Abstract

Background:

Palliative care professionals face emotional challenges when caring for patients with serious advanced diseases. Coping skills are essential for working in palliative care. Several types of coping strategies are mentioned in the literature as protective. However, little is known about how coping skills are developed throughout a professional career.

Aim:

To develop an explanatory model of coping for palliative care professionals throughout their professional career.

Design:

A grounded theory study. Two researchers conducted constant comparative analysis of interviews.

Setting/participants:

Palliative care nurses and physicians across nine services from Spain and Portugal (n = 21). Theoretical sampling included professionals who had not continued working in palliative care.

Results:

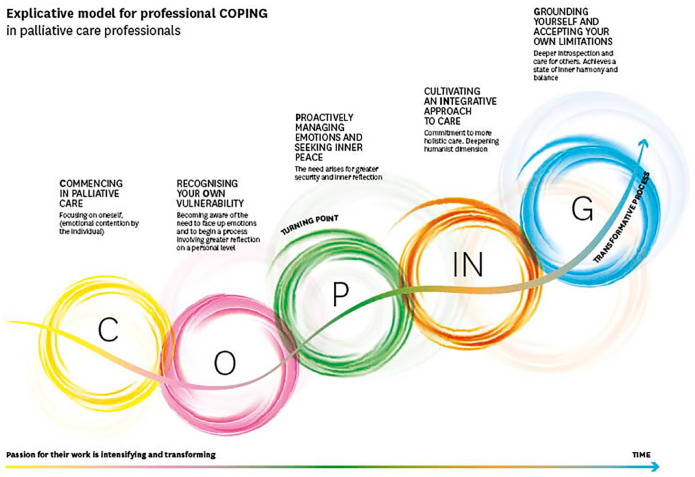

Professionals develop their coping mechanisms in an iterative five-stage process. Although these are successive stages, each one can be revisited later. First: commencing with a very positive outlook and emotion, characterized by contention. Second: recognizing one’s own vulnerability and experiencing the need to disconnect. Third: proactively managing emotions with the support of workmates. Fourth: cultivating an integrative approach to care and understanding one’s own limitations. Fifth: grounding care on inner balance and a transcendent perspective. This is a transformative process in which clinical cases, teamwork, and selfcare are key factors. Through this process, the sensations of feeling overwhelmed sometimes can be reversed because the professional has come to understand how to care for themselves.

Conclusions:

The explicative model presents a pathway for personal and professional growth, by accumulating strategies that modulate emotional responses and encourage an ongoing passion for work.

Keywords: Psychological, coping skills, coping strategies, emotional regulation, terminal care, palliative care, professional competence, health personnel, self-care, grounded theory, qualitative research

What is already known about the topic?

Palliative care professionals use coping strategies to deal with the emotional challenges of their work.

Coping skills are essential for professionals to stay and remain in palliative care.

What this paper adds?

A grounded theory of a five-phase transformative process through which palliative care professionals develop coping capacity and evolve from a phase of emotional contention toward one of care based on inner balance and a transcendent perspective.

Key factors influencing the development process are some clinical cases, teamwork, and selfcare.

The study shares how the sensations of feeling overwhelmed can sometimes be reversed as professionals come to understand how to care for themselves.

Implications for practice, theory, or policy

The model may help palliative care professionals to understand how they can develop their coping skills.

This study emphasizes the role of certain team mates from close teams as influential in developing coping skills.

Institutional support and recognition for the work of palliative care professionals is important in the coping process.

Introduction

Working in palliative care is rewarding,1,2 but poses challenges, including exposure to emotional distress and the demanding psychological and existential situations faced by patients and families. 3 This can lead to stress, 4 jeopardizing the well-being of health professionals. 5 The need for effective coping mechanisms thus arises, so that people can maintain a career in palliative care without incurring excessive personal and professional costs.

Coping refers to the cognitive and behavioral strategies developed to address internal and/or external demands.6,7 Lazarus and Folkman, 8 pioneers on coping, defined it and proposed a transactional model for coping, focusing on problem-solving and emotional responses. Coyne and DeLongis 9 expanded on this model emphasizing coping through interpersonal relationships and seeking support from one’s social circle. Park and Folkman 10 further developed the transactional coping model by incorporating coping based on overall meaning. These authors have shed light on where coping can be focused to deal with demands, and provide the basis to study coping.

In palliative care contexts, where there is exposure to emotional distress, death and dying, Vachon 11 identified stress factors that impact health professional coping. Coping mechanisms were categorized into personal and organizational strategies. A recent review 12 outlines various coping strategies, including proactive-coping, self-care-based coping, self-transforming coping, and encountering deep professional meaning. This review also highlights the dynamic nature of influencing factors, which can shift from having a protective role to becoming risk factors and vice versa, providing a more dynamic view of professional coping. However, despite the variety of coping strategies mentioned in the literature and the idea that coping is dynamic, little is known about how the coping capacity of palliative care professionals evolves.

As palliative care has become integrated into health systems, 13 the prevention of burnout and the promotion of long, fulfilling careers have gained importance. 14 Studies have focused on the potential fatigue resulting from working in palliative care,15–17 examining difficulties such as burn out, frustration, depression, and loss of professional meaning. These studies emphasize the importance of self-care and address the emotions experienced in clinical practice as a means to continue working in palliative care.18–20 Some research has explored specific coping strategies and their effects. 3

However, there is limited understanding of the evolution of professional coping itself. Coping may play a role in the process to becoming an expert in palliative care. 21 As with professional development itself,22,23 coping strategies might evolve in phases throughout someone’s career. Just as people with palliative care needs learn to cope, 24 professionals too may well undergo a parallel process throughout their careers.

Methods

Research question/aims

The research question was, how do palliative care specialists who take care of patients with advanced illness at the end of life cope with emotional and demanding situations through their career? Our aim is to gain a comprehensive understanding of their coping mechanisms in order to develop initiatives that promote and teach effective coping strategies. The findings will contribute to the knowledge base of palliative care professionals and the field as a whole, providing valuable insights for future strategies aimed at maintaining an emotionally healthy and resilient workforce capable of delivering high-quality patient care. 15

The specific objectives were to:

- Understand the process of coping with the emotional demands put on professionals when accompanying advanced patients and their families at the end-of-life.

- Identify coping strategies and resources used by these professionals.

- Identify the factors (individual, team-based, and external) which contribute, positively or negatively, to that coping process.

Design

To understand this process better, a grounded theory was conducted. 25 The project was based on the epistemological and ontological interpretivist philosophy of knowledge, being a product of multiple viewpoints, theories, and concept synthesis.

Participants

Participants were palliative care nurses and physicians. The inclusion criteria were: nurses and physicians with experience working in palliative care services in Portugal or Spain.

Setting

Palliative care services in Portugal and Spain, offering specialized medical care for people living with a serious illness, with a multidisciplinary team (i.e. palliative care nurse, palliative care physician, psychologist) to take care of the patient and family. We included palliative care services independently of the type of format (i.e. hospital support team and unit) located in different geographical areas of Portugal and Spain (n = 9).

Sampling

Purposive sampling was used seeking the greatest variability and considering different types of palliative care services (i.e. hospital palliative care support team, palliative care units, and home care palliative care) and also individual participants characteristics (i.e. years of experience, gender and marital status).

Recruitment

Palliative care services were informed about the study (i.e. emailing study information and organizing informative sessions at interdisciplinary service meetings) and it was explained that variability regarding participants’ characteristics was aimed for. Healthcare professionals with different characteristics were identified and invited to participate by email. They were sent the information sheet and informed consent.

During the investigation we perceived that some healthcare professionals had managed to develop their coping skills to continue working in palliative care, which led us to think that perhaps those who had moved to another specialty might add a different perspective about coping. Therefore, theoretical sampling was applied, adding professionals who had later moved on to another specialization (n = 4; their quotes are marked with *). In each country, researchers talked with palliative care professionals to identify colleagues who were no longer working in palliative care. Through these healthcare professionals, researchers obtained permission to contact the professionals who no longer worked in the field. Researchers contacted them and invited them to participate in the study.

The interviewers were academics and there was no prior relationship between interviewers and participants.

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted, with a pilot experience to test the interview guide with two palliative care professionals. Two researchers (PS and MA) who were fluent in the local language conducted the interviews face-to-face at agreed-upon locations. The interview guide covered the following topics: asking to the subjects to describe a case that had an emotional impact on them, what they did, what was helpful for them and afterwards questioning about whether they have always handled matters the same way (Supplemental Appendix 1). Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Two researchers completed a constant comparative analysis, 25 until data saturation was obtained. Theory was described by codifying the transcriptions with constant comparison both within each transcription and between transcriptions. Line-by-line, open coding was performed on each interview transcript. Similar codes were reassembled into categories and their properties were identified. There was further refinement of categories, were subcategories raised to a higher level of abstraction and possible interrelations were considered (axial coding). Relationships between categories that begin to explain what was going on were identified (selective coding). Regular meetings were held among the coders throughout the analysis process. When alternative codes and categories were proposed, consensus was reached through repeated data examination. NVivo12® was used for data processing.

The theory developed was presented in sessions and seminars with palliative care professionals from both countries, including some participants from the sample. The attendees concurred that the findings resonated with their experience and they could relate them to their own careers and those of their clinical colleagues in different “stages” of the process.

Ethical issues

Ethical approval was obtained from the Comité de Ética de la Investigación de la Universidad de Navarra (ID: 2019.167). Participants received information about the study and provided written consent. All names are fictional, in order to protect participants.

Results

Participant characteristics

Twenty-one palliative care professionals (Table 1), from Portugal and Spain, participated. The mean duration of interviews was 41.5 min (range from 20 to 99 min)

Table 1.

Participant profiles.

| Characteristics | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 16 (76%) |

| Male | 5 (24%) | |

| Family Situation | Married | 19 (90.5%) |

| Single | 2 (9.5%) | |

| Parents | 19 (90.5%) | |

| Religion | Catholic | 19 (90%) |

| Non-practicing | 7 (37%) | |

| Jewish | 1 (5%) | |

| Agnostic | 1 (5%) | |

| Profession | Physician | 9 (43%) |

| Nurse | 12 (57%) | |

| Country | PT | 14 (67%) |

| SP | 7 (33%) | |

| PC training | Postgraduate | 18 (85%) |

| Ongoing | 3 (15%) | |

| M | Range | |

| Age | 46.8 | 37–63 |

| Years in the profession (average) | 24.3 | 12–44 |

| Years in palliative care (average) | 14.2 | 4–27 |

PT: Portugal; SP: Spain.

N total: 21.

Results

Palliative care professionals acknowledge the emotional burden associated with their work, which they generally handle well. Nevertheless, they also encounter specific situations which require additional emotional effort (Table 2) and which are specific to each participant.

Table 2.

Trigger cases-specific situations which require greater emotional implication.

| Situations | Professional lived experiences |

|---|---|

| They see themselves reflected personally in the clinical situation | Identification due to similar characteristics, leading to more intense emotional involvement: age, family situation; children of the same age. |

| Complex family situation (i.e. violence) | These suppose greater challenges which are not always well managed. |

| Ethical dilemmas | Represent a personal and professional dilemma, above all when part of a team, or working with other teams. |

| Children and young people | Experienced as contrary to the “natural life cycle”; creating further distress, generating suffering, everyday challenges, and emotional landmarks professionally |

| The elderly or psychiatric patients | Patients in situations of greater vulnerability cause feelings of greater compassion. |

| Patients alone | |

| Late referral patients | Situations which cause greater distress for the professional because they do not allow for adequate intervention; they highlight misunderstandings which exist in palliative care, lack of understanding of its philosophy or resistance to its implementation. |

| Patients without records | |

| Patients in denial | |

| Lack of support from superiors or organization | Temporary feelings of “I can’t go on”; ongoing feelings that their work is not appreciated; institutional demotivation/disappointment; risk of alienation; resulting decisions to cease to work in palliative care |

| Patients or relatives who are examples of strength, resilience, or stoicism | Understood as lessons in life: showing how to face up to suffering |

In response to the regular emotional burden and challenging situations, professionals undergo a transformative process fuelled by their passion for the work (central concept process, Table 3), revolving around caring for the patient and family. This starts from the early stages of their palliative care career. Over time, they encounter special situations that emphasize the importance of teamwork and self-care in developing effective coping strategies. These are acquired through experience and help reshape their responses.

Table 3.

Stages and key aspects in the transformative coping process.

| Stages | Trigger cases | Teamwork | “Selfcare” | Passion for their work |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commencing in palliative care | Everything is new and this generates many negative feelings and stress because they want to manage the clinical situation/symptoms. If the professional has clinical experience in another field, trigger cases are those where they feel unsure (e.g. talking to the family or very complex family situations) |

They identify with the existence of palliative care team, with a common care philosophy. The initial stage involved observation and learning. | They identify that their work generates emotions (recognize that their work has an emotional “plus”) | Dreams and an idealistic vision of palliative care (of everything they can do for the patient/family). |

| Recognizing your own vulnerability | They realize that some clinical situations are especially striking experiences which trigger negative emotions. | They begin to ask themselves how colleagues manage the emotional challenges. Begin to share and reflect with certain workmates. |

They identify the need to disconnect from their work, to try and free themselves from negative emotions, and to set a distance between them and their work by spending time with family and friends (spending time outdoors, going shopping and doing sport) | They like their work but realize the importance of managing the related emotional challenges. |

| Proactively managing emotions and seeking inner peace | They undertake progressive learning, with complex cases (the learning motor) They feel the need to manage the emotional burden of their work in a different way. They perceive specific moments in which they feel that they cannot go on (due to clinical cases or because of team or systemic dynamics). They know how to interpret the variable intensity of cases. |

They seek security and support in the “micro-teams of strength” which are created due to internal rapport within the team. Sharing and reflecting with other experts, including those from other teams. |

They query how to better manage and to adopt a more proactive attitude in emotional management. Proactively promote activities to focus on other things. Commence selfcare, look for training and more formal strategies. The need arises for more inner reflection. |

There is a significant evolution in what they suppose is their work. |

| Cultivating an Integrative approach to care | They place more importance or relevance on the most humanistic part of care and of their work. They ask themselves “What?”, “What for?”, “Why do this job?”? (For example, they mention emotionally demanding cases, some positive, and others negative). | Openly share emotions and reflection in teams. Reciprocal help and care in the team. |

They gradually learn to close cases better. Use more techniques for introspection and relaxation. Learn lessons from the lives of patients and their families and begin to know themselves better. |

They work, interiorizing the philosophy of palliative care and that brings security and a more complete, encompassing view of reality. They learn, with a more open approach, considering other dimensions of life (beyond the biomedical aspects). |

| Grounding yourself and accepting your own limitations | There is a balance between challenges and their contribution to their work, accepting limits to the same. They have a wider understanding of the world and of life. They feel personal growth and look deeper into the meaning of life. Care focusses on the sick person and their family and on the overall suffering within a realistic application framework. Naturally compassionate with themselves and with others. | They act as an instrument to help others. Share and reflect with others to construct a joint model for care. They promote teamwork and their members’ development; receive and give help to colleagues; there is reciprocity and good rapport. |

They accept the commitment to self-care and have integrated self-care activities learned beforehand. Interiorization of limits, as basis for work. Develop the capacity to stay with and for the patient, from an alternative position of acceptance of their own vulnerability and complete disposition. |

Work in palliative care is part of their life and something which makes them feel whole, they feel good about their work and the emotional effort is within their limits. They feel that their work has made them into better people. They highlight the privilege of spending time with patients, their experience and the comfort which comes from the results of their labor. The spotlight is on the sick person; they worry about overall suffering and act thus. |

Within this coping process, five successive stages can be identified (although some can be revisited; Figure 1): (a) Commencing in palliative care; (b) Recognizing one’s own vulnerability; (c) Proactively managing emotions and the search for inner peace; (d) Cultivating an integrative approach to care; and (e) Grounding through introspection and understanding one’s own limitations. From a significant word from each phase, we chose a letter to form the acronym COPING. to remind us of this process.

Figure 1.

Explicative model for professional coping in palliative care professionals.

Commencing in palliative care (Commencing)

At this stage, palliative care professionals are drawn to the positive aspects of the philosophy, recognizing its qualities and benefits. While they may be aware of the emotional effort required to care for patients and families, they may not fully comprehend its true extent. Many professionals express this.

“I think there was so much hope, that you did what you could” (Antonio)

Despite their enthusiasm, professionals also experience uncertainty. The lack of knowledge about the field and specific considerations, such as the importance of caring for family, creates problems and negative emotions.

“When I first came here, I saw how much the family were looked after and I said, “well, I am not sure about the family. I don’t how I’ll manage”. I had been working with this kind of patient for years, but I was not used to working so intensely and so deeply, as part of the team, with the family” (Lourdes)

Despite these challenges, professionals perceive a united team sharing a common philosophy of care, which they value positively. This allows them to learn by observing their colleagues’ actions. However, they often try to repress their emotions in order to avoid showing any signs of weakness or skill deficiencies.

“I tried to keep it myself because I felt less of a professional, because I was sad at times. I have to confess that I would go home and cry (. . .) before, I held it all in and if something bothered me, I kept quiet, but not now. . .” (Fátima)

Coping strategies typical at this stage

The professional focuses on emotional contention and “doing,” aiming to resolve the patient’s issues. There is a strong emphasis on the biomedical approach, where the application of techniques and treatment of symptoms is prioritized.

“At the beginning it was more difficult, because I was very much into the biomedical part, even in the area of palliative care, until I managed to distance myself from that model and understand that there are specifics for each symptom and for each person. . .” (Francisco)

Recognizing one’s own vulnerability (Own)

At this stage, the professional realizes that certain work situations can trigger negative emotions of great intensity. These emotions may arise from particularly challenging cases or accumulative difficult cases. The specific cases that affect professionals may vary (Table 2), but everybody agrees that these evoke negative feelings (sadness, anger, and impotence), making them emotionally vulnerable and causing suffering.

“13 years ago, I had more energy, an energy level which felt endless, but the truth was quite different and to the extent that things accumulated, I experienced exhaustion, which occurred periodically, understanding how to live in that state of tension. . .” (Antonio)

Professionals recognize the difficulties and embark on a process of self-reflection: How do I approach this? How do I solve this? What should I do about this?

“I wasn’t at peace, I would get home and go over the day, remembering, from a different perspective to see if I had done the best thing or not. . .what I could have done differently” (Carolina)

Coping strategies at this stage

Professionals become aware of the need to address their emotions and engage in deeper introspection. They identify the need to disconnect from work and the negative emotions experienced. They actively seek ways to free themselves, stepping back and spending time with friends and family (outdoors, shopping, and doing sport), which are usually positive factors.

“I began to realize that there was no way I could take this home with me (. . .) trying to invent strategies with things I like doing, seeing a good movie, reading a book which really held my attention and didn’t make me think too much (. . .). That helped me. Meditation also helped me a lot” (Margarida)

“But sometimes I just need to be alone in the room, meditating about my things, I need it” (João*)

Professionals may return to this stage during their career, adding coping strategies which help to lessen the intensity of their feelings of vulnerability.

Proactively managing emotions and seeking inner peace (Proactively)

Professionals adopt a different approach to maintaining their emotions, aiming to continue their work with a reduced emotional cost and seeking the security needed to go on. They become more adept at interpreting the changing intensity of emotions triggered by cases and strive to control their responses. Difficult cases, team dynamics, and the complexities of the healthcare system can lead to moments where professionals feel overwhelmed and in need of a pause (Table 2). This prompts them to adopt a proactive and reflective attitude toward emotional management.

“I am conscious of my limits, my intervention there is to help the patient manage symptoms, to live with the disease, or at end-of-life or in a particular situation. . .having the notion of my limits and what I can and what I can’t control” (Virginia)

“there are some things which are my responsibility and others are not. And sometimes, you have to face up to it and other times, I won’t have to” (Pedro*)

Coping strategies at this stage

Professionals are more proactive and open to exploring different strategies. They find value in reflecting on their experiences and sharing them with senior colleagues, which facilitates progressive learning.

“I also try to put some closure on what I have been through, at the end of the day, thinking about what I have learned today, or about how nice or how bad something I saw was, how tired I am, why it drained my energy. Something wore me out today, so let’s see what I can do tomorrow to make it less exhausting” (Eva)

Many participants mention seeking training, both related (e.g. advanced training in palliative) and unrelated to their work (e.g. religious or spiritual education, philosophy, healing, and mechanisms to help identify their emotions), as a means of self-learning. Training is unanimously considered a positive factor. Engaging in activities that provide distraction and enjoyment becomes more prevalent, with some finding solace in family life, which is considered a positive factor as long as it is balanced.

“I love walking and there is a place that I like, near the sea (. . .) and that soothes the soul” (Dulce)

“Having a happy, active, dynamic family life is very important (. . .) I think it’s the family who help me most” (Alice)

Professionals recognize their own vulnerability and find support in “micro-teams of strength,” workmates with affinity who share their experiences together. They do not seek out formal support strategies.

“We had other formal strategies, where we met once a month and discussed topics we wished to face as a team (. . .) but they stopped (. . .)the structure and changes which took place and the lack of professional resources. . .that’s why we lost some of these possibilities” (Arminda)

“There are informal conversation strategies among us, to let off steam, but they are very personal and very spontaneous, on a particular day. . .we have a very strong relationship and are close enough to be able to share some emotions, but it’s very informal, with more restricted groups . . .” (Carolina)

Even with the support of colleagues, for these healthcare professionals, acknowledgment and assistance on the part of superiors are considered crucial. Support and recognition of palliative care by managers and the institution are essential because trying to provide palliative care in a framework that does not understand or value it entails additional wear and tear.

“The managers of palliative care services suffer the effects of blissful ignorance on the part of center general managers, as they don’t really understand the work in palliative care (. . .) the guidelines are there for them to read, but obstacles and resistance still exist (by management) (. . .) Bit by bit, we are learning to engage more with health service management, but we need to learn those management skills too” (Antoine)

“But not having a long-term view of the organization and feeling badly treated. . .and undervalued. . .no way!” (João*)

The professional remains actively engaged “doing,” but adopts a wider perspective of patient and family needs, and reflects on the whole context. This stage is a pivotal moment in the evolution of professional coping.

“As you start to feel more secure about what you are doing, what changes? The spotlight was taken off me! The spotlight started to fall on people (. . .) on that person’s needs, what is important for them at that moment” (Inés)

Cultivating an integrative approach to care (INtegrative)

Professionals have interiorized the philosophy of palliative care, which provides security and a wider vision of reality. Professionals prioritize the most humanistic aspect of their work, recognizing emotionally intense situations, both positive and negative (Table 3). Questions arise in their work as to what, why, and what for.

“I think that now, I work much better, exclusively in palliative care (. . .) before I suffered a lot more (. . .) I feel that patients, in terms of symptoms, of psychological support and of social support, are better managed. That’s to say, this is what is needed at this stage, where they find themselves and that releases us from a lot of suffering which we had previously” (Alice)

“You are going to suffer more on those days, but be systematic, focus on the principles of what we do. What are we looking for? The welfare of the patient and their families? Well, now you know where to go!” (Pedro*)

They understand the importance of a more comprehensive approach to meeting the needs of patients and relatives. They recognize the relevance of the patient’s own perspective and embrace a wider vision that goes beyond the traditional biomedical approach.

“Being here is getting involved in other things, asking other questions, seeing what is really important for that person, not for me, because to start off with, for me it might have been something else (. . .), and coming to realize that in reality, that is not what is important them (. . .) Understand things which happen to people, learn not to judge, especially not to judge, but to understand, and let our interventions become flexible” (Josefina)

Coping strategies at this stage

Professionals develop various approaches to modulate their response. They also normalize their own limits and cultivate self-compassion, acknowledging that they cannot meet all the needs of the patient and their family. This helps them align their expectations with reality and avoid negative emotions.

At the same time, they learn to close cases better and intentionally share their emotions with the team, as a way of helping others to also recognize their own emotions. There is reciprocity in help and in care within the team.

“We, the most experienced ones, pay attention to junior colleagues, who feel comfortable coming to let off steam with us and we manage to get this work done together, as a team” (Carolina)

They also go deeper into the humanistic dimension, prioritizing the needs of the individuals they care for. They strive to focus on what the patient and their family truly want, not on what they themselves think or see. This implies introspection, utilizing relaxation techniques to better address the patient’ and their relatives’ needs, while placing themselves in the background. They draw lessons from the lives of patients and their relatives, becoming more adept at recognizing and organizing their own inner selves.

“Knowing that there are no absolute truths, that there is no predetermined way of getting on with everyone, that each person is unique. (. . .) From patients, I learn a lot from the elderly and what they know; to the point of not knowing what I would do, in their place” (Alexandra)

Grounding yourself and accepting your own limitations (Grounding)

At this stage, professionals feel that working in palliative care is part of their life and fulfills them. They have developed effective strategies to manage the emotional demands of their work, leading to a sense of happiness and fulfilment. They recognize the personal and professional growth that their work has brought them.

“So, I identify with palliative care. I believe I am part of palliative care. . . .I think I do. . . I like giving palliative care, wherever I am sent” (Raquel*)

“Working in this area changes a person a lot. I ended up gaining more than we sometimes give. We grow so much; we grow as people, a greater capacity to understand others, to understand ourselves, to appreciate the greatness of life, but we also learn the value of it” (Dulce)

Most professionals recognize the need for personal wellbeing and balance in order to work effectively in palliative care. A lack of personal balance can negatively impact their ability to continue in this field.

“It destroyed me as a person, being unable to adapt my timetable to my daughters’ care, due to the lack of support from my boss. As I believe one of the fundamental things is to manage to maintain balance between our professional and personal lifestyles. That’s to say, if our professional life affects our personal life to a great degree, this is undoubtedly an imbalance” (Dilma*)

Some professionals may temporarily or permanently stop working in palliative care if feelings of fatigue or lack of balance persist over time.

“But it started to last longer, and I wasn’t able to rest on a personal level (complex family situation). I didn’t recover the strength I thought I should have. So, I went through a period just keeping up, dragging myself bit by bit, carrying that fatigue, the fatigue and I couldn’t keep up, just couldn’t recover. And so, I had to stop” (Raquel*)

Professionals feel confident in their abilities and willingly delegate cases to others if they feel the patient will receive the necessary care from the colleague to whom they delegate. The patient and their family become the primary focus, and professionals recognize the importance of complementing each other within the team to meet their needs.

“Informally and at the same time, formally, work gets done well as part of a team, there’s lots of mutual help, there’s space to share and people are available when needed by someone else” (Virginia)

Professionals experience a balance between the challenges they face and their contribution to their work. They accept their limitations and embrace the overall purpose of palliative care, understanding the need for realistic actions and an understanding of suffering.

“We can put into practice this truly practical therapeutic help and responding to others’ needs also helps us. It’s as if compassion for others recharges our batteries as people too. That is to say, feeling that I am doing my own work well means I don’t suffer” (Alice)

Professionals continue to grow personally, they deepen their understanding of the meaning of life. They become naturally compassionate toward themselves and others, fostering meaningful connections.

“My experience has been that I widened my horizons or my mind, my vision of life, of people (. . .) That helps keep you together and you start looking, finding meaning and you start seeing. . .so in the end, the important thing is not what you do, but being there and that is as important as doing: It is what people thank you for at the end, above all; your commitment, being there and providing company” (Josefina)

Coping strategies at this stage

During this stage, professionals commit to self-care and have integrated various coping strategies into their routine. They recognize the importance of taking time for themselves and engaging in activities such as going for walks, reflecting on their experiences and nurturing their physical-wellbeing.

“At times, I feel the need to go for a walk and I have the need to be alone and to reflect, to put things in their place. . . I like to have periods of introspection where I analyze the impact that a situation had on me, what I could have done better” (Dilma*)

“I also got used to looking after myself physically a little (. . .) it is fundamental to set time aside for ourselves, our self-knowledge and our capacity for giving of ourselves to others” (Margarida)

They interiorize their limits and approach their work with acceptance of their own vulnerability and a commitment to being present for the patient and their family.

“Take a walk, get some fresh air before going back to see another patient” (Fátima)

“Yes, you normalize it, become aware of saying “well, it’s not that bad”. Then, it is like accepting that each time you go into a room, you might become emotional, or surprise yourself. So, it’s not that bad” (Lourdes)

Professionals focus on personalized care and respect the boundaries set by patient and families. Expressions of gratitude received from patients and the privilege of accompanying them provide comfort. They actively share and reflect with others, fostering a way of caring, which is a positive factor.

“Whilst the same message is transmitted, whilst we all have the same attitude in our support, we all trust each other a little and we transmit this confidence, which I think is the best, the basics. Moreover, we have similar attitudes and make similar decisions” (Josefina)

Seasoned professionals prioritize the promotion of teamwork and the development of teammates. They actively help others, including patients, families, and even non-palliative care professionals, accepting that not everybody has the same training.

“I have always said that the patient before us is where we have to act immediately, but the greatest investment, medium to long term that we can make, is in training, and in that sense, I have done enough personally and I think that is also good, as one has a mission that way” (Antoine)

“You learn to say, “That’s true, the GP and their team are doing their bit, doing things differently from what you would do, but they are doing their bit.” The oncologist is there too and the hematologist, however difficult. . . I can see that they have not come this far to start delegating or think that there are others who are present too and who can do it and we can share. It annoys me when there is no possibility of convincing them to say, “Let’s try, let’s see,” Well, maybe not, maybe sometime in the future” (Josefina)

The learning process for professional coping allows them to revisit earlier stages and strategies, enabling them to progress further. While temporary feelings of “I can’t go on” may arise, they are often reversible. However, for some professionals, these feelings persist, leading to reflection and the decision to temporarily or permanently leave palliative care services. Common reasons for leaving include a sense of losing meaning, depersonalization, and a lack of institutional support, recognition, and difficulties in self-care; but not the relationship with patients and families. Professionals acknowledge the applicability of the palliative care philosophy to other areas. They refer to this as “Palliative care baggage” to capture what they learned about caring for the whole person during their career in palliative care and describe it as something that is part of them as professionals, entailing a way of caring for patients and families. They affirm their commitment to this way of caring wherever they go. The complex reality surrounding professionals’ decisions to leave palliative care goes beyond the scope of this study and requires further research. Understanding the causes, and how professionals manage this process, is essential to better support their well-being and retention in the field.

Discussion

Main findings

Our theory contributes to understanding the development of coping capacity throughout a professional career in palliative care. This process involves the transformation of both professional and personal aspects, leading to the development of diverse strategies and resources that allow professionals to better modulate their responses while accompanying patients with serious illnesses and their families. The explicative model has five stages: Commencing, Recognizing own vulnerability, Proactively managing emotions, Cultivating an integrative approach to care; Grounding. These stages are characterized by the evolution of teamwork, selfcare, and passion for their work. Stages can be revisited, but once the turning point at stage “Proactively managing emotions and seeking inner peace” is reached, professionals do not revisit previous phases.

What this study adds?

As suggested in a recent systematic review 12 in which different studies focus on coping with death and dying26,27 or on the effects of coping,28,29 professional coping is dynamic and evolves with clinical experience, requiring a more integrated approach to explore it. Our study adds an explicative model about the dynamic nature of the coping process of palliative care professionals. It provides a comprehensive explanation of the coping process within the context of a professional career, building upon earlier research. While not directly discussing the coping process, the process of achieving professional maturity and becoming an expert in palliative care described by Mota et al. 21 aligns with the current results. In the process of becoming a mature palliative care expert learning to cope plays an integral part. Each professional has their own pace and development timing, with some requiring more time than others. Nevertheless, all professionals revisit certain stages of the coping process to progress.

The process commences with intentional action and emotional contention. Professionals anticipate emotionally demanding clinical situations inherent to palliative care2,11 and primarily employ problem-solving coping strategies within a team context. They tend to keep their emotions to themselves, perceiving an external display of emotions as unprofessional. This suggests a perception of a lack of organizational legitimacy30,31 for it. There is no frustration, 21 but professionals start recognizing their own vulnerability, reflecting on how to manage it. The most intense clinical situations resemble those previously mentioned, 15 with the exception of “ethical dilemmas.”

The subsequent stage involves recognizing one’s own vulnerability. Professionals acknowledge their sensitivity to the suffering of patients and their relatives and understand the importance of emotional labor 32 in developing coping skills, both in palliative care, 33 and other clinical contexts. 34 Emotion-focused coping strategies complement problem-solving 8 approaches. Professionals employ various strategies (i.e. disconnect by going for a walk and spending time with friends),35,36 and identify those situations which are especially demanding. Heightened self-awareness becomes crucial in situations of suffering, palliative care, 3 resilience development, and selfcare.3,37

As professionals identify different degrees of emotional demand on themselves, they proactively seek ways to manage them. They engage in introspection to channel their experiences and prioritize self-care as a means of maintaining stability.3,18 Strategies are added to their repertoire, 29 such as speaking to veteran colleagues and creating support networks with other professionals.

Teamwork, another key to patient and family care,31,38 becomes significant in coping strategies. “Micro-teams of strength” are created for mutual support, although the importance of superiors in dealing with “extra” emotional challenges arising from organizational or institutional issues is also recognized. The study highlights the relevance of “work environment stressors,”11,39 as these often contribute to professionals changing their working environment. This aspect requires further study, particularly regarding the importance of healthy work environments and the availability of institutional resources.39,40 The study suggests that there is currently insufficient support, as professionals mentioned the lack of formal support due to inadequate institutional backing. Institutional commitment and a caring culture that supports palliative care professionals are necessary. 34 Professional training is considered a protective factor,29,40 and professionals seek further training in complementary areas.

Professionals’ development involves accepting both internal and external limiting factors, including those of the patients. They recognize the need for sensitivity without excessive suffering, drawing on the concept of the “wounded healer.” 18 This requires a high degree of self-awareness which suggests continuity in their development. Self-care 41 and setting clear professional boundaries 43 play vital roles. Introspection is mentioned as a means to prevent stagnation and maintain passion for one’s work. This may explain the relationship between specific aspects of the professionals’ inner lives 3 and their perceived need to promote professional quality of life. 42 Self-care is a key to working in palliative care.3,42 The study explains how these professionals perform this in the successive stages of coping during their professional career.

The cultivation of an integrative approach to care follows, emphasizing the humanistic aspect of palliative care and the holistic needs of patient and their families. Emotional work is legitimized, and professionals openly share experiences, coping strategies, and self-care with their team members. They share learning thanks to the ongoing inner work of learning from patients, for better or for worse, 22 and they close cases better. Learning to regulate the degree of involvement at work is fundamental in care. 15

Grounding oneself and accepting personal limits is the next stage, where professionals connect closely with their inner selves and use this resource to assist patients, families, and colleagues. Acceptance of vulnerability and dedication 3 are crucial, aligning with self-care strategies related to the generation of “healing connections” 43 and the concept of “Whole Person Self-Care.” 2 This suggests that self-care should be whole, from the interior to the exterior, highlighting the need to be connected and not only seek the initial disconnection. This harmony between the inner-self and work generates satisfaction and allows professionals to thrive. Just as the disconnection between professionals themselves and their work can lead to burnout, that same harmony can lead to joy and to flourishing. 41 These are strategies based on meaning. 10 Palliative care takes on a transcendent meaning, and professionals feel privileged to accompany patients, creating a common legacy of care. Emotional aspects are legitimized and valued, creating an environment of identification and acknowledgment. Emotional discussion extends micro-teams, fostering emotional-level discussion between professionals. New “feeling rules” are fostered, underpinning the guidelines or moral stance which affect actions and which are implicit in others’ responses and in prevailing social conventions. This new coping strategy acknowledges a “sentimental order,” defined as a “real, but intangible pattern of the state of mind and the feelings which characterize each service” 44 (p. 14), which recognizes and legitimizes emotional work in the workplace. It challenges the prevailing perspective of suppressing emotions in the context of healthcare. Veteran professionals play an active role in promoting their colleagues’ abilities in this regard. The study highlights the personal and professional development experienced by professionals who have worked in palliative care, even if they no longer continue in that specific field. We are not aware of other published analyses of this aspect.

Strengths and limitations

We complied with the grounded theory rules. Using these, a model of coping capacity development among palliative care nurses and physicians could be presented in an integrated and structured way. Views of professionals from two different countries and complemented by insights from those who had not continued working in the area were included. However, although we tried to provide a comprehensive description of palliative care professionals’ coping capacity evolution, there are some limitations. The study included physicians and nursing staff, but other team members may employ different coping strategies. We did not specifically include paediatric palliative care professionals. Therefore, some nuances of coping strategies when working with children might have been overlooked.

Implications for practice, education, and research

Understanding the coping process is crucial for palliative care professionals to prevent emotional exhaustion and enhance self-care. Teamwork plays a vital role in fostering coping skills and reducing professional fatigue. Training at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels should incorporate this knowledge to equip professionals with effective strategies. Additionally, promoting a culture of care at institutional level and investigating the reasons behind palliative care professionals leaving the field would provide valuable insights into motivation and management.

Conclusion

This study explains the process of professional coping in palliative care among physicians and nurses from two countries. It identifies a journey of personal and professional growth encompassing five stages, with the core concept being the development of passion for their work. Through experience and learning, professionals acquire coping strategies to modulate their emotional responses. Training in coping strategies enables professionals to achieve inner harmony, balance and transcendence. Collaboration within a team and self-care are essential throughout the process, alongside the need for an institutional culture that provides support. Senior team members play a significant role in caring for others, recognizing, and preserving their palliative legacy for the team’s collective benefit.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-pmj-10.1177_02692163241229961 for How palliative care professionals develop coping competence through their career: A grounded theory by Maria Arantzamendi, Paula Sapeta, Alazne Belar and Carlos Centeno in Palliative Medicine

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge and thank all the professionals who participated in the study and without whom it would not have been possible to carry it out.

Footnotes

Author contributions: All authors contributed significantly to the paper and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Data management and sharing: Not applicable. The data collected in this research are full interviews with healthcare professionals. As such, data cannot be shared as it would violate participant confidentiality.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Research ethics and patient consent: Approval to conduct the study was granted by the Comité de Ética de la Investigación de la Universidad de Navarra (ID: 2019.167). This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants received information about the study and provided written consent.

ORCID iDs: Maria Arantzamendi  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2406-0668

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2406-0668

Paula Sapeta  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6667-2326

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6667-2326

Alazne Belar  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4831-5218

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4831-5218

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Sinclair S. Impact of death and dying on the personal lives and practices of palliative and hospice care professionals. CMAJ 2011; 183: 180–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tan SB, Lee YL, Tan SN, et al. The experiences of well-being of palliative care providers in malaysia: a thematic analysis. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2020; 22: 407–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sansó N, Galiana L, Oliver A, et al. Palliative care professionals’ inner life: exploring the relationships among awareness, self-care, and compassion satisfaction and fatigue, burnout, and coping with death. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015; 50: 200–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sansó NM. Afrontamiento ante la muerte en profesionales de cuidados paliativos: variables moduladoras y consecuentes. PhD Thesis, Universitat de les illes Balears, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zanatta F, Maffoni M, Giardini A. Resilience in palliative healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 2020; 28: 971–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Dunkel-Schetter C, et al. Dynamics of a stressful encounter: cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986; 50: 992–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dias EN, Pais-Ribeiro JL. O modelo de coping de Folkman e Lazarus: aspectos históricos e conceituais. Rev Psicol Saúde 2019; 11: 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress appraisal and coping. New York: Springer, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Coyne JC, DeLongis A. Going beyond social support: the role of social relationships in adaptation. J Consult Clin Psychol 1986; 54: 454–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Park C, Folkman S. Meaning in the context of stress and coping. Rev Gen Psychol 1997; 1: 115–144. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vachon ML. Staff stress in hospice/palliative care: a review. Palliat Med 1995; 9: 91–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sapeta P, Centeno C, Belar A, et al. Adaptation and continuous learning: integrative review of coping strategies of palliative care professionals. Palliat Med 2022; 36: 15–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Davies E, Higginson IJ. Palliative care: the solid facts. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/107561 (2004, accessed 21 April 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 14. Swetz KM, Harrington SE, Matsuyama RK, et al. Strategies for avoiding burnout in hospice and palliative medicine: peer advice for physicians on achieving longevity and fulfillment. J Palliat Med 2009; 12: 773–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Meier DE, Back AL, Morrison RS. The inner life of physicians and care of the seriously ill. JAMA 2001; 286: 3007–3014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Koh MYH, Gallardo MD, Khoo HS, et al. Burnout in palliative care – difficult cases: qualitative study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. Epub ahead of print 24 March 2022. DOI: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2021-003347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang C, Grassau P, Lawlor PG, et al. Burnout and resilience among Canadian palliative care physicians. BMC Palliat Care 2020; 19: 169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kearney MK, Weininger RB, Vachon ML, et al. Self-care of physicians caring for patients at the end of life: “being connected. . . a key to my survival”. JAMA 2009; 301: 1155–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Benito E, Arranz P, Cancio H. Herramientas para el autocuidado del profesional que atiende a personas que sufren. FMC 2011; 18: 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Horn DJ, Johnston CB. Burnout and Self Care for Palliative Care Practitioners. Med Clin North Am 2020; 104: 561–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mota Vargas R, Mahtani-Chugani V, Solano Pallero M, et al. The transformation process for palliative care professionals: the metamorphosis, a qualitative research study. Palliat Med 2016; 30: 161–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Webster J, Kristjanson LJ. Long-term palliative care workers: more than a story of endurance. J Palliat Med 2002; 5: 865–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koh MYH, Hum AYM, Khoo HS, et al. Burnout and resilience after a decade in palliative care: what survivors have to teach us. A qualitative study of palliative care clinicians with more than 10 years of experience. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020; 59: 105–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Greer JA, Applebaum AJ, Jacobsen JC, et al. Understanding and addressing the role of coping in palliative care for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2020; 38: 915–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: strategies for qualitative research. London: Aldine Transaction, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Peterson J, Johnson M, Halvorsen B, et al. Where do nurses go for help? A qualitative study of coping with death and dying. Int J Palliat Nurs 2010; 16: 432, 434–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Huang CC, Chen JY, Chiang HH. The transformation process in nurses caring for dying patients. J Nurs Res 2016; 24: 109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Koh MY, Chong PH, Neo PS, et al. Burnout, psychological morbidity and use of coping mechanisms among palliative care practitioners: a multi-centre cross-sectional study. Palliat Med 2015; 29: 633–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dijxhoorn AQ, Brom L, van der Linden YM, et al. Healthcare professionals’ work-related stress in palliative care: a cross-sectional survey. J Pain Symptom Manage 2021; 62: e38–e34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Booyens SW. Organizational structure, culture, and climate. In: Booyens SW. (ed.) Dimensions of nursing management. Republic of South Africa: Creda Press, 1993, pp.185–217. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ruef M, Scott R. A multidimensional model of organizational legitimacy: hospital survival in changing institutional environments. Adm Sci Q 1998; 43: 877–904. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bolton SC, Boyd C. Trolley dolly or skilled emotion manager? Work Employ Soc 2003; 17: 289–308. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brighton LJ, Selman LE, Bristowe K, et al. Emotional labour in palliative and end-of-life care communication: a qualitative study with generalist palliative care providers. Patient Educ Couns 2019; 102: 494–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Funk LM, Peters S, Roger KS. Caring about dying persons and their families: interpretation, practice and emotional labour. Health Soc Care Community 2018; 26: 519–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kulbe J. Stressors and coping measures of hospice nurses. Home Healthc Nurse 2001; 19: 707–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ekedahla M, Wengströmb Y. Nurses in cancer care-coping strategies when encountering existential issues. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2006; 10: 128–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shimoinaba K, O’Connor M, Lee S, et al. Nurses’ resilience and nurturance of the self. Int J Palliat Nurs 2015; 21: 504–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gómez-Batiste X, Connor S. Building integrated palliative care programs and services. WHO Collaborating Centre Public Health Palliative Care Programmes and Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance. https://www.iccp-portal.org/resources/building-integrated-palliative-care-programs-and-services (2017, accessed 21 April 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vachon MLS. Caring for the caregiver in oncology and palliative care. Semin Oncol Nurs 1998; 14: 152–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pais NJ, Costeira CR, Silva AM, et al. Efetividade de um programa de formação na gestão emocional dos enfermeiros perante a morte do doente. Rev Enferm Ref 2020; 5: e20023. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kearney M, Weininger R. Whole person self-care: self-care from the inside out. In: Hutchinson TA. (ed.) Whole person care: a new paradigm for the 21st century. New York: Springer, 2011, pp.109–125. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Oliver A, Galiana L, Simone G, et al. Palliative care professionals’ inner lives: cross-cultural application of the awareness model of self-care. Healthcare 2021; 9: 81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mount BM, Boston PH, Cohen RS. Healing connections: on moving from suffering to a sense of well-being. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007; 33: 372–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Glaser B, Strauss A. Time for dying. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company, 1968, p.14. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-pmj-10.1177_02692163241229961 for How palliative care professionals develop coping competence through their career: A grounded theory by Maria Arantzamendi, Paula Sapeta, Alazne Belar and Carlos Centeno in Palliative Medicine