Introduction: TAU isoforms as disease mediators: The microtubule-associated protein TAU is predominantly present in the axons of neurons under physiological conditions. In Alzheimer's disease (AD) and related tauopathies, TAU also mislocalizes (“TAU missorting”) to the soma and the dendrites, where it eventually forms aggregates, the so-called neurofibrillary tangles (for review see Zimmer-Bensch and Zempel, 2021; Zempel, 2023). Alternative splicing of the TAU encoding MAPT gene results in eight major TAU isoforms, six of which are expressed in the human brain, while only three are present in the adult rodent brain (Goedert et al., 1989; Bullmann et al., 2009). The axodendritic distribution of the different TAU isoforms is strikingly different in neurons. The longest and least expressed (< 10% of the whole TAUom in the human central nervous system (CNS)) isoform of TAU, 2N4R-TAU, e.g., is partially retained in the somatodendritic compartment, where it induces enhanced dendritic outgrowth and spine maturation (Zempel et al., 2017; Bachmann et al., 2021). Amyloid-beta oligomers (AβO) induce pathological TAU missorting and the loss of dendritic spines, a sensitive measure of synaptic health and function. Interestingly, TAU depletion in mice, primary rodent neurons, and induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived human neurons protects them from AβO toxicity, spine loss, and consequential neuronal dysfunction (Roberson et al., 2007; Zempel et al., 2013; Buchholz et al., 2022).

Here, we present preliminary data of a study investigating AβO-mediated spine loss in primary rodent neurons, depending on the presence of different TAU isoforms. We show that reintroducing human 2N4R-TAU, but not the other rodent-specific CNS-isoforms of TAU (0N3R, 0N4R, and 1N4R), into Mapt knockout (= TAU KO) neurons resensitizes these neurons to AβO-induced spine loss. Further, we show that endogenous 2N4R-TAU is expressed only after 20–30 days in vitro (DIV) in primary rodent neurons and, in line with previous results, that 2N4R-TAU does not efficiently sort into the axon and is even mainly restricted to the somatodendritic compartment. Our results indicate that suppression of mature TAU isoforms, such as here 2N4R-TAU, in aged primary neurons via shRNA or a 2N-TAU specific antibody prevents AβO-induced spine loss. While preliminary and restricted to rodent cell culture experiments, this data adds to the observed differences in the axodendritic distribution of the different isoforms of TAU and hints towards a difference in their mediation of cellular stress in the context of AD. Here, we propose to differentially consider the individual TAU isoforms for future TAU-based therapeutic approaches for AD and related tauopathies.

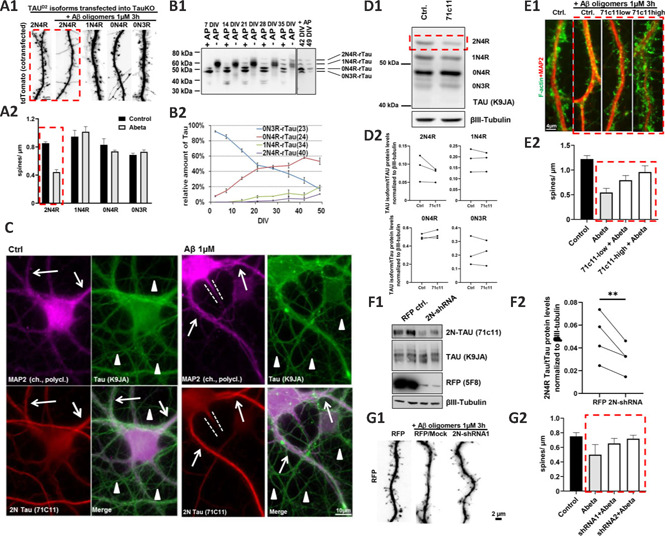

Preliminary results: 2N4R-TAU resensitizes TAU KO neurons to AβO-induced spine loss: TAU is essential for Aβ-induced neurotoxicity: Previous reports have already shown that TAU KO rodent neurons are resistant to Aβ-mediated toxicity (Roberson et al., 2007; Zempel et al., 2013). However, little is known about the contribution of the different TAU isoforms to synapse loss after Aβ insult. To study the influence of the different TAU isoforms on Aβ-mediated spine loss, human Dendra2c (D2)-tagged TAU isoforms were re-expressed in mature primary neuronal cultures (DIV16, prepared E16.5) from Mapt knockout mice, as described previously (Zempel et al., 2017). To assess spine density, tdTomato was co-expressed as a volume marker. Afterwards, neurons were exposed to 1 µM Aβ7:3 oligomers (as prepared before (Zempel et al., 2013, 2017)) for 3 hours. Interestingly, significant (~50%) AβO-mediated spine loss was only observed in neurons expressing human 2N4R-TAU, but not the other three TAU isoforms typically present in rodent neurons, namely 1N4R, 0N4R and 0N3R (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

2N4R-TAU is necessary and sufficient for AβO-induced spine loss in primary neurons.

(A) Reintroduction of different TAU isoforms into primary murine TAU-KO neurons after the establishment of neuronal cell polarity and spine formation (days in vitro (DIV) 15). Different isoforms of human Dendra2c-tagged TAU (TAUD2) were co-transfected with tdTomato (as volume marker) for five days, afterwards, cells were treated with 1 µM AβO for 3 hours. (A1) Fluorescence microscopy of the volume marker tdTomato shows a reduction of dendritic spines after transfection with 2N4R-TAU followed by AβO treatment, but not in other conditions. Scale bar: 4 µm. (A2) Quantification of A1. n = 5–10 dendrites, at least 5 cells were analyzed per condition. (B) Time course of endogenous TAU isoform expression of rat primary neurons between DIV2 and DIV49. (B1) Western blot of rat cortical neurons grown for the indicated time points. Samples were left untreated (-AP) or treated with alkaline phosphatase (+AP) for dephosphorylation. (B2) Quantification of B1. Only after 3 weeks of culture, the longest rodent TAU isoform (2N4R-TAU) is detectable, while the shortest rodent TAU isoform (0N3R-TAU) steadily decreases until the end of the analysis. Note that until three weeks in vitro, 0N3R-TAU constitutes the majority of the TAU protein in cultured neurons. n = 3–4 independent cultures. (C) Immunofluorescence images of mature primary rat neurons (DIV35) after vehicle control and AβO treatment. Neurons were stained for 2N-TAU (71C11), the dendritic marker MAP2, and an antibody recognizing all TAU isoforms (K9JA). Neurons express solid levels of 2N4R-TAU in the soma and dendrites (indicated by arrows) but not in the axons (indicated by arrowheads). The dotted lines indicate axon hillock. Treatment with AβO results in an increased signal of 2N-TAU in the dendrites. (D–E) 2N4R-TAU can be suppressed by 2N-TAU specific antibody (71C11, incubation for 4–5 days) in rat cortical neurons, which prevents AβO-induced spine loss. (D1) Western blot with a panTAU antibody (K9JA) of dephosphorylated TAU of mature rat primary neurons (35 DIV) shows that 2N4R-TAU is decreased after exposure to 71C11 (1:600 dilution) for 4–5 days. βIII-tubulin was used as a loading control. (D2) Quantification of individual TAU isoform expression in D1. n = 3 independent cultures. (E1) (Immuno-) Fluorescence images of mature primary neurons (DIV35) incubated with 71C11 as indicated. Neurons were treated with either vehicle control or AβO for 3 hours and afterwards stained for F-actin as an indicator for dendritic spines and MAP2 as a dendrite marker. While neurons treated with AβO show pronounced loss of spines, this is largely prevented by pre-incubation of cells with 71C11 (red dotted box). (E2) Quantification of spine density after knockdown of 2N-TAU by 71C11 and treatment with vehicle control or 1 µM AβO. n = 5–10 dendrites of different cells. (F–G) AdV-based shRNA-mediated knockdown of 2N4R-TAU prevents AβO-induces spine loss in rat primary neurons. (F1) Western blot with 2N-TAU specific (71C11) and panTAU antibody (K9JA) of dephosphorylated TAU of mature primary neurons (35 DIV) after transduction with AdV-RFP or AdV-2N-TAU shRNA for 3–4 days. 2N4R-TAU expression is decreased after AdV-mediated KD. βIII-tubulin was used as a loading control. (F2) Quantification of F1. Expression in primary rat neurons after transduction with AdV-2N-TAU shRNA. n = 4 independent cultures. (G1) Immunofluorescence images of mature primary neurons (DIV35) after AdV-transduction and AβO treatment as indicated. Transduced cells express RFP, which is used as a volume marker to visualize spines. While control neurons treated with AβO show pronounced loss of spines, this is largely prevented by KD of 2N4R-TAU. (G2) Quantification of G1. Spine density after KD of 2N-TAU by shRNA and treatment with vehicle control or 1 µM AβO. n = 5–10 dendrites of different cells. Error bars represent SEM. Statistical analysis was performed by t-test with Tukey's test for correction of multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Arrows indicate dendrites; arrowheads indicate axons; red dotted lines highlight important findings; white dotted lines indicate axon hillocks. Paired analysis was done to compare the treated vs. untreated cultures, due to high differences between individual cultures. Unpublished data by our team. AdV: Adenovirus; AP: alkaline phosphatase; AβO: amyloid beta oligomers; DIV: days in vitro; KD: knockdown; TAUD2: Dendra2c-tagged TAU.

Since TAU isoform expression in rodents differs strongly from human TAU expression (Goedert et al., 1989; Bullmann et al., 2009), we next monitored TAU isoform expression in primary neurons from wild type rats by western blot analysis of neuronal cell lysates for 49 days (Figure 1B). In line with previous reports from mice (Bullmann et al., 2009), only 0N isoforms were detectable in young neurons (DIV2), with 0N3R as the major isoform expressed (> 90%; Figure 1B). Upon neuronal maturation, 0N3R expression decreased at a constant rate until it reached a proportion of ~20% of all isoforms in old neurons (DIV49). In contrast, 0N4R expression constantly increased until it reached an expression level of ~50% at DIV49. In addition, expression of both 2N4R and 1N4R isoforms increased from DIV7, finally reaching 15% and 20% of all isoforms at DIV49, respectively. Especially the expression levels of 2N4R, 1N4R, and 0N3R, ranging between 15–20%, resemble the isoform expression reported by Trabzuni et al. (2012) for the human brain. All in all, these results suggest that rat primary neurons are rather suitable for the analysis of TAU isoforms if to be compared to the human brain, and considering that in the murine brain – in contrast to humans – up to 45% of 2N4R-TAU is expressed (Bullmann et al., 2009).

Recent studies suggest a sub-cellular difference in the human TAU isoform localization, and especially human 2N-TAU isoforms are retained in the somatodendritic compartment of wild type primary neurons (Zempel et al., 2017; Bachmann et al., 2021). Endogenous 2N-TAU localization was assessed in rat primary neurons by immunofluorescence staining with a 2N-TAU specific antibody (71C11; Figure 1C). Note that, as 2N3R-TAU is not expressed in our primary neurons (Figure 1B) and other rodents (Bullmann et al., 2009), this antibody here exclusively marks 2N4R-TAU. Total TAU was stained by a polyclonal TAU antibody (K9JA), recognizing all isoforms of TAU, while MAP2 was used as a dendritic marker as described before (Zempel et al., 2017). We found that primary rat neurons showed solid staining for 2N-TAU only present in the soma and dendrites of the cells, in line with our previous findings (Zempel et al., 2017; Bachmann et al., 2021). All in all, 2N4R-TAU is retained from axonal sorting, and as dendritic TAU has been shown to drive spine loss and neuronal dysfunction (Zempel and Mandelkow, 2014), 2N4R-TAU could be a driver of Aβ-induced spine loss observed in rodent neurons.

Downregulation of endogenous 2N4R-TAU prevents AβO-induced spine loss: Next, we aimed to suppress endogenous TAU in our primary neuron cultures. In a first attempt, primary rat neurons were incubated with a 2N-TAU specific antibody (71C11) for 4–5 days. TAU isoform levels were assessed by western blot assay under dephosphorylating conditions. 2N4R-TAU levels, but none of the other isoforms of TAU, were suppressed after incubation with 71C11 antibody compared to untreated controls (Figure 1D) in all three cultures. This hints towards antibody-mediated suppression of TAU isoforms (here, due to the absence of 2N3R TAU, specifically 2N4R TAU) in neurons being possible. In the next step, to test whether 2N4R suppression may be beneficial in a disease context, the spine density of neurons after treatment with AβOs was analyzed in dependence on antibody-mediated 2N-TAU suppression. 2N4R-TAU was suppressed by two different concentrations of 71C11 (hereafter referred to as 71C11-low (1:600) and 71C11-high (1:300)), resulting in lower or stronger 2N4R repression, respectively (Figure 1E). In line with previous reports (Zempel et al., 2013) and with our results above, AβO-treatment resulted in dendritic spine loss that was prevented by the suppression of 2N4R-TAU in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1E). To further validate a potential beneficial effect of 2N4R-TAU, we next downregulated 2N4R-TAU by RNAi. For this, an adenovirus (AdV)-delivered shRNA construct was generated that specifically targets rat 2N-TAU isoforms (Figure 1F and G). AdV-mediated delivery resulted in significant knockdown of 2N4R-TAU (but not the other three detectable TAU isoforms) in our rat primary neurons, as analyzed by western blot assay (Figure 1F). These results indicate that RNAi-based knockdown of 2N-TAU isoforms is suitable to suppress 2N4R-TAU in rat primary neurons selectively, due to the absence of 2N3R-TAU. Analysis of spine density after knockdown of endogenous rat 2N4R-TAU and subsequent AβO treatment again showed a noticeably increased spine density compared to AβO treated and mock-transduced neurons (Figure 1G), which confirmed that, indeed, 2N4R-TAU may mediate AβO-induced spine loss. Our results indicate that the 2N4R-TAU isoform may specifically mediate acute AβO-induced spine loss.

Discussion and perspective: While preliminary and restricted to rodent primary neurons, we show here that the 2N4R-TAU isoform may specifically mediate Aβ-induced neurotoxicity. First, we investigated the effect of human TAU isoforms on TAU KO neurons in an AD paradigm. TAU KO mice and derived neurons are resistant to Aβ-mediated cognitive impairment and spine loss (Roberson 2007; Zempel et al., 2013). Here, re-expression of the human 2N4R isoform exclusively resensitized the neurons to Aβ-induced synaptotoxicity, indicating that 2N4R-TAU may significantly contribute to AD-like or Aβ-mediated TAU-based synaptotoxicity.

While rodents express only four TAU isoforms, namely 2N4R, 1N4R, 0N4R, and 0N3R, humans express two additional isoforms, 2N3R and 1N3R (Trabzuni et al., 2012) in the CNS. Compared to human neurons, which only express ~10% 2N4R-TAU, mice express up to ~45% (Bullmann et al., 2009; Trabzuni et al., 2012). Here, we identified that late maturation stages of rat primary forebrain neurons show a human-like ratio of 2N4R-TAU vs. total TAU. Also, 1N4R- and 0N3R-TAU expression levels were comparable to the human brain. Hence, we reason that rat primary forebrain neurons are an acceptable model system to study the 2N4R-TAU isoform, particularly the effect of its suppression. Of note, an antibody specific to 2N-TAU is suitable for studying 2N4R-TAU specifically since rat primary neurons do not express 2N3R-TAU. While this is a technical advantage, as otherwise specifically targeting 2N4R-TAU protein/mRNA (without affecting 2N3R-TAU would be challenging), it is naturally a clear limitation of this study, as one cannot exclude significant effects of the isoforms simply not expressed in rodents. Nonetheless, using a 2N-TAU specific antibody for immunofluorescence microscopy, we observed that already in physiological conditions, 2N4R-TAU was retained in the soma and dendrites of rat neurons, underlining the differential intracellular sorting of TAU isoforms reported earlier (Zempel et al., 2017; Bachmann et al., 2021). As reported previously, treatment with AβOs resulted in missorting of total TAU (Zempel et al., 2013; Buchholz et al., 2022) but not in a reduction of 2N4R-TAU in the somatodendritic compartment and invasion of 2N4R-TAU into the axon hillock. Due to its dendritic presence both in our AD-like model and already under physiological conditions, these results hint towards 2N4R-TAU to be of critical importance for (post-)synaptic TAU toxicity.

Next, we used antibody-mediated and AdV-based shRNA delivery to suppress 2N4R in mature neurons and investigate its role in AD-like Aβ-mediated neurotoxicity. While there was no effect on total TAU or neuronal health observable in physiological conditions, in AD-like conditions (after exposure to AβOs), suppression of 2N4R-TAU resulted in noticeable prevention of AβO-induced spine loss, a sensitive measure of synaptic dysfunction. While in adult rodent neurons, only 4R-TAU isoforms are expressed, we cannot exclude that due to the additional expression of 3R-TAU in mature human neurons of the CNS, additional isoforms may be involved in the pathological cascade observed in AD patients. Nevertheless, as previously demonstrated in rodent tauopathy models and derived primary neurons, the presence and amount of 4R-TAU isoforms in these models are sufficient to drive neuronal dysfunction and neurodegeneration in disease paradigms. Recent results obtained from human iPSC-derived neurons re-expressing individual human TAU isoforms identified the human 1N4R isoform as a mediator of TAU toxicity induced by AβOs (Buchholz et al., 2022). However, it is difficult to compare these results with the results obtained here, due to the differences in experimental design (endogenous vs. overexpressed and tagged exogenous TAU, isolated isoform approach vs. all rodent-specific TAU isoforms present, hiPSC-derived neurons vs. primary rodent neurons). Of note, a comprehensive study recently compared the interactome of murine and human TAU and found remarkable differences between the two species even though the MAPT sequence is highly conserved.

Both, 2N4R and 1N4R TAU, are mature TAU isoforms present in rodents and previous interactome studies of murine TAU isoforms found already differences in the interactions of the individual isoforms and especially correlated 2N4R-TAU with neurodegenerative processes (Liu et al., 2016, for review see Stancu et al., 2019). In addition, is it likely, that due to differences in the N-terminal domains, the interactome of the 2N4R and 1N4R isoforms differs within a species and between species, leading to a different response to AβO-induced neuronal toxicity. Therefore, we should consider individual TAU isoforms when studying neurodegenerative diseases characterized by TAU pathology.

Identifying the toxic isoform of TAU in disease conditions may be of major importance, as complete knockout of TAU was shown to have some adverse effects, e.g., aged TAU KO mice having small nonpathological deficits in muscle function, changes in sleep/awake behavior and fear conditioning, and reduced long-term potentiation (Lopes et al., 2016). In humans, MAPT/TAU haploinsufficiency is associated with severe neurodevelopmental delay (as part of a microdeletion syndrome usually not restricted to MAPT-deletion). Nevertheless, several TAU-reducing drugs are currently in different stages of clinical investigation. Our results, however, indicate that it might be sufficient and beneficial to target one (mature) isoform specifically to reduce or even prevent the synaptotoxicity mediated by TAU and to ameliorate potential side effects of total TAU reduction. While we did not observe any negative effects of the 2N4R-TAU based suppression, this still needs careful investigation. In particular 2N4R-TAU expression resulted in dendrite extension and development of mature spine morphology (see e.g. Zempel, 2017). While TAU-KO mice, derived neurons and also our human iPSC-derived TAU-KO neurons may be able to compensate for the absence of TAU e.g. by increasing the expression of other MAPs or changing their splicing, this cannot be taken for granted in settings of acute suppression in a mature organism. As such, future studies aiming at single isoform suppression of TAU should now take into consideration that synapse function may be affected in a subtle fashion, in particular when mature isoforms of TAU are suppressed for therapeutic purposes. We also note that so far 2N4R-TAU suppression did not change the overall behavior of total TAU, when investigated using a pan-TAU antibody. This is logical, as the majority of TAU in our system here is made up of other isoforms, which may still be mislocalized in pathological settings, e.g. as done here by exposure to AD-like AβOs. However, due to our experience with pulse-chase and immunofluorescence-based analysis of the different TAU isoforms, we can certainly postulate that the different isoforms of TAU may also show differential susceptibility to cellular or AD-like stress.

In summary, we show here and have shown earlier (Zempel et al., 2013) that the TAU isoform 2N4R alone is likely sufficient to mediate AD-like neurotoxicity in rodent primary neurons and that in subtle stress conditions, 2N4R-TAU may even be necessary for AD-like neurotoxicity. Therefore, we propose considering the TAU isoforms when developing future TAU-based therapies for AD and related dementia syndromes.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Else-Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung (to HZ).

Additional file: Open peer review report 1 (90.9KB, pdf) .

Footnotes

Open peer reviewer: Maxwell Eisenbaum, Roskamp Institute, USA.

P-Reviewer: Eisenbaum M; C-Editors: Zhao M, Liu WJ, Qiu Y; T-Editor: Jia Y

References

- Bachmann S, Bell M, Klimek J, Zempel H. Differential effects of the six human TAU isoforms: somatic retention of 2N-TAU and increased microtubule number induced by 4R-TAU. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:643115. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.643115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz S, Bell-Simons M, Kabbani MAA, Kluge L, Cagkmak C, Klimek J, Zempel H. The TAU isoform 1N4R restores vulnerability of MAPT knockout human iPSC-derived neurons to amyloid beta-induced neuronal dysfunction. Res Sq. 2022 doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-2277268/v1. [Google Scholar]

- Bullmann T, Holzer M, Mori H, Arendt T. Pattern of tau isoforms expression during development in vivo. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2009;27:591–597. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Jakes R, Rutherford D, Crowther RA. Multiple isoforms of human microtubule-associated protein tau: sequences and localization in neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 1989;3:519–526. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90210-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Song X, Nisbet R, Götz J. Co-immunoprecipitation with Tau Isoform-specific Antibodies Reveals Distinct Protein Interactions and Highlights a Putative Role for 2N Tau in Disease. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:8173–8188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.641902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes S, Lopes A, Pinto V, Guimarães MR, Sardinha VM, Duarte-Silva S, Pinheiro S, Pizarro J, Oliveira JF, Sousa N, Leite-Almeida H, Sotiropoulos I. Absence of Tau triggers age-dependent sciatic nerve morphofunctional deficits and motor impairment. Aging Cell. 2016;15:208–216. doi: 10.1111/acel.12391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson ED, Scearce-Levie K, Palop JJ, Yan F, Cheng IH, Wu T, Gerstein H, Yu GQ, Mucke L. Reducing endogenous Tau ameliorates amyloid ß-induced deficits in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Science. 2007;316:750–754. doi: 10.1126/science.1141736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stancu IC, Ferraiolo M, Terwel D, Dewachter I. Tau interacting proteins: gaining insight into the roles of Tau in health and disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1184:145–166. doi: 10.1007/978-981-32-9358-8_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trabzuni D, Wray S, Vandrovcova J, Ramasamy A, Walker R, Smith C, Luk C, Gibbs JR, Dillman A, Hernandez DG, Arepalli S, Singleton AB, Cookson MR, Pittman AM, de Silva R, Weale ME, Hardy J, Ryten M. MAPT expression and splicing is differentially regulated by brain region: relation to genotype and implication for tauopathies. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:4094–4103. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zempel H, Luedtke J, Kumar Y, Biernat J, Dawson H, Mandelkow E, Mandelkow EM. Amyloid-β oligomers induce synaptic damage via Tau-dependent microtubule severing by TTLL6 and spastin. EMBO J. 2013;32:2920–2937. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zempel H, Dennissen FJA, Kumar Y, Luedtke J, Biernat J, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E. Axodendritic sorting and pathological missorting of Tau are isoform-specific and determined by axon initial segment architecture. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:12192–12207. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.784702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zempel H. Genetic and sporadic forms of tauopathies—TAU as a disease driver for the majority of patients but the minority of tauopathies. Cytoskeleton. 2023 doi: 10.1002/cm.21793. doi: 10.1002/cm.21793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Bensch G, Zempel H. DNA methylation in genetic and sporadic forms of neurodegeneration: Lessons from alzheimers, related Tauopathies and genetic tauopathies. Cells. 2021;10:3064. doi: 10.3390/cells10113064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.