Abstract

Protein homeostasis is the basis of normal life activities, and the proteasome family plays an extremely important function in this process. The proteasome 20S is a concentric circle structure with two α rings and two β rings overlapped. The proteasome 20S can perform both ATP-dependent and non-ATP-dependent ubiquitination proteasome degradation by binding to various subunits (such as 19S, 11S, and 200 PA), which is performed by its active subunit β1, β2, and β5. The proteasome can degrade misfolded, excess proteins to maintain homeostasis. At the same time, it can be utilized by tumors to degrade over-proliferate and unwanted proteins to support their growth. Proteasomes can affect the development of tumors from several aspects including tumor signaling pathways such as NF-κB and p53, cell cycle, immune regulation, and drug resistance. Proteasome-encoding genes have been found to be overexpressed in a variety of tumors, providing a potential novel target for cancer therapy. In addition, proteasome inhibitors such as bortezomib, carfilzomib, and ixazomib have been put into clinical application as the first-line treatment of multiple myeloma. More and more studies have shown that it also has different therapeutic effects in other tumors such as hepatocellular carcinoma, non-small cell lung cancer, glioblastoma, and neuroblastoma. However, proteasome inhibitors are not much effective due to their tolerance and singleness in other tumors. Therefore, further studies on their mechanisms of action and drug interactions are needed to investigate their therapeutic potential.

Keywords: Bortezomib, Cancer therapy, Immunoproteasome, Multiple myeloma, Proteasome 20S, Proteasome inhibitor, Thymoproteasom

Introduction

Proteasome 20S is the major proteolytic enzyme in eukaryotes, which plays an important role in the regulation of intracellular protein stability. It is a hollow barrel structure composed of 28 αβ subunits,1,2 which is proteolytically active and plays the primary function of protein degradation.3 20S particle can bind to PA700 particle to play the role of ubiquitinating ATP-dependent protein degradation. It can also bind to PA28 particle to play an ATP-independent role in protein degradation. The ubiquitin proteasome system is involved in maintaining the stability of several proteins implicating in the regulation of cell cycle and division, DNA repair and transcription, the immune response and inflammation, antigen processing, differentiation, and cell development and apoptosis,4,5 especially in cancer cells.6 Generally speaking, normal cells remove excess and unfolded or misfolded proteins by protease-mediated hydrolysis, thus maintaining intracellular proteostasis.7 In the development and progression of cancer, abnormal protein degradation caused by proteases is one of the significant causes, depending on the different tumor signaling pathways, and proteasomes also play various roles in different pathways.8, 9, 10, 11 It is now known that proteasomes are also involved in processes related to tumorigenesis as well as affecting penetration into non-growing cells, especially cancerous ones. In addition, immunoproteases and thymoproteasomes play important roles in the selection of CD8+ T cells, which provides a new idea for tumor immunotherapy.12,13 Today, scientists have confirmed the links between abnormalities of proteasome function and various diseases such as multiple myeloma (MM) and glioblastoma. Therefore, targeting proteasomes or regulating the function of intracellular protein through proteasomes may be an effective way of tumor therapy.14, 15, 16 So far, bortezomib has been approved by the FDA as a useful drug for the treatment of MM, but its efficacy in other tumors is still in the clinical research stage. In this review, we will focus on the source, structure, and function of the proteasome and emphasize its progress in tumor research in recent years, as well as its application and prospects in clinical practice.

How are proteasomes discovered?

Early biologists thought that proteins were stable and hardly suffered damage from external factors. Until the 1930s, Rudolf et al confirmed that protein stability was due to a balance between synthesis and degradation.17 In the 1950s, the discovery of lysosome dynamic balance established a new understanding of protein decomposition.18,19 By 1953, Simpson suggested that there may be two mechanisms for protein degradation: “one hydrolytic, the other energy-requiring".20 Twenty years later, Etlinger and Goldberg discovered a new soluble ATP-dependent protein hydrolysate, which is independent of the lysosome system.21 However, the roles of ATP-dependent protein degradation and lysosomal decomposition were not clear at that time.

In 1983, Wilk and Orlowski first discovered a large “polycatalytic protease” complex containing chymotrypsin and proteinase-like activity in the pituitary gland. This complex did not exist in lysosomes, but in the cytoplasm.22,23 Later, a number of names for this complex have appeared in the literature, including polycatalytic protease, polycatalytic endopeptidase complex, ATP-stimulated alkaline protease, potentially alkaline multifunctional protease, “macropain”, but we prefer to call it “proteasomes".24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29

What is the structure of proteasomes?

The proteolytic activity in eukaryotic cells is a 700-kDa enzyme complex that is present in the nucleus and cytoplasm of almost all mammalian cells, as well as in yeast and Drosophila.30

Generally speaking, a complete proteasome holoenzyme consists of one core particle with other regulate particles. The core particle is also called proteasome 20S, a hollow tubular structure composed of four heptamer rings, which include two outer rings composed of 7α subunits and two inner rings composed of 7β subunits,31,32 they overlap to form the structure of concentric circles. The X-ray analysis has confirmed that the proteasome 20S particle is a barrel-shaped cylinder composed of a penetrating central channel, three large internal chambers, and a cavity where the misfolded protein can be controlled to enter.33 The α rings have no activity, they only play a gating role for proteasome 20S. In fact, the orifices formed by the α ring at the top are very narrow so that they can restrict protein to get inside it.34 The β rings are the main catalytic subunit, and it is formed by a circle of β1-7. The subunits of β3, β4, β6, and β7 are discordant parts of consisting complete β ring structure, and without their participation, the rate of protein degradation will be reduced. However, the main active subunits β1, β2, and β5 subunits hold three distinct proteolytic activities consisting of caspase-like activity, trypsin-like activity, and chymotrypsin-like activity.35,36

The subunits of the 19S regulate particles functionally control the translocation of ubiquitinated substrates, they consist of a base with ATPase activity and a lid without ATPase activity.37,38 The base subunits participate in substrate binding, unfolding, and translocation, while the lid subunits serve as ubiquitin receptors and are necessary for the binding of ubiquitylated substrates.39,40 The shape of 11s is just like a hat that stimulates the degradation of peptides by opening a channel of the exterior of the proteasome. Unlike the 19S regulators, 11S regulators do not deliver substrate but instead promote the product peptides exit from the interior of the 20S proteasome.41,42

Nevertheless, how do these three subunits perform the role of protein degradation? Emerging evidence indicated that several enzymes have no activity when they are synthesized in the cell, which we called propeptides. In some situations, the propeptides are interrupted by one or more special peptide bonds, leading to certain conformational changes, which we termed active enzymes. The terminal threonine residue of the β subunit is conserved in most eukaryotes, but during the process of biosynthesis, the self-degradation of threonine-dependent propeptides was triggered, and then the terminal threonine is exposed.43 This is the assembly of active 20S proteasome. In 1997, Michael et al2 extracted proteasome 20S crystals from yeast, and they found that calpain inhibitors I with acetyl-Leu-Leu-norleucinal sites can covalently bind to Thr-1, the side chains of calpain inhibitors I project to several amino acids at the ends of β1, β2, and β5 to form pocket-like structures.33 They exactly are the active sites of the proteasome after the propeptide modification. Interestingly, through binding to the inhibitors, the activities of proteasome 20S are greatly blocked44 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The self-degradation of threonine-dependent propeptides exposed the terminal threonine, and the β subunit changed from inactive to active. Calpain inhibitors I can bind to several amino acids at the ends of β1, β2, and β5.

The proteasome 20S is just like a garbage can, which can bind to different subunits to perform different catalytic functions. It is involved in numerous biological processes, including the removal of aberrant proteins, stress response, cell-cycle control, cell differentiation, and cellular immune responses.4, 5, 6

How do proteasomes perform their function?

The proteasome 20S simply degrades the unfolded protein in an energy-independent manner, and it must be bound to the 19S subunit to complete its function.30,45 The regulation particle of 19S consists of a cap-like structure composed of a “cover” and a “base”, which are embedded at both ends of the 20S catalytic core to form a “dumbbell-like” symmetrical structure.34,46 When 20S binds to the 19S subunit, also known as PA700, it selectively degrades ubiquitinated proteins by an ATP-dependent process,47 generally called the proteasome 26S. This is currently the most extensively studied proteasome system, and most proteins in cells are degraded by proteasome 26S system.48 Just as we mentioned before, the opening of the α ring is just like a “door” that resists normal folded proteins entering inside,1,49 while the bottom of 19S is just like a key. When it binds to the top of the α ring, it can open the door and promote the protein into the cavity.50, 51, 52 The substrate carrying ubiquitin chain is recognized by the 19S cap structure, then enters the 20S active center to be degraded, and then is released from the other end of the proteasome.53

Another activator, PA28, also known as 11S regulator, can associate with the proteasome 20S in the absence of ATP.54 Electron microscopy demonstrates that PA28 is a ring-shaped particle, and like PA700, caps the 20S proteasome at both or either end.54 At the same time, it can also combine with 19S to form a “mixed proteasome”. PA28 can promote the hydrolysis of short peptides, this process is independent of ATP, and the hydrolyzed substrate does not need to be combined with ubiquitin. Although PA28-20S is not as extensive as 26S in degrading protein species, it is directly involved in the operation of the adaptive immune system.55

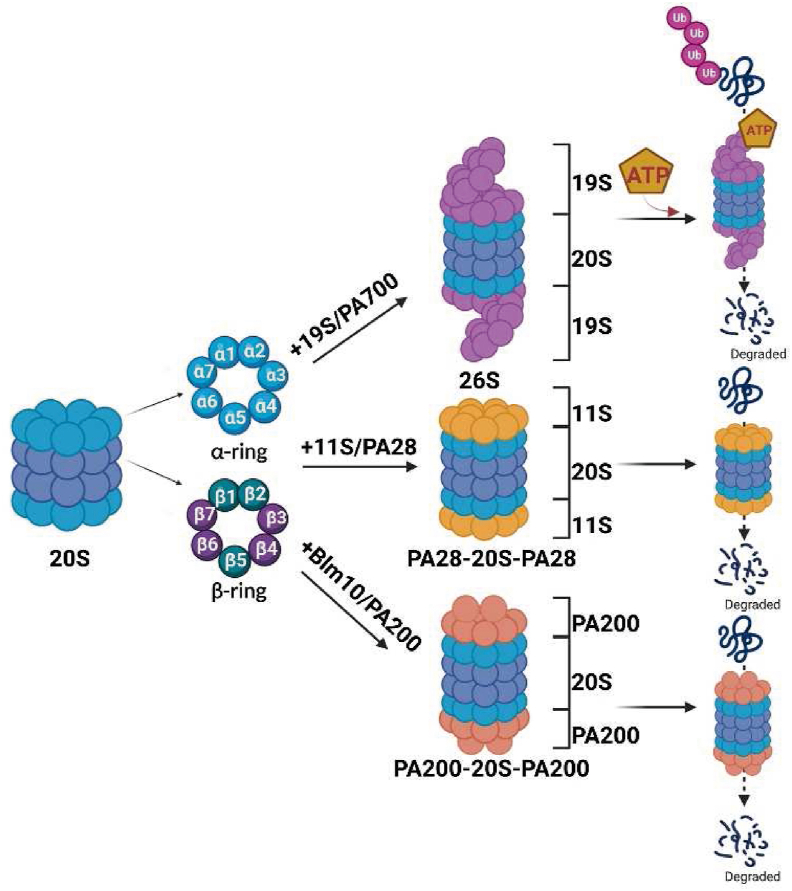

The third proteasome activator is PA200, also known as Blm10 in yeast. Similar to the two above, it binds to the end of 20S particle and acts as a key to open the “door” of the α-ring. It is mainly involved in the degradation of unstructured proteins, such as histones. The substrate does not need ubiquitin labeling in the process of degradation with PA200. However, recent studies have also found that PA200 plays an important role in maintaining histone code stability and delaying aging56 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The proteasome 20S is a concentric circle structure with two α rings and two β rings overlapping. By binding to various subunits, such as 19S, 11S, and 200 PA, it can form the proteasome 26S, PA28-20S-PA28, and PA200-20S-PA200, and execute the function of ATP-dependent and non-ATP-dependent ubiquitination proteasome degradation, which is performed by its active subunit β1, β2, and β5.

Proteasomes and tumor

Proteasome is the key complex of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, which is responsible for the degradation of redundant and misfolded proteins. It has been proved to be critical in the regulation of cell growth and oncogenic transformation.57,58

The role of proteasomes in tumor progression

The progression of tumors involves cell cycle regulation, cell growth, apoptosis, etc. Proteasome inhibitors, as the first-line clinical treatment of MM, also affect the development of MM through multiple aspects. It seems that it can alter cell interactions and cytokine secretion in the tumor microenvironment to inhibit tumor cell growth and associated angiogenesis, induce apoptosis, and appear to overcome drug resistance.59,60 Next, we will introduce how proteasomes play a role in tumorigenesis and highlight the mechanism of proteasomes in MM.

Proteasomes acted on tumor signaling pathway

One of the key tumor signaling pathways regulated by proteasomes is the NF-κB pathway.61 NF-κB is a transcription factor that plays a critical role in the regulation of immune responses, inflammation, and cell survival.62 Dysregulation of NF-κB has been implicated in the development and progression of many types of cancer.63 In the classical pathway, activation of the IκB kinase complex (IκB kinase β/α/γ), leads to the phosphorylation of IκB, an inhibitor of NF-κB, which makes IκBα ubiquitinated and recognized by proteasomes.64, 65, 66, 67 When the proteasomes degrade the inhibitory protein IκB, NF-κB is transferred to the nucleus to promote gene transcription and cell growth.68 In other words, proteasome inhibitors can block the degradation of IκB, leading to the inhibition of NF-κB activity and the induction of apoptosis in cancer cells.69

The other tumor signaling pathway regulated by proteasomes is the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. β-catenin is a transcriptional co-activator that plays a critical role in the regulation of cell proliferation and differentiation.10 Dysregulation of β-catenin has been implicated in the development and progression of many types of cancer.11 Without the presence of Wnt, free β-catenin is bounden with adenomatous polyposis coligene (APC) product, Axin, glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) and CK1, which is also called β-catenin destruction complex.70,71 Subsequent phosphorylation of β-catenin by GSK3β and CK1 drives β-catenin ubiquitination and is responsible for promoting degradation via the proteasome pathway.72

Activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling has been reported to contribute to cancer development and progression.73,74 Thus, suppressing the excessive activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway must be a key therapeutic method.75,76 In previous study, some natural products such as epigallocatechin-3-gallate have been found to inhibit the Wnt/β-catenin signaling by promoting the phosphorylation and ubiquitination of β-catenin, leading to the degradation of β-catenin in the tumor cells.77, 78, 79, 80

The p53 tumor suppressor protein is a critical regulator of cell cycle progression, apoptosis, and senescence.81 As a tumor suppressor gene, p53 mutation is very common in tumorigenesis. The activity of p53 is strictly regulated by changing homeostasis levels and post-translational modification. Proteasome inhibition gives rise to increased p53 expression and stability, thereby promoting the programmed death process.82 Murine double minute 2 (MDM2) is considered an effective inhibitor of p53.83, 84, 85, 86 Through binding to p53, it can reduce its transportation to the cytoplasm for ubiquitination degradation, thus affecting the transcriptional activity, stability, and subcellular localization of p53.87,88 When DNA is damaged, MDM2 can be degraded by self-ubiquitination, allowing the accumulation of p53.89,90 In view of MDM2 playing a key role in regulating the growth, proliferation, and cell cycle progression of cancer cells, drugs targeting the ubiquitin-protease system of p53 and MDM2, such as ubiquitin-specific protease 7 (USP7) inhibitors and SP141 have a good prospect of therapy.8,9,91 The mechanism of it is promoting the degradation of MDM2, thus activating the p53 signaling pathway and causing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis92 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

The role of proteasomes in tumor signaling pathways. Free β-catenin is linked to adenomatous polyposis coligene products (APCs), Axin, glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) and CK1 in the absence of Wnt. Subsequent phosphorylation of β-catenin by GSK3β and CK1 drives β-catenin ubiquitination and is responsible for promoting degradation via the proteasome pathway. Activation of the IκB kinase complex leads to phosphorylation of IκBα, which leads to IκBα ubiquitination and degradation by proteasomes. Then NF-κB is transferred to the nucleus to promote gene transcription and cell growth. Proteasome inhibitors can inhibit the ubiquitin-protease system and reduce the degradation of IκB. Murine double minute 2 (MDM2) can reduce p53 transportation to the cytoplasm for ubiquitination degradation by binding to it, thus affecting the transcriptional activity of p53. When DNA is damaged, MDM2 can be degraded by self-ubiquitination, allowing the accumulation of p53. Ubiquitin-specific protease 7 (USP7) inhibitors can inhibit the ubiquitin-protease system and promote the degradation of MDM2. Proteasome inhibitors increased the level of JNK with the consequent increase in c-Jun phosphorylation. These events increase AP-1 activity, which can induce the expression of downstream genes and trigger apoptosis in tumor cells.

An important role in the control of the apoptotic mechanism is exerted by the c-Jun/JNK/AP-1 pathway. Proteasome inhibition will lead to the activation of JNK, which is an important activator of phosphorylated c-Jun. When it is activated, with c-Fos, it forms a dimer AP1; a transcription factor involved in the regulation of several cell processes,93,94 which can induce the expression of downstream genes such as Fas-L and trigger apoptosis in tumor cells.95

In addition to the several signaling pathways we mentioned above, proteasomes also regulate other tumor signaling pathways, such as the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, the Notch pathway, and the Hedgehog pathway.96, 97, 98 There are also close links between different signaling pathways, for example, β-catenin overexpression protects p53 protein from MDM2-mediated proteasome degradation, thereby stabilizing p53 protein and increasing its transcriptional activity.99,100 However, the activation of p53 down-regulates β-catenin through GSK3β phosphorylation mediated proteasome degradation.101,102 Proteasome plays a critical role in the regulation of tumor signaling pathways and dysregulation of proteasome activity has been implicated in the development and progression of many types of cancer.16,103, 104, 105 Generally speaking, proteasomes also play different roles in tumor cells according to different tumor signaling pathways. For example, signaling pathways that activate tumor proliferation and development require overexpressed proteasomes to down-regulate their expression, whereas, for the down-regulation of signaling pathway factors that deter tumor growth, proteasome inhibitors are needed to reduce their degradation.

Proteasomes acted on cell cycle

The cell cycle is a necessary process for cell proliferation. According to their different modes of function, cell cycle regulation can be divided into positive regulators and negative regulators. If negative regulators such as CKI are not degraded in time, cells will be arrested in a certain cycle, resulting in cell death and misdifferentiation. Positive regulators, such as cyclin and CDK, can generally promote the process of cell division. If they are not degraded in time, abnormal cell differentiation will lead to tumor.106, 107, 108, 109 Given that ubiquitin-proteasome pathway-mediated cyclin hydrolysis plays an important role in this process, the degradation of cycle-regulated proteins is abnormal in many cancers. Furthermore, p21 family members (p21, p27, and p57) could inhibit CDK complex activity and affect progression of the cell cycle. Low levels of p21 and p27, brought about by proteasome hyperactivity, represent a negative prognostic factor in several types of cancers. As a result, inhibiting action by the proteasome leads to up-regulation of these proteins, which may lead to apoptosis in tumoral cells in vitro.110, 111, 112 Given that the cyclin-D1-CDK4 complex is required for the G1-S phase and cyclin B1-CDK1 complex is required for mitosis,113, 114, 115 proteasome inhibitor prevents the proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma cells during these phases by inhibiting cyclins A1, B1, and D1, as well as CDKs1 and 4.114, 115, 116 It can also prevent cell cycle progression via the reduction of hyperphosphorylated E2F1 and cyclin D1, which is associated with an up-regulation of the cell cycle inhibitors p27Kip1 and p21waf1/cip1.117 In addition, studies have shown that CDK15 may be the downstream target of PA28, the down-regulation of PA28 can effectively inhibit the invasion and metastasis of breast cancer, and save the expression of CDK15 protein, but the silencing of CDK15 can, in turn, improve the inhibition of PA28. But the exact molecular mechanism between them needs further study.118

Immunoproteasome and drug resistance

When the immune response occurs, interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α can induce the expression of PA28 and special β subunits (β1i, β2i, and β5i),119 forming a special structure, we called it “immunoproteasome".120 It can degrade the invading pathogens into peptide segments of appropriate size for binding to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), deliver them to the surface of antigen-presenting cells,121 and then pass the signal to the CD8+ T cell13,122,123 (Fig. 4). Thus, the immunoproteasome β1i, β2i, and β5i subunits play an important role in preventing virus infection. However, its deficiency may also protect cancer cells from immune attack,121,124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130 immune proteasome can be used to replace constitutive proteasome (β1, β2, and β5) to exercise the role of protein degradation. Therefore, large numbers of immune proteasomes may promote tumor growth and lead to resistance to proteasome inhibitors.131, 132, 133, 134

Figure 4.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interferon (IFN)-β can induce the production of immunoproteasome β1i, β2i, and β5i and thymoproteasome β1i, β2i, and β5t, which contribute to the degradation of the invasive pathogens, following by changing those pathogens into peptide segments with appropriate size for major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I binding in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), deliver them to the surface of antigen-presenting cells (APCs), and then pass the signal to the CD8+ T cell. TCR, T cell receptor.

The seemingly contradictory role of immune proteasomes provides a new insight for tumor targeting drugs, but it also requires us to have a good understanding of the mechanism according to different types of cancer and the functions of proteasomes.

For example, LMP7, one of the functional subunits of immunoproteasome β5i, encoded by PMSB8, significantly reduced the tumor burden in colon cancer mice and blocked tumor initiation and progression.133 Interestingly, as a β5i inhibitor, PR-924 also has a significant effect on the growth inhibition and inducing apoptosis of MM in vivo and in vitro. In addition, PR-924 treatment can prolong the survival time of tumor-bearing mice.135 In the early stage of non-small cell lung cancer, low expression of immunoproteasome subunits can enable tumor cells to evade immune surveillance, which not only causes tumor cell recurrence and metastasis but also reduces disease-free survival. Induction of immunoproteasome by IFN-γ or 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine can overcome the immune escape mechanism of mesenchymal cells by restoring the function of HLA class I-bound peptides.136

Thymoproteasome: An essential part of CD8+ T cell optimal generation

The thymus is an essential part of T cell development, from which we detected a special proteasome termed thymoproteasome in cortical thymic epithelial cells.12,137, 138, 139 Thymoproteasome is characterized by β5t,12,140,141 which generates a unique spectrum of MHC class I-associated peptides and plays a critical role in thymic positive selection of CD8+ T cells.12 Though thymoproteasomes have similar structures to immunoproteasomes, which consist of β1i, β2i, and β5t subunits (Fig. 4), the hydrophilic residues in β5t have lower chymotrypsin-like activity compared with β5i, which exhibits a unique substrate specificity in endopeptidase proteolysis.12,140,142 Through the analysis of β5t-deficient mice, we will discover a significant decrease of CD8+ T cells whereas no obvious change was seen in CD4+ T cells, NKT cells, B cell DCs, and other cells compared with control group.12,143 Because proteasomes are responsible for the production of relative peptides and are presented by CD8+ T cells, it makes sense that thymoproteasome is able to display a unique set of peptides associated with cell-surface MHC class I molecules and positive recognized by CD8+ T cells.144, 145, 146, 147, 148 However, the mechanism for thymoproteasome-dependent CD8+ T cell production in the thymus remains unclear. There have been two main hypotheses that revealed how CD8+ T cells selected peptides degraded by thymoproteasome specifically. One of the hypotheses is “self-peptide",149,150 which showed that thymoproteasome-dependent-self-peptide may create a difference between cortical thymic epithelial cells and other antigen-presenting cells. This difference provides a chance for positively selected CD8+ T cells to escape from a negative selection of other cells.147,151 The second hypothesis is “low affinity motif”; consistent with this view, thymoproteasome-dependent MHC class I-associated peptides have low–affinity interaction with T cell receptors, which promotes the positive selection of CD8+ T cells.141,148,152,153

As β5t is expressed in most cases of type B but not type A, thymoproteasomes are also a detective target useful in differentiating type A from type B thymoma. Morphologically, type A and type B thymomas exhibit differentiation into mTECs and cortical thymic epithelial cells, respectively. Therefore, β5t retains its normal physiologic expression pattern in the context of thymoma and is a reliable marker for detecting neoplastic epithelial cells differentiating into cortical thymic epithelial cells.154, 155, 156

In terms of such advantages, research on the immunoproteasomes and thymoproteasomes may contribute to improving the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors as well as therapies for other immune disease. Nevertheless, the development of an inhibitor specific to thymoproteasomes has also been attempted but has not yet succeeded. The development of inhibitors specific to immunoproteasomes would provide a promising tool for treating cancer and immunological diseases in the future.

Regulation of tumor by proteasome-encoded genes

At the genetic level, many proteasome subunit genes are closely related to tumor progression. A variety of genes encoding the proteasome subunit have been found to be up-regulated in various tumors.157, 158, 159, 160 In 2007, Deng et al analyzed the difference in proteasome genes between breast cancer tissues and normal tissues by RT-PCR and found that several 26S particle subunits coding genes were up-regulated, including PSMB5, PSMD1, PSMD2, PSMD8, and PSMD11.161 Hepatitis B virus is one of the most common risk factors for liver cancer. Interestingly, it has been reported that proteasome is a potential cellular target of HBx.162 Many previous studies have shown that HBx interacts with proteasome subunits (including PSMA1, PSMA7, PSMB7, PSMC1, and PSMC3163) which influence hepatitis B virus replication through the proteasome-dependent pathway.164 PMSF7 encodes the proteasome α subunit and its mRNA level was found to be significantly different between colorectal and normal tissues by RT-PCR. PMSF7 expression was elevated in colorectal cancer as well as metastasis and negatively correlated with survival.165 The protein subunit encoded by PSMD2 is a part of the 19S particle, which is essential for the assembly of both the 19S and 20S proteasomes.166,167 Studies have demonstrated that PSMD2 is significantly up-regulated in breast cancer and is associated with poor prognosis. Knockdown of PSMD2 in breast cancer cells can effectively inhibit cell proliferation and arrest cell cycle at G0/G1, which is caused by the up-regulation of p21 and p27. In terms of mechanism, PSMD2 interacts with p21 and p27 and mediates ubiquitin-proteasome degradation in coordination with USP14.168

Tumor drug resistance is also a key factor in cancer treatment failure. Studies have found that in microarray samples of 1592 breast cancer patients, PSMB7 (gene encoded β5) has been found to be overexpressed in breast cancer cells and associated with poor prognosis. Interestingly, by comparing the expression profiles of adriamycin resistance in four different pairs of human tumor cell lines, PSMB7 overexpression could be found in the drug-resistant cell lines, and the resistance of the cells was weakened after PSMB7 was silenced by RNA interference.169 This provides a new idea for the mechanism of cell drug resistance. Perhaps we can use proteasome inhibitors to target cell drug resistance.

Proteasome-targeted tumor therapy

Proteasome inhibitors, on the one hand, can interfere with the protein metabolism of tumor cells, making the tumor overburdened; second, they can relieve the degradation of tumor suppressor factors, thus playing a role in tumor treatment. In addition, proteasome inhibitors are more sensitive to tumor cells than normal cells, which can prevent tumor cell proliferation, selectively induce tumor cell apoptosis, and increase the sensitivity to radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

Excessive proliferation of tumor cells requires proteasome to maintain homeostasis to eliminate the accumulation of misfolded proteins. For example, MM originates from the hyperproliferation of bone marrow plasma cells, which makes malignant plasma cells secrete more immunoglobulins than normal plasma cells. Immunoglobulin is a macromolecule synthesized and folded in the ER.170 The production of high immunoglobulins makes MM cells heavily dependent on proteasomes to maintain ER homeostasis, so they are more sensitive to proteasome inhibition.171 So far, some proteasome inhibitors have been approved by the FDA for the treatment of tumors. It is widely known that bortezomib, carfilzomib, and ixazomib, are used in the treatment of MM and mantle cell lymphoma (Table 1).

Table 1.

Proteasome inhibitors for targeted tumor therapy.

| Proteasome inhibitor | Substitute name(s) | Targeted tumors or diseases | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bortezomib | PS-341, MG-341, Velcade | New diagnosis multiple myeloma, pancreatic cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, non-small cell lung cancer, breast cancer, renal cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinomas, ovarian cancer | Wide range of indications; various treatment schemes | High drug resistance rate; high incidence of peripheral neuropathy | 115, 116, 117, 121, 124, 146, 147, 148 |

| Carfilzomib | Kyprolis | Relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma, glioblastoma | High specificity; better curative effect for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma; low incidence of peripheral neuropathy | High incidence of cardiac and renal toxicity | 114, 125, 126, 127, 128 |

| Ixazomib | Ninlaro | Relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma, neuroblastoma, hepatocellular carcinoma | Save medical costs; enrich relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma treatment methods; improve patients' quality of life | Single treatment plan; the curative effect advantage is not clear | 114, 125, 129, 130, 132, 133 |

| Marizomib | Salinosporamihe A | Multiple myeloma, glioblastoma | Not mention | Not mention | 174, 175 |

| Oprozomib | ONX-0912 | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma | Not mention | Not mention | 178, 179 |

| PR957 | ONX-0914 | Colitis-associated cancer, glioblastoma, lymphoblastic leukemia, prostate cancer | Not mention | Not mention | |

| DPLG3 | Not mention | Immune diseases | Not mention | Not mention | |

| LU-005i | Not mention | Immune diseases | Not mention | Not mention |

Generation I proteasome inhibitor: Bortezomib

Bortezomib is the first proteasome inhibitor as a chemotherapy drug,172,173 it can effectively bind to the β5 subunit of proteasome 20S and inhibit its catalytic activity for substrate degradation.174 MM can lead to an increase in serum proteasome levels, and successful chemotherapy can effectively restore the proteasome level to the normal range.175 Animal studies have shown that bortezomib may also have significant clinical effects on pancreatic cancer with extremely high mortality.176,177 Because bortezomib can act on both new diagnosis MM and relapsed/refractory MM, it has a wide range of indications.173 In addition, it can be combined with alkylating agents, immunomodulators, and monoclonal antibodies to form various schemes, so it has a wide range of clinical applications. Also, it has been reported that bortezomib can induce increased transcription and post-translation of cyclin-dependent kinase p21 and p27 in hepatocellular carcinoma, non-small cell lung cancer, breast cancer,178,179 and pancreatic cancer,180 which leads to growth inhibition and apoptosis in those tumor cells.117,181 Bortezomib, which has the ability to inhibit NF-κB signaling pathways and thus affect tumor occurrence, has also been reported in a variety of cancers including renal cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinomas, and ovarian cancer.124, 125, 126

However, bortezomib has poor specificity; it inhibits β subunits while affecting other subunits, so it has certain damage to normal cells.182 At the same time, bortezomib is still resistant to some tumor patients in clinical application and may induce peripheral neuropathy.173 Therefore, the second-generation proteasome inhibitor carfilzomib was developed.

Generation II proteasome inhibitor: Carfilzomib

In specificity, carfilzomib mainly acts on proteasome β5 subunit, and its ability to bind to other subunits is lower than bortezomib,183 so its specificity is better.184 Compared with bortezomib, carfilzomib has better curative effect on relapsed/refractory MM, and the incidence of peripheral neuropathy is lower.172 However, despite its high selectivity and irreversible advantages, its associated heart and kidney problems have raised clinical concerns.185,186 A recent study shows that carfilzomib can specifically induce tumor cell death and inhibit tumor growth when drug screening is carried out in glioblastoma, so protease inhibitors can be used as a potential targeted therapy for glioblastoma.187

The first oral proteasome inhibitor: Ixazomib

Ixazomib is the first oral proteasome inhibitor.183,188 At present, ixazomib as a first-line treatment, is recommended in domestic and foreign countries to treat relapsed/refractory MM. The advantages of ixazomib are lower incidence of peripheral neuropathy, higher safety of heart and kidney than carfilzomib, and oral administration; these will save medical resources, improve patients' quality of life, and bring more benefits to relapsed/refractory MM patients.172,189 In addition, recent studies have demonstrated that ixazomib can induce apoptosis in neuroblastoma in vitro and in vivo by inhibiting doxorubicin-induced NF-κB activity and sensitizing neuroblastoma cells to doxorubicin-induced apoptosis.190 However, its disadvantage is that the treatment plan is single, and the curative effect advantage compared with other proteasome inhibitors is unknown.191,192 Sorafenib has been the standard treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma.193,194 However, recent studies have shown that the combination of ixazomib and the CDK inhibitor dinaciclib is effective in treating hepatocellular carcinoma. In vitro and in vivo studies have shown that ixazomib plus dinaciclib has synergistic pro-apoptotic and anti-proliferative activities and is superior to sorafenib in reducing patient-derived xenografts in mice.195

Other proteasome inhibitors

There are other compounds currently in clinical trials, including marizomib, oprozomib, and delanzomib.172,196, 197, 198 Studies have found that marizomib (Salinosporamihe A) can not only treat MM but also cross the blood–brain barrier, so it can be used to treat glioblastomas.199,200 In addition, marizomib has promising anticancer activity in triple-negative breast cancer xenografts and can reduce lung and brain metastases by reducing the number of circulating tumor cells and the expression of genes involved in epithelial–mesenchymal transition.201 Oprozomib (ONX0912) is a truncated derivate of carfilzomib with better oral bioavailability compared with intravenously administrated carfilzomib.202 In head and neck squamous cell carcinoma xenograft models, carfilzomib and oprozomib were found to induce apoptosis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells by up-regulating pro-apoptotic Bik.203 Oprozomib reduces the viability and proliferation of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells in a dose-dependent manner, it also has a good anti-tumor effect in xenograft hepatocellular carcinoma model.204

PR957 (ONX0914), as a proteasome inhibitor, specifically targets immunoproteasome β5i subunit and has been verified in several experienced models such as colitis-associated cancer, glioblastoma, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and prostate cancer.133,205, 206, 207, 208, 209, 210, 211, 212 Moreover, DPLG3, a non-covalent β5i-specific inhibitor, and LU-005i, a pan-immunoproteasome inhibitor that targets all three active subunits, have shown therapeutic efficacy in immune diseases in mice.210,213 These results demonstrated that specific immunoproteasome inhibitors have a potential value to entrain a long-term response favorable to tumor suppression, and selectively affect the function of activated immune cells while sparing other cell types that would be damaged by treatment with classical proteasome inhibitors.

In the past 20 years, the treatment strategy of MM has changed greatly due to the introduction of proteasome inhibitors, which have significantly improved the survival and prognosis of patients. However, the side effects and curative effects of different proteasome inhibitors are not completely clear. Therefore, we need to know the characteristics of each proteasome inhibitor in further clinical trials and make the best treatment choice according to the specific condition of patients, to reduce the occurrence of adverse reactions. In addition, proteasome inhibitors have a variety of selectivity in the treatment of MM at present, but no significant therapeutic advantage has been found in other cancers. Therefore, it is an urgent problem to explore the role of proteasome inhibitors in other tumors, which may provide a new strategy for targeted tumor therapy.

Conclusions and future directions

The process of life activities requires the metabolism of cells to maintain homeostasis, and the normal degradation of cycle-regulated proteins can make the cell cycle enter the normal order. Once the ability of cells to enter the S phase decreases, it will eventually lead to cell death or abnormal differentiation, and the abnormal DNA synthesis in cells will lead to the occurrence of tumors.214

Proteasome inhibitors have achieved great success in gaining clinical approval, which provides new directions for treatment strategies in different cancers. At present, proteasome inhibitors have been used as a first-line therapy in hematological tumors, but no significant advantage has been found in other tumors. However, the pro-apoptotic, anti-proliferative, and cytotoxic effects of bortezomib, as well as its negligible toxicity to normal hepatocytes, make it a potential new therapeutic approach for cancers. More and more studies have shown that by understanding the mechanism and driving factors of proteasomes in tumors, we can better combine proteasomes with other anticancer drugs to make excellent use of their advantages in treatment.215,216 For example, it can be used in combination with sorafenib to further down-regulate p-AKT and overcome apoptotic resistance in bortezomib resistance.217,218 Together with other kinase inhibitors such as chloroquine and mTOR inhibitors (rapamycin), they enhance apoptosis and reduce xenograft tumor size in vitro.219, 220, 221, 222 Similarly, bortezomib can function effectively in combination with gene drugs and histone deacetylase inhibitors.223, 224, 225, 226 Bortezomib can inhibit the development of tumors in different ways, not only through the classical pro-apoptotic pathway but also inhibit the metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma via epithelial–mesenchymal transition process and cancer stem cells.114,227, 228, 229, 230

In conclusion, on the one hand, proteasome inhibitors have been developed as a therapeutic strategy for cancer treatment. These inhibitors can block the degradation of tumor suppressor proteins, leading to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in cancer cells. On the other hand, proteasome inhibitors have been shown to have therapeutic potential in the treatment of various types of cancer, including MM, lymphoma, and solid tumors.

However, proteasome inhibitors can also have toxic effects on normal cells, and their use in cancer treatment must be carefully monitored. In addition, cancer cells can develop resistance to proteasome inhibitors, which can limit their effectiveness as a therapeutic strategy. Therefore, continued research is needed to better understand the role of proteasomes in cancer and to develop more effective and targeted therapies for cancer treatment.

Conflict of interests

No potential conflict of interests was disclosed.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82172619), the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing, China (No. CSTC2021jscx-gksb-N0023), and the Medical and Industrial Integration Project (China) (No. 2022CDJYGRH-002).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chongqing Medical University.

Contributor Information

Li Zhou, Email: lilyzhou01@163.com.

Tingxiu Xiang, Email: xiangtx@cqmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Groll M., Bajorek M., Köhler A., et al. A gated channel into the proteasome core particle. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7(11):1062–1067. doi: 10.1038/80992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Groll M., Ditzel L., Löwe J., et al. Structure of 20S proteasome from yeast at 2.4 A resolution. Nature. 1997;386(6624):463–471. doi: 10.1038/386463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heinemeyer W., Fischer M., Krimmer T., Stachon U., Wolf D.H. The active sites of the eukaryotic 20 S proteasome and their involvement in subunit precursor processing. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(40):25200–25209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.25200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finley D., Ciechanover A., Varshavsky A. Ubiquitin as a central cellular regulator. Cell. 2004;116:S29–S34. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00971-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melino G. Discovery of the ubiquitin proteasome system and its involvement in apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12(9):1155–1157. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeMartino G.N., Slaughter C.A. The proteasome, a novel protease regulated by multiple mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(32):22123–22126. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldberg A.L. Protein degradation and protection against misfolded or damaged proteins. Nature. 2003;426(6968):895–899. doi: 10.1038/nature02263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang W., Qin J.J., Voruganti S., et al. Identification of a new class of MDM2 inhibitor that inhibits growth of orthotopic pancreatic tumors in mice. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(4):893–902.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang W., Hu B., Qin J.J., et al. A novel inhibitor of MDM2 oncogene blocks metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma and overcomes chemoresistance. Genes Dis. 2019;6(4):419–430. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2019.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clevers H., Nusse R. Wnt/β-catenin signaling and disease. Cell. 2012;149(6):1192–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Y., Wang X. Targeting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13(1):165. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00990-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shigeo M., Katsuhiro S., Toshihiko K., et al. Regulation of CD8⁺ T cell development by Thymus-specific proteasomes. Science. 2007;316(5829):1349–1353. doi: 10.1126/science.1141915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basler M., Kirk C.J., Groettrup M. The immunoproteasome in antigen processing and other immunological functions. Curr Opin Immunol. 2013;25(1):74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Catalgol B. Proteasome and cancer. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2012;109:277–293. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-397863-9.00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park J., Cho J., Song E.J. Ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) as a target for anticancer treatment. Arch Pharm Res (Seoul) 2020;43(11):1144–1161. doi: 10.1007/s12272-020-01281-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rousseau A., Bertolotti A. Regulation of proteasome assembly and activity in health and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19(11):697–712. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0040-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rudolf M. New form of insulin: crystallized protamine insulin (NPH 50) Concours Med. 1951;73(45):3755–3757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeDuve C., Gianetto R., Appelmans F., Wattiaux R. Enzymic content of the mitochondria fraction. Nature. 1953;172(4390):1143–1144. doi: 10.1038/1721143a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duve C.D., Pressman B.C., Gianetto R., Wattiaux R., Appelmans F. Tissue fractionation studies. 6. Intracellular distribution patterns of enzymes in rat-liver tissue. Biochem J. 1955;60(4):604–617. doi: 10.1042/bj0600604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simpson M.V. The release of labeled amino acids from the proteins of rat liver slices. J Biol Chem. 1953;201(1):143–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bigelow S., Hough R., Rechsteiner M. The selective degradation of injected proteins occurs principally in the cytosol rather than in lysosomes. Cell. 1981;25(1):83–93. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90233-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilk S., Orlowski M. Cation-sensitive neutral endopeptidase: isolation and specificity of the bovine pituitary enzyme. J Neurochem. 1980;35(5):1172–1182. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1980.tb07873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilk S., Orlowski M. Evidence that pituitary cation-sensitive neutral endopeptidase is a multicatalytic protease complex. J Neurochem. 1983;40(3):842–849. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1983.tb08056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishiura S., Sano M., Kamakura K., Sugita H. Isolation of two forms of the high-molecular-mass serine protease, ingensin, from porcine skeletal muscle. FEBS Lett. 1985;189(1):119–123. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(85)80854-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ray K., Harris H. Purification of neutral lens endopeptidase: close similarity to a neutral proteinase in pituitary. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82(22):7545–7549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.22.7545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGuire M.J., Croall D.E., DeMartino G.N. ATP-stimulated proteolysis in soluble extracts of BHK 21/C13 cells. Evidence for multiple pathways and a role for an enzyme related to the high-molecular-weight protease, macropain. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1988;262(1):273–285. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(88)90189-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanaka K., Ii K., Ichihara A., Waxman L., Goldberg A.L. A high molecular weight protease in the cytosol of rat liver. I. Purification, enzymological properties, and tissue distribution. J Biol Chem. 1986;261(32):15197–15203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Falkenburg P.E., Haass C., Kloetzel P.M., et al. Drosophila small cytoplasmic 19S ribonucleoprotein is homologous to the rat multicatalytic proteinase. Nature. 1988;331(6152):190–192. doi: 10.1038/331190a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arrigo A.P., Tanaka K., Goldberg A.L., Welch W.J. Identity of the 19S 'prosome' particle with the large multifunctional protease complex of mammalian cells (the proteasome) Nature. 1988;331(6152):192–194. doi: 10.1038/331192a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matthews W., Driscoll J., Tanaka K., Ichihara A., Goldberg A.L. Involvement of the proteasome in various degradative processes in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86(8):2597–2601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baumeister W., Dahlmann B., Hegerl R., Kopp F., Kuehn L., Pfeifer G. Electron microscopy and image analysis of the multicatalytic proteinase. FEBS Lett. 1988;241(1–2):239–245. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)81069-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kleinschmidt J.A., Hügle B., Grund C., Franke W.W. The 22 S cylinder particles of Xenopus laevis. I. Biochemical and electron microscopic characterization. Eur J Cell Biol. 1983;32(1):143–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Löwe J., Stock D., Jap B., Zwickl P., Baumeister W., Huber R. Crystal structure of the 20S proteasome from the archaeon T. acidophilum at 3.4 A resolution. Science. 1995;268(5210):533–539. doi: 10.1126/science.7725097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coux O., Tanaka K., Goldberg A.L. Structure and functions of the 20S and 26S proteasomes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:801–847. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.004101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dick T.P., Nussbaum A.K., Deeg M., et al. Contribution of proteasomal beta-subunits to the cleavage of peptide substrates analyzed with yeast mutants. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(40):25637–25646. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kisselev A.F., Akopian T.N., Castillo V., Goldberg A.L. Proteasome active sites allosterically regulate each other, suggesting a cyclical bite-chew mechanism for protein breakdown. Mol Cell. 1999;4(3):395–402. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80341-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu Y., Wu J., Dong Y., et al. Conformational landscape of the p28-bound human proteasome regulatory particle. Mol Cell. 2017;67(2):322–333.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dong Y., Zhang S., Wu Z., et al. Cryo-EM structures and dynamics of substrate-engaged human 26S proteasome. Nature. 2019;565(7737):49–55. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0736-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Finley D. Recognition and processing of ubiquitin-protein conjugates by the proteasome. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:477–513. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.081507.101607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seifert U., Bialy L.P., Ebstein F., et al. Immunoproteasomes preserve protein homeostasis upon interferon-induced oxidative stress. Cell. 2010;142(4):613–624. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rechsteiner M., Realini C., Ustrell V. The proteasome activator 11 S REG (PA28) and class I antigen presentation. Biochem J. 2000;345(Pt 1):1–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hill C.P., Masters E.I., Whitby F.G. The 11S regulators of 20S proteasome activity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2002;268:73–89. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-59414-4_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zwickl P., Kleinz J., Baumeister W. Critical elements in proteasome assembly. Nat Struct Biol. 1994;1(11):765–770. doi: 10.1038/nsb1194-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fenteany G., Standaert R.F., Lane W.S., Choi S., Corey E.J., Schreiber S.L. Inhibition of proteasome activities and subunit-specific amino-terminal threonine modification by lactacystin. Science. 1995;268(5211):726–731. doi: 10.1126/science.7732382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wenzel T., Baumeister W. Thermoplasma acidophilum proteasomes degrade partially unfolded and ubiquitin-associated proteins. FEBS Lett. 1993;326(1–3):215–218. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81793-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dou Q.P., Zonder J.A. Overview of proteasome inhibitor-based anti-cancer therapies: perspective on bortezomib and second generation proteasome inhibitors versus future generation inhibitors of ubiquitin-proteasome system. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2014;14(6):517–536. doi: 10.2174/1568009614666140804154511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldberg A.L., Boches F.S. Oxidized proteins in erythrocytes are rapidly degraded by the adenosine triphosphate-dependent proteolytic system. Science. 1982;215(4536):1107–1109. doi: 10.1126/science.7038874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Voges D., Zwickl P., Baumeister W. The 26S proteasome: a molecular machine designed for controlled proteolysis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:1015–1068. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wenzel T., Baumeister W. Conformational constraints in protein degradation by the 20S proteasome. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2(3):199–204. doi: 10.1038/nsb0395-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Olivares A.O., Baker T.A., Sauer R.T. Mechanical protein unfolding and degradation. Annu Rev Physiol. 2018;80:413–429. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021317-121303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Navon A., Goldberg A.L. Proteins are unfolded on the surface of the ATPase ring before transport into the proteasome. Mol Cell. 2001;8(6):1339–1349. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00407-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Whitby F.G., Masters E.I., Kramer L., et al. Structural basis for the activation of 20S proteasomes by 11S regulators. Nature. 2000;408(6808):115–120. doi: 10.1038/35040607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Benaroudj N., Zwickl P., Seemüller E., Baumeister W., Goldberg A.L. ATP hydrolysis by the proteasome regulatory complex PAN serves multiple functions in protein degradation. Mol Cell. 2003;11(1):69–78. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00775-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dubiel W., Pratt G., Ferrell K., Rechsteiner M. Purification of an 11 S regulator of the multicatalytic protease. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(31):22369–22377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McCarthy M.K., Weinberg J.B. The immunoproteasome and viral infection: a complex regulator of inflammation. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:21. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jiang T.X., Ma S., Han X., et al. Proteasome activator PA200 maintains stability of histone marks during transcription and aging. Theranostics. 2021;11(3):1458–1472. doi: 10.7150/thno.48744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hochstrasser M. Ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation. Annu Rev Genet. 1996;30:405–439. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Adams J. The development of proteasome inhibitors as anticancer drugs. Cancer Cell. 2004;5(5):417–421. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hideshima T., Richardson P., Chauhan D., et al. The proteasome inhibitor PS-341 inhibits growth, induces apoptosis, and overcomes drug resistance in human multiple myeloma cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61(7):3071–3076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.LeBlanc R., Catley L.P., Hideshima T., et al. Proteasome inhibitor PS-341 inhibits human myeloma cell growth in vivo and prolongs survival in a murine model. Cancer Res. 2002;62(17):4996–5000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Narayanan S., Cai C.Y., Assaraf Y.G., et al. Targeting the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway to overcome anti-cancer drug resistance. Drug Resist Updates. 2020;48 doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2019.100663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sun S.C. The non-canonical NF-κB pathway in immunity and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17(9):545–558. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yu H., Lin L., Zhang Z., Zhang H., Hu H. Targeting NF-κB pathway for the therapy of diseases: mechanism and clinical study. Signal Transduct Targeted Ther. 2020;5(1):209. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00312-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen Z., Hagler J., Palombella V.J., et al. Signal-induced site-specific phosphorylation targets I kappa B alpha to the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Genes Dev. 1995;9(13):1586–1597. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.13.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Scherer D.C., Brockman J.A., Chen Z., Maniatis T., Ballard D.W. Signal-induced degradation of I kappa B alpha requires site-specific ubiquitination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(24):11259–11263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Spencer E., Jiang J., Chen Z.J. Signal-induced ubiquitination of IkappaBalpha by the F-box protein Slimb/beta-TrCP. Genes Dev. 1999;13(3):284–294. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Winston J.T., Strack P., Beer-Romero P., Chu C.Y., Elledge S.J., Harper J.W. The SCFbeta-TRCP-ubiquitin ligase complex associates specifically with phosphorylated destruction motifs in IkappaBalpha and beta-catenin and stimulates IkappaBalpha ubiquitination in vitro. Genes Dev. 1999;13(3):270–283. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Orlowski R.Z., Stinchcombe T.E., Mitchell B.S., et al. Phase I trial of the proteasome inhibitor PS-341 in patients with refractory hematologic malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(22):4420–4427. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.01.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sunwoo J.B., Chen Z., Dong G., et al. Novel proteasome inhibitor PS-341 inhibits activation of nuclear factor-kappa B, cell survival, tumor growth, and angiogenesis in squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7(5):1419–1428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Oren O., Smith B.D. Eliminating cancer stem cells by targeting embryonic signaling pathways. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2017;13(1):17–23. doi: 10.1007/s12015-016-9691-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Heeg-Truesdell E., LaBonne C. Wnt signaling: a shaggy dogma tale. Curr Biol. 2006;16(2):R62–R64. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Aberle H., Bauer A., Stappert J., Kispert A., Kemler R. Beta-catenin is a target for the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. EMBO J. 1997;16(13):3797–3804. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pai S.G., Carneiro B.A., Mota J.M., et al. Wnt/beta-catenin pathway: modulating anticancer immune response. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10(1):101. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0471-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cui C., Zhou X., Zhang W., Qu Y., Ke X. Is β-catenin a druggable target for cancer therapy? Trends Biochem Sci. 2018;43(8):623–634. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang X., Wang L., Qu Y. Targeting the β-catenin signaling for cancer therapy. Pharmacol Res. 2020;160 doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Krishnamurthy N., Kurzrock R. Targeting the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in cancer: update on effectors and inhibitors. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;62:50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang J., Wang W., Zhou Y., et al. Terphenyllin suppresses orthotopic pancreatic tumor growth and prevents metastasis in mice. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:457. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liu S., Wang J., Shao T., et al. The natural agent Rhein induces β-catenin degradation and tumour growth arrest. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22(1):589–599. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhou T., Zhang A., Kuang G., et al. Baicalin inhibits the metastasis of highly aggressive breast cancer cells by reversing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition by targeting β-catenin signaling. Oncol Rep. 2017;38(6):3599–3607. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.6011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen Y., Wang X.Q., Zhang Q., et al. (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits colorectal cancer stem cells by suppressing Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Nutrients. 2017;9(6):E572. doi: 10.3390/nu9060572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vogelstein B., Lane D., Levine A.J. Surfing the p53 network. Nature. 2000;408(6810):307–310. doi: 10.1038/35042675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fridman J.S., Lowe S.W. Control of apoptosis by p53. Oncogene. 2003;22(56):9030–9040. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cahilly-Snyder L., Yang-Feng T., Francke U., George D.L. Molecular analysis and chromosomal mapping of amplified genes isolated from a transformed mouse 3T3 cell line. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1987;13(3):235–244. doi: 10.1007/BF01535205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Momand J., Zambetti G.P., Olson D.C., George D., Levine A.J. The mdm-2 oncogene product forms a complex with the p53 protein and inhibits p53-mediated transactivation. Cell. 1992;69(7):1237–1245. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90644-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Oliner J.D., Pietenpol J.A., Thiagalingam S., Gyuris J., Kinzler K.W., Vogelstein B. Oncoprotein MDM2 conceals the activation domain of tumour suppressor p53. Nature. 1993;362(6423):857–860. doi: 10.1038/362857a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhou J., Wang J., Chen C., Yuan H., Wen X., Sun H. USP7: target validation and drug discovery for cancer therapy. Med Chem. 2018;14(1):3–18. doi: 10.2174/1573406413666171020115539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Haupt Y., Maya R., Kazaz A., Oren M. Mdm2 promotes the rapid degradation of p53. Nature. 1997;387(6630):296–299. doi: 10.1038/387296a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Honda R., Tanaka H., Yasuda H. Oncoprotein MDM2 is a ubiquitin ligase E3 for tumor suppressor p53. FEBS Lett. 1997;420(1):25–27. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Oliner J.D., Saiki A.Y., Caenepeel S. The role of MDM2 amplification and overexpression in tumorigenesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016;6(6):a026336. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a026336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wade M., Li Y.C., Wahl G.M. MDM2, MDMX and p53 in oncogenesis and cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(2):83–96. doi: 10.1038/nrc3430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pei Y., Fu J., Shi Y., et al. Discovery of a potent and selective degrader for USP7. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2022;61(33) doi: 10.1002/anie.202204395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Qi S.M., Cheng G., Cheng X.D., et al. Targeting USP7-mediated deubiquitination of MDM2/MDMX-p53 pathway for cancer therapy: are we there yet? Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:233. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Eferl R., Wagner E.F. AP-1: a double-edged sword in tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(11):859–868. doi: 10.1038/nrc1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shaulian E., Karin M. AP-1 as a regulator of cell life and death. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4(5):E131–E136. doi: 10.1038/ncb0502-e131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lauricella M., Emanuele S., D'Anneo A., et al. JNK and AP-1 mediate apoptosis induced by bortezomib in HepG2 cells via FasL/caspase-8 and mitochondria-dependent pathways. Apoptosis. 2006;11(4):607–625. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-4689-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nakano T., Katsuki S., Chen M., et al. Uremic toxin indoxyl sulfate promotes proinflammatory macrophage activation via the interplay of OATP2B1 and Dll4-Notch signaling. Circulation. 2019;139(1):78–96. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.034588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Liu A. Proteostasis in the Hedgehog signaling pathway. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2019;93:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2018.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Xu J., Yu X., Martin T.C., et al. AKT degradation selectively inhibits the growth of PI3K/PTEN pathway-mutant cancers with wild-type KRAS and BRAF by destabilizing aurora kinase B. Cancer Discov. 2021;11(12):3064–3089. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Damalas A., Ben-Ze'ev A., Simcha I., et al. Excess beta-catenin promotes accumulation of transcriptionally active p53. EMBO J. 1999;18(11):3054–3063. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.11.3054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Oren M., Damalas A., Gottlieb T., et al. Regulation of p53: intricate loops and delicate balances. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;973:374–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sadot E., Geiger B., Oren M., Ben-Ze'ev A. Down-regulation of beta-catenin by activated p53. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(20):6768–6781. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.20.6768-6781.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Levina E., Oren M., Ben-Ze'ev A. Downregulation of β-catenin by p53 involves changes in the rate of β-catenin phosphorylation and Axin dynamics. Oncogene. 2004;23(25):4444–4453. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Varshavsky A. Regulated protein degradation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30(6):283–286. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ciechanover A. Intracellular protein degradation: from a vague idea thru the lysosome and the ubiquitin-proteasome system and onto human diseases and drug targeting. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1824(1):3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hershko A., Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin system. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:425–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.King R.W., Deshaies R.J., Peters J.M., Kirschner M.W. How proteolysis drives the cell cycle. Science. 1996;274(5293):1652–1659. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wang Y., Zhang T., Kwiatkowski N., et al. CDK7-dependent transcriptional addiction in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell. 2015;163(1):174–186. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yang H.W., Chung M., Kudo T., Meyer T. Competing memories of mitogen and p53 signalling control cell-cycle entry. Nature. 2017;549(7672):404–408. doi: 10.1038/nature23880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Loyer P., Trembley J.H., Katona R., Kidd V.J., Lahti J.M. Role of CDK/cyclin complexes in transcription and RNA splicing. Cell Signal. 2005;17(9):1033–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chiarle R., Budel L.M., Skolnik J., et al. Increased proteasome degradation of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27 is associated with a decreased overall survival in mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2000;95(2):619–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lloyd R.V., Erickson L.A., Jin L., et al. p27kip1: a multifunctional cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor with prognostic significance in human cancers. Am J Pathol. 1999;154(2):313–323. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65277-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ludwig H., Khayat D., Giaccone G., Facon T. Proteasome inhibition and its clinical prospects in the treatment of hematologic and solid malignancies. Cancer. 2005;104(9):1794–1807. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chen K.F., Yeh P.Y., Yeh K.H., Lu Y.S., Huang S.Y., Cheng A.L. Down-regulation of phospho-Akt is a major molecular determinant of bortezomib-induced apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68(16):6698–6707. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yang Z., Liu S., Zhu M., et al. PS341 inhibits hepatocellular and colorectal cancer cells through the FOXO3/CTNNB1 signaling pathway. Sci Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep22090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Saeki I., Terai S., Fujisawa K., et al. Bortezomib induces tumor-specific cell death and growth inhibition in hepatocellular carcinoma and improves liver fibrosis. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48(6):738–750. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0675-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Farra R., Dapas B., Baiz D., et al. Impairment of the Pin1/E2F1 axis in the anti-proliferative effect of bortezomib in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Biochimie. 2015;112:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Baiz D., Pozzato G., Dapas B., et al. Bortezomib arrests the proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma cells HepG2 and JHH6 by differentially affecting E2F1, p21 and p27 levels. Biochimie. 2009;91(3):373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Li S., Dai X., Gong K., Song K., Tai F., Shi J. PA28α/β promote breast cancer cell invasion and metastasis via down-regulation of CDK15. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1283. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Aki M., Shimbara N., Takashina M., et al. Interferon-gamma induces different subunit organizations and functional diversity of proteasomes. J Biochem. 1994;115(2):257–269. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ciechanover A. Intracellular protein degradation: from a vague idea through the lysosome and the ubiquitin-proteasome system and onto human diseases and drug targeting. Bioorg Med Chem. 2013;21(12):3400–3410. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kloetzel P.M. Antigen processing by the proteasome. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2(3):179–188. doi: 10.1038/35056572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Groettrup M., Kirk C.J., Basler M. Proteasomes in immune cells: more than peptide producers? Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(1):73–78. doi: 10.1038/nri2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ebstein F., Kloetzel P.M., Krüger E., Seifert U. Emerging roles of immunoproteasomes beyond MHC class I antigen processing. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69(15):2543–2558. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-0938-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Seliger B., Maeurer M.J., Ferrone S. Antigen-processing machinery breakdown and tumor growth. Immunol Today. 2000;21(9):455–464. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01692-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Dissemond J., Goette P., Moers J., et al. Immunoproteasome subunits LMP2 and LMP7 downregulation in primary malignant melanoma lesions: association with lack of spontaneous regression. Melanoma Res. 2003;13(4):371–377. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200308000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Evans M., Borysiewicz L.K., Evans A.S., et al. Antigen processing defects in cervical carcinomas limit the presentation of a CTL epitope from human papillomavirus 16 E6. J Immunol. 2001;167(9):5420–5428. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Fellerhoff B., Gu S., Laumbacher B., et al. The LMP7-K allele of the immunoproteasome exhibits reduced transcript stability and predicts high risk of colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71(23):7145–7154. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Heink S., Fricke B., Ludwig D., Kloetzel P.M., Krüger E. Tumor cell lines expressing the proteasome subunit isoform LMP7E1 exhibit immunoproteasome deficiency. Cancer Res. 2006;66(2):649–652. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Johnsen A., France J., Sy M.S., Harding C.V. Down-regulation of the transporter for antigen presentation, proteasome subunits, and class I major histocompatibility complex in tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 1998;58(16):3660–3667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Kimura H., Caturegli P., Takahashi M., Suzuki K. New insights into the function of the immunoproteasome in immune and nonimmune cells. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/541984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kuhn D.J., Hunsucker S.A., Chen Q., Voorhees P.M., Orlowski M., Orlowski R.Z. Targeted inhibition of the immunoproteasome is a potent strategy against models of multiple myeloma that overcomes resistance to conventional drugs and nonspecific proteasome inhibitors. Blood. 2009;113(19):4667–4676. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-171637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kuhn D.J., Orlowski R.Z. The immunoproteasome as a target in hematologic malignancies. Semin Hematol. 2012;49(3):258–262. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Koerner J., Brunner T., Groettrup M. Inhibition and deficiency of the immunoproteasome subunit LMP7 suppress the development and progression of colorectal carcinoma in mice. Oncotarget. 2017;8(31):50873–50888. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Kimura H.J., Chen C.Y., Tzou S.C., et al. Immunoproteasome overexpression underlies the pathogenesis of thyroid oncocytes and primary hypothyroidism: studies in humans and mice. PLoS One. 2009;4(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Singh A.V., Bandi M., Aujay M.A., et al. PR-924, a selective inhibitor of the immunoproteasome subunit LMP-7, blocks multiple myeloma cell growth both in vitro and in vivo. Br J Haematol. 2011;152(2):155–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08491.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Tripathi S.C., Peters H.L., Taguchi A., et al. Immunoproteasome deficiency is a feature of non-small cell lung cancer with a mesenchymal phenotype and is associated with a poor outcome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(11):E1555–E1564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521812113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Tomaru U., Ishizu A., Murata S., et al. Exclusive expression of proteasome subunit{beta}5t in the human thymic cortex. Blood. 2009;113(21):5186–5191. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-187633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Ripen A.M., Nitta T., Murata S., Tanaka K., Takahama Y. Ontogeny of thymic cortical epithelial cells expressing the thymoproteasome subunit β5t. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41(5):1278–1287. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Ohigashi I., Zuklys S., Sakata M., et al. Aire-expressing thymic medullary epithelial cells originate from β5t-expressing progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(24):9885–9890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301799110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Florea B.I., Verdoes M., Li N., et al. Activity-based profiling reveals reactivity of the murine thymoproteasome-specific subunit β5t. Chem Biol. 2010;17(8):795–801. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Sasaki K., Takada K., Ohte Y., et al. Thymoproteasomes produce unique peptide motifs for positive selection of CD8+ T cells. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7484. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Sutoh Y., Kondo M., Ohta Y., et al. Comparative genomic analysis of the proteasome β5t subunit gene: implications for the origin and evolution of thymoproteasomes. Immunogenetics. 2012;64(1):49–58. doi: 10.1007/s00251-011-0558-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Nitta T., Murata S., Sasaki K., et al. Thymoproteasome shapes immunocompetent repertoire of CD8+ T cells. Immunity. 2010;32(1):29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Murata S., Takahama Y., Tanaka K. Thymoproteasome: probable role in generating positively selecting peptides. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20(2):192–196. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Takahama Y., Nitta T., Mat Ripen A., Nitta S., Murata S., Tanaka K. Role of thymic cortex-specific self-peptides in positive selection of T cells. Semin Immunol. 2010;22(5):287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Klein L., Kyewski B., Allen P.M., Hogquist K.A. Positive and negative selection of the T cell repertoire: what thymocytes see (and don't see) Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(6):377–391. doi: 10.1038/nri3667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Kincaid E.Z., Murata S., Tanaka K., Rock K.L. Specialized proteasome subunits have an essential role in the thymic selection of CD8+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2016;17(8):938–945. doi: 10.1038/ni.3480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Murata S., Takahama Y., Kasahara M., Tanaka K. The immunoproteasome and thymoproteasome: functions, evolution and human disease. Nat Immunol. 2018;19(9):923–931. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0186-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Takahama Y., Ohigashi I., Murata S., Tanaka K. Thymoproteasome and peptidic self. Immunogenetics. 2019;71(3):217–221. doi: 10.1007/s00251-018-1081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Kourilsky P., Claverie J.M. The peptidic self model: a hypothesis on the molecular nature of the immunological self. Ann Inst Pasteur Immunol. 1986;137D(1):3–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Tomaru U., Konno S., Miyajima S., et al. Restricted expression of the thymoproteasome is required for thymic selection and peripheral homeostasis of CD8+ T cells. Cell Rep. 2019;26(3):639–651.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.12.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Starr T.K., Jameson S.C., Hogquist K.A. Positive and negative selection of T cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:139–176. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Takahama Y., Tanaka K., Murata S. Modest cortex and promiscuous medulla for thymic repertoire formation. Trends Immunol. 2008;29(6):251–255. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]