Abstract

Alzheimer's disease, among the most common neurodegenerative disorders, is characterized by progressive cognitive impairment. At present, the Alzheimer's disease main risk remains genetic risks, but major environmental factors are increasingly shown to impact Alzheimer's disease development and progression. Microglia, the most important brain immune cells, play a central role in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis and are considered environmental and lifestyle “sensors.” Factors like environmental pollution and modern lifestyles (e.g., chronic stress, poor dietary habits, sleep, and circadian rhythm disorders) can cause neuroinflammatory responses that lead to cognitive impairment via microglial functioning and phenotypic regulation. However, the specific mechanisms underlying interactions among these factors and microglia in Alzheimer's disease are unclear. Herein, we: discuss the biological effects of air pollution, chronic stress, gut microbiota, sleep patterns, physical exercise, cigarette smoking, and caffeine consumption on microglia; consider how unhealthy lifestyle factors influence individual susceptibility to Alzheimer's disease; and present the neuroprotective effects of a healthy lifestyle. Toward intervening and controlling these environmental risk factors at an early Alzheimer's disease stage, understanding the role of microglia in Alzheimer's disease development, and targeting strategies to target microglia, could be essential to future Alzheimer's disease treatments.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, chronic stress, environmental factor, gut microbiota, microglia, particulate matter with diameter < 2.5 µm

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD), the most common cause of dementia, is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by memory loss and progressive cognitive impairment (Leng and Edison, 2021). Other clinical AD symptoms include language dysfunction, visuospatial difficulties, and personality changes, which seriously reduce patient quality of life and cause heavy social burdens (Holtzman et al., 2011). According to Alzheimer's Disease International, globally, 75% of patients with dementia are undiagnosed, and in some low- and middle-income countries, this proportion may be as high as 90%. With their latest data, the World Health Organization estimated that in 2019, 55 million people suffered from dementia; this number is expected to rise to 139 million by 2050 (No authors listed, 2023). Primary AD pathology includes brain amyloid plaque depositions, which are formed by amyloid-β (Aβ) aggregation and neurofibrillary tangles triggered by tau hyperphosphorylation (Villemagne et al., 2013; Rickman et al., 2022; Roda et al., 2022).

Microglia, brain myeloid cells, act as the first-line immune protection in brain injury and disease (Estudillo et al., 2023). In the 1990s, Caudros et al. first suggested that microglia originate from the yolk sac during primitive hematopoiesis and fill the central nervous system (CNS) before vasculogenesis (Cuadros et al., 1993). From a morphological perspective, microglia are classified as ramified (resting), activated, or ameboid (phagocytotic). Increasing evidence indicates that microglia present a diverse range of phenotype states during chronic inflammation, which are categorized as: proinflammatory M1 and activated M2 (Orihuela et al., 2016; Ransohoff, 2016). However, the M1/M2 dichotomy is criticized as an oversimplification that cannot model in vivo conditions (Hansen et al., 2018). Current investigators increasingly stress the importance of studying various microglial phenotypes due to the complex process of microglial activation, and have revealed several new microglial phenotypes associated with AD. These include dark microglia, which are abundant in AD pathology, chronic unpredictable stress, and ageing (Bisht et al., 2016); disease-associated microglia (DAM), which re observed in AD and localized near Aβ plaques (Keren-Shaul et al., 2017); microglial neurodegenerative phenotype, which are isolated from the brain and spinal cord of amyloid precursor protein (APP)-PS1 mice (Bisht et al., 2018); activated response microglia, which are enriched with AD risk genes (Sala Frigerio et al., 2019); and human Alzheimer's microglia (Srinivasan et al., 2020). Clearly, microglia are likely key participants in AD.

AD is a chronic disease influenced by both the external environment and genetics. The latter play an important role in AD development (Silva et al., 2019). Gene mutations such as APP or PS1 can directly lead to familial AD. There is consensus that the ε4 allele of the apolipoprotein E gene (APOE4) is the most significant genetic risk factor for sporadic AD (Martens et al., 2022). In addition, during AD development, microglia acquire an AD signature; for example, many AD risk genes are highly enriched in microglia, some of which are exclusively expressed in microglia. These include apolipoprotein E (APOE), triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2), ATP binding cassette subfamily A member 7 (ABCA7), complement C3b/C4b receptor 1 (CR1), Spi-1 proto-oncogene (SPI1), and MS4A-related family (MS4As) (Bertram et al., 2008; Efthymiou and Goate, 2017), highlighting the important role of microglia in sporadic AD.

In addition to these important genetic risk factors, environmental risk also plays a role that should not be underestimated. Up to one-third of patients with AD may be affected by modifiable risk factors (Livingston et al., 2017). Environmental factors may affect microglia, and microglia may in turn affect an individual's susceptibility to AD, as microglial dysfunction is a major risk factor for AD (Bisht et al., 2018; Katsumoto et al., 2018; Phan and Malkani, 2019). Stress during both perinatal and adult development can lead to microglial function changes, which in turn affect cognitive function (Tay et al., 2017). Specifically, particulate matter (PM) with diameter < 2.5 µm (PM2.5) can reach the CNS through various routes and there activate microglia to cause inflammation and nerve damage, leading to AD (Shi et al., 2020). Dietary factors can modulate gut microbiota composition, and the gut microbiota may be associated with AD pathogenesis by altering microglial function (Bairamian et al., 2022). Circadian rhythm disturbance and other poor lifestyle factors cause microglia neurodegeneration (Phan and Malkani, 2019). While neither genetic risk factors nor environmental exposures affect AD alone, together they may interact to promote AD progression; however, those interactions are poorly understood (Dunn et al., 2019). Almost all environmental exposures described herein may interact with the APOE genotype, and thus affect cognitive function (Rajan et al., 2021).

Herein, we discuss the impacts of environmental risk factors (e.g., air pollution) and modern lifestyles (e.g., chronic stress, poor eating habits and circadian rhythm disturbance, inadequate physical exercise) on AD pathogenesis and progression, by contributing to pathogenic microglial phenotypes and modulating their functions. These cumulative findings support the idea that microglial dysfunction is a central mechanism of AD development and pathology progression. The positive roles of healthy environment and lifestyle factors are discussed in relation to reducing individual susceptibility to AD, and their modulation of microglial function is considered as a potential future therapeutic modality.

Retrieval Strategy

An online PubMed search was performed, retrieving articles published through August 31, 2023. Combined MeSH terms were used to maximize search specificity and sensitivity: “Alzheimer's disease”; “microglia”; “environmental pollution”; “chronic stress”; “gut microbiota”; “PM2.5”; “heavy metals”; “sleep”; “smoking”; “physical exercise,” and “coffee.” The results were further screened by title and abstract, and only studies exploring the interplay between microglia and environmental AD risk factors were included, to facilitate the goal of reviewing the effects of environmental risk factors on microglia characteristics in AD. No language or study type restrictions were applied.

Environmental Exposure Contributions to Alzheimer's Disease Risk

Air pollution

Air pollution, a complex mixture of substances, is a global environmental problem that kills 7 million people annually worldwide (Colao et al., 2016). Air pollution contains PM, ozone, nitrogen dioxide, and other substances. Among these, the most harmful to our health is ambient fine particulate matter PM2.5 (Choi et al., 2018). There is a strong link between PM2.5 and cognitive dysfunction, including AD (Thiankhaw et al., 2022). Studies have also verified how PM2.5 enters the CNS, including via both the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and olfactory neurons (Ajmani et al., 2016). The BBB is a highly selective semipermeable membrane that restricts the flow of many substances into the brain and plays an important role in maintaining CNS homeostasis (Alahmari, 2021). In animal models, PM-mediated tight junction protein expression leads to reduced BBB integrity and increased permeability (Oppenheim et al., 2013). In addition, the olfactory nerve is considered a critical pathway by which PM2.5 affects the CNS (Li et al., 2022). Rodent models have confirmed that PM can access the brain via the nose (Elder et al., 2006). Considerable PM parts can be deposited in the nasopharyngeal region, to be translocated further into multiple brain regions, circumventing the tight BBB (Oberdorster et al., 2004). By entering the CNS through these two main pathways, PM2.5 exposure increases AD risk. However, the exact mechanism and causal relations between PM2.5 and AD remain unclear, requiring further research.

PM2.5 exposure

Investigators increasingly show that long-term PM2.5 exposure higher than that specified by United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) standards may be related to cognitive decline and accelerated brain ageing (Kang et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2021; Patten et al., 2021). Observational studies in children (Calderon-Garciduenas et al., 2015), older adults (Ailshire and Crimmins, 2014), and dogs (Calderon-Garciduenas et al., 2008b) living in areas with higher PM2.5 concentrations have indicated that this prolonged exposure can induce neuroinflammation, increase AD risk, and accelerate AD pathogenesis. Some of the AD-linked molecular and cellular alterations caused by PM2.5 include mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, microglial activation, neuroinflammation, synaptic dysfunction, and neurovascular dysfunction (Gonzalez-Maciel et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2020a). PM2.5 can also alter major AD markers, including elevated levels of Aβ accumulation, tau hyperphosphorylation, and misfolded α-synuclein (Cheng et al., 2016; Costa et al., 2017).

Current clinical studies have shown a clear correlation between environmental air pollution and AD pathology, based on three methods: biomarkers, neuroimaging, and epigenetics. The first line of evidence has shown that in the cerebrospinal fluid of children and young people living long-term in areas where annual average PM2.5 concentrations exceed the US EPA standard level long-term, Aβ and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) are reduced, and tau protein, inflammation, and cytokine marker concentrations are increased (Calderon-Garciduenas et al., 2018). The second line of evidence indicates that patients with mild dementia or MCI who live in areas with higher PM2.5 concentrations have a higher likelihood of amyloid PET scan positivity (Iaccarino et al., 2021). The third line of evidence indicates close relations between low deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) methylation and AD in both epidemiological and experimental studies (Bakulski et al., 2012; Chouliaras et al., 2013; Wei et al., 2020). Researchers have speculated that PM2.5 can reduce genome-wide DNA methylation or global hypomethylation, including of BACE1, APOE, and APP (Shou et al., 2019). In summary, effects of PM2.5 on AD can be detected by cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers, DNA methylation levels, and amyloid deposition on PET scans.

PM2.5-promoted microglial activation

Since microglia-mediated neuroinflammation is a detrimental AD event, researchers have assessed whether and how PM2.5 affects microglia function. Previous research used diesel exhaust particles (DEPs) phagocytosed by microglia to produce superoxide, showing that selective dopaminergic neurotoxicity occurred only in the presence of microglia, indicating that microglia-derived reactive oxygen species (ROS) are crucial for DEP-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity (Block et al., 2004). This finding supported the idea that DEPs are culpable in microglial activation (Block et al., 2004). Moreover, prolonged exposure to high levels of air pollution leads to increased expressions of CD14 (Calderon-Garciduenas et al., 2008a) and the microglial marker Iba1 (Bai et al., 2019), indicating that microglia may be the main targets of air pollution.

An in vitro experiment showed that DEP exposure affected microglia in various ways, including cytotoxicity, oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation, neuroinflammation, activation, autophagy, and apoptosis (Bai et al., 2019). PM2.5 significantly increased the level of light-chain 3b (LC3b) in microglia, resulting in a DAM microglia phenotype representing enhanced phagocytosis (Kang et al., 2021). A recent study suggested that PM2.5 decreases microglial viability and promotes microglial activation. Specifically, PM2.5 increased the introduction of proinflammatory molecular markers (i.e., tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α], interleukin-6 [IL-6], interleukin 1 beta [IL-1β], inducible nitric oxide synthase [iNOS], and COX-2) while inhibiting the development of anti-inflammatory molecular markers (IL-10 and Arg-1) (Kim et al., 2020). These data further indicate that PM2.5 mediates AD pathogenesis through microglia-produced neuroinflammation and oxidative stress. PM2.5 is now widely studied as a cause of neuroinflammation. Exposure to PM2.5 decreases the activity of several antioxidant enzymes that scavenge cellular free radicals and protect cells, including superoxide dismutase, malondialdehyde, heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), and GSH-Px, while increasing brain ROS (Herr et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2023). One mechanistic study showed that PM2.5 can downregulate miR-574-5p, which targets BACE1 through nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) p65, thereby causing neuroinflammation, disrupting synaptic functional integrity, and accelerating cognitive dysfunction (Ku et al., 2017). Another mechanistic study showed that PM2.5 exposure activates the microglial HMGB1-NLRP3-P2X7R signaling pathway and reduces hippocampal neuron viability. That group also found that HMGB1-NLRP3 pathway downregulation inhibited microglial activation, decreased inflammatory factor production, and restored hippocampal neurons functioning (Deng et al., 2022).

Thought various opinions exist regarding how PM2.5 accelerates AD via microglia, and no consensus has formed. PM2.5 may thus directly or indirectly activate microglia through three ways. First, by directly activating microglia. Second, by activating proinflammatory signals in peripheral tissues or organs, including the liver (Jeong et al., 2019), lung (Jia et al., 2021) and cardiovascular system (Wang et al., 2015), eliciting a circulating cytokine response (Ruckerl et al., 2007) which activates microglia and causes neuroinflammation (Block and Calderon-Garciduenas, 2009). And third, by directly damaging neurons to activate microglia (Liu et al., 2021). However, given the complexity of PM2.5 exposure, it is unclear whether it activates microglia through one of these modalities or in combination among them in AD pathological conditions. The evidence for the influences of PM exposure on microglia are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of known instances of PM exposure that influence microglia

| PM | Models | Effects | Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| PM2.5 | BV-2 cell; primary cortical neurons and glia isolated from the cerebral cortex of E17 Sprague-Dawley rats | PM2.5 increases transcription of pro-inflammatory M1 and disease-associated microglia phenotype molecules, and induces pJNK activation, exacerbating neuronal damage. | Kim et al., 2020 |

| PM2.5 | Primary microglia | PM2.5 exposure increased oligomeric amyloid-beta stimulated reactive oxygen species levels in microglia, inducing interleukin-1β production and activation of NLRP3 inflammasome, and leading to neuronal damage. | Wang et al., 2018a |

| nPM | N2a-APP/swe cells | nPM exposure increased amyloid-β oligomers, causing selective atrophy of hippocampal CA1 neurites. | Cacciottolo et al., 2017 |

| PM2.5 | PM2.5-polluted human brain models | PM2.5 exposure triggered M1 microglia phenotype, which released additional proinflammatory mediators and nitric oxide, exacerbating synaptic damage, phosphorylated tau accumulation, and neuronal death. | Kang et al., 2021 |

| PM2.5 | BALB/c mice; BV2 microglia | Compound essential oils relieved brain oxidative stress, caused by PM2.5 exposure, by inhibiting autophagy through the 5'-adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway. | Ren et al., 2021 |

| DEP | Adult female Fisher 344 rats; female mice; primary microglia and neurons | DEP selectively damaged dopamine neurons through phagocytic activation of microglial NADPH oxidase, causing oxidative insult. | Block et al., 2004 |

| Carbon black; DEPs | BV-2 cells; Sprague-Dawley rats | Traffic-related particulate matter induced: cytotoxicity, lipid peroxidation, microglial activation, and inflammation; microglia autophagy and caspase-3 regulation. | Bai et al., 2019 |

| PM2.5 | Mice | PM2.5 exposure activated high mobility group box 1-NOD-like receptor thermal protein domain associated protein 3-P2X purinoceptor7 signaling pathway in microglia, reducing hippocampal neuron activity. | Deng et al., 2022 |

| PM2.5 | C57BL/6J mice | Short-term PM2.5 administration via atomization or nasal drops activated astrocytes and microglia. | Liang et al., 2023 |

DEP: Diesel exhaust particles; nPM: nanosized particulate matter; PM2.5: particulate matter with diameter < 2.5 µm.

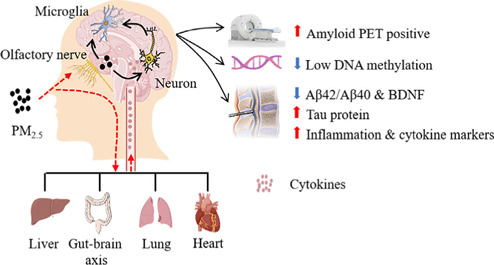

To date, animal model experiments, epidemiological studies, and clinical studies have confirmed a causal link between ambient air pollution and AD pathology. The underlying mechanism for this may be that PM2.5 activates microglia via one or more of the three pathways described above, thereby inducing neuroinflammation and oxidative stress and leading to AD biomarker changes (Figure 1). In addition to microglia, PM2.5 can also act directly on other neural cells. We previously reported that PM2.5 can cause direct neuronal damage under very short-term exposure, whereas microglia did not play a major role (Liang et al., 2023). However, changes in microglia in AD under long-term exposure to PM2.5 require further exploration.

Figure 1.

Possible mechanisms by which microglia detect PM2.5 and some AD-related neuropathologic consequences of this exposure.

Microglia detect PM2.5 entering the brain via the nasal route. These particles can directly damage neurons, activating microglia and causing cytokine release via the peripheral systemic inflammatory system through the respiratory tract and activated microglia. AD biomarkers changes from PM2.5 exposure include: 1) high amyloid PET scan positivity; 2) low DNA methylation; 3) cerebrospinal fluid (reduced Aβ42, Aβ40, and BDNF; increased t-tau, p-tau, and inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α). Created with Adobe Illustrator CS6. AD: Alzheimer's disease; Aβ: amyloid-β; BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; DNA: deoxyribonucleic acid; IL-1β: interleukin-1β; IL-6: interleukin-6; PET: positron emission tomography; PM2.5: particulate matter (PM) with diameter < 2.5 µm; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor.

Heavy metals: powerful AD risk factors

Among environmental factors, the contributions of heavy metals such as lead (Pb), cadmium, and manganese to AD is of interest, given the wide range of their population-level exposures. The effects of various common heavy metals on AD have been well studied (Plascencia-Villa and Perry, 2021). For example, childhood Pb exposure has been shown to lead to memory loss and cognitive decline in older age (Reuben et al., 2017). In vitro studies have shown that Pb exposure increases the water content of tau in SH-SY5Y cells (Bihaqi et al., 2017). Different metals, such as Pb, arsenic, and cadmium, may induce Aβ production to the greatest extent through synergistic effects (Ashok et al., 2015). However, whether the respective mechanisms are the same is still poorly understood (Islam et al., 2022). Some metal chelators, such as hydroxypyridones, can interfere with protein folding and prevent its undergoing oxidative processes (Singh et al., 2019). Therefore, metal chelator studies may facilitate development of novel anti-AD agents as potential therapies (Fasae et al., 2021). In summary, adverse environmental factors lead to the phenotype of pathogenic microglia and regulate their function, thereby increasing individuals' susceptibility to AD.

Stress

Though stress is an inevitable part of life, it can also endanger human health under certain conditions. Given constantly changing, fast-paced modern lifestyles, stress is a frequent conversation topic (McEwen, 2005). Stress is divided into acute and chronic. The effects of acute stress can be quickly alleviated, after which the condition normalizes. However, chronic stress, such as long-term emotional stress, results in homeostatic dysregulation that can lead to various diseases, especially in susceptible individuals (Saeedi and Rashidy-Pour, 2021). These include, but are not limited to, mental illness (Menard et al., 2017), cardiovascular diseases (Franklin et al., 2021), gastrointestinal disorders (Alonso et al., 2008), and neurodegenerative diseases (Sazonova et al., 2021). Though stress can increase the occurrence, and worsen the symptoms, of AD, the most common neurodegenerative disease, the mechanism for this relation is as yet unclear.

Stress and cognitive decline: epidemiology and pathology evidence

Growing evidence recognizes chronic psychosocial stress as a risk factor for late-onset AD, and a strong contributor to promoting AD brain pathology (Gracia-Garcia et al., 2015; Piirainen et al., 2017). Epidemiological, clinical, and animal studies suggest that chronic uncontrollable and unpredictable stressors are associated with mental illnesses, including depression and neurodegenerative disorders like AD (Liu et al., 2017). Epidemiological studies have found that depression is an AD risk factor, and that people who are prone to psychological stress are at higher risk for AD (Wilson et al., 2003; Alkadhi, 2012). Chronic psychosocial stress is increasingly considered a risk factor for late-onset AD and its related cognitive impairment (Saeedi and Rashidy-Pour, 2021). Compared with healthy age-matched controls, patients with AD present increased peripheral and CNS cortisol levels, reflecting a relation between stress and AD (Popp et al., 2015). In animal experiments, acute stress (i.e., acute cold water stress) (Feng et al., 2005), acute unpredictable stress (Filipcik et al., 2012) and chronic stress (i.e., chronic restraint stress) (Yan et al., 2010), and chronic unpredictable mild stress (Briones et al., 2012) all increase tau phosphorylation. Similar to the consequences of tau phosphorylation, female 5×FAD mice exposed to chronic restraint stress in the prepathological stage exhibited elevated BACE1 and APP levels, increased neurotoxic Aβ42 levels, and hippocampal plaque deposition (Devi et al., 2010; Ray et al., 2011). It has been demonstrated that chronic stress can promote the emergence of AD and accelerate its progression through synaptic loss and impaired neurogenesis (Xie et al., 2021). For example, social isolation accelerated AD onset and spatial working memory impairment in adult APP/PS1 transgenic mice (Huang et al., 2011). Overall, these studies suggest that stress can exacerbate and accelerate AD progression.

Effects of stress on microglia: a double-edged sword?

Although the mechanism is not yet clear, microglia are suspected to play a significant role in promoting AD development and progression under chronic stress. Chronic stress may activate microglia, induce inflammation, and worsen cognitive function in the adult brain (Piirainen et al., 2017). In the hippocampus of stressed rats, Iba1 and CD11b protein levels were significantly increased compared with those of non-stressed control rats; thus, chronic mild stress induced microglial proliferation in the hippocampus (Du Preez et al., 2021). Chronic stress also selectively increases the density of microglia in certain stress-sensitive brain regions, such as the prelimbic cortex (Han et al., 2020), medial prefrontal cortex (Bollinger et al., 2016), and hippocampal CA3 region (Bian et al., 2012). Quantification of microglia from mice subjected to restraint stress indicate that augmented density is caused by proliferation (Nair and Bonneau, 2006). Although these studies imply that chronic stress can stimulate microglial proliferation, the mechanism of action is poorly understood. In a Chinese herbal medicine study, chronic stress modulated microglia toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-I-kappa B kinase-NF-κB signaling pathway, promoting the release of inflammatory factors from hippocampal microglia and leading to neuroinflammation (Qu et al., 2021). Nrf2-HO-1-NLRP3 signaling was inhibited in microglia exposed to stress using Nrf2 siRNA transfection, thereby promoting microglial polarization to M1 and inhibiting microglial polarization to M2 (Tao et al., 2021). More mechanisms are under investigation, the discovery of which will facilitate new AD therapeutics.

One urgent question is whether chronic stress alters microglial morphology. As it is tightly coupled to its function, using different stress models had led to varying results. Chronic stress causes a marked transition of microglia from a ramified-resting state to a non-resting state. A primary microglial morphological change observed in the chronic stress paradigm is a hyperramification state, with longer and more branched processes (Hinwood et al., 2013; Hellwig et al., 2016). This suggests that chronic stress increases microglial structural complexity but does not make them larger. Another main microglial change is cellular deramification, with increased soma size and shortened processes (Kreisel et al., 2014; Wohleb et al., 2014). However, Lehmann and colleagues found that neither acute nor chronic social defeat stress changed microglial morphology, including cell perimeter length, cell spread, eccentricity, roundness, or soma size (Lehmann et al., 2016). These cumulative results indicate that there is currently no consensus regarding the effects of stress on microglial morphology.

In the mature healthy brain, microglia remove cellular debris and necrotic or apoptotic cells through phagocytosis. Several investigators have investigated whether exposure to stress modulates the phagocytic function of microglia. Milior et al. (2016) exposed mice to a chronic stressor and examined hippocampal CA1 radiatum with electron microscopy, to assess the number of phagocytic inclusions per Iba1-positive microglial process. They found that exposure to stressful (versus control) environments increased the microglial inclusion index. Similarly, enhanced microglial phagocytic capacity was found in Thy-1-GFP transgenic mice subjected to a 14-day chronic unpredictable stress (CUS) model (Wohleb et al., 2018). These results indicate that CUS increases the microglial phagocytosis of neuronal components. Lehmann et al. (2016) also replicated this phenomenon with chronic, but not acute social defeat. Thus, stress may induce neuronal remodeling by enhancing microglial phagocytic function.

In recent decades, efforts have been made to determine how stresses alter microglia activity of (Frank et al., 2019; Woodburn et al., 2021). Although the specific signaling pathways by which stress activates microglia are unclear (Wohleb et al., 2016), a growing body of evidence implicates several factors, such as cytokines, pattern recognition receptor agonists, and stress hormones. First, exposure to stressors releases pathogen-associated and danger-associated molecular patterns into the bloodstream, which can trigger microglia and amplify neuroinflammatory responses (Wenzel et al., 2020). Second, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis plays an important role in stress-induced microglial activation (Frank et al., 2012). Stress can initiate proinflammatory responses in microglia by activating the HPA axis, releasing more corticotropin-releasing hormone and glucocorticoids (GCs) (Van den Bergh et al., 2020). GCs are a suspected link between chronic stress and altered microglial structure and function. Moreover, both pharmacological (glucocorticoid receptor [GR] antagonist RU486) and surgical (adrenalectomy) treatments block stress-induced microglial priming (Frank et al., 2012) and reduce markers of phagocytosis on petrified microglia following CUS (Pedrazzoli et al., 2019). These cumulative studies demonstrate that GCs may play a pivotal role in stress-induced priming of microglial activation. Although the mechanism of cognitive impairment caused by chronic stress is unclear, several GR-regulated genes are closely related to AD. First, expression of GR-regulated gene Dusp1, which phosphorylates tau kinase, is decreased during chronic stress, leading to tau hyperphosphorylation. DUSP1 expression is also decreased in the brains of AD mice compared with age-matched controls (Arango-Lievano et al., 2016). Another GR-regulated gene, Sgk1, a key modifier of tau pathology in AD, is upregulated in the brains of participants with AD. Sgk1 inhibition reduces tau neuropathology and improves cognition in preclinical AD mouse models (Elahi et al., 2021).

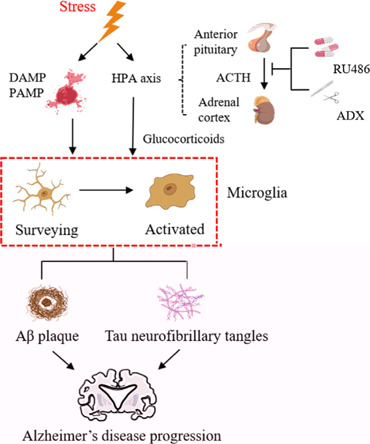

Chronic stress is a modifiable AD risk factor. This relation may be caused by HPA axis dysregulation and other molecular mechanisms, which can lead to a series of microglial changes. Under chronic stress, elevated GC levels prompt microglial proliferation and enhance their phagocytic ability, though there is no uniform conclusion regarding the morphological effects. These changes allow microglia to undergo a notably increased proinflammatory response, leading to increased neurotoxic cytokines, accumulating Aβ, and tau. These combined factors may accelerate AD onset (Figure 2). Determining the underlying mechanism of the association between chronic stress and AD may help develop new therapeutic targets and chronic stress management options.

Figure 2.

Microglia as stress response sensors.

Stress induces a series of alterations in microglial morphology, function, and immunophenotype through stress hormones/transmitters. These changes allow microglia to undergo a markedly increased proinflammatory response, leading to increased levels of neurotoxic cytokines and accumulating Aβ and neurofibrillary tangles. These combined factors may accelerate AD onset. Created with Adobe Illustrator CS6. ACTH: Adrenocorticotropic hormone; ADX: adrenalectomy; Aβ: amyloid-β; DAMP: danger-associated molecular patterns; HPA: hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal; PAMP: pathogen-associated molecular patterns; RU486: glucocorticoid receptor GR antagonist.

Gut Microbiota

There is a close homology among animals, including humans, in their microbial communities, which are comprised of fungi, archaea, bacteria, and viruses. Gut microbiota, which make up the gastrointestinal community, represents the greatest density and absolute abundance of microorganisms in the human body. Throughout the human life span, the gut microbiota is a dynamic, diverse community that may change in response to both extrinsic and host factors, such as drugs (Vich Vila et al., 2020), diet (David et al., 2014), age, and sex (de la Cuesta-Zuluaga et al., 2019). The microbiota-gut-brain axis, a complex bidirectional communication system between the brain and gut microbiota, is mediated by direct and indirect signaling, including nervous, endocrine, and immune mechanisms (Martin et al., 2018). The gut microbiota is a critical regulator within the microbiota-gut-brain axis, sensing, modifying, and tuning chemical signals from the brain. It may also affect AD pathogenesis and cognitive decline.

Gut microbiota in AD: positive progress and unclear mechanism

Researchers recently identified a strong correlation between altered gut microbiota and cognitive performance (Hu et al., 2016). It has also been found that microbiota composition and diversity are perturbed in AD mice (Fox et al., 2019), implying that the microbiota has a nonnegligible role in AD progression. Compared with control participants, gut microbiome microbial richness and diversity were both decreased in participants with AD (Jung et al., 2022). The abundance of phylum-level Firmicutes and Actinobacteria is lower, and the abundance of Bacteroidetes higher, in those with AD (Vogt et al., 2017). At the family level, Helicobacteraceae, Coriobacteriaceae, and Desulfovibrionaceae are significantly more abundant in APP/PS1 mice compared with wild-type (WT) mice. At the genus level, the mean abundances of Odouribacter and Helicobacter in APP/PS1 mice are obviously higher compared with WT mice, and Prevotella is significantly higher in WT compared with APP/PS1 mice (Shen et al., 2017). However, 16S rDNA sequencing showed gut microbiota diversity increases in AD Drosophila. At the family level, the proportions of Acetobacteraceae and Lactobacillaceae in AD Drosophila decreased dramatically, although they were largely enriched in the Drosophila microbiota. At the genus level, the mean control group abundances of Acetobacter and Lactobacillus were significantly higher compared with AD flies (Kong et al., 2018). Furthermore, metabolites derived from the gut microbiota, such as trimethylamine N-oxide, are elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid of individuals with AD, and elevated trimethylamine N-oxide is associated with AD pathology (Vogt et al., 2018). Despite significant differences and variation in gut microbiota among AD model species, these studies suggest a close relation between disturbances in gut microbiota and AD (Table 2).

Table 2.

Variation in gut microbiota in Alzheimer's disease (AD) patients and AD models

| Species | Increased abundance | Decreased abundance | Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| AD patients | Bacteroidetes | Firmicutes, Bifidobacterium | Vogt et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2019 |

| AD patients | Actinobacteria | Bacteroides, Ruminococcus, Lachnospiraceae, and Selenomonadales | Zhuang et al., 2018 |

| AD patients | Bifidobacterium, Sphingomonas, Lac tobacillus, and Blautia | Odoribacter, Anaerobacterium, and Papillibacter | Zhou et al., 2021 |

| APP/PS1 mice | Enterobacteriaceae and Verrucomicrobiaceae | Bacteroidaceae and Rikenellaceae | Chen et al., 2020 |

| APP/PS1 mice | Bacteroidetes and Tenericutes phylum | Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, and Actinobacteria | Harach et al., 2017 |

| APP/PS1 mice | Helicobacteraceae, Desulfovibrionaceae, Odoribacter, and Helicobacter | Prevotella | Shen et al., 2017 |

| 5×FAD mice | Proteobacteria and Firmicutes populations | Bacteroidetes population | Lee et al., 2019 |

| 5×FAD mice | Firmicutes, Clostridium leptum group | Bacteroidetes | Brandscheid et al., 2017 |

| 3×Tg AD mice | Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes | Cyanobacteria, Proteobacteria, Tenericutes, and Verrucomicrobia | Syeda et al., 2018 |

| AD drosophila | / | Acetobacteraceae and Lactobacillaceae | Kong et al., 2018 |

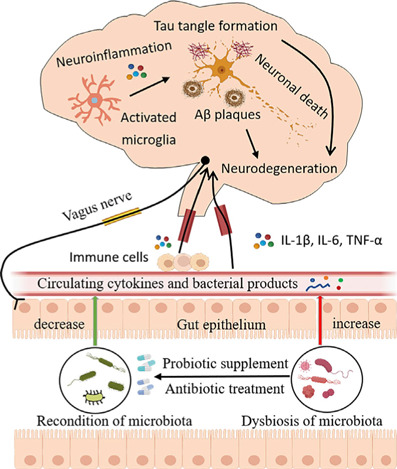

Despite the complex and numerous gut microbiota, several mechanisms for its involvement in, and impact on, AD have been explored. Asparagine endopeptidase (AEP), also known as delta-secretase, can simultaneously cleave increased APP and tau in the brain to form amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (Chen et al., 2021). In addition, enhancer-binding protein beta (C/EBPβ) is an Aβ and proinflammatory cytokine-activated transcription factor that regulates AEP transcription and protein levels in an age-dependent manner (Wang et al., 2018b). In the brains of mice with fecal transplant from patients with AD, investigators have found that C-EBPβ-AEP signaling is significantly activated and that mRNA transcription of major enzymes involved in arachidonic acid (AA) metabolism is increased. Elevated enzymes lead to upregulation of various AA metabolites, including prostaglandin E2 receptor EP3 subtype-like (PGE2), thromboxane B2, LKB4, and 12-HHT, among others, which stimulate microglial activation to aggravate neuroinflammation (Chen et al., 2022). EBPβ regulates proinflammatory genes in glial cells, such as nitric oxide synthase 2, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α (Straccia et al., 2011). The most direct route may be that gut microbiota in the feces of patients with AD directly upregulates C-EBPβ-AEP signaling, and APP and tau are cleaved by activated AEPs, directly triggering AD pathogenesis (Xu et al., 2023). Hypothesized relations between intestinal microbiota imbalance and AD pathology, as well as the repair of the microbiota-gut-brain axis by antibiotic therapy and probiotic supplements, are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Postulated links between gut microbiota dysregulation and AD pathology, and microbiota-gut-brain axis reconditioning with antibiotic treatment and probiotic supplementation.

Intestinal flora dysregulation in patients with AD allows increased intestinal barrier permeability, leading to microglial activation and neuroinflammation, which promotes Aβ plaque accumulation and tau hyperphosphorylation, ultimately leading to cognitive impairment. Antibiotics can modulate microbiota composition and probiotics can normalize intestinal bacteria. Created with Adobe Illustrator CS6. AD: Alzheimer's disease; Aβ: amyloid-β; IL-1β: interleukin-1β; IL-6: interleukin-6; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor.

Several classic interventions have been used to assess the relations between the gut microbiota and AD, including probiotic or antibiotic treatments, establishment of sterile animals, and fecal microbiota transplantation. These have demonstrated cognitive function improvements among patients with AD after 12-week probiotic consumption (Akbari et al., 2016). In 3×Tg-AD mice, early-stage AD progression was modulated by SLAB51 probiotic formulation (Bonfili et al., 2017). In a rat AD model, Morris water maze indicated beneficial effects of probiotics on cognitive function (Bonfili et al., 2017). Continuous ingestion of probiotics and prebiotics have been showed to delay neurocognitive decline and reduce AD risk (Tillisch et al., 2013; Akbari et al., 2016; Abraham et al., 2019; Kobayashi et al., 2019). Furthermore, a long-term broad-spectrum combined antibiotic regimen decreased Aβ plaque deposition and improved cognitive functions in a murine AD model (Minter et al., 2016). In rodent AD models, antibiotics had similar effects on AD pathogenesis, and reduced microglial activation, inflammatory cytokines, and brain Aβ (Yulug et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2022). Microbiota transplantation from aged APP/PS1 mice significantly increased Aβ in germ-free (GF) APP/PS1 mice (Harach et al., 2017). Additionally, a phase 3 clinical trial in China found that the sodium oligomannate GV-971 inhibits intestinal microecological disorders and related phenylalanine/isoleucine accumulation, controls neuroinflammation, and reverses cognitive impairment (Wang et al., 2019; Xiao et al., 2021). These cumulative studies support a close relation between gut microbiota and AD; while the specific mechanism remains unclear, neuroinflammation may be an important link.

Microbiota and microglia homeostasis

Given that the gut microbiota is an essential regulator of microglial function, microbiota-microglia interactions may be a critical link to CNS disorders. Observations from GF animals (which are hand-raised in an aseptic isolator without microorganism exposure) indicate important contributions of the gut microbiota to microglial homeostasis, including global defects from an immature phenotype, altered steady-state conditions, and diminished immune responses. When Erny et al. (2015) compared microglial morphology characteristics between GF and specific pathogen-free mice, microglia of the former had more complex morphologies, including longer processes, more segmented branches and terminal points, and greater density. Depletion of intestinal bacteria by antibiotic treatment induced a microglia phenotype comparable to that of GF mice. Microglial immaturity and malformation were restored by reintroducing complex, live microbiota or microbial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (Erny et al., 2015). Notably, the double transgenic APP/PS1 AD mouse model housed under GF conditions showed lower brain Aβ levels and deposition compared with APP/PS1 mice (Harach et al., 2017).

These studies emphasize the indispensable role of gut microbiota in microglia maturation and function, raising the possibility that microglia may require continuous input from the host microbiota to maintain CNS homeostasis. The mechanism by which unhealthy gut microbiota activates microglia remains to be determined. Close relations between potassium channels KCa3.1 and Kv1.3 and microglial activation have been shown repeatedly (Cocozza et al., 2021). Levels of KCa3.1 and Kv1.3 and mRNA levels of related inflammatory factors were increased in microglia isolated from brains of Western diet-fed mice (Jena et al., 2018). Additionally, Western diet-fed-derived saturated fatty acid can activate the microglial CD14-TLR4-MD2 complex, ultimately damaging microglia by inducing NF-κB signaling, which triggers neuroinflammation and proinflammatory cytokine secretions (Wieckowska-Gacek et al., 2021).

In summary, clinical and animal studies support relations between the gut microbiota and AD. While the specific underlying mechanism remains unknown, neuroinflammation caused by microglia may be an important contributor. According to current research, the classic interventions described above impact intestinal flora composition, and thus affect host cognitive behavior. Therefore, an in-depth understanding of the relations between intestinal flora and AD may open new methods for early AD treatment.

Other lifestyles factors linking microglia and AD

In addition to the aforementioned risk factors, AD is driven by numerous others, emphasizing the disease's complex, multifactorial nature. The evidence supporting several of these factors is described here.

Sleep and circadian rhythmicity

Sleep plays an important role in cognition and memory. Sleep disturbance (SD) increases Aβ burden, potentially triggering cognitive decline and increasing AD risk (Irwin and Vitiello, 2019). Microglial activation is a key mediator of SD-induced imbalance in inflammatory cytokines and cognitive impairment (Wadhwa et al., 2017a), and inhibiting microglial activation with minocycline can intervene to improve cognitive performance during SD (Wadhwa et al., 2017b). Furthermore, microglia possess a circadian clock that influences inflammatory responses via robust rhythms of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 mRNA (Fonken et al., 2015). In addition to inflammatory factor releases, other microglia functions are similarly influenced by circadian rhythms. One circadian clock component, Rev-erbα, plays a key role in microglial activation and neuroinflammation (Griffin et al., 2019). The Rev-erbα agonist SR9011 switches microglia to a neuroprotective phenotype (Griffin et al., 2020), decreasing phagocytic microglial capacity (Wang et al., 2020c), and inhibiting cellular metabolism (Wolff et al., 2020). Therefore, circadian rhythm disturbances may also affect microglial function by modulating the basic helix-loop-helix ARNT like 1 (BMAL1)-REV-ERBα axis, which can lead to cognitive dysfunction.

Physical exercise

The neuroprotective roles of physical exercise have been confirmed in several studies (Chen et al., 2016). It is well known that regular physical exercise is a modifiable lifestyle factor that can reduce AD risk and slow its progression. The functions of regular physical activity include cognitive improvement and amelioration of Aβ deposition and tau phosphorylation (Kelly, 2018). Compared with aged controls without neurological disease, postmortem brain samples from patients with AD show higher levels of proinflammatory microglia and lower levels of anti-inflammatory microglia (Kohman et al., 2013; He et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2017). Physical exercise also increases the number of anti-inflammatory phenotype microglia and suppresses activation of proinflammatory phenotype microglia in the hippocampus (Zhang et al., 2019), which are regulated by increasing anti-inflammatory factors and suppressing the production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Lu et al., 2017; Mee-Inta et al., 2019). Therefore, exercise may regulate microglia function and induce anti-inflammatory effects.

Smoking

Cigarette smoking is the most preventable cause of death and various diseases, including cardiovascular disease, lung disease, and various cancers (Billatos et al., 2021; Fagerberg and Barregard, 2021; Virani et al., 2021; Hecht and Hatsukami, 2022). Smoking not only increases the incidence of these diseases, it leads to neurocognitive abnormalities, significantly increasing symptom progression over time (Durazzo et al., 2010). Epidemiology studies have explored several aspects of the association between smoking and AD. First, the likelihood of AD in smokers is greatly increased; second, smokers have a lower age of AD onset compared with nonsmokers; and third, decreasing smoking prevalence may reduce the future AD incidence (Barnes and Yaffe, 2011; Henderson, 2014). To some extent, smoking harms the brain in ways similar to that of PM2.5 or other air pollution. Cigarette smoking causes brain alterations including increased oxidative stress (Durazzo et al., 2016b), decreased hippocampal and left hippocampal volumes (Durazzo et al., 2013), and inhibited dentate gyrus neurogenesis (Durazzo et al., 2016b). In terms of pathological changes, cigarette smoking tends to be associated with more amyloid deposition and tau phosphorylation (Durazzo et al., 2016b), and lower rates of cortical glucose metabolism have been shown in autopsy and clinical studies (Durazzo et al., 2016a). Thus, while smoking is a major modifiable risk factor for AD, the underlying mechanisms are still being investigated. Because one possible mechanism is neuroinflammation resulting from microglial activation, our group explored microglia affected by chronic cigarette smoke (CS). Quantitatively, animal studies have shown that long-term chronic CS exposure can induce neuroinflammation by increasing microglial activation, which can be reduced following acute nicotine withdrawal (Adeluyi et al., 2019; Prasedya et al., 2020; Sivandzade et al., 2020). Morphologically, CS transforms hippocampal microglia into amoeboid shapes, mainly characterized by a decrease in cell processes total length and mean branch numbers in the CA3, but not the CA1 or dentate gyrus regions (Dobric et al., 2022). Thus, chronic CS exposure causes active morphologic changes, and specifically reducing microglial numbers. In conclusion, understanding how smoking impacts cognition by altering microglia may aid developing microglial modulators as a smoking-induced AD treatment. This remains an area in which significant research is needed.

Caffeine

Coffee, among the most widely-consumed beverages worldwide, is correlated with reduced AD risk (Londzin et al., 2021). The mechanisms of caffeine in AD prevention and regulation include: (1) Reduced Aβ plaque production via decreased expressions of presenilin 1 (PS1) and β-secretase (BACE), a possible mechanism by which caffeine protects cognition (Arendash et al., 2006); (2) Reduced phosphorylation levels by reducing glycogen synthase kinase 3 alpha dysregulation and glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta expression, both of which result from attenuating TNF-α-c-Jun and Akt-mTOR signaling (Arendash et al., 2009; Zhou and Zhang, 2021); and (3) Attenuation of AD-associated neuroinflammation by inhibiting the excessive microglia activation and reducing BBB disruption (Madeira et al., 2017). In one in vivo study, daily injection of caffeine for 4 weeks significantly decreased Iba-1 expression and microglial number in the LPS-treated mouse brain, though morphological changes were not significant (Badshah et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2022). It has also been demonstrated that caffeine decreases the microglial proinflammatory phenotype by downregulating the levels of CD86 and iNOS and inhibiting TNF-α and IL-1β secretions. In contrast, caffeine upregulates the anti-inflammatory phenotype of microglia, elevates expressions of CD206 and Arg1, and promotes secretion of anti-inflammatory factors (Yang et al., 2022). Caffeine inhibits microglial hyperactivation, reduces microglial polarization to the proinflammatory phenotype, and promotes microglial polarization to the anti-inflammatory type (Yang et al., 2022). Furthermore, pKr-2 induces hippocampal neurodegeneration by stimulating TLR4 with PU.1 and c-Jun, serving as a proinflammatory stimulus for microglial response. Caffeine also inhibits hippocampal pKr-2 expression and reduces TLR4 upregulation in 5xFAD mouse microglia, alleviating hippocampal neurodegeneration (Kim et al., 2023). While it is therefore reasonable to speculate that the positive effects of caffeine on AD are achieved via shifts in microglial phenotype, the specific mechanism is currently unclear.

Limitations

Some limitations to this review should be acknowledged. Due to the unique nature of brain diseases, the research findings summarized herein regarding how modern lifestyle factors such as air quality, stress, gut microbiota, sleep, physical exercise, smoking, and caffeine regulate microglia and AD are largely based on cellular or rodent model studies. However, these findings remain to be confirmed by epidemiological and clinical data. Several methods found to slow AD progression by microglia-based intervention (e.g., microglia ablation, microglia inhibitors, gene knockout, stem cell transplantation) also require further evaluation to facilitate clinical research.

Conclusions and Perspectives

Age is an independent risk factor for AD, a multifactorial disease affected by both modifiable environmental risk factors and genetics. Herein, we reviewed how modern lifestyle factors, including air quality (i.e., PM2.5), stress, the gut microbiota, sleep and circadian rhythms, and physical exercise, affect animal models and human microglia regulation in the AD context. The exact role and importance of microglia in the onset and development of AD is a current research hotspot, as is how different lifestyle factors regulate microglia and affect AD. Notably, these lifestyle factors do not affect AD via microglia independently. For example, chronic sleep disruption affects the gut microbiota by altering taxonomic profiles of fecal microbiota. And exercise is also involved in the regulation of circadian melatonin rhythm and the sleep-wake cycle (Tahara and Shibata, 2018). Various environmental and lifestyle factors may thus synergistically promote AD development. Increased AD susceptibility can be driven by modulation of microglia through different lifestyles above, thus determining the true role and importance of microglia in AD remains an area worthy of further investigation at present.

Clinical pharmacology now used in AD treatment generally only addresses symptoms, rather than preventing the disease (Cai et al., 2022). The hypothesis that microglial activation may adversely affect disease progression has prompted the search for ways to deplete microglia via compounds and genetic models. Although various methods are available for microglial ablation, the use of most depletion methods, including the CX3CR1creERxDTRff mouse model (Bruttger et al., 2015; Rice et al., 2017), the CD11b-HSVTK model (Grathwohl et al., 2009), and clodronate liposomes (Faustino et al., 2011) is prohibited for various reasons. In contrast to microglial depletion paradigms, CSF1R inhibitors have unique advantages due to their highly selective effects, noninvasive administration, and rapid/sustained microglia elimination. CSF1R inhibitors PLX5622 and PLX3397 eliminate almost all microglia from the 5xFAD mouse brain and prevent plaque formation (Spangenberg et al., 2019), concomitant with dopaminergic signaling rescue (Son et al., 2020).

Blockage of microglial activation is neuroprotective in AD animal models (Akiyama et al., 2000). The beneficial effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug treatment have been examined in multiple epidemiological and animal model studies (McGeer and McGeer, 2013). Numerous epidemiological studies have indicated that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use may protect against AD development, though this result is not clinically significant and its mechanism of action is unclear (Etminan et al., 2003; Rosenberg, 2005; Ozben and Ozben, 2019). Minocycline, a commonly used tetracycline antibiotic, is a strong inhibitor of the microglial shift to a proinflammatory phenotype (Kobayashi et al., 2013). As a modulator of microglial inflammatory responses, minocycline has also shown neuroprotective effects in an AD animal model (McLarnon, 2019).

As described above, genome-wide association studies have identified many risk factors expressed by microglia in AD. Ablation of the NLRP3 gene is protective in AD models. Using an AD mouse model of APP/PS1, Aβ pathology and Aβ-induced synaptic damage were markedly reduced in Nlrp3 knockout mice (APP/PS1/Nlrp3−/−) (Scheiblich et al., 2020). In addition to knockouts, several NLRP3 inhibitors have been described, including the sulfonylurea-containing compound MCC950. In vivo, this compound can inhibit ATP hydrolysis and IL-1β release, reduce amyloid plaque burden, and improve cognitive behavior in AD model mice (Thawkar and Kaur, 2019). These findings suggest that NLRP3 gene ablation or inhibition as an AD treatment target, though it is too early for clinical assessment. A genetic link between TREM2 and AD was established in 2013; thus, selective modulation of TREM2 may be another potential therapeutic strategy (Guerreiro et al., 2013). To date, several related agonist antibodies have been found to activate TREM2, including AL002 and AL002a/c (Cignarella et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020b). However, novel TREM2-based treatments to manipulate microglial function currently face significant barriers to clinical application. Exciting achievements have been shown in stem cell-derived microglial replacement therapy in animal models. However, maintaining microglia in a beneficial state remains a challenge (Temple, 2023). Experimentally, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) transplantation can modulate microglial activation in APP/PS1 mice, showing both decreased inflammatory cells and increased anti-inflammatory cytokines, indicating alternative microglial activation. In addition, MSCs transplanted into APP/PS1 mice can ameliorate AD pathology and reverse spatial learning and memory declines (Zhang et al., 2016; Bagheri-Mohammadi, 2021). Although experimental and preclinical work suggests that stem cells are microglial regulators, with considerable therapeutic potential in AD, major safety and ethical issues remain to be overcome.

In summary, the effects of environmental factors on AD are often synergistic, multifaceted, and closely associated with individual genetic susceptibility. The compendium of research on the mechanisms by which environmental factors affect AD leave no doubt that microglia, the neuroimmunological brain cells, play an important role. Considering the increased incidence of patients with sporadic AD, who have genetic polymorphisms associated with microglia, it is important to understand the role of microglia in AD development, toward strategies targeting microglia for AD treatment. In the effort to intervene and control environmental AD risk factors at an early stage, an in-depth understanding of the role of microglia could be a key to AD treatment breakthroughs.

Funding Statement

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Nos. 82071190 and 82371438 (to LC) and Innovative Strong School Project of Guangdong Medical University, No. 4SG21230G (to LC), and Scientific Research Foundation of Guangdong Medical University, No. GDMUM2020017 (to CL).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data availability statement: Not applicable.

C-Editor: Zhao M; S-Editor: Li CH; L-Editors: Li CH, Song LP; T-Editor: Jia Y

References

- Abraham D, Feher J, Scuderi GL, Szabo D, Dobolyi A, Cservenak M, Juhasz J, Ligeti B, Pongor S, Gomez-Cabrera MC, Vina J, Higuchi M, Suzuki K, Boldogh I, Radak Z. Exercise and probiotics attenuate the development of Alzheimer's disease in transgenic mice: Role of microbiome. Exp Gerontol. 2019;115:122–131. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2018.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adeluyi A, Guerin L, Fisher ML, Galloway A, Cole RD, Chan SSL, Wyatt MD, Davis SW, Freeman LR, Ortinski PI, Turner JR. Microglia morphology and proinflammatory signaling in the nucleus accumbens during nicotine withdrawal. Sci Adv. 2019;5:eaax7031. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax7031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ailshire JA, Crimmins EM. Fine particulate matter air pollution and cognitive function among older US adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180:359–366. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajmani GS, Suh HH, Wroblewski KE, Kern DW, Schumm LP, McClintock MK, Yanosky JD, Pinto JM. Fine particulate matter exposure and olfactory dysfunction among urban-dwelling older US adults. Environ Res. 2016;151:797–803. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbari E, Asemi Z, Daneshvar Kakhaki R, Bahmani F, Kouchaki E, Tamtaji OR, Hamidi GA, Salami M. Effect of probiotic supplementation on cognitive function and metabolic status in Alzheimer's disease: a randomized, double-blind and controlled trial. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:256. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama H, Barger S, Barnum S, Bradt B, Bauer J, Cole GM, Cooper NR, Eikelenboom P, Emmerling M, Fiebich BL, Finch CE, Frautschy S, Griffin WS, Hampel H, Hull M, Landreth G, Lue L, Mrak R, Mackenzie IR, McGeer PL, et al. Inflammation and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:383–421. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00124-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alahmari A. Blood-brain barrier overview: structural and functional correlation. Neural Plast. 2021;2021:6564585. doi: 10.1155/2021/6564585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkadhi KA. Chronic psychosocial stress exposes Alzheimer's disease phenotype in a novel at-risk model. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2012;4:214–229. doi: 10.2741/371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso C, Guilarte M, Vicario M, Ramos L, Ramadan Z, Antolin M, Martinez C, Rezzi S, Saperas E, Kochhar S, Santos J, Malagelada JR. Maladaptive intestinal epithelial responses to life stress may predispose healthy women to gut mucosal inflammation. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:163–172.e161. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arango-Lievano M, Peguet C, Catteau M, Parmentier ML, Wu S, Chao MV, Ginsberg SD, Jeanneteau F. Deletion of neurotrophin signaling through the glucocorticoid receptor pathway causes tau neuropathology. Sci Rep. 2016;6:37231. doi: 10.1038/srep37231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arendash GW, Schleif W, Rezai-Zadeh K, Jackson EK, Zacharia LC, Cracchiolo JR, Shippy D, Tan J. Caffeine protects Alzheimer's mice against cognitive impairment and reduces brain beta-amyloid production. Neuroscience. 2006;142:941–952. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arendash GW, Mori T, Cao C, Mamcarz M, Runfeldt M, Dickson A, Rezai-Zadeh K, Tane J, Citron BA, Lin X, Echeverria V, Potter H. Caffeine reverses cognitive impairment and decreases brain amyloid-beta levels in aged Alzheimer's disease mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;17:661–680. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashok A, Rai NK, Tripathi S, Bandyopadhyay S. Exposure to As-, Cd-, and Pb-mixture induces Abeta, amyloidogenic APP processing and cognitive impairments via oxidative stress-dependent neuroinflammation in young rats. Toxicol Sci. 2015;143:64–80. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfu208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badshah H, Ikram M, Ali W, Ahmad S, Hahm JR, Kim MO. Caffeine may abrogate lps-induced oxidative stress and neuroinflammation by regulating Nrf2/TLR4 in adult mouse brains. Biomolecules. 2019;9:719. doi: 10.3390/biom9110719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri-Mohammadi S. Microglia in Alzheimer's disease: the role of stem cell-microglia interaction in brain homeostasis. Neurochem Res. 2021;46:141–148. doi: 10.1007/s11064-020-03162-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai KJ, Chuang KJ, Chen CL, Jhan MK, Hsiao TC, Cheng TJ, Chang LT, Chang TY, Chuang HC. Microglial activation and inflammation caused by traffic-related particulate matter. Chem Biol Interact. 2019;311:108762. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2019.108762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bairamian D, Sha S, Rolhion N, Sokol H, Dorothee G, Lemere CA, Krantic S. Microbiota in neuroinflammation and synaptic dysfunction: a focus on Alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2022;17:19. doi: 10.1186/s13024-022-00522-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakulski KM, Dolinoy DC, Sartor MA, Paulson HL, Konen JR, Lieberman AP, Albin RL, Hu H, Rozek LS. Genome-wide DNA methylation differences between late-onset Alzheimer's disease and cognitively normal controls in human frontal cortex. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;29:571–588. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-111223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes DE, Yaffe K. The projected effect of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer's disease prevalence. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:819–828. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70072-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram L, et al. Genome-wide association analysis reveals putative Alzheimer's disease susceptibility loci in addition to APOE. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:623–632. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian Y, Pan Z, Hou Z, Huang C, Li W, Zhao B. Learning, memory, and glial cell changes following recovery from chronic unpredictable stress. Brain Res Bull. 2012;88:471–476. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bihaqi SW, Eid A, Zawia NH. Lead exposure and tau hyperphosphorylation: An in vitro study. Neurotoxicology. 2017;62:218–223. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2017.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billatos E, et al. Distinguishing smoking-related lung disease phenotypes via imaging and molecular features. Chest. 2021;159:549–563. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.08.2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisht K, Sharma KP, Lecours C, Sanchez MG, El Hajj H, Milior G, Olmos-Alonso A, Gomez-Nicola D, Luheshi G, Vallieres L, Branchi I, Maggi L, Limatola C, Butovsky O, Tremblay ME. Dark microglia: A new phenotype predominantly associated with pathological states. Glia. 2016;64:826–839. doi: 10.1002/glia.22966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisht K, Sharma K, Tremblay ME. Chronic stress as a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease: Roles of microglia-mediated synaptic remodeling, inflammation, and oxidative stress. Neurobiol Stress. 2018;9:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block ML, Wu X, Pei Z, Li G, Wang T, Qin L, Wilson B, Yang J, Hong JS, Veronesi B. Nanometer size diesel exhaust particles are selectively toxic to dopaminergic neurons: the role of microglia, phagocytosis, and NADPH oxidase. FASEB J. 2004;18:1618–1620. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1945fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block ML, Calderon-Garciduenas L. Air pollution: mechanisms of neuroinflammation and CNS disease. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:506–516. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollinger JL, Bergeon Burns CM, Wellman CL. Differential effects of stress on microglial cell activation in male and female medial prefrontal cortex. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;52:88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfili L, Cecarini V, Berardi S, Scarpona S, Suchodolski JS, Nasuti C, Fiorini D, Boarelli MC, Rossi G, Eleuteri AM. Microbiota modulation counteracts Alzheimer's disease progression influencing neuronal proteolysis and gut hormones plasma levels. Sci Rep. 2017;7:2426. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02587-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandscheid C, Schuck F, Reinhardt S, Schafer KH, Pietrzik CU, Grimm M, Hartmann T, Schwiertz A, Endres K. Altered gut microbiome composition and tryptic activity of the 5xFAD Alzheimer's mouse model. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;56:775–788. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briones A, Gagno S, Martisova E, Dobarro M, Aisa B, Solas M, Tordera R, Ramirez M. Stress-induced anhedonia is associated with an increase in Alzheimer's disease-related markers. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165:897–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01602.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruttger J, Karram K, Wortge S, Regen T, Marini F, Hoppmann N, Klein M, Blank T, Yona S, Wolf Y, Mack M, Pinteaux E, Muller W, Zipp F, Binder H, Bopp T, Prinz M, Jung S, Waisman A. Genetic cell ablation reveals clusters of local self-renewing microglia in the mammalian central nervous system. Immunity. 2015;43:92–106. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciottolo M, Wang X, Driscoll I, Woodward N, Saffari A, Reyes J, Serre ML, Vizuete W, Sioutas C, Morgan TE, Gatz M, Chui HC, Shumaker SA, Resnick SM, Espeland MA, Finch CE, Chen JC. Particulate air pollutants, APOE alleles and their contributions to cognitive impairment in older women and to amyloidogenesis in experimental models. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1022. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Liu J, Wang B, Sun M, Yang H. Microglia in the neuroinflammatory pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease and related therapeutic targets. Front Immunol. 2022;13:856376. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.856376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderon-Garciduenas L, Solt AC, Henriquez-Roldan C, Torres-Jardon R, Nuse B, Herritt L, Villarreal-Calderon R, Osnaya N, Stone I, Garcia R, Brooks DM, Gonzalez-Maciel A, Reynoso-Robles R, Delgado-Chavez R, Reed W. Long-term air pollution exposure is associated with neuroinflammation, an altered innate immune response, disruption of the blood-brain barrier, ultrafine particulate deposition, and accumulation of amyloid beta-42 and alpha-synuclein in children and young adults. Toxicol Pathol. 2008a;36:289–310. doi: 10.1177/0192623307313011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderón-Garcidueñas L, Mora-Tiscareño A, Ontiveros E, Gómez-Garza G, Barragán-Mejía G, Broadway J, Chapman S, Valencia-Salazar G, Jewells V, Maronpot RR, Henríquez-Roldán C, Pérez-Guillé B, Torres-Jardón R, Herrit L, Brooks D, Osnaya-Brizuela N, Monroy ME, González-Maciel A, Reynoso-Robles R, Villarreal-Calderon R, et al. Air pollution, cognitive deficits and brain abnormalities: a pilot study with children and dogs. Brain Cogn. 2008b;68:117–127. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderon-Garciduenas L, Franco-Lira M, D'Angiulli A, Rodriguez-Diaz J, Blaurock-Busch E, Busch Y, Chao CK, Thompson C, Mukherjee PS, Torres-Jardon R, Perry G. Mexico City normal weight children exposed to high concentrations of ambient PM2.5 show high blood leptin and endothelin-1, vitamin D deficiency, and food reward hormone dysregulation versus low pollution controls. Relevance for obesity and Alzheimer disease. Environ Res. 2015;140:579–592. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderon-Garciduenas L, Mukherjee PS, Waniek K, Holzer M, Chao CK, Thompson C, Ruiz-Ramos R, Calderon-Garciduenas A, Franco-Lira M, Reynoso-Robles R, Gonzalez-Maciel A, Lachmann I. Non-phosphorylated tau in cerebrospinal fluid is a marker of Alzheimer's disease continuum in young urbanites exposed to air pollution. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;66:1437–1451. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Zhou Y, Wang H, Alam A, Kang SS, Ahn EH, Liu X, Jia J, Ye K. Gut inflammation triggers C/EBPbeta/delta-secretase-dependent gut-to-brain propagation of Abeta and Tau fibrils in Alzheimer's disease. EMBO J. 2021;40:e106320. doi: 10.15252/embj.2020106320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Liao J, Xia Y, Liu X, Jones R, Haran J, McCormick B, Sampson TR, Alam A, Ye K. Gut microbiota regulate Alzheimer's disease pathologies and cognitive disorders via PUFA-associated neuroinflammation. Gut. 2022;71:2233–2252. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-326269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WW, Zhang X, Huang WJ. Role of physical exercise in Alzheimer's disease. Biomed Rep. 2016;4:403–407. doi: 10.3892/br.2016.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Fang L, Chen S, Zhou H, Fan Y, Lin L, Li J, Xu J, Chen Y, Ma Y, Chen Y. Gut microbiome alterations precede cerebral amyloidosis and microglial pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:8456596. doi: 10.1155/2020/8456596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Saffari A, Sioutas C, Forman HJ, Morgan TE, Finch CE. Nanoscale particulate matter from urban traffic rapidly induces oxidative stress and inflammation in olfactory epithelium with concomitant effects on brain. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124:1537–1546. doi: 10.1289/EHP134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Oh JY, Lee YS, Min KH, Hur GY, Lee SY, Kang KH, Shim JJ. Harmful impact of air pollution on severe acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: particulate matter is hazardous. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:1053–1059. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S156617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chouliaras L, Mastroeni D, Delvaux E, Grover A, Kenis G, Hof PR, Steinbusch HW, Coleman PD, Rutten BP, van den Hove DL. Consistent decrease in global DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation in the hippocampus of Alzheimer's disease patients. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:2091–2099. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cignarella F, Filipello F, Bollman B, Cantoni C, Locca A, Mikesell R, Manis M, Ibrahim A, Deng L, Benitez BA, Cruchaga C, Licastro D, Mihindukulasuriya K, Harari O, Buckland M, Holtzman DM, Rosenthal A, Schwabe T, Tassi I, Piccio L. TREM2 activation on microglia promotes myelin debris clearance and remyelination in a model of multiple sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2020;140:513–534. doi: 10.1007/s00401-020-02193-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocozza G, Garofalo S, Capitani R, D'Alessandro G, Limatola C. Microglial potassium channels: from homeostasis to neurodegeneration. Biomolecules. 2021;11:1774. doi: 10.3390/biom11121774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colao A, Muscogiuri G, Piscitelli P. Environment and health: not only cancer. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:724. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13070724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa LG, Cole TB, Coburn J, Chang YC, Dao K, Roque PJ. Neurotoxicity of traffic-related air pollution. Neurotoxicology. 2017;59:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadros MA, Martin C, Coltey P, Almendros A, Navascues J. First appearance, distribution, and origin of macrophages in the early development of the avian central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 1993;330:113–129. doi: 10.1002/cne.903300110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE, Ling AV, Devlin AS, Varma Y, Fischbach MA, Biddinger SB, Dutton RJ, Turnbaugh PJ. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505:559–563. doi: 10.1038/nature12820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Cuesta-Zuluaga J, Kelley ST, Chen Y, Escobar JS, Mueller NT, Ley RE, McDonald D, Huang S, Swafford AD, Knight R, Thackray VG. Age- and sex-dependent patterns of gut microbial diversity in human adults. mSystems. 2019;4:e00261–19. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00261-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L, Ma M, Li S, Zhou L, Ye S, Wang J, Yang Q, Xiao C. Protective effect and mechanism of baicalin on lung inflammatory injury in BALB/cJ mice induced by PM2.5. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2022;248:114329. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.114329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devi L, Alldred MJ, Ginsberg SD, Ohno M. Sex- and brain region-specific acceleration of beta-amyloidogenesis following behavioral stress in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Mol Brain. 2010;3:34. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-3-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobric A, De Luca SN, Seow HJ, Wang H, Brassington K, Chan SMH, Mou K, Erlich J, Liong S, Selemidis S, Spencer SJ, Bozinovski S, Vlahos R. Cigarette smoke exposure induces neurocognitive impairments and neuropathological changes in the hippocampus. Front Mol Neurosci. 2022;15:893083. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2022.893083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Preez A, Onorato D, Eiben I, Musaelyan K, Egeland M, Zunszain PA, Fernandes C, Thuret S, Pariante CM. Chronic stress followed by social isolation promotes depressive-like behaviour, alters microglial and astrocyte biology and reduces hippocampal neurogenesis in male mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;91:24–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn AR, O'Connell KMS, Kaczorowski CC. Gene-by-environment interactions in Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;103:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Meyerhoff DJ, Nixon SJ. Chronic cigarette smoking: implications for neurocognition and brain neurobiology. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7:3760–3791. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7103760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Meyerhoff DJ, Nixon SJ. Interactive effects of chronic cigarette smoking and age on hippocampal volumes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133:704–711. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Mattsson N, Weiner MW, Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging I. Interaction of cigarette smoking history with APOE genotype and age on amyloid level, glucose metabolism, and neurocognition in cognitively normal elders. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016a;18:204–211. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Korecka M, Trojanowski JQ, Weiner MW, R OH, Ashford JW, Shaw LM, Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging I. Active cigarette smoking in cognitively-normal elders and probable Alzheimer's disease is associated with elevated cerebrospinal fluid oxidative stress biomarkers. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016b;54:99–107. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efthymiou AG, Goate AM. Late onset Alzheimer's disease genetics implicates microglial pathways in disease risk. Mol Neurodegener. 2017;12:43. doi: 10.1186/s13024-017-0184-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elahi M, Motoi Y, Shimonaka S, Ishida Y, Hioki H, Takanashi M, Ishiguro K, Imai Y, Hattori N. High-fat diet-induced activation of SGK1 promotes Alzheimer's disease-associated tau pathology. Hum Mol Genet. 2021;30:1693–1710. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddab115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder A, Gelein R, Silva V, Feikert T, Opanashuk L, Carter J, Potter R, Maynard A, Ito Y, Finkelstein J, Oberdorster G. Translocation of inhaled ultrafine manganese oxide particles to the central nervous system. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:1172–1178. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erny D, Hrabe de Angelis AL, Jaitin D, Wieghofer P, Staszewski O, David E, Keren-Shaul H, Mahlakoiv T, Jakobshagen K, Buch T, Schwierzeck V, Utermohlen O, Chun E, Garrett WS, McCoy KD, Diefenbach A, Staeheli P, Stecher B, Amit I, Prinz M. Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:965–977. doi: 10.1038/nn.4030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estudillo E, López-Ornelas A, Rodríguez-Oviedo A, Gutiérrez de la Cruz N, Vargas-Hernández MA, Jiménez A. Thinking outside the black box: are the brain endothelial cells the new main target in Alzheimer's disease? Neural Regen Res. 2023;18:2592–2598. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.373672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etminan M, Gill S, Samii A. Effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on risk of Alzheimer's disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 2003;327:128. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7407.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerberg B, Barregard L. Review of cadmium exposure and smoking-independent effects on atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the general population. J Intern Med. 2021;290:1153–1179. doi: 10.1111/joim.13350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasae KD, Abolaji AO, Faloye TR, Odunsi AY, Oyetayo BO, Enya JI, Rotimi JA, Akinyemi RO, Whitworth AJ, Aschner M. Metallobiology and therapeutic chelation of biometals (copper, zinc and iron) in Alzheimer's disease: Limitations, and current and future perspectives. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2021;67:126779. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2021.126779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faustino JV, Wang X, Johnson CE, Klibanov A, Derugin N, Wendland MF, Vexler ZS. Microglial cells contribute to endogenous brain defenses after acute neonatal focal stroke. J Neurosci. 2011;31:12992–13001. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2102-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]