Abstract

Objective:

Certain neurologic diseases have been noted to vary by season, and this is important for understanding disease mechanisms and risk factors, but seasonality has not been systematically examined across the spectrum of neurologic disease, and methodologic guidance is also lacking.

Methods:

Using nationally representative data from the National Inpatient Sample, a stratified 20% sample of all non-federal acute care hospitalizations in the United States, we calculated the monthly rate of hospitalization for 14 neurologic diseases from 2016 to 2018. For each disease, we assessed seasonality of hospitalization using chi-squared, Edward, and Walter-Elwood tests and seasonal time series regression models. Statistical tests were adjusted for multiple hypothesis testing using Bonferroni correction.

Results:

Meningitis, encephalitis, ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, Guillain-Barre syndrome, and multiple sclerosis had statistically significant seasonality according to multiple methods of testing. Subarachnoid hemorrhage, status epilepticus, myasthenia gravis, and epilepsy had significant seasonality according to Edwards and Walter-Elwood tests but not chi-square tests. Seasonal time series regression illustrated seasonal variation in all 14 diseases of interest, but statistical testing for seasonality within these models using the Kruskal-Wallis test only achieved statistical significance for meningitis.

Interpretation:

Seasonal variation is present across the spectrum of acute neurologic disease, including some conditions for which seasonality has not previously been described, and can be examined using multiple different methods.

Introduction

For many medical conditions, the risk of developing or dying from disease varies by season, and these observations have been used to generate and support hypotheses about disease mechanisms and environmental risk factors.1 In the field of neurology, seasonal variation has been reported for acute stroke, meningitis, encephalitis, Guillain-Barre syndrome, and demyelinating disease, and these patterns have been attributed to factors such as air pollution, seasonal infections and vaccinations, and sunlight exposure.2–6 In addition to providing insights into disease pathogenesis, knowledge about seasonal variation is essential for healthcare preparedness. For example, if ischemic strokes predictably increase during certain months, hospitals could prepare by ensuring that supplies of tissue plasminogen activator and thrombectomy capabilities are sufficient to meet this need.

The current literature on seasonality in neurologic disease is limited in scope, which limits its ability to further support population health studies or interventions. While some diseases have been the subject of multiple studies, the seasonal variation of other neurologic diseases such as epilepsy and myasthenia gravis is understudied. In addition, most studies are limited to single academic centers or regions, typically clustered around densely populated cities. Results from these geographically segregated studies may not apply to rural areas or generalize across diverse meteorological climates. Previous studies have also focused on just one or two diseases at a time, making it difficult to contextualize their findings or compare the seasonality of one disease to another (e.g., How does the seasonality of stroke compare to the seasonality of encephalitis?). Finally, a number of statistical methods have been used to test for seasonality, but there is not a uniform standardized approach, and comparisons of these methods are lacking, especially in the context of large administrative healthcare datasets. In this study, we assess and compare the seasonality in hospitalization for 14 different neurologic disorders across the United States using nationally representative data from the National Inpatient Sample.

Methods

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

This study was reviewed as exempt from approval by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board due to the fully de-identified nature of the data, and individual informed consent was not required. The analysis and reporting of results comply with the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) data use agreement policy.

Code Availability

Analytic code is available by request to the corresponding author.

Dataset

The National Inpatient Sample (NIS), made available through HCUP by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), is the largest all-payer inpatient healthcare database in the United States.7 It consists of a stratified 20% sample of discharges from all non-federal acute care hospitals in the United States (approximately 7 million hospitalizations annually). The NIS dataset contains complex survey design variables (stratum, primary sampling unit) and sample weights. When analyzed using survey-weighted statistical programs, the total number of hospital admissions in the U.S. for a particular condition Hamedani et al: Seasonal Variation in Neurologic Hospitalizations can be estimated from the 20% sample. NIS contains deidentified, encounter-level information on hospital characteristics, patient demographics, diagnoses and procedures, healthcare costs, payer information. For our analysis, we used NIS data from 2016 to 2018, the most recent year available at the time of analysis. We restricted our analysis to years in which the ICD-10-CM coding system was used and excluded data from 2015 or earlier because artificial changes in prevalence estimates may occur across coding transitions.8

Study Sample

Our study sample consisted of hospitalizations of individuals with select neurological conditions during the study period. Fourteen neurologic conditions were chosen for study, representing a broad range of disease pathophysiologies (e.g., infectious, inflammatory, vascular). NIS records contain up to 40 diagnosis fields, but the first diagnosis position is considered to be the primary diagnosis or reason for hospitalization, so we queried ICD-10-CM codes in the primary diagnosis position to identify neurological hospitalizations of interest (Supplemental Table S1 and S2). Each hospitalization could only be counted once in the analysis. We then restricted the sample to non-elective hospitalizations because elective admissions may be biased towards or away from certain times of the year (e.g., winter holidays) independent of any seasonal effect on disease activity or hospitalization risk.

Statistical Analysis

Using sampling weights to account for the complex survey design of the NIS, we estimated the number of non-elective hospitalizations for each neurologic condition and the total number of non-elective hospitalizations (for any neurologic or non-neurologic condition) by month from January 2016 to December 2018. Regression and non-regression based methods were used to test for seasonality in our dataset and allow for comparison to previously published data. Non-regression tests of seasonality included the chi-square, Edwards, and Walter-Elwood tests. Chi-square tests cannot be applied over several cycles (years of data). Therefore, we calculated the average number of hospitalizations for each month across all 3 years and then pooled these monthly averages according to season: spring (March–May), summer (June–August), fall (September–November), and winter (December–February). The Edwards test of cyclicity tests whether the distribution of a variable over a particular time period approximates that of a sine curve.9 The Walters-Elwood test is an extension of the Edwards test that adjusts for temporal variation in the underlying denominator (in this case, total non-elective NIS admissions).10 We conducted our non-regression seasonality analyses using STATA/IC 15.1, and the Edwards and Walter-Elwood tests were performed using the seast package.11 Peak-to-trough ratios with 95% confidence intervals were calculated from sine curve-fitted data using Episheet.12, 13

We also used seasonal time series regression models to test for seasonality. Broadly speaking, a time series is a longitudinal dataset in which the unit of observation refers explicitly to calendar time (as opposed to visit number or another arbitrary marker of time). Time series regression models are used to analyze temporal trends within data and have two clear advantages over conventional linear regression models when used for this purpose. The first is the ability to separate the underlying trend from random or non-random fluctuation occurring at other frequencies. For example, outdoor temperature increases and decreases over the course of the day; therefore, a model of hourly temperature over a 1-month period would need to account for these diurnal fluctuations when estimating longer-term trends. The second advantage of a time series model is its ability to account for temporal autocorrelation—that is, the idea that the value of an outcome variable at time t is more strongly correlated with its value at closer time points (e.g., t-1, t + 1) than at more distant time points (e.g., t-5, t + 5). For each neurologic diagnosis of interest, we constructed a seasonal time series regression model decomposing the time series into trend, seasonal, and irregular (random) components. We used additive models, which assume a stable seasonality pattern across all 3 years of study and specified a period of 12 months for seasonality testing. To account for monthly variation in overall hospitalizations, we modeled the disease-specific monthly incidence—that is, the number of hospitalizations for a particular disease per 100,000 total non-elective NIS admissions—and assumed a constant trend component over the 3-year study period. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to test the statistical significance of seasonality from the raw time series data. In addition to nationwide trends, we performed exploratory seasonal time series regression models stratified by HCUP-defined geographic region (Northeast, South, Midwest, and West). To confirm the results of our 2016 to 2018 nationwide analysis, we performed the same analysis using data from 2012 to 2014. Seasonal time series regression was performed using R v3.5.3 software and graphed using STATA/IC 15.1. For each statistical test, we performed two-sided hypothesis testing with a Bonferroni-corrected alpha of 0.05/14 = 0.0036.

Results

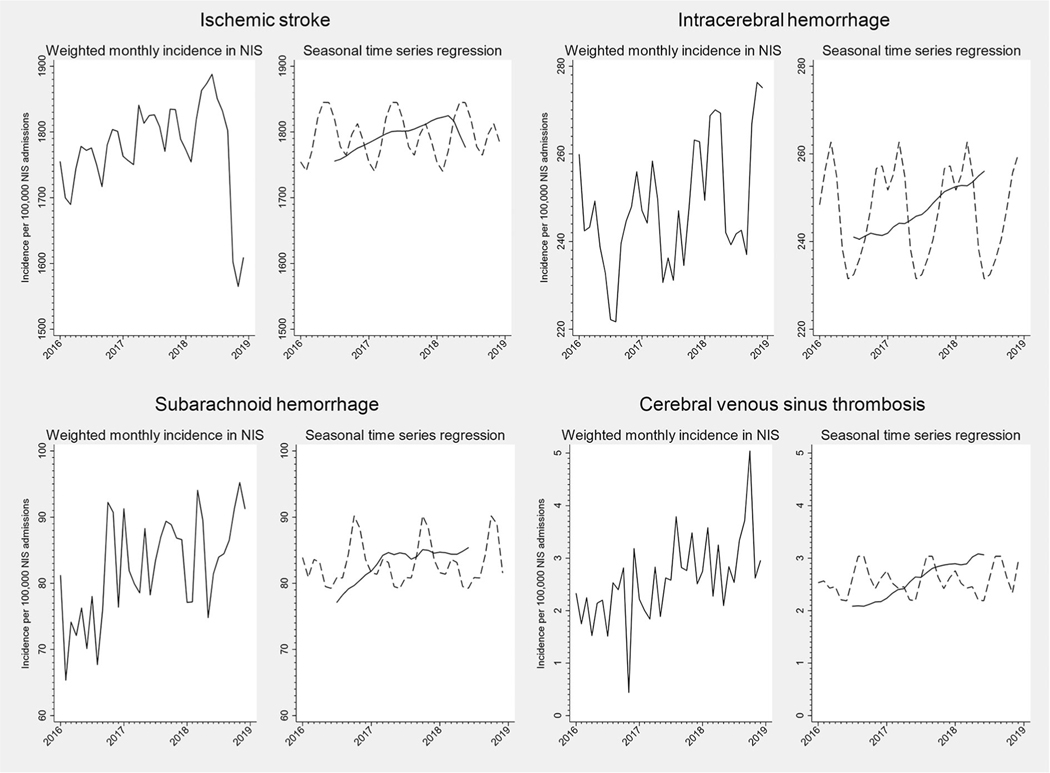

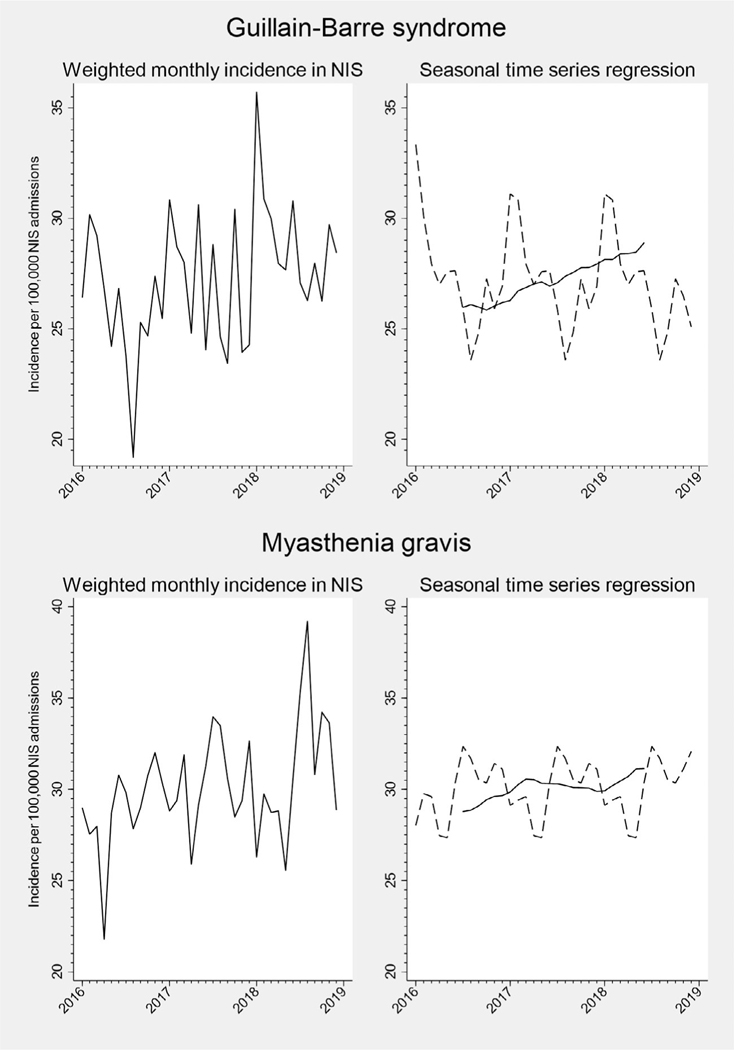

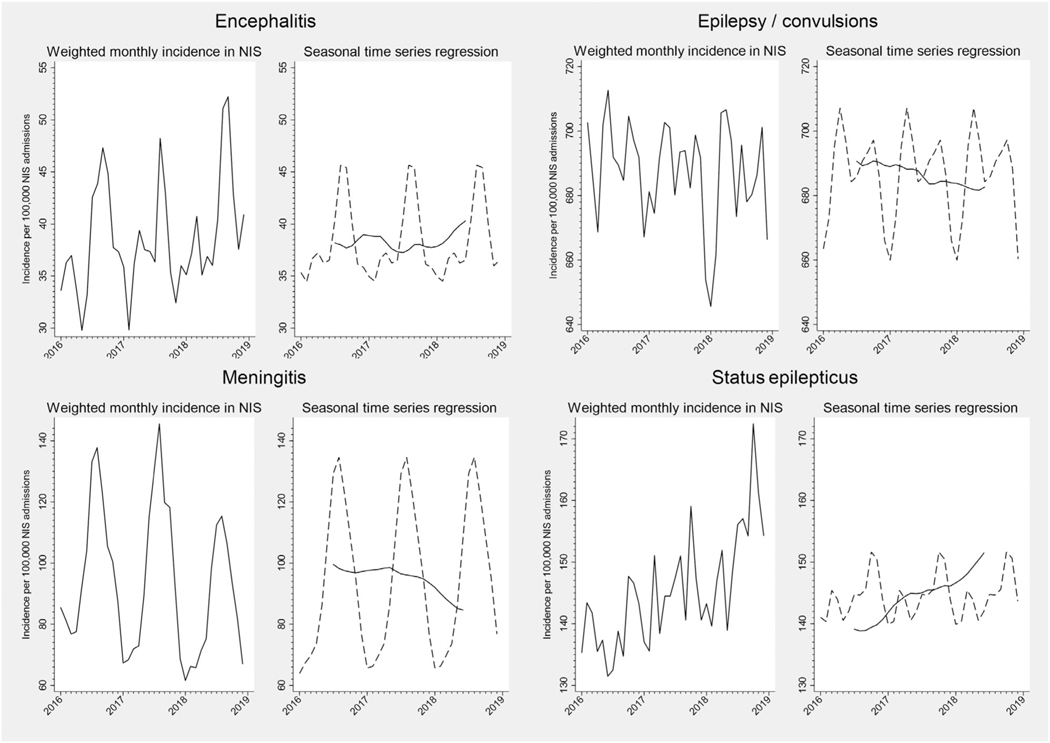

The monthly incidence of hospitalization for each neurologic disease per 100,000 non-elective NIS hospitalizations from 2016 to 2018 is shown in Figures 1 to 4. On visual inspection of these plots, there was clear seasonal variation in the incidence of hospitalizations for meningitis and encephalitis, with nearly twofold differences between summer peaks and winter troughs (Fig 2). Ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage hospitalizations also appeared to vary by season (Fig 1). Other conditions exhibited monthly variation that did not appear to follow a clear seasonal pattern in unadjusted plots (e.g., subarachnoid hemorrhage and cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, Fig 1).

FIGURE 1:

Monthly incidence and seasonal time series regression for neurovascular hospital admissions, NIS 2016 to 2018. For seasonal time series regression models, the trend curve is plotted as a solid line, and the Hanning linear-smoothed seasonal component is represented with a dotted line.

FIGURE 4:

Monthly incidence and seasonal time series regression for neuromuscular hospital admissions, NIS 2016 to 2018. For seasonal time series regression models, the trend curve is plotted as a solid line, and the Hanning linear-smoothed seasonal component is represented with a dotted line.

FIGURE 2:

Monthly incidence and seasonal time series regression for central nervous system infection and seizure-related admissions, NIS 2016 to 2018. For seasonal time series regression models, the trend curve is plotted as a solid line, and the Hanning linear-smoothed seasonal component is represented with a dotted line.

The results of our non-regression tests of seasonality are shown in Table. After correcting for multiple hypothesis testing, chi-square tests identified six neurologic conditions with statistically significant seasonal variation among emergent hospitalizations: meningitis, encephalitis, ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, Guillain-Barre syndrome, and multiple sclerosis. The Edwards test found seasonal variation in hospitalizations of these conditions, and also for subarachnoid hemorrhage, status epilepticus, myasthenia gravis, and epilepsy (after further adjustment for month length). The Walter-Elwood test yielded similar results to the Edwards test.

TABLE.

Results of Non-Regression and Seasonal Time Series Analyses of Seasonality in Neurologic Hospitalizations, NIS 2016 to 2018

| Diagnosis | Number of Hospitalizations | Chi-squared | Edwards Test | Edwards Test, Month-Adjusted | Walter-Elwood Test | Walter-Elwood Test, Month-Adjusted | Peak-to-Trough Ratio (95% CI)a | Seasonal Time Series Regression Kruskal-Wallis Test Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ischemic stroke | 1,497,670 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 1.055 (1.047–1.064) | 14.57 | 0.2029 |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | 209,305 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 1.114 (1.090–1.137) | 17.56 | 0.0923 |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 69,570 | 0.0200 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 1.124 (1.084–1.166) | 12.55 | 0.3235 |

| Dural sinus thrombosis | 2,190 | 0.3500 | 0.0144 | 0.0358 | 0.0112 | 0.0109 | 1.341 (1.087–1.653) | 13.15 | 0.2837 |

| Epilepsy; convulsions | 579,755 | 0.2400 | 0.0295 | <0.0001 | 0.0003 | 0.0004 | 1.054 (1.012–1.037) | 18.43 | 0.0722 |

| Status epilepticus | 122,600 | 0.1300 | <0.0001 | 0.0027 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 1.074 (1.045–1.103) | 19.07 | 0.0598 |

| Myasthenia gravis | 25,365 | 0.3100 | <0.0001 | 0.0045 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 1.162 (1.093–1.234) | 12.78 | 0.3082 |

| Guillain-Barre syndrome | 23,005 | 0.0020 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 1.16 (1.089–1.236) | 11.28 | 0.4199 |

| Multiple sclerosis | 68,410 | 0.0020 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 1.12 (1.080–1.162) | 10.15 | 0.5173 |

| Optic neuritis | 7,415 | 0.2400 | 0.4356 | 0.1546 | 0.4765 | 0.4819 | 1.046 (1.000–1.169) | 4.85 | 0.9382 |

| Transverse myelitis | 8,480 | 0.3500 | 0.8828 | 0.8025 | 0.7074 | 0.7153 | 1.023 (1.000–1.135) | 10.48 | 0.4874 |

| Neuromyelitis optica | 4,905 | 0.1900 | 0.2805 | 0.1256 | 0.2899 | 0.2999 | 1.085 (1.000–1.244) | 15.84 | 0.1471 |

| Meningitis | 79,050 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 1.925 (1.853–2.000) | 29.38 | 0.002 |

| Encephalitis | 32,595 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 1.280 (1.213–1.351) | 19.92 | 0.0465 |

Obtained from sine curves fitted to monthly hospitalization frequencies (corresponding to the Edwards test).12, 13 The minimum peak-to-trough ratio is 1 (indicating an equal incidence of hospitalization during each month without seasonal variation), and higher values indicate greater degrees of seasonality.

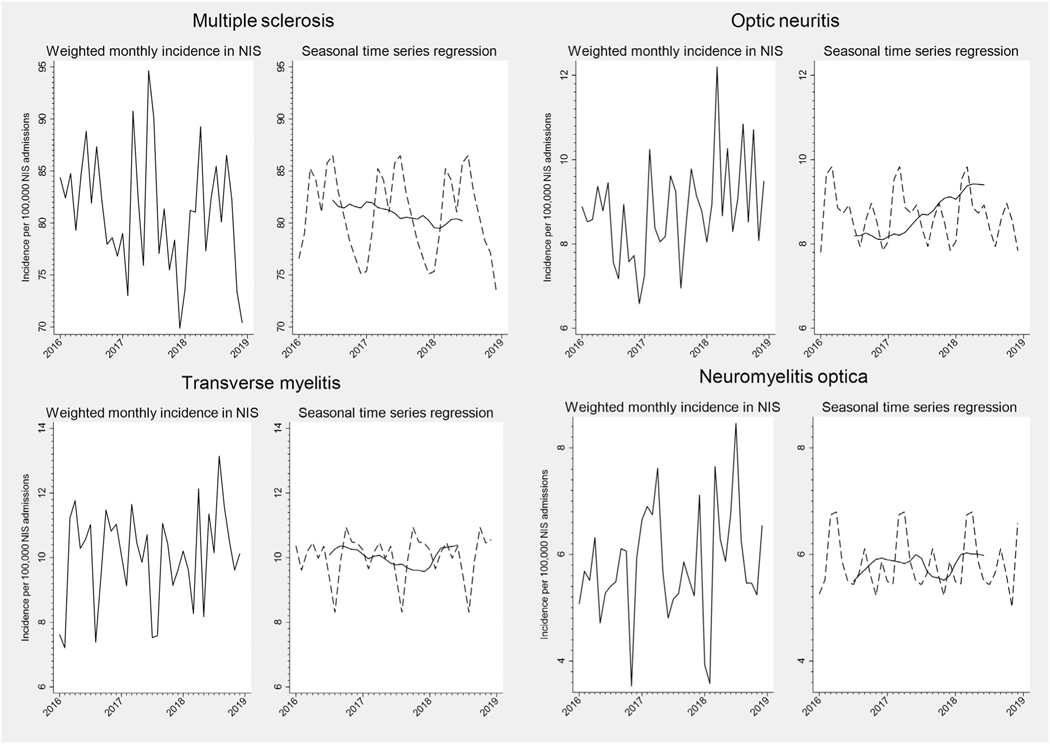

The trend and smoothed seasonal components of our seasonal time series regression models are shown in Figure 1 to 4, and the Kruskal-Wallis test of seasonality from these models is presented in Table. For several neurologic diseases, there were significant trends in hospitalization incidence over time. Underlying seasonal variation was obscured by these trends but became more apparent as the seasonal and trend components were separated. For example, monthly variation in the incidence of optic neuritis hospitalizations did not appear to follow a particular pattern in the unadjusted plot (Fig 3). However, seasonal time series regression revealed an increasing trend in hospitalizations for optic neuritis from 2016 to 2018. Removal of the overall trend revealed a seasonal pattern, with consistent peaks in late winter-early spring and nadirs in the fall. Hospitalizations for other neurologic conditions had less apparent seasonal patterns, even after accounting for long-term trends (e.g., cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, Fig 1). Despite clear seasonal patterns in both raw and decomposed time series data for many diseases, only meningitis achieved the Bonferroni-corrected threshold for statistical significance using the Kruskal-Wallis test (Table). Similar results were found when stratified by geographic region or examining 2012 to 2014 data (Supplemental Table S2).

FIGURE 3:

Monthly incidence and seasonal time series regression for neuroinflammatory hospital admissions, NIS 2016 to 2018. For seasonal time series regression models, the trend curve is plotted as a solid line, and the Hanning linear-smoothed seasonal component is represented with a dotted line.

Discussion

In this study, we examined seasonal patterns of hospitalization for 14 neurologic conditions across a wide range of disease pathologies, including some for which seasonality has not previously been established, using nationally representative data in the United States. We found that hospitalizations for virtually all major neurologic diseases exhibit significant seasonal variation. We also compared different statistical methods for assessing seasonality and found that seasonal time series regression has advantages over chi-squared and cyclicity tests in illustrating seasonal variation and trends but is limited by a lack of sensitivity for statistical testing. These findings have important implications for translational and environmental epidemiologic research, healthcare administration and preparedness, and future studies of seasonality in neurologic disease.

Previous studies have demonstrated seasonal variation in several neurologic diseases at a local or regional level. Viral meningitis and encephalitis are known to peak in the summer when transmission of enteroviruses and other pathogens is more common, and there is recent evidence that autoimmune encephalitis may also be more common during the summer, leading some to suspect an underlying infectious trigger.14, 15 While some studies have reported a peak in ischemic stroke and other atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases during the winter,2, 16 we found an increase in the late spring and summer, similar to a time series analysis of nationwide data from the Veterans Affairs health system.17 The mechanisms for this temporal pattern are not entirely clear, but seasonal variation in cholesterol, cogulation factors (e.g., fibrinogen), and pro-inflammatory cytokines as well as air pollution and respiratory infections have been identified.18 Intracerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhage have also been shown to peak during the winter, consistent with our findings, and this has been postulated to be due to seasonal fluctuation in blood pressure and physical activity.19, 20 The earliest studies of Guillain-Barre syndrome found an association with Campylobacter jejuni infections, which peak during the late spring and early summer,21 but consistent with prior studies,5 we observed a winter peak in GBS, suggesting that other seasonal respiratory infections and/or vaccinations are likely responsible for the majority of GBS cases. Demyelinating disease activity and severity are associated with a lack of vitamin D exposure,22 so one would expect an increase in incidence, exacerbation, or hospitalization during the winter when sunlight is decreased. However, consistent with prior studies, we found that hospitalizations for multiple sclerosis and optic neuritis were greater in the spring and summer compared to the winter.6 Influenza vaccination has been associated with a transiently lower risk of multiple sclerosis exacerbation, so it is possible that this is true of other demyelinating diseases such as optic neuritis and neuromyelitis optica.23 However, transverse myelitis had a later peak (late fall/winter) than other neuroinflammatory disorders, which may be due to cases of transverse myelitis associated with viral infections or vaccinations.24, 25

Despite a large and growing body of literature on seasonality in neurologic disease, direct comparisons between existing studies are challenging as they are conducted in different geographic areas using variable data sources and case ascertainment methods. By using a large, nationally representative database of inpatient hospitalizations in the United States, we are able to not only validate previous findings at a national level but also compare the relative magnitude of seasonal variation across different diseases. Seasonality in disease incidence or severity can lead to novel hypotheses about underlying mechanisms and risk factors but is also important for healthcare preparedness. Specifically, anticipated increases in neurologic hospitalizations should be met with adequate personnel and neuroimaging and electrodiagnostic resources.

We examined several neurologic conditions for which prior studies of seasonality are either conflicting or lacking. A few studies have suggested an increase in seizure-related emergency department visits or sudden unexplained death in epilepsy during the winter,26, 27 but these were limited to a single year of data. In contrast, we observed a greater incidence of epilepsy and status epilepticus hospitalizations during the spring and fall as compared to the winter. Seasonal variation in hospitalizations for cerebral venous sinus thrombosis has previously been examined in a single cohort in Isfahan, Iran, which, like our study, found a slight increase in incidence during the summer.28 To our knowledge, seasonal variation in myasthenia gravis has only been reported in a single electronic health records review study in New York City.29 Our study also found a summer peak in myasthenia gravis hospitalization (possibly due to heat-induced impairment in neuromuscular transmission30) and is the first to describe myasthenia gravis hospitalization in this manner on a national scale.

Our results also highlight major differences between statistical methods that can be used to measure seasonality. Chi-squared tests rely on grouping individual months into seasons and are simple and easy to understand. They detected large degrees of seasonal fluctuation for common diseases such as stroke, meningitis, and encephalitis, but failed to detect significant seasonal variation for rarer conditions, including some demyelinating diseases for which there was a priori evidence of seasonality, and are thus prone to limitations in sample size. The Edwards test detected seasonality in hospitalizations for neurological conditions missed by chi-square tests, and the results were robust to fluctuations in the number of days per month or the number of total hospitalizations, but the lack of data visualization ability made the temporal pattern and significance of the findings difficult to interpret. Seasonal time series regression was able to estimate and visualize trend and seasonal components separately, which provides information on long-term trends and permits a direct comparison of seasonality between different diseases. However, despite clear graphical evidence of seasonality for many conditions, statistical testing of seasonality was only significant for meningitis, suggesting a lack of sensitivity or power for seasonality testing within seasonal time series regression models. This observation serves as a warning against overrelying on p-values,31 and the distinction between statistical and clinical significance remains critically important.32

Limitations of our study include the use of ICD codes to identify neurologic hospitalizations, which were developed primarily for healthcare administration and billing purposes rather than for research. This is especially challenging for diagnoses with phenotypic overlap—for example, if a patient presents with optic neuritis and is ultimately diagnosed with neuromyelitis optica, it is unclear which of these would be recorded as the primary diagnosis in NIS. In some cases, we could not examine specific disease etiologies or subtypes of interest (e.g., infectious vs. autoimmune encephalitis) because the coding for these was too broad. Future research would be aided by the ability to distinguish between etiologies and subtypes at a large scale such as by developing predictive algorithms or using linked electronic health record data. NIS consists solely of inpatient data, so new diagnoses or mild exacerbations of chronic diseases that were managed on an outpatient basis (e.g., multiple sclerosis, myasthenia gravis) were not captured. Another limitation with regard to diseases with relapsing courses such as multiple sclerosis and myasthenia gravis is that it is impossible to distinguish between new diagnoses and hospitalizations for exacerbation of pre-existing disease in NIS. Finally, it is possible for multiple neurologic conditions to co-exist (e.g., status epilepticus secondary to encephalitis), but because identifying the primary reason for hospitalization requires limiting the analysis to a single diagnosis field, this may have led to the undercounting of some conditions. In spite of these limitations, we present national data on the seasonality of hospitalizations of common neurological conditions, which can be used to inform national healthcare and treatment capacity planning, as well as generate hypotheses and methodologic guidance for future research about regional, environmental, and other modifiable risk factors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Translational Center of Excellence for Neuroepidemiology and Neurology Outcomes Research at the University of Pennsylvania.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest

Nothing to report.

Data Availability Statement

NIS is publicly available for purchase through HCUP to qualified users.

References

- 1.Rau R. Seasonality in human mortality: a demographic approach. Berlin: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raj K, Bhatia R, Prasad K, et al. Seasonal differences and circadian variation in stroke occurrence and stroke subtypes. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2015;24:10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.George BP, Schneider EB, Venkatesan A. Encephalitis hospitalization rates and inpatient mortality in the United States, 2000–2010. PloS One 2014;9:e104169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paireau J, Chen A, Broutin H, et al. Seasonal dynamics of bacterial meningitis: a time-series analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4: e370–e377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Webb AJS, Brain SAE, Wood R, et al. Seasonal variation in Guillain-Barré syndrome: a systematic review, meta-analysis and Oxfordshire cohort study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015;86:1196–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin Y, de Pedro-Cuesta J, Söderström M, et al. Seasonal patterns in optic neuritis and multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. J Neurol Sci 2000;181:56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality R MD. HCUP National Inpatient Sample (NIS). Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). 2012. [Internet]. [date unknown];Available from: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamedani AG, Blank L, Thibault DP, Willis AW. Impact of ICD-9 to ICD-10 coding transition on prevalence trends in neurology. Neurol Clin Pract 2021;11:e612–e619. 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000001046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards JH. The recognition and estimation of cyclic trends. Ann Hum Genet 1961;25:83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walter SD, Elwood JM. A test for seasonality of events with a variable population at risk. Br J Prev Soc Med 1975;29:18–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pearce MS, Feltbower R. SEAST: Stata module to calculate tests for seasonality with a variable population at risk [Internet]. 2005;Available from: https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:boc:bocode:s450001 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skajaa N, Horváth-Puhó E, Sundbøll J, et al. Forty-year seasonality trends in occurrence of myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and hemorrhagic stroke. Epidemiol Camb Mass 2018;29:777–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rothman KJ, Bolce JD. Episheet: Spreadsheets for the Analysis of Epidemiologic Data [Internet]. 2021;[cited 2022 Nov 21 ] Available from: https://www.rtihs.org/episheet [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adang LA, Lynch DR, Panzer JA. Pediatric anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis is seasonal. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2014;1:921–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai Q-L, Cai M-T, Zheng Y, et al. Seasonal variation in autoimmune encephalitis: a multi-center retrospective study. J Neuroimmunol 2021;359:577673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagarajan V, Fonarow GC, Ju C, et al. Seasonal and circadian variations of acute myocardial infarction: findings from the get with the guidelines-coronary artery disease (GWTG-CAD) program. Am Heart J 2017;189:85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oberg AL, Ferguson JA, McIntyre LM, Horner RD. Incidence of stroke and season of the year: evidence of an association. Am J Epidemiol 2000;152:558–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turin TC, Kita Y, Murakami Y, et al. Higher stroke incidence in the spring season regardless of conventional risk factors: Takashima stroke registry, Japan, 1988–2001. Stroke 2008;39:745–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Steenhuijsen Piters WA, Algra A, van den Broek MF, et al. Seasonal and meteorological determinants of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol 2013; 260:614–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nyquist PA, Brown RD, Wiebers DO, et al. Circadian and seasonal occurrence of subarachnoid and intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology 2001;56:190–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Djennad A, Lo Iacono G, Sarran C, et al. Seasonality and the effects of weather on campylobacter infections. BMC Infect Dis 2019; 19:255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pierrot-Deseilligny C, Souberbielle J-C. Vitamin D and multiple sclerosis: an update. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2017;14:35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Keyser J, Zwanikken C, Boon M. Effects of influenza vaccination and influenza illness on exacerbations in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 1998;159:51–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeffery DR, Mandler RN, Davis LE. Transverse myelitis. Retrospective analysis of 33 cases, with differentiation of cases associated with multiple sclerosis and parainfectious events. Arch Neurol 1993;50: 532–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguyen S, Bastien E, Chretien B, et al. Transverse myelitis following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: a Pharmacoepidemiological study in the World Health Organization’s Database. Ann Neurol 2022;92:1080–1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brás PC, Barros A, Vaz S, et al. Influence of weather on seizure frequency—clinical experience in the emergency room of a tertiary hospital. Epilepsy Behav 2018;86:25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bell GS, Peacock JL, Sander JW. Seasonality as a risk factor for sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: a study in a large cohort. Epilepsia 2010;51:773–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salehi G, Sarraf P, Fatehi F. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis may follow a seasonal pattern. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2016;25:2838–2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melamed RD, Khiabanian H, Rabadan R. Data-driven discovery of seasonally linked diseases from an Electronic Health Records system. BMC Bioinformatics 2014;15:S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gutmann L. Heat-induced myasthenic crisis. Arch Neurol 1980;37: 671–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wasserstein RL, Lazar NA. The ASA statement on p-values: context, process, and purpose. Am Stat 2016;70:129–133. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khera R, Krumholz HM. With great power comes great responsibility: big data research from the National Inpatient Sample. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2017;10:e003846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

NIS is publicly available for purchase through HCUP to qualified users.