Abstract

Shaking hands is a fundamental form of social interaction. The current study used high-definition cameras during a university graduation ceremony to examine the temporal sequencing of eye contact and shaking hands. Analyses revealed that mutual gaze always preceded shaking hands. A follow up investigation manipulated gaze when shaking hands, and found that participants take significantly longer to accept a handshake when an outstretched hand precedes eye contact. These findings demonstrate that the timing between a person's gaze and their offer to shake hands is critical to how their action is interpreted.

Keywords: Social cognition, perception, attention, eye movements

Researchers are increasingly interested in real-world social interactions and how the gaze of one person may impact another (e.g., Capozzi & Ristic, 2018; Dalmaso et al., 2020; Frischen et al., 2007; Richardson & Gobel, 2015; Stephenson et al., 2021). This collective body of work indicates that humans are exquisitely sensitive to where people are looking (Hessels, 2020), with for example one person's gaze affecting where another person attends (Langton & Bruce, 1999), what they understand (Wohltjen & Wheatley, 2021), and when they speak (Kendon, 1967).

Generally overlooked, however, is how one person's gaze is critical to how their own behaviour is interpreted by others? We investigated this issue with respect to the invitation to shake hands (Institutional Review Board approval (H10-00527) for the data reported in this article). Not only is shaking hands a social behaviour observed around the world, but its importance to social interactions has been highlighted in recent years both by humans’ struggles for a suitable replacement during the pandemic (e.g., the touching of elbows), and by the awkward, comical, and often violent handshakes of former president Donald Trump, something that many of us may have to endure again as the 2024 US election date approaches.

Our university, like many schools, holds a graduation at the end of the academic year during which each student walks across a stage, shakes the hand of a senior administrator (in our case the Chancellor), and receives their degree. Using two high-definition cameras, we filmed these actions of 177 graduating students. For each student, we coded eight different events: the calling of a student's name, the start of their walk across the stage, when the Chancellor first looks up at the student, when the student first looks at the Chancellor, when the Chancellor extends a hand towards the student, when the student extends their hand to the Chancellor, when the two hands make contact, and when the hands separate.

Analyses of these recordings revealed three consistent patterns that suggested a critical role of eye gaze. First, the Chancellor and the student always looked at one another before either of them extended their hands. Second, the Chancellor normally extended their hand first (82.5% of the time). Third, and most critically, while the relative timing of the first two events varied considerably from one student to the next, the timing between the Chancellor's extension of a hand and a student's reciprocal response was exquisitely short and stable, with the sequence of hand offerings occurring within a second of one another (M = .40 s, SD = .45 s). As a result we chose to use this reliable temporal sequence to understand the role of eye gaze when shaking hands in a follow-up experimental investigation.

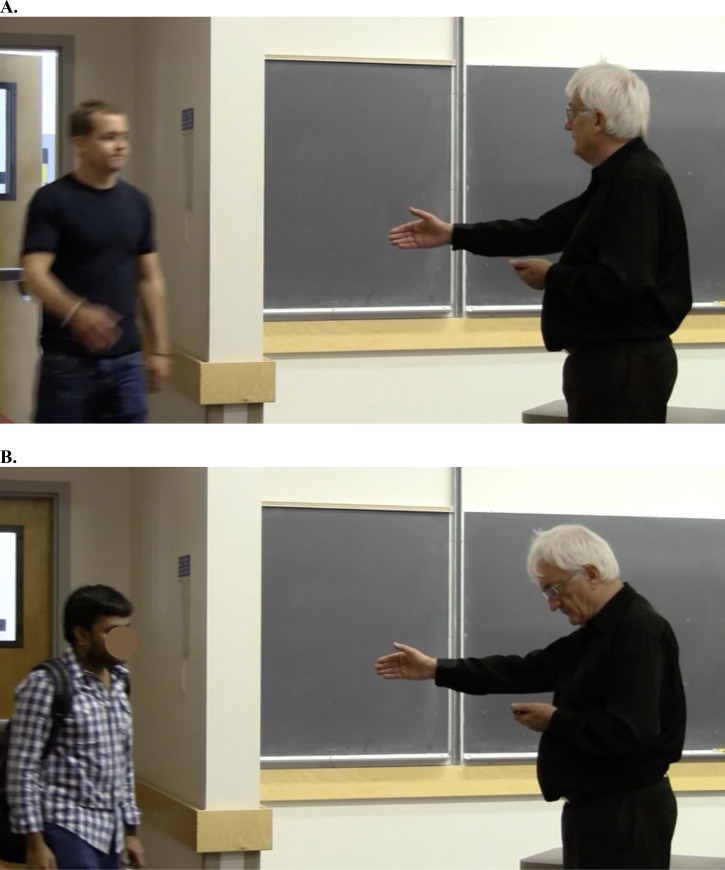

We recruited 48 students (26 female) outside a university classroom. After consenting to participate, each individual was asked to meet the investigator by entering through a classroom door. The investigator was standing a natural distance (∼3 m) on the other side of the door looking down at their phone. Once the individual entered the room the researcher either (a) looked up towards the individual, and then approximately 1 s later extended his hand or (b) extended his hand and then approximately 1 s later looked up towards the individual. Two high-definition cameras discretely placed at the back of the classroom recorded the interactions (see Figure 1). Drawing from the first study, the key measure was the time from the completion of the first hand extension to the completion of the second hand extension. After excluding one participant who walked past the investigator and his outstretched hand before circling back, the results revealed that the time between the investigator's hand extension and the individual's hand extension was significantly shorter when the investigator's gaze preceded (0.92 s) rather than followed (1.27 s) the offer of his hand, F(1,45) = 6.15, p = .017. Note that in addition to the response delay that arose when the experimenter's gaze lagged behind his hand extension, more than two-thirds of the participants (71%) only extended their hand to the experimenter after he looked towards them. This evidence suggests that gaze not only speeds up the recognition of a handshake, but it may also be necessary for many to recognize a handshake.

Figure 1.

Screenshots from one of the cameras illustrating the two experimental conditions. (A) The investigator (R) extends a hand after making eye contact. (B) The hand–eye sequence is reversed. Note that in (A) the individual (L) is beginning to shake hands. In (B) this is not the case.

Collectively, the data from these two studies provide real-world observational and experimental evidence that the temporal sequence between a person's gaze and hand action has a significant effect on how other individuals interpret that individual's behaviour. Specifically, looking towards another person before extending one's hand appears to play a key role in a hand extension being perceived as a social invitation to shake hands. Therefore, not only do people use gaze direction to interpret where others are looking or what they are prioritizing in the surrounding world, but the temporal sequence of gaze and behaviour may be critical to how others interpret a person's behaviour. Indeed, informal debriefing of the participants revealed that when the experimenter's hand preceded his gaze, they tended to interpret the hand as directive (e.g., “please move over there”) rather than as an invitation to shake hands. Confirming this interpretation, and extending the present work to other domains where the temporal coordination of gaze and behaviour may be critical to how behaviours are perceived (e.g., when passing an item from one person to another), promises to be an intriguing avenue for future investigation.

Footnotes

Author Contribution(s): Alan Kingstone: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Esther Walker: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Writing – original draft.

Shahrazad Amin: Formal analysis; Methodology; Project administration; Writing – review & editing.

Walter F. Bischof: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (grant number RGPIN-2022-03079).

ORCID iD: Alan Kingstone https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0025-855X

References

- Capozzi F., Ristic J. (2018). How attention gates social interactions. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1426(1), 179–198. 10.1111/nyas.13854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalmaso M., Castelli L., Galfano G. (2020). Social modulators of gaze-mediated orienting of attention: A review. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 27(October 2020), 833–855. 10.3758/s13423-020-01730-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frischen A., Bayliss A. P., Tipper S. P. (2007). Gaze cueing of attention: Visual attention, social cognition, and individual differences. Psychological Bulletin, 133(4), 694–724. 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessels R. S. (2020). How does gaze to faces support face-to-face interaction? A review and perspective. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 27(October 2020), 856–881. 10.3758/s13423-020-01715-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendon A. (1967). Some functions of gaze-direction in social interaction. Acta Psychologica, 26, 22–63. 10.1016/0001-6918(67)90005-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langton S. R., Bruce V. (1999). Reflexive visual orienting in response to the social attention of others. Visual Cognition, 6(5), 541–567. 10.1080/135062899394939 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson D. C., Gobel M. S. (2015). Social attention. In Fawcett J. M., Risko E. F., Kingstone A. (Eds.), The handbook of attention (pp. 349–367). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson L. J., Edwards S. G., Bayliss A. P. (2021). From gaze perception to social cognition: The shared attention system. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(3), 553–576. 10.1177/1745691620953773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohltjen S., Wheatley T. (2021). Eye contact marks the rise and fall of shared attention in conversation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 118(37), e2106645118. 10.1073/pnas.2106645118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]