Abstract

DeepMind’s AlphaFold recently demonstrated the potential of deep learning for protein structure prediction. DeepFragLib, a new protein-specific fragment library built using deep neural networks, may have advanced the field to the next stage.

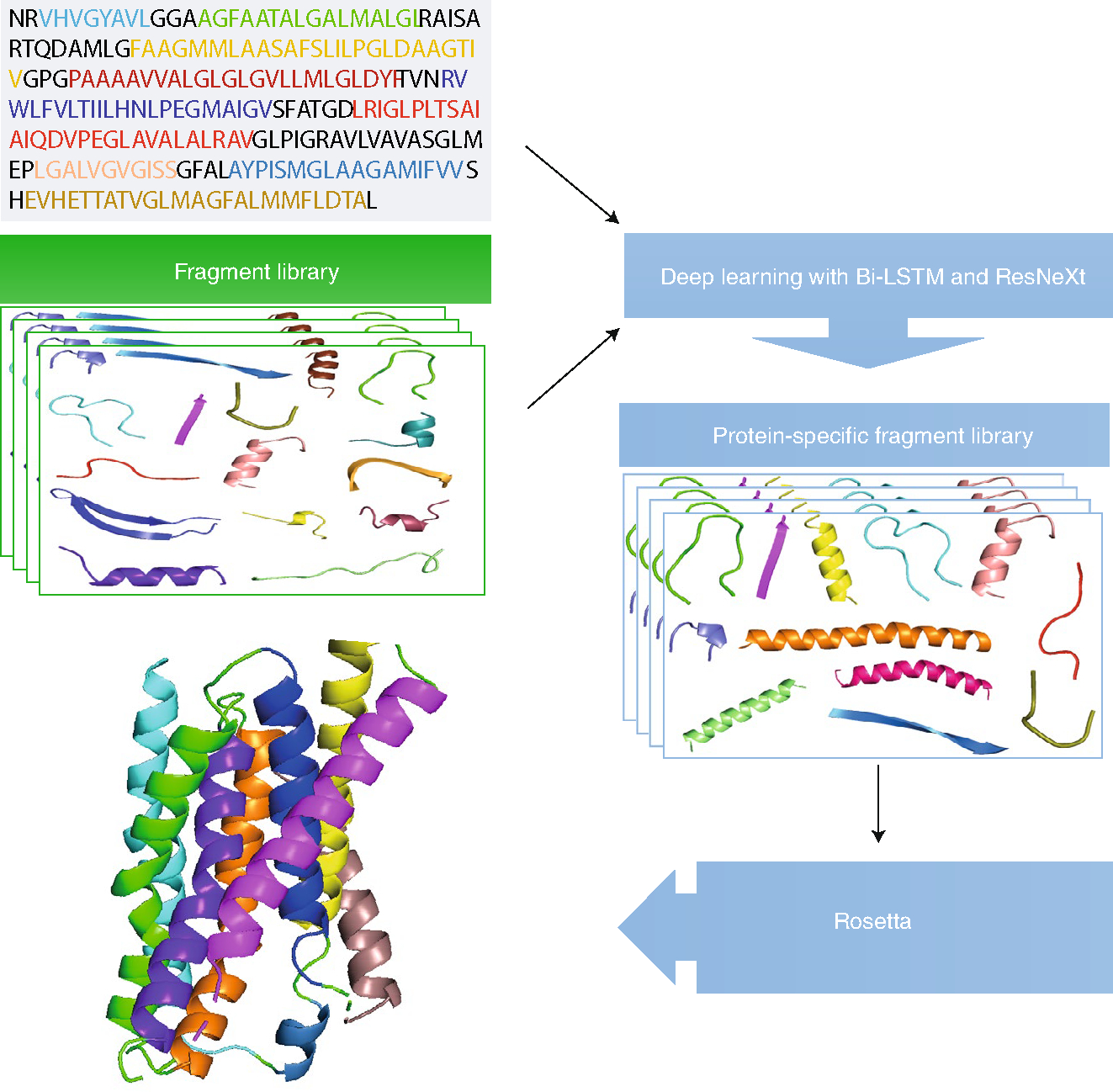

In 2018, Alphabet’s DeepMind caught the protein folding community’s attention by winning the 13th Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP13) competition with its latest artificial intelligence (AI) system, AlphaFold1. The aim of CASP is to develop and recognize state-of-the-art technology in constructing three-dimensional (3D) protein structures from protein sequences, which are abundantly available nowadays2. Experimental determination of protein 3D structures is not only time consuming, but also expensive. Determining each macrostructure takes months to years and costs tens of thousands of dollars. The importance of protein 3D structures cannot be overemphasized. These structures can be employed to elucidate protein functions, understand various biological interactions and design drugs. Many common diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, are associated with misfolded protein structures. The automated prediction of protein folds from sequences is therefore one of the fundamental challenges in biology, and has been regarded as the holy grail of molecular biophysics. AlphaFold’s top score in 25 out of 43 test proteins has excited researchers about what the future may hold for AI-based protein structure prediction. DeepFragLib (pictured), reported in Nature Machine Intelligence by Tong Wang et al.3, represents a new advance of this forefront.

There are currently two main categories of protein structure prediction techniques: template-based models and template-free models, depending on whether or not an existing template structure is employed. Template-based modelling is typically more accurate if a good template can be found, as it exploits existing protein structures. Technically, this approach is relatively mature and can be used by non-experts. However, for a protein without any existing template, template-free modelling has to be employed to construct its structure. There are two significant types of template-free modelling approaches: fragment-based assembly and ab initio or de novo folding. The latter seeks to build 3D structures ‘from scratch’ using physical principles. The success of de novo methods depends crucially on an accurate energy function, an efficient conformational search algorithm for identifying low-energy states, and the ability to discriminate native-like structures from decoys. However, fragment-based assembly is the dominant technique due to its higher accuracy and higher capability whenever a good template is difficult to identify or otherwise unavailable.

AlphaFold assembles the most probable fragments based on the co-evolution analysis of a multiple sequence alignment. Such analysis infers spatial proximity by detecting mutations that occurred in the same evolutionary timeframes in response to other mutations. Additionally, it makes use of its formidable computing power to manage truly deep neural networks that identify co-evolutionary patterns in protein sequences4 in terms of contact distributions and angular restraints. Furthermore, AlphaFold uses deep learning to generate a protein-specific statistical potential using a ‘learned reference state’1, instead of a physical-based reference state5. AlphaFold’s performance represents a great leap in protein structure prediction, but is by no means the endgame of the field. In fact, the average high-accuracy global distance topology score predicted by AlphaFold is less than 40, where 100 is the perfect score1.

Wang et al.’s DeepFragLib advances the field by introducing deep learning to another central component of protein structure prediction: protein-specific fragment libraries. These libraries are prebuilt databases for assembling proteins. The efficient assembly of near-native conformations relies on high-quality, native-like fragments for every segment of a protein. The authors built such a library using three separate modules. Among them, a classification module was trained to make a simple two-state prediction of whether or not a fragment is near-native. Multiple bidirectional long short-term memory recurrent neural networks were employed for fragments with sizes of 7 to 15 residues. Knowledge distillation then reduces the size of the model, removing most unproductive fragments by recommending only the top few. The second module, based on the aggregated residual transformation for deep neural networks, uses the pattern learned from the classification module to predict the distance of a fragment from its corresponding native fragment. This refined prediction was trained by a separate dataset made of structural folds from the Structural Classification of Proteins (SCOP)6 database. The final module selects top fragments from the regression module at a given cut off. If fewer than a certain number of fragments were found for a specific sequence position (for example, in a loop region), the cut off is either relaxed or additional fragments were supplied from seven-residue fragments from the classification module, in order to achieve a minimum number of fragments per sequence position. A few parameters in the last module were trained by the CASP10 dataset. Three separate training sets for three separate modules provide a substantially improved protein-specific library in terms of precision (the fraction of near-native fragments), coverage (the fraction of positions with at least one near-native fragment) or the depth (the position-average number of selected fragments). It remains to be seen how much further AI can take us towards solving the protein structure prediction problem.

Illustration of the DeepFragLib method for constructing protein-specific fragment libraries.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

References

- 1.AlQuraishi M Bioinformatics 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz422 (2019). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moult J, Fidelis K, Kryshtafovych A, Schwede T & Tramontano A Proteins 86, 7–15 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang T et al. Nat. Mach. Intell. 10.1038/s42256-019-0075-7 (2019). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang S, Sun S, Li Z, Zhang R & Xu J PLoS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005324 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou Y, Zhou H, Zhang C & Liu S Cell Biochem. Biophys. 46, 165–174 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandonia J-M, Fox NK & Brenner SE J. Mol. Biol. 429, 348–355 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]