ABSTRACT

The mycobacterial cell envelope consists of a typical plasma membrane of lipid and protein surrounded by a complex cell wall composed of carbohydrate and lipid. In pathogenic species, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, an outermost “capsule” layer surrounds the cell wall. This wall embraces a fundamental, covalently linked “cell-wall skeleton” composed of peptidoglycan, solidly attached to arabinogalactan, whose penta-saccharide termini are esterified by very-long-chain fatty acids (mycolic acids). These fatty acids form the inner leaflet of an outer membrane, called the mycomembrane, whose outer leaflet consists of a great variety of non-covalently linked lipids and glycolipids. The thickness of the mycomembrane, which is similar to that of the plasma membrane, is surprising in view of the length of mycoloyl residues, suggesting dedicated conformations of these fatty acids. Finally, a periplasmic space also exists in mycobacteria, between the plasma membrane and the peptidoglycan. This article provides a comprehensive overview of this biologically important and structurally unique mycobacterial cell compartment.

INTRODUCTION

The bacterial cell envelope, defined as the structure that surrounds the cytosol, is critical for bacterial physiology, because many crucial processes take place in this compartment. The cell wall contributes to the bacterial shape, mechanical resistance of the cells, and their protection against hostile environments. In addition, the envelope constituents are involved in cell division, transport of molecules (solutes and ions) and macromolecules (proteins), cell motility, adhesion, and protection, being in direct contact with the environment etc. The genus Mycobacterium belongs to the Corynebacteriales order, which also includes corynebacteria, nocardia, rhodococci, and other related microorganisms. Mycobacteria are probably the most successful microorganisms to parasitize animals and humans. Among the more than 200 valid species described to date in the genus Mycobacterium, only three are strict pathogens for humans: Mycobacterium tuberculosis (the Koch’s bacillus), M. leprae, and M. lepromatosis. Tuberculosis still represents a major public health problem worldwide, remaining one of the leading causes of death from an infectious agent; about one-quarter of the world’s population is infected by the Koch’s bacillus and thus susceptible to develop the disease. In addition, two-thirds of mycobacteria species are opportunistic pathogens for humans, and all mycobacteria produce granulomatous lesions in experimental animals with large enough inoculum (1). Most mycobacterial pathogenic species grow very slowly (e.g., generation times of 24 hours and 13 days for the tubercle and leprosy bacilli, respectively), whereas saprophytes are relatively rapid growers (e.g., doubling time of 6 hours for the widely used genetically tractable M. smegmatis).

Mycobacteria and related genera are classified among the Actinobacteria, a division of Gram-positive bacteria, although they do not reliably retain the stain, a clear indication of the uniqueness of their cell envelope composition (2). Dissection of their fascinating coat reveals an atypical architecture of their envelope, different from those of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (Fig. 1B). Unlike those of the former group of bacteria, with a reputed lipid-poor cell envelope (less than 10%), mycobacterial cell envelopes are extremely rich in lipids, representing up to 40% of their cell dry mass, more than the recorded 20% in Gram-negative bacteria (3). This high lipid content is in agreement with the huge number of genes devoted to the synthesis and regulation of this class of compounds (4). This hallmark would explain the tendency of mycobacteria to grow in clumps and their distinctive property of acid-fastness, but also their impermeability to nutrients and small molecules and their resistance to alkali, dilute acid, and infected mammalian cells (3).

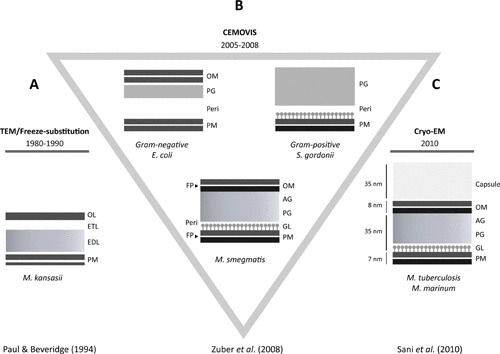

FIGURE 1.

Diagrams (adapted from references 11 and 17–19) of the cell envelopes extracted from images obtained by (A) TEM, (B) CEMOVIS of various bacterial cells, and (C) cryoEM of whole-mount mycobacteria. AG, arabinogalactan; CEMOVIS, cryo-electron microscopy of vitreous sections; cryo-EM, cryo-electron microscopy; EDL, electron-dense layer; ETL, electron-transparent layer; FP, fracture plane; GL, granular layer; OL, outer layer; OM, outer membrane; PG, peptidoglycan; PM, plasma membrane; peri, periplasm; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

Reviews have been recently published on the biogenesis (5), structures (6), and transport (2, 7, 8) of mycobacterial cell envelope constituents. This chapter highlights major advances in deciphering key biological and structural features of this unique and fascinating mycobacterial coat.

THE MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCE OF THE MYCOBACTERIAL CELL ENVELOPE

When studied by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), the mycobacterial cell envelope recurrently displays a multilayered structure (Fig. 1A). In TEM, the specimen is fixed prior to being embedded in a hydrophobic resin, followed by ultrathin sectioning and staining with heavy-metal salts. Consequently, fixation protocols and the use of different solvents can lead to extraction and shrinkage of its different constituents. Lipids noncovalently attached to cell wall polymers may be extracted by solvents during the dehydration step, and water-rich structures may collapse (9, 10). In ultrathin conventional sections (11), the cell envelope of mycobacteria looks more like that of Gram-positive bacteria (Fig. 1). It consists of a plasma membrane (PM), a thick electron-dense layer, an electron-transparent layer, and an outer layer of variable density and thickness (Fig. 1). The PM appears asymmetrical in images of some conventionally prepared cells, with the accumulation of material in its outer leaflet (12–14). This asymmetry, however, is dependent upon conditions of fixation (15). To circumvent these disadvantages, freeze-substitution techniques have been used (16, 17), but with little success, because the resulting images were diffuse and not resolved as expected (Fig. 1A).

More recently, cryo-electron microscopy of vitreous sections (CEMOVIS) and cryo-electron microscopy (cryoEM) of whole-mount cells have been applied to mycobacteria (Fig. 1B). In these techniques, the specimens are observed at liquid nitrogen temperature, which allows them to be imaged in their fully hydrated and unstained state. As expected, images observed for the mycobacterial cell envelope look significantly different from those seen by TEM (11, 18, 19). They revealed a symmetrical PM, a periplasm containing a granular layer presumably consisting of proteins, and for the first time, the presence of a long-predicted outer membrane (Fig. 1B). The existence of an outer membrane was supported by data from freeze-fracture electron microscopy, which clearly showed the occurrence of a major fracture plane in the outer part of the envelope, in addition to the expected plane that typifies the PM (Fig. 1B). However, no direct observations of the hypothetical outer membrane were available using TEM. The demonstration of the existence of an outer membrane fits nicely with the very low permeability of mycobacteria to nutrients and antibacterial drugs, 10- to 100-fold lower than that of the notably impermeable bacillus Pseudomonas aeruginosa (20). Consistently, mycobacteria and other members of the Corynebacteriales order contain pore-forming proteins (porins) in their cell walls (21).

During eukaryotic cell infection, a space between the wall of M. lepraemurium and the phagosomal membrane was observed in electron microscopic pictures, called the “capsular space” (22). Almost concomitantly, when studying the permeability of mycobacteria to dyes using light microscopic techniques, a tentative correlation was made between the capsule space and an unstainable halo observed only around some pathogenic mycobacteria (23–25). According to Hanks (26), this halo would also correspond to the “electron-transparent zone” that is seen in several published electron micrographs surrounding intracellular mycobacterial pathogens but not around nonpathogenic mycobacteria or pathogenic mycobacteria grown in vitro under standard conditions (27, 28). Consistently, a capsule-like structure was observed around in vitro-grown pathogenic mycobacteria that were first either coated with specific antibodies or preembedded in gelatin prior to the different drastic treatments involved in conventional electron microscopy studies (29, 30). Under these conditions, the capsule-like structure was not seen around the nonpathogenic M. smegmatis and M. aurum (30). Definitive proof of the existence of a capsule in pathogenic mycobacteria came from whole-mount plunge-frozen mycobacteria imaged by cryoEM (Fig. 1C), which does not require the use of a cryo-protectant and under conditions where they were grown without detergent or shaking (19). The layer was not observed in CEMOVIS pictures (Fig. 1B) (11, 18), probably because the density of the capsule matches that of the cryo-protectant-containing freezing solution. Likewise, the capsule was not observed in pictures of mycobacteria grown in detergent-containing culture media, which is routinely used to prevent mycobacterial cell clumping (19). When the same bacteria are instead processed by conventional methods commonly used to observe mycobacteria by TEM, the outer layer probably collapses by dehydration to give a dark layer (outer layer, Fig. 1A).

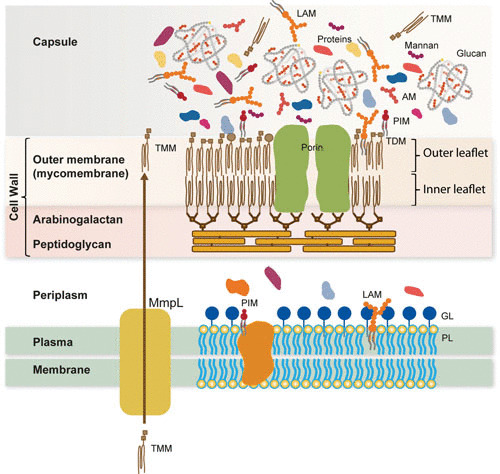

From the combination of chemical and microscopic data, it is now well established that the mycobacterial envelope consists of a PM surrounded by a complex cell wall composed of peptidoglycan (PG) covalently linked to arabinogalactan (AG) esterified by mycolic acids (MAs), which form the inner leaflet of an outer membrane bilayer. MAs are very-long-chain, up to 100 carbons, 2-alkyl 3-hydroxylated fatty acids. An outermost layer, called “capsule” in the case of pathogenic species (9), in turn surrounds the cell wall (Fig. 1C). A periplasmic space, defined as the region located between the PM and the cell wall PG exists in mycobacteria, as revealed by CEMOVIS (Fig. 1B).

THE PLASMA MEMBRANE

The bilayer structure of the mycobacterial PM is similar to that of other Gram-positive and -negative microorganisms (Fig. 1), consistent with the published chemical composition, comprising phospholipids and proteins, with specific metabolic functions (9). Its asymmetrical appearance in images of some conventionally prepared cells (12, 15) has been attributed to the presence of excess glycoconjugates, e.g., phosphatidylinositol mannosides (PIMs), lipoarabinomannan (LAM), and lipomannan, in the thicker outer leaflet. Although glycoconjugates were identified in the PM (see below), their distribution between the two leaflets is not known. Alternatively, the observed apparent thicker outer leaflet in some conventional preparations may be due to the collapse of the granular layer, presumably composed of proteins, by a few nanometers beyond the outer leaflet of the PM (11), as shown by CEMOVIS (see Fig. 1).

The native PM is typically and easily obtained by breaking the cells by mechanical stress, e.g., sonication or shearing in the French pressure cell, followed by fractionation using differential centrifugation or density gradients (31, 32). The determination of specific enzyme activities, e.g., NADH oxidase (31), generally follows the purification process. Further chemical and biochemical analyses of the fractions are necessary to check their purity (31, 32). As far as lipid composition of the purified PM is concerned, no significant difference between those of fast- and slow-growing Mycobacterium species examined have been observed. Polar lipids, mainly phospholipids, assemble in association with proteins into a lipid bilayer (see 33). The polar lipids of the mycobacterial PM are composed of hydrophilic head groups and fatty acid chains that usually consist of mixtures of straight chain, unsaturated and mono-methyl branched fatty acid residues fewer than 20 carbons. Palmitic (C16:0), oleic (cis Δ9 C18:1), and 10-methyloctadecanoic (called tuberculostearic) acids are the major fatty acid constituents of the isolated PMs. The main phospholipids of the PM are PIM, phosphatidyl glycerol, cardiolipid, and phosphatidyl ethanolamine, while phosphatidyl inositol occurs in small amounts. Incidentally, PIM and phosphatidyl ethanolamine have also been identified among the lipids extracted from the mycobacterial cell surface by means of gentle mechanical treatment of cells with glass beads (34), yet the function of phospholipids in those layers is still unknown. Besides phospholipids, other lipids, such as menaquinones, may be present in the PM (see 33). The mycobacterial lipopolysaccharides LAM and lipomannan are partly located in the PM, and the relative contents of both lipopolysaccharides are growth-phase dependent (31, 35). The lipid composition of the PM of M. smegmatis also has been determined using detergent extraction, namely, with dioctyl sulfosuccinate sodium (36). The composition of the PM of M. smegmatis isolated by the latter method differs significantly from that obtained by breaking the cells by mechanical stress followed by fractionation using differential centrifugation or density gradients (31, 32). Notably, trehalose monomycolate (TMM), a lipid never reported in isolated mycobacterial PMs (9), was found in the PM using the detergent extraction method (36). Rather, TMM has been isolated from the cell surface of several mycobacterial species by mechanical treatment (34).

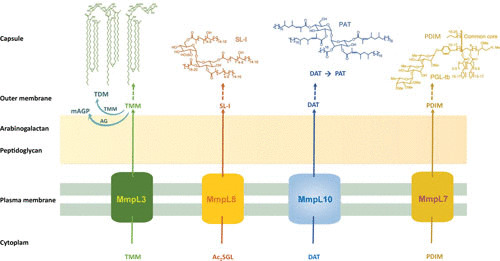

Bottom-up quantitative proteomics analysis allowed the identification of more than 2,000 membrane proteins in the purified PM of M. smegmatis (31). These include the canonical membrane ATP synthase, cytochrome P450, and ABC transporter YjfF, as well as enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of PIM, e.g., the mannosyltransferase PimB (37) and galactofuranosyltransferase GlfT2 (38). To assemble their cell wall components, which include PG, AG, lipids, and lipoproteins, as well as surface and outer membrane proteins (OMPs) (see below), mycobacteria must transport them or their precursors. Although little is known about the transport of these constituents from the cytosolic compartment to the exterior of the cell, mechanisms similar to those functioning in Gram-negative bacteria have been postulated (2, 7). Consistently, several transmembrane proteins such as MmpL (mycobacterial membrane protein large), involved in the transport of various lipids (2, 7), have been located, at least partly, in the PM (Fig. 2). Among the MmpLs of M. tuberculosis, MmpL3 is involved in the transport of TMM, and MmpL7 mediates the transport of phthiocerol dimycocerosate, whereas MmpL10 was reported to participate in the translocation of acylated trehaloses. All these lipids contribute to the integrity of the cell envelope, regulate membrane permeability, and have important physiological functions. The PM also contains the sophisticated secretion systems, named 6-kDa early secretory antigenic target (ESAT6) protein family secretion systems (also known as type VII secretion systems), used to export a set of effector proteins that help the pathogen resist or evade the host immune response (8).

FIGURE 2.

Chemical structures of representative mycobacterial lipids and their export systems through the plasma membrane to reach their final locations in the outer membrane (mycomembrane) or/and capsular compartment of the cell envelope. Some of the lipids are ubiquitous (e.g., TMM and trehalose dimycolate), whereas other are species- or type species-specific (e.g., PAT, phthiocerol dimycocerosate, PGL-tb), found in selective mycobacterial species or strains. TMM is used to transfer its mycoloyl residue onto both the arabinan termini of AG and TMM to yield the cell wall skeleton mAGP and trehalose dimycolate, respectively. Ac2SGL, diacylated sulfoglycolipid; AG, arabinogalactan; DAT, diacyl trehalose; mAGP, mycoloyl-AG-peptidoglycan; mAGP, mycoloyl-AG-peptidoglycan; MmpL, mycobacterial membrane protein large; PAT, polyacyltrehalose; PDIM, phthiocerol dimycocerosate; PGL-tb, phenol glycolipid of M. tuberculosis; SL-I, sulfolipid I, the major sulfolipid of M. tuberculosis; TDM, trehalose dimycolate; TMM, trehalose monomycolate.

THE CELL WALL

The cell wall of mycobacteria and related genera differs in composition from those of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. It is a giant complex constituted of the outer membrane bilayer, AG, and PG. The mycobacterial outer membrane, also known as mycomembrane (MM), exhibits a 7- to 8-nm thickness (Fig. 1B), similar to that of the PM, and contains MAs. MAs form the inner leaflet of the MM, covalently linked to AG, which in turn is covalently attached to PG, a complex polymer classified as A1γ, as in Escherichia coli and Bacillus spp. This represents the so-called mAGP (mycoloyl-arabinogalactan-peptidoglycan), formerly known as the cell wall skeleton, defined as the material remaining after removal of all non-covalently bound wall-associated substances (39). The outer leaflet of the MM is presumably composed of various lipids (31).

Mycobacterial walls are readily isolated and purified from fragments of PM and cytosolic material by breaking the cells with mechanical stress, followed by purification using differential centrifugation or density gradients to remove unbroken cells (see 31, 32). The mycobacterial cell wall appears in conventional TEM (40) as an electron-dense layer surrounded by an electron-transparent layer (Fig. 1A). The occurrence of the latter in sections of Corynebacteriales devoid of MAs, e.g., Corynebacterium amycolatum (41), calls into question the long-assumed interpretation that the low density of the electron-transparent layer is attributed to lipids, notably MA.

The cell wall can be dissected into its constituent parts by relatively gentle methods so that each part may be studied separately (see 42–44). The PG is composed of repeating units of N-acetylglucosamine and N-acetyl/glycolylmuramic acid cross-linked with a peptide side chain that may be cross-linked to that of other glycan strands. The tetrapeptide side chains of PG consist of l-alanyl-d-isoglutaminyl-meso-diaminopimelyl-d-alanine. These peptide chains are heavily cross-linked, with up to 80% cross-linking, compared with 50% in E. coli (3). Interestingly, the PG of M. leprae has a glycine residue substituted for the l-alanine residue found in the PG of Mycobacterium spp. examined to date.

The AG is a branched heteropolysaccharide that contains a galactan chain composed of alternating 5- and 6-linked d-galactofuranosyl residues; three d-arabinan chains substituted the d-galactan chain in M. tuberculosis, of which MAs (45) esterify two-thirds of the nonreducing termini of the penta-arabinosyl motifs. In fact, MAs (Fig. 2) esterify the four-hydroxyl groups at position 5 of both terminal and 2-linked d-arabinofuranosyl of the penta-arabinosyl motifs of AG. The cell wall of the in vivo-grown leprosy bacillus (a yet in vitro noncultivable bacterium) was found to contain significantly more AG-MA attached to PG than that of in vitro-grown M. tuberculosis, and only half of these are occupied by mycoloyl residues (46).

In 1982, Minnikin proposed an original model of an outer membrane analogous to that found in Gram-negative bacteria. In this model, the very-long-chain MAs that esterified the AG arranged themselves to form the inner leaflet of an asymmetric outer membrane, the outer leaflet being constituted of free polar mycolate trehaloses (33). This suggested the existence of a second hydrophobic layer in addition to the PM and could explain the very low permeability to polar molecules. It could also provide a good explanation for the additional and main fracture plane observed in freeze fractures of mycobacteria (47–51): the fracture would occur between the two leaflets of the outer membrane (Fig. 1B). This model was later supported by experimental data (see 52), notably the work of Nikaido and his colleagues, who showed that an aqueous suspension of purified walls of M. chelonae produced an X-ray diffraction pattern with reflections characteristic of close-packed hydrocarbon chains in a semicrystalline monolayer (53). However, the complete lack of observation of this outer membrane bilayer in transmission electron micrographs of sectioned mycobacterial cells seriously called into question the validity of this model.

Using CEMOVIS, three research groups have independently clearly visualized a symmetrical 7- to 8-nm-thick bilayer whose thickness was comparable to that of PM in the mycobacterial species analyzed (11, 18, 19). The thickness of the outer membrane MM was even less in corynebacteria, around 4 to 5 nm (11, 18). The fact that the outer membrane contains MA was proved by the absence of this structure in a mycolate-less Corynebacterium mutant. LAM and lipomannan located in the MM would presumably be associated with its outer leaflet (Fig. 3), comparable to the location of LPS in Gram-negative organisms (31, 35). Among the lipids proposed to compose the outer leaflet of the MM in various models, TMM, trehalose dimycolate (Fig. 2), and phospholipids (cardiolipid/phosphatidyl glycerol, phosphatidyl ethanolamine, and phosphatidyl inositol, plus a few PIMs) have been clearly identified in the MM-containing fractions of M. smegmatis (31). The 7- to 8-nm thickness of the outer membrane layer contradicts the arrangement of MA, whose long alkyl chains would be organized parallel to one another to yield a >40-nm-thick asymmetrical bilayer (33). In view of the 7- to 8-nm thickness of the MM in the observed micrographs (Fig. 1B), the alkyl chains of MA have to be arranged in a folded manner (as shown for TMM and trehalose dimycolate in Fig. 2). Consistent with the published chemical structures and fold of mycobacterial MAs (54, 55), a model was proposed in which mycoloyl chains are intercalated in a zipper-like manner and the long mycoloyl chains are folded in an ω-shape (11).

FIGURE 3.

Model of the mycobacterial cell envelope. The cell envelope consists of a plasma membrane, a periplasm, the cell wall skeleton, and the outermost layer, called capsule in the case of pathogenic species. The plasma membrane is composed of phospholipids (e.g., PIM), lipopolysaccharides (e.g., LAM), and proteins, which include MmpL involved in the transport of lipids. The periplasmic space contains the GL and, presumably other proteins. The cell wall skeleton is made of peptidoglycan, arabinogalactan and mycolic acid residues that form the inner leaflet of the outer membrane (mycomembrane). The outer leaflet of the latter membrane is composed of various lipids, notably, trehalose mycolates. The capsular layer is a matrix of glucan that contains proteins, (lipo)polysaccharides, and small amounts of lipids. AM, arabinomannan; LAM, lipoAM; GL, granular layer; MmpL, mycobacterial membrane protein large; PIM, phosphatidyl inositol mannosides; PL, phospholipids; TDM, trehalose dimycolate; TMM, trehalose monomycolate.

Like Gram-negative bacteria, mycobacteria need to transport and assemble their outer membrane and to import small polar molecules across their outer membrane, notably those needed for nutrition. In Gram-negative bacteria, the transport of lipids, lipoproteins, and outer membrane proteins (OMPs) involves a combination of ATP-dependent transporters in the PM, chaperones in the periplasm, and β-barrel proteins that facilitate the insertion and translocation/folding into the outer membrane (2). The nutrition issue is solved by producing specialized proteins called porins, which form hydrophilic pores through the structure (Fig. 3). These pore-forming proteins have been identified in the walls of both fast-growing mycobacterial species, such as M. chelonae and M. smegmatis (21, 56, 57), and M. tuberculosis (58, 59). However, as Rv0899 (OmpA-Tb) adopts a mixed alpha/beta-structure and does not form a transmembrane beta-barrel (60), its status as a porin is a matter of debate (21). As expected, the crystal structure of the major OMP of M. smegmatis, MspA, reveals a β-barrel transmembrane channel (61). MspA forms an octameric composite β-barrel where each monomer comprises two β-strands. In Gram-negative bacteria, such as E. coli, there are about 60 OMPs. Using in silico analysis, two independent studies have proposed a list of putative OMPs in M. tuberculosis based essentially on β-barrel computational predictions (21). Out of 100 putative mycobacterial OMPs, only a few have been identified and characterized. These include mycoloyl transferases (originally called Fbp for fibronectin-binding proteins or antigen85) (63), some glycosylated proteins (Rpf proteins) (62), the outer membrane channel protein CpnT (63), and sphingomyelinase Rv0888 SpmT protein (64). Proteomic analysis confirmed the presence of Fbps and porins (MspA in the case of M. smegmatis) in the cell wall fraction, but also putative transporters, e.g., the mycobacterial cell entry protein family (31).

THE CAPSULE

The first mycobacterial capsules defined, namely, those of M. leprae and M. lepraemurium, were composed of lipids, but this turns out to be the exception. The fibrillar substance that surrounds M. lepraemurium inside the phagocytic vacuoles of the host cell (50) was composed of glycopeptidolipids (GPLs) (9), and massive amounts of phenolic glycolipids (PGLs) (Fig. 2) were isolated from cells infected with M. leprae (65, 66). However, both GPL-positive and GPL-negative strains of the M. avium-M. intracellulare complex elaborate capsules (67), indicating that the capsule is not always composed of lipids. Moreover, most strains of M. tuberculosis are devoid of PGL (68).

Knowing that in vitro-grown pathogenic mycobacterial species secrete abundant amounts of polysaccharides and proteins (69, 70), we postulated that the material shed into the culture medium of in vitro-grown mycobacteria is retained by the phagosomal membrane to form the electron-transparent zone seen around pathogenic species in phagocytic cells (9). Consistently, more extracellular material was recovered from the culture filtrates of the pathogenic species, e.g. M. tuberculosis (71) and M. kansasii (69), than from those of saprophytic and nonpathogenic strains such as M. smegmatis and M. aurum (69). Accordingly, the nature of the capsular constituents of various mycobacterial species were determined by analyzing the composition of their extracellular materials and those extracted by gentle shaking of bacterial pellicles with glass beads and/or by detergent extraction for short periods of time (34, 69, 72). Importantly, these treatments, aiming at de-clumping the cells, do not affect their viability, as judged by scanning electron microscopy (34, 70).

The main components of the outermost capsular layer of slow-growing mycobacterial species, most of which are pathogens (e.g., M. tuberculosis and M. kansasii), are polysaccharides (69, 70), whereas the major components of the outer layer of rapid growers (e.g., M. phlei and M. smegmatis) are proteins (69). The major extracellular and capsular component of slow-growing mycobacterial species is a glucan (Fig. 3) that is composed of repeating units of five or six α-(1→4) linked d-glucosyl residues substituted at position 6 with mono- or oligoglucosyl residues (69, 70, 71, 73). The surface-exposed and extracellular materials also contain a d-arabino-d-mannan, a heteropolysaccharide that exhibits an apparent molecular mass of 13 kDa, and a mannan chain composed of an α–(1→6)-d-mannosyl core, with some units substituted with α-d-mannose at position 2. Importantly, glucan was identified in the capsule of M. tuberculosis inside the phagocytic vacuoles of the host cell (74).

The outermost part of the mycobacterial cell envelope contains only a tiny amount of lipid (2 to 3% of the surface-exposed material). Some of the species- and type-specific lipids and glycolipids, e.g., phthiocerol dimycocerosate, PGL, and GPL, can be found on the surface of the capsule, in agreement with serological and ultrastructural findings (see 9). Progressive extraction of the capsular material with glass beads and short-time treatment with Tween 80 detergent shows that most of the lipids are in the inner rather than in the outer part of the capsule (34).

The outermost capsular proteins of in vitro-grown M. tuberculosis are a complex mixture of polypeptides (70). Some proteins seem to correspond to secreted polypeptides found in short-term culture filtrates, whereas others appear to be cell wall associated (29). In fact, most of the hundreds of proteins identified in the short-term culture filtrate of M. tuberculosis by two-dimensional SDS-PAGE (75) are also found in significant amounts in the surface-exposed material extracted by mild mechanical treatment of cells. This observation supports the concept that the compounds found in culture filtrates of in vitro-grown cells are probably shed from the surface of the bacilli and, in an in vivo context, would be confined around the cells in the capsular layer (9). Components of the early secretory antigen transport system were recently localized to the capsule by immuno-electron microscopy of cryosectioned mycobacteria (19).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The chemical structure of most of the core components of the mycobacterial cell envelope was determined a long time ago, establishing its extreme richness in lipid. However, it is only recently that a combination of CEMOVIS and whole-cell cryoEM has revealed the true structure of the mycobacterial cell envelope, i.e., the existence of a Gram-negative-like (diderm) outer membrane in these Gram-positive bacteria and an outermost capsular layer of protein and carbohydrate (Fig. 3). Determining the composition, localization, and supramolecular organization of the capsular and cell wall constituents and understanding how these factors make the envelope essential to M. tuberculosis survival, virulence, and pathogenesis remain major challenges. This will require synergistic expertise in analytical and structural biochemistry and biophysics to fill the gap in understanding the MM compartment by isolating and defining the full lipid and protein compositions of the capsule and cell wall. Deciphering the supramolecular organization of the capsule and MM-containing cell wall represent an additional exciting goal. The discovery of how mycobacteria select and organize their envelope constituents to resist killing should help decode the mechanisms involved in the mycobacterial pathogenicity and provide new potential targets for antituberculosis chemotherapy. In this respect, the biogenesis of MM constitutes a highly relevant and validated pharmaceutical target for antituberculosis drug discovery.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wayne LG, Kubica GP. 1986. The mycobacteria, p 1435–1457. In Sneath PHA, Mair NS, Sharpe ME, Holt JG (ed), Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Touchette MH, Seeliger JC. 2017. Transport of outer membrane lipids in mycobacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 1862:1340–1354 10.1016/j.bbalip.2017.01.005. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goren MB, Brennan PJ. 1979. Tuberculosis, p 63–193. In Youmans GP (ed), Mycobacterial Lipids: Chemistry and Biologic Activities. W.B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon SV, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry CE 3rd, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Krogh A, McLean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver K, Osborne J, Quail MA, Rajandream MA, Rogers J, Rutter S, Seeger K, Skelton J, Squares R, Squares S, Sulston JE, Taylor K, Whitehead S, Barrell BG. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393:537–544. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jankute M, Cox JAG, Harrison J, Besra GS. 2015. Assembly of the mycobacterial cell wall. Annu Rev Microbiol 69:405–423 10.1146/annurev-micro-091014-104121. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daffé M, Quémard A, Marrakchi H. 2018. Mycolic acids: from chemistry to biology. In Geiger O (ed), Biogenesis of Fatty Acids, Lipids and Membranes. Handbook of Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology Series. Springer, Cham, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chalut C. 2016. MmpL transporter-mediated export of cell-wall associated lipids and siderophores in mycobacteria. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 100:32–45 10.1016/j.tube.2016.06.004. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gröschel MI, Sayes F, Simeone R, Majlessi L, Brosch R. 2016. ESX secretion systems: mycobacterial evolution to counter host immunity. Nat Rev Microbiol 14:677–691 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.131. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daffé M, Draper P. 1998. The envelope layers of mycobacteria with reference to their pathogenicity. Adv Microb Physiol 39:131–203 10.1016/S0065-2911(08)60016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daffé M, Zuber B. 2014. The fascinating coat surrounding mycobacteria. p 179–192. In Remaut H, Fronzes R (ed), Bacterial Membranes: Structural and Molecular Biology, Caister Academic Press, Poole, UK. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zuber B, Chami M, Houssin C, Dubochet J, Griffiths G, Daffé M. 2008. Direct visualization of the outer membrane of native mycobacteria and corynebacteria. J Bacteriol 190:5672–5680 10.1128/JB.01919-07. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daffé M, Dupont MA, Gasc N. 1989. The cell envelope of Mycobacterium smegmatis: cytochemistry and architectural implications. FEMS Microbiol Lett 52:89–93 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1989.tb03558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silva MT, Macedo PM. 1983. A comparative ultrastructural study of the membranes of Mycobacterium leprae and of cultivable Mycobacteria. Biol Cell 47:383–386. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silva MT, Macedo PM. 1984. Ultrastructural characterization of normal and damaged membranes of Mycobacterium leprae and of cultivable mycobacteria. J Gen Microbiol 130:369–380. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silva MT, Macedo PM. 1983. The interpretation of the ultrastructure of mycobacterial cells in transmission electron microscopy of ultrathin sections. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis 51:225–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paul TR, Beveridge TJ. 1992. Reevaluation of envelope profiles and cytoplasmic ultrastructure of mycobacteria processed by conventional embedding and freeze-substitution protocols. J Bacteriol 174:6508–6517 10.1128/jb.174.20.6508-6517.1992. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paul TR, Beveridge TJ. 1994. Preservation of surface lipids and determination of ultrastructure of Mycobacterium kansasii by freeze-substitution. Infect Immun 62:1542–1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffmann C, Leis A, Niederweis M, Plitzko JM, Engelhardt H. 2008. Disclosure of the mycobacterial outer membrane: cryo-electron tomography and vitreous sections reveal the lipid bilayer structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:3963–3967 10.1073/pnas.0709530105. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sani M, Houben ENG, Geurtsen J, Pierson J, de Punder K, van Zon M, Wever B, Piersma SR, Jiménez CR, Daffé M, Appelmelk BJ, Bitter W, van der Wel N, Peters PJ. 2010. Direct visualization by cryo-EM of the mycobacterial capsular layer: a labile structure containing ESX-1-secreted proteins. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000794 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000794. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jarlier V, Nikaido H. 1990. Permeability barrier to hydrophilic solutes in Mycobacterium chelonei. J Bacteriol 172:1418–1423 10.1128/jb.172.3.1418-1423.1990. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niederweis M, Danilchanka O, Huff J, Hoffmann C, Engelhardt H. 2010. Mycobacterial outer membranes: in search of proteins. Trends Microbiol 18:109–116 10.1016/j.tim.2009.12.005. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chapman GB, Hanks JH, Wallace JH. 1959. An electron microscope study of the disposition and fine structure of Mycobacterium lepraemurium in mouse spleen. J Bacteriol 77:205–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanks JH. 1961. The problem of preserving internal structures in pathogenic mycobacteria by conventional methods of fixation. Int J Lepr 29:175–178. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanks JH. 1961c. Demonstration of capsules on M. leprae during carbol-fuchsin staining mechanism of the Ziehl-Neelsen stain. Int J Lepr 26:179–182. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanks JH, Moore JT, Michaels JE. 1961. Significance of capsular components of Mycobacterium leprae and other mycobacteria. Int J Lepr 29:74–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanks JH. 1961. Capsules in electron micrographs of Mycobacterium leprae. Int J Lepr 29:84–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fréhel C, Ryter A, Rastogi N, David H. 1986. The electron-transparent zone in phagocytized Mycobacterium avium and other mycobacteria: formation, persistence and role in bacterial survival. Ann Inst Pasteur Microbiol 137B:239–257 10.1016/S0769-2609(86)80115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryter A, Fréhel C, Rastogi N, David HL. 1984. Macrophage interaction with mycobacteria including M. leprae. Acta Leprol 2:211–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daffé M, Etienne G. 1999. The capsule of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and its implications for pathogenicity. Tuber Lung Dis 79:153–169 10.1054/tuld.1998.0200. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fréhel C, Rastogi N, Bénichou JC, Ryter A. 1988. Do test tube-grown pathogenic mycobacteria possess a protective capsule? FEMS Microbiol Lett 56:225–230 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1988.tb03182.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiaradia L, Lefebvre C, Parra J, Marcoux J, Burlet-Schiltz O, Etienne G, Tropis M, Daffé M. 2017. Dissecting the mycobacterial cell envelope and defining the composition of the native mycomembrane. Sci Rep 7:12807 10.1038/s41598-017-12718-4. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rezwan M, Lanéelle MA, Sander P, Daffé M. 2007. Breaking down the wall: fractionation of mycobacteria. J Microbiol Methods 68:32–39 10.1016/j.mimet.2006.05.016. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minnikin DE. 1982. Lipids: complex lipids, their chemistry, biosynthesis and roles, p 95–184. In Ratledge C, Stanford J (ed), The Biology of the Mycobacteria, vol. 1. Physiology, Identification and Classification. Academic Press, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ortalo-Magné A, Lemassu A, Lanéelle MA, Bardou F, Silve G, Gounon P, Marchal G, Daffé M. 1996. Identification of the surface-exposed lipids on the cell envelopes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other mycobacterial species. J Bacteriol 178:456–461 10.1128/jb.178.2.456-461.1996. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dhiman RK, Dinadayala P, Ryan GJ, Lenaerts AJ, Schenkel AR, Crick DC. 2011. Lipoarabinomannan localization and abundance during growth of Mycobacterium smegmatis. J Bacteriol 193:5802–5809 10.1128/JB.05299-11. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bansal-Mutalik R, Nikaido H. 2014. Mycobacterial outer membrane is a lipid bilayer and the inner membrane is unusually rich in diacyl phosphatidylinositol dimannosides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:4958–4963 10.1073/pnas.1403078111. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaur D, Guerin ME, Skovierová H, Brennan PJ, Jackson M. 2009. Chapter 2: biogenesis of the cell wall and other glycoconjugates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Adv Appl Microbiol 69:23–78 10.1016/S0065-2164(09)69002-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abrahams KA, Besra GS. 2016. Mycobacterial cell wall biosynthesis: a multifaceted antibiotic target. Parasitology 145:116–133. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kotani S, Kitaura T, Hirano T, Tanaka A. 1959. Isolation and chemical composition of the cells walls of BCG. Biken’s J 2:129–141. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Draper P. 1971. The walls of Mycobacterium lepraemurium: chemistry and ultrastructure. J Gen Microbiol 69:313–324 10.1099/00221287-69-3-313. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Puech V, Chami M, Lemassu A, Lanéelle MA, Schiffler B, Gounon P, Bayan N, Benz R, Daffé M. 2001. Structure of the cell envelope of corynebacteria: importance of the non-covalently bound lipids in the formation of the cell wall permeability barrier and fracture plane. Microbiology 147:1365–1382 10.1099/00221287-147-5-1365. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Daffé M, Brennan PJ, McNeil M. 1990. Predominant structural features of the cell wall arabinogalactan of Mycobacterium tuberculosis as revealed through characterization of oligoglycosyl alditol fragments by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry and by 1H and 13C NMR analyses. J Biol Chem 265:6734–6743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Daffé M, McNeil M, Brennan PJ. 1993. Major structural features of the cell wall arabinogalactans of Mycobacterium, Rhodococcus, and Nocardia spp. Carbohydr Res 249:383–398 10.1016/0008-6215(93)84102-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McNeil M, Daffé M, Brennan PJ. 1990. Evidence for the nature of the link between the arabinogalactan and peptidoglycan of mycobacterial cell walls. J Biol Chem 265:18200–18206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McNeil M, Daffé M, Brennan PJ. 1991. Location of the mycolyl ester substituents in the cell walls of mycobacteria. J Biol Chem 266:13217–13223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bhamidi S, Scherman MS, Jones V, Crick DC, Belisle JT, Brennan PJ, McNeil MR. 2011. Detailed structural and quantitative analysis reveals the spatial organization of the cell walls of in vivo grown Mycobacterium leprae and in vitro grown Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem 286:23168–23177 10.1074/jbc.M110.210534. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barksdale L, Kim KS. 1977. Mycobacterium. Bacteriol Rev 41:217–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Benedetti EL, Dunia I, Ludosky MA, Nguyen VM, Dang DT, Rastogi N, David HL. 1984. Freeze-etching and freeze-fracture structural features of cell envelopes in mycobacteria and leprosy derived corynebacteria. Acta Leprol 2:237–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chami M, Bayan N, Dedieu J, Leblon G, Shechter E, Gulik-Krzywicki T. 1995. Organization of the outer layers of the cell envelope of Corynebacterium glutamicum: a combined freeze-etch electron microscopy and biochemical study. Biol Cell 83:219–229 10.1016/0248-4900(96)81311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nguyen HT, Trach DD, Man NV, Ngoan TH, Dunia I, Ludosky-Diawara MA, Benedetti EL. 1979. Comparative ultrastructure of Mycobacterium leprae and Mycobacterium lepraemurium cell envelopes. J Bacteriol 138:552–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rulong S, Aguas AP, da Silva PP, Silva MT. 1991. Intramacrophagic Mycobacterium avium bacilli are coated by a multiple lamellar structure: freeze fracture analysis of infected mouse liver. Infect Immun 59:3895–3902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Draper P. 1998. The outer parts of the mycobacterial envelope as permeability barriers. Front Biosci 3:D1253–D1261 10.2741/A360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nikaido H, Kim SH, Rosenberg EY. 1993. Physical organization of lipids in the cell wall of Mycobacterium chelonae. Mol Microbiol 8:1025–1030 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01647.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Villeneuve M, Kawai M, Kanashima H, Watanabe M, Minnikin DE, Nakahara H. 2005. Temperature dependence of the Langmuir monolayer packing of mycolic acids from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1715:71–80 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.07.005. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Villeneuve M, Kawai M, Watanabe M, Aoyagi Y, Hitotsuyanagi Y, Takeya K, Gouda H, Hirono S, Minnikin DE, Nakahara H. 2007. Conformational behavior of oxygenated mycobacterial mycolic acids from Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Biochim Biophys Acta 1768:1717–1726 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.04.003. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Trias J, Benz R. 1993. Characterization of the channel formed by the mycobacterial porin in lipid bilayer membranes. Demonstration of voltage gating and of negative point charges at the channel mouth. J Biol Chem 268:6234–6240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trias J, Jarlier V, Benz R. 1992. Porins in the cell wall of mycobacteria. Science 258:1479–1481 10.1126/science.1279810. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Senaratne RH, Mobasheri H, Papavinasasundaram KG, Jenner P, Lea EJ, Draper P. 1998. Expression of a gene for a porin-like protein of the OmpA family from Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. J Bacteriol 180:3541–3547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Raynaud C, Papavinasasundaram KG, Speight RA, Springer B, Sander P, Böttger EC, Colston MJ, Draper P. 2002. The functions of OmpATb, a pore-forming protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol 46:191–201. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03152.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Teriete P, Yao Y, Kolodzik A, Yu J, Song H, Niederweis M, Marassi FM. 2010. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv0899 adopts a mixed alpha/beta-structure and does not form a transmembrane beta-barrel. Biochemistry 49:2768–2777. 10.1021/bi100158s. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Faller M, Niederweis M, Schulz GE. 2004. The structure of a mycobacterial outer-membrane channel. Science 303:1189–1192 10.1126/science.1094114. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hartmann M, Barsch A, Niehaus K, Pühler A, Tauch A, Kalinowski J. 2004. The glycosylated cell surface protein Rpf2, containing a resuscitation-promoting factor motif, is involved in intercellular communication of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Arch Microbiol 182:299–312 10.1007/s00203-004-0713-1. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Danilchanka O, Pires D, Anes E, Niederweis M. 2015. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis outer membrane channel protein CpnT confers susceptibility to toxic molecules. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:2328–2336. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Speer A, Sun J, Danilchanka O, Meikle V, Rowland JL, Walter K, Buck BR, Pavlenok M, Hölscher C, Ehrt S, Niederweis M. 2015. Surface hydrolysis of sphingomyelin by the outer membrane protein Rv0888 supports replication of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in macrophages. Mol Microbiol 97:881–897 10.1111/mmi.13073. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boddingius J, Dijkman H. 1990. Subcellular localization of Mycobacterium leprae-specific phenolic glycolipid (PGL-I) antigen in human leprosy lesions and in M. leprae isolated from armadillo liver. J Gen Microbiol 136:2001–2012 10.1099/00221287-136-10-2001. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hunter SW, Brennan PJ. 1990. Evidence for the presence of a phosphatidylinositol anchor on the lipoarabinomannan and lipomannan of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem 265:9272–9279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rastogi N, Lévy-Frebault V, Blom-Potar MC, David HL. 1989. Ability of smooth and rough variants of Mycobacterium avium and M. intracellulare to multiply and survive intracellularly: role of C-mycosides. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg A 270:345–360 10.1016/S0176-6724(89)80003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Daffé M, Lacave C, Lanéelle MA, Lanéelle G. 1987. Structure of the major triglycosyl phenol-phthiocerol of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (strain Canetti). Eur J Biochem 167:155–160 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb13317.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lemassu A, Ortalo-Magné A, Bardou F, Silve G, Laneélle MA, Daffé M. 1996. Extracellular and surface-exposed polysaccharides of non-tuberculous mycobacteria. Microbiology 142:1513–1520 10.1099/13500872-142-6-1513. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ortalo-Magné A, Dupont MA, Lemassu A, Andersen ÅB, Gounon P, Daffé M. 1995. Molecular composition of the outermost capsular material of the tubercle bacillus. Microbiology 141:1609–1620 10.1099/13500872-141-7-1609. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lemassu A, Daffé M. 1994. Structural features of the exocellular polysaccharides of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochem J 297:351–357 10.1042/bj2970351. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Raynaud C, Etienne G, Peyron P, Lanéelle MA, Daffé M. 1998. Extracellular enzyme activities potentially involved in the pathogenicity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiology 144:577–587 10.1099/00221287-144-2-577. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dinadayala P, Lemassu A, Granovski P, Cérantola S, Winter N, Daffé M. 2004. Revisiting the structure of the anti-neoplastic glucans of Mycobacterium bovis Bacille Calmette-Guerin. Structural analysis of the extracellular and boiling water extract-derived glucans of the vaccine substrains. J Biol Chem 279:12369–12378 10.1074/jbc.M308908200. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schwebach JR, Glatman-Freedman A, Gunther-Cummins L, Dai Z, Robbins JB, Schneerson R, Casadevall A. 2002. Glucan is a component of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis surface that is expressed in vitro and in vivo. Infect Immun 70:2566–2575. 10.1128/IAI.70.5.2566-2575.2002. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sonnenberg MG, Belisle JT. 1997. Definition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture filtrate proteins by two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, N-terminal amino acid sequencing, and electrospray mass spectrometry. Infect Immun 65:4515–4524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]