Abstract

Respiratory diseases, marked by structural changes in the airways and lung tissues, can lead to reduced respiratory function and, in severe cases, respiratory failure. The side effects of current treatments, such as hormone therapy, drugs, and radiotherapy, highlight the need for new therapeutic strategies. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) offers a promising alternative, leveraging its ability to target multiple pathways and mechanisms. Active compounds from Chinese herbs and other natural sources exhibit anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antitumor, and immunomodulatory effects, making them valuable in preventing and treating respiratory conditions. Ferroptosis, a unique form of programmed cell death (PCD) distinct from apoptosis, necrosis, and others, has emerged as a key area of interest. However, comprehensive reviews on how natural products influence ferroptosis in respiratory diseases are lacking. This review will explore the therapeutic potential and mechanisms of natural products from TCM in modulating ferroptosis for respiratory diseases like acute lung injury (ALI), asthma, pulmonary fibrosis (PF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), lung ischemia–reperfusion injury (LIRI), pulmonary hypertension (PH), and lung cancer, aiming to provide new insights for research and clinical application in TCM for respiratory health.

Keywords: TCM, Natural products, Ferroptosis, Respiratory diseases, Mechanism

Background

Respiratory diseases cover a broad spectrum, from upper respiratory tract infections to serious conditions like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, pulmonary fibrosis (PF), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), acute lung injury (ALI), lung ischemia–reperfusion injury (LIRI), pulmonary hypertension (PH), and lung cancer. These conditions, characterized by structural changes in airway and lung tissues and reduced respiratory function, pose significant health and economic burdens worldwide. Notably, COVID-19 caused 18 million deaths between 2020 and 2021, further emphasizing the global challenge of respiratory diseases [1]. COPD is the third leading cause of death globally [2], while ARDS and ALI account for no less than 4% of U.S. hospitalizations annually [3]. Lung cancer, leading in cancer-related deaths, saw 2.24 million new cases and 1.8 million fatalities in 2020, as reported by the International Agency for Research on Cancer [4]. Risk factors include smoking, air pollution, infections, and obesity [5]. Despite the availability of treatments like antibiotics and lung transplants, their side effects have prompted the search for innovative therapeutic approaches [6].

First introduced by Dixon et al. in 2012, ferroptosis is a form of programmed cell death (PCD), a term distinct from other modes of cell death such as necrosis, apoptosis, autophagy, necroptosis, and pyroptosis, which is essential for maintaining homeostatic balance [7–9]. Morphologically, ferroptosis features mitochondrial shrinkage, denser membranes, reduced mitochondrial cristae, with an intact cell membrane and normal-sized nucleus without chromatin condensation [10]. Biochemically, ferroptosis is triggered by the depletion of intracellular glutathione (GSH) and a decrease in the activity of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4). This imbalance leads to lipid peroxidation, which is further exacerbated by Fe2+ through the Fenton reaction, generating a high concentration of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [9, 11, 12]. Ferroptosis has been implicated in a variety of multi-systemic diseases, including neurological disorders, cancers, renal trauma, and notably, pulmonary diseases [13]. Numerous studies have substantiated its role in the pathogenesis and progression of lung diseases such as lung cancer, ALI, COPD, PF, asthma, and infections [14–19]. Studies have found that the ferroptosis inhibitor ferrostatin-1 can prevent pneumonia caused by P. aeruginosa (PAO1) infection [20]. In addition, PAO1 increases the mortality of irradiated mice by inhibiting the host anti-ferroptosis system GSH/GPX4 [19]. Consequently, targeting ferroptosis presents a promising avenue for the development of innovative therapies for lung diseases.

Rooted in foundational texts like the Huangdi Neijing and the Treatise on Febrile Diseases, TCM offers preventive and therapeutic solutions using natural products with diverse pharmacological actions, including anticancer [21], anti-inflammatory [22], antioxidant [23], and immunomodulatory actions [24]. Numerous investigations have documented the extensive utilization of natural products in the treatment of diverse conditions such as malignancies, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, immune-related disorders, and neurological ailments [25–28], gaining its advantage from its capacity to act through multiple targets, pathways, and mechanisms [29].

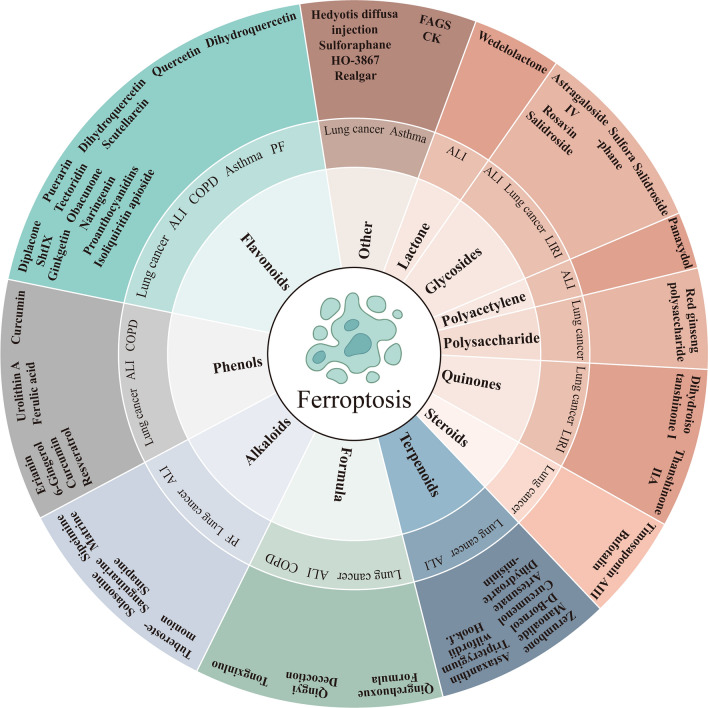

Research has increasingly focused on TCM's protective effects against lung diseases by modulating ferroptosis, involving compounds, such as terpenes, flavonoids, phenols, polysaccharides, etc. [17, 30–33]. This review aims to summarize the research on natural products in treating lung conditions, including lung cancer, ALI, asthma, COPD, PF, LIRI, and PH, emphasizing the modulation of ferroptosis and related signaling pathways, serving as a guide for TCM application in respiratory health.

The mechanism of ferroptosis

Iron metabolism in ferroptosis

Iron, essential for lipid peroxide (LPO) formation and ferroptosis initiation, plays a pivotal role in oxygen transport, mitochondrial electron transfer, DNA synthesis, and other key cellular activities [34, 35]. Iron homeostasis is pivotal for various physiological functions, with Fe2+ ions undergoing oxidation to Fe3+ and then binding to transferrin (TF) in the bloodstream to form Tf-Fe3+ complexes. These complexes, by interacting with the membrane protein transferrin receptor 1 (TFR1), facilitate the transport of iron to different storage sites, crucial for myriad cellular activities [36–38]. Silencing the transferrin receptor (TFRC) gene, which encodes TFR1, has been shown to inhibit erastin-induced iron depletion [39]. Both TF and TFRC play essential roles in the regulation of ferroptosis by promoting the cellular uptake of iron from the extracellular milieu. Furthermore, ferritin-targeted autophagy, or ferritinophagy, leads to lysosomal degradation of ferritin, releasing intracellular iron in unstable iron pools. Excessive free iron then accelerates lipid peroxidation and the Fenton reaction, ultimately resulting in ferroptosis [40]. The degradation of ferritin is accelerated either by activating a selective cargo receptor for ferritin autophagy, nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4), or by inhibiting the ferritin export protein, solute carrier family 40 member 1 (SLC40A1). The prostatic iron reductase six transmembrane epithelial antigen 3 (STEAP3) converts Fe3+ to Fe2+ in endosomes, facilitating iron transport to labile iron pools via divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) and storage in ferritin, a key cytoplasmic iron storage protein complex comprising ferritin light chain (FTL) and ferritin heavy chain 1 (FTH1) [41–43]. Under pathological conditions, ferritin releases excess Fe2+, which reacts with H2O2 in a Fenton reaction [44], producing hydroxyl radicals, increasing ROS, and leading to lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis initiation [45]. As a result, disruption of iron absorption, storage, utilization and efflux may lead to an imbalance in iron homeostasis, and elevated levels of Fe2+ lead to the generation of a substantial quantity of ROS, which disrupts intracellular redox balance, induces oxidative stress, initiates lipid peroxidation, and ultimately triggers ferroptosis [46–48].

Lipid peroxidation

Lipid metabolism is intricately linked to the onset and progression of ferroptosis. Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) possess bis-allylic hydrogen atoms that are readily abstracted, rendering them susceptible to lipid peroxidation. Key enzymes involved in lipid metabolism, such as arachidonic acid lipoxygenase 15 (ALOX15), acyl-CoA Synthetase long chain member 4 (ACSL4), and lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3), are requisite for the ferroptotic process. Initially, acyl-arachidonic acid (AA) and adrenaline (AdA) are activated by ACSL4 to form acyl-CoA derivatives. Subsequently, LPCAT3 esterifies these derivatives to phosphatidyl ethanolamine (PE), generating compounds like AA-PE and AdA-PE, which are finally oxidized to LPO by ALOX15 [8, 49]. Down-regulating the expression of ACSL4 and LPCAT3 genes in cellular systems can effectively inhibit the generation of LPO and enhance resistance to iron-induced cell death. Malondialdehyde (MDA) and 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) are produced during the degradation of LPO, which can be detrimental to the structure and function of proteins and nucleic acids, making it essential to reduce lipid peroxidation [50, 51]. In the presence of GPX4, toxic lipid hydroperoxides (L-OOH) were converted to non-toxic lipid alcohols (L-OH), which prevented Fe2+-dependent accumulation of lipid ROS on membrane lipids and inhibited the production of ferroptosis [52]. These fatty acids play a crucial role in the execution of ferroptosis; therefore, the quantity and distribution of PUFAs within cells are key determinants in the extent of lipid peroxidation and, consequently, the cell's susceptibility to ferroptosis [53].

Imbalance of the antioxidant system

GSH is a tripeptide composed of the amino acids glutamic acid (Glu), cysteine (Cys), and glycine (Gly), and serves as a crucial intracellular antioxidant [54]. A decline in GSH synthesis disrupts the intracellular redox balance, leading to the accumulation of peroxidized PUFAs. This inability to efficiently eliminate lipid peroxidation subsequently triggers ferroptosis. GSH synthesis is dependent on the cystine/glutamate antiporter system (system Xc −), a membrane-bound amino acid anti-transporter comprised of solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11) and solute carrier family 3 member 2 (SLC3A2) [55]. SLC7A11 functions as a cystine-glutamate anti-transporter. Under pathological conditions, inhibition of the system Xc − restricts the transport of cystine into the cell, thereby reducing cysteine synthesis and consequently diminishing GSH production. This leads to the depletion of GPX4, the generation of lipid ROS, and ultimately the onset of ferroptosis [56, 57]. GPX4, or phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase (PHGPX), is crucial in the glutathione (GSH) antioxidant system, converting GSH to glutathione disulfide (GSSG) and turning LPO into harmless lipid alcohols to prevent lipid peroxidation from ROS [8, 57]. Lower GPX4 levels increase ferroptosis risk, while higher levels protect against it [11]. Additionally, when cysteine is scarce, gamma-cysteine ligase's catalytic unit (GCLC) activates a GSH-independent defense by utilizing an alternative amino acid to prevent ferroptosis, highlighting a non-traditional pathway for maintaining antioxidant system equilibrium [58].

Other ways

Voltage-dependent anion channels (VDACs) are crucial for ion and metabolite transport across membranes and play a significant role in ferroptosis [59]. Erastin, a ferroptosis inducer, targets VDACs, causing mitochondrial dysfunction and a surge in ROS from mitochondria, leading to iron-dependent cell death [12]. Moreover, calcium overload can activate VDACs, increasing mitochondrial ROS and decreasing mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP). This triggers the expansion of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP), further contributing to mitochondrial dysfunction and ferroptosis [60, 61].

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is a critical regulator of cellular oxidative stress and controls the expression of various antioxidant genes, including heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH), and quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) [62]. Exposure to oxidative stress leads to increased nuclear accumulation and constitutive activation of Nrf2, which not only promotes tumor growth but also significantly contributes to treatment resistance in tumors [8]. Additionally, there is evidence that Nrf2 protects cells from ferroptosis through various pathways by regulating target genes like SLC7A11, GPX4, GSH, and ferritin [63, 64].

The tumor suppressor gene p53 indirectly influences ferroptosis by down-regulating SLC7A11, promoting its nuclear translocation [65]. Research indicates p53 pathways affect GPX4, GSH, and ROS levels, essential for ferroptosis [66]. Additionally, p53 targets the spermine/spermidine N1-acetyltransferase 1 (SAT1) enzyme, i.e., a catabolic rate-limiting enzyme, upregulating ALOX15, leading to lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis [67]. DMT1, functioning as a proton-coupled iron pump that transports iron to unstable iron pools through cell membrane potential differences, is upregulated by p53 to enhance ROS and induce ferroptosis in NSCLC [68].

Natural products for the treatment of respiratory diseases targeting ferroptosis

Lung cancer

Numerous studies have highlighted the role of ferroptosis in both the etiology and treatment of various forms of cancer, including but not limited to aggressive types such as breast cancer, liver cancer, stomach cancer, rectal cancer, glioma, and pancreatic cancer [69]. Targeting ferroptosis in the context of lung cancer has the potential to mitigate disease progression and metastasis, as well as to overcome, to some extent, the drug and radiation resistance commonly exhibited by lung cancer cells. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) constitutes the predominant subtype of lung cancer, accounting for approximately 85% of cases and encompassing squamous cell carcinoma, large cell carcinoma, and adenocarcinoma [70, 71]. Consequently, contemporary research on ferroptosis in lung cancer is primarily focused on NSCLC. Chemotherapy remains the principal treatment modality in the clinical management of NSCLC, with cisplatin being the most frequently employed chemotherapeutic agent [72]. However, the emergence of cisplatin resistance poses a significant challenge to achieving optimal therapeutic outcomes in patients undergoing chemotherapy for lung cancer. Natural products have gained prominence as a valuable adjunct in the comprehensive treatment of various malignancies. Besides, natural products have been shown to positively impact the quality of life and extend the survival duration of patients with advanced lung cancer, irrespective of whether conventional treatments are administered [73]. A summary of natural products used in lung cancer therapy, their primary sources, mechanisms of targeting ferroptosis, and main effects can be found in Table 1. Additionally, we analyzed and summarized the targets and signaling pathways of natural products targeting ferroptosis in the treatment of lung diseases, as shown in Figs. 1, 2.

Table 1.

Natural products targeting ferroptosis in lung cancer

| Component | Classification | Main roots | Test models | Dose | Mechanisms | Specific effects | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solasonine | Alkaloids | Solanum nigrum L. | Calu-1 and A549 cells | In vitro: 10, 15, 20 μM (calu-1); 20, 25, 30 μM (A549) | Causing GSH redox system imbalance and mitochondrial oxidative stress | Causing iron overload and redox imbalance; lipid peroxidation; mitochondrial damage; the destruction of the GSH redox system: decreasing expression of GPX4, SLC7A11, GSH, and Cys; MMP hyperpolarization | [74] |

| Erianin | Phenols | Dendrobium | H460 and H1299 cells; Balb/c nude mice |

In vitro: 12.5, 25, 50, 100 nm; In vivo: 100 mg/kg |

Inducing Ca2+/ CaM signal pathway | Promoting cell cycle arrest in G2/M; activating CAM and regulating L-type voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels; lipid peroxidation; promoting the production of ROS, MDA, TRF; decreasing expression of GPX4, CHAC2, SLC40A1, SLC7A11, HO-1, GSH | [75] |

| Diplacone | Flavonoids | Paulownia tomentosa mature fruit | A549 cells | In vitro: 40 μM | Increasing mitochondrial Ca2+ Influx and MPTP | Increasing the level of intracellular Ca2+, mitochondrial ROS, and mitochondrial Ca2+ overload; increasing the opening of the VDAC and MPTP; inducing loss of MMP; lipid peroxidation | [76] |

| Qingrehuoxue Formula | Formulas | Chinese herbal medicine | male Balb/c nude mice | In vivo: 15 g/kg | Upregulating P53 and GSK-3β and downregulating Nrf2 signal pathways | Increasing the levels of intracellular ROS, Fe2+, H2O2, GSH and MDA↑; decreasing the expression of SLC7A11, GPX4; shrunking mitochondria with increasing membrane density and decreasing or disappearing mitochondrial cristae | [78] |

| Bufotalin | Steroids | Venenum bufonis | A549 cells; male Balb/c nude mice |

In vitro: 4 μM; In vivo: 5/10 mg/kg |

Facilitating the ubiquitination and degradation of GPX4 | Increasing the level of lipid ROS, 4-HNE, MDA, Fe2 + ; decreasing the ratio of GSH/GSSG and NADPH/NADP + | [32] |

| Dihydroisotans-hinone I | Quinones | Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge | A549, H460 and IMR-90 cells; xenograft nude mice |

In vitro: 20–30 μM; In vivo: 30 mg/kg |

Blocking the protein expression of GPX4 | Increasing the level of lipid ROS and MDA; decreasing expression of GPX4 and GSH | [80] |

| Sanguinarine | Alkaloids | Sanguinaria canadensis Linn | A549 and H3122 cells; xenograft mice |

In vitro: 10 μM; In vivo: 5 mg/kg |

Decreasing the protein stability of GPX4 through E3 ligase STUB1-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of GPX4 | Increasing Fe2+ concentration, ROS level, and MDA content; decreasing GSH content | [81] |

| Red ginseng polysaccharide | Polysaccharides | Panax ginseng | A549 and MDA-MB-231 cells | In vitro: 200 μg/ml | Blocking the protein expression of GPX4 | Increasing the release of LDH and the level of lipid ROS; decreasing expression of GPX4 | [82] |

| Timosaponin AIII | Steroids | Anemarrhena Asphodeloides Bunge | H1299, A549, SPC-A1 and LLC cells; male C57BL/6 J or Balb/c- nude mice |

In vitro: 4 μM; In vivo: 12.5 mg/kg (low-dose), 50 mg/kg (high-dose) |

Facilitating HSP90 mediated GPX4 ubiquitination and degradation | Suppressing cell proliferation and migration, inducing G2/M phase arrest; increasing the levels of iron, lipid ROS, MDA, HMOX-1; decreasing expression of GSH, FTL, GPX4, SLC40A1, SLC7A11; inducing loss of MMP | [83] |

| Zerumbone | Terpenoids | Zingiber zerumbet rhizomes | HPAEpiC, A549, and H460 cell; BALB/c nude mice |

In vitro: 100 μM; In vivo: 20 mg/kg (low-dose), 40 mg/kg (high-dose) |

Downregulating AKT/STAT3/SLC7A11 axis | Increasing the level of MDA; decreasing the levels of GSH, GPX4 and SLC7A11 | [86] |

| S-3′-hydroxy-7′, 2′, 4′-Trimethoxyisoxane | Flavonoids | Dalbergia odorifera T. Chen | A549 and H460 cells; Balb/c nude mice |

In vitro: 16 μM; In vivo: – |

Inhibiting Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway | Increasing the level of Fe2 + , ROS and MDA; decreasing the levels of GSH, GPX4, p21, FTH1, Nrf2, HO-1; TEM: cell membrane rupture, mitochondrial shrinkage, thickening of the mitochondrial membrane density, and diminished or disappeared mitochondrial ridges | [88] |

| Ginkgetin | Flavonoids | Ginkgo biloba leaves | Xenograft nude mice |

In vitro: 5 μM; In vivo: 30 mg/kg |

Inhibiting Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway | Increasing labile iron pool and lipid peroxidation; decreasing expression of SLC7A11, GPX4, GSH; inducing loss of MMP | [89] |

| Manoalide | Terpenoids | Sponges | A549, H157, HCC827, and PC9 cells | In vitro: 15 μM | Suppressing the KRAS-ERK pathway and the Nrf2-SLC7A11 axis, mitochondrial Ca2 + overload induced-FTH1 pathways | Inducing ER stress; promoting the accumulation of lipid droplets, ROS, lipid peroxidation, mitochondria Ca2 + and iron; increasing the oxygen consumption rate and inhibiting mitochondria fatty acid oxidation; decreasing expression of Nrf2, SLC7A11, FTH1, GPX4, KRAS, P-ERK/ERK; increasing expression of NCOA4 and P-AMPK/AMPK | [90] |

| Hedyotisdiffusa injection | Other | Chinese herbal medicine | A549 and H1975 cells; Balb/c nude mice xenograft model |

In vitro: 30 μM (A549), 40 μM (H1975); In vivo: 15 mg/kg |

Regulating Bax/Bcl2/VDAC2/3 axis | Regulating VDAC2/3 activity by promoting Bax via inhibiting Bcl2; increasing the expression of 4-HNE, TFR, and HMOX1 | [91] |

| D-Borneol | Terpenoids | Cinnamomum cam phora (L.) J. Presl | H460/CDDP cells; Xenograft tumor mice |

In vitro: 2 μg/ml; In vivo: 30 mg/kg (low-dose), 60 mg/kg (high-dose) |

Promoting NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy | Increasing the level of ROS, MDA; decreasing expression of GSH, SOD, Trx, HO-1 | [92] |

| Artesunate | Terpenoids | Artemisinin | NCI-H1299, A549, LTEP-a-2, NCI-H23, and NCI-H358 cells | In vitro: 10/30 μM |

Inhibiting system Xc − and activating TFRC |

Increasing the ROS level and the mRNA level of TFRC; decreasing the protein level of VDAC and SLC7A11; | [93] |

| Dihydroartemisinin | Terpenoids | Artemisinin | NCI-H1299, A549, LTEP-a-2, NCI-H23, and NCI-H358 cells | In vitro: 10/30 μM |

Inhibiting system xc − and activating TFRC |

Increasing the ROS level and the mRNA level of TFRC; decreasing the protein level of VDAC and SLC7A11; | [93] |

| Curcumenol | Terpenoids | Wenyujin | CCD19, H1299, H460, BEAS-2B and 293 T cells |

In vitro: 300 μg/ml; In vivo: 200 mg/kg |

Suppressing lncRNA H19/miR-19b-3p/FTH1 axis | Increasing the level of iron, lipid ROS, HO-1, MDA, TF; decreasing the level of GSH, Nrf2, GPX4, SLC7A11, SLC40A1, FTH1 | [96] |

| Sulforaphane | Glycosides | Cruciferous vegetables | NCI-H69, NCI-H82 and NCI-H69AR cells | In vitro: 20 μM | Inhibiting system Xc − | Decreasing the level of SLC7A11, GSH; increasing the level of Fe2 + , lipid peroxidation | [97] |

| Sinapine | Alkaloids | Rapeseed and cruciferous plant species | A549, SK, H66, H460 and HBE cells | In vitro: 20 μM | Upregulating p-53,TF, TFRC; downregulating SLC7A11 | Increasing intracellular ferrous iron, lipid peroxidation, MDA and ROS; decreasing the expression of SLC7A11, GSH, GPX4 | [101] |

| HO-3867 | Other | Curcumin analogs | H460, PC-9, H1975, A549, H1299, A549 p53 KO cells and H460 p53 KO cells | In vitro: 40 μM | Activating the p53-DMT1 axis and suppressing GPX4 | Increasing the level of iron, ROS; increasing expression of P53, DMT1; decreasing expression of SLC7A11, GPX4 | [102] |

| 6-Gingerol | Phenols | Ginger | A549 and CCD19-Lu cells; Balb/c nude mice |

In vitro: 20, 40, 80 μM; In vivo: 0.25 mg/kg (low-dose), 0.5 mg/kg (high-dose) |

Inhibiting USP14-mediated Beclin1 ubiquitination, enhancing autophagy-dependent ferroptosis | Increasing level of MDA, iron and TfR1; decreasing level of USP14, FTH1, GPX4, ATF4, SOD; increasing autophagy related proteins level of Beclin- 1, NCOA4, LC3 I, LC3 II | [103] |

| Realgar | Other | Sulfide minerals | H23 cells | In vitro: 2 μg/ml | Suppressing the KRAS/Raf/MAPK pathway | Increasing the level of MDA, Fe2 + , ROS; decreasing expression of GSH; inducing loss of MMP | [106] |

| Curcumin | Phenols | Turmeric plant | A549 and H1299 cells; female C57BL/6 mice |

In vitro: 30 μM; In vivo: 100 mg/kg |

Activating autophagy-dependent ferroptosis | Increasing the level of iron, lipid peroxidation, ROS, MDA, IREB2, ACSL4; decreasing the level of SOD, GSH, SLC7A11, GPX4; inducing mitochondrial membrane rupture; decreasing mitochondrial cristae; increasing autolysosome; increasing autophagy related proteins level of Beclin1 and LC3, and decreasing the level of P62 | [108] |

| Resveratrol | Phenols | Peanuts, grapes, knotweed, mulberries | H520 cells | In vitro: 50 μmol/L; | Regulating SLC7A11-HMMR interaction, enhancing the cytotoxic effect of CD8 + T cells | Increasing the level of MDA, ACSL4, TFRC; decreasing the level of GPX4, SLC7A11, HMMR, GSH, and SOD; promoting the release of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-12, and IL-2; enhancing the cytotoxic effects of CD8 + T cells | [111] |

| Resveratrol | Phenols | Peanuts, grapes, knotweed, mulberries | BEAS-2B cells | In vitro: 10 μM; | Activating the Nrf2/Keap1 signaling pathway | Decreasing reactive oxygen species production and iron deposition; increasing the expression of GPX4 and GSH | [112] |

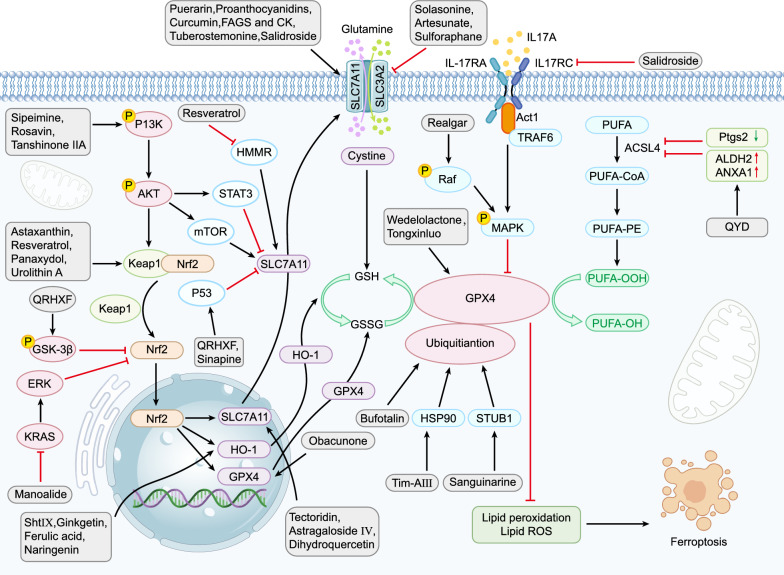

Fig. 1.

The role of SLC7A11-GSH-GPX4 axis in natural products—modulated ferroptosis in respiratory diseases. The modulations of ferroptosis by natural products in respiratory diseases are orchestrated through various mechanisms, prominently via GPX4-related pathways. These pathways crucially influence lipid peroxidation, an essential process in ferroptosis. Natural products up-regulate Nrf2 gene expression, stimulating its downstream target HO-1 and enhancing SLC7A11 protein expression. Consequently, GPX4 is activated either directly or indirectly, inhibiting ferroptosis. Moreover, multiple targets are involved in regulating the SLC7A11/GPX4 axis, including the activation of system Xc− , which facilitates GSH synthesis and GPX4 activation to modulate ferroptosis. On the contrary, ACSL4 overexpression catalyzes the oxidation of PUFAs into lipid hydroperoxides. These hydroperoxides are then converted into non-toxic lipid alcohols through GPX4 activation. In the context of the immune response, Interleukin IL-17 hinders GPX4, leading to induced ferroptosis. Notations: Black Arrow (↓): Indicates promotion. Red Rough Arrow (⟂): Indicates inhibition. Green Arrow: Indicates a decrease. Red Arrow: Indicates a increase.

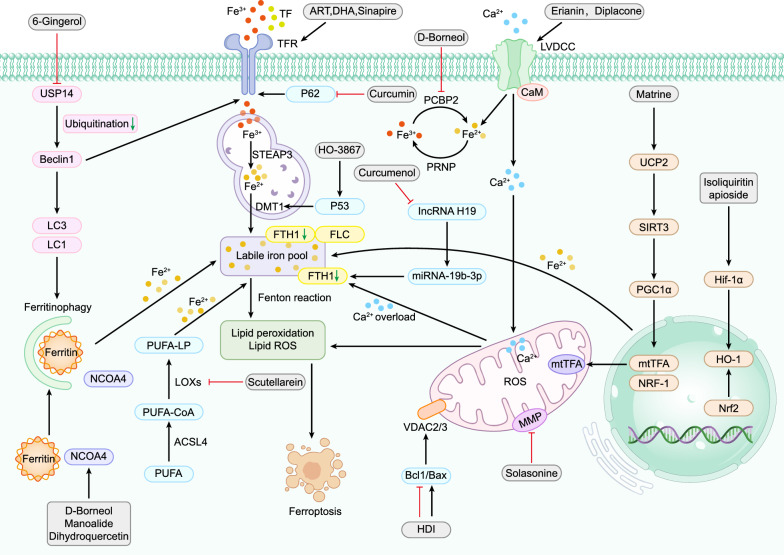

Fig. 2.

The role of iron metabolism in natural products—modulated ferroptosis in respiratory diseases. Iron metabolism is intimately linked with the mechanisms through which TCM modulates ferroptosis in respiratory diseases. An accumulation of a significant amounts of ferrous ions initiates the Fenton reaction, thereby enhancing lipid peroxidation, a pivotal step in inducing ferroptosis. Free iron binds with ferritin and is subsequently transported to the endosome through the transferrin receptor. Within the endosome, STEAP3 catalyzes the conversion of ferric iron into ferrous iron, which is then channeled into the labile iron pool via DMT1. The oxidation of PUFA coincides with the formation of ferrous ions. The influx of calcium ions causes mitochondrial calcium overload, leading to a substantial accumulation of ROS, the destruction of FLC, and FTH. These events culminate in the release of ferrous ions from the labile iron pools and the Fenton reaction, precipitating ferroptosis. Moreover, factors such as Nrf2, Hif-1α, HO-1, and mtTFA accentuate the increase of labile iron, while ferritophagy emerges as another pathway inducing ferroptosis. Notations: Black Arrows (↓): Indicate facilitation. Red Rough Arrows (⟂): Indicate inhibition. Green Arrows: Indicate a decrease

Solasonine (SS), a glycoalkaloid from Solanum nigrum L, demonstrates potential in cancer therapy, showing antitumor effects on lung cancer cells. Its action involves inducing ferroptosis, marked by increased levels of LPO, iron, and ROS. The effectiveness of SS is attributed to compromised antioxidant defenses and mitochondrial damage, crucial factors in the ferroptosis process it triggers [74]. Erianin, a phenolic natural product isolated from Dendrobium chrysotoxum Lindl, has been shown to inhibit the growth of H460 and H1299 cell lines through the induction of Ca2+/calmodulin (CaM)-dependent ferroptotic cell death. This process is accompanied by the formation of ROS, lipid peroxidation, and depletion of GSH [75]. Diplacone (DP), a flavonoid derivative, has been investigated for its capacity to augment mitochondrial calcium influx, ROS generation, the opening of the MPTP, and a reduction of MMP, which are characteristics of ferroptosis. Studies have established that the application of DP to A549 cells not only inhibits cell growth but also enhances lipid peroxidation, a critical step in ferroptosis, along with an increase in ATF3 expression. ATF3 has been identified as playing a role in ferroptosis by regulating the expression of genes involved in iron metabolism and lipid peroxidation. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that ferroptosis inhibitors, such as ferrostatin-1 and liproxstatin-1, can mitigate DP-mediated cell death in A549 cells. Overall, these findings support the hypothesis that DP can induce ferroptosis in the treatment of NSCLC [76]. The Qingrehuoxue Formula (QRHXF), a two-herb Chinese medicinal formula consisting of Radix Paeoniae Rubra and Scutellaria baicalensis, contains various active compounds including baicalin and paeoniflorin [77, 78]. QRHXF treatment significantly elevates ROS, Fe2+, H2O2, and MDA levels, while reducing GSH levels, indicating its potent effect on oxidative stress. It suppresses the expression of SLC7A11 and GPX4, key ferroptosis markers, and induces changes in the mitochondrial ultrastructure of tumor cells without causing toxicity in tumor-bearing mice. Furthermore, QRHXF upregulates p53 and phospho-glycogen synthase kinase-3 (p-GSK-3β) expressions while downregulating Nrf2 levels. Thus, QRHXF hinders NSCLC cell progression by promoting iron-induced apoptosis and ferroptosis through the p53 and GSK-3β/Nrf2 signaling pathways [78].

Bufotalin, a steroid compound extracted from Venenum Bufonis, has demonstrated significant anticancer properties [79]. Research shows that bufotalin triggers ferroptosis in NSCLC cells through enhanced lipid peroxidation, driven by GPX4 degradation and elevated intracellular Fe2+ levels [32]. Dihydroisotanshinone I (DT), a quinone derivative isolated from the dried roots of Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge, has shown inhibitory effects on the proliferation of A549, H460, and IMR-90 lung cancer cell lines. Mechanistically, DT inhibits the production of GPX4, thereby initiating ferroptosis via lipid peroxidation [80]. Sanguinarine (SAG), a benzophenanthridine alkaloid derived from the root of Sanguinaria canadensis Linn, exhibited significant inhibitory effects on the growth and metastasis of NSCLC in a xenograft model [81]. SAG destabilizes GPX4 through E3 ligase STUB1-mediated ubiquitination, leading to GPX4 degradation and subsequent ferroptosis [81]. Following this, Red Ginseng Polysaccharide (RGP), polysacchride, an active component of Panax ginseng C. A. Meyer (Araliaceae), has been shown to inhibit the proliferation of human A549 and MDA-MB-231 cells, induce lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release, promote ferroptosis, and suppress GPX4 expression [82]. Similarly, Timosaponin AIII (Tim-AIII), a steroidal saponin from Anemarrhena Asphodeloides Bunge, induces NSCLC cell death and G2/M arrest. It achieves this therapeutic effect by interacting with its target protein HSP90, facilitating the ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of GPX4, thereby inducing ferroptosis [83]. Zerumbone, a terpenoid compound, primarily extracted from Zingiber zerumbet Smith, acts as an anticancer agent by inhibiting tumor proliferation and promoting cell death [84, 85]. When combined with gefitinib, Zerumbone inhibits lung cancer cell proliferation through multiple mechanisms, including the activation of the AKT/STAT3/SLC7A11 axis, which decreases GPX4 activity and thereby induces ferroptosis [86]. Nrf2 plays a critical role in maintaining cellular redox balance by activating endogenous antioxidant response elements [87]. HO-1 is the primary protein targeted by Nrf2 in the context of oxidative stress. Recent studies have emphasized the importance of Nrf2 and HO-1 in the ferroptotic response. For instance, S-3'-hydroxy-7', 2', 4'-trimethoxyisoxane (ShtIX), a novel flavonoid compound, has been shown to initiate ferroptosis in NSCLC cells by inhibiting the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway [88]. Ginkgetin has been reported to induce ferroptosis in NSCLC by inactivating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway, thereby enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of cisplatin (DDP) [89]. Additionally, Sanguinarine amplifies MMP loss and DDP-induced apoptosis in NSCLC cells, supporting the potential for combining natural products with chemotherapeutic agents for tumor treatment [72]. Manoalide (MA), a marine terpenoid derived from sponges, has been observed to inhibit the proliferation of KRAS-mutated lung cancer cells and organoids. Notably, MA induces ferroptosis by inhibiting the Nrf2-SLC7A11 axis and ferritin heavy chain 1 (FTH1) pathways, which are activated by excess mitochondrial Ca2+. This enhances the susceptibility of osimertinib-resistant lung cancer cells to osimertinib [90].

In vitro studies have demonstrated that Hedyotis diffusa injection (HDI) can reduce the viability of lung adenocarcinoma cells and induce ferroptosis by modulating VDAC2/3 activity, which is achieved through the upregulation of pro-apoptotic protein Bax and the downregulation of anti-apoptotic protein Bcl2 [91]. Natural borneol (d-borneol), another terpenoid, is extracted from the fresh leaves and branches of Cinnamomum camphora (L.) J. Presl. When combined with cisplatin, d-borneol has been shown to reduce both the volume and weight of tumors, thereby exhibiting anticancer effects. Mechanistically, its role has been linked to ferroptosis, NCOA4-mediated ferritin autophagy, and the upregulation of prion protein (PRNP). Additionally, it leads to the downregulation of Poly(rC)-binding protein 2 (PCBP2), resulting in elevated intracellular iron ion levels [92].

The anti-cancer properties of artemisinin derivatives, such as artesunate (ART) and dihydroartemisinin (DHA), have gained considerable attention in the medical field for their efficacy against various cancers, including lung cancer, colon cancer, nasopharyngeal cancer, and glioma. Both ART and DHA are terpenoid derivatives of artemisinin and have been shown to downregulate the expression of the cystine/glutamate transporter, a critical inhibitor of ferroptosis in NSCLC cells. These compounds primarily induce ferroptosis by upregulating the expression of TFRC, a marker indicative of ferroptosis [93]. Non-coding RNAs, particularly long non-coding RNAs and microRNAs, are implicated in various biological processes, including apoptosis, autophagy, and tumor initiation [94]. FTH1 serves as a marker for ferroptosis. Curcumenol, a terpenoid compound found in Wenyujin, has demonstrated significant anti-cancer properties across various cancer types [95]. Studies have shown that curcumenol-induced ferroptosis is the primary mechanism of lung cancer cell death, both in vitro and in vivo. The lncRNA H19/miR-19b-3p/FTH1 axis plays a crucial role in this ferroptotic cell death induced by curcumenol [96]. Sulforaphane (SFN), a glycoside derived from cruciferous vegetables, has been shown to decrease the expression of SLC7A11, a key component of the system Xc−. This reduction suggests that the anti-tumor effects of SFN may be attributed to the induction of ferroptosis in SCLC cells, potentially due to the downregulation of SLC7A11 at both mRNA and protein levels [97].

Sinapine (SI) is an alkaloid extractable from various rapeseed and cruciferous plant species [98]. Numerous studies have attested to its antioxidant, neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, and anti-tumor properties [99, 100]. The p53 protein functions as a transcription factor that inhibits cell proliferation and viability, acting as a pivotal tumor suppressor and a ferroptosis regulator [73]. Researchers have confirmed that SI induces ferroptosis in NSCLC cells through a mechanism that involves p53-dependent downregulation of SLC7A11 and upregulation of TF and TFR, ultimately leading to iron accumulation and ferroptosis [101]. HO-3867, a synthetic analog of curcumin (CUR), exhibits potent antitumor activity against various cancer cell types. This compound induces ferroptosis via the activation of the p53-mediated signaling pathway, targeting DMT1 as its downstream effector and concurrently inhibiting the expression of GPX4 [102].

6-Gingerol, a naturally occurring phenol found in ginger, exhibits anti-tumor properties by targeting ubiquitin-specific protease 14 (USP14), a cysteine protease involved in deubiquitination that suppresses autophagy in various cancers. By downregulating USP14, 6-Gingerol enhances autophagosome formation, increases ROS and iron levels, thereby reducing survival, proliferation, and tumor size [103].

KRAS, a key lung tumor growth biomarker, presents a viable target for NSCLC therapies [104]. Activation of the Ras/Raf/ERK pathway is essential for cancer progression. In the caenorhabditis elegans model, realgar, a sulfide mineral from ores, downregulates Ras expression through the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway [105]. Further studies reveal Realgar's potential to inhibit KRAS-mutated lung cancer cell growth by inducing ferroptosis via the Raf-mediated Ras/MAPK pathway [106], positioning it as a promising anti-cancer agent, especially for Ras mutation-targeted ferroptosis.

Curcumin, a phenolic compound from turmeric, is recognized for promoting ferroptosis, particularly in NSCLC, by activating autophagy. This mechanism, linked to the maintenance of cellular iron homeostasis by ferritin [107], suggests that inducing ferroptosis through autophagy can improve NSCLC treatment outcomes [108]. The interplay between autophagy and ferroptosis highlights the potential of leveraging natural products for developing multi-pathway disease treatments.

Anti-cancer immune responses: in-depth exploration have led to the classification of NSCLC, specifically lung squamous carcinoma (LUSC), as an "immunotherapy-responsive disease" [109]. Mutations affecting cellular iron levels within tumor cells have the potential to trigger robust anti-tumor immune responses both in vivo and in vitro, thereby potentially enhancing the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors [110]. Resveratrol, a phenolic compound, concentrated in the peanuts, grapes, knotweed, mulberries, has been shown to induce higher levels of ferroptosis in H520 cells, improve the cytotoxic effects of CD8+ T cells within the tumor microenvironment by modulating the HMMR/ferroptosis axis in cases of LUSC [111]. However, in erastin-induced ferroptosis in BEAS-2B cells, resveratrol promotes GPX4 and GSH expression and protects BEAS-2B cells from ferroptosis via the Nrf2/Keap1 pathway [112].

To summarize, the reviewed studies demonstrate the efficacy of 8 natural products from herbs—flavonoids, phenols, alkaloids, terpenoids, steroids, quinones, polysaccharides, and glycosides—comprising 21 active ingredients. These compounds modulate ferroptosis, inhibit tumor growth, invasion, metastasis, and enhance cancer survival. They induce ferroptosis through mechanisms like increased GPX4 ubiquitination, GPX4 and GSH depletion, calcium channel activation leading to calcium overload, iron metabolism enhancement, ferritin autophagy initiation, Fenton reaction, mitochondrial membrane disruption, ROS release, and lipid peroxidation. Key pathways include GPX4-related, SLC7A11-related, VDAC-mediated, p53-mediated, Nrf2-mediated, and NCOA4-mediated mechanisms. But it should be noted that balancing the effects of ferroptosis-modulating drugs on cancerous versus healthy tissues remains a significant challenge.

Acute lung injury

ALI is a critical condition that may manifest as a severe form of ARDS or part of Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome (MODS). It’s typically marked by uncontrolled oxidative stress, pulmonary inflammation, damage to the alveolar and microvascular endothelia, and pulmonary edema [113], with the potential to evolve into ARDS and MODS. Current treatment modalities for ALI primarily include nutritional support, mechanical ventilation, etiological treatment, symptomatic relief, and maintenance of internal homeostasis, supplemented with glucocorticoid hormone, inhaled pulmonary vasodilator, nerve muscle blocker [114, 115]. Given the high morbidity and mortality associated with ALI, there's a pressing need for new therapeutic approaches. Recent research highlights that bioactive compounds from Chinese herbs and their extracts could offer new pathways to mitigate ALI/ARDS. Notably, increased iron accumulation has been observed in the lungs of mice suffering from ALI. Excessive iron promotes the generation of superoxide and induces lipid peroxidation through the Fenton reaction, ultimately triggering ferroptosis [66]. Ferroptosis has been implicated in several models of ALI, including those induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS), intestinal ischemia/reperfusion (I/R), seawater drowning, fine particulate matter (PM2.5), oleic acid, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) [13]. We collected relevant lung injury studies and found that inhibition of ferroptosis has a significant effect on the treatment of ALI.

Nrf2, a key transcription factor, is essential in regulating cellular antioxidant defenses and plays a vital role in mitigating ALI by preventing ferroptosis. Its activation leads to a decrease in GSH depletion and an increase in the expression of oxidative stress-related factors, including hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) and HO-1. This activation subsequently inhibits the accumulation of MDA, ROS, and lipid ROS, enhances mitochondrial structure and function, reduces ferroptosis, and alleviates ALI [89, 116]. HIF-1α plays a crucial role in bolstering anti-ferroptotic defenses, reducing iron accumulation, and boosting GPX4 expression [117]. The Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway is pivotal in controlling cellular damage caused by various factors, with its activation offering protection against tissue and cellular damage through diverse mechanisms [118]. SLC7A11, also known as xCT, alleviates oxidative stress in epithelial cells by enhancing intracellular cystine levels, acting as a negative feedback loop to restrain the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, thus preserving cellular antioxidant balance [119]. Collectively, these studies unequivocally establish that Nrf2 serves as a major negative regulator of ferroptosis in ALI, and that ferroptosis itself contributes to the progression of ALI. In this review, we summarize the mechanisms by which natural products treat ALI through the regulation of ferroptosis, as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Natural products targeting ferroptosis in ALI

| Component | Classification | Main roots | Test models | Dose | Mechanisms | Specific effects | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Astaxanthin | Terpenoids | Various microorganisms, phytoplankton, marine animals, and seafood |

In vitro: LPS induced RAW264.7 cells; In vivo: LPS induced female Balb/c mice |

In vitro: 5, 10, 20 μM; In vivo: 20 mg/kg |

Activating the Keap1-Nrf2/HO-1 pathway | Decreasing inflammatory relative: COX2, iNOS, NO↓; NF-KB, P-P65↓; decreasing lipid metabolism relative: lipid ROS↓; inhibiting ferroptosis relative: 4-HNE, PTGS2, ACSL4 and CD68↓; SLC7A11, GPX4 and FTH1↑ | [121] |

| Panaxydol | Polyacetylenes | Panax ginseng |

In vitro: LPS induced BEAS-2B cells; In vivo: LPS induced male C57BL/6 mice |

In vitro: 40 μg/ml; In vivo: 20 mg/kg |

Activating the Keap1-Nrf2/HO-1 pathway | Decreasing inflammatory relative: TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6↓; MPO activity, neutrophil percentage (%) ↓; reducing pulmonary edema: Lung W/D ratio, total protein↓; inhibiting ferroptosis relative: Fe2 + , MDA ↓; GSH and GPX4 ↑ | [30] |

| Urolithin A | Phenols | A secondary metabolite of ellagitannins and ellagic acid |

In vitro: LPS induced BEAS-2B cells; In vivo: LPS induced male C57BL/6 mice |

In vitro: 10 μM; In vivo: 50 mg/kg |

Activating the Keap1-Nrf2/HO-1 pathway | Decreasing inflammatory relative: TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6↓; neutrophil percentage (%) ↓; reducing pulmonary edema; Lung W/D ratio, total protein↓; reducing oxidative stress: Intracellular ROS and mitochondrial ROS, MDA↓; GSH, CAT, SOD↑; inhibiting ferroptosis relative: GPX4, SLC7A11↑; Fe2 + , 4-HNE↓; the number of mitochondria↑, mitochondria structural damage↓ | [128] |

| Obacunone | Flavonoids | Citrus and rutaceae species |

In vitro: LPS induced BEAS-2B cells; In vivo: LPS induced male C57BL/6 mice |

In vitro: 20 μM; In vivo: 2.5, 5, 10 mg/kg |

Activating the Nrf2/SLC7A11/GPX4 axis | Decreasing inflammatory relative: IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α↓; KL-6, CRP and neutrophils (%) ↓; lymphocytes (%) ↑; reduced the LPS-induced loss of ALI lung tissue structure loss, apoptosis injury, and edema; reducing oxidative stress: CAT, GSH, SOD↑; MDA↓; inhibiting ferroptosis relative: Fe 2 + , 4-HNE↓; GPX4, SLC7A11↑; TEM: mitochondrial structural damage | [131] |

| Wedelolactone | Lactones | Eclipta prostrata |

In vitro: LPS induced AR42J cells; In vivo: sodium taurocholate or caerulein induced male Sprague–Dawley rats |

In vitro: 20 μM; In vivo: 20, 50 mg/kg (taurocholate-induced), 50, 100 mg/kg (caerulein-induced) |

Activating GPX4 level | Decreasing proinflammatory cytokines: TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-18, NLRP3↓; reducing oxidative stress: ROS, MDA↓; inhibiting lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis: GSH, GSH-Px, GPX4, GSDMD, DGSDMD-N↑, 4-HNE↓; decreasing serum pancreatic digestive enzymes: LDH, amylase, lipase↓; inhibiting pyroptosis: caspase1, caspase11↓ | [133] |

| Qingyi Decoction | Formulas | Chinese herbal medicine | In vivo: Sodium taurocholate induced Aprague-Dawley male rats | In vivo: 10 g/kg | Activating ALDH2/ANXA1; downregulating ICAM-1 | Decreasing inflammatory relative: TNF-α and IL-6↓; inhibiting the increase of serum amylase and Lung W/D ratio; reducing neutrophil infiltration: ANXA1↑, ICAM-1, P-P65/P65↓; inhibiting ferroptosis relative: Fe2 + , MDA, MPO↓; ALDH2, GSH, SLC7A11, FTH1 and GPX4↑ | [134] |

| Matrine | Alkaloids | Sophora flavescens |

In vitro: LPS-induced BEAS-2B cells and MLE-12 cells; In vivo: cerulein and LPS induced UCP2 -/- mice |

In vitro: -; In vivo: 200 mg/kg |

Activating the UCP2/SIRT3/PGC1αpathway | Decreasing inflammatory cytokines: IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α, total BALF protein↓; reducing lipid peroxidation: intracellular ROS, MPO↓; inhibiting ferroptosis: Fe2 + , MDA, ACSL4↓; GSH, GPX4, NRF1, mtTFA, HO-1 and NQO1↑ | [136] |

| Sipeimine | Alkaloids | Fritillaria roylei | In vivo: PM2.5 dust suspension induced male Sprague–Dawley rats | In vivo: 15 mg/kg (low-dose), 30 mg/kg (high-dose) | Activating the PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 pathway | Decreasing inflammatory cytokines: TNF-α and IL-1β↓; inhibiting ferroptosis relative: MDA, 4-HNE, iron↓; Nrf2, GSH, GPX4, HO-1, SLC7A11 and FTH1↑; the mitochondria ultrastructure was significantly improved | [140] |

| Tectoridin | Flavonoids | The rhizome of Belamcanda chinensis |

In vitro: PM2.5-induced BEAS-2B cell; In vivo: PM2.5-induced Nrf2-knockout mice |

In vitro: 100 μM; In vivo: 50 mg/kg (low-dose), 100 mg/kg (high-dose) |

Activating the Nrf2/SLC7A11/GPX4 axis | Decreasing inflammatory factors, lipid peroxidation, iron accumulation and ferroptosis: MDA↓, GSH, GPX4, xCT, FTH1/FTL, TFR↑ | [141] |

| Rosavin | Glycosides | Rhodiola plants | In vivo: PM2.5 dust suspension induced male Sprague–Dawley rats | In vivo: 50 mg/kg (low-dose), 100 mg/kg (high-dose) | Activating the PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 pathway | inhibiting ferroptosis relative: MDA, 4-HNE, iron↓; Nrf2, GSH, GPX4↑ | [142] |

| Astragaloside IV | Glycosides | Astragalus | In vivo: PM2.5 dust suspension induced C57BL/6 J male mice | In vivo: 50 mg/kg (low-dose), 100 mg/kg (high-dose) | Activating the Nrf2/SLC7A11/GPX4 axis | Reducing pulmonary edema; reducing oxidative stress: MDA and MPO↓; SOD↑; decreasing inflammatory cytokines: IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β and COX2↓; inhibiting ferroptosis relative: Nrf2, HO-1, SLC7A11, GPX4, FLC, FTH1↑; TFRC↓; the mitochondria ultrastructure was significantly improved | [143] |

| Isoliquiritin apioside | Flavonoids | Glycyrrhizae radix et rhizoma |

In vitro: Hypoxia and reoxygenation induced MLE-2 cells; In vivo: I/R induced male C57BL/6 mice |

In vitro: 25, 50, 100 μM; In vivo: 50 mg/kg (low-dose), 100 mg/kg (high-dose) |

Inhibiting Hif-1α/HO-1 pathway | Decreasing proinflammatory cytokines: TNF-α, IL-6, Hmgb1↓; inhibiting ferroptosis: MDA, Fe2 + , Ptgs2, ACSL4↓; GSH, GPX4↑ | [148] |

| Salidroside | Glycosides | Rhodiola rosea | In vivo: Hyperoxia-induced KM mice | In vivo: 100 mg/kg | Inhibiting the Act1/TRAF6/p38 MAPK pathway | Decreasing inflammatory and immunity relative: IL-6, TGF-β, IL-17A, IL-17RA↓; inhibiting ferroptosis relative: Fe 2 + , MDA↓; GPX4↑; reducing pulmonary edema, atelectasis, necrosis, alveolar and interstitial inflammation, and collagen deposits | [151] |

| Ferulic acid | Phenols | In various kinds of plants and vegetables such as tomatoes, sweet corn and rice bran |

In vitro: LPS induced MLE-12 cells; In vivo: female Balb/c mice were induced by the CLP |

In vitro: 0.1 μM; In vivo: 100 mg/kg |

Activating the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway | Ameliorating barrier dysfunction and pulmonary edema: Lung W/D ratio, total protein↓; ZO-1, occludin, and claudin-1, TEER↑; FITC-dextran flux↓; inhibiting ferroptosis relative: ROS, MPO, Fe2 + , MDA↓; GSH, GPX4↑ | [156] |

| Puerarin | Flavonoids | Gegen | In vitro: LPS induced A549 cells | In vitro: 80 μM | Activating SLC7A11/ GPX4 axis and FTH1 | Decreasing inflammatory relative: TNF-α, IL-8, and IL-1β↓; decreasing lipid peroxidation: MDA, ROS↓; inhibiting ferroptosis relative: total iron levels and ferrous iron, NOX1↓; SLC7A11, GPX4, GSH, FTH1↑ | [157] |

| Tripterygium wilfordii Hook.f | Terpenoids | Celastraceae plants | In vivo: Male Balb/c mice were induced by PQ | In vivo: 10 g/kg | Modulating the Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway |

Reducing the levels of proinflammatory cytokines: IL-6 and TNF-α; alleviating oxidative stress: MDA↓; GSH, SOD↑ |

[161] |

| Proanthocyanidins | Flavonoids | Carthamus tinctorius L | In vivo: Mice were infected by IAV and HINI | In vivo: 20 mg/kg | Inhibiting the TGF-β1/Smad signaling pathway and IFN-γ expression | Decreasing the levels of MDA and ACSL4; upregulating the expression of GSH, GPX4, and SLC7A11; | [162] |

| Naringenin | Flavonoids | Citrus fruits |

In vitro: AgNPs induced BEAS-2B cells; In vivo: AgNPs suspension induced male ICR mice |

In vitro: 25, 50, 100 μM; In vivo: 25, 50, 100 mg/kg |

Activating the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway | anti-inflammation, anti-oxidative stress, anti-apoptosis: BAX, CytC, Caspase9, Caspase3↓; Bcl2↑; anti-ferroptosis; decreasing the levels of white blood cells, neutrophils, and lymphocytes in the blood, ameliorating lung injury, suppressing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines; | [164] |

↑: up-regulation, increase or activation; ↓: down-regulation, decrease or inhibition

Astaxanthin (AST) is a xanthophyll carotenoid belonging to the terpenoids class, found in various microorganisms, phytoplankton, marine animals, and seafood [120]. Luo et al. investigated LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells and mice with ALI and discovered that Astaxanthin mitigated inflammatory responses, inhibited ferroptosis, and ameliorated lung damage through the activation of the Keap1-Nrf2/HO-1 pathway [121]. Panax ginseng is a well-known botanical species utilized in traditional medicine for its detoxifying properties, blood glucose regulation, prevention of arteriosclerosis, and potential anti-aging effects [119, 122]. The pharmacological efficacy of ginseng is primarily attributed to its polyacetylene compounds. Panaxydol (PX) is a polyacetylene molecule that has been extensively studied for its diverse biological properties, including anti-fatigue, anti-tumor, and neuroprotective effects [123–125]. In the LPS-induced mouse lung injury model, endotoxin infection increases alveolar capillary permeability, leading to fluid and protein leakage into the alveoli, which causes pulmonary edema and lung tissue damage. These conditions show improvement following PX intervention. Further, PX effectively mitigates LPS-induced ferroptosis in ALI through the Keap1-Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, suggesting its potential as a novel therapeutic option for ALI treatment [30]. Urolithin A (UA) is a secondary metabolite derived from the gut microbiome metabolism of ellagitannins and ellagic acid, which are abundant in pomegranates, strawberries, and various nuts [126, 127]. UA, a phenolic compound, significantly reduced histological alterations, the wet-to-dry lung weight ratio, and the invasion of inflammatory cells, thereby offering protection against LPS-induced ALI in mice. The underlying mechanism involves the activation of the Keap1-Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, which subsequently elevates antioxidant levels in lung tissue and reduces ferroptosis [128]. Obacunone (OB) is a naturally occurring flavonoid commonly found in citrus fruits and is known for its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties [129, 130]. Research demonstrated that OB significantly mitigated lung histopathological injury, reduced the release of inflammatory cytokines, and decreased levels of Fe2+ and 4-HNE, by inhibiting Nrf2 ubiquitination and upregulating the Nrf2/SLC7A11/GPX4 signaling pathway, ultimately inhibiting iron-dependent ferroptosis and alleviating LPS-induced ALI [131].

Wedelolactone (Wed) is the principal active component of Eclipta prostrata and is categorized as a lactone [132]. Research findings indicate that Wed mitigates pancreatitis and associated lung damage in mouse models induced by taurine cholate or small proteins. Specifically, Wed inhibits cell death and ferroptosis in pancreatic and pancreatic acinar cells by upregulating GPX4 [133]. Qingyi decoction (QYD) is a robust anti-inflammatory agent that can improve the intestinal barrier damage caused by SAP, microcirculatory disorders, and pulmonary inflammatory response and has been shown to inhibit both ferroptosis and apoptosis by enhancing the activity of Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2). This suggests that QYD has potential therapeutic efficacy in treating lung injury related to severe acute pancreatitis (SAP). Originating from the formula in "Shanghan Lun," as a decoction made from Chinese herbal medicine, QYD is employed in the treatment of acute pancreatitis (AP) patients due to its laxative, heat-clearing, and detoxifying properties [134, 135]. Uncoupling Protein-2 (UCP2) is crucial for managing ROS, maintaining redox balance, and modulating immune responses. Research shows that matrine, an alkaloid from Sophora flavescens, reduces inflammation, oxidative stress, and iron buildup in lung tissue during severe acute pancreatitis-induced acute lung injury (SAP-ALI) by activating the UCP2/SIRT3/PGC1α pathway, highlighting matrine's therapeutic potential for SAP-ALI management [136].

Exposure to PM2.5 has been linked to a multitude of respiratory diseases and was responsible for over 4.2 million deaths in 2015 [137]. Various studies have indicated that PM2.5-induced lung damage is associated with ferroptosis through multiple signaling pathways. One such pathway, the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/Akt), is instrumental in regulating the activation of Nrf2, which in turn mitigates lung injury. Sipeimine, a steroidal alkaloid extracted from Fritillaria roylei, possesses significant pharmacological attributes, including anti-inflammatory, antitussive, and anti-asthmatic effects [138, 139]. The primary mechanism by which sipeimine ameliorates PM2.5-induced ALI is predominantly through the PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 pathway. This leads to the attenuation of ferroptosis and the restoration of downregulated proteins involved in ferroptosis, such as GPX4, HO-1, and SLC7A11 [140]. Tectoridin, a flavonoid from the rhizome of Belamcanda chinensis, activates the Nrf2 signaling pathway to prevent ferroptosis in lung damage [141]. Similarly, rosavin, a key glycoside from Rhodiola plants, protects against PM2.5-induced lung injury by activating the PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 pathway to inhibit ferroptosis [142]. Astragaloside IV (Ast-IV), a principal glycosidic molecule found in astragalus, effectively modulates ferroptosis and curbs iron-dependent ROS buildup in ALI triggered by PM2.5. It accomplishes this by specifically targeting the Nrf2/SLC7A11/GPX4 axis, showcasing a strategic approach to mitigating the impact of ALI through ferroptosis regulation [143].

ALI resulting from lung or intestinal I/R injury has garnered increasing scholarly attention. This condition is primarily linked to oxidative stress, inflammatory responses, and various modes of cell death, including the recently identified ferroptosis [144]. Ferroptosis, as a novel cell death mode, has been found to be involved in the development of ALI caused by intestinal I/R [145]. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) is a dimeric protein complex, with HIF-1α serving as its main active component. HIF-1α targets HO-1, thereby increasing heme metabolism and subsequently elevating free iron levels, which in turn triggers ferroptosis [146, 147]. Recent research has demonstrated that isoliquiritin apioside (IA), a natural flavonoid derived from Glycyrrhizae radix et rhizoma, exerts a protective effect against ALI induced by intestinal I/R. This protective effect is mediated through a HIF-1α dependent mechanism that inhibits ferroptosis in lung epithelial cells [148]. In a study conducted by Zhou et al., IA was found to inhibit the overexpression of HIF-1α and HO-1 proteins, both in vivo and in vitro. Furthermore, when IA was administered to hypoxia/regeneration (H/R)-induced MLE-2 cells, activation of HIF-1α led to increased levels of Ptgs2 and ACSL4, while suppressing GPX4, which are pivotal in initiating ferroptosis [148].

Hyperoxia-induced acute lung injury (HALI) is a life-threatening condition characterized by extensive immune cell infiltration and subsequent apoptosis of type II alveolar epithelial cells (AECII). Salidroside, a bioactive glycoside derived from Rhodiola rosea, has been studied for its potential therapeutic effects on HALI. Interleukin (IL)-17A, a critical pro-inflammatory cytokine primarily produced by Th17 cells, is implicated in various diseases, including autoimmune disorders [149] and ALI [150]. Recent research has indicated that salidroside mitigates HALI through IL-17A-mediated ferroptosis. In salidroside-treated HALI models, levels of pro-inflammatory factors such as IL-6, TGF-β, IL-17A, and IL-17RA were found to be reduced. Additionally, the concentration of the ferroptosis biomarker, ferrous ion, was decreased, while the expression of GPX4, a key enzyme in preventing ferroptosis, was elevated [151]. P38 MAPK is a key signaling molecule implicated in both inflammation and ferroptosis [152, 153]. Act1/TRAF6 is a conventional signaling pathway responsible for IL-17A activation and also serves as an upstream signal for p38 MAPK [154]. Further validation in a hyperoxia-induced KM mouse model revealed that salidroside alleviates HALI-associated inflammation and ferroptosis by inhibiting the Act1/TRAF6/p38 MAPK pathway [151].

According to existing data, the incidence of ALI in patients with sepsis is estimated to be over 40%, and a significant percentage of these cases may progress to ARDS [3, 155]. Ferulic acid (FA), a phenolic compound naturally found in various plants and vegetables, has been shown to have therapeutic potential in this context. Studies indicate that ferulic acid can reduce the lung injury score by 48%, inhibit alveolar epithelial cell ferroptosis, and enhance alveolar epithelial barrier function through the activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway in sepsis-induced ALI [156]. Puerarin, a flavonoid monomer, has also been investigated for its protective effects against pulmonary damage in sepsis. Specifically, puerarin was found to suppress both ferroptosis and the inflammatory burst in lung damage induced by sepsis. This was achieved in LPS-induced A549 cells by activating the SLC7A11/GPX4 axis and upregulating FTH1 expression [157]. Paraquat (PQ) poisoning is known to induce ALI and PF, both of which are associated with high mortality rates and limited therapeutic options [158]. Research indicates that the progressive inflammatory responses and lung fibrosis resulting from PQ poisoning are linked to excessive production of ROS through redox cycling [159]. Tripterygium wilfordii Hook.f. (TwHF), a member of the celastraceae family commonly known as lei gong teng in China, primarily contains terpenoids as its active substances [160]. Studies have demonstrated the potential efficacy of TwHF in treating PQ-induced lung fibrosis. Further investigations revealed that ferroptosis plays a role in the pathogenesis of PQ poisoning, and TwHF treatment was shown to inhibit the progression of pulmonary ferroptosis via modulation of the Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway [161]. Proanthocyanidins (PAs), a class of bioactive flavonoids derived from Carthamus tinctorius L, have been shown to protect against ALI induced by Influenza A virus (IAV) and H1N1 through the inhibition of the TGF-β1/Smad signaling pathway. Moreover, PAs were found to suppress IFN-γ-induced ferroptosis, leading to the amelioration of ALI. This was evidenced by a reduction in MDA and ACSL4 levels, along with an upregulation of GSH, GPX4, and SLC7A11 expression [162]. Naringenin, a flavonoid primarily found in fruits like grapefruit and oranges, as well as in vegetables, possesses a range of bioactive properties, including anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-proliferative, anti-atherosclerotic, and anti-ferroptotic effects [163]. Extensive research has shown that naringenin protects against silver nanoparticles (AgNPs)-induced pulmonary damage by upregulating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway [164].

To summarize, these studies collectively demonstrate that 7 natural products extracted from herbs, including flavonoids, phenols, alkaloids, terpenoids, polyacetylenes, glycosides, and lactones, with their 17 active ingredients, inhibit ALI caused by a variety of factors, including LPS, IAV, AgNPs, PQ, hyperoxia, intestinal I/R, SAP, and PM2.5. These natural products predominantly modulate the alveolar capillary permeability within the lung tissue, mitigate damage to alveolar epithelial and pulmonary capillary endothelial cells, alleviate pulmonary edema, and attenuate inflammatory responses and oxidative stress. Furthermore, they inhibit lipid peroxidation, curtail iron accumulation, and suppress the induction of ferroptosis, contributing to an enhanced pulmonary function and structural integrity. They primarily regulate the Nrf2/HO-1 and SLC7A11/GPX4 signaling pathways. Additionally, they also affect related signaling pathways, including PI3K/AKT, UCP2/SIRT3/PGC1α, Act/TRAF6/P38MAPK, and TGF-β/Smad. These pathways additionally regulate crucial targets of ferroptosis, including GPX4, ACSL4, SLC7A11, FTH1, FTL, and TER, which ultimately inhibit ferroptosis and ameliorate ALI.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

COPD, featured with chronic airway inflammation and airflow limitation often linked to smoke, dust, and toxic fumes [165], ranks as the fourth leading cause of death worldwide, yet current treatments are not fully effective [166]. Research indicates that cigarette smoke (CS) exacerbates COPD progression by promoting excessive cellular iron accumulation, facilitating ferroptosis [167]. The use of ferroptosis inhibitors, such as deferoxamine and ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1), shows promise in countering CS-induced ferroptosis in bronchial epithelial cells [168], highlighting an area needing further exploration. Among natural products, curcumin (CUR), a polyphenolic compound from turmeric, has been shown to alleviate ferroptosis by upregulating of the SLC7A11/GPX4 axis and FTH1, downregulating TFR expression, thereby ameliorating lung epithelial cell injury and inflammation induced by CS [165]. Dihydroquercetin (DHQ), a flavonoid, has shown potential in mitigating ferroptosis in COPD by modulating iron transport and activating Nrf2-dependent pathways [17]. Wang et al. reported that the combination of Tongxinluo (TXL) and atorvastatin elevated the levels of GPX4 and ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1), while reducing the levels of ACSL4. This led to a decrease in LPO and other key ferroptotic processes by modulating unsaturated fatty acid metabolism, thereby offering a therapeutic approach for COPD complicated with atherosclerosis [31]. Scutellarein is a flavonoid compound derived from plants such as Scutellaria altissima L, S.baicalensis Georgi, S. Barbara D. Don. Liu et al. found that scutellarin prevented RSL3-induced ferroptosis and mitochondrial damage in BEAS-2B cells and alleviated LPS/CS-induced COPD in mice. Mechanistically, scutellarein directly chelates Fe2+ and interacts with ALOX15 to reduce lipid peroxidation, reverse GPX4 downregulation, and block Nrf2/HO-1 and JNK/p38 pathway overactivation [169]. According to existing research, the main effect of this intervention is the suppression of ferroptosis, leading to enhanced mitigation of chronic inflammation and airway constriction in individuals with COPD. This is realized through the up-regulation of the SLC7A11/GPX4 axis and FTH1, coupled with the down-regulation of TFR1, and the attenuation of the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, as delineated in Table 3. The exploration of natural products with ferroptosis-inhibitory properties presents a novel avenue for the development of new therapeutics for COPD.

Table 3.

Natural products targeting ferroptosis in other pulmonary disease

| Disease | Component | Classification | Main roots | Test models | Dose | Mechanisms | Specific effects | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COPD | Curcumin | Phenols | Turmeric | BEAS-2B cells; Sprague–Dawley male rats |

In vitro: 5, 10, 20 μM; In vivo: 100 mg/kg |

Up-regulating SLC7A11/GPX4 axis and FTH1; down-regulating TFR1 | Up-regulating the protein levels of SLC7A11, GPX4, and FTH1; down-regulating the protein levels of TFR1; decreasing lipid peroxidation, GSH depletion, and iron overload; anti-oxidative stress: decreasing the contents of MDA and ROS | [165] |

| COPD | Dihydroquercetin | Flavonoids | Onion, French maritime pine bark, milk thistle, and Douglas fir bark | HBE cells; |

In vitro: 40, 80 μM; In vivo: 50 mg/kg (low-dose), 100 mg/kg (high-dose) |

Activating Nrf2-mediated pathway | Decreasing production of MDA and ROS, increasing SOD activity; up-regulating the protein levels of SLC7A11 and GPX4; decreasing lipid peroxidation; attenuating mitochondria damage | [17] |

| COPD | Tongxinluo | Formulas | Chinese herbal medicine | HPMECs; male C57BL/6 and ApoE-/- mice |

In vitro: 200, 400, 800 μg/ml; In vivo: 0.75 g/kg |

Up-regulating the protein expression of GPX4 and FSP1 | Increasing protein levels of GPX4, FSP1; decreasing protein levels of ACSL4; ameliorating pathological lung injury and pulmonary function: FRC, RI, Cdyn, MV; ameliorating dyslipidaemia and atherosclerotic lesions; protecting pulmonary microvascular endothelial barrier; enhancing the antioxidant capacity: GSH, SOD, MDA, NO; increasing HPMECs viability | [31] |

| COPD | Scutellarein | Flavonoids | Scutellaria altissima L; S.baicalensis Georgi; S Barbara D. Don | BEAS-2B cells; C57BL/6 mice |

In vitro: 5 μM; In vivo: 5, 10, 20 mg/kg |

Chelating Fe2 + and interacting with ALOX15 | Chelates Fe2 + and interacts with ALOX15 to reduce lipid peroxidation, reverse GPX4 downregulation, and block Nrf2/HO-1 and JNK/p38 pathway overactivation | [169] |

| Asthma | FAGS and CK | Other | Ginseng sprouts and its ginsenoside | Female C57BL/6 mice | In vivo: 300 mg/kg (FAGS: low-dose), 600 mg/kg (FAGS: high-dose); 50 μM (CK); | Up-regulating SLC7A11/GPX4 axis | Inducing airway hyperresponsiveness and IgE production; decreasing airway Inflammation: declining contents of inflammatory cells and Th2 cytokines; attenuating oxidative stress: decreasing contents of ROS and MDA; increasing the SLC7A11 and GPX4 expression levels, decreasing the 4-HNE expression level and iron accumulation | [173] |

| Asthma | Quercetin | Flavonoids | Variety of plants | RAW 264.7 cells; male C57BL/6 mice |

In vitro: 10 μM; In vivo: 25 mg/kg |

Inhibiting M1 macrophage polarization | Up-regulating expression of SLC7A11 and GPX4; decreasing total levels of inflammatory cytokines: TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-17A; alleviating lipid peroxidation: MDA, 4-HNE; decreasing the mRNA levels of M1'makers: CD86, iNOS, MF1 | [174] |

| PF | Dihydroquercetin | Flavonoids | Yew, larch and cedrus brevifolia bark | HBE cells, MRC-5 cells; C57BL/6 mice |

In vitro: 40 μM; In vivo: 10 mg/kg (low-dose), 50 mg/kg (high-dose) |

Inhibiting ferritinophagy |

Reducing the levels of profibrotic markers: α-SMA, collagen1 and fibronectin; decreasing the levels of ferropotosis relative factors: Fe2 + , ROS, MDA, 4-HNE content, lipid peroxidation; increasing levels of GPX4, GSH; up-regulating the ferritinophagy markers FTH1 and NCOA4, down-regulating autophagy makers LC3 |

[177] |

| PF | Tuberostemonine | Alkaloids | Stemona | HLF cells; C57BL/6 mice |

In vitro: 350, 550, 750 μM; In vivo: 50 mg/kg (low-dose), 100 mg/kg (high-dose) |

Up-regulating SLC7A11/GPX4 axis |

Reducing inflammation and collagen deposition; up-regulating SLC7A11, GPX4 and GSH; down-regulating the accumulation of iron and ROS |

[178] |

| LIRI | Tanshinone IIA | Quinones | Salvia miltiorrhiza | C57BL/6 mice | In vivo: 30 μg/kg | Activating the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway | Decreasing lung injury score, W/D ratio, MPO and MDA contents; inhibiting inflammatory response: decreasing the expression of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-a, increasing the expression of IL-10; inhibiting ferroptosis: increasing levels of GPX4, SLC7A11 and GSH, and decreasing levels of Ptgs2 and MDA; decreasing apoptosis: increasing in the Bcl-2, and decreasing in the Bax, Bim, Bad and caspase3 | [187] |

| LIRI | Salidroside | Glycosides | Rhodiola rosea | MLE-12 cells and RAW 264.7 cells; Male C57BL/6 and Nrf2 − / − mice |

In vitro: 40 µM; In vivo: 50 mg/kg |

Activating the Nrf2/SLC7A11 signaling axis |

Reducing lipid peroxides and iron overload, up-regulating the expression of ferroptosis tightly related proteins Nrf2, SLC7A11, and GPX4 |

[188] |

Asthma

Asthma is a chronic respiratory disease characterized by persistent inflammation in the airways, leading to symptoms such as wheezing, coughing, chest tightness, and shortness of breath [170]. It is estimated that approximately 300 million people worldwide suffer from asthma, with projections suggesting an additional 100 million will be affected by 2025 [171]. At present, asthma treatment mainly uses bronchodilators, hormones, and theophylline. During the acute attack period, hormone drugs such as albuterol bronchodilator, aminophylline, and prednisone can be used to relieve airway spasm. During the remission period, guidelines recommend that LABA or SABA combined with ICS can be used to improve symptoms and reduce the number of attacks [172]. Ryu et al. demonstrated that fermented and aged ginseng sprouts (FAGS) and compound K (CK) ameliorated various asthmatic markers, including Th2 cytokine production, IgE synthesis, mast cell activation, goblet cell hyperplasia, airway hyperresponsiveness, and inflammation, in a mouse model of allergic asthma. These effects were attributed to the inhibition of inflammatory responses and ferroptosis [173]. Quercetin (QCT), a widely occurring natural flavonoid, has been shown to possess anti-inflammatory and ferroptosis-inhibitory properties across various pathological conditions. In vitro studies have revealed that QCT mitigates LPS-induced ferroptosis by enhancing cell viability and upregulating the expression of antioxidant proteins involved in ferroptosis, specifically SLC7A11 and GPX4. Moreover, in the context of neutrophilic asthma-associated airway inflammation, ferroptosis was observed in conjunction with an elevated M1 phenotype. QCT was found to suppress ferroptosis in both cellular and animal models by inhibiting the pro-inflammatory M1 profile [174]. In conclusion, the current approach to mitigating ferroptosis in asthma mostly involves the inhibition of M1 polarization and inflammation. The key targets for regulating ferroptosis are SLC7A11 and GPX4 (see Table 3).

Pulmonary fibrosis

PF is a chronic progressive interstitial lung disease characterized by myofibroblast proliferation [175]. The pathogenesis of PF involves both adaptive and innate immune responses, inflammation, injury to epithelial and endothelial cells, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and apoptosis [73]. Currently, the clinical treatment of pulmonary fibrosis primarily involves the use of glucocorticoids, immunosuppressants, anti-fibrotic drugs, lung transplantation, and palliative care [176]. However, these treatments do not stop the progression of the disease and do not offer a cure, highlighting the need for the development of new drugs that are safer and more effective. Recent studies have indicated that ferroptosis in lung tissue contributes to the development of PF. Notably, several natural products have demonstrated protective effects against PF. Dihydroquercetin (DHQ), a flavonoid compound, has been shown to inhibit ferroptosis and ameliorate inflammation and silica-induced PF in mice. Further in vitro studies corroborate the protective effect of DHQ, indicating its role in attenuating silica-induced PF by impeding ferritinophagy-induced ferroptosis in human bronchial epithelial cells (HBECs). This effect is characterized by the activation of NCOA4, downregulation of microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3), and upregulation of FTH1 [177]. Tuberostemonine, an alkaloid derived from Stemona, exhibits inhibitory effects on ferroptosis in a model of bleomycin-induced PF in mice. This inhibition is associated with the upregulation of SLC7A11, GPX4, and GSH and the reduction of iron accumulation and ROS [178]. From the outlined studies, it is evident that natural products mitigate ferroptosis predominantly by modulating ferritin autophagy and the SLC7A11/GPX4 axis, contributing to the amelioration of PF (see Table 3). To elucidate the therapeutic potential of natural products in treating PF, further investigations, encompassing both clinical evaluations and foundational research, are essential, with a particular emphasis on elucidating the role of ferroptosis in this context.

Lung ischemia–reperfusion injury

Lung ischemia–reperfusion injury (LIRI) is a pathological condition that occurs when the lungs experience a period of insufficient oxygen supply followed by reperfusion [179]. This condition, which can develop after lung transplantation or ischemia in distant organs [180]. LIRI typically manifests in various clinical scenarios, such as cardiac arrest, shock, trauma, pulmonary thrombosis, lung transplantation, and extracorporeal circulation surgery [181]. During LIRI, a surge in reactive oxygen species and pro-inflammatory cytokines can occur, damaging alveolar epithelial cells and the endothelial barrier, leading to pulmonary edema and impaired alveolar gas exchange [182, 183]. New evidence suggests that tissue/cell damage caused by ischemia–reperfusion involves oxidative stress [184] and ferroptosis [185]. Given the high mortality rate associated with LIRI and the lack of effective treatment strategies, there is an urgent need to develop new drugs that can mitigate the pathological features of LIRI [186]. Tanshinone IIA (Tan IIA), an active compound in Salvia miltiorrhiza and a type of quinone [186], has been studied recently. Rui Zhang's research demonstrated that Tan IIA significantly inhibited the decrease in GPX4, SLC7A11, and GSH levels and the increase in Ptgs2 and MDA expression induced by I/R in mice, suggesting that Tan IIA can ameliorate lung ferroptosis caused by I/R injury. The study also utilized LY294002, a PI3K/Akt inhibitor, to further investigate this effect, finding that LY294002 reversed the ferroptosis-inhibitory effect of Tan IIA [187]. Salidroside, a glycoside derived from Rhodiola rosea, exhibits anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. Research shows that salidroside effectively reduces LPO and iron overload while enhancing the expression of ferroptosis-related proteins Nrf2, SLC7A11, and GPX4 in mice with LIRI. Additional studies using Nrf2 knockout mice and lung epithelial cell models have confirmed salidroside's ability to inhibit ferroptosis, thereby ameliorating LIRI [188]. According to existing research, the Nrf2/SLC7A11/GPX4 axis is involved in regulating ferroptosis in LIRI (Table 3).

Pulmonary hypertension

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a clinical and pathophysiological syndrome characterized by changes in pulmonary vascular structure or function, leading to increased pulmonary vascular resistance and pulmonary arterial pressure. The global prevalence of PH is estimated at approximately 1% and may rise to over 10% in individuals aged 65 years and above [189]. Currently, the primary clinical treatments for PH include basic therapy, specific treatments, surgical interventions, and targeted combination therapy [190]. However, there are relatively few studies on the role of ferroptosis in pulmonary hypertension. Monocrotaline (MCT), an alkaloid derived from Crotalaria pallida Ait, is an inducer of pulmonary hypertension that closely resembles human PH [191]. Research by Lan’s team found that MCT can induce ferroptosis in pulmonary artery endothelial cells (PAECs), and the use of ferroptosis inhibitors significantly reverses this effect [192, 193]. Astragaloside IV, a natural product, obstructs monocrotaline -induced pulmonary arterial hypertension by improving inflammation and pulmonary artery remodeling [194], but its specific mechanism of action remains unclear. Notably, studies have shown that Astragaloside IV can modulate ferroptosis and alleviate various diseases. It regulates the ferroptosis signaling pathway via the Nrf2/SLC7A11/GPX4 axis, thereby inhibiting PM2.5-mediated lung injury in mice [143]. Astragaloside IV also mitigates cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury through inhibition of the P62/Keap1/Nrf2 pathway-mediated ferroptosis [195]. Additionally, grape seed proanthocyanidin reduces inflammation and reverses pulmonary vascular remodeling in monocrotaline-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension [196, 197]. Such discoveries provide a theoretical basis and new perspectives for researchers to explore the treatment of pulmonary hypertension with natural products by regulating ferroptosis.

Discussion