Abstract

Protein quality control pathways play important roles in resistance against pathogen infection. For example, the conserved transcription factor SKN-1/NRF up-regulates proteostasis capacity after blockade of the proteasome and also promotes resistance against bacterial infection in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. SKN-1/NRF has 3 isoforms, and the SKN-1A/NRF1 isoform, in particular, regulates proteasomal gene expression upon proteasome dysfunction as part of a conserved bounce-back response. We report here that, in contrast to the previously reported role of SKN-1 in promoting resistance against bacterial infection, loss-of-function mutants in skn-1a and its activating enzymes ddi-1 and png-1 show constitutive expression of immune response programs against natural eukaryotic pathogens of C. elegans. These programs are the oomycete recognition response (ORR), which promotes resistance against oomycetes that infect through the epidermis, and the intracellular pathogen response (IPR), which promotes resistance against intestine-infecting microsporidia. Consequently, skn-1a mutants show increased resistance to both oomycete and microsporidia infections. We also report that almost all ORR/IPR genes induced in common between these programs are regulated by the proteasome and interestingly, specific ORR/IPR genes can be induced in distinct tissues depending on the exact trigger. Furthermore, we show that increasing proteasome function significantly reduces oomycete-mediated induction of multiple ORR markers. Altogether, our findings demonstrate that proteasome regulation keeps innate immune responses in check in a tissue-specific manner against natural eukaryotic pathogens of the C. elegans epidermis and intestine.

Protein quality control pathways play important roles in resistance against pathogen infection. This study shows that proteasome regulation keeps innate immune responses in check in a tissue-specific manner, against natural eukaryotic pathogens of the C. elegans epidermis and intestine.

Introduction

The evolutionary history of Caenorhabditis elegans is shaped by various biotic interactions in its natural habitat [1]. These interactions include beneficial and pathogenic microbes, which trigger a diverse set of responses in C. elegans [1]. Studying C. elegans under some conditions encountered in its natural environment can provide novel insights, such as new functions for genes lacking functional annotation in the genome [1]. For example, the identification of oomycetes as natural pathogens of C. elegans revealed a previously uncharacterized family of chitinase-like (chil) genes as immune response effectors, which can modify cuticle properties to prevent oomycete attachment and consequently infection [2]. Most chil genes are not expressed in lab culture conditions and can only be induced upon pathogen recognition together with a broader subset of genes previously described as the oomycete recognition response (ORR) [3]. C. elegans can similarly mount specific responses against other natural pathogens as well, for example, the intracellular pathogen response (IPR) against microsporidia and the Orsay virus [4,5].

While the nematode is likely to use its sensory capabilities to detect pathogens and activate pathogen-specific responses [6], it also uses surveillance immunity as a broad way to tackle pathogenic attacks [7]. Pathogens can hijack the host cellular machinery to support their growth and development, and in doing so, they may disrupt core cellular processes, such as transcription, translation, protein turnover, and mitochondrial respiration. As a result, disruption to these processes can be sensed as a pathogenic attack leading to activation of immune responses [8–10]. For example, inhibition of translation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin A leads to activation of immune response genes through transcription factors such as ZIP-2 and CEBP-2 [8,9,11]. Disruption of mitochondrial proteostasis by P. aeruginosa also induces immune responses [12,13]. Similarly, RNAi and microbial toxin perturbation of various core cellular processes induces detoxification enzymes and aversion behavior in C. elegans [10]. Likewise, the IPR can be induced either by inhibition of the purine salvage pathway as seen in pnp-1 mutants [14,15] or by blockade of the major protein degradation machinery in the cell, the proteasome [4,16].

A major player regulating proteostasis upon proteasome blockade is the conserved transcription factor SKN-1/NRF [17,18]. One of its isoforms, SKN-1A (NRF1/NFE2L1 in humans), is normally localized in the endoplasmic reticulum membrane where it is glycosylated and then targeted for proteasomal degradation (Fig 1A) [19]. However, upon proteasome blockade, the glycosylated isoform escapes degradation and is edited by PNG-1 (NGLY1 in humans), a conserved N-glycanase that converts the N-glycosylated asparagine residues to aspartic acid, and the edited protein then translocates to the nucleus [19]. Inside the nucleus, DDI-1 (DDI2 in humans), a conserved aspartic protease, cleaves the N-terminal region of the protein, and this processed SKN-1A is now activated to up-regulate expression of proteasomal subunits to increase proteostasis capacity in a bounce-back response (Fig 1A) [19–21]. In addition to its role in promoting proteostasis capacity, SKN-1 is also required to respond to oxidative stress [22] and promotes resistance to bacterial pathogens, such as the human pathogens P. aeruginosa and Enterococcus faecalis [23–25].

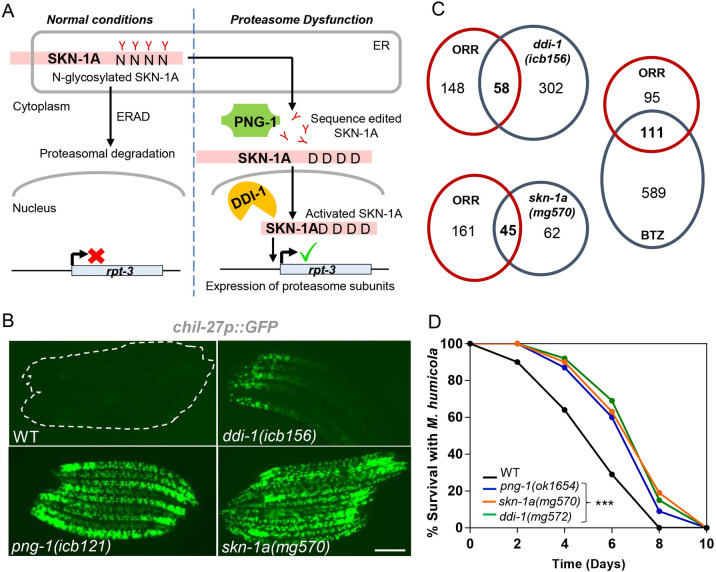

Fig 1. Proteasome impairment activates ORR in C. elegans.

(A) Schematic showing the proteasome surveillance pathway and the stepwise activation of SKN-1A for transcription of proteasomal subunits. (B) L4 stage C. elegans showing constitutive chil-27p::GFP expression in ddi-1(icb156), png-1(icb121), and skn-1a(mg570) mutant animals. Note that skn-1a and png-1 show a stronger, full body activation of the chil-27p::GFP marker in comparison to ddi-1 mutants, which might reflect the fact that png-1 and skn-1a are essential components of the proteasome surveillance pathway, while ddi-1 has been shown to be dispensable [19]. Scale bar is 100 μm. (C) Venn comparisons showing significant overlap between up-regulated genes in the transcriptome of ddi-1(icb156) and skn-1a(mg570) mutant, and BTZ-treated animals with ORR (RF 13.8, p < 6.171e-50 for comparison with ddi-1; RF 13.6, p < 5.518e-101 for comparison with BTZ and RF 36.0, p < 1.249e-59 value for comparison with skn-1a). (D) ddi-1(mg572), png-1(ok1654), and skn-1a(mg570) mutant animals exhibit reduced susceptibility to infection by M. humicola as compared to WT C. elegans (n = 60 per condition, performed in triplicates, p < 0.001 based on log-rank test, a representative graph for one of the 3 replicates is shown). The numerical data for all 3 replicates is available in Supporting information S1 Data. BTZ, bortezomib; ORR, oomycete recognition response.

Here, we show that, in contrast to previous studies demonstrating a protective role for SKN-1 in promoting resistance against bacterial pathogens, mutants in the SKN-1A-driven proteasome surveillance pathway result in constitutive expression of ORR and IPR and consequently exhibit resistance against infection by oomycetes and microsporidia. Rescue of skn-1a specifically in the epidermis or the intestine was sufficient to restore wild-type levels of infection by oomycetes and microsporidia, respectively. Moreover, we report that the ORR/IPR genes induced in common in these programs, are also regulated through the proteasome and can be induced in distinct tissues depending on the exact trigger. Notably, we show that by increasing proteasome function, there is a partial inhibition of oomycete-mediated induction of ORR markers, suggesting that the response to pathogens may directly involve stabilization of factors normally degraded by the proteasome. Therefore, our findings, together with other studies in flies and mammals [26–29], highlight how proteasome regulation keeps a range of innate immune responses in check in a tissue-specific manner.

Results

Mutants in the proteasome surveillance pathway show constitutive activation of the ORR

We performed a chemical mutagenesis screen on animals carrying the chil-27p::GFP reporter, which is not expressed in wild-type animals under standard growth conditions, but is strongly induced upon recognition of oomycete pathogens [2,30]. We obtained several independent mutants with constitutive epidermal expression of chil-27p::GFP, either in a graded manner with maximum GFP expression in the head region as previously reported [2], or strong expression throughout the body in late larval stages and early adults (Fig 1B). Three mutations were mapped to ddi-1 and png-1, 2 genes known to play a role in the proteasome surveillance pathway by regulating SKN-1A [18,19] (Figs 1A and S1A). To determine if the non-synonymous ddi-1(icb156) mutation isolated from the screen represented a gain or loss-of-function allele, we tested existing strong loss-of-function ddi-1 mutants carrying either a deletion within the gene (mg571) or a mutation in the active site of the protein (mg572) [18]. In both cases, we found similar chil-27p::GFP induction (S1B Fig), confirming that ddi-1(icb156) represents a loss-of-function allele. Similarly, the recovery of a frameshift and a nonsense mutation in png-1 suggested that constitutive chil-27p::GFP expression is likely attributed to loss-of-function of the gene, which was further confirmed using the independently derived png-1(ok1654) deletion allele [31] (S1B Fig).

As PNG-1 and DDI-1 are required to activate SKN-1A, we analyzed chil-27p::GFP expression upon loss-of-function of skn-1a. Here, we found constitutive expression throughout the body of the animal (Fig 1B). The response was also recapitulated by skn-1 RNAi (S1B Fig), which is known to affect both skn-1a and skn-1c isoforms as the entire skn-1c sequence is shared by skn-1a (S2A Fig). Because PNG-1 is required specifically for activation of the SKN-1A isoform and SKN-1C does not undergo sequence editing [19], the involvement of SKN-1C in activating chil-27p::GFP seemed unlikely. However, to test this possibility, we performed wdr-23 RNAi on skn-1a(mg570) mutant animals. WDR-23 is a WD40 protein known to specifically suppress SKN-1C function, inhibition which is released, for example, under oxidative stress to allow SKN-1C activation [32,33]. We found that wdr-23 RNAi did not suppress chil-27p::GFP induction in skn-1a(mg570) mutants, while it activated a gst-4p::tdTomato reporter in wild type as expected (S2B Fig). Furthermore, we treated skn-1a(mg570) animals with skn-1 RNAi to address the possibility of skn-1c isoform contributing to chil-27p::GFP induction in the absence of skn-1a. However, skn-1 RNAi did not have any effect on the expression of chil-27p::GFP in skn-1a mutants (S2B Fig). Altogether, these results suggest that the skn-1c isoform does not regulate expression of chil-27p::GFP, which is induced specifically by the loss of the skn-1a isoform.

Mutants in skn-1a have reduced proteasome subunit gene expression and, as a result, experience proteasome dysfunction [34]. Reduced proteasomal subunit gene expression may affect the induction of immune programs through non-proteolytic roles that have recently been ascribed to proteasomal subunits. If this were the case, then induction would not be affected by proteasome impairment via bortezomib (BTZ) drug treatment [35]. To determine if impairment of proteasome function can induce the ORR, we performed RNAseq analysis of ddi-1(icb156) mutants versus wild-type controls and compared the set of up-regulated genes with those previously reported for inhibition of proteasomal activity by BTZ drug treatment [36], oomycete recognition response [3], and skn-1a loss-of-function [36]. A significant overlap was identified between all these datasets (Figs 1C and S1C, and S1 Table). Wild-type animals treated with high dose of BTZ show induction of chil-27 as previously described [16], and this induction is rapid at the chil-27 mRNA level within 15 min post exposure to the drug as opposed to 1 h required upon exposure to oomycete extract (S3A and S3B Fig), which further suggested a link between the induction of ORR and proteasome dysfunction. The physiological consequence of activated ORR was revealed by an infection assay where ddi-1(mg572), png-1(ok1654), and skn-1a(mg570) mutants showed enhanced survival in the presence of the oomycete pathogen Myzocytiopsis humicola (Fig 1D). The enhanced survival phenotype was recapitulated both by skn-1 RNAi treated WT or skn-1a(mg570) animals (S2C Fig), as well as BTZ-treated animals (S3C Fig). These findings are consistent with ORR induction in skn-1a mutants being protective against oomycete infection and associated with loss of proteasomal activity, as opposed to reduced proteasomal gene expression having an impact independent of proteasomal activity.

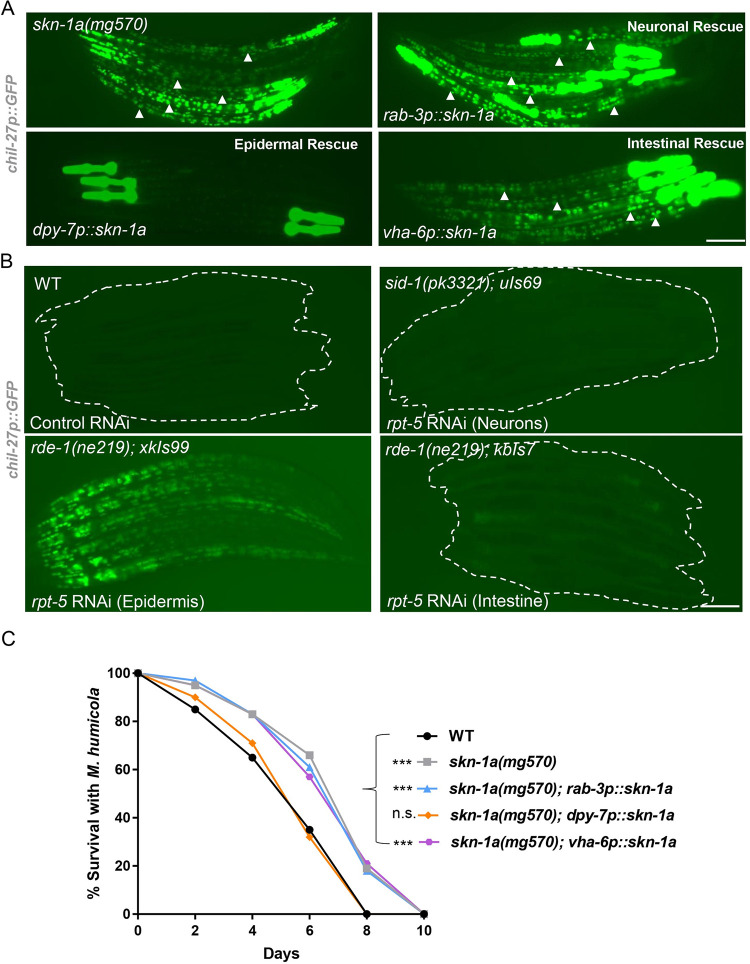

Proteasome impairment in the epidermis is sufficient to induce the ORR

Induction of the ORR requires cross-tissue communication with chemosensory neurons likely sensing the pathogen and signaling to the epidermis where induction of chil genes takes place to combat the infection [3]. Having discovered that proteasome inhibition can activate the ORR, we wanted to determine whether this inhibition is required in a tissue-specific manner or not. To address this question, we performed tissue-specific rescue of skn-1a(mg570) mutants by expressing skn-1a under a rab-3p (pan-neuronal), dpy-7p (epidermal), or vha-6p (intestinal) promoter. We found that only the epidermal rescue of skn-1a repressed expression of chil-27p::GFP (Fig 2A). We further investigated this question by performing tissue-specific RNAi of the proteasomal subunit rpt-5 [10,37,38], where we found that only epidermal RNAi of rpt-5 was able to induce chil-27p::GFP expression (Fig 2B). We also tested the survival of tissue-specific rescued lines of skn-1a in the presence of M. humicola and found only epidermal overexpression of skn-1a to rescue the enhanced oomycete resistance phenotype (Fig 2C). These findings demonstrate that proteasome impairment, or rescue of proteasome surveillance function specifically in the epidermis, regulates the ORR and oomycete resistance.

Fig 2. Proteasome impairment in the epidermis is sufficient to activate the ORR.

(A) Epidermal (dpy-7p), neuronal (rab-3p), and intestinal (vha-6p) rescue of skn-1a function in skn-1a(mg570). Note loss of GFP puncta in the body (shown by arrowheads) corresponding to chil-27p::GFP expression specifically upon epidermal rescue (3 independent transgenic lines analyzed, representative image shown). In all cases, myo-2p::GFP has been used as a co-injection marker that labels the pharynx. (B) Tissue-specific proteasome dysfunction induced by epidermal-specific, intestine-specific, and neuronal-enhanced RNAi of rpt-5 (n > 50 per condition, performed in triplicates, representative image shown). Scale bars in A and B are 100 μm. (C) Survival analysis of skn-1a(mg570) mutants with skn-1a function rescued in neurons (rab-3p::skn-1a), epidermis (dpy-7p::skn-1a), and intestine (vha-6p::skn-1a) (n = 60 per condition, performed in triplicates, p < 0.001 based on log-rank test, a representative graph for one of the 3 replicates is shown). The numerical data for all 3 replicates is available in Supporting information S1 Data. ORR, oomycete recognition response.

Previous work has led to the identification of other epidermal regulators of ORR, namely, the receptor tyrosine kinase OLD-1 [39] that is specific to oomycete recognition, and the PALS-22/PALS-25 antagonistic paralogs [16,30], which regulate the immune response against both oomycetes and microsporidia. We thus asked whether activation of ORR upon proteasome dysfunction requires old-1 or pals-25. Here, we performed skn-1 RNAi on animals carrying a deletion in old-1 or pals-25, along with wild-type animals as control, and found no difference in chil-27p::GFP induction (S4 Fig). These results suggest that epidermal proteasome dysfunction acts either downstream of OLD-1 and PALS-25-mediated signaling, or as a parallel trigger leading to the activation of ORR.

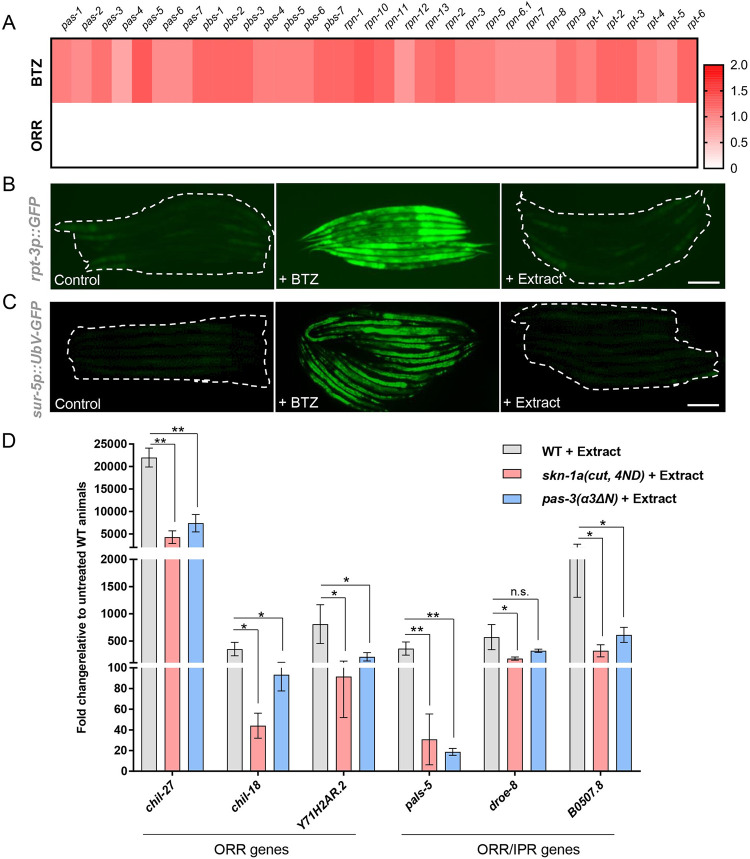

Oomycete extract exposure does not cause broad proteasome dysfunction

Since epidermal proteasome dysfunction triggers the ORR, we tested whether impairment of proteasome function occurs upon exposure to oomycete extract. Proteasomal subunit expression is observed as a bounce-back response upon proteasome dysfunction [20]. Even though significant overlap was obtained between ORR, and genes up-regulated upon proteasome dysfunction (Fig 1D), none of the proteasomal components were found to be induced as a part of the ORR (Fig 3A). For example, the induction of the rpt-3p::GFP reporter [18] was only observed upon BTZ treatment, but not upon treatment with oomycete extract (Fig 3B). Similarly, we did not see accumulation of ubiquitylated substrates reported by a sur-5p::UbV-GFP marker [40] upon extract exposure, while we did observe induction of the marker upon inhibition of proteasome activity by BTZ treatment (Fig 3C). These results suggest that oomycete extract exposure is unlikely to cause broad proteasome dysfunction in C. elegans.

Fig 3. Oomycete extract exposure does not cause broad proteasome dysfunction, and activation of the proteasome partially inhibits induction of ORR genes by oomycete extract.

(A) Heat map showing log2 fold change in the expression of proteasome components upon treatment with oomycete extract as opposed to BTZ treatment. None of these genes are induced as part of the ORR and are shown in white. The numerical data for the heat map is available in Supporting information S1 Data. (B) Induction of rpt-3p::GFP is observed upon BTZ treatment, but not upon extract treatment (n > 50, performed in triplicates, representative image shown). (C) Induction of sur-5p::UbV-GFP is observed upon BTZ treatment, but not upon extract treatment (n > 50, performed in triplicates, representative image shown). Scale bar in panels B and C is 100 μm. (D) RT-qPCR showing reduced induction of genes specific to ORR or genes in the overlap between ORR and IPR upon extract treatment in animals with constitutive expression of the activated form of SKN-1A [skn-1a(cut, 4ND) in skn-1a(mg570)] or constitutive activation of the proteasome [pas-3(α3ΔN)] (**p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001 based on unpaired t test in comparison to extract-treated wild type). The numerical data for all 3 replicates is available in Supporting information S1 Data. BTZ, bortezomib; IPR, intracellular pathogen response; ORR, oomycete recognition response.

To test the potential direct involvement of proteasomal regulation for activation of the ORR upon oomycete exposure, animals constitutively expressing proteasomal subunits through a constitutively activated SKN-1A [skn-1a(cut, 4ND)] [19] or animals having a hyperactive proteasome (pas-3(α3ΔN) [41] were treated with extract and expression of multiple ORR genes was analyzed by RT-qPCR. We found partial but significant reduction in the expression of analyzed ORR genes upon extract treatment in both cases (Fig 3D). It must be noted that none of these genes have detectable expression in the absence of extract, and their levels of expression in skn-1a(mg570) mutants are significantly lower compared to extract-exposed wild-type animals (S5 Fig). These results suggest that pathogen-mediated induction of the ORR epidermal signaling pathway may partly require stabilization of a factor constitutively degraded by the proteasome under uninfected conditions.

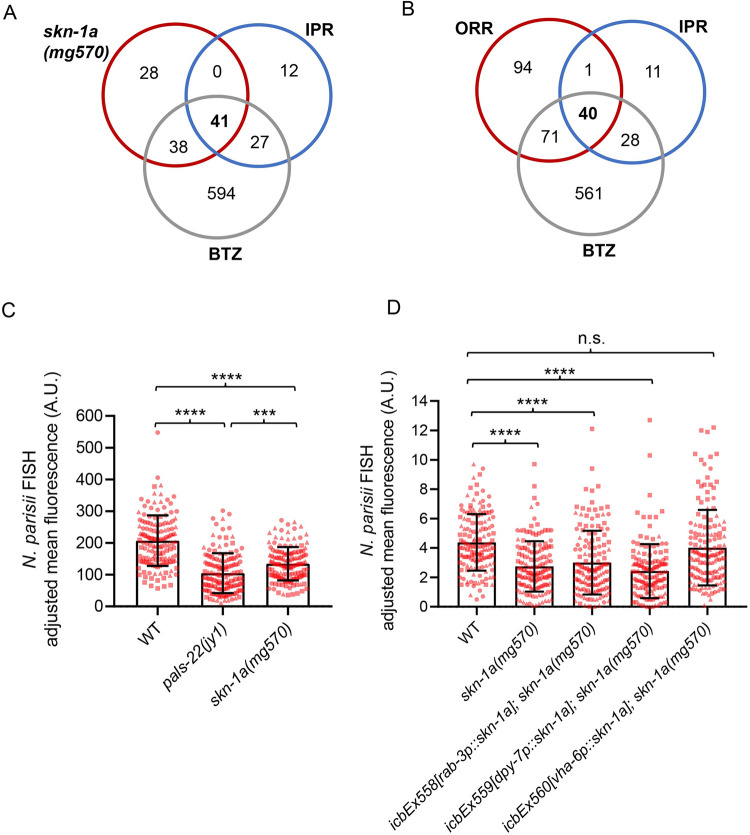

Impairment of the SKN-1A bounce-back response also leads to activation of resistance against intracellular intestinal pathogens

It is known that proteasome blockade by BTZ treatment can activate the IPR in C. elegans [16], which is the protective transcriptional program against intracellular intestinal pathogens like Nematocida parisii and the Orsay virus [4,5]. To determine if mutants in the proteasome surveillance pathway also show constitutive activation of the IPR, we compared RNAseq datasets generated for skn-1a mutants and BTZ-treated animals with the IPR gene list. We found significant overlap between IPR and up-regulated genes in skn-1a mutants (Fig 4A and 4B and S1 Table). To investigate whether loss of skn-1a also leads to increased resistance against intestinal pathogens, we assayed the skn-1a(mg570) mutant for resistance against the intestinal pathogen N. parisii. Here, we found that skn-1a(mg570) mutants had increased resistance to N. parisii (Fig 4C), which was rescued in this case specifically by intestinal (vha-6p) expression of skn-1a (Fig 4D). These results demonstrate that impairment of the SKN-1A proteasome surveillance pathway also induces resistance to intracellular pathogens of the intestine, and this impairment can be rescued specifically by SKN-1A function in the intestine.

Fig 4. Proteasome impairment in the intestine leads to activation of the IPR.

(A) Venn diagram showing significant overlap of IPR with up-regulated genes in skn-1a mutants (RF 84.4, p < 1.790e-72) and IPR with BTZ-treated animals (RF 21.4, p < 8.653e-84). (B) Venn diagram showing that overlap between ORR and IPR involves genes induced upon BTZ treatment. (C) skn-1a(mg570) mutants display increased resistance to N. parisii at 30 hpi relative to WT animals when infected at young adult. The pals-22(jy1) mutant was used as a positive control for its known increased resistance to N. parisii. (D) Intestinal rescue of skn-1a, but not epidermal or neuronal rescue, restores the resistance of skn-1a(mg570) mutants to N. parisii infection to WT levels. Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test was used for statistical analysis (**** p < 0.0001, *** p < 0.001. n = 150 animals per genotype). The numerical data for all 3 replicates of panels C and D is available in Supporting information S1 Data. BTZ, bortezomib; IPR, intracellular pathogen response; ORR, oomycete recognition response.

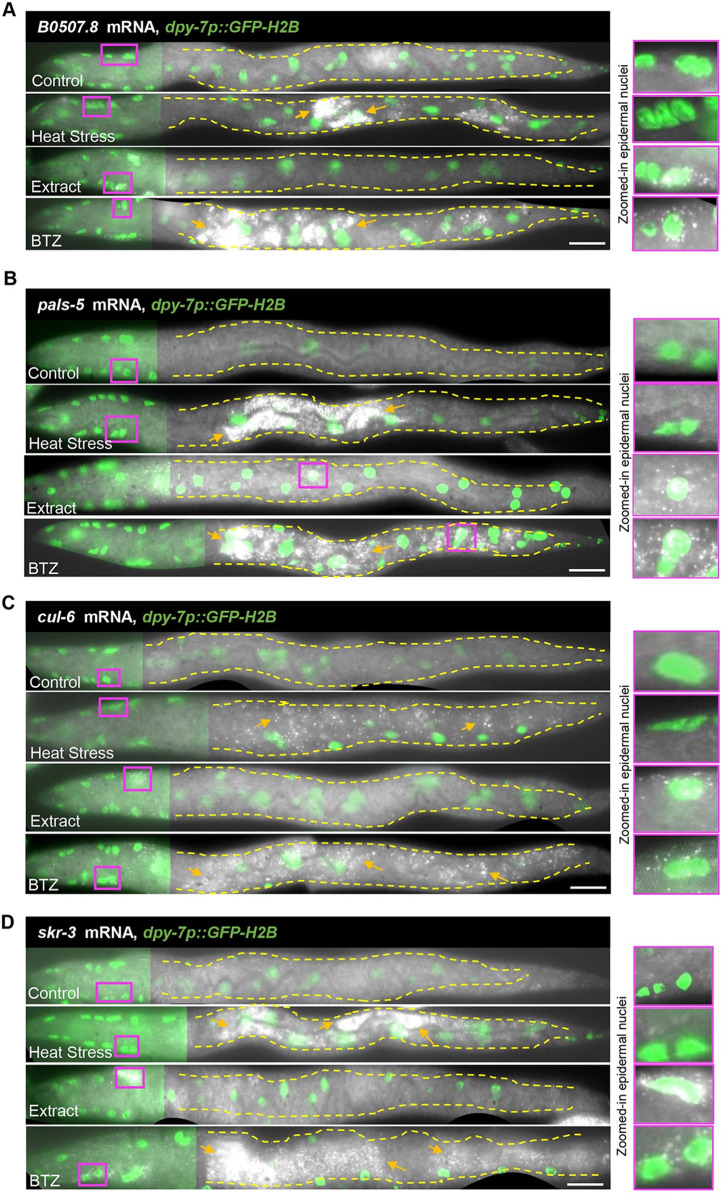

We have previously reported that approximately half of the IPR genes are also present in the ORR list [3], which was rather surprising given the distinct infection strategies and tissue tropism between oomycetes and intestinal-infecting microsporidia [42]. We hypothesized that the IPR and ORR programs might share significant overlap because they both involve regulation by the proteasome. Remarkably, we observed that almost all common ORR and IPR genes (40 out of 41 genes) were also regulated by BTZ treatment (Fig 4B and S1 Table). We reasoned that these shared immune response genes may be induced in different tissues following an ORR or IPR trigger. To test this possibility, we made use of single molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH) to determine in which tissue selected genes present in the overlap between ORR and IPR are induced, namely, pals-5, B0507.8, skr-3, and cul-6. Animals carrying GFP-labeled epidermal nuclei (dpy-7p::GFP-H2B) were treated with oomycete extract to activate the ORR and with prolonged heat stress (24 h at 30°C) [5] to induce the IPR. These 2 triggers were chosen in lieu of active infections because they induce responses in a more consistent manner across a population. Treatment with BTZ was performed to simultaneously activate both ORR and IPR. Consistent with our initial hypothesis, we found that all genes were induced specifically in the epidermis upon activation of ORR and in the intestine upon activation of IPR, while BTZ treatment led to induction in both tissues (Figs 5 and S6).

Fig 5. Common ORR and IPR genes can be induced in a tissue-specific manner.

Sections of straightened L2 stage animals showing mRNA distribution of some common ORR and IPR genes, namely, B0507.8 (A), pals-5 (B), cul-6 (C), and skr-3 (D) by smFISH upon 4 h extract treatment (ORR), prolonged heat stress at 30°C for 24 h (IPR) and 2 h of BTZ treatment (proteasome dysfunction). Epidermal nuclei are labeled in green with the dpy-7p::GFP-H2B marker. Co-localization of mRNA with green nuclei indicates epidermal expression as shown in zoomed-in panels (shown in magenta). Dashed yellow lines outline the intestine and orange arrows point to smFISH signal. Images are presented so that epidermal nuclei in the head region are in focus. The intensity of the GFP signal from out of focus epidermal nuclei in the posterior part of the body is reduced to highlight the signal in the intestine. Scale bar is 10 μm. See S6 Fig for quantification. BTZ, bortezomib; IPR, intracellular pathogen response; ORR, oomycete recognition response; smFISH, single molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization.

Previous studies have linked skn-1 to immunity against bacterial infection with skn-1 loss-of-function mutants reported as being hypersusceptible to bacterial infection [23–25]. However, previous studies were performed with RNAi or mutants that affect multiple isoforms of skn-1, and so it has not been clear whether skn-1a specifically is involved in bacterial immunity. We investigated this question by examining skn-1a(mg570) animals for increased susceptibility to P. aeruginosa (PA14) infection [43]. In this assay, pals-22(icb89) mutants and skn-1 RNAi-treated animals were used as positive controls, as both have been shown to result in enhanced susceptibility towards PA14 infection [16,24]. The susceptibility of skn-1a(mg570) animals to PA14 was found to be comparable to wild-type animals, while both skn-1 RNAi and pals-22 mutants showed increased susceptibility as expected (S7 Fig). The fact that skn-1 RNAi targets both a and c isoforms, but skn-1a(mg570) animals are not hypersusceptible to PA14 suggests that the requirement of SKN-1 to combat PA14 infection is either associated with the function of SKN-1C or both isoforms have redundant roles in this case. Taken together, these results suggest that different skn-1 isoform perturbations could lead to different host immunity outcomes in a pathogen-specific way.

Discussion

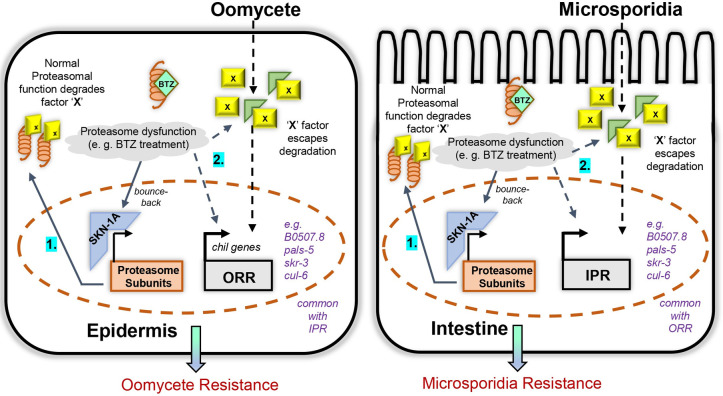

We demonstrate in this study that mutations in the SKN-1A proteasome surveillance pathway in C. elegans activate the ORR and IPR immune responses employed against distinct natural pathogens that infect through the epidermis or colonize the intestine. Our previous work indicated that blockade of the proteasome leads to induction of IPR genes, which are distinct from SKN-1-regulated genes [4,16], but the connection between the SKN-1-regulated pathway and the ORR/IPR was not clear. Here, we show that both loss of SKN-1A, an ER-localized transcription factor, and impairment of proteasome function induce the genes in common to both ORR and IPR. Furthermore, increasing proteasome function through constitutive proteasomal subunit gene expression or hyperactivity of the proteasome partially inhibits oomycete extract-mediated induction of ORR signature genes. Taken together, we hypothesize that some proteasomally regulated factor(s) normally keep the ORR and IPR immune responses in check in the absence of infection, and upon exposure to specific pathogens such factors can be stabilized in the associated tissue triggering the rapid induction of the respective immune programs (Fig 6). A similar phenomenon has been shown to regulate activation of NF-κB in Drosophila, where IMD is proteasomally degraded owing to permanent presence of UbK48 linkages, which are lost upon bacterial infection thereby stabilizing the protein and activating the pathway [26,27]. Likewise, Uba1-mediated proteasomal degradation of IRF3 in Zebrafish keeps activation of IFN signaling and activation of anti-viral immune response in check [44]. While our findings are consistent with a potential direct role for the proteasome in stabilizing factors that may be necessary for ORR/IPR induction, we cannot rule out that the bounce-back response pathway may also act in parallel. Given that the activation of the chil-27p::GFP marker is observed only in late larval stages in skn-1a mutants or with high doses of BTZ in wild-type animals, we speculate that the extent of proteasome dysfunction may determine the level of activation of the immune response programs. Furthermore, SKN-1A has been recently shown to be involved in lipid homeostasis so it is likely to also influence host immunity in more complex ways and beyond its role in the regulation of proteasome function [45].

Fig 6. Model based on the findings of this study.

The model highlights the interplay of SKN-1A-mediated proteasomal gene expression and activation of ORR and IPR in the epidermis and the intestine, respectively. 1. Under normal conditions, proteasomal degradation of unknown positive regulators (denoted as X factor) keeps activation of immune responses in check. 2. When proteasome dysfunction happens either by BTZ treatment or loss-of-function of skn-1a, X-factor escapes degradation and activates ORR and IPR in the epidermis and the intestine. Simultaneously, BTZ-mediated inhibition increases proteasomal gene expression as a bounce-back response. Such X factors could be directly involved in the tissue-specific signaling pathway activated upon oomycete or microsporidia exposure, respectively, in the epidermis and the intestine. Alternatively, they could regulate ORR and IPR gene induction in parallel to the pathogen-induced signaling pathway. BTZ, bortezomib; IPR, intracellular pathogen response; ORR, oomycete recognition response.

Unwanted activation of immune responses is often accompanied by trade-offs emphasizing the importance of keeping them in check [46]. For example, in pals-22 loss-of-function mutants, constitutive activation of ORR/IPR provides them protection from oomycetes and microsporidia [3]. However, pals-22 mutants also exhibit slow development, reduced lifespan, and increased pathogen load upon exposure to P. aeruginosa [16]. Likewise, pals-17 loss-of-function mutants exhibit constitutive activation of IPR and immunity to intracellular pathogens, but impaired development and reproduction [47]. While skn-1a(mg570) mutants develop normally like wild-type C. elegans, they too exhibit increased age-associated protein aggregation and consequently have a reduced lifespan [34], so similar trade-offs may also come into play in this case and involve proteotoxicity-driven defects that may exacerbate upon stressful conditions. Likewise, human patients with proteasome-associated autoinflammatory syndromes (PRAAS) show hyperactivation of IFN signaling, but often suffer with severe neurodevelopmental anomalies and skeletal defects [28,29,48].

Our study also highlights the importance of isoform-specific functions for skn-1. While skn-1b is neuronally expressed and regulates satiety and metabolic homeostasis [49], skn-1a and skn-1c are likely to have distinct immunomodulatory functions acting in a pathogen-specific way. Previous studies that reported a requirement of skn-1 for bacterial resistance used either skn-1 RNAi or skn-1 mutant alleles that affected both a and c isoforms [24,25]. However, we now show that skn-1a mutants show enhanced resistance to infection by eukaryotic natural pathogens and do not show enhanced susceptibility to PA14, which suggests that bacterial immunity is likely to be driven by SKN-1C or that SKN-1A/C isoforms might have redundant roles in this case. This result also aligns with the fact that just like NRF2 in humans, SKN-1C regulates response to oxidative stress in C. elegans [22], and bacterial pathogens have been shown to trigger ROS production in the host [23].

While proteasome-mediated suppression of inflammatory/immune responses might be an evolutionarily conserved phenomenon, the exact mechanisms of how immune responses are kept in check are likely to differ. For example, activation of type-I interferon signaling in mammals as a consequence of proteasome dysfunction has been attributed to ER stress and activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR) [28,50,51]. This is unlikely to be the case in the context of oomycete recognition as we have previously shown that introducing ER stress does not induce chil-27p::GFP [2]. Similarly, markers of proteotoxic stress are not induced as a part of the ORR/IPR programs, which makes them distinct from other stress-induced responses. Whether proteasomal regulation of the same factors keeps immune responses in check in the C. elegans epidermis and intestine is currently unknown. In the epidermis, the receptor tyrosine kinase OLD-1 is fully required for mounting the ORR and is likely regulated by the proteasome [39]; however, old-1 knockouts are still able to mount the ORR upon skn-1a perturbation ruling out OLD-1 as the main driving factor. In the intestine, ZIP-1 is a plausible candidate because it is degraded by the proteasome under basal conditions and has been shown to be required for induction of a subset of IPR genes [52]. Future work will elucidate the exact proteasomally regulated triggers of ORR/IPR and address whether these are shared or not between different tissues in C. elegans.

Materials and methods

C. elegans strains and pathogen maintenance

C. elegans strains were cultured on NGM plates seeded with E. coli OP50 at 20°C under standard conditions as previously described [53]. The list of all the strains used in this study is provided in S2 Table. We refer to skn-1(mg570) mutants throughout the manuscript as skn-1a(mg570) to stress that only isoform a is affected. Both M. humicola and N. parisii were maintained as described previously [2,42].

EMS mutagenesis

L4 stage WT animals carrying the chil-27p::GFP reporter (icbIs4) were mutagenized with 24 mM ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) (Sigma) in 4 ml M9, for 4 h with intermittent mixing by inversion. Worm pellets were then washed 10 times with 15 ml M9 to completely get rid of EMS from the suspension and worms were plated onto 90 mm NGM plate seeded with E. coli OP50. After 24 h, 300 adults were randomly picked and divided into thirty 90 mm plates carrying 10 animals in each. After 72 h at 20°C, all F1 gravid adults in each plate were individually bleached and respective pool of F2 embryos were collected onto new plates. Around 60,000 haploid genomes were screened to identify animals showing constitutive activation of chil-27p::GFP. The causative mutations were mapped to ddi-1 and png-1 by crossing to the highly polymorphic CB4856 strain, and 15–25 F2 recombinants were pooled in equal proportion to obtain genomic DNA for whole-genome sequencing of each independent mutant, performed by BGI (Hong Kong). WGS data was analyzed using the CloudMap Hawaiian variant mapping pipeline to identify causative mutations [54].

Oomycete M. humicola infection assays

Five M. humicola infected (dead) animals were added to the lawn of E. coli OP50 on 3 NGM plates and 20 live L4 animals for each genotype were transferred individually to each plate (n = 60 per condition per repeat). Dead animals with visible sporangia were scored every 48 h and live animals were transferred to a new NGM plate with 6 M. humicola infected (dead) animals. Dead animals without evidence of infection or animals missing from the plate were censored. Infection assays were performed in triplicates at 20°C on 30 mm NGM plates seeded with 100 μl E. coli OP50. For infection assays upon skn-1 RNAi, embryos were collected by bleaching gravid adults and were grown on E. coli HT115 (control RNAi) or skn-1 RNAi bacteria until the adult stage, which were then used to perform infection assay as described above. Similarly, embryos from WT animals were grown on E. coli OP50 until early L4 stage and then were transferred to OP50 plates with 20 μm of BTZ (Sigma) or DMSO (Thermo Scientific) (control, <0.1%) for 24 h before using them for infection assay.

P. aeruginosa PA14 infection assays

A total of 100 μl of overnight grown PA14 culture in LB was spread on a 55 mm NGM plate containing 10 μg/ml FuDR. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h, and 90 Day 1 adults grown on NGM-OP50 or NGM-HT115/skn-1 RNAi in the presence of FuDR were transferred to 3 plates each containing 30 animals (in triplicates) and incubated at 25°C. The number of animals alive was counted every 24 h and dead animals defined as unresponsive to touch were removed from the plate. The experiment was continued until all animals on the plate were dead.

Microsporidia N. parisii infection assays

The 600 synchronized L1 stage worms for each genotype were plated to NGM + E. coli OP50-1 and grown to the young adult life stage at 23°C (48 h for all stains except for pals-22(jy1) mutants, which are developmentally delayed [5] and therefore were grown for 52 h). The 600 young adults were washed off the plate with M9 + 0.1% Tween-20 (M9-T), pelleted, and the supernatant was removed. The worms were then mixed with 2 million N. parisii spores (strain ERTm1), 50 μl of 10× concentrated E. coli OP50-1, and M9 to a final volume of 300 μl. The infection mix was top-plated over the entire surface of a 6-cm NGM plate, dried at room temperature, and transferred to 25°C for 3 h. Following the 3 h pulse infection, the worms were collected from the infection plate with M9-T into a 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube, pelleted, and then washed 3 additional times with 1 ml of M9-T. The infected worms were then transferred to an NGM + E. coli OP50-1 plate without N. parisii spores and returned to 25°C for an additional 27 h. Infected animals were then fixed in 100% acetone and incubated at 46°C overnight with FISH probes conjugated to the red Cal Fluor 610 fluorophore that hybridize to N. parisii ribosomal RNA (Biosearch Technologies). Samples were analyzed for N. parisii meronts [55] using an ImageXpress Nano plate reader using the 4× objective (Molecular Devices, LLC). The worm area was traced using FIJI software and the average red fluorescence intensity of each worm was quantified with the background fluorescence of the well subtracted, and 50 animals per genotype were quantified for each experimental replicate, and 3 independent infection experiments were performed.

For the tissue-specific skn-1a rescue strains MBA1660, MBA1661, and MBA1662, approximately 100 bus-1p::GFP-expressing worms were manually picked onto N. parisii infection assay plates. For consistency, approximately 100 adults for WT and skn-1a(mg570) controls were also picked in the same manner and pulse infection was performed as described above. To remove any potential bias, the order in which strains were picked was randomized from assay to assay, and the 30 hpi endpoints were staggered to account for picking time. Fixation and FISH hybridization were performed as described above. For quantification, fixed animals for each strain were mounted to a 5% agarose pad on a microscope slide and imaged on a Zeiss AxioImager M1 compound microscope using a 2.5× objective. The worm area was traced using FIJI software and the average red fluorescence intensity of each worm was quantified with the background fluorescence of the slide subtracted. In some samples, we observed dim red autofluorescence from embryos inside the adult gonad. Thus, this region of the worm was omitted in all samples when tracing the worm area. Analysis with the ImageXpress plate reader and Zeiss AxioImager produced different arbitrary values for N. parisii FISH pixel intensity. However, the fold difference in infection between WT animals and skn-1a(mg570) mutants was similar (WT animals are approximately 1.5-fold more infected than skn-1a(mg570)) by both imaging and quantification methods, and 50 animals per genotype were quantified for each experimental replicate, and 3 independent infection experiments were performed.

RNAseq

For transcriptome analysis, synchronized L4 stage animals were collected in triplicates for RNA extraction using TRIzol (Invitrogen) and isopropanol/ethanol precipitation. RNA sequencing was completed by BGI (Hong Kong). Kallisto [56] was used for alignments with the WS283 transcriptome from Wormbase. Count analysis was performed using Sleuth [57] along with a Wald test to calculate log2fold changes. All RNAseq data files are publicly available from the NCBI GEO database under the accession number GSE241087.

RT-qPCR

Synchronized L4 stage animals with 4-h extract treatment or without were collected in TRIzol (Invitrogen) followed by RNA extraction using isopropanol/ethanol precipitation. RNA was quantified using NanoDrop (Thermo Scientific) and its quality was analyzed by gel electrophoresis. cDNA was synthesized using 2 μg RNA with Superscript IV (Invitrogen) and Oligo(dT) primers as per manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR was performed using qPCR primer pairs listed in S2 Table and LightCycler480 SYBR Green I Master Mix (Roche) in a LightCycler480 instrument, and Ct values were derived using the LightCycler480 software and second derivative maximum method. All experiments were performed in biological triplicates and changes in expression were calculated via the 2-ΔΔCt method.

Microscopy

Animals to be imaged were picked into a drop (5 to 7 μl) of M9 containing sodium azide (50 μm) on an agarose (1%) pad made on a glass slide. Coverslip was added once the animals were paralyzed, and the pad was almost dry. chil-27p::GFP/col-12p::mCherry expression was observed on Zeiss Axio Zoom V16 microscope and images were taken using the associated ZEN Microscopy software. For rpt-3p::GFP and sur-5::UbV-GFP, animals were treated with oomycete extract or 20 μm BTZ with DMSO control for 24 h at early L2 stage and expression was observed on Zeiss Compound microscope (AxioScope A1) at 40× magnification and images were taken using OCULAR. For chil-27p::GFP expression upon BTZ treatment, early L4 stage animals were treated with different doses of BTZ for 24 h and adults were imaged as described above.

Molecular cloning and transgenesis

To generate constructs for tissue-specific rescue of skn-1a(mg570) mutant, skn-1a fragment was amplified from N2 cDNA using primers skn-1a_fullF and skn-1a_fullR. Promoter fragments, namely, rab-3p and vha-6p were amplified from N2 genomic DNA using primer pairs BJ97-pRab-3Fwd, rab-3rev-skn1, bj97 vha-6 Fwd, and vha-6 Rev skn-1a, respectively. The terminator sequence from 3′UTR of unc-54 was PCR amplified from N2 genomic DNA using primers unc-54-F-skn1a and BJ36_unc-54terR. Plasmids for neuronal and intestinal rescue were assembled with specific promoter, skn-1a and unc-54 3′UTR fragments ligated into SpeI (FastDigest)-digested pBJ97 by Gibson cloning. To make the epidermal rescue plasmid, skn-1a was PCR amplified from N2 cDNA using primers dpy-7_skn-1F and dpy-7_skn-1R and was assembled into PmeI(FastDigest)-digested pIR6 by Gibson cloning. All constructs were individually injected into skn-1a(mg570) at 5 ng/μl with 25 ng/μl of pRJM163 (bus-1p::GFP) as the co-injection marker and 80 ng/μl of pBJ36 as carrier DNA. The transgenic strains thus created were used for microsporidia pathogen load assays. Similarly, all constructs were individually also injected in the strain MBA1055, which is skn-1a(mg570) mutant with chil-27p::GFP reporter in the background. For these injections, 5 ng/μl of rescue plasmid with 5 ng/μl of myo-2p::GFP as co-injection marker and 100 ng/μl of pBJ36 as carrier DNA was used. The transgenic strains thus created were analyzed for expression of chil-27p::GFP in skn-1a(mg570) mutants.

RNAi

RNAi by feeding was used as the means to induce gene knockdown in C. elegans as previously described [58]. The RNAi clone for skn-1 was obtained from the ORFeome Library (Horizon Discovery) [59] and for wdr-23 and rpt-5 were obtained from the Ahringer Library (Source BioScience) [60]. Both the clones were confirmed by sequencing prior to use. Embryos collected by bleaching gravid adults were added onto NGM plates seeded with E. coli HT115 and contained 1 mM IPTG (Sigma) to induce expression of dsRNA. After 72 h of incubation at 20°C, animals at L4/adult stage were scored for chil-27p::GFP expression (n > 50). The strains used for tissue-specific RNAi were generated by introducing the chil-27p::GFP reporter in previously described strains listed in S2 Table with their associated references.

smFISH

For inducing the ORR, synchronized L2 stage animals were treated with oomycete extract for 4 h. For inducing IPR, animals were subjected to prolonged heat stress by incubating synchronized L1s at 30°C for 24 h. For causing proteasome dysfunction, synchronized L2 stage animals were treated with 20 μm BTZ treatment for 15 min or 2 h. Following requisite treatment along with relevant controls, animals were fixed with 4% formaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) in 1× PBS (Ambion) for 45 min and were permeabilised with 70% ethanol for 24 h. Hybridization was performed at 30°C for 16 h. List of oligos included in all the probes can be found in S2 Table. Imaging was performed in an inverted and fully motorized epifluorescence microscope (Nikon Ti-eclipse) with an iKon M DU-934 CCD camera (Andor) controlled via the NIS-Elements software (Nikon) using the 100× objective. Detailed protocol can be found in [61].

Supporting information

(A) Gene structure of ddi-1 and png-1 showing the positions of mutant alleles used in this study. (B) Quantification of induction of chil-27p::GFP in the mutants obtained from the EMS screen, ddi-1(icb156), png-1(icb112), png-1(icb121) along with active-site mutant of ddi-1(mg572), in-frame gene deletion of ddi-1(mg571), png-1(ok1654), skn-1a(mg570) and upon skn-1 RNAi (n > 50, ****p-value < 0.0001, *** p-value < 0.001 based on chi-square test). The numerical data for all 3 replicates is available in Supporting information S1 Data. (C) Venn comparisons showing significant overlap between up-regulated genes in the transcriptome of ddi-1(icb156) and skn-1a(mg570) mutant with bortezomib (BTZ)-treated animals (RF 6.0, p < 4.347e-43 and RF 18.6, p < 4.453e-88, respectively).

(TIF)

(A) Gene structure of skn-1a and skn-1c isoforms with protein domain organization. (B) Both loss (skn-1 RNAi) or gain (wdr-23 RNAi) of SKN-1C function does not affect chil-27p::GFP expression in skn-1a(mg570) (control RNAi) animals. skn-1a(mg570) animals are sensitive to RNAi as shown by the gfp RNAi treatment leading to complete loss of chil-27p::GFP expression (left panel). wdr-23 RNAi activates SKN-1C and leads to expression of gst-4p::tdTomato as shown in the right panel. (n > 50 per condition, performed in triplicates, representative image shown). Scale bar is 100 μm. (C) Survival curve of WT and skn-1a(mg570) animals treated and untreated with skn-1 RNAi in the presence of the oomycete M. humicola (n = 60 per condition, performed in triplicates, p < 0.001 based on log-rank test, a representative graph for one of the 3 replicates is shown). The numerical data for all 3 replicates is available in Supporting information S1 Data.

(TIF)

(A) chil-27p::GFP expression in WT animals treated with different doses of BTZ at early L4 stage for 24 h (n > 50 for each condition, performed in triplicates, representative image shown). (B) Z-stack of L2 stage WT animals showing expression of chil-27 mRNA upon 15 min and 1 h post extract and BTZ treatment. Scale bar is 100 μm in (A) and 10 μm in (B). (C) Survival curve of WT animals treated with DMSO or 20 μm BTZ in the presence of the oomycete M. humicola (n = 60 per condition, performed in triplicates, p < 0.001 based on log-rank test, a representative graph for one of the 3 replicates is shown). The numerical data for all 3 replicates of panels S3A and C is available in Supporting information S1 Data.

(TIF)

skn-1 RNAi induces chil-27p::GFP expression in pals-25(jy81) and old-1(ok1273) mutant animals. Scale bar for all panels is 100 μm, and n > 50 per condition, performed in triplicates, representative image shown.

(TIF)

In the absence of extract treatment in animals with constitutive expression of the activated form of SKN-1A[skn-1a(cut, 4ND) in skn-1a(mg570)] or constitutive activation of the proteasome [pas-3(α3ΔN)] no expression of ORR genes was observed similar to wild-type animals. Note that ORR gene expression in skn-1a(mg570) mutants is lower compared to extract-treated wild-type animals (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001 based on unpaired t test). The numerical data for all 3 replicates is available in Supporting information S1 Data.

(TIF)

Whole animal mRNA quantification by smFISH for 4 genes, namely, B0507.8 (A), pals-5 (B), cul-6 (C), and skr-3 (D) in L2-stage animals subjected to prolonged heat stress (30°C for 24 h), extract treatment (4 h), and 20 μm BTZ treatment (2 h) (n = 12 in each condition and one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used to assess statistical significance, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). The numerical data for graphs A–D is available in Supporting information S1 Data.

(TIF)

Survival analysis of adult C. elegans on PA14 where bacteria was spread on the plate (n = 90 per condition, performed in triplicates, p < 0.001 based on log-rank test, a representative graph for one of the 3 replicates is shown). The numerical data for all 3 replicates is available in Supporting information S1 Data.

(TIF)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Domenica Ippolito and Kenneth Liu for comments on the manuscript. Some strains were provided by the CGC, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440). We thank Gary Ruvkun, Thorsten Hoppe, Keith Choe, and David Smith for strains.

Abbreviations

- BTZ

bortezomib

- EMS

ethyl methanesulfonate

- IPR

intracellular pathogen response

- ORR

oomycete recognition response

- PRAAS

proteasome-associated autoinflammatory syndrome

- smFISH

single molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization

- UPR

unfolded protein response

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files. All RNAseq files are available from the NCBI GEO database (accession number GSE241087).

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust, UK (219448/Z/19/Z to MB) and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, UK (BB/X001865/1 to MB and ERT). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Schulenburg H, Felix MA. The natural biotic environment of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2017;206(1):55–86. doi: 10.1534/genetics.116.195511 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5419493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osman GA, Fasseas MK, Koneru SL, Essmann CL, Kyrou K, Srinivasan MA, et al. Natural infection of C. elegans by an oomycete reveals a new pathogen-specific immune response. Curr Biol. 2018;28(4):640–8 e5. Epub 2018/02/06. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.01.029 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fasseas MK, Grover M, Drury F, Essmann CL, Kaulich E, Schafer WR, Barkoulas M. Chemosensory neurons modulate the response to oomycete recognition in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell Rep. 2021;34(2):108604. Epub 2021/01/14. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108604 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7809619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakowski MA, Desjardins CA, Smelkinson MG, Dunbar TL, Lopez-Moyado IF, Rifkin SA, et al. Ubiquitin-mediated response to microsporidia and virus infection in C. elegans. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(6):e1004200. Epub 20140619. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004200 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4063957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reddy KC, Dror T, Sowa JN, Panek J, Chen K, Lim ES, et al. An intracellular pathogen response pathway promotes proteostasis in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2017;27(22):3544–53 e5. Epub 2017/11/07. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.10.009 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5698132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Y, Sun J. Detection of pathogens and regulation of immunity by the Caenorhabditis elegans nervous system. MBio. 2021;12(2). Epub 2021/04/01. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02301-20 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8092265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pukkila-Worley R. Surveillance immunity: an emerging paradigm of innate defense activation in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12(9):e1005795. Epub 2016/09/16. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005795 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5025020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunbar TL, Yan Z, Balla KM, Smelkinson MG, Troemel ER. C. elegans detects pathogen-induced translational inhibition to activate immune signaling. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11(4):375–86. Epub 2012/04/24. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.02.008 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3334869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McEwan DL, Kirienko NV, Ausubel FM. Host translational inhibition by Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin A triggers an immune response in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11(4):364–74. Epub 2012/04/24. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.02.007 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3334877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melo JA, Ruvkun G. Inactivation of conserved C. elegans genes engages pathogen- and xenobiotic-associated defenses. Cell. 2012;149(2):452–66. Epub 2012/04/17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.050 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3613046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reddy KC, Dunbar TL, Nargund AM, Haynes CM, Troemel ER. The C. elegans CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein gamma is required for surveillance immunity. Cell Rep. 2016;14(7):1581–9. Epub 2016/02/16. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.055 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4767654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pellegrino MW, Nargund AM, Kirienko NV, Gillis R, Fiorese CJ, Haynes CM. Mitochondrial UPR-regulated innate immunity provides resistance to pathogen infection. Nature. 2014;516(7531):414–7. Epub 2014/10/03. doi: 10.1038/nature13818 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4270954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tjahjono E, Kirienko NV. A conserved mitochondrial surveillance pathway is required for defense against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS Genet. 2017;13(6):e1006876. Epub 2017/07/01. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006876 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5510899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tecle E, Chhan CB, Franklin L, Underwood RS, Hanna-Rose W, Troemel ER. The purine nucleoside phosphorylase pnp-1 regulates epithelial cell resistance to infection in C. elegans. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17(4):e1009350. Epub 2021/04/21. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009350 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8087013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lazetic V, Batachari LE, Russell AB, Troemel ER. Similarities in the induction of the intracellular pathogen response in Caenorhabditis elegans and the type I interferon response in mammals. BioEssays. 2023;45(11):e2300097. Epub 20230904. doi: 10.1002/bies.202300097 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reddy KC, Dror T, Underwood RS, Osman GA, Elder CR, Desjardins CA, et al. Antagonistic paralogs control a switch between growth and pathogen resistance in C. elegans. PLoS Pathog. 2019;15(1):e1007528. Epub 2019/01/15. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007528 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6347328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blackwell TK, Steinbaugh MJ, Hourihan JM, Ewald CY, Isik M. SKN-1/Nrf, stress responses, and aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;88(Pt B):290–301. Epub 2015/08/02. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.06.008 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4809198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lehrbach NJ, Ruvkun G. Proteasome dysfunction triggers activation of SKN-1A/Nrf1 by the aspartic protease DDI-1. elife. 2016;5. Epub 2016/08/17. doi: 10.7554/eLife.17721 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4987142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lehrbach NJ, Breen PC, Ruvkun G. Protein sequence editing of SKN-1A/Nrf1 by peptide:N-glycanase controls proteasome gene expression. Cell. 2019;177(3):737–50 e15. Epub 2019/04/20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.03.035 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6574124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radhakrishnan SK, Lee CS, Young P, Beskow A, Chan JY, Deshaies RJ. Transcription factor Nrf1 mediates the proteasome recovery pathway after proteasome inhibition in mammalian cells. Mol Cell. 2010;38(1):17–28. Epub 2010/04/14. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.029 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2874685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li X, Matilainen O, Jin C, Glover-Cutter KM, Holmberg CI, Blackwell TK. Specific SKN-1/Nrf stress responses to perturbations in translation elongation and proteasome activity. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(6):e1002119. Epub 2011/06/23. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002119 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3111486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.An JH, Blackwell TK. SKN-1 links C. elegans mesendodermal specification to a conserved oxidative stress response. Genes Dev. 2003;17(15):1882–93. Epub 2003/07/19. doi: 10.1101/gad.1107803 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC196237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoeven R, McCallum KC, Cruz MR, Garsin DA. Ce-Duox1/BLI-3 generated reactive oxygen species trigger protective SKN-1 activity via p38 MAPK signaling during infection in C. elegans. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(12):e1002453. Epub 2012/01/05. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002453 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3245310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papp D, Csermely P, Soti C. A role for SKN-1/Nrf in pathogen resistance and immunosenescence in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(4):e1002673. Epub 2012/05/12. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002673 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3343120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu C, Karakuzu O, Garsin DA. Tribbles pseudokinase NIPI-3 regulates intestinal immunity in Caenorhabditis elegans by controlling SKN-1/Nrf activity. Cell Rep. 2021;36(7):109529. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109529 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8393239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khush RS, Cornwell WD, Uram JN, Lemaitre B. A ubiquitin-proteasome pathway represses the Drosophila immune deficiency signaling cascade. Curr Biol. 2002;12(20):1728–37. Epub 2002/10/29. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01214-9 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Engel E, Viargues P, Mortier M, Taillebourg E, Coute Y, Thevenon D, et al. Identifying USPs regulating immune signals in Drosophila: USP2 deubiquitinates Imd and promotes its degradation by interacting with the proteasome. Cell Commun Signal. 2014;12:41. Epub 2014/07/17. doi: 10.1186/s12964-014-0041-2 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4140012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ebstein F, Poli Harlowe MC, Studencka-Turski M, Kruger E. Contribution of the unfolded protein response (UPR) to the pathogenesis of proteasome-associated autoinflammatory syndromes (PRAAS). Front Immunol. 2019;10:2756. Epub 2019/12/13. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02756 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6890838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brehm A, Liu Y, Sheikh A, Marrero B, Omoyinmi E, Zhou Q, et al. Additive loss-of-function proteasome subunit mutations in CANDLE/PRAAS patients promote type I IFN production. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(11):4196–211. Epub 2015/11/03. doi: 10.1172/JCI81260 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4639987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gang SS, Grover M, Reddy KC, Raman D, Chang YT, Ekiert DC, et al. A pals-25 gain-of-function allele triggers systemic resistance against natural pathogens of C. elegans. PLoS Genet. 2022;18(10):e1010314. Epub 2022/10/04. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1010314 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC9560605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Consortium CeDM. large-scale screening for targeted knockouts in the Caenorhabditis elegans genome. G3 (Bethesda). 2012;2(11):1415–25. Epub 2012/11/23. doi: 10.1534/g3.112.003830 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3484672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choe KP, Przybysz AJ, Strange K. The WD40 repeat protein WDR-23 functions with the CUL4/DDB1 ubiquitin ligase to regulate nuclear abundance and activity of SKN-1 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29(10):2704–15. Epub 2009/03/11. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01811-08 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2682033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lo JY, Spatola BN, Curran SP. WDR23 regulates NRF2 independently of KEAP1. PLoS Genet. 2017;13(4):e1006762. Epub 20170428. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006762 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5428976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lehrbach NJ, Ruvkun G. Endoplasmic reticulum-associated SKN-1A/Nrf1 mediates a cytoplasmic unfolded protein response and promotes longevity. elife. 2019;8. Epub 2019/04/12. doi: 10.7554/eLife.44425 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6459674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olaitan AO, Aballay A. Non-proteolytic activity of 19S proteasome subunit RPT-6 regulates GATA transcription during response to infection. PLoS Genet. 2018;14(9):e1007693. Epub 2018/09/29. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007693 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6179307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang P, Qu H-Y, Wu Z, Na H, Hourihan J, Zhang F, et al. ERK signaling licenses SKN-1A/NRF1 for proteasome production and proteasomal stress resistance. bioRxiv. 2021:2021.01.04.425272. doi: 10.1101/2021.01.04.425272 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Calixto A, Chelur D, Topalidou I, Chen X, Chalfie M. Enhanced neuronal RNAi in C. elegans using SID-1. Nat Methods. 2010;7(7):554–9. Epub 2010/06/01. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1463 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2894993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Espelt MV, Estevez AY, Yin X, Strange K. Oscillatory Ca2+ signaling in the isolated Caenorhabditis elegans intestine: role of the inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor and phospholipases C beta and gamma. J Gen Physiol. 2005;126(4):379–92. Epub 2005/09/28. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509355 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2266627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Drury F, Grover M, Hintze M, Saunders J, Fasseas MK, Constantinou C, et al. A PAX6-regulated receptor tyrosine kinase pairs with a pseudokinase to activate immune defense upon oomycete recognition in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120(39):e2300587120. Epub 20230919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2300587120 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC10523662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Segref A, Kevei E, Pokrzywa W, Schmeisser K, Mansfeld J, Livnat-Levanon N, et al. Pathogenesis of human mitochondrial diseases is modulated by reduced activity of the ubiquitin/proteasome system. Cell Metab. 2014;19(4):642–52. Epub 2014/04/08. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.01.016 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson RT, Bradley TA, Smith DM. Hyperactivation of the proteasome in Caenorhabditis elegans protects against proteotoxic stress and extends lifespan. J Biol Chem. 2022;298(10):102415. Epub 2022/08/26. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.102415 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC9486566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Troemel ER, Felix MA, Whiteman NK, Barriere A, Ausubel FM. Microsporidia are natural intracellular parasites of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Biol. 2008;6(12):2736–52. Epub 2008/12/17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060309 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2596862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tan MW, Mahajan-Miklos S, Ausubel FM. Killing of Caenorhabditis elegans by Pseudomonas aeruginosa used to model mammalian bacterial pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(2):715–20. Epub 1999/01/20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.715 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC15202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen DD, Jiang JY, Lu LF, Zhang C, Zhou XY, Li ZC, et al. Zebrafish Uba1 degrades IRF3 through K48-Linked ubiquitination to inhibit IFN production. J Immunol. 2021;207(2):512–22. Epub 2021/07/02. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.2100125 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Castillo-Quan JI, Steinbaugh MJ, Fernandez-Cardenas LP, Pohl NK, Wu Z, Zhu F, et al. An antisteatosis response regulated by oleic acid through lipid droplet-mediated ERAD enhancement. Sci Adv. 2023;9(1):eadc8917. Epub 20230104. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adc8917 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC9812393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zera AJ, Harshman LG. The physiology of life history trade-offs in animals. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 2001;32(1):95–126. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lažetić V, Blanchard MJ, Bui T, Troemel ER. Multiple pals gene modules control a balance between immunity and development in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Pathog. 2023;19(7):e1011120. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1011120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yan K, Zhang J, Lee PY, Tao P, Wang J, Wang S, et al. Haploinsufficiency of PSMD12 causes proteasome dysfunction and subclinical autoinflammation. Arthritis Rheum. 2022;74(6):1083–90. Epub 2022/01/27. doi: 10.1002/art.42070 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC9321778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tataridas-Pallas N, Thompson MA, Howard A, Brown I, Ezcurra M, Wu Z, et al. Neuronal SKN-1B modulates nutritional signalling pathways and mitochondrial networks to control satiety. PLoS Genet. 2021;17(3):e1009358. Epub 2021/03/05. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009358 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7932105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cetin G, Studencka-Turski M, Venz S, Schormann E, Junker H, Hammer E, et al. Immunoproteasomes control activation of innate immune signaling and microglial function. Front Immunol. 2022;13:982786. Epub 2022/10/25. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.982786 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC9584546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Waad Sadiq Z, Brioli A, Al-Abdulla R, Cetin G, Schutt J, Murua Escobar H, et al. Immunogenic cell death triggered by impaired deubiquitination in multiple myeloma relies on dysregulated type I interferon signaling. Front Immunol. 2023;14:982720. Epub 2023/03/21. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.982720 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC10018035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lazetic V, Wu F, Cohen LB, Reddy KC, Chang YT, Gang SS, et al. The transcription factor ZIP-1 promotes resistance to intracellular infection in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):17. Epub 2022/01/12. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27621-w ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8748929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stiernagle T. Maintenance of C. elegans. WormBook. 2006:1–11. Epub 20060211. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.101.1 PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4781397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Minevich G, Park DS, Blankenberg D, Poole RJ, Hobert O. CloudMap: a cloud-based pipeline for analysis of mutant genome sequences. Genetics. 2012;192(4):1249–69. Epub 2012/10/12. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.144204 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3512137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Estes KA, Szumowski SC, Troemel ER. Non-lytic, actin-based exit of intracellular parasites from C. elegans intestinal cells. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(9):e1002227. Epub 2011/09/29. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002227 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3174248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bray NL, Pimentel H, Melsted P, Pachter L. Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34(5):525–7. Epub 20160404. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3519 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pimentel H, Bray NL, Puente S, Melsted P, Pachter L. Differential analysis of RNA-seq incorporating quantification uncertainty. Nat Methods. 2017;14(7):687–90. Epub 20170605. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4324 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Timmons L, Court DL, Fire A. Ingestion of bacterially expressed dsRNAs can produce specific and potent genetic interference in Caenorhabditis elegans. Gene. 2001;263(1–2):103–12. Epub 2001/02/27. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00579-5 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reboul J, Vaglio P, Tzellas N, Thierry-Mieg N, Moore T, Jackson C, et al. Open-reading-frame sequence tags (OSTs) support the existence of at least 17,300 genes in C. elegans. Nat Genet. 2001;27(3):332–6. Epub 2001/03/10. doi: 10.1038/85913 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kamath RS, Fraser AG, Dong Y, Poulin G, Durbin R, Gotta M, et al. Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature. 2003;421(6920):231–7. Epub 2003/01/17. doi: 10.1038/nature01278 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hintze M, Koneru SL, Gilbert SPR, Katsanos D, Lambert J, Barkoulas M. A cell fate switch in the Caenorhabditis elegans seam cell lineage occurs through modulation of the wnt asymmetry pathway in response to temperature increase. Genetics. 2020;214(4):927–39. Epub 20200127. doi: 10.1534/genetics.119.302896 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7153939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]