to roughly half of all nursing homes. Over the course of the same period, the share of nursing staff hours covered by agency staff increased almost 3.5-fold, going from 3.2 percent to 11 percent of hours worked. The labor market dynamics associated with the pandemic also had a significant impact on nursing home labor costs. Labor costs increased for both agency staff and directly employed staff during the pandemic. Given that the hourly labor cost of using agency staff is significantly higher than directly employing nursing staff, nursing homes were hit twice: first from overall wage increases and second from the increased reliance on more expensive agency staff. For example, for the median nursing home, the labor costs of nurse aides directly employed by the nursing home increased 37.6 percent, but as a result of some of these hours being replaced by agency staff, the overall labor cost increase for nurse aides who were previously directly employed was 44.3 percent.

This invites the question of why nursing homes did not increase wages for directly employed nursing staff earlier. Nursing homes did increase wage rates,11 but staffing agencies were able to offer even higher wage rates or more flexibility in scheduling. Nursing homes were constrained by administratively set prices from offering all staff members huge wage increases. When a retailer or restaurant faces higher labor costs, they are free to increase the prices they charge customers. In contrast, most nursing home revenue is derived from the Medicare and Medicaid programs, which have payment rates set by government entities. Thus, nursing homes could not pass on their higher labor costs by charging higher prices.

The federal government and many states offered nursing homes relief funds from 2020 through at least 2022 that could be used to pay workers higher wages. One study compared wages and employment during the pandemic across all the major health care sectors. By 2021, nursing homes had the largest wage increase of any health care sector relative to prepandemic levels, but they also had the largest relative decline in the number of workers.11 These seemingly conflicting results reflect the challenging conditions nursing homes and their staff faced during the pandemic. Nursing home workers had the highest death rate of any job in America during the early part of the pandemic because of factors such as limited personal protective equipment and the lack of rapid COVID-19 testing.12 Thus, the additional relief fund dollars were associated with higher wages for directly employed staff and greater use of costly agency staff, but staffing shortages persisted throughout the pandemic, likely as a result of the increased hazards of working in a nursing home during the pandemic.

Study findings also point to the potential changes to the role agency staff play in nursing home staff. In 2018, 48.4 percent of nursing homes never used agency staff (data not shown). Yet among nursing homes that used agency staff, just less than half (44.7 percent) used agency staff for ninety days or less. This pattern is consistent with prepandemic nursing homes primarily using agency staff to address short-term gaps in nursing staff, such as when a nursing home experiences a spike in occupancy or when directly employed nursing staff were unavailable because of illness, vacations, or short-term vacancies. However, by 2022, only 22.6 percent of nursing homes never used agency staff (data not shown) and 19.4 percent of nursing homes used agency staff for less than ninety days. Approximately 34 percent of nursing homes used agency staff for all but thirty days in 2022, with 13.8 percent of nursing homes using agency staff every day. Although additional research is needed, our results and recent media reports suggest that agency staff is now being used by nursing homes to address chronic staffing shortages.24

The trend toward using more agency staff may also have potential negative consequences for nursing home residents. Although agency staff should have the same level of skill and training as directly employed staff, agency staff may be less familiar with individual residents, the facility’s nursing team, and the building’s layout and procedures, making them less efficient than directly employed staff. Recent research also finds that direct care workers report frustration about agency staff earning higher wages and the perception that they are less responsible for ongoing care.17 Another hypothesis is that agency staff might not be consistently assigned to the same residents, potentially lessoning their ability to identify health and quality-of-life issues earlier and provide more individualized care.25 These factors may explain why the overall and health inspection ratings were lower in nursing homes that used agency staff as compared with in nursing homes that did not use agency staff. However, we found that the average quality star rating was not generally statistically different by agency use. Additional research is warranted, as our analysis, which only examined associations, does not take into consideration how agency staff use has changed since the COVID-19 pandemic.

An additional risk to residents in nursing homes using agency staff is the potential for the spread of respiratory viruses such as influenza, COVID-19, or respiratory syncytial virus. Use of agency staff may increase the number of unique workers in a nursing home. Recent work has found that more unique workers cycling in and out of a nursing home increased the likelihood of COVID-19 entering the facility.26,27 Additional research is needed to determine whether there is a relationship between the use of agency staff and the spread of respiratory viruses.

As the number of older Americans grows, the demand for workers to provide long-term services and supports will only increase. There is an urgent need for action to ensure that there is a competent and available workforce to care for nursing home residents.28 Even though the federally declared public health emergency concluded on May 11, 2023, the COVID-19 pandemic and the strength of the postpandemic labor market have significantly increased the labor cost of caring for nursing home residents. Relief dollars in many states were temporary, and even before the pandemic, Medicaid payment rates were found not to cover the cost of care.29 Without significant investment in the nursing home workforce and ensuring that nursing homes have adequate revenue to hire workers, nursing home residents may be at risk. Many of the policy recommendations around the workforce issues are discussed in a recent report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine and should be considered.2 These include assuring that nursing homes receive adequate payment to hire and retain nursing staff that are directly employed by the facility.

Conclusion

Nursing staff is a key factor in providing quality nursing home care. However, the market dynamics around nursing home staffing have changed. Before the pandemic, most nursing homes did not rely on agency staff. Since the pandemic, agency staff has become more common, is more expensive, and may be associated with lower-quality care. Given the recent push to implement more stringent nursing home oversight, including proposed regulations that would increase nursing staff levels, our findings suggest that policy makers need to consider the recent increased use of agency staff use and their higher labor costs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This research was presented at the AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting in Seattle, Washington, June 26, 2023, and the GSA 2023 Annual Scientific Meeting in Tampa, Florida, November 8, 2023. John Bowblis (Grant No. R01 AG081282), Huiwen Xu (Grant Nos. R01 AG081282 and P30 AG024832), and David Grabowski (Grant No. R01 AG070040) acknowledge grant support for this work from the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health. Bowblis and Robert Applebaum acknowledge grant support from the Ohio Long-term Care Research Project. This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the State of Ohio. In terms of other support, Bowblis has also received funds from various state agencies and the federal government to conduct research on nursing homes and advise on nursing home policy. He has also been retained as an expert witness in legal matters involving the health care and other industries. Christopher Brunt has received funds from State of Georgia’s Office of Health Strategy and Coordination to conduct research and advise on nursing home policy. Applebaum has received funds from the Ohio Department of Aging, Ohio Department of Medicaid, and AARP. David Grabowski has received support from AARP, the Analysis Group, GRAIL LLC, Health Care Lawyers PLC, and the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission.

Contributor Information

John R. Bowblis, Professor of Economics and Research Fellow, Department of Economics, Miami University, 800 E. High Street, Oxford, OH 45056.

Christopher S. Brunt, Solomons Endowed Chair and Professor of Economics, Department of Economics, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, GA 30460.

Huiwen Xu, Assistant Professor of Public Health, School of Public and Population Health, Sealy Center on Aging, University of Texas Medical Branch, 301 University Blvd., Galveston, TX 77555.

Robert Applebaum, Director of the Ohio Long-Term Care Research Project, Scripps Gerontology Center, Miami University, Oxford OH, 45056.

David C. Grabowski, Professor of Health Care Policy, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, 180 Longwood Ave, Boston, MA 02115.

Notes

- 1.White House. Fact sheet: protecting seniors by improving safety and quality of care in the nation’s nursing homes [Internet]. Washington (DC): White House; 2022. Feb 28 [cited 2024 Jan 4]. Available from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/02/28/fact-sheet-protecting-seniors-and-people-with-disabilities-by-improving-safety-and-quality-of-care-in-the-nations-nursing-homes/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The national imperative to improve nursing home quality. Honoring our commitment to residents, families, and staff [Internet]. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2022. [cited 2024 Jan 4]. Available from: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/26526/the-national-imperative-to-improve-nursing-home-quality-honoring-our [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen K, McGarry BE, Grabowski DC, Gruber J, Gandhi AD. Staffing patterns in US nursing homes during COVID-19 outbreaks. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(7):e222151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denny-Brown N, Stone D, Hays B, Gallagher D. COVID-19 intensifies nursing home workforce challenges [Internet]. Washington (DC): Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; 2020. Oct [cited 2024 Jan 4]. Available from: https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/covid-19-intensifies-nursing-home-workforce-challenges-0 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gandhi A, Yu H, Grabowski DC. High nursing staff turnover in nursing homes offers important quality information. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(3):384–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang SS, Bowblis JR. Is the quality of nursing homes countercyclical? Evidence from 2001 through 2015. Gerontologist. 2019;59(6):1044–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brunt CS, Bowblis JR. Beyond nursing staff levels: the association of nursing home quality and the five-star quality rating system’s new staffing measures. Med Care Res Rev. 2023;80(6):631–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antwi YA, Bowblis JR. The impact of nurse turnover on quality of care and mortality in nursing homes: evidence from the Great Recession. Am J Health Econ. 2018;4(2):131–63. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu H, Intrator O, Bowblis JR. Shortages of staff in nursing homes during the COVID-19 Pandemic: what are the driving factors? J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(10):1371–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen M, Goodwin JS, Bailey JE, Bowblis JR, Li S, Xu H. Longitudinal Associations of staff shortages and staff levels with health outcomes in nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2023;24(11):1755–1760.e7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cantor J, Whaley C, Simon K, Nguyen T. US health care workforce changes during the first and second years of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(2):e215217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGarry BE, Porter L, Grabowski DC. Opinion: nursing home workers now have the most dangerous jobs in America. They deserve better. Washington Post [serial on the Internet]. 2020. Jul 28 [cited 2024 Jan 4]. Available from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/07/28/nursing-home-workers-now-have-most-dangerous-jobs-america-they-deserve-better/

- 13.Suran M Overworked and understaffed, more than 1 in 4 US nurses say they plan to leave the profession. JAMA. 2023;330(16):1512–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bureau of Labor Statistics. Job openings, hires, and separations levels, seasonally adjusted [Internet]. Washington (DC): BLS; [cited 2024 Jan 4]. Available from: https://www.bls.gov/charts/job-openings-and-labor-turnover/opening-hire-seps-level.htm [Google Scholar]

- 15.AARP. AARP nursing home COVID-19 dashboard fact sheets [Internet]. Washington (DC): AARP; 2023 [last updated 2023. Dec 14; cited 2024 Jan 4]. Available from: https://www.aarp.org/ppi/issues/caregiving/info-2020/nursing-home-covid-states.html [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brazier JF, Geng F, Meehan A, White EM, McGarry BE, Shield RR, et al. Examination of staffing shortages at US nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2325993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karmacharya I, Janssen LM, Brekke B. “Let them know that they’re appreciated”: the importance of work culture on direct care worker retention. J Gerontol Nurs. 2023;49(8):7–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Design for Care Compare nursing home Five-Star Quality Rating System: technical users’ guide [Internet]. 2023. Sep[cited 2024 Jan 4]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/CertificationandComplianc/Downloads/usersguide.pdf

- 19.Bowblis JR, Brunt CS, Xu H, Grabowski DC. Understanding nursing home spending and staff levels in the context of recent nursing staff recommendations. Health Aff (Millwood). 2023;42(2):197–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGarry BE, Grabowski DC, Barnett ML. Severe staffing and personal protective equipment shortages faced by nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(10):1812–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mukamel DB, Saliba D, Ladd H, Konetzka RT. Daily variation in nursing home staffing and its association with quality measures. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(3):e222051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowblis JR. The need for an economically feasible nursing home staffing regulation: evaluating an acuity-based nursing staff benchmark. Innov Aging. 2022;6(4):igac017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.To access the appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Towhey JR. Even with its own float pool, this provider is flooded with open nursing positions. McKnight’s Long-Term Care News [serial on the Internet]. 2023. Oct 11 [cited 2024 Jan 4]. Available from: https://www.mcknights.com/news/even-with-its-own-float-pool-this-provider-is-flooded-with-open-nursing-positions/

- 25.Kennedy KA, Bowblis JR. Does higher worker retention buffer against consumer complaints? Evidence from Ohio nursing homes. Gerontologist. 2023;63(1):96–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGarry BE, Gandhi AD, Grabowski DC, Barnett ML. Larger nursing home staff size linked to higher number of COVID-19 cases in 2020. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(8):1261–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen MK, Chevalier JA, Long EF. Nursing home staff networks and COVID-19. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(1):e2015455118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mueller CA, Travers JL. Policy priorities for a well-prepared nursing home workforce. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(2):322–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. Estimates of Medicaid nursing facility payments relative to costs [Internet]. Washington (DC): MACPAC; 2023. Jan [cited 2024 Jan 4]. Available from: https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Estimates-of-Medicaid-Nursing-Facility-Payments-Relative-to-Costs-1-6-23.pdf [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.