Abstract

Purpose

People with cancer experience significant physical and psychological symptoms, during as well as after primary treatment. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), a psychological intervention, reduces both types of symptoms among individuals with chronic pain and emotional distress. Due to the unique challenges of cancer survivorship, this systematic review critically evaluates and synthesizes the literature on the context, mechanisms, and effect of ACT among adult cancer survivors.

Methods

Articles were retrieved from the CINAHL, MEDLINE via Ovid, Web of Science, PsycInfo, Scopus, Embase, Google Scholar, and Cochrane databases. Selected grey literature portals, clinical trial registries, and conference proceedings were also searched. The NIH tools were used to assess study quality and the revised Cochrane Risk-of-Bias tool to assess risk of bias

Results

Thirteen articles, reporting on 537 cancer survivors with various cancer types, were included. ACT significantly reduced anxiety, depression, and fear of cancer recurrence and improved psychological flexibility and quality of life. Outcomes such as pain and insomnia were understudied. Lack of participant blinding and non-random assignment were the most common methodological issues. A conceptual model is proposed that describes the possible influencing factors of an ACT-based intervention in cancer survivors.

Conclusion

Review findings suggest that ACT is an effective intervention to improve some of the common concerns among cancer survivors. While all the studies in the review were recent (published 2015–2019), they examined only a limited number of outcomes. Hence, more methodologically rigorous studies which examine the effect of ACT on other troubling symptoms among cancer survivors are warranted.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Incorporating ACT into comprehensive post-treatment survivorship care can enhance psychological flexibility and reduce anxiety, depression, and fear.

Keywords: Cancer survivor, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Systematic review, Symptoms, Conceptual model

Introduction

The cancer survival rate in the USA has steadily improved over the past decade. The 5-year relative survival rate for all cancers combined currently stands at 67% overall, 68% in whites, and 62% in blacks [1]. Cancer prevalence reports as of January 2019 indicate that the majority of cancer survivors (68%) were diagnosed 5 or more years ago, and 18% were diagnosed 20 or more years ago [2]. As increasing numbers of individuals progress into the survivorship phase, many struggle with multiple physical and psychological symptoms, such as anxiety, pain, fatigue, insomnia, depression, and fear of cancer recurrence (FCR). These symptoms often persist for more than 10 years’ post-treatment [3–11]. For instance, the prevalence of chronic pain among cancer survivors ranges from 16 to 50% [12], and the lifetime prevalence for any mental health issue is around 56% [3]. Such symptoms rarely occur in isolation but form a symptom cluster that often has multiplicative effects [13]. Cancer survivors have ongoing concerns about cancer recurrence and have a tendency to perceive stressors as more severe, which in turn can have a significant impact on mood and physical symptoms [11]. Psychological distress is aggravated when survivors face daily challenges, stressors, and physical symptoms without adequate preparation for transition to post-treatment care [9]. In addition, for cancer survivors with pain, concerns about long-term effects of opioids, addiction potential, and lack of standardized protocols for opioid tapering have resulted in limited use of opioids [8]. All these factors indicate an increasing need for psycho-oncological support for individuals with physical and psychological symptoms after completion of primary cancer treatment. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for survivorship also advocate psychological support and a multimodal approach to pain management [14]. To achieve this goal, it becomes necessary to evaluate non-pharmacological approaches for symptom management among cancer survivors.

Meta-analysis confirms that psychological interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) are effective in reducing physical symptoms across the cancer continuum into survivorship [15]. CBT has also been studied for improving quality of life (QoL) and managing symptoms such as anxiety and depression during cancer treatment [16, 17]. One of the third-wave interventions of CBT is Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) which is a behavioral and cognitive intervention that produces psychological flexibility through processes of acceptance, mindfulness, commitment, and behavior change [18–20]. Specifically, the six core therapeutic processes of ACT are acceptance, cognitive defusion, contact with present moment, self-as-context, values, and committed action. ACT has been researched for chronic pain and has shown significant improvements in pain and social, physical, and emotional functioning that last up to 3 months’ post-treatment [17, 21, 22]. There has been increasing use of ACT among individuals with cancer in the past two decades [23–25]. A recent systematic review among cancer patients reported that patients who received ACT-based interventions showed improvements in emotional states, QoL, and psychological flexibility [23]. This review also stressed the importance of randomized controlled trials to compare the efficacy of ACT with other therapies. However, this review lacked a specific focus on survivorship and included only published studies. Survivors of cancer face challenges that are unique compared with other populations and even to cancer patients undergoing treatment. For example, individuals receive cancer treatment in structured hospital settings with good support systems, while individuals who have completed primary cancer treatment transition out of hospitals, often with little or no follow-up and inadequate preparation [9]. There remains a need to understand the effect of ACT specifically in cancer survivorship.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no systematic review has synthesized the literature on the effect of ACT among cancer survivors. Therefore, the investigators conducted a systematic review to critically evaluate and synthesize the ACT literature relating to adult cancer survivors and to summarize the mechanisms, influencing factors and effect of ACT. The literature has proposed multiple definitions for cancer survivor [26]. For the purpose of this review, cancer survivor is defined as an individual who has received a cancer diagnosis and completed their primary treatment (excluding maintenance treatment) [27]. The specific review questions were:

In what context was the ACT-based intervention delivered?

What processes and mechanisms formed the content of the intervention?

How was the intervention delivered to and accepted by cancer survivors?

What outcomes were studied?

What was the effect of ACT on these outcomes?

What gaps in this field need to be addressed by future research?

Methods

This systematic review was guided by the Cochrane guidelines for systematic review [28–36], Garrard’s structured review method [37], and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [38]. Keywords and search strings were identified in selected databases in an iterative process, and study titles were sampled for relevance through a pilot scoping search. The iterative process revealed that the term Acceptance and Commitment Therapy was listed under cognitive therapy if the search limits included years before 2004, and both acceptance and commitment therapy and mindfulness were listed as subheadings under cognitive therapy. In view of this finding, and as recommended by the Cochrane guidelines [31, 32] and Bates [39], a high-recall search using multiple strategies was done to retrieve articles which otherwise could have been missed.

Screening and study selection

Two authors (AM and AZD) determined the study selection criteria. These criteria were decided based on the focus of the systematic review—use of ACT-based interventions in quantitative studies among individuals who have completed primary cancer treatment. A two-step screening process was adopted for the review. First, the article titles and abstracts were screened for the following inclusion criteria: (a) experimental studies, including pilot and single-arm studies, (b) population exclusively of adult cancer survivors who had completed primary treatment (excluding maintenance treatment) at the onset of the study and (c) interventions based on ACT processes, either solely or in combination with other therapies. Those that met the inclusion criteria were deemed eligible for the full-text screening process. Articles that lacked clarity regarding research population and/or intervention (n = 18) were also subjected to full-text screening, and this was performed by two reviewers (AM and AZD). Kappa analysis revealed 82.4% agreement, and all disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached. Studies were excluded based on the exclusion criteria: (a) ineligible populations-participants with advanced cancer or metastatic disease (b) studies not available in English (c) studies describing qualitative results alone (d) conference abstracts and (e) study protocols.

Search strategies and data sources

The investigators searched eight databases, including the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), MEDLINE via Ovid, Web of Science, PsycINFO, Scopus, Embase, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), during the period from 24 September 2019 through 7 October 2019. Search terms included acceptance and commitment therapy, OR mindfulness, OR cognitive therapy; AND cancer survivor. The search was customized to each database. For instance, MeSH terms for Medline, Subject Headings for CINAHL, mapping options for Embase, and Thesaurus search for PsycInfo were used. Database-specific field designators, nesting features, and proximity operators such as N/4, adj4, cancer survivor [*5], were used to improve search sensitivity and comprehensiveness. Additional information on the search strings are given in Online resource (ESM Table). In Google Scholar, the first 900 records were examined. Because ACT was developed in the early 1980s, database searches were limited to articles published from January, 1980, to October, 2019, and included articles of all study designs and all languages. Ancestry searches were performed on studies that met the inclusion criteria. In addition, journal runs [39] were conducted, wherein, three core journals in areas of cancer survivorship and behavioural health were identified (Psycho-Oncology, Journal of Cancer Survivorship, and Cognitive and Behavioral Practice) and specific volume years were searched for relevant articles. Citation searching was also performed via the Science Citation Index Expanded and Social Sciences Citation Index. Grey literature searches were completed in OpenGrey, ProQuest “Dissertations and Theses@CIC,” NIH Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools (RePORT), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Annualreviews.org, and ClinicalTrials.gov, to minimize publication bias. Two 60-minute sessions with a health sciences librarian enhanced the search and retrieval efforts.

Data extraction and synthesis

Garrard’s matrix method [37] guided the data extraction and synthesis. Using a spreadsheet, data from the included articles were extracted in ascending chronological order with nine column topics: journal and author details; study design and purpose; cancer type; participant characteristics; ACT processes used; mode of intervention delivery, frequency, duration, and adherence; outcomes and measures; effect of intervention; and study strengths and limitations. Due to the heterogeneity of the studies, a narrative, descriptive synthesis was used, and the results were categorically and narratively summarized [37, 40]. Data pertaining to key characteristics of study, participants, and interventions; ACT processes; measures and outcomes; and effect of intervention were categorically depicted in matrices to facilitate synthesis. Data relating to influencing factors and intervention personnel and materials were narratively summarized.

Study quality and risk of bias assessment

AM and MKJ assessed study quality using the design-specific National Institutes of Health (NIH) quality assessment tools [41], with scales consisting of 14 items (for interventional and cohort studies), 12 items (for single-arm pre-post-studies), or 9 items (for case-series studies). Each study was assigned a score based on the items and was interpreted as good, fair, or poor based on previous use of the tools by other systematic review authors [42] and in consensus with the authors of this review. Table 1 describes the interpretation of quality assessment scores for each study design.

Table 1.

Interpretation of quality assessment scores

| Study design | Good | Fair | Poor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Controlled intervention study | 10–14 | 5–9 | 0–4 |

| Pre-post-study with no control | 9–12 | 5–8 | 0–4 |

| Observational cohort study | 10–14 | 5–9 | 0–4 |

| Case-series study | 7–9 | 4–6 | 0–3 |

In addition, the revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool (RoB 2) [43] was used to assess the risk of bias in the randomized controlled trials and identify specific domains that were at risk of bias. The analogous assessment tool for non-randomized studies, risk of bias in non-randomized studies-of interventions (ROBINS-I), could not be used because none of the non-randomized studies had a comparator intervention. Two authors (AM and MKJ) scored the RoB 2 items independently and described the study characteristics that supported their judgment for methodological quality; these descriptions were used for discussion when there were disagreements. The authors also checked the pre-specified analysis intentions for registered trials in Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ANZCTR). Because the purpose of the quality and risk-of-bias assessments was to critically evaluate the current literature available on the topic and describe the results, poor study quality was not considered to be an exclusion criterion.

Results

Search results

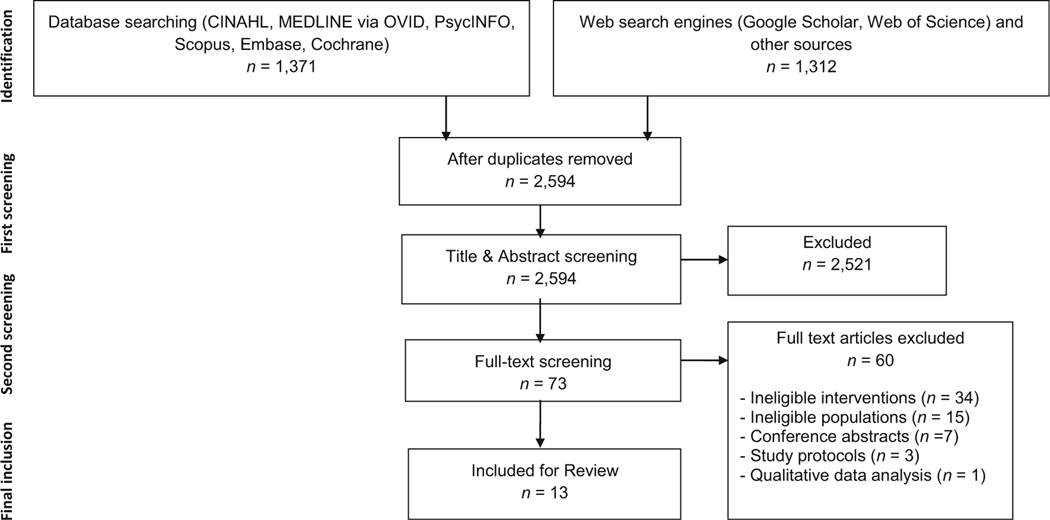

The systematic search identified 2683 articles, of which 73 were eligible for full-text screening. After full-text screening, 11articles were included for final synthesis. Two additional eligible studies were found through citation searching and grey literature search. Ancestry searching resulted in ineligible or redundant articles. The final number of articles was 13, including one dissertation. The PRISMA flowchart in Fig. 1 details the screening process.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart illustrating article selection process

Study and participant characteristics

The 13 articles selected for review were published between 2015 and 2019 from studies conducted in USA [44–46], Australia [47–52], Spain [53, 54], and Iran [55]. Of the 13 articles, 5 reported results from published randomized controlled trials [44, 48–50, 53]. A thesis done in Australia used randomized controlled cross-over design [Exploring the Effects of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on Biomarkers of Stress in Breast Cancer Survivors, Unpublished Honours dissertation, University of Southern Queensland, 9 November 2018]. Other study designs were quasi-experimental controlled trials [54, 55], single-arm pre-post-studies [45–47], a survey [51], and a case-series study [52]. Four articles were related to the same intervention (“ConquerFear” protocol): one reported the pilot testing of the intervention [47]; another reported the efficacy trial [48]; and the other two [49, 50] were secondary analyses of the efficacy trial. Thus the 13 included articles reported on 11 different research studies. Apart from reporting the findings of the secondary analyses articles, they are not included in other analyses (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies (n = 13)

| First author (year) | Country | Design and aim | Cancer type | Sample size | % sex | Mean age (SD) | ACT processes used | Outcomes (measures) | Intervention administered; evaluation time points; number of sessions (duration, frequency) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mohabbat-Bahar (2015) | Iran | Quasi-experimental-controlled trial: to examine effects of ACT on anxiety and depression | Breast | n = 30 | 100% female | 47.53 years (not reported) | Assessment of problems, abandonment of control, observation, mindfulness, values, commitment | - Anxiety (BAI) - Depression (BDI-II) |

- Group intervention - EG: ACT - CG: no intervention - Pre-post - Eight 90 min sessions over 4 weeks |

| Kangas (2015) | Australia | Case series: to examine effects of ACT on anxiety and depression, QoL, and sleep quality | Brain tumor | n = 4 | 75% female | 42 years (not reported) | Education about reactions to diagnosis of cancer, acceptance and mindfulness training for awareness and acceptance of cognitive and affective reactions, dealing with uncertainty, curtailing avoidance reactions, re-evaluating and reconnecting with value-based life goals, committing to pursue valued activities | - Depression (SCID-DSM-MDD), BDI-II - Anxiety (SCID-DSM-anxiety disorder), STAI-state and trait scales - Experiential avoidance (AAQ-9) - Quality of life (FACT-G total score, FACT-BT sub scale) - Additional stress since last assessment (dichotomous question) - Sleep quality (ratings from poor to excellent) - Expected benefits from program (1–10 scale) |

- Individual intervention - Single group: BT-ACT program - Pre-post-FU (1 month, 3 months) - Six 90 min sessions over 6 weeks, followed by two 90 min booster session every fortnight |

| Smith (2015) | Australia | Single-arm pre-post: to test feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of ConquerFear intervention for FCR | Breast (63%), other types (37%) | n = 8 | 100% female | 48 years (11.3) | Addressing existential issues, value clarification, goal setting, detached mindfulness | - Feasibility (0–10 scale, 4-point Likert scale) - Fear of cancer recurrence and its severity (FCRI) - Cancer-specific anxiety (IES Revised) - Quality of life (FACT-G) - Effectiveness of session (11-point scale) |

- Individual intervention - Single group: ConquerFear - Pre-post-FU (2 months) - Five 60 to 90 min sessions |

| Arch (2016) | USA | Single-arm pre-post: to pilot ACT intervention for anxiety at re-entry | Breast (59.52%), GI (14.29%), gynaecologic (9.52%), leukemia or lymphoma (7.14%), other types (9.52%) | n = 42 | 93% female | 53.52 years (11.05) | Cultivating awareness and acceptance of thoughts and emotions, disentanglement from rigid thoughts, cultivating flexibility, clarification of personal values, commitment to pursuing meaningful activities | - Anxiety (STAI, PHQ-4, 0–10 rating scale) - Depression (PHQ-4, CES-D) - Pain and vitality (RAND SF-36) - Fear of recurrence (CRS) - Cancer-related trauma symptoms (IES-R) - Life meaning, comprehensibility and manageability (OLQ) - Psychological flexibility (CAACQ) - Acceptability of each session (1–5 scale) |

- Group intervention - 3 baseline mid-intervention - Post-FU (3 months) - Weekly 2 h sessions over 7 weeks |

| Montesinos (2016) | Europe | Quasi-experimental-controlled trial: to assess effects of a specific component of ACT oriented to manage relapse fears, on distress and activity | Breast | n = 12 | 100% female | 49.4 years (14.3) | Assessment of satisfaction and value clarification, acceptance of thoughts as thoughts, defusion | - Emotional distress (HADS) - Anxious preoccupation (MINIMAC subscale) - Hypochondria (IBQ) - Fear of recurrence: intensity and interference of fear (1–10 scales) - Frequency of valued actions (1–5 scale) - Degree of satisfaction with the valuable actions (1–10 scale) - Degree of usefulness of exposure strategies (1–5 scale) - Difficulty to practice the strategies (1 – 5 scale) - Clinical significance analysis (20% drop in intensity and interference score; Cut-off points of HADS and IBQ) |

- Individual intervention - EG: ACT, CG: WL, no intervention - EG: pre-post-FU (1 and 3 months); CG: pre-FU (3 months) - Single 1 h session |

| Heiniger (2017) | Australia | Survey: to assess feasibility and acceptability of Web-based intervention (e-TC) | Testicular | n = 25 | 100% male | 37.6 years (8.0) | Acceptance of unpleasant thoughts and feelings, engage with challenging situations rather than avoiding them, defusion, mindfulness, connection, value identification, goal setting | Feasibility: - Proportion of e-TC completed (online distress and impact thermometers) - User engagement (no. of site logins, no. of pages viewed, session length) Acceptability: - Satisfaction with e-TC (11-point scale) |

- Online individual intervention - Single group: e-TC - Distress and impact at 0, 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100% completion of modules - Acceptability: at 10 weeks after end of module - 6 interactive modules over 10 weeks, each module takes approx. 1 h to complete |

| Butow (2017), Australia | RCT : to evaluate efficacy of ConquerFear in reducing FCR compared with non-specific attention control intervention, ‘Taking-it-Easy” | Breast (84%), colorectal (9%), melanoma (2%), missing (5%) | n = 222 | 95% female | 52.82 years (10.07) | Addressing existential issues, value clarification, goal setting, detached mindfulness | - Fear of cancer recurrence, its severity, triggers, coping strategies, and outcomes (FCRI) - Cancer-specific anxiety (IES Revised) - General distress (DASS21) - Quality of life ( AQ0L-8D) - Unmet information needs (information subscale of the Survivors Unmet Needs Survey) - Beliefs about worry or metacognitions (MCQ30) - Treatment credibility and expectancy (credibility/expectancy questionnaire) - Therapeutic alliance (WAI-SR) - Treatment satisfaction (1–9 single-item satisfaction scale) |

- Individual intervention - EG: ConquerFear - CG: Taking-it-Easy relaxation training - Pre-post-FU (3 and 6 months) - Five 60 to 90 min sessions over 10 weeks |

|

| Gonzalez-F emandez (2018) | Spain | RCT : to analyze efficacy of ACT and BA in treatment of emotional difficulties | Breast cancer (88.2%), other types (11.8%) | n = 52 | 92% female | 51.66 years (6.76) | Inverting experiential avoidance, inflexible attention, attachment to conceptualized self and cognitive fusion; focus on value connection and commitment to rewarding actions | - Anxiety and depression (HADS) - Quantity and availability of reinforcement from environment (EROS) - Experiential avoidance and psychological inflexibility (AAQ-II) - Activation, avoidance/rumination, work/school impairment, and social impairment (BADS) |

- Group intervention - EG1: ACT - EG2: BA - CG: no intervention (WL) - Pre-post - Weekly 90 min sessions over 12 weeks |

| Kinner (2018) | USA | Single-arm pre-post: to examine usability, feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary intended effects of Internet-based intervention (“Living WELL”) | Ovarian | n = 9 (for usability testing). n = 19 (for field trial) | 100% fe ma le |

59.2 years (14.53) (for usability testing); 58.89 years (6.87) (for field trial) | Increase awareness of distressing thoughts and feelings through acceptance and mindfulness, value identification, prioritization of meaningful activities | Usability: - Completion of common usage tasks including performing basic tablet functions, accessing the website, accessing the Website features and utilizing technical support, and amount of time taken by participants to learn and execute tasks) Acceptability: - User satisfaction (0–10 scale) Feasibility: - Study recruitment and study retention rates - No. of sessions attended, number of journal entries completed, and meditation/relaxation exercises completed) Preliminary outcomes: - Quality of life (FACT-O) - Stress (PSS) - Mood (CESD, PMS-SF) - Sleep quality (PSQI) - Social support (SPS) |

- Group intervention - Single group: ACT-hybrid intervention - Acceptability: after each session - Preliminary outcomes: pre-post - Weekly 1.5 to 2 h sessions over 10 weeks |

| Gardner (2018) | Australia | RCT (dissertation): to explore effects of ACT on stress biomarkers | Breast | n = 20 | 100% female | EG1, 57.86 years (7.48); EG2, 56.33 years (9.65); CG, 54.71 years (6.63) | Increasing effective action, orientation, mindfulness, self-context, formal value clarification, commitment | Physiological measures - Resting heart rate (fingertip pulse oximeter) - Blood pressure (Welch Allyn BP cuff, Hill-Rom sphygmomanometer) - Molecular biomarkers - Fasting blood glucose (Accu-Chek Performa) - Salivary alpha-amylase (saliva upon waking using Salivettes, IBL international enzymatic assay kit) - Salivary cortisol (saliva upon waking using Salivettes, Enzo Life Sciences ELISA kit) - Relative telomere length in PBMCs (Invitrogen Pure Link Genomic DNA Mini Kit, MMqPCR) - Inflammatory cytokine - Interleukin-6 (human IL-6 ELISA MAX™ Deluxe Set) - Allostatic load (ALI) |

- Group intervention - EG1 : ACT for 6 weeks - EG2: BCE for 6 weeks - Crossover of EG1 and EG2 after 6 weeks - CG: WL, no intervention for 6 weeks, then ACT for 6 weeks - Pre-post 1 (week 6)-post 2 (week 12)-FU (6 months) - Weekly 90 min sessions over 6 weeks for each intervention |

| Johns (2019) | USA | RCT: to assess the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of ACT for FCR, compared with SE and EUC | Breast | n = 91 | 100% female | 58.7 years (10.65) | Acceptance, cognitive defusion, mindfulness, aligning behavior with personal values | - Fear of cancer recurrence, triggers, psychological distress, functioning impairments, insight, reassurance seeking and coping strategies (FCRI-SF, respective FCRI sub scales) - Cancer-related avoidant coping (Cancer AAQ) - Distress (GAD, PHQ-8) - Post-traumatic stress (IES-Revised) - Physical and Mental QoL (PROMIS Global Health Scale) |

- Group intervention - EG1: ACT - CGI: SE - CG2: EUC - Pre-post-FU (1 and 6 months) - ACT and SE: weekly 2 h sessions over 6 weeks - EUC: single 30 min session |

| Sharpe (2019) | Australiaa | RCT : to identify mediators and moderators of treatment efficacy, through secondary analysis of ConquerFear trial data | Breast (84%), colorectal (9%), melanoma (2%), missing (5%) | n = 152 | 95% female | 52.82 years (10.07) | Addressing existential issues, value clarification, goal setting, detached mindfulness | - Fear of cancer recurrence, its severity, triggers, coping strategies and outcomes (FCRI) - Cancer-specific anxiety (IES Revised) - General distress (DASS21) - Quality of life (AQ0L-8D) - Unmet information needs (information subscale of the Survivors Unmet Needs Survey) - Beliefs about worry or metacognitions (MCQ30) - Treatment credibility and expectancy (credibility/expectancy questionnaire) - Therapeutic alliance (WAI-SR) - Treatment satisfaction (1–9 single-item satisfaction scale) |

- Individual intervention - EG: ConquerFear - CG: Taking-it-easy relaxation training - Pre-post-FU (3 and 6 months) - Five 60 to 90 min sessions over 10 weeks Moderators of FCRI total score at follow up = Baseline measures of FCRI total score, perceived likelihood of recurrence, intrusions and metacognitions Mediators of FCRI total score at follow up = perceived likelihood of recurrence, intrusions, therapeutic alliance and metacognitions |

| Shih (2019) | Australiaa | RCT: to assess costs associated with ConquerFear intervention and Taking-it-Easy control group, and compare net cost of the intervention with the control, in relation to the net benefits achieved | Breast (84%), colorectal (9%), melanoma (2%), missing (5%) | n = 222, 117 (for health care resource use) | 95% female | 52.82 years (10.07) | Addressing existential issues, value clarification, goal setting, detached mindfulness | - Cost utility analysis (Quality-adjusted life years = AQ0L-8D and Australian utility algorithm) - Cost-effectiveness analysis (FCRI score, ICER) - Intervention costs (records of activities and time spent for a representative sample of treated participants) - Broader health care resource use and impact on productivity (“My Cancer Care Cost Diary”) - All costs assessed in Australian Dollars at 2013 value |

- Individual intervention - EG: ConquerFear - CG: Taking-it-easy relaxation training - Pre-post-FU (3 and 6 months) - Five 60 to 90 min sessions over 10 weeks - Cost analyses: number of treatment session completed, payment made to therapists - Cost diary: Health professional visits, hospital admissions, medications, community service and other costs, days out-of-role, out-of-pocket expenses, time and travel costs |

Abbreviations: AAQ, Acceptance and Action Questionnaire; ALI, Allostatic Load Index; AQoL-8D, Quality of Life instrument; BA, Behavioral Activation; BADS, Behavioral Activation for Depression Scale; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BCE, Breast Cancer Education; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CAACQ, Cancer Acceptance and Action Cancer Questionnaire; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; CG, Comparison Group; CRS, Concerns about Recurrence scale; DASS, Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale; EG, Experimental Group; EROS, Environmental Reward Observation Scale; e-TC, online intervention for Testicular Cancer; EUC, Enhanced Usual Care; FACT- BT, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale-Brain Tumor; FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale—General; FACT-O, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale-Ovarian form; FCRI, Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory; FU, Follow Up; GAD, Generalized Anxiety Disorder; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IBQ, Illness Behaviour Questionnaire; ICER, Incremental Cost Effectiveness Ratio; IES-R, Revised Impact of Events Scale; MCQ 30, Meta Cognitions Questionnaire; Mid, Mid-intervention; MINIMAC, abridged version of Mental Adjustment to Cancer Scale; MMqPCR, Monochrome Multiplex real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction; OLQ, Orientation to Life Questionnaire; PHQ-4,4-item Patient Health Questionnaire for Anxiety and Depression; PMS-SF, Profile of Mood States-short form; Post, Post-treatment; Pre, Pre-treatment; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurements Information System; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; RAND SF-36, RAND Short Form 36-Item Health Survey; SCID-DSM-anxiety disorder(s), Structured Clinical Interview of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders-anxiety disorder(s); SCID-DSM- MDD, Structured Clinical Interview of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders—Major Depressive Disorder; SPS, Social Provisions Scale; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; SE, Survivorship Education; WAISR, Working Alliance Inventory; WL, Waiting List

Secondary analyses of Butow et al. (2017)

A total of 537 cancer survivors were enrolled in these 11 studies. The sample size ranged from 4 [52] to 222 [48]. The mean age of participants across the 11 studies was 50.6 years, ranging from 37.6 years [51] to 58.7 years [44]. Four studies exclusively included participants with clinically significant anxiety, depression, or FCR [44, 48, 52, 54]. Female cancer survivors were predominant, with six studies having only female participants [44, 45, 47, 54, 55] (unpublished thesis) and the others with percentage female ranging from 75% [52] to 95% [48]. Only one study included testicular cancer survivors [51]. Seven studies included only participants with a single type of cancer (breast cancer [44, 54, 55] (Gardner), ovarian cancer [45], brain tumor [52], or testicular cancer [51]), while the other four studies included participants with different types of cancer [46–48, 53]. Eight studies reported time since cancer diagnosis for the participants; the average time post-diagnosis was 36.45 months, with a range of 27 months [47] to 64.08 months [44]. One study reported the median time post-diagnosis as 28.25 months [48].

Quality assessment

The articles reporting secondary analyses [49, 50] were assessed for quality using the data from the primary study [48]. Among the included studies, two had a low risk of bias and received a good quality rating as per the NIH quality assessment tool [44, 48]. Both were randomized controlled trials, used intent-to-treat analyses, and contained explicit information required by the quality assessment tool. Another randomized controlled trial had high risk of bias due to lack of information on allocation sequence and to the effect of adhering to the intervention, and this study received a poor quality rating [53]. The quality assessment of the cross-over randomized controlled trial (unpublished thesis) included additional considerations recommended by the Cochrane RoB 2 [56]. It received a fair quality rating but had high risk of bias due to effect of assignment and adhering to intervention and missing outcome data. All the other studies received a fair quality rating.

Five studies had an overall dropout rate at endpoint of more than 20% [45, 47, 48, 51, 53]. Among these, four of the dropout rates ranged from 21.2% [53] to 37.5% [47], but the fifth study had a dropout rate of 64%, calculated based on the number of participants for the last online module [51]. All the included studies used valid and reliable measures to assess outcomes. However, some aspects of methodological quality were widely ignored; for example, only one article reported blinding of participants [44], while the others gave no information about whether the participants were aware of the study hypotheses. Some studies also did not employ adequate statistical approaches; only two studies reported use of intent-to-treat analyses [44, 48], and only one study [46] assessed the outcome measure multiple times before the intervention. Sample size justification or power description was reported for only two (18%) of the 11 studies [44, 48]. Furthermore, only about 45% of the studies reported checks to ensure the interventions were conducted in line with study protocol [44, 46, 48, 53, unpublished thesis]. Table 3 summarizes the risk-of-bias and quality assessment for each study.

Table 3.

Risk of bias assessment (RoB-2 tool) for RCT and Quality assessment (NIH tool) (n = 13)

| First author | Risk of bias arising from the randomization process | Risk of bias due to deviations from the intended interventions (effect of assignment to intervention, effect of adherence to intervention) | Missing outcome data | Risk of bias in measurement of the outcome | Risk of bias in selection of the reported result | Overall risk of bias | NIH quality assessment score (total score possible), interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Butow | L | L, L | L | L | L | Low | 11 (14), good |

| Gonzalez-Fernandez | H | S, H | S | L | L | High | 4 (14), poor |

| Gardner (dissertation) | S | H, H | H | L | L | High | 6 (14), fair |

| Sharpea | L | L, L | L | L | L | Low | 11 (14), good |

| Shiha | L | L, L | L | L | L | Low | 11 (14), good |

| Johns | L | L, L | L | L | L | Low | 12 (14), good |

| Bahar | 6 (14), fair | ||||||

| Kangas | 4 (9), fair | ||||||

| Smith | 5 (12), fair | ||||||

| Arch | 8 (12), fair | ||||||

| Montesinos | 5 (14), fair | ||||||

| Heiniger | 9 (14), fair | ||||||

| Kinner | 5 (12), fair |

H, high risk of bias; L, low risk of bias; S, some concerns; N, no information

Referred the primary study (Butow et al.) to perform quality assessment

Intervention characteristics

Intervention delivery settings

A hospital or clinic setting was the most common setting for intervention delivery (72.7%), followed by home (i.e., Web-based intervention) [45, 51] and community cancer care settings [46]. The intervention was administered in groups in about 55% of the studies, with each group consisting of 4–15 participants [44–46, 53, 55] (unpublished thesis). An active comparator was used in about 36% of the studies [44, 48, 53] (unpublished thesis). The comparator interventions included survivorship education or enhanced usual care [44]; a breast cancer education session [unpublished thesis]; a modified relaxation training program [48]; and behavioral activation [53]. Other details of interventions are shown in Table 2.

Core processes and mechanisms used

ACT processes were used exclusively in about 64% of the studies [44, 46, 52–55] (unpublished thesis). The other studies used ACT as a hybrid therapy, where the intervention involved both ACT and other therapies, such as CBT and relaxation [51], metacognitive therapy [47, 48, 51], cognitive-behavioral stress management and mindfulness-based stress reduction [45], and processes of the Common-Sense Model of illness and the Self-Regulatory Executive Function model [47, 48]. All studies reported use of the core ACT processes of acceptance, cognitive defusion, values, and committed action (Table 2).

The ACT protocols almost always involved exercises, metaphors, and experiential strategies; acceptance or mindfulness based or experiential exercises were used in about 82% of the included studies [44–48, 51–54]. However, only some studies described the themes and metaphors used in their intervention. These metaphors included “Passengers on the bus” [46], “Getting back on track” [51], “Garden” [54], and “Bad cup” and “Chessboard” [55]. Some studies contained information on measures taken to ensure consolidation of the skills learned during sessions. These measures included homework assignments or home-based practice and reading [44–48, 54] and handouts and CD with exercise [52].

Intervention personnel

Among the 7 studies that reported information about therapists, in about 86%, the intervention was delivered by clinical psychologists, psychiatrists, or oncology social workers [46–48, 52, 53] (unpublished thesis). Their clinical experience ranged from 5 to 10 years, with some additionally having at least 2 years of specific experience in oncology. In one study, the ACT sessions were led by doctoral-level providers trained in acceptance-based therapies [44]. Four studies explicitly mentioned that therapists received training on ACT and study-specific comparators [44, 47, 48] (unpublished thesis), and five studies reported measures to ensure adherence to study protocols [44, 46, 48, 53] (unpublished thesis). These measures included use of treatment manuals and strict protocols, fidelity ratings using session checklists, confirmation by audits of the recorded therapy sessions, and supervised sessions.

Participants’ comprehension and comfort

Only one study, one of the 2 studies that used a Web-based intervention, reported the efforts taken to ensure participants’ comfort with mode of delivery (i.e., the intervention Website and device operations) [45]. The study incorporated lab usability testing, comprising a 90-min hands-on session on using a Samsung Galaxy tablet, along with oral and written instructions. Apart from this, the study conducted field usability testing from the participants’ homes and obtained participants’ feedback regarding the technical experience.

Intervention dose, adherence, feasibility, acceptability, and satisfaction

One study delivered its intervention in a single session [54], while all other studies offered the intervention across multiple (5–12) sessions. Participants’ adherence to the intervention regimen was reported as attendance rates in about 55% of the studies [44–48, 51]. Strong evidence of feasibility and acceptability was reported, with high accrual and retention or enrollment rates [44, 45], high ratings for essentialness and effectiveness of the intervention [47], moderate to high ratings for usefulness or expected benefits from the intervention [48, 52, 54], and high degree of satisfaction with the sessions [45, 46, 48, 51] (see Table 4 for details).

Table 4.

Effect of ACT intervention on outcomes (n = 13)

| First author (sample size) | Anxiety, distress, stress, and depression | FCR | Psychological flexibility | Quality of life and other outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mohabbat-Bahar (30) | Between group: - Significant reduction in anxiety and depression at post-intervention (p < .05) |

|||

| Kangas (4) | -3 participants no longer met criteria for anxiety or depression (SCID-DSM) at post-intervention and 3 months post-intervention - Reduction in trait anxiety scores for 2 participants from pre- to 3 months post-intervention - Reduction in depressive symptom severity for all participants at post- and 1 month after intervention |

- Improvement in experiential avoidance for 3 participants at post-intervention and 1 month post-intervention | - Improvement in QoL for 3 participants at post-intervention and 1 month post-intervention - Improvement in sleep quality for 3 participants post-intervention and 1 month post-intervention - Expected benefits from program ranged from 6 to 10 across all time points |

|

| Smith (8) | - Significant reduction in cancer-specific anxiety at post-intervention (d = 0.6, p = 0.01) and 2 months post-intervention (d = 1.2, p = 0.01) | - Significant reduction in FCR total scores at post-intervention (d = 0.9, p = 0.002) and 2 months post-intervention (d = 1.8, p = 0.002) - Significant reduction in FCR severity at post-intervention (d = 1.0, p = 0.002) and 2 months post-intervention (d = 1.9, p = 0.002) |

- 100% uptake and retention rate - Mean participant ratings for essentialness of intervention was 8 and for effectiveness of intervention was 7.2 on a 0–10 scale |

|

| Arch (42) | - Significant reduction in anxiety at post-intervention (d = .75, p < .001) and 3 months post-intervention (d = 1.00, p <.001) - Significant reduction in depression at post-intervention (d = .78, p < .001) and 3 months post-intervention (d = .95, p <.001) - No significant change in anxiety or depression during the month-long baseline period |

- Significant reduction in FCR at post-intervention (d = 0.34, p < .05) and 3 months post-intervention (d = 0.66, p = .001) - No significant change in FCR during the month-long baseline period |

- Increases in cancer-related psychological flexibility partially mediated 8 outcomes; predicted (p < .05) subsequent changes in depression, pain, traumatic impact of cancer, vitality, life meaning and manageability and nearly predicted anxiety (p = .06) and life comprehensibility (p = .08) | - Significant reduction in physical pain at post-intervention (p = .05, d = 0.36) and 3 months post-intervention (p < .01, d = 0.54); and traumatic impact of cancer at post-intervention (p = .001, d = 0.58) and 3 months post-intervention (p < .001, d = 0.84) - Significant increase in vitality during multiple baseline points (p = .01, d = 0.29) at post-intervention (p = .001, d = 0.52) and 3 months post-intervention (p <.001, d = 0.77) - Significant increases in sense of life meaning at post-intervention (p < .001, d = 0.38) and 3 months post-intervention (p < .001, d = 0.49); life comprehensibility at post-intervention (p = .02, d = 0.32) and 3 months post-intervention (p < .001, d = 0.61); lifeman- ageability at post-intervention (p = .05, d = 0.21) and 3 months post-intervention (p = .003, d = 0.37) - Strong feasibility indicated by high attendance (median = 6) and high degree of satisfaction with sessions (M = 4.35, SD = .68)on 1–5 scale |

| Montesinos (15) | Within group: - Significant reduction in distress at 1 month post-intervention (d = 1.05, p = 0.027) - Significant reduction in anxious preoccupation at 3 months post-intervention (d = 0.82, p = 0.016) |

Within group: - Significant reduction in intensity of fear at 3 months post-intervention (d = 1.75, p = 0.017) - Significant reduction in interference due to fear at post-intervention (p = 0.043), 1 month (d = 2.43, p = 0.018) and 3 months post-intervention (d = 2.47, p = 0.012) - Between group - Significant reduction in intensity of fear at 3 months post-intervention (p = 0.048) - Significant reduction in interference due to fear at 3 months post-intervention (p = 0.008) |

||

| Clinical significance analysis: - Decrease in percentage of patients with clinically significant levels of anxious pre-occupation from 50% (pre-intervention) to 12% at 3 months post-intervention - Decrease in percentage of participants with clinical intensity in hypochondria from 62% (pre-intervention) to 37% (post-intervention) and at 3 months post-intervention - Decrease in percentage of participants with clinically significant emotional distress from 100% (pre-intervention) to 62% at post-intervention and to 50% at 3 months post-intervention - Decrease in percentage of participants with clinically significant levels of anxious pre-occupation from 50% (pre-intervention) to 12% at 3 months post-intervention |

Clinical significance analysis: - Clinically significant decrease in intensity of fear in 25% of participants at post-intervention and in 50% at 3 months post-intervention. - Clinically significant decrease in interference due to fear in 37% of participants at post intervention and in 87% at 3 months post-intervention. |

Clinical significance analysis: - Increase in frequency of valued actions at 3 months post-intervention at high level for 62% of the ACT participants and medium level for 37%. - Increase in satisfaction with valued actions in the presence of fear at 3 months post-intervention for 62% of the ACT participants - Utility of exposure strategies at 3 months post-intervention was high or medium for 87% - Difficulty of exposure strategies were medium or low for 100% at follow-up |

||

| Heiniger (25) | Feasibility: - 56% completed more than 80% of the intervention - 296 sessions were logged - Average time per session was 20 min - Average no. of pages viewed was 11 Acceptability: - Overall mean for all satisfaction outcomes ranged from 7.9 to 8.9 |

|||

| Butow (222) | Between group (versus TIE): - Improvement at post-intervention in general anxiety (p = .008), cancer-specific distress (p == .043), hyperarousal subscale of cancer-specific distress (p = .025); at 6 months post-intervention in cancer-specific distress (p = .028) and avoidance (p = .015). |

Intervention group (p < .001) and baseline FCR scores (p < .001) remained significant predictors of FCR at all time points. Between group (versus TIE): - Improved FCR at post intervention (d = 0.46, p < .001), 3 months (d = 0.33, p = .017) and 6 months post-intervention (d = 0.39, p = .018) FCR subscales: - Improvement at post-intervention in FCR severity (p < .001, coping (p = .008), psychological distress (p = .001), triggers (p = .007); at 3 months post-intervention in FCR severity (p = .023), psychological distress (p = .001), triggers (p = .042); at 6 months post-intervention in psychological distress (p = .002). Within group: - Improved FCR at post-intervention (d = 0.77, p < .001), 3 months (d = 1.0, p = .017) and 6 months post-intervention (d = 1.15, p = .018) |

Between group (versus TIE): - Improvement at post-intervention in mental dimensions of QoL (p = .001) and utility (p = .017). Between-group (versus TIE): - Improvement at post-intervention in metacognitions (p = .042) and need to control thoughts subscale (p = .004). - Significant increase in treatment expectancy scores (p = .007) and treatment alliance at post intervention - Similar treatment satisfaction and treatment credibility |

|

| Gonzalez-Fernandez (52) | Between group (versus BA): - No difference between slopes of ACT and BA Between group (versus CG): - Significantly larger differences between pre- and post-mean scores of anxiety (13.33 to 7.50) than control group (11.57 to 10.04) - Significantly larger differences between pre- and post-mean scores of depression (9.83 to 5.58) than control group (7.74 to 7.65) |

Between-group (versus BA): - Reduction in mean scores of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance (36.08 to 24.33); similar decrease in BA also - Significantly larger pre-post-decrease in avoidance/rumination (30 to 13) |

Between-group (versus BA): - Increase in mean scores of quantity and availability of reinforcement received from a survivor’s environment (21.58 to 28.67), Similar degree of increase in BA also - Significantly larger pre-post-decrease in social impairment (15.67 to 5.25) |

|

| Kinner (9 for usability testing, 19 for field trial) | - Significant reduction in perceived stress at post intervention (p = 0.03) - No significant decreases in depressive symptoms and negative mood states |

- Significant increase in ovarian cancer-specific QoL at post intervention (p = 0.01) - Significant increase in physical well-being at post intervention (p = 0.05) and functional well-being (p = 0.06) in ovarian cancer-specific QoL - No significant correlations between study activities and changes in ovarian cancer-specific QoL - No significant reduction in sleep quality and increases in social support - Usability: most tasks took less than 10 s to learn; 73% of participants made less than 2 errors. - Acceptability: high satisfaction with the session, (M = 9.0, SD = 0.74) and desire to return for the next session (M = 9.20, SD = 0.49) - Feasibility: 32% enrollment rate; 68% retention rate for field trial; overall attendance was 88.9% for participants who completed the intervention; average at-home relaxation and meditation practice was 2.78 times/week; average journal use was 2.34 times/week |

||

| Gardner (20) | Between group: - Significant reduction in cumulative allostatic load in WL group who attended ACT after 6 weeks wait but increase in groups 1 and 2 Within group: - No significant reduction in physiological and molecular biomarkers of stress - Significant correlations between pre-post mean heart rate (r = 0.670, d = −0.04, p = .003); mean SBP (r = 0.765, d = 0.33, p = .001); mean DBP (r = 0.631, d = 0.21, p = .009); mean salivary cortisol levels (r = 0.805, d = 0.22, p = .001); mean salivary amylase levels (r = 0.625, d = 0.13, p = .013); meanrela- tive telomere length (r = 0.728, d = 0.10, p = .002) |

|||

| Johns (91) | Between group (versus SE): - Improved generalized anxiety at 1 month (p < .05, d = 0.73) and 6 months post-intervention (p < .001, d = 0.95) - Improved distress at 6 months post-intervention (p <.05, d = 0.38) - Improved post-traumatic stress at 6 months post-intervention (p < .05, d = 0.41) (versus EUC): - Improved anxiety at 6 months post-intervention (p <.001, d = 0.75) - Improved distress at 6 months post-intervention (p <.05, d = 0.50) - Improved stress at 1 month post-intervention (p < .05, d = 0.80). Within group: - Improved anxiety at post intervention (LSM 2.36, p < .01), 1 month (LSM 3.04, p < .001), and 6 months post-intervention (LSM 3.25, p <.001) - Improved distress at post-intervention (LSM 1.55, p < .05), 1 month (LSM 1.77, p < .01), and 6 months post-intervention (LSM 1.72, p <.001) - Improved stress at post-intervention (LSM 5.34, p < .01), 1 month (LSM 7.96, p <.001), and 6 months post-intervention (LSM 7.91, p <.001) |

Between group (versus SE): - Improved FCR severity at post-intervention (p < .05, d = 0.68) and 6 months post-intervention (p < .001, d = 0.80) (versus EUC): Improved FCR severity at 6 months post-intervention (p <.01, d = 0.61). Within group: - Improved FCR severity at post intervention (LSM 4.03, p < .001), 1 month (LSM 4.06, p <.001), and 6 months post-intervention (LSM 5.04, p <.001) - Improvement in all subscales of FCRI across all time points except reassurance seeking and coping strategies |

Between-group (versus SE): - Improved avoidant coping at post-intervention (p < .05, d = 0.66), 1 month (p < .01, d = 0.83), and 6 months post-intervention (p < .001, d = 0.97) (versus EUC): - Improved avoidant coping at post-intervention (p < .05, d = 0.68) and 6-months post-intervention (p < .001, d = 0.80) Within group: - Improved avoidant coping at post-intervention (LSM 0.45, p < .001), 1 month (LSM 0.53, p <.001), and 6 months post-intervention (LSM 0.69, p <.001) |

Between-group (versus SE): - Improved physical QoL at post-intervention (p < .001, d = 0.72), 1-month (p < .001, d = 0.75) and 6-months post-intervention (p <.001, d = −0.62) - Improved mental QoL at post-intervention (p < .001, d = 0.68), 1 month (p < .001, d = 0.68), and 6 months post-intervention (p <.01, d = −0.52) Within group: Improved physical QoL at post-intervention (LSM 1.31, p < .001), 1 month (LSM 1.25, p <.001), and 6 months post-intervention (LSM 1.32, p <.001) - Improved mental QoL at post-intervention (LSM 1.36, p < .01), 1 month (LSM 1.43, p <.001), and 6 months post intervention (LSM 1.28, p <.001) - Strong evidence offeasibility with high accrual (43.8% of screened participants and 60.7% of eligible participants), attendance (81.7%) and retention (94.5%) rates |

| Sharpe (152) | - Baseline FCRI total score moderated the relative efficacy of intervention vs. comparator (F(15, 113), = 4.36, p = 0.039) - Significant indirect effect between treatment group and FCR total score, confirming partial mediation - Survivors with largest reductions in unhelpful metacognitions (β = −0.204, p = 0.008) and intrusions (β = −0.367, p < 0.001) predicted FCRI scores at follow-up |

- Intervention was significantly more efficacious than comparator for those scoring FCR one SD above the mean (p = 0.0005) and within one SD of the mean (p = 0.003) - Perceived risk of recurrence (F(6, 123) = 3.919; p = 0.053), metacognitions (F(6, 123) = 0.0701, p = 0.792) and intrusions (F(6, 123) = 2.152, p = 0.145) did not moderate efficacy of intervention - In mediation model, significantly greater reductions in unhelpful metacognitions (F(6, 136) = 2.337, p = 0.0353) and intrusions (F(6, 136) = 4.375, p = 0.0002) |

||

| Shih (222,117 for health care resource use) | - Average ICER was $85 per 1 unit FCR score reduction | - Average no. of therapy sessions received was 3.69 (95% CI, 3.43–3.96), with an average cost of $297 per participant - No significant group differences in session received and treatment costs - Average cost per person of health professional visits was $745 (95% CI, 452–1045), with no significant group differences in visits or healthcare costs at baseline - Average total health care costs was $4462, with no significant group differences - Between groups, interaction of time and treatment (QoL utility score) was significantly different in intervention group at post-intervention (p = 0.004) but not at follow-up points - Intervention had a mean ICER of $34,300/QALY which is less than the value-for-money threshold of$50,000/QALY |

BA, Behavioral Activation; CG, Comparison Group; CI, Confidence Interval; EUC, Enhanced Usual Care; FCR, Fear of Cancer Recurrence; FCRI, Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory; ICER, Incremental Cost Effectiveness Ratio; LSM, Least Squares Mean; QALY, Quality-Adjusted Life Year; QoL, Quality of Life; SCID-DSM; Structured Clinical Interview of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders; SD, Standard Deviation; SE, Survivorship Education; TIE, Taking-It-Easy; WL, Waiting List

Effect of intervention on outcomes

The effects of the ACT interventions on various clinical outcomes are summarized below. Table 4 shows the findings along with the within- and between-group differences in outcomes.

Psychological flexibility

Only four studies assessed the effect of intervention on psychological flexibility, which is characterized by reduction in experiential avoidance. Two studies reported significant reduction in avoidance in the intervention group, with the effect remaining at the 6-month follow-up [44, 46]. A third study, the case-series study, also reported improvement in experiential avoidance up to 1-month post-intervention; this study did not report statistical analyses due to its design [52]. A fourth study reported that increases in cancer-related psychological flexibility partially mediated eight other clinical outcomes [53]. However, in this study, a similar decrease in psychological inflexibility was observed in both ACT and the comparator groups.

Anxiety, distress, stress, and depression

Anxiety was assessed in about 64% of the studies, which reported significant improvements in anxiety post-intervention [44, 46–48, 53–55] and at follow-up periods of 2 [47], 3 [46, 54], and 6 months [44, 48]. Other outcomes related to anxiety, such as anxious pre-occupation and hypochondria, were also reported to be significantly decreased [54]. Significant improvements in distress were reported at post-intervention [44, 48] and at follow-up periods of 1 months [44, 54], 3 months [44, 48], and 6 months [44, 48]. Studies also reported significant improvements in depression at post-intervention [46, 53, 55] and at 3-month follow-up [46]. The case-series study also found improvements in anxiety and depression, but due to its study design did not report statistical analyses [52]. Two studies reported significant reduction in stress at post-intervention [44, 45] and at follow-up periods of 1 and 6 months [44], compared with baseline. The randomized controlled crossover trial reported that although there was no significant reduction in stress biomarkers, the allostatic load, a cumulative measure of stress, was significantly reduced among participants who were waitlisted and then received the ACT-based intervention (Gardner). Table 2 lists the instruments used to assess these psychological symptoms and Table 4 describes the details of the study findings.

Fear of cancer recurrence

FCR was another outcome that had significant reduction following an ACT-based intervention. These significant reductions were reported at post-intervention [44, 46–48, 54] and at follow-up periods of 1 months [44, 54], 2 months [47], 3 months [46, 48, 54], and 6 months [44, 48]. See Table 2 for instruments used to assess FCR.

Quality of life

Studies reported significant improvement in QoL following the ACT-based interventions, post-intervention [44, 45, 48], and at follow-up periods of 1 and 6 months [44]. The case-series study reported improvement in QoL scores without statistical analyses [52]. Table 2 shows the instruments used to assess QoL.

Other outcomes

Significant reduction in pain and cancer-related trauma symptoms and increases in vitality and sense of life meaning at post-intervention and 3 months follow-up were reported in one study [46]. The effect of ACT on sleep was unclear—with one study reporting no changes in sleep quality [45] while another suggesting improvements without statistical analyses [52]. Another outcome that significantly reduced was unhelpful metacognitions [48], which was also suggested as one of two likely mechanisms of treatment efficacy [49]. An analysis of cost-effectiveness of the intervention revealed an average cost of $297 per participant [50]. Only one study reported changes in ACT processes over time, reporting that at 3 months, 62% of the participants in the ACT group had high or very high increase in frequency of valued actions compared with pre-test and had increased their satisfaction with their actions in the presence of fear [54].

Discussion

This review is the first to provide a summary of evidence regarding the effects of ACT on symptoms among persons with cancer post-primary treatment. Despite comprehensive article search and retrieval efforts, only 13 articles fulfilled the inclusion criteria. All were published within the last 5 years, which supports an emerging evidence of use of ACT among cancer survivors. The most promising findings reported are improvements in anxiety, depression, FCR, and QoL. These findings, from among the first studies to be conducted exclusively among cancer survivors, add to the developing knowledge base regarding the use of non-pharmacological strategies for managing symptoms in survivorship.

The authors could not find any other published reviews of ACT among cancer survivors for comparison. However, when comparing findings of this review to those from a review of ACT among cancer patients, similarities were found in improvement of outcomes including anxiety, depression, emotional distress, QoL, and psychological flexibility [23]. The review findings are also largely supported by studies of ACT among populations without cancer. Systematic reviews of studies among individuals with clinical anxiety and depression have reported significant improvements in anxiety, with moderate to large effect sizes that last to an 18-month follow-up [57, 58]. Other studies similarly report significant improvement in anxiety and depression following ACT [59–65], with findings differing only when comparing the efficacy of ACT and CBT: one study found ACT to have better efficacy than CBT at the 12-month follow-up [60]; one found lesser clinically significant improvements for ACT than CBT [61]; and one found no differences between the two therapies [65]. These overall favorable findings strengthen investigators’ conclusion that ACT is useful post-completion of cancer treatment. In the light of significant symptom burden during survivorship, ACT has shown that it can engage individuals in accepting reality and committing to value-based action instead of employing avoidance strategies. A low level of preparedness for life post-primary treatment has been reported among survivors with high depressive symptoms [9]. Incorporating ACT interventions as part of comprehensive post-treatment survivorship care can enhance survivors’ psychological flexibility and reduce their experiences of anxiety, depression, and fear.

There are several other noteworthy findings from the review. While all the published studies used subjective measures of improvements in outcome, only the unpublished dissertation study focused on objective measures. For instance, published studies used validated self-report instruments to assess emotional states such as the Beck Anxiety Inventory, the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale, the Depression-Anxiety-and-Stress Scale, etc.; whereas, the dissertation examined effect of ACT on stress through changes in physiological and molecular biomarkers. Subjective measures such as self-report instruments have unique disadvantages where responses to items can be biased by social desirability or by the person’s feelings at the time they filled out the questionnaire. These subjective measures may hence under- or over-report the effect of a psychological intervention. In this context, objective measures such as biomarkers or other physiological measures, which are free of such bias, could provide more accurate intervention effect. Although physiological measures may prove to be more resource-intensive than administration of questionnaires, such objective measures add validity to the effect of a psychological intervention. In the review, although ACT was not found to result in significant reduction in stress biomarkers, the cumulative measure of stress (allostatic load) was significantly reduced in participants who received ACT after a waiting period [unpublished thesis]. In addition, this review identified evidence for the clinical significance of ACT in a study [54] which, despite the limitations of a small sample size, utilized criteria for clinically significant change in outcomes based on the authors’ clinical experience and cut-offs prescribed by standardized instruments. On the same note, this review also sheds light on how ACT affects cancer survivors with clinically diagnosed psychological symptoms at baseline. Four of the included studies recruited participants only if they had clinically significant anxiety, depression, or FCR, and all four reported significant improvements in outcomes. These findings have important implications for clinical care and strongly indicate that even cancer survivors with clinically significant anxiety, depression, or FCR could benefit from ACT.

Another important finding in this review was regarding the process of change involved in ACT. ACT uses six processes to affect outcomes through increase in psychological flexibility. Data on changes in these processes is scant. Four studies reported changes in psychological flexibility, and one study evaluated changes in ACT-related processes. All five of these studies observed an increase in psychological flexibility, which strengthen the knowledge base for ACT.

The methodological rigor of the included studies was fairly sound across the study designs, with some concerns about internal validity, including non-blinding of participants, non-random assignment, and inadequate statistical analyses. Since ACT is a behavioral intervention, blinding of therapists who provide the intervention is not feasible. Another concern is that the clinical outcomes were often participant-reported. In such cases, the assessment of outcome is potentially influenced by knowledge of the intervention received, which increases the risk of bias. A solution is to strengthen future study designs by ensuring that the participants and therapists are blinded to the study hypotheses. Using an active comparator intervention also reduces the potential risk of bias because participants may not have a prior belief that one of the active interventions is more beneficial than the other. Measures should also be taken to avoid deviations from the intended intervention and to treat participants according to fixed criteria that prevent administration of non-protocol interventions. Future studies should ensure that adherence to treatment protocol is ascertained by independent assessors in order to avoid potential conflict of interest and determine treatment effectiveness.

Although the overall results of this review are promising, it must be noted that the included studies focused mainly on four psychological symptoms, with many other symptoms common among cancer survivors, such as pain, sleep disturbances, and fatigue understudied. Also, the studies were heterogeneous in terms of data analysis and methodological rigor. This heterogeneity may be due to the fact that interest in ACT for cancer survivors has recently increased, and most of the studies were reporting preliminary findings or feasibility of an ACT-based intervention. Several of the studies reported changes in the expected direction but did not have adequate power due to insufficient sample size and lack of multivariate statistical analyses. Only six studies reported effect sizes, which are more robust indicators of improvement than significance values, especially in light of smaller sample sizes. And only six studies followed the participants beyond the post-intervention phase to assess the continued effect of ACT. Only four studies used active comparators, thus there must be caution in identifying factors responsible for the clinical change. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that two randomized controlled trials reported significant improvements, scored a good quality rating, and had a low risk of bias. Also, among the studies that reported average time since diagnosis, majority of them included survivors at around 3 years’ post-diagnosis, thus implying the effect of ACT during early stages of survivorship. Overall, considering the fact that research interest in ACT among cancer survivors is recent, these findings are promising and reiterate the importance of targeting anxiety, depression, and FCR at earlier stages of survivorship to potentially thwart chronic, clinically significant states of these negative symptoms and thereby improve QoL.

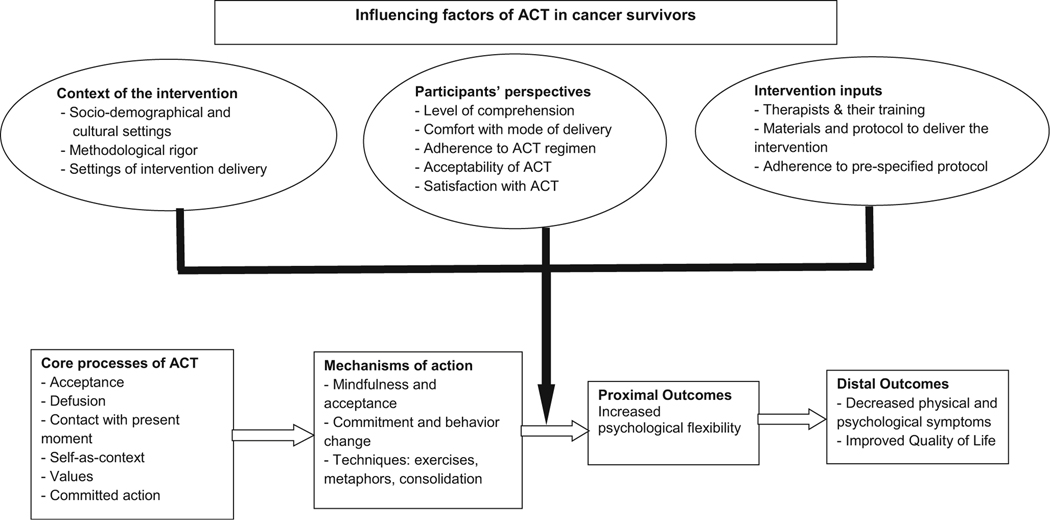

Proposed conceptual model for mechanisms of ACT in cancer survivors

Based on the review findings on characteristics of intervention and participants, the authors propose a conceptual model to describe the possible influencing factors of an ACT-based intervention in cancer survivors. These influencing factors, which need to be validated through further research, include the context of the intervention, intervention inputs, and the participants’ perspectives. As depicted in the original ACT model described by Hayes [19], ACT is defined in terms of its six core processes; it applies mindfulness and acceptance, and commitment and behavior change mechanisms to increase psychological flexibility. This outcome is achieved through the use of metaphors, experiential exercises, and consolidation techniques such as therapy work and homework linked to behavior change goals. With multiple components, ACT has a certain level of intervention complexity that needs to be considered. The authors propose that the context in which the core processes of ACT are delivered influences the intervention and its implementation. The important components of context are the sociodemographic and cultural settings of the participants, the methodological rigor, and the health care settings in which the intervention is delivered (e.g., clinic versus home; individual versus group intervention). Intervention inputs, such as the personnel who deliver the intervention and their training, the materials and protocols used for intervention delivery, and overall adherence to the protocol of ACT, also influence delivery of the intervention. Participant factors such as level of comprehension of ACT processes and required skills, level of comfort with the mode of intervention delivery, extent of adherence to ACT sessions and recommendations, and acceptance and satisfaction with ACT are important factors that are likely to influence the outcomes. The proximal outcome of ACT is increased psychological flexibility. The distal outcomes are decreased physical and psychological symptoms and improved QoL. Although the proposed model could be considered broadly for general population, it holds specific significance for cancer survivors. Compared with individuals receiving cancer treatment, the survivors are usually outside hospital settings. Delivery of ACT to cancer survivors would depend on their area of residence, strength of support system, and geographical availability of ACT-trained personnel and survivorship-services. Figure 2 illustrates the proposed conceptual framework.

Fig. 2.

Conceptual framework. Note: The ellipticals represent the various influencing factors, and the solid lines/arrow represent how these influence ACT. Boxes and hollow arrows represent ACT processes leading to desired outcomes

Recommendations and implications for future research

The authors are of the opinion that continued investigation into the effect of ACT on cancer survivors is needed, with special emphasis on methodological rigor. Well-powered randomized controlled trials, with active comparator groups and attention to intervention fidelity, will result in robust determination of intervention effectiveness. Because of the multiple processes involved in ACT and the importance of dose of a behavioral intervention, participants’ adherence and level of active engagement with the intervention needs to be considered and reported. This information may help distinguish between participants who merely receive the content and those who actively engage with it through diaries, practice of skills, and so forth. The authors also recommend assessing the effect of ACT among cancer survivors on the currently understudied outcomes, such as pain, sleep disturbances, and fatigue.

This review also points out a few important implications for future research. The influencing factors depicted in the proposed conceptual framework (see Fig. 2) need to be researched further to enable clinical decision making that helps therapists tailor an ACT intervention to participants’ expectations and needs. Another recommendation is to include clinical characteristics of participants who are cancer survivors, such as time since diagnosis and stage of cancer, in the data analyses, as these factors are very likely to influence subsequent physical and psychological symptoms. In addition, the effect of ACT on outcomes, including attenuation of biomarkers, could be researched for longer follow-up periods (e.g., 12 or 24 months) to obtain more accurate estimates of the strength and duration of the intervention effect. Further empirical support is also needed to determine the moderators of various clinical outcomes.

Finally, the authors recommend further investigation into intervention delivery. Since the individual face-to-face format can be both time and resource intensive, further studies of the efficacy of online group interventions are needed. These findings could benefit cancer survivors who find regular visits to a hospital setting difficult. Another important aspect that remains to be investigated is intervention delivery by health professionals other than trained therapists, such as delivery by nurses who have received required ACT training and supervision.

Limitations

This review has few limitations. This review includes only studies available in English. The findings from studies published in other languages could have further strengthened the analysis and might offer new avenues for research. A meta-analysis could not be performed due to the differing study designs and outcomes. Although this review was current at the time of submission, it is possible that additional studies on the subject have been published since the completion of this analysis. Nevertheless, this is the first review to report on ACT among cancer survivors, and its findings allow a precise evaluation of the current evidence in the ACT literature. In efforts to reduce potential publication bias, the review involves a comprehensive search in eight databases and six grey literature portals, apart from other search strategies. The authors have also used two quality assessment tools to critically analyze the rigor of the included studies.

Conclusions

Physical and psychological symptoms are common among cancer survivors post-primary treatment. To address this need will require appropriate allocations of personnel and other resources for symptom management. There is emerging evidence that ACT can improve these symptoms among cancer survivors specifically. Although past studies on the effect of ACT on each outcome are limited in number and contain certain methodological shortcomings, the reviewed studies report significant reductions in anxiety, depression, and FCR and improvements in QoL and psychological flexibility. Further investigation is required to determine the efficacy of ACT in reducing pain, fatigue, and insomnia and to evaluate the factors that influence the improvements in outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge health sciences librarian, Rebecca Raszewski, for her expertise and guidance regarding article search and retrieval strategies.

Funding

This article was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under award number #K24NR015340. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical approval This review is exempt from human subjects review.

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A.Cancerstatistics. CACancer J Clin. 2020;70(1):7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Yabroff KR, Alfano CM, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(5):363–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuhnt S, Brähler E, Faller H, Härter M, Keller M, Schulz H, et al. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in cancer patients. Psychother Psychosom. 2016;85(5):289–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng KKF, Devi DR, Wong WH, Koh C. Perceived symptoms and the supportive care needs of breast cancer survivors six months to five years post-treatment period. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2014;18(1): 3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang F, Liu J, Liu L, Wang F, Ma Z, Gao D, et al. The status and correlates of depression and anxiety among breast-cancer survivors in Eastern China: a population-based, cross-sectional case-control study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):326–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clevenger L, Schrepf A, Degeest K, Bender D, Goodheart M, Ahmed A, et al. Sleep disturbance, distress, and quality of life in ovarian cancer patients during the first year after diagnosis. Cancer. 2013;119(17):3234–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell AJ, Ferguson DW, Gill J, Paul J, Symonds P. Depression and anxiety in long-term cancer survivors compared with spouses and healthy control: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(8):721–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glare PA, Davies PS, Finlay E, Gulati A, Lemanne D, Moryl N, et al. Pain in cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(16):1739–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leach CR, Troeschel AN, Wiatrek D, Stanton AL, Diefenbach M, Stein KD, et al. Preparedness and cancer-related symptom management among cancer survivors in the first year post-treatment. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(4):587–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Savard J, Ivers H. The evolution of fear of cancer recurrence during the cancer care trajectory and its relationship with cancer characteristics. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74(4):354–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costanzo ES, Stawski RS, Ryff CD, Coe CL, Almeida DM. Cancer survivors’ responses to daily stressors: implications for quality of life. Health Psychol. 2012;31(3):360–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurita GP, Sjøgren P. Pain management in cancer survivorship. Acta Oncol. 2015;54(5):629–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zucca AC, Boyes AW, Linden W, Girgis A. All’s well that ends well? Quality of life and physical symptom clusters in long-term cancer survivors across cancer types. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2012;43(4):720–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Comprehensive Cancer Network(NCCN). NCCN guidelines for survivorship. Version 2.2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/survivorship.pdf. Accessed 15 Jan 2020.

- 15.Kwekkeboom KL, Cherwin CH, Lee JW, Wanta B. Mind-body treatments for the pain-fatigue-sleep disturbance symptom cluster in persons with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2010;39(1):126–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Syrjala KL, Jensen MP, Mendoza ME, Yi JC, Fisher HM, Keefe FJ. Psychological and behavioral approaches to cancer pain management. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(16):1703–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]