Abstract

Microglia are resident immune cells of the central nervous system (CNS) and play key roles in brain homeostasis. During anesthesia, microglia increase their dynamic process surveillance and interact more closely with neurons. However, the functional significance of microglial process dynamics and neuronal interaction under anesthesia is largely unknown. Using in vivo two-photon imaging in mice, we show that microglia enhance neuronal activity after the cessation of isoflurane anesthesia. Hyperactive neuron somata are directly contacted by microglial processes, which specifically co-localize with GABAergic boutons. Electron microscopy-based synaptic reconstruction after two-photon imaging reveals that during anesthesia microglial processes enter into the synaptic cleft to shield GABAergic inputs. Microglial ablation or loss of microglial β2-adrenergic receptors prevents post-anesthesia neuronal hyperactivity. Our study demonstrates a previously unappreciated function of microglial process dynamics, which enable microglia to transiently boost post-anesthesia neuronal activity by physically shielding inhibitory inputs.

Introduction

Microglia, the resident immune cells of the central nervous system (CNS), are highly dynamic and constantly survey the brain environment1–3. Microglia maintain brain homeostasis and can regulate neuronal circuits through their dynamic process surveillance and subsequent interactions with neurons. Microglia surveil neuronal activity by contacting pre- and post-synaptic elements, monitoring their activity, and pruning synapses4–8. Particularly, microglia can dampen neuronal hyperactivity during seizures and epilepsy9, 10. Dampening neuronal activity involves the rapid degradation of ATP into adenosine to reduce presynaptic activity11. Potentially, ATP regulation most readily occurs at somatic purinergic junctions between microglial processes and neurons9, 12. As complex mechanisms used by microglia to reduce neuronal hyperactivity have been elucidated, much remains unknown about the functional significance of microglia–neuron interactions during hypoactive periods, such as anesthesia. In this study, we investigated the potential for microglia to also regulate neuronal activity during periods of neuronal hypoactivity using in vivo two-photon imaging combined with electron microscopy. We find that microglia can transiently boost neuronal activity, which manifests in the period following the cessation of isoflurane anesthesia. They do this by shielding axosomatic GABAergic synapses onto excitatory neurons during the anesthesia phase.

Results

Neuronal hyperactivity during emergence from anesthesia.

Seizures and epileptiform cortical activity can occur after the cessation of general anesthesia, termed the ‘emergence’ or ‘recovery’ period, in human patients13 and in rodents14. To directly test for neuronal hypersynchrony during the emergence from anesthesia, we employed in vivo two-photon microscopy in mice to observe neuronal Ca2+ activity in the awake baseline state, during 30 minutes of isoflurane anesthesia, and during emergence from general anesthesia (Fig. 1a–c). Excitatory neurons in layer II-III of somatosensory cortex were virally transfected with a genetically-encoded calcium indicator (AAV9.CaMKII.GCaMP6s). In the awake state, excitatory neurons exhibited spontaneous Ca2+ activity, which was largely silenced by isoflurane anesthesia (Fig. 1c,d; Supplementary Video 1). During emergence from anesthesia, 48.2% of excitatory neurons (Fig. 1d,e) increased their spontaneous firing above baseline levels. A smaller percentage of neurons (22.2%) reduced their firing relative to awake baseline, and 29.6% showed no substantial change. Increased neuronal Ca2+ activity manifests as both greater maximum calcium signal amplitude and longer calcium transient duration, culminating in a much greater signal area, which could be observed as early as 15 minutes after the cessation of anesthesia (Fig. 1f–h). This period of hyperactivity gradually returned to initial, awake baseline levels over 60 minutes. Additionally, there was no observed sex difference in post-anesthesia neuronal hyperactivity (Extended Data Fig. 1a-c). Consistent with neuronal hyperactivity during emergence from anesthesia, we found that sensory perception was sensitized in this period, as indicated by a lower pain reflex threshold in a von Frey test (Fig. 1i). In addition, we observed an increase in animal locomotion coinciding with the peak of neuronal hyperactivity during emergence from anesthesia (Fig. 1j,k). These results demonstrate that anesthesia can result in a transient period of neuronal hyperactivity and mechnical sensitization during emergence from anesthesia.

Fig. 1: Neuronal hyperactivity occurs during emergence from general anesthesia.

a, Outline of in vivo two-photon calcium imaging with simultaneous mouse locomotion tracking. b, Schematic diagram of the experimental timeline. c, Representative images of neuronal calcium activity from the somatosensory cortex before, during, and after anesthesia (Scale bar: 20 μm). d, Classification of neuronal calcium activity and representative ΔF/F calcium traces. Neurons with increased activity during emergence compared to awake baseline are shown in red, while those with no change are shown in green, and those with decreased activity are shown in blue. Background color in calcium traces shows awake (gray), isoflurane (pink), and emergence (blue) periods. e, Percentage of neurons displaying these activity changes in emergence compared to awake baseline. Exact criteria and methodology are provided in the methods (n = 4 mice). f–h, Maximum amplitude (ΔF/F, f), active time (time of ΔF/F>0.5, g), and signal area (ΔF/F·s, h) for neuronal calcium traces at each time point. p = 0.0005 (Awake versus Emergence 15 min), p = 0.0053 (30 min), p = 0.0387 (45 min), p = 0.2013 (60 min), F(4, 20) = 11.64 (f). p = 0.0371 (Awake versus Emergence 15 min), p = 0.0002 (30 min), p = 0.0069 (45 min), p = 0.0371 (60 min), F(4, 20) = 4.748 (g). p = 0.0441 (Awake versus Emergence 15 min), p = 0.0012 (30 min), p = 0.0441 (45 min), p = 0.0441 (60 min), F(5, 24) = 16.10 (h). Solid line represents the mean ± SEM, while dashed lines indicate an individual animal (n = 5 mice). i, Threshold for paw withdrawal in the von Frey filament test (n = 10 mice). p < 0.0001 (Awake versus Emergence 30 min), p = 0.0007 (60 min) F(2, 27) = 1.236. j, Representative locomotor movement of mice using a magnetic-based tracking platform. Mouse movement is displayed in blue, while all other colors distinguish platform zones. k, Changes in neuronal calcium activity (mean ± SEM of ΔF/F signal area, green) and mouse locomotion activity (activity index, gray) throughout experimental phases (n = 4 mice). l, Representative images of microglial morphology and surveillance territory during each experimental phase (Scale bar: 10 μm). m, Time-course changes in microglial territory (gray) overlaid with corresponding changes in neuronal calcium activity (ΔF/F, green). Territory area throughout the experiment was normalized to the awake baseline start. n, Time-course changes in microglial territory (n = 6 mice). p = 0.0378 (Awake versus Isoflurane 15 min), p < 0.0001 (Isoflurane 30 min), p < 0.0001 (Emergence 15 min), p < 0.0001 (Emergence 30 min), p < 0.0001 (Emergence 45 min), p = 0.0249 (Emergence 60 min), F(6, 35) = 1.486. In all graphs, each point or dashed line indicates data from an individual animal, while bars or solid lines with error bars indicate the mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak (f,g,h,n), Tukey (i) post-hoc test; n.s., not significant; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001. Experiments were repeated four times (a–e), five times (f–h), six times (n), and ten times (i) independently with similar results obtained.

Microglial processes extend outward to expand their parenchymal surveillance territory during anesthesia. Anesthesia is known to reduce adrenergic tone during anesthesia by inhibiting locus coeruleus activity15, 16. It is unclear how microglial processes would respond during the period of neuronal hyperactivity during emergence from anesthesia. To image microglial process dynamics across phases of anesthesia, we utilized Cx3Cr1GFP/+ mice. As expected, microglial territory gradually increased during isoflurane anesthesia. Microglial territory area was maintained but did not further expand during emergence from anesthesia (Fig. 1l–n, and Supplementary Video 2 and 3). Again, no sex difference was observed in relation to the increased microglial process surveillance during emergence from anesthesia (Extended Data Fig. 1d,e). Thus, neuronal hyperactivity does not engender any additional increase in microglial process motility or surveillance territory during the early phase of emergence from isoflurane anesthesia.

Microglia required for neuronal hyperactivity during emergence.

Greater microglia–neuron interaction under anesthesia could potentially regulate neuronal activity. The impact of these interactions could manifest as neuronal hyperactivity during the emergence period. To test this idea, we employed microglia ablation approaches combined with neuronal Ca2+ imaging. Mice were fed a chow containing PLX3397, a Csf1 receptor inhibitor, for 3 weeks. At the time of experimentation, approximately 98% of cortical microglia were ablated compared to wild-type mice fed control diet, as confirmed by IBA1 staining (Fig. 2a,b). We imaged neuronal Ca2+ activity across experimental phases (awake baseline, isoflurane anesthesia, and emergence) in mice with and without microglia (Fig. 2c). Mice fed with control diet still displayed neuronal hyperactivity during the 30-minute emergence period. However, mice fed with PLX3397 failed to display neuronal Ca2+ hyperactivity during emergence from anesthesia when compared to control chow fed mice (Fig. 2d–f, Extended Data Fig. 2a–g, and Supplementary Video 4). Microglia-ablated mice also did not show behavioral sensitization (specifically, mechanical hypersensitivity) during emergence from anesthesia (Fig. 2g). It should be noted however, that there was a significant increase in baseline pain sensitivity after microglia ablation (‘Awake’); consistent with this, baseline Ca2+ activity in somatosensory cortex was elevated after microglia ablation (Fig. 2g, Extended Data Fig. 2h–m). Together, these results suggest that microglia are required for neuronal hyperactivity and pain sensitization during emergence from general anesthesia.

Fig. 2: Microglial depletion abolishes the increase of neuronal activity during emergence.

a, Experimental timeline of microglia ablation and two-photon imaging of neuronal Ca2+ activity before and after general anesthesia. b, IBA1 immunostaining of microglial density in mice fed with a control chow (Control, left panel) and a PLX3397-containing chow (PLX, middle panel) in the cortex (blue for DAPI and red for IBA1). Graph shows significantly decreased IBA1+ cells in PLX-treated mice (right) (n = 6 control mice, n = 7 PLX-treated mice, two-sided unpaired t-test, p < 0.0001, t(11) = 21.42). Scale bar: 50 μm. c, Representative images of neuronal Ca2+ activity across experimental phases (Awake, Isoflurane and Emergence 30 min) in mice before (left panels) and after microglia ablation (right panels). Scale bar: 50 μm. d, Graph shows maximum amplitude (ratio) of neuronal Ca2+ active time before and after ablation (n = 10 mice each group, p < 0.0001 (Before ablation versus After ablation, t(54) = 7.528). e, Graph shows time active (ratio) of neuronal Ca2+ activity before and after ablation. p < 0.0001 (Before ablation versus After ablation, t(54) = 5.986). f, Graph shows ΔF/F signal area (ratio) of neuronal Ca2+ activity before and after ablation. p < 0.0001 (Before ablation versus After ablation, t(54) = 5.271). g, Graph shows reduced mechanical hypersensitivity during the emergence from anesthesia (30 min) in microglia ablated mice (n = 10 before ablation, n = 9 after ablation mice, Before ablation versus After ablation, p = 0.0017 (Awake), p < 0.0001 (Emergence 30 min), p < 0.0001 (Emergence 60 min), F(2, 51) = 118.1. In all graphs, each point or dashed lines indicates data from an individual animal, while columns or solid lines and error bars show the mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak (d,e,f) and Tukey (g) post-hoc test; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001. All experiments were repeated multiple times using different mice independently with similar results obtained.

Increased microglial contacts correlates with neuronal hyperactivity.

To examine the possible correlation between microglial process dynamics and neuronal hyperactivity, we visualized neurons and their Ca2+ activity with GCaMP6s and tdTomato viral transfection. In addition, microglial processes were visualized using Cx3cr1GFP/+ mice. During anesthesia, microglial processes increased their contact with neuron somata and exhibited bulbous process endings at their contact sites with neuronal somata (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Video 5). During the awake baseline period, 83.7% of neuronal somata had one or no microglial process contact sites, and 16.3% of neuronal somata had two or more contact sites (Fig. 3b). During isoflurane anesthesia, microglial processes contact with neuronal somata increased overall. In order to quantify the increase of contacts induced by anesthesia, we compared the number of neurons with two or more contacts against the average baseline neuron with 0–1 contacts. At the population level, some neurons retained zero or one microglial contact during anesthesia, similar to baseline levels (termed ‘low contact’), whereas in other neurons microglial processes formed two or more contacts with somata during anesthesia (termed ‘high contact’). Specifically, 76.8% of neurons had high contact during anesthesia, compared to 16.3% of high contact in the awake baseline condition (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Video 5). During anesthesia, the duration of microglial process contacts with neuronal somas also increased (Extended Data Fig. 3a–c). Bulbous ending contact with neuronal dendrites were similarly increased (Extended Data Fig. 3d–f). The velocity of bulbous endings on the neuronal somata decreased during contact (Extended Data Fig. 3g), while normal process tip velocity was increased during anesthesia (Extended Data Fig. 3h,i). In tracking neuronal activity through the various phases of imaging, we found that hyperactive neurons had the highest number of microglial contacts during emergence from anesthesia (Fig. 3c). Moreover, neurons with low contact showed slower recovery from anesthesia during emergence (Fig. 3d). Thus, microglial contacts with neuronal somata during anesthesia strongly correlated with later hyperactivity during emergence from anesthesia (Fig. 3e).

Fig. 3: Increased microglial process contacts correlate with neuronal hyperactivity during emergence.

a, Representative images of microglia (green) and CaMKII neuron (red) interactions in the awake baseline, anesthesia, and anesthesia recovery periods. White arrowheads indicate contact sites (Scale bar: 5 μm). b, Percentage of CaMKII neurons with soma contact from microglial processes in the awake, isoflurane, and emergence phases (n = 4 mice). p = 0.0016 (High contact, Awake versus Isoflurane, t(18) = 4.929), p = 0.9954 (High contact, Isoflurane versus Emergence, t(18) = 1.065). c,d, Overlay of GCaMP6s neuronal calcium activity (ΔF/F, green) and the number of microglial process contacts (red) with neuronal somata across anesthesia phases, separated by neurons with higher microglial contact (c) and lower microglial contact (d). Each trend line represents the mean ± SEM. e, Neuronal calcium signal area in the 30-minute emergence phase for somata with low or high microglial contact during anesthesia (Left: p = 0.0210, Low contact versus High contact, t(34) = 2.420). The ratio of neuronal activity (signal area) in the awake baseline compared to emergence from anesthesia (Right: p = 0.0043, Low contact versus High contact, t(29) = 3.098). Dataset includes 13 neurons with low contact and 23 neurons with high contact from 8 mice. f, Representative images of microglial processes and bulbous tip endings (white square) at the beginning (green) and end (purple) of each study phase: awake baseline, anesthesia, and emergence. Inset: Criteria for a bulbous tip ending on a microglial process (scale bar: 10 μm for main panels; 1 μm for inset). g, Number of bulbous tip processes present on microglia across experimental phases. Dashed lines indicate data from an individual animal, while solid line and error bars show the mean ± SEM (n = 11 microglia from 5 mice). p < 0.0001 (Awake versus Isoflurane), p < 0.0001 (Awake versus Emergence 30 min), p = 0.0035 (Awake versus Emergence 60 min), F(3, 40) = 1.930. h, Representative immunofluorescent images of IBA1 microglia and NeuN neurons in fixed tissue prepared from mice across experimental phases. Inset shows microglial bulbous tip endings contacting NeuN somata. Scale bar: 20 μm in main panels, 2 μm in inset. i, Quantification of microglial bulbous tip endings contacting NeuN per microglia across experimental phases (n = 6 mice). p < 0.0001 (Awake versus Isoflurane), p = 0.0060 (Awake versus Emergence), p = 0.0043 (Isoflurane versus Emergence), F(2, 15) = 0.4003. Each point indicates data from an individual neuron (e) or animal (b,i), columns with error bars indicate the mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak post-hoc test (b), one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test (g,i), unpaired t-test (e); n.s., not significant; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001. All experiments were repeated multiple times using different mice independently with similar results obtained.

Our results indicate that contacts by microglial bulbous endings may be important for emergence-induced neuronal hyperactivity. To further characterize the bulbous endings of microglia, we quantified these structures before, during, and after anesthesia. Bulbous endings were defined as having a process head diameter greater than twice the width of the neck portion (Fig. 3f). We found that microglial bulbous tip formation increased during anesthesia and peaked at 30 minutes into emergence from anesthesia (Fig. 3g). We then analyzed microglial bulbous endings with neurons by IBA1 and NeuN immunostaining in layer II-III of mouse somatosensory cortex. Indeed, we found that the number of microglial bulbous endings surrounding neurons increased during anesthesia and emergence (Fig. 3h,i). Together, these results demonstrate that microglia bulbous endings may represent a unique structure for neuronal interaction during anesthesia and are correlated with neuronal hyperactivity during emergence from anesthesia.

Microglial processes interact with GABAergic synapses.

To study how microglial contacts may promote neuronal activity, we assessed excitatory and inhibitory synapses present on a neuronal somata together with microglial processes. We used a VGAT antibody to label GABAergic synapses, VGLUT1 for glutamatergic synapses, NeuN for neuronal somata, and IBA1 for microglia in fixed cortical tissue. Interestingly, the colocalization of microglial bulbous endings with VGAT puncta was significantly increased during anesthesia and remained high in tissue fixed at 30 min into emergence from anesthesia (Fig. 4a,b and Extended Data Fig. 4a–c). Consistently, the percentage of neurons with colocalized VGAT puncta/microglial bulbous ending contacts were increased during anesthesia as well as emergence (Fig. 4c). We further quantified microglial process interactions with excitatory VGLUT1 puncta and found they were unaltered under anesthesia compared to baseline (Extended Data Fig. 4d,e). In Cx3cr1-GFP heterozygotes mice, we still detected an increase of co-localization between GFP+ microglial processes and VGAT puncta as well as an increased number of microglial bulbous endings during emergence from anesthesia (Extended Data Fig. 4f-h). Suggesting that haploinsufficiency of Cx3cr1 did not significantly impact microglial interaction with inhibitory synapses in this context. In addition to the contacts between microglial processes and neuronal somata, we also examined soma–soma interactions between microglia and CaMKII neurons, which are also known to regulate neuronal activity during developmental seizures17. However, we did not observe any change in soma–soma interactions before or after anesthesia (Extended Data Fig. 4i,j). We then assessed whether microglia processes may phagocytose inhibitory inputs. To this end, we counted VGAT puncta surrounding neuronal soma, and found no change in the number of VGAT puncta 24 hours after anesthesia compared to baseline, suggesting that GABAergic synapses are not removed or pruned by microglia (Fig. 4d). Together, these results indicate that microglia may promote neuronal activity by interacting with GABAergic inputs without synapse elimination.

Fig. 4: Microglial processes interact with GABAergic boutons.

a, Representative immunofluorescent image of DAPI nuclei (blue), IBA1 microglial processes (green), NeuN nuclei (white), and VGAT puncta (red) in cortical tissue prepared 30 min after anesthetic emergence. White arrows in main panel and orthogonal panels indicate sites of microglial bulbous tip contact with VGAT terminals (Scale bar: 2 μm). b, Percentage of IBA1 processes co-localizing with VGAT puncta across experimental phases (n = 5 mice). p < 0.0001 (Awake versus Isoflurane), p = 0.0004 (Awake versus Emergence 30 min), p = 0.0043 (Awake versus Emergence 24 h), F(3, 16) = 18.16. c, Percentage of neurons with high contact (contacts more than 1) or low contact (0–1 contact) by microglial processes across experimental phases. d, Number of VGAT puncta per unit area across experimental phases (n = 5 mice). p = 0.6669 (Awake versus Isoflurane), p = 0.6669 (Awake versus Emergence 30 min), p = 0.8030 (Awake versus Emergence 24 h), F(3, 16) = 0.5970. e, Representative thresholded images or 3D space-filling models of microglia-VGAT interactions, including “No contact,” “partial contact,” “enwrapping,” or “full engulfment” (Scale bar: 2 μm). f, Percentage of microglial bulbous tip endings engaging in different types of VGAT interactions across experimental phases (n = 5 mice). p < 0.0001 (No contact, Awake versus Isoflurane), p = 0.0026 (No contact, Awake versus Emergence), p = 0.0073 (Enwrapped, Awake versus Isoflurane), F(3, 60) = 48.60. g, Representative super-resolution image of neurons (blue), IBA1 microglia (green), and PV boutons (red) (Scale bar: 10 μm in main panels, 1 μm in inset). h, Examples of microglial bulbous tip interactions with PV boutons across experimental phases (Scale bar: 5 μm). i, Kymograph displays microglial process contact time with CaMKII neuronal somata across experimental phases. j, Distribution of contact time across the whole experiment (n = 26 neurons from 5 mice). Dots represent individual mice (c,d,f) or individual neurons (j). Columns and error bars represent the mean ± SEM. One-way (b,d), or two-way (f) ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001. For a, g–h, experiments were repeated five times independently with similar results obtained.

We next examined details of the interaction between microglial bulbous endings and GABAergic synapses. To this end, we stained for the postsynaptic marker of GABAergic synapses, gephyrin, together with VGAT and microglia. Our results showed that the percentage of microglia contacting VGAT in close proximity to gephyrin was increased (11.5%, Awake; 15.0%, Isoflurane; 16.5%, Emergence; Extended Data Fig. 5a-d). Furthermore, we examined neuronal Kv2.1 distribution, which has been reported to be associated with somatic junction structures12. We found that neuronal Kv2.1 was present in the vicinity of microglial contact sites (Extended Data Fig. 5e-g). Notably, the percentage of microglial processes in proximity to VGAT and Kv2.1 increased after anesthesia and during emergence (Extended Data Fig. 5h). To understand how microglia may sense GABAergic transmission, we examined GABAB receptor expression, which was recently reported to mediate interactions between microglia and inhibitory synapses during development18 and to trigger microglial Ca2+ response19. Indeed, we found that GABAB receptor expression was enriched at the bulbous endings of microglia during anesthesia, as measured at the t=30 min timepoint (Extended Data Fig. 6).

To further investigate microglial interactions with GABAergic synapses, we took a closer look at how microglial bulbous endings interact with VGAT puncta during anesthesia, using confocal microscopy with high magnification Z-stacks. We classified interactions into four subtypes: VGAT puncta with no microglial contact (No contact), puncta with under 50% surface contact (Low Contact), contact with more than 50% surface area coverage (Enwrapped), and complete internalization (Engulfed) (Fig. 4e). This analysis indicated that full engulfed of VGAT puncta was rare; however, the percentage of VGAT puncta enwrapped by microglia increases during anesthesia (survey of n = 420 bulbous endings from 5 mice; Fig. 4f). Next, we used a combination of super-resolution microscopy and two-photon live imaging to visualize the direct interactions between microglia and inhibitory synapses. To this end, we transfected AAV9.CaMKII.GCaMP6s and AAV9.CAG.FLEX.tdTomato into parvalbumin (PV)Cre/+: Cx3cr1GFP/+ mice to simultaneously visualize neuronal Ca2+ activity, PV boutons, and microglia. Super-resolution microscopy confirmed that the tips of microglial bulbous endings wrapped around a portion of the PV-positive bouton rather than engage in complete engulfment (Fig. 4g). Interestingly, two-photon live imaging further revealed that the interaction of microglial bulbous endings with PV boutons was temporary and reversible (Fig. 4h and Supplementary Video 6). During the emergence phase, bulbous endings were retracted, and PV boutons remained intact. These results indicate that microglial processes engage in the partial enwrapping of GABAergic inputs during anesthesia.

Electron microscopy reconstruction reveals shielding of PV boutons.

Based on the increased microglial process contact with GABAergic boutons, we hypothesized that microglial bulbous endings promote neuronal activity by temporarily blocking inhibitory inputs. Consistent with this hypothesis, we found that contacts between microglial bulbous endings and PV boutons were strongly associated with neuronal hyperactivity during the emergence from anesthesia under two-photon in vivo imaging (Fig. 5a–b). Conversely, neurons that did not have microglial contact with PV boutons at their somata during anesthesia showed little hyperactivity during recovery from anesthesia. Thus, the percentage of hyperactive neurons during emergence from anesthesia is higher in those with microglial contact with PV boutons than those without the contact (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5: In vivo two-photon imaging followed by electron microscopy reconstruction reveals shielding of PV boutons.

a, Images of tdTomato-labelled PV boutons (AAV9.CAG.FLEX.tdTomato with PVCre/+), microglia (Cx3cr1GFP/+), and neurons (AAV-CaMKII-GCaMP6s) from in vivo two-photon microscopy during awake, anesthesia, and emergence (Scale bar: 10 μm). b, Percentage of neuronal somata displaying activity changes in emergence versus baseline as a function of microglial contact with PV boutons (n = 27 neurons from 7 mice. Chi-squared test: n.s., not significant; ****p < 0.0001) p = 6.6 × 10−13; (Increased, No contact versus Contact), p = 0.5453 (No change, No contact versus Contact), p = 4.4 × 10−15 (Decreased, No contact versus Contact). c, Two-photon in vivo imaging of microglia-PV bouton interactions adjacent to a neuronal soma, which was followed by electron microscopy reconstruction. d, 3-D serial reconstruction of a microglial process, PV bouton, and neuron at the ultrastructural level using SEM. For c–d, experiments were repeated three times independently with similar results obtained.

To investigate microglial bulbous endings and their contact with PV boutons at the ultrastructural level, we performed two-photon live imaging followed by electron microscopy. Clear examples of microglia–PV interactions under in vivo two-photon imaging were marked via laser branding20 (Fig. 5c and Extended Data Fig. 7a). The ultrastructure of these interactions was investigated at the nanoscale level using serial block-face scanning electron microscopy (SBF-SEM). Three-dimensional serial reconstruction indicates that the process tips of microglia can insert into a space between neuronal somata and PV boutons (Fig. 5d, Extended Data Fig. 7b-e and Supplementary Video 7). Thus, microglial bulbous endings were placed in a position to physically shield GABAergic synaptic inputs onto target neurons.

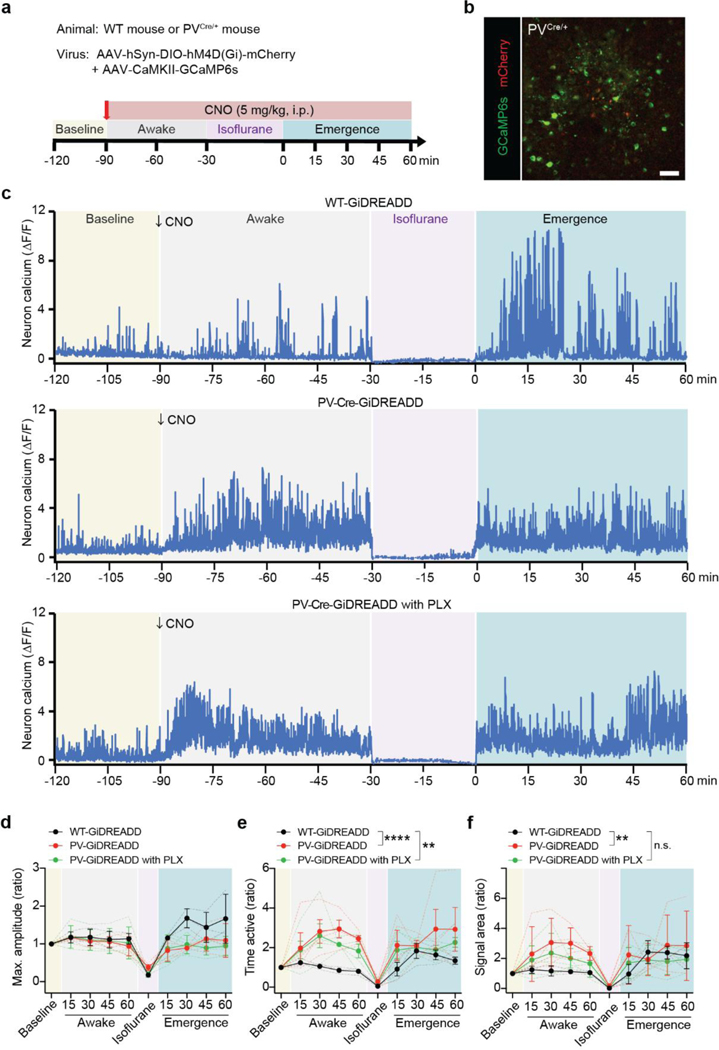

To further understand GABAergic shielding by microglia in regulating neuronal activity, we used chemogenetic approaches to directly inhibit PV neurons by activating Gi-DREADD via its ligand clozapine-N-oxide (CNO). To this end, we transfected AAV2-hSyn-DIO-hM4D(Gi)-mCherry into PVCre/+ mice to express Gi-DREADD in PV neurons (Extended Data Fig. 8a,b). In addition, we co-transfected AAV9.CaMKII.GCaMP6s to visualize Ca2+ activity in excitatory neurons. As expected, Gi-DREADD activation by CNO in PV neurons increased neuronal activity (Extended Data Fig. 8c-f). However, compared with controls (WT mice transfected with AAV2-hSyn-DIO-hM4D(Gi)-mCherry), there was no further increase in neuronal activity during emergence from anesthesia when PV neuronal activity was inhibited by CNO. Similarly, microglial ablation abolished neuronal hyperactivity during emergence, although it did not prevent the hyperactivity induced by Gi-READD in PV neurons (Extended Data Fig. 8c-f). These results suggest that GABAergic shielding by microglia is likely linked with neuronal hyperactivity.

Microglial β2 adrenergic receptors control neuronal hyperactivity

To clarify the mechanism underlying microglia’s ability to interact with axosomatic PV inputs, we investigated norepinephrine (NE) signaling. NE signaling to microglial β2-adrenergic receptors is known to restrain microglial process dynamics during wakefulness; under anesthesia, NE tone is likely reduced, allowing microglial processes to enhance their motility and territory surveillance15, 16. We first directly examined changes in NE tone during anesthesia and emergence in real time using an NE biosensor (AAV9.hsyn.NE2h; Fig. 6a)21. Indeed, NE concentrations decreased in the parenchyma of Layer II/III somatosensory cortex during anesthesia. During the emergence from anesthesia, NE levels underwent a strong rebound in the first 30 minutes after isoflurane cessation (Fig. 6b,c and Supplementary Video 8).

Fig. 6: NE and β2-adrenergic receptors control microglial process surveillance during anesthesia and emergence.

a, Schematic of local NE sensor transfection and cranial window surgery in the somatosensory cortex. b, Representative two-photon imaging of NE biosensor fluorescence in cortex during the awake baseline, anesthesia, and emergence (Scale bar: 20 μm). c, Quantification of NE sensor fluorescence (ΔF/F) across time periods (n = 5 mice, One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test). p = 0.0285 (Awake versus Isoflurane), p = 0.0223 (Awake versus Emergence 30 min), p = 0.4116 (Awake versus Emergence 60 min), F(4, 12) = 2.522. d, Experimental design for comparing microglial Adrb2 cKO mice (Cx3cr1CreER/+; Adrb2fl/fl) to controls (Cx3cr1CreER/+; Adrb2wt/wt) after tamoxifen recombination. e, Quantitative analysis of Adrb2 mRNA expression levels in Adrb2 cKO and control mice (n = 3 Cx3cr1CreER/+ with tamoxifen, n = 3 Cx3cr1CreER/+; Adrb2fl/fl, n = 4 Cx3cr1CreER/+; Adrb2fl/fl with tamoxifen). p = 0.0022 (Cx3cr1CreER/+; Adrb2fl/fl versus Cx3cr1CreER/+; Adrb2fl/fl with tamoxifen), F(5, 14) = 10.56. f, Representative images of microglial processes at the beginning (green) and end (purple) of each study phase: awake baseline, anesthesia, and emergence (Scale bar: 10 μm). g, Microglial process surveillance territory changes from awake baseline in Adrb2 cKO and WT control animals across experimental phases. Each trend line represents the mean ± SEM. h, Average microglial process outgrowth/extension during the awake and anesthesia periods for Adrb2 cKO and WT controls (n = 10 WT microglia and n = 12 cKO microglia from 4 mice). p = 0.034 (Adrb2 WT, Awake versus Isoflurane), p = 0.8809 (Adrb2 cKO, Awake versus Isoflurane), F(1, 40) = 4.038. i, 50% paw withdrawal thresholds for C57BL/6 WT mice, Adrb2 WT control mice, and Adrb2 cKO mice during von Frey filament testing during awake baseline and emergence from anesthesia (n = 4 C57BL/6 WT, n = 5 Adrb2 WT, n = 5 Adrb2 cKO mice). p < 0.0001 (Emergence 30 min, C57BL/6 WT mice versus Adrb2 cKO mice) p < 0.0001 (Emergence 30 min, Adrb2 WT control mice versus Adrb2 cKO mice), F(2, 11) = 19.78. In all graphs, each point or dashed line indicates data from an individual animal (c–i), while columns or solid lines with error bars indicate the mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA (c) and two-way ANOVA (e,i) followed by Tukey post-hoc test, Sidak post-hoc test (h); n.s., not significant; *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001. For f, experiments were repeated four times independently with similar results obtained.

The β2-adrenergic receptor (Adrb2) is highly expressed by microglia and is a key mediator of microglial dynamics during anesthesia15, 16. To examine the role of NE signaling in microglial shielding of GABAergic input, we started with the Adrb2 agonist formoterol. Administration of formoterol (50 μg/kg, i.p.) blocked microglial territory changes seen after anesthesia, similar to previous reports15, 16 (Extended Data Fig. 9a-c). In addition, we found that formoterol administration prevented emergence-induced neuronal hyperactivity (Extended Data Fig. 9d-f). Next, we used microglia-specific Adrb2 conditional knockout mice (cKO, Cx3cr1CreER/+;Adrb2fl/fl). The efficiency of the Adrb2 deletion in microglia after tamoxifen treatment was confirmed by qPCR experiments of sorted microglia (Cx3cr1CreER/+ with tamoxifen: 1.00; Cx3cr1CreER/+Adrb2fl/fl mice: 1.23; Cx3cr1CreER/+Adrb2fl/fl mice with tamoxifen: 0.04; Fig. 6d,e). Increased microglial process dynamics were lost during anesthesia in Adrb2 cKO mice (Fig. 6f and Supplementary Video 9). This loss of increased process dynamics was seen during both anesthesia and emergence (Fig. 6g,h). In addition, the directness of the process movement was increased by anesthesia in WT mice, whereas in Adrb2 cKO mice the directness was already high during the awake phase and was not altered by anesthesia (Extended Data Fig. 10a,b). In addition, Adrb2 cKO mice did not show hypersensitivity in the von Frey test during emergence from anesthesia (Fig. 6i).

We further investigated whether microglial β2-adrenergic signaling underlies the regulation of neuronal hyperactivity during anesthesia and emergence. Specifically, we performed imaging experiments in two phases (Fig. 7a). We first imaged microglia-neuron dynamics before tamoxifen-induced Adrb2 deletion in microglia. We then performed a second round of imaging after tamoxifen-induced cKO to establish within-subject controls. Before microglial Adrb2 deletion, we consistently observed neuronal hyperactivity during emergence from anesthesia, similar to levels observed in other strains. We found that after Adrb2 cKO, the previous emergence-induced hyperactivity was abolished (Fig. 7b,c and Supplementary Video 10). At the population level, the percentage of neurons exhibiting hyperactivity during emergence decreased with microglial Adrb2 cKO (before Adrb2 cKO: 45.5%, after Adrb2 cKO: 27.7%; Fig. 7d). At a larger scale, EEG recording across experimental phases indicate that alpha, beta, and theta band power increased during emergence before Adrb2 deletion, but this shift in EEG power was later lost after Adrb2 deletion (Extended Data Fig. 10c,d). Furthermore, the number of bulbous endings around neuronal somata and their colocalization with VGAT puncta were reduced in Adrb2 cKO mice compared to WT mice during anesthesia (Fig. 7e–g, Extended Data Fig. 10e). Together, these results suggest that NE signaling to microglial β2-adrenergic receptors is critical for promoting neuronal hyperactivity and mechanical hypersensitivity during emergence.

Fig. 7: Microglial β2-adrenergic receptors regulate neuronal hyperactivity during emergence.

a,Within-subject study design comparing responses in Cx3cr1CreER/+; Adrb2fl/fl mice before and after tamoxifen-induced recombination. b–c, Neuronal calcium signal amplitude (b) and signal area (c) across experimental time points for mice before and after recombination for Adrb2 cKO (n = 6 mice). p = 0.0006 (Emergence 15 min, WT versus cKO), p < 0.0001 (30 min, WT versus cKO), p = 0.0047 (45 min, WT versus cKO), p = 0.1056 (60 min, WT versus cKO), F(1, 10) = 16.14 (b), p = 0.5940 (Emergence 15 min, WT versus cKO), p = 0.0012 (30 min, WT versus cKO), p = 0.1215 (45 min, WT versus cKO), p = 0.9667 (60 min, WT versus cKO), F(1, 10) = 9.060 (c). d, Percentage of neurons showing an increase, decrease, or no change in activity during emergence period compared to awake baseline. In this case, the same populations of neurons are compared before mice undergo cKO and again after tamoxifen-induced recombination (n = 6 mice). p = 0.0158 (Increased, WT versus cKO), p = 0.8777 (No change, WT versus cKO), p = 0.0335 (Decreased, WT versus cKO), F(1, 10) = 0.6680. e, Immunostaining of microglial processes, NeuN somata, and VGAT puncta in cKO mice (Scale bar: 5 μm). f, Quantification of microglial bulbous tip endings contacting NeuN across experimental phases by genotypes (n = 5 mice). p = 0.9563 (Awake, WT versus cKO), p = 0.0145 (Isoflurane, WT versus cKO), p = 0.0536 (Emergence, WT versus cKO), F(1, 24) = 8.927. g, Area of co-labelling between IBA1 microglia and VGAT puncta across experimental phases and between genotypes. Adrb2 WT: n = 40 (Awake), n = 89 (Isoflurane), n = 126 (Emergence); Adrb2 cKO: n = 43 (Awake), n = 54 (Isoflurane), n = 85 (Emergence) from 5 mice. p < 0.0001 (Awake, WT versus cKO), p < 0.0001 (Isoflurane, WT versus cKO), p = 0.0091 (Emergence, WT versus cKO), F(1, 431) = 4.464. h, Graphic summary. During anesthesia, microglia extend their processes in response to decreased NE concentration in brain parenchyma, and their bulbous endings interact with the neuronal cell body. This bulbous ending contacts inhibitory synapses and induces neuronal hyperactivity during emergence by shielding inhibitory inputs. As a result of these, mice exhibit hypersensitivity and locomotor hyperactivity at emergence. In all graphs, each point or dashed line indicates data from an individual animal (b-f), or a microglial process (g), while columns or solid lines with error bars indicate the mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak post-hoc test; n.s., not significant; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001. For e, the experiment was repeated five times independently with similar results obtained.

Discussion

Microglia are highly dynamic immune cells critical for brain homeostasis. Microglia dampen neuronal hyperactivity during seizures and epilepsy9, 11. However, it is completely unknown whether microglia influence neuronal activity under conditions like general anesthesia. Here we report that during anesthesia, dynamic microglial processes interact with neurons and shield axosomatic inhibitory inputs to transiently promote neuronal hyperactivity during emergence from isoflurane anesthesia (Fig. 7h). Our study thus provides evidence that microglia can boost neuronal activity during emergence from anesthesia. Our study is part of a larger picture in which microglia can both negatively and positively regulate neuronal activity in a way that is homeostatic, boosting neuronal activity following hypoactivity (this study) or dampening neuronal activity following hyperactivity11.

Microglia as a key player in synaptic remodeling.

Typical roles for microglia–synapse interactions include synaptic pruning and promoting spine formation, resulting in relatively persistent changes to neuronal circuits. Synapse pruning by microglia was observed in brain development or disease contexts4, 5, 22. Spine formation by microglia involves either physical contact of microglial processes with dendrites or release of BDNF from microglia23, 24. Microglia also have the potential to modulate neuronal activity via synaptic displacement25. Microglia activated by inflammatory signaling migrate around neuronal cell bodies and perform neuroprotective synaptic displacement26, 27. In addition, during development, microglia displace excitatory GABAergic synapses and suppress hyperexcitability by making dense contacts with neuronal cell bodies in a febrile seizure model17. In the current study, we reveal a different type of microglia-synapse interaction in healthy adult brains that promotes neuronal activity by shielding synaptic inputs without phagocytosis. A transient interaction between microglia and neurons during 30 minutes of anesthesia allows microglia to selectively engage with inhibitory synapses onto excitatory neuron somata. Specifically, super-resolution microscopy revealed that microglial processes shield GABAergic inputs from the soma. These observations are confirmed by 3-dimentional electron microscopy (serial reconstructions) prepared from a region visualized in vivo using two-photon microscopy. This more localized axosomatic interaction site suggests a mode of regulation different from synaptic stripping or microglia-neuron soma-soma interactions17, 27. Together, our current study uncovers a novel interaction between microglial process and inhibitory boutons to transiently boost excitatory activity during emergence from anesthesia.

How microglia promote neuronal activity.

Recently, it has been reported that microglia reduce neuronal activity by degrading ATP and converting it into adenosine11. Microglial processes also form purinergic–somatic connections with neurons in a P2Y12 receptor-dependent manner, which can also dampen neuronal activity9, 12. Such studies propose microglia act as a ‘brake’ on neuronal hyperactivity, playing a homeostatic or neuroprotective role in this context. In contrast, our study finds that microglia are able to enhance neuronal activity during the emergence from general anesthesia. Mechanistically, we find that microglia–neuron interactions during anesthesia promote later neuronal hyperactivity in emergence by transiently shielding inhibitory GABAergic inputs on neuronal cell bodies. Our study strongly supports the hypothesis of transient PV bouton displacement by microglia and consequent blockade of inhibitory inputs, rather than phagocytosis.

Confocal imaging reveals that an average of 30 VGAT-positive inputs synapse onto Layer II/III neuronal somata in a single plane of imaging. Microglial bulbous endings overlapped with 1.4% of these GABAergic inputs during the awake state and 8.7% of boutons during anesthesia. While interactions with GABAergic inputs may seem infrequent, axosomatic GABAergic synapses are known to exert an outsized role in controlling excitatory neuronal activity28, such that relatively infrequent shielding could still have a marked physiological impact. To directly evaluate the impact of inhibiting GABAergic input on excitatory neuronal activity, we employed the Gi-DREADD approach on PV interneurons. This method assesses the functional significance of PV input shielding. Indeed, our findings reveal that activating Gi-DREADD in PV neurons causes excitatory neurons to become hyperactive, similar to what is observed upon emergence from anesthesia. During the emergence, there was no further increase in neuronal activity. In addition, microglia-depleted mice showed neuronal hyperactivity after PV-Gi-DREADD activation but not during emergence from anesthesia. These suggest that microglia are critical for the hyperactivity during emergence from anesthesia, via PV interneurons. A limitation of our approach is that the PV input was inhibited in all Gi-DREADD expressing cells, making it challenging to experimentally mimic individual microglial shielding. Thus, it is possible that mechanisms other than synaptic shielding may contribute to microglia-dependent neuronal hyperactivity during emergence from anesthesia. Going forward, a more detailed validation will be essential to study the function of individual PV synapses and microglial shielding.

Immunostaining results with Kv2.1 show a structural resemblance between microglial shielding of inhibitory synapses and somatic purinergic junctions. This suggests that the clustering of exocytosis-promoting neuronal Kv2.1 may play a role in forming bulbous ending contacts, possibly through the release of ATP. However, the neuronal hyperactivity caused by microglial shielding contrasts with a previously reported somatic purinergic junction as a neuroprotective function12. Thus, although there was possible common mechanism underlying the formation of somatic microglia-neuron junctions, the functions of these microglial contacts may vary depending on the contexts.

The question remains as to how microglia selectively increase their interactions with inhibitory synapses but not excitatory synapses during anesthesia. Microglia may be able to sense GABAergic signaling directly in this period. Microglial GABAB receptors have been reported to mediate inhibitory synapse pruning during development18. Existing RNAseq databases suggest these same receptors are present on microglia in adulthood29. Microglia can also sense astrocyte-mediated synaptic GABA release through their GABAB receptors in development19. Our immunostaining results indicate that GABAB receptors are enriched on bulbous endings after anesthesia compared with those under awake conditions. It is possible that GABAB receptors, which accumulate from the soma to the bulbous ending upon anesthesia, enhance the selectivity of synaptic contacts by microglia. The interaction between GABAergic synapses and microglia as informed by GABA - GABAB receptors on microglia in the adult brain is a key future direction.

NE has been reported as a signal to restrict microglial process motility and extension during wakefulness15, 16. Under anesthesia, NE reduction is thought to allow microglial process elongation through disinhibition, thereby increasing the opportunity for physical contact between microglia and neurons. The administration of Adrb2 agonist compensated for the decrease of NE concentration during anesthesia, thereby reducing the extension of microglial processes and neuronal hyperactivity. In Adrb2 cKO microglia, microglial processes were already elongated in the awake baseline period, due to a lack of NE signal reception. Adrb2 cKO prevented any changes in microglial motility or territory area during anesthesia or in the post-anesthesia recovery period. Interestingly, co-localization of microglial processes with VGAT puncta was higher in Adrb2 cKO mice than WT mice at baseline. However, in the baseline period we did not find that this influenced neuronal calcium activity or EEG power between genotypes. There was also no difference in sensory thresholds between control and cKO mice in the von Frey tests at baseline, suggesting that multiple key aspects of physiology studied herein are not radically altered by baseline differences in the microglial Adrb2 cKO animals. Overall, disturbing NE tone signaling to microglia during anesthesia via administration of Adrb2 agonists or Adrb2 conditional deletion has the potential to reverse neuronal hyperactivity in this context.

The functional significance of microglia in promoting neuronal activity.

During the post-anesthesia recovery period, hypersensitivity and cognitive dysfunction are known to occur transiently in patients and may present as temporary delirium. The primary mechanisms thought to underlie this phenomenon are neurotransmitter imbalance, inflammation, and physiological stress13, 30. Previous in vivo experiments in rodents and clinical observations in patients have suggested that prolonged anesthesia can increase inflammatory cytokine levels in the brain, with associated memory deficits30, 31. Here we discovered an unappreciated function of microglia in promoting neuronal hyperactivity during emergence from general anesthesia. Our microglial ablation approach using a Csf1 receptor inhibitor strengthens the idea that microglia are required for neuronal hyperactivity and mechanical sensitization. Some microglial states, such as disease-associated microglia, downregulate IBA1 and are resistant to Csf1 receptor inhibition32, 33. This is unlikely a concern in our study since we utilize healthy adult mice and 98% of IBA1+ cells were depleted. The somatosensory cortex, the area in which we observed neuronal hyperactivity, is required for von Frey responses34, 35. Consistently, we observed microglia-dependent mechanical sensitization in response to von Frey tests during the emergence from anesthesia.

In the present study, EEG power spectral analysis indicates that mice experience increased theta and delta waves during emergence from anesthesia, which is often correlated with the presentation of delirium in patients36. Interestingly, EEG analysis using microglial Adrb2 cKO mice indicated that alpha, beta, and theta band power did not increase during emergence from anesthesia, indicating a circuit-level effect of microglia on neuronal activity. This observation co-occurs with a lack of hypersensitivity in cKO mice. The loss of microglia-inhibitory synapse interactions in Adrb2 cKO mice during anesthesia prevents PV synapses from being shielded, likely allowing GABAergic interneurons to better control/suppress hyperactivity during emergence. From our results, it would be intriguing to know if the use of β-blockers (either administered in some anesthetic regimens or taken by patients) correlates with less delirium or reduced hypersensitivity upon emergence from anesthesia. Systemic administration of β-blockers can directly inhibit the microglial β2-adrenergic receptor, as we have previously demonstrated in mice15.

During sleep, NE concentration in the parenchyma is reduced37, similar to our observations under anesthesia. Previous studies suggest that microglia prune excitatory synapses during sleep, and chronic sleep deprivation can result in microglial reactivity/activation38, 39. We found that microglia depletion (PLX3397) suppressed neuronal hyperactivity in emergence and reduced hypersensitivity. A Previous study showed that decreased stable wakefulness after microglia ablation and alter sleep patterns by promoting non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep and decreasing nocturnal arousal in microglia ablated mice40. Decreased NE release during sleep might lead to microglial process extension and increased surveillance territories15, 16, 41. Although there are fundamental differences between the mechanisms of anesthesia and sleep42, these NE-dependent microglial functions are potentially important in a number of physiological states such as sleep. It is highly probable that microglia exhibit distinct functions during typical sleep-wake transitions and emergence from anesthesia. Thus, studying the broader applicability of our findings in anesthesia warrant future exploration, particularly in assessing sleep cycles.

In summary, we found that microglia transiently enhance neuronal activity to potentially counteract strong neuronal hypoactivity during isoflurane anesthesia. A novel interaction between microglial processes and GABAergic synapses shields inhibitory inputs, thereby promoting hyperexcitability. Our study demonstrates a previously unappreciated function of microglia in a positive feedback response to neuronal hypoactivity, which manifests at the cell, systems, and behavioral levels during the emergence from isoflurane anesthesia.

Methods

Animals

Male and female mice, 2 to 5 months of age, were used in accordance with institutional guidelines. All experimental procedures were approved by the Mayo Clinic’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC, protocol #5285–20, #7076–23), and were conducted in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Mice were housed with a standard 12-h light (6:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m.)/12-h dark (6:00 p.m. to 6:00 a.m.) at 22°C with 40–60% humidity and fed standard chow ad libitum. Neuron calcium activity was studied in C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) mice (JAX: 000664) using adeno-associated viruses (AAV). Cx3cr1GFP/+ (JAX: 005582) mice were used to visualize microglia and neuron interactions for in vivo two-photon imaging, where neurons were visualized using AAV transfection. Cx3cr1GFP/+ mice were also crossed with PV-Cre knock-in mice (JAX:017320) for microglia and PV neuron interaction studies. Cx3cr1CreER/+ (JAX: 021160) mice were bred to Adrb2fl/fl mice (generously provided by Dr. Gerard Karsenty at Columbia University) and Ai14 (tdTomato reporter) mice (JAX: 007914) to generate mice which had β2-adrenergic receptors selectively knocked out of microglia. To activate CreER recombination, tamoxifen (#T5648, MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA) was injected intraperitoneally 6 weeks before imaging or tissue collection (150 mg/kg, dissolved at 20 mg/mL in corn oil, 5 total injections spaced 48 hours apart). To pharmacologically ablate microglia, mice were fed a chow containing PLX3397, a colony-stimulating factor 1 (Csf1) receptor inhibitor, for 3 weeks (600 mg/kg, #C-1271, Chemgood, Henrico, VA). Animals used for all experiments were randomly selected.

Virus injection and chronic window implantation

Under isoflurane anesthesia (3% induction, 1.5% maintenance,), AAVs were injected into the somatosensory cortex (AP: −4.5, ML: +2.0) using a glass pipette and micropump (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). AAVs were targeted to layer II/III neurons (DV: −0.2). A 250 nL volume was dispensed at a 40 nL/min rate followed by a 10 min waiting period for diffusion. To image neuronal calcium activity, 250 nL of AAV9.CaMKII.GCaMP6s (107790-AAV9, Addgene) was injected into the somatosensory cortex (2 mm posterior and 1.5 mm lateral to bregma). To study the relationship between microglia and neuron interactions and neuron calcium activity, we injected a cocktail of three viruses: AAV1.CaMKII.Cre (105558-AAV1, Addgene), AAV9.Syn.Flex.GCaMP6s (100845-AAV9, Addgene), and AAV9.CAG.FLEX.tdTomato (28306-AAV9, Addgene) into S1 cortex of Cx3cr1GFP/+ mice. To visualize microglia and PV boutons simultaneously, we injected AAV9.CAG.FLEX.tdTomato into S1 cortex of Cx3cr1GFP/+:PVCre/+ mice. To manipulate PV neuron activity, we injected AAV9.CaMKII.GCaMP6s (107790-AAV9, Addgene) and AAV2-hSyn-DIO-hM4D(Gi)-mCherry (44362-AAV2, Addgene) into PVCre/+ mice. To image norepinephrine dynamics, AAV9-hsyn-NE2h (YL003011-AV9, WZbioscience) was injected into the somatosensory cortex for in vivo two-photon imaging21.

Mice were implanted with a cranial window immediately after virus injection as previously described43. A 5 mm circular coverslip was sealed in place with light-curing dental cement (Tetric EvoFlow, Ivoclar, Buffalo, NY). The skull, excluding the region with the window, was then covered with iBond Total Etch primer (Heraeus, Germany) and cured with LED light. Finally, a head bar (Neurotar, Helsinki, Finland) was attached to the skull using light-curing dental glue, and all exposed skull surface was also covered by dental glue. Mice were allowed to recover from anesthesia on a heating pad for 10 min before they were returned to their home cage. Ibuprofen in drinking water was provided as an analgesic for 48 hours post-surgery.

Drug administration

To activate Gi-DREADD, clozapine N-oxide (CNO, #16882, Cayman chemical; 5 mg/kg, i.p.) was administrated to PVCre/+ mice. The effect of Adrb2 agonist (Formoterol, #1448, Tocris) was tested at 50 μg/kg body weight. Formoterol was dissolved in 0.9% sterile saline and injected intraperitoneally 30 min before two-photon imaging.

In vivo two-photon imaging

After recovery from virus injection and cranial window surgery (2–4 weeks), mice were trained to move on an air-lifted platform (NeuroTar, Helsinki, Finland) while head-fixed under a two-photon microscope. Training occurred for 30 min/day for the first 3 days following surgery and once per week thereafter. Across all studies, mice were allowed 10 min to acclimate after being placed in the head restraint before imaging began. Mice were imaged using a two-photon imaging system (Scientifica, UK) equipped with a tunable Ti: Sapphire Mai Tai Deep See laser (Spectra Physics, CA, USA). Laser wavelength was tuned to 920 nm to image GCaMP6s fluorescence and Cx3cr1GFP/+ microglia, or 950 nm to image tdTomato-labelled neurons and GFP microglia simultaneously. Imaging utilized a 40× water-immersion lens and a 180×180 μm field of view (512×512 or 1024×1024 pixel resolution). The microscope was equipped with a 565 nm dichroic mirror and the following emission filters: 525/50 nm (green channel) and 620/60 nm (red channel) for GFP/tdTomato imaging. The laser power was maintained at 30–40 mW. Imaging in cortex was conducted 50–150 μm beneath the pial surface (Layer I) or 150–200 μm depth (Layer II/III).

To image neuronal calcium activity, WT mice were first imaged under awake baseline conditions (15 min; 150–200 μm depth). A nose cone was then secured against the head-restraint system and the mouse was induced with isoflurane on the platform (3%, up to 60 s). Isoflurane was then maintained at 1.5% for the duration of anesthesia imaging, acquired as two 15 min blocks. Under isoflurane, body temperature was maintained at 37°C using a closed-loop heating system (Physitemp, Clifton, NJ). To end anesthesia, the nose cone was removed, and mice were imaged during this recovery period (‘emergence from anesthesia’) over four 15 min blocks (60 min emergence). Mouse locomotion was recorded during in vivo calcium imaging using the Mobile HomeCage magnetic tracking system (Neurotar, Helsinki, Finland). To image microglial dynamics, we acquired Z-stacks (8 sections, 2 μm step size) once every min. To image microglia-neuron interactions, we also acquired Z-stacks (18 sections, 2 μm step size, 512×512-pixel resolution) once every 2–3 min. Imaging data were excluded from analysis only in the instance of technical failure.

Imaging data analysis

Z-stack images and time-series images were corrected for focal plane displacement using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/) with the plug-ins TurboReg and StackReg44. To analyze time-series neuronal Ca2+ activity, an average intensity image of the entire video was generated for region of interest (ROI) selection. ROIs were manually drawn with the oval selection tool for all neuronal cell somas detected in layer II/III. Neurons that did not show a bright ring and dark nuclei during the awake period (baseline) were excluded from the analysis as they did not express GCaMP6 appropriately. Using these ROIs, mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) values were obtained and converted into ΔF/F. The baseline fluorescence was considered as the lower 25th percentile value across all frames. To classify changes in neuronal activity before and after anesthesia, the following criteria were used: increased (the signal area is more than 1.5 times the baseline), decreased (less than half the baseline). Microglial territories were determined from Z-stack maximum projection images and were calculated as the outermost area of microglia when the distal process tips are connected by a polygon. For the contact analysis, if the distance along the microglial bulbous endings–neuronal cell soma was below 4 pixels (1 μm) between the point the green fluorescence (Cx3cr1-GFP signals) and the point the neuronal fluorescence (tdTomato or GCaMP6 signals) in the same focal plane, the bulbous ending was defined to have contacted the cell soma. Based on this definition, counting was done manually. In classifying neurons by microglial contacts, those with two or more contacts at the end of anesthesia were classified as high contact and those with no or one contact were classified as low contact. A microglial bulbous ending was defined as having a head diameter at the process tip that is at least twice the diameter of the process neck. To determine microglial process motility, maximum Z-projection images were used to track primary process tips using the manual tracking plugin in ImageJ. Directness of microglial processes was calculated as Euclidean distance of process tips divided by accumulated distance.

To examine norepinephrine dynamics, MFI of time-series images were measured for the entire field of view and were converted into ΔF/F. The baseline fluorescence was considered as the lower 25th percentile value across all frames.

Behavioral tests

To assess mechanical hypersensitivity, von Frey filaments (0.07–2.0 g, North Coast Medical, USA) were applied to the plantar surfaces of the hindpaws before and after isoflurane induction and the 50% withdrawal threshold value was determined using the up–down method45, 46.

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane then transcardially perfused first with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) within 1 min, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Brains were post-fixed overnight in 4% PFA and immersed in 30% sucrose for 2 days for cryoprotection. The brains were sectioned into 30 μm slices. After PBS wash, slices were incubated for 1 hour in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.5% Triton X-100 dissolved in PBS (PBST), before being incubated at 4 °C overnight with primary antibodies (anti-IBA1, 1:500, #ab5076 Abcam; anti-NeuN, 1:500, #ab104225 Abcam; anti-VGAT, 1:500, #131 004 Synaptic Systems; anti-VGLUT1, 1:500, #135 304 Synaptic Systems; anti-Gephyrin, 1:1000, #147 011 Synaptic Systems; anti-Kv2.1, 1:400, #75–014, NeuroMab; anti-GABAB1R, 1:400, #73–183, NeuroMab) diluted in PBST. The slices were subsequently incubated with secondary antibodies (anti-goat Alexa 488, anti-rabbit Alexa 647, anti-rabbit Alexa 405, anti-mouse Alexa 647, 1:500, Thermo Fisher Scientific; anti-guinea pig Cy3, 1:500, Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs) at room temperature (RT) for 3 hours. Slices were then mounted on glass slides with DAPI Fluoromount-G (0100–20; Southern Biotech). Fixed tissue was imaged using 63× oil-immersion objective lens with a Zeiss LSM980 Airyscan 2 for confocal imaging or Zeiss ELYRA PS.1 for super-resolution imaging (Zen version 3.6, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Quantitative analysis of immunohistochemistry data

In examining the number of bulbous endings on microglia contacting neuronal somata, single plane confocal images were used to count contacts with NeuN-positive neuronal somata. The interaction between bulbous endings and VGAT puncta were characterized from confocal 3D image data (2048×2048 pixels, 0.082 μm/pixel, 0.5 μm Z-step, 20 slices). Volume rendering and visualization were performed using Imaris 9.2 (Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK). After applying a threshold (MaxEntropy method) for each channel, bulbous ending structures were classified into four types on interaction: (1) No contact, no merger of IBA1 and VGAT puncta, (2) Contact, under 50% merger of IBA1 and VGAT puncta area, (3) Enwrapped, more than 50% merger of IBA1 and VGAT puncta area, and (4) Engulfment, complete internalization of the VGAT puncta area by IBA1. Co-localization of microglial bulbous endings and synaptic marker fluorescent signals was used to determine interactions, defined by IBA1 positive area overlapping with VGAT or VGLUT1 positive area. For this analysis, 50×50 pixels around the bulbous ending were cropped from each confocal image, and thresholds were applied using the MaxEntropy or Otsu method for each channel. The co-localized area was calculated in each frame. Microglia density was quantified for each instance in which an IBA1 cell had a DAPI positive nucleus identifiable in the Z-stack. Imaris software was also utilized to render and obtain 3D reconstructed images using the “Spot tool” for synapse quantification and using the “Surface tool” for representative images. Gephyrin+ and VGAT+ puncta were rendered using the “Spot tool”. The VGAT+ puncta were distributed outside neurons and were filtered for spots less than 2.5 μm from the neuronal surface. Distributed Gephyrin+ puncta inside neurons colocalized with VGAT+ puncta (spot distance less than 2.0 μm) were defined as inhibitory synapses. For microglial process shielding inhibitory synapse, colocalized VGAT+ Gephyrin+ puncta were filtered for spots less than 1.0 μm from the microglia surface, which was defined as microglial processes entering into the synaptic cleft. To quantify the percentage of functional synapses and shielding synapses on a neuron, the number of VGAT+ Gephyrin+ spots and VGAT+ Gephyrin+ spots close to the microglial processes was divided by the total number of VGAT+ spots within each colored neuron, respectively. For purinergic junction analysis, Kv2.1 and VGAT clusters were reconstructed using the “Spot tool” as described above. Kv2.1+ spots and Kv2.1+ VGAT+ spots were quantified within the neuron-contacted or non-contacted microglial processes in the cropped 3D volume (X: 11 μm, Y: 11μm, Z: 7.5 μm). For the typical images, neurons, microglia, and all synaptic proteins were rendered using the “Surface tool” within the cropped volume (X: 35 μm, Y: 35 μm, Z: 7.5 μm), which contains a whole neuron. All the capture crop 3D volumes were selected randomly.

Near-infrared branding (NIRB)

We used the NIRB technique to create laser-defined fiducial marks for later electron microscopy identification of cells observed under two-photon microscopy. After two-photon imaging, mice were perfused with 4% PFA in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.2). The brain tissue was cut into 1mm thick horizontal sections and post-fixed for 2 h. After fixation, sections were mounted in PBS on a glass slide.

We made NIRB marks on fixed tissue using the two-photon microscope laser. Initially, XYZ images were taken to re-identify the same locations as in vivo imaging20. After identification, the laser was tuned to 800 nm wavelength (laser power: ~400 mW in the focal plane) and was focused at 99× through the objective. We made linear NIRB markings along a square path of 150 μm per side surrounding the target microglial cell. The time of laser irradiation was adjusted to ensure that the laser burn did not extend into the target microglia. After NIRB marks were made, sections were post-fixed by immersion in 2% glutaraldehyde + 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer containing 2 mM calcium chloride at 4 °C for at least 24 hours.

Serial block-face scanning electron microscopy

Samples for serial block-face scanning electron microscopy (SBF-SEM) were prepared as reported47. Briefly, NIRB marked samples were rinsed in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer and placed in 2% osmium tetroxide + 1.5% potassium ferracyanide in 0.1 M cacodylate, then washed with double distilled water (ddH2O) incubated at 50°C in 1% thiocarbohydrazide, incubated again in 2% osmium tetroxide in ddH2O, rinsed in ddH2O and then placed in 2% uranyl acetate overnight. The next day sample were rinsed in ddH2O, incubated with Walton’s lead aspartate, dehydrated through an ethanol series, and embedded in Embed 812 resin (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA). Based on ferrocyanide-reduced osmium-thiocarbohydrazide-ferrocyanide-reduced osmium (rOTO) stains48, this procedure introduces a considerable amount of electron-dense, heavy metals into the sample to provide the contrast necessary for SBF-SEM.

To prepare the embedded sample for placement into the SBF-SEM, a ~1.0 mm3 piece was trimmed of any excess resin and mounted on an 8 mm aluminum stub using silver epoxy Epo-Tek (EMS, Hatfield, PA). The mounted sample was then carefully trimmed into a smaller ~0.5 mm2 column using a Diatome diamond trimming tool (EMS, Hatfield, PA) and vacuum sputter coated with gold palladium to help dissipate electrostatic charge. Sectioning and imaging of the sample was performed using a VolumeScope 2 SEM™ (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Imaging was performed under high vacuum/low water conditions with a starting energy of 1.8 keV and beam current of 0.10 nA. Sections of 50 nm thickness were cut allowing for imaging at 8 nm x 8 nm x 50 nm spatial resolution.

3D image segmentation

Image analysis, including registration, volume rendering, and visualization were performed using ImageJ, Amira (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and Reconstruct 49 software packages. Cell morphology and ultrastructure were identified and segmented in every 50 nm thick section using two-photon images as a reference. In segmenting microglial morphology, cell somas were first identified using established criteria, which include relatively dark nuclei with clumped chromatin, narrower space between nuclear membranes, a dark cytoplasm and processes containing elongated endoplasmic reticulum50. The processes of these microglia were then tracked in across 3D images to identify bulbous endings associated with specific elements of the neuron.

Synapses were characterized by a presynaptic element or varicosity that contains synaptic vesicles and forms one or more electron-dense junctions with an axon terminal or cell body of the postsynaptic neuron51. Synapses in displacement were defined as one in which the bouton is adjacent to the neuronal cell body with microglial processes between them25, 26. If a structure other than microglia was present in the gap, it was excluded because it was determined that they had not originally formed synapses there. The PV-bouton structure was estimated based on fluorescence images of tdTomato, which virally labeled PV-boutons in two-photon microscopy. This ultrastructure was determined by segmentation of the actual electron microscope images.

RNA Extraction and qPCR

After transcardiac perfusion with 50 mL cold PBS, brains were harvested. Samples then underwent cell disassociation using the Adult Brain Dissociation kit (130–107-677; Miltenyi Biotec) per manufacturer’s instructions. Microglia were enriched from the single-cell suspension via CD11b magnetic bead sorting (18970; STEMCELL Technologies). CD11b negative flow-through samples were collected as to access the gene expression in CNS non-microglia cells. For microglia, total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Micro kit (74004; Qiagen). For CNS non-microglia cells, total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Plus Mini kit (74134; Qiagen). The cDNA library was prepared by the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (1708890; Bio-Rad). SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix Kit (1725272; Bio-Rad) was used for real-time qPCR. The analysis for Adrb2 expression in microglia and CNS non-microglia cells was performed with the following primers: Gapdh forward: CATCTTCCAGGAGCGAGACC, Gapdh reverse: TCTCGTGGTTCACACCCATC, Adrb2 forward: GGGAACGACAGCGACTTCTT, and Adrb2 reverse: GCCAGGACGATAACCGACAT. The threshold cycle (Ct) value was examined using the LightCycler 480 II (Roche). For data normalization, the Ct value of Gapdh was determined as the reference for each sample, and the relative quantification method (2-ΔΔCt) was used.

EEG recording and analysis

Under Isoflurane anesthesia (3% induction, 1.5% maintenance), a cortical electrode (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) was inserted into layer II/III of the parietal cortex (200 μm depth). Electrodes were secured by super glue (Loctite 454, Westlake, OH) against three anchor screws. Animals were used for EEG recordings after 1–2 weeks of recovery. During recordings, electrodes were connected via flexible tether to a rotating commutator (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) then connected to an EEG100C amplifier (BioPac Systems, Goleta, CA), which filtered signals below 1 Hz and above 100 Hz.

To be consistent with two-photon imaging strategy, mice were recorded 30 minutes of baseline EEG under head-restraint system, then mouse was induced with isoflurane on the platform (3% induction, 1.5% maintenance). Post-processing of the intracranial EEG (iEEG) data was performed using custom algorithms (Matlab version 2019b, MathWorks, Natick, MA) for characterizing the changes of iEEG power in spectral bands of interest (Delta (1–3 Hz), Theta (3–9 Hz), Alpha (8–12 Hz), Beta (15–30 Hz)) as described previously52. Absolute and relative power spectral densities (PSD) across frequency bands were calculated using 10 second windows (epochs) and the average of PSD from all epochs was calculated as a representative value of PSD in each phase of experiment for each subject. Absolute PSD refers to the absolute power (Vrms2/Hz), where Vrms is the root-mean-square voltage of the subject’s iEEG, while relative PSD refers to the percentage of power a frequency band (such as beta) compared to the sum of all frequency bands.

Data analysis and statistics

All measurements were taken from distinct samples. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample sizes, but our sample sizes are similar to those reported in previous publications9,15,43. The data distribution was assumed to be normally distributed, but was not formally tested. Imaging experiments, drug administration, and analyses were mostly performed by the same individual. Wherever possible, a second researcher blinded to the analysis confirmed the result. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8.1.1 software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). All data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined using either unpaired or paired t-tests with a two-tailed test, one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey or Sidak post-hoc test as indicated in either the results or figure legends.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1: Increased neuronal calcium activity and microglial territory changes during emergence from anesthesia in both male and female mice.

a–c, Neuronal Ca2+ signal amplitude (a), time active (b) and signal area (c) across experimental time points for male mice and female mice (amplitude: Awake versus Isoflurane, p = 0.7343; Awake versus Emergence 15 min, p = 0.1393; Awake versus Emergence 30 min, p > 0.9999; Awake versus Emergence 45 min, p > 0.9999; Awake versus Emergence 60 min, p = 0.9486. time active: Awake versus Isoflurane, p = 0.9915; Awake versus Emergence 15 min, p = 0.9187; Awake versus Emergence 30 min, p = 0.9988; Awake versus Emergence 45 min, p = 0.9432; Awake versus Emergence 60 min, p = 0.4240. signal area: Awake versus Isoflurane, p > 0.9999; Awake versus Emergence 15 min, p > 0.9999; Awake versus Emergence 30 min, p = 0.9563; Awake versus Emergence 45 min, p = 0.4973; Awake versus Emergence 60 min, p = 0.1640). Solid lines represent the mean ± SEM from n = 5 mice, while dashed lines indicate individual animals. d, Representative images of microglial morphology in female mouse during each experimental phase (Scale bar: 10 μm). e, Time-course changes in microglial territory (territory: Awake versus Isoflurane 15 min, p > 0.9999; Awake versus Isoflurane 30 min, p = 0.4066; Awake versus Emergence 15 min, p = 0.9920; Awake versus Emergence 30 min, p = 0.5578; Awake versus Emergence 45 min, p > 0.9999; Awake versus Emergence 60 min, p > 0.9999). Solid lines represent the mean ± SEM from male: n = 6 mice, female: n = 5 mice). Two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak post-hoc test; n.s., not significant. All experiments were repeated multiple times using different mice independently with similar results obtained.

Extended Data Fig. 2: Control chow and PLX chow feeding in neuronal activity during emergence from anesthesia.

a, Experimental timeline of control chow feeding and two-photon imaging of neuronal Ca2+ activity. Related to main Fig. 2. b–d, Neuronal Ca2+ signal amplitude (b), time active (c) and signal area (d) across experimental time points for control chow 3-weeks group and 6-weeks group(amplitude: Awake versus Isoflurane, p = 0.9676; Awake versus Emergence 15 min, p = 0.8172; Awake versus Emergence 30min, p = 0.9713; Awake versus Emergence 45 min, p = 0.9911; Awake versus Emergence 60min, p = 0.9530. time active: Awake versus Isoflurane, p > 0.9999; Awake versus Emergence 15min, p = 0.9733; Awake versus Emergence 30 min, p = 0.9897; Awake versus Emergence 45min, p = 0.9697; Awake versus Emergence 60min, p = 0.9995. signal area: Awake versus Isoflurane, p > 0.9999; Awake versus Emergence 15min, p > 0.9999; Awake versus Emergence 30min, p = 0.9754; Awake versus Emergence 45min, p = 0.9992; Awake versus Emergence 60min, p > 0.9999). Solid lines represent the mean ± SEM from n = 4 mice. e–g, Neuronal Ca2+ signal amplitude (e), time active (f) and signal area (g) across experimental time points for before and after microglia ablation at each time point (amplitude: Awake versus Isoflurane, p = 0.9959; Awake versus Emergence 15min, p < 0.0001; Awake versus Emergence 30min, p < 0.0001; Awake versus Emergence 45min, p < 0.0001; Awake versus Emergence 60min, p = 0.0413. time active: Awake versus Isoflurane, p > 0.9999; Awake versus Emergence 15min, p = 0.0069; Awake versus Emergence 30min, p = 0.0009; Awake versus Emergence 45min, p = 0.0601; Awake versus Emergence 60min, p = 0.8613. signal area: Awake versus Isoflurane, p > 0.9999; Awake versus Emergence 15min, p = 0.1259; Awake versus Emergence 30min, p = 0.0013; Awake versus Emergence 45min, p = 0.0239; Awake versus Emergence 60min, p = 0.0657). Solid lines represent the mean ± SEM from n = 10 mice. h–j, Absolute value of neuronal Ca2+ signal amplitude (h), time active (i) and signal area (j) (amplitude: Awake versus Isoflurane, p = 0.9998; Awake versus Emergence 15min, p = 0.7250; Awake versus Emergence 30min, p = 0.7176; Awake versus Emergence 45min, p = 0.9757; Awake versus Emergence 60min, p > 0.9999. time active: Awake versus Isoflurane, p > 0.9999; Awake versus Emergence 15min, p = 0.4355; Awake versus Emergence 30min, p = 0.5141; Awake versus Emergence 45min, p > 0.9999; Awake versus Emergence 60min, p = 0.8270. signal area: Awake versus Isoflurane, p > 0.9999; Awake versus Emergence 15min, p = 0.9626; Awake versus Emergence 30min, p = 0.8873; Awake versus Emergence 45min, p > 0.9999; Awake versus Emergence 60min, p = 0.9442). Solid lines represent the mean ± SEM from n = 10 mice. Two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak post-hoc test (b–j); n.s., not significant; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001.

Extended Data Fig. 3: Increased contacts between microglia and neuronal somata or dendrites in response to general anesthesia.