Summary

Many bacteria use operons to coregulate genes, but it remains unclear how operons benefit bacteria. We integrated E. coli’s 788 polycistronic operons and 1,231 transcription units into an existing whole-cell model, and found inconsistencies between the proposed operon structures and the RNA-Seq read counts that the model was parameterized from. We resolved these inconsistencies through iterative, model-guided corrections to both datasets, including the correction of RNA-Seq counts of short genes that were misreported as zero by existing alignment algorithms. The resulting model suggested two main modes by which operons benefit bacteria. For 86% of low-expression operons, adding operons increased the coexpression probabilities of their constituent proteins, while for 92% of high-expression operons, adding operons resulted in more stable expression ratios between the proteins. These simulations underscored the need for further experimental work on how operons reduce noise and synchronize both the expression timing and the quantity of constituent genes. A record of this paper’s Transparent Peer Review process is included in the Supplemental Information.

Keywords: Whole-cell modeling, operon, transcription unit structure, transcriptional regulation, mechanistic modeling, deep curation, RNA sequencing

eTOC blurb

To explore how operons benefit bacteria, Sun et al. update an E. coli whole-cell model to account for operons. In the process, they find inconsistencies between input datasets which they resolve through model-guided corrections. Simulations suggest that operons increase co-expression probabilities for low-expression genes, while stabilizing stoichiometries for high-expression genes.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Coregulation of genes through operons is a key mechanism that many organisms, mostly bacteria, have evolved to organize their transcriptomes. Since the discovery of the lac operon in E. coli1, many theories have been proposed on what selective advantages operons would bring to bacteria, as opposed to placing the same genes under the control of identical but independent promoters. Some have suggested that operons evolved solely because they facilitate simultaneous horizontal transfer of functionally related genes by placing them close together on the genome2,3 (the “selfish” operon theory); other suggestions include that operons provide a more information-efficient way to coregulate genes compared to alternative methods4, facilitate easier complexation between protein subunits5,6, or decrease gene expression noise7.

In the context of this debate, it should be noted that there is great diversity in the features of operons that have been characterized so far in bacterial genomes. In E. coli, for example, many operons consist of genes that are heavily regulated and only function under specific environments, with the lac operon being a prime example. However, many other operons consist of genes that are constitutively expressed, such as the spc operon, which consists of ten genes encoding for ribosomal proteins8. Some E. coli operons are “canonical” in the sense that they contain a single promoter and a single transcription terminator, and thus always express all genes in the operon as a single, contiguous transcription unit. Other operons have more complex transcription unit structures that include internal promoters and/or terminators, and can transcribe multiple mRNA isoforms that span different combinations of genes within the operon9–11. Given this diversity, it is unlikely that a single mechanism would explain the utility of all operons in E. coli, let alone all bacterial species.

In this work, we use the E. coli whole-cell model to investigate the role of operons in the regulation of gene expression dynamics. The long-term goal of the E. coli Whole-Cell Modeling Project is to build a mechanistic simulation of an E. coli cell that takes into account the known functions of all genes and molecules12, as once proposed by Francis Crick13. The key innovation that enabled the building of a model of such scale was the division of the cell into multiple, independent modules that each represent a particular biological process within the cell (metabolism, transcription, translation, etc.). Each module was then represented with a “submodel” that uses a mathematical framework that is most appropriate for the corresponding biological process, given the properties of the process itself and the level of knowledge or data we currently have about its dynamics (See STAR Methods for more details on whole-cell modeling concepts). Three years ago, a first version of the E. coli whole-cell model was reported, which integrated more than 19,000 parameters collected from hundreds of heterogeneous data sources, and mathematically represented the functions of 43% of the well-annotated genes of E. coli14. Whole-cell models have produced simulation outputs that were validated by experiments and have made predictions on emergent properties of the cells being modeled14–17.

Because of the inherent noisiness of bacterial gene expression and the resulting heterogeneity between individual bacterial cells, it has been challenging to understand the effects of operon structures via experimental methods. Thus, many studies that have previously explored this question have instead made use of mathematical models that simulate the stochastic expression of genes from bacterial promoters at the single-cell level. However, these studies either chose to model one specific operon18, or hypothetical operons with generalized parameters7,19,20, belying the aforementioned diversity in how operons operate within these cells. The E. coli whole-cell model allows us to quantitatively probe the gene expression dynamics for virtually all of the protein-coding operons in E. coli with their own specific parameters, providing a unique opportunity to explore this problem theoretically in both great breadth and detail. While experimental validation would still be necessary, this modeling approach allows us to run simulated experiments that would be prohibitively costly to conduct in a similar scale in an actual experimental setting, while also providing us with data on the fine-grained dynamics of gene expression at the level of individual cells that would not be possible to measure experimentally with the current technology. Consequently, by using the whole-cell model to explore this question, we are able to propose broad, genome-scale hypotheses on the utility of bacterial operons.

In order to use the E. coli whole-cell model for this particular purpose, however, we first need to update the model to account for E. coli’s operon structures. In the first published version of the whole-cell model14, it was assumed that each gene in E. coli is transcribed as its own, monocistronic transcription unit, largely because of difficulties in acquiring the experimental data that was needed to parameterize a model with polycistronic transcripts. More specifically, the model used two experimentally measured parameters to determine how frequently each mRNA species should be transcribed: the RNA-Seq read counts of the mRNA, and its degradation half-life (See STAR Methods for more details on the transcription submodel). Both of these numbers, however, are usually only reported at the level of individual genes and not at the level of longer polycistronic transcription units, due to technical limitations in the respective experimental methods used to acquire these data. Conventional short-read RNA-Seq protocols require the sample RNA to be digested into fragments that are shorter than most genes before they are sequenced, which leads to the loss of long-range context that was present in the original sample21,22, while degradation half-lives of mRNAs were taken from an experiment that used microarrays23, whose resolution is similarly limited to the gene level. Long-read RNA sequencing is a promising development that may be able to provide these types of measurements for polycistronic transcripts24,25, but the currently available data for E. coli is not comprehensive enough to be used for the whole-cell model.

While precise quantification of polycistronic transcripts at the omics level remains a challenge, our knowledge of operons and their transcription unit structures in the E. coli genome has expanded greatly since the discovery of the lac operon. Over many years, the curators at RegulonDB have compiled a list of all operons and transcription units that have been characterized so far in the E. coli genome26, and this compilation has been hosted and expanded as part of the EcoCyc database27. According to this list, we now have evidence that E. coli groups its 4,307 mRNA-encoding genes into 2,569 operons. 788 of these operons are polycistronic and are responsible for transcribing 2,526 (~59%) of the mRNA-encoding genes with 1,231 transcription units that span distinct combinations of genes. 521 of these polycistronic operons are canonical operons where all constituent genes are transcribed as a single transcription unit, while 267 operons have more complicated transcription unit structures. In addition to this list of transcription units curated by RegulonDB/EcoCyc, advanced RNA-Seq techniques were recently used to measure the degradation half-lives of a small subset of polycistronic transcripts at the level of the entire mRNA28, which provides us with some of the parameters necessary to model the degradation of these RNAs at the transcript level.

Thus, while direct measurement of all required parameters remains difficult, the availability of these additional datasets provides us with a starting point to build an updated version of the whole-cell model that accounts for operons (Figure 1A, “Heterogeneous data”). These additional datasets, combined with the data used by the first version of the whole-cell model14,23,29,30, are used to theoretically estimate a set of parameters that can describe gene expression at the level of individual transcription units, rather than individual genes (Figure 1A, “Simulation parameters”). These updated values populate the transcription submodel of the whole-cell model, which has been entirely reconfigured to handle the transcription of polycistronic mRNAs that cover multiple genes (Figure 1A, “Transcription submodel”). The rebuilt transcription submodel is connected with the other submodels to build the updated whole-cell model (Figure 1A, “E. coli whole-cell model”), which produces detailed simulations of E. coli growth while accounting for operons (Figure 1A, “Simulation outputs”). Figure 1B compares selected simulation outputs to illustrate the overall impact of this model update, with a focus on the expression of genes constituting the frdABCD operon, where each gene encodes for one of the four subunits of the fumarate reductase enzyme complex31. The original version of the model transcribed these four genes independently from each other as their own, monocistronic mRNAs (Figure 1B, left). The updated version transcribes the four genes of the operon as a single transcription unit, which then serves as a template to translate all four protein subunits, resulting in a more coordinated expression of the four proteins (Figure 1B, right).

Figure 1.

Additional experimental data gathered from multiple, heterogeneous sources were incorporated into the E. coli whole-cell model to simulate cells that transcribe polycistronic mRNAs. (A) Schematic representation of the data curation process that was used to update the whole-cell model. We incorporated additional data on E. coli’s transcription units into the existing whole-cell model, iteratively identified inconsistencies between the input data using the simulation outputs, and made guided corrections to the input data, which were verified through comparisons with independent data, to finalize an updated version of the E. coli whole-cell model that transcribes polycistronic mRNAs. (B) Comparison of the simulated expression dynamics of the frdABCD operon before and after the update.

Similar to our experience in building the original version of the E. coli whole-cell model, however, we find that a naïve integration of these additional datasets into the model results in unstable simulations that highlight inconsistencies between the input datasets. As the whole-cell model integrates heterogeneous experimental data that contain varying degrees of errors into a cohesive, unified model, the resulting model outputs can reveal conflicts between these datasets that would not be apparent when these datasets are analyzed independently from each other. In previous works, we had shown that we can use the whole-cell model’s outputs to identify these conflicts between input datasets and make model-guided corrections to these datasets to make them more cross-consistent – a process that we call “deep curation”12,14 (See STAR Methods for more details on deep curation). In this work, we similarly use the outputs from the updated whole-cell model to make guided corrections to the transcription unit structures curated by RegulonDB/EcoCyc and the RNA-Seq read counts (Figure 1A). To verify these corrections, we use data from Rend-seq32, a recently developed RNA sequencing technique that can identify transcription start and end sites, and data from Dar and Sorek33, which provide a list of E. coli operons whose mRNAs undergo nonuniform degradation.

The details on how we iteratively used the model’s outputs to make guided adjustments to the input data, with the goal of improving the data’s cross-consistency and the overall coherence of the simulated outputs, will be the focus of the first half of this work (Figure 1A). The second half will describe the final, conflict-resolved version of the updated model that includes operon structures and compare its outputs against the original version of the model that does not use operons (Figure 1B is a preview). Our simulated comparisons suggest two major modes by which operons can benefit bacterial cells. For low-expression genes, operons increase the probability that their constituent genes are co-expressed both at the mRNA and protein levels, which has an impact on the phenotypic properties of the colony if the genes are functionally dependent on each other. For genes that are more highly expressed, operons help ensure that the stoichiometries between the proteins that are expressed from the same operon remain more stable through time, therefore reducing the wasteful production of excess proteins.

Results

Longer doubling times of simulated cells with operons suggested an alternative transcription unit structure for the rplKAJL-rpoBC operon

The key to constructing a whole-cell model that accounts for operons and polycistronic transcripts was finding a way to use the available data to estimate the two required parameters – (i) RNA-Seq read counts (or equivalently, relative RNA copy numbers) and (ii) degradation half-lives – at the level of individual transcripts. For relative RNA copy numbers, we achieved this by assuming that the RNA-Seq read counts measured for each gene must be similar to the sum of the hypothetical read counts of all transcription units that the gene is a part of. From this assumption, we were able to construct a linear system of equations for each operon that, when solved, would yield a set of values for the transcript-level counts that are most consistent with the measured gene-level RNA-Seq read counts (Figure 2A, see STAR Methods for more details). We used a similar approach to estimate a consistent set of transcript-level degradation rate constants from the gene-level degradation rate constants (Figure S1A, see STAR Methods for more details).

Figure 2.

Longer doubling times of simulated cells with operons suggested an alternative transcription unit structure for the rplKAJL-rpoBC operon. See also Figure S1. (A) An example of how gene-level RNA-Seq read counts were translated into transcript-level RNA-Seq read counts using transcription unit (TU) structures and nonnegative least squares (NNLS). (B) Comparison of simulated doubling times in rich media conditions between simulations with and without operons after the initial integration of transcription unit structures from RegulonDB/EcoCyc. Simulations with operons had longer doubling times on average (38.3 ± 4.9 mins, n=964, where n is the number of simulated cells with fully completed cell cycles) compared to simulations without operons (27.2 ± 11.1 mins, n=999). (C) Comparison of mean mRNA copy numbers for genes encoding for subunits of RNAPs and ribosomes in rich media conditions between the two simulations. Copy numbers were calculated by averaging the copy numbers from the first timesteps of simulated cells with fully completed cell cycles, excluding cells from the first two generations (n=743 for simulations without operons, n=715 for simulations with operons). (D) The transcription unit structure for the rplKAJL-rpoBC operon suggested by RegulonDB/EcoCyc. This transcription unit structure was not cross-consistent with the RNA-Seq read counts of the genes in the operon. (E) Rend-seq data for the rplKAJL-rpoBC operon32. A 3’-end peak is clearly visible downstream of gene rplL (arrow), suggesting the existence of a transcriptional terminator that is missing from RegulonDB/EcoCyc. Other 5’-end and 3’-end peaks in the Rend-seq data align well with existing promoters/terminators in RegulonDB/EcoCyc. (F) Additional transcription units (red) proposed for the rplKAJL-rpoBC operon based on Rend-seq data. The addition of these transcription units allows the NNLS algorithm to find a solution that aligns better with the gene-level RNA-Seq read counts. (G) Comparison of mean mRNA copy numbers for genes encoding for subunits of RNAPs and ribosomes in rich media conditions after adding the two transcription units suggested by Rend-seq data. Copy numbers were calculated by averaging the copy numbers from the first timesteps of simulated cells with fully completed cell cycles, excluding cells from the first two generations (n=743 for simulations without operons, n=731 for simulations with operons). (H) Comparison of simulated doubling times in rich media conditions after adding the two transcription units. Simulations with operons had doubling times (28.2 ± 8.1 mins, n=981, where n is the number of simulated cells with fully completed cell cycles) that are similar to simulations without operons (27.2 ± 11.1 mins, n=999).

When we integrated the structures of the 1,231 RegulonDB/EcoCyc mRNA transcription units to the whole-cell model using this method, we observed that the simulation’s doubling time increased compared to the doubling time of the original model in both rich media (Figure 2B) and glucose minimal media conditions (Figure S1B; STAR Methods). Our previous experience with the whole-cell model suggested that longer simulated doubling times most often result from insufficient expression of the two main production machineries of the cell: RNA polymerases (RNAPs) and ribosomes14. Thus, we started by comparing the mean gene-level copy numbers of mRNAs that encode for the protein subunits of RNAPs and ribosomes before and after transcription unit structures were integrated into the model in both media conditions (Figure 2C and Figure S1C; STAR Methods). While most copy numbers were similar between the two sets of simulations, three genes (rpoB, rpoC, rplJ) that are part of the same 6-gene operon (rplKAJL-rpoBC) were differentially expressed between the two sets. Among these three genes, rpoB and rpoC each encode for the and ’ subunits of the E. coli RNA polymerase, which together take up 80% of the total mass of the core enzyme34. The rplJ gene encodes for the L10 protein, which is an essential component of the 50S ribosomal subunit of E. coli35.

According to the data from RegulonDB/EcoCyc, four distinct transcription units are responsible for expressing the six genes of the rplKAJL-rpoBC operon, each spanning different combinations of genes within the operon (Figure 2D). The database cites three publications36–38 as evidence supporting the existence of these transcription units. The gene-level RNA-Seq read counts for this operon, on the other hand, suggests that the four upstream genes of the operon (rplK, rplA, rplJ, rplL) have higher mRNA copy numbers compared to the two downstream genes (rpoB, rpoC). In order for the transcription unit structures to be consistent with these patterns in RNA-Seq read counts, there must exist transcription units that collectively span the four upstream genes but not the two downstream genes, thereby allowing the four upstream genes to be expressed at a higher level than the two downstream genes. The RegulonDB/EcoCyc database lists no such transcription units for this operon, which imposes a constraint to the expression stochiometries of this operon that is not consistent with the gene-level RNA-Seq counts. In the updated simulations with operons, the NNLS algorithm tried to find the best solution for the expression levels of each transcription unit within these constraints, but the calculated values led to an over-expression of the downstream rpo genes and under-expression of the upstream rpl genes, which in turn led to unbalanced counts of RNAPs and ribosomes, and ultimately, the longer doubling times.

This inconsistency between the RNA-Seq data and transcription unit structures was likely caused by errors that are inherent in both of these datasets. In the case of the rplKAJL-rpoBC operon, however, it was difficult to assume that the RNA-Seq read counts for the constituent genes contained large errors, as these expression levels were necessary for the model to produce the required levels of RNAPs and ribosomes and attain balanced growth. Given these considerations, we found it more likely that there is an alternative transcription unit structure for this operon that better aligns with the RNA-Seq measurements for these genes, the required RNA polymerase and ribosome counts, and in turn, the known growth rates of E. coli under these conditions. Since sufficiently complex transcription unit structures (in the extreme case, a transcription unit structure where each gene is transcribed as its own single-gene transcription unit) can always be fit to be perfectly consistent with an arbitrary array of RNA-Seq read counts, overfitting was a concern when we sought out to correct the transcription unit structure for this operon. Thus, we also searched for an independent experimental dataset (i.e. data that was not part of the input data for the whole-cell model) that could verify this alternative transcription unit structure. One such dataset came from a recently developed RNA sequencing technique called Rend-seq32, which had not been considered by the curators at RegulonDB or EcoCyc in building their list of transcription units, and which we had also not used to build our model. In Rend-seq, the 5’ and 3’-ends of RNA molecules are selectively enriched before they are sequenced, allowing us to identify the locations of these 5’ and 3’-ends in the form of “peaks” when aligned read counts are plotted against genomic positions. From this Rend-seq dataset, which was taken from E. coli cells growing exponentially in rich media (MOPS complete media), we observed that the rplKAJL-rpoBC operon had a clear peak for 3’-ends of mRNAs at the downstream end of gene rplL, which suggested that some of the transcripts for this operon have a 3’-end in this intergenic region under these growth conditions (Figure 2E, see arrow; STAR Methods). While the RegulonDB/EcoCyc dataset listed a single-gene transcription unit (rplL, TU08464) that uses this 3’-end, the two other possible 5’-3’ end combinations that utilize this site – transcription units rplKAJL and rplJL – were missing from the dataset (Figure 2F). Moreover, Ralling and Lin (1984), whom the database cites as evidence for the rplL transcription unit, pointed to an earlier work39 that suggested the existence of a transcriptional attenuator between the genes rplL and rpoB, providing further evidence that some transcripts of this operon should terminate at this site.

We postulated that the addition of these two transcription units would be able to address the discrepancy between the transcription unit structures and the RNA-Seq read counts for this operon by providing a means for the operon to independently express the four upstream genes with higher RNA-Seq counts without expressing the two downstream genes. Indeed, the inclusion of these two transcription units to the original list restored the simulation’s RNA copy numbers for RNAP and ribosomal genes to levels that were comparable to the original simulations in both rich media (Figure 2G) and minimal media conditions (Figure S1D). With these recovered counts, the cells simulated by the updated model were also able to grow at comparable doubling times as the original simulations in both media conditions (Figure 2H and Figure S1E), providing further support for our decision to include these transcription units. This demonstrated the whole-cell model’s unique ability to identify errors in existing databases such as EcoCyc and make correct predictions concerning both termination sites and transcription unit architectures via deep curation.

Integration of transcription unit structures revealed short genes whose read counts were falsely reported as zero in RNA-Seq data, but confirmed to be nonzero in experimental data

Encouraged by these results from a single operon, we decided to compare the gene-level RNA copy numbers of all other mRNA-encoding genes that are part of polycistronic operons, between the original model and the updated model (i.e., for which the two additional transcription units were added to the rplKAJL-rpoBC operon) (Figure 3A, STAR Methods). In this comparison, 14 genes immediately stood out, as these genes had zero mRNA expression in our original model without operons, but had nonzero expression after including operon structure (Figure 3A, black arrow and shaded oval). These genes had zero expression in our original version of the model because the RNA-Seq data reported zero read counts of their cognate mRNAs. When we added operon structures to the model, however, the model started expressing some of these genes as part of polycistronic transcription units, alongside adjacent genes that have nonzero RNA-Seq read counts. Considering the model output, we observed that all of the genes with zero read counts were very short (<100 nucleotides). This observation led us to investigate the commonly-used software package for RNA-Seq data processing that was applied to this dataset (RSEM40), which by default reports the read counts of these short genes as zero due to a known limitation of the algorithm. Specifically, to correct for biases that arise as more RNA reads are mapped to longer genes, the algorithm uses the “effective” length of each gene, which is approximately equal to the length of the gene subtracted by the mean length of the sequenced RNA fragments, to normalize the raw counts of aligned sequences to each gene (Figure 3B). In the rare case where the gene length is shorter than the mean length of sequenced fragments, however, the effective length of the gene is negative, and the algorithm sets the read counts to zero for these genes to avoid further computational complications. For most RNA-Seq studies, the RNA fragments used in the final sequencing step are 200–500 nucleotides long41. While other RNA-Seq data processing algorithms use different formulas to account for other sources of bias when computing the effective length of each gene42,43, the issue with short genes having expression levels artificially set to zero still persists in these algorithms.

Figure 3.

Expanded investigations into the simulated outputs suggested more corrections to the input datasets. See also Figure S2. (A) Comparison of mean RNA copy numbers for mRNA genes that are part of polycistronic operons between simulations with and without operons in rich media conditions. Copy numbers were calculated by averaging the copy numbers from the first timesteps of simulated cells with fully completed cell cycles, excluding cells from the first two generations (n=743 for simulations without operons, n=731 for simulations with operons). Genes that have the top 5% largest values of , where is the t-statistic between the two distributions of RNA copy numbers, are highlighted in red. The shaded oval highlights genes whose RNA copy numbers were zero in simulations without operons, but nonzero in simulations with operons. (B) Schematic representation of how read counts are calculated in standard RNA-Seq protocols. (C) The transcription unit structure and the RNA-Seq read counts of the appCBXA operon, where the RNA-Seq read count of gene appX is reported as zero because of its short length. (D) Schematic representation of how the read counts of the appX mRNA were estimated from the transcription unit structure of the operon, and the RNA-Seq read counts of other genes in the operon. (E) Schematic representation of the manual alignment algorithm used to more correctly estimate the read counts of short genes. (F) Comparison of mean RNA-Seq read counts of 14 short genes in simulated cells, both simulated with (n=762) and without (n=768) operons, versus their read counts estimated from the manual alignment algorithm, averaged across multiple RNA samples (n=3). (G) Schematic representation of how adding a transcription unit spanning the stable genes of an operon could lead to a more accurate representation of the operon’s mRNA stoichiometries. (H) The distribution of the maximum values of among constituent genes for operons that had a transcription unit covering the stable genes in RegulonDB/EcoCyc (left), operons that did not have such a transcription unit (middle), and the same operons after adding the transcription unit covering the stable genes (right). (I) The transcription unit structures and the gene-level RNA-Seq read counts reported for the oppABCDF operon (top) and the Rend-seq data for the same operon32 (middle). Based on the existence of the 3’-end (arrow) downstream of gene oppA in the Rend-seq data, we added an additional transcription unit (oppA, red) to the operon (bottom). (J) The transcription unit structures and the gene-level RNA-Seq read counts reported for the cmk-rpsA-ihfB operon (top) and the Rend-seq data for the same operon32 (middle). Based on the existence of the 5’-ends and 3’-end (arrows) surrounding the gene rpsA in the Rend-seq data, we added an additional transcription unit (rpsA, red) to the operon (bottom).

From a biological perspective, however, many of these short genes should have nonzero expression since their products are known to serve clear functional roles in their respective operons. The appX gene, for example, encodes for an accessory subunit of the cytochrome bd-II protein complex, whose other subunits are encoded by other genes in the same operon44 (appB and appC), but its RNA read counts are reported as zero due to its short length (93nt, Figure 3C). Five of these short genes with zero read counts (hisL, pheL, trpL, thrL, leuL) encode for leader transcripts in amino acid biosynthesis operons and are responsible for regulating the transcription of the entire operon based on the availability of the amino acid through transcriptional attenuation45,46. Thus, for these 14 genes, we presumed that these errors in the calculation of RNA-Seq read counts were the primary sources for the discrepancies we were observing between RNA-Seq data and transcription unit structures.

While it was clearly a step in the right direction that the updated simulations were transcribing these genes at nonzero levels, because the simulations were using the read counts of zero for these genes to calculate transcript-level read counts for these operons, this computational artifact was still affecting the simulation’s outputs. Thus, for the purpose of calculating the most accurate parameters for the model, we chose to infer the normalized RNA-Seq read counts (TPMs) for these short genes from the relatively more reliable data we had in store – the transcription unit structure of the operon that contains the gene, and the more accurately processed read counts of the longer genes in the same operon. We constructed a similar NNLS problem for these operons with short genes, but we excluded the short gene entirely from matrix and the vector of RNA-Seq read counts. After using NNLS to solve this reduced problem, we multiplied the solution back to the original matrix constructed for the full operon. The resulting vector gave us the approximate RNA-Seq read count for the problematic short gene that best aligns with the known transcription unit structures and the RNA-Seq read counts of other genes in the operon (Figure 3D). Using this method, we made corrections to the RNA-Seq read counts of the 14 genes and ran a new batch of simulations that uses these corrected read count values to calculate the transcript-level read counts. These updated simulations were used for comparisons in the following analyses.

To experimentally validate the nonzero expression levels we were observing for these short genes in our simulations, we went back to the raw paired-end sequencing read data14 that was used by the alignment algorithm to calculate the gene-level RNA-Seq read counts. Instead of using RSEM, we manually compared the raw reads to the sequences of the short genes through a custom algorithm (Figure 3E, see STAR Methods for details). In this algorithm, the paired-end reads were first decoupled into two 75-nucleotide-long reads and each read was treated as a single-read sequence, since the genes in question were too short to span both ends of a paired-end read. Next, the decoupled reads were individually compared to the known sequences of the 14 short genes, in search for reads that have perfect alignments to the gene sequences. For each of the 14 genes, we counted the number of reads that had matching sequences to the gene, and normalized these counts with the absolute differences between the length of each gene and the reads (75nt). Using this custom algorithm, we could verify the existence of RNA reads in our original sample that perfectly match the reference sequences of 11 of the 14 short genes, confirming that these genes are transcribed but are not correctly accounted for by the RSEM algorithm (Figure 3F, y-axis; See Table S1 for full data). When we run our simulations with the corrected RNA-Seq counts for these genes and with operon structures, the normalized RNA copy numbers roughly align with these experimentally estimated RNA read counts, with RNA copy numbers of most genes falling within an order of magnitude of the experimentally estimated counts (Figure 3F).

Transcription unit structures with computational evidence codes were more cross-consistent with the RNA-Seq data than those with experimental evidence codes

Curators at EcoCyc use “evidence codes” to tag each of the curated transcription units to specify what type of evidence was used to infer the existence of the given transcription unit47. Two transcription units (rplKAJL-rpoBC and rplJL-rpoBC) of the rplKAJL-rpoBC operon that we have previously discussed, for example, are tagged with the evidence code EV-EXP-IMP-POLAR-MUTATION, indicating that these transcription units were inferred from experiments that look for polar effects, where a mutation in an upstream gene or promoter affects the expression of downstream genes in the same transcription unit, which was the method that was used to discover the lac operon1. In total, EcoCyc uses 20 distinct evidence codes to tag the 3,014 mRNA transcription units used in our model. 2,554 transcription units have at least one evidence code, while two or more codes are tagged to 399 transcription units. Table 1 lists the descriptions for the 20 evidence codes.

Table 1.

List of evidence codes used by EcoCyc to tag transcription units (TUs), sorted by the number of polycistronic operons with constituent transcription units that are tagged to the evidence code. Note that the evidence codes are grouped into classes based on the second word in each code: “EXP” = experimental evidence, “COMP” = computational evidence, “IC” = inferred by database curator.

| Evidence code | Description | # of tagged TUs | # of polycistronic operons w/ tagged TUs |

|---|---|---|---|

| EV-COMP-AINF | Automated inference from computational evidence48 | 1447 | 392 |

| EV-EXP-IDA-TRANSCRIPT-LEN-DETERMINATION | Inferred from experimentally measured transcript lengths | 606 | 161 |

| EV-EXP-IDA-BOUNDARIES-DEFINED | Inferred from sites or genes bounding the transcription unit that have been experimentally identified | 675 | 156 |

| EV-EXP-IEP-COREGULATION | Inferred from the existence of adjacent genes that are transcribed in the same direction and exhibit similar expression patterns under a range of environmental conditions | 226 | 144 |

| EV-EXP-IMP-POLAR-MUTATION | Inferred from experiments demonstrating polar effects | 168 | 97 |

| EV-IC-ADJ-GENES-SAME-BIO-PROCESS | Inferred from the existence of adjacent genes that are transcribed in the same direction and encode for products used in the same biological process | 115 | 71 |

| EV-EXP-IEP | Inferred from expression patterns (e.g. northern blots, microarrays) | 106 | 58 |

| EV-IC | Inferred by curators from relevant information such as other assertions in a database | 70 | 31 |

| EV-COMP-HINF | Human inference from computational evidence48 | 71 | 21 |

| EV-EXP-IDA | Inferred from a direct experimental assay | 4 | 3 |

| EV-AS-NAS | Inferred from a non-traceable author statement without a reference to the publication supporting the assertion | 4 | 3 |

| EV-AS-TAS | Inferred from a traceable author statement that references another publication supporting the assertion, but it is unclear whether the reference describes an experiment that supports the assertion | 4 | 3 |

| EV-COMP-AINF-SINGLE-DIRECTON | Automated inference based on a single-gene directon76, where a single gene is transcribed in the opposite direction from its upstream and downstream genes | 441 | 2 |

| EV-COMP-IBA | Inferred from characterization of an ancestral gene | 1 | 1 |

| EV-AS-HYPO | Inferred from an author hypothesis, without clear experimental evidence supporting the hypothesis | 1 | 1 |

| EV-ND | No biological evidence data available | 1 | 1 |

| EV-EXP-TAS | Inferred from a traceable author statement that references another publication describing an experiment supporting the assertion | 3 | 1 |

| EV-HTP-HEP | Inferred from high-throughput expression pattern | 1 | 1 |

| EV-EXP | Inferred from experiment | 1 | 1 |

| EV-EXP-IMP | Inferred from mutant phenotypes | 10 | 0 |

Using the comparison from Figure 3A, we tried to identify whether any of these evidence codes are associated with better or worse cross-consistency to the RNA-Seq data than others. For each gene, we took the distributions of mRNA copy numbers from each set of simulations and calculated the absolute value of the t-statistic that quantifies how different the two distribution means are from each other (STAR Methods). We chose to use the t-statistic to quantify this difference, instead of the absolute difference or fold-change, because each gene has distinct single-cell level variations in their mRNA copy numbers that affect the statistical significance of the differences between the means. Then, for each polycistronic operon, we selected the maximum value of among the genes within the operon, which we used as a metric for how cross-consistent the transcript unit structure of the operon is to the RNA-Seq dataset. A high value of meant that the expression levels of one or more genes within the operon changed substantially with the integration of transcription unit structures, indicating a high level of conflict between the transcription unit structures and the RNA-Seq read counts. For each operon, we also compiled the list of all evidence codes that were tagged to the transcription units that belong to the operon. This allowed us to map each evidence code to a collection of values, where each comes from a polycistronic operon whose transcription unit(s) were tagged with the given evidence code. We excluded operons that contain short genes with corrected RNA-Seq read counts, to focus on the cross-consistency of the transcription unit structures.

Figure S2A compares the log-transformed distributions of maximum values that are associated with each evidence code. Among the 20 evidence codes that were used by EcoCyc, we excluded the 11 codes that were associated with less than 10 operons. Among the remaining 9 evidence codes, the code EV-COMP-HINF, which indicates that the transcription units were derived from “human inference from computational evidence”, had the lowest median value of indicating that operon structures with this code, generally speaking, have a better cross-consistency to the RNA-Seq read counts. However, some evidence codes, namely EV-EXP-IMP-POLAR-MUTATION and EV-EXP-IDA-BOUNDARIES-DEFINED, which indicate that the transcription units were evidenced from polar effects and experimentally-defined transcription boundaries, respectively, were associated with higher values of . The association of multiple (≥2) evidence codes to a single operon did not lead to an improvement in cross-consistency (Figure S2B), suggesting that the quantity of evidence codes matters less than the type of evidence. While these distributions of values, in many ways, fall short of being a perfect measure of the underlying accuracy of these computational/experimental methods, our analyses demonstrated that certain types of evidence for the existence of transcription units were better than others in terms of their cross-consistency to the RNA-Seq data using this metric. We speculate that computational methods – like the sequence-based prediction algorithm used by EcoCyc48 – fare better than experimental methods in this metric because computational methods provide a more complete coverage of the transcription units of each operon, whereas experimental methods often focus on specific transcription units or promoter/terminator sites, and thus are more prone to under-representing the transcription unit structure for a particular operon.

Transcription unit structures for operons with differential mRNA decay were altered to accommodate changes in RNA stoichiometries

Some E. coli operons have been shown to undergo differential mRNA decay, where certain positions of an mRNA molecule transcribed from the operon are more stable than others33. This results in the genes that reside in the stable portions of the mRNAs to have higher RNA-Seq read counts than the genes outside of the stable portions, even if all genes are initially transcribed with equal stoichiometries. In the current version of our whole-cell model, we make the simplifying assumption that all mRNAs are degraded uniformly across all positions. While for many E. coli operons this assumption would be fairly accurate, there are 47 E. coli operons whose gene expression levels were shown to be affected by differential mRNA degradation33. For these operons, there is a boundary between genes where the mRNA is relatively stable on one side and unstable on the other side, leading to genes on the stable side to have higher expression levels at equilibrium compared the genes on the unstable side. If we assume that mRNAs degrade uniformly for these operons, the genes with stable mRNAs would be underexpressed while genes with unstable mRNAs would be overexpressed in the resulting simulations. Thus, we explored whether our simplifying assumption on mRNA degradation is affecting the expression levels of these 47 operons and leading to the discrepancies between RNA copy numbers that we observed in Figure 3A.

We first noted that 8 of 47 of these operons have transcription units listed on RegulonDB/EcoCyc that cover the genes residing on the stable portions of the mRNAs of these operons. When a transcription unit exists for these relatively more stable genes, it allows for the whole-cell model to have relatively higher expression levels for these genes compared to the unstable genes, without the need for a more complicated representation of mRNA degradation (Figure 3G). Indeed, for these 8 operons, the maximum absolute value of the t-statistic of their genes that quantifies how different the mRNA expression levels are between simulations with and without operons, were all outside of the top 5% highest values of among all genes that are part of polycistronic operons (; Figure 3H, left). Among the 39 operons for which RegulonDB/EcoCyc did not list transcription units covering the stable portions, 8 operons had genes with values of higher than or equal to this threshold (Figure 3H, middle), indicating there were substantial discrepancies between the proposed transcription unit structures and RNA-Seq read counts. For these operons, we concluded that our erroneous assumption about the degradation kinetics of mRNAs were responsible for the discrepancies between the expected mRNA copy numbers from RNA-Seq data (mRNA copy numbers in simulations without operons) and the actual mRNA copy numbers after accounting for transcription unit structures (mRNA copy numbers in simulations with operons).

Based on this conclusion, we chose to add to the model the transcription units that span the stable portions of these 8 operons, in order to help the model achieve higher relative expression levels for these genes. We only made corrections to these 8 operons with the most severe discrepancies to steer away from overfitting transcription unit structures to RNA-Seq read counts, which may also contain errors. When we run simulations with these additional transcription unit structures for these operons, the values for all but one operon fall below the threshold (Figure 3H, right), indicating that the discrepancies were indeed primarily caused by a lack of means for the model to express these genes at relatively higher levels compared to the other genes in the operon. While it would have been ideal for us to implement a more complicated mRNA degradation model that can handle position-dependent degradation for these operons, this was impractical, primarily due to the lack of high-quality quantitative data on the kinetics of these position-selective degradation mechanisms. Adding the stable portions of the operons as their own transcription units allowed us to achieve the uneven stoichiometries of mRNAs transcribed from the operons without using less well-characterized mechanisms of degradation.

Expanded investigation into data discrepancies suggested alternative transcription unit structures for 34 operons

Next, we tried to identify cases similar to the rplKAJL-rpoBC operon, where alternative data sources would suggest an adjusted transcription unit structure that is more consistent with the RNA-Seq data. Again, to select for operons with substantial discrepancies between the transcription unit structure and RNA-Seq data, we chose genes with the top 5% highest values of among genes that are part of polycistronic operons (; Figure 3A), which returned a list of 64 operons that contain one or more of these high- genes. Any operons containing short genes whose RNA-Seq read counts were already adjusted, or whose mRNAs have been shown to undergo differential degradation33 were excluded from this list. For each of these 64 operons, we checked the Rend-seq data for evidence of additional transcription units that RegulonDB and EcoCyc did not include in their dataset (Figure 3G).

Among these 64 operons, 34 (53%) operons had Rend-seq data32 that supported an alternative transcription unit structure that better aligns with the RNA-Seq data. One example is the oppABCDF operon, whose constituent genes encode for subunits of the oligopeptide transporter Opp49. For this operon, RegulonDB/EcoCyc listed two transcription units, one of which covered all five genes of the operon (oppABCDF) and another that covered the four downstream genes (oppBCDF). When we ran simulations without operon structures, which directly uses RNA-Seq read counts to determine RNA copy numbers, the oppA gene had a higher mean RNA copy number compared to the other genes of the operon, as a result of the oppA gene having a higher read count compared to the other genes (Figure 3H, top). This directly contradicted the RegulonDB/EcoCyc-listed transcription unit structure for this operon, since oppA cannot have a higher expression level compared the other genes with the two given transcription units. Indeed, the Rend-seq data for this operon suggested a 3’-end downstream of gene oppA, which implied the existence of another transcription unit that consists of just the gene oppA (Figure 3H, middle, see arrow). Based on this information, we added an additional transcription unit (oppA) for this operon that uses this 3’-end to our updated simulations (Figure 3H, bottom).

A slightly more complex example was the cmk-rpsA-ihfB operon, where a high-expression gene encoding for a ribosomal protein (rpsA) is flanked by two genes that are expressed in relatively smaller amounts (Figure 3I, top). RegulonDB/EcoCyc listed three transcription units for this operon, one spanning the first two genes (cmk-rpsA), another spanning the last two genes (rpsA-ihfB), and one covering just the last gene (ihfB). While this transcription unit structure would be able to support higher expression of rpsA compared to the other genes, the RNA copy numbers for rpsA cannot be greater than the sum of the RNA copy numbers of cmk and ihfB, since every copy of rpsA transcribed leads to either a copy of cmk or ihfB. In simulations without operon structures, however, the RNA copy number of rpsA (206.4) was nearly an order of magnitude greater than the sum of the RNA copy numbers of cmk and ihfB (27.4). This strongly suggested the existence of a transcription unit for this operon that can independently express rpsA without expressing either cmk or ihfB. Indeed, the Rend-seq data for this operon suggested multiple 5’-end and 3’-end sites flanking the middle gene, which supported the existence of a transcription unit that covers just the gene rpsA (Figure 3H, middle, see arrows). Based on these data points, we decided to add an additional transcription unit (rpsA) for this operon in our updated simulations (Figure 3I, bottom).

Table S2 fully lists the 64 operons and gives details of how the data discrepancy for each operon was addressed. Again, being conscious of the possibility of overfitting, we only added additional transcription units to address the discrepancy if (i) there was a sizeable level of inconsistency () between RNA-Seq read counts and transcription unit structures for the given operon, (ii) Rend-seq data clearly supports that the transcription unit to be added exists, and (iii) adding the transcription unit directly addresses the conflict between the original two datasets. This process led us to add 38 transcription units to 34 operons, in addition to the 1,231 transcription units that were sourced from RegulonDB/EcoCyc, the 2 transcription units that were added to the rplKAJL-rpoBC operon, and 8 transcription units added for operons with position-dependent degradation. We used this finalized version of the updated whole-cell model, with a total of 1,279 transcription units within 788 polycistronic operons, for comparisons in the following analyses. This final version of the updated whole-cell model, together with all intermediate versions, is available through our public GitHub repository (see STAR Methods, Key Resources Table).

Key resources table.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Deposited data | ||

| Rend-seq data | Lalanne et al., 2018 | GEO (accession number: GSE95211) |

| Raw RNA-Seq reads for manual alignment | Macklin et al., 2020 | GEO (accession number: GSE85472) |

| EcoCyc v26.5 | Keseler et al., 2021 | https://ecocyc.org |

| Read counts for short genes calculated by the manual alignment algorithm | This paper | Table S1 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Updated E. coli whole-cell model | This paper | https://github.com/CovertLab/wcEcoli/tree/operon-paper (Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10553485) |

| Rend-seq analysis scripts | This paper | https://github.com/CovertLab/Rend-seq-plots (Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10553481) |

| Manual alignment of RNA-Seq reads | This paper | https://github.com/CovertLab/short-gene-alignment (Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10553496) |

| Non-negative least squares (scipy) | Lawson and Handson, 1987 | https://scipy.org/install/ |

The updated whole-cell model’s benchmark outputs aligned well with the previous version of the model, while the total mRNA mass was slightly lower

With this finalized version of the updated model with operons, we compared its outputs against some experiment-validated benchmark outputs from the original version of the model without operons, to confirm that the addition of operons was not disrupting these simulation outputs in a major way. The mean doubling time of the updated simulations under minimal glucose media (47.1 ± 5.5 mins, n=1,008) was comparable with that of the old simulations (46.7 ± 4.4 mins, n=1,024; Figure S3A) and the experimentally measured doubling time of E. coli under the same growth condition (44 mins). The doubling time under rich media conditions were likewise comparable among the updated simulations (27.8 ± 7.3 mins, n=997), old simulations (27.2 ± 11.1 mins, n=999; Figure S3B), and experimental data (25 mins). We also compared the mean copy numbers of each protein species (Figure S3B) and the mean fluxes of metabolic reactions in central carbon metabolism (Figure S3C), which were two more outputs from the model that were validated against experimental data in our previous work14. The updated version of the model showed good agreement with the old version for both types of outputs, with the R2 values measured at 0.934 and 0.998, respectively.

With the addition of longer, multi-gene transcripts, we would expect the average lengths of mRNA transcripts to increase in the updated version of the model. Indeed, the abundance-weighted mean length of a contiguous, fully transcribed mRNA molecule increased from 689 ± 541 nucleotides to 1,411 ± 1,412 nucleotides with the addition of operons (Figure 4A). This increase was counterbalanced by a decrease in the mean total numbers of mRNA transcripts (6,628 ± 854 vs 2,705 ± 527; Figure 4B), which resulted in the updated model having a slightly lower mean total mRNA mass compared to the old model (2.52 fg vs 2.20 fg; Figure 4C). The distribution of total mRNA mass was more spread out in the updated simulations compared to the old version (standard deviation 0.43 fg vs 0.33 fg). This is likely due to stochasticity playing a more prominent role in determining the total mass of mRNA, due to the decreased overall counts of mRNA molecules and the increased variability in the mass of individual mRNA molecules.

Figure 4.

The updated model transcribes longer, but fewer, mRNA molecules to maintain a slightly lower total mRNA mass. See also Figure S3. (A) Comparison of the distributions of mRNA lengths between simulations with and without operons. (B) Comparison of the distributions of the total number of mRNA molecules between simulations with and without operons. (C) Comparison of the distributions of the total mRNA mass between simulations with and without operons. In all panes, the reported values were taken from each simulated cell with a fully completed cell cycle (n=768 for simulations without operons, n=758 for simulations with operons). Dashed lines represent the mean values across each simulation set.

The probability of co-expressing genes within the same operon increased for operons with low expression levels in the updated model

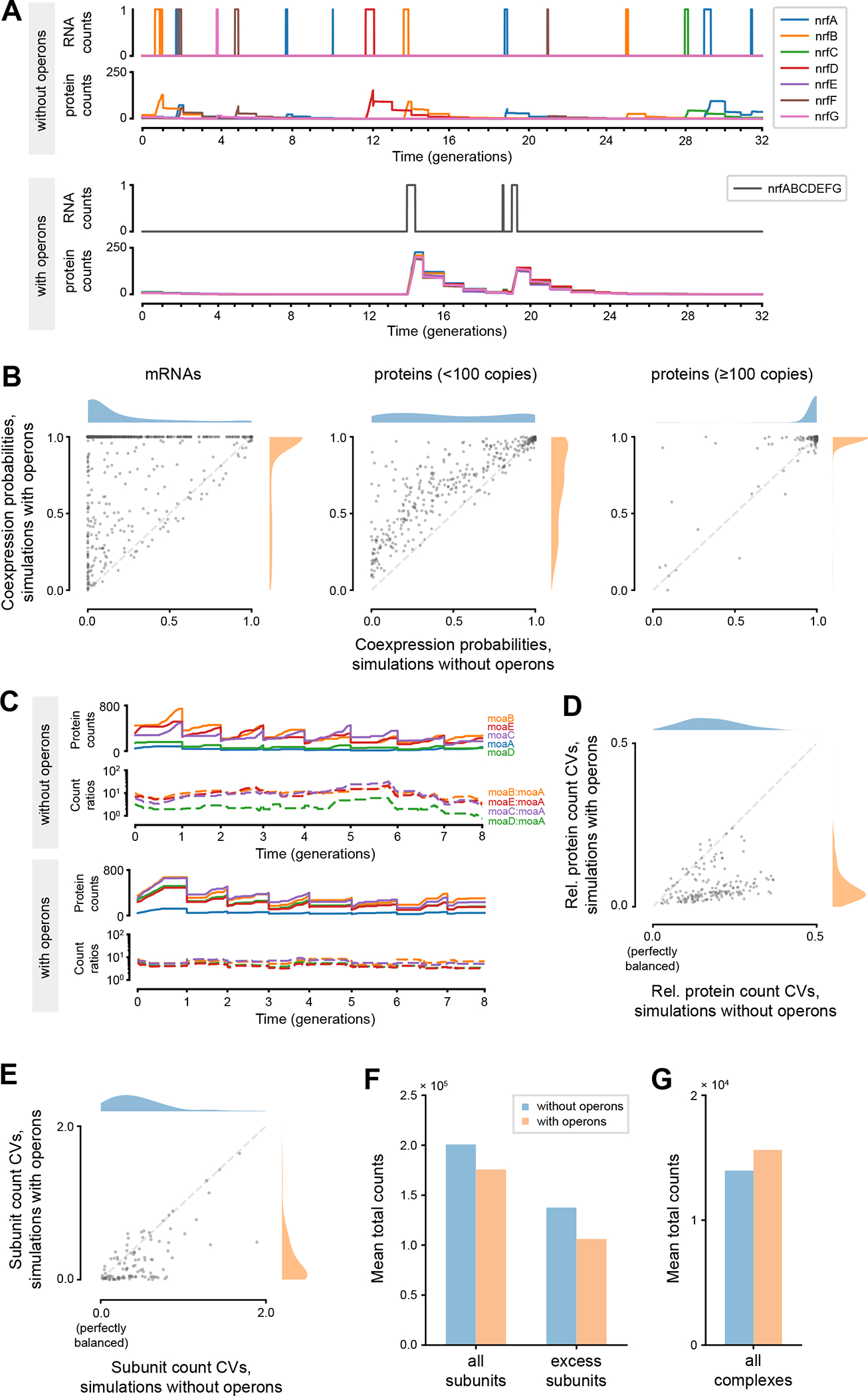

One of the most notable observations made from the original E. coli whole-cell model was that over 50% of the genes in E. coli are transcribed at a frequency of less than once per cell cycle14. This prevalence of sub-generational expression has major implications for groups of genes that are functionally dependent on each other, such that all of the genes in the group need to be simultaneously expressed for their products to fully serve their functions within the cell. If these genes are expressed sub-generationally at random, the chance of all genes within the functional group being co-expressed at any given time would decrease exponentially as the number of genes in the group increases. Placing these genes under the control of the same promoter in the same operon would ensure that these genes are always co-expressed, at a similar frequency as the transcription frequencies of the individual genes. The simulated expression patterns of the nrfABCDEFG operon, which includes genes that are essential for formate-dependent reduction of nitrite to ammonia50, aptly illustrate this principle. In simulations without operons, each of the seven genes of this operon are transcribed independently from each other, each with a frequency of less than once per generation. This results in a completely desynchronized production of the seven proteins where each of the seven proteins are independently present in different generations of cells (Figure 5A, top half). In our updated simulations with operons, all seven genes are now transcribed as part of the same transcription unit with a frequency of less than once per generation. As a result, the expression patterns for the proteins are synchronized, meaning that a particular cell is likely to have all seven proteins present or none of them present at any specific time (Figure 5A, bottom half).

Figure 5.

Comparisons between simulations with and without operons suggested possible benefits operons can bring to bacteria. (A) Simulated dynamics of mRNA and protein counts for genes in the nrfABCDEFG operon, in simulations without and with operons. (B) Comparisons of coexpression probabilities of each operon, between simulations with and without operons. Operons increase these probabilities at the mRNA level (left) and, for low-expression genes, at the protein level (middle), but not for high-expression genes at the protein level (right). See Table S3 for full data. (C) Simulated dynamics of absolute and relative protein counts for genes in the moaABDEC operon, in simulations without and with operons. (D) Comparison of coefficients of variation (CV) calculated from relative protein counts for each operon, between simulations with and without operons. See Table S4 for full data. (E) Comparison of coefficients of variation calculated from subunit counts normalized with complexation stoichiometries for each protein complex, between simulations with and without operons. See Table S5 for full data. (F) Comparison of total counts of all protein subunits and excess subunits between simulations with and without operons. (G) Comparison of total counts of all protein complexes between simulations with and without operons. In all panes, the reported values are averages of the respective values taken from each simulated cell with a fully completed cell cycle (n=768 for simulations without operons, n=758 for simulations with operons).

To further explore this hypothesis – that operons may be necessary to synchronize the expression of functionally dependent, low-expression genes – in a broader scope, for each polycistronic operon we added to the whole-cell model, we calculated the “co-expression probability” of its constituent genes, and compared these probabilities between simulations that were run with operons and without operons (STAR Methods). We defined the co-expression probability as the length of simulated time when the products (either mRNA or protein) of all genes within the group have nonzero counts, divided by the length of simulated time when at least one of the gene products have nonzero counts. We chose to divide by the length of time when at least one of the products exist, rather than the total simulation time, to normalize against the widely different overall expression frequencies of different operons. 32 operons that have one or more constituent genes that were never expressed in simulations without operons were excluded from this analysis. When these co-expression probabilities were calculated at the level of mRNAs, the updated simulations with operons had most of the probabilities clustered around 1, whereas the old simulations had most probabilities clustered around 0, reflecting a substantial increase in these probabilities as a result of using operons (Figure 5B, left). In total, the mRNA co-expression probability increased for 710 (94%) operons among 756 polycistronic operons with nonzero expression, with 392 (52%) operons seeing a probability boost by more than 10-fold.

When we calculated the co-expression probabilities using protein counts, however, the story diverged between operons with low expression and high expression. We divided the 756 operons into two similarly sized groups based on the averaged protein copy numbers expressed from the genes constituting each operon in simulations run without operon structures. Low-expression operons were defined as operons whose average protein copy numbers were lower than 100, while high-expression operons were defined as operons with protein copy numbers higher than 100. For low-expression operons (359 operons), the addition of operons still resulted in an increase in co-expression probabilities, with 307 (86%) of the gene groups seeing an increased probability in simulations with operons (Figure 5B, middle). For high-expression operons (397 operons), the increase in co-expression probabilities was less pronounced, mainly because most of the gene groups already had probabilities that were close to 1 in simulations without operons (Figure 5B, right). Since proteins are more stable than mRNAs by many orders of magnitude, many proteins remain in existence long after their respective mRNAs have degraded, which makes it more likely for a group of proteins to simultaneously have nonzero counts, even with uncoordinated expression at the mRNA level. These results suggested that we would need a different hypothesis to explain the utility of operons for these high-expression genes. Table S3 lists the calculated co-expression probabilities of all 756 operons in both sets of simulations.

Relative quantities of proteins expressed from the same operon were under tighter control in the updated model

Growing evidence suggests that many components of the bacterial transcription and translation machinery have evolved to maintain a specific stoichiometry between certain groups of functionally related proteins22. The relative abundance of enzymes in many metabolic pathways, for instance, were observed to be similar between E. coli and B. subtilis, despite these two species being separated by two billion years of divergent evolution32. While it is still unclear why a tight control of protein stoichiometries is necessary for many of these functional gene groups, some have hypothesized that operons may help bacterial cells enforce a tighter control over these stoichiometries19. Since stochastic fluctuations in protein copy numbers mostly originate from transcriptional noise7,51, expressing multiple genes as part of the same transcript would eliminate a major source of noise that could affect the relative abundance of their protein products.

To explore this idea in the whole-cell model, we first focused on the moaABDEC operon, whose constituent genes encode for enzymes that are part of the molybdopterin biosynthesis pathway in E. coli52. Four enzymes (MoaA, MoaC, MoaD, and MoaE) that are encoded by genes in this operon have conserved relative abundances between E. coli and B. subtilis32, suggesting that maintaining the stoichiometry between these proteins is important for the functionality of the metabolic pathway. In simulations without operons, the relative copy numbers of the proteins produced from these genes fluctuated, with ratios changing up to 13.0-fold throughout 8 generations of simulated cell growth (Figure 5C). In simulations with operons, however, despite the dynamic changes in the absolute copy numbers of each protein, the relative copy numbers remained relatively stable, with ratios only changing up to 2.2-fold throughout the same number of simulated generations (Figure 5D). In both sets of simulations, all five proteins were present at all simulated timepoints, indicating that the addition of operons would have had minimal effects on the co-expression probabilities of this operon.

We performed a similar analysis for 173 high-expression operons whose protein products were constantly present through all timepoints in both sets of simulations. We first normalized each protein’s copy numbers at each timestep by its mean protein copy number through all timesteps of the simulation. Then, for each operon, we calculated the coefficient of variation (CV, standard deviation divided by the mean) between the normalized copy numbers of the constituent proteins at each timestep. These coefficients quantify how far the expression stoichiometries between the proteins in the operon have deviated from their time-averaged expression stoichiometries. If the expression stoichiometries are perfectly constant throughout the entire simulation, the coefficients should be equal to zero at every timestep, but any deviance from the average would lead to higher coefficients. When we plot the time-averaged value of the coefficient of variation for each operon in simulations with operons versus simulations without operons, the value is lower in simulations with operons for 159 (92%) of the operons (Figure 5D), suggesting that operons help maintain more stable stoichiometries for these groups of proteins. Table S4 lists the calculated coefficients of variation of all 173 operons in both sets of simulations.

The addition of operons helped the model produce protein complex subunits in quantities closer to their known complexation stoichiometries

E. coli has been shown to express the protein subunits of heteromeric protein complexes in quantities that are proportional to the stoichiometries of the subunits in the protein complex53. In this case, the benefits of stoichiometric expression are more obvious – producing excess numbers of subunits is both a waste of cellular resources, and a potential hazard, as these excess subunits can form protein aggregates that can adversely affect the cell54–57. Thus, it is not surprising that genes encoding for protein subunits of heteromeric complexes are often found on the same operon53,58. Among the 1,093 protein complexes that we incorporated into this version of the whole-cell model, 271 complexes were heteromeric, and 173 heteromeric complexes had all of its constituent subunits expressed from the same operon. We hypothesized that for these 173 complexes, adding operons to the simulations would not only make the expression stoichiometries of the subunits more stable through time, but also more consistent on average with the known complexation stoichiometries of the protein complex.

Among these 173 protein complexes, we selected 107 complexes whose exact subunit stoichiometries were known according to EcoCyc, and whose subunits were not shared with other protein complexes. For each of these complexes, we calculated the time-averaged copy numbers of each subunit (including those that are already part of the protein complex), in simulations run with operons and without operons. We then normalized each subunit’s counts with their stoichiometries within the complex, and calculated the coefficient of variation between these normalized subunit counts for each protein complex. This coefficient, similarly, measures how far the averaged relative quantities of subunits deviates from their known stoichiometries within the complex, and would be equal to zero if the average expression stoichiometries of the subunits perfectly match the complexation stoichiometries. When these coefficients were compared between the two sets of simulations, we observed that their values decreased in the simulations with operons for 85 (79%) complexes (Figure 5E). Table S5 lists the calculated coefficients of variation of all 107 protein complexes in both sets of simulations.

We also quantified how the addition of operons affects the total copy numbers of excess subunits and protein complexes in the model. When we compared the mean total counts of protein subunits that constitute the 107 complexes, the simulations with operons expressed 13% fewer subunits overall compared to the simulations without operons, and 23% fewer excess subunits that were not incorporated into the complexes (Figure 5F). Despite having less subunits to work with, the mean total copy numbers of the 107 full complexes increased by 12% in simulations with operons (Figure 5G), demonstrating the improved efficiency in which the simulations with operons express and build these protein complexes.

Discussion

In this work, we built an updated version of the E. coli whole-cell model that accounts for the known operon structures of the E. coli genome and used the simulated E. coli cells to explore how these operon structures can benefit bacteria. In the process of integrating heterogeneous data into the model, we identified conflicts between the input data that resulted from computational artifacts, curation errors, or simple experimental errors, which we iteratively resolved through deep curation using the simulation outputs. The two versions of the model – one with 788 polycistronic operons, and one where every gene is its own transcription unit – were each used to simulate a group of cells and were compared in terms of their gene expression dynamics, making use of the unique abilities of the whole-cell model in performing large-scale in silico experiments where every single molecule can be precisely quantified.

Most bacteria, including E. coli, must work to overcome challenges that come from their smaller cell sizes, as compared to eukaryotes. One such challenge is that individual E. coli cells do not have enough gene expression capacity to express all genes that may be necessary for survival under rapidly changing environments14,59,60. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that adapting to survive in a changing environment, such as metabolizing newly introduced nutrients or countering antibiotics, often requires the simultaneous expression of multiple genes. Our modeling results predict that co-regulating these genes through operons can increase the likelihood that the genes are co-expressed at a genome-wide level, especially for low-expression genes that only a small subset of cells within a colony is likely to express at any given time. This would allow a colony of E. coli cells to keep the expression levels of these genes at a low level, and thus minimize the use of cellular resources on these genes, while maintaining a high probability that one or more cells would simultaneously express all of the genes required for a specific environment. In this sense, operons allow bacteria to be more efficient with their bet-hedging strategies61 by expressing more genes that are only functionally relevant in rare circumstances, while minimizing the metabolic cost associated with the expression of these genes under normal circumstances. Combined with recent efforts to represent multi-cell colonies and mechanisms of antibiotic resistance with the E. coli whole-cell model62, we may be able to use the model to explore these strategies in greater detail in future projects.

Another size-imposed challenge for bacteria is that the quantities of important gene products within the cell are subject to stochastic fluctuations59,63. Our modeling results predict that some operons in E. coli serve the function of dampening the impacts of these fluctuations by stabilizing the stoichiometry of mRNA expression between functionally related genes, as previous studies have demonstrated on a smaller scale18,19. While the transcription of mRNAs from these operons are still noisy, the fixed stoichiometries between individual genes help decrease excess expression of unused products, and also ensure that stochastic dips in the expression of a single gene do not bottleneck the other genes that serve the same function. This functionality of operons is important when the gene products of the operon form complexes with fixed stoichiometries, and, with growing evidence, when the products do not form a physical complex as well22,32. While this work only considered the mRNA operons of E. coli, the structures of the rRNA operons of E. coli also illustrate this functionality. 6 of the 7 rRNA operons of E. coli transcribe RNAs that contain one copy of each rRNA species (5S, 16S, and 23S rRNA; the rrnD operon is the only exception with an extra copy of 5S rRNA)64–66, that are later complexed into a ribosome in a 1:1:1 ratio. Co-expressing these three genes as a single transcription unit would ensure that the three rRNA species are always transcribed in the same ratio, such that no excess rRNA species are produced, and the complexation of ribosomes is not bottlenecked by a single rRNA species.

As suggested in the introduction, more targeted experimental studies would be necessary to validate these predictions made by our model on the utility of operons. For example, the model predicts the existence of many low-expression operons where operons serve the role of increasing the coexpression probabilities of its constituent genes. Many of these operons consist of genes that need to be coexpressed for the E. coli cell to adapt to a specific environment, such as a newly introduced carbon source. An engineered strain of E. coli, where the constituent genes of such an operon are decoupled to be expressed from separate promoters, would be expected to have a lower coexpression probability for these genes, and thus have reduced colony-level fitness in shifting environments specific to the decoupled operon compared to wildtype cells. Reporter genes could be used to experimentally measure coexpression probabilities, while overall fitness could be quantified through changes in growth rates. The results presented in this work may help in the selection of the most appropriate operons for such experimental studies.

In the process of updating the whole-cell model to transcribe polycistronic transcripts, we uncovered computational artifacts in conventional RNA-Seq alignment algorithms that may lead these algorithms to falsely report the read counts of the shortest genes as zero. We demonstrated that we can calculate more accurate read counts for these short genes by accounting for the known transcription unit structures of the genomes that these RNAs were transcribed from. To our knowledge, none of the currently available RNA-Seq alignment algorithms for bacterial RNA make use of information regarding the transcription unit structures of bacterial genomes. In contrast, there are various RNA-Seq alignment algorithms developed for eukaryotic RNA which make use of the known data on the intron-exon boundaries of the species that the RNA sample was taken from, in order to improve the accuracy of read counts and to quantify splicing isoforms67,68. For bacterial species like E. coli whose transcription unit structures are well-characterized, utilizing these known structures during the alignment, similar to how these eukaryotic RNA alignment algorithms utilize intron-exon structures, could potentially help avoid these issues with short genes and improve the general accuracy of read count calculations.

While this work takes a step forward in bringing the E. coli whole-cell model closer to the actual biology of E. coli cells, the model still falls short of fully representing our ever-evolving knowledge of E. coli’s transcription unit structures. Many operon-specific regulatory mechanisms, some of which may be relevant to the utility of operons under certain contexts, were not incorporated into this version of the whole-cell model. For instance, it has been shown that different mRNA isoforms can have distinct secondary structures that impact translation, which can lead to the same gene having different translation efficiencies depending on which mRNA isoform it was translated from69,70, whereas our model currently assumes a constant translation efficiency for each gene. Translational coupling, where the translation of genes on the same transcript become interdependent, has been observed to occur in many E. coli operons71–73, which would further reduce the stochastic variations in protein stoichiometries for these operons. Lastly, it has been suggested that the translation efficiency of genes can be 6 times higher for transcripts that are undergoing transcription, compared to transcripts that have been fully transcribed74, which would shift the relative expression levels of proteins that are produced from longer operons, as genes that are closer to the start of the operon will have more time to be translated while the mRNA is being transcribed.

We would also like to emphasize that our results do not invalidate the other hypotheses that have been proposed on the utility of operons. In fact, it is likely that all of the proposed mechanisms contribute in concert to maintain the existence of operons in bacterial genomes. Some of the E. coli operons that we have analyzed in this study neither improved the co-expression probabilities of their constituent genes, nor stabilized the stoichiometric balance of their proteins, suggesting that other theories may better explain the existence of these operons, assuming that our model’s parameters and assumptions for the operon were largely correct. A targeted probe into these operons may lead to interesting discoveries about their functional roles or point to errors in our current understanding of these operons.