Abstract

DNA methylation is a well-studied epigenetic modification that has key roles in regulating gene expression, maintaining genome integrity, and determining cell fate. Precisely how DNA methylation patterns are established and maintained in specific cell types at key developmental stages is still being elucidated. However, research over the last two decades has contributed to our understanding of DNA methylation regulation by other epigenetic processes. Specifically, lysine methylation on key residues of histone proteins has been shown to contribute to the allosteric regulation of DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) activities. In this review, we discuss the dynamic interplay between DNA methylation and histone lysine methylation as epigenetic regulators of genome function by synthesizing key recent studies in the field. With a focus on DNMT3 enzymes, we discuss mechanisms of DNA methylation and histone lysine methylation crosstalk in the regulation of gene expression and the maintenance of genome integrity. Further, we discuss how alterations to the balance of various sites of histone lysine methylation and DNA methylation contribute to human developmental disorders and cancers. Finally, we provide perspectives on the current direction of the field and highlight areas for continued research and development.

Keywords: DNA methylation, histone methylation, gene regulation, cancer, neurodevelopmental disorders

DNA methylation overview

DNA methylation is the covalent chemical addition of a single methyl group to the C5 position of the cytosine ring of DNA to give rise to 5-methylcytosine (5mC). In mammals, this primarily occurs on cytosines that precede a guanine, termed a CpG dinucleotide [1]. However, 5mC can also be found in non-CpG contexts, termed CpH methylation, where H denotes an adenine, cytosine, or thymine. CpH methylation is primarily found in CAC or CAG contexts [2,3]. 5-methylcytosine can be converted to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) by the ten-eleven translocation (TET) family of 5mC dioxygenases [4]. The oxidation of 5mC to 5hmC by the TET enzymes is a part of the active DNA demethylation pathway, in which TET enzymes iteratively oxidize 5mC to 5hmC to 5-formylcytosine and then to 5-carboxycytosine. The final step in active DNA demethylation evokes the base excision repair pathway in which thymine DNA glycosylase cleaves the modified cytosine and it is replaced with an unmodified cytosine. Recent studies have begun to elucidate the biological and pathological functions of 5hmC and the active DNA demethylation pathway, as reviewed elsewhere [5,6]. In contrast, DNA methylation can be removed passively through DNA replication and mitotic cell division in the absence of the DNA methylation maintenance machinery. Replication-coupled passive loss of DNA methylation is thought to be a major mechanism by which the genomes of cancer and aging cells become hypomethylated [7,8].

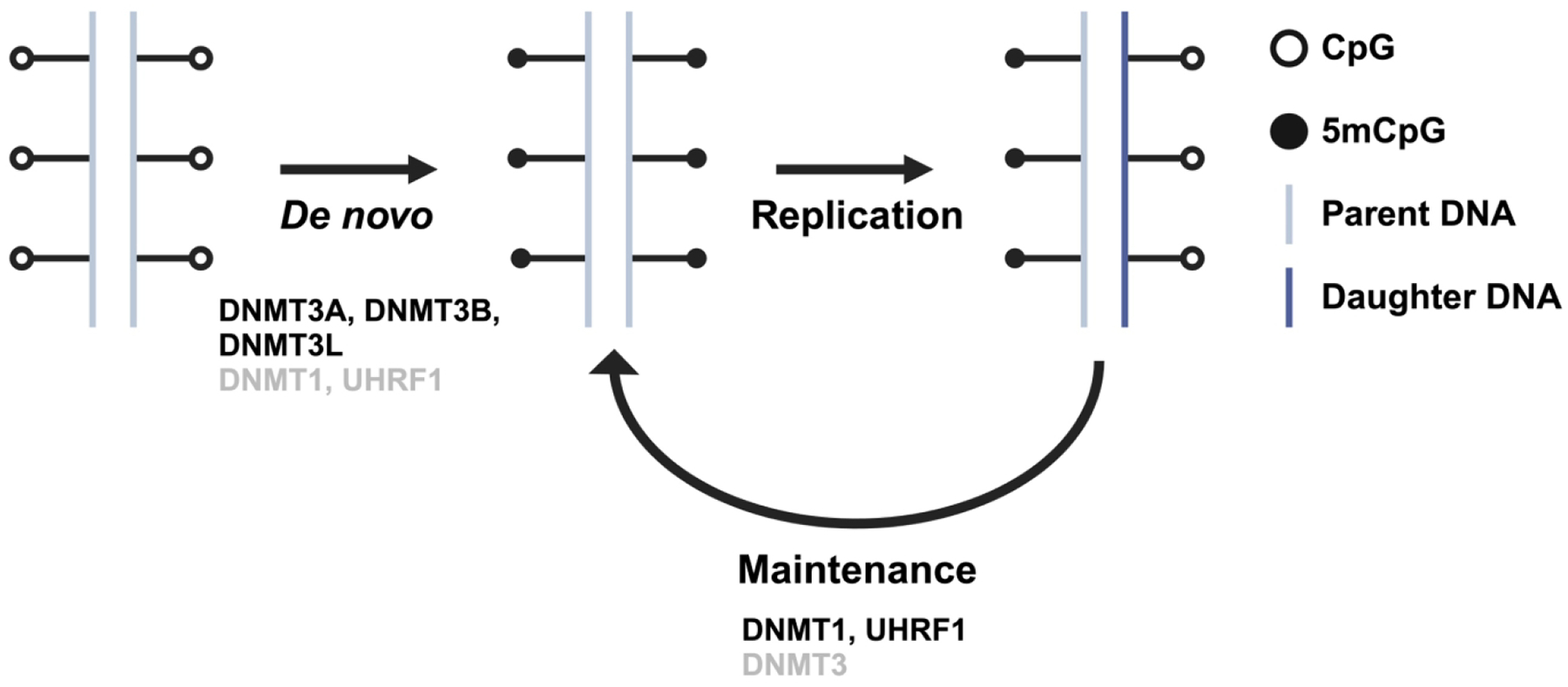

DNA methylation is catalyzed by the DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) family of enzymes: DNMT1, DNMT3A/B, and DNMT3L [1]. The DNMT3 family of enzymes are commonly referred to as the de novo DNMTs due to their key roles in establishing DNA methylation patterns during early embryonic development. These patterns are then maintained by DNMT1, with the help of the E3 ubiquitin ligase UHRF1 [9,10]. The primary function of DNMT1 is to copy parental DNA methylation patterns to newly replicated DNA, ensuring that patterns of DNA methylation are inherited through mitotic cell divisions. This is evidenced primarily by the observation that DNMT1 activity is enhanced on hemi-methylated DNA substrates [9,10]. DNMT3L lacks catalytic activity and is thought to function primarily as a binding partner for DNMT3A/B to help regulate their localization and catalytic activity in embryonic cells. Despite this simplified division of labor, DNMT3A and DNMT3B both have reported maintenance functions [11–14] and DNMT1 has reported de novo activity both in vitro and in vivo [15]. The relationship and function of the different DNMTs in DNA methylation establishment and maintenance is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. DNA Methylation overview.

Schematic representation of DNA methylation establishment and maintenance. Enzymes denoted in black font refer to their well-studied, primary functions. Enzymes denoted in grey font refer to their more recently discovered, secondary functions. Created with Biorender.com

Domain structure of DNMTs and their isoforms

Each member of the DNMT family has a similar overall structure: an N-terminal regulatory region and a C-terminal catalytic region [1,16] (Figure 2). Domains within the N-terminal region facilitate DNMT interaction with other proteins, chromatin, and DNA. These interactions are important for establishing and maintaining DNA methylation in the proper cellular and chromatin contexts to help shape developmental stage and cellular identity. The C-terminal region of the DNMT proteins is comprised of ten conserved amino acid motifs that mediate catalytic function and target recognition. While DNMT3L shares some homology to DNMT3A/B, the C-terminal region contains amino acid substitutions and deletions which explain its lack of targeted catalytic activity [1]. The DNMT1 and DNMT3 family of enzymes differ in their N-terminal regions allowing for cell type-specific functions of the different DNMTs. DNMT3A and DNMT3B are strongly associated with chromatin through their N-termini that harbor histone H3 reading ADD and PWWP domains, and there is very little unbound DNMT3 in the nuclei of colon cancer cells [17] Moreover, the loss of DNA methylation through genetic perturbation of DNMT1 and DNMT3B results in destabilization of DNMT3A protein levels, and DNMT3A protein stability is restored upon partial restoration of DNA methylation levels [18]. These data suggest that DNMT3 enzymes are stabilized by their catalytic product [18]. This mechanism may help to ensure proper DNA methylation propagation during cell divisions, but also may prevent aberrant de novo DNA methylation. Along these lines, DNMT3A/B isolated catalytic domains exhibit greater activity than the full-length proteins, indicating that the N-terminal regulatory domains function to inhibit DNMT3 activity [16]. Though DNMT3A and DNMT3B are 53% similar in primary amino acid sequence, they have distinct roles dictated both by their preferred catalytic substrate and their chromatin interacting partners. One of the ways in which DNMT3A and DNMT3B differ in their catalytic function is through CpG-flanking sequence preference [19,20]. DNMT3A preferably methylates CpGs in a CGCC sequence context, while DNMT3B preferably methylates CpGs in a CGGC context. Furthermore, DNMT3A and DNMT3B, but not DNMT1, are capable of catalyzing CpH methylation [21–23]. DNMT3 interactions with chromatin through the N-terminal region will be discussed in more detail below.

Figure 2: DNMT domain map.

Annotated domain structure of mammalian DNMT proteins. Two isoforms are shown for DNMT3A that are produced by alternative promoter usage. Three isoforms are shown for DNMT3B that are produced by alternative splicing. Abbreviations used: DMAP – DNA methyltransferase associated protein 1 interacting domain. NLS – nuclear localization signal. RFTS – replication foci targeting sequence. BAH1/2 – bromo-adjacent homology domains 1 and 2. UDR – ubiquitin-dependent recruitment. ADD – ATRX-DNMT3-DNMT3L domain. MTase – methyltransferase. Created with Biorender.com

DNMT3A and DNMT3B have several isoforms that are often dysregulated in human cancers [24]. DNMT3A has two isoforms produced through alternative promoter usage: DNMT3A1 and DNMT3A2 (Figure 2). DNMT3A2 has a shortened N-terminal region, which may mediate its localization to euchromatic regions of the genome [25], whereas DNMT3A1 localizes to heterochromatin [24]. Interestingly, DNMT3A2 is upregulated in several types of human cancers [26], suggesting an oncogenic function of this isoform. In contrast, DNMT3B has almost 40 different isoforms that arise from alternative splicing [27,28] (Figure 2). DNMT3B1 is the full-length, canonical isoform which retains catalytic activity and exhibits high expression in embryonic stem cells (ESCs). DNMT3B3 is the second most highly expressed isoform, specifically in somatic tissues [24]. DNMT3B3 lacks two exons within the C-terminal catalytic region and is therefore catalytically inactive. DNMT3B3 has been proposed to function as a binding partner for active DNMTs, similar to DNMT3L. Specifically, inactive DNMT3B isoforms were reported to support DNA methylation deposition within gene bodies [14]. In line with this observation, DNMT3B3 was shown to preferentially enhance DNMT3B2 activity over DNMT3A2, suggesting a cooperative relationship whereby DNMT3L primarily supports DNMT3A2 catalytic activity and DNMT3B3 primarily supports DNMT3B2 catalytic activity [29]. This mechanism may contribute to DNMT3A/B substrate selectivity [14]. The supportive role of DNMT3B3 is further evidenced by a cryo-EM structure of the DNMT3A2-DNMT3B3 heterodimer bound to a nucleosome [26]. In this structure, DNMT3B3 makes contacts with the acidic patch of the nucleosome core. This is a surprising observation which warrants further study of the multivalent interactions of DNMT3B with both the histone H3 tail and the nucleosome core particle. Recently elucidated structures for other chromatin-interacting proteins suggest that protein binding to the acidic patch may serve as a more general nucleosomal docking mechanism for these enzymes to carry out their chromatin-modifying functions [30,31]. Overall, the tissue specific expression, preferred binding partners, and substrate selectivity of the different DNMT3 isoforms highlight the context-dependent functionality of these enzymes and the complexity of DNA methylation establishment and maintenance in mammals.

Biological function and genomic context of DNA methylation

While DNA methylation was first reported in the literature in 1925 [32], it was not until the mid-20th century that its function began to be appreciated. Early DNA methylation studies in bacteria began to elucidate a role for DNA methylation related to bacterial immunity and DNA replication [32]. In 1975, thought-provoking papers from Holliday, Pugh, and Riggs proposed a biological function for DNA methylation in higher order eukaryotic organisms [33,34]. While much of their speculations have proven to be correct, the complexity of DNA methylation and its context-dependent functionality are still being elucidated. Broadly speaking, DNA methylation is required for development in mammals [35,36] and is also necessary for growth and proliferation of cancer cells in culture [37]. Discussed below are the biological functions associated with DNA methylation (particularly in a CpG context) within various genomic regions.

Transcription start sites

Many of the early studies of the functional relevance of DNA methylation have focused on the role of DNA methylation in silencing genes through methylation of their promoter regions. An important factor to consider is whether these promoter regions, which encompass the transcription start site (TSS), contain a CpG island. CpG islands (CGI) are defined as roughly 1 kilobase stretches of DNA that contain a high GC content and a greater proportion of CpG dinucleotides compared with the rest of the genome [38]. Genes which contain an unmethylated CGI at their TSS are generally actively transcribed and the TSS is characterized by a nucleosome-depleted region that is flanked by nucleosomes containing histone H3 lysine 4 tri-methylation (H3K4me3). This architecture allows for transcription factor (TF) binding and initiation of transcription [39] (Figure 3A). When CGIs are methylated, they are associated with long-term gene repression, such as in the case of X chromosome inactivation. An interesting phenomenon that is observed in cancer cells is the focal gain of DNA methylation at CGIs, particularly those associated with promoters of tumor suppressor genes [40–43]. In embryonic stem cells, CGI promoter silencing is often mediated through Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) deposition of histone H3 lysine 27 tri-methylation (H3K27me3). The relationship between DNA methylation and H3K27me3 is discussed below.

Figure 3: DNA methylation and histone lysine methylation crosstalk.

(A) At actively transcribed genes, H3K4me3 deposition at promoters prevents DNA methylation deposition by DNMT3A/B. Intragenic deposition of H3K36me3 by SETD2 promotes intragenic DNA methylation deposition by DNMT3B. (B) Intragenic DNA methylation regulates alternative promoter usage. Loss of H3K4me3 allows DNMT3A/B to deposit DNA methylation near the canonical transcription start site while downstream loss of DNA methylation promotes usage of intragenic promoter sites. (C) Large domains of H3K36me2 in intergenic regions promote DNA methylation deposition by DNMT3A. (D) DNA methylation and H3K9me3 work cooperatively to maintain constitutive heterochromatin. Created with Biorender.com

Genes that lack CGIs in their promoters are variably methylated at the TSS. Classic examples of this are observed during gametogenesis and embryogenesis. Genes which are responsible for maintaining the stem cell state, such as OCT4 and NANOG, are often methylated at the TSS in sperm cells but not oocytes or ESCs. Similarly, tissue-specific genes exhibit TSS methylation in ESCs, which is then removed during differentiation [39]. In this manner, DNA methylation helps to determine cell fate and tissue-specific expression of genes during embryonic development. To further explore the relationship between TSS-associated DNA methylation and gene expression, Varley et al. examined the correlation of gene expression and DNA methylation across 82 human cell lines and found that whether or not a TSS contains a CGI, methylation in that region is negatively correlated with gene expression [3]. This data is reinforced by a recent study which found that, in mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) and neurons, the major role of DNA methylation in gene repression is to directly inhibit binding of transcription factors to the TSS [44]. Together, these data reinforce the canonical view of DNA methylation as a gene silencing mechanism, particularly when it occurs in promoter regions.

Gene bodies

Gene bodies are defined as the genomic region immediately following the TSS and preceding the transcription termination site (TTS). DNA methylation within gene bodies positively correlates with active transcription of those genes [39,45]. Additionally, some gene bodies contain CGIs, denoted as intragenic CGIs. Somewhat surprisingly, intragenic CGIs are heavily methylated [46]; however, methylation of intragenic CGIs does not always positively correlate with gene expression. Varley et al. showed that when DNA methylation falls within gene bodies that do not contain a CGI, methylation positively correlates with gene expression. Conversely, if the gene contains a CGI, the observed correlation coefficients exhibit a bimodal distribution such that, in some cases, intragenic CGI methylation is positively correlated with gene expression and, in other cases, it is negatively correlated [3]. This bimodal distribution likely reflects cell and tissue-specific patterns of intragenic DNA methylation that serve as another layer of control over cell type-specific gene expression. In cancer, hypermethylation of intragenic CGIs promotes expression of functional oncogenes to promote cell growth and proliferation [47]. Thus, the hypermethylation of CGIs that is observed across cancer types is not restricted to the promoter regions of tumor suppressor genes.

Precisely how intragenic DNA methylation influences gene expression is multifaceted. To unravel the different roles of intragenic DNA methylation, it is first important to consider the architecture of the gene body itself. In addition to introns and exons, gene bodies also contain splice sites, alternative promoters, and repetitive elements. It has been shown that exons are more heavily methylated than introns, and that intragenic DNA methylation levels are most variable at intron-exon boundaries, suggesting a role for intragenic DNA methylation in alternative splicing [48]. Indeed, more recent studies have shown that loss of DNA methylation at intragenic CGIs results in increased RNA polymerase II pausing within gene bodies and promotes usage of proximal polyadenylation sites as opposed to distal sites in the methylated state [49]. Similarly, transcription of intragenic CGIs results in premature termination of host gene transcripts that may be mediated through alternative polyadenylation [50]. In addition to influencing mRNA processing, intragenic DNA methylation also has roles in dictating alternative promoter usage (Figure 3B). The presence of DNA methylation across a gene body influences whether transcription can initiate from promoters that fall within the gene coding region [46]. Furthermore, intragenic DNA methylation acts as a safeguard against cryptic transcription and the generation of unstable transcripts [51,52], likely mediated through DNMT3B, as mutations to DNMT3B that are causative for immunodeficiency with centromeric instability and facial anomalies syndrome type 1 (ICF1) disrupt transcription and RNA splicing [53].

It is interesting to consider the timing of these molecular events; a study conducted by Jeziorska et al. showed that transcription precedes DNA methylation deposition. In fact, in many cases, transcription was necessary for establishment of DNA methylation at intragenic CGIs [54]. This result supports a model in which DNMT3B deposits intragenic DNA methylation in the wake of transcribing RNA polymerase II in a manner analogous to SETD2 deposition of histone H3 lysine 36 tri-methylation (H3K36me3). Collectively, these studies illustrate the multifunctional role of intragenic DNA methylation and highlight key areas for future study. Of particular importance are RNA sequencing techniques that can capture transcripts initiated from various promoters within a single gene, such as CAGE-seq [55], DECAP-seq and CAPIP-seq [51]. DNA methylation data in conjunction with data collected from these techniques will reveal mechanisms of DNMT3B-mediated intragenic DNA methylation in alternative promoter usage.

Another function of intragenic DNA methylation is the silencing of repetitive DNA elements that fall within gene bodies, such as retroviruses and LINE1 elements. In these cases, intragenic DNA methylation is permissive for host gene transcription elongation, but simultaneously prevents transcription initiation at these intragenic repetitive elements [39]. Intriguingly, this may be a bidirectional relationship. A recent study conducted by Bogutz et al. found that transcription of lineage-specific endogenous retroviruses (ERV) led to DNA methylation deposition in gametic differentially methylated regions and that imprinting of maternally methylated genes was lost when specific ERVs were deleted [56]. In cancer, global DNA hypomethylation leads to re-expression of transposable elements that contributes to DNA mutability and genomic instability [43]. Thus, DNA methylation plays an important role in safeguarding the genome.

Regulatory regions

DNA methylation outside of promoter and transcribing regions of the genome fall within a broad category termed intergenic regions. Intergenic regions may be gene deserts, but they may also contain important regulatory elements such as enhancers. Enhancers are often defined by the presence of specific histone modifications (such as H3K27 acetylation), but some groups also define them based on their low level of DNA methylation [39]. This is an interesting idea that reflects the dynamic nature of DNA methylation at enhancer regions [57]. Whether DNA methylation at enhancers directly influences enhancer activity and/or TF binding is up for debate. On the one hand, differential methylation within enhancer regions of differentiation-specific genes is observed in different subsets of T-cells, and the presence of this DNA methylation reduces enhancer activity [58], which supports a direct mechanism for DNA methylation in regulating enhancer activity. However, a more recent study found that DNA methylation at enhancers had no effect on TF binding in 97% of cases [59]. These conflicting results highlight the complexity of enhancer function and the heterogeneity of enhancer usage within and between cell types. It is likely that enhancer function is regulated by multiple chromatin-interacting proteins, and that DNA methylation is just one piece of the puzzle.

Allosteric regulation of DNMT3 by histone lysine methylation

Research over the last two decades has connected histone post-translational modifications (PTMs) to the regulation of chromatin-templated processes, including DNA replication, DNA repair, and transcription. A canonical example is transcriptional activation mediated through histone lysine acetylation, which is proposed to function through neutralization of the positive charge of lysine residues, thus altering the basic properties of histones resulting in less compact chromatin structure [60]. However, this review focuses on histone lysine methylation, which does not directly affect chromatin structure, and instead functions as a dynamic epigenetic mark that can be written, read, and erased by various chromatin-associated proteins to help orchestrate the histone code [61]. In this manner, DNMTs act as readers of histone lysine methylation, and this function influences their genomic localization and catalytic activity. Discussed below are the roles of key sites of histone lysine methylation in the regulation of DNMT3 function. Additionally, we discuss the role of DNA methylation and histone lysine methylation crosstalk in chromatin-templated processes such as transcription.

DNMT3 and H3K4 methylation

DNMT3A, DNMT3B, and DNMT3L contain an ADD (ATRX-DNMT3-DNMT3L) domain which interacts with unmodified N-terminal tails of histone H3 (Figure 3A); mono-, di-, or trimethylation on histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me1/me2/me3) iteratively weakens this interaction and prevents DNMT3A/B catalytic activity [62–64]. This is evidenced by the dissociation constants (KD) observed between DNMT3A-ADD binding to H3K4me0 peptides (KD = 0.82 μM) and H3K4me3 peptides (KD = 35.6 μM). Moreover, when DNMT3A-ADD is not bound to an unmodified H3 tail, it interacts with its C-terminal catalytic domain which prevents DNMT3 binding to DNA and thus inhibits its methyltransferase activity [65]. Furthermore, an intact DNMT3L-ADD domain is necessary to maintain both CpG and CpH methylation [66], supporting the notion that histone lysine methylation reader activity is necessary for proper DNA methylation establishment. These interactions provide a mechanism for the observed anticorrelation between DNA methylation and promoters of actively transcribed genes that are enriched for H3K4me3 around their transcription start sites [67,68]. Indeed, mutations in the ADD domain of DNMT3A that allow for binding to H3K4me3-modified H3 tails promote acquisition of DNA methylation in these regions [69]. Interestingly, the erasure of active histone marks, including H3K4 methylation, precedes the establishment of DNA methylation at promoters [70] and enhancers [71]. In this manner, histone demethylation functions as an initial step in the establishment of repressive DNA methylation that functions downstream to regulate gene expression programs involved in cellular differentiation. Even further, the relationship between H3K4 demethylation, DNMT3A, and master transcription factors (such as Oct4), appears to be multidirectional. AlAbdi et al. showed that overexpression of Oct4 inhibits H3K4 demethylation by LSD1, preventing DNMT3A-mediated DNA methylation, and thus promoting expression of stem-state genes [72]. Together, these data highlight the mutual exclusivity of H3K4 methylation and DNA methylation, which allows for transcription factor binding to promoter and enhancer regions of actively transcribed genes. Cancer cell hijacking of the interactions between H3K4 methylation, DNA methylation, and transcription factor binding represents a pro-tumorigenic mechanism that potentially could be exploited for therapeutic purposes.

In addition to blocking de novo DNMT activity, H3K4me3 has also been shown to recruit the transcription initiation factor TFIID [60]. However, additional reports have shown that H3K4me3 is not necessary for active transcription, and instead H3K4me3 may act as a marker of active promoters in a given cell at a given time. This is evidenced by recruitment of H3K4 methyltransferase complexes by the transcription machinery [60]. A recent study found that nascent transcription can accurately predict the presence of specific histone PTMs and this data positively correlates with chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) data of histone PTM patterning [73]. Indeed, even in the absence of promoter elements or transcription machinery, H3K4me3 is recruited to CGIs, presumably to prevent the deposition of de novo DNA methylation [74]. Taken together, this evidence suggests that the distribution of H3K4me3, particularly at CGIs, influences the distribution of de novo DNA methylation throughout the genome and helps to reinforce transcriptional states in specific cell contexts.

DNMT3B and H3K36me3

DNMT3A and DNMT3B, but not DNMT3L, contain a PWWP-domain (Proline-Tryptophan-Tryptophan-Proline) that facilitates interactions with both DNA and modified histones. Specifically, the DNMT3A/B PWWP domain is a reader of histone H3 lysine 36 di- and tri-methylation (H3K36me2/me3) [75–77] (Figure 3A). The reported KD of the DNMT3A PWWP domain binding to H3K36me3 peptides is 64–68 μM [75], while the reported KD of DNMT3A PWWP binding to H3K36me2 peptides is 63 μM [77]. These observations suggest that DNMT3A binds both H3K36me2 and H3K36me3 with similar affinity. However, a more recent study found that DNMT3A binds to H3K36me2 with 2.5-fold greater affinity [78]. The increased affinity of DNMT3A for H3K36me2 provides a rationale for the observed specificity of DNMT3A activity within intergenic regions that are marked by H3K36me2 (Figure 3C). Despite these observations, the structural mechanisms that dictate DNMT3A or DNMT3B affinity for H3K36me2 and H3K36me3, respectively, are unclear.

The initial studies which reported the interaction of DNMT3A/B PWWP domain with H3K36 methylation were performed with isolated PWWP domains and H3K36me2/me3-containing peptides. While these types of studies helped to establish the histone reader function of DNMT3A/B in vitro, more in-depth genomic studies provided insight into the biological function of this interaction in DNA methylation deposition. First, Morselli et al. expressed exogenous DNMT3B in budding yeast cells (which lack endogenous DNA methylation machinery) and found that the de novo methylation activity of DNMT3B positively correlated with genomic regions containing high levels of H3K36me3 [79]. Interestingly, the overall level of DNA methylation within gene bodies was reduced in yeast backgrounds lacking Set2, an H3K36 methyltransferase [79]. This result supports the hypothesis that DNMT3B is recruited to chromatin through its association with H3K36me3. A similar experiment was performed in HCT116 colon cancer cells which lack DNMT3B and express a DNMT1 hypomorph (DKO). When DNMT3B2 was overexpressed in DKO cells, de novo DNA methylation was directed toward CGIs that are marked by H3K36me3 [80]. Intriguingly, these H3K36me3-marked CGIs are also heavily methylated in normal colon tissues, suggesting that this de novo DNA methylation activity is not important for oncogenic transformation; rather, it reflects normal DNMT3B biological function. What remains unclear from these studies is whether the association of DNMT3B with H3K36me3-marked CGIs is the result of a direct recruitment mechanism or merely reflects a genomic association of the two.

The relationship between DNMT3B and H3K36me3 has also been studied in an embryonic context. Baubec et al. performed ChIP-seq of DNMT3B1 in mESCs and found that DNMT3B co-localizes with actively transcribed gene bodies that are both occupied by RNA polymerase II and marked by H3K36me3. This co-localization is dependent on the reader activity of the PWWP domain as evidenced by reduced DNMT3B1 localization to gene bodies when the PWWP domain is mutated to prevent its interaction with H3K36me3. The authors also found that loss of H3K36me3 via Setd2 knockout resulted in a reduction of DNMT3B1 occupancy at active gene bodies [81]. To test whether DNMT3B1 localization to active gene bodies was mediated through its interaction with H3K36me3 or other components of actively transcribed gene bodies (i.e., the transcription elongation machinery), they treated cells with 5,6-dichloro-1-b-D-ribofuranosylbenzimidazole (DRB), a transcription elongation inhibitor. In the presence of DRB, DNMT3B1 was still bound to H3K36me3-marked regions of the genome. However, it is unclear whether intragenic DNA methylation was affected by DRB treatment, suggesting that the association of DNMT3B with H3K36me3 may be independent of DNA methyltransferase activity. As previously mentioned, active transcription is necessary for deposition of DNA methylation at intragenic CGIs [54], suggesting that DRB treatment could affect the activity of DNMT3B during transcription elongation despite its association with H3K36me3. The notion that H3K36me3 affects DNMT3B localization, but not its catalytic activity is further supported by a study by Hahn et al. in which loss of H3K36me3, via SETD2 knockdown in HBEC and HCT116 cells, had no effect on levels of intragenic DNA methylation [82]. Additionally, Tiedemann et al. reported that knockout of SETD2 in a clear cell renal carcinoma cell line predominately resulted in genome-wide DNA hypermethylation, with significant gains at bivalent enhancers in intergenic regions [83]. Furthermore, highly expressed genes which lost H3K36me3, retained DNA methylation levels. These patterns were recapitulated in primary tumor samples from cancers driven by inactivating SETD2 mutations [83]. These findings argue against a role for SETD2-deposited H3K36me3 in positively regulating DNMT3B activity within gene bodies. Altogether, these data support a mechanism in which H3K36me3 is associated with DNMT3B localization within gene bodies but is not required for continued maintenance of DNA methylation in these regions.

H3K36me3 is inherently linked to transcription through SETD2 co-transcriptional catalytic activity [84]. Nevertheless, H3K36me3 is not directly required for active transcription. It does, however, prevent aberrant transcription initiation within gene bodies through the recruitment of histone deacetylase complexes [85]. H3K36me3 has also been shown to regulate alternative splicing [86], but it is unclear whether these functions are independent of intragenic DNA methylation, which has roles in preventing cryptic transcription and regulating alternative splicing, as discussed previously. One potential connection between H3K36me3 and DNA methylation during these co-transcriptional processes is the human polymerase-associated factor 1 complex (hPAF1C). A temporal study of human embryonic stem cell differentiation found that DNMT3B directly interacts with several hPAF1C components at the start of differentiation [87]. Given the known function of DNMT3B at actively transcribed gene bodies, this interaction likely helps facilitate co-transcriptional deposition of intragenic DNA methylation. As discussed previously, it is possible that as SETD2 deposits H3K36me3, DNMT3B also deposits DNA methylation to help silence transcription in the wake of transcribing RNA polymerase II. In this manner, H3K36me3 and intragenic DNA methylation may also serve as epigenetic markers of active transcription in specific cell types during development and differentiation. To support this idea, studies in yeast have shown that components of the Paf1 complex are necessary for deposition of H3K36me2/me3 [88,89]. Furthermore, deletion of Paf1 components led to aberrant expression of imprinted genes, implying a role for Paf1/DNMT3B-mediated genic methylation [89]. Together, these data support a cooperative model between DNMT3B, H3K36 methylation, and the PAF1 complex in the regulation of intragenic DNA methylation during transcription. This model provides an alternative hypothesis for the observed association of DNMT3B and H3K36me3 at actively transcribed gene bodies and suggests that there is still more to be discovered surrounding the mechanisms of DNMT3B-mediated genic DNA methylation.

A more recent study conducted by Xu et al. probed the function of SETD2-mediated H3K36me3 in establishing the maternal DNA methylome which influences downstream gene expression as well as genomic imprinting. The authors found that Setd2 knockout in oocytes resulted in a loss of genic DNA methylation and concomitant gains of intergenic DNA methylation which altered the transcriptome and prevented proper oocyte maturation, eventually leading to embryonic lethality [90]. This study emphasizes the importance of de novo DNMT activity during embryonic development and further delineates the context-dependent functionality of H3K36 methylation in the regulation of DNMT3B activity when comparing SETD2 knockout in somatic cancer cells versus mature oocytes.

DNMT3A and H3K36me2

Despite their similar DNA sequence and protein domain structure, DNMT3A and DNMT3B have distinct chromatin binding profiles. While both enzymes have in vitro reader activity for H3K36me2/me3, recent studies have begun to elucidate the divergence in DNMT3A and DNMT3B localization and catalytic function. DNMT3B is primarily associated with H3K36me3 in the bodies of actively transcribed genes [81], whereas DNMT3A is associated with H3K36me2 in intergenic regions [78,91] (Figure 3C). DNMT3A localization within large domains of intergenic H3K36me2 positively correlates with de novo DNA methylation deposition by DNMT3A, and when H3K36me2 is depleted via nuclear receptor binding SET domain protein 1 (NSD1) knockout, DNMT3A shifts its localization to H3K36me3 domains [78]. The specific functional relationship between DNMT3A and H3K36me2 is further exhibited in a study conducted by Shirane et al. in which germline deletion of NSD1 in male mice resulted in DNA hypomethylation of intergenic regions and severe defects in spermatogenesis as well as paternal imprinting [92]. Indeed, an earlier study conducted by Kaneda et al. found that germline-specific deletion of Dnmt3a in male mice also impaired spermatogenesis and prevented DNA methylation of some paternally imprinted loci [93]. Together, these results emphasize the direct role of H3K36me2 in regulating DNMT3A activity in male gametes. The results from these studies, compared with the results from the study conducted by Xu et al. [90], shed light on a potential mechanism for the observed sexual dimorphism of DNA methylation in male and female gametes. It is evident that H3K36me3 specifically instructs de novo DNA methylation by DNMT3B in female gametes, whereas H3K36me2 instructs de novo DNA methylation by DNMT3A in male gametes. However, the study conducted by Kaneda et al. also found that DNA methylation of maternally imprinted loci was perturbed in the absence of DNMT3A. Further, they report that germline-specific deletion of Dnmt3b had no effect on DNA methylation of imprinted loci [93] These conflicting results indicate that more research is needed to parse out the specific functions of DNMT3A and DNMT3B in the establishment of DNA methylation at imprinted loci and specifically how H3K36me2/me3 are involved in their genomic localization and regulation of their catalytic activity in different cellular contexts. Ultimately, these findings have implications for understanding the pathogenesis of developmental disorders caused by mutations in either DNMT3A or DNMT3B.

Mice carrying a DNMT3A-PWWP mutation (D329A) exhibit growth defects and DNA hypermethylation at CpG island promoters as well as regions marked by H3K27me3 and H3K4me3, known as bivalent chromatin [94]. These results suggest that the DNMT3A PWWP domain may restrict DNA methylation deposition in regions of the genome marked by H3K27me3, though further study is warranted. The delayed growth and DNA hypermethylation observed in the DNMT3A-D329A mouse model mirror the effects seen in Heyn-Sproul-Jackson syndrome (HESJAS, discussed in more detail below) patients with DNMT3A PWWP mutations [95], making this a promising model for studying the pathogenesis of HESJAS. Similarly, a de novo DNMT3A PWWP mutation was found in a subset of patients with paragangliomas and tumor tissue exhibited DNA hypermethylation [96]. From this study, it is unclear how loss of DNMT3A H3K36 methylation reader activity leads to DNA hypermethylation, as one would expect to see DNA hypomethylation, particularly at genomic regions marked by H3K36me2. Interestingly, a similar molecular phenotype was recently observed with DNMT3B PWWP mutation. Expression of DNMT3B PWWP mutants in DKO cells resulted in DNA hypermethylation at heterochromatic regions marked by histone H3 lysine 9 tri-methylation (H3K9me3) [97]. Moreover, the recruitment of DNMT3B to these H3K9me3-marked regions appears to be mediated through the N-terminus of DNMT3B, indicating a PWWP-independent targeting mechanism for DNMT3B. Together, these studies suggest DNMT3A/B mediate DNA methylation deposition in heterochromatic regions of the genome via an unknown mechanism, promoting the need for more research in this area.

A recent study has begun to shed light on this intriguing observation that DNMT3A PWWP mutation results in DNA hypermethylation at Polycomb-marked regions of the genome. Weinberg et al. overexpressed wildtype and PWWP mutant forms of DNMT3A in mESCs and observed their genomic co-localization with various histone modifications. They found that mutant DNMT3A, but not wildtype, exhibited strong co-localization with histone H2A lysine 119 ubiquitination (H2AK119ub) deposited by the RING1A/B subunits of Polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1). This co-localization is surprisingly mediated through DNMT3A1 reader activity of H2AK119-ubiquitinated nucleosomes, a function that is presumably stimulated in the absence of the PWWP domain [98]. Furthermore, the H2AK119ub reader activity of DNMT3A is specific to DNMT3A1, as DNMT3A2 and DNMT3B did not bind to H2AK119-ubiquitinated nucleosomes in vitro, nor did they co-localize with this mark in the genome when overexpressed in mESCs. This is not surprising given that DNMT3A2 lacks the N-terminal region observed in DNMT3A1, which the authors refer to as the “ubiquitin-dependent recruitment” domain (Figure 2). The authors further concluded that DNMT3A PWWP mutations tip the balance of normal DNMT3A recruitment to regions marked by H3K36 methylation and contribute to the aberrant hypermethylation seen in HESJAS and paragangliomas.

DNMT3A1 reader function for H2AK119ub is also observed in vivo. Gu et al. generated DNMT3A1 and DNMT3A2 knockout mice and found that DNMT3A1 knockout, but not DNMT3A2 knockout, affected postnatal growth and survival [99]. Furthermore, the authors showed that this phenotype is mediated through the DNMT3A1 N-terminus (which is absent in the DNMT3A2 isoform). These data further support the importance of the N-terminus of DNMT3A1 and its associated H2AK119ub reader activity. Molecularly, DNMT3A1 knockout and DNMT3A1 N-terminal deletion mutants exhibit defects in CpH methylation, but CpG methylation is unaffected. Importantly, DNMT3A2 knockout had no effect on CpH nor CpG methylation. These results support a key role of DNMT3A1 specifically in depositing CpH methylation in the developing brain. Additionally, DNMT3A1 binding to the flanking regions of bivalent promoters is lost when the N-terminus is deleted, suggesting a role for H2AK119ub reader function in recruiting DNMT3A1 to these regions of the genome.

Conversely, DNMT3A1 deposition of CpH methylation was recently found to be directed by NSD1 deposition of H3K36me2 and this functional relationship has implications in the pathogenesis of neurodevelopmental disorders caused by either DNMT3A or NSD1 mutation [100]. More specifically, broad domains of NSD1-deposited H3K36me2 are shaped by genome topology, which in turn recruits DNMT3A to catalyze CpA methylation that is then read out by methyl binding proteins to regulate transcription of neuronal genes. Interestingly, the authors showed that active gene transcription within these broad H3K36me2 domains converts H3K36me2 to H3K36me3 via co-transcriptional SETD2 function, a well-studied role of SETD2 [84,101–104]. The conversion of H3K36me2 to H3K36me3 reduces DNMT3A binding to these regions and subsequent deposition of CpA methylation. Disruptions to this signaling pathway at various points have similar phenotypic outcomes as observed through related neurodevelopmental disorders such as Tatton-Brown-Rahman syndrome and Sotos syndrome (discussed further below).

DNMT3 and H3K9 methylation

Generally speaking, DNA methylation and H3K9 methylation work in concert to establish and maintain constitutive heterochromatin (Figure 3D). Additionally, both marks are associated with silencing of retrotransposons. This notion is evidenced by the positive correlation of DNA methylation and H3K9 methylation throughout the genome [67]. H3K9 methylation is catalyzed by several different enzymes, including SUV39H1/2, G9a/GLP, and SETDB1. SUV39H1/2 were shown to be important for DNMT3B targeting to pericentric heterochromatin; double knockout of these two enzymes resulted in loss of DNA methylation in these regions [105]. The association between DNMT3B and H3K9 methylation at pericentric heterochromatin is likely perturbed in patients with ICF1, given the DNA hypomethylation observed in these genomic regions when DNMT3B is mutated. DNMT3A also interacts with SUV39H1, likely through its ADD domain [106]. Similarly, DNMT3A was reported to interact with SETDB1, also through its ADD domain [107]. However, there is additional evidence to indicate that the PWWP domain of both DNMT3A and DNMT3B is necessary for their localization to pericentric heterochromatin as well as deposition of DNA methylation in these regions [108]. Together, these results highlight an understudied relationship between DNMT3A/B and the H3K9 methyltransferase complexes. In mESCs, G9a is necessary for de novo methylation of imprinted genes [109] and germline-specific genes [110], though it is unclear whether a direct interaction between G9a and DNMT3A/B is necessary. Interestingly, G9a-dependent de novo DNA methylation is not dependent on G9a catalytic activity, and instead may involve its ankyrin repeat domains [111]. An alternative hypothesis for G9a recruitment of DNMT3A/B involves an indirect interaction with the H3K9 methylation machinery through MPP8, a member of the HUSH complex [112]. Collectively, these studies highlight the cooperative function of de novo DNA methylation and H3K9 methylation in the regulation of gene silencing and heterochromatin formation during embryonic development.

DNMTs and H3K27 methylation

The relationship between DNA methylation and H3K27 methylation is complex and the precise interactions between these two repressive marks are still being elucidated. While there is limited biochemical evidence to directly connect the DNMT3 enzymes to H3K27 methylation, a few studies suggest an indirect relationship. Specifically, EZH2, the catalytic subunit of PRC2, was shown to interact with DNMT1, DNMT3A and DNMT3B [113]. Additionally, DNMT3L competes with DNMT3A/B for interaction with PRC2, which could function to prevent de novo methylation of Polycomb target regions [114]. However, a later study found that DNMT3L functions solely as a positive regulator of DNA methylation by stabilizing DNMT3A2 protein levels [115]. The authors of this subsequent study speculate that the discrepancies in the data may be explained by partial differentiation of the mESC lines used. Upon differentiation, some bivalent promoters gain DNA methylation to maintain gene silencing in the differentiated state. On the genomic scale, DNA methylation and H3K27 methylation are anticorrelated [2,67,116], especially within CGIs [117]. This apparent antagonistic relationship could be explained by DNA methylation blocking PRC2 activity. This is illustrated by in vitro experiments which show that PRC2 binding to H3K27me3-marked nucleosomes is inhibited by the presence of CpG methylation [91,118], suggesting that CpG methylation prevents the spreading of H3K27me3 domains. In cells, DNA demethylation via DNMT triple knockout results in a broad redistribution of H3K27me3 away from normal PRC2 target regions and into regions of the genome that are heavily DNA methylated in normal cells [117,119]. Additionally, expression of wildtype, but not catalytic dead, DNMT3 proteins into mESCs lacking DNA methylation recapitulated H3K27me3 patterning that is observed in normal cells [120]. A possible mechanism for these observations could be related to PRC2 recruitment by the Polycomb-like proteins, which specifically bind to unmodified CpG dinucleotides [121]. What remains unclear is whether the aberrant gain of H3K27 methylation following DNA hypomethylation is a stochastic event related to disrupted PRC2 targeting, or whether it is a coordinated response by the cell to compensate for loss of gene silencing. A study conducted by Walter et al. found that following widespread DNA demethylation, H3K27me3 accumulates at transposons to maintain silencing in the absence of DNA methylation [122], suggesting a controlled cellular response to maintain genome integrity. Interestingly, this “epigenetic switch” can occur in either direction [123]. A frequently observed phenomenon in cancer cells is the gain of DNA methylation at CGIs that were previously marked by H3K27me3 [124,125]. One hypothesis for this aberrant gain of CGI DNA methylation is that continued silencing of cell type-specific genes allows cancer cells to remain in a stem-like state that promotes continued cell proliferation, growth, and survival. Despite the wide array of literature describing the mutual exclusivity of DNA methylation and H3K27 methylation, there are some instances where these marks can co-occur, particularly at areas of the genome with relatively low CpG density in differentiated cells [126]. In summary, the relationship between DNA methylation and H3K27 methylation is highly complex and likely reflects patterns of early development.

DNA methylation and histone lysine methylation in human disease

The epigenetic writers of DNA methylation and histone lysine methylation are often mutated in neurodevelopmental disorders as well as several cancer types. In some cases, histone genes themselves are mutated and these abnormalities have been causally linked to disease. The prevalence of these epigenetic mutations in human disease highlights the important functions of histone modifications and DNA methylation in regulating proper genomic function in terms of both global chromatin organization and gene expression.

DNMTs regulate neuronal development

In mice, homozygous deletion of DNMT1 is embryonic lethal [35]. In humans, heterozygous point mutations to DNMT1 causes hereditary sensory neuropathy type 1E (HSN1E) [127,128]. Functional studies of these mutants suggest misfolding of DNMT1 protein leading to haplo-insufficiency of the DNMT1 gene, reduced methyltransferase activity and global DNA hypomethylation. Additionally, heterozygous point mutations to DNMT1 have been identified that cause cerebellar ataxia, deafness, and narcolepsy (ADCADN) [129]. Both of these mendelian disorders are inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. Molecular studies of the functional consequence of these heterozygous point mutations suggest DNMT1 secondary structure is affected, resulting in reduced protein stability and methyltransferase activity [130]. The identification of causative DNMT1 mutants in these disorders highlights the importance of DNMT1 function in neurodevelopment.

De novo mutations in DNMT3A cause Tatton-Brown-Rahman Syndrome (TBRS) [131], an overgrowth syndrome characterized by tall stature, a distinctive facial appearance, and intellectual disability. Initially, 13 different de novo mutations were identified, ten nonsynonymous mutations, two frameshifts, and one in-frame deletion. These mutations are dispersed throughout the functional domains of DNMT3A and influence the methyltransferase activity or the histone reader activity mediated through the ADD or PWWP domains. The major molecular consequence of these DNMT3A mutations is global reduction in CpH methylation in the brain, leading to epigenomic and transcriptomic changes that contribute to disease pathogenesis [132]. Additional DNMT3A mutations were found in four more TBRS patients at arg882 [133–135], a somatic mutational hotspot for acute myelogenous leukemia (AML, discussed further below). One of these patients would later develop T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma. It is interesting that germline DNMT3A R882 mutation led this patient to develop a different hematological malignancy as compared to somatic DNMT3A R882 mutations in AML. However, additional TBRS patients have developed AML [136], indicating that germline mutation to DNMT3A predisposes individuals to developing hematological malignancies.

More recently, de novo heterozygous missense mutations in DNMT3A were identified in patients with Heyn-Sproul-Jackson syndrome (HESJAS) [95] (Figure 4A). In contrast to TBRS, HESJAS is characterized by microcephalic dwarfism and global developmental delay. These identified DNMT3A mutations fall within the PWWP domain and block DNMT3A binding to H3K36me2 and H3K36me3. The loss of H3K36 methyl-reader activity paradoxically resulted in DNA hypermethylation, particularly at CGIs associated with Polycomb repressive complexes. This result suggests dysregulation of developmental genes by a gain-of-function DNMT3A mutant. The pathogenic molecular mechanisms leading to HESJAS likely involve mis-targeting of DNMT3A and subsequent alterations to CpH methylation patterns resulting from DNMT3A altered N-terminal reader activity of H3K36 methylation and H2AK119 ubiquitination, as discussed earlier [94,98–100].

Figure 4: Imbalance of DNA methylation and histone lysine methylation drives molecular pathogenesis in human developmental disorders.

(A) Loss of H3K4 KMT function or loss of H3K27 lysine demethylase function leads to an imbalance of bivalent chromatin and site-specific alterations to DNA methylation. Loss of DNMT3A or DNMT3B methyltransferase and/or histone reader function also gives rise to DNA methylation defects. These molecular outcomes are characteristic of a group of distinct, but related developmental disorders that exhibit delayed growth and impaired mental development. (B) Levels of H3K27 and H3K36 methylation are antagonistic to one another. In wildtype cells these two PTMs are at equilibrium to ensure proper genome regulation. Loss of KMT function leads to an imbalance of methylation on H3K27 and H3K36 as well as alterations to DNA methylation. The dotted arrows represent the flux between levels of H3K27 and H3K36 methylation when their respective KMTs are mutated. Loss of DNMT3A function also leads to DNA methylation defects. Collectively, these molecular consequences give rise to a spectrum of developmental disorders referred to as overgrowth and intellectual disability syndromes. Syndrome names are color-coded according to their associated KMT or DNMT driver mutations. Created with Biorender.com

Homozygous mutations in DNMT3B are causative for immunodeficiency with centromeric instability and facial anomalies (ICF) syndrome type 1 [36,137]. ICF syndrome is characterized by immune deficiency owing to decreased numbers of mature B cells and low serum immunoglobulins, facial dysmorphism, and delayed mental and physical development. ICF is family of related disorders that fall into different subtypes based on the identified causative mutations. DNMT3B mutations cause ICF type 1. ZBTB24, CDCA7, and HELLS are mutated in subtypes 2, 3, and 4, respectively [138]. Each of these genes has been implicated in the DNMT1-dependent DNA methylation maintenance pathway, suggesting that it is DNA methylation defects which lead to the observed ICF phenotypes. Further, this connection highlights roles for DNMT3B in DNA methylation maintenance. Indeed, at the molecular level, ICF1 is characterized by DNA hypomethylation of satellite 2 and 3 repeats, which are major components of constitutive heterochromatin, on chromosomes 1, 9 and 16. This observed hypomethylation leads to chromosomal instability and shortening of telomeres. Additionally, karyotypes of ICF1 patients show chromosomal rearrangements and terminal deletions. Interestingly, while satellite hypomethylation can be observed in all cell types of ICF patients, chromosomal rearrangements are only observed in lymphocytes, highlighting the important function of DNMT3B in this cell type. DNMT3B mutations observed in ICF1 primarily cluster in the catalytic domain, though some are found in the N-terminal regulatory region [138]. Baubec et al. showed that an ICF-related mutation in the DNMT3B PWWP domain prevents DNMT3B binding to H3K36me3 [81], suggesting that DNA methylation defects may be mediated through altered DNMT3B chromatin interactions (Figure 4A). Further molecular characterization of DNMT3B mutations seen in ICF patients showed a reduction in genic DNA methylation and alterations to mRNA splicing [53], mediated through H3K4 methylation. These results reinforce the known function of DNMT3-mediated DNA methylation in preventing deposition of H3K4 methylation to regulate alternative promoter usage. Further study is needed to connect these molecular observations to the clinical presentation and treatment of ICF patients.

Imbalance of histone lysine methylation drives developmental disorders

Dysregulation of H3K4 and H3K27 methylation

De novo heterozygous mutations in KMT2A (MLL) are found in patients with Wiedemann-Steiner syndrome (WDSTS) [139,140]. Mutations result in premature termination of the transcript and subsequent nonsense-mediated decay leading to haploinsufficiency of the KMT2A protein. Clinically, patients present with short stature, distinctive facial appearance, mild to moderate intellectual disability and behavioral difficulties. Functional studies of KMT2A haploinsufficiency have not been performed, though it is presumed that H3K4 methylation would be reduced in the genome, leading to changes in chromatin architecture and gene expression.

Nonsense or frameshift mutations in the KMT2D (MLL2) gene are implicated in Kabuki syndrome [141–144]. Kabuki syndrome is characterized by intellectual disability, postnatal dwarfism, facial dysmorphism and abnormalities of the vertebrae, hands, and hip joints. KMT2D mutations lead to truncated transcripts and subsequent mRNA degradation resulting in haploinsufficiency of the KMT2D protein [145]. Loss of KMT2D protein was shown to reduce methylation on H3K4 to varying degrees depending on the mutation [146]. Reduction in H3K4 methylation alters the epigenomic and transcriptomic landscape that gives rise to the developmental delay and characteristic phenotypes of Kabuki syndrome. Interestingly, mutations in KDM6A (an H3K27 lysine demethylase) were also found in patients with Kabuki syndrome [147,148]. The identification of KDM6A mutation in Kabuki syndrome patients suggests that perturbing the balance of bivalent chromatin leads to pathogenic changes in genome architecture (Figure 4A). Indeed, these effects may be mediated through altered binding of additional chromatin-interacting proteins such as the DNMTs, as evidenced by site-specific alterations to DNA methylation in Kabuki patients with confirmed KMT2D mutation [149]. The study of the molecular characteristics of Kabuki syndrome patients reveals the complex interplay between DNA methylation, H3K4 methylation, and H3K27 methylation in the regulation of chromatin accessibility and gene expression.

Heterozygous de novo mutations in EZH2 have been identified in patients with Weaver syndrome [150]. Weaver syndrome is characterized by pre- and postnatal overgrowth and developmental delay. Phenotypically, Weaver syndrome is very similar to Sotos syndrome, which is caused by mutations in the NSD1 gene (discussed below). More recent genetic and molecular analyses help to distinguish Weaver syndrome patients from Sotos syndrome patients. Additionally, Cohen-Gibson and Imagawa-Matsumoto syndromes are phenotypically similar to Weaver syndrome and they are caused by heterozygous mutations in the EED [151,152] and SUZ12 [153] genes, respectively. EZH2, SUZ12 and EED are core members of PRC2, indicating that it is dysregulated PRC2 activity which causes these related developmental syndromes. Indeed, Weaver-associated mutations in PRC2 complex members lead to reduced levels of H3K27me3 in patient samples [153]. Furthermore, samples from Weaver syndrome patients have a distinct DNA methylation profile that is recapitulated in patient samples which harbor loss-of-function mutations in other core PRC2 complex members [154]. The overlapping molecular phenotypes observed in Weaver syndrome and Weaver-associated syndromes emphasizes the mechanistic links between H3K27 methylation and DNA methylation.

Dysregulation of H3K36 methylation

Haploinsufficiency of NSD1, either through mutation, microdeletions or translocation events, causes Sotos syndrome [155]. Like Weaver syndrome, Sotos syndrome is characterized by prenatal and childhood overgrowth, impaired intellectual development, and occasional seizures. Molecularly, the loss of NSD1 protein function leads to reduced H3K36me2 and patient samples exhibit DNA hypomethylation [156]. The related phenotypes between Weaver syndrome and Sotos syndrome may be explained by the antagonistic relationship between H3K27 methylation and H3K36 methylation [157]. When large domains of H3K36me2 are lost as a result of NSD1 mutation, H3K27me2/3 domains begin to spread into regions that are normally marked by H3K36 methylation and vice versa when H3K27me2/3 is lost, essentially eroding the boundaries between the domains of these histone lysine methylation marks. The subsequent changes to genome architecture likely mediate similar gene expression changes during prenatal development and early childhood to give rise to the characteristic overgrowth and intellectual disability phenotypes seen in Weaver and Sotos syndromes (Figure 4B).

In addition to NSD1 mutations, heterozygous mutations in SETD2 have been identified in a subset of patients with neurodevelopmental and overgrowth syndromes, which are termed Sotos-like syndrome (also referred to as Luscan-Lumish syndrome) owing to the phenotypic overlap with Sotos syndrome [158] (Figure 4B). Sotos-like syndrome is characterized by postnatal overgrowth, macrocephaly, obesity, speech delay, and advanced carpal ossification [159]. While functional molecular studies have yet to be conducted, it is assumed that the identified truncating and missense mutations would result in loss of SETD2 function and a subsequent reduction in H3K36me3. It is interesting to note that SETD2 is the only known enzyme capable of catalyzing H3K36me3, yet the phenotypic consequences of its mutation resemble that of NSD1 mutations, an H3K36 mono- and di-methyltransferase. Further molecular analysis of Sotos and Sotos-like patient samples is needed in order to elucidate the distinctions between these two syndromes on the molecular level. Of particular interest is the distribution of DNA methylation in these samples, as well as the transcriptomic changes compared to healthy matched controls. These data could shed light on SETD2 functions independent of its catalytic activity.

In contrast to NSD1 mutations, de novo heterozygous mutations to NSD2 are causative for Rauch-Steindl Syndrome (RAUST) [160–164], which is characterized by impaired pre- and postnatal growth, including short stature and microcephaly. Furthermore, RAUST patients exhibit developmental delay and mild intellectual disability. Missense, nonsense, and frame shift mutations have all been identified in the NSD2 gene of RAUST patients and all are predicted to result in loss of NSD2 function. NSD2 loss-of-function is predicted to deplete H3K36me2 levels, however in vitro characterization of some of these identified patient mutations showed no effect on global levels of H3K36me2 [164]. This result suggests that some of the observed phenotypes in RAUST may be mediated through molecular mechanisms that are independent of NSD2 catalytic function. This notion is further supported by the observation that germline NSD1 or NSD2 loss-of-function mutations result in opposing phenotypic outcomes, indicating that the consequences of loss of H3K36me2 are not equivalent in these two developmental syndromes. Further research is needed to parse out the distinct functions of NSD1/2 in development as well as the contribution of H3K36me2 to these functions.

Even more puzzling is the identification of de novo SETD2 mutations in Rabin-Pappas syndrome (RAPAS) and intellectual development disorder 70 [165]. Unlike Sotos and Sotos-like syndromes, RAPAS and intellectual development disorder 70 are characterized by impaired global development, microcephaly, and dysmorphic facial features. The identified mutations affect the same codon in the SETD2 coding sequence but result in a different amino acid substitution. This distinction suggests a SETD2 gain-of-function mechanism in these individuals. Indeed, the mutations occur within the putative autoinhibitory domain of SETD2 based on conserved structure between yeast Set2 and human SETD2 [166], though its function has yet to be clearly defined. These results further suggest that the developmental phenotypes may be mediated through loss of SETD2 functions that are independent of its role in H3K36 methylation.

Altered chromatin regulation via histone gene mutation

In addition to mutations that occur in the genes encoding histone lysine methyltransferases, mutations to histone genes themselves have also been identified in neurodevelopment disorders and cancers. Notably, de novo heterozygous mutations in HIST1H1E were found in five pediatric patients with an unidentified overgrowth and intellectual disability disorder (OGID) [167]. HIST1H1E encodes histone H1.4 and these identified mutations were found to produce truncated protein products with a reduced net charge. Histone H1 is a linker histone that contributes to higher-order chromatin structure by neutralizing negatively charged linker DNA between nucleosomes. Mutant H1.4 is likely deficient in this function and the resulting alterations to chromatin structure mediate gene expression changes that lead to the observed overgrowth phenotype. The distinct molecular profiles and phenotypic outcomes that arise from alterations to the DNA methylation or histone lysine methylation machinery have led to the broad classification of OGID syndromes. The similarities among OGID syndromes highlights the importance of striking a balance between key histone modifications and DNA methylation for proper epigenetic regulation of chromatin architecture and gene expression (Figure 4B). However, more research is needed to discern the functions of DNMTs and KMTs in development disorders that present with similar molecular profiles but opposing phenotypic effects. By characterizing the molecular differences among these opposing syndromes, we will gain a better understanding of the foundational mechanisms underlying the epigenetic crosstalk between specific sites of histone lysine methylation and DNA methylation.

Alterations to DNA methylation and histone lysine methylation in cancer

As mentioned above, somatic DNMT3A mutations occur in 20% of AML patients, and are associated with poorer clinical outcomes and reduced overall survival [168–170]. The incidence of DNMT3A mutation in AML was later confirmed by a larger study conducted by The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Research Network [171]. R882 is a genetic hotspot for DNMT3A mutations in AML. These mutant forms of DNMT3A exhibit reduced enzymatic activity as well as increased affinity for histone H3 in vitro [169]. Structural characterization of the R882H mutation found that the target recognition domain is compromised, resulting in reduced enzymatic activity as well as loss of CpG specificity and flanking sequence preference [172]. These changes to DNMT3A activity and localization result in downstream gene expression changes that may drive oncogenic formation in hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) (Figure 5). Indeed, DNMT3A mutation is an early event in adult AML evolution and mutant DNMT3A HSC clones may contribute to chemotherapy resistance [173]. This notion is further supported by the identification of DNMT3A mutations in myelodysplastic syndrome [174] (MDS), which is often considered a precursor condition to AML. In fact, 58% of MDS patients with DNMT3A mutation progressed to AML, compared to 28% without DNMT3A mutation. Collectively, these studies highlight the role of mutant DNMT3A and its associated epigenetic alterations in the pathogenesis of MDS and AML.

Figure 5: Alterations to DNA methylation and histone lysine methylation in cancer formation.

Context-specific alterations to DNA methylation and imbalances of histone lysine methylation collectively contribute to carcinogenesis and leukemogenesis. Specifically, mutations that disrupt DNMT3A catalytic activity and/or histone lysine methylation reader function lead to DNA hypo- and hypermethylation, depending on the cancer type. Similarly, mutations which disrupt PRC2 catalytic activity or chromosomal rearrangements involving KMT2A lead to an imbalance of bivalent chromatin which may lead to pathogenic gene expression programs that promote a stem-like cellular state. Mutations across the SETD2 coding region prevent its function in key cellular processes such as DNA repair, ultimately leading to increased mutability and genomic instability. Additional mutations to PRC2 or NSD1/2 disrupt the balance between H3K27 and H3K36 methylation and promote oncogenic gene expression programs. Created with Biorender.com

An emerging association between DNMT3A germline mutation and human disease is seen through genetic analysis of pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas. Whole exome sequencing of affected patients and their parents identified de novo missense mutations in the PWWP domain resulting in loss of H3K36 methylation reader activity [96]. Molecularly, tumors had DNA hypermethylation at developmental genes compared to tumors without DNMT3A mutation. Further studies are warranted to determine how the epigenetic changes induced by germline DNMT3A mutation contribute to oncogenesis in these tumor types.

Somatic mutations in KMT2D were identified in 10% of pediatric medulloblastomas [175], 32% of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, and 89% of follicular lymphomas [176]. Additionally, KMT2A rearrangements are common in acute lymphoblastic leukemia and acute myeloid leukemia. KMT2A rearrangements have been identified with more than 80 distinct genes, though most frequently with AF4, AF9, ELL, and ENL. The incidence of KMT2A rearrangement in leukemia is significantly higher in infant and pediatric patients, and in these cases, as well as adult cases, KMT2A rearrangement is associated with much poorer clinical outcomes and dismal prognosis [177]. The higher incidence in infant and pediatric patients suggests KMT2A rearrangement occurs early in postnatal development. KMT2A-rearranged leukemias exhibit global DNA hypomethylation [178,179] as well as dysregulation of bivalent chromatin that promotes a gene expression profile characteristic of a stem-like state [180] (Figure 5). Mechanistically, this dysregulation may be mediated through KMT2A CXXC domain recognition of unmethylated CpGs and occlusion of repressive H3K9me3 that allows for active expression of stem-state genes, such as the HOX family of genes [181,182]. These examples underscore the importance of H3K4 methylation and DNA methylation crosstalk in the regulation of gene expression and cellular identity.

Somatic mutations in EZH2 have been identified in individuals with myelodysplastic syndromes [183], myeloproliferative neoplasms [184], follicular lymphoma, and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [185]. The increasing identification of EZH2 mutations in myeloid malignancies points to an important function for PRC2 activity and H3K27me3 deposition in hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Furthermore, SUZ12 and EED microdeletions have been identified in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST) [186,187] in which loss of PRC2 function activates the oncogenic Ras signaling pathway [188,189]. It is interesting to note that EZH2 mutations seen in hematological malignancies result in a gain-of-function mechanism, whereas in MPNSTs, it is loss of PRC2 function that drives oncogenic transformation. PRC2 loss-of-function is observed in additional solid tumor types, including diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas (DIPG) and non-brainstem glioblastomas. Point mutations that convert the commonly modified histone H3 lysine 27 to methionine (K27M) occur either in HIST1H3B, which encodes the canonical histone H3.1, or H3F3A, which encodes the variant histone H3.3 [190,191]. Point mutations to histone H3 glycine 34 that result in valine or arginine substitutions were also identified in a subset of these pediatric gliomas. The opposing mechanisms of PRC2-associated mutations in liquid versus solid tumors highlight the delicate balance of H3K27 methylation needed for proper regulation of chromatin architecture and gene expression.

Furthermore, histone H3 lysine 36 to methionine (K36M) and glycine 34 to tryptophan or leucine mutations in H3F3A/B were identified in chondroblastoma and giant cell tumors of bone, respectively. Collectively, these histone gene mutations and their protein products are referred to as “oncohistones.” These mutations are highly specific to tumor type and are found in tumors with relatively low mutational burden. This suggests that oncohistone mutations are drivers or co-drivers in tumor development and progression. This notion has been further supported in animal models wherein very few additional mutations are needed to drive tumor formation [192] and the presence of an oncohistone mutation accelerates tumor progression [193]. Somatic histone mutations, both in the N-terminal tail and the globular domains, occur in roughly 4% of human cancers, and are often found in and around key modifiable residues [194]. The prevalence of histone gene mutations in human cancers further emphasizes the importance of histone PTMs in the regulation of chromatin-templated processes that control cellular function and identity.

Following their initial identification, oncohistone mutants were shown to decrease global levels of their respective histone lysine methylation sites [195,196]. While the mechanisms underlying this global reduction are still being elucidated, recent data suggests that nucleosomes containing the mutant histone H3 protein function as a competitive inhibitor for histone lysine methyltransferases (KMT) [197]. A competitive inhibition mechanism could explain the dominant negative effects of the H3.1/3 K27M mutation, as the mutant makes up only 3–17% of the total H3 in tumor samples [195]. Additionally, titration experiments with H3 peptides containing the H3K36M mutation showed that increasing amounts of mutant peptide led to a decrease in H3K36 KMT activity [198]. Further support for this notion can be seen in posterior fossa type A ependymomas which overexpress EZHIP, a protein whose sequence mimics H3K27M mutation. Overexpression of EZHIP in HEK293T cells resulted in global reduction of H3K27me2/me3, similar to the levels seen in H3K27M expressing cells. These data are in line with a competitive inhibition model of the K-to-M mutations on their respective KMTs. Another way in which histone K-to-M mutations function to globally reduce specific sites of histone lysine methylation is by preventing the positive feedback mechanisms that promote spreading of domains of histone lysine methylation [199,200]. The molecular and pathogenic consequences of widespread loss of histone lysine methylation in these tumor types are still being elucidated, but they likely contribute to a wide array of chromatin organization abnormalities that facilitate downstream oncogenic transformation (Figure 5). Indeed, histone H3K27M mutations were shown to deplete not only H3K27 methylation, but also DNA methylation [201]. The concerted loss of H3K27me3 and DNA methylation led to pervasive gains in H3K27 acetylation and activation of an oncogenic transcriptional profile in pediatric high-grade gliomas. Excitingly, cells that harbor an H3K27M mutation are hypersensitive to DNA demethylating agents [202]. This result suggests that targeting the crosstalk between histone lysine methylation and DNA methylation may have therapeutic potential in patient tumors driven by PRC2 loss of function mutations.

Microdeletions and somatic missense mutations to NSD1 have been identified in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) [203,204] as well as a subset of squamous cell carcinomas of the lung [205]. These mutations result in loss of NSD1 function and a subsequent decrease in levels of H3K36me2 [206]. Additionally, histone H3K36M mutations were identified in a subset of HPV-negative HNSCCs [206]. In the case of H3K36M mutation both H3K36me2 and H3K36me3 levels are reduced owing to the dominant negative effects of H3K36M mutations on H3K36-specific KMTs. In HNSCC, loss of H3K36me2, leads to DNA hypomethylation. Despite the fact that the DNA hypomethylation observed in this subtype of HNSCC promotes de-repression of transposable elements, these tumors are immune-cold, a phenotype which appears to be related to the interplay between H3K36 and H3K27 methylation [207]. This hypothesis is strengthened by the observation that loss of H3K36me2 domains leads to increases in H3K27me3 in the same regions [208]. This example emphasizes the context-dependent functionality of DNA methylation and its crosstalk with histone lysine methylation.

In contrast to the NSD1 loss-of-function mutations that are observed in squamous cell carcinomas, a subset of AML is driven by an oncogenic fusion of NSD1 to NUP98, resulting in a gain-of-function NSD1 protein [209]. AML patients with an NSD1-NUP98 fusion event have a poorer prognosis and their tumors exhibit a characteristic HOX-gene expression profile [210]. Mechanistically, NSD1 gain-of-function leads to an increase in H3K36 methylation at homeobox genes which promotes their expression by blocking EZH2 activity in these regions. This oncogenic fusion event represents another scenario in which tipping the balance between H3K36 and H3K27 methylation promotes a pathogenic transcriptional program (Figure 5).

A significant proportion of multiple myeloma cases are driven by the translocation t(4;14)(p16.3;q32.3) that fuses NSD2 with the immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene, IGHG1 [211]. This translocation event promotes hyperactivity of NSD2 and a gain in H3K36me2 levels [212]. A subset of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cases also harbor this translocation and exhibit increased levels of H3K36me2 with concomitant reduction in H3K27me3 levels [213]. Interestingly, some ALL cases lack t(4;14) translocation, yet still exhibit increased levels of H3K36me2. In these cases, heterozygous, somatic NSD2 mutations were identified which produce a hyperactive NSD2 enzyme [213]. Together, these studies highlight the importance of H3K36me2 and its relationship with H3K27me3 in the regulation of hematopoietic stem cell differentiation and self-renewal. This theme is reminiscent of the loss-of-function EZH2 mutations seen in additional hematological malignancies, indicating that the balance between H3K36 and H3K27 methylation is critical for proper chromatin regulation.

Hundreds of somatic SETD2 mutations have been identified across a variety of human cancers, the most notable being clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) [214]. Others include high-grade glioma, uterine carcinomas, bladder carcinoma, melanomas, lung, colorectal, pancreatic and stomach adenocarcinomas, as well as several hematological malignancies. The prevalence of SETD2 mutations in a wide array of human cancers emphasizes its role as a tumor suppressor gene. Moreover, cancer associated SETD2 mutations do not cluster within a particular domain of the protein, but rather are scattered across the full SETD2 coding region [214]. SETD2 is multifunctional protein with roles in transcription, mRNA processing, cytoskeleton organization, DNA replication and damage repair, and chromatin organization; thus, it logically follows that SETD2 loss-of-function leads to cancer development (Figure 5). While some of these functions are mediated through its deposition of H3K36me3, others involve independent functions, such as methylation of non-histone targets. Future research should focus on these additional SETD2 functions to precisely define its role in these various processes and how SETD2 mutation could give rise to such a wide array of malignancies.

In summary, somatic mutations to DNMTs or KMTs are prevalent in a wide array of cancer types, and the molecular themes involved mirror what is observed with germline mutations to these enzymes in neurodevelopmental disorders (Figure 5). These parallels emphasize the critical function of DNA methylation and histone lysine methylation crosstalk in maintaining epigenomic balance to control gene expression programs that determine cellular fate. More specifically, the prevalence of PRC2, H3K4 KMT, and H3K36 KMT mutations in hematological malignancies indicates that the balance of bivalent chromatin, as well as the balance between H3K27 and H3K36 methylation plays a major role in hematopoietic stem cell differentiation. In some cases, the loss of histone lysine methylation may render cancer cells more sensitive to therapeutic intervention, such as the use of DNA demethylating agents in tumors that harbor H3K27M mutation [202]. Moving forward, development of therapies that target the signaling axes between DNA methylation and histone lysine methylation may provide additional treatment efficacy when combined with the current standards of care.

PERSPECTIVES