Keywords: axonal debris, inflammatory factors, macrophages, neutrophil peptide 1, peripheral nerve injury, peripheral nerve regeneration, RAW 264.7 cells, sciatic nerve, Wallerian degeneration

Abstract

Macrophages play an important role in peripheral nerve regeneration, but the specific mechanism of regeneration is still unclear. Our preliminary findings indicated that neutrophil peptide 1 is an innate immune peptide closely involved in peripheral nerve regeneration. However, the mechanism by which neutrophil peptide 1 enhances nerve regeneration remains unclear. This study was designed to investigate the relationship between neutrophil peptide 1 and macrophages in vivo and in vitro in peripheral nerve crush injury. The functions of RAW 264.7 cells were elucidated by Cell Counting Kit-8 assay, flow cytometry, migration assays, phagocytosis assays, immunohistochemistry and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Axonal debris phagocytosis was observed using the CUBIC (Clear, Unobstructed Brain/Body Imaging Cocktails and Computational analysis) optical clearing technique during Wallerian degeneration. Macrophage inflammatory factor expression in different polarization states was detected using a protein chip. The results showed that neutrophil peptide 1 promoted the proliferation, migration and phagocytosis of macrophages, and CD206 expression on the surface of macrophages, indicating M2 polarization. The axonal debris clearance rate during Wallerian degeneration was enhanced after neutrophil peptide 1 intervention. Neutrophil peptide 1 also downregulated inflammatory factors interleukin-1α, -6, -12, and tumor necrosis factor-α in vivo and in vitro. Thus, the results suggest that neutrophil peptide 1 activates macrophages and accelerates Wallerian degeneration, which may be one mechanism by which neutrophil peptide 1 enhances peripheral nerve regeneration.

Introduction

Epidemiological analysis of peripheral nerve injury indicates that approximately 2.8% of trauma patients worldwide suffer from peripheral nerve injury (Lago et al., 2007), with hundreds of thousands of new cases reported annually. Once injury occurs, it can result in irreversible lifelong disability, such as limb paresthesia, movement disorders, or limb paralysis, which greatly endangers the patient's life and health (Sang et al., 2018). Effectively promoting the repair of peripheral nerve injury has become a major global public health problem, for which a solution is urgently needed. Various strategies have been developed to promote peripheral nerve regeneration, including biological agents (Sang et al., 2018), synthetic drugs (Catapano et al., 2017), cell therapy (Jiang et al., 2017), tissue-engineering methods (Mitsuzawa et al., 2019; Sarhane et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023), and surgical techniques (Midha and Grochmal, 2019). However, the treatment of peripheral nerve injury needs further to be explored.

Macrophages are important target cells for peripheral nerve regeneration and play a key role in the early stage of nerve injury and regeneration. Distal axons of a damaged nerve can survive for only a few days due to the lack of nutrition from the neuron cell body. Soon after, axon degeneration and disintegration occur during Wallerian degeneration, and axon debris is cleared by macrophage phagocytosis. Additionally, macrophage-derived vascular endothelial growth factor-A is a key component of neuromuscular junction recovery after injury (Lu et al., 2020). Macrophage phenotype directionally changes and creates a microenvironment suitable for nerve regeneration. Many tissue engineering studies have modulated macrophage phenotypes (Lv et al., 2017; Waters et al., 2018; Jia et al., 2019).

Neutrophil peptide 1 (NP-1) is an innate immune polypeptide secreted by neutrophils that affects protein expression in macrophages and has been referred to as a valve for macrophage-dependent inflammatory responses. NP-1 is a cell-synthesized peptide that directly enters target cells to participate in the translation process and regulate protein expression directly (Brook et al., 2016). Previously, we showed that a single intramuscular injection of NP-1 enhanced early functional recovery of the sciatic nerve after crush injury (Yuan et al., 2020). However, the mechanism whereby NP-1 promotes peripheral nerve regeneration is unclear. Given the close relationship between NP-1 and macrophages, we hypothesized that NP-1 promotes peripheral nerve regeneration through a mechanism involving macrophages. In the present study, we performed cytology and animal experiments to investigate the relationship between NP-1 and macrophages in Wallerian degeneration, and aimed to elucidate the mechanism whereby NP-1 promotes peripheral nerve regeneration.

Methods

Experimental animals

Fifty-one male Thy1-YFP-16 transgenic mice (6 weeks old, weighing 22 ± 5 g; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA, Strain# 003709, RRID: IMSR_JAX:003709) were randomly selected for animal model preparation according to the previous literature (Yuan et al., 2021). Of these mice, 24 were used for the optical clearing experiment, and the remaining mice were used for the protein chip experiment. The animals were caged in a specific-pathogen free area of the Experimental Animal Center of Peking University People's Hospital, and maintained at 24 ± 2°C with 50–55% relative humidity, a 12-hour light/dark cycle, and with free access to food and water (standard pellet feed and clean drinking water). The experimental procedures followed the Laboratory Animal Management Regulations of Peking University People's Hospital and were approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the People's Hospital of Peking University, China (approval No. 2015-50). The experiments were conducted in accordance with international laws and National Institutes of Health policies, including the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th ed., National Research Council, 2011). This study was reported in accordance with the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) 2.0 guidelines (Percie du Sert et al., 2020).

Cell proliferation assay

RAW264.7 cells have the characteristics of macrophages and can be used to examine the effects of treatments on macrophages in vitro (Caputo, 1988). RAW 264.7 cells (Cat# SCSP-5036, Chinese Academy of Sciences Cell Bank, Shanghai, China) were seeded in 96-well plates (3000 cells/well), incubated at 37°C for 12 hours, and then starved for 12 hours in high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) containing 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Next, the cells were cultured in NP-1 (0, 2, 4, 8, 10, 16, or 20 µg/mL; ChinaPeptides Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) for 12, 24, 36, or 72 hours. The cell morphology was photographed at each time point. Cell Counting Kit-8 reagent (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Shanghai, China) was added to each well (10 µL/well), followed by a 2-hour incubation at 37°C. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured with a microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) to determine optical density (OD) values in different groups. Cell proliferation was expressed as cell survival as follows: cell survival (%) = [A1 (NP-1) – A3 (blank)]/ [A2 (0 µg/mL NP-1) – A3 (blank)] × 100.

Cell hematoxylin-eosin staining

RAW 264.7 cells were seeded in a 48-well plate at approximately 2 × 104 cells/well. After adhering to the culture plate for 6–8 hours, the cells were cultured in high-glucose DMEM containing 10% FBS for 12–24 hours, and then treated for 36 hours and 72 hours with NP-1 (20 µg/mL) or blank medium prepared in the high-glucose DMEM containing 10% FBS. After washing with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), the cells were stained with 100 μL/well hematoxylin and eosin (Solarbio, Beijing, China) for 5 minutes at room temperature. Then, the cells were washed with PBS and photographed using an optical microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Colony formation assay

RAW 264.7 cells were seeded into 6-well plates with 1500 cells/well, cultured in high-glucose DMEM containing 10% FBS for 12–24 hours, and then treated for 14 days with NP-1 (20 µg/mL) or blank medium prepared in culture medium supplemented with 10% FBS for 10 days under normal conditions. Then, the colonies were washed with PBS twice, fixed in paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes and stained with 0.1% crystal violet (Solarbio) for 15 minutes.

Cell cycle determination

The cells were resuspended and mixed, seeded in 96-well plates (10,000 cells/well), incubated at 37C for 12 hours, and starved for 12 hours in high-glucose DMEM containing 10% FBS. The cells were then cultured for 72 hours in NP-1 solution (20 µg/mL) or blank medium. Subsequently, the pellets were digested, resuspended, and centrifuged at 1000 rotations/min for 3 minutes. The supernatant was discarded, and 1 mL DNA Staining Solution and 10 µL Permeabilization Solution (MultiSciences [Lianke] Biotech, Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China) were added, followed by vortexing for 10 seconds and incubation at room temperature for 30 minutes in the dark. Flow cytometry (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL, USA) was used for detection.

Cell apoptosis assay

A cell apoptosis assay was performed using an Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan). After transfection for 48 hours, 1 × 106 RAW 264.7 cells from the NP-1 group and blank-control group were collected, cultured in high-glucose DMEM containing 10% FBS for 72 hours, washed with PBS, and resuspended in 1 mL Annexin V binding solution. Then, 100 μL of the cell suspension was moved into new tubes. Subsequently, 5 μL Annexin V-FITC and 5 μL PI solution were added to the cell suspension and incubated at room temperature in the dark for 15 minutes. Afterwards, 400 μL Annexin V binding solution was added to the cell suspension. Cell apoptosis was measured using flow cytometry (Beckman Coulter).

Cell migration

Digested RAW 264.7 cells were resuspended in NP-1 solution (0 or 20 µg/mL), mixed, adjusted to a density of 2 × 105 cells/mL, and seeded into Transwell chambers (Corning, Steuben County, NY, USA; 200 µL cells/chamber). High-glucose DMEM was added to each well in the 24-well plate. After incubation for 24 hours, the culture medium in the chamber was aspirated, and the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes. After rinsing with PBS, the cells were stained using crystal violet (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) for 15 minutes, and the excess dye solution was gently removed with a cotton swab under running water. After cells were air dried in a fume hood, the distributions of cells in the Transwell chambers were observed under a light microscope. For each group, five fields were randomly viewed at 200 magnification, and ImageJ software (v1.8.0; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA; Schneider et al., 2012) was used to count the average number of cells in each group.

Cell phagocytosis

The RAW 264.7 cells were digested with trypsin (Gibco) at 4°C for 3 minutes, centrifuged at 1000 rotations/min for 3 minutes at 25°C, and resuspended in NP-1 solution (0 or 20 µg/mL). The cells were evenly mixed, and 20 µL of cell suspension was absorbed on a Countstar Automated Cell Counter (Countstar, Shanghai, China). The cells were seeded in 24-well plates (5 × 105 cells/well), incubated at 37°C for 12 hours, and starved in high-glucose DMEM for 12 hours. The cells were then cultured in NP-1 solution (20 µg/mL). After 72 hours, green fluorescent microspheres (cell:microsphere ratio = 1:30; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) were added and incubated at 37°C for 2 hours. The culture medium was aspirated, and the sediment was washed three times with PBS prewarmed at 37°C. The distribution of fluorescent microspheres was observed under an optical microscope using PBS as the imaging medium. For each group, five fields were randomly viewed at 200 magnification, and ImageJ software was used to calculate the positive area

Immunohistochemistry

RAW 264.7 cells were seeded in a 6-well plate at a density of 5000 cells/well. Cells received the same pretreatments as above and were divided into the blank group and the NP-1 group, which was treated for 24 hours with NP-1 solution (20 μg/mL). The cells were then washed with PBS, and treated with H2O2 (Beijing Chemical Plant, Beijing, China) for 10–15 minutes in the dark. Then, the cells were washed with PBS for 5 minutes and treated with 50 μL primary antibody working solution at 4°C overnight using the following antibodies: CD80 (1:200, Cat# 66406-1-Ig, Proteintech Group, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), F4/80 (1:500, Cat# 29414-1AP, Proteintech Group) and CD206 (1:500, Cat# 18704-1-AP, Proteintech Group). After washing with PBS for 5 minutes, the cells were treated following the introduction of the GTVisionTM III antimouse/rabbit immunohistochemistry test kit (Cat# GK500710, Gene Tech, Shanghai, China). Finally, the cells were photographed using an optical microscope. Under 200× magnification, screenshots of the same size were randomly selected for each well.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

RAW 264.7 cells were seeded in 96-well plates with 1 × 104 cells in each well. RAW 264.7 cells were pretreated as described above. Then, the cells were divided into the blank group and the NP-1 group, which was treated with NP-1 at 20 µg/mL. The culture supernatant was collected after 24 hours. The fluids were centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 minutes, and the concentrations of interleukin (IL)-1α, -1β, -6, -10, -12, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) were determined. Experiments were performed following the instructions of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Jianglai Bio, Shanghai, China).

Preparation of animal models

Twenty-four Thy1-YFP-16 mice were randomly assigned to a normal saline (NS) group (n = 12) and an NP-1 group (n = 12). Under anesthesia via inhalation of isoflurane (2% induction concentration and 1% maintenance concentration; Reward, Shenzhen, China), the mice were placed in the lateral position, the skin was cut along the axis of the right femur, and the intermuscular space was bluntly separated to expose the right sciatic nerve. A rubber strip was padded at the level of the piriformis. The sciatic nerve was clamped with microscopic hemostatic forceps (Cat# 06.0200, BELEVOR, Beijing, China) with two clasps locked for 30 seconds, and a 10-0 microscopic suture was knotted at the proximal and distal ends of the clamped nerve (2–3 mm). The piriformis muscle was cut off. The sciatic nerve was ligated and disconnected approximately 3 mm away from the proximal clamped end, and reverse suturing was performed from the distal clamped end to the adjacent muscle. After rinsing with NS, the intermuscular space was closed by continuous suturing. Next, the NP-1 and NS groups were intermuscularly injected with 50 µL NP-1 solution (20 µg/mL) or 50 µL NS, respectively, at the site where the sciatic nerve is located, using an insulin needle. The wounds in each group were closed layer by layer.

The remaining mice were randomly divided into the 0 d group (n = 3), NS group (n = 12) and NP-1 group (n = 12). The mice in the NS group and NP-1 group received the same procedures described above. Mice in the 0 d group were harvested after sciatic nerve crush injury.

CUBIC (Clear, Unobstructed Brain/Body Imaging Cocktails and Computational analysis) optical clearin

At 3 and 5 days postoperation, six mice were taken from each group, intraperitoneally injected with 1% sodium pentobarbital (30 mg/kg, Huayehuanyu, Beijing, China), and deeply perfused in succession with 37°C NS (containing 0.2% heparin sodium) and 4°C 4% paraformaldehyde (Solarbio). The sciatic nerve was exposed along the original incision. At the entry point of the muscle, the common peroneal nerve, tibial nerve, and sural nerve were separated, fixed with a plastic strip to prevent nerve deformation during posterior fixation, and stored in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C in the dark overnight.

After 12 hours of fixation using 4% paraformaldehyde, the specimens were dehydrated in a sucrose gradient, shaken in reagent 1 (a mixture of urea [25 wt% final concentration], Quadrol [25 wt% final concentration], Triton X-100 [15 wt% final concentration] and dH2O) at 37°C for 3 days, rinsed with 0.01 M PBS, dehydrated in sucrose, and immersed in reagent 2 (a mixture of urea [25 wt% final concentration], sucrose [50 wt% final concentration], triethanolamine [10 wt% final concentration] and dH2O) for 5 days (Susaki et al., 2015).

Post-transparent nerve specimens were integrally scanned in best-signal mode under a Leica confocal microscope (TCS-SP8 DIVE, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). The nerve specimens were completely scanned at 25× magnification with an excitation wavelength of 488 nm. The distance from the border where the fluorescence completely disappeared at the distal end of the damaged nerve to the distal clamped marker was considered as the full distance of axonal clearance. Image processing and data analysis were performed using ImageJ and Imaris 7.6.0 (Bitplane, St. Paul, MN, USA).

Protein chip

In the NP-1 and NS groups, the injured sciatic nerves of three model mice were used for each time point at 1, 3, 5, and 7 days after modeling. The protein chip (QAM-CYT-1; Shanghai Huaying Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was tested after the material was collected to observe the changes of inflammatory factors (IL-1α, -1β, -6, -10, -12, and TNF-α) in the groups.

Protein was extracted from mouse nerve tissue using a Raybiotech kit (RayBiotech, Norcross, GA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The protein concentration was quantified using the bicinchoninic acid method and then subjected to quality chip detection. After blocking, sample diluent was added. After washing, diluted Biotin-Antibody Cocktail and sample diluent were added and incubated at room temperature. After cleaning and drying, the chip was scanned using a GenePix 4000B chip scanner (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample sizes; however, our sample sizes are similar to those reported in a previous publication (Yuan et al., 2020). All data were statistically analyzed using SPSS software, version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). One-way analysis of variance followed by the least significant difference post hoc test was used for intergroup comparisons of protein chip data from the in vivo experiment and of all data from the in vitro experiments. An independent samples t-test was used for intergroup comparison of the CUBIC optical clearing experiment (CUBIC test data). Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Cell proliferation

Cells cultured in 20 μg/mL NP-1 had a higher OD value at each time point than the blank-control group and the lower NP-1 concentrations groups (P < 0.05; Figure 1A–D), and had a higher cell survival rate than the other groups, especially after stimulation for 72 hours. The cell survival rate of the 20 µg/ml group was 186.17%, which was significantly higher than that in the other groups (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

RAW 264.7 cell proliferation situation.

(A–D) Optical density (OD) values of the RAW 264.7 cells at 12 (A), 24 (B), 36 (C), or 72 hours (D) after neutrophil peptide 1 (NP-1) intervention. The results of 2 and 10 μg/mL were similar to adjacent concentrations, thus they were not shown. (E) Survival curves for each group at different time points. The cell survival rate of the 20 µg/mL group exceeded that of the NS group and was higher compared with the other groups. (F) Purple color shows the outcomes of the colony formation. Purple coloring was the RAW 264.7 cells. (G) Hematoxylin-eosin staining showed the proliferation of RAW 264.7 cells at 36 and 72 hours after 20 µg/mL NP-1 stimulation. The red arrow indicates the island-shape proliferation of RAW 264.7 cells. Original magnification, 100×. *P < 0.05, vs. 0 µg/mL group; #P < 0.05, vs. other groups. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3; one way analysis of variance followed by the least significant difference post hoc test). NS: Normal saline.

Hematoxylin-eosin staining and colony formation showed more cell proliferation in the NP-1 group, which was similar to the trend of Cell Counting Kit-8 results. The island-shaped proliferation of cells occurred earlier in the NP-1 group than in the control group (Figure 1).

Cell cycle distribution

After NP-1 stimulation, no significant difference was found in the proportion of cells in the S and G1 phases (P > 0.05), but the proportion of cells in the G2 phase in the NP-1 group was significantly higher than that in the blank-control group (P = 0.004; Figure 2). Therefore, RAW 264.7 cells treated with 20 μg/mL NP-1 showed increased cell mitosis, which was consistent with the results of the cell proliferation assays.

Figure 2.

Flow cytometry for RAW 264.7 cells cycle detection.

(A, B) Cells were treated with blank-control (0 µg/mL; A) and neutrophil peptide 1 (NP-1 20 µg/mL; B) for 72 hours. (C–E) Cell-cycle distributions at different stages. No significant differences were observed in the number of cells in the G1 and S phases. Significantly more cells were found in the G2 phase in the NP-1 treatment group than in the blank-control group. *P < 0.05. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3; one way analysis of variance followed by the least significant difference post hoc test).

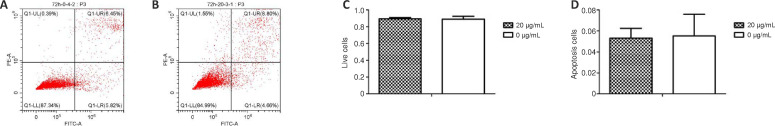

Cell apoptosis

Flow cytometry showed that there was no significant difference between the NP-1 and blank-control groups in the proportion of live cells and apoptotic cells (P = 0.671; Figure 3). This indicated that exogenous NP-1 effectively had no cytotoxicity in RAW 264.7 cells.

Figure 3.

Apoptosis analysis of RAW 264.7 cells cultured for 72 hours.

(A, B) Flow cytometry showed cell apoptosis in the blank-control group and neutrophil peptide 1 group (20 µg/mL). (C, D) Statistical graphs of live cells and apoptotic cells. There was no significant difference in the number of live cells and apoptotic cells between the two groups (P > 0.05). Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3; one way analysis of variance followed by the least significant difference post hoc test).

Cell migration

After 24 hours of culture, macrophages migrated from Transwell chambers to 24-well plates, and the number of cells in the 24-well plates was counted after crystal violet staining. The number of cells in the NP-1 group was significantly higher than that in the blank-control group (P < 0.05; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Transwell cell migration assays in RAW 264.7 cells.

(A, B) Representative images of crystal violet staining. Cells were treated with blank-control (0 µg/mL; A) and neutrophil peptide 1 (NP-1 20 µg/mL; B) for 24 hours. The irregular blue shape indicates that cells migrated onto the membrane. (C) The number of cell migration in NP-1 group was significantly higher than that in the blank-control group (*P < 0.05). Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3; one way analysis of variance followed by the least significant difference post hoc test). Original magnification, 100×.

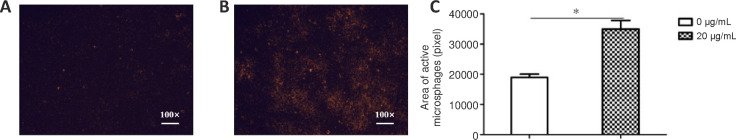

Cell phagocytosis

To observe the phagocytic ability of macrophages treated with NP-1 in vitro, fluorescent microspheres and RAW 264.7 cells were coincubated. The fluorescence-positive area of the NP-1 group was significantly larger than that of the blank-control group (P < 0.05; Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Phagocytosis of fluorescent microspheres in RAW 264.7 cells.

(A, B) Representative fluorescence images of cells were treated with blank-control (0 µg/mL; A) and NP-1 (20 µg/mL; B) for 72 hours. The orange color indicates fluorescent microspheres phagocytized by RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. Original magnification: 100×. (C) Significantly more fluorescent microspheres were phagocytosed in the neutrophil peptide 1 group than in the blank-control group. *P < 0.05. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3; one way analysis of variance followed by the least significant difference post hoc test).

Axonal clearance rate in Wallerian degeneration

Macrophages are key cells that lead to the removal of myelin and axonal debris during Wallerian degeneration after nerve injury. To investigate the ability of macrophages treated with NP-1 to phagocytize axonal debris in vivo, the CUBIC optical clearing technique was used to observe the neurodegeneration distance at 3 and 5 days. Confocal imaging showed that at 3 and 5 days after surgery, the complete neurodegeneration distance in the NP-1 group (20 µg/mL) was significantly longer than that in the NS group (P < 0.05; Figure 6). The combination of CUBIC optical clearing technology and Thy1-YFP transgenic mice allowed for a clear and comprehensive observation of histological changes of axons in Wallerian degeneration.

Figure 6.

Neurodegeneration distance imaging using CUBIC (Clear, Unobstructed Brain/Body Imaging Cocktails and Computational analysis) optical clearing technique.

(A, B) Neurodegeneration at 3 (A) and 5 (B) days post-operation. In each image, a fluorescence map, light micrograph, and composite map are shown (from right to left), with the scale indicating the distance from the stitch-mark point to the full-denaturation point. (C) Statistical plot of the complete neurodegeneration distance. The complete degeneration distance of the neutrophil peptide 1 (NP-1) group was significantly longer than that of the normal saline (NS) group. *P < 0.05. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 6; independent samples t-test).

Cell polarization

Macrophages are divided into two phenotypes: proinflammatory macrophages (M1) and anti-inflammatory macrophages (M2). M1 macrophages express the CD80 protein marker and M2 macrophages express the CD206 marker. The F4/80 protein is a marker of mature macrophages. Immunochemistry showed that the RAW 264.7 cells expressed F4/80−CD80−CD206+ after stimulation with NP-1 for 24 hours and F4/80+CD80−CD206+ in the blank group (0 µg/mL NP-1; Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

Polarization of macrophages and secretion of inflammatory cytokines.

(A) Representative immunohistochemistry images of F4/80, CD80 and CD206 in RAW 264.7 cells treated with blank-control (0 µg/mL) and NP-1 (20 µg/mL) for 24 hours. Brown cells indicated that RAW 264.7 cells expressed the protein. (B) Levels of inflammatory cytokines (integrated optical density) in cells after 1 day of NP-1 stimulation through enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay detection. (C) Levels of inflammatory cytokines (optical density) at 1, 3, 5, and 7 days after modeling. The trend of inflammatory factors over time was also shown in a single group. *P < 0.05. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3; one way analysis of variance followed by the least significant difference post hoc test). Original magnification: 200×. NP-1: Neutrophil peptide 1.

Cytokine secretion in vitro

M1 macrophages secrete IL-1α, -1β, -6, -12 and TNF-α, and M2 macrophages secrete IL-10. IL-1α, -6, -12 and TNF-α in the NP-1 group were significantly lower than those in the blank-group (0 µg/mL NP-1; P < 0.05). There were no differences in levels of IL-1β and -10 between the NP-1 group and the blank-control group (P > 0.05; Figure 7B).

Inflammatory factors expression in vivo

There were significant differences in the expression of IL-1α, -6, -12 and TNF-α on the protein chip at many time points (P < 0.05). IL-1α, -10 and -12 showed an increasing trend in the first week after crush injury in the injured nerve in the NP-1 group and the blank-control group. IL-1β, -6 and TNF-α fluctuated over time. IL-10 expression on the fifth day was significantly higher in the NP-1 group than in the NS group (P < 0.05; Figure 7C).

Discussion

NP-1 prevents tissue from early inflammatory damage by inhibiting classical and lectin pathways (van den Berg et al., 1998; Groeneveld et al., 2007). NP-1 increases mucin expression and promotes alveolar-epithelial wound healing and epithelial cell proliferation. In vitro culture of NCI-H292 respiratory epithelial cells has shown that mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase blocks NP-1-induced tissue repair and ERK1/2 activity (Aarbiou et al., 2002, 2004; Zhou et al., 2007). NP-1 has similar effects on renal cell carcinoma development, mouse fibroblast proliferation, and retinal epithelial cell proliferation (Murphy et al., 1993; Muller et al., 2002).

NP-1 has excellent tissue-repair ability, and its relationship with peripheral nerve injury has been elucidated (Yu et al., 2022). In our previous study, we found that NP-1 affects the proliferation, migration and apoptosis of Schwann cell line RSC96 (Kou et al., 2020). In addition, Nozdrachev et al. (2006) sutured isolated rat sciatic nerves in situ and intramuscularly injected NP-1 into the gluteus maximus for 7 continuous days. After 3 weeks, the conduction distance of the nerve impulse in the experimental group was 3.3 mm longer than that of the control group (Nozdrachev et al., 2006). Additionally, we demonstrated that continuous intramuscular injection of NP-1 promoted structural regeneration and functional recovery after sciatic nerve transection (Xu et al., 2016). In this study, administering NP-1 just once at the nerve injury site was sufficient to enhance nerve regeneration. In the neurological function test, NP-1 accelerated recovery of the nerve conduction velocity and increased the number of myelinated nerve fibers, while also protecting effector cells and delaying muscle atrophy when compared with the NS group. Administering a single dose of NP-1 was enough to produce an effect, suggesting that NP-1 may regulate early pathological changes after peripheral nerve injury.

Wallerian degeneration occurs after the peripheral nerve is damaged in the distal ends of damaged axons (Zhang et al., 2021). Axons and Schwann cells at both ends of the lesion disintegrate and release intracellular metabolites, triggering a strong inflammatory response, which releases numerous inflammatory factors and cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-6, and interferon γ. With the progression of Wallerian degeneration, anti-inflammatory factors, such as IL-10, are highly expressed at the lesion, and the inflammatory microenvironment of peripheral nerve regeneration changes from the proinflammatory phase to the anti-inflammatory phase (Rotshenker, 2003). Eventually, peripheral nerve regeneration begins. In this process, shorter Wallerian degeneration leads to a stronger regeneration (Yan et al., 2010).

In the present study, confocal imaging of the tissues after CUBIC tissue clearing showed that NP-1 promoted the clearance of axonal debris during Wallerian degeneration. With the CUBIC method, the refractive index of the medium surrounding the cells is adjusted to that of its component proteins. It is possible to use this technique to convert opaque tissue into a “transparent” state. The CUBIC technique decolorizes the blood by removing iron molecules in the tissues (Ueda et al., 2020), making it an ideal light-transparent technology that can be used for studying peripheral nerve tissues. The transgenic mouse strain B6.Cg-Tg(Thy1-YFP)16Jrs/J, referred to here as the Thy1-YFP transgenic mouse strain, is widely used in the field of neuroscience (Kamali et al., 2018; Mohan et al., 2018). The yellow fluorescent protein can be highly expressed in sensory and motor neurons as a fusion protein with Thy1 in a mouse model. Using this mouse strain, we found that NP-1 intervention accelerated the clearance of axonal debris from distally degenerating nerves during Wallerian degeneration.

In the present study, the optimal concentration of NP-1 was 20 µg/mL, as determined by the cell counting kit-8 method, which differed from that reported in previous studies (Brook et al., 2016; Maeda et al., 2016). The survival rate of the RAW 264.7 cells increased after intervention with 20 µg/mL NP-1. Flow cytometry-based detection showed that the number of cells undergoing late-stage DNA synthesis (G2 phase) increased after NP-1 treatment, suggesting that NP-1 may accelerate anabolism in macrophages to promote the accumulation of a large amount of synthetic products and cause macrophage proliferation. Flow cytometric analysis of apoptosis showed no significant difference in the number of apoptotic and viable cells between the two groups, suggesting that NP-1 does not induce apoptosis in macrophages.

Our analysis of macrophage phagocytosis of inorganic polymer microspheres showed that NP-1 increased the phagocytic ability of macrophages. Additionally, the Transwell assay is a well-recognized assay for analyzing cell migration. In this study, the number of cells crossing the Transwell membrane increased after NP-1 intervention, indicating that NP-1 strengthens the migration ability of macrophages.

The experiments in vivo showed consistent results that NP-1 accelerated the removal of axon fragments during Wallerian degeneration, which might be due to enhanced proliferation, migration and phagocytosis of macrophages. Macrophages are the most abundant immune cells in the peripheral nervous system, accounting for 2–9% of all cells (DeFrancesco-Lisowitz et al., 2015). These cells serve as the main scavenger cells during Wallerian degeneration by exerting innate immune functions and clearing cellular debris and small molecular substances that hinder nerve regeneration, which then initiates peripheral nerve regeneration (Lee et al., 2010). When macrophages are restored in the injured environment, the period of Wallerian degeneration is shortened and the nerve-regeneration ability is strengthened (Zigmond and Echevarria, 2019).

We found that NP-1 affected macrophage-induced inflammatory responses. The results in vivo and in vitro were consistent, and demonstrated that NP-1 downregulated the expression of IL-1α, -6 and TNF-α, which are inflammatory factors that impair nerve regeneration (Bastien and Lacroix, 2014). IL-12 was first found to be downregulated by NP-1. There were no significant differences in IL-1β and -10 between the NP-1 group and the blank group in vivo and in vitro. These results are inconsistent with those published by Brook and Maeda, which might be explained by differences in the dose of NP-1 solution used (Brook et al., 2016; Maeda et al., 2016). IL-1α, -1β, -6, -10 and TNF-α are mainly secreted by macrophages (Rossi et al., 2021). Thus, the present findings indicate that NP-1 altered some macrophage functions. NP-1 regulation of inflammatory factor secretion in vivo and in vitro suggests that NP-1 may inhibit macrophage polarization to the M1 phenotype. Indeed, immunohistochemical assay showed that NP-1 did not polarize macrophages toward the M1 phenotype or reduce the maturation of macrophages.

There were some limitations in this research. We elucidated the relationship between NP-1 and macrophages, but the mechanisms by which NP-1 regulates macrophages have not been clarified. NP-1 affects many different macrophage functions. The research on the regulatory mechanism is bound to be a voluminous work that we will do in the future.

In conclusion, NP-1 was shown for the first time to accelerate Wallerian degeneration by enhancing the proliferation, phagocytosis, and migration capabilities of macrophages in this study. We also showed NP-1 regulation of inflammatory factor expression in macrophages. This study has provided preliminary theoretical support for the investigation of NP-1 in the treatment of peripheral nerve injury.

Funding Statement

Funding: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 32371048 (to YK); the Peking University People's Hospital Research and Development Funds, No. RDX2021-01 (to YK); and the Natural Science Foundation of Beijing, No. 7222198 (to NH).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article are reported.

Data availability statement: No additional data are available.

C-Editors: Li JY, Zhao M; S-Editor: Li CH; L-Editors: McCollum L, Li CH, Song LP; T-Editor: Jia Y

References

- Aarbiou J, Ertmann M, van Wetering S, van Noort P, Rook D, Rabe KF, Litvinov SV, van Krieken JH, de Boer WI, Hiemstra PS. Human neutrophil defensins induce lung epithelial cell proliferation in vitro. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;72:167–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarbiou J, Verhoosel RM, Van Wetering S, De Boer WI, Van Krieken JH, Litvinov SV, Rabe KF, Hiemstra PS. Neutrophil defensins enhance lung epithelial wound closure and mucin gene expression in vitro. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;30:193–201. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0267OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastien D, Lacroix S. Cytokine pathways regulating glial and leukocyte function after spinal cord and peripheral nerve injury. Exp Neurol. 2014;258:62–77. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook M, Tomlinson GH, Miles K, Smith RW, Rossi AG, Hiemstra PS, van't Wout EF, Dean JL, Gray NK, Lu W, Gray M. Neutrophil-derived alpha defensins control inflammation by inhibiting macrophage mRNA translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:4350–4355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1601831113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputo JL. Biosafety procedures in cell culture. J Tissue Cult Methods. 1988;11:223–227. [Google Scholar]

- Catapano J, Zhang J, Scholl D, Chiang C, Gordon T, Borschel GH. N-acetylcysteine prevents retrograde motor neuron death after neonatal peripheral nerve injury. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139:1105e–1115e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000003257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFrancesco-Lisowitz A, Lindborg JA, Niemi JP, Zigmond RE. The neuroimmunology of degeneration and regeneration in the peripheral nervous system. Neuroscience. 2015;302:174–203. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groeneveld TW, Ramwadhdoebe TH, Trouw LA, van den Ham DL, van der Borden V, Drijfhout JW, Hiemstra PS, Daha MR, Roos A. Human neutrophil peptide-1 inhibits both the classical and the lectin pathway of complement activation. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:3608–3614. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y, Yang W, Zhang K, Qiu S, Xu J, Wang C, Chai Y. Nanofiber arrangement regulates peripheral nerve regeneration through differential modulation of macrophage phenotypes. Acta Biomater. 2019;83:291–301. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Jones S, Jia X. Stem cell transplantation for peripheral nerve regeneration: current options and opportunities. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:94. doi: 10.3390/ijms18010094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamali T, Fischer J, Farrell S, Baldridge WH, Zinser G, Chauhan BC. Simultaneous in vivo confocal reflectance and two-photon retinal ganglion cell imaging based on a hollow core fiber platform. J Biomed Opt. 2018;23:1–4. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.23.9.091405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kou Y, Yu F, Yuan Y, Niu S, Han N, Zhang Y, Yin X, Xu H, Jiang B. Effects of NP-1 on proliferation, migration, and apoptosis of Schwann cell line RSC96 through the NF-κB signaling pathway. Am J Transl Res. 2020;12:4127–4140. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lago N, Rodriguez FJ, Guzman MS, Jaramillo J, Navarro X. Effects of motor and sensory nerve transplants on amount and specificity of sciatic nerve regeneration. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:2800–2812. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JK, Geoffroy CG, Chan AF, Tolentino KE, Crawford MJ, Leal MA, Kang B, Zheng B. Assessing spinal axon regeneration and sprouting in Nogo-, MAG-, and OMgp-deficient mice. Neuron. 2010;66:663–670. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu CY, Santosa KB, Jablonka-Shariff A, Vannucci B, Fuchs A, Turnbull I, Pan D, Wood MD, Snyder-Warwick AK. Macrophage-derived vascular endothelial growth factor-A is integral to neuromuscular junction reinnervation after nerve injury. J Neurosci. 2020;40:9602–9616. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1736-20.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv D, Zhou L, Zheng X, Hu Y. Sustained release of collagen VI potentiates sciatic nerve regeneration by modulating macrophage phenotype. Eur J Neurosci. 2017;45:1258–1267. doi: 10.1111/ejn.13558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda T, Sakiyama T, Kanmura S, Hashimoto S, Ibusuki K, Tanoue S, Komaki Y, Arima S, Nasu Y, Sasaki F, Taguchi H, Numata M, Uto H, Tsubouchi H, Ido A. Low concentrations of human neutrophil peptide ameliorate experimental murine colitis. Int J Mol Med. 2016;38:1777–1785. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2016.2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midha R, Grochmal J. Surgery for nerve injury: current and future perspectives. J Neurosurg. 2019;130:675–685. doi: 10.3171/2018.11.JNS181520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuzawa S, Ikeguchi R, Aoyama T, Takeuchi H, Yurie H, Oda H, Ohta S, Ushimaru M, Ito T, Tanaka M, Kunitomi Y, Tsuji M, Akieda S, Nakayama K, Matsuda S. The efficacy of a scaffold-free bio 3D conduit developed from autologous dermal fibroblasts on peripheral nerve regeneration in a canine ulnar nerve injury model: a preclinical proof-of-concept study. Cell Transplant. 2019;28:1231–1241. doi: 10.1177/0963689719855346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan S, Hernández IC, Wang W, Yin K, Sundback CA, Wegst UGK, Jowett N. Fluorescent reporter mice for nerve guidance conduit assessment: a high-throughput in vivo model. Laryngoscope. 2018;128:E386–392. doi: 10.1002/lary.27439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller CA, Markovic-Lipkovski J, Klatt T, Gamper J, Schwarz G, Beck H, Deeg M, Kalbacher H, Widmann S, Wessels JT, Becker V, Muller GA, Flad T. Human alpha-defensins HNPs-1, -2, and -3 in renal cell carcinoma: influences on tumor cell proliferation. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:1311–1324. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62558-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CJ, Foster BA, Mannis MJ, Selsted ME, Reid TW. Defensins are mitogenic for epithelial cells and fibroblasts. J Cell Physiol. 1993;155:408–413. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041550223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council . 8th. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. [Google Scholar]

- Nozdrachev AD, Kolosova LI, Moiseeva AB, Ryabchikova OV. The role of defensin NP-1 in restoring the functions of an injured nerve trunk. Neurosci Behav Physiol. 2006;36:313–315. doi: 10.1007/s11055-006-0018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Percie du Sert N, Hurst V, Ahluwalia A, Alam S, Avey MT, Baker M, Browne WJ, Clark A, Cuthill IC, Dirnagl U, Emerson M, Garner P, Holgate ST, Howells DW, Karp NA, Lazic SE, Lidster K, MacCallum CJ, Macleod M, Pearl EJ, et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 2020;18:e3000410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi JF, Lu ZY, Massart C, Levon K. Dynamic immune/inflammation precision medicine: the good and the bad inflammation in infection and cancer. Front Immunol. 2021;12:595722. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.595722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotshenker S. Microglia and macrophage activation and the regulation of complement-receptor-3 (CR3/MAC-1)-mediated myelin phagocytosis in injury and disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2003;21:65–72. doi: 10.1385/JMN:21:1:65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang Q, Sun D, Chen Z, Zhao W. NGF and PI3K/Akt signaling participate in the ventral motor neuronal protection of curcumin in sciatic nerve injury rat models. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;103:1146–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.04.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarhane KA, Qiu C, Harris TGW, Hanwright PJ, Mao HQ, Tuffaha SH. Translational bioengineering strategies for peripheral nerve regeneration: opportunities, challenges, and novel concepts. Neural Regen Res. 2023;18:1229–1234. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.358616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susaki EA, Tainaka K, Perrin D, Yukinaga H, Kuno A, Ueda HR. Advanced CUBIC protocols for whole-brain and whole-body clearing and imaging. Nat Protoc. 2015;10:1709–1727. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda HR, Ertürk A, Chung K, Gradinaru V, Chédotal A, Tomancak P, Keller PJ. Tissue clearing and its applications in neuroscience. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2020;21:61–79. doi: 10.1038/s41583-019-0250-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg RH, Faber-Krol MC, van Wetering S, Hiemstra PS, Daha MR. Inhibition of activation of the classical pathway of complement by human neutrophil defensins. Blood. 1998;92:3898–3903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters M, VandeVord P, Van Dyke M. Keratin biomaterials augment anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype in vitro. Acta Biomater. 2018;66:213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Bai L, Chen Y, Fan C, Hu Z, Xu H, Jiang B. Effect of mutated defensin NP-1 on sciatic nerve regeneration after transection--A pivot study. Neurosci Lett. 2016;617:283–287. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan T, Feng Y, Zhai Q. Axon degeneration: Mechanisms and implications of a distinct program from cell death. Neurochem Int. 2010;56:529–534. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu F, Yuan Y, Xu H, Niu S, Han N, Zhang Y, Yin X, Kou Y, Jiang B. Neutrophil peptide-1 promotes the repair of sciatic nerve injury through the expression of proteins related to nerve regeneration. Nutr Neurosci. 2022;25:631–641. doi: 10.1080/1028415X.2020.1792617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan YS, Yu F, Niu SP, Lu H, Kou YH, Xu HL. Combining CUBIC optical clearing and Thy1-YFP-16 mice to observe morphological axon changes during wallerian degeneration. Curr Med Sci. 2021;41:944–952. doi: 10.1007/s11596-021-2438-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan YS, Niu SP, Yu F, Zhang YJ, Han N, Lu H, Yin XF, Xu HL, Kou YH. Intraoperative single administration of neutrophil peptide 1 accelerates the early functional recovery of peripheral nerves after crush injury. Neural Regen Res. 2020;15:2108–2115. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.282270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Jiang M, Fang Y. The drama of Wallerian degeneration: the cast, crew, and script. Annu Rev Genet. 2021;55:93–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-071819-103917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Fang XX, Li QC, Pi W, Han N. Reduced graphene oxide-embedded nerve conduits loaded with bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles promote peripheral nerve regeneration. Neural Regen Res. 2023;18:200–206. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.343889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Beuerman RW, Huang L, Barathi A, Foo YH, Li SF, Chew FT, Tan D. Proteomic analysis of rabbit tear fluid: Defensin levels after an experimental corneal wound are correlated to wound closure. Proteomics. 2007;7:3194–3206. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond RE, Echevarria FD. Macrophage biology in the peripheral nervous system after injury. Prog Neurobiol. 2019;173:102–121. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]