Recently in Gut, several reviews and reports have highlighted hypomorphic (dysfunctional) variants of the sucrase-isomaltase (SI) gene in relation to increased risk of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), particularly the diarrhoea-predominant type (IBS-D).1–4 Similar to congenital (rare recessive) and acquired forms of SI deficiency, impaired SI enzymatic activity is expected to lead to colonic accumulation of undigested disaccharides, thus triggering IBS manifestations via gut microbiota fermentation, gas production and osmotic diarrhoea. Reduced efficacy of a diet low in FODMAPs (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols) is also observed for SI hypomorphic IBS-D carriers,4 as this intervention may be suboptimal for individuals with possible defects in the digestion of carbohydrates other than FODMAPs (the lowFODMAP diet does not specifically restrict sucrose and starch, the substrates of SI disaccharidase activity). These results hold strong potential for personalising therapeutic (dietary) interventions in subgroups of IBS patients, though the eventual relevance of SI genotype has not been tested in the optimal dietary context, that is when patients are challenged with reducing the amount of SI substrates, like in a sucrose and starch-restricted diet (SSRD).

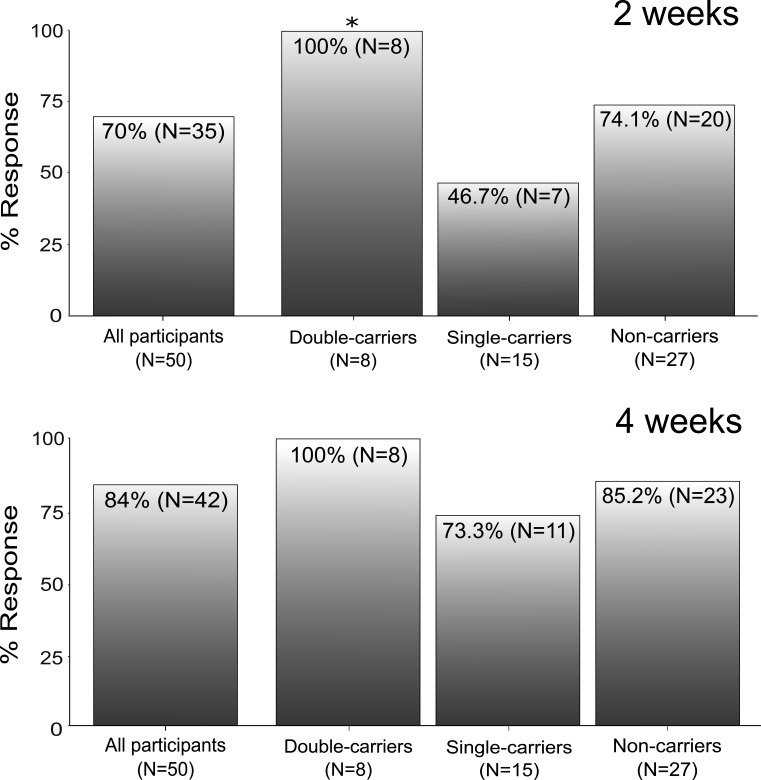

Aiming to generate specific hypothesis that may be tested in future trials, we conducted a pilot investigation and retrospectively evaluated data from two previous SSRD studies from Sweden and Spain5 6: we assessed the relation between SI genotype and symptom amelioration in a total of 50 IBS-D patients of European ancestry, defined according to consensus gold standard Rome IV Criteria (table 1).7 High-quality SI targeted sequencing data were obtained for all subjects using an Illlumina AmpliSeq DNA assay with optimal coverage of the region of interest (>99% 30 × coverage of 48 SI exons). To identify hypomorphic variants, the functional relevance of SI non-synonymous (coding) changes was computationally predicted as previously described.4 8–10 Seven SI hypomorphic variants were identified, namely Val15Phe (dbSNP database https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp entry rs9290264), Pro348Leu (rs77546399), Val371Met (rs138434001), Ile799Val (rs150246328), Tyr975His (rs146785675), Gly1073Asp (rs121912616) and Arg1367Gly (rs143388292), most of which already described in previous studies.4 8–10 Based on available genotype and functional data, IBS-D patients were stratified into SI hypomorphic variant double-carrier, single-carrier and non-carrier groups, and cumulative analyses of SI genotype were performed, as previously done,4 8–10 in relation to SSRD response. A valid hypothesis is that SI carriers, especially double-carriers, would benefit more from a diet (SSRD) that restricts dietary intake of carbohydrates that may be inefficiently digested when SI disaccharidase activity is reduced (as in SI carriers). A logistic regression based on sex-adjusted and age-adjusted additive genetic model did not disclose any direct correlation between SI genotype and SSRD response (not shown). However, as shown in figure 1 where SSRD response after 2 and 4 weeks are reported, all SI hypomorphic double-carriers consistently improved with the diet at both timepoints, while the response in other SI genotype groups varied. Despite the small sample size, this gave rise to a significant p value when SSRD results for IBS-D double-carriers were specifically compared with the remainder of the cohort in a Fisher’s exact test (p<0.05). Hence, while other mechanisms are certainly at play (also non-carriers respond to SSRD treatment), our results suggest that SI hypomorphic variants may affect the response to carbohydrate-focused diets.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of the patients included in this study

| Characteristics* | Sweden | Spain | Total† |

| IBS-D patients | 20 | 30 | 50 |

| Females (%) | 12 (60.0) | 19 (63.3) | 31 (62.0) |

| Age, mean±SD | 48.9±13.4 | 42.8±13.9 | 45.2±13.9 |

| IBS-SSS (mean±SD) at baseline | 282.4±69.3 | 293.8±71.1 | 289.2±69.9 |

| IBS-SSS (mean±SD) at 2 weeks | 194.1±100.3 | 183.8±89.7 | 187.9±93.2 |

| IBS-SSS (mean±SD) at 4 weeks | 157.3±93.2 | 142.5±99.0 | 148.4±94.1 |

| Responders at 2 weeks (%)‡ | 15 (75.0) | 20 (66.7) | 35 (70.0) |

| Responders at 4 weeks (%)‡ | 17 (85.0) | 25 (83.3) | 42 (84.0) |

| SI hypomorphic genotype (0/1/2)§ | 12/4/4 | 15/11/4 | 27/15/8 |

*Demographic, IBS symptom severity scores (IBS-SSS) and SSRD response during the observation period, at 2 and 4 weeks (standard deviation (SD)).

†Swedish and Spanish patients did not significantly differ for age, sex, IBS-SSS scores or SSRD response rates.

‡A positive SSRD response was defined as a drop of 50 IBS-SSS points, compared with baseline.

§SI hypomorphic genotype (non-carriers/single-carriers/double-carriers).

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; SI, sucrase-isomaltase; SSRD, sucrose and starch-restricted diet.

Figure 1.

Response to SSRD in IBS-D patients, stratified according to SI hypomorphic genotype (double-carrier, single-carrier and non-carrier groups), at 2 weeks (top) and 4 weeks (bottom). *p=0.043 for double-carriers versus other groups (one-tailed Fisher’s exact test). IBS-D, irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhoea; SI, sucrase-isomaltase; SSRD, sucrose and starch-restricted diet.

Altogether from this and previous studies,3 4 8–10 compelling evidence is accumulating for a role of SI variants in IBS, which holds potential for the management of IBS-D patients based on their genotype. In line with this and previous observations, a strategy may be envisaged to treat SI hypomorphic (double) carriers with SSRD, while non-carriers may actually benefit more from a low-FODMAP diet. Our results provide rationale for testing this hypothesis in future trials.

Footnotes

Twitter: @ZamfirTaranu, @damato_mauro

B-SL and DMH contributed equally.

Contributors: MD'A, LB, HN and BO study design and supervision; B-SL, DH, AH, KG-E, UE, LG, GM, CN, RG, OO, TZ, CE-B, IB, FB, SR, AF, LB and BO data acquisition, patients characterisation; AZT, B-SL, KG-E and GM statistical and computational analyses; AZT, B-SL, DH, LB, HN, BO and MD'A data analysis and interpretation; MD'A obtained funding and technical support; AZT and MD'A drafted the manuscript, with input and critical revision from all other authors. All authors approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Funding: Funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 (PID2020-113625RB-I00).

Competing interests: MD'A has received unrestricted research grants and consulting fees from QOL Medical LLC. HN has received unrestricted research grants from QOL Medical.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The Swedish study protocol was approved by the Ethical Review Board of Lund University (2017/171, 2017/192), and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03306381). The Spanish study protocol was approved by the Local Ethics Committee (Comité de Ética del Área Sanitaria de Gipuzkoa, code: BUJ-NUT-2019-01). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. Camilleri M, Boeckxstaens G. Irritable bowel syndrome: treatment based on pathophysiology and biomarkers. Gut 2023;72:590–9. 10.1136/gutjnl-2022-328515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gibson PR, Halmos EP. The FODMAP diet: more than just a symptomatic therapy? Gut 2022;71:1693–4. 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-326284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Foley A, Halmos EP, Husein DM, et al. Adult sucrase-isomaltase deficiency masquerading as IBS. Gut 2022;71:1237–8. 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-326153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zheng T, Eswaran S, Photenhauer AL, et al. Reduced efficacy of low fodmaps diet in patients with IBS-D carrying sucrase-isomaltase (Si) hypomorphic variants. Gut 2020;69:397–8. 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-318036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nilholm C, Roth B, Ohlsson B. A dietary intervention with reduction of starch and sucrose leads to reduced gastrointestinal and extra-intestinal symptoms in IBS patients. Nutrients 2019;11:1–15. 10.3390/nu11071662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gayosoa L, Garcia-Etxebarria K, Arzalluse T, et al. The effect of starch- and sucrose-reduced diet accompanied by nutritional and culinary recommendations on the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome patients with diarrhea [in press]. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Drossman DA, Tack J. Rome foundation clinical diagnostic criteria for disorders of gut-brain interaction. Gastroenterology 2022;162:675–9. 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Henström M, Diekmann L, Bonfiglio F, et al. Functional variants in the sucrase-isomaltase gene associate with increased risk of irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 2018;67:263–70. 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Garcia-Etxebarria K, Zheng T, Bonfiglio F, et al. Increased prevalence of rare sucrase-isomaltase pathogenic variants in irritable bowel syndrome patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;16:1673–6. 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.01.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zheng T, Camargo-Tavares L, Bonfiglio F, et al. Rare hypomorphic sucrase isomaltase variants in relation to irritable bowel syndrome risk in UK biobank. Gastroenterology 2021;161:1712–4. 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.06.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]