Abstract

Metabolic resistance to the maize-selective, HPPD-inhibiting herbicide, mesotrione, occurs via Phase I ring hydroxylation in resistant waterhemp and Palmer amaranth; however, mesotrione detoxification pathways post-Phase I are unknown. This research aims to (1) evaluate Palmer amaranth populations for mesotrione resistance via survivorship, foliar injury, and aboveground biomass, (2) determine mesotrione metabolism rates in Palmer amaranth populations during a time course, and (3) identify mesotrione metabolites including and beyond Phase I oxidation. The Palmer amaranth populations, SYNR1 and SYNR2, exhibited higher survival rates (100%), aboveground biomass (c.a. 50%), and lower injury (25–30%) following mesotrione treatment than other populations studied. These two populations also metabolized mesotrione 2-fold faster than sensitive populations, PPI1 and PPI2, and rapidly formed 4-OH-mesotrione. Additionally, SYNR1 and SYNR2 formed 5-OH-mesotrione, which is not produced in high abundance in waterhemp or naturally tolerant maize. Metabolite features derived from 4/5-OH-mesotrione and potential Phase II mesotrione-conjugates were detected and characterized by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LCMS).

Keywords: waterhemp, dioecious amaranth, mesotrione resistance, cytochrome P450 monooxygenase, oxidative metabolism, herbicide detoxification, metabolomics

1. Introduction

Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri S. Watson) is one of the most troublesome weeds infesting cropping systems across the United States due in part to the extent of damage it inflicts on crop yield and quality1 and challenges to control its distribution across agricultural fields. Reduction in quality and yields due to Palmer amaranth infestation were reported for cotton (Gossypium spp.),2 soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.),3,4 maize (Zea mays L. Moench),5 and sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.),6 among others. Palmer amaranth is a dioecious annual dicot7 with a C4 photosynthetic pathway.8 Palmer amaranth is adapted to high temperatures and low rainfall and can germinate rapidly to complete its life cycle in response to available moisture;8 it is also a prolific seed producer, with a single female plant capable of producing up to 600,000 seeds9 that stay dormant in the seed bank for more than 4 years.10 Seasonal and long-term control of Palmer amaranth is difficult because it has a season-long emergence pattern, vigorous seedling growth, the ability to rapidly replenish the soil seed bank, and a tendency to evolve resistance to herbicides.9,11,12

From its native origins in the Sonoran Desert, Palmer amaranth populations have spread throughout different areas of the United States,13 parts of South America,6 and recently in South Africa,14 including multiple-herbicide-resistant (MHR) populations,14 either due to trade of contaminated farm equipment, crop seeds, or other raw food materials. To date, Palmer amaranth has evolved resistance to nine herbicide sites-of-action, including the 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase (HPPD)-inhibiting herbicides, and numerous MHR Palmer amaranth populations have contributed to its success as an invasive weed.1,6

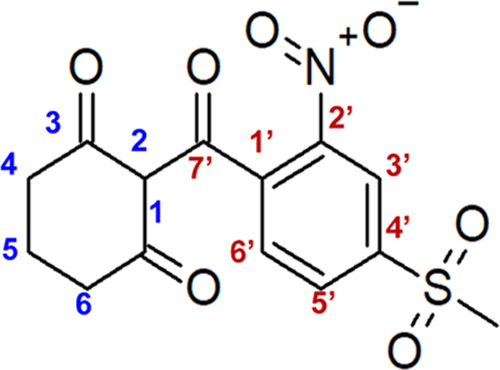

HPPD-inhibiting herbicides are competitive inhibitors of the HPPD enzyme, which catalyzes the transformation of 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate to homogentisic acid (HGA), a key step in the tyrosine catabolic pathway common to all aerobic organisms.15 In plants, HGA is a key intermediate in the biosynthesis of tocopherols and plastoquinones, which are essential compounds for photosynthesis.16,17 Inhibition of the HPPD enzyme results in bleaching and necrosis of meristematic tissues and eventually death of sensitive plants.18,19 HPPD-inhibiting herbicides are widely used globally.20 A 2-benzoylethen-1-ol substructure is the minimum requirement for a potent HPPD inhibitor,21,22 with its ortho-substituent on the aryl ring being an essential requirement for herbicidal activity.22 Mesotrione (2-[4-(methylsulfonyl)-2-nitrobenzoyl]cyclohexane-1,3-dione) is a postemergence HPPD-inhibiting herbicide for selective control of broadleaf weeds in maize.23,24 Mesotrione is a triketone HPPD-inhibiting herbicide, structurally characterized by a combination of two rings: a nitro- and methylsulfonyl-substituted benzoyl ring and a β-diketo-substituted cyclohexane ring. Mesotrione structurally resembles leptospermone, the natural phytotoxin from which triketone herbicides originate (Figure 1).20,25

Figure 1.

Structure of the 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase-inhibiting herbicide, mesotrione, [2-(4-(methylsulfonyl)-2-nitrobenzoyl)cyclohexane-1,3-dione].

Herbicide metabolism is a nontarget-site-based resistance (NTSR) mechanism in weeds and generally proceeds in three phases: transformation (Phase I), conjugation (Phase II), and compartmentation (Phase III).26 These phases sequentially modify herbicides into nonphytotoxic forms via the action of various detoxification enzymes.27 Metabolic resistance via Phase I ring hydroxylation of parent mesotrione is the main reported mechanism for mesotrione among weedy Amaranthus species and has largely been associated with cytochrome P450-dependent monooxygenases (P450s) and other potential detoxification enzymes in other dicots.28 P450s form a large family of enzymes essential for the metabolism of toxins of foreign origin (xenobiotics), such as herbicides.29,30 In 2009, a population of waterhemp (A. tuberculatus Moq. J.D. Sauer) was discovered in Illinois (MCR population, for McLean County-Resistant) and later identified as multiple resistant to mesotrione, atrazine, and other herbicides.18,31 Compared to a sensitive population, the MCR population (also called SIR for Stanford, Illinois-Resistant) rapidly metabolized mesotrione to a C4 dione-ring hydroxylated metabolite, 4-hydroxy-mesotrione (4-OH-mesotrione),32 a mesotrione metabolite previously reported in naturally tolerant maize.33 A waterhemp population from Nebraska (NEB) also exhibited rapid mesotrione metabolism and produced higher levels of 4-OH-mesotrione over time compared to a sensitive population.34 Rapid metabolism of mesotrione was also identified in three Palmer amaranth populations from Kansas and Nebraska.35 These past studies established that mesotrione metabolism via rapid formation of Phase I metabolites is the primary mechanism of mesotrione resistance in weedy Amaranthus, although possible target-site-based mechanisms have also been implicated.35 However, research has not been reported on the metabolic fate of mesotrione beyond Phase I reactions in plants.

Our current research was built upon initial greenhouse studies including 22 populations of Palmer amaranth collected from the U.S. (Table S1). Of these populations, four were completely controlled by the field-use rate of mesotrione (105 g a.i. ha–1), hence were classified as mesotrione-sensitive,35 six were resistant, and the rest displayed variable responses to mesotrione treatment. In the current study, eight of these 22 Palmer amaranth populations were analyzed in the greenhouse and laboratory to investigate possible metabolic resistance mechanisms to mesotrione. Specific objectives of this study are to (i) screen Palmer amaranth populations for resistance to 105 g a.i. ha–1 mesotrione via visual injury and biomass measurements; (ii) investigate rates of mesotrione metabolism in select Palmer amaranth populations using thin-layer chromatography (TLC); and (iii) detect and identify mesotrione metabolites in these populations using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LCMS)-based untargeted metabolomics. Finally, we propose a detoxification pathway for mesotrione in MHR Palmer amaranth.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Radiolabeled [URL-14C]-mesotrione (1383 MBq mmol–1), nonlabeled analytical-grade mesotrione (98% pure), 4-OH-mesotrione (99.8% pure), 5-OH-mesotrione (98.2% pure), AMBA (2-amino-4-methylsulfonylbenzoic acid; 99% pure), and MNBA (4-methylsulfonyl-2-nitrobenzoic acid; 99% pure) were supplied by Syngenta Crop Protection (Greensboro, NC). All other analytical-grade chemicals were purchased through Fisher Scientific (Thermo Fisher, Hanover Park, IL) or Sigma Chemical (Millipore Sigma, St. Louis, MO).

2.2. Plant Materials

Of the 22 populations initially screened for responses to 105 g a.i. ha–1 mesotrione, eight Palmer amaranth populations that exhibited moderate-to-high resistance (greater than 10% survivorship) levels, as well as two sensitive populations with ample viable seeds, were chosen from this original set (Table S1). Populations identified as resistant but lacking viable seeds were not further analyzed. Populations were provided with unique codes or PS numbers generated by Syngenta at Jealott’s Hill International Research Center, United Kingdom. Most Palmer amaranth populations in this study were obtained from growers’ fields where a herbicide control failure had been observed. The exception to this is the PS-8398 population, henceforth called PPI1, which is a standard sensitive population typically used by Syngenta researchers. SIR and ACR populations were selected as known mesotrione-resistant and sensitive waterhemp, respectively, for comparison with Palmer amaranth populations. The SIR population is a subpopulation of the original MCR population described in previous research,18,36 and is resistant to multiple herbicide groups and chemical families.18,36−41 The ACR population originated from Adams County, Illinois, and is sensitive to HPPD-inhibiting herbicides but resistant to atrazine.18,36 The majority of the Palmer amaranth populations were sampled from growers’ fields in the U.S., whereas PS-12384 originated from South Africa (Table 1).

Table 1. Mean Percent Survival to Foliar-Applied Mesotrione (14 Days after Treatment) of Several Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) and Waterhemp (A. tuberculatus) Populations.

| species | population | origin | survivala (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amaranthus tuberculatus | ACR | Illinois, US | 0 |

| Amaranthus tuberculatus | SIR | Illinois, US | 100 |

| Amaranthus palmeri | PS-11907 | Louisiana, US | 0 |

| Amaranthus palmeri | PS-8398 | Unknown, US | 0 |

| Amaranthus palmeri | PS-11429 | Arkansas, US | 60 |

| Amaranthus palmeri | PS-12384 | South Africa | 60 |

| Amaranthus palmeri | PS-14577 | Kansas, US | 75 |

| Amaranthus palmeri | PS-14612 | Kansas, US | 75 |

| Amaranthus palmeri | PS-14617 | Kansas, US | 100 |

| Amaranthus palmeri | PS-9857 | Kansas, US | 100 |

All plants were treated with mesotrione at the labeled rate of 105 g a.i. ha–1 plus crop oil concentrate (1% v/v) and liquid ammonium sulfate (2.5% v/v) as adjuvants.

2.3. Seed Preparation and Growing Conditions

Dry seeds were germinated in 12 cm × 12 cm trays using a BM1 optimal porosity soil mix (Berger, Canada) in a growth chamber (Controlled Environments Limited, Winnipeg, Canada) set at 28/22 °C day/night temperature with a 16-h photoperiod, transplanted into 80 cm3 pots in the greenhouse upon emergence, then transplanted into 950 cm3 pots containing a 3:1:1:1 mixture of potting mix:soil:peat:sand with 5 g of slow-release fertilizer (Osmocote 13-13-13, Scotts, 14111 Scottslawn Road, Marysville, OH 43041). Waterhemp and Palmer amaranth populations were grown under greenhouse conditions with a 28/22 °C day/night temperature and supplemented with mercury halide lamps to provide 800 μmol m–2 s–1 photon flux at the soil surface and a 16-h day/8-h night photoperiod as described previously.39,41

2.4. Whole Plant Resistance Levels and Assessment of Foliar Injury

Ten plants of each population (each plant represents one replication) of Palmer amaranth and waterhemp populations were grown to 5–7 cm in height (4–6 true leaves) and treated with mesotrione (Callisto herbicide, Syngenta Crop Protection, Greensboro, NC) at a rate of 105 g a.i. ha–1 with 1% (v/v) crop oil concentrate (COC) (Herbimax, Loveland Products, Loveland, CO 80538) and 2.5% (v/v) liquid ammonium sulfate (AMS) (N-Pak, Winfield United, Shoreview, MN 55126) as adjuvants. Ten control plants from each population were treated with adjuvants only: 1% (v/v) COC and 2.5% (v/v) AMS. Mesotrione was applied using a research-grade cabinet sprayer (Generation III Research Sprayer, Devries Manufacturing, Hollandale, MN) with a single 80015EVS nozzle (Teejet Technologies, Wheaton, IL) calibrated for 187 L ha–1 at 275 kPa. After treatment, plants were returned to the greenhouse and arranged in a completely randomized design for the duration of the experiment. Plant injury was assessed by visual inspection every 7 days for 2 weeks relative to an untreated plant for each respective population. Visual assessments of plant injury were recorded on a scale of 0–100%, where 0% represents no injury and 100% represents plant death. The injury was assessed based on the amount of chlorotic and necrotic leaf tissue as well as height differences. At 14 days after treatment (DAT) with mesotrione, surviving plants were considered resistant. Plants completely controlled by mesotrione 14 DAT were considered sensitive. The plant height was measured prior to spraying at seven DAT and before harvest at 14 DAT. At harvest, plants were cut at the soil line, bagged, and placed in an oven at 65 °C for drying. After 7 days of drying, weights were recorded and compared to their respective controls. The experiment was performed twice, and data were pooled for further statistical analysis as described below.

2.5. [14C]-Mesotrione Metabolism in Excised Waterhemp and Palmer amaranth Leaves

The time-course experiment is adapted from the excised leaf assay described previously for waterhemp41 with modifications below to adjust for the larger leaf blade of Palmer amaranth compared to waterhemp and using two leaves per plant instead of one to increase the amount of herbicide uptake for downstream analyses. Two Palmer amaranth populations that displayed the highest frequency of survivors to mesotrione in the greenhouse (SYNR1 and SYNR2) and two of the most sensitive populations (PPI1 and PPI2) were used in this assay. Maize seedlings were included in the assay as a positive control for metabolizing mesotrione to 4-OH-mesotrione.32 Twenty-four hours preceding treatment, greenhouse-grown plants were transferred to a growth chamber set at previously described conditions. The following day, the third and fourth youngest leaves from waterhemp or Palmer amaranth plants from each population were individually excised under water and placed in 200 μL of 0.1 M Tris-Cl (pH 6.0) in a 5 mL Eppendorf tube instead of a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube used elsewhere.42 After 1 h, seedlings were transferred to 200 μL of 150 μM [14C]-mesotrione (5 MBq/mmol) in 0.1 M Tris-Cl (pH 6.0). After 2 additional hours to allow uptake to occur, samples were rinsed twice with deionized water, and fresh weights were recorded, followed by freezing in liquid nitrogen and storing at −20 °C until further processing.

Plant samples for additional time points (>2 h) were rinsed with 0.1 M Tris-Cl (pH 6.0), then transferred to a new 5 mL tube containing 1.0 mL of one-quarter-strength Murashige and Skoog basal salt mixture. At their respective time points (4 and 12 h after treatment (HAT)), plants were removed, and fresh weights were recorded and stored at −20 °C. Excised leaf assays consisted of three biological replications per time point. Following incubation, frozen tissue samples (approximately 0.2 g) were ground in liquid nitrogen with a metal spatula, and total radioactivity was extracted in 1 mL of 90% (v/v) methanol for 16 h at 10 °C. After the first extraction and centrifugation at 12000 × g, the supernatant was removed, and the remaining plant material was extracted in an additional 1 mL of 95% (v/v) methanol for 1 h. Following centrifugation, the pellet was discarded, and the supernatant was removed and combined with the initial supernatant, yielding a total volume of 2 mL. The extracts were dried under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas and then reconstituted in 0.2 mL of 90% (v/v) methanol. After solvent addition, each sample was vortexed and centrifuged at 12000 × g for 5 min prior to liquid scintillation spectrometry of total radioactivity remaining in the leaf extracts. Four biological replicates were combined preceding analysis to form one technical replicate per time point per population. Samples were stored at −20 °C and then placed at room temperature (25 °C) for 2 h prior to TLC analysis.

2.6. Thin-Layer Chromatography of [14C]-Mesotrione Metabolites in Excised Waterhemp and Palmer amaranth Leaves

Thin-layer chromatography was carried out with methanolic extracts from excised leaf tissues of Palmer amaranth, waterhemp, and maize. Aliquots of leaf extract containing 66 Bq (4000 dpm) were spotted on the preadsorbent zone of a channeled (20 × 20 cm2) 250 μm silica TLC plate (Whatman Silica Gel 150A; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Marlborough, MA) along with 66 Bq (4000 dpm) of [14C]-mesotrione standard. Plates were developed once with a solvent system containing chloroform/methanol/formic acid/water (70:30:4:1 (v/v)). Plates were removed from the chamber after the solvent front had migrated to the top of the plate (20 cm). Plates were then air-dried, wrapped in a plastic film, and stored in a cassette facing a 20 × 40 cm2 phosphorimage plate (BAS-IIIs; Fuji Film Holdings America Corporation, Valhalla, NY) for 24 h. Storage phosphor plates were imaged using a GE Typhoon phosphorimage scanner (Typhoon 9400; GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and ImageQuant software (ImageQuant TL version 8.1; GE Healthcare Life Sciences) at the University of Illinois Proteomics Facility.

2.7. Untargeted Metabolomics of Excised Palmer amaranth and Waterhemp Leaf Extracts via LCMS

Untargeted metabolomics of extracts from excised leaves treated with nonlabeled, analytical-grade mesotrione was carried out according to protocols in a previous study using nonlabeled syncarpic acid-3 (SA3) in waterhemp40 with modifications for Palmer amaranth. These modifications were incorporated in the excised leaf assay and include the following: (i) use of larger plastic tubes (5 mL instead of 1.5 mL) to accommodate larger leaves of Palmer amaranth; and (ii) use of a lower herbicide concentration (0.15 mM instead of 0.3 mM) to match the amount used for TLC analysis. The third and fourth youngest leaves from each plant were collected in a container with deionized water, and leaf petioles were cut again (∼3 mm) with a razor blade under water and then placed in 5 mL tubes (VWR Scientific, Batavia, IL) containing 200 μL of 0.1 M Tris–HCl (pH 6.0) to equilibrate for 1 h. Leaves were then transferred to new 5 mL tubes containing mesotrione incubation solution (0.15 mM mesotrione in 0.1 M Tris–HCl (pH 6.0)). After 2 h of incubation in mesotrione solution, leaves were either harvested or washed with 0.1 M Tris–HCl (pH 6.0) and placed in a 5 mL tube containing 500 μL of one-quarter-strength Murashige and Skoog’s basal salts liquid medium (MP Biomedicals, LLC). Leaves were harvested at three time points (2, 6, and 12 HAT) for the first experiment and at five time points (2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 HAT) following transfer to mesotrione solution for the second experiment, then briefly rinsed in deionized water and dried with tissue paper. Fresh weights of the leaves were recorded, and the leaves were placed in 2 mL screw-capped tubes and then immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Frozen leaves were stored at −80 °C until further analysis. Four biological replicates were analyzed per population per time point.

Total plant metabolites were extracted from frozen tissue once with 1 mL of 80% methanol (containing 0.1% formic acid) overnight at 10 °C, then once with 0.5 mL of 95% methanol for 2 h. The internal standard CPA (4-chloro-dl-phenylalanine; 25 μg mL–1 in 1 N HCl) was spiked into the tissue prior to extraction. Experimental blank extracts (without herbicide) were prepared identically. Combined extracts were centrifuged, concentrated under nitrogen gas, and then reconstituted in 0.2 mL of water: acetonitrile (1:1, v/v) containing 0.1% formic acid and stored in a polyspring glass insert (Thermo Scientific) sealed in a 2 mL HPLC glass vial (Fisher Scientific). Samples were randomized and analyzed using a Dionex Ultimate 3000 series HPLC system (Thermo Scientific, Germering, Germany) coupled to a Q Exactive Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Bremen, Germany) as described previously.41 The chromatographic analysis included pooled quality control (QC) samples injected at the beginning of the analysis to equilibrate the analytical platform and after every 10 test samples to evaluate the stability of the experimental procedure.43−46 QC samples were prepared by combining 20 μL of each extract. Synthetic standards of mesotrione and its known metabolites in soil and other plants (4-OH-mesotrione, 5-OH-mesotrione, AMBA, and MNBA) were analyzed after the test samples. Raw data files obtained in full-MS mode (samples, procedural blank, and QC) and data obtained in full-MS followed by data-dependent MS2 were processed by MS-DIAL software v.4.9047 separately for positive and negative electrospray ionization modes (ESI(+) and ESI(−)) for initial data processing, including peak detection, peak alignment, peak integration, deconvolution, and identification with details described previously.41

2.8. Statistical Analysis

2.8.1. Foliar Response to Mesotrione in the Greenhouse

Statistical analyses of phenotypic data (visual ratings of injury and aboveground dry biomass) measured following treatment of mesotrione (105 g a.i. ha–1) were carried out on 20 plants of each weedy Amaranthus population across two experimental runs using the generalized linear mixed model from the R package “lme” in R (version 4.2.1) and RStudio (Version 2022.07.1). The mixed model included population (popn) and experiment (exp) as fixed effects and replicate (rep) nested within exp as a random effect. Due to a lack of interaction between popn and exp (p-value >0.05), data from two experiments were combined. Data was transformed via Tukey’s ladder of powers transformation using the “TransformTukey” function of the “rcompanion” package to meet assumptions of normality, tested via the Shapiro-Wilk test and examination of Q–Q plots. Following a significant result from one-way ANOVA of transformed phenotypic data between populations (p-value <0.0001), multiple pairwise comparisons of mean phenotype among populations were carried out using Tukey’s HSD (Tukey Honest Significant Difference) (p < 0.05) using the “CLD” function from the “emmeans” package.

2.8.2. Calculation of DT50 Values

Degradation rates of the mesotrione parent compound identified in the LCMS experiment were calculated via a log–logistic regression model in the drc package in R (version 4.2.1) and RStudio (Version 2022.07.1) using a three-parameter logistic regression model48 with the following equation:

| 1 |

where d is the upper limit, b is the slope of the curve, and e is the time point where a 50% reduction in amounts of parent mesotrione was determined.

2.8.3. Preprocessing and Multivariate Statistical Analysis of Untargeted Metabolomics Data

The raw LCMS data files were converted to the .mzML format using MSConvert software.49 Initial processing of metabolomics data was carried out on ESI(+) and ESI(−) data as previously described41 using MS-Dial software (version 4.90).47 This step includes peak detection, peak alignment, peak deconvolution, peak normalization based on the amount of internal standard remaining in the sample and the relative abundance of metabolites across 10 QC samples, and peak identification using the MassBank of North America (MoNA) database (https://mona.fiehnlab.ucdavis.edu/).

Preprocessed data were then imported to MetaboAnalyst 5.0 (https://www.metaboanalyst.ca/), an online platform that provides further statistical analysis and visualization support.50,51 Features with the following parameters were removed prior to analysis: signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) less than 10, without MS/MS data, and not detected in at least 60% of QC samples. Prior to further statistical analyses, metabolite features were log-transformed, Pareto scaled, and then analyzed via principal components analysis (PCA) to visualize the overall metabolite profiles in the four Palmer amaranth populations. Data scaling adjusts each variable/feature by a scaling factor computed based on the dispersion of the variable. Following PCA, a partial least-squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA)52 was performed to capture among-group variation and identify mesotrione metabolite features that most differ between resistant and sensitive Palmer amaranth and untreated control plants used in this study. Ward hierarchical clustering and generation of a heatmap dendrogram with Euclidean distances were carried out using normalized and scaled metabolite features. A clustered heatmap with Pearson’s r correlation values between the abundances of mesotrione and its identified metabolite features was created in R version 4.3.1 and RStudio 2023.06.1 using the “cor” function within the “ggplot” package. Tentative annotation of metabolite features of mesotrione was performed in silico using BioTransformer 3.0 software (https://biotransformer.ca)53 and SIRIUS v5.8.3.54

3. Results and Discussion

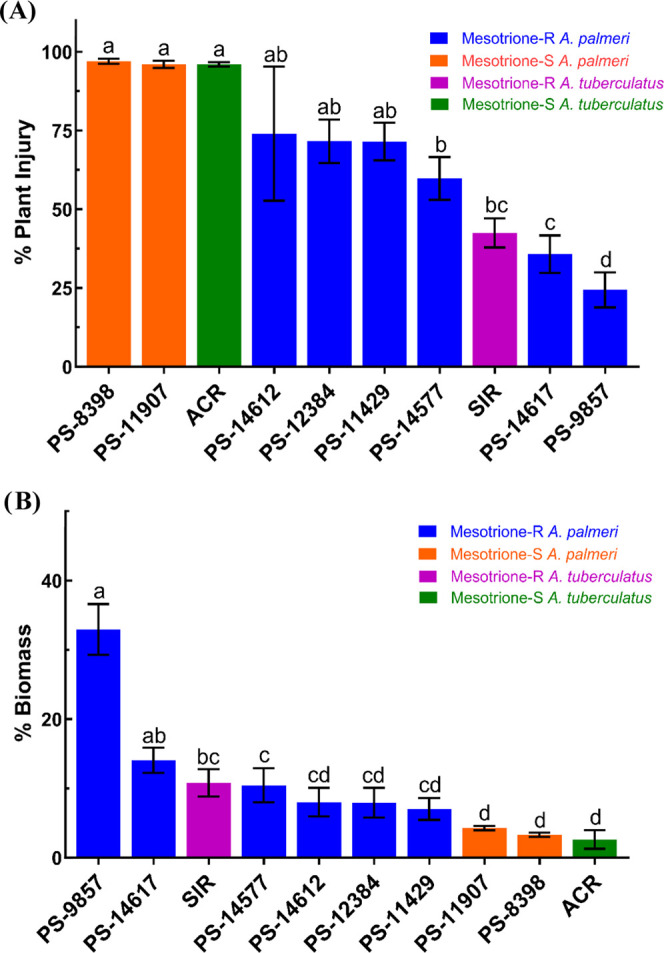

3.1. Screening for Whole Plant Resistance to Mesotrione

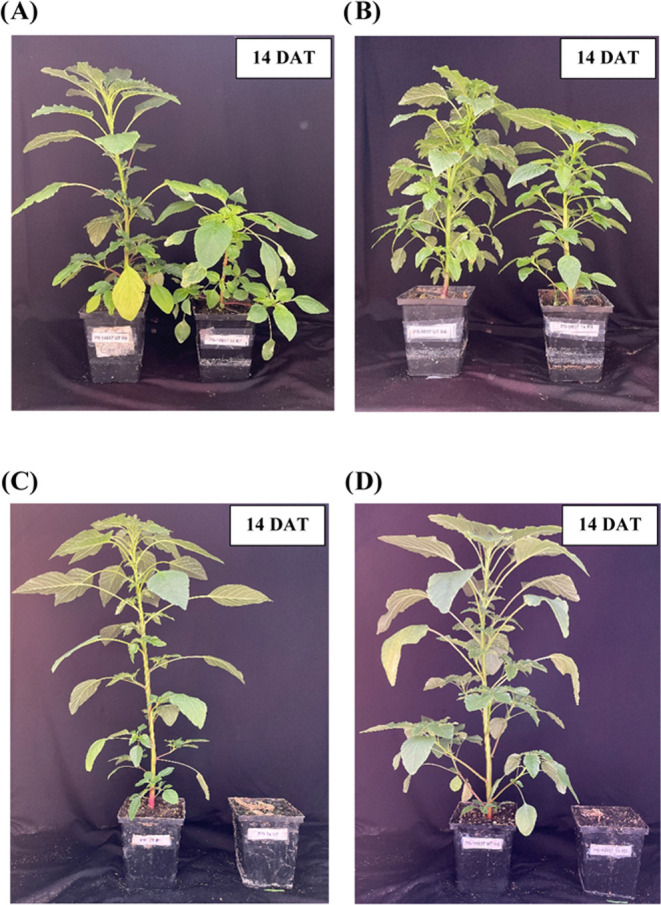

Complete control of ACR plants was achieved following mesotrione treatment, while all SIR plants survived (Table 1 and Figure S1). Relative to ACR, SIR, and other Palmer amaranth populations, PS-9857 exhibited the highest frequency of survivors to mesotrione (Table 1) and the lowest average visual injury rating of 24% (Figure 2A) at 14 DAT. PS-14617 also showed a high level of resistance to mesotrione, exhibiting 100% survival and an average injury rating of 36% (Table 1 and Figure 2A). PS-8398 and PS-11907, on the other hand, were completely controlled by mesotrione at 14 DAT and exhibited 0% survival (Table 1). These populations also displayed 100% plant injury at 14 DAT, equivalent to mesotrione-sensitive waterhemp, ACR (Figure 2A). Aboveground biomass of PS-9857 was highest among Palmer amaranth and waterhemp populations screened, followed by PS-14617 and SIR (Figure 2B). ACR, PS-8398, and PS-11907 had the lowest recorded biomass, confirming sensitivity to mesotrione at 14 DAT (Figure 2B). From this greenhouse study, four Palmer amaranth populations were selected for further biochemical analysis in the laboratory due to their significantly different responses to mesotrione (Figures 2 and 3). These populations were PS-14617, PS-9857, PS-8398, and PS-11907, which were renamed SYNR1, SYNR2, PPI1, and PPI2, respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Visual assessments of plant injury (A) and aboveground dry biomass (B) at 14 DAT of 105 g a.i. ha–1 mesotrione plus 1% (v/v) COC and 2.5% (v/v) AMS in eight Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) and two waterhemp (A. tuberculatus) populations. Error bars correspond to the standard error of the mean for plant injury and dry biomass across 20 replicates. The difference in letters corresponding to each population denotes significant differences at p ≤ 0.05. p-value adjustment was performed using Tukey’s method for comparing a family of 10 estimates.

Figure 3.

Representative plants of Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) populations: PS-14617 (A), PS-9857 (B), PS-8398 (C), and PS-11907 (D) after treatment with 105 g a.i. ha–1 mesotrione plus 1% (v/v) COC and 2.5% (v/v) AMS at 14 DAT and compared with their respective untreated controls (adjuvants only). These populations are henceforth called SYNR1, SYNR2, PPI1, and PPI2, respectively.

3.2. TLC Analysis of [14C]-Mesotrione Metabolites in Excised Leaves

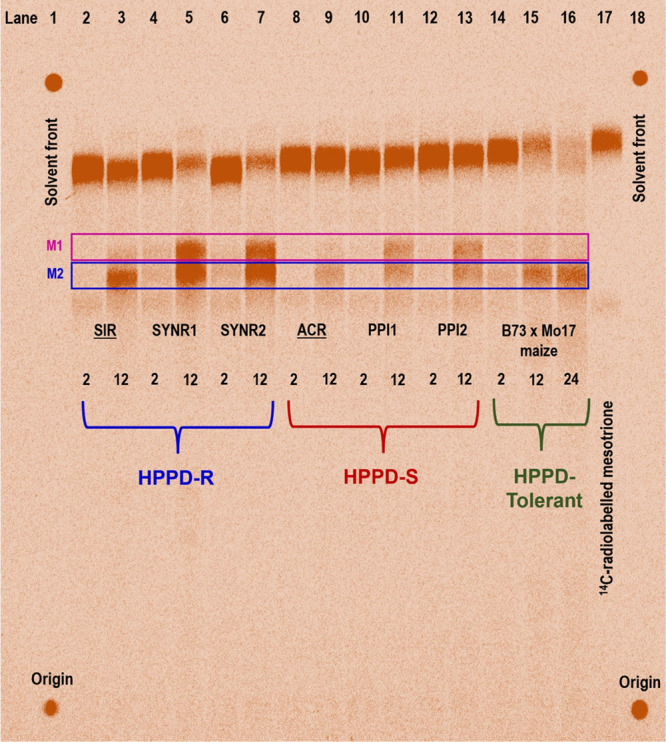

Detection and characterization of mesotrione metabolites in weeds have been largely conducted via HPLC analysis of radiolabeled mesotrione, where distinct metabolite peaks are detected via radiochromatograms.32,34,35,55 In this study, qualitative TLC was performed to compare the relative abundances of parent [14C]-mesotrione and metabolites among waterhemp (SIR and ACR), Palmer amaranth (SYNR1, SYNR2, PPI1, and PPI2), and maize during a time-course study (Figure 4). Visual inspection of the compound in each lane that cochromatographed with parent mesotrione demonstrated that resistant waterhemp SIR (lanes 2–3) metabolized more mesotrione than the sensitive population, ACR (lanes 8–9), at 12 HAT (Figure 4). The Palmer amaranth populations, SYNR1 and SYNR2, metabolized more mesotrione than SIR waterhemp at 12 HAT and produced a slightly more nonpolar band (M1) relative to presumed 4-OH-mesotrione (M2) at 12 HAT (Figure 4; lanes 5 and 7). In addition, sensitive populations PPI1 and PPI2 metabolized mesotrione slower than SIR, SYNR1, and SYNR2, yet faster than ACR (Figure 4; lanes 9, 12, and 13). Metabolites formed in sensitive and MHR Palmer amaranth populations were consistent, indicating mesotrione metabolism between MHR and sensitive populations is quantitatively variable.56

Figure 4.

Silica gel thin-layer chromatography of mesotrione metabolites in four Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) and two waterhemp (A. tuberculatus) (underlined) at 2 and 12 h after treatment (HAT) with [14C]-mesotrione, as well as maize at 2, 8, and 24 HAT. Each lane corresponds to a sample: (1, 18) Origin of spotting and solvent front; (2) SIR, 2 h; (3) SIR, 12 h; (4) SYNR1, 2 h; (5) SYNR1, 12 h; (6) SYNR2, 2 h; (7) SYNR2, 12 h; (8) ACR, 2 h; (9) ACR, 12 h; (10) PPI1, 2 h; (11) PPI1, 12 h; (12) PPI2, 2 h; (13) PPI2, 12 h; (14) Maize, 2 h; (15) Maize, 8 h; (16) Maize, 24 h; and (17) [14C]-mesotrione standard in 0.1 M Tris-Cl (pH 6.0). Maize extracts were obtained from a separate assay and used as a positive control for in vivo production of the 4-hydroxy-mesotrione metabolite (M2, blue box). M1, putative 5-hydroxy-mesotrione metabolite (pink box).

These findings led us to hypothesize that Palmer amaranth possesses a different pathway of mesotrione detoxification compared to waterhemp and possibly different from maize as well. Furthermore, results comparing the formation of 4-OH-mesotrione in resistant and sensitive Palmer amaranth in the presence or absence of malathion, a plant P450 inhibitor,29,30 revealed possible mesotrione detoxification by P450s (Figure S2). Although metabolite identification cannot be concluded from these data, we hypothesized that the most prominent metabolites in Palmer amaranth correspond to Phase I hydroxylated forms of mesotrione since band intensities are reduced significantly with malathion treatment (Figure S2). Since TLC is a qualitative analysis and [14C]-mesotrione metabolites were not available, detection and identification of mesotrione metabolites required more robust chromatographic separation and detection techniques described below.

3.3. Untargeted Metabolomics of Unlabeled Mesotrione Metabolites in Palmer amaranth and Waterhemp Excised Leaves

Previous mesotrione metabolism studies in weeds mainly focused on initial metabolites formed (≤24 HAT), which may not have detected other types of detoxification mechanisms occurring beyond Phase I 4/5-hydroxylation of the dione ring.32,34,35,55 More recently, LCMS-based analysis of mesotrione metabolism in transgenic soybean with ectopic expression of rice HIS1 reported several metabolites, including 4-OH- and 5-OH-mesotrione; however, their experimental mass spectral fragment ions were not presented.57 This previous study on mesotrione metabolism in transgenic soybean quantified 5-OH-mesotrione in greater abundance compared to 4-OH-mesotrione, which was only detected in control plants.57

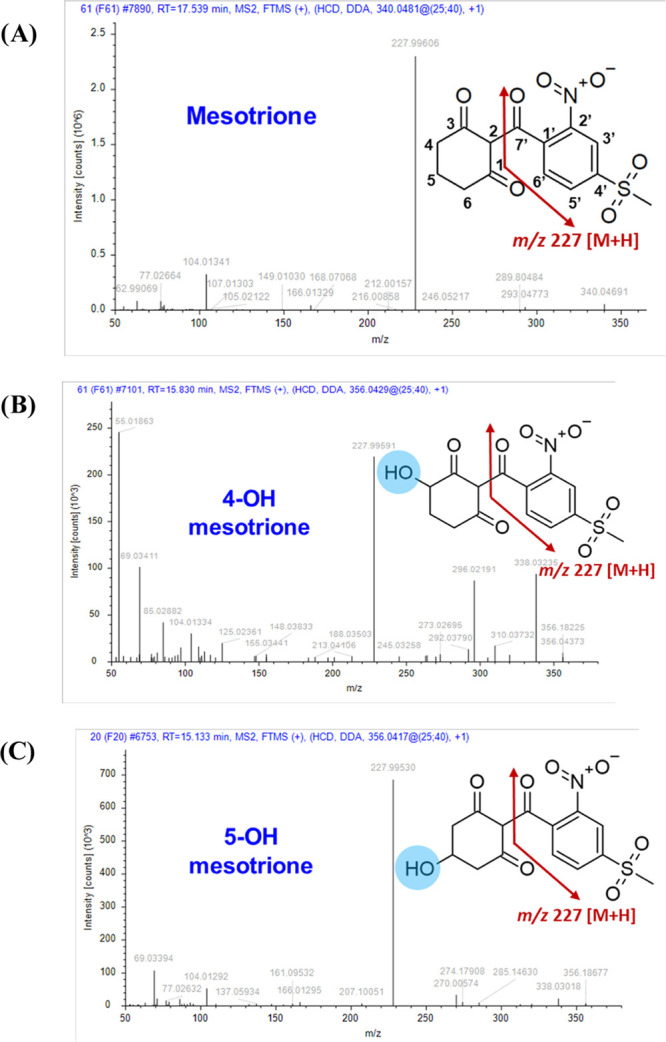

Mesotrione identified in plant extracts had a retention time of approximately 17.4 min and was detected in both ESI(+) and ESI(−) (Table 2). In the ESI(+), mesotrione has the precursor ion m/z 340 [M + H] and major MS2 ions m/z 227 [M + H], m/z 166 [M + H] and m/z 104 [M + H]. In the ESI(−), mesotrione had the precursor ion m/z 338 [M – H] and fragment MS2 ions m/z 291 [M – H], m/z 215 [M – H], m/z 249 [M – H], m/z 107 [M – H], 216 [M – H], and m/z 227 [M – H]. The ion m/z 291 corresponds to a major ion reported in a previous LCMS-based analysis of mesotrione.58 Given these distinct MS2 fragment ions and the hypothesized differential metabolism of mesotrione in Palmer amaranth and waterhemp, the detection of metabolites via LCMS and evaluation of relative metabolite abundance in each population were conducted.

Table 2. Mass Spectral Information of Mesotrione and its Metabolites Identified in Leaf Extracts of Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) via Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry.

| experimental m/z [M – H]− |

experimental m/z [M + H]+ |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | mean RT (min)a | elemental composition | theoretical mass (exact, molecular)b | precursor ion | fragment ionsc | precursor ion | fragment ions+c |

| mesotrione | 17.432 | C14H13NO7S | 339.0413, 339.3205 | 338.0338 | 291.0341 | 340.0479 | 227.9962 |

| 215.0349 | 104.0136 | ||||||

| 249.0216 | 77.0263 | ||||||

| 107.7573 | 62.9908 | ||||||

| 216.0405 | 78.9855 | ||||||

| 227.0321 | 340.0498 | ||||||

| 4-hydroxy-mesotrione | 16.326 | C14H13NO8S | 355.0362, 355.3199 | 354.0295 | 289.0204 | 356.0432 | 55.0187 |

| 307.0306 | 227.9958 | ||||||

| 213.0187 | 338.0344 | ||||||

| 171.0111 | 69.0342 | ||||||

| 92.1348 | 296.0213 | ||||||

| 225.0566 | 120.0810 | ||||||

| 5-hydroxy-mesotrione | 15.357 | C14H13NO8S | 355.0362, 355.3199 | 354.0295 | 289.0147 | 356.0417 | 227.9969 |

| 307.0245 | 69.0344 | ||||||

| 213.0177 | 104.0139 | ||||||

| 171.0107 | 338.0304 | ||||||

| 225.0520 | 86.0969 | ||||||

| 107.7615 | 270.0044 | ||||||

| MNBA | 16.799 | C8H7NO6S | 244.9994, 245.2093 | 242.0173 | 242.1757 | 244.1911 | 208.0433 |

| 225.1488 | 227.2011 | ||||||

| 181.1581 | 244.0636 | ||||||

| 107.7425 | 161.0467 | ||||||

| 155.1524 | 180.1746 | ||||||

| 63.9507 | 81.0702 | ||||||

| AMBA | 13.784 | C8H9NO4S | 215.0252, 215.2264 | 214.0173 | 170.0260 | 216.1321 | 198.0214 |

| 155.0022 | 136.0394 | ||||||

| 214.0154 | 107.0365 | ||||||

| 78.9842 | 135.0321 | ||||||

| 106.0645 | 108.0448 | ||||||

| 63.9608 | 216.0322 | ||||||

Mean retention time (RT) in minutes of metabolite features detected via liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LCMS).

Unit expressed in Daltons.

Top six fragment ions (high-to-low intensity) detected via LCMS. Bold values are common to mesotrione and metabolite features.

3.3.1. Identification and Quantitation of 4-OH- and 5-OH Mesotrione in Waterhemp and Palmer amaranth Excised Leaves

Following results of the TLC study indicating a different metabolic route of mesotrione in Palmer amaranth relative to waterhemp and tolerant maize, as well as the presence of two putative hydroxy-mesotrione metabolite bands in Palmer amaranth (Figure 4), identification of these metabolites was necessary. Hydroxylation of parent herbicide is the most common Phase I reaction in xenobiotic detoxification26,27 that is typically followed by conjugation to glucose or reduced glutathione in Phase II reactions. Phase I reactions are largely enzymatically driven and primarily associated with P450s.26 A major metabolite peak, presumed as 4-OH-mesotrione, was previously identified as a marker for mesotrione resistance in MHR waterhemp.32,34

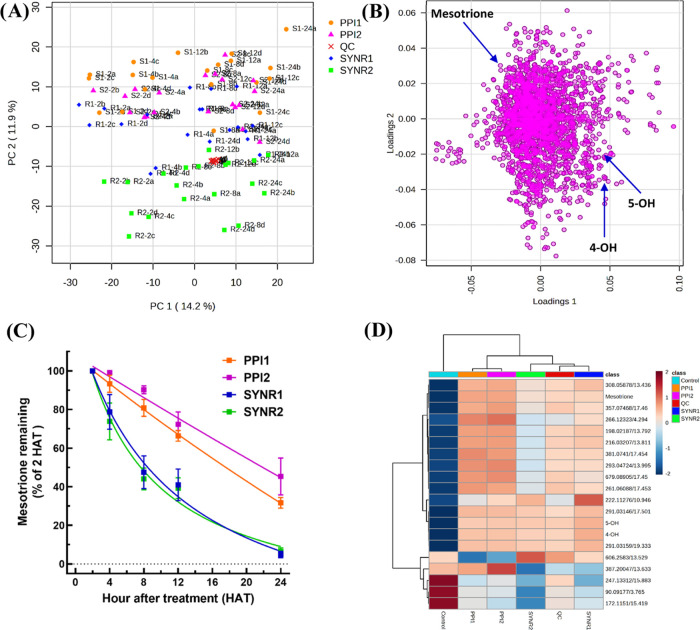

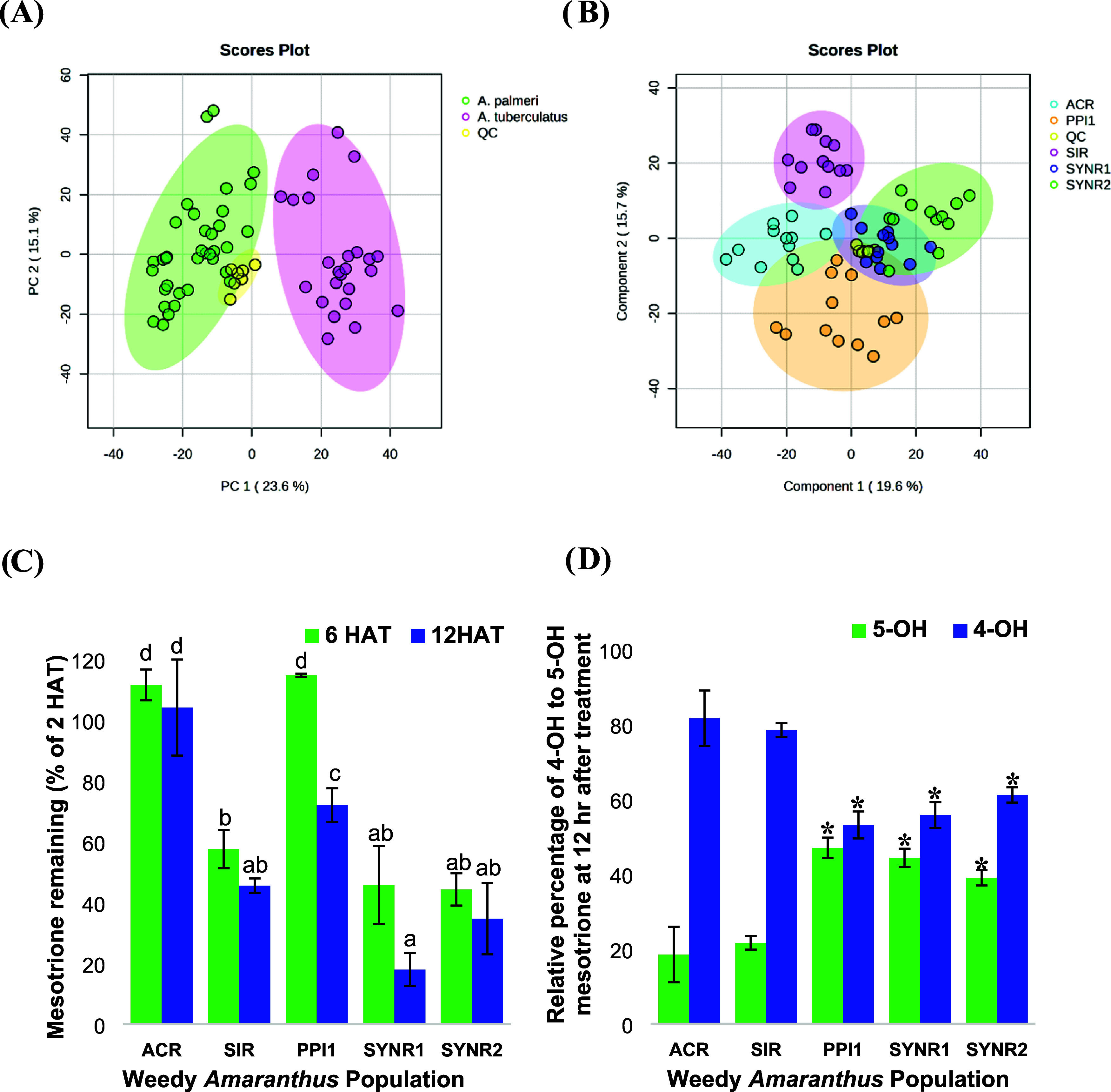

PCA shows innate biological differences in metabolite profiles between waterhemp and Palmer amaranth populations (Figure 5A). PLS-DA confirmed species-specific metabolite profiles between waterhemp populations SIR and ACR and Palmer amaranth populations SYNR1 and SYNR2 (mesotrione-resistant) and PPI1 (mesotrione-sensitive) (Figure 5B). Importantly, the peak abundance of mesotrione was significantly lower in SIR, SYNR1, and SYNR2 compared to the sensitive populations, ACR and PPI1, at 6 and 12 HAT (Figure 5C). Furthermore, Phase I mesotrione metabolites, 4-OH- and 5-OH-mesotrione, were detected in all populations and accumulated over time (Figure 5D); however, variations in their relative abundances were noted (Figure 5D). The metabolites 4-OH- and 5-OH-mesotrione were more abundant in SIR (mesotrione-resistant) than ACR (mesotrione-sensitive) waterhemp (Figure 4 and Figure 5D). Among Palmer amaranth populations, 4-OH- and 5-OH-mesotrione were more abundant in SYNR1 and SYNR2 than in PPI1 (Figure 4 and Figure 5D). However, waterhemp populations SIR and ACR produced 4-OH-mesotrione at 3.5 and 4.6-fold greater levels than 5-OH-mesotrione, whereas Palmer amaranth populations SYNR1, SYNR2, and PPI1 produced 4-OH-mesotrione at only 1.3, 1.8, and 1.3-fold greater levels than 5-OH-mesotrione (Figure 5D), indicating that 4-OH- and 5-OH-mesotrione metabolites are produced in similar amounts in Palmer amaranth compared to waterhemp. The identities of 4-OH- and 5-OH-mesotrione were confirmed using analytical standards. The MS2 fragment ion m/z 227 [M + H] is shared among mesotrione, 4-OH- and 5-OH-mesotrione (Figure 6 and Table 2). However, the functional significance of 4-OH- vs 5-OH-mesotrione metabolites in terms of potential phytotoxicity and overall detoxification processes remains to be determined.57

Figure 5.

Metabolite profiling of mesotrione-resistant Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) (SYNR1 and SYNR2), multiple-herbicide-resistant waterhemp (A. tuberculatus) (SIR), and mesotrione-sensitive Palmer amaranth (PPI1) and waterhemp (ACR) populations. (A) Principal components analysis scores scatter plot comparing Palmer amaranth and waterhemp (PC1 = 23.6%; PC2 = 15.1%). (B) PLS-DA scores plot of five populations at Component 1 (19.6%) and mesotrione resistance on Component 2 (15.7%). (C) Percentage of mesotrione at 2 HAT remaining in excised leaf extracts at 6 and 12 HAT. Differences in letters corresponding to each population per HAT denote a significant difference at p ≤ 0.05. p-value adjustment was performed using Tukey’s method for comparing a family of 10 estimates. (D) Relative percent abundance of 4- to 5-hydroxy-mesotrione metabolites (4-OH to 5-OH) at 12 HAT. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared to SIR via analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons of means at α = 0.05. Error bars correspond to the standard error of the mean across four replicates.

Figure 6.

Mass spectra and chemical structures of mesotrione (A), 4-OH mesotrione (B), and 5-OH mesotrione (C) in Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) and waterhemp (A. tuberculatus). Identities of these compounds were confirmed using analytical standards.

3.3.2. Untargeted Metabolite Profiling of Mesotrione Metabolites in Palmer amaranth

To quantify the rate of mesotrione metabolism and identify metabolites other than 4-OH- and 5-OH-mesotrione in Palmer amaranth populations (SYNR1, SYNR2, PPI1, and PPI2), untargeted metabolomics was performed using the excised leaf assay during a time course. Metabolite profiles of SYNR1 and SYNR2 are more similar compared to the two sensitive populations, PPI1 and PPI2 (Figure 7A). Within 24 h, mesotrione induced changes in metabolite profiles for all four populations. However, parent mesotrione is more characterizing for samples at earlier time points (2 and 4 HAT) than later time points (8, 12, and 24 HAT) (Figure 7A,7B), indicating degradation of the herbicide in treated leaves over time.32,34 Mesotrione is also more characterizing for the sensitive populations, PPI1 and PPI2, indicating a higher overall concentration of parent mesotrione in leaf tissues of sensitive plants.32,34 SYNR1 and SYNR2 metabolized 50% of mesotrione absorbed (DT50) by c.a. 7 h, which is more than 2-fold faster than PPI1 and PPI2 (DT50 = c.a. 16 h) (Figure 7C). PLS-DA modeling comparing metabolites in pooled control samples and the four Palmer amaranth populations indicated putative metabolites of mesotrione (Figure 7D) and reaffirmed the innate metabolome variations among Palmer amaranth populations (Figure 5). Based on the masses and retention times of these filtered metabolite features, those with m/z 356 [M + H] or m/z 354 [M - H] are valid putative mesotrione metabolite associated with resistance since these features were not detected in control samples and were significantly more abundant in resistant populations (Figure 7D).

Figure 7.

Metabolism of mesotrione in four Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) populations (PPI1, PPI2, SYNR1, and SYNR2). (A) Principal components analysis scores scatter plot of four Palmer amaranth populations with the four biological replicates at five time points (2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h after treatment (HAT)). (B) Loading scatter plot of metabolite features from these populations detected via liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. (C) Degradation of mesotrione (parent) herbicide throughout a time-course study. (D) Heatmap dendrogram comparing the 25 most discriminating metabolite features in mesotrione-treated Palmer amaranth populations and untreated control (Control) samples at 24 HAT.

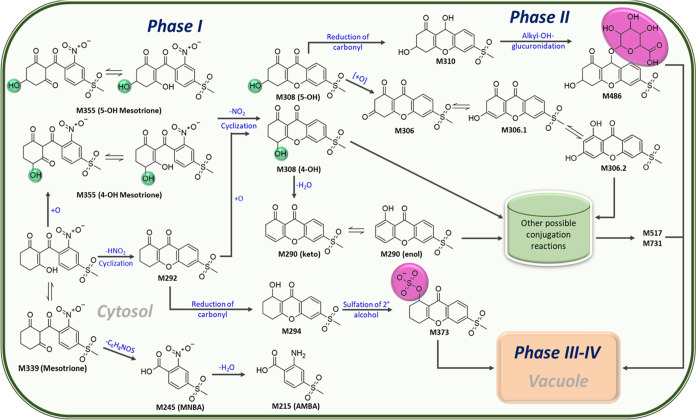

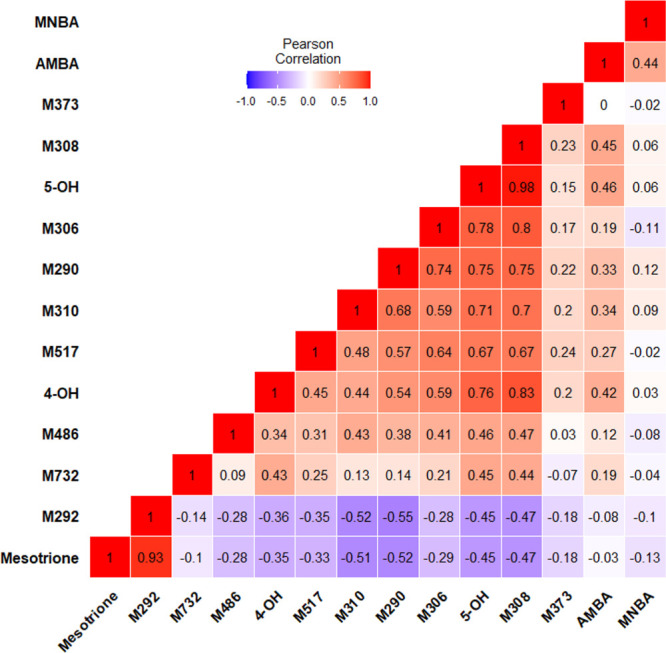

In addition to 4-OH- and 5-OH-mesotrione, other metabolite features may also represent mesotrione degradation products in Palmer amaranth (Figure 7D and Tables 2 and 3). Of these metabolites, MNBA (m/z 245 [M + H]) and AMBA (m/z 216 [M + H]) were identified, both of which are the main mesotrione degradation products in soil59 (Table 2). MNBA was detected at much lower abundances and did not yield any clear statistical associations with mesotrione, 4-OH-mesotrione, or 5-OH-mesotrione, likely because it is actively converted to AMBA during the time course (Figure 8). Putative metabolite features of mesotrione detected via LCMS (but without analytical standards) include the following: M290, M292, M306, M308, M517, M486, and M732 (Table 3). M486 was only detected in ESI(+) and did not yield MS2 ions but was more abundant at later time points across all Palmer amaranth populations in the study. M517, on the other hand, was only detected in ESI(−) but produced MS2 ions, which were also found in M354 and M308 (Table 3). Failed detection of these features in either ESI(+) and ESI(−) is likely due to the low abundance of these features or their formation later in the time course. Suppression effects on the sensitivity of ionization due to liquid chromatographic conditions and complex plant matrix interference may have decreased method detection limits for these metabolite features.58,60 Inverse peak abundances between these metabolite features and mesotrione over time (Figures 7 and 8) indicate that the metabolism of mesotrione leads to the formation of these metabolite features. M308 is likely an intermediate metabolite following the formation of 4-OH- and 5-OH-mesotrione (Figure 9) since it possesses MS2 ions similar to 4-OH- and 5-OH-mesotrione as well as M486 (Table 3), a putative sugar conjugate. M308 was a close match (structural isomer) to sulisobenzone or benzophenone-4 (molecular formula: C14H12O6S; IUPAC: 5-benzoyl-4-hydroxy-2-methoxybenzene-1-sulfonic acid in online databases (Figure S3)), which supports our hypothesis of M308 formation after loss of the NO2 moiety in 4-OH- or 5-OH-mesotrione (Figure 9). Removal of NO2 from mesotrione proceeds along with cyclization of the molecule into a xanthonoid feature M292, which has been reported previously in other sample sources for mesotrione57,61 and sulcotrione.61 In addition to mesotrione, 4-OH-, and 5-OH-mesotrione, the chemical composition of M308 was verified with SIRIUS software (Figures S4–S7). M308 can also be formed from the oxidation of M292. Possible Phase II metabolite features are M486 and M373, likely produced via alkyl-OH-glucuronidation of M310 (derived from carbonyl reduction in M308) and sulfation of secondary alcohol in M294 (derived from carbonyl reduction in M292), respectively (Figure 9). The presence of m/z 97 in ESI(−) for M373 supports the putative formation of a sulfated metabolite, M373,62 via Phase II sulfotransferase enzymes.63 Elimination of water from M308 produces M290, which can be further transformed into other conjugated features (Figure 9). Formation of these metabolite features with higher molecular weights and increased polarity compared to mesotrione, such as M486, M373, M517, and M732, implies biotransformation of mesotrione beyond Phase I oxidative reactions (formation of M355; Figure 9). However, their identities warrant further investigation.

Table 3. Mass Spectral Information of Putative Metabolites of Mesotrione Detected in Leaf Extracts of Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) via Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry.

| proposed

composition |

experimental m/z [M – H]− |

experimental m/z [M + H]+ |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | RT (min)a | molecular formula | monoisotopic massb | precursor | fragmentc | precursor | fragmentc |

| M290 | 15.458 | C14H10O5S | 290.0249 | 289.0184 | 289.0149 | 291.0316 | 291.0321 |

| 213.0180 | 244.0346 | ||||||

| 214.0245 | 200.0460 | ||||||

| 226.0260 | 228.0420 | ||||||

| 170.0346 | 212.0455 | ||||||

| 186.0308 | 216.0415 | ||||||

| M306 | 15.482 | C14H10O6S | 306.0198 | 305.0127 | 305.0132 | 307.0263 | 307.0269 |

| 61.0219 | 260.0314 | ||||||

| 242.0221 | 216.0412 | ||||||

| 229.0117 | 244.0348 | ||||||

| 233.0256 | 228.0415 | ||||||

| 185.0220 | 245.0432 | ||||||

| M308 | 15.369 | C14H12O6S | 308.0355 | 307.0282 | 289.0145 | 309.0421 | 263.0367 |

| 307.0297 | 291.0315 | ||||||

| 213.0179 | 309.0425 | ||||||

| 171.0109 | 216.0417 | ||||||

| 225.0558 | 200.0465 | ||||||

| 214.0274 | 155.0344 | ||||||

| M310 | 15.046 | C14H14O6S | 309.0240 | ||||

| M373 | 15.247 | C14H13O8S2 | 373.00518 | 372.0392 | 281.0490 | ||

| 171.0104 | |||||||

| 213.0209 | |||||||

| 372.0602 | |||||||

| 263.0378 | |||||||

| 199.0047 | |||||||

| M517 | 13.347 | 516.0809 | 306.0201 | ||||

| 289.0144 | |||||||

| 469.0828 | |||||||

| 243.0283 | |||||||

| 307.0248 | |||||||

| 171.0106 | |||||||

| M732 | 15.418 | 731.0498 | 307.0297 | 733.0601 | 378.02164 | ||

| 289.0148 | 331.02307 | ||||||

| 114.9742 | 107.77043 | ||||||

| 354.0264 | 309.04254 | ||||||

| 225.0555 | 157.43636 | ||||||

| 171.0104 | 109.33149 | ||||||

| M486d | 12.064 | C20H22O12S | 486.0832 | 486.9470 | |||

Retention time (RT) in minutes (min) of metabolite features in the negative electrospray ionization mode [ESI(−)].

Unit expressed in Daltons.

Top six MS2 fragment ions (high-to-low intensity) shown as mass-to-charge-ratio (m/z).

MS1 ion was detected in higher abundance in MHR compared to sensitive Palmer amaranth populations, but MS2 fragment ions were not detected.

Figure 8.

Correlation plot based on normalized relative peak abundance of mesotrione and its identified and putative metabolites detected via liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry of Amaranthus palmeri leaf extracts treated with 0.15 mM nonlabeled mesotrione across five time points (2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h after treatment). The strength and direction of the correlation are represented by Pearson’s r values indicated by each box color based on the scale of −1.0 (violet) to +1.0 (red).

Figure 9.

Proposed metabolic detoxification pathway for mesotrione in multiple-herbicide-resistant (MHR) Amaranthus palmeri leaves. Phase I hydroxylated metabolites of mesotrione were verified by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (−OH groups are circled in green). Potential Phase II conjugates of mesotrione (sulfate and sugar groups are circled in pink) are theoretical metabolites based on their mass spectral data.

Detection of metabolites resembling a putative sugar conjugate (M486) implies that mesotrione detoxification in Palmer amaranth proceeds from Phase I to Phase II, where mesotrione is further transformed into more hydrophilic, nonphytotoxic forms at a faster rate in resistant than in sensitive populations. Phase II metabolism via GSH conjugation occurs enzymatically and nonenzymatically with the PRE herbicides atrazine32 and S-metolachlor64 and was a recently reported, novel detoxification mechanism for a noncommercial, HPPD-inhibiting herbicide (SA3) in SIR and NEB waterhemp.41 Unlike SA3, mesotrione and its metabolites lack a reactive α,β-unsaturated carbon, which makes Phase II thiolate anion conjugation improbable (Figure 9). However, Phase I hydroxylation is likely the rate-limiting step for further metabolism of mesotrione, which means the enzyme catalyzing this oxidative process must be present and active in MHR compared to sensitive populations at a rate that confers resistance at the whole plant level. Although P450s are plausible enzymes associated with Phase I hydroxylation of mesotrione, differences in the abundance of 4-OH- and 5-OH-mesotrione between MHR waterhemp and Palmer amaranth populations (Figures 4, 5, and 7) imply that different P450 enzymes may catalyze the formation of each metabolite, as well as other possible oxidative enzymes conferring HPPD-inhibitor resistance in weeds. For example, non-P450 Phase I genes and enzymes are associated with tolerance to HPPD inhibitors in rice (Oryza sativa L.); the rice HPPD INHIBITOR SENSITIVE 1 (HIS1) gene encodes an Fe(II)/2-oxoglutarate-dependent oxygenase that catalyzes detoxification of β-triketone HPPD-inhibiting herbicides.65 The HIS1 gene also conferred resistance to mesotrione in transgenic soybean.57 Furthermore, in wild radish (Raphanus raphanistrum), a 2-oxoglutarate/Fe(II)-dependent dioxygenase (Rr2ODD1), in addition to two P450 genes, confers resistance to HPPD-inhibiting herbicides mesotrione, tembotrione and isoxaflutole.28

Rapid metabolic detoxification of mesotrione is a major NTSR mechanism in the Palmer amaranth populations (SYNR1 and SYNR2) investigated in this study. These MHR populations produced qualitatively similar mesotrione metabolites as MHR waterhemp (SIR), which implies a similar class (or classes) of detoxification enzymes is responsible for resistance. Increased relative abundance of 5-OH-mesotrione in Palmer amaranth compared to waterhemp indicates a different detoxification mechanism in Palmer amaranth; however, given the multigenic nature of HPPD-inhibitor resistance28,66,67 and recent reports on roles of other genes/enzymes in mesotrione resistance,28,41,68 a combination of P450s, other (non-P450) oxygenases, and/or GSTs could possibly confer resistance to HPPD-inhibiting herbicides in weedy amaranths.

Our ongoing and future work aims to identify the precise underlying basis for HPPD-inhibiting herbicide resistance in MHR waterhemp and Palmer amaranth. Despite the significant effects of P450 inhibitors in slowing metabolism and synergizing the activity of HPPD-inhibiting herbicides,32,69 the lack of direct evidence regarding possible roles of P450s in conferring resistance to these herbicides in waterhemp70 indicates that further research is required to fully elucidate the molecular-genetic basis of resistance. It is also important to investigate whether potential target-site resistance (TSR) mechanisms, such as alterations in HPPD protein sequence, enzyme activity, or increased HPPD expression levels, contribute to mesotrione resistance35 since these TSR mechanisms were not investigated in the current study. Moreover, metabolic profiles of other maize-selective HPPD-inhibiting herbicides, such as topramezone and tembotrione, as well as SA3 and other nonselective herbicides theoretically robust to oxidative metabolism, will be investigated. Results gained from this research will enhance our current knowledge of the metabolic fate of HPPD-inhibiting herbicides in plants and inform their effective use for managing weedy Amaranthus and other dicot weeds in maize.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the following researchers: Drs. Peter Yau and Brian Imai of the Roy J. Carver Biotechnology Center Proteomics Core Facility, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign (UIUC), for assistance with phosphor-imaging of TLC plates; Drs. Zhong Li, Michael La Frano, and Alexander Ulanov for providing metabolite profiling services at the UIUC Metabolomics Laboratory; Sarah-Jane Hutchings and Will Plumb (Syngenta-Ltd.) for assistance in initial greenhouse screening and bulking up seeds of Palmer amaranth populations; Rosie Metallo, Montgomery Flack, Alison Ross, Noeleen Brown, Molly Newman-Johnson, and Stuart Seputro (UIUC) for their assistance in greenhouse studies and maintenance of plant samples for metabolism experiments. D.E.R. and A.N.B. thank the Weed Science Society of America for supporting this research through the John Jachetta Undergraduate Research Award. The authors also thank Syngenta-Ltd. for providing seeds of weedy Amaranthus, mesotrione, and metabolite standards.

Data Availability Statement

Data from the LCMS experiments are available on MassIVE (Reference Numbers MSV000092291 and MSV000092317).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jafc.3c06903.

Twenty-two Amaranthus palmeri populations and their responses to foliar-applied mesotrione (Table S1); representative plants of eight Palmer amaranth (A. palmeri) and two waterhemp (A. tuberculatus) populations (SIR and ACR) treated with mesotrione (105 g a.i. ha–1) plus adjuvants compared with untreated controls, 14 DAT (Figure S1); HPLC radiochromatograms of excised leaf extracts from a radiolabeled mesotrione metabolism assay in a moderately resistant Palmer amaranth (A. palmeri) population, PS-2410 (Figure S2); chemical structure of sulisobenzone or benzophenone-4 (IUPAC: 5-benzoyl-4-hydroxy-2-methoxybenzene-1-sulfonic acid) (Figure S3); fragmentation tree of mesotrione in the negative electrospray ionization mode (Figure S4); fragmentation tree of 4-hydroxy-mesotrione in the negative electrospray ionization mode (Figure S5); fragmentation tree of 5-hydroxy-mesotrione in the negative electrospray ionization mode (Figure S6); fragmentation tree of M308 in the negative electrospray ionization mode (Figure S7); and representative mass spectral fragment ions of metabolite features of mesotrione in Palmer amaranth (A. palmeri) populations in the negative electrospray ionization mode (Figure S8). (PDF)

Author Contributions

S.S.K., D.E.R., and J.C.T.C. designed the study. J.C.T.C. performed the greenhouse experiments. J.C.T.C. and A.N.B. performed the metabolism experiments. J.C.T.C. analyzed the greenhouse data. J.C.T.C. and J.A.M. analyzed the metabolomics data. S.S.K. and D.E.R. provided advice to the lead author. J.C.T.C. wrote the manuscript. All authors revised and approved the manuscript.

Financial support for this study was provided by Syngenta-Ltd. and the Weed Science Society of America.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ward S. M.; Webster T. M.; Steckel L. E. Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri): a review. Weed Technol. 2013, 27, 12–27. 10.1614/WT-D-12-00113.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keeley P. E.; Thullen R. J. Growth and competition of black nightshade (Solanum nigrum) and Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) with cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). Weed Sci. 1989, 37, 326–334. 10.1017/S0043174500072003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klingaman T. E.; Oliver L. R. Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) interference in soybeans (Glycine max). Weed Sci. 1994, 42, 523–527. 10.1017/S0043174500076888. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bensch C. N.; Horak M. J.; Peterson D. Interference of redroot pigweed (Amaranthus retroflexus), Palmer amaranth (A. palmeri), and common waterhemp (A. rudis) in soybean. Weed Sci. 2003, 51, 37–43. 10.1614/0043-1745(2003)051[0037:IORPAR]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Massinga R. A.; Currie R. S.; Horak M. J.; Boyer J. Interference of Palmer amaranth in corn. Weed Sci. 2001, 49, 202–208. 10.1614/0043-1745(2001)049[0202:IOPAIC]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heap I.International Herbicide-Resistant Weed Database. www.weedscience.org (accessed August 12, 2023).

- Sauer J. Revision of the dioecious Amaranths. Madroño 1955, 13, 5–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ehleringer J. Ecophysiology of Amaranthus palmeri, a Sonoran desert summer annual. Oecologia 1983, 57, 107–112. 10.1007/BF00379568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeley P. E.; Carter C. H.; Thullen R. J. Influence of planting sate on growth of Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri). Weed Sci. 1987, 35, 199–204. 10.1017/S0043174500079054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jha P.; Norsworthy J. K.; Garcia J. Depletion of an artificial seed bank of Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) over four years of burial. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 1599–1606. 10.4236/ajps.2014.511173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horak M. J.; Loughin T. M. Growth analysis of four Amaranthus species. Weed Sci. 2000, 48, 347–355. 10.1614/0043-1745(2000)048[0347:GAOFAS]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jha P.; Norsworthy J. K. Soybean canopy and tillage effects on emergence of Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) from a natural seed bank. Weed Sci. 2009, 57, 644–651. 10.1614/WS-09-074.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu E.; Blair S.; Hardel M.; Chandler M.; Thiede D.; Cortilet A.; Gunsolus J.; Becker R. Timeline of Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) invasion and eradication in Minnesota. Weed Technol. 2021, 35, 802–810. 10.1017/wet.2021.32. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt C.; Vorster J.; Küpper A.; Peter F.; Simelane A.; Friis S.; Magson J.; Aradhya C. A nonnative Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) population in the Republic of South Africa is resistant to herbicides with different sites of action. Weed Sci. 2022, 70, 183–197. 10.1017/wsc.2022.9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ndikuryayo F.; Moosavi B.; Yang W.-C.; Yang G.-F. 4-Hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase inhibitors: from chemical biology to agrochemicals. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 8523–8537. 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b03851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L.; DellaPenna D.; Dixon R. A. The pds2 mutation is a lesion in the Arabidopsis homogentisate solanesyltransferase gene involved in plastoquinone biosynthesis. Planta 2007, 226, 1067–1073. 10.1007/s00425-007-0564-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler S. E.; Gilliland L. U.; Magallanes-Lundback M.; Pollard M.; DellaPenna D. Vitamin E is essential for seed longevity and for preventing lipid peroxidation during germination. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 1419–1432. 10.1105/tpc.021360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausman N. E.; Singh S.; Tranel P. J.; Riechers D. E.; Kaundun S. S.; Polge N. D.; Thomas D. A.; Hager A. G. Resistance to HPPD-inhibiting herbicides in a population of waterhemp (Amaranthus tuberculatus) from Illinois, United States. Pest Manage. Sci. 2011, 67, 258–261. 10.1002/ps.2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witschel M. Design, synthesis and herbicidal activity of new iron chelating motifs for HPPD-inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 4221–4229. 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudegnies R.; De Mesmaeker A.; Mallinger A.; Baalouch M.; Goetz A. Design and synthesis of novel spirocyclopropyl cyclohexane-1,3-diones and −1,3,5-triones for their incorporation into potent HPPD inhibitors. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010, 51, 2741–2744. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2010.03.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. L.; Prisbylla M. P.; Cromartie T. H.; Dagarin D. P.; Howard S. W.; Provan W. M.; Ellis M. K.; Fraser T.; Mutter L. C. The discovery and structural requirements of inhibitors of p-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase. Weed Sci. 1997, 45, 601–609. 10.1017/S0043174500093218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. L.; Knudsen C. G.; Michaely W. J.; Chin H.-L.; Nguyen N. H.; Carter C. G.; Cromartie T. H.; Lake B. H.; Shribbs J. M.; Fraser T. The structure–activity relationships of the triketone class of HPPD herbicides. Pestic. Sci. 1998, 54, 377–384. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell G.; Bartlett D. W.; Fraser T. E. M.; Hawkes T. R.; Holt D. C.; Townson J. K.; Wichert R. A. Mesotrione: a new selective herbicide for use in maize. Pest Manage. Sci. 2001, 57, 120–128. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurse R. E.; Hamill A. S.; Swanton C. J.; Tardif F. J.; Sikkema P. H. Weed control and yield response to mesotrione in maize (Zea mays). Crop Prot. 2010, 29, 652–657. 10.1016/j.cropro.2010.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen C. G.; Lee D. L.; Michaely W. J.; Chin H.-L.; Nguyen N. H.; Rusay R. J.; Cromartie T. H.; Gray R.; Lake B. H.; Fraser T. E. M.; Cartwright D.. Discovery of the Triketone Class of HPPD Inhibiting Herbicides and Their Relationship to Naturally Occurring β-Triketones. In Allelopathy in Ecological Agriculture and Forestry: Proceedings of the III International Congress on Allelopathy in Ecological Agriculture and Forestry; Narwal S. S.; Hoagland R. E.; Dilday R. H.; Reigosa M. J., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2000; pp 101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Sandermann H. Plant metabolism of xenobiotics. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1992, 17, 82–84. 10.1016/0968-0004(92)90507-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman J.; Blake-Kalff M.; Davies E. Detoxification of xenobiotics by plants: chemical modification and vacuolar compartmentation. Trends Plant Sci. 1997, 2, 144–151. 10.1016/S1360-1385(97)01019-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H.; Liu Y.; Li M.; Han H.; Zhou F.; Nyporko A.; Yu Q.; Qiang S.; Powles S. Multiple metabolic enzymes can be involved in cross-resistance to 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate-dioxygenase-inhibiting herbicides in wild radish. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 9302–9313. 10.1021/acs.jafc.3c01231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busi R.; Gaines T. A.; Powles S. Phorate can reverse P450 metabolism-based herbicide resistance in Lolium rigidum. Pest Manage. Sci. 2017, 73, 410–417. 10.1002/ps.4441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuz K.; Fonné-Pfister R. Herbicide-insecticide interaction in maize: malathion inhibits cytochrome P450-dependent primisulfuron metabolism. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 1992, 43, 232–240. 10.1016/0048-3575(92)90036-Y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hausman N. E.; Tranel P.; Riechers D.; Maxwell D.; Gonzini L.; Hager A. G. Responses of an HPPD inhibitor-resistant waterhemp (Amaranthus tuberculatus) population to soil-residual herbicides. Weed Technol. 2013, 27, 704–711. 10.1614/WT-D-13-00032.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma R.; Kaundun S. S.; Tranel P. J.; Riggins C. W.; McGinness D. L.; Hager A. G.; Hawkes T.; McIndoe E.; Riechers D. E. Distinct detoxification mechanisms confer resistance to mesotrione and atrazine in a population of waterhemp. Plant Physiol. 2013, 163, 363–377. 10.1104/pp.113.223156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes T.; Holt D. C.; Andrews C. J.; Thomas P. G.; Langford M.; Hollingworth S.; Mitchell G. In Mesotrione: Mechanism of Herbicidal Activity and Selectivity in Corn, Brighton Crop Protection Conference Proceedings – Weeds, 2001; pp 563–568.

- Kaundun S. S.; Hutchings S.-J.; Dale R. P.; Howell A.; Morris J. A.; Kramer V. C.; Shivrain V. K.; McIndoe E. Mechanism of resistance to mesotrione in an Amaranthus tuberculatus population from Nebraska, USA. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0180095 10.1371/journal.pone.0180095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakka S.; Godar A. S.; Wani P. S.; Thompson C. R.; Peterson D. E.; Roelofs J.; Jugulam M. Physiological and molecular characterization of hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase (HPPD)-inhibitor resistance in Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri S.Wats.). Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 555. 10.3389/fpls.2017.00555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausman N. E.; Tranel P. J.; Riechers D. E.; Hager A. G. Responses of a waterhemp (Amaranthus tuberculatus) population resistant to HPPD-inhibiting herbicides to foliar-applied herbicides. Weed Technol. 2016, 30, 106–115. 10.1614/WT-D-15-00098.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strom S. A.; Gonzini L. C.; Mitsdarfer C.; Davis A. S.; Riechers D. E.; Hager A. G. Characterization of multiple herbicide–resistant waterhemp (Amaranthus tuberculatus) populations from Illinois to VLCFA-inhibiting herbicides. Weed Sci. 2019, 67, 369–379. 10.1017/wsc.2019.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs K. E.; Butts-Wilmsmeyer C. J.; Ma R.; O’Brien S. R.; Riechers D. E. Association between metabolic resistances to atrazine and mesotrione in a multiple-resistant waterhemp (Amaranthus tuberculatus) population. Weed Sci. 2020, 68, 358–366. 10.1017/wsc.2020.31. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lygin A. V.; Kaundun S. S.; Morris J. A.; Mcindoe E.; Hamilton A. R.; Riechers D. E. Metabolic pathway of topramezone in multiple-resistant waterhemp (Amaranthus tuberculatus) differs from naturally tolerant maize. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1644. 10.3389/fpls.2018.01644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obenland O. A.; Ma R.; O’Brien S. R.; Lygin A. V.; Riechers D. E. Carfentrazone-ethyl resistance in an Amaranthus tuberculatus population is not mediated by amino acid alterations in the PPO2 protein. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0215431 10.1371/journal.pone.0215431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concepcion J. C. T.; Kaundun S. S.; Morris J. A.; Hutchings S.-J.; Strom S. A.; Lygin A. V.; Riechers D. E. Resistance to a nonselective 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase-inhibiting herbicide via novel reduction–dehydration–glutathione conjugation in Amaranthus tuberculatus. New Phytol. 2021, 232, 2089–2105. 10.1111/nph.17708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma R.; Skelton J. J.; Riechers D. E. Measuring rates of herbicide metabolism in dicot weeds with an excised leaf assay. J. Vis. Exp. 2015, 103, 53236 10.3791/53236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangster T.; Major H.; Plumb R.; Wilson A. J.; Wilson I. D. A pragmatic and readily implemented quality control strategy for HPLC-MS and GC-MS-based metabonomic analysis. Analyst 2006, 131, 1075–1078. 10.1039/b604498k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn W. B.; Broadhurst D.; Begley P.; Zelena E.; Francis-McIntyre S.; Anderson N.; Brown M.; Knowles J. D.; Halsall A.; Haselden J. N.; Nicholls A. W.; Wilson I. D.; Kell D. B.; Goodacre R. Procedures for large-scale metabolic profiling of serum and plasma using gas chromatography and liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry. Nat. Protoc. 2011, 6, 1060. 10.1038/nprot.2011.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godzien J.; Alonso-Herranz V.; Barbas C.; Armitage E. G. Controlling the quality of metabolomics data: new strategies to get the best out of the QC sample. Metabolomics 2015, 11, 518–528. 10.1007/s11306-014-0712-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrens R.; Hageman J. A.; van Eeuwijk F.; Kooke R.; Flood P. J.; Wijnker E.; Keurentjes J. J. B.; Lommen A.; van Eekelen H. D. L. M.; Hall R. D.; Mumm R.; de Vos R. C. H. Improved batch correction in untargeted MS-based metabolomics. Metabolomics 2016, 12, 88. 10.1007/s11306-016-1015-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsugawa H.; Cajka T.; Kind T.; Ma Y.; Higgins B.; Ikeda K.; Kanazawa M.; VanderGheynst J.; Fiehn O.; Arita M. MS-DIAL: data-independent MS/MS deconvolution for comprehensive metabolome analysis. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 523–526. 10.1038/nmeth.3393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knezevic S. Z.; Streibig J. C.; Ritz C. Utilizing R software package for dose-response studies: The concept and data analysis. Weed Technol. 2007, 21, 840–848. 10.1614/WT-06-161.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adusumilli R.; Mallick P.; Comai L.; Katz J. E.; Mallick P.. Data Conversion with ProteoWizard msConvert. In Proteomics: Methods and Protocols; Springer: New York, NY, 2017; pp 339–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J.; Wishart D. S. Web-based inference of biological patterns, functions and pathways from metabolomic data using MetaboAnalyst. Nat. Protoc. 2011, 6, 743. 10.1038/nprot.2011.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza L. P.; Alseekh S.; Naake T.; Fernie A. Mass spectrometry-based untargeted plant metabolomics. Curr. Protoc. Plant Biol. 2019, 4, e20100 10.1002/cppb.20100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thévenot E. A.; Roux A.; Xu Y.; Ezan E.; Junot C. Analysis of the human adult urinary metabolome variations with age, body mass index, and gender by implementing a comprehensive workflow for univariate and OPLS statistical analyses. J. Proteome Res. 2015, 14, 3322–3335. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart D. S.; Tian S.; Allen D.; Oler E.; Peters H.; Lui; Vicki W.; Gautam V.; Djoumbou-Feunang Y.; Greiner R.; Metz; Thomas O. BioTransformer 3.0—a web server for accurately predicting metabolic transformation products. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50 (W1), W115–W123. 10.1093/nar/gkac313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dührkop K.; Fleischauer M.; Ludwig M.; Aksenov A.; Melnik A.; Meusel M.; Dorrestein P.; Rousu J.; Böcker S. SIRIUS 4: a rapid tool for turning tandem mass spectra into metabolite structure information. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 299–302. 10.1038/s41592-019-0344-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han H.; Yu Q.; Beffa R.; González S.; Maiwald F.; Wang J.; Powles S. B. Cytochrome P450 CYP81A10v7 in Lolium rigidum confers metabolic resistance to herbicides across at least five modes of action. Plant J. 2021, 105, 79–92. 10.1111/tpj.15040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q.; Powles S. Metabolism-based herbicide resistance and cross-resistance in crop weeds: a threat to herbicide sustainability and global crop production. Plant Physiol. 2014, 166, 1106–1118. 10.1104/pp.114.242750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai S.; Georgelis N.; Bedair M.; Hong Y. J.; Qi Q.; Larue C.; Sitoula B.; Huang W.; Krebel B.; Shepard M.; Su W.; Kretzmer K.; Dong J.; Slewinski T.; Berger S.; Ellis C.; Jerga A.; Varagona M. Ectopic expression of a rice triketone dioxygenase gene confers mesotrione tolerance in soybean. Pest Manage. Sci. 2022, 78, 2816–2827. 10.1002/ps.6904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas L. G.; Götz C. W.; Ruff M.; Singer H. P.; Müller S. R. Quantification of the new triketone herbicides, sulcotrione and mesotrione, and other important herbicides and metabolites, at the ng/l level in surface waters using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2004, 1028, 277–286. 10.1016/j.chroma.2003.11.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barchanska H.; Kluza A.; Krajczewska K.; Maj J. Degradation study of mesotrione and other triketone herbicides on soils and sediments. J. Soils Sediments 2016, 16, 125–133. 10.1007/s11368-015-1188-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marchese S.; Perret D.; Gentili A.; D’Ascenzo G.; Faberi A. Determination of phenoxyacid herbicides and their phenolic metabolites in surface and drinking water. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2002, 16, 134–141. 10.1002/rcm.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ter Halle A.; Drncova D.; Richard C. Phototransformation of the herbicide sulcotrione on maize cuticular wax. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 2989–2995. 10.1021/es052266h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi L.; Dratter J.; Wang C.; Tunge J. A.; Desaire H. Identification of sulfation sites of metabolites and prediction of the compounds’ biological effects. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2006, 386, 666–674. 10.1007/s00216-006-0495-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaassen C. D.; Boles J. W. The importance of 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate (PAPS) in the regulation of sulfation. FASEB J. 1997, 11, 404–418. 10.1096/fasebj.11.6.9194521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strom S. A.; Hager A. G.; Concepcion J. C. T.; Seiter N. J.; Davis A. S.; Morris J. A.; Kaundun S. S.; Riechers D. E. Metabolic pathways for S-metolachlor detoxification differ between tolerant corn and multiple-resistant waterhemp. Plant Cell Physiol. 2021, 62, 1770–1785. 10.1093/pcp/pcab132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda H.; Murata K.; Sakuma N.; Takei S.; Yamazaki A.; Karim M. R.; Kawata M.; Hirose S.; Kawagishi-Kobayashi M.; Taniguchi Y.; Suzuki S.; Sekino K.; Ohshima M.; Kato H.; Yoshida H.; Tozawa Y. A rice gene that confers broad-spectrum resistance to β-triketone herbicides. Science 2019, 365, 393–396. 10.1126/science.aax0379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman J.; Hausman N. E.; Hager A. G.; Riechers D. E.; Tranel P. J. Genetics and inheritance of nontarget-site resistances to atrazine and mesotrione in a waterhemp (Amaranthus tuberculatus) population from Illinois. Weed Sci. 2015, 63, 799–809. 10.1614/WS-D-15-00055.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shyam C.; Nakka S.; Putta K.; Cuvaca I.; Currie R. S.; Jugulam M. Genetic basis of chlorsulfuron, atrazine, and mesotrione resistance in a Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) population. ACS Agric. Sci. Technol. 2021, 1, 109–114. 10.1021/acsagscitech.1c00005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ju B.; Liu M.; Fang Y.; Liu L.; Pan L. First report on resistance to HPPD herbicides mediated by nontarget-site mechanisms in the grass Leptochloa chinensis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 17669–17677. 10.1021/acs.jafc.3c04323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira M. C.; Gaines T. A.; Dayan F. E.; Patterson E. L.; Jhala A. J.; Knezevic S. Z. Reversing resistance to tembotrione in an Amaranthus tuberculatus (var. rudis) population from Nebraska, USA with cytochrome P450 inhibitors. Pest Manage. Sci. 2018, 74, 2296–2305. 10.1002/ps.4697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy B. P.; Beffa R.; Tranel P. J. Genetic architecture underlying HPPD-inhibitor resistance in a Nebraska Amaranthus tuberculatus population. Pest Manage. Sci. 2021, 77, 4884–4891. 10.1002/ps.6560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data from the LCMS experiments are available on MassIVE (Reference Numbers MSV000092291 and MSV000092317).