Abstract

Background:

Community-engaged data collection offers an important opportunity to build community capacity to harness the power of data and create social change.

Objectives:

To share lessons learned from engaging 16 adolescents and young adults from a partner community to collect data for a public opinion survey as part of a broader community-based participatory research (CBPR) project.

Methods:

We conducted an analysis of archival documents, process data, and an assessment of survey assistants’ experiences.

Lessons Learned:

High-quality data were collected from a hard-to-reach population. Survey assistants benefited from exposure to research and gained professional skills. Key challenges included conducting surveys in challenging environments and managing schedule constraints during the school year. The tremendous investment made by project partners was vital for success.

Conclusions:

Investments required to support engaged data collection were larger than anticipated, as were the rewards, prompting greater attention to the integration of adolescents and young adults in research efforts.

Keywords: Community-engaged research, adolescents, young adults, youth, data collection, community-based participatory research, community health research, health disparities, health promotion, process issues, North America, socioeconomic factors, students, vulnerable populations

INTRODUCTION

Action at the community level is vital to address the enduring and challenging health inequalities present in the United States.1 Community-engaged research supports such action by integrating social justice perspectives with an emphasis on participation, research, and action for the benefit of stakeholders.2,3 Ideally, stakeholders are engaged throughout the research process (including issue selection, data collection and analysis, interpretation of results, and utilization of acquired knowledge), which increases the likelihood of generating practical, acceptable solutions, and capacity among individuals and communities.4–7 However, there is variation in involvement and the data-intensive phase is not typically one in which stakeholder engagement is strong.4 Potential barriers include perceptions that involvement is inefficient because it does not make use of researcher capacity/leverage existing community capacity, constraints on the time and resources required to engage in this phase of research in addition to others, and time pressures to complete the analysis.7,8

Skills for the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data are vital for community-driven problem identification and solution development.9 Benefits of community engagement with data include refinement of study instruments, nuanced interpretation and translation of findings, increased understanding of the strengths and limitations of data collection vehicles (e.g., surveys), integration of data into planning efforts, improved communication among stakeholders, and increased capacity for research to support community goals.8 More broadly—and perhaps more importantly in the long term—community engagement with data supports community attempts to generate, evaluate, and/or leverage data to inform action for social change.

Engaging community members in data collection and analysis offers an opportunity to build capacity to leverage the power of data. Here, we report on a capacity-building effort to train young people from a partner community to collect survey data. Project IMPACT (Influencing Media and Public Agenda on Cancer and Tobacco Disparities) is a National Institutes of Health–funded CBPR project. It aims to change the public agenda on health- and tobacco-related inequalities in Lawrence, Massachusetts, by training staff of community-based organizations on strategic media engagement. Project IMPACT was developed after long-standing community partners identified this capacity need during an earlier CBPR project.10 The project is led by a Community Project Advisory Committee (C-PAC) composed of investigators, study staff, and community partners, including representatives of community-based organizations, local educational institutions, the Department of Public Health, and a local health-focused coalition. A subset of C-PAC members has been collaborating for 10 years in a series of CBPR studies addressing cancer inequalities.

The administration of a public opinion survey was an important component of Project IMPACT. The initial plan was to hire an outside research firm to conduct the survey, but the C-PAC identified adolescents and young adults as an important community resource that could be developed and leveraged to meet research objectives. The decision of whether and how to engage this group was complex. Potential benefits of engaging adolescents and young adults in data collection include capacity building, leveraging familiarity with the community, availability of human resources, and cost savings versus employing adults.5,11 Exposure to participatory research endeavors can have important impacts on the adolescents and young adults involved (particularly from a career development standpoint) as well as the broader community.12 At the same time, adolescents and young adults may face challenges related to asking sensitive questions, hesitation among adult respondents to speak with young people, training requirements, supervision and support requirements, and scheduling restrictions.5,11 The C-PAC determined that benefits to the community would outweigh costs. They felt that capacity building among young people was consistent with the broader goals of the project and 10-year partnership—supporting community members to create change and address inequalities. They also wanted to address gaps facing local students in terms of access to role models in science, research opportunities, and professional development. With this in mind, the C-PAC decided to recruit 16 students to become survey assistants. Community partners and researchers co-developed the capacity-building effort and partnered in the evaluation. One community partner (V.L.) co-authored this paper; all members of the C-PAC are recognized in the Acknowledgements section.

Although Project IMPACT uses principles of CBPR and emphasizes full partnership among stakeholders, the data collection effort is best described as community-engaged research. This distinction is important, because key stakeholders and partners were organizations and community leaders who engaged in the project with the power sharing, equity, and benefits of CBPR efforts. The young people employed and trained as survey assistants were brought into the project as community members who could benefit from and contribute to a discrete portion of the project, but were not engaged as partners.

The academic team’s work with Project IMPACT and other participatory projects in Lawrence is guided by the Participatory Knowledge Translation (PaKT) Framework, which integrates knowledge translation and participatory approaches to support communities in creating sustainable social change that achieves community goals and reduces health inequalities.13

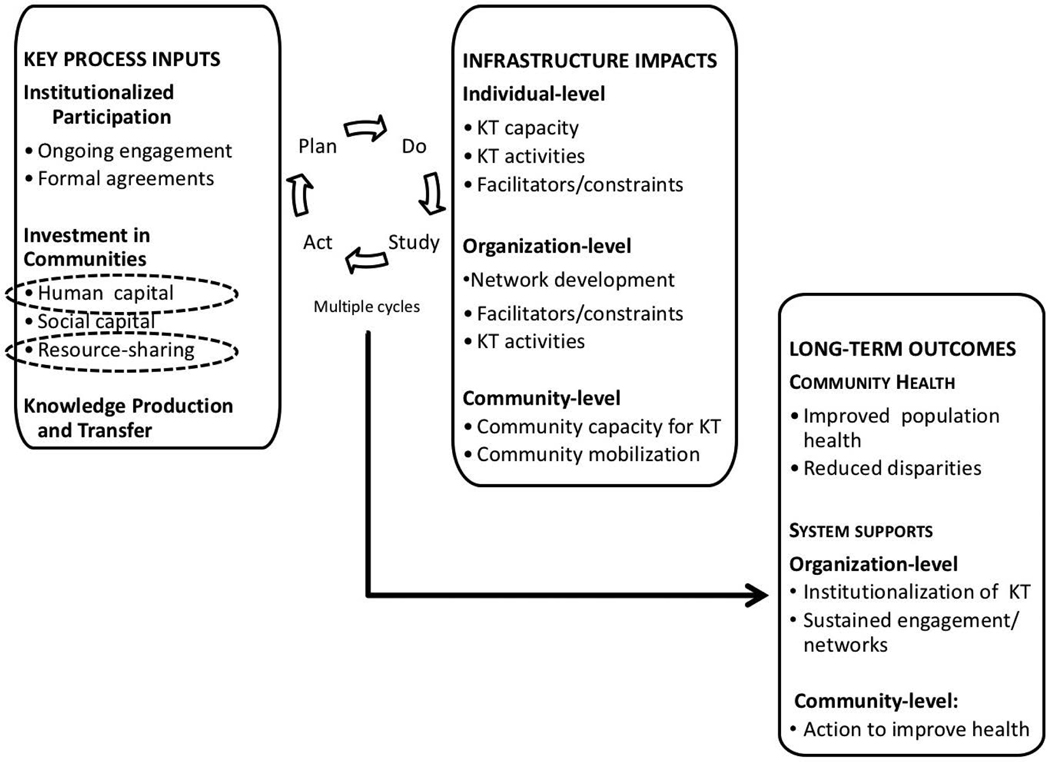

As seen in Figure 1, the PaKT framework emphasizes three key inputs: structured participation, investment in communities (the focus of this assessment), and knowledge production and transfer. These inputs lead to infrastructure changes at multiple levels, emphasizing knowledge translation capacity and activities. Outcomes include improved community health and reduced inequalities, system changes to sustain knowledge translation, and community-level action.

Figure 1.

The participatory knowledge translation (PaKT) framework. Relevant components are highlighted.

METHODS

Intervention Setting

Lawrence is a former mill town located 25 miles north of Boston, with about 76,000 residents, more than 70% of whom identify as Hispanic or Latino. Approximately 29% of residents live with incomes below the federal poverty level14 and residents experience health inequalities in obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and certain cancers.15 Yet the city is also home to vibrant nonprofit, government, and other sectors addressing health issues and intersectoral collaborations to address health are a unique resource of this community.

Public Opinion Survey

We developed a population-based sampling frame of adults across Lawrence’s 11 neighborhoods. Door-to-door in-person surveys were chosen to increase completion rates16 and participation by vulnerable populations.17 The survey contained 55 items on topics including health behaviors, media use, attribution of causes of health inequalities, and discrimination. It also included nutrition and exercise items to meet partners’ needs. Survey completion time ranged from 20 to 65 minutes and respondents received gift cards in appreciation for their time.

Survey Assistants

Sixteen survey assistants were recruited (8 each from Lawrence High School and Northern Essex Community College). They were recruited based on the following criteria: student in health-focused track, self-identification as Latino/ Hispanic, and report of being bilingual in English and Spanish. At the start of data collection, 15 survey assistants were 17 to 24 years old; one student at the community college was 40 years old.

Data Sources and Analysis

Data sources were mainly process evaluation documents, including training materials, study protocols, and logs kept by survey assistants and site supervisors. We also used observational notes from survey assistants, site supervisors and researchers and invoices and time sheets. We surveyed survey assistants in March 2014 (2.5 years after) to assess long-term impacts of the program (11 of 16 responded). We used the PaKT framework to organize the data and assess lessons learned. A subset of researchers, supervisors, and community partners created, debated, and refined the lessons learned. All research procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Harvard School of Public Health.

INVESTMENTS

Human Capital: Capacity Building

In August 2011, survey assistants spent 2 half-day sessions learning about project goals, health inequalities, social determinants of health, survey methods and techniques, research ethics, and the survey instrument. They practiced survey administration with peers, researchers, and community volunteers. Survey assistants wore shirts with a prominent project logo and identification badges while in the field and worked in teams of two or three (one high school student, one community college student, and one from either group or a member of the study staff). Teams were mixed to facilitate mentoring, skills transfer, and social support.18 Surveys were conducted in one neighborhood at a time, with one supervisor present and another on call. To increase support, the C-PAC sent information about the survey to police, city councilors, and neighborhood groups and advertised through local media. Surveys were fielded between August and December 2011.

Ongoing Feedback from Researchers and Site Supervisors

Researchers accompanied teams at the outset of data collection, conducted field visits 2 months into the process, and conducted periodic site visits to observe and mentor survey assistants. Summary reports were positive and highlighted survey assistants’ ability to administer the survey in challenging situations (e.g., facing noncooperative respondents). Having researchers readily available also gave survey assistants a chance to ask questions (e.g., the rationale for asking questions about politics in a survey about health). Three site supervisors were engaged, one from each educational institution and a staff member from the partner coalition. Study staff served as additional site supervisors when needed. These supervisors were invaluable for ensuring the safety of survey assistants and providing mentorship and support.

Ongoing Tracking and Process Evaluation

Survey assistants completed daily logs to track survey completion, refusals, and nonresponse. Survey assistants and staff also provided written observations of their experience (e.g., irregularities or relevant trends). The use of ongoing process evaluation to support quality improvement19 allowed the study team to make necessary adjustments. For example, despite identifying as bilingual, not all survey assistants were able to conduct interviews in both languages and team composition was adjusted to ensure the ability of the team to complete the task.

Human Capital: Exposure to Research and Health Careers

The study team held several events to engage survey assistants after data collection ended. First, survey assistants were invited to the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center to learn about public health research careers. They met with a patient navigator, a cultural anthropologist, a survey methodologist, and a thoracic medical oncologist and learned about internship opportunities. Second, researchers helped survey assistants to analyze collected data for a research question they posed (the link between social determinants and red meat consumption). The activity was well-received, but only four survey assistants participated. Third, survey assistants, researchers, and a member of the C-PAC participated in a community career fair, where survey assistants shared their research experiences. Finally, survey assistants shared their experiences with the partner health coalition in Lawrence.

Resource Sharing

Resource sharing for Project IMPACT included stipends to partner organizations and in-kind contribution of time from a community health educator based in Lawrence. The data collection effort included two additional streams of resource-sharing. First, at the C-PAC’s recommendation, survey assistants were paid an hourly rate of $12. The project also employed site supervisors. Payments to survey assistants and site supervisors totaled approximately $50,000. This excludes the salary of the community college staff member, whose time was donated by her institution. Second, we estimate that data collection required $45,000 worth of staff salaries for the study team and a substantial amount of donated time, including the time of the Lawrence-based community health educator (530 hours), an assistant project director (160 hours), post-doctoral fellows (200 hours), a doctoral student (80 hours), and investigators (100 hours). Cost effectiveness is difficult to judge in this case. This public opinion survey cost about $95,000 excluding donated time. We were unable to find recent cost estimates for similar surveys in the literature and solicited estimates from experts on the American Association for Public Opinion Research listserv. We received a range of responses, with estimates from $75,000 to $200,000 for this survey method, number of responses, and target population.

LESSONS LEARNED

Diverse Benefits to Survey Assistants

The effort’s success was highlighted by diverse benefits of participation for survey assistants. First, they learned about research methods, such as probability-based sampling methods. When we contacted survey assistants in 2014, most (10/11) reported that participation increased their interest in research. Many high school students reported using their experience as part of college applications. Second, survey assistants engaged critically with survey content and discussed issues related to health inequalities and social determinants of health with others, including family members. In the 2014 assessment, most (10/11) reported that participation increased their interest in health inequalities. Third, study team members observed that survey assistants gained a number of professional skills, such as communicating assertively, allowing for contrary opinions, and being resilient after rejections. In the 2014 assessment, survey assistants credited participation with improving their public-speaking skills and confidence in professional settings. These professional development skills have been found elsewhere to be important outcomes of community-engaged research with youth.20 Fourth, a deep sense of community developed among individuals engaged.in the effort. This social capital was seen as a buffer to the challenges survey assistants faced in their daily lives, including financial hardship and deaths of family members.

Challenges of Employing Youth Survey Assistants

An important challenge to youth-engaged data collection was survey assistants’ exposure to difficult environments. For example, a number of survey assistants reported feeling uncomfortable in neighborhoods with mainly White residents. In one instance, the police were called by a resident despite the survey assistants wearing branded project clothing and carrying clipboards with survey materials. Having an adult supervisor on site was particularly important at that time. The study team also observed that survey assistants faced challenges related to power dynamics with older and male respondents. The use of teams mitigated some of these challenges and survey assistants were empowered to leave respondents’ homes. Another set of challenges related to exposure to difficult conversations with respondents. Although the questions were mainly close ended, items about discrimination, health, and poverty often prompted respondents to describe personal challenges in great detail. Study team members and site supervisors noted that survey assistants struggled with listening to difficult stories and being unable help; many became interested in exploring available social services to support respondents. When considering youth-engaged data collection, it may be useful to link with educators and practitioners who work with young people to ensure that the content and survey environment are developmentally appropriate for the young people involved and that youth receive necessary support as they process difficult content. The data collection effort also faced challenges related to complex skills (e.g., refusal conversion) required during survey administration. Interestingly, challenges related to asking sensitive questions, highlighted in the literature as a barrier to youth conducting research,5,11 were not an issue for this group. A final challenge of employing youth data collectors related to their limited availability. Survey assistants had a high attendance rate, although punctuality and schedule restrictions were challenges once the school year started, which extended the timeline for data collection.

Successful Execution of Research Objectives

An important measure of success was the achievement of research objectives. The data collection effort yielded 991 surveys, of which 925 were complete. Two-thirds of the completed surveys were administered in Spanish. The response rate was 19%, with high rates of non-response (58%) and refusal (23%). Real-time process evaluation identified refusals as a challenge, and coaching was provided, but most teams were unable to improve their conversion rates. However, survey assistants were able to encourage a large percentage of respondents to complete the survey. The survey assistants successfully surveyed a population often considered “hard to reach” for research. Supervisors noted the importance of having young people who were recognized as community members as survey assistants, and attributed both higher participation and completion rates to the sense of obligation respondents felt towards young people from their community. The data collected were of high quality. Demographic estimates were similar to American Community Survey estimates for Lawrence on many key indicators, such as income and education.14 Survey assistants were able to share field knowledge to improve the study protocol. For example, challenges they identified with survey administration resulted in rear-ranged question order and increased participant incentives.

Commitment of Human and Financial Resources

The effort required commitment of significant human and financial resources, particularly the engagement of site supervisors and study team members, to execute the protocol as designed and support survey assistants as they encountered challenging research settings and subject matter. The study team’s continuous local presence (through field visits and a locally based health educator) reflects the importance of constant engagement, as echoed in other studies engaging adolescents.21 The C-PAC made a tremendous commitment, particularly because the data collection effort fit the broader philosophy of the project and partnership, but it may be difficult for engaged and participatory projects to provide this level of commitment to resource-lean projects. One solution may be to embed this type of work within educational systems or local community organizations. On the other hand, if this type of data collection is planned from the outset, two benefits may accrue. First, as noted, the costs for data collection were on the lower end of the estimates we received from external sources. Second, resources that would have otherwise been allocated to an outside research firm were directed instead into the community.

Researcher Development

Increased capacity among researchers is an important benefit of engaged research.4 Through this effort, researcher capacity to support community members in data collection activities with a “hard-to-reach” population was increased. The investments required were larger than anticipated, as were the rewards—both in terms of benefits accrued to survey assistants and to the Project IMPACT partnership. The study team also gained a deeper understanding of the challenges associated with fielding a survey of this nature with this population and interpreting the resulting data.

This paper presents key lessons learned through a serendipitous opportunity to build capacity among young people in the partner community. We thus leveraged process data rather than a prospective assessment of survey assistants’ development and perceptions. Despite these limitations, the paper contributes to a sparse literature addressing community-engaged data collection and particularly the role adolescents and young adults may play in these efforts.

CONCLUSION

Overall, youth-engaged data collection benefited the young people involved, met research objectives, and strengthened a CBPR partnership. Survey assistants gained experience with research, exposure to health careers, and professional skills. Constant engagement with supervisors and study team members plus team-based survey administration allowed the young people involved to manage challenges with survey content, survey environments, and respondents. Survey assistants also benefitted greatly from the deep investments and strong partnerships of the C-PAC. With these supports and by leveraging their position as young people from the community, survey assistants were able to collect high-quality data from a hard-to-reach population.

This effort highlights the potential to integrate youth into research activities to maximize their impact and build capacity for engaging with data, which can be tied to creating change. Survey assistants’ willingness to engage critically with issues of health inequalities and social determinants of health highlights the potentially transformative power of youth-engaged research. As a recent review of CBPR studies with youth highlighted, engaging young people in participatory research is not the norm (about 15% of projects identified as participatory actively partnered with youth), but examples of engagement across all phases of research exist.20 Youth-engaged data collection may provide a useful entry point into the research process, either as a discrete activity (as in this example) or in a project focused on and partnered with youth. Although not part of the original project plan, youth-engaged data collection had diverse benefits that enhanced a broader effort to create lasting change and address inequalities in the partner community.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to the 16 survey assistants and 3 site supervisors who drove the success of this data collection effort. This research was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (5 P50-CA148596, Viswanath, PI for Project 1). Funding support for R.H.N. and M.P.M. was provided through the National Cancer Institute to the Harvard Education Program in Cancer Prevention (3 R25-CA057711); R.H.N. also acknowledges support from the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Grant (2 K12-HD055887) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development, the Office of Research on Women’s Health, and the National Institute on Aging, administered by the University of Minnesota Deborah E. Powell Center for Women’s Health. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The evaluation was conducted in collaboration with the Project IMPACT Community Partners Advisory Committee (C-PAC), which included 1) Community partners: Niurka Aybar, BS (Northern Essex Community College), Rose Gonzalez, BS (Groundwork Lawrence), Diane Knight (Northeast Tobacco Free Community Partnership), Heather McMann, MBA (Groundwork Lawrence), Vilma Lora, BS (YWCA of Greater Lawrence/City of Lawrence Mayor’s Health Task Force), Paul Muzhuthett, MPH (Department of Public Health and City of Lawrence Board of Health; 2) Investigators: K. “Vish” Viswanath, PhD (Harvard School of Public Health/ Dana-Farber Cancer Institute), Elaine Puleo, PhD (University of Massachusetts), Glorian Sorensen, PhD, MPH (Harvard School of Public Health/Dana-Farber Cancer Institute), David Williams, PhD (Harvard School of Public Health), Ichiro Kawachi, PhD (Harvard School of Public Health), and Alan Geller, MPH, RN (Harvard School of Public Health); and 3) the Project IMPACT Study Team: Cabral Bigman, PhD (University of Illinois), Carmenza Bruff, BS (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute), Rachel McCloud, ScD (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute), Michael McCauley, PhD (Medical College of Wisconsin), Sara Minsky, MPH (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute), Yudy Muneton, LCSW (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute); Rebekah Nagler, PhD (University of Minnesota), and Shoba Ramanadhan, ScD, MPH (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute).

Contributor Information

Shoba Ramanadhan, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Rebekah H. Nagler, University of Minnesota

Michael P. McCauley, Medical College of Wisconsin

Vilma Lora, YWCA of Greater Lawrence/City of Lawrence Mayor’s Health Task Force.

Sara Minsky, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Carmenza Bruff, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Yudy F. Muneton, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

Rachel F. McCloud, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

Elaine Puleo, University of Massachusetts.

Kasisomayajula Viswanath, Harvard School of Public Health/ Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Koh HK, Graham G, Glied SA. Reducing racial and ethnic disparities: The action plan from the Department of Health and Human Services. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;10:1822–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross LF, Loup A, Nelson RM, et al. Human subjects protections in community-engaged research: A research ethics framework. J Empir Res Human Res Ethics. 2010;5(1):5–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lasker RD, Weiss ES, Miller R. Partnership synergy: A practical framework for studying and strengthening the collaborative advantage. Milbank Q. 2001;79(2):179–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, et al. Community-based participatory research: Assessing the evidence. Report/ Technology Assessment No. 99. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Prepared by RTI–University of North Carolina Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290–02–0016); 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, et al. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minkler M, Wallerstein N, eds. Community based participatory research in health. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, et al. Critical issues in developing and following CBPR principles. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, eds. Community-based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008:47–66. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cashman SB, Adeky S, Allen III AJ, et al. The power and the promise: working with communities to analyze data, interpret findings, and get to outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(8):1407–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LaBonte R, Laverack G. Capacity building in health promotion, Part 1: for whom? And for what purpose? Critical Public Health. 2001;11(2):111–28. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koh HK, Oppenheimer SC, Massin-Short SB, et al. Translating research evidence into practice to reduce health disparities: A social determinants approach. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(S1):S72–S80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delgado M. Community asset assessments by Latino youths. Child School. 1996;18(3):169–78. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Branch R, Chester A. Community-based participatory clinical research in obesity by adolescents: Pipeline for researchers of the future. Clin Transl Sci. 2009;2(5):350–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramanadhan S, Viswanath K. Engaging communities to improve health: Models, evidence, and the Participatory Knowledge Translation (PaKT) framework. In: Fisher EB, ed. Principles and Concepts of Behavioral Medicine: A Global Handbook. New York: Springer Science & Business Medial; in press. [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S. Census Bureau. U.S. Census Bureau, 2008–2012 American Community Survey. Washington (DC): U.S. Census Bureau; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Massachusetts Executive Office of Health and Human Services. Instant topics; [updated 2014; cited 2014 Mar 15]. Available from: http://www.mass.gov/eohhs/researcher/community-health/masschip/instant-topics.html [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holbrook AL, Green MC, Krosnick JA. Telephone versus face-to-face interviewing of national probability samples with long questionnaires: Comparisons of respondent satisficing and social desirability response bias. Public Opin Q. 2003;67(1):79–125. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blumberg SJ, Luke JV. Wireless substitution: Early release of estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, January—June 2013. Atlanta: National Center for Health Statistics; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minkler M, Wallerstein N, Wilson N. Improving health through community organization and community building. In: Glanz K, Rimer B, Viswanath K, eds. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice. 4th ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc. Publishers; 2008. p. 287–312. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baranowski T, Stables G. Process evaluations of the 5-a-day projects. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27(2):157–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacquez F, Vaughn LM, Wagner E. Youth as partners, participants or passive recipients: A review of children and adolescents in community-based participatory research (CBPR). Am J Community Psychol. 2013;51(1–2):176–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson N, Minkler M, Dasho S, et al. Getting to social action: The Youth Empowerment Strategies (YES!) Project. Health Promot Pract. 2008;9(4):395–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]