Abstract

Background:

The availability of appropriate alcohol-related stimuli is a crucial concern for the evaluation and treatment of patients with alcohol dependence syndrome. The study aimed to standardize alcohol-related images with cultural relevance to the Indian setting.

Methods:

We produced an extensive database of 203 pictures, the Indian Alcohol Photo Stimuli (IAPS), portraying different categories and types of alcoholic beverages, after removing the confounding effects of low-level stimulus parameters (e.g. brightness and blurriness). Thirty patients with alcohol dependence syndrome, currently abstinent, rated each image on visual analog scale (VAS) ranging from 0 (no craving) to 10 (extreme), to determine how typical the stimuli served as craving-relevant stimuli.

Results:

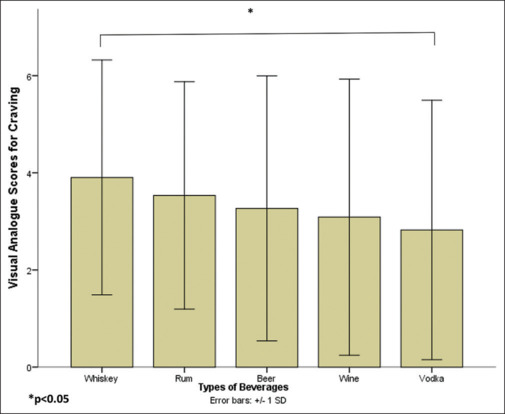

The mean VAS scores across beverages (ordered from highest to lowest) were whiskey >rum >beer >wine >vodka. Repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed a significant difference in mean VAS scores across beverages (F = 2.93, df = 2.9/86.3, P = 0.039, Greenhouse–Geisser corrected); the effect size for the difference was small (ηp2 = 0.092). A post hoc Bonferroni shows significantly higher VAS scores with whiskey compared with vodka (P = 0.029), whereas the scores were similar across other beverages. A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA for interaction between type of alcoholic beverages and activity was not significant (F = 2.67, df = 2.6/76.6, P = 0.061, Greenhouse–Geisser corrected).

Conclusions:

We created a standardized alcohol-related image database for studying cue-reactivity paradigms in individuals with alcohol use disorder (AUD). Further research is needed to validate the impact of image features on cue reactivity.

Keywords: Alcohol, alcohol dependence, craving, cue reactivity

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol craving is a pathological condition, characterized by an overwhelming need to drink alcohol, which is maintained by inadequate inhibitory control to abstain.[1,2,3] According to a recent systematic review, alcohol craving is a multidimensional construct associated with specific cognitive processes, such as attentional bias toward alcohol-related content,[4] implicit beliefs about alcohol consumption,[5] conditioning processes,[6] and motivational approach tendencies.[7]

Research shows that people with alcohol use disorder (AUD) have higher than average alcohol consumption and have greater brain and psychophysiological responsiveness when confronted with alcohol-related stimuli.[8,9,10] Cue-reactivity paradigms, which include the presentation of alcohol cues and assessment of reactions, are often used in laboratories to gain a better understanding of the craving for alcohol in people with AUD.[3,11] At the same time, cues may be provided in several ways, including in vivo (e.g., pouring, smelling, or even drinking alcohol of choice) or imaginal (e.g., conjuring imagined situations associated with past drinking), auditory (e.g., opening of a beer can), or olfactory cues.[12,13] Pictorial presentations are preferred because they are realistic, easier to establish and implement in experimental paradigms, and easier to control than other stimuli.[14,15] Furthermore, cue-exposure treatment (CET) that involves regular exposure to stimuli that elicit cravings to prevent future relapses was also developed based on the cue-reactivity paradigms.[16]

Classical conditioning underpins this cue-exposure paradigm. According to the theory of classical conditioning, alcohol-related cues (e.g., favorite drinks, bar, and drinking partners) may cause conditioned reactions, such as alcohol cravings, even in the absence of alcohol stimuli.[17] As a result, empirical data reveal that contexts and cues associated with alcohol play a significant role in the development and maintenance of AUD.[18] Cue-reactivity approaches are being used in alcohol research to better understand how people respond to images of alcohol; however, the methods used to collect these images have been inconsistent. Some studies included images found online,[19] or that originated from magazines or amateur photographs,[20] whereas others did not report where they obtained their alcohol images.[14] Additionally, even if standardized images of alcohol do currently exist, their cultural relevance to the Indian setting is limited.

In India, drinking habits vary significantly between the southern and northern parts of India and even between members of various classes living in the same locality. There are also significant cultural distinctions between urban and rural regions. Based on the results from only one of these groups, it is difficult to generalize the drinking habits of all Indian ethnic and cultural groupings.[21] Arrack, palm wine, and other home brews have historically been accessible in India and are still available today, although many of them have been substantially displaced by the widespread Indian-made foreign liquor (IMFL). Whiskey, rum, gin, and brandy make up IMFL, which has a maximum alcohol concentration of 42.8%. High-concentration alcohol has replaced traditional beverages as a popular beverage throughout the years because of improved fermentation and distillation techniques, better packaging, and more enticing sales channels.[22] Given the above challenges and diversity, there is a need for a standardized set of photographic alcohol stimuli with cultural relevance to the Indian setting. These images should accurately represent real-world cues and be tested on patients with alcohol dependence syndrome. Kumar et al.[23] and Holla et al.[24] have developed and standardized alcohol image databases from India. However, these databases contain images that prominently display brand names and complex imagery, which may limit their utility for certain types of research, such as eliciting event-related potentials. Therefore, we aimed to a) develop an alcohol-related image database relevant to the Indian setting (Indian Alcohol Photo Stimuli, IAPS) that elicits craving for alcohol and b) identify the images that elicit higher craving based on the type of alcoholic beverage and the context in patients with AUD. The images that elicit higher craving could be used in cue-reactivity paradigms in research.

METHODS

Participants

This was a cross-sectional observational study conducted at Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, a tertiary care center in South India. This study was approved by the Kasturba Hospital Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC-753-2020). The study protocol is also registered in the Clinical Trial Registry of India (CTRI/2021/03/032163). Thirty male in-patients, aged between 18 and 55 years, diagnosed with alcohol dependence as per International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) criteria by a consultant psychiatrist, and undergoing detoxification at the Dr. A. V. Baliga Hospital, Udupi, were recruited. Patients with harmful use of any other psychoactive substance other than nicotine or caffeine, presence of any chronic physical illness (hepatic encephalopathy, chronic renal disease, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, and thyroid disorders), presence of any chronic neurological illness (epilepsy, traumatic brain injury, stroke, and degenerative disorders), and presence of major comorbid psychiatric illness were excluded.

IAPS

We planned to create a standardized set of photographic alcohol stimuli, IAPS, with cultural relevance to the Indian setting, keeping the previous image sets as a reference. A database of 508 images featuring different types and categories of alcoholic beverages was created from photographs taken in local liquor shops in Manipal, Karnataka, India, and from freely available online sources, and previously standardized alcohol-related images from both Indian and Western settings.[23,25] Finally, we retained a total of 203 images after excluding those with poor quality, inadequate brightness, blurred visuals, alcohol bottles displaying brand names, and duplicate entries, to remove the confounding effect of low-level stimulus parameters [Supplementary Table 1]. The final database comprises six types of alcoholic beverages: beer, gin, vodka, rum, wine, and whiskey. Within this database, alcohol-related pictures depict these beverages in various forms, including multiple bottles, single bottles, cheers, tetra packs, glasses, bottles, drink in a glass, alcohol pouring in the glass, and cans. The final images in the database were color photographs with dimensions of 1280 × 720 pixels and resolutions of 96 dpi. To ensure contextual standardization, we edited the images, incorporating a gray background, which effectively removed any connotations of specific settings, locations, or individuals in the photograph (representative images in Figure 1). We created a picture set that featured stimuli in two different settings: active and inactive. In the active setting, human interaction with the stimulus was captured (e.g. drinking from a beer bottle or bottle of soda), which could be less and more. Inactive scenes showed the photographs of the stimulus alone (e.g. a can of beer or juice). Throughout the images, no other contextual cues were included, and there were no faces or other identifiable elements displayed. However, some photographs have featured hands holding the drinks or lifting them to their mouths. We categorized the images based on a) the type of beverages (beer, gin, vodka, rum, wine, and whiskey) and b) the presence or absence of activity (activity vs static).

Supplementary Table 1.

List of all images in Indian Alcohol Photo Stimuli* (n=203)

| Static | Beverages |

Other | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beer | Vodka | Rum | Wine | Whiskey | ||

| Can | Beer Cans (BC) 1-2 |

- | - | - | - | - |

| Tetra pack | - | - | Rum Tetra pack (RT) 1-5 | - | Whiskey Tetra pack (WKYT) 1-13 | - |

| Single bottle | Beer Single Bottle (BS) 1-5 | Vodka Single Bottle (VS) 1-9 | Rum Single Bottle (RS) 1-6 | Wine Single Bottle (WS) 1-3 | Whiskey Single Bottle (WKYS) 1-23 | - |

| Multiple bottles | Beer Multiple Bottles (BM) 1-13 | Vodka Multiple Bottles (VM) 1-9 | Rum Multiple Bottles (RM) 1-9 | Wine Multiple Bottles (WM) 1-6 | Whiskey Multiple Bottles (WKYM) 1-38 | Multiple Mottles (MB) 1-4 |

| Glass | Beer Glass (BG) 1-3 | Vodka Glass (VG) 1-2 | - | Wine Glass (WG) 1-3 | Whiskey Glass (WKYG) 1-4 | - |

| Bottle-Glass | - | Vodka Bottle-Glass (VBG) 1-3 | Rum Bottle -Glass (RBG) 1 | Wine Bottle-Glass (WBG) 1-5 | Whiskey Bottle Glass (WKYBG) 1-9 | - |

| Activity | ||||||

| Drinking | Beer Drinking (BD) 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Pouring | Beer Pouring (BP) 1-3 | Vodka Pouring (VP) 1-4 | Rum Pouring (RP) 1 | Wine Pouring (WP) 1-4 | Whiskey Pouring (WKYP) 1-12 | - |

| Cheers | - | - | - | - | - | Cheers (C) 1-3 |

*Available on request from the authors

Figure 1.

Contextual standardization of the alcohol-related image set (representative images)

Procedure

The recruited participants were explained the study’s objective, and we obtained written informed consent. Demographic and clinical details, including alcohol and drug use history and preference for the type of alcohol, were obtained. Socioeconomic status was as per the modified Kuppuswamy scale.[26] Alcohol-related stimuli were shown on a full-screen 15-inch color laptop placed 1 meter away from the participants. Stimulus-induced craving was assessed using a visual analog scale (VAS) with scores ranging from 0 (no craving) to 10 (extreme). The images were displayed for approximately 10–15 secs, and the participants were instructed to mark on the VAS scale immediately after viewing it. The images were changed by the researcher once the participants responded to the VAS. The order of the images was maintained for all participants.

Statistical analysis

The data obtained were analyzed using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Descriptive statistics included frequency, percentages, means, and standard deviations. Repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to determine whether the mean craving scores in alcohol-dependent patients differed across the types of alcoholic beverages and activity. A Greenhouse–Geisser correction was applied considering the violation of the sphericity assumption. A post hoc Bonferroni test was used to examine mean differences between multiple groups. Effect sizes were reported as partial η squared (ηp2). The cutoff values of ηp2 for small, medium, and large effect sizes were 0.09, 0.14, and 0.22, respectively. All P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

Thirty male alcohol-dependent patients, currently abstinent, were recruited [Table 1]. The mean age of participants was 39.9 (standard deviation (SD) 7.6, range 27–55) years. The majority of the patients were married (56.7%), had primary school education (50%), and were all employed. Most of them live in nuclear family (70%), rural areas (53.3%), and belong to upper lower socioeconomic class (76.6%).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics (n=30)

| M (SD)/n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age | 39.9 (7.6) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 30 (100) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 17 (56.7) |

| Single | 12 (40) |

| Divorced | 1 (3.3) |

| Education | |

| Illiterate | 2 (6.6) |

| Primary school certificate | 15 (50) |

| Middle School certificate | 3 (10) |

| High school certificate | 8 (26.6) |

| Intermediate or diploma | 1 (3.3) |

| Graduation | 1 (3.3) |

| Employment status* | |

| Elementary occupation | 27 (90) |

| Businessman | 1 (3.3) |

| Farmer | 2 (6.6) |

| Living arrangement | |

| Nuclear | 21 (70) |

| Joint | 9 (30) |

| Monthly income in INR* | |

| ≤10,001 | 8 (26.6) |

| 10002–29,972 | 5 (16.6) |

| 29,973–49961 | 15 (50) |

| 49,962–74,755 | 2 (6.6) |

| Socioeconomic class* | |

| Upper middle | 1 (3.3) |

| Lower middle | 1 (3.3) |

| Upper lower | 23 (76.6) |

| Lower | 5 (16.6) |

| Residential area | |

| Rural | 16 (53.3) |

| Semi-urban | 7 (23.3) |

| Urban | 7 (23.3) |

*Based on a modified Kuppuswamy socioeconomic scale (updated for 2020)[25]

The mean age of first alcohol use was 18.4 years [Table 2]. The mean duration of alcohol dependence was 30.96 years. Around 70% of the participants had psychiatric comorbidity and 93.94% of the participants had a history of any period of abstinence. The participants were assessed at an average of 7.8 days (SD 4.27, range 1–24 days). The majority of them have a previous history of hospitalization (73.34%) and tobacco use (86.66%).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of the sample (n=30)

| M (SD)/n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age at first alcohol use | 18.40 (5.06) |

| Age at regular alcohol use† | 27.76 (9.57) |

| Age at dependence on alcohol | 30.96 (7.81) |

| Physical comorbidity | |

| Present | 4 (13.33) |

| Absent | 26 (86.67) |

| Psychiatric comorbidity | |

| Present | 21 (70) |

| Absent | 9 (30) |

| Any period of abstinence | |

| Present | 28 (93.34) |

| Absent | 2 (6.67) |

| Last drink in days | 7.8 (4.27) |

| Previous history of hospitalization | |

| Present | 22 (73.34) |

| Absent | 8 (26.67) |

| Previous history of out-patient alcohol deaddiction treatment | |

| Present | 13 (43.34) |

| Absent | 17 (56.66) |

| Tobacco use* | |

| Present | 26 (86.66) |

| Absent | 4 (13.34) |

*Tobacco use includes both chewable and smokable forms; †daily drinking on most days of the week was considered as regular use

Craving scores with IAPS images

The mean craving scores for all images across types of beverages and activity are summarized in Table 3. Overall, the mean craving score for all images was 4.3 (SD 3.2), ranging from 0 to 10. Mean craving scores across beverages (ordered from highest to lowest) were whiskey > rum > beer > wine > vodka. Repeated-measures ANOVA showed a significant difference in mean VAS scores across beverages (F = 2.93, df = 2.9/86.3, P = 0.039, Greenhouse–Geisser corrected); the effect size for the difference was small (ηp2 = 0.092). A post hoc Bonferroni shows significantly higher VAS scores with whiskey compared with vodka (P = 0.029), whereas the scores were similar across other beverages [Figure 2].

Table 3.

Craving on VAS for the alcohol-related images (n=30)

| Types of beverages |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whiskey | Rum | Beer | Wine | Vodka | |

| Total score, M (SD) | 3.9 (2.4) | 3.5 (2.3) | 3.3 (2.7) | 3.1 (2.8) | 2.8 (2.7) |

| Md (IQR) (n=203) | 4.2 (3.2) | 3.5 (3.2) | 2.6 (3.8) | 2.4 (4.7) | 2.2 (4.1) |

| Activity, M (SD) | 3.8 (2.6) | 4.1 (2.9) | 4.1 (2.8) | 4.2 (2.8) | 4.0 (2.8) |

| Md (IQR) (n=28) | 3.3 (3.4) | 3.5 (3.2) | 3.7 (3.6) | 3.9 (3.4) | 3.7 (3.3) |

| Static, M (SD) | 3.9 (2.5) | 3.5 (2.4) | 3.2 (2.7) | 3.1 (2.9) | 2.7 (2.7) |

| Md (IQR) (n=175) | 4.1 (3.6) | 3.7 (3.1) | 2.4 (3.8) | 2.3 (5.2) | 1.8 (4.2) |

| Activity | |||||

| Pouring, M (SD) | 3.7 (2.8) | 4.1 (2.9) | 3.6 (3.6) | 2.9 (3.0) | 3.3 (3.2) |

| Md (IQR) (n=24) | 3.2 (4.2) | 3.5 (3.3) | 3.0 (6.5) | 1.7 (4.6) | 2.3 (4.8) |

| Cheers, M (SD) | 4.5 (3.2) | - | - | - | - |

| Md (IQR) (n=3) | 4.0 (4.2) | ||||

| Drinking, M (SD) | - | - | 4.4 (3.9) | - | - |

| Md (IQR) (n=1) | 5.0 (8.2) | ||||

| Static | |||||

| Cans, M (SD) | - | - | 2.7 (3.1) | - | - |

| Md (IQR) (n=2) | 1.0 (6.0) | ||||

| Glass, M (SD) | 4.1 (2.9) | - | 4.6 (3.4) | 3.0 (2.9) | 2.8 (2.9) |

| Md (IQR) (n=12) | 4.0 (5.4) | 4.2 (3.2) | 2.5 (5.4) | 1.7 (5.6) | |

| Tetra pack, M (SD) | 3.5 (2.3) | 3.7 (2.7) | - | - | - |

| Md (IQR) (n=18) | 3.8 (3.7) | 3.9 (3.4) | |||

| Bottle and glass, M (SD) | 4.5 (3.5) | 4.7 (3.4) | - | 2.9 (3.3) | 2.8 (3.3) |

| Md (IQR) (n=18) | 3.9 (6.7) | 5.0 (6.0) | 1.8 (5.1) | 1.8 (5.2) | |

| Single bottle, M (SD) | 3.7 (2.8) | 3.2 (2.7) | 3.3 (2.9) | 2.8 (2.9) | 2.6 (2.6) |

| Md (IQR) (n=46) | 3.2 (4.2) | 2.6 (4.4) | 2.1 (5.6) | 2.2 (4.3) | 1.3 (4.4) |

| Multiple bottles, single beverage, M (SD) | 4.0 (2.8) | 3.4 (2.7) | 2.9 (2.9) | 3.4 (3.2) | 2.8 (2.8) |

| Md (IQR) (n=75) | 4.2 (5.2) | 3.4 (4.1) | 2.1 (4.1) | 2.3 (6.7) | 1.5 (3.9) |

| Multiple bottles, different beverages, M (SD) | 4.3 (3.2) | ||||

| Md (IQR) (n=4) | 4.9 (6.1) | ||||

SD: standard deviation; IQR: interquartile range; n: number of images

Figure 2.

Mean VAS scores for craving for beverage types (error bars represent ± 1 SD)

Mean craving scores across beverages with images depicting activity were wine >rum = beer >vodka >whiskey. A repeated-measures ANOVA showed no significant difference in mean VAS scores across beverages (F = 1.83, df = 1.4/41.5, P = 0.65, Greenhouse–Geisser corrected). Mean craving scores across beverages with static images were whiskey >rum >beer >wine >vodka. Repeated-measures ANOVA showed a significant difference in mean VAS scores across beverages (F = 3.15, df = 2.9/84.1, P = 0.031, Greenhouse–Geisser corrected); the effect size for the difference was small (ηp2 = 0.098). A post hoc Bonferroni shows significantly higher VAS scores with whiskey compared with vodka (P = 0.022), whereas the scores were similar across other beverages.

Among different activity images, whiskey with cheers had the highest mean VAS scores (4.5, SD 3.2), followed by drinking beer (4.4, SD 3.9), whereas pouring wine elicited the lowest mean VAS scores (2.9, SD 3.0). Among static images, rum in bottle and glass had the highest mean VAS scores (4.7, SD 3.4), followed by beer in glass (4.6, SD 3.4), whereas vodka in single bottle had the lowest mean VAS scores (2.6, SD 2.6). A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA for interaction between type of alcoholic beverages and activity was not significant (F = 2.67, df = 2.6/76.6, P = 0.061, Greenhouse–Geisser corrected); the effect size for the interaction was ηp2 = 0.084).

DISCUSSION

We developed and standardized a comprehensive alcohol-related image set, IAPS, for future use in the alcohol cue-reactivity paradigm. The findings indicated differences in self-reported levels of craving with images of types of alcohol, whiskey >rum >beer >wine >vodka. Our data also suggested significantly higher self-reported cravings with images of whiskey compared with vodka. Consistent findings have been found in a previous study conducted in Bangalore, wherein survey results found preferences for whiskey (49%) compared with other types of beverages.[27] Similar higher craving scores were obtained for whiskey images over vodka when static images were used; however, for the images depicting activity there was no difference across beverages. This finding is similar to earlier research that suggests that whiskey, beer, and wine were the most commonly reported craving-related beverages by alcohol-dependent patients and that their presence in a range of environments, including stimuli (e.g. alcohol bottles and glasses), social interactions, and perceived leisure time, triggered alcohol cravings.[28,29]

Whiskey with cheers and rum in bottle and glass had the highest craving scores, followed by beer in glass and drinking beer. Among others, beer is considered one of the most preferred beverages worldwide.[30] These findings are consistent with the previous study, which found that alcohol users display a significant attentional bias toward alcohol-related images that are simple than complex images. One possible explanation for the absence of attentional bias in the complex picture condition is the higher cognitive processing required by the relatively more complex visual stimuli portrayed in complex images. In addition, the visual environment of complex pictures tended to stimulate greater searching and scanning activity than simple ones.[31]

Learning theories of alcohol dependence hypothesize that stimuli previously linked with alcohol use might activate autonomic responses that prompt craving and increased alcohol consumption and minimize the latency of relapse.[32,33,34] Consequently, we demonstrated that stimuli that arouse craving and induce physiological reactions may be found in other contexts than those that conventionally serve as alcohol cues, such as images of bottles and other containers containing alcohol. Even without any representation of alcohol itself, contextual factors in a drinking environment seem to be significant modulators that also cause cue-responsiveness. The average craving scores that were reported were less than half of the maximum score on the scale. Possible explanations for this include the perception that there was less opportunity to drink because it was in a controlled environment and concern that a high craving score might make clinicians or family members fear that the patient would relapse and require a longer hospital stay.

During the preliminary search for the images on online sites (dreamstime.com and shutterstock.com) for alcohol-related images and previously standardized image sets, the majority of the images were standardized on a Western population, such as the International Affective Picture System (IAS), Amsterdam Beverage Picture Set (ABPS), Geneva Appetitive Alcohol Pictures (GAAP), and Normative Appetitive Picture System (NAPS). Alcoholic beverages from these sets contained alcohol brands and physical and contextual image characteristics not readily recognizable in a cross-cultural context. The studies conducted in Bangalore had created a similar picture set, with standardized images of alcohol[23,24]; however, the alcoholic beverages contained labels displaying brand names, and images of substances were depicted in various settings. The brand’s effect on alcohol consumption is complex. The more severe the AUD, the less confidence patients felt in their capacity to manage alcohol cravings and the desire to drink after watching alcohol advertisements.[35,36] While these and other recent research studies focused on the impact of brands in alcohol marketing and alcohol use among those with AUD, there is some evidence to suggest that AUD patients are affected by the type of alcohol, the alcohol content by volume, and the brand (24%) when buying a particular kind of alcohol.[30]

While creating an alcohol-related image set, it was necessary that multidimensional cues, such as no facial expressions or scenes containing actors, are not captured, as the effect of these is unknown. The variety of content depicted in the images makes it difficult to ascertain precisely what salient features of the image participants have responded to. During the standardization and validation processes, both of these sets of characteristics should be taken into account to minimize the possible confounding effect and increase explanatory power.[13,19,37]

There were a few challenges faced during the collection of photographs to eliminate unnecessary cues, such as background, brand names, and ambiance of the place. We decided to take pictures in local bars and wine shops in Manipal to make them relevant to the local context. Also, rather than focusing on various self-reported responses, such as valence, arousal, dominance, pleasantness and unpleasantness, emotionality, and desire or urge to drink, we used cue-reactivity craving for studies on relapse in alcohol-dependent patients. Other self-reported responses can be considered in future research.

Limitations

The limitations include a small sample size and the absence of a healthy control group. To investigate the predictive validity, a longitudinal research design would be needed. Also, there were no females in our sample, consistent with the population prevalence; however, it limits generalizability. We studied only IMFL, and the drinking preference of the sample was not considered, although country liquor is also commonly used in India. Furthermore, the validation of the photographs was solely based on self-reports and did not include further physiological measures, which is another limitation, as social desirability could influence the responses of some individuals. Future studies may add psychophysiological measurements, such as event-related potentials along with clinical ratings. Another limitation is the lack of personalization of stimulus sets based on a participant’s drinking preferences,[10] which could explain the lower scores. Additionally, there is a possibility of the carryover effect of the photo stimuli, even though a standard method was adopted for the administration. Future studies could investigate the optimum exposure to these stimuli and use distractors to reduce carryover effects.

Future directions and implications

The research reported here has several practical and clinical implications. The current study developed IAPS images with cultural relevance to the local Indian context and having higher craving potential, which can be used to develop relevant cue-reactivity paradigms. The IAPS images can be used in experimental research using psychophysiological measures that can provide objective measures of reactivity to complement self-reported instruments. In terms of clinical significance, the responses to IAPS images can help researchers better understand how people respond to alcohol cues. Also, these may have implications for the behavioral treatment of ADS, particularly for extinction training and for enhancing our knowledge of the role of learning in the development of drug dependence. The IAPS images have the potential to be used as a tool for assessing pretreatment valence and arousal toward alcohol. Clients may exhibit increased arousal in response to certain kinds of alcohol in the photograph set (e.g. more arousal in response to pictures of beer), allowing clinicians to tailor therapy to that beverage type. Exposure to situations involving alcohol during treatment may be more beneficial than cue exposure alone or conventional treatment methods, as contextual features of drinking situations might also act as relapse triggers. Clinicians may also track improvement by looking at changes in self-reported valence and arousal and differences in psychophysiological responses, which could be considered for future research.

CONCLUSIONS

We developed IAPS as a standard set of images of alcoholic beverages that can be used in alcohol cue-reactivity tasks in future research. These images could be validated in future studies for wider use.

Supplementary Table 1: List of all images in Indian Alcohol Photo Stimuli (the images are available on request from the authors)

Financial support and sponsorship

The research was funded by a Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) grant from the Dhirubhai Ambani Foundation.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the staff members of Axxonet System Technologies, Bangalore, Karnataka, India, for their technical support, and Dr PV Bhandary, Director, and other staff members of Dr AV Baliga Memorial Hospital, Udupi, Karnataka, India, for their help in data collection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Huang Y, Mohan A, De Ridder D, Sunaert S, Vanneste S. The neural correlates of the unified percept of alcohol-related craving: A fMRI and EEG study. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1–2. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18471-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serre F, Fatseas M, Swendsen J, Auriacombe M. Ecological momentary assessment in the investigation of craving and substance use in daily life: A systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;148:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stein M, Fey W, Koenig T, Oehy J, Moggi F. Context-specific inhibition is related to craving in alcohol use disorders: A dangerous imbalance. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2018;42:69–80. doi: 10.1111/acer.13532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manchery L, Yarmush DE, Luehring-Jones P, Erblich J. Attentional bias to alcohol stimuli predicts elevated cue-induced craving in young adult social drinkers. Addict Behav. 2017;70:14–7. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monk RL, Heim D. A critical systematic review of alcohol-related outcome expectancies. Subst Use Misuse. 2013;48:539–57. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.787097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Lier HG, Pieterse ME, Schraagen JM, Postel MG, Vollenbroek-Hutten MM, de Haan HA, et al. Identifying viable theoretical frameworks with essential parameters for real-time and real world alcohol craving research: A systematic review of craving models. Addict Res Theory. 2018;26:35–51. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noyes ET, Schlauch RC. Examination of approach and avoidance inclinations on the reinforcing value of alcohol. Addict Behav. 2018;79:61–7. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batschelet HM, Tschuemperlin RM, Moggi F, Soravia LM, Koenig T, Pfeifer P, et al. Neurophysiological correlates of alcohol-specific inhibition in alcohol use disorder and its association with craving and relapse. Clin Neurophysiol. 2021;132:1290–301. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2021.02.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cassisi JE, Delehant M, Tsoutsouris JS, Levin J. Psychophysiological reactivity to alcohol advertising in light and moderate social drinkers. Addict Behav. 1998;23:267–74. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(97)00038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tapert SF, Cheung EH, Brown GG, Frank LR, Paulus MP, Schweinsburg AD, et al. Neural response to alcohol stimuli in adolescents with alcohol use disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:727–35. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qureshi AW, Monk RL, Pennington CR, Li X, Leatherbarrow T. Context and alcohol consumption behaviors affect inhibitory control. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2017;47:625–33. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heinze M, Wölfling K, Grüsser SM. Cue-induced auditory evoked potentials in alcoholism. Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;118:856–62. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grüsser SM, Heinz A, Flor H. Standardized stimuli to assess drug craving and drug memory in addicts. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2000;107:715–20. doi: 10.1007/s007020070072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stritzke WG, Breiner MJ, Curtin JJ, Lang AR. Assessment of substance cue reactivity: Advances in reliability, specificity, and validity. Psychol Addict Behav. 2004;18:148–59. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.2.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramirez JJ, Monti PM, Colwill RM. Alcohol-cue exposure effects on craving and attentional bias in underage college-student drinkers. Psychol Addict Behav. 2015;29:317–22. doi: 10.1037/adb0000028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loeber S, Croissant B, Heinz A, Mann K, Flor H. Cue exposure in the treatment of alcohol dependence: Effects on drinking outcome, craving and self-efficacy. British Br J Clin Psychol. 2006;45:515–29. doi: 10.1348/014466505X82586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anton RF. What is craving? Models and implications for treatment. Alcohol Res Health. 1999;23:165–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bottlender M, Soyka M. Impact of craving on alcohol relapse during, and 12 months following, outpatient treatment. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004;39:357–61. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pulido C, Brown SA, Cummins K, Paulus MP, Tapert SF. Alcohol cue reactivity task development. Addict Behav. 2010;35:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petit G, Kornreich C, Noël X, Verbanck P, Campanella S. Alcohol-related context modulates performance of social drinkers in a visual Go/No-Go task: A preliminary assessment of event-related potentials. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37466. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037466. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone. 0037466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett LA, Campillo C, Chandrashekar CR, Gureje O. Alcoholic beverage consumption in India, Mexico, and Nigeria: A cross-cultural comparison. Alcohol Health Res World. 1998;22:243. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nayak MB, Kerr W, Greenfield TK, Pillai A. Not all drinks are created equal: Implications for alcohol assessment in India. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43:713–8. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar R, Kumar KJ, Benegal V, Roopesh BN, Ravi GS. Effectiveness of an integrated intervention program for alcoholism: Electrophysiological findings. Indian J Psychol Med. 2021;43:223–33. doi: 10.1177/0253717620927870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holla B, Viswanath B, Agarwal SM, Kalmady SV, Maroky AS, Jayarajan D, et al. Visual Image-Induced Craving for Ethanol (VICE): Development, validation, and a pilot fMRI study. Indian J Psychol Med. 2014;36:164–9. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.130984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petit G, Cimochowska A, Cevallos C, Cheron G, Kornreich C, Hanak C, et al. Reduced processing of alcohol cues predicts abstinence in recently detoxified alcoholic patients in a three-month follow up period: An ERP study. Behav Brain Res. 2015;282:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saleem SM, Jan SS. Modified Kuppuswamy socioeconomic scale updated for the year 2019. Indian J Forensic Community Med. 2019;6:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Girish N, Kavita R, Gururaj G, Benegal V. Alcohol use and implications for public health: Patterns of use in four communities. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35:238–44. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.66875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghiţă A, Teixidor L, Monras M, Ortega L, Mondon S, Gual A, et al. Identifying triggers of alcohol craving to develop effective virtual environments for cue exposure therapy. Front Psychol. 2019;10:74. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00074. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg. 2019.00074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JH, Kwon H, Choi J, Yang BH. Cue-exposure therapy to decrease alcohol craving in virtual environment. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2007;10:617–23. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.9978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guillou Landreat M, Beauvais C, Grall Bronnec M, Le Goff D, Lever D, Dany A, et al. Alcohol use disorders, beverage preferences and the influence of alcohol marketing: A preliminary study. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2020;15:90. doi: 10.1186/s13011-020-00329-8. doi: 10.1186/s13011-020-00329-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller MA, Fillmore MT. The effect of image complexity on attentional bias towards alcohol-related images in adult drinkers. Addiction. 2010;105:883–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02860.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mucha RF, Geier A, Stuhlinger M, Mundle G. Appetitive effects of drug cues modelled by pictures of the intake ritual: Generality of cue-modulated startle examined with inpatient alcoholics. Psychopharmacology. 2000;151:428–32. doi: 10.1007/s002130000508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM, Abrams DB, Rubonis AV, Niaura RS, Sirota AD, et al. Cue elicited urge to drink and salivation in alcoholics: Relationship to individual differences. Adv Behav Res Ther. 1992;14:195–210.. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wikler A. Dynamics of drug dependence: Implications of a conditioning theory for research and treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1973;28:611–616. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1973.01750350005001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sobell LC, Toneatto T, Sobell M, Leo G, Johnson L. Alcohol abusers’ perceptions of the accuracy of their self-reports of drinking: Implications for treatment. Addict Behav. 1992;17:507–11.. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90011-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Witteman J, Post H, Tarvainen M, de Bruijn A, Perna EDSF, Ramaekers JG, et al. Cue reactivity and its relation to craving and relapse in alcohol dependence: A combined laboratory and field study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2015;232:3685–96. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-4027-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wrase J, Grüsser SM, Klein S, Diener C, Hermann D, Flor HE, et al. Development of alcohol-associated cues and cue-induced brain activation in alcoholics. Eur Psychiatry. 2002;17:287–91. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(02)00676-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]