Key Points

Question

In children with intermittent exotropia, did the greater myopic shift observed after 1 year of overminus lens treatment (compared with nonoverminus treatment) persist 2 years after the start of weaning and cessation?

Findings

In this extension of the Trial of Overminus Spectacle Therapy for Intermittent Exotropia, mean myopic shift from baseline to 3 years was greater in the overminus group compared with the nonoverminus group. The myopic shift was similar between treatment groups from 1 year to 3 years.

Meaning

The myopic shift associated with 1 year of −2.50-diopter overminus lens treatment persisted after discontinuing the overminus spectacles, but it did not increase further compared with the nonoverminus group after overminus lens treatment weaning and cessation.

This extension of the Trial of Overminus Spectacle Therapy for Intermittent Exotropia compares refractive error change over 3 years in children with intermittent exotropia originally treated with overminus vs nonoverminus spectacles.

Abstract

Importance

Increased myopic shift was found to be associated with 1 year of overminus spectacle treatment for children with intermittent exotropia (IXT). Persistence of myopic shift after discontinuing overminus spectacles is unknown.

Objective

To compare refractive error change over 3 years in children with IXT originally treated with overminus vs nonoverminus spectacles.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This study was an 18-month extension of the Trial of Overminus Spectacle Therapy for Intermittent Exotropia cohort, which previously randomized children aged 3 to 10 years with IXT and baseline spherical equivalent refractive error (SER) between −6.00 diopters (D) and 1.00 D to overminus spectacles (−2.50 D for 12 months, −1.25 D for 3 months, and nonoverminus for 3 months) or nonoverminus spectacles. Children were recruited from 56 sites from July 2010 to February 2022. Data were analyzed from February 2022 to January 2024.

Interventions

After trial completion at 18 months, participants were followed up at 24 and 36 months. Treatment was at investigator discretion from 18 to 36 months.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Change in SER (cycloplegic retinoscopy) from baseline to 36 months.

Results

Of 386 children in the Trial of Overminus Spectacle Therapy for Intermittent Exotropia, 223 (57.8%) consented to 18 months of additional follow-up, including 124 of 196 (63.3%) in the overminus treatment group and 99 of 190 (52.1%) in the nonoverminus treatment group. Of 205 children who completed 36-month follow-up, 116 (56.6%) were female, and the mean (SD) age at randomization was 6.2 (2.1) years. Mean (SD) SER change from baseline to 36 months was greater in the overminus group (−0.74 [1.00] D) compared with the nonoverminus group (−0.44 [0.85] D; adjusted difference, −0.36 D; 95% CI, −0.59 to −0.12; P = .003), with 30 of 112 (26.8%) in the overminus group having more than 1 D of myopic shift compared with 14 of 91 (15%) in the nonoverminus group (risk ratio, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.0-3.0). From 12 to 36 months, mean (SD) myopic shift was −0.34 (0.67) D and −0.36 (0.66) D in the overminus and nonoverminus groups, respectively (adjusted difference, −0.001 D; 95% CI, −0.18 to 0.18; P = .99).

Conclusions and Relevance

The greater myopic shift observed after 1 year of −2.50-D overminus lens treatment remained at 3 years. Both groups had similar myopic shift during the 2-year period after treatment weaning and cessation. The risk of myopic shift should be discussed with parents when considering overminus lens treatment.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02807350

Introduction

Intermittent exotropia (IXT) is the most common form of divergent strabismus in childhood.1,2,3,4,5 Overminus lens therapy, consisting of spectacles with more minus power than cycloplegic refractive error, is a nonsurgical treatment option for childhood IXT. Clinicians classically use overminus lenses to temporarily improve IXT control in young children before considering strabismus surgery6,7,8,9,10,11 or vision therapy or orthoptics.7,10 If a child’s IXT is well controlled while wearing the overminus spectacles, some clinicians gradually wean patients off treatment by reducing the power or wear time8,9 to determine if the child can maintain good control without the need for further treatment.

In our previously reported randomized clinical trial (RCT) comparing overminus vs nonoverminus spectacles in children with IXT aged 3 to 10 years, the Trial of Overminus Spectacle Therapy for Intermittent Exotropia, we found improved distance IXT control after 12 months of overminus (−2.50 diopters [D]) spectacles. The treatment effect did not persist after participants were weaned off overminus spectacles for 3 months and examined 3 months later.12 Importantly, we also found the treatment was associated with increased myopic shift over 12 months,12 particularly among children with myopia at baseline. The primary objective of the current extension study was to evaluate change in refractive error 2 years after weaning and treatment discontinuation had begun to determine whether the myopic shift seen at 12 months persisted 3 years from treatment initiation.

Methods

The study was funded by the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki tenets by the Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group at 56 academic and community-based clinical sites. Community-based sites were approved by the Jaeb Center for Health Research Institutional Review Board. Institutional review boards for each site approved the protocol and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)–compliant informed consent forms. Each participant’s parent or guardian gave written informed consent, and if required, each participant gave assent. Study participants received $50 compensation per visit. The study is registered online13; the trial protocol can be found in Supplement 1, and the statistical analysis plan can be found in Supplement 2. The study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.

18-Month Randomized Trial

The initial 18-month RCT12 included 386 children aged 3 to 10 years with spherical equivalent refractive error (SER) between −6.00 D and 1.00 D as well as IXT of 15 prism diopters (∆) or more with a distance IXT control score (mean of 3 measures) of 2 points or more (range from 0 [phoria] to 5 [constant]).14,15 Participants were randomly assigned to overminus spectacles (−2.50 D over cycloplegic refraction for 12 months, −1.25 D for 3 months, then nonoverminus for 3 months; n = 189) or nonoverminus spectacles (n = 169) for 18 months, to be worn full-time.12 As a safety outcome, cycloplegic refraction was performed at baseline and 12 months to monitor change. Two years and 10 months after the RCT began, the data and safety monitoring committee observed greater myopic shift in the overminus group and recommended discontinuation of overminus spectacles for those still wearing the spectacles (17 of 196 [8.7%]) and adding a cycloplegic refraction at the 18-month visit for the remaining participants. Additional details have been published.12 Self-reported race and ethnicity data were collected via a questionnaire; categories included American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, more than 1 race, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, White, and unknown or not reported.

Post-RCT Follow-Up (Extension Study)

In December 2019, when 250 of 386 participants (64.8%) had completed the 18-month RCT, participants were asked to participate in the present post-RCT extension study. Follow-up visits occurred at 24 months (range, 21 to 27 months) and 36 months (range, 33 to 39 months) from randomization. A masked examiner measured near stereoacuity and performed 3 IXT control assessments (beginning, middle, and end of examination), cover-uncover test, and prism and alternate cover test at distance and near. Cycloplegic retinoscopy was performed 30 to 45 minutes following at least 1 drop of cyclopentolate, 1%. Cycloplegic autorefraction, axial length, flat corneal curvature, anterior chamber depth, and lens thickness were measured if autorefractors and biometers were available at the site. Treatment of IXT from 18 to 36 months was at investigator discretion.

Statistical Analysis

The primary analyses compared mean SER change by retinoscopy (more myopic eye at baseline) from baseline to 24 months and baseline to 36 months using analysis of covariance with adjustment for baseline SER in all participants who completed the respective visit. Missing data were not imputed and no adjustment for multiplicity was made for these primary outcomes because they were safety analyses.

As sensitivity analyses, the primary analyses were repeated but limited to participants who (1) completed the 24-month and 36-month visits within the study visit window, (2) were not treatment crossovers during the RCT, and (3) completed the 12-month RCT primary outcome visit. A fourth sensitivity analysis using the last-observation-carried-forward method imputed the last SER recorded for participants who started orthokeratology treatment. A fifth sensitivity analysis used multiple imputation to impute the missing 24-month and 36-month SER data for participants in the extension study.

A secondary outcome was the proportion of participants with an increase in SER myopia more than 1.00 D from baseline to 24 and 36 months, both overall and by baseline SER subgroups (−0.50 to −6.00 D, −0.375 to 0.375 D, and 0.50 to 1.00 D). The risk ratio (RR) between treatment groups for this proportion and the associated 95% CIs were calculated at both time points using Poisson regression with robust error variance and adjustment for baseline SER.16 As a sensitivity analysis for the myopia subgroup, the RR was also calculated for a different baseline refractive error subgroup (myopia: less than 0 to −6.00 D). Exploratory analyses on the SER outcomes were repeated based on cycloplegic autorefraction data (from participants with available data).

A post hoc treatment group comparison of mean SER change from 12 months (ie, time of tapering to −1.25 D overminus followed by discontinuing overminus at 15 months) to 36 months used methods similar to the primary analysis. In addition, mean change in SER from baseline to 12 months, 12 to 24 months, and 24 to 36 months were tabulated by treatment group.

As secondary analyses, axial length, flat corneal curvature, anterior chamber depth, and lens thickness of the most myopic eye at baseline were compared between treatment groups at 24 and 36 months using an analysis of variance model. Adjusting for baseline values was not possible because these measures were not collected at baseline. P values and 95% CIs were adjusted using the 2-stage step-up procedure to control the false discovery rate17 at 5%. Significance was set at P < .05, and all P values were 2-tailed. In exploratory analyses, the differences between treatment groups in exodeviation control, exodeviation magnitude, and near stereoacuity were estimated using analysis of covariance adjusted for the baseline measures; because of the exploratory nature of the analyses, only 95% CIs and not P values are reported. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

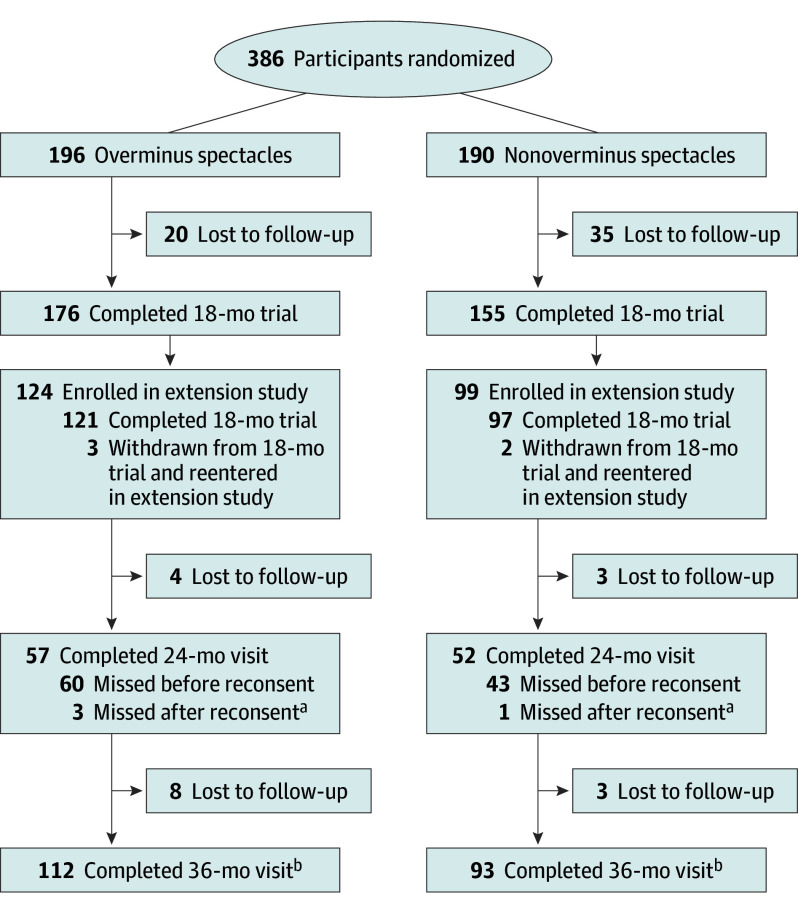

Of 386 children in the Trial of Overminus Spectacle Therapy for Intermittent Exotropia, 223 (57.8%) consented to 18 months of additional follow-up, including 124 of 196 (63.3%) in the overminus treatment group and 99 of 190 (52.1%) in the nonoverminus treatment group (Figure 1). Because 103 of 223 participants (46.2%) were at least 30 months postrandomization at the time of consent, a 24-month visit was not possible, which contributed to only 57 of 196 (29.1%) in the overminus group and 52 of 190 (27.4%) in the nonoverminus group completing this visit. The 36-month visit was completed by 112 of 196 participants (57.1%) and 93 of 190 participants (48.9%), respectively; of these, 116 (56.6%) were female, and the mean (SD) age at randomization was 6.2 (2.1) years. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, SER change from baseline to 12 months, and distance IXT control at 12 and 18 months appeared similar between participants who did and did not complete the 36-month visit (Table 1).

Figure 1. Study Flowchart.

aSeven in the overminus group and 4 in the nonoverminus group completed the 24-month visit out of the analysis window (≥630 and ≤899 days from randomization) for the primary analysis.

bOne in the overminus group and 3 in the nonoverminus group completed the 30-month visit out of the analysis window (≥900 and ≤1440 days from randomization) for the primary analysis.

Table 1. Participant and Ocular Characteristics by 36-Month Visit Completion Status.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completed 36-mo follow-up | Did not complete 36-mo follow-up | |||

| Overminus (n = 112) | Nonoverminus (n = 93) | Overminus (n = 84) | Nonoverminus (n = 97) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 64 (57) | 52 (56) | 48 (57) | 62 (64) |

| Male | 48 (43) | 41 (44) | 36 (43) | 35 (36) |

| Race and ethnicitya | ||||

| Asian | 3 (3) | 5 (5) | 3 (4) | 5 (5) |

| Black or African American | 19 (17) | 12 (13) | 15 (18) | 16 (16) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 21 (19) | 22 (24) | 10 (12) | 18 (19) |

| White | 60 (54) | 46 (49) | 53 (63) | 45 (46) |

| Other race | 9 (8) | 8 (9) | 3 (4) | 13 (13) |

| Age at randomization, y | ||||

| 3-<7 | 68 (61) | 65 (70) | 55 (65) | 55 (57) |

| 7-<11 | 44 (39) | 28 (30) | 29 (35) | 42 (43) |

| Mean (SD; range) | 6.4 (2.1; 3.0 to 11.0) | 6.0 (2.1; 3.0 to 10.7) | 6.4 (2.0; 3.0 to 11.0) | 6.5 (2.2; 3.1 to 10.7) |

| SER, Db | ||||

| >0.50 | 30 (27) | 24 (26) | 28 (33) | 35 (36) |

| >−0.75 to 0.50 | 65 (58) | 47 (51) | 36 (43) | 49 (51) |

| −0.75 to >−3.00 | 12 (11) | 20 (22) | 17 (20) | 12 (12) |

| ≤−3.00 | 5 (4) | 2 (2) | 3 (4) | 1 (1) |

| Mean (SD; range) | 0.01 (1.11; −6.00 to 1.25) | −0.11 (1.05; −3.75 to 1.00) | −0.05 (1.12; −3.75 to 1.00) | 0.13 (0.80; −3.25 to 1.00) |

| Change in SER from baseline to 12 mo, D | ||||

| Mean (SD; range) | −0.40 (0.66; −2.50 to 1.50) | −0.08 (0.46; −1.50 to 1.50) | −0.45 (0.72; −2.25 to 0.75) | 0 (0.45; −1.00 to 1.00) |

| Prior nonsurgical treatment for IXT | ||||

| None | 73 (65) | 67 (72) | 53 (63) | 70 (72) |

| Patching only | 26 (23) | 17 (18) | 27 (32) | 16 (16) |

| Vision therapy only | 7 (6) | 5 (5) | 3 (4) | 6 (6) |

| Patching plus other treatment | 3 (3) | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Other treatment | 3 (3) | 0 | 0 | 3 (3) |

| Randot preschool stereoacuity at near, arcsecondsc | ||||

| 40 to 100 | 69 (64) | 56 (63) | 51 (64) | 56 (60) |

| 200 to 800 | 30 (28) | 28 (31) | 22 (28) | 27 (29) |

| Nil | 9 (8) | 5 (6) | 7 (9) | 11 (12) |

| Median, log(arcseconds) | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Mean distance visual acuity, Snellen equivalentsd | ||||

| 20/12 to 20/20 | 57 (51) | 33 (35) | 29 (35) | 49 (51) |

| 20/25 to 20/32 | 46 (41) | 52 (56) | 49 (58) | 42 (43) |

| 20/40 to 20/50 | 9 (8) | 8 (9) | 6 (7) | 6 (6) |

| IOD of distance visual acuity, logMAR | ||||

| 0 | 85 (76) | 53 (57) | 45 (54) | 62 (64) |

| 0.1 | 22 (20) | 31 (33) | 35 (42) | 30 (31) |

| 0.2 | 5 (4) | 9 (10) | 4 (5) | 5 (5) |

| Prior spectacle wear | ||||

| No | 79 (71) | 65 (70) | 61 (73) | 77 (79) |

| Yes | 33 (29) | 28 (30) | 23 (27) | 20 (21) |

| Exotropia control at distancee | ||||

| 2 to <3 | 51 (46) | 41 (44) | 33 (39) | 37 (38) |

| 3 to <4 | 34 (30) | 22 (24) | 22 (26) | 30 (31) |

| 4 to 5 | 27 (24) | 30 (32) | 29 (35) | 30 (31) |

| Mean (SD; range) | 3.1 (1.0; 2.0 to 5.0) | 3.2 (1.1; 2.0 to 5.0) | 3.3 (1.1; 2.0 to 5.0) | 3.3 (1.0; 2.0 to 5.0) |

| Change in exotropia control at distance from baseline to 12 mo, mean (SD; range)e | 1.3 (1.4; −2.3 to 5.0) | 0.4 (1.2; −3.0 to 3.0) | 1.4 (1.3; −1.0 to 5.0) | 0.7 (1.5; −2.3 to 4.3) |

| Change in exotropia control at distance from baseline to 18 mo, mean (SD; range)e | 0.8 (1.4; −2.3 to 4.3) | 0.3 (1.5; −3.0 to 4.7) | 0.9 (1.5; −3.0 to 4.7) | 0.8 (1.7; −3.0 to 4.7) |

| Exotropia control at neare | ||||

| 0 to <1 | 25 (22) | 31 (33) | 12 (14) | 15 (15) |

| 1 to <2 | 37 (33) | 32 (34) | 43 (51) | 33 (34) |

| 2 to <3 | 30 (27) | 15 (16) | 9 (11) | 29 (30) |

| 3 to <4 | 16 (14) | 13 (14) | 15 (18) | 14 (14) |

| 4 to 5 | 4 (4) | 2 (2) | 5 (6) | 6 (6) |

| Mean (SD; range) | 1.7 (1.1; 0 to 4.7) | 1.4 (1.1; 0 to 4.3) | 1.7 (1.2; 0 to 4.7) | 1.9 (1.1; 0 to 4.7) |

| PACT exodeviation at distance, ∆f | ||||

| 10-15 | 4 (4) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 4 (4) |

| 16-18 | 27 (24) | 12 (13) | 15 (18) | 10 (10) |

| 19-25 | 49 (44) | 44 (47) | 37 (44) | 47 (48) |

| 30-35 | 26 (23) | 22 (24) | 28 (33) | 28 (29) |

| 40-45 | 6 (5) | 12 (13) | 3 (4) | 7 (7) |

| ≥50 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Esodeviation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mean (SD; range) | 24 (7; 15 to 45) | 27 (8; 15 to 50) | 25 (6; 15 to 40) | 26 (7; 15 to 50) |

| PACT exodeviation at near, ∆f | ||||

| No exodeviation (orthophoria) | 1 (<1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| 1-9 | 16 (14) | 10 (11) | 11 (13) | 14 (14) |

| 10-15 | 23 (21) | 21 (23) | 22 (26) | 24 (25) |

| 16-18 | 27 (24) | 15 (16) | 9 (11) | 14 (14) |

| 19-25 | 30 (27) | 30 (32) | 27 (32) | 29 (30) |

| 30-35 | 12 (11) | 10 (11) | 12 (14) | 11 (11) |

| 40-45 | 3 (3) | 6 (6) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| ≥50 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Esodeviation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Mean (SD; range) | 18 (9; 0 to 45) | 20 (10; 0 to 45) | 19 (9; 0 to 50) | 17 (9; −4 to 45) |

Abbreviations: ∆, prism diopter; D, diopters; IOD, interocular difference; IXT, intermittent exotropia; PACT, prism and alternate cover test; SER, spherical equivalent refractive error.

Race and ethnicity data were self-reported. The other race category includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, multiple, and unknown or unreported race.

SER in the most myopic eye.

Log(arcseconds) stereoacuity values range from 1.6 (40 arcseconds) to 3.2 (nil), with lower values being better. Four participants in the overminus group and 3 in the nonoverminus group who did not enroll in the extension study as well as 4 participants each in the overminus group and nonoverminus groups who enrolled in the extension study did not understand test instruction to complete the stereo test; therefore, their stereoacuity at baseline was missing.

Mean of the participant’s 2 eyes.

Mean of 3 assessments performed throughout the examination. Mean distance exotropia control of 2 points or higher (ie, worse) was required for eligibility. Change in distance exotropia control was calculated as baseline minus follow-up values, so positive change indicates improvement. Mean near exotropia control of less than 5 points (ie, could not be constant on all 3 of the measures) was required for eligibility.

PACT at distance was required to be at least 15 ∆ for eligibility. Additionally, the near exodeviation could not exceed that at distance by more than 10 ∆ (by PACT) for eligibility (ie, convergence insufficiency type IXT was excluded). Negative values represent esodeviation.

SER (Primary Outcomes)

Overall, the overminus group showed a greater mean (SD) SER myopic shift from baseline than the nonoverminus group at both 24 months (−0.61 [0.94] D vs −0.14 [0.65] D; adjusted difference, −0.52 D; 95% CI, −0.79 to −0.24; P < .001) and 36 months (−0.74 [1.00] D vs −0.44 [0.85] D; adjusted difference, −0.36 D; 95% CI, −0.59 to −0.12; P = .003) (Table 2). Sensitivity analyses yielded similar results (eTable 2 in Supplement 3).

Table 2. Refractive Error During Follow-Up in the Most Myopic Eye at Baseline.

| Measure | Overall (cycloplegic refraction) | Baseline SER (cycloplegic refraction)a | Overall (cycloplegic autorefraction)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.50 D to −6.00 D | −0.375 D to 0.375 D | 0.50 D to 1.00 D | |||

| 12 mo | |||||

| SER at 12 mo | |||||

| Overminus group | |||||

| Total, No. | 189 | 43 | 60 | 84 | 103 |

| Mean (SD) | −0.45 (1.55) | −2.79 (1.38) | −0.23 (0.67) | 0.54 (0.45) | −0.23 (1.63) |

| Nonoverminus group | |||||

| Total, No. | 169 | 44 | 48 | 77 | 104 |

| Mean (SD) | −0.04 (1.17) | −1.51 (1.22) | 0.05 (0.47) | 0.74 (0.44) | 0.15 (1.20) |

| Change in SER from baseline to 12 mo | |||||

| Overminus group | |||||

| Total, No. | 189 | 43 | 60 | 84 | 65 |

| Mean (SD) | −0.42 (0.69) | −1.07 (0.76) | −0.30 (0.64) | −0.18 (0.44) | −0.45 (0.69) |

| Nonoverminus group | |||||

| Total, No. | 169 | 44 | 48 | 77 | 61 |

| Mean (SD) | −0.04 (0.46) | −0.16 (0.57) | −0.01 (0.41) | 0 (0.41) | −0.05 (0.66) |

| >1.00 D of SER myopic change from baseline to 12 mo, No./total No. (%) | |||||

| Overminus group | 33/189 (17) | 22/43 (51) | 8/60 (13) | 3/84 (4) | 12/65 (18) |

| Nonoverminus group | 2/169 (1) | 1/44 (2) | 1/48 (2) | 0/77 | 3/61 (5) |

| RR (95% CI)c | 13.3 (3.3-53.5) | 21.3 (2.9-157.9) | 6.5 (0.9-48.5) | NAd | 4.3 (1.1-16.3) |

| 24 mo | |||||

| SER at 24 mo | |||||

| Overminus group | |||||

| Total, No. | 57 | 10 | 23 | 24 | 51 |

| Mean (SD) | −0.58 (1.76) | −3.71 (1.27) | −0.50 (0.90) | 0.64 (0.54) | −0.38 (1.74) |

| Nonoverminus group | |||||

| Total, No. | 52 | 16 | 14 | 22 | 49 |

| Mean (SD) | −0.29 (1.60) | −2.12 (1.75) | 0.13 (0.35) | 0.77 (0.35) | −0.19 (1.58) |

| Change in SER from baseline to 24 mo, mean (SD)e | |||||

| Overminus group | |||||

| Total, No. | 57 | 10 | 23 | 24 | 20 |

| Mean (SD) | −0.61 (0.94) | −1.81 (0.76) | −0.60 (0.88) | −0.01 (0.54) | −0.51 (0.72) |

| Nonoverminus group | |||||

| Total, No. | 52 | 16 | 14 | 22 | 17 |

| Mean (SD) | −0.14 (0.65) | −0.50 (0.99) | 0.01 (0.33) | 0.03 (0.34) | 0.18 (0.84) |

| >1.00 D of SER myopic change from baseline to 24 mo, No./total No. (%) | |||||

| Overminus group | 14/57 (25) | 8/10 (80) | 6/23 (26) | 0/24 | 3/20 (15) |

| Nonoverminus group | 4/52 (8) | 4/16 (25) | 0/14 | 0/22 | 0/17 |

| RR (95% CI)d | 3.9 (1.6-9.3) | 2.9 (1.2-6.9) | NAd | NAd | NAd |

| Change in SER from 12 to 24 mo, mean (SD)f | |||||

| Overminus group | |||||

| Total, No. | 57 | 10 | 23 | 24 | 33 |

| Mean (SD) | −0.20 (0.55) | −0.75 (0.51) | −0.23 (0.50) | 0.06 (0.44) | −0.09 (0.66) |

| Nonoverminus group | |||||

| Total, No. | 52 | 16 | 14 | 22 | 28 |

| Mean (SD) | −0.07 (0.45) | −0.22 (0.59) | −0.03 (0.41) | 0.01 (0.33) | 0.04 (0.46) |

| 36 mo | |||||

| SER at 36 mo, mean (SD) | |||||

| Overminus group | |||||

| Total, No. | 112 | 19 | 43 | 48 | 102 |

| Mean (SD) | −0.72 (1.79) | −3.83 (1.53) | −0.64 (0.99) | 0.36 (0.75) | −0.74 (1.92) |

| Nonoverminus group | |||||

| Total, No. | 91 | 29 | 25 | 37 | 84 |

| Mean (SD) | −0.56 (1.67) | −2.32 (1.71) | −0.19 (0.78) | 0.57 (0.62) | −0.50 (1.74) |

| Change in SER from baseline to 36 mo, mean (SD)e | |||||

| Overminus group | |||||

| Total, No. | 112 | 19 | 43 | 48 | 38 |

| Mean (SD) | −0.74 (1.00) | −1.86 (1.01) | −0.69 (0.96) | −0.35 (0.70) | −0.83 (0.95) |

| Nonoverminus group | |||||

| Total, No. | 91 | 29 | 25 | 37 | 30 |

| Mean (SD) | −0.44 (0.85) | −0.93 (1.07) | −0.26 (0.67) | −0.18 (0.57) | −0.20 (1.03) |

| >1.00 D of SER myopic change from baseline to 36 mo, No./total No. (%) | |||||

| Overminus group | 30/112 (27) | 14/19 (74) | 13/43 (30) | 3/48 (6) | 13/38 (34) |

| Nonoverminus group | 14/91 (15) | 8/29 (28) | 3/25 (12) | 3/37 (8) | 3/30 (10) |

| RR (95% CI)c | 1.8 (1.0-3.0) | 2.6 (1.3-5.1) | 2.5 (0.8-7.6) | 0.7 (0.2-3.4) | 4.0 (1.1-14.0) |

| Change in SER from 12 to 36 mo, mean (SD)g | |||||

| Overminus group | |||||

| Total, No. | 112 | 19 | 43 | 48 | 63 |

| Mean (SD) | −0.34 (0.67) | −0.76 (0.75) | −0.35 (0.70) | −0.15 (0.55) | −0.39 (0.89) |

| Nonoverminus group | |||||

| Total, No. | 91 | 29 | 25 | 37 | 52 |

| Mean (SD) | −0.36 (0.66) | −0.69 (0.82) | −0.22 (0.56) | −0.20 (0.46) | −0.27 (0.66) |

| Change in SER from 24 to 36 mo, mean (SD)h | |||||

| Overminus group | |||||

| Total, No. | 49 | 6 | 22 | 21 | 45 |

| Mean (SD) | −0.08 (0.41) | −0.02 (0.58) | −0.15 (0.44) | −0.02 (0.33) | −0.30 (0.85) |

| Nonoverminus group | |||||

| Total, No. | 48 | 15 | 14 | 19 | 45 |

| Mean (SD) | −0.26 (0.44) | −0.43 (0.50) | −0.14 (0.48) | −0.20 (0.32) | −0.24 (0.49) |

Abbreviations: D, diopter; NA, not applicable; RR, risk ratio; SER, spherical equivalent refractive error.

Subgroups exclude 2 ineligible participants who had an SER greater than 1.00 D at baseline (1.125 D and 1.25 D).

Overall treatment group difference of SER from cycloplegic autorefraction (overminus – nonoverminus) equal to −0.68 D (95% CI, −1.21 to −0.15) at 24 months and −0.66 D (95% CI, −1.15 to −0.17) at 36 months. Difference obtained from an analysis of covariance model adjusted for baseline refractive error in the most myopic eye. Ten participants at 24 months and 2 at 36 months were excluded from the analysis because of visits outside the analysis window.

RR reflects the relative probability of a participant in the overminus group having more than 1.00 D of myopic change compared with a participant in the nonoverminus group.

RR could not be calculated due to the denominator of 0 (ie, no participants in the nonoverminus group had >1.00 D of SER myopic change during the time period).

Overall treatment group difference of change in refractive error from baseline (overminus – nonoverminus) equal to −0.52 D (95% CI, −0.79 to −0.24; P < .001) at 24 months and −0.36 D (95% CI, −0.59 to −0.12; P = .003) at 36 months. The difference is obtained from an analysis of covariance model adjusted for baseline SER in the most myopic eye. Eleven participants at 24 months and 3 at 36 months were excluded from the analyses due to visits outside the analysis window. For participants whose 24-month visit was outside the analysis window, the 18-month SER was used instead, if available and if completed within the 24-month window.

Overall treatment group difference of change in SER from 12 months to 24 months (overminus – nonoverminus) equal to −0.15 D (95% CI, −0.33 to 0.03). Difference obtained from an analysis of covariance model adjusted for baseline SER in the most myopic eye. Eleven participants were excluded from the analysis due to visits outside the analysis window at 24 months.

Overall treatment group difference of change in SER from 12 months to 36 months (overminus – nonoverminus) equal to −0.001 D (95% CI, −0.18 to 0.18). Difference obtained from an analysis of covariance model adjusted for baseline SER in the most myopic eye. Three participants were excluded from the analysis due to visits outside the analysis window at 36 months.

Overall treatment group difference of change in SER from 24 months to 36 months (overminus – nonoverminus) equal to 0.16 D (95% CI, −0.02 to 0.34). Difference obtained from an analysis of covariance model adjusted for baseline SER in the most myopic eye. Eleven participants were excluded from the analysis due to visits outside the analysis window at 24 months.

At 24 months, 14 of 57 overminus participants (25%) had more than 1.00 D of myopic shift compared with 4 of 52 (8%) assigned to nonoverminus treatment (adjusted RR, 3.9; 95% CI, 1.6-9.3; P = .002). At 36 months, 30 of 112 (26.8%) in the overminus group had more than 1.00 D of myopic shift compared with 14 of 91 (15%) in the nonoverminus group (adjusted RR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.0-3.0; P = .045) (Table 2). Based on baseline SER subgroups, RRs for developing more than 1.00 D myopic shift over 3 years between the overminus and nonoverminus groups were 2.6 (95% CI, 1.3-5.1) for participants with baseline SER of −0.50 to −6.00 D, 2.5 (95% CI, 0.8-7.6) for those with baseline SER of −0.375 to 0.375 D, and 0.7 (95% CI, 0.2-3.4) for those with baseline SER 0.50 to 1.00 D (Table 2). The RR was 1.8 (95% CI, 1.0-3.2) in the sensitivity analysis using baseline myopia defined −6.00 D or less.

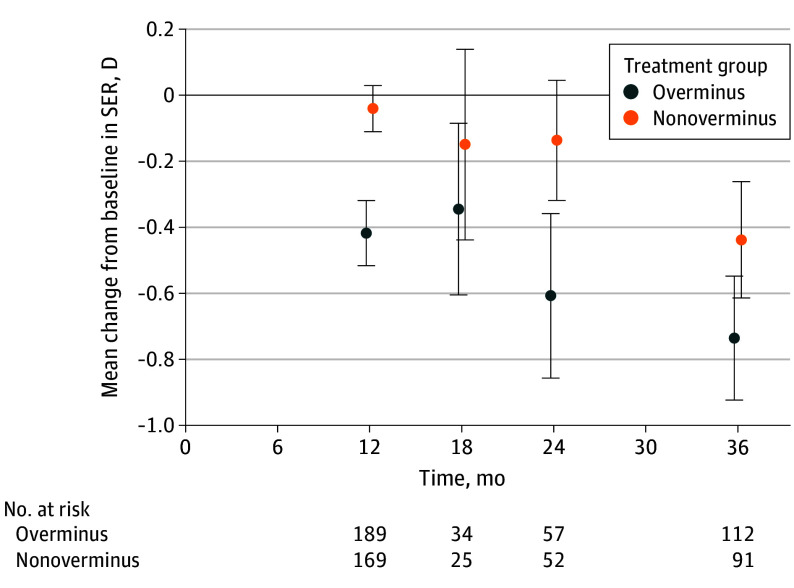

Between 12 and 36 months, there was no difference in mean (SD) myopic shift between the overminus and nonoverminus groups (−0.34 [0.67] D in the overminus group and −0.36 [0.66] D in the nonoverminus group; adjusted difference, −0.001 D; 95% CI, −0.18 to 0.18; P = .99). The mean (SD) myopic shift was −0.20 (0.55) D in the overminus group and −0.07 (0.45) D in the nonoverminus group from 12 to 24 months and −0.08 (0.41) D and −0.26 (0.44) D, respectively, from 24 to 36 months (Table 2). Mean SER change between baseline and each time point was similar in participants who completed the visit being analyzed (ie, regardless of which other follow-up visits were completed) (Figure 2) and in the subset of participants who completed both the 24-month and 36-month visits (eFigure 1 in Supplement 3).

Figure 2. Mean Change in Spherical Equivalent Refractive Error (SER) by Treatment Group Over 36 Months.

The change from baseline in SER (diopters [D]) are shown at each visit by treatment group. Participants in the overminus group received full treatment (spectacles of −2.50 D) from months 0 to 12, half treatment (spectacles of −1.25 D) from months 12 to 15, and no treatment from months 15 to 18. Treatment was at investigator discretion from months 18 to 36 for participants in both the overminus and nonoverminus groups. The number of participants at 18 months was smaller because the cycloplegic refraction was implemented for the remaining 18-month visits after the discontinuation of overminus lenses, which was 2 years and 10 months after the randomized clinical trial commenced (10 months after enrollment ended) after the data and safety monitoring committee observed greater myopic shift over 12 months in the overminus group. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Cycloplegic autorefraction measurements of change in SER from baseline were available for 37 of 109 (33.9%) and 68 of 205 (33.2%) who completed the 24-month and 36-month visits, respectively. The SER changes by cycloplegic autorefraction were similar to those by cycloplegic retinoscopy (Table 2).

Biometry Measures (Secondary Outcomes)

Axial length data were available for 84 of 109 participants (77.1%) at 24 months and 162 of 205 (79.0%) at 36 months. Mean (SD) axial length was not significantly different between treatment groups at 24 months (overminus, 23.45 [1.09] mm; nonoverminus, 23.27 [0.88] mm; difference, 0.25 mm; 95% CI, −0.37 to 0.86; P = .63) or 36 months (overminus, 23.66 [1.11] mm; nonoverminus, 23.41 [0.87] mm; adjusted difference, 0.24 mm; 95% CI, −0.17 to 0.65; P = .58) (Table 3). There were no significant treatment group differences for flat corneal curvature, anterior chamber depth, or lens thickness at 24 or 36 months (Table 3).

Table 3. Biometry Measures at 24 and 36 Months From Randomization.

| Measure | 24 mo | 36 mo | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Baseline SER subgroupsa | Overall | Baseline SER subgroupsa | |||||||||||||

| −0.50 to −6.00 D | −0.375 to 0.375 D | 0.50 to 1.00 Db | −0.50 to −6.00 D | −0.375 to 0.375 D | 0.50 to 1.00 Db | |||||||||||

| Overminus | Nonoverminus | Overminus | Nonoverminus | Overminus | Nonoverminus | Overminus | Nonoverminus | Overminus | Nonoverminus | Overminus | Nonoverminus | Overminus | Nonoverminus | Overminus | Nonoverminus | |

| Axial length | ||||||||||||||||

| Total, No. | 40 | 44 | 5 | 15 | 16 | 12 | 19 | 17 | 86 | 76 | 17 | 26 | 32 | 23 | 35 | 26 |

| Mean (SD), mm | 23.45 (1.09) | 23.27 (0.88) | 25.04 (1.49) | 23.86 (0.88) | 23.48 (0.82) | 22.94 (0.93) | 23.02 (0.78) | 22.98 (0.58) | 23.66 (1.11) | 23.41 (0.87) | 24.94 (1.03) | 23.99 (0.78) | 23.61 (0.89) | 23.24 (0.87) | 23.11 (0.84) | 23.00 (0.66) |

| Median (range), mm | 23.16 (21.69 to 27.43) | 23.25 (21.43 to 25.92) | 24.70 (23.79 to 27.43) | 23.73 (22.77 to 25.92) | 23.30 (22.23 to 25.00) | 22.85 (21.43 to 24.55) | 23.00 (21.69 to 24.76) | 22.96 (21.89 to 24.07) | 23.52 (21.90 to 27.53) | 23.35 (21.69 to 25.47) | 24.84 (23.22 to 27.53) | 23.83 (22.76 to 25.47) | 23.45 (22.18 to 25.67) | 23.19 (21.69 to 24.86) | 22.93 (21.90 to 24.78) | 22.96 (21.88 to 24.31) |

| Treatment group difference, mean (95% CI)c | 0.25 (−0.37 to 0.86) | NA | NA | NA | 0.24 (−0.17 to 0.65) | NA | NA | NA | ||||||||

| P value | .63 | NA | NA | NA | .58 | NA | NA | NA | ||||||||

| Flat corneal curvature | ||||||||||||||||

| Total, No. | 37 | 39 | 5 | 15 | 14 | 10 | 18 | 14 | 77 | 68 | 16 | 24 | 31 | 21 | 29 | 23 |

| Mean (SD), D | 42.75 (1.62) | 43.23 (1.43) | 41.78 (2.00) | 42.95 (0.96) | 43.01 (1.55) | 43.61 (1.91) | 42.83 (1.57) | 43.27 (1.51) | 42.86 (1.77) | 43.09 (1.42) | 42.35 (2.06) | 42.79 (1.01) | 42.87 (1.65) | 43.04 (1.67) | 43.11 (1.77) | 43.46 (1.51) |

| Median (range), D | 42.99 (38.84 to 46.29) | 43.29 (40.25 to 47.02) | 42.33 (38.84 to 43.67) | 43.16 (41.11 to 44.49) | 43.05 (39.35 to 46.29) | 43.67 (40.61 to 47.02) | 42.70 (40.04 to 46.08) | 43.37 (40.25 to 45.70) | 43.09 (37.80 to 46.67) | 43.07 (40.13 to 46.97) | 42.95 (37.80 to 45.79) | 42.97 (40.61 to 45.25) | 42.83 (38.40 to 46.67) | 42.53 (40.56 to 46.97) | 43.15 (40.02 to 46.43) | 43.72 (40.13 to 45.86) |

| Treatment group difference, mean (95% CI)c | −0.57 (−1.58 to 0.44) | NA | NA | NA | −0.20 (−0.90 to 0.49) | NA | NA | NA | ||||||||

| P value | .58 | NA | NA | NA | .63 | NA | NA | NA | ||||||||

| Anterior chamber depth | ||||||||||||||||

| Total, No. | 33 | 38 | 5 | 13 | 13 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 78 | 68 | 16 | 24 | 27 | 20 | 33 | 23 |

| Mean (SD), mm | 3.74 (0.26) | 3.72 (0.30) | 3.90 (0.26) | 3.79 (0.11) | 3.81 (0.26) | 3.75 (0.16) | 3.62 (0.23) | 3.65 (0.45) | 3.67 (0.29) | 3.70 (0.26) | 3.79 (0.31) | 3.76 (0.21) | 3.69 (0.26) | 3.65 (0.26) | 3.58 (0.26) | 3.70 (0.29) |

| Median (range), mm | 3.71 (3.24 to 4.20) | 3.74 (3.00 to 4.69) | 3.88 (3.57 to 4.20) | 3.78 (3.61 to 4.03) | 3.79 (3.35 to 4.17) | 3.75 (3.55 to 3.99) | 3.59 (3.24 to 4.08) | 3.60 (3.00 to 4.69) | 3.68 (3.13 to 4.32) | 3.71 (3.15 to 4.47) | 3.81 (3.15 to 4.27) | 3.79 (3.33 to 4.33) | 3.65 (3.13 to 4.24) | 3.64 (3.15 to 4.03) | 3.57 (3.18 to 4.03) | 3.64 (3.29 to 4.47) |

| Treatment group difference, mean (95% CI)c | 0.02 (−0.17 to 0.20) | NA | NA | NA | −0.03 (−0.15 to 0.08) | NA | NA | NA | ||||||||

| P value | .81 | NA | NA | NA | .63 | NA | NA | NA | ||||||||

| Lens thickness d | ||||||||||||||||

| Total, No. | 20 | 22 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 9 | 9 | 46 | 35 | 11 | 16 | 13 | 9 | 20 | 9 |

| Mean (SD), mm | 3.39 (0.14) | 3.41 (0.13) | 3.40 (0.18) | 3.41 (0.10) | 3.37 (0.15) | 3.41 (0.12) | 3.41 (0.13) | 3.42 (0.17) | 3.40 (0.12) | 3.42 (0.18) | 3.41 (0.12) | 3.39 (0.15) | 3.40 (0.13) | 3.44 (0.12) | 3.39 (0.12) | 3.38 (0.15) |

| Median (range), mm | 3.43 (3.18 to 3.67) | 3.40 (3.21 to 3.70) | 3.38 (3.22 to 3.67) | 3.41 (3.24 to 3.56) | 3.37 (3.18 to 3.55) | 3.42 (3.27 to 3.55) | 3.44 (3.22 to 3.57) | 3.34 (3.21 to 3.70) | 3.40 (3.14 to 3.68) | 3.42 (2.98 to 4.10) | 3.40 (3.25 to 3.68) | 3.41 (2.98 to 3.59) | 3.42 (3.14 to 3.60) | 3.46 (3.25 to 3.62) | 3.36 (3.22 to 3.65) | 3.34 (3.15 to 3.60) |

| Treatment group difference, mean (95% CI)c | −0.03 (−0.15 to 0.09) | NA | NA | NA | −0.02 (−0.11 to 0.07) | NA | NA | NA | ||||||||

| P value | .63 | NA | NA | NA | .63 | NA | NA | NA | ||||||||

Abbreviations: D, diopter; NA, not applicable; SER, spherical equivalent refractive error.

Treatment group differences were not calculated for baseline subgroups due to limited sample size.

Subgroups exclude 2 ineligible participants who had an SER greater than 1.00 D at baseline (1.125 D and 1.25 D).

Treatment group differences were obtained from an analysis of variance model; we could not adjust for the baseline values of each measure because biometry measures were not collected at baseline. 95% CIs and P values were adjusted to control the false discovery rate at 5%. A total of 9, 8, 7, and 5 participants were excluded from the analysis of axial length, flat corneal radius, anterior chamber depth, and lens thickness, respectively, due to visits outside the analysis window at 24 months. One participant was excluded from the analysis of axial length, flat corneal radius, and anterior chamber depth due to visits outside the analysis window at 36 months.

Lens thickness was only available at the subset of sites with measurement capabilities.

Exotropia Control, Exotropia Magnitude, and Near Stereoacuity (Exploratory Outcomes)

There were no significant treatment group differences for IXT control (distance or near), magnitude of exodeviation (distance or near), or near stereoacuity at 24 or 36 months (eTables 1 and 3 and eFigure 2 in Supplement 3).

Treatment Used During the Extension Study

Between 19 and 36 months, 15 of 124 (12.1%) in the overminus group and 13 of 99 (13%) in the nonoverminus group had surgery for their IXT. The percentages of participants who received other types of IXT treatments during this time were similar between the 2 groups (eTable 2 in Supplement 3), including overminus spectacles being restarted in 14 of 124 (11.3%) in the overminus group and being used for the first time in 11 of 99 (11%) in the nonoverminus group. Myopia control treatments were used in 2 of 124 (1.6%) and 1 of 99 (1%) in the overminus and nonoverminus groups, respectively (eTable 4 in Supplement 3).

Discussion

We previously reported a greater myopic shift over 1 year of overminus spectacles (−2.50 D) compared with nonoverminus spectacles in children with IXT aged 3 to 10 years.12 The current post-RCT extension study found that the treatment group difference of 0.37 D (95% CI, −0.49 to −0.26) in myopic shift at 1 year persisted but did not increase further during the 2 years after the start of weaning and discontinuation of overminus treatment. Thus, the same treatment group difference initially observed at 12 months was still present at 3 years. These findings suggest that cessation of the original overminus lens treatment neither exacerbated nor lessened the myopic shift.

Previous studies on overminus lens treatment for IXT have not found a myopic shift greater than what would be considered age expected. A randomized trial11 evaluating −2.50-D overminus lenses combined with 4-∆ base-in prism in 60 children aged 3 to 6 years with IXT and hyperopia from 0.50 to 5.00 D found no significant change in refractive error in both treatment and observation groups at 1 year. In another RCT18,19 using an algorithm to customize overminus lens power based on the child’s distance exodeviation control and magnitude, accommodative convergence to convergence ratio, and refractive error showed no difference in refractive and biometric changes between the overminus (lens range of −1.00 to −6.25 D) and observation groups at 6 months in 84 children aged 4 to 15 years with IXT and refractive error between 3.00 and −6.00 D. There are numerous possible reasons for the discordant study results between our original RCT and these 2 RCTs, including differences in overminus lens power or prescribing strategy used, participant age, refractive error eligibility criteria, length of follow-up during and after treatment, and sample size. For example, neither of the other RCTs followed up with their participants after discontinuing overminus spectacles, and our study’s larger sample size resulted in higher statistical power to detect differences between treatment groups. Other studies8,19,20,21,22,23 of overminus spectacles are retrospective and without control groups and have concluded overminus spectacles are associated with no more than age-expected myopic shift.

In the current study, participants in the overminus group had approximately twice the risk of myopic progression greater than 1 D over 3 years vs those in the nonoverminus group. The difference in myopic shift between the overminus and nonoverminus groups was greatest in participants with baseline myopia (−0.50 to −6.00 D). Because myopia typically progresses within the age range of our participants, it was not surprising that both groups continued to progress in the myopic direction after treatment was discontinued. The myopia progression from 12 to 36 months in participants with myopia at baseline in both groups was comparable with the mean myopia progression in cohorts of children with myopia without IXT,24,25 suggesting temporary use of overminus spectacles does not accelerate myopia progression after discontinuing treatment.

The current leading theory for myopia progression is that peripheral hyperopic retinal defocus drives axial elongation26,27; however, this hypothesis is not universally accepted.28 The mechanism by which overminus lens treatment caused an increase in myopic shift in our study cohort with IXT is unknown. Children wearing overminus lenses need to accommodate to see clearly through the overminus lenses, and the more prolate eye shape induced by accommodation could lead to changes in relative peripheral refraction29 and faster myopia progression. Another speculation is that participants wearing overminus spectacles might exhibit greater accommodative lag, resulting in light being focused behind the retina during near work, which may act as a signal to increase eye growth and cause myopia progression.30 Although a previous study has shown that patients with myopia exhibit a larger accommodative lag than patients without myopia,31 other studies report that accommodative lag is unrelated to myopia progression.32,33,34,35 Because we did not measure peripheral refraction or accommodative accuracy in the present study, we cannot evaluate the association between these factors and myopic shift associated with overminus lens treatment.

Despite finding a greater mean myopic shift from baseline to 24 and 36 months in the overminus group, we found no statistically significant differences in axial length between treatment groups. However, because only approximately 40% of the original RCT participants had axial length measured, resulting in wide 95% CIs, we cannot exclude clinically meaningful differences between treatment groups. We did not measure axial length at baseline and 12 months, precluding us from adjusting this analysis for any potential baseline imbalances in axial length and from determining the axial length increase over time, which we would expect to be associated with a myopic shift. There were also no statistically significant differences between treatment groups for flat corneal curvature, anterior chamber depth, or lens thickness at 24 or 36 months.

The findings from our RCT and extension study suggest that children with IXT and baseline hyperopia of 0.50 to 1.00 D do not have significant risk for a myopic shift greater than 1.00 D with overminus lens treatment over 36 months. This finding is consistent with a RCT11 of combined overminus lens and base-in prism treatment for children with IXT and hyperopia, which reported similar mean (SD) refractive errors of 1.42 (1.25) D in the observation group (n = 30) and 1.43 (1.12) D in the combined treatment group (n = 28) at 12 months.

There were no differences in distance IXT control, exodeviation magnitude, or stereoacuity between treatment groups at 24 or 36 months. These findings are unsurprising given that the RCT found that the improved exotropia control shown after 12 months of overminus did not persist at 18 months.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Only 53% of the original RCT cohort completed the 36-month visit, which could result in selection bias if participants who completed the study differed from those who did not in known or unknown factors; nevertheless, baseline demographic and clinical characteristics and mean SER at 12 months appear similar between these groups. When the post-RCT extension study was initiated, nearly one-half the participants had already passed their 24-month visit window, contributing to smaller sample sizes at 24 months. However, the proportions of RCT participants completing the 24-month visit were similar between groups (57 of 196 [29.1%] in the overminus group and 52 of 190 [27.4%] in the nonoverminus group) and the proportions completing the final 36-month visit were similar between groups and nearly twice as high (112 [57.1%] in the overminus group and 93 [48.9%] in the nonoverminus group). Subgroup analyses should be interpreted with caution because of small sample sizes in baseline SER subgroups. Investigators performing cycloplegic retinoscopy were not masked to participants’ treatment assignments, potentially leading to bias; however, the subset with autorefraction showed similar results. Additionally, we did not collect biometry measures, particularly axial length, at baseline or 12 months, which limits the power of the analyses and precludes adjustment for potential confounding.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the myopic shift associated with 1 year of −2.50-D overminus lens treatment persisted 2 years after discontinuing overminus lens treatment. Both overminus and nonoverminus groups had similar myopic shift during the 2-year period after the start of treatment weaning and cessation. Over 3 years, 1 year of overminus treatment was associated with a 0.33-D increase in mean myopic shift and approximately twice the risk of having a myopic shift of 1.00 D or greater. The risk of myopic shift should be discussed when considering overminus lens treatment for children with IXT, particularly for those already myopic.

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eTable 1. IXT-Related Clinical Outcomes at 24 and 36 Months

eTable 2. Results From Sensitivity Analyses of Change in SE Refractive Error

eTable 3. Results From Sensitivity Analyses of Control and PACT

eTable 4. Treatment Used During the Extension Study

eFigure 1. Mean Change in Refractive Error by Treatment Group Over 36 Months (Limited to Participants Who Completed Both 24-Month and 36-Month Visits)

eFigure 2. Distance Exotropia Control by Treatment Group Over 36 Months

Group Information. Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Govindan M, Mohney BG, Diehl NN, Burke JP. Incidence and types of childhood exotropia: a population-based study. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(1):104-108. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.07.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chia A, Dirani M, Chan YH, et al. Prevalence of amblyopia and strabismus in young Singaporean Chinese children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(7):3411-3417. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKean-Cowdin R, Cotter SA, Tarczy-Hornoch K, et al. ; Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study Group . Prevalence of amblyopia or strabismus in Asian and non-Hispanic White preschool children: Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease study. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(10):2117-2124. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study Group . Prevalence of amblyopia and strabismus in African American and Hispanic children ages 6 to 72 months: the Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(7):1229-1236.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedman DS, Repka MX, Katz J, et al. Prevalence of amblyopia and strabismus in White and African American children aged 6 through 71 months: the Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(11):2128-2134.e1, 2. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.04.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Donaldson PJ, Kemp EG. An initial study of the treatment of intermittent exotropia by minus overcorrection. Br Orthopt J. 1991;48:41-43. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reynolds JD, Wackerhagen M, Olitsky SE. Overminus lens therapy for intermittent exotropia. Am Orthopt J. 1994;44:86-91. doi: 10.1080/0065955X.1994.11982018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caltrider N, Jampolsky A. Overcorrecting minus lens therapy for treatment of intermittent exotropia. Ophthalmology. 1983;90(10):1160-1165. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(83)34412-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rowe FJ, Noonan CP, Freeman G, DeBell J. Intervention for intermittent distance exotropia with overcorrecting minus lenses. Eye (Lond). 2009;23(2):320-325. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6703057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodacre H. Minus overcorrection: conservative treatment of intermittent exotropia in the young child—a comparative study. Aust Orthopt J. 1985;22:9-17. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng Y, Jiang J, Bai X, Li H, Li N. A randomized trial evaluating efficacy of overminus lenses combined with prism in the children with intermittent exotropia. BMC Ophthalmol. 2021;21(1):73. doi: 10.1186/s12886-021-01839-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen AM, Erzurum SA, Chandler DL, et al. ; Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group . Overminus lens therapy for children 3 to 10 years of age with intermittent exotropia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021;139(4):464-476. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2021.0082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trial of Overminus Spectacle Therapy for Intermittent Exotropia (IXT5) . ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02807350. Updated June 3, 2022. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02807350

- 14.Mohney BG, Holmes JM. An office-based scale for assessing control in intermittent exotropia. Strabismus. 2006;14(3):147-150. doi: 10.1080/09273970600894716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hatt SR, Liebermann L, Leske DA, Mohney BG, Holmes JM. Improved assessment of control in intermittent exotropia using multiple measures. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152(5):872-876. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(3):199-200. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benjamini Y, Krieger AM, Yekutieli D. Adaptive linear step-up procedures that control the false discovery rate. Biometrika. 2006;93(3):491-507. doi: 10.1093/biomet/93.3.491 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ale Magar JB, Shah SP, Webber A, Sleep MG, Dai SH. Optimised minus lens overcorrection for paediatric intermittent exotropia: a randomised clinical trial. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2022;50(4):407-419. doi: 10.1111/ceo.14060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ale Magar JB, Shah SP, Dai S. Comparison of biometric and refractive changes in intermittent exotropia with and without overminus lens therapy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2023;107(10):1526-1531. doi: 10.1136/bjo-2022-321509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paula JS, Ibrahim FM, Martins MC, Bicas HE, Velasco e Cruz AA. Refractive error changes in children with intermittent exotropia under overminus lens therapy. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2009;72(6):751-754. doi: 10.1590/S0004-27492009000600002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rutstein RP, Marsh-Tootle W, London R. Changes in refractive error for exotropes treated with overminus lenses. Optom Vis Sci. 1989;66(8):487-491. doi: 10.1097/00006324-198908000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kushner BJ. Does overcorrecting minus lens therapy for intermittent exotropia cause myopia? Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117(5):638-642. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.5.638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abri Aghdam K, Zand A, Soltan Sanjari M, Khorramdel S, Asadi R. Overminus lens therapy in the management of children with intermittent exotropia. J Curr Ophthalmol. 2021;33(1):36-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walline JJ, Walker MK, Mutti DO, et al. ; BLINK Study Group . Effect of high add power, medium add power, or single-vision contact lenses on myopia progression in children: the BLINK randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324(6):571-580. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones-Jordan LA, Sinnott LT, Cotter SA, et al. ; CLEERE Study Group . Time outdoors, visual activity, and myopia progression in juvenile-onset myopes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(11):7169-7175. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith EL III, Hung LF, Huang J. Relative peripheral hyperopic defocus alters central refractive development in infant monkeys. Vision Res. 2009;49(19):2386-2392. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2009.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benavente-Pérez A, Nour A, Troilo D. Axial eye growth and refractive error development can be modified by exposing the peripheral retina to relative myopic or hyperopic defocus. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(10):6765-6773. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-14524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brennan NA, Cheng X. Commonly held beliefs about myopia that lack a robust evidence base. Eye Contact Lens. 2019;45(4):215-225. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0000000000000566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Logan NS, Radhakrishnan H, Cruickshank FE, et al. IMI accommodation and binocular vision in myopia development and progression. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2021;62(5):4. doi: 10.1167/iovs.62.5.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gwiazda JE, Hyman L, Norton TT, et al. COMET Group. Accommodation and related risk factors associated with myopia progression and their interaction with treatment in COMET children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(7):2143-2151. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mutti DO, Hayes JR, Mitchell GL, et al. ; CLEERE Study Group . Refractive error, axial length, and relative peripheral refractive error before and after the onset of myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(6):2510-2519. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koomson NY, Amedo AO, Opoku-Baah C, Ampeh PB, Ankamah E, Bonsu K. Relationship between reduced accommodative lag and myopia progression. Optom Vis Sci. 2016;93(7):683-691. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weizhong L, Zhikuan Y, Wen L, Xiang C, Jian G. A longitudinal study on the relationship between myopia development and near accommodation lag in myopic children. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2008;28(1):57-61. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2007.00536.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Y, Drobe B, Zhang C, et al. Accommodation is unrelated to myopia progression in Chinese myopic children. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):12056. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-68859-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berntsen DA, Sinnott LT, Mutti DO, Zadnik K; CLEERE Study Group . Accommodative lag and juvenile-onset myopia progression in children wearing refractive correction. Vision Res. 2011;51(9):1039-1046. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2011.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eTable 1. IXT-Related Clinical Outcomes at 24 and 36 Months

eTable 2. Results From Sensitivity Analyses of Change in SE Refractive Error

eTable 3. Results From Sensitivity Analyses of Control and PACT

eTable 4. Treatment Used During the Extension Study

eFigure 1. Mean Change in Refractive Error by Treatment Group Over 36 Months (Limited to Participants Who Completed Both 24-Month and 36-Month Visits)

eFigure 2. Distance Exotropia Control by Treatment Group Over 36 Months

Group Information. Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group

Data Sharing Statement