Abstract

Background:

Polypharmacy is common in older adults starting cancer treatment and associated with increased risk of potentially inappropriate medications (PIM) and potential drug-drug interactions (PDI). We evaluated the association of medication measures with adverse outcomes in older adults with advanced cancer on systemic therapy.

Methods:

This secondary analysis from GAP 70+ Trial (NCT02054741; PI: Mohile) enrolled patients aged 70+ with advanced cancer who planned to start a new treatment regimen (n=718). Polypharmacy was assessed prior to initiation of treatment and defined as concurrent use of ≥8 medications. PIM were categorized using 2019 Beers criteria and Screening Tool of Older Persons’ Prescriptions. PDI were evaluated using Lexi-Interact Online®. Study outcomes were assessed within 3 months of treatment and included: 1) number of grade ≥2, grade ≥3 toxicities according to National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria; 2) treatment-related unplanned hospitalization; and 3) early treatment discontinuation. Multivariable regression models examined the association of medication measures with outcomes.

Results:

Mean age was 77 years and 57% had lung or gastrointestinal cancers. Median number of medications was 5 (0–24); 28% received ≥8 medications; 67% received ≥1 PIM; and 25% had ≥1 major PDI. Mean number of grade ≥2 toxicities for patients with polypharmacy was 9.8 versus 7.7 in patients without polypharmacy (adjusted β=1.87, standard error [SE]=0.71, P<0.01). Mean number of grade ≥3 toxicities for patients with polypharmacy was 2.9 versus 2.2 in patients without polypharmacy (adjusted β=0.59, SE=0.29, P=0.04). Patients with ≥1 major PDI had 59% higher odds of early treatment discontinuation (odds ratio 1.59, 95% confidence interval=1.03–2.46, P=0.03).

Conclusion:

In a cohort of older adults with advanced cancer, polypharmacy and PDI are associated with increased risk of adverse treatment outcomes. Providing meaningful screening and interventional tools to optimize medication use may improve treatment-related outcomes in these patients.

Keywords: Polypharmacy, outcomes, older adults, cancer

INTRODUCTION

Polypharmacy, the use of multiple concurrent medications,1,2 is a significant and growing public health issue among older adults with cancer.3 Risk factors for polypharmacy include patient-level factors such as advancing age,4 comorbidities,1 and disabilities,4 as well as healthcare system-level factors such as poor transitions of care, 4 care fragmentation,5 the use of multiple pharmacies, and prescribing cascades.6 Polypharmacy is most commonly defined in the literature as ≥5 medications,2,7 and the term excessive polypharmacy typically denotes the use of ≥10 medications.1 However, no universal consensus exists on these threshold values,4 and the suitability of any threshold may depend on the patient’s clinical presentation, the medication used, outcomes of interest, and the characteristics of the population.8 Our prior work has shown that a cut-off of ≥8 medications is associated with poorer physical function in older adults with advanced cancer starting a new treatment regimen.9 Studies in older adults without cancer have also demonstrated variable optimal thresholds associated with adverse outcomes such as frailty and mortality.7

Regardless of the precise numeric threshold, polypharmacy is particularly prevalent in older adults with cancer. Studies have estimated that up to 80% of these patients are taking ≥5 medications, and up to 40% are taking ≥10, significantly higher percentages than are typically reported in older community-dwelling patients without cancer.10 Polypharmacy increases the risk of taking one or more “potentially inappropriate medications” (PIM), with a higher risk than benefit in older adults. Additionally, pre-existing polypharmacy significantly increases the risk of clinically significant potential drug-drug interactions (PDI).8,11 Clinical consequences of PDI include unplanned hospitalizations and death.12

Data regarding prevalence and risks associated with polypharmacy in older adults with cancer remain relatively sparse and limited by inconsistent definitions, heterogeneous populations and study designs, variations in how medications are counted, and variable data sources (e.g., patient report, medical record, and claims data).10 Polypharmacy and PIM have been linked to a number of adverse outcomes in older adults with cancer, including postoperative complications, hospitalizations, and mortality, but these associations are not robust across all available studies.10 The associations between polypharmacy, PIM, and cancer treatment-related outcomes (such as toxicity and treatment dose decrease, delay, or discontinuation) remain unclear. In addition, studies are lacking about the prevalence of PDI and their impact on outcomes among older adults receiving systemic cancer treatment.

The goal of this study is to examine the associations between polypharmacy, PIM, and PDI and adverse cancer treatment outcomes in a large national cohort of older adults with advanced cancer receiving systemic treatment in community oncology settings.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

This is a secondary analysis of data from a nationwide, multicenter, cluster-randomized study, which aimed to assess whether providing information regarding geriatric assessment (GA) to community oncologists reduced clinician-rated grade 3–5 chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with advanced cancer starting a new cancer treatment regimen (Geriatric Assessment for Patients [GAP70+] study; University of Rochester Cancer Center [URCC] 13059, PI: Mohile; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02054741).13 The primary study was conducted by the University of Rochester Cancer Center (URCC) NCI Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) Research Base and approved by the Institutional Review Boards at participating sites. All participants provided written informed consent.

Eligible patients for the primary study were 1) aged ≥70 years, 2) diagnosed with incurable stage III/IV solid tumor or lymphoma, 3) impaired in at least one GA domain excluding the polypharmacy domain, and 4) planning to start a new cancer treatment regimen with a high risk of grade 3–5 toxicity based on Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), v4. Eligible regimens were determined based on enrolling physicians’ discretion and were reviewed by blinded clinical staff at the URCC Research Base. All participants were enrolled between July 2014 and March 2019.

Medication Review

A polypharmacy log was completed at baseline and prior to initiation of the new cancer treatment regimen for all the participants by a clinical research associate at each study site (supplementary table 1). This log captured all medications (prescription, over-the counter (OTC), and complementary medications) received by the patient within the prior two weeks and included medication name, dose, primary indication, start and end dates, frequency, and route of administration. Cancer therapies and supportive care medications (i.e., medications to treat the adverse effects of cancer treatment) were not included in this log. We decided not to include supportive care medications in any analyses, as they were only collected once at baseline and lacked information about duration and frequency of dosing.

Independent variables

Medication measures were included as independent variables. The medication count included all regular medications (both prescription and OTC medications, including complementary medications) received by the participants within 2 weeks of study enrollment. Polypharmacy was defined as ≥8 regular medications at baseline, based on our previous study showing that ≥8 medications is associated with physical functional impairments among older adults with advanced cancer receiving palliative chemotherapy.9 Antineoplastic therapies and supportive care medications specifically initiated in conjunction with cancer treatment were excluded. Polypharmacy was also assessed as a continuous independent variable (i.e. total number of regular medications received per patient excluding cancer treatments and supportive medications). PIMs were measured (0 versus ≥1) using two screening tools: the 2019 Beers criteria14, endorsed by the American Geriatrics Society, and the Screening Tool of Older Person’s Prescriptions (STOPP) criteria,15 a European screening tool developed based on expert consensus and evidence-based criteria. Potential drug-drug interactions (PDI) were characterized using Interact® Online as any category C (monitor therapy), D (consider therapy modification), or X (avoid combination) interactions between two regular (non-cancer treatment) drugs. Major PDI are any category D or X interactions.16 Lexi-Interact® Online was chosen as it focuses on depth and duplication of drug information, compares multiple sources of drug information, and displays clear and interpretable search results.

Study outcomes

Chemotherapy-related outcomes were assessed at 3 months and included: 1) total number of grade ≥2 toxicities according to CTCAE v4 (hematologic and nonhematologic); 2) total number of grade ≥3 toxicities; 3) unplanned treatment-related hospitalization; and 4) early treatment discontinuation due to toxicity.

Baseline covariates

Potential confounding factors were selected using directed acyclic graphs (DAG), used in epidemiological research to identify confounding variables that require conditioning when estimating causal effects.17 A single DAG was created for all the relationships between the independent variables and outcomes as we regarded the causal structure of the different models to be similar. The minimally sufficient set of adjustment variables was age (continuous variable), gender, cancer type, impaired comorbidity (yes versus no), impaired physical function (yes versus no), and impaired social support (yes versus no). As the parent study showed that toxicity was lower in the intervention arm, we included study arm (intervention versus usual care) as a covariate in all models. Definitions of impairment in comorbidity, physical function, and social support were described previously in the primary study (supplementary table 2).13

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed to describe medication measures and outcomes. Means and standard deviations were generated for continuous data, and proportions and frequencies for categorical data. Bivariate analyses were conducted to evaluate the association between each of the key independent variables [polypharmacy (≥8 medications versus < 8), PIM (yes versus no), any major PDI (yes versus no)] and outcomes. In a sensitivity analysis, we assessed polypharmacy using the most commonly used cutoff value in the literature (≥5 medications versus <5). Pearson’s χ2 test was used for binary categorical outcomes (unplanned treatment-related hospitalization and early treatment discontinuation) and independent t-test was used for continuous outcomes (number of grade ≥2 and grade ≥3 toxicities). Independent variables with p-value <0.2 in bivariate analyses were selected for inclusion in the final models.

Separate multivariable models were created to examine the association between baseline medication measures with p<0.2 in bivariate analysis and outcomes. Multivariable linear regression models were used for continuous outcomes while multivariable logistic regression models were used for categorical outcomes. All models included age, gender, cancer type, impaired comorbidity, impaired physical function, impaired social support, and study arm as covariates.

We computed 95% confidence intervals as a measure of statistical precision. Two-sided p-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted with SAS 9.4.

RESULTS

Study Population Characteristics and Treatment (Table 1)

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of study participants stratified by number of received medications

| Variable | Category | All patients | Polypharmacy (≥8 medications) | No polypharmacy (<8 medications) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 718 (100%) | 198 (27.7%) | 520 (72.3%) | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 77.2 (5.2) | 77.3 (5.5) | 77.2 (5.4) | |

| Gender a | Male | 405 (56.4%) | 105 (52.5%) | 300 (57.9% |

| Female | 311 (43.3%) | 94 (47.5%) | 217 (42.1%) | |

| Race b | White | 628 (87.5%) | 178 (89.9%) | 450 (87.2%) |

| Black | 52 (7.2%) | 12 (6.1%) | 40 (7.8%) | |

| Others | 35 (4.9%) | 7 (4.0%) | 28 (5.1%) | |

| Education a | Less than high school | 111 (15.5%) | 26 (13.1%) | 85 (16.5%) |

| High school | 244 (34.0%) | 70 (4.9%) | 174 (33.7%) | |

| College or above | 361 (50.3%) | 103 (52.0%) | 258 (49.9%) | |

| Income a | ≤$50,000 | 371 (51.7%) | 100 (50.0%) | 271 (52.3%) |

| >50,000 | 190 (26.5%) | 136 (26.4%) | 54 (27.3%) | |

| Declined to answer | 155 (21.6%) | 45 (22.7%) | 110 (21.3%) | |

| Marital status a | Single, never married | 17 (2.4%) | 5 (2.1%) | 12 (2.3%) |

| Married/ domestic partnership | 449 (62.5%) | 129 (64.7%) | 320 (62.0%) | |

| Separated/ widowed/ divorced | 250 (34.8%) | 66 (33.3%) | 184 (35.7%) | |

| Cancer type | Gastrointestinal | 247 (34.2%) | 63 (31.4%) | 184 (35.4%) |

| Genitourinary | 109 (15.2%) | 26 (13.1%) | 83 (16.0%) | |

| Gynecological | 43 (6.0%) | 16 (8.1%) | 27 (5.2%) | |

| Breast | 56 (7.8%) | 12 (6.1%) | 44 (8.5%) | |

| Lung | 180 (25.1%) | 62 (31.3%) | 118 (22.8%) | |

| Others | 37 (5.3%) | 9 (4.6%) | 28 (5.4%) | |

| Cancer stage | Stage 3 | 77 (10.7%) | 26 (13.1%) | 51 (9.9%) |

| Stage 4 | 628 (87.5%) | 168 (84.4%) | 460 (88.6%) | |

| Others | 13 (1.8%) | 5 (2.5%) | 8 (1.5%) | |

| Functional status | Non-impaired | 306 (42.5%) | 69 (34.8%) | 237 (45.6%) |

| Impaired | 412 (57.5%) | 129 (65.2%) | 283 (54.4%) | |

| Physical performance | Non-impaired | 49 (6.8%) | 6 (3.0%) | 43 (8.2%) |

| Impaired | 669 (93.2%) | 193 (97.0%) | 476 (91.9%) | |

| Comorbidity | Non-impaired | 234 (32.5%) | 24 (11.7%) | 210 (40.4%) |

| Impaired | 484 (67.5%) | 175 (88.4%) | 309 (59.7%) | |

| Nutritional status | Non-impaired | 279 (38.9%) | 64 (32.3%) | 215 (41.5%) |

| Impaired | 439 (61.1%) | 135 (67.7%) | 304 (58.5%) | |

| Social support | Non-impaired | 524 (72.9%) | 143 (71.7%) | 381 (73.4%) |

| Impaired | 194 (27.1%) | 56 (28.4%) | 138 (26.6%) | |

| Psychological health | Non-impaired | 513 (71.4%) | 140 (70.3%) | 373 (72.0%) |

| Impaired | 205 (28.6%) | 60 (29.9%) | 145 (28.0%) | |

| Cognition | Non-impaired | 457 (65.6%) | 121 (61.1%) | 336 (64.8%) |

| Impaired | 261 (36.4%) | 183 (35.1%) | 78 (38.9%) |

2 patient had missing data

3 had missing data

The mean age of participants (n=718) was 77.2 years (standard deviation [SD] 5.2 years; range 70–94). Overall, 56.4% were males, 87.5% were non-Hispanic white and 87.5% had stage 4 cancer. The most common cancer types were gastrointestinal (n= 246, 34.2%) and lung (n=180, 25.1%). The patient characteristics are further described in Table 1.

The median number of regular medications was 5 (range, 0–24). Of the 718 patients, 61.3% (n=440) received ≥5 concurrent medications, 27.7% (n= 198) received ≥8 concurrent medications, and 14.5% (n=104) received ≥10 concurrent medications. A total of 447 patients (62.3%) received at least one PIM based on the 2019 AGS Beers Criteria (range, 0–8 PIM). Twenty-nine percent of patients (n=206) received at least one PIM based on STOPP screening criteria. Applying both tools, 482 patients (67.1%) received ≥1 PIM.

There were 1,854 PDI identified among 490 patients. Of these, 1,589 were category C affecting 64.3% of patients, 280 were category D in 22.0% of patients, and 34 were category X in 4.2% of the participants. Twenty-five percent (n=177) of the study participants had at least one potential major PDI (D or X category).

The mean number of grade ≥2 toxicities reported by the patients was 8 (SD 8.3, range 0–57). The mean number of grade ≥3 toxicities reported was 2.4 (SD 3.3, range 0–25). Among study participants, 25% (n=178) experienced unplanned treatment-related hospitalization within 3 months of treatment initiation, and 18% (n=126) had early treatment discontinuation.

Association of polypharmacy with treatment adverse outcomes

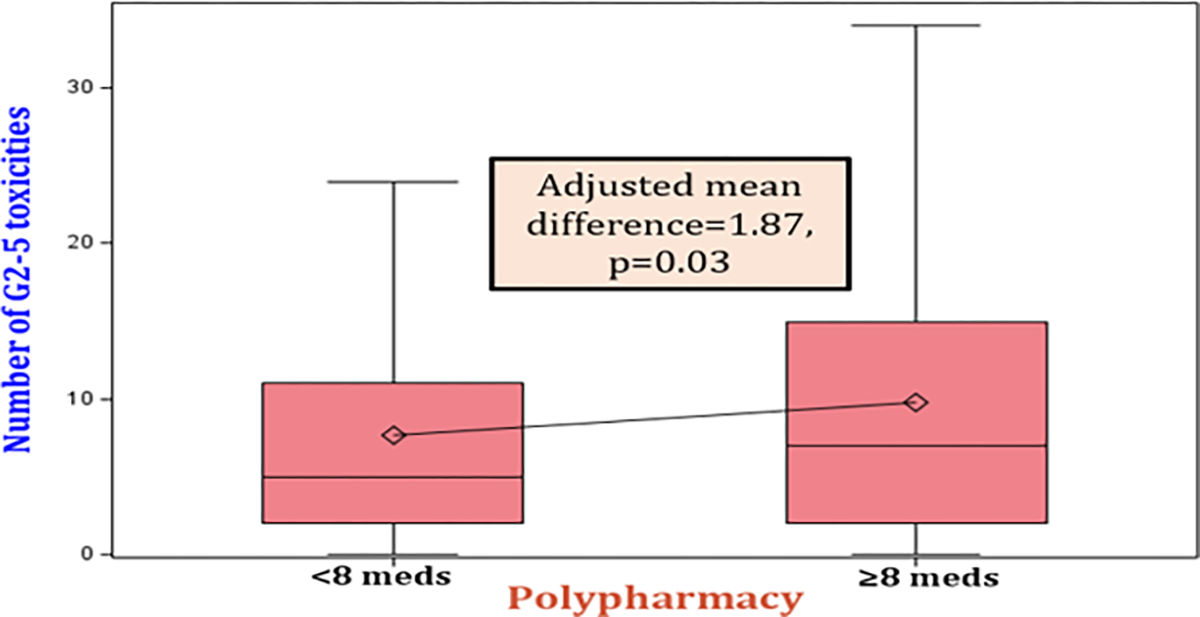

The mean number of chemotherapy grade ≥2 toxicities for those who received ≥8 concurrent medications was 9.8, compared to 7.7 in patients receiving <8 medications (p<0.01). In multivariable analysis and after adjusting for covariates, those who received ≥8 concurrent medications had a mean of 2 additional grade ≥2 toxicities compared to those who received < 8 medications (β=1.87, SE=0.71, p<0.01) (figure 1, table 2). We also found a positive correlation between total number of medications and number of grade ≥2 toxicities (p=0.03). This association remained significant after adjusting by potential covariates (adjusted β=0.21, SE=0.10, p=0.03) (table 2).

Figure 1:

Box plot showing the adjusted mean difference for the number of grade 2–5 toxicities among those who received ≥ 8 medications versus < 8 medications

Table 2:

Mean difference in number of toxicities (grade ≥2 and grade ≥3) among different categories of polypharmacy, PIM, and major PDI

| Predictor/ outcome | Mean difference in number of grade ≥ 2 toxicities | Mean difference in number of grade ≥ 3 toxicities | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted model | Adjusted model * | Unadjusted model | Adjusted model * | |

| Polypharmacy (≥8 versus <8) | 2.10 (8.25)** | 1.87 (0.71)** | 0.67 (3.30)** | 0.59 (0.29)** |

| Polypharmacy (continuous)*** | 0.24 (0.09)** | 0.21 (0.10)** | 0.07 (0.04)** | 0.06 (0.04) |

| PIM (yes versus no) | 0.41 (8.31) | -- | 0.19 (3.31) | -- |

| Major PDI (yes versus no) | 0.07 (8.31) | -- | 0.21 (3.31) | -- |

Abbreviations: PDI, potential drug-drug interactions; PIM: potentially inappropriate medications

Models are adjusted for age, cancer type, gender, comorbidity, function, social support, and study arm

P<0.05

effect estimate is correlation coefficient

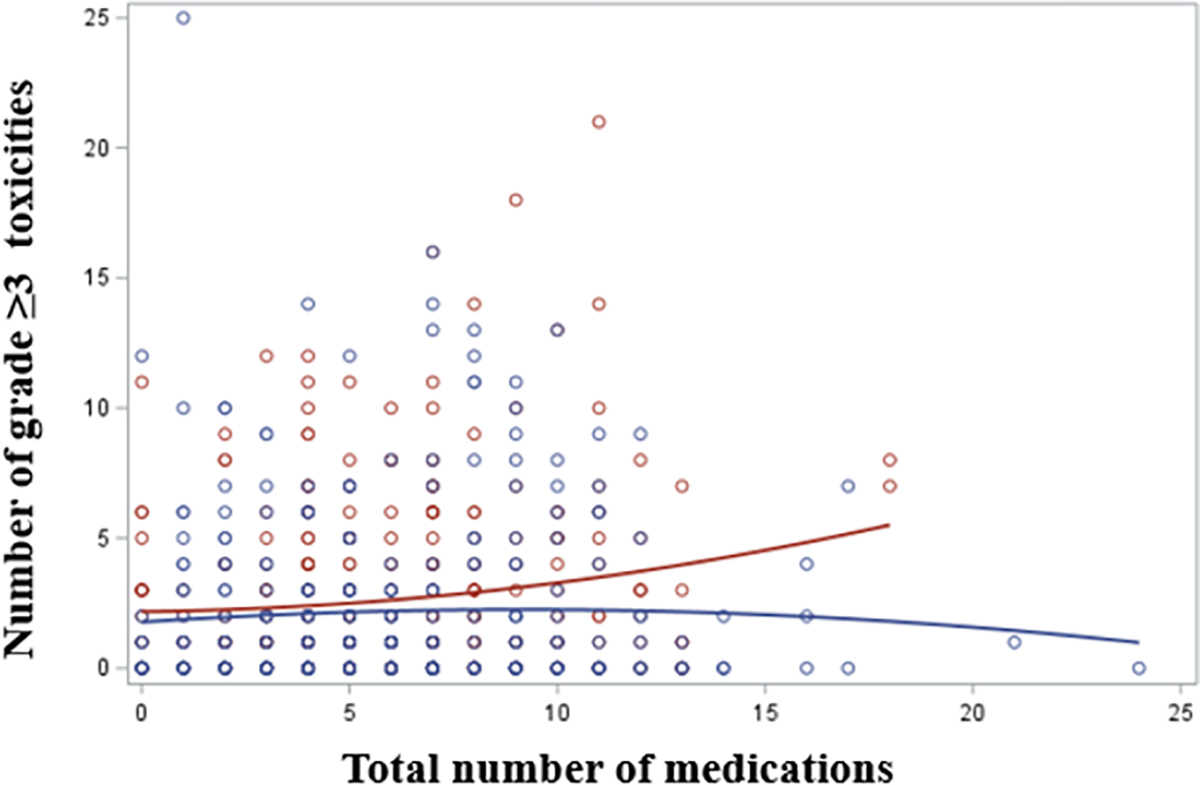

The mean number of chemotherapy grade ≥3 toxicities for those who received ≥8 concurrent medications was 2.9, compared to 2.2 in patients receiving < 8 medications (p=<0.01). This association remained significant after adjusting by potential covariates (β=0.59, SE=0.29, p=0.04) (table 2). The association between polypharmacy and number of grade ≥3 toxicities was more pronounced among participants in the usual care arm compared to GA arm. Figure 2 shows a scatter plot for the association between total number of received medications (X axis) and number grade ≥3 toxicities (Y axis) stratified by study arm. Taking ≥5 concurrent medications was not associated with number of chemotherapy toxicities. There was no significant association between polypharmacy (≥8 medications) and hospitalization or early treatment discontinuation (all p-values >0.05) (table 3).

Figure 2:

Scatter plot for the association between total number of received medications (X axis) and number of G3–5 toxicities (Y axis) stratified by study arm (red; usual care arm, blue; intervention arm). The association between polypharmacy and number of grade ≥3 toxicities was more pronounced among participants in the usual care arm compared to intervention arm.

Table 3:

Odds of hospitalization and early treatment discontinuation among different categories of polypharmacy, PIM, and major PDI

| Predictor/ outcome | Odds of unplanned hospitalization OR (95% CI) |

Odds of Early discontinuation OR (95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted model | Adjusted model * | Unadjusted model | Adjusted model * | |

| Polypharmacy (≥8 versus <8) | 1.19 (0.82–1.73) | -- | 1.01 (0.66–1.55) | -- |

| Polypharmacy (continuous) | 1.05** (1.01–1.12) | 1.03 (0.97–1.08) | 1.02 (0.97–1.08) | -- |

| PIM (yes versus no) | 1.36** (0.94–1.97) | 1.19 (0.81–1.75) | 0.9 (0.60–1.36) | -- |

| Major PDI (yes versus no) | 0.78 (0.52–1.18) | -- | 1.48** (0.97–2.25) | 1.59** (1.03–2.46) |

Abbreviations: PDI, potential drug-drug interactions; PIM: potentially inappropriate medications

Models are adjusted for age, cancer type, gender, comorbidity, function, social support, and study arm

P<0.05

Association of PIM and PDI with treatment adverse outcomes

In bivariate analysis, older adults with advanced cancer who received ≥1 PIM had 36% higher odds of unplanned treatment-related hospitalization compared to those who did not receive PIM (odds ratio (OR)=1.36; CI 0.94–1.97). After adjustment for covariates, those who received ≥1 PIM had 19% increased odds of unplanned hospitalization compared to those who did not receive PIM. However, this association was not statistically significant (OR=1.19; CI= 0.81–1.75) (table 3).

Older adults with advanced cancer who had ≥1 major PDI had 48% higher odds of early treatment discontinuation compared to those without major PDI. After adjustment for covariates, those with ≥1 major PDI had a 59% increased odds of early treatment discontinuation (OR 1.59, CI=1.03–2.46) (table 3).

DISCUSSION

In this secondary analysis of a large cohort of older adults with advanced cancer starting a new treatment regimen with high risk of toxicity in the community oncology setting, we identified a high prevalence of polypharmacy (61% taking ≥5 medications and 28% taking ≥8 medications); PIMs (67% taking ≥1 PIM by either Beers or STOPP criteria); and PDI (25% had ≥1 major PDI according to Lexi-Interact® Online software) prior to initiation of treatment. We found that polypharmacy (≥8 medications) was independently associated with increased risk of clinician-rated treatment toxicity. In addition, PDI were associated with increased risk of early treatment discontinuation. This analysis addresses an important gap in the literature by examining the medication risks regarding polypharmacy, PIM, and PDI among a cohort of older adults with advanced cancer and aging-related conditions. To our knowledge, this is the first study to find an association between PDI and adverse systemic treatment outcomes in this vulnerable population.

In this study, older adults with polypharmacy (defined as receipt of ≥8 concomitant medications) had a higher average number of grade ≥ 3 (i.e. serious) treatment-related toxicities compared to older adults without polypharmacy. We also demonstrated a correlation between number of concurrent drugs administered and number of treatment-related toxicities. These findings supplement those of prior studies18,19. In a systematic review and meta-analysis of older adults with cancer (all cancer stages), the authors report a 22% increased risk of grade ≥ 3 toxicities for patients with polypharmacy (≥5 medications) compared to those without polypharmacy20. They also reported associations between polypharmacy and all-cause mortality, hospitalization and postoperative complications. Unlike prior studies, our study focused exclusively on a vulnerable population that is historically underrepresented in clinical trials: older adults with advanced cancer and aging-related conditions receiving care in community oncology clinics. This might explain why the current analysis did not find an association between polypharmacy and adverse outcomes when a cut-off ≥ 5 medications was used, which supports the notion that appropriateness of any cut-point to define polypharmacy may vary based on the nature of the population. Moreover, we demonstrated that the association between polypharmacy and number of clinician-rated toxicities was stronger among those in the usual care arm compared to those in a GA intervention arm. This observation suggests that GA guided care may have mitigated the risk of polypharmacy on treatment-related outcomes. This supplements prior findings from this trial that the GA intervention increased polypharmacy discussions and medication management among older adults with advanced cancer.21

Interestingly, we found an association between polypharmacy and increased risk of grade ≥2 toxicities (low-grade toxicities). A prior study indicated that low-grade toxicities have clinical significance in older adults undergoing chemotherapy, as these patients may have a lower ability to tolerate symptomatic toxicities due to concurrent functional decline and comorbidities.22 In the same study, many older patients were not able to complete treatment as planned or had secondary treatment modification due to these toxicities. Our results reinforce the potential significance of grade 2 toxicities in this population.

We found that 25% of our study cohort was exposed to at least one “major” PDI even before initiation of their cancer therapy. We also demonstrated that older adults with advanced cancer who had ≥1 major PDI had increased risk of early treatment discontinuation due to toxicity. There are very limited studies examining the prevalence of PDI and their relationship with treatment outcomes in older adults with cancer. Yeoh et al. found that 55% of older patients with cancer are exposed to PDI (levels C, D, and X).23 In another study, Popa et al. (using the Drug Interactions Facts software) 24 found that the risk of severe non-hematological toxicity doubled with each level 1 PDI (potentially severe or life-threatening interaction), and tripled with each level 1 PDI involving chemotherapeutics.11 Currently, integrated usage of medication interaction software is feasible due to widespread implementation of electronic health records and prescriptions. Although PDI cannot be completely avoided, awareness could result in adjustments to treatment dosing or surveillance.

In our study, 2/3 of the participants received ≥1 PIM by either the Beers or STOPP criteria, which is greater than prior studies where estimates range from 19% to 52%.10 Similar to previous studies, we did not find an independent association between PIM and increased risk of adverse outcomes.25,26 It is worth noting that existing criteria and tools used to determine PIM are primarily derived from the general geriatric (non-cancer) population and have not been tailored specifically for older adults with cancer,27 raising questions about the generalizability of these tools, especially among older adults with cancer, age-related impairments, and limited life expectancy.

The associations between polypharmacy, PDI, and adverse treatment outcomes among older adults with advanced cancer suggest the need for medication screening and interventional tools to improve outcomes among this vulnerable population. For instance, “deprescribing” (the planned discontinuation of medications) can reduce the number of PIMs, falls, and mortality in older adults without cancer.28 Among older adults with cancer, recent National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines support performing careful medication review before initiating chemotherapy. 29 The guidelines have listed the key elements including identifying polypharmacy and PIM, reviewing medication indication and dose appropriateness, assessing polypharmacy and PIM, assessing adherence and drug interactions, and deprescribing inappropriate or unnecessary medication.

A major strength of our study is its understudied population: older adults with advanced cancer receiving treatment in community oncology (i.e., real-world) practices who are at a high risk of cancer treatment adverse effects.13 Unlike many prior studies, we included OTC and complementary medications, which are rarely accounted for but are often PIMs and/or are involved in PDI. 30 Additionally, we adjusted for confounding by indication by including patients’ comorbidities and functional status as covariates in the multivariable models. In a recent systematic review, we demonstrated that most existing studies evaluated polypharmacy as a covariate or risk factor within a larger exploration of many potential risk factors, which may have created residual confounding issues and spurious associations between medication measures and treatment adverse outcomes.10

This study also has several limitations. First, medications were captured at a single time point, and we were unable to assess medication changes over the course of cancer treatment. Second, we were not able to consider other medication variables beyond count (such as indication, dosage, directions for use, and duration of use) due to missing data. Third, our study participants were primarily white and well-educated, and our findings might not be generalizable to other groups.

In conclusion, in a large sample of older adults with advanced cancer and aging-related conditions receiving systemic treatment within community oncology settings, we found that polypharmacy and major PDI are common and associated with increased risk of adverse treatment outcomes. Our findings emphasize the need to critically evaluate the utility and safety of every medication before initiation of cancer treatment. They also underscore the need to develop and test interventions to address polypharmacy and PDI in older patients with cancer, with the goal of improving treatment outcomes in these patients.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

The work was funded through U01CA233167 (S.M.), K24 AG056589 (S.M.), NIA R21/R33AG059206 (S.M.), NCI K08CA248721 (E.R.), and NIA R03AG067977 (E.R.).

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Mohile received funding from Carevive for other projects. Dr. Loh serves as a consultant to Pfizer and Seattle Genetics. Dr. Ramsdale received honoraria from Flatiron Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, Caughey GE. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr 2017;17:230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pazan F, Wehling M. Polypharmacy in older adults: a narrative review of definitions, epidemiology and consequences. Eur Geriatr Med 2021;12:443–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A . Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halli-Tierney AD, Scarbrough C, Carroll D. Polypharmacy: Evaluating Risks and Deprescribing. Am Fam Physician 2019;100:32–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurczewska-Michalak M, Lewek P, Jankowska-Polańska B, et al. Polypharmacy Management in the Older Adults: A Scoping Review of Available Interventions. Front Pharmacol 2021;12:734045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dahal R, Bista S. Strategies To Reduce Polypharmacy in the Elderly. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2022, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Blyth FM, et al. High-risk prescribing and incidence of frailty among older community-dwelling men. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2012;91:521–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maher RL, Hanlon J, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2014;13:57–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohamed MR, Ramsdale E, Loh KP, et al. Association of Polypharmacy and Potentially Inappropriate Medications With Physical Functional Impairments in Older Adults With Cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2021:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohamed MR, Ramsdale E, Loh KP, et al. Associations of Polypharmacy and Inappropriate Medications with Adverse Outcomes in Older Adults with Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oncologist 2020;25:e94–e108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Popa MA, Wallace KJ, Brunello A, Extermann M, Balducci L. Potential drug interactions and chemotoxicity in older patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy. J Geriatr Oncol 2014;5:307–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Błeszyńska E, Wierucki Ł, Zdrojewski T, Renke M. Pharmacological Interactions in the Elderly. Medicina (Kaunas) 2020;56:320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohile SG, Mohamed MR, Xu H, et al. Evaluation of geriatric assessment and management on the toxic effects of cancer treatment (GAP70+): a cluster-randomised study. The Lancet 2021;398:1894–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67:674–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, O’Connor MN, Ryan C, Gallagher P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing 2015;44:213–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chatfield AJ. Lexicomp Online and Micromedex 2.0. J Med Libr Assoc 2015;103:112–3. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tennant PWG, Murray EJ, Arnold KF, et al. Use of directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) to identify confounders in applied health research: review and recommendations. Int J Epidemiol 2021;50:620–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woopen H, Richter R, Ismaeel F, et al. The influence of polypharmacy on grade III/IV toxicity, prior discontinuation of chemotherapy and overall survival in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2016;140:554–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sasaki T, Fujita K, Sunakawa Y, et al. Concomitant polypharmacy is associated with irinotecan-related adverse drug reactions in patients with cancer. Int J Clin Oncol 2013;18:735–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen LJ, Trares K, Laetsch DC, Nguyen TNM, Brenner H, Schöttker B. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on the Associations of Polypharmacy and Potentially Inappropriate Medication With Adverse Outcomes in Older Cancer Patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2021;76:1044–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramsdale E, Lemelman T, Loh KP, et al. Geriatric assessment-driven polypharmacy discussions between oncologists, older patients, and their caregivers. J Geriatr Oncol 2018;9:534–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalsi T, Babic-Illman G, Fields P, et al. The impact of low-grade toxicity in older people with cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Br J Cancer 2014;111:2224–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeoh TT, Tay XY, Si P, Chew L. Drug-related problems in elderly patients with cancer receiving outpatient chemotherapy. J Geriatr Oncol 2015;6:280–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roblek T, Vaupotic T, Mrhar A, Lainscak M. Drug-drug interaction software in clinical practice: a systematic review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2015;71:131–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maggiore RJ, Dale W, Gross CP, et al. Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults with cancer undergoing chemotherapy: effect on chemotherapy-related toxicity and hospitalization during treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62:1505–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elliot K, Tooze JA, Geller R, et al. The prognostic importance of polypharmacy in older adults treated for acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). Leuk Res 2014;38:1184–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nightingale G, Mohamed MR, Holmes HM, et al. Research priorities to address polypharmacy in older adults with cancer. Journal of Geriatric Oncology 2021;12:964–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whitman A, DeGregory K, Morris A, Mohile S, Ramsdale E. Pharmacist-led medication assessment and deprescribing intervention for older adults with cancer and polypharmacy: a pilot study. Support Care Cancer 2018;26:4105–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hshieh TT, Dumontier C, Jaung T, et al. Impact of Polypharmacy and Potentially Inappropriate Medications Among Older Adults with Blood Cancers. Blood 2021;138:4089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramsdale E, Mohamed M, Yu V, et al. Polypharmacy, Potentially Inappropriate Medications, and Drug-Drug Interactions in Vulnerable Older Adults With Advanced Cancer Initiating Cancer Treatment. The Oncologist 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.