Abstract

Background

Robotic-assisted neurointervention was recently introduced, with implications that it could be used to treat neurovascular diseases.

Objective

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of the robotic-assisted platform CorPath GRX for treating cerebral aneurysms.

Methods

This prospective, international, multicenter study enrolled patients with brain aneurysms that required endovascular coiling and/or stent-assisted coiling. The primary effectiveness endpoint was defined as successful completion of the robotic-assisted endovascular procedure without any unplanned conversion to manual treatment with guidewire or microcatheter navigation, embolization coil(s) or intracranial stent(s) deployment, or an inability to navigate vessel anatomy. The primary safety endpoint included intraprocedural and periprocedural events.

Results

The study enrolled 117 patients (74.4% female) with mean age of 56.6 years from 10 international sites,. Headache was the most common presenting symptom in 40/117 (34.2%) subjects. Internal carotid artery was the most common location (34/122, 27.9%), and the mean aneurysm height and neck width were 5.7±2.6 mm and 3.5±1.4 mm, respectively. The overall procedure time was 117.3±47.3 min with 59.4±32.6 min robotic procedure time. Primary effectiveness was achieved in 110/117 (94%) subjects with seven subjects requiring conversion to manual for procedure completion. Only four primary safety events were recorded with two intraprocedural aneurysm ruptures and two strokes. A Raymond-Roy Classification Scale score of 1 was achieved in 71/110 (64.5%) subjects, and all subjects were discharged with a modified Rankin Scale score of ≤2.

Conclusions

This first-of-its-kind robotic-assisted neurovascular trial demonstrates the effectiveness and safety of the CorPath GRX System for endovascular embolization of cerebral aneurysm procedures.

Trial registration number

Keywords: Aneurysm, Brain, Coil, Stent, Technology

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN

Robotic-assisted neurovascular intervention was recently introduced, with only a handful of published cases.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This is the first-of-its-kind trial to assess the efficacy and safety of robotics use in neurovascular intervention. From this trial, we now know that robotic-assisted neurovascular intervention is an effective and safe method to embolize cerebral aneurysms.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE, OR POLICY

This study opens the future potential of robotic integration in neurovascular intervention and is a stepping stone to a future of remote technology in the field of healthcare.

Introduction

Cerebral aneurysms affect 2–4% of the population and they can present with a life-threatening rupture with an estimated fatality rate of between 26% and 36%.1–3 Once an unruptured aneurysm is detected, the decision to intervene balances the risk–benefit profile of the available interventions against watchful waiting.4–9 Treatment options include surgical clipping or endovascular therapies, including coiling, stent-assisted coiling, flow diverters, and intrasaccular devices.10 11 The pace of adoption of percutaneous neuroendovascular techniques continues to accelerate, necessitating new technological advancements to improve procedure precision and safety.

The CorPath GRX system is the first robotic platform designed to accommodate the micro guidewires, microcatheters, and microscale movements specific to successful neurovascular interventions. The advent of this robot for percutaneous coronary interventions and peripheral vascular interventions has already begun to address some of the limitations of endovascular interventions.12–20 The CorPath GRX system translates the manual movements of the interventionalist into precision micromovements during navigation and facilitates precision measurement of anatomy to determine lesion length.21 22 It also allows the procedure to be performed from a remote, radiation-shielded workstation, which might help to reduce the interventionalist’s exposure to ionizing radiation and orthopedic strain.17 23–25

In an initial evaluation of the system in in vitro animal neurovascular models,26 Corindus recently implemented software and engineering modifications to its CorPath GRX Robotic System to address neuroendovascular-specific needs and indications: (1) active device fixation, which maintains the placement of both the guidewire and device while the catheter is advanced or retracted by advancing or retracting the guidewire and device to offset the motion of the catheter, (2) limited speed software to reduce the linear movement of the guidewire or device by half, capping its maximum speed at a rate of 6 mm/s, (3) physical modifications to the hardware to securely, and reliably accommodate, the smaller gauge devices common to neurovascular procedures, and (4) software modifications to allow for increased working length to enable target access for microcatheters and an updated user interface to accommodate the new workflow and automated movements. Robotic neurointervention procedures have been performed27 and early feasibility studies have demonstrated successful procedural execution and manual comparable long term follow-ups in complex aneurysm treatments.28–31

This clinical study is a prospective, single-arm, international, multicenter, non-inferiority study to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of the CorPath GRX Robotic System for endovascular cerebral aneurysm embolization compared with historical manual cerebral aneurysm treatment equivalent controls. The primary effectiveness endpoint was defined as successful completion of the robotic-assisted endovascular procedure in the absence of any unplanned conversion to manual for guidewire or microcatheter navigation, embolization coil(s) or intracranial stent(s) deployment, or an inability to navigate vessel anatomy. The primary safety endpoint consisted of a composite of intraprocedural and periprocedural events, including target aneurysmal rupture, vessel perforation or dissection, and major stroke within 24 hours of postprocedure or discharge, whichever occurs first. The secondary endpoints consisted of clinical outcome using the modified Rankin Scale as well as procedure characteristics, including overall robotic and fluoroscopy time, patient radiation exposure, and angiographic assessment of aneurysm occlusion grade according to the Raymond-Roy Classification Scale.

Materials and methods

Study population

The inclusion criteria for this trial were (1) age ≥18 years, (2) at least one cerebral aneurysm (unruptured) with indication for endovascular treatment; dome to neck ratio >1.5 or aneurysm neck width >4.0 mm, (3) the investigator deemed the procedure appropriate for both manual or robotic-assisted endovascular treatment, (4) patients were informed of the nature of the study and have provided written informed consent. Prospective consecutive recruitment was encouraged, and subjects were excluded if there was (1) failure/unwillingness of the subject to provide informed consent or if the ethics committee has waived informed consent, (2) the investigator determines that the subject or the neurovascular anatomy is not suitable for robotic-assisted endovascular treatment, (3) women who are pregnant, or (4) people under guardianship or curatorship. Subjects were screened for eligibility based on standard of care assessments, by Oculus Imaging LLC (Knoxville, Tennessee, USA), an independent eligibility committee and administration services provider.

This study was conducted at 10 sites in six countries, including a premarket study in Canada and postmarket study in Australia, Austria, France, Spain, and Switzerland. The study was conducted according to Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants. Each participating site obtained approval from independent ethics committees and approval as defined in the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki, Competent Authority review and approval (if applicable), ISO 14155:2020(E), and the Medical Device Regulations (2017/745) of April 5, 2017. Avania (Bilthoven Netherlands), a contract research organization was responsible for implementing and maintaining monitoring services, with written standard operating procedures to ensure that the clinical investigation was conducted, and data were generated, documented (recorded), and reported in compliance with the clinical investigation plan and above-mentioned guidelines. A surveillance committee, composed of three expert physicians in the field of interventional neuroradiology and/or neurosurgery, who were independent and not directly involved in the conduct of the trial, reviewed and adjudicated all adverse events over the course of the study. Any missing data were provided on request by the independent committee.

This study was reported using the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) cohort reporting guidelines.32

Statistical methods

The hypothesis of the endpoints was determined by historical rates from a literature overview (table 1) and pooled results from both arms from three randomized control trials (table 2).

Table 1.

Rates of safety from the literature for endovascular treatment of unruptured and ruptured aneurysms

| N Aneurysms (subjects) |

Mortality at discharge | Overall complication rate | Rupture/ perforation rate (%) |

Embolism rate (%) | |

| Ruptured intracranial aneurysms | |||||

| Algra et al 2019* 33 | 73 066 (71 819) | 0.3% (0.2–0.4%) | 4.96% (4.00, 6.12%) | 0.9% (212/18 520) 95% CI (0.6% to 1.3%) |

2.82% (437/16 000) 95% CI (2.3% to 3.5%) |

| Advanced endovascular methods†33 | 2248 | 0.4% (0.2–1.1%) | 6.1% (4.3, 8.7%) | ||

| Kawbata et al 201834 | 1406 (1375) | 1.4% (20/1406) | |||

| Coil only | 340 | 1.8% (6/340) | |||

| Stent-assisted coiling | 468 | 0.9% (4/468) | |||

| Balloon-assisted coiling | 598 | 1.7% (10/598) | |||

| From lit review, table 6 in Kawbata34 | 7785 | 0% | 1.4% (108/7785) | ||

| Zheng et al 201635 | 1127 | 1% (11/1127) | |||

| Santillan et al 2013 36 | 217 | 0% | 1.1% (3/217) | ||

| Shigematsu et al 201337 | 4767 | 1.4% (65/4767) | |||

| Oishi et al 201238 | 500 | 0% | 1.4% (7/500) | ||

| Im et al 200939 | 435 | 0% | 0.9% (4/435) | ||

| Pierot et al 200840 | 739 (649) | 0.3% | 2.4% (18/739) | 7.3% (29/398) | |

| (ATENA study) | (700 procs) | 1.4% (1 month) | 15.4% | 2.6% (18/700) | 7.1% (per proc) |

| Pierot et al 200941

(ATENA study, coil alone results) |

325 | 0.9% (3/325) | 10.8% (35/325) | 2.1% (7/325) | 6.2% (20/325) |

| Ruptured intracranial aneurysms | |||||

| Zhang et al 201942 | 1004 | All cause 9.5% (5.8%, 13.2%) procedure related 1.8% (0.9, 2.7%) | 22.7%‡ 95% CI (15.1% to 30.3%) | ||

| Cognard et al 201143

(CLARITY GDC study) |

405 | 1.50% | 3.7% (15/405) | 13.3% (54/405) | |

| Pierot et al 2011 (CLARITY)44 | 608 | 5.1% (31/608) cum. treatment-related morbidity/mortality rate 19.6% (119/608) with. morbidity/mortality rate) |

17.4% (106/608) | 4.6% (28/608) | |

*Rates presented are pooled crude risk from meta-analysis modeling.

†Advanced=stent-assisted coiling, balloon-assisted coiling, flow diverting stents or Woven Endobridge devices.

‡Definition not specified.

Table 2.

Pooled results from three randomized controlled trials

| HELPS Trial | N | Mortality | Procedural aneurysm rupture | Thromboembolic complication | Technical success | ||||

| White et al 200845 | 499 | 2.2% (11/499) At discharge | 3.4% (17/499) | 10.2% (51/499) | 96.6% (482/499) | ||||

| MAPS Trial | N | Mortality | Overall complication rate | Clinical event committee adjudicated | Technical success | ||||

| Rupture/ re-rupture | Ischemic stroke | Hemorrhagic stroke | |||||||

| McDougall et al 2014 46 | 626 | 0.2% (1/624) Periproc 2.4% (15/626) 30 day |

14.9% (93/624) | 0.3% (2/626) | 3.4% (21/626) | 1.1% (7/626) | 97.1% (608/626) | ||

| Cerecyte Trial | N | Mortality |

Overall

complication rate |

Procedural

aneurysm rupture |

Thromboembolic

complication |

Neuro

deterioration |

Technical

success |

||

| Coley et al 2012 47 | 497 | 0% within 24 hours 0.4% (2/497) discharge | 12.3% (61/497) | 3.6% (18/497) | 5.6% (28/497) | 3.0% (15/497) | 97.2% (483/497) | ||

The effectiveness hypothesis was:

H0: p≤80% (90%–10% non-inferiority margin)

Ha: p>80% where pP=proportion of subjects with a successfully completed endovascular procedure.

The safety hypothesis was:

H0: p≥15% (5%+10% non-inferiority margin)

Ha: p<15% where p=proportion of subjects with a safety event.

Both these endpoints will be summarized along with a two-sided Clopper-Pearson Exact 95% CI. The overall trial sample size was driven by at least 108 subjects enrolled. The secondary endpoints were analyzed with descriptive statistics along with a 95% CI.

The results compiled by this report, include the primary effectiveness and safety endpoints data, monitored through 24 hours postprocedure or hospital discharge, whichever occurred first. All subjects finished this initial timeline for analysis, and the study population is currently being followed up through 180 days for completion of this study.

Results

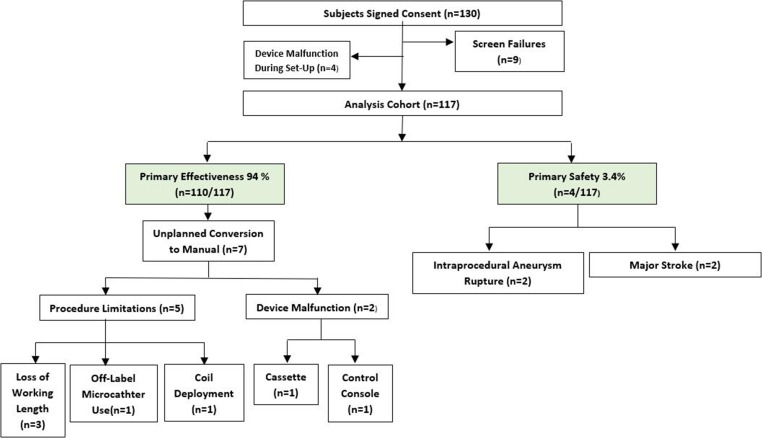

The study is summarized in figure 1. A total of 130 subjects were screened and provided written informed consent between August 2020 and April 2022. The complete follow-up period is 180 days. Nine of these subjects were screen failures and four device malfunction during set-up, leading to 117 subjects being included in the analysis population, completed by 14 operators.

Figure 1.

A flowchart of the executive trial summary.

Four device malfunctions occurred during procedural setup: two extended-reach arm failures, one software initiation failure, and one cassette and/or console error. As the procedure was not performed robotically, these subjects were not included in the analysis cohort. Three of these were encountered at the same site. Both extended-reach arm malfunctions happened consecutively, and inspection revealed the cables were not securely connected, with the issue being resolved immediately once the cables were securely attached. The initiation failure happened due to the robot power supply being connected to an outlet controlled by the fluoroscopy pedal, leading to the robotic power being turned off when the fluoroscopy pedal was pressed, which led the robot to not start while the other equipment was in use and was resolved on dealing with this concern. The last one was identified as a cassette and/or console error, which was encountered after connecting the devices, on which an error was noted and prevented the continuation of the procedure robotically.

Table 3 summarizes the subject demographics and medical history. The mean age of subjects was 56.6±12.7 years, with 74% of the subjects being female. History of smoking was prevalent in 59% of subjects. Hypertension in 49.6% of subjects was the leading comorbidity reported, followed by multiple aneurysms in 38.5% and dyslipidemia in 22.2% of subjects.

Table 3.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics

| Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics | Subjects (n=117) |

| Age, mean (range) | 56.6±12.7 (22 to 79) |

| Sex | Female 74.4%, males 25.6% |

| BMI (n=115) | 26.7±5.5 (15.6 to –44.3) |

| Medical history | |

| History of smoking | 59.0% (69/117) |

| Hypertension | 49.6% (58/117) |

| Multiple aneurysms | 38.5% (45/117) |

| Dyslipidemia | 22.2% (26/117) |

| Family history of UIA or SAH | 17.9% (21/117) |

| History of SAH | 17.1% (20/117) |

| Diagnosed with other rare disease/condition | 10.3% (12/117) |

| Diabetes | 8.5% (10/117) |

| Possible excess alcohol use | 6.0% (7/116) |

| Indications | |

| Asymptomatic or incidental aneurysm | 54.7% (64/117) |

| Headache | 34.2% (40/117) |

| Aneurysm(s) with a prior SAH from a separate aneurysm | 6.0% (7/117) |

| Stroke | 1.7% (2/117) |

BMI, body mass index; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; UIA, unruptured intracranial aneurysm.

Aneurysm characteristics are summarized in table 4. Most of the aneurysms were located at the internal carotid artery (27.9%), followed by the anterior communicating artery (22.1%) and middle cerebral artery (9.8%). The mean aneurysm height and neck width was 5.7±2.6 mm and 3.5±1.4 mm, respectively. The mean aneurysm dome to neck ratio was 1.7±0.4.

Table 4.

Aneurysm characteristics

| Aneurysm characteristics | n=122 |

| Location | |

| Internal carotid artery | 27.9% (34/122) |

| Anterior communicating artery | 22.1% (27/122) |

| Middle cerebral artery | 9.8% (12/122) |

| Posterior communicating artery | 9.0% (11/122) |

| Basilar artery | 8.2% (10/122) |

| Anterior cerebral artery | 3.3% (4/122) |

| Anterior choroidal artery | 2.5% (3/122) |

| Posterior cerebral artery | 1.6% (2/122) |

| Other | 15.6% (19/122) |

| Aneurysm height (mm) | 5.7±2.6 (1.5 to 15) |

| Aneurysm neck width (mm) | 3.5±1.4 (1.2 to 9.2) |

| Dome to neck ratio | 1.7±0.4 (0.8 to 3.0) |

| Relationship to parent wall | |

| Bifurcation | 41.0% (50/122) |

| Sidewall | 59.0% (72/122) |

Procedural characteristics are presented in table 5. The access site was femoral in 60.7% and radial in 37.6 % of subjects. All 117 subjects were treated with the primary coiling procedure, with 58 subjects requiring adjunct stenting. The mean number of coils implanted was 4.8±3.9. Of the 58 stenting subjects, 50 received one stent, alongside eight subjects receiving two or more stents. The overall procedure time was 117.3±47.3 min, with the robotic procedure time of 59.4±32.6 min. The total fluoroscopy time was 51.9±27.4 min with total contrast of 185.4±82.3 cc.

Table 5.

Procedural characteristics

| Procedural characteristics | |

| Access Site | |

| Femoral | 60.7% (71/117) |

| Radial | 37.6% (44/117) |

| Brachial | 1.7% (2/117) |

| No. of coils implanted (n=117) | 4.8±3.9 (0 to 31) |

| Stents implanted | |

| 0 | 50.4% (59/117) |

| 1 | 42.7% (50/117) |

| ≥2 | 6.9% (8/117) |

| Maximum stent diameter (mm) (n=58) | 3.9±0.7 (3 to 6) |

| Overall procedure time (min) (n=115) | 117.3±47.3 (17 to 259) |

| Robotic procedure time (min) (n=116) | 59.4±32.6 |

| Fluoroscopy time (min) (n=117) | 51.9±27.4 (10 to 157) |

| Total contrast (cc) (n=116) | 185.4±82.3 (60 to 530) |

| Subject radiation exposure (mGy.cm²) (n=104) | 6 886 135.5±25 767 850.8 (16 814.7 to 143 730 000) |

| Air Kerma (mGy) (n=98) | 2220.4±1526.9 (1914 to 2527) |

Primary effectiveness success was achieved with the procedure completed robotically in 94.0% (110/117) (88.1%, 97.6%) subjects. Unplanned manual conversion was done in 6.0% (7/117) subjects. Two device malfunctions occurred: (1) the control console malfunction was attributed to the joystick capacitive functionality, which was not actuating when touched; an investigation identified a loosened joystick cover mounting screws impact from shipping or improper handling, and (2) the cassette malfunction was attributed to an unknown root cause. Five procedural limitations were attributed as follows: three, loss of working length attributed to intermediary catheter placement that contributed to insufficient working length for the microcatheter; one due to off-label microcatheter use during procedure; and one attributed to early detachment of the second coil not allowing its insertion into the aneurysm. Table 6 summarizes the primary endpoint results.

Table 6.

Primary endpoints

| Endpoint | Analysis cohort (Subjects) |

| Primary Effectiveness | 94.0% (110/117) (88.1%, 97.6%) |

| Procedure Completed Robotically | 94.0% (110/117) |

| Unplanned Manual Conversion | 6.0% (7/117) |

| Device Malfunction | 1.7% (2/117) |

| Control Console Failure | 0.9% (1/117) |

| Cassette Failure | 0.9% (1/117) |

| Procedural Limitation | 4.3% (5/117) |

| Loss of Working Length | 2.6% (3/117) |

| Use of Off-label Microcatheter | 0.9% (1/117) |

| Coil Deployment | 0.9% (1/117) |

| Primary Safety | 3.4% (4/117) (0.9%, 8.5%) |

| Stroke (Major) | 1.7% (2/117) |

| Intraprocedural Aneurysm Rupture | 1.7% (2/117) |

Primary safety endpoint occurred in 3.4% (4/117) (0.9%, 8.5%) subjects, with two major strokes and two intraprocedural aneurysm ruptures. A total of 24 adjudicated adverse events were reported. Stroke was the most common serious adverse event reported in 12 subjects, with 10 experiencing a minor stroke and only two with a major stroke. Vascular access site complications were reported in four subjects and intraprocedural aneurysm ruptures in two. Electrolyte disorder occurred in two subjects; and hydrocephalus, vasospasm, respiratory failure, and urine infection were each reported once. Table 7 summarizes these adverse events, and table 8 details the presentation and clinical outcome of each adverse event.

Table 7.

All adverse events within 24 hours (adjudicated)

| Adverse event type | No. of subjects (%) |

| Stroke (minor) | 10/117 (8.5%) |

| Stroke (major) | 2/117 (1.7%) |

| Intraprocedural aneurysm rupture | 2/117 (1.7%) |

| Vascular access site complication | 4/117 (3.4%) |

| Electrolyte disorder | 2/117 (1.7%) |

| Hydrocephalus | 1/117 (0.9%) |

| Vasospasm | 1/117 (0.9%) |

| Respiratory failure | 1/117 (0.9%) |

| Urine infection | 1/117 (0.9%) |

Table 8.

Adverse event presentation and outcome

| All adverse events: classification and outcome | |

| Stroke (Minor) | |

| 01–29 | Seizure episode - home discharge on third postoperative day with mRS score 1 |

| 01–35 | Headache and loss of strength/sensation episode overnight - home discharge on third postoperative day with mRS score 0 |

| 02–19 | NIHSS score 2 Stroke - home discharge on fifth postoperative day with mRS score 1 |

| 02–20 | NIHSS score 1 Stroke - private rehab discharge on ninth postoperative day with mRS score 1 |

| 02–22 | NIHSS score 2 Stroke - home discharge on fifth postoperative day with mRS score 1 |

| 02–23 | Left extremities' weakness - home discharge on sixth postoperative day with mRS score 0 |

| 02–25 | Right upper limb weakness and sluggish pupil - home discharge on ninth postoperative day with mRS score 0 |

| 02–27 | Aphasia/altered sensation/panic episode - home discharge on fifth postoperative day with mRS score 1 |

| 07–10 | Somnolent with acute respiratory insufficiency – home discharge on ninth postoperative day with mRS score 1 |

| 11–02 | ‘Discrete micro-ischemia’ on Imaging – home discharge on second postoperative day with mRS score 0 |

| Stroke (major) | |

| 01–05 | NIHSS 1 Stroke with anterograde amnesia – home discharge on second postoperative day with mRS score 1 |

| 04–06 | Right hemi-paresis requiring intra-arterial fibrinolysis - home discharge on third postoperative day with mRS score 1 |

| Intraprocedural aneurysm rupture | |

| 01–19 | Rupture during second coil deployment, with hemostasis rapidly achieved with heparin reversion and further coiling |

| 04–04 | Rupture during coil deployment, with extravasation stopped via manual carotid compression and remodeling balloon inflation at aneurysmal neck |

| Vascular access site complication | |

| 01–33 | Minor hematoma at puncture site |

| 05–10 | Pseudoaneurysm requiring 2 units of blood transfusion |

| 05–19 | Hematoma requiring a follow-up CT scan, leading to extended hospitalization |

| 10–11 | Retroperitoneal hematoma requiring 1 unit of blood transfusion |

| Electrolyte disorder | |

| 04–04 | During hospital course of same subject with intraprocedural aneurysm rupture |

| 04–06 | During hospital course of same subject with major stroke |

| Hydrocephalus | |

| 04–04 | Same subject with intraprocedural aneurysm rupture, requiring external ventricular drainage placement |

| Vasospasm | |

| 04–06 | Same subject with major stroke - focal vasospasm, responded to nimodipine infusion |

| Respiratory failure | |

| 07–10 | Same subject with minor stroke – acute respiratory insufficiency due to chronic emphysema |

| Urine Infection | |

| 05–08 | Antibiotic treatment requiring prolonged hospitalization |

mRS, modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

A postprocedure Raymond-Roy Classification Scale score of 1 was achieved in 64.5% of subjects, signifying complete obliteration; followed by 4.5% having residual neck and the remaining 31% with a residual aneurysm. The modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score was 0 for 78.2% of the subjects post procedure, with no subjects having mRS score ≥3. Tables 9 and 10 summarize this information. Both, the Raymond-Roy Classification Scale and mRS will be continued to follow-up for all subjects till 180 days, as part of the trial design.

Table 9.

Raymond-Roy Classification scale

| Raymond-Roy Classification Scale (postprocedure) n=110 | |

| 1 | 64.5% (71/110) |

| 2 | 4.5% (5/110) |

| 3a | 25.5% (28/110) |

| 3b | 5.5% (6/110) |

Table 10.

Modified Rankin Scale

| Clinical outcome | ||

| Modified Rankin Scale | Preprocedure | Postprocedure |

| n=mean± SD (range) | 115=0.4±0.6 (0 to 2) | 78=0.3±0.5 (0 to 2) |

| 0 | 65.2% (75/115) | 78.2% (61/78) |

| 1 | 28.7% (33/115) | 17.9% (14/78) |

| 2 | 6.1% (7/115) | 3.8% (3/78) |

Discussion

The primary effectiveness success achieved in 94% (110/117) subjects was slightly lower than technical success of the three randomized controlled trials: HELPS, MAPS, and Cerecyte Trial, ranging from 96.6 to 97.2%. Of the seven unplanned conversions to manual treatment that were attributed to not meeting the primary effectiveness endpoint, only two were attributed to device malfunctions that happened during the procedure, with the remaining five procedural limitations. Table 11 summarizes the literature comparison.

Table 11.

Aneurysm treatment prospective studies literature used for comparison

| HELPS Trial | MAPS Trial | Cerecyte Trial | CorPath GRX | ||||

| Technical success | 96.6 % | 97.1 % | 97.2 % | 94.0 % | |||

| Intraprocedural aneurysm rupture | 3.4 % | 2.2 % | 3.6 % | 2.6 % | |||

| Thromboembolic complications | 10.2 % | 4.5 % | 5.6 % | 10.25 % | |||

| Mortality | 2.2% at discharge | 0.2% periprocedural | 0.4% before discharge | 0% at discharge | |||

| Raymond-Roy Scale postprocedure | Operator self-assessed | Core-laboratory review | Core-laboratory review | Core-laboratory review | |||

| 1 | 47.5 % | 36.1 % | 26.2 % | 64.5% | |||

| 2 | 34.5 % | 26.2 % | 49.5 % | 4.5 % | |||

| 3 | 18.0 % | 37.7 % | 24.3 % | 31.0 % | |||

| Clinical assessment at discharge | WFNS | mRS | mRS | ||||

| 0 | 38.5 % | 0 | 81.8 % | 0 | 78.2 % | ||

| 1–2 | 55.3 % | 1 | 15.9 % | 1 | 17.9 % | ||

| ≥ 3 | 6.0 % | 2 | 2.3 % | 2 | 3.8 % | ||

| ≥ 3 | 0 % | ≥ 3 | 0 % | ||||

mRS, modified Rankin Scale; WFNS, World Federation of Neurological Surgeons.

In subjects treated with the CorPath GRX System, a total of 25 adverse events subjects were reported. All these events were reviewed and classified by an independent clinical events committee. Ten of these events were attributed to minor strokes with a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score <3, and each of them required no further intervention, with the subjects being clinically observed and discharged with an mRS score of either 0 or 1. Of the five main serious events that constituted primary safety endpoint failures, two were major strokes, and both subjects were discharged home clinically stable on the second and third postoperative, day respectively, with an mRS score of 1. Previous literature highlights thromboembolic complications ranging from 5.6% in the Cerecyte Trial to 10.2% in the HELPS Trial. Combining both minor and major stroke, constitute 10.26% (12/117), which is comparable to the upper limit reported by these randomized controlled trials described, all of our strokes concluded with the subjects discharged clinically stable with an mRS score ≤1. The two remaining events considered primarily safety endpoint failures, were intraprocedural aneurysm ruptures (1.7% subjects), which occurred within the range of these trials mentioned above: 2.2% in MAPS to 3.6% in Cerecyte.

Comparison of the core-laboratory reviewed Raymond-Roy Scale postprocedure showed that CorPath GRX had the highest cohort of complete obliteration score in 64.5 % subjects, and residual aneurysm in 31.0% of subjects, which was in comparison with the range of 24.3% in Cerecyte to 37.7% in MAPS. The modified Rankin Scale was almost similar to the those reported by Cerecyte, with no patient having an mRS score of ≥3.

Limitations

The current generation of robots has technical limitations that should be taken into consideration when planning surgery: the ability to manage a total of only one microcatheter and one microwire or device at a time; the requirement for the access system be placed manually; and the length of working time for a procedure. Future generations of the robotic system are expected to overcome these issues.

Conclusion

This first-of-its-kind robotic-assisted neurovascular trial demonstrates the effectiveness and safety of the CorPath GRX System for endovascular embolization cerebral aneurysm procedures.

Footnotes

Twitter: @VitorMendesPer1, @NMCancelliere, @Doctorgaldamez

Correction notice: Since this paper first published, the author David S Liebeskind has been added to the article.

Contributors: Guarantor: VMP. Conception and design: VMP, MP and RDT. Acquisition of data: all authors. Analysis and interpretation of data: VMP, MP and RDT. Drafting the article: VMP, MP, RB, RDT, HR and XYEL. Critically revising the article: all authors. Approved the final version of the manuscript: all authors.

Funding: This study was funded by Siemens Healthineers Endovascular Robotics.

Competing interests: VMP is an unpaid consultant for Siemens Healthinners Endovascular Robotics. The following authors have one or more competing interests: HR, NS, FC, DH, MP, JG, MK-O, RDT, RB. These competing interests include board membership, consultancy, employment, expert testimony grants, contract research, lectures/other education events, speakers’ bureau, and receipt of equipment or supplies, royalties, stock/stock options/other forms of ownership.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s)

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by The Unity Health Toronto Research Ethics Board; REB 20-333; Les Comités de Protection des Personnes IORG0009918; Gold Coast Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee EC00160; University Health Network Research Ethics Board 19-5517;Research Ethics Committee with Medicines of the Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron IRB00002850; Gesundheits-, Sozial- und Integrationsdirektion Kantonale Ethikkommission für die Forschung, Ethikkommission Bern 2021-D0024; Ethikkommission für das Bundesland Salzburg 1222/2021; Comité de Ética de la Investigación con Medicamentos Área de Salud Valladolid Este Hospital Clínico Valladolid CASVE-PS-20-443. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. Lawton MT, Vates GE. Subarachnoid hemorrhage. N Engl J Med 2017;377:257–66. 10.1056/NEJMcp1605827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lantigua H, Ortega-Gutierrez S, Schmidt JM, et al. Subarachnoid hemorrhage: who dies, and why Crit Care 2015;19:309. 10.1186/s13054-015-1036-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Connolly ES, Rabinstein AA, Carhuapoma JR, et al. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 2012;43:1711–37. 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182587839 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182587839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nasr DM, Brown RD. Management of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Curr Cardiol Rep 2016;18:86. 10.1007/s11886-016-0763-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ajiboye N, Chalouhi N, Starke RM, et al. Unruptured cerebral aneurysms: evaluation and management. ScientificWorldJournal 2015;2015:954954. 10.1155/2015/954954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pierot L, Gawlitza M, Soize S. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: management strategy and current endovascular treatment options. Expert Rev Neurother 2017;17:977–86. 10.1080/14737175.2017.1371593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boulouis G, Rodriguez-Régent C, Rasolonjatovo EC, et al. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: an updated review of current concepts for risk factors, detection and management. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2017;173:542–51. 10.1016/j.neurol.2017.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Flemming KD, Lanzino G. Management of Unruptured intracranial aneurysms and cerebrovascular malformations. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2017;23:181–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Williams LN, Brown RD. Management of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Neurol Clin Pract 2013;3:99–108. 10.1212/CPJ.0b013e31828d9f6b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Darsaut TE, Findlay JM, Magro E, et al. Surgical clipping or endovascular coiling for unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a pragmatic randomised trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2017;88:663–8. 10.1136/jnnp-2016-315433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ruan C, Long H, Sun H, et al. Endovascular coiling vs. surgical clipping for unruptured intracranial aneurysm: a meta-analysis. Br J Neurosurg 2015;29:485–92. 10.3109/02688697.2015.1023771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smitson CC, Ang L, Pourdjabbar A, et al. Safety and feasibility of a novel, second-generation Robotic-assisted system for percutaneous coronary intervention: first-in-human report. J Invasive Cardiol 2018;30:152–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Almasoud A, Walters D, Mahmud E. Robotically performed excimer laser coronary atherectomy: proof of feasibility. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2018;92:713–6. 10.1002/ccd.27589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Swaminathan RV, Rao SV. Robotic-assisted Transradial diagnostic coronary angiography. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2018;92:54–7. 10.1002/ccd.27480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mahmud E, Dominguez A, Bahadorani J. First-In-human robotic percutaneous coronary intervention for unprotected left main stenosis. Cathet. Cardiovasc. Intervent. 2016;88:565–70. 10.1002/ccd.26550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Behnamfar O, Pourdjabbar A, Yalvac E. First case of robotic percutaneous vascular intervention for below-the-knee peripheral arterial disease. J Invasive Cardiol 2016;28:E128–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mahmud E, Schmid F, Kalmar P, et al. Feasibility and safety of robotic peripheral vascular interventions: results of the RAPID Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2016;9:2058–64. 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Weisz G, Smilowitz NR, Metzger DC, et al. The association between experience and proficiency with robotic-enhanced coronary intervention—insights from the PRECISE multi-center study. Acute Card Care 2014;16:37–40. 10.3109/17482941.2014.889314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Smilowitz NR, Moses JW, Sosa FA. Robotic-enhanced PCI compared to the traditional manual approach. J Invasive Cardiol 2014;26:318–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weisz G, Metzger DC, Caputo RP, et al. Safety and feasibility of robotic percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:1596–600. 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.12.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Campbell PT, Kruse KR, Kroll CR, et al. The impact of precise robotic lesion length measurement on stent length selection: ramifications for stent savings. Cardiovasc Revasc Med 2015;16:348–50. 10.1016/j.carrev.2015.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bergman P, Blacker SJ, Kottenstette N, et al. Robotic-assisted percutaneous coronary intervention. In: Abedin-Nasab MH, ed. Handbook of Robotic and Image-Guided Surgery. Elsevier, 2020: 341–62. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Andreassi MG, Piccaluga E, Gargani L, et al. Subclinical carotid atherosclerosis and early vascular aging from long-term low-dose ionizing radiation exposure. JACC: Cardiovasc Interv 2015;8:616–27. 10.1016/j.jcin.2014.12.233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Andreassi MG, Piccaluga E, Guagliumi G, et al. Occupational health risks in cardiac catheterization laboratory workers. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2016;9:e003273. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.115.003273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Venneri L, Rossi F, Botto N, et al. Cancer risk from professional exposure in staff working in cardiac catheterization laboratory: Insights from the National Research Council’s Biological Effects of Ionizing Radiation VII Report. Am Heart J 2009;157:118–24. 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Britz GW, Tomas J, Lumsden A. Feasibility of robotic-assisted neurovascular interventions: initial experience in flow model and porcine model. Neurosurgery 2020;86:309–14. 10.1093/neuros/nyz064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mendes Pereira V, Cancelliere NM, Nicholson P, et al. First-In-human, robotic-assisted neuroendovascular intervention. J Neurointerv Surg 2020;12:338–40. 10.1136/neurintsurg-2019-015671.rep [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mendes Pereira V, Nicholson P, Cancelliere NM, et al. Feasibility of robot-assisted neuroendovascular procedures. J Neurosurg 2021;136:992–1004. 10.3171/2021.1.JNS203617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cancelliere NM, Lynch J, Nicholson P, et al. Robotic-assisted intracranial aneurysm treatment: 1 year follow-up imaging and clinical outcomes. J Neurointerv Surg 2022;14:1229–33. 10.1136/neurintsurg-2021-017865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Weinberg JH, Sweid A, Sajja K, et al. Comparison of robotic-assisted carotid stenting and manual carotid stenting through the transradial approach. J Neurosurg 2020;135:21–8. 10.3171/2020.5.JNS201421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Beaman C, Saber H, Tateshima S. A technical guide to robotic catheter angiography with the corindus corpath GRX system. J Neurointerv Surg 2022;14:1284. 10.1136/neurintsurg-2021-018347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Epidemiology 2007;18:800–4. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181577654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Algra AM, Lindgren A, Vergouwen MDI, et al. Procedural clinical complications, case-fatality risks, and risk factors in endovascular and neurosurgical treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol 2019;76:282–93. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kawabata S, Imamura H, Adachi H, et al. Risk factors for and outcomes of Intraprocedural rupture during endovascular treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. J Neurointerv Surg 2018;10:362–6. 10.1136/neurintsurg-2017-013156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zheng Y, Liu Y, Leng B, et al. Periprocedural complications associated with Endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms in 1764 cases. J Neurointerv Surg 2016;8:152–7. 10.1136/neurintsurg-2014-011459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Santillan A, Gobin YP, Mazura JC, et al. Balloon-assisted coil embolization of intracranial aneurysms is not associated with increased periprocedural complications. J Neurointerv Surg 2013;5 Suppl 3:iii56–61. 10.1136/neurintsurg-2012-010351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shigematsu T, Fujinaka T, Yoshimine T, et al. Endovascular therapy for asymptomatic unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Stroke 2013;44:2735–42. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Oishi H, Yamamoto M, Shimizu T, et al. Endovascular therapy of 500 small asymptomatic unruptured intracranial aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012;33:958–64. 10.3174/ajnr.A2858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Im S-H, Han MH, Kwon O-K, et al. Endovascular coil embolization of 435 small asymptomatic unruptured intracranial aneurysms: procedural morbidity and patient outcome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2009;30:79–84. 10.3174/ajnr.A1290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pierot L, Spelle L, Vitry F, et al. Immediate clinical outcome of subjects harboring unruptured intracranial aneurysms treated by endovascular approach: results of the ATENA study. Stroke 2008;39:2497–504. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.512756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pierot L, Spelle L, Leclerc X, et al. Endovascular treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms: comparison of safety of remodeling technique and standard treatment with coils. Radiology 2009;251:846–55. 10.1148/radiol.2513081056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhang X, Zuo Q, Tang H, et al. Stent assisted coiling versus non-stent assisted coiling for the management of ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Neurointerv Surg 2019;11:489–96. 10.1136/neurintsurg-2018-014388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cognard C, Pierot L, Anxionnat R, et al. Results of embolization used as the first treatment choice in a consecutive nonselected population of ruptured aneurysms: clinical results of the clarity GDC study. Neurosurgery 2011;69:837–41; 10.1227/NEU.0b013e3182257b30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pierot L, Cognard C, Anxionnat R, et al. Remodeling technique for endovascular treatment of ruptured intracranial aneurysms had a higher rate of adequate postoperative occlusion than did conventional coil embolization with comparable safety. Radiology 2011;258:546–53. 10.1148/radiol.10100894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. White PM, Lewis SC, Nahser H, et al. Hydrocoil endovascular aneurysm occlusion and packing study (HELPS trial): procedural safety and operator-assessed efficacy results. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008;29:217–23. 10.3174/ajnr.A0936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. McDougall CG, Johnston SC, Gholkar A, et al. Bioactive versus bare platinum coils in the treatment of intracranial aneurysms: the MAPS (matrix and platinum science). AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014;35:935–42. 10.3174/ajnr.A3857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Coley S, Sneade M, Clarke A, et al. Cerecyte coil trial: procedural safety and clinical outcomes in subjects with ruptured and unruptured intracranial aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012;33:474–80. 10.3174/ajnr.A2836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.