Abstract

Purpose of this review:

Major adverse cardiac events (MACE) typically arise from non-flow-limiting coronary artery disease and not from flow-limiting obstructions that cause ischemia. This review elaborates the current understanding of the mechanism(s) for plaque development, progression, and destabilization and how identification of these high-risk features can optimally inform clinical management.

Recent findings:

Advanced invasive and non-invasive coronary imaging and computational post-processing enhance an understanding of pathobiologic/pathophysiologic features of coronary artery plaques prone to destabilization and MACE. Early investigations of high-risk plaques focused on anatomic and biochemical characteristics (large plaque burden, severe luminal obstruction, thin cap fibroatheroma morphology, and large lipid pool), but more recent studies underscore that additional factors, particularly biomechanical factors (low endothelial shear stress [ESS], high ESS gradient, plaque structural stress, and axial plaque stress), provide the critical incremental stimulus acting on the anatomic substrate to provoke plaque destabilization. These destabilizing features are often located in areas distant from the flow–limiting obstruction or may exist in plaques without any flow-limitation. Identification of these high-risk, synergistic plaque features enable identification of plaques prone to destabilize regardless of the presence or absence of a severe obstruction (Plaque Hypothesis).

Summary:

Local plaque topography, hemodynamic patterns, and internal plaque constituents constitute high-risk features that may be located along the entire course of coronary plaque, including both flow limiting and non-flow limiting regions. For coronary interventions to have optimal clinical impact it will be critical to direct their application to the plaque area(s) at highest risk.

Keywords: Endothelial shear stress, natural history of coronary artery disease, acute coronary syndrome, risk-prediction, atherosclerosis

INTRODUCTION:

Global Impact of Coronary Artery Disease

Despite improvements in therapies targeted at ameliorating coronary plaque pathobiological factors, and evolving interventions to reduce acute and chronic manifestations, coronary artery disease (CAD) remains the leading cause of mortality in both men and women(1). The epidemic of CAD is also becoming more frequent in underdeveloped nations as their diets become more Westernized and now affects younger people, and more women and individuals from a diverse range of ethnic backgrounds(2, 3). While ischemia-guided diagnostic and therapeutic approaches have represented the mainstay of CAD management, >50% of individuals’ initial clinical manifestation of CAD is the occurrence of myocardial infarction (MI) in the absence of antecedent symptoms. The mechanistic implications concerning the lack of symptoms preceding clinical CAD manifestations was recently underscored in the CONFIRM registry, involving 25,251 individuals without known CAD undergoing cardiovascular computed tomography angiography (CCTA) at baseline and at 3.4 year follow-up, where >75% of lesions that caused future cardiac events manifested only mild stenosis (<50% obstruction of coronary luminal diameter) before the event, and, therefore, did not cause clinical manifestations of myocardial ischemia(4). While stenosis-based and ischemia-based strategies have been utilized for many decades to characterize and treat patient risk, this approach has been unsuccessful to reduce cardiac events as evidenced in the recent landmark International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness with Medical and Invasive Approaches (ISCHEMIA) trial. A total of 5,179 patients with moderate or severe ischemia on stress testing were randomized to an initial invasive or conservative treatment strategy for managing stable ischemic heart disease, and clearly demonstrated that, although cardiac events were associated with more extensive CAD, there were no outcome benefits from revascularization of ischemia-producing luminal obstructions compared to medical therapy alone, except for improved reduction in angina(5). These findings emphasize the inadequacy of basing clinical management strategies on assessment of luminal stenosis and ischemia assessment alone (so-called “ischemia hypothesis”), and support, instead, the “plaque hypothesis,” which underscores that adverse CAD prognosis occurs as a function of local high-risk pathophysiologic, anatomic, biochemical, and biomechanical features located along the course of each coronary plaque(6).

REVIEW TEXT

Natural History of Plaque Development and Factors Responsible for Plaque Destabilization

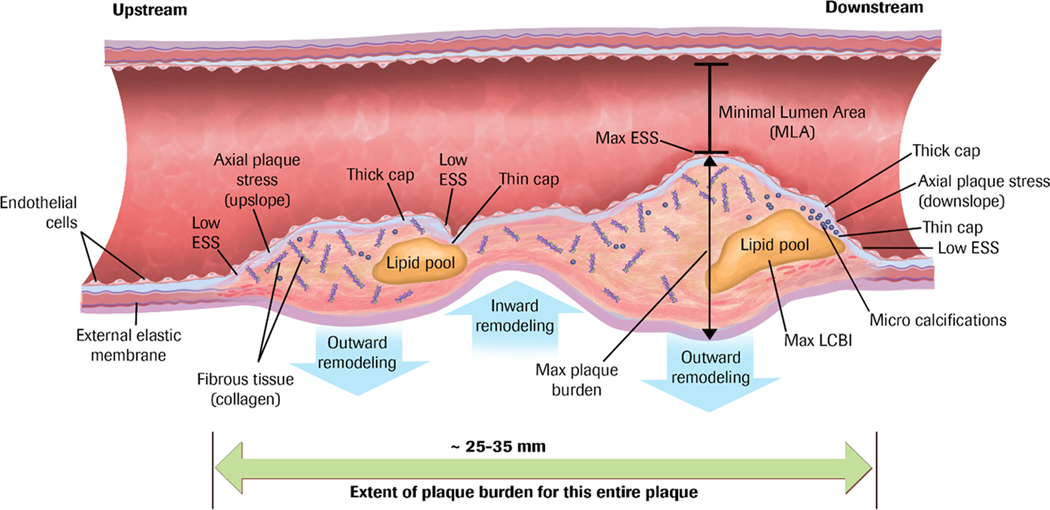

CAD is a highly dynamic, multifactorial, pathobiological process. Plaque buildup is a consequence of multiple hemodynamic, biomechanical, pro-inflammatory, pro-thrombotic, and lipid-related stimuli that adversely affect the arterial wall(7, 8), and primarily occurs as an episodic and stepwise process rather than a continuous one(9). Atherosclerotic plaques undergo complex and inter-related inflammatory and structural changes due to their local environment and the biomechanical forces acting on the plaque and the arterial wall such as endothelial shear stress (ESS)(defined as the frictional component of coronary blood flow along the endothelium lining the arterial wall). In a local microenvironment with low ESS, for example, pro-inflammatory, pro-atherogenic, and pro-thrombotic responses are triggered and result in plaque development, progression, and often repeated disruption(7, 10, 11). Autopsy studies(12) have identified high-risk morphologies of mainly ruptured plaques that display large plaque burden (PB), “spotty” calcifications, and lipid-rich necrotic cores enshrouded by a thin cap fibroatheroma (TCFA). Plaques that rupture are often large, located within the arterial wall, and often trigger compensatory positive or expansive remodeling to preserve flow in response to increasing local ESS from the plaque encroachment, and so these plaques may manifest only minor luminal encroachment(13, 14) and few, if any, manifestations of myocardial ischemia (Figure 1). These phenomena provide a mechanistic understanding of why a majority of individuals who experience future ACS do not manifest antecedent symptoms.

Figure 1. Coronary Atherosclerotic Plaque as a Complex, Lengthy, and Heterogeneous Pathobiologic Lesion.

Many different constituents, morphologies, and resultant pathobiologic and biomechanical environments localize spatially distant from the minimal lumen area.

ESS indicates endothelial shear stress; LCBI, lipid core burden index. Used with permission from Stone PH, et al.(6).

The goal of investigations to risk-stratify individual coronary plaques over recent years has been to identify the so-called “vulnerable plaque,” i.e., a high-risk plaque on a trajectory towards plaque destabilization and precipitation of a new clinical event, so that preemptive interventions could be utilized to interrupt that trajectory and avert the adverse event. Initial efforts focused on anatomic characterization of the plaque, but prognostication based on plaque anatomy features has consistently been inadequate to influence clinical decision-making(15, 16, 17, 18). The vast majority of plaques with ostensibly high-risk anatomic and biochemical features (large PB, small lumen area, TCFA morphology, and large lipid core burden index [LCBI]) do not destabilize and cause major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), as evident in the Providing Regional Observations to Study Predictors of Events in the Coronary Tree (PROSPECT) study, where less than 5% of all lesions with TCFA provoked a MACE during follow-up(17). Furthermore, combining high-risk anatomic features (large PB, small minimum lumen area [MLA], and TCFA morphology) predicted only 18.2–23.1% of MACE over 3.4 years by intravascular ultrasound (IVUS)(15, 17, 19), 18.9% by optical coherence tomography (OCT)(20), 19.3% by near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS)(21), and 4.1% by coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA)(22, 23).

More recent investigations consequently focused on complementary hemodynamic and biomechanical forces, computationally derived from invasive or non-invasive coronary imaging, that may influence plaque natural history, leading to incremental changes in plaque size, shape, or constituents that may culminate in destabilization. While local low ESS upregulates pro-inflammatory, pro-atherogenic, and pro-thrombotic properties of the endothelium(7), local high ESS may be associated with increased plaque vulnerability(24, 25, 26). The ESS gradient (ESSG), the ESS value of immediately adjacent plaque endothelial areas, has become increasingly appreciated as an important destabilizing pathobiologic force(27, 28) since it incorporates extremes of both low and high ESS in a single metric. Areas of sharp acceleration or deceleration manifest a high ESSG regardless of the absolute value of ESS. Thus, areas of low ESS, such as distal to an obstruction, or areas of high ESS, such as at an MLA, or even areas of circumferential or lateral ESS heterogeneity, may still manifest a high ESSG despite the differences in absolute ESS magnitude and direction(29). Multivariate analysis, for example, showed that the only 2 independent factors associated with plaque erosion were Max ESS and Max ESSG in any direction(27). The slope of plaque topography or axial plaque stress (APS), is another powerful, biomechanical, pathobiologic mechanism contributing to plaque destabilization, whether located upstream or downstream along the long axis of the plaque, or even circumferentially around the eccentric border of the plaque(27). In addition, the composition and spatial proximity of internal plaque constituents of different material properties can create physical inhomogeneities within the plaque that affect cellular function and modify the structural integrity of the plaque and foster disruption (plaque structural stress [PSS] or tensile stress)(6, 30, 31). Moreover, enlarged plaques can be afflicted by microruptures or leakage from immature neovessels and cause intraplaque haemorrhage that further drives lesion complications(32).

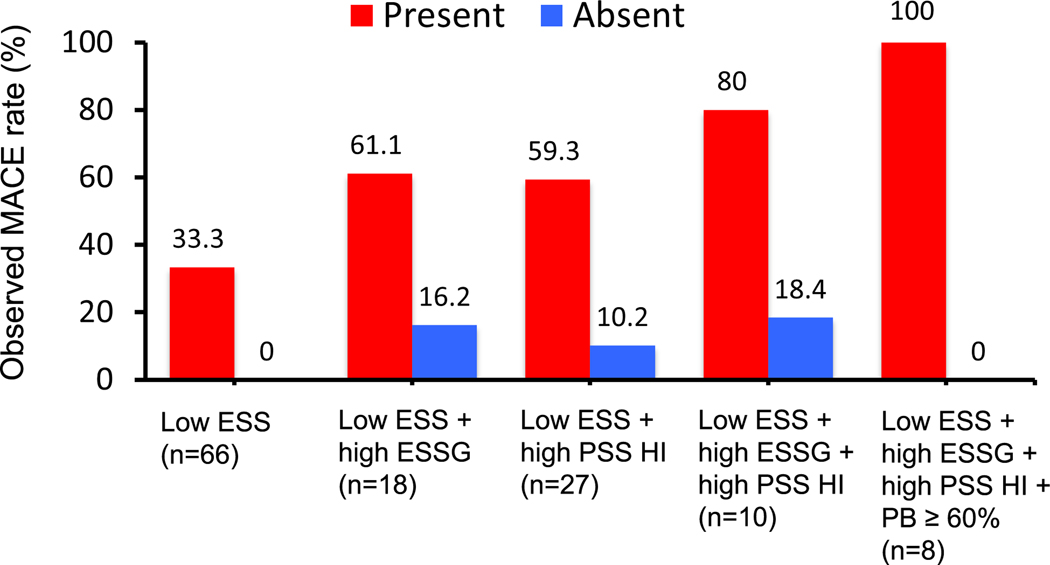

Recent studies have clearly demonstrated the additive or synergic prognostic effect of combining multidimensional risk features from plaque and lumen anatomy, biochemical constituents, and biomechanical forces external and internal to the plaque structure. In a proof-of-concept, post-hoc database study from the PROSPECT 1 study(22, 33), Ahmed et al identified an impressive and progressive escalation of prognostication from (i) low ESS alone, (ii) to low ESS/high ESSG, (iii) to low ESS/high PSS, (iv) to low ESS/high ESSG/high PSS, and (v) to low ESS/High ESSG/high PSS/high PB > 60%. (Figure 2) (33) They further identified that these distinct, but complementary, multidimensional metrics clustered within 1 mm of each other as they conspired to adversely destabilize a plaque and cause a MACE(33). It is clear that multiple adverse influences must be present to cause a “perfect storm” of characteristics, which occurs infrequently and only in a minority of ostensibly high-risk plaques. The current evidence underscores the urgent need of more sophisticated risk-prediction methods beyond evaluation of stenosis and anatomical high-risk plaque features alone.

Figure 2. Event rates associated with non-culprit lesions characterized by baseline low ESS, high ESSG, high PSS HI, and PB ≥ 60%.

Combined ESS, ESS gradient (ESSG) and plaque structural stress (PSS) heterogeneity index (HI), and high plaque burden, improves MACE prediction at 3 years follow-up. Abbreviations: ESS= endothelial shear stress, ESSG= ESS gradient, PSS= plaque structural stress, PSS HI= PSS heterogeneity index, PB= plaque burden. From Ahmed M, et al.(33).

Role of Heterogeneous and Complementary High-Risk Destabilizing Plaque Features in the Natural History of Individual Coronary Plaques

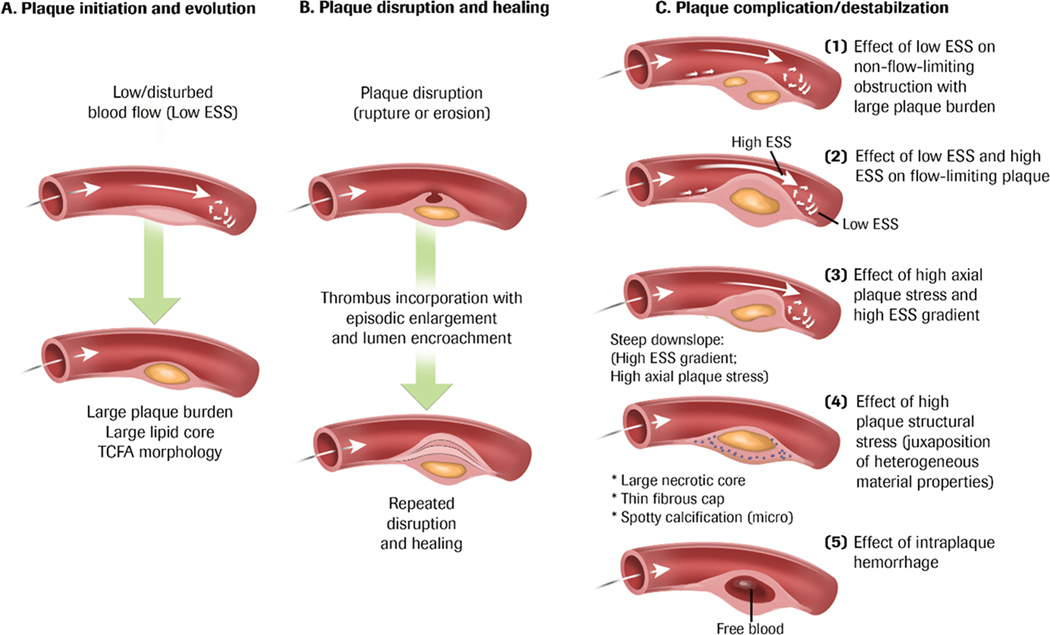

The various pathobiologic and pathophysiologic influences, and adverse outcomes, described above lend themselves to a clearer understanding of the heterogeneous natural history of CAD, and provide opportunities for more selective and directed therapeutic intervention (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Pathobiologic mechanisms of plaque progression and disruption.

(A) Plaque initiation begins in areas with local low and disturbed blood flow (i.e. ESS) and can be located anywhere along the course of the plaque. Low ESS is a pro-inflammatory and pro-atherogenic stimulus, and continued exposure to low ESS can lead to plaque progression with accumulation of lipids and thinning of the fibrous cap (TCFA). (B) Plaques can progress in a stepwise manner to destabilization (rupture, superficial erosion, or calcium nodule eruption) followed by thrombosis. Repeated destabilization and the healing response to disruption including thrombus resorption can lead to progressive plaque fibrosis, constrictive remodelling, and encroachment into the lumen. (C) Plaque progression and disruption is a multifactorial process and a consequence of the local environment exerted on the plaque. 1. Non-flow limiting plaques exposed to pro-inflammatory low ESS can exhibit features of high plaque burden and elaboration of matrix-degrading metalloproteases that promotes fragility of the fibrous cap and internal plaque structures that can lead to thrombotic events. 2. Plaques that encroaches into the lumen exhibits high ESS at the throat of the obstruction and low ESS either up or downstream from the minimal luminal area, and similarly, destabilizes the plaque. 3. High ESS gradients, which represent abrupt large differences in the magnitude of ESS in immediately adjacent endothelial cells, or steep plaque upslope/downslope, with or without associated high ESS, will increase axial plaque stress and promote plaque disruption. 4. The composition and spatial proximity of internal plaque constituents of different material properties can create inhomogeneities that affect cellular function and modify the structural integrity of the plaque and foster disruption (plaque structural stress). 5. Microruptures of the plaque cap or leaking from immature and leaky vasa vasorum within an enlarging plaque, can cause intraplaque haemorrhage and drive local oxidative stress, further promoting lesion complication. Used with permission from Stone PH, et al.(6).

Low ESS along the course of naturally occurring curvature of coronary artery contours is associated with plaque development, progression, and destabilization and may ultimately culminate as plaque rupture, erosion, or calcified nodule eruption with subsequent thrombosis(18, 34). Repeated destabilization and healing of the plaque, including thrombus resorption, can result in progressive plaque fibrosis, constrictive remodeling, and encroachment into the lumen, creating a focal obstruction to coronary blood flow. Ongoing exposure to local low ESS up- or downstream adjacent to the focal obstruction along the evolving plaque initiates focal pro-inflammatory responses followed by lipid accumulation and elaboration of matrix-degrading metalloproteinases in a vicious cycle that increase the fragility of plaque structures and promote formation of TCFA which may increase the risk of plaque rupture (Figure 3). These events may occur in a portion of the plaque that is not significantly encroaching into the lumen or even in a plaque without a luminal obstruction(35).

At the site of a luminal obstruction blood flow velocity and, therefore, local ESS, will always increase, according to basic principles of fluid flow, and the pathobiologic consequences of that high ESS are dependent on the absolute magnitude of the ESS and the adjacent variable plaque contours. Mild-moderately elevated ESS may be physiological and atheroprotective, prompting compensatory arterial expansive remodeling, while greater magnitudes of severely elevated ESS may lead to significant pathobiological responses(6). Highly variable physical manifestations of adjacent plaque topography and slope may lead to abrupt changes of ESS values along the course of the plaque that create focal pathological adjacent areas of very high and very low ESS, and consequently, increased ESSG(27, 28), which is a powerful destabilizing influence.

As the focal plaque evolves and progresses through many stages of repeated plaque inflammation and healing, the plaque interior physical characteristics inevitably evolve to include heterogeneous areas of active inflammation, lipid accumulation, necrotic cores, healed fibrosis, and focal calcification, which are measurable as PSS, as noted above. As these plaque constituents, and their physical properties and proximity, inexorably evolve over time, PSS becomes heterogeneous along the course of the plaque, and becomes a critical characteristic of plaque physical fragility and predisposition to destabilize, regardless of the magnitude of encroachment of the plaque into the lumen(22, 33, 36).

Of particular clinical importance, most of the high-risk anatomic, hemodynamic and biomechanical destabilizing features of low ESS, high ESSG, high PSS and high APS are spatially located distant from the minimal lumen area or throat of the obstruction(33), the typical site of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) deployment. Consequently, to understand the clinical risk of a particular plaque to destabilize and cause MACE, and, therefore, the value of ameliorating that individual plaque by a PCI, it is essential to understand the nature and location of the characteristics that may contribute to plaque progression and destabilization along the entire length of that plaque. Coronary interventions should be directed only to the portions of plaque at greatest risk.

Clinical Implications of the Plaque Hypothesis for Current and Future Management Strategies of Chronic CAD

While current diagnostic and treatment approaches focusing on the severity of coronary obstructions responsible for myocardial ischemia fail to prevent MACE, evolving experience from multiple methods of invasive and non-invasive coronary imaging, and post-processing of these images by computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and other computational techniques, identify plaque and arterial wall features that are fundamental to the risk of plaque destabilization and MACE. There is a compelling need now to incorporate these pathobiologic insights concerning the natural history of individual plaques and adjust our diagnostic and therapeutic strategies to characterize potential adverse features along the entire length of the atherosclerotic plaque, not just at the throat of the obstruction. This broader view of plaque risk, including both obstructive and non-obstructive lesions, is essential to adequately identify highest-risk areas to optimally deploy therapeutic strategies of PCI or local drug delivery to prevent MACE. Invasive imaging modalities of OCT, IVUS, and NIRS, and now non-invasive imaging methods of CCTA(37, 38, 39), provide the essential foundation of plaque and artery imaging, and strategies are under intense development to perform the computational post-processing at the diagnostic point-of-care to routinely and efficiently help inform clinical decision-making. It is anticipated that non-invasive CCTA risk-stratification of individual plaques may even be performed as broad screening of patients at high risk of developing CAD, such as those with extensive coronary risk factors, and could serve as a preliminary screen to identify those patients who may be best served with more detailed, invasive, assessment with coronary angiography and consideration of PCI. Non-invasive screening could also conceivably be performed in a serial manner over time to assess the dynamic evolution of coronary plaques.

Large clinical trials for clinical outcomes and for cost-benefit analyses will be needed to validate these plaque-based risk-assessment tools, and management strategies based on these tools, to treat the high-risk plaques. When high-risk patients and plaques are identified, treatment focusing on personalized preemptive interventions and optimizing medical therapy may significantly reduce the risk of future adverse cardiac outcomes.

Conclusion:

Enhanced risk stratification of individual plaques based on local plaque anatomy, blood flow patterns, constituents, topography, and other biomechanical metrics, will lead to widespread paradigm changes in diagnostic and therapeutic management of patients with CAD, and improve risk prediction beyond prognostication based on the presence of flow-limiting obstructions and consequent ischemia. Current assessment of plaque-based risk utilizes existing methods of invasive and non-invasive imaging, but require post-processing computational methods that are time-consuming, expensive, and not routinely available. Future advancements of both imaging and post-processing techniques will enable these high-risk features to be characterized in a more routine manner at the point-of-care around the world. Identification and treatment of high-risk plaque, both obstructive and non-obstructive, will be invaluable to optimize management of patients with, or at risk for, coronary atherosclerosis.

Key points:

Non-obstructive coronary lesions may harbor high-risk anatomical, biochemical, and biomechanical features that may precipitate a MACE.

The local adverse plaque environment of low ESS (either up- or downstream from the minimum lumen area), high ESS gradient, high plaque structural stress and its heterogeneity, and large plaque burden contribute to plaque progression and destabilization.

These pathobiologic and biomechanical phenomena expand the mechanistic understanding of why plaques destabilize and may be utilized to significantly improve application of coronary interventions to plaque areas at highest risk.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the team of the Vascular Profiling Laboratory at Brigham and Women’s Hospital for their contribution to the preparation of the manuscript.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was funded in part by National Institute of Health (US) grants R01 HL146144-01A1; RO1 HL140498; the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation (20200165), the Swedish Research Council (2021-00456), the Swedish Society of Medicine (SLS-961835), Erik and Edith Fernströms Foundation (FS-2021:0004), Karolinska Institutet (FS-2020:0007), the Sweden-America Foundation, and the Swedish Heart Foundation. We gratefully acknowledge the generous support of the Schaubert Family.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References:

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139(10):e56–e528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gulati R, Behfar A, Narula J, et al. Acute Myocardial Infarction in Young Individuals. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(1):136–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaduganathan M, Mensah GA, Turco JV, et al. The Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk: A Compass for Future Health. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80(25):2361–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang HJ, Lin FY, Lee SE, et al. Coronary Atherosclerotic Precursors of Acute Coronary Syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(22):2511–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maron DJ, Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, et al. Initial Invasive or Conservative Strategy for Stable Coronary Disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(15):1395–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stone PH, Libby P, Boden WE. Fundamental Pathobiology of Coronary Atherosclerosis and Clinical Implications for Chronic Ischemic Heart Disease Management-The Plaque Hypothesis: A Narrative Review. JAMA Cardiol. 2022. **This review highlights the current understanding of the pathobiological factors concerning the culprit region of the coronary atherosclerotic plaque that can cause future events (MACE). This review elucidates the new prognostication features which can determine the high-risk plaques suitable for pre-emptive intervention wherever its location in the coronary artery and regardless the degree of anatomical stenosis or Ischemia.

- 7.Chatzizisis YS, Coskun AU, Jonas M, et al. Role of endothelial shear stress in the natural history of coronary atherosclerosis and vascular remodeling: molecular, cellular, and vascular behavior. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(25):2379–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Majeed K, Bellinge JW, Butcher SC, et al. Coronary (18)F-sodium fluoride PET detects high-risk plaque features on optical coherence tomography and CT-angiography in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Atherosclerosis. 2021;319:142–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Libby P. Inflammation during the life cycle of the atherosclerotic plaque. Cardiovasc Res. 2021;117(13):2525–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ahmed M, Leistner DM, Hakim D, et al. A9504: Endothelial Shear Stress Metrics Correlate With Inflammatory Markers at the Culprit Site of Erosion in Patients With an Acute Coronary Syndrome: An OPTICO-ACS Substudy. American Heart Association Scientific Sessions; 30 Oct Chicago: 2022. *This study provides novel insights into the links between fluid hemodynamics, inflammatory markers, and mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of coronary plaque erosion. The manuscript is under preparation for submission to JACC: Basic to Translational Science.

- 11.Brown AJ, Teng Z, Evans PC, et al. Role of biomechanical forces in the natural history of coronary atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2016;13(4):210–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies MJ. Stability and instability: two faces of coronary atherosclerosis. The Paul Dudley White Lecture 1995. Circulation. 1996;94:2013–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glagov S, Weisenberg E, Zarins CK, et al. Compensatory enlargement of human atherosclerotic coronary arteries. N Engl J Med. 1987;316(22):1371–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clarkson TB, Prichard RW, Morgan TM, et al. Remodeling of coronary arteries in human and nonhuman primates. JAMA. 1994;271(4):289–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calvert PA, Obaid DR, O’Sullivan M, et al. Association between IVUS findings and adverse outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease: the VIVA (VH-IVUS in Vulnerable Atherosclerosis) Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4(8):894–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oemrawsingh RM, Cheng JM, Garcia-Garcia HM, et al. Near-infrared spectroscopy predicts cardiovascular outcome in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(23):2510–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stone GW, Maehara A, Lansky AJ, et al. A prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(3):226–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stone PH, Saito S, Takahashi S, et al. Prediction of progression of coronary artery disease and clinical outcomes using vascular profiling of endothelial shear stress and arterial plaque characteristics: the PREDICTION Study. Circulation. 2012;126(2):172–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng JM, Garcia-Garcia HM, de Boer SP, et al. In vivo detection of high-risk coronary plaques by radiofrequency intravascular ultrasound and cardiovascular outcome: results of the ATHEROREMO-IVUS study. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(10):639–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prati F, Romagnoli E, Gatto L, et al. Relationship between coronary plaque morphology of the left anterior descending artery and 12 months clinical outcome: the CLIMA study. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(3):383–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waksman R, Di Mario C, Torguson R, et al. Identification of patients and plaques vulnerable to future coronary events with near-infrared spectroscopy intravascular ultrasound imaging: a prospective, cohort study. Lancet. 2019;394(10209):1629–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gu SZ, Ahmed M, Huang Y, et al. A10038: Combined Low Endothelial Shear Stress and High Plaque Structural Stress Heterogeneity Predicts Non-Culprit Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events; Insights From the PROSPECT Study. Circulation. 2022;146:A10038. **This study showed, for the first time, the added value of destabilizing biomechanical plaque features of low endothelial shear stress (ESS), high ESS gradient and high plaque structural stress heterogeneity index in prediction of MACE. The manuscript is submitted to JAMA network Open.

- 23.Williams MC, Moss AJ, Dweck M, et al. Coronary Artery Plaque Characteristics Associated With Adverse Outcomes in the SCOT-HEART Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(3):291–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gijsen FJ, Mastik F, Schaar JA, et al. High shear stress induces a strain increase in human coronary plaques over a 6-month period. EuroIntervention. 2011;7(1):121–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samady H, Eshtehardi P, McDaniel MC, et al. Coronary artery wall shear stress is associated with progression and transformation of atherosclerotic plaque and arterial remodeling in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2011;124(7):779–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White SJ, Hayes EM, Lehoux S, et al. Characterization of the differential response of endothelial cells exposed to normal and elevated laminar shear stress. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226(11):2841–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hakim D, Pinilla-Echeverri N, Coskun AU, et al. The role of endothelial shear stress, shear stress gradient, and plaque topography in plaque erosion. Atherosclerosis. 2023;376:11–8. **This study showed the key role of ESS metrics: ESS, ESS gradient and the plaque topographical slope in the development of plaque erosion and may help prognosticate individual plaques at risk for future plaque erosion to select the suitable pre-emptive intervention.

- 28.Thondapu V, Mamon C, Poon EKW, et al. High spatial endothelial shear stress gradient independently predicts site of acute coronary plaque rupture and erosion. Cardiovasc Res. 2021;117(8):1974–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schirmer CM, Malek AM. Wall shear stress gradient analysis within an idealized stenosis using non-Newtonian flow. Neurosurgery. 2007;61(4):853–63; discussion 63–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown AJ, Teng Z, Calvert PA, et al. Plaque Structural Stress Estimations Improve Prediction of Future Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events After Intracoronary Imaging. Circulation Cardiovascular imaging. 2016;9(6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Costopoulos C, Huang Y, Brown AJ, et al. Plaque Rupture in Coronary Atherosclerosis Is Associated With Increased Plaque Structural Stress. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(12):1472–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jeney V, Balla G, Balla J. Red blood cell, hemoglobin and heme in the progression of atherosclerosis. Front Physiol. 2014;5:379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ahmed M, Gu SZ, Hakim D, et al. High-Risk Plaque Variables Low Endothelial Shear Stress, High Endothelial Shear Stress Gradient and High Plaque Structural Stress Co-localize in Coronary Plaques Responsible for Major Adverse Cardiac Events. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;81((8_Supplement) ):1156. **This study showed, for the first time, the spatial relationship among low endothelial shear stress (ESS), high ESS gradient and high plaque structural stress heterogeneity index, and their added value to anatomical features in prediction of MACE. These high-risk features frequently co-localize in plaques responsible for future MACE, and are substantially distant from the MLA. If adequately identified, highest-risk areas can be targeted by appropriate therapeutic strategies. The manuscript is submitted to JAMA network Open.

- 34.Stone PH, Maehara A, Coskun AU, et al. Role of Low Endothelial Shear Stress and Plaque Characteristics in the Prediction of Nonculprit Major Adverse Cardiac Events: The PROSPECT Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11(3):462–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wentzel JJ, Papafaklis MI, Antoniadis A, et al. Abstract 15270: Coronary Plaque Natural History Displays Marked Longitudinal Heterogeneity Along the Length of Individual Coronary Plaques. Circulation. 2020:A15270. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Costopoulos C, Maehara A, Huang Y, et al. Heterogeneity of Plaque Structural Stress Is Increased in Plaques Leading to MACE: Insights From the PROSPECT Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13(5):1206–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hakim D, Coskun AU, Maynard C, et al. Endothelial shear stress computed from coronary computed tomography angiography: A direct comparison to intravascular ultrasound. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2023. **This study showed that non-invasive calculation of high-risk endothelial shear stress metrics is feasible by CCTA and similar to IVUS. Identifying local flow patterns that are relevant to plaque development, progression, and destabilization by non-invasive modalities is a very attractive approach that is widely applicable in a population with chronic coronary artery disease as compared to invasive strategies.

- 38. Osborne-Grinter M, Kwiecinski J, Doris M, et al. Association of coronary artery calcium score with qualitatively and quantitatively assessed adverse plaque on coronary CT angiography in the SCOT-HEART trial. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;23(9):1210–21. *This study showed that in patients with stable chest pain, zero coronary artery calcium score (CACS) is associated with a good but not perfect prognosis, and CACS only cannot rule out non-obstructive plaque, or adverse plaque phenotypes, including low-attenuation plaque and expansile remodelling. Further supporting the concept of identifying better risk-markers of acute coronary syndrome.

- 39.van Rosendael AR, Shaw LJ, Xie JX, et al. Superior Risk Stratification With Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography Using a Comprehensive Atherosclerotic Risk Score. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(10):1987–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]