Summary

Neuronal ensembles, defined as groups of neurons displaying recurring patterns of coordinated activity, represent an intermediate functional level between individual neurons and brain areas. Novel methods to observe and optically manipulate the activity of neuronal populations have provided evidence of ensembles in neocortex and hippocampus. Ensembles can be activated intrinsically or in response to sensory stimuli and play a causal role in perception and behavior. Here we review ensemble phenomenology, developmental origin, biophysical and synaptic mechanisms, and potential functional roles across different brain areas and species, including humans. As modular units of neural circuits, ensembles could provide a mechanistic underpinning of fundamental brain processes, including neural coding, motor planning, decision-making, learning and adaptability.

Keywords: attractor, assembly, synfire, neural networks

How neural activity is transformed into perception, cognition or action is arguably the central question of neuroscience. To answer this question, a circuit-level approach appears necessary to enable bridging the activity of individual neurons with higher-level cognitive processes. But brain circuits are complex, with vast numbers of interconnected neurons of hundreds of different types. The goal of our review is to examine if there are unified functional principles governing the organization of neural circuits, focusing on a structured form activity within neuronal populations known as “neuronal ensembles”. Neuronal ensembles are defined here as a group of neurons that display recurring patterns of coordinated activity. We argue that ensembles are endogenous building blocks of neural circuits, which act as modular functional units. They could be a versatile mechanism for many brain functions and implement emergent properties, i.e. functions that, by definition, are not present in the individual neurons themselves.

Origin of the ensemble hypothesis

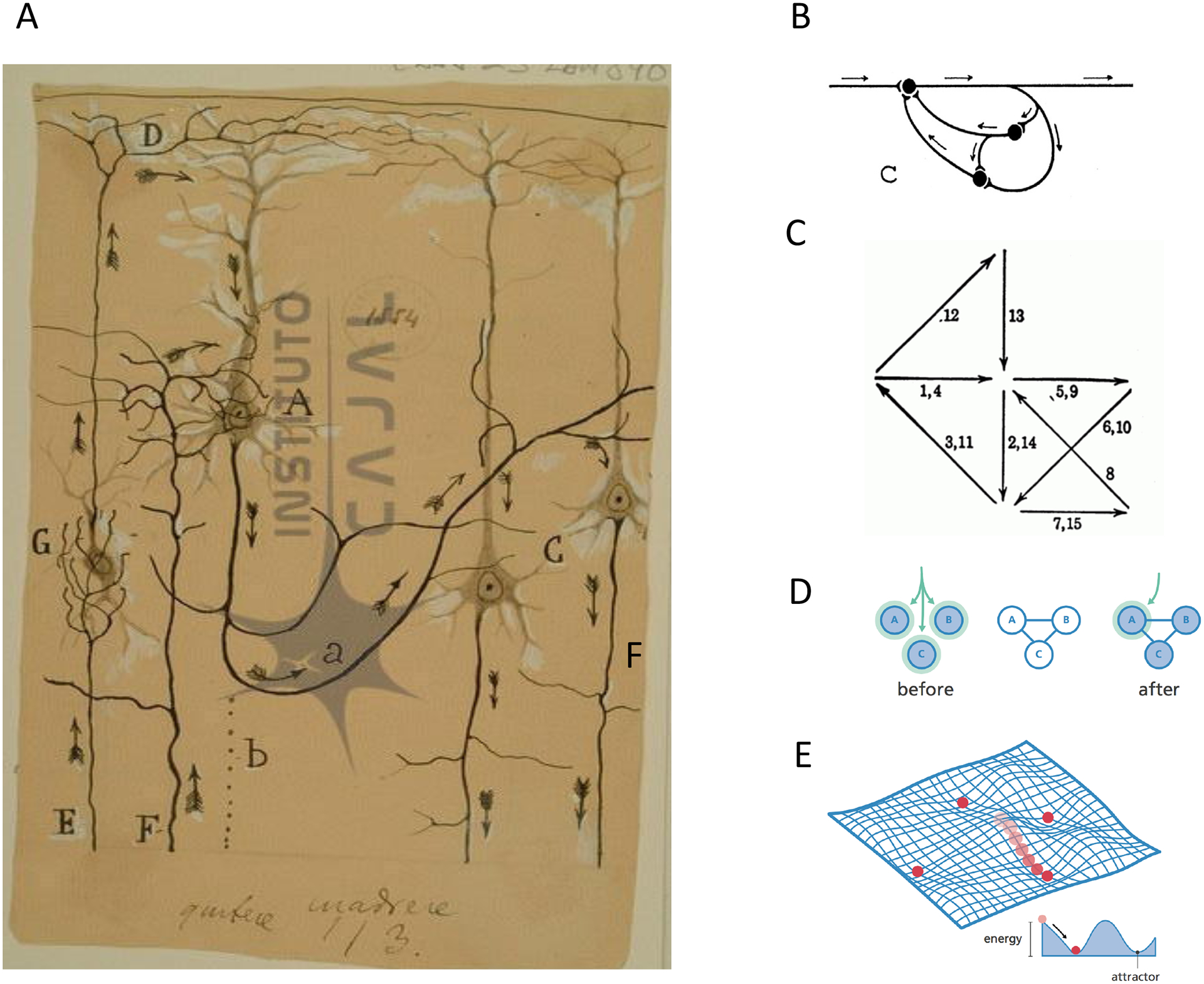

The idea that neurons cooperate to form emergent functional units has a long history. Indeed, Cajal’s drawings already represented cortical circuits as repeated modular structures, with neurons linked by arrows that illustrated the flow of activity within them1 (Figure 1A). Providing electrophysiological flesh to these arrows, Sherrington proposed that groups or “ensembles” of neurons form reflex arcs, i.e. synaptic circuits linking sensory stimuli with motor responses2. Combining both anatomical and physiological viewpoints, Lorente de Nó reasoned that “reverberating chains” of neurons, activated via recurrent excitatory feedback connections, would act as modular units of cortical activity and endogenously generate persistent activity, even in the absence of external inputs3 (Figure 1B). The idea that cortical activity is organized and parceled in small groups of neurons was further developed by Hebb, who argued that recurrently connected groups of neurons could form “assemblies” due to synaptic plasticity, by strengthening connections from coactive cells4 (Figure 1C). Incorporating Semon’s proposal of the engram as the neural substrate of a memory5, Hebb also hypothesized that assemblies could be triggered by the activation of a subset of key neurons, thus generating “pattern completion”, i.e., the ability of a part of a system to activate the whole (Figure 1D). Pattern completion is a hallmark of memory retrieval and of many brain functions, including speech, motor behaviour, emotions and cognition. Following Hebb’s ideas, Marr built computational models of the cortex and hippocampus and proposed that pattern completion arose in them by the amplification of internal activity due to recurrent network connectivity6. Hopfield provided further mathematical generalization of these models, applying to neural circuits the Ising model of ferromagnetism that explained how the generation of emergent states arises in magnets from the functional coupling among elements. Hopfield predicted that, similarly to magnetic states, strongly coupled neurons in recurrently connected networks naturally form stable activity states, which he called “attractors”, as they “attract” the activity of the population7 (Figure 1E). These attractors, endowed with pattern completion, would implement memories and also generate solutions to optimization computations like the travelling salesman problem8,9. Independently, Abeles reached also the conclusion that cortical function must be organized as groups of synchronously active neurons. Realizing that most cortical synapses are weak, stochastic, have short-term depression dynamics, and the fact that the action potential threshold imposes a strong non-linearity in the activation function of the neuron, Abeles proposed that the only way for neuronal activity to propagate through the cortex was via coactive groups of neurons. These “synfires chains”, another conceptualization of the idea of an ensemble, would sequentially activate each other, forming temporal chains of synchronous activity10.

Figure 1: Original models of ensembles.

(A) Cajal’s drawing of neuronal activity progressing through a putative cortical module (Courtesy of the Cajal Institute, “Cajal Legacy”, Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), Madrid, Spain). (B) Lorente’s representation of a reverberating chain. Adapted with permission from3. (C) Hebb’s representation of activity flow (arrows) through a neuronal assembly. Adapted with permission from4. Note recurrent connectivity. (D) Pattern completion: after neurons are activated by a synchronous input (left), connections between neurons are generated, or strengthened, (middle), and stimulation of one neuron triggers the rest. Adapted with permission from240. (E) Attractor landscape generated by a recurrently connected neural network. Population activity is represented as a ball that rolls over to the lowers energy point, where a group of neurons is coactive, defining an attractor. Adapted with permission from240.

One can capture the essence of these proposals with the previously mentioned working definition of a neuronal ensemble as a “group of neurons displaying recurring patterns of endogenously coordinated activity”. Thus, these groups of coactive neurons can occur with or without external sensory stimulus and their reproducible patterns of neural activation can be categorized as circuit attractors. It is important to note that the neurons of an ensemble could also be involved in different types of activity, unrelated to the group. For homogeneity and concordance with the majority of the literature, we use Sherrington’s original term of “ensemble” to describe circuit modules with synchronous, or closely correlated, coordinated activity. But, differently from Sherrington reflex arcs, ensembles would be intrinsically generated and be activated either endogenously or by an outside stimulus, as proposed by Lorente, Hebb, Hopfield, Abeles and many others. Therefore, in the ensemble hypothesis, the emphasis switches from a neural circuit that responds to the outside environment as an input-output system to one that has ingrained activity patterns embedded into it. This distinction is important because it highlights the possibility of activity states generated by neural circuits that could be independent of the outside world, and can therefore be used to implement internal representations of objects11, memories or cognitive states4.

Novel methods to study ensembles

Experimental search for ensembles has been hampered by the inability to record the activity of many neurons simultaneously. Neuroscientists traditionally used single cell recordings and correspondingly focused on describing responses of individual neurons such as receptive fields. But ensembles, which, as an emergent property, reflects the interaction between neurons, by definition cannot be captured by recording one neuron at a time. The recent developments of multielectrode recordings and voltage or calcium imaging from large numbers of individual neurons have transformed our ability to identify and characterize multineuronal activity patterns12–46 (Table 1). The phenomena described using these methods are diverse and so is the nomenclature used to define or describe them. Besides ensembles, other terms have been used to describe patterns of coordinated neural activity, such as assemblies, attractors, reverberations, synfires, domains, oscillations, trajectories, clusters, groups, packets, domains, flashes, songs, bumps, avalanches, trajectories and states, among others (Box 1).

Table 1:

Experimental descriptions of multineuronal activity patterns.

| attractors | V1, entorhinal cortex, anterior lateral motor cortex, frontal cortex, hippocampus | 10ms-1sec, <<1Hz | hours to days | Spontaneous, Decision making, motor planning, working memory | Mouse, human | 202 27 29,32,33 |

| ensembles | Sensory and motor cortex, hippocampus | 100ms-sec | days | Perceptual states, Awareness | Mouse, Human, Monkey | 36,37,39,40,44,45 |

| assemblies | adult hippocampus, developing barrel cortex prefrontal cortex, striatum | 50–200ms, 0.1Hz | days | Substrate for internal cognitive processes, including memory and planning, circuit development | Rat, mouse | 20,34,24–26,35,38,41,42,203 |

| avalanches | Organotypic cultures | 10s msec, <1 Hz | >10 hours | A critical state serving information transmission and network stability | Rat | 19 |

| clusters | Developing habenula | Seconds, <0.1Hz | days | Learning | Zebrafish | 43 204,205 |

| domains | Neocortex slices | Seconds, <0.1 Hz | days | Circuit formation | Rat | 16,17 |

| engrams | Hippocampus | Seconds, <0.1 Hz | days | Memory encoding and retrieval | Mouse | 83,206–208,44 |

| flashes | V1 slices | 100msec-sec | hours | Spontaneous states | Mouse | 47 |

| packets | Sensory cortex | 50–500ms, 0,1 Hz | hours | Cortical communication | Rat | 21,31 |

| sequences | Motor cortex hippocampus | 10ms-sec, <0.1 Hz | Hours | Choice-decision Integration of information |

Mouse |

28

64 |

| songs | Neocortical slices | 10ms-sec, <0.1 Hz | Hours | Spontaneous | Mouse | 18 |

| trajectories | Motor cortex | 10ms-sec, <0.1 Hz | Days | Motor reaching | Monkey | 30 |

Box 1: Definitions of ensemble-related phenomenology.

Ref.20: A cell assembly is defined as a group of neurons that meet four criteria: 1) display structured temporal patterns of spiking even without temporally structured stimuli; 2) spiking is not strictly controlled by sensory input; 3) coordinated spike times; 4) assembly activity correlates with internal cognitive processes.

Ref.26: Cell assemblies are transiently active ensembles of neurons

Ref.23: Assemblies are the result of the dynamic congregation and segregation of excitatory principal cells into functional groups,

Ref.21: Temporally organized packet of population activity lasting 50–200 ms

Ref.24: Cell assemblies are formed by the co-activation of groups of neurons thought to underpin information representation in the brain.

Ref.25: Neuronal assembly: a group of neurons that can be recruited together due to synaptic connections between them, usually as a consequence of a learning process. Neurons belonging to one assembly can be distributed between several interconnected brain areas. Neuronal assemblies can be viewed as the smallest counterparts of representations in the brain and might represent the physical bases of memories. This term is mostly used in the context of learning and memory.

Neuronal ensemble: a population of neurons involved in a particular computation. The notion of ensemble implies that coding is produced by populations of neurons whose individual contributions are noisy but that together produce coherent outputs. The term is mostly used within systems and computational neuroscience to describe a neural network with a particular function.

Engram: the hypothetical physical means through which memories are stored in the brain. Engrams are thought to reflect biochemical and biophysical reactions in the brain induced upon learning, which are maintained as latent traces to allow subsequent memory retrieval.

Ref.209: Collections of principal neurons that fire together over a time scale of tens of ms.

Ref.105: Neuronal ensembles are coactive groups of cortical neurons, found in spontaneous and evoked activity that can mediate perception and behavior.

How do all these different descriptions relate to neuronal ensembles? These recent results describe how neuronal activity propagates through circuits by engaging distinct groupings of neurons, and different studies highlight different aspects of this multineuronal activity. A core feature of ensembles is that they can become endogenously active, in the absence of external stimuli47,48. And indeed, many of these studies have revealed that coactive, or sequentially active, groups of cells work together as endogenous functional modules. As we will discuss, data from both cortex and hippocampus demonstrate organized spontaneous activity in the absence of sensory stimulation or motor behavior. The origin and function of this ongoing spontaneous activity, which is present throughout the nervous system49–54 and in species raging from humans55 to fish46 and cnidarians56, is still poorly understood and could reflect different physiological or cognitive processes. But it is clear that spontaneous activity is not “noise” in the system, but has a particular structure. Indeed, as we will see below, the groups of neurons that are activated spontaneously can be the same as the ones that are activated during perceptual tasks or behavior, consistent with the idea of ensembles as internal circuit units that can be engaged by external stimulus.

In most experimental descriptions of ensembles, they are fine-grained and structured units with a particular spatiotemporal scale, involving a small percentage of the neurons that are activated for a characteristic duration of time, constrained by the method to record neuronal activity (Table 1) and the analytical approaches used (Box 2). While there is no set rule, most studies define ensembles as groups of neurons that are repeatedly activated within a period of a few milliseconds to a few seconds. In addition, individual neurons can join different ensembles, which enables combinatorial, compositional and hierarchical arrangement of ensembles, just like in other emergent systems57,58.

Box 2: Analysis challenges to detect ensembles.

One standard method to analyze neuronal ensembles is to calculate correlations between multi-neuronal firing or calcium signals and identify statistically significant clusters of synchronous neurons46,54,210–212. Estimating the probability of occurrence of such synchronous firing of neurons is possible by using simple multi-variate statistical tools, and variations of singular value decomposition and factor analysis88,94,105,213,214 35,212,215. Yet, especially for spiking data, one needs to consider jitter in neuronal firing in order to build proper statistical models98,216. While such jitter in neural activity is less of a problem for calcium imaging with low temporal resolution, calcium signals with relatively high levels of noise impose an additional challenge. Hence, in both electrical and optical methods, different kinds of noise could result in an underestimation of the components of neural ensembles and ideally require several independent statistical approaches for identifying ensembles.

Aside from the statistical significance of the patterns, another matter to consider, when identifying neural ensembles, is the choice of temporal bin or period selected for analyzing relationships between neurons. Different neural and behavioral processes occur in different time windows. For example, synfire chain of neurons can last for few hundreds of milliseconds18,65,66,92, but some other types of ensemble activity can last several seconds46,49,56,62,217 18,63. Such long lasting sequential activation of neurons poses a major analytical challenge for identifying neural sequences that might appear randomly and cannot be studied by zero lag correlation-based analysis. Applying graph-based methods might offer some solutions, yet the longer the time windows of neural sequences, the exponentially larger number of iterations one needs to run to identify such sequential activations of neural ensembles. One potential approach could be to identify ensembles triggered by distinct tasks or stimuli (sensory, optogenetic, microstimulation), and then to use these reliably activated sequences of ensembles92 as a “Rosetta Stone” for deciphering other ensemble sequences that might precede or follow these reliable ensembles. Hence, multiple analytical and experimental strategies are needed for investigating the temporal dynamics of ensemble sequences occurring in different time scales.

Similarly, slower and state dependent alterations of neural excitability through neuromodulators, metabotropic receptors as well as astroglia could have a major impact on the type of ensembles one might observe. For instance, ensembles could grow and shrink in size depending on the reach of available neural excitation, and on the changing excitability thresholds of neurons to be recruited in the ensembles. This might in fact be one of the major strengths of neuronal ensembles, that can arise by recruiting permutations of neurons within the same population and by utilizing those permutations for different tasks and purposes. Such multiplexing of available neural populations doesn’t require building new synapses through Hebbian processes or other slow alterations of circuit architecture, and instead can be achieved fast and at very low cost by altering neural excitability. Probing such processes pre- associated with distinct behavioral programs and neural processes might not require very specific circuit manipulations. For example, one strategy to test these processes might be to “heat” or “cool down” neural networks, by gradual alterations of ambient neurotransmitters levels or cations, as well as manipulations of synaptic receptors and neural excitability through pharmacology or optogenetics. In such a scenario one would not expect a linear expansion for the number of neurons participating in ensemble activity but instead critical jump points that expand and change the composition of neurons within ensemble. Perhaps, facilitation or disruption of specific behaviors or spontaneous activity via broad opto-/chemogenetic activation or inhibition of neurons and even astroglia in specific brain regions133,218,219 might similarly result in in unspecific alteration of local excitability.

Such critical jump points and nonlinear expansion of ensemble size could also relate to a hierarchical order, where number of smaller ensembles are nested within larger ensemble and are merged only when neural excitability reaches to a critical state. The sequential recruitment of motor patterns, or behavioral fixed action patterns, is a hallmark of most complex behaviors, all the way to cnidarian locomotion220,221. Moreover, similar hierarchies of ensembles have also been observed throughout development, where larger ensembles eventually give rise to smaller and more specific ensembles, through maturation of neurons and synapses43,222,223. Finally, it is important to add that such nested ensembles do not have to exist within only a single brain region but can involve interconnected ensembles across distant brain regions213.

Neuronal ensembles in hippocampus

The hippocampus is one of the first brain regions where experimental evidence for the ensemble existence was collected in vivo in the form of repeated coordinated firing of subsets of pyramidal cells, potentially carrying together more information than single neurons34 (Figure 2A). Coordinated neuronal activity was sequential, with neurons firing one after another within the period of a theta cycle34. Recurring sequences of neuronal activation forming hippocampal ensembles can span from a few milliseconds, nested within sharp-wave ripples, to several seconds59–63 64. When the same neurons are recorded across different behavioral states, larger hippocampal ensembles can be segmented into smaller functional units. For example, seconds-long hippocampal sequences observed during locomotion are in fact formed by chains of successive ensembles activation35; Figure 2B).

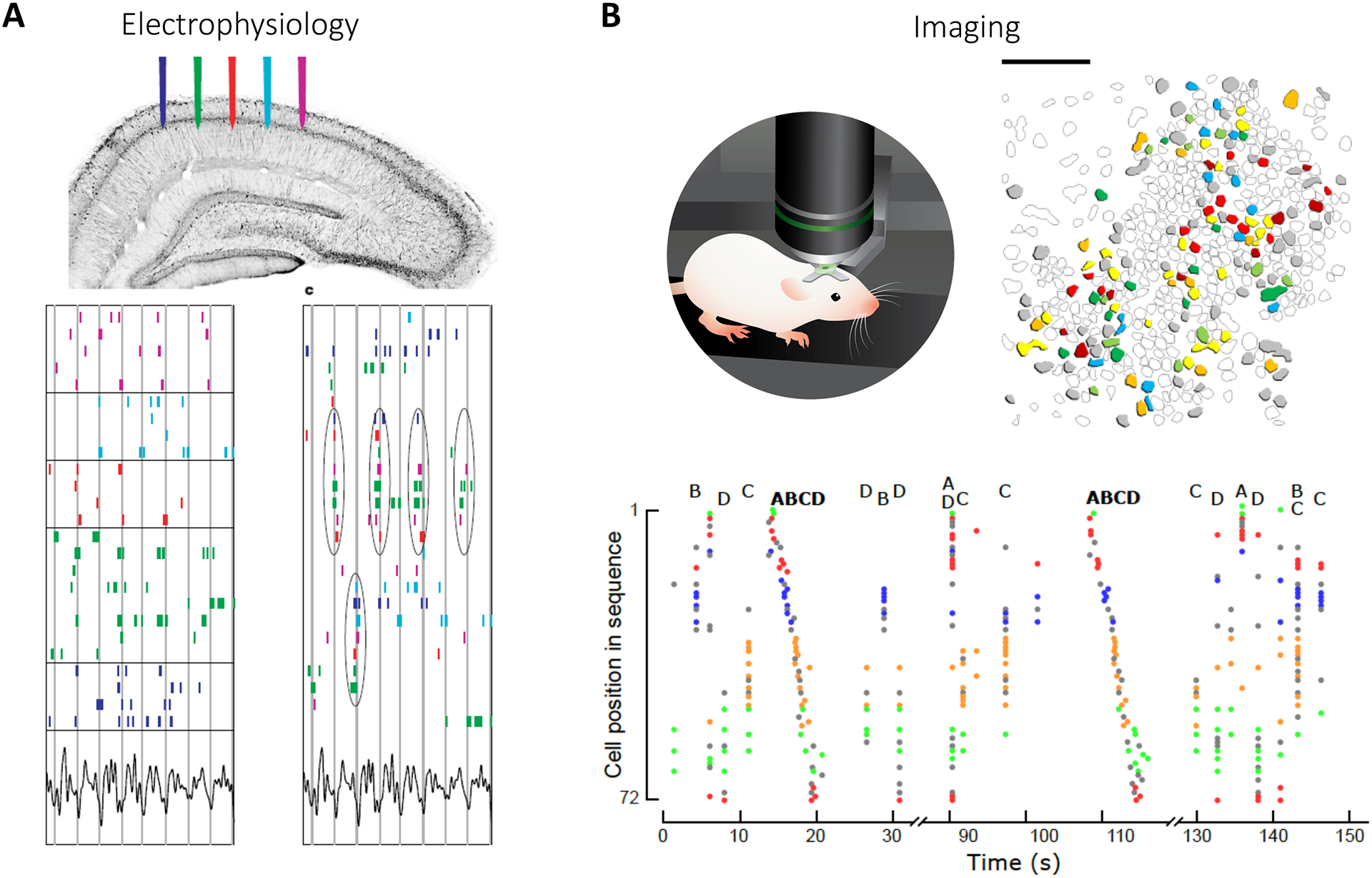

Figure 2: Hippocampal ensembles.

(A) Top: Extracellular electrophysiological recordings in vivo. Bottom left: Raster plots of spiking during spatial exploration arranged in order of physical position along CA1 pyramidal layer (vertical lines indicate troughs of theta wave). Bottom right: Spike raster rearranged to highlight synchrony demonstrate ensembles, with repeatedly synchronous firing of neuronal subpopulations (circled). Adapted with permission from34. (B) Top left: Two-photon calcium imaging of CA1 neurons in head-fixed mice in vivo. Top right: Contour map of imaged neurons shows spatially-intermingled ensembles (color coded according to ensemble membership). Bottom: Rasterplot displaying neuronal activation, color-coded according to ensemble affiliation (4 ensembles labeled from A to D). Ensembles are re-activated in the same order during sequences.

Importantly, these hippocampal sequences can be reactivated offline during sharp-wave ripple oscillations, recorded during quiet rest or sleep. This is known as “replay”65–67, and agrees with the idea that ensembles arise from intrinsic neuronal dynamics, as external stimulation is minimal during rest. Consistent with this, the same ensembles observed during behavior can be artificially activated through optogenetic activation of local excitatory neurons22. Hippocampal ensembles are therefore structured independently from external inputs. In addition, they appear remarkably resilient to transient perturbations63,68–71 and also stable across days41,69. It is possible that hippocampal ensembles are recruited from a predefined reservoir constrained by developmental programs, before any contextual spatio-temporal information is mapped into them72–75.

Hippocampal ensembles appear anatomically scattered and sparse35. Although the data is still preliminary, hippocampal ensembles may be functionally orthogonal, meaning that the activation of one ensemble may suppress the others35. Several circuit mechanisms could support ensemble formation and competition, including changes in intrinsic excitability (see below) and local interneurons76, which could also provide a temporal backbone for sequential spiking22,77.

Importantly, hippocampal ensembles can be causally linked to behavior. Indeed, activating or inhibiting neuronal ensembles associated with SWRs or theta sequences can impair spatial memory acquisition or recall78–81. This suggests that hippocampal ensembles could also function as engrams. Experimentally, engram cells are often defined as groups of neurons expressing immediate early genes following a given experience, that when re-activated, reproduce the behavior observed during that experience82. The link between engrams and ensembles has been analyzed in two studies44,83. In novel environments engram neurons encode context rather than space83 while in familiar environments they represent stable place cells44. Therefore, engrams could be hippocampal ensembles dedicated to context rather than groups of neurons encoding spatio-temporal information into sequences. But, although the coordinated engram cell activation can reactivate a memory, the population dynamics evoked by the synchronous activation of c-fos expressing neurons remains unknown and could activate endogenous ensembles, independently from the engram cells84. Thus, the relation between engrams and ensembles still remains unclear. Engrams would qualify as ensembles if the activation of the cells forming the engram was repeatedly coordinated. Future studies examining the temporal order of activation of the cells recruited in engrams may certainly help clarifying this point.

In summary, multineuronal recordings reveal that the hippocampal system is organized into discrete ensembles involving sequentially firing groups of neurons, whose activation can be linked to spatial cognition.

Neuronal ensembles in neocortex

Results from sensory areas in the cerebral cortex parallel many of the findings from hippocampal ensembles. Coactive, or sequentially active, groups of neurons consistent with the ensemble definition have been described in neocortex in vitro and in vivo, using voltage or calcium imaging15,18,36,37,47,48,53,54,85–90 and electrical recordings18,20,31,49,86,91,92(Figure 3A). Coordinated and repeated neuronal activation was found under spontaneous and sensory-evoked neuronal activity and lasted from tens of millisecond up to a second, involving a minority (<10%) of neurons in a given cortical territory37,47,48. In calcium imaging data ensemble neurons are coactive in individual imaging frames (~100Hz), whereas voltage imaging and electrical recordings reveal millisecond accurate temporal substructures with repeated sequences of neuronal firing85,86,93. Like in hippocampus, individual neurons participated in multiple neocortical ensembles47,48, providing a substrate for combinatorial coding. Consistent with the hippocampal replay, cortical ensembles evoked by sensory stimuli can also become spontaneously co-active in the absence of stimuli48,85,86,94 (Figure 3A). Cortical ensemble replay can occur during sleep95. Also, like in hippocampus35,63, ongoing ensembles block the activation of other ensembles76, and persist during sensory stimulation”96. These results imply that cortical ensembles are endogenous modular blocks of circuit activity, which can be recruited by sensory inputs53,85,86,97.

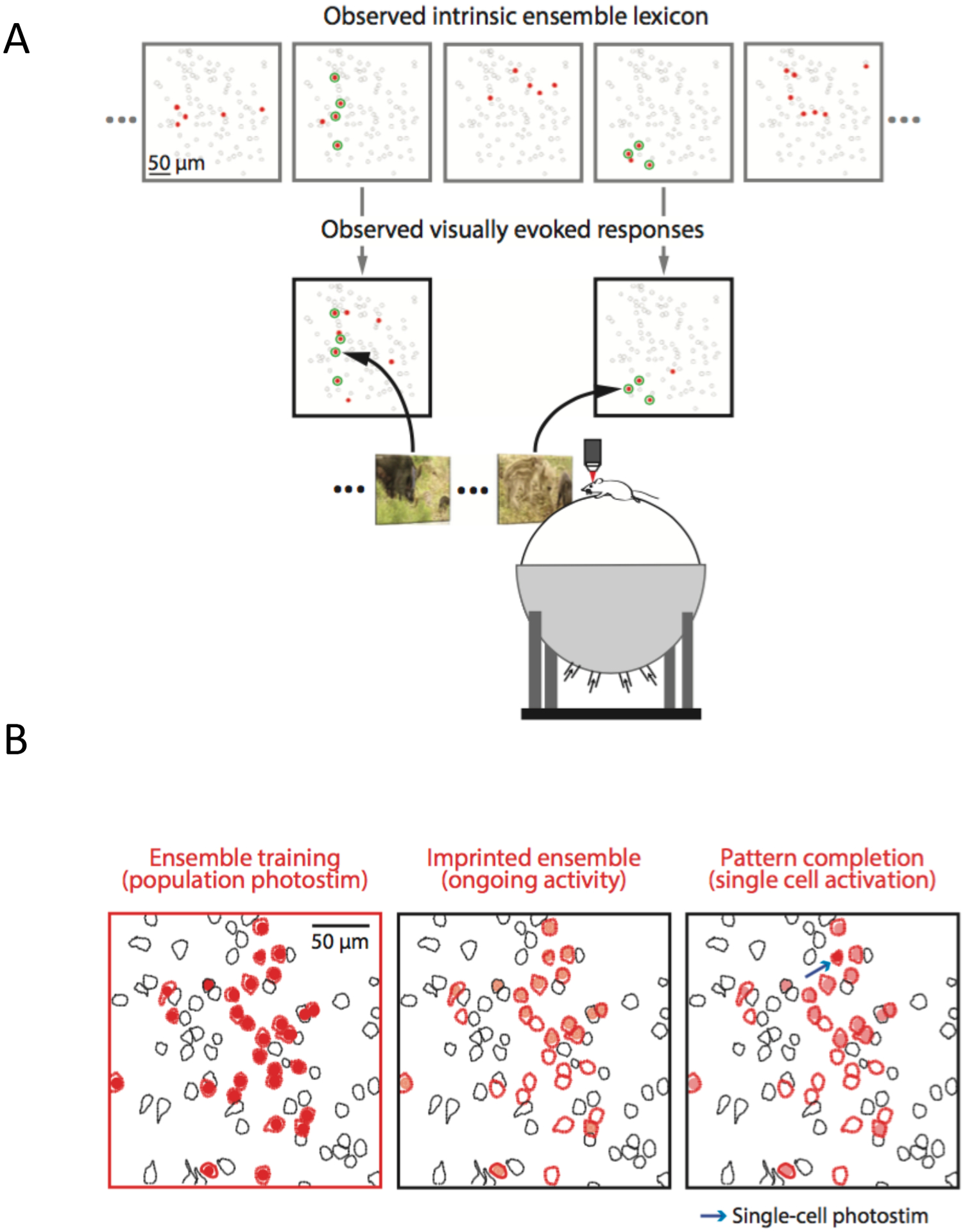

Figure 3: Neocortical ensembles and pattern completion.

(A) Cortical ensembles activated spontaneously (top) or by naturalistic visual stimuli (bottom) in mouse primary visual cortex in vivo. Red cells are members of an ensemble and green are those active in both conditions. Note similarity between visually-evoked and spontaneous cortical ensembles. Adapted with permission from48. (B) Ensemble imprinting and pattern completion. Left: Two-photon optogenetic activation of a group of neurons (red). Middle: Many stimulated neurons become spontaneously active, forming an ensemble (light red). Right: Ensemble is reactivated by optogenetic photostimulation of one neuron (arrow), demonstrating pattern completion. Adapted with permission from36.

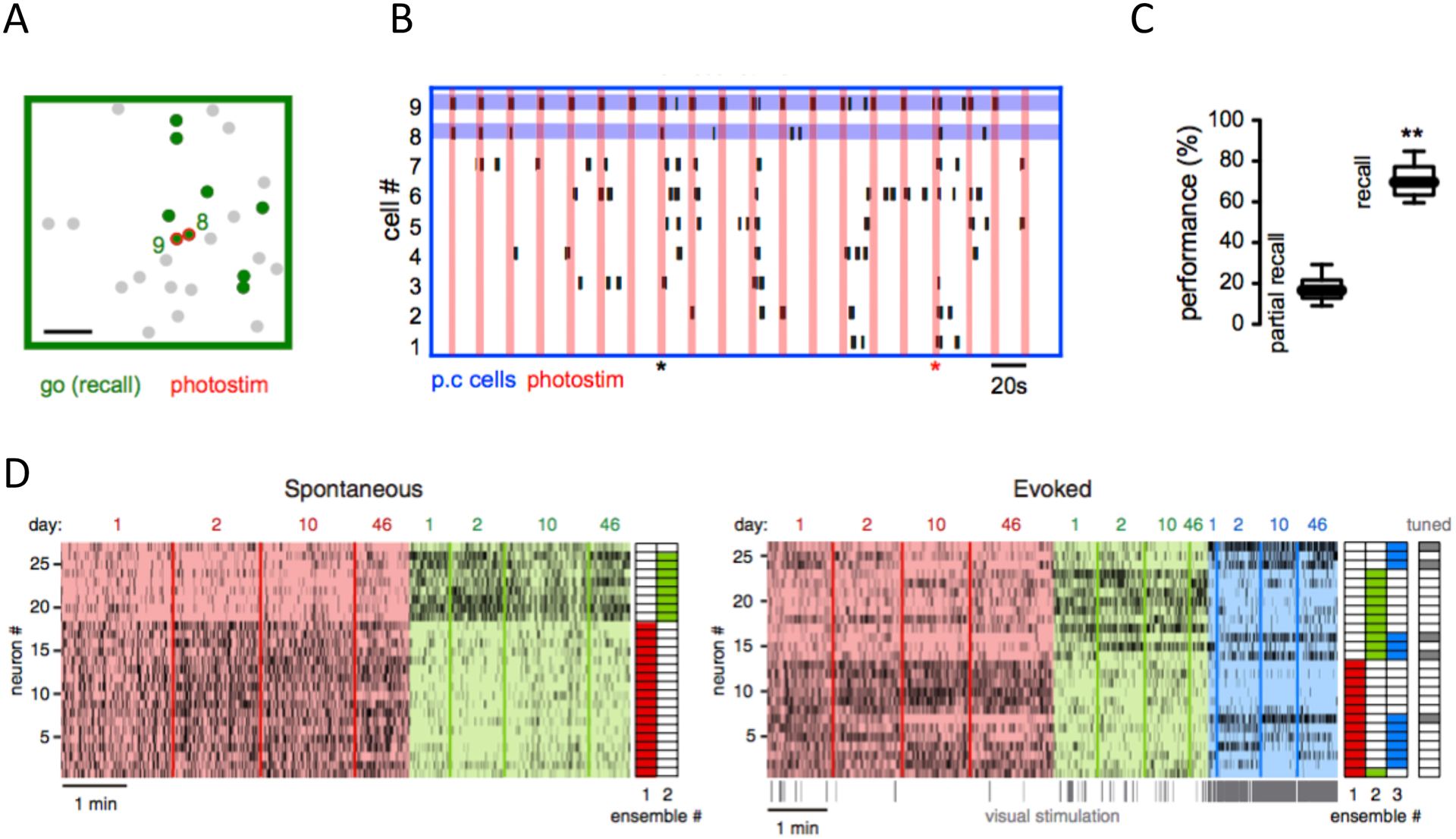

In primary sensory cortex, the function of these endogenous cortical building blocks has been causally linked to perceptual and behavioral tasks. Visual ensembles can be observed under anesthesia but are particularly common when the animals are awake and viewing natural scenes48, supporting the possibility that ensembles have a physiological role. Indeed, precise firing patters, as potential cellular signatures of structured ensemble activity, are seen during stimulus processing98 and delayed localization tasks99. Ensembles also encode cognitive variables in operant tasks100,101. Ensembles can also be created de novo by inducing correlated activity in groups of neurons in a behavioral context102. In agreement with this, activating neurons synchronously with holographic optogenetics can imprint an ensemble into visual cortex, and the imprinted ensemble can be triggered by the stimulation of a single cell, demonstrating pattern completion36 (Figure 3B). Imprinted ensembles and their pattern completion persist in the cortex for at least several days, as if the microcircuit had been reprogrammed by the optogenetic stimulation36. Similarly, ensembles created artificially can be assigned different stimulus valences103. Holographic optogenetics can also be used to manipulate behaviorally-relevant ensembles in Go/No-Go visual discrimination tasks. In these experiments, inactivating visually-evoked ensembles blocked visually-guided behavior, whereas their activation substituted for the presence of the visual stimulus, and triggered the behavioral task37,88,104 (Figure 4A). Thus, these experiments demonstrated that ensembles are both necessary and sufficient for perceptual tasks, consistent with the hypothesis that they are building blocks of perception88. Cortical ensembles, both visually evoked and spontaneously active ones, are also stable for weeks105 (Figure 4D), providing a potential substrate for perceptual stability, overcoming the representational drift generated by individual neurons, whose activity vary over time106–108,109.

Figure 4: Neocortical ensembles can trigger behavior and are long-lasting.

(A) Ensemble activated by Go stimulus in a visual discrimination licking task (green neurons). This ensemble can be reactivated by two-photon optogenetic stimulation of two cells (red). (B) Behavior induced by recalling a Go ensemble in absence of visual stimuli. Raster plot of activity of ensemble neurons during holographic stimulation of those two pattern completion cells (blue lines). Vertical red lines indicate optogenetic photo-stimulation. Red marker shows successful recall of Go ensemble and licking behavior. Black marker shows partial recall with no behavior associated. C. Behavioral performance evoked by recalling Go ensemble by optogenetic stimulation in the absence of visual stimuli (right) is significantly higher than performance in partially recalled trials (left). Adapted with permission from37. (D) Long-term stability of ensembles. Rasterplots of spontaneous (left) and visually-evoked (right) neuronal activity over 46 days in mouse visual cortex in vivo. Neurons sorted based on ensemble identity (color-coded; right columns illustrate ensemble assignment). Adapted with permission from105.

In summary, cortical ensembles echo many of the properties from hippocampal ensembles, including their sequential structure and endogenous nature, as they can occur during ongoing activity but be recruited by behavioral tasks or evoked by sensory information. Moreover, the use of holographic optogenetics has confirmed that cortical ensembles can be causally related to behavioral tasks.

Mechanisms of ensemble generation and recruitment

In spite of the importance of ensembles for hippocampal and cortical function, little is known about their biological properties. Many questions remain open: How are ensembles generated? Do ensembles arise from strengthening of existing synaptic connections? How do neurons within an ensemble coordinate their activity? How are ensembles recruited, once formed?

Since cortical ensembles can be generated by simultaneous stimulation of groups of cells36,102, it is widely assumed that Hebbian plasticity is involved in establishing cortical ensembles, by synaptic strengthening generated by joint firing of pre-and post-synaptic neurons, following, for example, spike-timing dependent plasticity (STDP)110,111. But, as an alternative, and not necessarily contradictory, hypothesis, intrinsic changes in excitability could also help generate coordinated activity in an ensemble. For example, if neurons become more excitable, the same synapse could have a stronger effect, and thus result in an enhanced synaptic input, an analogous effect to synaptic strengthening. In fact, several experiments have revealed cell-intrinsic changes in excitability in neurons after periods of neuronal activity112–115. Moreover, increases in excitability are found following long-term potential (LTP) induction protocols in visual cortical neurons116 and hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells117. The excitability of cortical neurons is also modified after behavior training118, exposure to novel sensorial experience119 or environmental enrichment120. Interestingly, changes in intrinsic excitability appear to underlie the selection of place cell in the hippocampus121 122,123. Also in hippocampus, a short-term increase of excitability of engram cells (as defined by c-Fos expression) enhances the subsequent retrieval of specific memories115. This is consistent with experiments where the activation of hippocampal engram cells recalls stored memories under protein synthesis inhibitors, which should prevent synaptic plasticity113,124.

Consistent with an important role for excitability in ensemble formation, cortical neurons display increases in intrinsic excitability after optogenetic or electrical stimulation of groups of neurons that generates ensembles125. In those ensembles, paired recordings showed fast increases in excitability, input resistance and rheobase, but without evidence of new synapses. A small synaptic enhancement was observed only after longer periods of stimulation, suggesting that intrinsic excitability changes creates ensembles, whereas synaptic plasticity could become important at later stages, perhaps during learning or consolidation. Altogether, these results indicate that, in addition to Hebbian synaptic plasticity, the formation of an ensemble could rely on cell-autonomous intrinsic mechanisms.

A related question is the ensemble composition. How are neurons assigned to an ensemble? Is ensemble membership random or are there specific neurons, or subtypes of neurons, that are key to turn an ensemble on, or perhaps to turn it off? Although ensembles can be built in neocortex in vivo by activating a group of pyramidal neurons (Figure 3D)36, it remains unclear whether these cells belong to a specific subtype of neurons or have stronger interconnections to the rest of the neuron in the ensemble, a property that could reflect an early developmental program126. Inhibitory neurons could also be important for generating ensembles. Cortical and hippocampal interneurons belong to many different subtypes127, so it is quite likely that interneurons subtypes will play different roles in generating and modulating ensemble activity. Although it may seem paradoxical, GABAergic interneurons can coordinate groups of excitatory cells in hippocampus128,129. Indeed, during development, GABAergic “hub neurons” that are highly connected to the rest of the ensemble play a key role in ensemble generation129,130. GABAergic interneurons also parse the temporal order of firing within hippocampal ensembles22,77 and suppress competing hippocampal ensembles69,70,76,131. Perturbing interneurons also disrupts grid cell ensembles in entorhinal cortex132,133. Consistent with an important role of interneurons in ensembles, bidirectional plasticity of Parvalbumin (PV) and cholecystokinin (CCK)-expressing interneurons was observed in c-Fos expressing engrams neurons134.

Development of ensembles

As Cajal pointed out, how a system develops can often give deep insights into its function135. Thus, research into the development of ensembles could help understanding their structure, mechanisms and computational purpose. We propose that early developmental programs scaffold the spatial extent and composition of neuronal ensembles. This is supported by two converging lines of evidence: the first one relates to the preconfigured nature of circuit activity and the second links the diversity in intrinsic excitability and connectivity associated with developmental origin.

Let’s recall the definition of an ensemble as a group of neurons that display recurring patterns of coordinated activity. Thus, an essential feature of the ensembles is that they can occur spontaneously, without external stimulation. Consistent with ensembles engaging preexisting existing circuits, despite being prone to experience-dependent plasticity, the cell composition and functional wiring (i.e. activation order) of neural ensembles is remarkably stable across environments and time18,21,22,31,41,46,47,49,69,86,94,105,136,137. In addition, ensemble membership is likely non-random22,69,72 and activated within local circuits with minimal reliance on external inputs22,53,69,71,86. Thus, there could be a finite repertoire of pre-existing ensembles within a given circuit in the adult brain. The fact that neuronal ensembles can be orthogonal or non-overlapping35,76 further constrains the number of possible ensembles a given circuit can produce.

With these constrains, it is interesting to discuss when and how a predetermined pool of ensembles emerges during development and to disentangle the respective contributions of the developmental genetic program and experience in this process. There is a growing body of indirect evidence suggesting that the repertoire of neuronal ensembles may be partly genetically predetermined as early as embryogenesis. As discussed, ensemble membership and latency to fire within a given ensemble appear mostly determined by intrinsic excitability and local connectivity22,69,76,131,138 with both parameters partly rooted in the time of neurogenesis of individual neurons43,139–143. For example, the intrinsic excitability of CA1 pyramidal neurons reflects their embryonic birthdate140, which may explain their differential participation to neuronal ensembles69,144. The idea that ensembles are partly constrained by genetic programs is further supported by lineage analysis indicating that sister pyramidal neurons in the neocortex are most likely to be synaptically coupled within cortical columns (Figure 6B3), the same way that neurons in ensembles share similar receptive fields145–147.

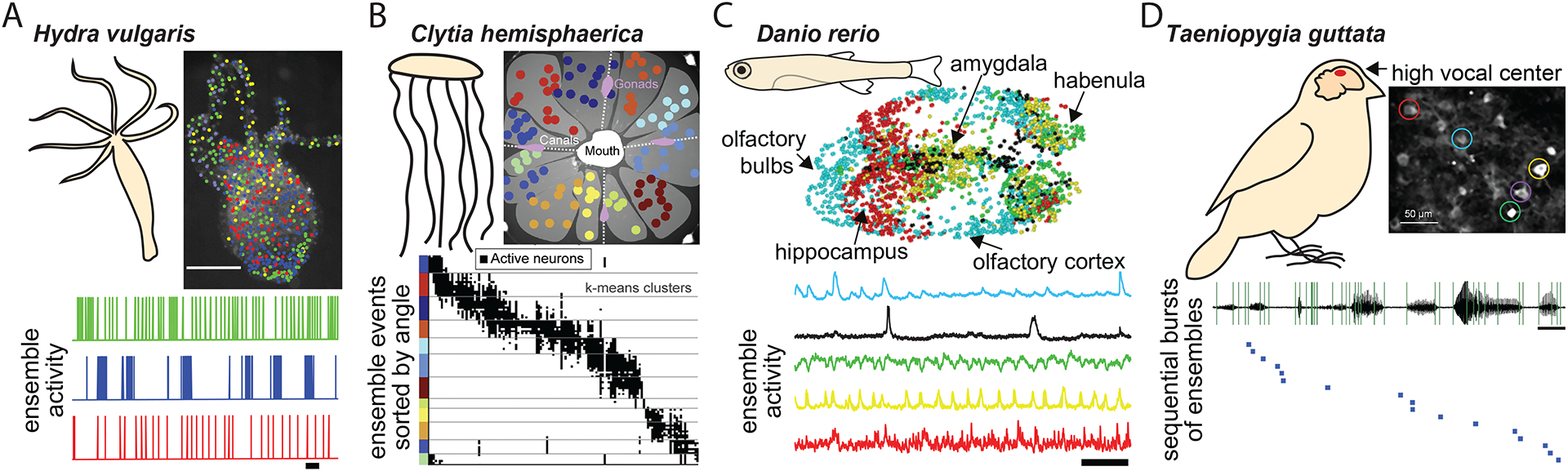

Figure 6. Neuronal ensembles in non-mammalian species.

(A) Calcium imaging of the activity of the entire nervous system of Hydra vulgaris reveals ensembles of coactive neurons (color-coded). (B) Neural ensembles in distinct divisions of the body of the jellyfish Clytia hemisphaerica display synchronized calcium signals (color-coded). (C) Ensembles of neurons in anatomically distinct zones of juvenile zebrafish forebrain exhibit highly correlated ongoing calcium activity (color-coded). (D) Electrophysiological recordings of sequential activation of neurons in high vocal center of songbird during song generation reveals a stereotyped activity pattern. Figures adapted from46,56,229,239.

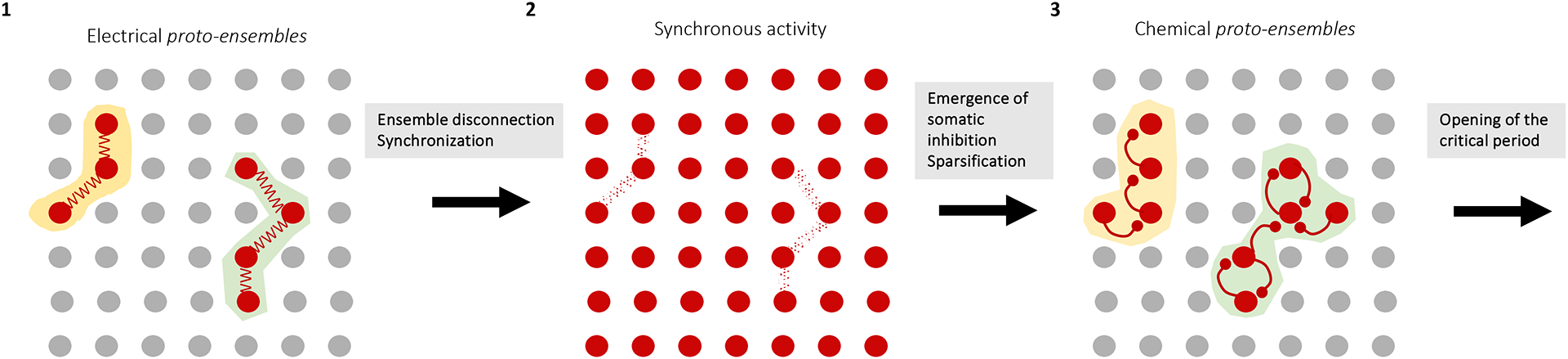

In our view, “proto-ensembles” would first emerge from sparse groups of co-active neurons coupled through electrical synapses (Figure 5–1). These are observed around birth in the cortex of rodents, which would correspond to the start of the last trimester of gestation in humans. Transient electrically-coupled ensembles have been reported in different species and throughout the nervous system including the spinal cord, neocortex, hippocampus and retina.16,17,148–151. Gap-junctional coupling may therefore represent a universal phenomenon to generate a developmental blueprint for ensemble construction. Which neurons join an ensemble remains to be established but there is a bias for spatially clustered cells to belong to the same ensemble (Figure 5–1),16;43) as well as for cells sharing a similar lineage152 or birthdate153,43. However, early ensembles, including cortical Synchronous Plateau Assemblies (SPAs) have pyramidal cells and interneurons148,153 a composition that is necessary for adult ensembles given the dual role of interneurons in organizing and suppressing ensembles22,26,76,154. These early coactive groups of neurons could thus represent proto-ensembles155,156, as suggested by early experiments in the developing neocortex where co-active neurons by means of gap-junctions span several layers in a column-like fashion16. Activity within these proto-ensembles mainly takes the form of calcium transients, associated148,149,153,157 or not158 with action-potential bursts (Figure 5–1). In the former case, calcium transients are critically influenced by intrinsic excitability as determined by active conductances including the H-current148. The minimal reliance on external inputs for the formation of these proto-ensembles is supported by the fact that they do not match the barrels in the somatosensory cortex16. However, pioneer transient neurons, such as subplate cells or subcerebral projecting neurons, may be critically involved in organizing these proto-ensembles149 ,159The function of these early proto-ensembles remains to be established but is likely to be linked to the integration of cells into local circuits as well as their long-range axonal path-finding. An example of the latter can be found in the developing spinal cord where motoneurons coupled by gap-junctions innervate the same muscle, and gap junction elimination gates the transition between multiple to single innervation160. Regarding the former, the integrated activity within proto-ensembles may locally regulate the balance between excitation and inhibition before crystalizing as functional units, a process that may involve developmental apoptosis, which was is also regulated at ensemble level161.

Figure 5: Stepwise model of ensemble development.

Cartoon schematizing three steps of cortical ensemble development taking place before the start of the critical period: proto-ensembles connected through electrical synapses (1) are followed by highly synchronous population activity (2) and sparse, synaptically-connected ensembles, constrained by somatic inhibition (3), resulting in two ensembles.

After proto-ensembles, the next step in the development of neuronal ensembles starts with the emergence of chemical synaptic transmission and more specifically of local recurrent connections148,149,153,162. This happens towards the end of the first postnatal week in rodents, which roughly corresponds to the end of gestation in humans. This is likely a two-stage process, with first an expansion of neuronal ensembles from local spatially isolated clusters to larger territories163,164 (Figure 5–2) and later a sparsification through the maturation of GABAergic assemblies just before the start of active exploration (Figure 5–3). Of note, chemical synapses actively suppress electrical ones148,165} while in turn electrical synapses contribute to the maturation of chemical synapses within ensembles166. Hence blockade of gap-junction mediated communication between sister neurons impairs the subsequent formation of specific chemical synapses between them within ontogenetic cortical columns152. Whether some of these electrical synapses are maintained, for example in the AIS or axon, their location and the mechanisms by which they are progressively replaced by chemical ones remain open questions167. After this, chemical protoensembles receive spontaneous, synapse-driven activity conveying bottom-up information from the sensory periphery which itself is still insensitive to environmental sensory stimuli (visual, auditory) or from spontaneous movement feedback in the somatosensory system. This enables the pre-calibration of the connectivity and excitability of proto-ensembles to the statistics of the body and sensory organs, prior to exploration of the external world.

As a final step, the start of active behavioral exploration, which happens towards the end of the second postnatal week in rodents, marks the opening of experience-dependent plasticity of cortical ensembles168,169. It remains to be established when ensembles comparable to the ones reported in the adult emerge as well as their evolution from the proto-ensemble blueprint during critical periods. One possibility could be that the realm of plasticity available for a given adult ensemble will be included in the initial extent of proto-ensembles and regulated by intrinsic excitability and local inhibition.

Challenges and open questions

Ensembles are not, by any means, the only circuit basis for brain function, yet they provide an interesting framework to describe the functional organization of neural circuits, and a possible bridge from single neuronal activity to brain function, discretizing population activity into modular units. Thus, ensembles could help solve a fundamental tension in neuroscience between the roles of individual neurons vs. neuronal populations in cognition170. Conceptual solutions, anchored on the behavior of the animal, are critical to finding a middle ground between reductionism and emergent phenomena171.

The correlation between the appearance of ensembles and sensory responses or behavior48,98–101 suggests that ensembles have a functional role. This is supported by the optogenetic manipulation of ensembles leading to the control of perceptual states37,88,104, which demonstrated that ensemble activity was both necessary and sufficient for a visual discrimination behavior37,88. This confirms that ensembles are not epiphenomena of population activity but veritable functional circuit units. Nevertheless, our understanding of the biology of ensembles is still limited and many of the questions raised at the beginning of this article remain open. Adding to the results from mammalian hippocampus and neocortex reviewed above, it is necessary to explore the potential existence and function of ensembles in other brain areas. Initial results suggest that ensembles are present in many brain areas and species (Box 3) and the study of simpler preparations could help solve experimental challenges. For example, neurons in ensembles are not contiguous, and ensembles are often not constrained to particular circuit territories or even to particular regions of the nervous system. Therefore, to identify ensembles rigorously one would need to sample the activity of the entire nervous system with cellular resolution, including both neurons and glia. Whole-brain cellular imaging is already possible in small, transparent animals, like Hydra56, C. elegans172 or zebrafish larva173 and the development of large scale imaging methods fueled by the US and International BRAIN initiatives174–176 could help extend whole brain cellular resolution imaging to other preparations (Figure 6). Similar challenges apply to experimental methods to perturb ensembles, necessary to explore their functional roles. These methods need to have adequate temporal resolution, single-cell resolution and be deployable in a parallel fashion throughout the extent of an ensemble, potentially encompassing the entire brain. Classical physiology used electrical macrostimulation, or pharmacology (or neuromodulation) to probe alterations in ensemble connectivity and function. More recently, holographic two-photon optogenetics130,177–179 or optochemistry180, have been used and combined with imaging in an all-optical fashion, with single cell precision181. These functional approaches should be complemented with anatomical methods to reconstruct the connectivity of ensembles. Dense EM reconstructions of connectivity182,183 and molecular methods such as GRASP184 appear promising but are also hampered by the potential need to extend these reconstructions to the entire brains. With these large-scale methods many practical questions could be tackled. For example, what minimum number of neurons constitutes an ensemble? What exactly is the space and time extent of ensembles? Does one need to record from every neuron? Can the size of ensembles change due to plasticity or state alterations? Solving these questions can provide rigorous arguments to evaluate the role of ensembles in neural circuits. Given the importance of development in shaping the functional organization of adult circuits, relating ensemble generation or activation to their developmental origin could help guide some of these questions.

Box 3: Ensembles beyond mammalian cortex and hippocampus.

Recurrent connectivity, and neural ensembles are observed across the brain, beyond the mammalian neocortex and hippocampus (Figure 6). Hence, motor pattern generating circuits, are good examples of how ensemble activity can lead to distinct programs not only in the motor cortex224 but also in the rest of the nervous system. In humans, multi-unit recordings of subthalamic nuclei in Parkinson’s Disease patients revealed pairwise synchronous activation of tremor and movement direction-related neuronal ensembles that are partially overlapping225. Striatal ensembles were shown to generate sequentially patterned activity during motor learning225 and to be organized spatiotemporally for encoding action space226. Similarly, ensembles of cerebellar Purkinje cells are associated with distinct motor actions and they are regulated by animals’ behavioral states227. Highly coordinated ensemble activity that is associated with locomotor rhythms are also observed across vertebrate spinal cord228. Finally, while birds do not have a motor cortex, high vocal center (HVC) and robust nucleus of the archistriatum (RA) in the forebrain of songbirds are good examples of how neural ensembles can learn and generate sequences217,229 (Figure 7D).

Brain regions associated with switching animal’s internal states were also reported to utilize neural ensembles for various functions. Calcium imaging in mammalian amygdala230 and zebrafish raphe231 revealed distinct ensemble activation, when animals switch between exploratory and nonexploratory states. Similarly, coactivated ensembles of neurons associated with animals’ adaptive behaviors were observed in the habenula43,51,232,233 as well as its inputs at the lateral hypothalamus234,235. It is yet to be discovered whether these ensembles are generated due to recurrent connectivity of these brain regions or driven by the inputs from higher brain centers46 (Figure 7 C). In fact, highly distributed neural ensemble activity associated with internal states of animals were demonstrated successfully in invertebrate brains such as Caenorhabditis elegans236, Drosophila melanogaster237,238 and evolutionary distant animals without even ganglia, such as the cnidarians Hydra vulgaris56 and Clytia hemisphaerica239 (Figure 7 A, B).

There are also challenges with the analytical and computational methods employed to detect ensembles. There are many different approaches to detect ensembles, ranging from simple thresholds or template matching, to dimensionality reduction algorithms, to Markovian chains, to graph theory models94,185,186 (Box 2). While many methods are based on detection of zero-lag correlations, covariance, or functional connectivity, the statistical detection of sequential activity has often led to major disagreements93,187–190. A similar analytical problem applies to sequential activity within an ensemble or within hierarchies of ensembles. As of today, there is not an ideal analytical method, as each of them has advantages and disadvantages and is particularly suited to a specific experimental method used. Further statistical or computational research is needed to specifically develop robust methods to capture and characterize ensembles and, more generally, emergent states of circuit activity. Perhaps inspiration and methods could be drawn from other fields where emergent properties have been studied and modeled, such as condensed matter physics, complex systems, network theory, or even linguistics and speech recognition.

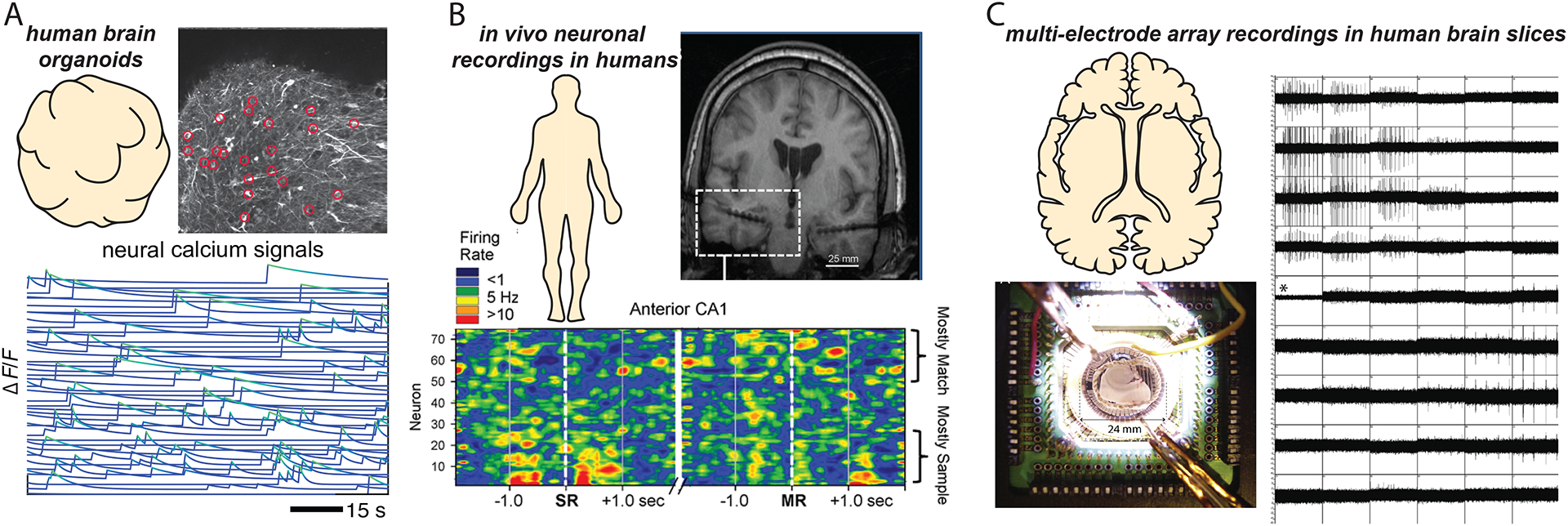

Finally, essentially all knowledge gathered about ensembles stems from experimental animal preparations, with an almost complete ignorance of how these mechanisms play out in the human brain. Tantalizing data from human organoids, or recordings from human brain slices or patients appear consistent with the ensemble hypothesis (Figure 7). Although the basic structure and function of ensembles could be conserved across species191, the human neocortex has undergone a massive evolutionary expansion with potential major changes in its microcircuits, arising from protracted developmental proliferation phases and the appearance of novel cellular subtypes192. Indeed, initial exploration of the structural and functional properties of human cortical circuits reveal important differences with respect to mice193–198. The recent development of methods to functionally probe human circuits199–201 besides providing fundamental information to understand the pathophysiology of mental and neurological diseases, and generate potential new therapeutics, could also provide an exciting new field of investigation to potentially build a bridge between the activity of individual neurons and human cognition, as a central goal of neuroscience.

Figure 7: Potential ensembles in human neocortex.

(A) Top: Example of human brain organoids expressing transgenic calcium indicators. Bottom” spontaneous activity demonstrate coordinated population events. (B) Top: Spatially targeted multi-neural recording electrodes during neurosurgery to record the activity of large neural populations of human neurons, in vivo. Bottom: Synchronized activity in neuronal populations in hippocampus. (C) Multicellular extracellular recordings from human brain slices of tissue resected during brain surgery demonstrates synchronized activity of neuronal populations. Figures are adapted from199–201.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ramón y Cajal S (1899). La Textura del Sistema Nerviosa del Hombre y los Vertebrados (Moya; (Primera Edicion)). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sherrington CS (1906). Observations on the scratch-reflex in the spinal dog. Journal of Physiology 34,, 1–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lorente de No R (1938). Analysis of the activity of the chains of internuncial neurons. J. Neurophysiol 1, 207–244. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hebb DO (1949). The organization of behaviour (Wiley; ). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Semon R (1904). Die Mneme. Engelmann W. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marr D (1971). Simple memory: a theory for archicortex. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 262, 23–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hopfield JJ (1982). Neural networks and physical systems with emergent collective computational abilities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79, 2554–2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hopfield JJ, and Tank DW (1985). “Neural” computation of decissions in optimization problems. Biol. Cybern 52, 141–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hopfield JJ, and Tank DW (1986). Computing with neural circuits: A model. Science 233, 625–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abeles M (1991). Corticonics. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kant I (1781). Kritik der reinen Vernunft (Reclam; (1966 Edition)). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grinvald A, Arieli A, Tsodyks M, and T. K (2003). Neuronal assemblies: Single cortical neurons are obedient members of a huge orchestra. Biopolymers 68, 422–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson MA, and McNaughton BL (1994). Reactivation of hippocampal ensemble memories during sleep. Science 265, 676–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buzsaki G, and Chrobak JJ (1995). Temporal structure in spatially organized neuronal ensembles: a role for interneuron networks. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol 5, 504–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grewe BF, and Helmchen F (2009). Optical probing of neuronal ensemble activity. Current opinion in neurobiology 19, 520–529. 10.1016/j.conb.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuste R, Peinado A, and Katz LC (1992). Neuronal Domains in Developing Neocortex. Science 257, 665–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yuste R, Nelson D, Rubin W, and Katz LC (1995). Neuronal domains in developing neocortex: mechanisms of coactivation. Neuron 14, 7–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ikegaya Y, Aaron G, Cossart R, Aronov D, Lampl I, Ferster D, and Yuste R (2004). Synfire chains and cortical songs: temporal modules of cortical activity. Science (New York, N.Y.) 304, 559–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beggs JM, and Plenz D (2004). Neuronal avalanches are diverse and precise activity patterns that are stable for many hours in cortical slice cultures. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 24, 5216–5229. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0540-04.2004 24/22/5216 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris KD (2005). Neural signatures of cell assembly organization. Nat Rev Neurosci 6, 399–407. nrn1669 [pii] 10.1038/nrn1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luczak A, McNaughton BL, and Harris KD (2015). Packet-based communication in the cortex. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 16, 745–755. 10.1038/nrn4026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stark E, Roux L, Eichler R, and Buzsaki G (2015). Local generation of multineuronal spike sequences in the hippocampal CA1 region. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, 10521–10526. 10.1073/pnas.1508785112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roux L, and Buzsáki G (2015). Tasks for inhibitory interneurons in intact brain circuits,. Neuropharmacology 88, 10–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van de Ven GM, Trouche S, McNamara CG, Allen K, and Dupret D (2016). Hippocampal Offline Reactivation Consolidates Recently Formed Cell Assembly Patterns during Sharp Wave-Ripples. Neuron 92, 968–974,. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holtmaat A, and Caroni P (2016). Functional and structural underpinnings of neuronal assembly formation in learning. Nat Neurosci 19, 1553–1562. 10.1038/nn.4418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buzsaki G (2010). Neural syntax: cell assemblies, synapsembles, and readers. Neuron 68, 362–385. 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finkelstein A, Fontolan L, Economo M, Li N, Romani S, and Svoboda K (2021). Attractor dynamics gate cortical information flow during decision-making. Nature Neuroscience 24, 1–8. 10.1038/s41593-021-00840-6. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harvey CD, Coen P, and Tank DW (2012). Choice-specific sequences in parietal cortex during a virtual-navigation decision task. Nature 484, 62–68. 10.1038/nature10918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inagaki H, Fontolan L, Romani S, and Svoboda K (2019). Discrete attractor dynamics underlies persistent activity in the frontal cortex. 0.1038/s41586-019-0919-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Churchland MM, Cunningham JP, Kaufman MT, Foster JD, Nuyujukian P, Ryu SI, and Shenoy KV (2012). Neural population dynamics during reaching. Nature 487, 51–56. 10.1038/nature11129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luczak A, Bartho P, and Harris KD (2009). Spontaneous events outline the realm of possible sensory responses in neocortical populations. Neuron 62, 413–425. 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamiński J, Sullivan S, Chung J, Ross I, Mamelak A, and Rutishauser U (2017). Persistently active neurons in human medial frontal and medial temporal lobe support working memory. Nature neuroscience 20. 10.1038/nn.4509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gardner R, Hermansen E, Pachitariu M, Burak Y, Baas N, Dunn B, Moser M-B, and Moser E (2022). Toroidal topology of population activity in grid cells. Nature 602, 1–6. . 10.1038/s41586-021-04268-7. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harris KD, Csicsvari J, Hirase H, Dragoi G, and Buzsaki G (2003). Organization of cell assemblies in the hippocampus. Nature 424, 552–556. 10.1038/nature01834 nature01834 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malvache A, Reichinnek S, Villette V, Haimerl C, and Cossart R (2016). Awake hippocampal reactivations project onto orthogonal neuronal assemblies. Science 353, 1280–1283. 10.1126/science.aaf3319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carrillo-Reid L, Yang W, Bando Y, Peterka DS, and Yuste R (2016). Imprinting and recalling cortical ensembles. Science 353, 691–694. 10.1126/science.aaf7560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carrillo-Reid L, Han Shuting, Yang Weijian, Akrough Alejandro, Yuste Rafael(2019). Controlling Visually Guided Behavior by Holographic Recalling of Cortical Ensembles. Cell 178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mòdol L, Bollmann Y, Tressard T, Baude A, Che A, Duan Z, Babij R, De Marco Garcia N, and Cossart R (2019). Assemblies of Perisomatic GABAergic Neurons in the Developing Barrel Cortex. Neuron 105. 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.10.007. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wenzel M, Hamm JP, Peterka DS, and Yuste R (2019). Acute Focal Seizures Start As Local Synchronizations of Neuronal Ensembles. Journal of Neuroscience 39, 8562–8575. 10.1523/Jneurosci.3176-18.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wenzel M, Han S, Smith EH, Hoel E, Greger B, House PA, and Yuste R (2019). Reduced Repertoire of Cortical Microstates and Neuronal Ensembles in Medically Induced Loss of Consciousness. Cell Syst 8, 467–474 e464. 10.1016/j.cels.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haimerl C, Angulo-Garcia D, Villette V, Reichinnek S, Torcini A, Cossart R, and Malvache A (2019). Internal representation of hippocampal neuronal population spans a time-distance continuum. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 116, 7477–7482. 10.1073/pnas.1718518116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheintuch L, Geva N, Deitch D, Rubin A, and Ziv Y (2023). Organization of hippocampal CA3 into correlated cell assemblies supports a stable spatial code. Cell Reports. 42, 112119. 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fore S, Acuna-Hinrichsen F, Mutlu KA, Bartoszek EM, Serneels B, Faturos NG, Chau KTP, Cosacak MI, Verdugo CD, Palumbo F, et al. (2020). Functional properties of habenular neurons are determined by developmental stage and sequential neurogenesis. Science Advances 6. ARTN eaaz3173 10.1126/sciadv.aaz3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pettit N, Yuan X, and Harvey C (2022). Hippocampal place codes are gated by behavioral engagement. Nature Neuroscience 25, 1–6. 10.1038/s41593-022-01050-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Truccolo W, Ahmed OJ, Harrison MT, Eskandar EN, Cosgrove GR, Madsen JR, Blum AS, Potter NS, Hochberg LR, and Cash SS (2014). Neuronal ensemble synchrony during human focal seizures. J Neurosci 34, 9927–9944. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4567-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bartoszek EM, Ostenrath AM, Jetti SK, Serneels B, Mutlu AK, Chau KTP, and Yaksi E (2021). Ongoing habenular activity is driven by forebrain networks and modulated by olfactory stimuli. Curr Biol 31, 3861–3874 e3863. 10.1016/j.cub.2021.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cossart R, Aronov D, and Yuste R (2003). Attractor dynamics of network UP states in neocortex. Nature 423, 283–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller JE, Ayzenshtat I, Carrillo-Reid L, and Yuste R (2014). Visual stimuli recruit intrinsically generated cortical ensembles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111, E4053–4061. 10.1073/pnas.1406077111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luczak A, Bartho P, Marguet SL, Buzsaki G, and Harris KD (2007). Sequential structure of neocortical spontaneous activity in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104, 347–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leighton AH, Cheyne JE, Houwen GJ, Maldonado PP, De Winter F, Levelt CN, and Lohmann C (2021). Somatostatin interneurons restrict cell recruitment to retinally driven spontaneous activity in the developing cortex. Cell Rep 36, 109316. 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jetti SK, Vendrell-Llopis N, and Yaksi E (2014). Spontaneous Activity Governs Olfactory Representations in Spatially Organized Habenular Microcircuits. Current Biology 24, 434–439. 10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Plenz D, and Kitai ST (1998). Up and down states in striatal medium spiny neurons simultaneously recorded with spontaneous activity in fast-spiking interneurons studied in cortex-striatum-substantia nigra organotypic cultures. J Neurosci 18, 266–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsodyks M, Kenet T, Grinvald A, and Arieli A (1999). Linking spontaneous activity of single cortical neurons and the underlying functional architecture. Science 286, 1943–1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mao BQ, H.-S. F, Aronov D, Froemke RC, and Yuste R (2001). Dynamics of spontaneous activity in neocortical slices. Neuron 32, 833–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Berger H (1929). Über das Elektrenkephalogramm des Menschen. Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten 87, 527–570. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dupre C, and Yuste R (2017). Non-overlapping Neural Networks in Hydra vulgaris. Curr Biol. 10.1016/j.cub.2017.02.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Levin M, and Yuste R (2022). Modular cognition. Aeon Essays. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yuste R, and Levin M (2021). New Clues about the Origins of Biological Intelligence. Scientific American December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Drieu C, Todorova R, and Zugaro M (2018). Nested sequences of hippocampal assemblies during behavior support subsequent sleep replay. Science 362, 675.-+. 10.1126/science.aat2952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Itskov V, Pastalkova E, Mizuseki K, Buzsaki G, and Harris KD (2008). Theta-mediated dynamics of spatial information in hippocampus. Journal of Neuroscience 28, 5959–5964. 10.1523/Jneurosci.5262-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kraus BJ, Robinson RJ 2nd, White JA, Eichenbaum H, and Hasselmo ME (2013). Hippocampal “time cells”: time versus path integration. Neuron 78, 1090–1101. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pastalkova E, Itskov V, Amarasingham A, and Buzsaki G (2008). Internally generated cell assembly sequences in the rat hippocampus. Science 321, 1322–1327. 321/5894/1322 [pii] 10.1126/science.1159775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Villette V, Malvache A, Tressard T, Dupuy N, and Cossart R (2015). Internally Recurring Hippocampal Sequences as a Population Template of Spatiotemporal Information. Neuron 88, 357–366. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aery Jones EA, and Giocomo LM (2023). Neural ensembles in navigation: From single cells to population codes. Curr Opin Neurobiol 78, 102665. 10.1016/j.conb.2022.102665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee AK, and Wilson MA (2002). Memory of sequential experience in the hippocampus during slow wave sleep. Neuron 36, 1183–1194. S0896627302010966 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Skaggs WL, and McNaughton BL (1996). Replay of neuronal firing sequences in rat hippocampus during sleep following spatial experience. Science 271, 1870–1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.El-Gaby M, Reeve HM, Lopes-dos-Santos V, Campo-Urriza N, Perestenko PV, Morley A, Strickland LAM, Lukacs IP, Paulsen O, and Dupret D (2021). An emergent neural coactivity code for dynamic memory. Nature Neuroscience 24, 694–704. 10.1038/s41593-021-00820-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zugaro MB, Arleo A, Déjean C, Burguière E, Khamassi M, and Wiener SI (2004). Rat anterodorsal thalamic head direction neurons depend upon dynamic visual signals to select anchoring landmark cues. European Journal of Neuroscience 20, 530–536. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee JS, Briguglio JJ, Cohen JD, Romani S, and Lee AK (2020). The Statistical Structure of the Hippocampal Code for Space as a Function of Time, Context, and Value. Cell 183, 620.-+. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rolotti SV, Blockus H, Sparks FT, Priestley JB, and Losonczy A (2022). Reorganization of CA1 dendritic dynamics by hippocampal sharp-wave ripples during learning. Neuron DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2021.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zutshi I, Valero M, Fernandez-Ruiz A, and Buzsaki G (2022). Extrinsic control and intrinsic computation in the hippocampal CA1 circuit. Neuron 110, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dragoi G, and Tonegawa S (2011). Preplay of future place cell sequences by hippocampal cellular assemblies. Nature 469, 397–401. nature09633 [pii] 10.1038/nature09633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Grosmark AD, and Buzsaki G (2016). Diversity in neural firing dynamics supports both rigid and learned hippocampal sequences. Science 351, 1440–1443. 10.1126/science.aad1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Leibold C (2020). A model for navigation in unknown environments based on a reservoir of hippocampal sequences. Neural Networks 124, 328–342. 10.1016/j.neunet.2020.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Huszar R, Zhang Y, Blockus H, and Buzsaki G (2022). Preconfigured dynamics in the hippocampus are guided by embryonic birthdate and rate of neurogenesis. Nat Neurosci 25, 1201–1212. 10.1038/s41593-022-01138-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Agetsuma M, Hamm JP, Tao K, Fujisawa S, and Yuste R (2018). Parvalbumin-Positive Interneurons Regulate Neuronal Ensembles in Visual Cortex. Cerebral Cortex 28, 1831–1845. 10.1093/cercor/bhx169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Royer S, Zemelman BV, Losonczy A, Kim J, Chance F, Magee JC, and Buzsaki G (2012). Control of timing, rate and bursts of hippocampal place cells by dendritic and somatic inhibition. Nature Neuroscience 15, 769–775. 10.1038/nn.3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gridchyn I, Schoenenberger P, O’Neill J, and Csicsvari J (2020). Assembly-Specific Disruption of Hippocampal Replay Leads to Selective Memory Deficit. Neuron 106, 291.-+. 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jadhav SP, and Frank LM (2014). Memory Replay in the Hippocampus. Space, Time and Memory in the Hippocampal Formation, 351–371. 10.1007/978-3-7091-1292-2_13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Girardeau G, Benchenane K, Wiener SI, Buzsáki G, and Zugaro MB (2009). Selective suppression of hippocampal ripples impairs spatial memory. Nature Neuroscience 12, 1222–1223. 10.1038/nn.2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fernández-Ruiz A, Oliva A, Nagy GA, Maurer AP, Berényi A, and Buzsáki G (2017). Entorhinal-CA3 Dual-Input Control of Spike Timing in the Hippocampus by Theta-Gamma Coupling. Neuron 93, 1213.-+. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tonegawa S, Morrissey MD, and Kitamura T (2018). The role of engram cells in the systems consolidation of memory. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 19, 485–498. 10.1038/s41583-018-0031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tanaka K, He H, Tomar A, Niisato K, Huang A, and Mchugh T (2016). The hippocampal engram maps experience but not place. Science 361, 392–397. 10.1126/science.aat5397. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jou C, and Fenton AA (2023). On the results of causal optogenetic engram manipulations. BioRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Arieli A, Sterkin A, Grinvald A, and Aertsen A (1996). Dynamics of ongoing activity: explanation of the large variability in evoked cortical responses. Science 273, 1868–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.MacLean JN, Watson BO, Aaron GB, and Yuste R (2005). Internal dynamics determine the cortical response to thalamic stimulation. Neuron 48, 811–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jennings JH, Kim CK, Marshel JH, Raffiee M, Ye L, Quirin S, Pak S, Ramakrishnan C, and Deisseroth K (2019). Interacting neural ensembles in orbitofrontal cortex for social and feeding behaviour. Nature 565, 645–649. 10.1038/s41586-018-0866-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Marshel JH, Kim YS, Machado TA, Quirin S, Benson B, Kadmon J, Raja C, Chibukhchyan A, Ramakrishnan C, Inoue M, et al. (2019). Cortical layer-specific critical dynamics triggering perception. Science 365. 10.1126/science.aaw5202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Helmchen F, and Konnerth A, ed. (2011). Imaging in Neuroscience: A Laboratory Manual (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; ). [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rabadan MA, De La Cruz D, Rao S, Chen Y, Gong C, Crabtree G, Xu B, Markx S, Gogos J, Yuste R, and Tomer R (2022). An in vitro model of neuronal ensembles. . Nature Communications. 13. . 10.1038/s41467-022-31073-1. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Molnar G, Olah S, Komlosi G, Fule M, Szabadics J, Varga C, Barzo P, and Tamas G (2008). Complex events initiated by individual spikes in the human cerebral cortex. PLoS biology 6, e222. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hemberger M, Shein-Idelson M, Pammer L, and Laurent G (2019). Reliable Sequential Activation of Neural Assemblies by Single Pyramidal Cells in a Three-Layered Cortex. Neuron 104, 353.-+. 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Abeles M, Bergman H, Margalit E, and Vaadia E (1993). Spatiotemporal firing patterns in the frontal cortex of behaving monkeys. J. Neurophysiol 70, 1629–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Carrillo-Reid L, Miller J-EK, Hamm JP, Jackson J, and Yuste R (2015). Endogenous sequential cortical activity evoked by visual stimuli. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 35, 8813–8828. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5214-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lines J, and Yuste R (2023). Visually evoked neuronal ensembles reactivate during sleep. BioRXiV. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Watson BO, MacLean JN, and Yuste R (2008). UP states protect ongoing cortical activity from thalamic inputs. PLoS One 3, e3971. 10.1371/journal.pone.0003971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kenet T, Bibitchkov D, Tsodyks M, Grinvald A, and Arieli A (2003). Spontaneously emerging cortical representations of visual attributes. Nature. 425, 954–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ayzenshtat I, Meirovithz E, Edelman H, Werner-Reiss U, Bienenstock E, Abeles M, and Slovin H (2010). Precise spatiotemporal patterns among visual cortical areas and their relation to visual stimulus processing. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 30, 11232–11245. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5177-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Seidemann E, Meilijson I, Abeles M, Bergman H, and Vaadia E (1996). Simultaneously recorded single units in the frontal cortex go through sequences of discrete and stable states in monkeys performing a delayed localization task. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 16, 752–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhou J, Jia C, Montesinos-Cartagena M, Gardner M, Zong W, and Schoenbaum G (2021). Evolving schema representations in orbitofrontal ensembles during learning. Nature 590, 10.1038/s41586-41020-03061-41582. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nieh E, Schottdorf M, Freeman N, Low R, Lewallen S, Koay S, Pinto L, Gauthier J, Brody C, and Tank D (2021). Geometry of abstract learned knowledge in the hippocampus. Nature 595, 10.1038/s41586-41021-03652-41587. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ahissar E, Vaadia E, Ahissar M, Bergman H, Arieli A, and Abeles M (1992). Dependence of cortical plasticity on correlated activity of single neurons and on behavioral context. Science 257, 1412–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Choi G, Stettler D, Kallman B, Bhaskar S, Fleischmann A, and Axel R (2011). Driving Opposing Behaviors with Ensembles of Piriform Neurons. Cell 146, 1004–1015. . 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Russell LE, Yang Z, Tan PL, Fişek M, Packer AM, Dalgleish HWP, Chettih S, Harvey CD, and Häusser M (2019). The influence of visual cortex on perception is modulated by behavioural state. bioRxiv, 706010. 10.1101/706010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Perez-Ortega J, Alejandre-Garcia T, and Yuste R (2021). Long-term stability of cortical ensembles. Elife 10. ARTN e64449 10.7554/eLife.64449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Driscoll L, Pettit N, Minderer M, Chettih S, and Harvey CD (2017). Dynamic Reorganization of Neuronal Activity Patterns in Parietal Cortex. Cell 170. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.021. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rule M, O’Leary T, and Harvey CD (2019). Causes and consequences of representational drift. Current opinion in neurobiology. 58, 141–147. . 10.1016/j.conb.2019.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ziv Y, Burns LD, Cocker ED, Hamel EO, Ghosh KK, Kitch LJ, El Gamal A, and Schnitzer MJ (2013). Long-term dynamics of CA1 hippocampal place codes. Nature neuroscience 16, 264–266. 10.1038/nn.3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Schoonover C, Ohashi S, Axel R, and Fink A (2021). Representational drift in primary olfactory cortex. Nature 594, 1–6. 10.1038/s41586-021-03628-7. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Markram H, Lubke J, Frotscher M, and Sakmann B (1997). Regulation of synaptic efficacy by coincidence of postsynaptic APs and EPSPs. Science 275, 213–215. 10.1126/science.275.5297.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bi GQ, and Poo MM (1998). Synaptic modifications in cultured hippocampal neurons: dependence on spike timing, synaptic strength, and postsynaptic cell type. J Neurosci 18, 10464–10472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Titley HK, Brunel N, and Hansel C (2017). Toward a Neurocentric View of Learning. Neuron 95, 19–32. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ryan TJ, Roy DS, Pignatelli M, Arons A, and Tonegawa S (2015). Engram cells retain memory under retrograde amnesia. Science 348, 1007–1013. 10.1126/science.aaa5542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Abraham WC, Jones OD, and Glanzman DL (2019). Is plasticity of synapses the mechanism of long-term memory storage? Npj Sci Learn 4. ARTN 9 10.1038/s41539-019-0048-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]