Abstract

Background

This study examines the association between the Tobacconomics cigarette tax scores and cigarette consumption in 97 countries during the period of 2014–2020.

Methods

Data on countries’ retail cigarette sales and overall cigarette tax scores from 2014 to 2020 are drawn from the proprietary Euromonitor International database and the Tobacconomics Cigarette Tax Scorecard (second edition). Information on countries’ tobacco control environments and demographic characteristics is from the relevant years’ WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, and the World Bank’s World Development Indicators database. Ordinary least squares regressions are employed to examine the link between countries’ overall cigarette tax scores and cigarette consumption. All regressions control for countries’ tobacco control environments, countries’ demographic characteristics, year indicators and country fixed effects.

Results

Each unit increase in the overall cigarette tax scores is significantly associated with a reduction of 9% in countries’ per-capita cigarette consumption during 2014–2020. The reduction is more pronounced in low and middle-income countries (9%) than in high-income countries (6%). The modest improvement in scores from 2014 to 2020 is associated with a reduction of 3.27% in consumption, while consumption could have been reduced by 20.74% had countries implemented optimal tax policies that would earn the highest score of 5.

Conclusions

Our results provide evidence on the association between higher cigarette tax scores and lower cigarette consumption. To reduce tobacco consumption, governments must strive to implement all four components in the Cigarette Tax Scorecard at the highest level.

Keywords: taxation, public policy, price

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Growing evidence indicates the effectiveness of each cigarette tax component (i.e., cigarette price, tax share, and tax structure) on reducing cigarette smoking.

The study is the first to examine the effects of comprehensive cigarette tax policies—measured by the Tobacconomics overall cigarette tax scores—on actual smoking behaviours across countries.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

The study provides evidence on the association between higher cigarette tax scores and lower cigarette consumption, in which the association is more pronounced in low and middle-income countries than in high-income countries.

This association adds to the efficacy of the Tobacconomics Cigarette Tax Scorecard in evaluating cigarette taxes across countries.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

To reduce tobacco consumption, governments must strive to implement all four components in the Cigarette Tax Scorecard at the highest level by implementing tax rates that significantly increase absolute cigarette prices, reducing cigarette affordability, increasing tax shares of cigarette prices, and applying appropriate tax structures to further reduce tobacco use and its associated burdens.

Introduction

Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable death worldwide, with more than 8 million deaths each year.1 Most of these preventable deaths occur in low and middle-income countries (LMICs). Research shows that a significant tobacco tax increase that leads to higher prices is the most effective and cost-effective tobacco control policy tool for reducing tobacco use.2 3 However, many countries—particularly LMICs—have been slow to adopt these policies, or they do not implement these policies effectively.

In 2020, to facilitate policy makers’ comparative evaluation of their country’s current cigarette tax policies, the Tobacconomics team released the first edition of the Tobacconomics Cigarette Tax Scorecard assessing countries’ cigarette tax policy performance on a 5-point scale. The Scorecard synthesises established best practices, focusing on four key components: (1) cigarette price, (2) changes in the affordability of cigarettes over time, (3) the share of taxes in retail cigarette prices, and (4) cigarette tax structures. The Scorecard shows that most countries did not tax cigarettes effectively during 2014–2018, with nearly half of them scoring less than 2 out of the highest score of 5, and with limited improvement over the previous 6 years.4 In November 2021, the Tobacconomics team released the second edition of the Scorecard, which shows that some countries improved their tobacco tax systems during 2014–2020, but the improvements were insufficient to significantly decrease tobacco use.5

Previous studies have examined the effects of each cigarette tax component on cigarette smoking. Higher cigarette prices have been shown to decrease overall tobacco consumption,6–10 cause current smokers to quit11–14 and prevent young people from starting smoking.8 15–17 Similarly, studies have shown that as cigarettes become less affordable, consumption decreases.9 18–20 Affordability is often measured as relative income price (RIP)—the percentage of per-capita income required to purchase 100 packs of cigarettes. RIP counterintuitively increases as affordability decreases. A 1% increase in RIP is estimated to reduce cigarette consumption by 0.49%–0.57%.18 A higher share of taxes in retail cigarette prices also generally indicates higher retail cigarette prices and thus reductions in cigarette consumption.21 More complicated tax structures are significantly associated with higher cigarette consumption. This is typically due to higher price variation and opportunities for smokers to substitute with cheaper cigarettes. Changing from a specific to an ad valorem structure is associated with an increase of 6%–11% in cigarette consumption, and changing from a uniform to a tiered structure is associated with an increase of 34%–65% in cigarette consumption.22

Despite growing evidence on the effects of each cigarette tax component on cigarette smoking, little is known about the effects of all four cigarette tax components on actual smoking behaviours, especially across countries. To address this research gap, this study examines the relationship between a comprehensive set of cigarette tax policies—measured by the Tobacconomics overall cigarette tax scores—and cigarette consumption and tests the hypothesis that countries with higher overall cigarette tax scores are more likely to experience lower cigarette consumption during 2014–2020, controlling for the wider tobacco control environment in each country. Using data from the second edition of the Tobacconomics Cigarette Tax Scorecard, we use regression analysis to evaluate this relationship while controlling for each country’s tobacco control environment, demographic characteristics, and potential observed and unobserved time-specific and country-specific factors that may affect cigarette consumption.

Methods

Data

Tobacconomics cigarette tax scores

Data on countries’ overall cigarette tax scores for 2014, 2016, 2018, and 2020 are drawn from the second edition of the Tobacconomics Cigarette Tax Scorecard .5 The Scorecard (second edition) assesses cigarette tax policy performance in 160 countries on a 5-point scale based on four key components of cigarette taxation: (1) cigarette price, (2) changes in cigarette affordability, (3) tax share of price, and (4) tax structure. The Scorecard measures countries’ performances on each of the four components on a scale of 0–5, with a score of 5 indicating the strongest performance. The composite overall cigarette tax scores are then constructed as the average of all four component scores and could range from 0, for countries with a score of 0 on all four components, to 5, for countries with a score of 5 on all four components.5 The information on how each component score is calculated is available in the online supplemental appendix.

tc-2022-057486supp001.pdf (129.1KB, pdf)

To examine the link between cigarette tax scores and cigarette consumption, we use countries’ overall cigarette tax scores instead of all four component scores. Because the four component scores are highly collinear, including all four of them in the analyses would likely underestimate the effectiveness of these scores in reducing cigarette consumption. In addition, by using overall cigarette tax scores, we use the greatest possible variation in scores over time to assess the link between the scores and cigarette consumption.

Euromonitor International retail cigarette sales

The Euromonitor International cigarette and tobacco country reports provide information on countries’ retail sales of cigarettes defined as duty-paid, machine-manufactured white-stick products, including internet sales for 2014–2020.23 This definition of cigarettes is designed to exclude the volume of non-machine-manufactured products such as bidis/beedis and other smoking products made with tobacco that do not resemble cigarettes as recognised in the USA or Europe or are not machine manufactured.23 Retail cigarette sales are used as a proxy of cigarette consumption. Thus, annual per-capita cigarette consumption for each year in a country is derived as the ratio of the country’s total retail cigarette sales to the size of the population aged 15 and older.

Countries’ tobacco control environments

Data on countries’ tobacco control environments—measured by four elements (POWE) of the MPOWER scores for years 2014, 2016, 2018 and 2020—are from the WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic for the years 2015, 2017, 2019 and 2021.1 24–26 The MPOWER measures were introduced by WHO in 2008 to assist party countries with implementation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC). The MPOWER package includes six measures: monitoring tobacco use and prevention policies (M); protecting people from tobacco smoke (P); offering help to quit using tobacco (O); warning people about the dangers of tobacco use (W); enforcing bans on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship (E); and raising taxes on tobacco products (R). The information on how each MPOWER measure is constructed is shown in the online supplemental appendix. These measures have been shown to be effective in reducing smoking12 27 28 and provide guidelines for countries as to where more action is needed.24

For the POWE measure, the values range from 1 to 5. A score of 1 demonstrates no known or recent data or data that are not both recent and representative of the national population. A score of 2–5 indicates the lowest to the highest level of policy implementation. Since the M measure for monitoring is not related to a specific intervention, and the Tobacconomics cigarette tax scores already measure the performance of tax policies including the R measure for tax increases, M and R scores are excluded from the analyses. The composite POWE scores are then constructed as the sum of each POWE score for each country and survey year and included in the analyses. The composite POWE scores could range from a low score of 4 to a high score of 20.

Countries’ demographic information

The information on countries’ demographic characteristics—such as gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, percentage of the total population aged 15–64 and percentage of the total population aged 65 and older—is gathered from the World Bank’s (WB) World Development Indicators database.29 We control for GDP per capita and purchasing power parity (PPP) (constant 2017 international dollars) in the analyses. GDP per capita in PPP is derived as GDP converted to international dollars using PPP rates.29 We also construct a high-income country (HIC) dummy that classifies countries as high income based on the WB classification for each survey year.

To compile the final analytical sample, we merge all the data using year and country identifiers. The final sample includes countries that have at least two or three complete data of countries’ retail cigarette sales and overall cigarette tax scores. The final sample includes 97 countries. Due to seven missing values of overall cigarette tax scores for a few countries in certain years, our final sample includes 381 country-year observations for years 2014, 2016, 2018, and 2020. Approximately 44% of countries in the sample are HICs.

Statistical analyses

Main analyses

To allow for the relationship between countries’ overall cigarette tax scores and cigarette consumption to change proportionally, we use log of per-capita cigarette consumption as the main outcome of the analyses. We use ordinary least squares regressions to examine the association between countries’ overall cigarette tax scores and cigarette consumption. All regressions control for countries’ tobacco control environment (POWE), country-level GDP per capita, percentage of the population aged 15–64, percentage of the population aged 65 and older, year indicators, and country fixed effects. The full regression model is shown in the online supplemental appendix. By including both year and country indicators in the regressions, we control for potential observed and unobserved time-specific and country-specific factors that may affect cigarette consumption. Standard errors (SEs) are clustered at the country level to adjust for intertemporal correlations. All analyses are conducted in Stata V.15.0.

Simulations

Using the estimated coefficients in the main analyses, we estimate the reduction in consumption attributable to the score increases from 2014 to 2020, as well as the additional reduction if all countries had increased their overall scores to 5 by 2020. Specifically, we first estimate the main regression analyses and use the Stata command ‘predict’ to estimate the average consumption in 2020 under the three scenarios: (1) all countries have their actual scores from 2014 in 2020, (2) all countries have their actual scores from 2020 in 2020, and (3) all countries have a score of 5 in 2020. The percent reduction in consumption attributable to the score increases from 2014 to 2020 is calculated as the ratio of the difference between the estimated average cigarette consumption in 2020—in the second scenario and the first scenario—and the estimated average cigarette consumption in 2020 in the first scenario. Similarly, the percent reduction in consumption if all countries had increased their overall scores to 5 by 2020 is calculated as the ratio of the difference between the estimated average cigarette consumption in 2020—in the third scenario and the first scenario—and the estimated average cigarette consumption in 2020 in the first scenario.

Sensitivity analyses

Since it may take a year or longer for policies (scores) to have measurable effects on cigarette consumption, we regress the current (time=t) cigarette consumption on one lagged period (time=t-1) of countries’ overall cigarette tax scores to further examine the link between the scores and cigarette consumption. Due to a 2-year gap between the releases of the WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic that are used to construct the Tobacconomics cigarette tax scores, t-1 represents a 2-year difference.

To examine the robustness of our results, we also conduct the following sensitivity analyses. First, instead of controlling for the composite POWE score, we control for each POWE measure in the analyses. We are aware of potential problems with multicollinearity in the main regressions. To accommodate for that, we estimate the main regressions with and without the dummy variable for HICs. To check for multicollinearity, we further calculate the variance inflation factor (VIF). Specifically, we regress the overall scores on all other covariates and estimate the VIF using the formula: VIF=1/(1−R2).

Results

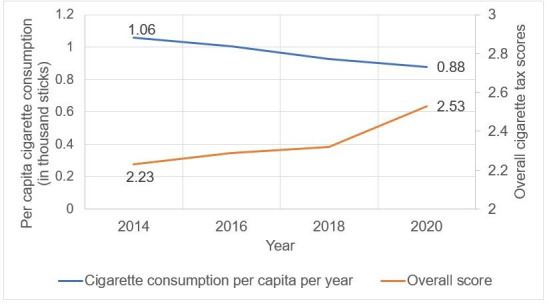

Figure 1 shows changes over time in countries’ overall cigarette tax scores and per-capita cigarette consumption during 2014–2020. While countries’ overall cigarette tax scores increased from 2.23 in 2014 to 2.53 in 2020, countries’ per-capita cigarette consumption decreased from more than 1060 cigarette sticks in 2014 to 880 cigarette sticks in 2020.

Figure 1.

Countries’ overall cigarette tax scores and per-capita cigarette consumption, 2014–2020.

Table 1 presents the summary statistics of the analytical sample. On average, the per-capita cigarette consumption was approximately 970 cigarette sticks per year. The overall cigarette tax score was 2.34—just less than half of the highest score of 5, indicating ample room for improvement. The average score of POWE was 15.60 out of the highest score of 20. The lowest score of each POWE measure is 2. The average GDP per capita was approximately US$25 800. The average percentages of the population aged 15–64 and 65 and older were 65.38% and 11.13%, respectively.

Table 1.

Summary statistics

| Variable | Mean | SD |

| Per-capita cigarette consumption (in thousand sticks) | 0.97 | 0.67 |

| Per-capita cigarette consumption (in thousand sticks)—HICs | 1.10 | 0.46 |

| Per-capita cigarette consumption (in thousand sticks)—LMICs | 0.88 | 0.77 |

| Overall cigarette tax score | 2.34 | 1.17 |

| Overall cigarette tax score—HICs | 3.00 | 0.93 |

| Overall cigarette tax score—LMICs | 1.87 | 1.09 |

| GDP per capita (in $10 000) | 2.58 | 2.04 |

| POWE score | 15.60 | 2.37 |

| % population aged 15–64 | 65.38 | 5.37 |

| % population aged 65 and older | 11.13 | 6.60 |

| Observations (n) | 381 | |

| Countries (n) | 97 | |

GDP, gross domestic product; HICs, high-income countries; LMICs, low and middle-income countries.

Table 2 shows the association between countries’ overall cigarette tax scores and cigarette consumption. The estimates suggest that a unit increase—one full point on the Scorecard—in countries’ overall cigarette tax scores was significantly associated with a reduction of 9% in countries’ per-capita cigarette consumption. The reduction was more pronounced in LMICs than in HICs. Specifically, a unit increase in overall cigarette tax scores was significantly associated with a reduction of 6% in per-capita cigarette consumption in HICs, while a similar increase was significantly associated with a 9% reduction in per-capita cigarette consumption in LMICs. Online supplemental appendix table A1 shows a fuller set of results with estimates of other controls including POWE, HIC dummy, and countries’ demographic characteristics.

Table 2.

The link between countries’ overall cigarette tax scores and cigarette consumption, 2014–2020

| Outcome | Log (cigarette consumption) | ||

| Sample | Whole sample | HICs | LMICs |

| Overall cigarette tax score | −0.09*** | −0.06*** | −0.09** |

| SE | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Year indicators | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country indicators | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Mean (consumption in thousand sticks) | 0.97 | 1.10 | 0.88 |

| Mean (overall cigarette tax score) | 2.34 | 3.00 | 1.87 |

| Observations (n) | 381 | 158 | 223 |

| Countries (n) | 97 | 43 | 58 |

+p< 0.10; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001. All regressions control for POWE scores, country-level gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, percentage of the population aged 15–64, percentage of the population aged 65 and older, year fixed effects, and country fixed effects. Standard errors (SEs) were clustered at the country level.

HICs, high-income countries; LMICs, low and middle-income countries.

Table 3 presents the simulation results that predict the countries’ per-capita cigarette consumption under different scenarios, along with the calculated percent reduction. As table 3 indicates, the modest improvement in scores from 2014 to 2020 is associated with a reduction of 3.27% in consumption, while consumption could have been reduced by 20.74% if countries had implemented optimal tax policies that would earn the highest score of 5. Consumption could have been reduced by 11.11% if HICs had implemented optimal tax policies that would earn the highest score of 5. If LMICs had implemented optimal tax policies at the highest level, they would experience a reduction of 28.05% in cigarette consumption. Online supplemental appendix table A2 shows the predicted percent reductions in cigarette consumption if all countries had increased their scores from 0 in 2014 to 5 in 2020.

Table 3.

Simulation results—reduction in cigarette consumption, 2014–2020

| A. Reduction in cigarette consumption attributable to score increases from 2014 to 2020 | |||

| Scenario | Actual scores in 2014 | Actual scores in 2020 | % reduction |

| Cigarette consumption in 2020 (in thousand sticks)—whole sample | 0.89 | 0.86 | −3.27 |

| B. Reduction in cigarette consumption if all countries had increased their scores to 5 by 2020 | |||

| Scenario | Actual scores in 2014 | All 5 in 2020 | % reduction |

| Cigarette consumption in 2020 (in thousand sticks)—whole sample | 0.89 | 0.70 | −20.74 |

| Cigarette consumption in 2020 (in thousand sticks)—HICs | 0.99 | 0.88 | −11.11 |

| Cigarette consumption in 2020 (in thousand sticks)—LMICs | 0.82 | 0.59 | −28.05 |

Countries’ average actual overall score in 2014 is 2.23, while countries’ average actual overall score in 2020 is 2.53. The average actual overall scores in 2014 are 2.98 for HICs and 1.68 for LMICs. The average actual overall scores in 2020 are 3.21 for HICs and 2.10 for LMICs. The percent reduction is calculated as the ratio of the difference in cigarette consumption between 2020 and 2014 to cigarette consumption in 2014.

HICs, high-income countries; LMICs, low and middle-income countries.

Results of sensitivity analyses suggest the robustness of our findings. Online supplemental appendix table A3 shows the link between the past overall cigarette tax scores at time (t-1) and current cigarette consumption at time (t) during 2016–2020. The estimates suggest that countries with higher past overall cigarette tax scores experienced significant reductions in current cigarette consumption (p<0.05). Online supplemental appendix table A4 shows that our estimates are robust to whether we control for the composite POWE score or each POWE measure and whether we include HIC dummy. Our VIF number is 6.68, which is smaller than 10. As a rule of thumb, a VIF above 10 indicates serious multicollinearity that needs to be corrected.30 Thus, multicollinearity is not a significant issue in this context.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, our measure of cigarette consumption captures only legal retail cigarette sales and excludes the illicit sales. Due to the lack of reliable illicit trade data, we could not account for illicit cigarette sales in our analyses. Although Euromonitor International has data on sales of illicit cigarettes, the illicit trade estimates from Euromonitor International are not reliable, with discrepancies across editions.31 32 Thus, we do not include sales of illicit cigarettes in our measure. Due to the lack of reliable, consistent and comparable data of roll your own (RYO) cigarettes over time, we could not account for RYO cigarettes in our models. Given the lack of comprehensive data on the taxation of other tobacco products, the Tobacconomics Cigarette Tax Scorecard mainly focuses on cigarette taxation. To the extent that taxes and prices on other non-cigarette products (i.e., bidis, smokeless tobacco and waterpipe tobacco) are low, relative to cigarette taxes and prices, there will be opportunities for substitution to the relatively cheaper products. If smokers switch from licit to illicit cigarettes and/or to other close substitutes, the actual reductions in cigarette consumption that are associated with increases in countries’ overall cigarette tax scores may be lower than our estimates.

In this study, we use Euromonitor International as the data source for retail cigarette sales. However, Euromonitor International now accepts funding from tobacco industry and tobacco industry entities to generate ‘Smoke-Free Index’ and examine illicit trade.32 Although we do not use illicit trade estimates from Euromonitor International in our analyses, the data and the results of this study should be viewed with caution. Second, our results may be sensitive to which countries are included in the analytical samples. Globally, there were 58 HICs (29.74%) and 137 LMICs (70.26%) in 2020,29 but our sample contains a higher proportion of HICs (44%). Our sample also includes a greater share of countries with higher performance on both cigarette tax scores and POWE scores. Thus, our results on the association between countries’ overall cigarette tax scores and cigarette consumption may not generalise to the full sample of countries.

Third, cigarette consumption is a stock value of both smoking participation and smoking intensity. Using the aggregate data of overall cigarette tax scores and cigarette consumption at the national level does not allow us to examine differential effects of cigarette tax policies on smoking participation and smoking intensity, nor the effects of those policies on different subpopulations of interest. Thus, future research may benefit from using longitudinal individual-level data to investigate the differential effects of cigarette tax policies on those outcomes and subpopulations.

Fourth, the Tobacconomics overall cigarette tax scores are constructed as the average of the four tax components, implying that each of the four tax component scores has equal weight. It is possible that some tax components are more effective than other measures in reducing smoking and should be assigned greater weight. Future research should further investigate the effects of those tax components with different assigned weights. Despite those limitations, our results are robust to different sensitivity analyses and are consistent with the findings of previous studies.

Discussions and conclusions

This study examines the link between the Tobacconomics cigarette tax scores and countries’ cigarette consumption and documents a significant association between higher overall cigarette tax scores and reduced cigarette consumption. Specifically, a unit increase in overall cigarette tax scores is significantly associated with a reduction of 9% in countries’ per-capita cigarette consumption. Our results suggest that the association between higher cigarette tax scores and lower cigarette consumption was more pronounced in LMICs than in HICs. A unit increase in cigarette tax scores was significantly associated with a reduction of 9% in cigarette consumption in LMICs and a reduction of 6% in cigarette consumption in HICs. Online supplemental appendix table A5 shows the association between four component scores and cigarette consumption and demonstrates that overall cigarette tax scores are better at capturing the effectiveness of comprehensive tobacco taxation policies.

Our simulation results suggest that the modest improvement in scores from 2014 to 2020 is associated with a reduction of 3.27% in consumption, while consumption could have been reduced by 20.74% had countries implemented optimal tax policies that would earn the highest score of 5. Our results further suggest that consumption could have been reduced by 11.11% if HICs had implemented optimal tax policies that would earn the highest score of 5. If LMICs had implemented optimal tax policies at the highest level, they would experience a reduction of 28.05% in cigarette consumption. Our results are in line with the findings of previous studies that document the effectiveness of comprehensive tobacco control policies in reducing smoking12 27 28 and larger effects of tobacco control policies (ie, prices) on cigarette smoking in LMICs.33–35 While a 10% increase in cigarette prices was estimated to decrease cigarette smoking by 2.50%–5%, with an average of 4%, in HICs, a similar increase would reduce cigarette smoking by 2%–8%, with an average of 5%, in LMICs.33

Our study is the first to examine the effects of comprehensive cigarette tax policies—measured by the Tobacconomics overall cigarette tax scores—on actual smoking behaviours across countries. Our results indicate that higher overall cigarette tax scores were significantly associated with reduced cigarette consumption, and that the reduction was more pronounced in LMICs than in HICs. Our results are in line with recommendations on strengthening countries’ cigarette tax systems from the WHO FCTC Article 6 guidelines, the WHO Technical Manual on Tobacco Tax Policy and Administration, and the WB Tobacco Tax Reform and Curbing the Epidemic reports. Our results suggest that countries—particularly LMICs—should strive to implement all four components in the Cigarette Tax Scorecard at the highest level by implementing tax rates that significantly increase absolute cigarette prices, reducing cigarette affordability, increasing the tax share of cigarette prices and applying appropriate tax structures to further reduce tobacco use and its associated burdens.

Footnotes

Twitter: @caosomatik, @erikadayle

Contributors: AN conducted the analyses and wrote the first draft. JD, CMG-L, ES and FJC provided inputs on the draft. All authors contributed to and agreed on the final version of the manuscript. AN is responsible for the overall content as a guarantor.

Funding: This study was supported by Bloomberg Philanthropies.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this study cannot be attributed to, nor can they be considered to represent, the views of UIC, the Institute for Health Research and Policy or Bloomberg Philanthropies.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. Except for data from Euromonitor International, data used in this study are publicly available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1. World Health Organization . Who report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2021, 2021. Available: https://www.who.int/teams/health-promotion/tobacco-control/global-tobacco-report-2021 [Accessed 15 Aug 2021].

- 2. National Cancer Institute & World Health Organization . The economics of tobacco and tobacco control. In: National cancer Institute tobacco control monograph 21 and NIH Publication No. 16- CA-8029A. Bethesda, MDGeneva, CH: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer InstituteWorld Health Organization, 2016. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/tcrb/monographs/21/ [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jha P. Avoidable global cancer deaths and total deaths from smoking. Nat Rev Cancer 2009;9:655–64. 10.1038/nrc2703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chaloupka FJ, Drope J, Siu E, et al. Tobacconomics cigarette Tax scorecard. Chicago, IL: Health Policy Center, Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois Chicago, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chaloupka FJ, Drope J, Siu E, et al. Tobacconomics cigarette Tax scorecard. 2nd ed. Chicago: IL, Health Policy Center, Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois Chicago, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chaloupka FJ, Straif K, Leon ME, et al. Effectiveness of Tax and price policies in tobacco control. Tob Control 2011;20:235–8. 10.1136/tc.2010.039982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guindon GE, Paraje GR, Chaloupka FJ. The impact of prices and taxes on the use of tobacco products in Latin America and the Caribbean. Am J Public Health 2018;108:S492–502. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302396r [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bader P, Boisclair D, Ferrence R. Effects of tobacco taxation and pricing on smoking behavior in high risk populations: a knowledge synthesis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2011;8:4118–39. 10.3390/ijerph8114118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nazar GP, Sharma N, Chugh A, et al. Impact of tobacco price and taxation on affordability and consumption of tobacco products in the south-east Asia region: a systematic review. Tob Induc Dis 2021;19:1–17. 10.18332/tid/143179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yeh C-Y, Schafferer C, Lee J-M, et al. The effects of a rise in cigarette price on cigarette consumption, tobacco taxation revenues, and of smoking-related deaths in 28 EU countries-- applying threshold regression modelling. BMC Public Health 2017;17:676. 10.1186/s12889-017-4685-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ross H, Blecher E, Yan L, et al. Do cigarette prices motivate smokers to quit? new evidence from the ITC survey. Addiction 2011;106:609–19. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03192.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Feliu A, Filippidis FT, Joossens L, et al. Impact of tobacco control policies on smoking prevalence and quit ratios in 27 European Union countries from 2006 to 2014. Tob Control 2019;28:101–9. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-054119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dunlop SM, Perez D, Cotter T. Australian smokers' and recent quitters' responses to the increasing price of cigarettes in the context of a tobacco Tax increase. Addiction 2011;106:1687–95. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03492.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ross H, Kostova D, Stoklosa M, et al. The impact of cigarette excise taxes on smoking cessation rates from 1994 to 2010 in Poland, Russia, and Ukraine. Nicotine Tob Res 2014;16 Suppl 1:S37–43. 10.1093/ntr/ntt024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ross H, Chaloupka FJ. The effect of cigarette prices on youth smoking. Health Econ 2003;12:217–30. 10.1002/hec.709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kostova D, Chaloupka FJ, Shang C. A duration analysis of the role of cigarette prices on smoking initiation and cessation in developing countries. Eur J Health Econ 2015;16:279–88. 10.1007/s10198-014-0573-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hawkins SS, Bach N, Baum CF. Impact of tobacco control policies on adolescent smoking. J Adolesc Health 2016;58:679–85. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.02.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Blecher EH, van Walbeek CP. An international analysis of cigarette affordability. Tob Control 2004;13:339–46. 10.1136/tc.2003.006726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. He Y, Shang C, Chaloupka FJ. The association between cigarette affordability and consumption: an update. PLoS One 2018;13:e0200665. 10.1371/journal.pone.0200665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hu X, Wang Y, Huang J, et al. Cigarette affordability and cigarette consumption among adult and elderly Chinese smokers: evidence from a longitudinal study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:4832. 10.3390/ijerph16234832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chaloupka FJ, Powell LM, Warner KE. The use of excise taxes to reduce tobacco, alcohol, and sugary beverage consumption. Annu Rev Public Health 2019;40:187–201. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shang C, Lee HM, Chaloupka FJ, et al. Association between Tax structure and cigarette consumption: findings from the International tobacco control policy evaluation (ITC) project. Tob Control 2019;28:s31–6. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-054160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Euromonitor International . Tobacco industry market research, 2021. Available: https://www.euromonitor.com/tobacco [Accessed 1 Aug 2021].

- 24. World Health Organization . Who report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2015, 2015. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/178574/9789240694606_eng.pdf [Accessed 1 Aug 2021].

- 25. World Health Organization . Who report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2017, 2017. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/255874 [Accessed 1 Aug 2021].

- 26. World Health Organization . Who report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2019, 2019. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241516204 [Accessed 1 Aug 2021].

- 27. Flor LS, Reitsma MB, Gupta V, et al. The effects of tobacco control policies on global smoking prevalence. Nat Med 2021;27:239–43. 10.1038/s41591-020-01210-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Husain MJ, Datta BK, Nargis N, et al. Revisiting the association between worldwide implementation of the MPOWER package and smoking prevalence, 2008-2017. Tob Control 2021;30:630–7. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-055758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. World Bank . World development indicators, 2021. Available: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator [Accessed 1 Aug 2021].

- 30. Vittinghoff E, Glidden DV, Shiboski SC, et al. Regression methods in biostatistics: linear, logistic, survival, and repeated measures models. 2nd ed. 2012 edition. Springer, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Blecher E, Liber A, Ross H, et al. Euromonitor data on the illicit trade in cigarettes. Tob Control 2015;24:100–1. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gallagher AWA, Gilmore AB. Euromonitor international now accepts tobacco industry funding: a WIN for PMI at the expense of research on the tobacco industry, 2019. Available: https://blogs.bmj.com/tc/2019/04/08/euromonitor-international-now-accepts-tobacco-industry-funding-a-win-for-pmi-at-the-expense-of-research-on-the-tobacco-industry/ [Accessed 06 Jul 2022].

- 33. Jha P, Chaloupka FJ. The economics of global tobacco control. BMJ 2000;321:358–61. 10.1136/bmj.321.7257.358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Savell E, Gilmore AB, Sims M, et al. The environmental profile of a community's health: a cross-sectional study on tobacco marketing in 16 countries. Bull World Health Organ 2015;93:851–61. 10.2471/BLT.15.155846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ho L-M, Schafferer C, Lee J-M, et al. Raising cigarette excise tax to reduce consumption in low-and middle-income countries of the Asia-Pacific region:a simulation of the anticipated health and taxation revenues impacts. BMC Public Health 2018;18:1187. 10.1186/s12889-018-6096-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

tc-2022-057486supp001.pdf (129.1KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. Except for data from Euromonitor International, data used in this study are publicly available.